https://ebookmass.com/product/i-survived-

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

I Got Something to Say 1st ed. Edition Matthew Oware

https://ebookmass.com/product/i-got-something-to-say-1st-ededition-matthew-oware/

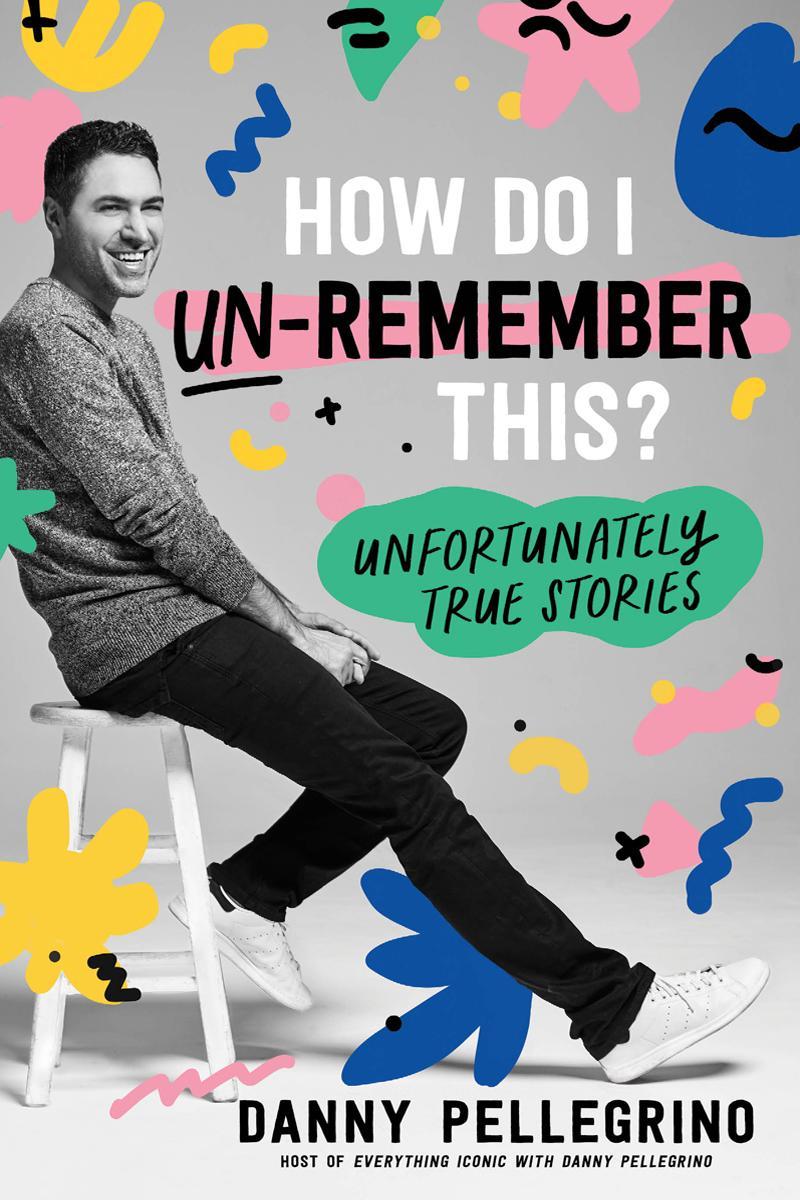

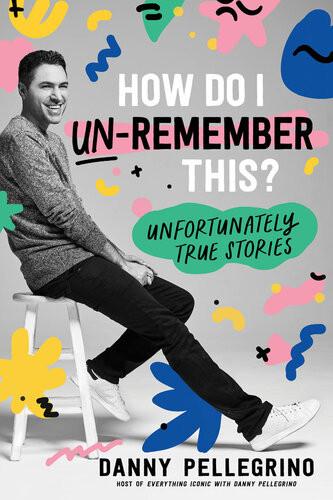

How Do I Un-Remember This? Danny Pellegrino

https://ebookmass.com/product/how-do-i-un-remember-this-dannypellegrino-2/

Imperialism And Capitalism, Volume I: Historical Perspectives 1st Edition Edition Dipak Basu

https://ebookmass.com/product/imperialism-and-capitalism-volumei-historical-perspectives-1st-edition-edition-dipak-basu/

How Do I Un-Remember This? Danny Pellegrino

https://ebookmass.com/product/how-do-i-un-remember-this-dannypellegrino/

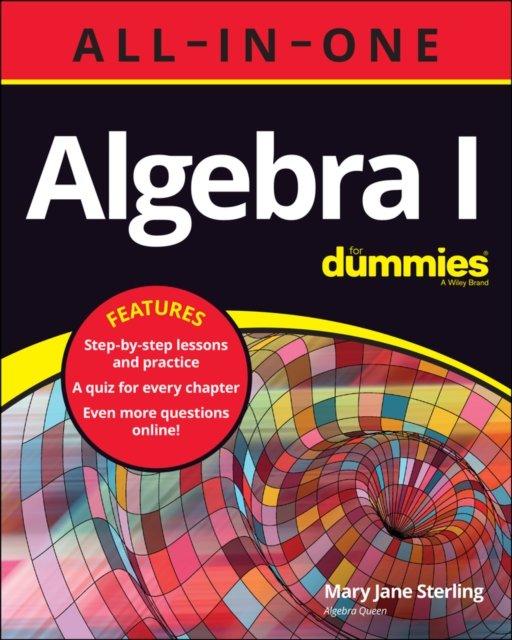

Algebra I All-in-One for Dummies 1st Edition Mary

Sterling

https://ebookmass.com/product/algebra-i-all-in-one-fordummies-1st-edition-mary-sterling/

How Do I Un-Remember This?: Unfortunately True Stories

Danny Pellegrino

https://ebookmass.com/product/how-do-i-un-remember-thisunfortunately-true-stories-danny-pellegrino-2/

How Do I Un-Remember This?: Unfortunately True Stories

Danny Pellegrino

https://ebookmass.com/product/how-do-i-un-remember-thisunfortunately-true-stories-danny-pellegrino/

I Promise It Won't Always Hurt Like This: 18 Assurances on Grief Clare Mackintosh

https://ebookmass.com/product/i-promise-it-wont-always-hurt-likethis-18-assurances-on-grief-clare-mackintosh/

Spinoza, Life and Legacy. 1st Edition Prof Jonathan I. Israel.

https://ebookmass.com/product/spinoza-life-and-legacy-1stedition-prof-jonathan-i-israel/

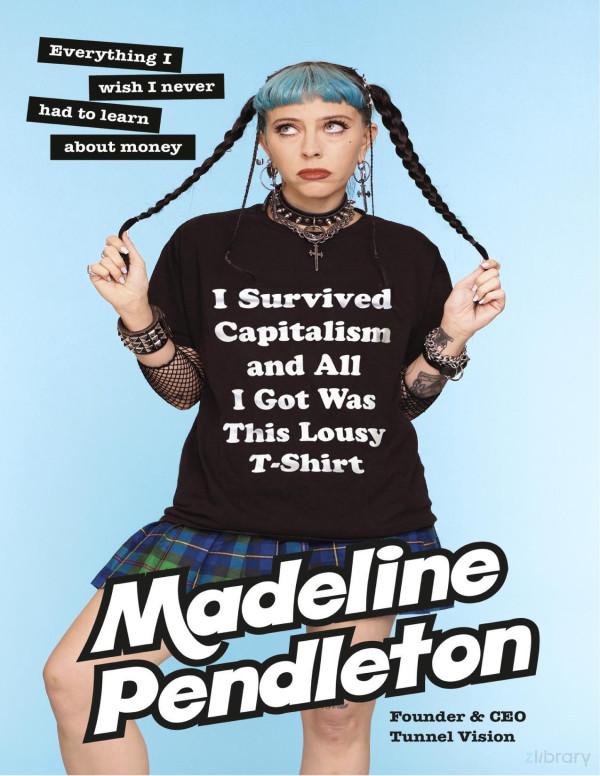

Copyright © 2024 by Madeline Pendleton Hansen

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www doubleday com

��������� and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Cover photograph by Lizzie Klein

Cover design by Madeline Pendleton and John Fontana

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pendleton, Madeline, author.

