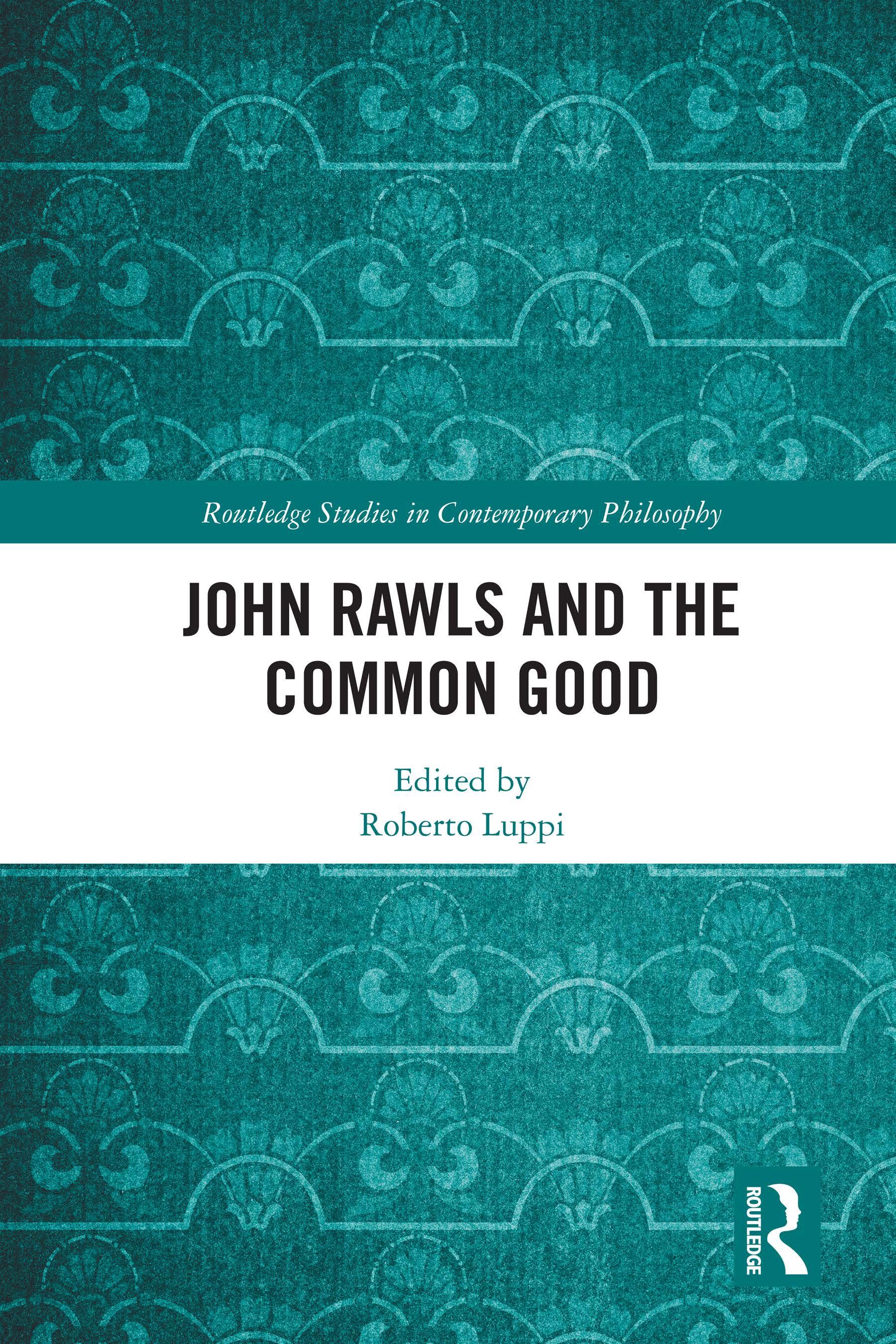

John Rawls and the Common Good

An Introduction

Roberto Luppi

This book celebrates an important anniversary in contemporary philosophy: 50 years have passed since the publication of one of the most infuential works of the last century, A Theory of Justice by John Rawls ([1971] 1999a), a book that signaled a real watershed moment in its feld of research, as a result of which “Political philosophers . . . must either work within Rawls’ theory or explain why not,” as Robert Nozick remarked (1974, 183). Rawls’s theorizing was the basis for the afrmation of a particular vision of liberalism, one that was aimed at both protecting individual freedoms and promoting the economic and social bases of equality. This vision has been extremely infuential in the philosophical refection of the last 50 years, on issues such as justice and reciprocity, society and institutions, equality and freedom, generating discussions among thinkers belonging to a broad range of theoretical convictions, nationalities, and cultures.

As the title suggests, however, this book aims to celebrate the 50th anniversary from a perspective, which has rarely been applied to the philosopher’s thought, namely that of the “common good.” Since the 1980s, in fact, one of the focal points of the debate surrounding Rawls’s work has been the so-called communitarian critique of liberalism. Indeed, great philosophers such as Alasdair MacIntyre, Michael Sandel, Michael Walzer, and Charles Taylor have accused Rawls and liberalism more generally of relying on an individualistic and abstract vision of human beings (or “unencumbered selves,” as Sandel writes), thus overlooking central aspects of collective life related to the concepts of community, virtue, civic friendship, solidarity, and so on.1 In short, one of the principal subjects of said criticism was the Rawlsian ‘lack of interest’ in the concepts and values that refer to the common good.2 This position is aptly summed up by David Hollenbach:

the idea of the common good is in trouble. John Rawls speaks for many observers in the West today when he says that the pluralism of the contemporary landscape makes it impossible to envision a social

good on which all can agree. This is the intellectual and theoretical challenge to the common good today: diversity of visions of the good life makes it difcult or even impossible to attain a shared vision of the common good. Such a shared vision cannot survive as an intellectual goal if all ideas of the good are acknowledged to be partial, incomplete, and incompatible. This pluralism also makes it impossible to achieve a strong form of social unity in practice without repression or tyranny. This is the practical challenge: pursuit of a common good as envisioned by Aristotle, Aquinas, and Ignatius must be abandoned as a practical social objective incompatible with modern freedoms.

