The Levant Voyage of the Blackham

Galley (1696–1698): The Sea Journal of John Looker, Ship's Surgeon Colin Heywood

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/the-levant-voyage-of-the-blackham-galley-1696-1698 -the-sea-journal-of-john-looker-ships-surgeon-colin-heywood/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

The Ship Beneath the Ice: The Discovery of Shackleton's Endurance Mensun Bound

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-ship-beneath-the-ice-thediscovery-of-shackletons-endurance-mensun-bound/

The Surgeon Karl Hill

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-surgeon-karl-hill/

The Surgeon Karl Hill

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-surgeon-karl-hill-2/

Trapped: Brides of the Kindred Book 29 Faith Anderson

https://ebookmass.com/product/trapped-brides-of-the-kindredbook-29-faith-anderson/

Shipwrecks and the Bounty of the Sea David Cressy

https://ebookmass.com/product/shipwrecks-and-the-bounty-of-thesea-david-cressy/

Call of the Sea Emily B. Rose

https://ebookmass.com/product/call-of-the-sea-emily-b-rose/

Down to a Sunlit Sea (The Winds of Fortune Book 5) John Wiltshire

https://ebookmass.com/product/down-to-a-sunlit-sea-the-winds-offortune-book-5-john-wiltshire/

The Next Ship Home: A Novel of Ellis Island Heather

Webb

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-next-ship-home-a-novel-ofellis-island-heather-webb/

The Next Ship Home Heather Webb

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-next-ship-home-heather-webb-2/

WORKS ISSUED BY THE HAKLUYT SOCIETY

Series Editors

Janet Hartley

Joyce Lorimer

Maurice Raraty

THE LEVANT VOYAGE OF THE BLACKHAM GALLEY (1696–1698): THE SEA JOURNAL OF JOHN LOOKER, SHIP’S SURGEON

THIRD SERIES NO.

40

THE HAKLUYT SOCIETY

Trustees of the Hakluyt Society 2022–2023

PRESIDENT

Dr Gloria Clifton

VICE-PRESIDENTS

Professor Felipe Fernández-ArmestoProfessor Nandini Das

Captain Michael K. Barritt RN

Professor Jim Bennett

Mr Bruce Hunter

Professor Will F. Ryan FBA

Dr Sarah Tyacke CB

COUNCIL

(with date of election)

Dr Katie Bank (2021)

Peter Barber OBE (2019)

Dr Jack Benson (co-opted)

Professor Daniel Carey MRIA (2020)

Dr Matthew Day (2022)

Dr Natalya Din-Kariuki (2022)

Dr Derek L. Elliott (2021)

Dr Sarah Evans (Royal Geographical

Society Representative)

Dr Eva Johanna Holmberg (2019)

Professor Claire Jowitt (2019)

Lionel Knight MBE (2019)

Dr Bertie Mandelblatt (2021)

Dr Richard Marsh (2022)

Dr Guido van Meersbergen (2020)

Dr Elaine Murphy (2022)

Dr Anthony Payne (2019)

Dr Catherine Scheybeler (2019)

Dr Emily Stevenson (2022)

HONORARY TREASURER

Alastair Bridges

HONORARY JOINT SERIES EDITORS

Professor Janet Hartley

Professor Joyce Lorimer

Dr Maurice Raraty

HONORARY EDITOR (ONLINE PUBLICATIONS)

Raymond Howgego FRGS

HONORARY ADMINISTRATIVE EDITOR

Dr Katherine Parker

HONORARY ADVISER (CONTRACTS)

Stephen Edwards

HONORARY ARCHIVIST

Dr Margaret Makepeace

ADMINISTRATION

(to which enquiries and applications for membership may be made) Telephone: +44 (0)7568 468066 Email: office@hakluyt.com

Postal address only

The Hakluyt Society, c/o Map Library, The British Library, 96 Euston Road, London NW1 2DB

Website: www.hakluyt.com

INTERNATIONAL REPRESENTATIVES OF THE HAKLUYT SOCIETY

Africa (North) Dr Derek L. Elliott, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane, P.O. Box 104, Ave Hassan II, 53000 Ifrane, Morocco

Australia John A. Greig, 18 Kiandra Close, The Gap, Brisbane, QLD 4061

Canada Professor Cheryl A. Fury, Department of History and Politics, University of New Brunswick, Saint John, NB, E2L 4L5

Central America Dr Stewart D. Redwood, P.O. Box 0832-0757, World Trade Center, Panama, Republic of Panama

China Professor May Bo Ching, Department of Chinese and History, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong

France Professor Pierre Lurbe, Faculté des Lettres, Sorbonne Université, 1 rue Victor Cousin, 75005 Paris

Germany Monika Knaden, Lichtenradenstrasse 40, 12049 Berlin

Iceland Anna Agnarsdóttir, Professor Emerita, Department of History, University of Iceland, 101 Reykjavík

India Professor Emerita Supriya Chaudhuri, Department of English, Jadavpur University, Kolkata

Ireland Professor Jim McAdam OBE, Queen’s University of Belfast and Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, c/o 16B Dirnan Road, Cookstown, Co Tyrone BT80 9XL

Japan Derek Massarella, Professor Emeritus, Chuo University, Higashinakano 742–1, Hachioji-shi, Tokyo 192–0393

Netherlands Dr Anita van Dissel, Room number 2.66a, Johan Huizingagebouw, Doezensteeg 16, 2311 VL Leiden

New Zealand Dr John Holmes, PO Box 6307, Dunedin North, Dunedin 9059

Portugal Dr Manuel Ramos, Av. Elias Garcia 187, 3Dt, 1050 Lisbon

Russia Professor Alexei V. Postnikov, Institute of the History of Science and Technology, Russian Academy of Sciences, 1/5 Staropanskii per., Moscow 103012

South America Sr Sergio Zagier, Cuenca 4435, 1419 Buenos Aires, Argentina

Spain Ambassador Dámaso de Lario, Calle Los Borja, 3, 3ª, 46003 València

Switzerland Dr Tanja Bührer, Universität Bern, Historisches Institut, Unitobler, Länggasstrasse 49, 3000 Bern 9

United States Professor Mary C. Fuller, Literature Section, 14N-405, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, 02139-4207

THE LEVANT VOYAGE OF THE BLACKHAM GALLEY

(1696–1698):

THE SEA JOURNAL OF JOHN LOOKER, SHIP’S SURGEON

Edited by COLIN HEYWOOD and EDMOND SMITH

Published by

First published 2022 for the Hakluyt Society by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10158

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2022 The Hakluyt Society

The right of Colin Heywood and Edmond Smith to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781032222110 (hbk)

ISBN 9781003271598 (ebk)

Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Waveney Typesetters, Wymondham, Norfolk

Routledge website: http://www.routledge.com

Hakuyt Society website: http://www.hakluyt.com

For April

For being there throughout

1. Lord Paget, the Ottomans, and the Detention of the Blackham Galley

Identified Members of the Company of the Blackham Galley under Captain Charles Newnam

3. Wills of Members of the Crew of the Blackham Galley

4. The Homeward Lading of the Blackham Galley, 13 May–29 December 1697, as Recorded in John Looker’s ‘Journall’

5. Documents on the Appraisal and Sale of the Blackham Galley, London, February 1699 216

6. The Will, Drawn up on 8 February 1714/15 (OS), of John Looker, Surgeon, Who Died at Bath 23 May 1715 223

LIST OF MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

The Hakluyt Society is pleased to acknowledge financial assistance toward the preparation of maps for this volume, given by Rear Admiral J. A. L. Myers, CB, and other anonymous donors, in memory of Lieutenant Commander Andrew C. F. David, a volume editor and former Vice-President of the Society, who died in 2021.