Title: I survived capitalism and all I got was this lousy t-shirt : everything I wish I never had to learn about money / Madeline Pendleton.

Description: First edition. | New York : Doubleday, 2024. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2023025110 (print) | LCCN 2023025111 (ebook) | ISBN 9780385549783 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780385549790 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Pendleton, Madeline, author | Internet personalities United States Biography | Businesspeople United States Biography | TikTok (Electronic resource)

Classification: LCC PN1992 9236 P46 A3 2024 (print) | LCC PN1992 9236 P46 (ebook) | DDC 302 23/1092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn loc gov/2023025110

LC ebook record available at https://lccn loc gov/2023025111

Ebook ISBN 9780385549790

ep prh 6.2 145872548 c0 r0

This book is dedicated to the Tunnel Vision team.

Camila, Kenna, Kelsey, Story, Sarah, Lizzie, Fern, Babylungs, Marcella, Aya, Ria, and Leeanna teamwork makes the dream work. Or whatever.

Capitalism: an economic system based on private ownership of property and business, with the goal of making the greatest possible profits for the owners

��������� ����������

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

���� �����

Contents

Preface

������������

CHAPTER 1 No Place like Home

���������� �������� �����: How to Build Credit

CHAPTER 2 Working for the Weekend

���������� �������� �����: How to Rent an Apartment or House

CHAPTER 3 Making It Out

���������� �������� �����: How to Get a Job

CHAPTER 4 Student Loan Debt, Here I Come!

���������� �������� �����: Navigating College

CHAPTER 5 When You’re Here, You’re Family!

���������� �������� �����: Figuring Out How Hard to Work

CHAPTER 6 Funemployment

���������� �������� �����: Making It Out of a Recession Alive

CHAPTER 7 We’re “Comfortable”

���������� �������� �����: How to Negotiate Higher Pay

CHAPTER 8 Rags to Rags

���������� �������� �����: How to Buy a Car

CHAPTER 9 Capitalism Killed My Boyfriend

���������� �������� �����: How to Manage Financial Stress

CHAPTER 10 From Each According to Their Ability, to Each According to Their Need

���������� �������� �����: How to Feel Happy When Everything Around You Feels Sad

CHAPTER 11 If You’ve Ever Read Rich Dad Poor Dad, You May Be Entitled to Financial Compensation ���������� �������� �����: How to Budget

CHAPTER 12 It’s Worse Than You Thought ���������� �������� �����: How to Get Out of Debt

CHAPTER 13 Home Is Where the Heart Is You Can Afford the Monthly Payments ���������� �������� �����: How to Buy a House

CHAPTER 14 Whoa, What Happened?

���������� �������� �����: How to Run an Equitable Business

CHAPTER 15 And the Money Will Roll Right In ���������� �������� �����: How to Build a Better World

Epilogue: My Life Online Acknowledgments

Notes

Preface

Summer in Los Angeles is idyllic, with bright blue skies that seem almost painted on, like the city built a movie set just for you to live out your best California dreams, act by act. I woke up to the warmth of the Southern California sun on my face. The room was quiet around me; I kept my eyes closed, hoping to stave off the day for a few minutes more. Beside me, MoDog rustled.

“That’s weird,” I thought to myself, and opened my eyes. The bedroom came into focus around me, with the floor-to-ceiling windows that opened up to the backyard where a waterfall gently trickled from the hot tub to the swimming pool and koi swam about in a pond, creating the faint sound of running water in the distance. Mo-Dog shook the blankets off her and walked up to me on the bed, wagging her tail and licking my face. I laughed and pushed myself upright. Time to get up, I guess.

“What are you doing here?” I asked her. She was rolling around on her back now, the comforter all scrunched up around her; she had one foot in her mouth. She was an unusual sight in the house that early in the day. Most mornings, she woke up with Drew—early with the sunrise. He’d walk around the house, talking gently to Mo-Dog in an upbeat chirping voice while he went through his morning routine. She’d bounce beside him, the tags of her collar jingling softly, while he made me coffee in the kitchen. Then, he’d leave a coffee by my bedside, kiss me on the forehead, and take Mo-Dog out for a morning hike in the canyon by our house. This morning, though, there was no coffee to be found and Mo-Dog was still there, looking anxiously at me like she was waiting for something to happen.

“I’m not taking you on a hike,” I whispered to her. “You know I’m not much of an outdoors person!” She stared up at me, her big black eyes wet with anticipation, her tail wagging behind her.

“I will not be pressured!” I said to her playfully.

I walked to the kitchen to make myself coffee, Mo-Dog bouncing along beside me. Most days, I sipped my coffee in the kitchen and waited until Drew and Mo-Dog came back from their morning hike. He’d open the front door and she’d run in, full force, straight up to me to lick my leg and spin around in circles, a ball of excitement and frenetic energy. He was always a few steps behind her, already taking off his sweaty T-shirt, ready to kiss me good morning and ask me how I slept. We took our morning shower together, every single day, a ritual. He washed my hair and we talked about the upcoming day, laughing at inside jokes and already planning dinner. Sometimes, after he got out of the shower, he wrote notes for me on the bathroom mirror, things like “I love you” with big hearts drawn everywhere. I wondered if he’d left me a note there this morning. I walked back into our bedroom, past the closet he’d built for me and into the bathroom, with its huge walk-in shower and wall full of mirrors, but there was nothing. “Hm,” I thought to myself. Strange.

Back in our bedroom, the old smelly boots and ripped-up jeans he wore every day were thrown onto a chair near my side of the bed. I picked up his jeans and folded them, keeping the belt on like he always did. They smelled like him, a mixture of tangerines and incense and our soap, and I smiled.

An hour or so passed with no sign of Drew. I wondered if maybe there’d been an emergency at work. He’d been running into some issues at the business, money issues mostly, and was in the process of completing a Chapter 11 bankruptcy, selling the business to a friend. There were papers to submit and forms to file and reports being constantly run. I ran out front to check the driveway to see if maybe he’d gone to a meeting I’d forgotten about. But his big blue pickup truck was still there, parked in the driveway where we’d left it when we came home the night before from my birthday dinner. I texted his friend Paul.

“Have you seen Drew?” I asked.

Almost instantly, Paul replied, “I’m coming over.”

I furrowed my brow. Coming over? What did that mean?

I looked at Mo-Dog, who was starting to seem a little thrown off by our lack of morning routine as well. What if something had happened to him, I thought, on his morning run. What if there was an accident and he was hurt? I clipped Mo-Dog’s leash to her collar and we left the house, walking to the end of the corner and turning right, heading past the heavy traffic of Mulholland and down into Fryman Canyon. There, a police car was parked, with the entrance to the hiking trail blocked off with yellow tape. A police officer stood guard at the top of the canyon. I walked up to him, Mo-Dog in tow.

“Excuse me,” I said. “Has a hiker been injured? My boyfriend hasn’t come home and I’m just wondering if maybe he’s stuck at the bottom of the canyon?”

“There’s been an injury,” the police officer said curtly.

I felt a wave of relief wash over me. It must be him, I thought. Maybe he sprained an ankle. The canyon was steep and full of uneven terrain at the bottom. It would be easy to do, and hard to climb back up it without a working foot. Every time I tried running with him down there, I fell on a rock or tree root there at the bottom.

