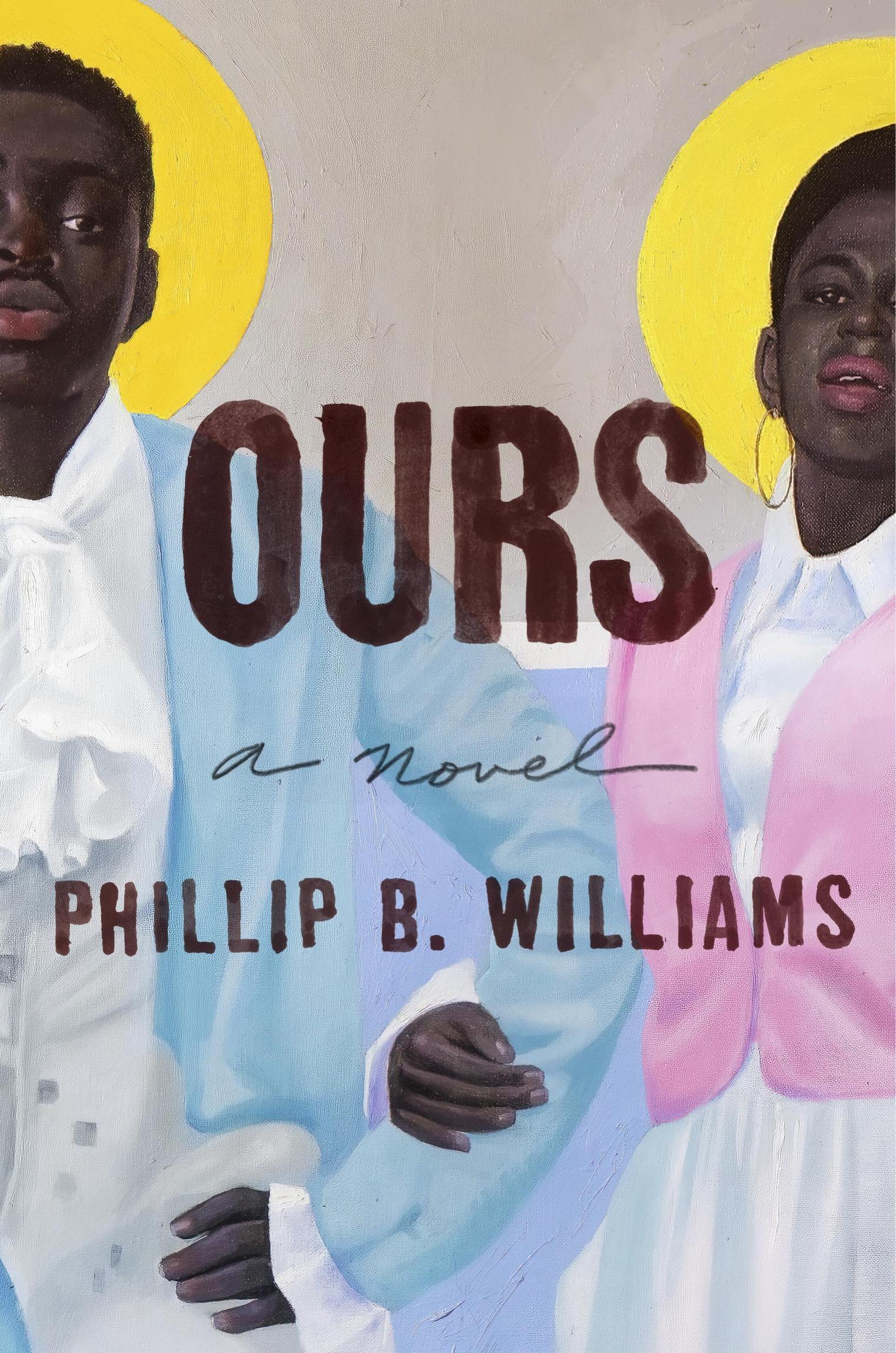

Go Down, Moses

[1]

Ours was founded by a single incident. Several white families established themselves in what was then called Graysville. The entire town relied on Graysville-Flint Bank, headed by a Mr. George Flint, who had already made hundreds of thousands of dollars in real estate somewhere in Maine, as rumors had it. He founded Graysville on a whim. With a sudden need for adventure, he packed up all he owned and sent for the rest once he made it across the Mississippi River and found himself in St. Louis, Missouri.