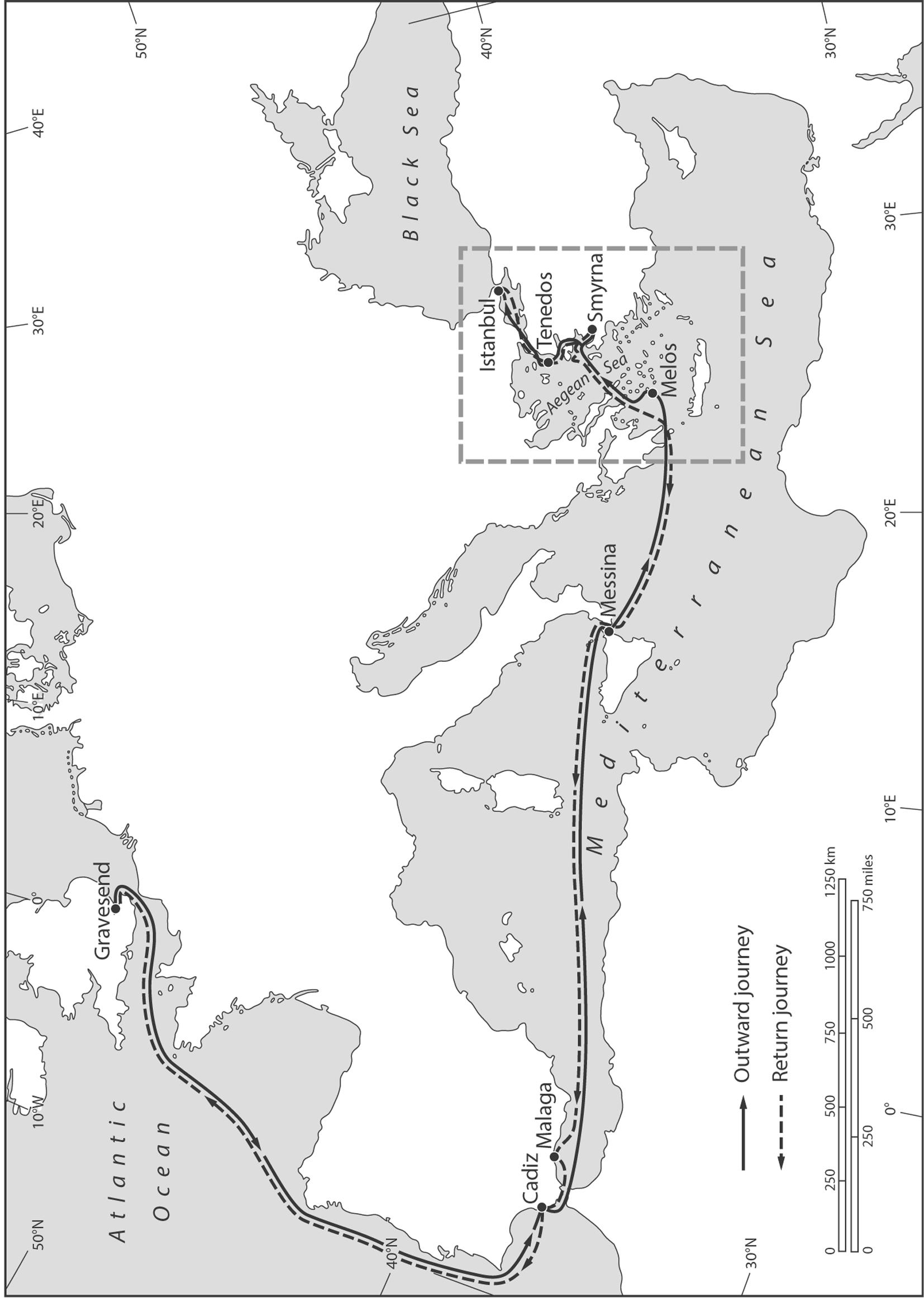

Maps

Map 1. Looker’s voyage on the Blackham Galley

2

Map 2. Smyrna and its environs c.1697 in relation to Looker’s ‘Journall’.74

Map 3. The movements of the Blackham Galley in the Aegean.

Colour Plates

Colour plates 1–8 are located between pages 8 and 9.

75

Plate 1. The first page of Looker’s ‘Journall’. Courtesy of the NMM, Greenwich, London.

Plate 2. Seventeenth-century surgeon’s tools. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Plate 3.An example of Looker’s corrections made when revising his entries. Courtesy of the Royal Museums, Greenwich, London.

Plate 4. Looker’s early detailed tabular record of the ‘way made’ by the Blackham Galley. Courtesy of the Royal Museums, Greenwich, London.

Plate 5. Looker’s signature, London. Courtesy of the Royal Museums, Greenwich, London.

Plate 6.A pencilled note made by Sir Thomas Phillips. Courtesy of the Royal Museums, Greenwich, London.

Plate 7. The final page of Looker’s ‘Journall’. Courtesy of the Royal Museums, Greenwich, London.

Plate 8.The first page of John Looker’s will. Courtesy of TNA, Kew.

Colour plates 9–12 are located between pages 56 and 57.

Plate 9.Sir Richard Blackham’s portrait ring, unknown craftsmen, London. Courtesy of Natasha Donohue and the descendants of Richard Blackham in Australia.

Plate 10.The Cadiz Merchant Underway. Courtesy of the Royal Museums, Greenwich, London.

Plate 11.The appraisal of the Blackham Galley in February 1699. Courtesy of TNA, Kew.

Plate 12. Veue des Dardanelles de Constantinople, anonymous artist, 1726. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Colour plates 13–16 are located between pages 80 and 81.

Plate 13 The View of Smyrna and the Reception given to Consul de Hochepied in the Council Chamber, anonymous artist, c.1687–1723. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Plate 14Detail from Plate 13 showing Dutch, French and English houses built along the shoreline. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Plate 15. Detail from Plate 13 showing a meeting between the Dutch Consul de Hochepied and local Ottoman officials. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Plate 16.The first page of Captain Newnam’s letter to Lord Paget in Constantinople, recounting the seizure of the French settea. Courtesy of the Marquess of Anglesey and the Library of the School of Oriental and African Studies, London.