(Hollenbach 2004, 9)

Although Rawls has often been the main subject of these communitarian objections, they constitute a more general critique of liberalism. With this term, we refer here to that philosophical doctrine, which initially spread throughout Europe following the religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries and tried to limit the power – and, at times, abuses – of government (especially in the form of absolute monarchy), guaranteeing citizens equal freedoms and rights, which gradually came to be recognized as inviolable. At the root of this doctrine was the awareness that people naturally tend to disagree on central issues of their existence, starting from the idea of ‘the good life.’ Being reasonable has thus ceased to be seen as a guarantee of unanimity, and it has been accepted that, in matters of supreme importance, people are destined to disagree. By virtue of this conviction, the decisive question for liberal theory has thus shifted from the defnition of an idea of good, which a community must pursue, to the development of just and fair terms of coexistence, which are then accompanied by the adopting of diferent conceptions of the good life by individuals (Larmore 1996, 121–123; Schwarzenbach 2009, 18–20).

As stated by a signifcant portion of the liberal tradition, consequently, rather than to personal ends and interests, or the development of ideals of human perfection in citizens, the state should turn its attention to maintaining peace and order, the protection of rights and of individual freedoms, and the promotion of material prosperity. In short, liberalism has afrmed the need for state neutrality toward the worldviews of its citizens. This is highlighted by Dworkin, among others:

It is a fundamental, almost defning, tenet of liberalism that the government of a political community should be tolerant of the diferent and often antagonistic convictions its citizens have about the right way to live: that it should be neutral, for example, between citizens who insist that a good life is necessarily a religious one and other citizens who fear religion as the only dangerous superstition.

(Dworkin 1995, 191)

State neutrality toward the diferent visions of good is believed – especially by the critics of liberalism – to be coupled with the afrmation of individualism (and self-interest) on the social level. They sum up the liberal society in the image of an agreement between individuals characterized by a plurality of goals and conceptions of good and who share little or nothing except the common concern for self-preservation and the pursuit – or safeguarding – of prosperity. Due to their accentuated individualism and the exaltation of autonomy and independence at the expense of afliation and collective action, these societies are accused of taking the form of a summation of self-referential individual rights and interests, in which the intervention of the community, and especially of the state, appears as a continued interference in the free action of the individual – tolerated almost exclusively in areas such as public order, in which the impossibility of single persons to individually achieve the desired results is manifested. The liberal state is thus charged with creating “isolated, monadic citizens who care only about their own good, little about the welfare of their fellows or their overall political community, and who generally lack the civic virtues needed to sustain a viable liberal polity” (McCabe 1998, 558).

The inevitable result of this overall image – so the critics go on – is thus the impossibility of the liberal state to stimulate the pursuit of the common good. The latter must be considered the good of the community as a whole, as a social body, and not as the mere sum of the goods of individuals. It takes the form of a moral attitude, which consists of a set of shared values concerning what we owe one another, as citizens who are bound together in the same society, and reminds people of the importance of interpersonal bonds, virtues, and collective action in view of personal fourishing and societal welfare. The achievement of this kind of good is thus seen by some as irreconcilable with the life of a liberal society. In this regard, Galston writes:

Liberalism is said to undermine community, to restrict unduly opportunities for democratic participation, to create inegalitarian hierarchy, and to reinforce egoistic social confict at the expense of the common good. Community, democracy, equality, virtue – these constitute the mantra of contemporary antiliberalism.

(Galston 1991, 42)

In contrast to what has been argued by many critics, this book attempts to fnd some form of reconciliation between the liberal tradition and the concept of the common good, preserving the great achievements of liberalism – such as the afrmation of freedom and rights, political and religious tolerance, and interpersonal respect – at the same time combining them with the key values of the common good. Such an attempt will be developed through the analysis of one of the greatest liberal thinkers of the last century: John Rawls.

Over the years, there have been attempts to demonstrate the presence of common ground between Rawls and scholars working within a communitarian perspective or, in any case, to highlight that the framework created by the philosopher cannot do without concepts akin to those that give substance to the defnition of the common good. With this book, we do not want to return to the debate, which has animated the communitarian critique of liberalism; this can now be considered long concluded. Nor does this work aim to ofer an incontrovertible demonstration of the possibility of a communitarian interpretation of Rawlsian theory. Fifty years after the frst publication of A Theory of Justice, however, an exhaustive and general analysis of the relationship between Rawlsian thought and the crucial values, which are constitutive of the idea of the common good, is still needed: this is precisely the purpose of this book.

It is Rawls himself who, in A Theory of Justice, emphasizes that he aspires to fnd a balance between certain individualistic aspects of his theory of justice and the value of the community, deeply connected with the “social nature of mankind” (TJ, 458):

justice as fairness has a central place for the value of community, and how this comes about depends upon the Kantian interpretation. I discuss this topic in Part Three. The essential idea is that we want to account for the social values, for the intrinsic good of institutional, community, and associative activities, by a conception of justice that in its theoretical basis is individualistic. . . . From this conception, however individualistic it might seem, we must eventually explain the value of community. Otherwise the theory of justice cannot succeed. (TJ, 233–234, emphasis added)

The idea underlying this book is that Rawls (at least in part) succeeds in his attempt, and the demonstration of this is ofered by a groundbreaking examination of the values that most distance the philosopher’s work from a purely procedural reading, thus seeking elements of dialogue and intersection between the concept of the common good and his philosophical system.

I. Rawls and the Common Good

A fundamental feature of the common good is that it is internal to the requirements of a social relationship (Hussain 2018). In every community, it must be understood as the culmination of a model of practical reasoning, which fosters the establishing of a political and social relationship among citizens, aimed at attending to the central afairs of their coexistence. However, one of the fundamental aspects of this idea lies in its difcult – perhaps impossible? – defnition. It is one and multiple, and its edges are always blurred; at times, it is almost a feeling, destined to remain

in the form of an inspiring ideal of collective action, but never entirely discernible or achievable in full. As Sluga writes:

we can envisage the common good in very diferent ways, as high and as low, as wide and as narrow. We can speak of this common good in the language of justice, of freedom, security, order, morality, happiness, individual well-being, prosperity, progress, and what have you. We can, moreover, envisage the community for which such a good is sought in diferent ways: as tribal, local, national, international, or even global, as egalitarian or hierarchical in its order, as traditional or freely constituted, as unifed or divided. And we can fnally also envisage the search itself in various ways: as organized or spontaneous, as guided or as cooperative, as deliberate or merely implicit, as successful or thwarted.