“Can you tell me if it’s my boyfriend?” I asked. “He doesn’t bring his phone when he goes out for a run. I could describe him maybe to you?”

The police officer shook his head. “I’m afraid I can’t identify anyone, not properly—but if you show me a picture, I can let you know if it resembles the injured hiker or not.” “Yes,” I said. “Perfect. One second.” I pulled out my phone and opened my photos. The most recent photo in the camera roll was us together the day before, making a funny face into the camera. We sent it to my friend. I decided it looked too strange to show the officer, so I swiped backwards a few, finding a photo I’d taken of Drew just a couple of days before, in front of a piece of graffiti that read “It’s a long way to the top if you want to rock and roll.” His long hair was hanging in his face and you could see his tattoos

in it, covering both arms. I spun my phone around and showed the police officer.

“Here,” I said. “This is him.”

The officer squinted for a second before nodding. It was a match.

“Great,” I said. “Okay, perfect. I live just around the corner. Can I wait there until he’s brought back up? Will you come let me know?”

The officer nodded again, grimly, and I gave him our address.

“Thank you!” I beamed, before turning around and walking Mo-Dog back to our house.

Back at the house, Paul was just arriving, with a woman I’d never met before. She seemed like a new girlfriend. They were somber and quiet.

“It’s okay,” I told Paul, smiling. “He was injured, I think, on his morning run. I’m sure it’s just a sprained ankle or something. The hill is just so steep, you know?”

Paul winced, then tightened his lips. “We’ll wait anyway,” he said, “just to be sure.”

We sat together in the living room. I tried my best to make small talk with Paul’s new girlfriend, but she seemed strained in a way I couldn’t quite make sense of. I drank coffee and made jokes, but her face contorted into a strange grimace each time. A few minutes later, there was a knock at the door. Paul jumped up to get it, and when he opened it, the police officer from the canyon was there. They spoke quietly, in hushed tones to each other. I craned my neck to see past Paul at the door, watching the police officer speak.

“He was having money trouble,” I overheard Paul say, and the police officer nodded. A few seconds later, he closed the door.

Paul turned to face me. “Madeline,” he said, softly but with resolve, “Drew is dead.”

I felt the breath leave my body, my chest tightening as I exhaled, and I fell to the floor.

“You need to hear this,” he told me, as I clutched the cool tile floor trying to find my breath. “He killed himself this morning. A hiker found his body on the trail and called the police.”

In the canyon near our house, the same canyon where Drew played me songs on his guitar and we went on long evening walks and made plans for our future, Drew overwhelmed with financial stress and unsure of a way out—shot himself in the heart. Everyone saw it coming but me. That day, I learned a horrible lesson: capitalism is a matter of life and death. The stakes are high, and if you lose, it might come for you in ways you’d never expect.

INTRODUCTION

At the age of twenty-eight, I was earning $19,000 per year in Los Angeles and barely scraping by. I had $65,000 in debt student loans, maxed-out credit cards from emergencies like my 1997 Saturn breaking down all the time, and a car payment for a newer 2001 Volvo that I financed when I finally realized the Saturn might never stop breaking down. The Volvo was supposed to be a more reliable car. Spoiler alert: it wasn’t. Interestingly enough, though, it did have a spoiler on it—right there on the back above the windshield which should have been my first sign that it was not a good year, make, or model for Volvo.

The year was 2014. Median rent for a studio apartment in Los Angeles was $896 per month, or well over half of my income before taxes. The United States Housing and Urban Development Department says paying anything over 30 percent of your income towards housing makes you costburdened, and anything over 50 percent makes you severely cost-burdened. I was in the severe range. I woke up in the middle of the night, nearly every night, gasping for breath and shaking. In my nightmares, I saw credit card bills and eviction notices. The anxiety seemed to flow through my veins, itching and scratching just under the surface of my skin. Sometimes I’d hyperventilate. Other times I’d cry. Often I’d do both.

Money is both a practical and deeply emotional thing. On the one hand, it’s a math problem. You add up your expenses and subtract them from your monthly income. It’s cold and calculated and precise. On the other hand, if the numbers don’t add up quite the way you’d like, it feels less like a math problem and more like a you problem. We carry with us the fear of not making ends meet, the shame of not earning more money, and the guilt over how we’re spending the money we have. We carry generational

trauma from the financial mistakes of our families before us, and we project our own financial mistakes out into the world around us, influencing the lives of everyone with whom we come into close contact. Financial issues are the fifth leading cause of divorce in the United States, as well as a leading predictor in instances of depression. In 2021, 73 percent of Americans ranked financial issues as their number one cause of stress above politics, work, or family and these numbers are highest in Generation Z and Millennials, with over 80 percent of people born after 1980 reporting that they find their finances to be a source of stress.

I never wanted to write a book about money. I wanted to read a book about money, a book that acknowledged the financial reality that our generations were born into. What I found instead were books written by men much older than me about how to survive in a world that didn’t seem to exist anymore. Adages that might have sounded sagacious and wise in the past like only spending 25 percent of your monthly income on housing seemed ludicrous and out of touch by the time I became an adult. In 2022, the U.S. minimum wage is still stuck at $7.25 per hour or $15,080 per year, meaning you would have to pay just $314 per month to fall under that 25 percent rent threshold. Median rent in the United States is currently $1,253 per month, or roughly four times that. It’s been the longest stretch in history where we haven’t seen an increase in the federal minimum wage, meaning the real value of a minimum-wage worker’s paycheck is worth 17 percent less than when it was implemented ten years ago. If we look back at the minimum wage prior to that, the data is even more sobering. The minimum wage today is worth 31 percent less than it was in 1968. By contrast, housing prices have more than doubled when adjusted for inflation.

Millennials and Generation Z are currently contending with an unprecedented financial reality in the United States. Housing is more expensive compared to wages than ever before in U.S. history. CEO compensation has grown 1,322 percent since 1978, compared to just 18 percent for the average worker creating the largest income gap between the rich and poor since 1928, before the Great Depression began. College has increased nearly 169 percent in cost since 1980, nearly 10 times the

increase in typical workers’ wages during that same period, making a college degree more expensive now than ever before. The number of Americans who have medical debt is up to an all-time high of 50 percent as of 2020. In short, life is getting more expensive by the day, but pay for most people in the United States isn’t rising to meet those increasing costs. The financial worries of Millennials and Generation Z are not the same as the worries of our parents. We’re facing increasing pressure to do more with less, and the old guidebooks written by generations who came before us are not helping.

This book is the story of how I learned to navigate finances in this unprecedented time and went from sleepless nights gasping for air to owning my own home, running a multimillion-dollar business, and sharing the profit and wages from that business equally among myself and every employee to ensure a better quality of life not just for me but for everyone there. It’s the story of my own struggles to understand class, money, financial literacy, business ownership, and monetary planning, all while acknowledging this system is so deeply flawed that it makes survival seem nearly impossible. This is a book about my life, but it’s also a book about so many people in my age range who have also lived a life marked by debt, low incomes, high costs, class identity struggles, and a hopelessness about their own financial future. This is the story of how I came to understand the rules of money, a game we are all forced to play, and how I learned to bend those rules just enough to create a life where the people around me are happy, safe, and secure. This is a story about capitalism, and how if we’re lucky —we might survive long enough to see a better system, a brighter future, take its place.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

"The Indian National Congress," he wrote, "is avowedly national in its name and scope. The Provincial Congresses which meet in every province for the discussion of provincial matters, unite together in a National Congress, which is annually held at a chosen centre, for the furtherance and discussion of national interests. A Congress consists of from five hundred to one thousand of the political leaders of all parts of India, comprising representatives of noble families, landowners, members of local Boards and municipalities, honorary magistrates, fellows of universities, and professional men, such as engineers, bankers, merchants, shopkeepers, journalists, lawyers, doctors, priests and college professors. The delegates are able to act in concert and to declare in no uncertain accents the common public opinion of the multitude of whom they are the mouthpiece. They are as representative in regard to religion as to rank and profession; Hindus, Parsis, Mohammedans and Christians have in turn presided.