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

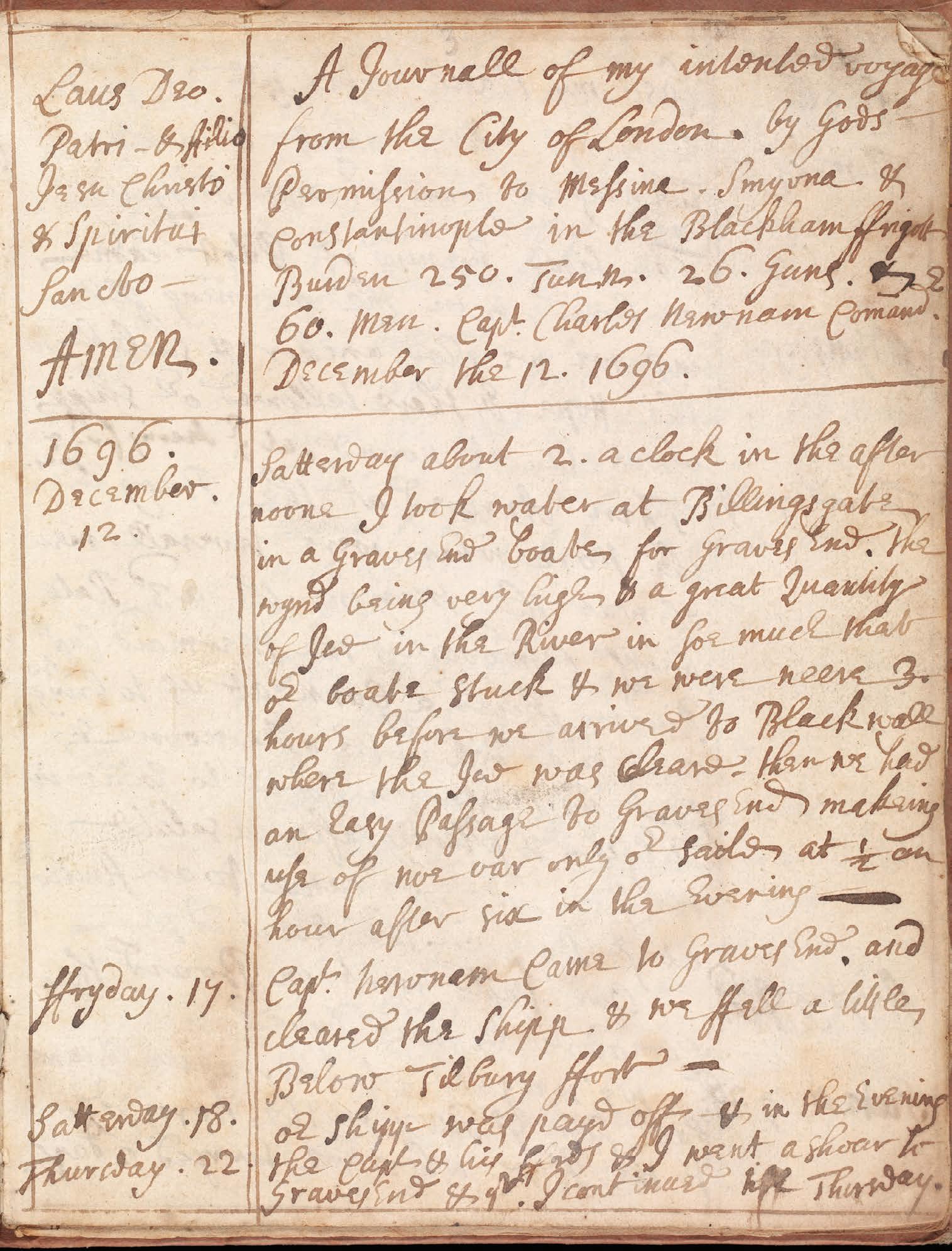

The present work publishes for the first time an English sea journal from the late seventeenth century. The journal was written by John Looker (c.1675–1715), ship’s surgeon, and bears the title ‘A Journall of my intended voyage from the City of London by Gods Permission to Messina Smyrna & Constantinople in the Blackham frigat. Burden 250 Tunns. 26. Guns. & 60 Men. Capt. Charles Newnam Commander. December the 12. 1696.’ As the comprehensive title indicates, Looker’s ‘Journall’ records a Levant voyage of the Blackham Galley, a London merchantman. It begins with Looker’s departure from London in December 1696 to join his ship at Gravesend, and ends in March 1698 on the homeward voyage when, with the ship off the north coast of Kent, the journal abruptly breaks off in mid-sentence.

My work in editing Looker’s ‘Journall’ has a long history. It finds its origin in events more than two decades ago, in 1999, when I was faced with the need to produce at short notice a paper for a maritime conference in Crete devoted to the office and jurisdiction of the Ottoman Kapudan Pasha. I turned to my colleague Dr Pat Crimmin, of Royal Holloway, at the time Caird Fellow at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, who suggested that I should look at ‘an unpublished journal’ in the Caird Library manuscript collection. This turned out to be the journal recording the voyage of the Blackham Galley to the Levant in 1696–8, which at the time was still regarded by the National Maritime Museum as anonymous. It was only later that I discovered its author’s name to be John Looker.

As can be seen below, I had dealt in passing with the diplomatic incident at the Porte which was central to the Blackham Galley’s extended stay in Izmir almost forty years previously. But since the ‘Blackham incident’ closely involved not only the ship’s captain and the English ambassador at the Porte, but also the Ottoman Kapudan Pasha at the time, the redoubtable Mezzomorto Hüseyn Pasha, the problem of finding a suitable topic for the Crete symposium was happily solved. A paper based on my first reading of the ‘Journall’ was duly produced and eventually achieved publication.

It was obvious, however, that the Blackham ‘Journall’ deserved more than summary treatment in a conference paper, and I owe a great debt of gratitude to the late Pat Crimmin for her generosity in handing over to me, as it were, her interest in the manuscript, and for warmly encouraging me to undertake its publication. I subsequently discovered that extensive use of Looker’s ‘Journall’– which was still unattributed – was being made by Mr Jerry Drew, an American PhD student at the University of Pennsylvania, for his research on late seventeenth-century merchant-privateers completed in 2002. An extended study of mainly the legal aspects of the Blackham Galley’s 1696–8 voyage, based largely on Looker’s ‘Journall’, forms chapter three of Dr Drew’s dissertation. I wish to say that I am greatly indebted to his work and insights, particularly those on Sir Richard Blackham, the ship’s eponymous main owner, and his financial connections. The xiii

present volume, however, takes a different approach, which is to place the ‘Journall’ and its subject-matter firmly within the context of the English maritime presence in the Mediterranean a century after the inception of what Fernand Braudel once memorably termed the ‘Northern Invasion’. It seeks, therefore, to provide a critical first edition of the ‘Journall’, John Looker’s sole known work and, indeed, the sole known document from his hand. The edition is based on the unique manuscript in the possession of the Caird Library, NMM PHB/6, which now, more than three centuries after it was written, has finally achieved publication.

In the course of the preparation of this volume, which has extended over many years, I have incurred many debts of gratitude beyond those to Dr Crimmin and Dr Drew which I have already mentioned. My old friend and colleague, the late Miss Sonia Anderson, was unstinting in practical help, support and encouragement from the earliest to the latter stages of the project. My best thanks are equally due to the National Maritime Museum, the custodians of John Looker’s ‘Journall’, and particularly to Dr Nigel Rigby, former Director of Research at the Museum, and to the staff of the Museum’s Caird Library, for facilitating my access to the manuscript and furnishing me with a microfilm of its contents, which became the basis for much of my protracted subsequent work. In 2003 a Caird Part-time Fellowship allowed me to spend several months at Greenwich, working directly on the manuscript.

My understanding of John Looker’s Mediterranean world has been deepened by the opportunity to present seminar and conference papers on various aspects of the Blackham Galley’s voyage and sojourn in the Levant. I am grateful to my former colleagues in the Department of History, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, and particularly to Professor Gerald Hawting and Dr Benjamin Fortna, for the opportunity in 2001 to present in the department’s Middle Eastern History seminar some preliminary findings based on my first reading of the manuscript. I am also grateful to my friends in the Turcology section of the Department of Arabic, Persian and Turkish Studies at Leiden University, and in particular to Dr Maurits van den Boogert and Dr Merlijn Olnon, for an invitation in 2005 to present a paper which allowed me to speak more at length on some of the medical and meteorological material in Looker’s ‘Journall’.

For fruitful discussions on Looker and the Blackham Galley in various places and at various times I am equally indebted to my dear friends Dr Caroline Finkel (Istanbul/London), Professor Cornell Fleischer (Chicago), Professor Victor Ostapchuk (Toronto), and Dr Maria Fusaro (Chicago and Exeter). My good friend Professor David J. Starkey, former Director of the Maritime History Studies Centre (now the Blaydes Centre for Maritime Studies), University of Hull, offered continuing encouragement and support of my project since my move to Hull in 2002. I would also like to thank my mature students in the Hull Diploma programme on Maritime History, given in 2005–6 and 2007–8, retired seamen all. Their eminently practical and unsentimental approach to John Looker and his ‘Journall’ has materially deepened my insights into the maritime milieu of a seagoing surgeon.

My particular thanks are due to the Hakluyt Society for encouraging me to undertake a full edition of Looker’s ‘Journall’ and for generously accepting the present work for inclusion in their Third Series. I must first mention my former series editors, Dr Michael Brennan, who kindly made me welcome on several occasions in Leeds, and Professor Will

Ryan, who provided continued encouragement and support during a long unproductive period marked by adventitious obstacles and hindrances.

I am especially grateful for the unfailing support – material, practical and intellectual – which I have received from Professor Jim Bennett, recently President of the Hakluyt Society. In particular, I wish to acknowledge his inspired appointment, in 2019, of my present co-editor and collaborator, Dr Edmond Smith of Manchester University. My editorial work during the last few years has been greatly aided (and largely made possible) by Dr Smith's cooperation and assistance with the text, the preparation of the first drafts of the maps, and the acquisition of accompanying images. My present series editor, Professor Joyce Lorimer, has been both insightful and supportive throughout the recent years of the editorial process. I am also indebted to her for undertaking the creation of the index. Both she and I wish to acknowledge the generous help afforded by my fellow Ottomanist, Professor Victor Ostapchuk of the University of Toronto, who was an unfailing resource in resolving on the difficulties arising in the rendering of Turkish words into Unicode. I take great pleasure in recognizing my scholarly debts here.