(Sluga 2014, 2)

In the history of political thought, its manifold nature has made it possible to trace the common good in a plurality of theories. From ancient Greece to Christian thought, the common good has often been interpreted as the testing ground against which not only the formal legitimacy but also the intrinsic goodness of any form of government is measured. The common good has thus been observed as a category that is both ethical and political – spheres that are seen as intertwined (Campanini 2014, 16–17). It is precisely this last connection that the political culture of modernity has tended to reject, focusing the overall evaluation of state power more on legitimacy than on value judgments. Inevitably, this development has contributed to the gradual loss of centrality of the concept of the common good in political and philosophical refection.

However, in the second half of the 20th century, this concept was gradually rediscovered through the work of scholars interested in both the Christian tradition and classical philosophy. Hand in hand with this rediscovery, important disaccords with large sectors of the liberal tradition have nevertheless surfaced, preventing the revival of the common good as a basic element of contemporary philosophy. As outlined earlier, one of the distinctive features of liberalism is in fact the recognition of ethical, religious, and philosophical pluralism as a central and irrepressible, or rather welcome, trait of today’s societies. Related to this is the spreading of both religious and political tolerance as a crucial element in order to allow peaceful coexistence and cooperation within plural communities. A signifcant portion of the liberal tradition has often considered these two very elements, pluralism and the related practice of tolerance, as difcult to reconcile with the idea of the common good, which instead is believed to rely on a solid social bond, which can only be ensured by the sharing of the same idea of good within community (Downing and Thigpen 1993, 1050).

The fracture that has emerged between ethics and politics must therefore be looked upon as one of the principal reasons for the ‘crisis’ of the concept of the common good and its subsequent relegation to the background, in the context of liberal philosophical contemporaneity. However, it is possible to imagine the rediscovery of this concept based on the idea of morality , rather than that of ethics . Here, morality is understood as that sphere, which includes citizens’ collective and public life, the sphere that is connected to their system of cooperation and its rules, practices, and virtues. If, given today’s pluralism, it is impossible to fnd a common good, which comprehensively absorbs the lives of citizens, related to their idea of the good life, we can trace it in what is authentically common to the whole community: indeed, its morality. This is the idea John Rawls refers to in his interview for Commonweal in 1998. When asked about the presence of an idea of the common good in his theory, he replied:

You hear that liberalism lacks an idea of the common good, but I think that’s a mistake. For example, you might say that, if citizens are acting for the right reasons in a constitutional regime, then regardless of their comprehensive doctrines they want every other citizen to have justice. So you might say they’re all working together to do one thing, namely to make sure every citizen has justice. Now that’s not the only interest they all have, but it’s the single thing they’re all trying to do. In my language, they’re striving toward one single end, the end of justice for all citizens.

(CP, 622)

What emerges is the conviction that a liberal state, while active in preserving the neutrality among the various conceptions of the good, is able to ofer its citizens a fundamental end in relation to which they can act collectively: it is the “mutual good of mutual justice” (Rawls 1988, 274). The Rawlsian idea of the common good is therefore characterized by interests that the members of a community can publicly welcome and intrinsically value by virtue of their status as citizens, committed to respecting the principles of public morality. This status takes precedence over other statuses and afliations that characterize the identity of the individual as a private person. Citizens are thus deemed to have a relational obligation to mutually take care of the interests connected to the “position of equal citizenship,” shared by everyone (TJ, 82–83, 217). These interests concern the respect for and protection of the principles of justice and the institutions that are inspired by them. The status of equal citizenship and its mutual recognition are crucial, above all, in order to highlight what unites all members of the community, partially setting aside diferences and divisions and preventing – as far as possible – the rise of social envy and erroneous competition among individuals and groups (Hussain 2018).

In essence, a conception of social life is put forward by Rawls, by virtue of which everyone has a fundamental interest in ensuring that certain basic social conditions prevail. The discussion, deliberation, and action of citizens with a view to the common good allow them to afrm a principle of reciprocity (and civic friendship) that leads everyone to give and receive justice and mutual consideration. Thus, while not (necessarily) adopting supererogatory attitudes, each individual plays their part in a collective dynamic in view of the interests of their associates, as these interests are common to all. Moreover, this kind of society ofers everyone the possibility to realize their personal conception of the good, in the form of their life plans. These goods should not be seen as exclusively private but often shared within the multiple associations that make up the social body. In this plurality of life experiences, citizens feel pleasure and pride and “realize their common or matching nature,” which in turn is inevitably part of the common good of the Rawlsian community (TJ, 459; cf. Keys 2006, 35).

In this book, we will see how referring to justice as the basic framework for the common good opens the door to other values and concepts, which, although connected to justice itself, have much more substantive features than those acknowledged by the critics of John Rawls. Contrary to the idea that he understands justice as “a rather limited good; [as] the good of a cold, modern, and essentially heartless world in which the issue between us is only what you owe me and what I owe you,” the book will explore the far from marginal role that concepts, such as for example that of virtue, friendship, faith, or fraternity, play in the theory of justice of the philosopher. In line with this perspective, readers will thus judge for themselves whether the Rawlsian theory actually provides a “particular, distinctively narrow, and essentially Protestant view of the common good” or not (Sluga 2014, 3–4).

Here, however, it is important to dwell – albeit briefy – on another point, that is to say on whether the vision set out in this work is truly able to speak to today’s society, a society that since 1971 has undergone tremendous changes: technological revolution and globalized capitalism, surveillance and interdependence, digital democracy and populisms, new inequalities and balances of power, migration and climate change are just some of the crucial features of today’s global village, which now takes on a very diferent appearance from that of John Rawls’s time. Yet the idea from which this collective work springs forth is that the philosopher’s thought continues to speak to us and to ofer important insights on debates so crucial to the history of humanity that they are likely destined to endure forevermore, such as those on justice and freedom, equality, and the common good. It is precisely on this last concept that doubts, questions, and criticism will likely focus: does it still make sense to talk about the common good in a globalized world like today’s, in which its traditional frames of reference (family, city, and state) seem to gradually

lose importance? And if so, is it not necessary to embrace a universal perspective on the common good, given the growing interdependence between the various areas of the world and the peoples who inhabit them? At the same time, however, does such a universal perspective not render this concept meaningless?