"The deliberations are marked by acumen and moderation. The principal items of their propaganda constitute a practical programme displaying insight and sagacity, and covering most of the political and economic problems of the Indian Empire. I take it upon myself to say, as a watchful eye-witness from its birth, that the Indian National Congress has discharged its duties with exemplary judgment and moderation."

Sir Henry Cotton, The New Spirit in India (North American Review, November, 1906).

The meeting of this Indian Congress in 1908 was held at Madras on the 27th of December, not long after Lord Morley had explained his plan for the enlargement of the Legislative Councils in India and for the election of a certain number of their members by popular vote. In the address of the President of the Congress, Dr. Rash Bihari Ghose, the proposed reforms

were discussed at length, and welcomed with warmth, as going near, apparently, to satisfying the claims of the majority of those represented in the Congress. "We are now," said the speaker, "on the threshold of a new era. An important chapter has been opened in the history of the relations between Great Britain and India a chapter of constitutional reform which promises to unite the two countries together in closer bonds than ever. A fair share in the Government of our own country has now been given to us. The problem of reconciling order with progress, efficient administration with the satisfaction of aspirations encouraged by our rulers themselves, which timid people thought was insoluble, has at last been solved. The people of India will now be associated with the Government in the daily and hourly administration of their affairs. A great step forward has thus been taken in the grant of representative government for which the Congress had been crying for years. … We do not know what the future destiny of India may be. We can see only as through a glass darkly. But of this I am assured, that on our genuine co-operation with the British Government depend our future progress and the development of a fuller social and political life. Of this also I am assured, that the future of the country is now in a large measure in our own hands."

At about the same time the All-India Moslem League held its meeting at Amritsar, and gave an equally hearty welcome to the principle of the proposed reforms, but appealed against the mode of election contemplated, which might be to the disadvantage of the Moslem minority. In the address of the President, Mr. Ali Imam, he said: "It is impossible for thoughtful men to approach the subject without regard to the pathetic side of the present situation. {317}

It is the liberalism of the great British nation that has taught Indians, through the medium of English education, to admire democratic institutions, to hold the rights of the people sacred above all rights and to claim for their voice

first place in the government of the country. The mind of close upon three generations of the educated classes in the land has been fed on the ideas of John Stuart Mill, Milton, Burke, Sheridan and Shelley, has been filled with the great lessons obtainable from chapters of the constitutional history of England and has been influenced by inexpressible considerations arising out of the American War of Independence, the relation of Great Britain with her Colonies, and last, though not least, the grant of Autonomy to the Boers after their subjugation at an enormous sacrifice of men and money. The bitterest critic of the educated Indian will not hold him to blame for his present state of mind. It is the English who have carefully prepared the ground and sown the seed that has germinated into what some of them are now disposed to consider to be noxious weed. It will be a dwarfed imagination however that will condemn the educational policy of the large-hearted and liberal-minded Englishmen who laid its foundation in this country. Those who inaugurated it aimed at raising the people to the level where co-operation and good understanding between the rulers and the ruled are possible. Under the circumstances, the desire of the educated Indian to take a prominent part in the administration of his country is neither unnatural nor unexpected. …

"The best sense of the country recognizes the fact that the progress of India rests on the maintenance of order and internal peace, and that order and internal peace in view of the conditions obtaining in our country at present and for a very long time to come, immeasurably long time to come, spell British occupation. British occupation not in the thin and diluted form in which Canada, Australia and South Africa stand in relation to England, but British occupation in the sense in which our country has enjoyed internal peace during the last 50 years. Believe me that as long as we have not learnt to overcome sectarian aggressiveness, to rise above prejudices based on diversity of races, religions and languages, and to alter the alarming conditions of violent intellectual

disparity among the peoples of India, so long British occupation is the principal element in the progress of the country. The need of India is to recognize that true patriotism lies in taking measure of the conditions existing in fact, and devoting one’s self to amelioration. … The creed of the All-India Muslim League is cooperation with the Rulers, coöperation with our non-Muslim countrymen and solidarity amongst ourselves. This is our idea of United India."

These expressions from prominent leaders of the two principal races of India are quite in accord with the judgment of liberal-minded Englishmen, as to the present duty of their government to the people of this great Asiatic Dependency. They are quite in accord with the judgment that has dictated the measure undertaken by the present British Government. They recognize that the relation which England bears to India, however unjustifiable in its origin it may be, is one that cannot be suddenly changed without great danger and certain harm. As Goldwin Smith has said:

"To attempt to strike the balance between the advantages and disadvantages of British rule in India would be to enter into a boundless controversy. Foreign rule in itself must always be an evil. India was rescued by Great Britain from murderous and devastating anarchy. Though at the time she was plundered by official corruption of a good deal of the wealth which, being poor though gorgeous, she could ill afford to lose, she has since enjoyed general peace and order; both, we may be sure, to a far greater extent than she otherwise would have done. The deadly enmity between her races and religions has been controlled and assuaged. …

"It does not appear that there is any considerable migration from the provinces directly under British dominion to those which are under native rule. The people, no doubt, are generally fixed to their habitations by poverty and difficulty of movement; still, if they greatly preferred the native rule,

a certain amount of migration to it there would probably be. That the masses of India in general are miserably poor cannot be denied. The question is, whether under the Mogul Emperors they were better off. … The population has vastly increased, and its increase may in some measure account for dearth. With regard to fiscal and commercial questions, it may safely be said that, at all events in late years, there has been no disposition on England’s part to do anything but justice to India.

"India’s complaints, speaking generally, seem to be of things inseparable from foreign rule, the withdrawal of which would be the only remedy. But suppose British rule withdrawn from India, what would follow? Is there anything ready to take its place? would not the result be anarchy, such as prevailed when England came upon the scene, or a struggle for ascendency between the Mahometan and the Hindoo, with another battle of Paniput? Suppose the Mahometan, stronger in spirit though weaker in numbers, to prevail, would his ascendency be more beneficial and less galling to the Hindoo than is that of the English Sahib?"

Goldwin Smith, British Empire in India (North American Review, September 7, 1906).

Of the ultimate possibilities of a nationalized unification of the mighty masses of population in the vast peninsula, there can, perhaps, be as much or more said hopefully as against the hope. A writer who believes that there may be an independent India has put an outline of the argument, pro and con, in these few following words:

"India, we are almost tired of hearing, is as large as Europe, putting aside Russia and Scandinavia, with as great a population, as many diverse and heterogeneous nationalities, differing from each other in language, in custom, in religion,

and in everything that makes for individuality; and we might as well speak of the Indian nation as the European nation. …

To this contention Young India opposes the most emphatic contradiction. India is a nation, a people, a country: its interests and aspirations are one and unique. Railways, telegraphs, post-office, the Press, education, knowledge of English, have welded into one harmonious whole all the manifold centrifugal forces of its vast area.

{318}

Young India will quote Switzerland as an example of a country with several languages and two conflicting religions, and yet undoubtedly constituting a nation. If the only tongue in which the Madrassi and the Bengali can communicate is English, so let it be. It is sufficient that a medium of communication exists. And it does exist. The educated Indian speaks and writes in English as easily as in his own mother-tongue. It is in English that the most vehement tirades against British rule, whether printed, spoken, or dealt with in private correspondence, are hurled across the land. Politically speaking, Lahore is a suburb of Calcutta. The fact cannot be gainsaid and must be reckoned with. India, as a whole, as a political unit, has found a voice. There is a national India, as there is not a national Europe."