My ultimate debt of gratitude and affection to my wife, which is immeasurable, can only be hinted at in the Dedication.

Colin Heywood

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

BL British Library

NLW National Library of Wales

NMM National Maritime Museum

NOED New Oxford English Dictionary

ODNB Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

SOAS School of Oriental and African Studies

TNA The National Archives

INTRODUCTION

On 12 December 1696, John Looker, a ship’s surgeon and freeman of the BarberSurgeons’ Company, departed England in a vessel which he then identified as the ‘Blackham Frigott’ for a ‘voyage from the City of London by Gods Permission to Messina Smyrna & Constantinople’.1 Prior to going aboard he had purchased a pocketbook, in which he proceeded to keep a ‘Journall’, which he maintained until 16 March 1697/8, when, as the vessel approached the Kentish Narrows, on the last stage of its homeward journey, his account breaks off in mid-sentence. Over the course of his voyage, Looker was intimately involved in the trials and tribulations of the ship’s crew and officers, and in his journal we are presented with a unique, visceral account of maritime life in the early modern Mediterranean.

Looker’s ‘Journall’, when placed in the context of what may be termed ‘maritime artisan autobiography’, as it existed in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century England –i.e. the diaries or journals kept over longer or shorter periods of time by seafaring men –constitutes an important and distinctly idiosyncratic contribution to the literature of the period.2 Such records of voyages, written by men whose workplace was on board ship, have been known, collected and published ever since the era of Giovanni Battista Ramusio (1485–1557) and Richard Hakluyt (1552–1616).3 Christopher Lloyd, in a pioneering work published half a century ago, made the reasonable observation that, ‘[o]f all sections of the community, seafaring men and agricultural labourers have been the most ignored and therefore the worst treated’ by historians.4 More recently, the shortcomings of the genre have been insisted upon by Peter Earle, who has emphasized the value, at least for the later seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, of ships’ logbooks.5 In the fifty years since Lloyd wrote, much has changed for the better in historiographical

1 The vessel is also referred to as Blackham Galley in the records of the voyage. She was in fact a galley frigate. As noted by Dear and Kemp, Ships and the Sea, p. 233, this type of frigate ‘built for the British Navy in the reign of Charles II (1660–85) was designed to take oars or sweeps as well as sails. Very few were built and, being generally inefficient, they were quickly discarded.’ They were more popular as merchant vessels, however, and Looker mentions numerous encounters with other ‘galleys’ during his voyage. For clarity and in conformity with other publications by the editors, the ship’s name will be given as the Blackham Galley in editorial commentary, with the alternate versions of her name preserved as given in the transcribed records. See below, pp. 10–13, for the history of the vessel’s construction.

2 We derive the term ‘maritime artisan autobiography’ from Amelang, Flight of Icarus, see particularly, pp. 31, 36–7, 47–50.

3 Ramusio, Delle Navigationi et Viaggi, Venice, 1588; Hakluyt, Divers Voyages, London 1582; Principall Navigations, London, 1589, 1598–1600. See, inter alia, NMM, Catalogue, vol. 1: Voyages and Travel. Records of this sort are often subsumed into wider studies of ‘travel writing’ or ‘travel literature’ rather than also receiving the recognition they need and deserve as a distinctly maritime phenomenon. See, Das and Youngs, Cambridge History of Travel Writing; Brock, van Meersbergen and Smith, Trading Companies and Travel Writing.

4 Lloyd, British Seaman 1200–1860, p. 11.

5 Earle, Sailors, p. 68.

yalleham GackBl Looker’s voyage on the

terms, and valuable work has been done by new generations of maritime historians to redress the balance in favour of those working men who ‘used the sea’ in the days of sail.1 Nonetheless, more than four centuries after Hakluyt wrote, and half a century after Lloyd, much remains to be done in identifying and publishing hitherto unnoticed material for the subject, and there are still valuable discoveries to be made. The ‘Journall’ of John Looker, now published for the first time, more than three centuries after it was written, is a case in point.2

The manuscript of Looker’s ‘Journall’ is now held at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, NMM, PHB/6 as part of the Caird Library’s superb collection. It was written in a late seventeenth-century pocketbook, on 251 of its 252 surviving pages, and is entitled: ‘A Journall of my intended voyage from the City of London by Gods Permission to Messina Smyrna & Constantinople in the Blackham Frigott. Burden 250 Tunns. 26 Guns. & 60 Men. Capt. Charles Newnam Commander. December the 12. 1696.’3 Within these pages, Looker kept what was part journal-cum-diary, part ship’s logbook. He maintained his journal episodically, day by day for the most part, and presents a systematic but often chaotic account of his journey.4 Through his text, we are presented with an narration of the Blackham Galley’s prolonged and event-filled voyage to the Ottoman Levant and back between December 1696 and March 1697/8, including the ship’s extended detention in the Ottoman port of Smyrna (Izmir) from April 1697 to January 1697/8, that ties together the practical realities of life at sea with Looker’s efforts at understanding the political landscape through which they travelled and the cultures he encountered. After it was written, the journal was never revised or reworked, and clearly it was not intended for publication by its author.

Because of this, Looker’s ‘Journall’ retains many of the fascinating details of life on board the Blackham Galley, but it can also make the journal difficult to follow in places, with chronologies and causalities presented by Looker as he came to understand them, rather than reordered into a more logical structure for readers to follow. In this introduction, therefore, we have endeavoured to provide readers with the means to contextualize, interpret and understand Looker’s ‘Journall’. The first section considers the author and his manuscript, and presents an overview of Looker’s life, the traditions and practices of biographical writing in early modern England, and the provenance of Looker’s ‘Journall’. In the second section we examine the Blackham Galley’s construction,

1 See, in particular, Adam, Seamen in Society; Fischer, Market for Seamen; Royen et al., ‘Those Emblems of Hell’; Earle, Sailors; Fusaro et al., Law, Labour and Empire.

2 For recent discoveries, see the autobiographical journal, covering the years 1682–96, written by the Franconian ship’s surgeon Johann Peter Oettinger. Koslofsky and Zaugg, ‘Ship’s Surgeon Johann Peter Oettinger’; Davies, ‘Lost Journal of Captain Greenvill Collins’.

3 NMM, Caird Library, MS PHB/6 (henceforth: Looker, ‘Journall’), f. 2r. We would like to acknowledge that Looker’s ‘Journall’ was kindly brought to Colin Heywood’s attention in 1999 as ‘a possible subject for your work’ by a London colleague, the late Dr Pat Crimmin of Royal Holloway College, University of London. Jerry Drew, an American doctoral student who, although unaware of the manuscript’s authorship, made substantial use of it in his unpublished 2002 University of Pennsylvania doctoral dissertation, ‘Entrepreneurial Warriors: Privateers in Trade and War’, 2003 (henceforth cited below as Drew, with page references to the original). We would like to express our gratitude for Dr Drew’s generous response to Heywood’s queries in the early stages of this project.

4 Looker’s ‘Journall’ is thus both maritime artisan autobiography, within Amelang’s definition of the term, and ship’s log, Amelang, Flight of Icarus, p. 31.

purchase and the details of her first earlier voyage before Looker’s arrival as ship’s surgeon. In the third, most extensive section of the introduction, we provide an overview of the Blackham Galley’s voyage as recounted in Looker’s ‘Journall’, followed by a detailed study of some of its key aspects that might be of interest to readers. Here, we consider the risks faced by early modern shipping, the political context the Blackham Galley was embroiled in, the role of social life and gossip aboard ship, the lives of the crew and their experience of health, sickness and death on ship, and Looker’s own proclivities as a traveller. A final section considers what is known of the ship and her crew after her return from the Levant in March 1697/8.