On the one hand, what arises is the thought that a common good referred only to the polis, as in the ancient world, or to the nation, as in the modern world, no longer makes sense in the era of globalization and with the arising of problems, which require a global vision. Environmental issues and COVID-19 represent only two, albeit very relevant, examples in this regard. On the other hand, however, it is possible to put forward the opinion that the global broadening of the concept of the common good leads to such a ‘softening’ of its contents, as to render them devoid of meaning and power of infuence.

This book does not take a stand on the possibility of rethinking the concept of the common good from a global perspective or otherwise. This approach is not taken into consideration here for (at least) two reasons: one, linked to the philosopher at the center of the analysis; another of a more general nature. In fact, adopting an approach that cost him greatly in terms of criticism, Rawls devoted his refection predominantly to the state as a single entity, going in search of a political conception of justice that was applicable within a constitutional democracy seen as an island, separate and independent from any surrounding realities. Only later, in The Law of Peoples, did he move on to consider issues of international politics, which ultimately occupied a rather marginal space in the general structure of his thought. This leads to the adoption of a more traditional perspective on the common good here, addressing the community – at most, on a national scale – but certainly not humanity as a whole. Second, at a time in which the implementation of a policy aimed at the common good appears so necessary and yet, concurrently, so distant, it might be advisable – even from a theoretical point of view – to focus on the state level rather than on a macro reality, such as a global one. Although this is an approach that will not please some, the essential idea is that, when a house is in disarray, as our beloved humanity in many ways is, to put things in order one must frst concentrate on the single rooms and then, only subsequently, should one focus on the whole. It is already difcult to reconcile the ‘good’ of a local reality with that of the state, given recurring tensions and conficts, be they apparent or hidden. Even more complex issues arise when the criterion of the common good is transferred to the level of political, economic, and social choices to be adopted on the world level. Nevertheless, as the example of the house brings to light, they are not conficting or incompatible types of good: in order to be sustainable, in fact, the common good of a country must not be thought of in contrast with that of other state entities, near or far from it. Rather, the two types of common good are complementary and – in some ways – follow on from one another.

II. Chapter Outlines

In short, is it possible to trace an idea of the common good in John Rawls’s thought? This work concludes that it is. Although he uses this term with absolute parsimony, my opinion – and I venture to say also that of the other contributors – is that Rawls has outlined a specifc idea of the common good for his well-ordered society. A common good that is inextricably linked to the idea of justice, but which must not be understood as something ‘monolithic’ and ‘well-circumscribed’ or ‘circumscribable.’ I rather like to think of it as a mosaic , never defned in its entirety and made of multiform pieces: some larger and well-polished, others smaller or faded in color; all, however, equally fundamental in order to build the greater, overall image depicting the Rawlsian idea of the common good. What the contributors of this book do is just that: put the pieces of this mosaic under their microscope, observing and analyzing them in detail and, at times, turning them upside down.

Therefore, in this book, the goal is not to focus on the Rawlsian defnition of the common good as such, nor to defnitively judge whether it is feasible or not. The belief is that an approach of this kind would lead to an overall image that is always lacking in some parts, due to the multifaceted nature of this notion. The approach is rather to concentrate on a multiplicity of concepts, all intimately linked to the category of the common good, in the hope that from this multiplicity the reader will be able to extrapolate its uniqueness, that is, what unites these elements and allows them to ensure the substance and multiform vitality that are essential if the concept of the common good wants to make its contribution within the community it addresses.

In Chapter 1, Daniel A. Dombrowski devotes himself to the analysis of the concept of community in Rawlsian theory. To be exact, the chapter contains a defense of Rawlsian, political communitarianism, which is seen as a moderate stance between the weak communitarianism found in Hobbes and related thinkers, and the strong communitarianism found in Aristotle and the many thinkers infuenced by him. Thus, the characteristics of the Rawlsian political community are highlighted, wherein there is widespread acceptance by the population of a certain conception of justice (contra Hobbesian views), but where there is not widespread acceptance of any view of the good or of any particular comprehensive doctrine (contra Aristotelian views).

In Chapter 2 on faith and the common good, David A. Reidy sets out the “fdeism” to which Rawls claims to have been committed throughout his adult life. Taking into account the important diferences between A Theory of Justice, Political Liberalism, and The Law of Peoples, the author shows how this fdeism relates in each case to the common good at which Rawls believed free equals properly aimed in political and

law-making activity, suggesting that in his philosophical work Rawls was, among other things, “turning inside out” his fdeism.

In Chapter 3, Marco Martino deals with fraternity. In A Theory of Justice, Rawls associates his diference principle with the concept of fraternity, drawing attention to the revolutionary tripartite motto of 1789, “liberty, equality, fraternity.” Through the diference principle, Rawls attempts to think rationally about fraternity, seeing it as something intrinsic to political processes, rather than external to them. Martino traces the evolution of this reasoning: in his investigation, the crucial features of the ‘indirect’ treatment of the principle of fraternity developed by Rawls are brought to light, even if ultimately it is concluded that the philosopher does not provide fraternity with an adequate theoretical foundation.

In Chapter 4, Ruth Abbey examines what Rawls says in A Theory of Justice about friendship as an interpersonal relationship. In particular, she underlines the key points in TJ in which friendship plays a crucial role: as one of society’s smaller associations or social unions, as a human good, and – to be exact – as the clearest of Rawls’s examples of a complementary good, as a central aspect in the morality of association stage of moral development, and in his discussion of guilt and shame. Furthermore, Abbey shows that a focus on friendship brings some important Aristotelian features of the philosopher’s thinking to light.

In Chapter 5, Elizabeth Edenberg deals with the question of whether Rawls’s theory of justice is capable of secure justice for women and how this relates to the common good. In particular, Edenberg points out how many injustices rooted in the gender structure of society were justifed by appealing to the common good. Yet to properly account for how a just society can meet the needs of the common good, surely the common good should be good for all members of that society, rather than relying on subordinating some to allow for the fourishing of others. Edenberg underlines how by Rawls’s own measures of justice that rely on the acceptability of principles of justice to people understood as free and equal, a sexist society or any society that seeks the common good through the exploitation or subordination of some groups to others would not pass Rawls’s own hypothetical acceptability test. Nevertheless, Rawls’s own discussion of gender justice has been the subject of extensive feminist critique: both Rawls’s discussions of gender justice and the critical responses to them are the subject of the chapter.