Banking there became a hassle; already-established branches offered little to no room for a new executive and showed no interest in his cutthroat procedure of lending to those most in need who also carried the smallest possibility of paying anything back, taking from them their very bed if debts weren’t paid on time.

Word of his arrival preceded him with the force of a plague and the entire banking community refused to have anything to do with him. With no other choice, Mr. Flint headed just a few miles north of St. Louis, discovering a nothing place burdened by woods and orioles. He used his fortune to tear down every piece of nature that challenged his financial vision. He bought up the land and divided it into plots he sold to anyone able to pay between $130 and $200.

Word got around in 1832 that a new development had started just north of St. Louis with cheap prices for large plots of land. Mr. Flint made a name for himself and his business, calling it the Oriole Street Realty Corporation. Between 1833 and 1834, more than 120 people moved into Graysville, bringing with them over three dozen businesses.

In the summer of 1834, a dark-skinned woman and man appeared on the outskirts of town. They were watched from the moment they arrived to the moment they reached the newly built branch of the Graysville-Flint Bank. It hadn’t been open for a full two years before the two opened the door and the woman asked to speak with “the superior of this bank.” Everyone working stared at her, one man so anxious he sweated the pen from behind his ear till it slid to the floor, the clink across the wood making him jump. She cleared her throat and repeated her request. Someone stood and ran to the back.

Moments later, Mr. Flint approached, a gun in his holster. People ducked beneath desks. Some of his bankers left the establishment to wait for shots to go off and for two bodies to be dragged out. He glared at the woman and then spoke to the towering, broad man who came with her.

“Your business here?” Mr. Flint said.

“I caught word that you have a few plots of land left for purchasing. I’m looking to buy one. Build myself a home,” the woman said. The man who accompanied her stood a couple of feet off to the side and behind her, meaning Mr. Flint had to turn around to see the woman he had briskly passed.

He didn’t like the height difference between the woman and man, she of average height but her head top reaching just under his chin. Mr. Flint stood about three inches shorter than the man, and the man’s silence paired with his daunting size and intense stare toward nothing felt deliberately hostile.

“Is this man your husband?” Mr. Flint said. “If so, he should have told you that we do not sell to coloreds here. It is illegal. There is a sign out front. If he is not your husband, then he should have told you anyway. Much time would have been saved for the both of us if you two would have”—he paused—“could have read the sign.”

“But, sir, I have money for—”

“It is impossible,” he said, and headed back to his office. “Please, let yourselves out.”

“Even with this?” The woman reached into a large mismatch pocket sewn into her dress and pulled out $1,500 in cash tied in a tight bundle with sprigs of jasmine. Mr. Flint laughed uncontrollably, and seemingly out of his mind with humor, he smiled broad as a dog’s mouth. With a “Follow me” he led her into his office.

It was true that selling to her as a realtor carried legal repercussions, but with the amount of money she carried, Mr. Flint couldn’t let her leave unattended. He was jovial, almost feeling accountable to find room for this woman and her silent companion. He decided that she would purchase her plot from an independent seller, someone who would purchase the land in their own name and legally sell it to her without any ties to a realtor. Mr. Flint said the land cost more because it came with a house already built, though that was untrue. She agreed to the price of $1,500 for 2,500 square feet and moved in right away. In less than three months the entire town evacuated, the white residents moving south to St. Louis or, in much smaller numbers, north to Delacroix. The fleeing white residents sold their properties, houses and furniture included, to Negroes for triple the price they had purchased them. They gave a third of the profits to Mr. Flint and used the rest of their earnings elsewhere. Graysville became Ours and its new citizens were thereafter called the Ouhmey.

After the woman and man arrived and settled, more and more Negroes from all over the south came to Ours led by hearsay, both freedmen and soon-to-be freedmen, around forty in total. Many found themselves running away from undesirable pasts, including slave work that had killed everyone they loved and surely would kill them next.