1. The Author and His Manuscript

a. John Looker: The Man behind the ‘Journall’

As for Looker himself, whose signature (or, at least, whose name) is written at the top right-hand corner of the recto of the first leaf in what is undoubtedly the author’s hand, much remains unknown. We do know that he was a surgeon and a freeman of the BarberSurgeons’ Company, most likely born in London, probably around 1670 and that he died in Bath in 1715, leaving four daughters and his widow Anne.1 Beyond these broad strokes, John Looker’s life and family history remains obscure, and his ‘Journall’ offers very little assistance in establishing further details. There are no personal letters surviving either from or to him and, as far as we know, no external references beyond those either established or tentatively suggested in the present study.

In the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries the family name of Looker seems to have been widespread in Wiltshire, with strong concentrations around Marlborough, Highworth and Chisledon; it was also represented in Sussex, around Ditchling, and, more significantly, in London. It was to this final branch, in the capital, that our John Looker most probably belonged, although it is difficult to build even a tentative picture of his family background. We may work back from one piece of hard evidence, the entry recording our John Looker’s admittance as an apprentice to the Barber-Surgeons’ Company on 3 July 1688, where he is recorded as ‘Johannis Looker filius Johannis Looker nuper de London’, apprenticed for a term of seven years to Thomas Nevett, surgeon.2 From his journal we can see that Looker was evidently familiar with nautical terminology and life at sea, indicating that at least part of his apprenticeship may have been served on ships.3 Young men starting out on apprenticeships were, on average, nineteen years old,

1 A birth or baptismal record of our John Looker has not so far come to light. He died in Bath on 23 May 1715 and was buried in Bath Abbey, see Jewers, Registers, vol. ii, p. 208, and below, p. 5. We are deeply indebted to Dr Margaret Pelling and Dr Peter Elmer for their kind assistance in elucidating the details of John Looker’s last days.

2 Barber-Surgeons’ Company, Register of Apprentices, Guildhall Library, MS 5266/2, p. 247, admission of John Looker as an apprentice, ‘tertio die Julij 1688’. Looker was one of 19 admissions on that day; others were the sons of shoemakers, porters, a ‘cloathworker’, vintner, maltster, from Nottingham, Stafford, Dover, and St Martin’s in the Fields, London. John Looker senior, described here as ‘nuper de London’, meaning ‘lately of London’, was either deceased or no longer resident in the city by 1688.

3 According to Rodger, Wooden World, pp. 27, 173, 177, it was not uncommon for masters to have apprentices pressed into the Royal Navy during their training. This may have been the case with Looker, or he may have served on a merchant vessel in a similar capacity.

suggesting that Looker was born sometime in the late 1660s or early 1670s.1 We also know, from his ‘Journall’ entry on Tuesday 8 March 1697/8, when the Blackham Galley was homeward-bound in dirty weather in the Soundings, that ‘this being my Birth day … I treated our officers with some Malaga wine’.2 He would then have been in his late twenties. Beyond these data, we cannot confirm any further details regarding Looker’s parents or childhood, and on the rare occasions when he mentioned writing letters to England, he identified among family members only his ‘Aunt Yates’.3

After his voyage on the Blackham Galley, John Looker would come to settle down in London, where ‘John Looker bachelor’ is recorded as marrying ‘Anne Allen spinster’ on 13 February 1699/1700 at St Dionis Backchurch.4 From this marriage record, we know that John was a resident of St Peter Cornhill parish in London, where he would remain until he removed to Bath some time before his death. Anne Looker, née Allen, had previously resided in St Stephen Coleman Street parish. Together, they raised a number of children, including four daughters who were still alive when he died in 1715. One son, John, had died in 1706, and two daughters, Anne and Elizabeth, had died in 1708 and 1710 respectively.5 In his will, ‘John Looker surgeon’ distributed his estate, including prominently a manor at Hiptofts in the parish of Wisbech St Mary in the Isle of Ely, and detailed the members of his extended family.6 His brothers-in-law, John Allen and Edward Allen, were appointed, once Looker’s children reached twenty-one years of age, to sell the manor and divide the money between his wife Anne (who would receive half of the total) and his four surviving daughters (who would divide the rest). To his sister Elizabeth Allen, Looker gave £5 per annum, to be drawn from his estates, and he forgave all debts that his brother, Thomas Looker, still owed at the time of his death. His brothersin-law Edward Ankers and John Beckett were similarly relieved of their debts.7 Looker also likely had two brothers or cousins, James and William Looker, referred to in Elizabeth Looker’s will from 1723.8

b. Looker’s ‘Journall’: An Example of Artisanal Autobiography

When he shipped on board the Blackham Galley in December 1696, our John Looker was probably in his mid-twenties, and only some months previously had been released from his apprenticeship. Nonetheless, based on the language of his ‘Journall’, we can glean more about Looker’s life and better understand the context and content of his account. It is through his speech, as preserved herein, that we may gain further insight into John Looker’s East London origins and what may be termed his social culture. Furthermore, when he boarded the Blackham Galley on 12 December 1696, he was already fully

1 Rappaport, Worlds within Worlds, p. 295; Wallis, ‘Apprenticeship and Training’, pp. 846–7.

2 8 March 1697/8, see below, p. 191.

3 On 19 July 1697, below p. 108. Looker notes ‘This day I writt to my Aunt and Mr Thomas Yates in England by the Valentine, a French Merchant man bound for Marselles.’ Unfortunately, there is not enough information to further identify Looker’s aunt or Thomas Yates.

4 LMA, P69/DIO/A/001/MS017602. Reiester booke of Saynte De’nis Backchurch, 1538–1812, Harleian Society, Registers, vol. III, 1878, p. 48

5 LMA, P69/PET1/A/001/MS08820 St Peter upon Cornhill, register of baptisms, marriages, and burials, 1538–1774.

6 TNA, PROB11/546/326 drawn up 8 Feb. 1714/15; probate granted 15 June 1715.

7 Ibid.

8 TNA, PROB11/593, Will of Elizabeth Looker, 12 Sept. 1723.

conversant with the terms and language of seafarers which have to do with navigation and the sea, terms which were an arcana to any landsman unconnected with a maritime environment. As William Matthews noted in a seminal article published more than eighty years ago, ‘the sailors of the 17th century were notorious for the strangeness of their speech’.1

James Amelang has observed that in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries ‘virtually all autobiographical writing by craftsmen insisted on being one thing: plain’. He adds that ‘plain style meant simplicity’ and the absence of ‘artifice, decoration, adornment, even literary effort itself’.2 The style and language of Looker’s ‘Journall’ exactly conforms to this dictum. In its opening entry we are plunged straight in, without any personal or contextual introduction:

1696. December. 12. Satterday about 2. a clock in the after noone I took water at Billingsgate in a Graves End boate for Graves End. The wynd being very high & a great Quantity of Ice in the River in so much that our boate stuck & we were neere 3. hours before we arrived to Blackwall where the Ice was cleare. then we had an Easy Passage to Graves End making use of noe oar only our Sailes at ½ an hour after six in the Evening3

From here, the ‘Journall’ continues with the departing from the Downs on 11 January ‘with a favourable Gale about 2 a clock in the afternoon’, as Looker began to keep the daily journal of the ship’s progress which he would maintain until almost the conclusion of the voyage. On the third page, Looker provided as a title, in a full-page entry, ‘Here Followeth my / Journall of every Dayes / Transactions from the / Downes’, and headed the first day’s entry (for 11 January; page 9) ‘Ad majorem Dei Gloriam’.4 Thereafter, for virtually all the periods of the voyage when the Blackham Galley was at sea, Looker’s ‘Journall’ combines the function of a shipboard diary with that of a log, with entries for ‘Course’, ‘Distance’ and ‘Wynd’ entered, in greater or lesser detail, either in parallel ruled columns adjoining the text, or as a heading to the daily entries. For the first, twelve-day stage of the Blackham Galley’s outward voyage, from the Downs to Cadiz, the ‘Journall’ presents a bare and impersonal account of the ship’s progress, limited to describing the weather and other vessels encountered en route. This fits in with what Amelang terms ‘self-narrative that was not about the self, personal writing that was impersonal, and autobiography before it became “autobiographical”’: Looker records nothing about himself nor does he mention the captain or any other members of the crew.5

This laconic and abrupt style remains for much of the ‘Journall’, revealing a writing practice on the part of Looker that fully illustrates what Amelang defines as ‘an important by-product of the natural style in popular autobiography’ that can be seen in ‘its frequent disregard of the conventions of spelling, punctuation, accentuation, and rules of grammar’ to produce ‘unlearned’ and what may rightly or wrongly be called ‘phonetic’ spelling and

1 Matthews, ‘Sailors’ Pronunciation’, p. 193

2 Amelang, Flight of Icarus, p. 155. Koslofsky and Zaugg, also comment on Oettinger’s ‘rather dry and often elliptic style’ in ‘Ship’s Surgeon Johann Peter Oettinger’, p. 41.