In Chapter 6, Paul Voice goes through the analysis of the concept of love in Rawlsian theory. Since Rawls wants to leave room for citizens to love for reasons and in ways that align with their idea of the good, Voice outlines that love relationships are only partially constrained by the philosopher’s two principles of justice. From this observation, the author argues that the partial constraints on love, which Rawls’s theory of justice imposes, are insufcient, resulting in systematic injustices that ought to be corrected. However, Voice also claims that love and justice

John Rawls and the Common Good 11 can be aligned and reconciled both with Rawls’s principles of justice and with his own notion of love. To this end, the author advances a notion of proper or just love.

In Chapter 7, M. Victoria Costa examines the role of the political liberties in Rawls’s theory of justice and discusses how they ought to be distributed to promote justice and the common good. Her chapter acknowledges that one way to defend the equal distribution of the political liberties appeals to their contribution to self-respect. But, since Rawls holds that the fair value of the political liberties ought to be guaranteed, as well as the equal distribution thereof, Costa argues that it is a concern with preventing political domination that best explains the measures required to guarantee their fair value. The twin requirements of equal distribution and fair value are seen to contribute to the common good by operating at the institutional level. But these requirements, Costa highlights, can be supplemented by a principle: the principle of the common good, guiding the ways in which citizens interact with each other when they make use of their political liberties.

In Chapter 8, Paul Weithman deals with the concepts of “reciprocity” and “justifcation” in Political Liberalism. Liberalism requires that political arrangements be justifable to those who are subject to them. Some critics argue that any view committed to this Justifability Condition is caught in a dilemma, which arises when we ask whether the condition applies to itself. The author argues that Rawlsian political liberalism avoids the dilemma that self-application is thought to imply. The aim of Rawlsian political liberalism is to identify principles citizens have to honor to relate to one another as free equals. Weithman’s answer shows that Rawlsian political liberalism is the most defensible form of liberalism because of its commitment to a form of reciprocity that is needed for our politics.

In Chapter 9, Boettcher focuses his analysis on the concept of respect, in reference to the Rawlsian idea of public reason. According to the latter, government ofcials and even ordinary citizens should decide fundamental matters of law and policy on the basis of reasons that are in principle acceptable to others in light of some reasonable political conception of justice along with other publicly accessible standards of evaluation. One requirement of public reason is restraint, that is, the willingness to refrain from supporting such laws and policies solely on the basis of nonpublic reason. Boettcher revisits Rawls’s remarks on respect and self-respect and argues that the restraint requirement is based primarily on an underlying duty of mutual respect. However, the author outlines how an ideal of civic friendship plays an important complementary but secondary role in grounding the main requirements of public reason.

In Chapter 10, Jon Mandle describes two basic roles played by the idea of a sense of justice in Rawls’s theory. On the one hand, he examines Rawls’s characterization of justice as fairness itself as an attempt to

describe our sense of justice in refective equilibrium. On the other hand, Mandle analyzes TJ’s account of the psychological development of a sense of justice in individuals, which is part of Rawls’s argument for the stability of a well-ordered society – the other component being his argument for the congruence of the right and the good. Mandle highlights that understanding how the moral psychology described by Rawls sets the stage for the congruence argument helps to clarify the nature of refective equilibrium and the Rawlsian vision of moral justifcation.

Chapter 11 analyzes the role of cooperative virtues in Rawlsian thought and, in particular, ofers a reading of the twofold value they have within his framework: they are seen to have an intrinsic value in the life of his citizens and, at the same time, an instrumental one from the point of view of society. The intrinsic value of cooperative virtues concerns the fact that, without their acquisition, the individual does not become a moral person, that is, a fully cooperative member of society. However, cooperative virtues also play an essential role from an instrumental point of view: their presence in citizens constitutes in fact the condicio sine qua non for a well-ordered society to be able to frst establish itself and then remain stable over time.

Notes

1. This accusation has been accompanied by the criticism against the preponderant role assigned by Rawlsian theory to procedural aspects in the attempt to maintain a position of neutrality toward the diferent worldviews competing on the social stage. Liberalism has thus been accused of indiference toward the multiple conceptions aimed at the fourishing of the human being, the so-called privatization of good (MacIntyre 1990). It is important to underline that the communitarian criticisms have especially turned to the early works of Rawls, pertaining to the period of his philosophical theorizing before the publication of Political Liberalism (1993). At the same time, it is also useful to mention that, with the ascription as “communitarian,” some notable philosophers of this group such as Michael Walzer, Alasdair MacIntyre, and Michael Sandel have not always been ‘satisfed.’

2. The book does not analyze the communitarian objections in detail, nor does it aspire to examine whether they are well founded or not. On this topic, see Buchanan (1989), Gutmann (1985), and Mulhall and Swift (2003).

References

Buchanan, A. 1989. “Assessing the Communitarian Critique of Liberalism.” Ethics 99(4): 852–882.

Campanini, G. 2014. Bene comune. Declino e riscoperta di un concetto. Bologna: EDB.

Downing, L. and R. Thigpen. 1993. “Virtue and the Common Good in Liberal Theory.” The Journal of Politics 55(4): 1046–1059.

Dworkin, R. 1995. “Foundations of Liberal Equality.” In S.L. Darwall (ed), Equal Freedom. Selected Tanner Lectures on Human Values, 190–306. Ann Arbor: Michigan University Press.

Galston, W. 1991. Liberal Purposes: Goods, Virtues and Diversity in the Liberal State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gutmann, A. 1985. “Communitarian Critics of Liberalism.” Philosophy & Public Afairs 14(3): 308–322.

Hollenbach, D. 2004. The Common Good and Christian Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hussain, W. 2018. “The Common Good.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. At https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/common-good/ (accessed Mai 2021).