E. C. Cox, Banger in India

(Nineteenth Century, December, 1908).

This view recognizes, as was recognized in the address of the President of the All-India Moslem League, quoted above, that English rule and English influence have done much towards preparing both the country and the people for the self-government to which the latter are now beginning to aspire. It must be said, however, that most of this preparation has been casually consequent on policies that had no such deliberate intent. Until quite late years there is little sign to be seen in British Indian policy of a thought

of developing opportunity and capability in the people to become more than valuable customers and docile wards. While India was in the hands of a commercial company it was managed, naturally, like an imperial estate, with strictly economic objects in view. Even then there was wisely economic consideration given to the general welfare of the people; but it was welfare as seen from the estate-owners' standpoint. The proprietary government did many things for its subjects and servants; bettered their conditions in many ways; added greatly to the equipment of their lives; but it did very little, if anything, toward putting them in the way of bettering things for themselves. It contemplated nothing for India but the perpetuity of its management as an imperial estate, entailed in the possession of a proprietary race.

The taking of this imperial estate from company management into national management has not seemed hitherto to alter the business nature of its administration very much. Its many millions of inhabitants have been better governed and better cared for, without doubt; but the idea of benevolence to them has never been much enlarged beyond the idea of an honestly good overseeing care. Institutions have been provided or encouraged for the educating of a class among them which could be of useful assistance in the caretaking of the mass; but common education for the mass, to qualify them better for the care of themselves, received scant attention till 25 years ago. In the very explanation that is often given of the present discontent in India there is an impeachment of the past treatment of the country by its able and powerful masters. It is said that the educated Hindus find no satisfying career for themselves outside of the service of the government, and that an increasingly large class in excess of the openings which that service can afford has been educated in recent years; that, consequently, the swelling crowd of disappointed place-seekers, whose intelligence and ambition have been whetted in the higher schools and colleges of the Indian Empire, are the disturbers of public content. After a

century and a half of supreme British influence and power in India, there ought to have been more and better openings of opportunity for educated young Hindus than through the doors of public office. There would have been if the development of country and people had been conducted with more reference to their benefit, and with less close attention to the interests of British trade.

Since 1882-1883 there has been more endeavor to establish and assist native primary schools; but the percentage of population that they reach is small. The statistics given in an official "Statement exhibiting the Moral and Material Progress and Condition of India during the year 1905-1906" make the following showing:

Provinces. Number of Number of Institutions

Pupils

Bengal 43,996

1,232,278

United Provinces 15,708

576,336

Punjab 3,762

211,464

Burma 20,996

385,214

Central Provinces 3,090 209,680

Eastern Bengal and Assam 21,790

722,371

Coorg 116 4,666

North West Frontier Province 1,087 28,496

Madras Presidency 28,258

918,880

Bombay and Sind Presidency 13,865

736,209

Total 152,668

5,025,594

Except in the Punjab and in Eastern Bengal and Assam these figures include both public and private institutions of education, of all grades, from primary schools to colleges. All institutions in which the course of instruction conforms to standards prescribed by the Department of Education or by the University, and which either undergo inspection by the Department or present pupils at public examinations, are classed as "public," but may be under either public or private management. While the schools and colleges seem numerous, it will be seen that they average but 33 pupils each, and give teaching to a slender fraction of the children of the 294,000,000 of people under British rule. In the report from which we quote the proportion of pupils to the estimated population of school-going age is given as 28.4 per cent. of boys and 2.9 per cent. of girls in Bengal; 8.06 per cent. of boys and 0.96 per cent. of girls in the United Provinces; 21.8 per cent. of boys and 1.8 of girls in the Central Provinces; 28.2 per cent, of boys and 2.9 per cent. of girls in Eastern Bengal and Assam; 29 per cent. of boys and 5.4 per cent. of girls in Madras; 31.8 per cent. of boys and 6 per cent of girls in Bombay. The total expenditure on education, from all sources, including fees, was £735,043 in Bengal (increased to £830,415 in 1907-1908); £441,421 in the United Provinces (increased to £491,723 in 1907-1908); £331,038 in the Punjab; £218,445 in Burma; £145,389 in the Central Provinces; £318,788 in Eastern Bengal and Assam; £624,602 in the Madras Presidency (increased to £712,740 in 1907-1908); £685,444 in the Presidency of Bombay (increased to £756,168 in 1907-1908). Total in 1905-1906, £3,500,170. Education in British India cannot be made wide or

deep on expenditure of this scale.

{319}

Education in the literary meaning, then, was tardily undertaken and is very limited yet in its extent. Quite as tardy, and quite as scant in the measure until John Morley got the handling of it, has been the political training that England, greatest of political teachers as she has been for the world at large, has allowed her Indian subjects to receive. It must not be understood that nothing of self-government has been conceded hitherto to these people. The exact measure of their participation in the management of their own public affairs, and the period within which they have exercised it, are described in the official "Statement exhibiting the Moral and Material Progress and Condition of India" from which the above exhibit of educational institutions is taken. The following is quoted partly from the "Statement" of 1905-1906 and partly from the later one of 1907-1908:

"Local self-government, municipal and rural, in its present form, is essentially a product of British rule. Beginning in the Presidency towns, the principle made little progress until 1870, when it was expressly recognised by Lord Mayo’s Government that ‘local interest, supervision, and care are necessary to success in the management of funds devoted to education, sanitation, medical charity, and local public works.’ The result was a gradual advance in local self-government, leading up to the action taken by Lord Ripon’s Government in 1883-1884, and to various provincial Acts passed about that time, which form the basis of the provincial systems at present in force. Municipal committees now exist in most places having any pretension to importance, and have charge of municipal business generally, including the care and superintendence of streets, roads, fairs and markets, open spaces, water supply, drainage, education, hospitals, and the like. Local and district boards have charge of local roads,

sanitary works, education, hospitals, and dispensaries in rural districts. A large proportion of their income is provided by provincial rates. Bodies of port trustees have charge of harbour works, port approaches, and pilotage. There is also a smaller number of non-elective local bodies discharging similar duties in towns other than constituted municipalities, and in cantonments.

"The municipal bodies exist, raise funds, and exercise powers under enactments which provide separately for the special requirements of each province and of the three presidency capitals, Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras. In the municipalities as a whole about half of the members are elected by the townsfolk under legal rules; in every town some, and in a few minor towns all, of the members are appointed by the Government. In almost every municipal body one or more Government officials sit as members. The number of Indian and non-official members, however, in every province, largely exceeds the number of Europeans and officials. The municipal bodies are subject to Government control in so far that no new tax can be imposed, no loan can be raised, no work costing more than a prescribed sum can be undertaken, and no serious departure from the sanctioned budget for the year can be made, without the previous sanction of the Government; and no rules or bye-laws can be enforced without similar sanction and full publication.

"There were 746 municipalities at the end of 1907-1908, containing within their limits over 16 million people or 7 per cent. of the total population. Generally speaking, the income of municipalities is small. In 1907-1908 their aggregate income amounted to £3,910,000, excluding loans, sales of securities, and other extraordinary receipts. About 40 per cent. of the total is provided by Calcutta, Bombay, Madras, and Rangoon. …

"The interest in municipal elections, and in municipal affairs generally, is not usually keen, save in a few cities and large

towns; but, as education and knowledge advance, interest in the management of local affairs gradually increases. In most provinces municipal work is fairly well done, and municipal responsibilities are, on the whole, faithfully discharged, though occasional shortcomings and failures occur. The tendency of local bodies, especially in the smaller towns, is to be slow in imposing additional taxes, in adopting sanitary reforms, and in incurring new expenditure. Many members of municipal bodies are diligent in their attendance, whether at meetings for business or on benches for the decision of petty criminal cases."