3 ‘Journall’, f. 2r, see below, p. 41, and the section on the conventions adopted in editing the text, p. 38.

4 This Latin entry is likely what prompted Sir Thomas Phillipps to make the pencil note ‘Written apparently by a Roman Catholic, He seems to have been the Surgeon’ on f. 1v/p. 2 of the ‘Journall’. See below, p. 10, and Plate 6.

5 Amelang, Flight of Icarus, p. 249.

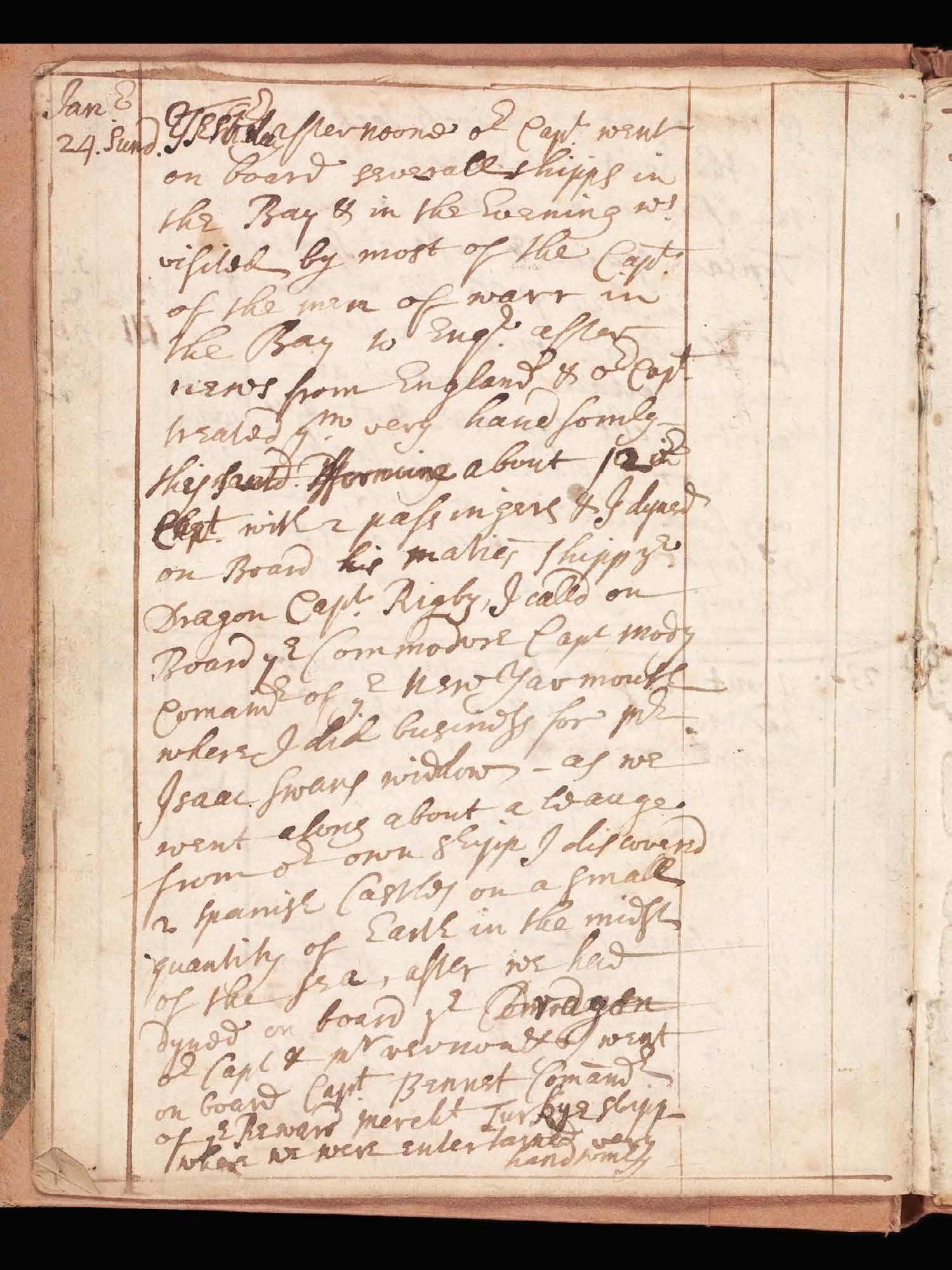

writing.1 The same approach can be seen in the journal’s content, which, although maintained systematically throughout the journey can be chaotic and inconsistent in terms of the sort of information recorded or the addition of contextual material. In places, the text is virtually illegible because of deletions, additions and overwriting as Looker strains to include all the information he thinks is important.2 Indeed, this also indicates that the ‘journall’ recorded by Looker is a personal one, not reconsidered or rewritten later for submission to his superiors or for publication.

To demonstrate this point, it is worth taking the time to examine the mutability of Looker’s stylistic approach at different points during they voyage. For example, the Blackham Galley’s arrival at Cadiz brought a sudden shift from a solitary life at sea to a social life in port and Looker’s narrative style shifts in recognition of his changing experience. Writing up his ‘Journall’ on 24 January 1696/7, a Sunday, he notes that ‘Yesterday, after noone’ – i.e. immediately after the ship anchored off the Diamond –‘our Captain went on Board severall shipps in the Bay and in the Evening was visited by most of the Captains of the men of warr in the Bay to enquire after news from England’. Looker now, for the first time since leaving England, brings himself into the narrative, recording that ‘about 12 [noon on Sunday]’ Captain Newnam, two unnamed passengers and he himself dined on board HMS Dragon (Captain Rigby). Looker adds that he had also called on board the New Yarmouth (Captain Moody), ‘where I did business [unspecified] for Mr Isaac Swans widow’. After dining on board the Dragon, Newnam, Looker and a Mr Vernon, one of the passengers, went on board the ‘Turkye shippe’ Reward Merchant (Captain Bennet), ‘where we were entertained handsomly’ until about ten at night, when the party, returning on board the Blackham Galley’s eight-oar pinnace, was unable to make headway against a strong tide and were forced to take shelter on the Canterbury Merchant, about two miles distant from their own vessel, where with some difficulty they got on board, ‘I hanging by the side rope between wynd and water till the men brought the boat to’.