Keys, M. 2006. Aquinas, Aristotle, and the Promise of the Common Good. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Larmore, C. 1996. The Morals of Modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

MacIntyre, A. 1990. “The Privatization of Good: An Inaugural Lecture.” The Review of Politics 52(3): 344–361.

McCabe, D. 1998. “Private Lives and Public Virtues: The Idea of a Liberal Community.” Canadian Journal of Philosophy 28(4): 557–585.

Mulhall, S. and A. Swift. 2003. Liberals and Communitarians. Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

Nozick, R. 1974. Anarchy State and Utopia. New York: Basic Books.

Rawls, J. 1988. “The Priority of Right and Ideas of the Good.” Philosophy & Public Afairs 17(4): 251–276.

Rawls, J. (1971) 1999a. A Theory of Justice (TJ). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, J. 1999b. Collected Papers (CP), ed. S. Freeman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schwarzenbach, S.A. 2009. On Civic Friendship. Including Women in the State. New York: Columbia University Press.

Sluga, H. 2014. Politics and the Search for the Common Good. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

1 Community

Daniel A. Dombrowski

Introduction

Perhaps the safest characterization of John Rawls’s view of community (or social union) is that his stance is a moderate one between two extremes. At one extreme is a weak sense of community found in Hobbesian stances wherein there is a modus vivendi established between contesting parties that do not share a sense of justice. This is merely an expedient truce that is meant to halt hostilities among the contesting parties, hence it is an inadequate basis for stability over time in that if one of the contesting parties got the upper hand, the truce could be broken and the party with the greatest threat advantage could, in efect, ram its views down the throats of everyone else. At the other extreme are Aristotelian stances that prescribe a unity constituted by widespread acceptance of a particular conception of the good life or of what Rawls calls a comprehensive doctrine. These views can be called weak and strong communitarianism, respectively (see Nickel 1990).

The moderate stance found in Rawls is that of a political community wherein there is widespread acceptance by the population of a certain conception of justice (contra Hobbesian views), but where there is not widespread acceptance of any particular view of the good or of any particular comprehensive doctrine (contra Aristotelian views). This political community in PL comes about through an overlapping consensus regarding justice among people who afrm (very often uncompromisingly) diferent conceptions of the good. This means that Rawlsian political community may very well be afrmed by people for somewhat diferent reasons. But Rawlsian community is indeed afrmed for moral reasons in contrast to the reasons of expediency that characterize Hobbesian views. One consequence of this Rawlsian view is that Aristotelian or strong communitarianism (often in popular discourse referred to simply as communitarianism), which has a state-endorsed conception of the good life, should be abandoned in a condition of pervasive pluralism regarding the comprehensive doctrines that citizens afrm. Comprehensive doctrines apply to many topics other than political justice. Rawls is happy to afrm

a consensus regarding the latter only, given the wide array of comprehensive doctrines: utilitarianism, various types of perfectionism, various (and sometimes contentious) religious conceptions of the good, Marxism, hedonism, etc. The hope is that we could attain a political community that could accommodate diversity by removing many difcult philosophical/ religious issues from the political agenda.

The task of political philosophy in such a community is to analyze and give a coherent linguistic formulation to popular culture in constitutional democracy. In periods of turmoil political philosophy may be highlighted more than when there is a stable concept of justice at work in political institutions and in popular culture, when the work of politicians, journalists, and others comes to the fore. One is reminded here of Thomas Kuhn’s famous distinction between revolutionary and normal science (see Kuhn 1970). The important thing is that toleration on the ground be widespread and a matter of intuitive conviction on the part of citizens, given the fact of pervasive pluralism. That is, one need not have general agreement about the good life in order to have political community and agreement about justice.

The thesis of the present chapter is that the aforementioned moderate Rawlsian view of community is worthy of explication and defense. This explication and defense will occur over several stages in that I will frst deal with the topic of individuation through community in Rawls and then move to the complementarity among citizens that characterizes a just society. The communal virtues in Rawls will be considered along with the importance of the diference principle for the concept of community. Contemporary critics like David Hollenbach, Louis Dupre, and Michael Walzer will be considered, as well as historical thinkers who are often assumed to ofer resistance to Rawlsian views, like Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas. We will see that justice as fairness is by no means opposed to the importance of community in Rawls; nor is the concept of goodness. The chapter ends with a consideration of the relationship between communal love/benevolence and Rawlsian justice.

I. Individuation Through Community

There is a communitarian strand to Rawls’s theory of justice due to the fact that the very constitution of the individuals who are sometimes pitted against the concept of community requires cooperation and a sense of mutuality and reciprocity. Members of the Rawlsian community as a result must share in the distribution of benefts as stipulated in his famous two (actually, three) principles of justice. Far from endorsing the “unencumbered self” so often ascribed to his theory (especially by Michael Sandel), Rawls emphasizes the individual’s membership in a family and various associations that form the individual’s character, for good or for ill. It comes as a surprise to some readers that Rawls thinks of the social

Daniel A. Dombrowski

basis of self-respect as the most important primary good. A person’s endeavors need to be at least implicitly appreciated by others in a shared community of interests in order to confrm such self-respect. Self-respect involves not merely (and not primarily) one’s own norms, but also (and primarily) the norms that are anchored in familial or communal bodies (see Alejandro 1993).

It is a mistake to depict the famous liberalism-communitarianism debate as a confict between an individual’s judgment and society. This is because the ends an individual chooses are already intertwined with others’ approval. Perhaps an Emersonian self would be willing to stand up for its moral independence regardless of what a community of shared interests might think, but this is not the Rawlsian view (see Emerson 1885). It is true that Rawls defends vigorously political autonomy, but not a comprehensive autonomy that is destructive of associative ties. A community of shared interests provides standards of worthiness that are crucial to the primary good of self-esteem. It is membership in a community of shared interests that fosters self-esteem, not the other way around (Alejandro 1993, 81). That is, the issue of whether the self is prior to its ends or vice versa involves a blurred distinction. A developed sense of justice requires the presence of (familial and associative) others (TJ, 462–479). In this regard we should not exaggerate the alleged diference between supposed Rawlsian (“Western”) individualism and the communitarian self that is found, say, in various African cultures (see Nnodim 2020).