Negroes occupied the houses abandoned by their once-ago residents. Mr. Flint, though no longer a part of the community, visited from time to time to mark which houses had new occupants. He took copious notes of faces and names, the day they said they arrived, and where they came from. Once a week he visited Ours to collect money owed. Those who had moved

in during his absence were told to buy the house immediately for $250 or pay Mr. Flint $35 a week for two months straight. Whoever couldn’t pay him what he requested within a month’s time were to be forced from the houses at gunpoint by St. Louis officers, but of course this never happened.

Mr. Flint died of a stroke one month after Ours had been named. No one bothered charging them anything thereafter, not even the government that took over all property in Mr. Flint’s name, as he had no children and left no will. Mysteriously, no evidence existed that either Graysville or Ours was ever affiliated with Mr. Flint. Allegedly, the room he died in smelled like jasmine for months after they removed his body.

[2]

The woman who pioneered the migration called herself Eleanor to Mr. Flint, no surname, and this not her actual name at all. To the nolonger-slaves she called herself Saint. The man that traveled with her was nameless and speechless.

When they reached town, Saint told those who followed her, “Wait somewhere in the wilderness until you hear word from me that you can come. When you come, bring the amount of money I gave you before we left. Keep yourselves covered in jasmine. Keep it in your pockets and rub it on your skin. We gambling here and need all the luck we can get.”

The newly freed had traveled with her from plantations all around Arkansas, plantations that she single-handedly ruined without any bloodshed but plenty of death, so most of them trusted her without question after having seen her power to liberate them.

It began on the Ross plantation in Hinton, Arkansas. One night, Saint seemed to appear out of their combined suffering taking shape in the form of a woman dressed just like they were. In one of the slave quarters, she whispered something that made everyone wake up at the same time. They all thought she was a spirit. Some hid their faces from her while others sat

in awe and listened: “In three days, your self-proclaimed master will be dead, and you will follow me to freedom.” Then she walked out the door, reappearing at each place the enslaved slept.

The second night at the plantation, Saint and her companion tore down white fists of cotton and destroyed a garden reserved for the so-called master and his family. They trampled a pattern into the land that if seen from above resembled a pitchfork. Sunrise, and the mistress of the house broke into a violent fever. Every doctor that visited, three in nine hours, failed to relieve her, and everything they tried seemed to worsen her illness. It wasn’t until the mistress threatened to kill herself and everyone in the house if one more doctor tended to her that the requests for doctors ceased.

On the third night, Saint carved symbols into flat stones. When she finished carving, her companion took the stones to four different locations around the plantation and hid them beneath bushes. That following morning, the so-called master discovered every crop had withered overnight or sat soft and blackened on the ground.

Ross, the so-called master, took his rifle and, out of anger, shot at the nearest black face he saw. When he missed, his angry expression became mournful. Defeated, he grumbled as he returned to his sick wife.

On the fourth and final night, Saint and her companion rotated the location of each stone clockwise so that the southern stone became the western stone, the western the north, and so forth. That morning Ross, the so-called master, and his wife died in their sleep, both discovered in their bedroom by Ren, an enslaved cook, when neither showed up for breakfast. The three overseers were all dead, too, mouth-gaped and blank-staring at the ceiling of their cabin. Slobber slid down the sides of their cheeks like translucent worms.

Ren stumbled backward as though resisting the inward pull of the open mouths before her. She deserted the stiff corpses, running to her quarters to share the news with thirty-one enslaved Africans suddenly without a master. However, whatever joy Ren expected to feel crumbled before her because the so-called master’s son and the son’s wife appeared up the lane, their surrey growing larger over the horizon.

Saint stood on the steps of the house and watched the couple approach, led by two horses guided by a young Negro man. The so-called master’s son, enraged to see her standing on the steps of the mansion, wearing his mother’s emerald dress that he had purchased for her only months ago, rushed out of the surrey, and dropped dead the moment his feet touched ground. Panicked to see her husband fall and not get up, the wife demanded the Negro driver to help her get out of the surrey.