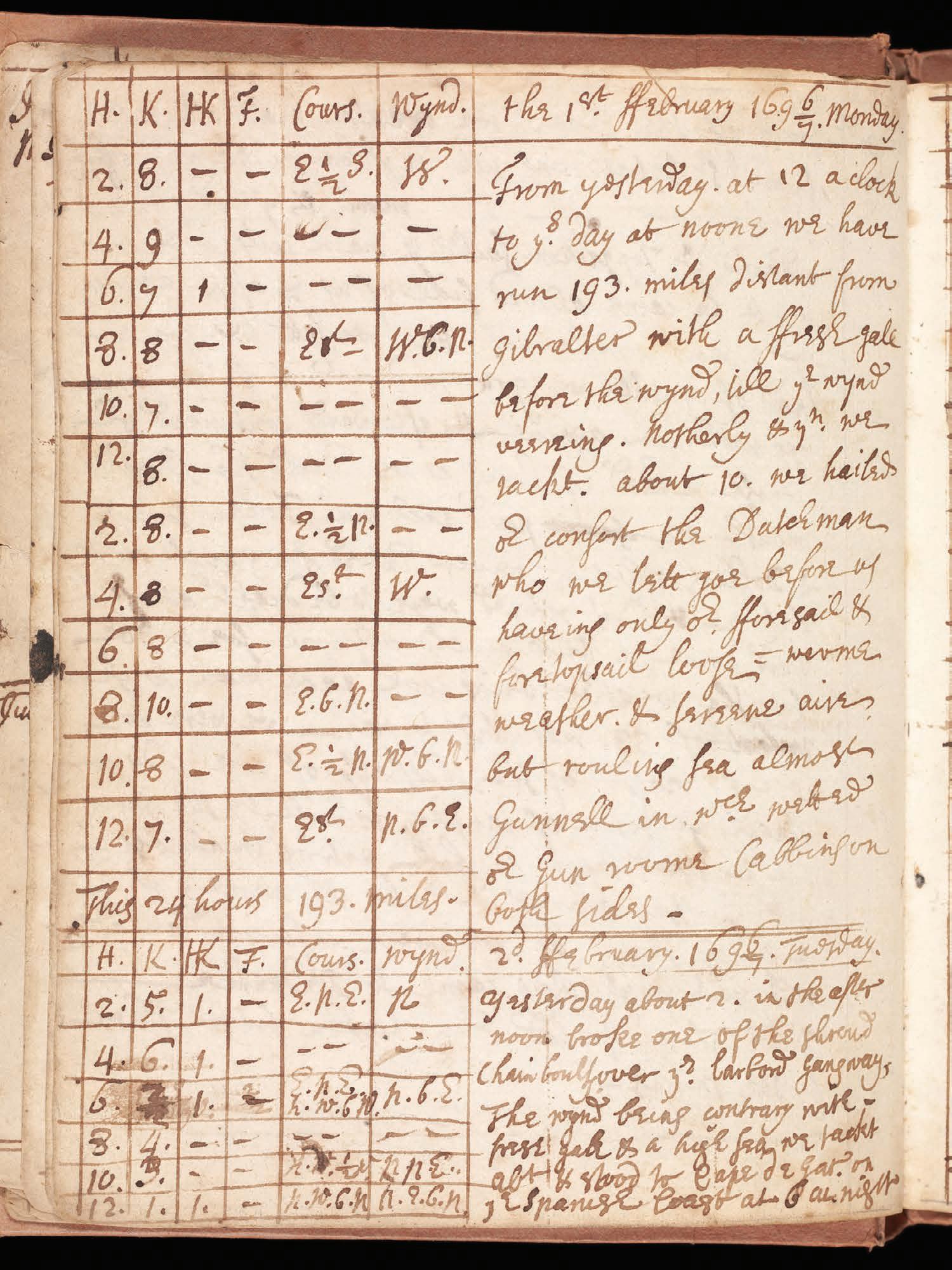

As soon as they departed Cadiz, however, on 1 February, Looker recommenced his intermittent habit, when the ship is at sea, of entering in tabular form the details of her daily passage, on the left-hand side of the page, recording some or all of the details of her speed, course and the prevailing wind every two hours, and adding at the foot of the table the estimated distance run in the previous 24 hours.3 In his daily journal entry, written on the right-hand half of the page, Looker paraphrases and adds further details to the data from the log, e.g. (for 1 February): ‘From yesterday at 12 a clock to this day at noone we have run 193 miles distant from Gibralter with a fresh gale before the wynd, till the wynd veereing Northerly and then we tackt’.4 One consequence of this stop-start approach to Looker’s more detailed, personal style, is that sections of the text offer almost nothing to the reader beyond the data we would expect from a ship’s log. For instance, Looker’s account of the two and a half weeks’ return voyage from Smyrna to Messina in the first weeks of 1698 is a bleak one, a detailed record of wind and weather, landfalls and storms, but one entirely devoid of reference to any living persons. In the ten pages of the

1 Ibid., p. 158.

2 For example, Looker’s entries for 21, 22, 23 July 1697; 27, 28 Feb., 1 March 1697/8, see below, pp. 109, 188–9, and Plate 3.

3 See below, p. 52 and Plate 4.

4 See below, p. 52.

‘Journall’ which he devotes to this passage from the west coast of Anatolia to Sicily, Looker makes no mention of himself or of any other member of the crew.

All this reticence suddenly dissipates once the Blackham Galley is (with some difficulty) moored and made fast to the quay at Messina. Suddenly Looker’s tone becomes humanized, heavy with quayside gossip of ships and their commanders: Jonas Cock, commander of the Delavall Galley, shot himself with three pistols while at sea; Captain Young, of the De Grave, lost all his crew through desertion; Captain Boxer lost his settea while on the way from Livorno to Messina, but saved his crew, and so forth. Nor was Looker’s enthusiasm for recording news limited to that related to fellow Englishmen, and as he encountered new places and new peoples in the Eastern Mediterranean he likewise took care to intimately recount their practices and culture. For example, during his time in Smyrna in March 1697, Looker described what he understood of the local Greek culture and was clearly fascinated by the ribald, dramatic community that he encountered:

There are abundance of whores & pimps among the Greekes, which generally liv in a place without the City which they call the Gardens. They all paint & patch & dress themselves in their haire with flowers & ribbonds & keepe their secretts shorne. They live in little hovells in a place lockt in at night, which they call Canes. Some tyme before our arrival there was a Turke who would have ravished a Greekes woman, but she preventing him he swore a revenge & therefore finding an opportunity killd both her & her child. Her husband fynding him, brought him to the cheif officer of the Town, who told him without any further tryall hee might execute what he pleased upon him, & the poor Greeke immediately brought him into the markett place & cutt off the Turkes head with a Scimitar with his own hand, which putt the Turkes in a great uproar such a thing being never known before, but the poor Greeke goes in danger of his life.

As can be seen in the overview of the voyage detailed below, and in the text itself, the strictly plain stylings of Looker’s journal while the ship is at sea quickly disappear when he found himself on land. It is during these periods that that Looker, in spite of his leanings as an artisanal biographer, offers such startling, visceral accounts of life in the Mediterranean, not only of his own experiences, but of the English crew aboard the Blackham Galley and on shore, and of the local people encountered in the several ports, from Malaga to Istanbul, at which the ship called.

c. Looker’s ‘Journall’: The Provenance of National Maritime Museum MS PHB/6

In order to keep his record of life aboard the Blackham Galley, John Looker acquired a blank pocketbook for the purpose of maintaining his ‘Journall’. This pocketbook, now kept at the National Maritime Museum, measures exactly 6 inches (15.5 cm) wide by 8 inches (20 cm) high. When it was new, it probably contained 132 leaves. At present it comprises 129 leaves, or 258 pages. The text of Looker’s ‘Journall’ occupies all of the manuscript except for the first leaf and the verso of the final one. The author’s signature or name, written in the same hand, and using the same ink as the majority of the manuscript, is found on the upper right-hand corner of the recto of the first leaf. The original blank book appears to have been made up in eleven sections (1–11; one would have expected twelve), each containing twelve leaves, except for section 1, which appears to now have only nine.1 One leaf, between the present pages 8 [blank] and 9