Before individuals choose the sort of persons they want to be, they have already been shaped by communal values. In this regard even the Rawls of TJ had anticipated Sandel’s critique. We are historical individuals who are parts of some social tradition such that only in social union is an individual complete (TJ, 525). Community is not a mere attribute of an individual but is partially constitutive of the process of individuation. If the social basis of self-respect is secured, it is more likely that citizens will engage in genuine mutuality and be willing to reciprocate with others in a system of mutual beneft. In turn, such willingness makes it more likely that society can be organized in such a way that the demands of the two (really three) principles of justice will actually be met.

Given what has been said thus far, a sketch of Rawlsian responses to strong communitarian critiques can be seen. Sandel seems to miss altogether Rawls’s moderate communitarianism largely because it is not the strong sort that Sandel himself defends (see Sandel 1998). That is, Sandel assumes a defnition of “community” that is too restrictive. Alasdair MacIntyre worries that without strong communitarianism Rawlsian justice cannot be sustained, in which case there is not much hope for contemporary democracies, given the fact that there are competing concepts of the good and comprehensive doctrines that citizens afrm, but democracies do thrive in the contemporary world, even when threatened by autocrats like Donald Trump. This continued success of liberal democracy should

call into question the assumption that strong communitarianism is a necessary condition for democracy to fourish (see MacIntyre 1984). And Charles Taylor contends that liberalism itself is a conception of the good, thus implying that Rawlsian justice itself is a comprehensive doctrine (see Weinstock 2015; Taylor 1989). But the qualities stipulated of the parties in the Rawlsian original position are not intended as clues regarding a comprehensive view of human nature any more than the need for political autonomy is an implicit way of sneaking in comprehensive autonomy. Rawls is doing something very specifc in his political philosophy and is not trying to replace the wider aims of comprehensive doctrines, which are tolerated in a condition of reasonable pluralism.

II. Complementarity

Thus far I have tried to call attention to two points (in reverse order): (a) a citizen’s sense of justice and concept of the good presuppose habituation into some communal values at the familial and associational levels and (b) due to the pervasive pluralism of concepts of the good and comprehensive doctrines in contemporary societies, strong communitarianism can hold sway at the societal level only through the illegitimate use of force. Nonetheless there can be a political community based on a common view of justice, rather than a common view of the good. Rawlsian communitarian justice can more accurately be described as a (just) social union of (particular communal) social unions (TJ, 527, 529; PL, 201, 304, 323). Any social union, including that found in the original position, involves complementarity, which Rawls analogizes to the musical players in a symphony orchestra (TJ, 524; PL, 321). Each player could have learned to play well every instrument in the orchestra, but each becomes profcient on a single instrument due to the difculty involved in learning them all. The word “symphony” itself literally means to sound together, to harmonize together, despite individual diferences among the players. The orchestra metaphor evokes the democratic harmonic resolution of any tension between individual and society. Behind the veil of ignorance, as it were, each participant could theoretically play any instrument, but in reality each has to rely on the other players to complement individual insufciencies. When the veil – on this metaphor, a curtain – lifts, we can play together in an aesthetically pleasing way (see Love 2003).

As is well known, over time Rawls became somewhat dissatisfed with the shape his theory of justice had originally taken. The principles of justice in TJ were seen as parts of an overarching moral theory. A society based on them would be stable because all reasonable and rational people would agree with them. Rawls came to see that a better concept of stability was needed, which led in PL to the idea of overlapping consensus. We have seen that this idea operates even in a condition of pluralism with respect to comprehensive doctrines yet nonetheless provides a

18 Daniel A. Dombrowski

greater sense of community than the weak sort found in a modus vivendi. Overlapping consensus is admittedly not deep, but this is a commendable feature in that overlapping consensus is, as a result of its not being deep but wide, conducive to widespread agreement regarding justice in a democratic society.

Establishing terms for social cooperation for mutual beneft remains Rawls’s primary concern, but the principles of justice are now seen more accurately in PL as political, rather than as comprehensive. These principles function as modules that can be inserted into various comprehensive doctrines with their deeper communal ties. Even if citizens disagree strenuously regarding some particular issue or piece of legislation, they may nonetheless be committed members to political community in that the community in question centers on the basic framework of a just society and on institutional essentials, rather than on various concrete particulars. Stability for the right reasons requires that commitment to this framework not be a mere compromise, but a matter of principled conviction so as to secure political community and the complementarity involved in such community (see Martin 2015; Riker 2015).

III. Communal Virtues

In addition to the criticism of Rawls not being sufciently committed to community, it is also common to hear that he did not pay sufcient attention to the virtues. However, it is important to note the distinction between two sorts of virtues: political virtues and those linked to the relatively non-political lives of citizens with their separate comprehensive doctrines. Rawls is especially interested in the political virtues: toleration of reasonable diferences, civility, a sense of fairness, and reasonableness itself. Further, as we have seen, Rawls notes the importance of the virtues connected with the socialization process of citizens in families and associations (including neighborhoods and sports teams and churches). That is, socialization into a virtuous life of some sort may be needed in order to eventually have mature citizens capable of the political virtues. But a just society cannot expect all citizens to develop those virtues that are idiosyncratic to some comprehensive doctrines but not others, as in theological virtues found in some religions but not others and certainly not in the lives of religious skeptics. Faith is a prime example here. In diferent terms, the common good of common goods that characterizes a just society requires the political virtues that are essential parts of the societal common good, in general, but only permits those found in the more specifc common goods at the associational level of difering comprehensive doctrines (see Downing and Thigpen 1993; Macedo 1990).

In a limited sense, liberal neutrality extends to both communities and virtues, although a just state is not neutral regarding the need for political virtues nor regarding the need to develop cooperative virtues

Community 19 within familial and associational life, a development that, like capital, can accumulate over time (PL, 157). One thinks here of the way that both churches and youth sport teams inculcate the virtues of respect for others, sportspersonship, and team cooperation. It would be a gross error to think that Rawls privatizes virtue in that “the personal” is by no means synonymous with “the private,” as we will see. Indeed, well-ordered societies depend on the existence of citizens who have developed the communal virtues, both the cooperative virtues developed within the context of one’s familial/associational life as well as the political virtues per se (see Costa 2004; Galston 1991).