“Paton, open this door this instant, since you do not have sense enough to assist your master.” Paton opened the door and the woman slapped him hard, then reached for Paton’s hand. Her gloved hand in his, she stepped onto the ground and dropped dead. Paton leaned down to see her more closely.

“You touch them, and you die,” Saint said without anger. Her stolen elegant dress swiped the steps behind her like a receding wave as she made her way toward Paton. What a beautiful day: clouds, puffed up like bloated bodies, slipped between the old trees—the sight made Saint tear up, all that amorphous white, midair and aimless. When she got close enough, she touched Paton’s face with a gentleness he had never felt before and said, “This way.” She turned and walked to the field, speaking to Paton as he followed her. “Don’t ever try to touch your chains again. You might get rust on your priceless skin.”

She did this on five more plantations, emptying the houses of anything valuable she found, including money and food, clothes and tools, books and legal documents, animals, ledgers, and deeds. They took everything except the receipts of payment for the purchased slaves. Those were burned immediately, unfortunate only because they documented what may have been correct birthdays for the soon-to-be-freed, many of whom wanted to know if they were lied to about their births, forced to believe in whatever myth about themselves they were given. Saint knew, however, that those dates were mostly false and the new selves the just-freed obtained through fire was a new birth.

She gathered herself a parade of ex-slaves and guided them north to Missouri. That they were never caught by or even saw a living thing—not

even a bird—throughout their entire journey proved to them that Saint was their savior, though some never fully trusted her and considered her with suspicion because they feared both her and the man who said nothing and always smelled like the earth.

[3]

One early morning in Ours, just days after Mr. Flint died, Saint left her house, wearing a large blue dress with a train of several feet. She held a wood staff carved to bear a nest of thirteen serpent mouths at the top, their heads all facing the sky, the length of the staff made of the outstretched bodies of each serpent. She descended the steps of her home at the west end of Tanager Street, and everyone stopped and smiled at her. She hid her hair beneath a hat of fabric wrapped such that it made a ring of cloth on top of her head like a fat halo of dough, not a strand of hair poking out. Her companion walked by her side, staring ahead, his hair cropped low and face hairless. He wore black trousers and a black vest with a white shirt underneath. His black shoes were shined, as glossy as his eyes that floated in the bony cradles of their sockets.

Saint told everyone to come to Creek’s Bridge at sunset and to bring whatever meal they can to share. “Everything you can spare and even what you can’t,” she said. The musicians were to bring their instruments. She told everyone to dress in something to dance in. As soon as she finished speaking, wild strawberry pies went into the oven and someone started roasting a pig, boiling turnip and collard greens, enough to feed the entire town. The children searched for clothes to wear and waved garments over their laughter like flags.

When time came to head over to Creek’s Bridge, they went straight to the water. Lanterns hanging on pikes arranged in a circle, a large bonfire in the center, made it bright enough that they saw everything in front of and all

around them. Food furnished a few tables farther from the creek and the fiddlers began to play.

Saint had changed into a small white dress with a large yellow ribbon wrapped around and knotted at the back. She wore no shoes and encouraged everyone to take off their own. She went to the bonfire and started clapping. Soon everyone clapped with her in unison clap clap clap and she began to dance, to twirl, and laugh. The children joined her first, then the women, hopping up and down and spinning about. The summer night had not cooled much since daytime, but they moved in the heat, the fire yanking sweat from their bodies, their naked feet sliding on the grass, their arms spinning above their heads. They touched their faces, put their fingers in their mouths, tugged on their ears and stomped the ground, their bodies moving and creating a new rhythm that the men had to change their claps to fit, the claps now being determined by the dancers moving, while the men got to stomping and shouting joyfully, syncopating their palms to the women and children and if the men got off beat they fixed that by paying close attention to the feet blurring and kicking and stomping near the fire so they laid down their instruments and played a song with their bodies and their heads got to nodding and hips to rocking to gyrating to the claps pulsating around them changing changing changing and their mouths open and the funk of the body let loose the sweat the stink all in the hair until somebody hollered something beyond a word and they kept on hollering it the sound leading into another sound into a new sound loud from the mouth like a spirit trying to answer the bodies or the bodies trying to answer the spirit that wouldn’t be contained as their legs kicked and their heads rolled until their movements spoke in Tongues and the throat got to letting out a moan here and a groan there and the sound of pain left their flesh while their muscular bodies and their thin bodies and their fat bodies and their sickly bodies glistened in the fire and every child screamed as they jumped and spun and every man clapped moaned and testified with their feet to what sounded like it hurt so bad must have hurt them so bad coming up out the body out the burning well of the throat out the wet of their spit wailing lifting up from the bodies now contortion-flexed and contracting on the ground eyes