1 Thus, giving a book of 12 × 12 = 144 leaves (a stationer’s gross) and 288 pages.

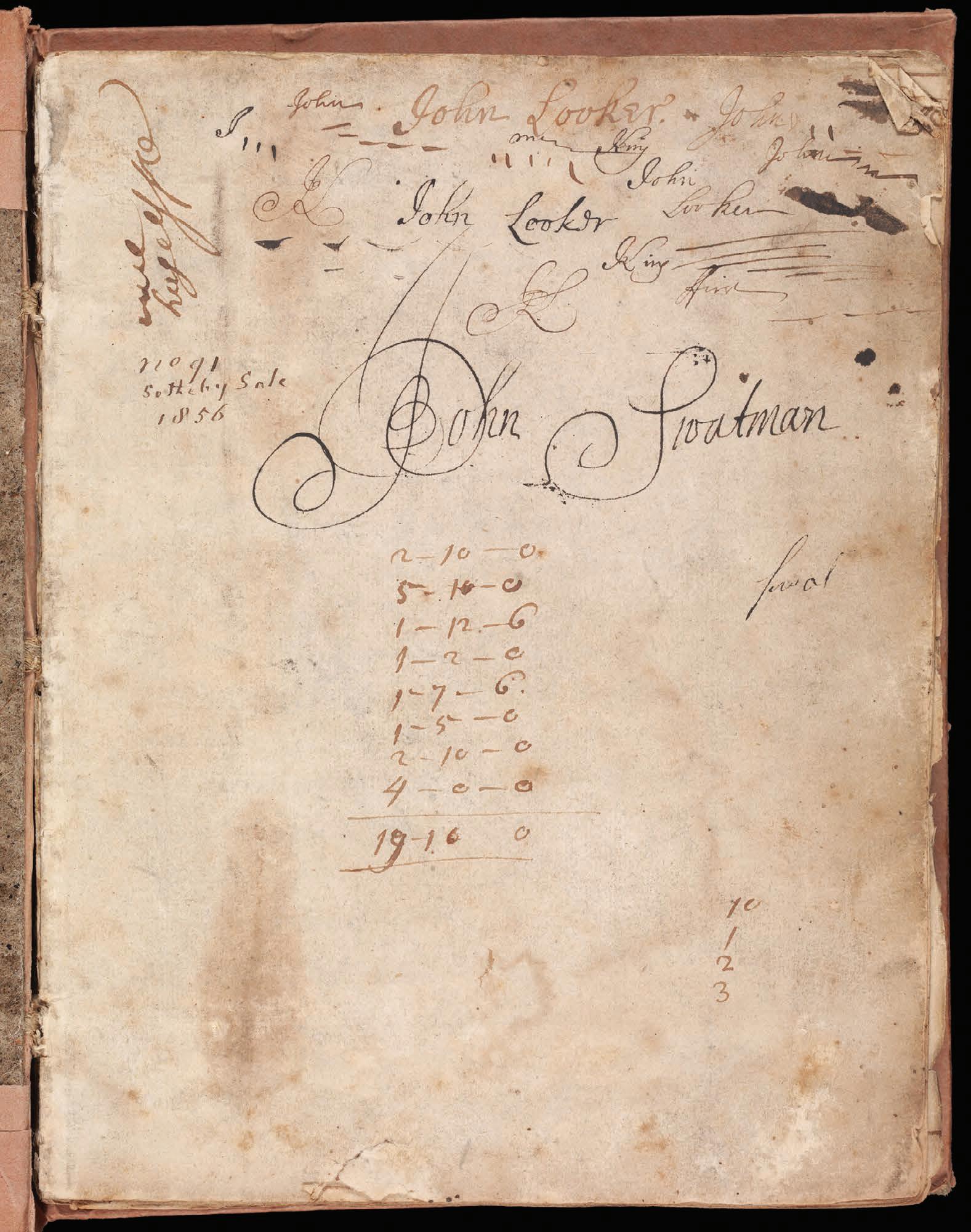

Plate 1. The first page of Looker’s ‘Journall’ that records ‘my intented voyage from the City of London, by Gods Permission, to Messina, Smyrna & Constantinople in the Blackham Frigott’ and his departure from England in December 1696. Courtesy of the NMM, Greenwich, London.

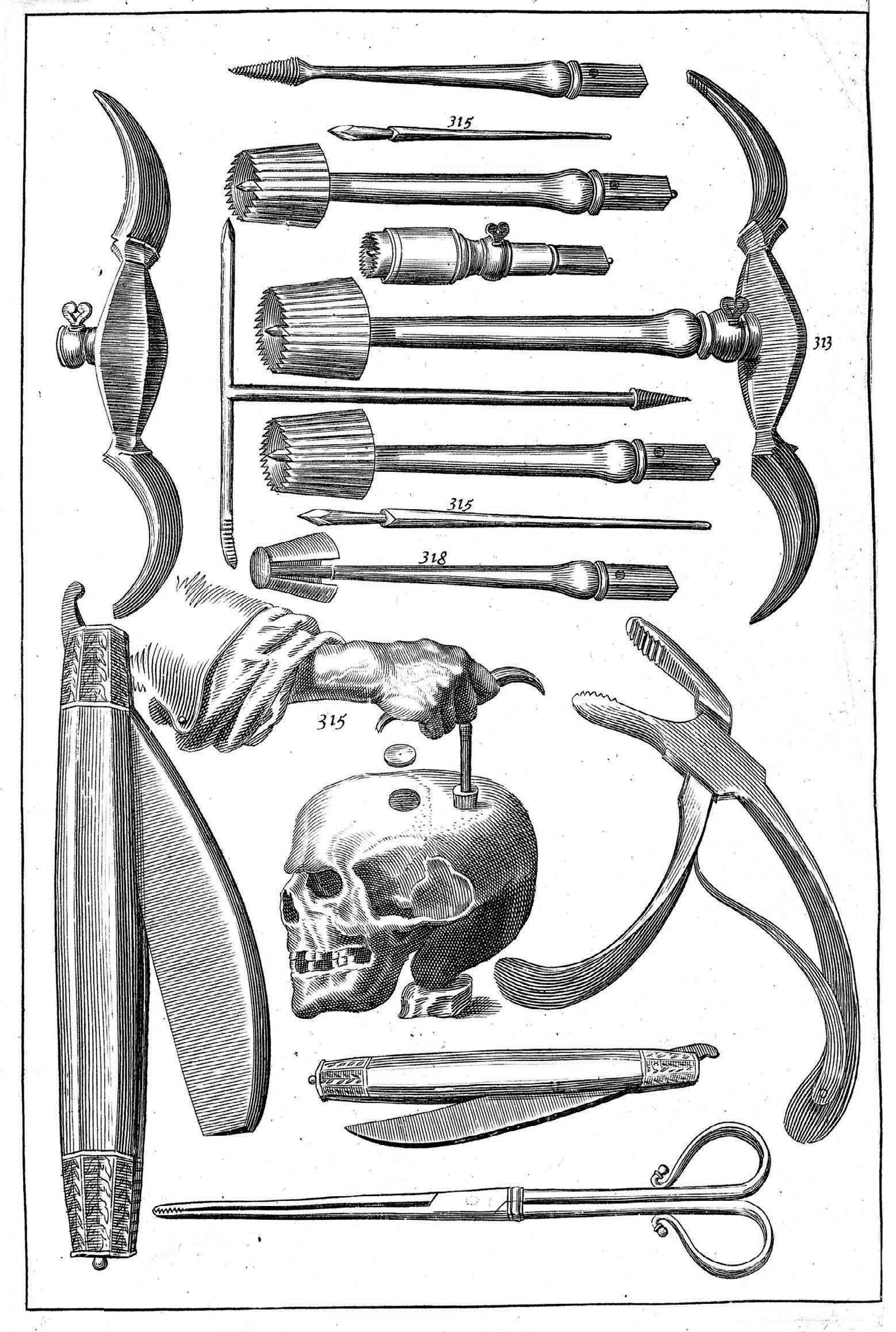

Plate 2. Seventeenth-century surgeon’s tools as depicted in John Woodall, The Surgeons Mate, 1639. The tools represented here are likely similar to those carried by Looker during his time on the Blackham Galley, on which he served as ship’s-surgeon. These would have been used in the surgical procedures which he describes, often graphically, in his ‘Journall’. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Plate 3. An example of Looker’s corrections made when revising his entries. Looker regularly crossed out, corrected and overwrote the text in his ‘Journall’, as can be seen on this page. Courtesy of the Royal Museums, Greenwich, London.

Plate 4. Looker’s early detailed tabular record of the ‘way made’ by the Blackham Galley. While the Blackham Galley was at sea, Looker’s journal often shifts to a tabular format, as shown here, where he carefully recorded the course and speed of the ship as it traversed the Mediterranean. When in port he returned to mainly text entries, as seen in Plate 3. Courtesy of the Royal Museums, Greenwich, London.

Plate 5. The first leaf (recto) of Looker’s ‘Journall’ showing his signature (at the top of the page), also that of John Swatman who was likely a subsequent owner of the ‘Journall’. Courtesy of the Royal Museums, Greenwich, London.