The elected members of these municipal committees number less than five thousand. This, therefore, is the extent of the class in the whole of British India, which now receives an elementary political training. Nothing more is needed for proving that India cannot possibly be prepared for independent self-government.

In a memorable speech made by Lord Macaulay in 1833 he predicted a time when England’s Indian subjects might demand English institutions, and exclaimed: "Whenever the day comes it will be the proudest in English history." The day has come, and it does not bring pride to England; because her wards in India have not been made ready for what they ask. It will need time to repair the long neglect; but there is no grander fact in recent history than the beginning of the labor of repair. It is to be a work of education, not for the people of India alone, but for Englishmen as well. They are to learn, and have begun to learn, the mistake of egotism and self-sufficiency in their government of these people. Some months ago there was published in The Times of India, at Bombay, a number of articles on the causes of the existing discontent, some by English writers, some by Hindus, some by Mohammedans, all seriously and frankly studying the situation, and most suggestive in their thought. The cause emphasized most by one of the English writers is that which always has worked and

always will work when one self-complacent and self-confident people undertakes to be an overruling providence for another people, by making laws for it and managing its affairs. The more consciousness there is on the ruling side of just intention and superior knowledge, the less likely it is to satisfy the ruled; because the satisfying of its own judgment of what is good for the latter is assumed to be enough.

During the last half century, at least, the British Government has endeavored, without a doubt, to do good to its Indian subjects, and it has done them great good; but everything has been done in its own way, from its own points of view and upon its own judgment of things needful and good and right. And this is why its Indian subjects not only feel wronged, but are wronged.

{320}

As the writer in The Times of India reminds his countrymen, "right is a relative term," and not, he says, "as we Islanders would have it, an absolute one. A thing that is right for us, with our past training and traditions, may not only seem, but really be, a grave wrong to those whose environment differs from our own." He cites instances of grave mistakes in well-intended legislation that would have been avoided, if the makers of the laws had counseled sufficiently with natives of experience in the matters concerned. One example is in a land alienation act, for the Punjab, which was framed with purely philanthropic motives, being intended to free the native peasantry the ryots from thraldom to money lenders, but which, by making the recovery of debts difficult, has trebled the rate of interest to the ryot, who borrows just as much, and mortgages himself instead of mortgaging his land. Alluding to this and to another act of excellent intention but irritating effect, the writer says: "When these worthy aims of government were debated in the Bombay and Punjab legislatures, who was there, among the officials, in touch with Indian

feeling and sentiment? Who among the senators ever suggested the possibility that the evil of mortgage and borrowing was not intrinsically an evil in India, but that legislation our own past legislation had made it so? Was there no officer of government who could advise the authorities that every Hindoo, almost, is at heart a money lender; that it is second nature to him; that indebtedness in itself is neither reproach nor handicap in his eyes; and that if you take from him his freedom of barter you do take his life?"

"We have failed," says this writer, "to avail ourselves of the material we ourselves have trained." That, undoubtedly, is the cardinal mistake that the English in India have made. Until now, they have not taken the best of India into their confidence and their counsels.

Another of the writers referred to above gave another characterization of the British rule as the natives more generally feel it, in which a deeper working of more subtle irritations can be seen. He wrote:

"Personal rule, the will of the king, God’s anointed and therefore invested with quasi-divine sanction, is the only rule to which the East has been used, which it can like and respect. The people can understand, even while they suffer under, the most extravagant individual caprices; and when the tyranny becomes too intolerable, they always had in the last resort an excellent chance of being able to overthrow it. But they cannot and probably never will understand, still less appreciate, the cold, implacable, inhuman impersonality of the English government. They might as well be governed by a dynamo, without human bowels or passions. It cannot be humanly approached; it has no human side; its very impeccability is exasperating; and the exactitude with which it metes out its machine-made justice, according to inflexible rules and formulae into which no human equation enters, chills and repels the Eastern mind, and its strength is commensurate with

its remorselessness."

"They might as well be governed by a dynamo!" That, in this connection, is a powerfully expressive phrase. The dynamo and everything of a dynamic nature every mechanical motor-working of forces, whether material or political, are naturally congenial to the man of the Western world understandable by him, serviceable to him and they are not so to the man of the East. Somewhere in the process of their evolution the one got an aptitude for projecting work outwardly from the worker action at some remove from the actor shuttle throwing, for example, carried out from the weaver to the arms and fingers of a machine, and government from the personally governing will to an organic political system while the other did not. In this, more than in anything else, perhaps, the radical difference of nature between the Occidental and the Oriental peoples is summed up. The one is endowed with a self-enhancing power to act through exterior agencies, of mechanism in his physical labors, of representative institutions in his government, of systems and organisms in all his doings, which the other lacks.

This might have seemed a generation ago to set an insurmountable barrier against the passing of democracy and democratic institutions into Asia; but we have little right to-day to imagine that anything can stop their march.

INDIA: A. D. 1908. American Mission Schools.

See (in this Volume) EDUCATION: INDIA.

INDIA: A. D. 1908-1909.

Passage of the Indian Councils Bill by the British Parliament. Popular Representation in the Legislative Councils introduced. Lord Morley’s explanations of the Measure.

Appointment of a native member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council.

The great project of reform in the Government of India which Lord Morley, as Secretary for India in the British Administration, brought before Parliament in December, 1908, embodied fundamentally in what was known during the discussion of it as the Indian Councils Bill, had its origin more than two years before that time, not in the councils of the British Ministry, but in those of the Government of India. The facts of its inception and preliminary consideration were indicated in a British Blue Book of 1908 (Cd. 4426), which contained proposals on the subject from the Government of India, dated October 1, 1908, and the reply of Lord Morley to them, November 27. More recently the early history of the reform project was told briefly by the Viceroy of India, the Earl of Minto, in a speech in Council, on the 28th of March, 1909. He said:

"The material from which the Councils Bill has been manufactured was supplied from the Secretariat at Simla, and emanated entirely from the bureaucracy of the Government of India. It was in August, 1906, that I drew attention in Council in a confidential minute to the change which was so rapidly affecting the political atmosphere, bringing with it questions we could not afford to ignore, which we must attempt to answer, pointing out that it was all-important that the initiative should emanate from us, that the Government of India should not be put in the position of appearance of having its hands forced by agitation in this country or by pressure from home, and that we should be the first to recognize the surrounding conditions and place before his Majesty’s Government the opinion which personal experience and close touch with the everyday life of India entitle us to hold.

{321}

I consequently appointed the Arundel Committee. That minute

was the first seed of our reforms sown more than a year before the first anarchist outrage sent a thrill of shocked surprise throughout India the attempt to wreck Sir Andrew Fraser’s train in December, 1907. The policy of the Government of India in respect to reforms has emanated from mature consideration of political and social conditions, while the administrative changes they advocated, far from being concessions wrung from them, have been over and over again endangered by the commission of outrages which could not but encourage doubts as to the opportuneness of the introduction of political changes, but which I steadfastly refused to allow to injure the political welfare of the loyal masses in India."

The Indian Councils Bill was printed on the 20th of February, 1909, and its second reading in the House of Lords was moved by Lord Morley in an explanatory speech on the 23d. A prefatory memorandum accompanying the text of the Bill was as follows:

"The object of this Bill is to amend and extend the Indian Councils Acts, 1861 and 1892, in such a way as to provide:

"(i.)For an enlargement of the Legislative Council of the Governor-General and of the existing Provincial Legislative Councils;

"(ii.) For the election of a certain proportion of their members by popular vote; and

"(iii.) For greater freedom to discuss matters of general public interest and to ask questions at their meetings, and more especially for the discussion of the annual financial statements.