IV. The Diference Principle

Rawlsian political community consists in a social union of social unions. This idea, when tethered to the famous diference principle, gives rise to questions regarding how the Rawlsian view will bring about and/or sustain community when principles of justice are, in turn, tethered to some economic system or other. A social union of social unions is meant to defect the charge that Rawls cannot account for the value of community, but Rawls is acutely aware of the fact that our communal or social nature can be easily trivialized (TJ, 456–459). After all, even egoists cannot learn to speak or even to develop their own egoistic concerns outside of specifc communities. Genuine human sociability, on Rawls’s view, requires the diference principle rather than the “privatized” society that fnds its natural habitat in theories that are enthusiastic about competitive markets. Rawls, by contrast, argues for a complementary good for all. He ofers various mechanisms meant to hold in check instrumental market relations that get in the way of political community, especially the diference principle and the public funding of elections so as to combat the curse of money (TJ, 226, 275, 302; PL, lviii–lvix, 235, 328, 357–360; PRR, 772–773; LP, 24, 50, 115; also Schwarzenbach 2015).

However, we will see that Rawls thinks that the primary question regarding the nature of a just society requires further specifcation regarding what sort of economic system could bring this about. Here I would like to emphasize the fact that, although Rawls provides only limited support for meritocratic notions (a feature of Rawls’s view that is overemphasized by Sandel), he does not ofer a blanket repudiation of them. In fact, the general ideas of merit and desert are so central to our judgments and practices that their complete elimination would put everything else we believe in ethics into disequilibrium. The question is not, “do people sometimes deserve diferential treatment based on diferences in character or performance?” (of course, they do!), but rather, “do people deserve unequal income or power based solely or primarily on these?” (from a Rawlsian point of view, they do not). That is, informal practices of praise and blame can easily be brought into equilibrium with Rawlsian

Daniel A. Dombrowski

political community. Citizens in a just society are motivated to participate in political and economic systems that are consistently aimed at providing everyone with the means to exercise and develop their capacities of selfdetermination. We want to make sure, however, that goods that might be idealized at the high end do not generate conditions in which many people cannot secure more modest goods that are essential for such fourishing (see Doppelt 1988; also Dombrowski 2011, chapter 4; Dombrowski 2001, 2019).

V. Hollenbach’s Criticisms

The purpose of the present chapter is to explore the concept of community or, to use a roughly synonymous designation, the common good in Rawls’s thought. It will no doubt be objected that political liberalism is basically a political philosophy meant to justify toleration, but toleration is not enough. Critics might wonder where the Rawlsian notion of community or the common good is to be found. These critics might not be willing to buy into political liberalism without a clear indication of how this view is conducive to community or the common good. David Hollenbach provides a prominent example of this sort of skepticism regarding Rawls’s thought. To achieve a polis, it will be alleged, one needs to do more than show toleration and a live-and-let-live attitude that avoids introducing concepts of the full human good into political discourse. Rawls’s method of avoidance is part of a commendable hope to neutralize potential conficts, according to Hollenbach, but the result of this method is seen to be disastrous:

A principled commitment to avoiding sustained discourse about the common good can produce a downward spiral in which shared meaning, understanding, and community become even harder to achieve in practice. Or, more ominously, when the pluralism of diverse groups veers toward a state of group confict with racial or class or religious dimensions, pure tolerance can become a strategy like that of an ostrich with its head in the sand. In my view, this is just what we do not need.

(Hollenbach 1998, 8)

What we need, according to Hollenbach, is the realization that a human being is, as Aristotle suggested, a political animal ( zoon politikon ), although Hollenbach does not seem to notice that Rawls also in a way agrees with this claim.

Hollenbach assumes that political liberalism violates the communitarian nature of religious and other groups by placing us in an “individualistic isolation” that “is fnally a prison.” The question seems to be, from the perspective of political liberalism, whether the call received by, say,

religious communities (which in itself is perfectly compatible with liberal justice) means that the whole body politic is being called. Another question is whether the reasonableness required to participate in the original position, and the resulting principles of justice, can plausibly be described as leading to “individualistic isolation.” Nonetheless common ground between Hollenbach and political liberalism can be established when Hollenbach rightly emphasizes that justice is the premier social virtue and that democratization on the world stage is required in order to promote international justice. This commendable language makes overlapping consensus easier both nationally and internationally than it would be otherwise.

We have seen that two sorts of community or common good or solidarity should be distinguished: (a) the common good as established through some singular comprehensive religious (or philosophical) doctrine and (b) the common good as established through a pervasive willingness to abide by fair terms of agreement among people with diferent comprehensive religious (or philosophical) doctrines. The latter is a type of community or solidarity – indeed a type of love, according to Rawls, or a type of metacommunity – largely ignored by Hollenbach. He is more fascinated by an “intellectual solidarity” among Catholic intellectuals that provides a model for what can be hoped for in society as a whole. However, as I see things, intellectual community even among Catholic intellectuals is a longshot, much less solidarity among intellectuals in general. To be fair to Hollenbach, we should notice that the discourse across boundaries found in the history of Christianity – early Palestinian Christians interacting with the Hellenistic and Roman worlds, Augustine in dialogue with Stoic and Neoplatonic thought, Thomas Aquinas appropriating ideas from pagan and Jewish and Muslim sources – has, in fact, occurred and illustrates in microcosm the sort of community and solidarity that he hopes for in the macrocosm.

Hollenbach sees a shift in Rawls from the Kantian character of TJ to the pragmatist character of PL, where, he alleges, the original position has been largely replaced by the historical presuppositions of Western constitutional democracy. Hollenbach is on thin ice here for two reasons. First, Rawls explicitly retains the original position in PL and LP; and second, the presuppositions of Western constitutional democracy were not absent in TJ (see, e.g., PL, 50, 54, 116, 304–310; TJ, 195, 222, 226, 243, 295, 354–357, 360, 363, 382–386, 492). There is some legitimacy in Hollenbach’s point here, however, when it is noticed that the theory of justice in PL is not intended as an argumentative coup de grace directed at those who do not already share the propositions of Western constitutional democracy (see Hollenbach 1994a, 133–134).

Rawls is not claiming, as Hollenbach alleges, that presuppositions about the common or ultimate good are “private” because the ideals of churches and other communal associations are certainly “public” at least within the church or association and perhaps are public in a more general