fluttering in their heads the body creating a new way of being a new way of thinking creating a new knowledge that belonged to them—then Saint stopped moving and stood up; her body shook and shined. Her companion brought her a rooster and a knife. She struggled to keep herself still and raised her arms in the air, the rooster in one hand and the knife in the other, and screamed as she separated the rooster’s head from its body in one clean swipe. At that moment, Saint felt The Gate, the breach between the living realm and the spiritual realm, swing open over the creek. Everyone stopped moving. Their bodies heaved in the flame-bent light, in the grooves they made in the earth with their feet.

Without much thought, they all went to the creek and let the water’s flow rinse first their feet, then their knees as they knelt, then their faces, their entire bodies cleansed in the running water, the water taking with it all that wasn’t theirs to carry: their bruises, their traumas, their hardened melancholy. They returned to the fire to dry off and admire each other’s faces in the warm light. Out of breath, they sat and reclined, naked, and none rushed to hide themselves while the ground, the earth that had once haunted them, felt softer beneath them.

T[4]

he lay of the land in Ours: four horizontal roads stretching west to east, the northernmost street being Tanager, followed by Oriole, Freedom, and then Bank at the southern end of town. Intersecting those roads were unnamed roads that became First, Second, and Third, moving from the most western road to the most eastern.

Everyone decided if they wanted to change their own names or keep the ones they had. Someone said, “If our masters not no more our masters then they names our belonging anyway.” That seemed to settle it for some. They had their names for as long as they could remember and had shared those names with loved ones for just as long. But one woman did want to change

her name. She said, “From now on my name is Miss. Not Ren. Miss. And my second name is Love.” Miss Love they called her from there on out.

This caused a small commotion because not everyone had used the word “miss” as an honorific. “Mistress” or “master” they had used for any white woman, while a few Ouhmey had never spoken to a white woman before in their life, thus never needing an honorific for them. There were even some who never used “miss” amongst each other, choosing “mother,” “maman,” “gammy,” “sister,” “ma’am,” “nene,” or “elder” instead. So, when Miss Love shared her new name, they wondered why she would want to call herself a name absent of love or lonesome for it.

“What she want to miss love for?”

“Maybe she lost her husband years back. Or some children. Poor thing.”

“Then why not call herself Have so she can have her some new love?”

“She got the right to miss it if the kind she want not here. I might call myself Miss. Miss Wife, cause I shole miss her. She was selled a year after we was married.”

And that’s how Paton became Miss Wife.

T�� ���� �� D�������� neither encouraged nor discouraged Negroes from working there as long as they arrived on time, behaved themselves, and left when time to leave. Plenty of work needed doing, and the white population would pay; they would usually pay less, but they would pay.

The distance between Ours and Delacroix was walkable, tested by Franklin Chisholm, a wiry man with a penchant for keeping to himself, who acted as guardian of Thylias Chisholm, a heavyset and reticent fifteen-yearold girl, though she and the rest of Ours thought she was older. Franklin headed north to find work, to see if he would be accepted in some fashion. “What you good at?” he asked himself, and responded that he could handle any animal and butcher it just as easily. That is the job he found for himself at York’s Butchery. When he returned to Ours, he said it took him an hour to get there. “Took no time at all and with a horse it be quicker,” he said.

Before anyone headed north, Saint had placed a stone with a dollar coin tied to it beneath a bush behind her house. She covered the stone in lemon grass and grain alcohol a week prior to everyone’s travel. The Ouhmey went up a few at a time and many found something to do: watching the young ones, cleaning houses, cobbler work and shoe shining, baking, and farming. Saint smiled when each one returned successful.

Miss Wife had the most difficulty finding work. When he gave his name to interested parties, they thought he wanted to make a fool of them.