"The Executive Councils of the Governments of Madras and Bombay are enlarged, and powers are taken to create Executive Councils in the other Provinces of India, where they now do

not exist. Provision is also made for the appointment of Vice-Presidents of the various Councils.

"The details of the necessary arrangements, which must vary widely in the different Provinces, are left to be settled by means of regulations to be framed by the Government of India and approved by the Secretary of State."

In his speech on moving the second reading of the Bill, Lord Morley said: "I invite the House to take to-day the first definite and operative step in carrying out the policy which I had the honour of stating to your lordships just before Christmas, and which has occupied the active consideration both of the Home Government and of the Government of India for very nearly, if not even more than, three years. The statement was awaited in India with an expectancy that with time became almost impatience, and it was received in India and that, after all, is the point to which I looked with the most anxiety with intense interest and attention and various degrees of approval, from warm enthusiasm to cool assent and acquiescence. So far as I know … there has been no sign in any quarter, save possibly in the irreconcilable camp, of organized hostile opinion among either Indians or Anglo-Indians. …

"There are, I take it, three classes of people that we have to consider in dealing with a scheme of this kind. There are the extremists, who nurse fantastic dreams that some day they will drive us out of India. In this group there are academic extremists and physical force extremists, and I have seen it stated on a certain authority it cannot be more than guessed that they do not number, whether academic or physical force extremists, more than one-tenth, I think, or even 3 per cent., of what are called the educated class in India. The second group nourish no hopes of this sort, but hope for autonomy or self-government of the colonial species and pattern. And then the third section of this classification ask for no more than

to be admitted to co-operation in our administration, and to find a free and effective voice in expressing the interests and needs of their land. I believe the effect of the reforms has been, is being, and will be to draw the second class, who hope for colonial autonomy, into the third class, who will be content with being admitted to a fair and full co-operation."

As to the objections raised by the Mahomedans of India, to the plans of the measure for their representation in the Councils, Lord Morley announced the readiness of the Government to yield to them. "We," he said, "suggested to the Government of India a certain plan. We did not prescribe it, we did not order it, but we suggested and recommended this plan for their consideration no more than that. It was the plan of a mixed or composite electoral college, in which Mahomedans and Hindus should pool their votes, so to say. The wording of the recommendation in my dispatch was, as I soon discovered, ambiguous a grievous defect, of which I make bold to hope I am not very often in public business guilty. But, to the best of my belief, under any construction the plan of Hindus and Mahomedans voting together in a mixed and composite electorate would have secured to the Mahomedan electors, wherever they were so minded, the chance of returning their own representative in their due proportion. The political idea at the bottom of that recommendation which has found so little favour was that such composite action would bring the two great communities more closely together, and this idea of promoting harmony was held by men of very high Indian authority and experience who were among my advisers at the India Office. But the Mahomedans protested that the Hindus would elect a pro-Hindu upon it, just as I suppose in a mixed college of say 75 Catholics and 25 Protestants voting together the Protestants might suspect that the Catholics voting for the Protestant would choose what is called a Romanizing Protestant and as little of a Protestant as possible. … At any rate, the Government of India doubted whether our plan would work, and we have abandoned it. I do not think it was a bad

plan, but it is no use, if you are making an earnest attempt in good faith at a general pacification, out of parental fondness for a clause interrupting that good process by sitting too tight.

"The Mahomedans demand three things. I had the pleasure of receiving a deputation from them and I know very well what is in their minds. They demand the election of their own representatives to these councils in all the stages, just as in Cyprus, where, I think, the Mahomedans vote by themselves. They have nine votes and the non-Mahomedans have three, or the other way about.

{322}

So in Bohemia, where the Germans vote alone and have their own register. Therefore we are not without a precedent and a parallel for the idea of a separate register. Secondly, they want a number of seats in excess of their numerical strength. Those two demands we are quite ready and intend to meet in full. There is a third demand that, if there is a Hindu on the Viceroy’s Executive Council a subject on which I will venture to say a little to your lordships before I sit down there should be two Indian members on the Viceroy’s Council and that one should be a Mahomedan. Well, as I told them and as I now tell your lordships, I see no chance whatever of meeting their views in that way to any extent at all."

Turning to a much criticised feature of the projected remodelling of Indian Government namely, the announced intention of the Government to name an Indian member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council the Secretary reminded the House that this was not touched by the pending bill, for the reason that the appointment of that Council lies already within the province of the Crown. In meeting the objections raised to this part of the reform project, he amused the House greatly by remarking: "Lord MacDonnell said the other day: ‘I believe you cannot find any individual native gentleman who has enjoyed the general confidence who would be able to give

advice and assistance to the Governor-General in Council.’ It has been my lot to be twice Chief Secretary for Ireland, and I do not believe I can truly say I ever met in Ireland a single individual native gentleman who ‘enjoyed general confidence.’ And yet I received at Dublin Castle most excellent and competent advice. Therefore I will accept that statement from the noble lord. The question is whether there is no one of the 300 millions of the population of India who is competent to be the officially-constituted adviser of the Governor-General in Council in the administration of Indian affairs. You make an Indian a Judge of the High Court, and Indians have even been acting-Chief Justices. As to capacity, who can deny that they have distinguished themselves as administrators of native States, where far more demand is made on their resources, intellectual and moral? It is said that the presence of an Indian member would cause restraint in the language of discussion. For a year and a half I have had two Indians at the Council of India, and I have never found the slightest restraint whatever."

Debate on the Bill in the House of Lords was resumed on the 4th of March, and it was amended by striking out a clause which gave power to constitute provincial executive councils in other provinces than Madras and Bombay, where they were already existing. It then passed through Committee, and on the 11th of March it was read a third time and passed by the Upper House.

A fortnight later, Lord Morley brought into exercise the authority possessed by the Crown, to appoint on its own judgment a native member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council. His choice fell on a distinguished Hindu lawyer, Mr. Satyendra Prasanna Sinha, of whom the London Times, on announcing the appointment, said: "Mr. Sinha now fills the office of Advocate-General of Bengal, to which he was not long ago promoted, and he will succeed Sir Henry Richards as Legal Member of Council. Of his fitness to discharge the

departmental duties of his new position we make no question. Lord Morley has doubtless satisfied himself that the qualifications of his nominee in this respect will not discredit the experiment on which he has ventured. But, however high those qualifications, and however well they may stand the test of experience, gifts and attainments of another order are needed for the post to which Lord Morley has named him. A member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council is much more than a departmental chief. … For him there are no State secrets and no confidential documents. He has a right to know and to debate the imperii arcana. The most delicate mysteries of diplomacy, the most carefully guarded of military precautions, are trusted to his faith and to his discretion. Breadth of political knowledge and of judgment, insight into men and things, a sure sense and grasp of realities, coolness, courage, and rapid decision in emergencies, absolute impartiality between native races, creeds, and classes, and an instinctive devotion to England, to her traditions and to her ideals, are amongst the qualities which have been deemed the best recommendations for so immense a trust. Mr. Sinha may possess them all, but they are rare amongst the men of any race, and some of them are notoriously uncommon amongst Orientals."

This expresses the English opinion that objects to the admission of Indians to the Executive Councils of Indian Government, even while assenting to their representation in the Legislative Councils of the dependency. It is to be hoped that Mr. Sinha will help to weaken that opinion. Reports from India on the appointment were to the effect that it had given great general satisfaction.