“First name,” they would ask.

“Miss, sir,” Miss would respond.

“Pardon?”

“Miss.”

“Spell it.”

“M-I-S-S.”

“Is that short for something?”

“Miss my name.”

“Last name, then.”

“Wife.”

They sent him home that moment. After several tries over the course of several days, he returned each time more dejected than before. Ours, then, would be where he worked, and he wouldn’t be the only one. Miss Love worked in Ours, too, as a baker, offering her skills in exchange for carpentry, some sewing, a week’s worth of foot rubs.

“Whatever you want, I’ll make it right,” she would say, and kept her word.

Her sincerity made her popular. “I’ll make it right,” she said each time, and each time it felt as though she knew exactly the burden her customers needed lifted, believing her baking would get the job done. Corn bread muffins, pound cakes, small loaves with dried fruit and chocolate in them. Each seemed to be their own remedy for her customer’s tribulations.

Miss Wife had no skills of his own. He was a young man, registered in the so-called master’s burned ledger of slaves as being twenty years old for better to sell him if needed, but he was actually twenty-seven. He wasn’t

very handsome and boomed when he spoke, so there was no superficial reason to want to be near him and he knew it. He punched the ground and cried into the road after Delacroix made it clear they wouldn’t allow him to work within its town limits. No one in Ours needed to work because Ours had everything they needed, but pride was on the line and to be a working people meant a lot to them.

Miss Love took pity on the man. In her thirty-three years she had never seen someone so distinctly useless. She understood even more why he missed his wife so. ‘He may never get another,’ she thought, and invited him in to teach him a different way to use his hands.

The man Miss Love had legally married in a two-window cabin, witnessed by her then so-called master, a few enslaved Africans, and a frenzied menagerie of farm animals, wasn’t the man she loved, and she was thankful he didn’t stay with her. Whatever happened to him she had no clue, just assumed he had run away or been sold off. The latter made her terribly sad, so she decided only to assume he ran off in the middle of night into the surrounding woods and did so because he wanted freedom more than a wife who didn’t want him.

She tended to the world with this ambivalence, doing things for love of mankind with zero interest in loving a specific man, though not minding if a specific man loved on her enough to convince her he should be allowed to stick around for the time being. Specificity bored her, such that when her husband went missing, she then started to have feelings for him again as if his no longer being there somehow made him larger than he had been and therefore more possible in his largeness. Miss Wife, with the changing of his name into pure longing, confused Miss Love with his determination to be with a woman forever, a woman who would be there, just be there and nothing more.

It didn’t take long for Miss Wife to propose to Miss Love and it took even less time for her to reject him. In 1840, he tried again. He had been baking with her for five years by then and secretly developed his own recipe during that time. On the days Miss Love spent hours at the Delacroix market, Miss Wife managed the bakery, cooking milk down with sugar and

butter. He discovered for himself caramel but called it brown cream. By the time Miss Love returned, Miss Wife had spilled hot brown cream on his arm that left a burn in the shape of a smile. More importantly, though, he had baked a three-tier cake covered in brown cream.

“You made caramel,” she said. “You made a whole caramel cake. Who taught you that?”

“A what? This here brown cream,” Miss Wife said.

“What you made is caramel and”—Miss Love swiped her pinky across the top of the cake and collected a generous lump and tasted—“Oh, Miss.”

“I made it for you,” he said.

Miss Love teared up. The last time someone gave her something, she didn’t want it. Her legal husband had given it to her, her legal husband to whom she was still married but hadn’t seen in years, so much time gone by that she couldn’t recall his face. He had meaningfully but immaturely brought to her a gift. “This for you,” he had said, and held his palm open to reveal a light gray stone. She rubbed and rubbed that stone to calm her nerves, its smoothness to her the best gift anyone could’ve given her. She put it under her pillow and rubbed it until she fell asleep each night. But then he went missing and the stone with him, which let her know that he meant to keep the stone with him always and had simply loaned it to her. He left his wife but kept the rock.

“Miss Love,” Miss Wife said, but she had already walked away, shaking her head as she exited the front door and scurried down the road.

Thereafter, Miss Wife left his home in the morning and came to work face-to-face with Miss Love’s silence. They didn’t speak and the sound of dough slapping across the table and pans clanking into the oven were heightened into torture by this silence. Miss Wife stole glances of Miss Love, hoping to catch her doing the same, but she spent the day looking past him as though he were a tree—baffling, intrusive, but a nonevent after all—that had grown in the middle of the bakery, as though he didn’t make brown cream just for her the day before.

On the third day of silence, Miss Wife asked his friend Aba for advice and received a shave. Aba, who sold most of the fruit in Ours, was sitting

outside on his porch, cutting up small apples into halves and eating them seeds and all. People thought him strange but wise, the closest thing to a confidant Saint had, and besides bartering and selling meticulously picked fruit already washed in a bucket beneath the selling table, he passed along advice that often made little sense to those who received it.

While Aba rubbed Miss Wife’s face with oak ash soap, Miss Wife complained about the silence he had been receiving from Miss Love. Aba slid the blade down Miss Wife’s cheek and tufts of curly black hair followed. The glossy curls landed on Aba’s porch and Miss Wife’s bare shoulders, the dark brown cheek smoothed and shining.

“You was looking wolfish,” Aba said, turning Miss Wife’s face by the chin to observe his work. He smiled. “Now you just look mannish.” Aba carried over a bucket of water for Miss Wife to use as a mirror. “See yourself as yourself and tell yourself nice things.”

“That’s me?” Miss Wife asked. It had been years since he had a proper shave by skilled hands. He knew Aba was a friend because of how beautiful Aba made him feel. A good friend will show you the good they see in you.

“See what she say tomorrow about today’s you,” Aba said. “If she got a pea of sense, she’ll lose her senses and be with you.”

On the fourth day of silence between the two, Miss Love left the last business hour of the bakery in Miss Wife’s hands and took an evening stroll, flustered by Miss Wife’s new appearance that broke her into a sweat as she stole glances while sweeping flour from table to hand but missing her hand. She returned just before dark with creek water at the hem of her dress and all about her legs. ‘Just a dip,’ she thought when she arrived at Creek’s Bridge. ‘Just a toe.’

The walk had been tiring but necessary. It was a warm March day, warmer than natural, but the water still ran cold with winter. By the time she reached her home, the sun had arced down into a basket of trees, one tree much larger than the others. She wouldn’t live to see the day when the children named that tree God’s Place.

The creek lay east, just outside of town, and ran north to south like a minor Mississippi River. Someone decades before had built a small but

beautiful open-air bridge. No intricate railings and no baroque deck. Just a swift cobblestone arch over a trench of shallow, moving water. It was out of the ordinary to see stonework in a place where everything, even teeth, was made from wood, as though the bridge itself were a gateway to another world. She wondered if during her brief stay in that other world she saw Miss Wife naked amongst the rest of her neighbors. It seemed recent that she and everyone else had sat nude as opossums down there in the wet with Saint. Would she be able to remember seeing a man of whom, at the time, she had no awareness?

Many of the folks in Ours still carried with them a broken-mirror self they were figuring out how to piece back together. They saw the shards of who they were and couldn’t fathom how to make themselves whole again. ‘Just pick one,’ Miss Love thought, ‘just pick up a shard and know that be you looking back at you.’ It made sense when she first thought it, but now, seeing all the stones in the creek, so many smooth stones but none of them her original gift, she realized they were once part of a larger stone. The entire mirror needed fixing, every shard in its place to make the whole. That’s when she understood the truth about her hurt. It wasn’t her legal husband taking the stone that had affected her so; it was that the taking had attached to it a part of her that was hollow, and now even the hollow was gone.

S����� ���� � halved blood orange, and Miss Wife was sitting in a chair in front of Miss Love’s home. She had to let him know that during business hours he could linger all he wanted, but when night came waltzing down the road, the bakery became her house again, like a fairy tale, and he had to waltz down the road as well, back to his own private space in the world.

“We closed now,” she said, which were the first words spoken between them in days. “We closed,” she repeated. And he sat there as though he didn’t hear her, staring off to the west as the sun dropped, and it seemed to