On the return of the Councils Bill to the Commons the clause which the Lords had stricken out was restored, but in a modified form. Authority to extend the creation of provincial executive councils was given, but with the reservation to the House of Lords as well as to the House of Commons of a veto

upon the establishment of such councils in any new provinces, except Bengal. As thus amended the clause was accepted by the Upper House and became law, May 25, 1909.

The following are the essential provisions of the Act: "I.

(1) The additional members of the councils for the purpose of making laws and regulations (hereinafter referred to as Legislative Councils) of the Governor-General and of the Governors of Fort Saint George and Bombay, and the members of the Legislative Councils already constituted, or which may hereafter be constituted, of the several Lieutenant-Governors of Provinces, instead of being all nominated by the Governor-General, Governor, or Lieutenant-Governor in manner provided by the Indian Councils Acts, 1861 and 1892, shall include members so nominated and also members elected in accordance with regulations made under this Act, and references in those Acts to the members so nominated and their nomination shall be construed as including references to the members so elected and their election.

{323}

"(2) The number of additional members or members so nominated and elected, the number of such members required to constitute a quorum, the term of office of such members and the manner of filling up casual vacancies occurring by reason of absence from India, inability to attend to duty, death, acceptance of office, or resignation duly accepted, or otherwise, shall, in the case of each such council, be such as may be prescribed by regulations made under this Act:

"Provided that the aggregate number of members so nominated and elected shall not, in the case of any Legislative Council mentioned in the first column of the First Schedule to this Act, exceed the number specified in the second column of that

schedule.

" 2.

(1) The number of ordinary members of the councils of the Governors of Fort Saint George and Bombay shall be such number not exceeding four as the Secretary of State in Council may from time to time direct, of whom two at least shall be persons who at the time of their appointment have been in the service of the Crown in India for at least twelve years.

"(2) If at any meeting of either of such councils there is an equality of votes on any question, the Governor or other person presiding shall have two votes or the casting vote.

"3.

(1) It shall be lawful for the Governor-General in Council, with the approval of the Secretary of State in Council, by proclamation, to create a council in the Bengal Division of the Presidency of Fort William for the purpose of assisting the Lieutenant-Governor in the executive government of the province, and by such proclamation

"(a) to make provision for determining what shall be the number (not exceeding four) and qualifications of the members of the council; and

"(b) to make provision for the appointment of temporary or acting members of the council during the absence of any member from illness or otherwise, and for the procedure to be adopted in case of a difference of opinion between a Lieutenant-Governor and his council, and in the case of equality of votes, and in the case of a Lieutenant-Governor being obliged to absent himself from his council from indisposition or any other cause.

"(2) It shall be lawful for the Governor-General in Council, with the like approval, by a like proclamation to create a

council in any other province under a Lieutenant-Governor for the purpose of assisting the Lieutenant-Governor in the executive government of the province: Provided that before any such proclamation is made a draft thereof shall be laid before each House of Parliament for not less than sixty days during the session of Parliament, and, if before the expiration of that time an address is presented to His Majesty by either House of Parliament against the draft or any part thereof, no further proceedings shall be taken thereon, without prejudice to the making of any new draft.

"(3) Where any such proclamation has been made with respect to any province the Lieutenant-Governor may, with the consent of the Governor-General in Council, from time to time make rules and orders for the more convenient transaction of business in his council, and any order made or act done in accordance with the rules and orders so made shall be deemed to be an act or order of the Lieutenant-Governor in Council.

"(4) Every member of any such council shall be appointed by the Governor-General, with the approval of His Majesty, and shall, as such, be a member of the Legislative Council of the Lieutenant-Governor, in addition to the members nominated by the Lieutenant-Governor and elected under the provisions of this Act.

"4. The Governor-General, and the Governors of Fort Saint George and Bombay, and the Lieutenant-Governor of every province respectively shall appoint a member of their respective councils to be Vice-President thereof, and, for the purpose of temporarily holding and executing the office of Governor-General or Governor of Fort Saint George or Bombay and of presiding at meetings of Council in the absence of the Governor-General, Governor, or Lieutenant-Governor, the Vice-President so appointed shall be deemed to be the senior member of Council and the member highest in rank, and the Indian Councils Act, 1861, and sections sixty-two and

sixty-three of the Government of India Act, 1833, shall have effect accordingly.

"5.

(1) Notwithstanding anything in the Indian Councils Act, 1861, the Governor-General in Council, the Governors in Council of Fort Saint George and Bombay respectively, and the Lieutenant-Governor or Lieutenant-Governor in Council of every province, shall make rules authorising at any meeting of their respective legislative councils the discussion of the annual financial statement of the Governor-General in Council or of their respective local governments, as the case may be, and of any matter of general public interest, and the asking of questions, under such conditions and restrictions as may be prescribed in the rules applicable to the several councils.

"(2) Such rules as aforesaid may provide for the appointment of a member of any such council to preside at any such discussion in the place of the Governor-General, Governor, or Lieutenant-Governor, as the case may be, and of any Vice-President.

"(3) Rules under this section, where made by a Governor in Council, or by a Lieutenant-Governor, or a Lieutenant-Governor in Council, shall be subject to the sanction of the Governor-General in Council, and where made by the Governor-General in Council shall be subject to the sanction of the Secretary of State in Council, and shall not be subject to alteration or amendment by the Legislative Council of the Governor-General, Governor, or Lieutenant-Governor.

"6. The Governor-General in Council shall, subject to the approval of the Secretary of State in Council, make regulations as to the conditions under which and manner in which persons resident in India may be nominated or elected as members of the Legislative Councils of the Governor-General, Governors, and Lieutenant-Governors, and as to the

qualifications for being, and for being nominated or elected, a member of any such council, and as to any other matter for which regulations are authorised to be made under this Act, and also as to the manner in which those regulations are to be carried into effect. Regulations under this section shall not be subject to alteration or amendment by the Legislative Council of the Governor-General.

{324}

"7. All proclamations, regulations and rules made under this Act, other than rules made by a Lieutenant-Governor for the more convenient transaction of business in his council, shall be laid before both Houses of Parliament as soon as may be after they are made."

FIRST SCHEDULE.

MAXIMUM NUMBERS OF NOMINATED AND ELECTED MEMBERS OF LEGISLATIVE COUNCILS.

Maximum

Legislative Council.

Number.

Legislative Council of the Governor-General

60

Legislative Council of the Governor of Fort Saint George

50

Legislative Council of the Governor of Bombay

50

50

50

Legislative Council of the Lieutenant-Governor of the Bengal division of the Presidency of Fort William

50

Legislative Council of the Lieutenant-Governor of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh

30

Legislative Council of the Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of Eastern Bengal and Assam

Legislative Council of the Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of the Punjab

Legislative Council of the Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of Burma

30

Legislative Council of the Lieutenant-Governor of any Province which may hereafter be constituted 30

As will be seen, the Act only conveys in outline to the Government of India the authority needed for introducing the intended reforms, leaving all constructive details to be filled out by the latter in regulations and rules. Six months were occupied in that task by the Indian Government, and the resulting prescriptions were published on November 15th, in a document filling 450 pages of print. The following is a summary of them, communicated to The Times by its

Calcutta correspondent:

"They comprise, first, a short notice bringing the new Councils Act into force; secondly, the rules and regulations for guiding the constitution of the enlarged Imperial and Provincial Councils, with election rules; thirdly, rules for the discussion of the annual financial statement and general resolutions and for the asking of questions; and, fourthly, a Government resolution explaining the reasons for the changes made and their main details.

"The resolution shows that the Imperial Council will consist of 68 members, while the number of members in each of the Provincial Councils will be as follows: Bengal, 51; Madras and Bombay, each 48; the United Provinces, 49; Eastern Bengal and Assam, 43; the Punjab, 27; and Burma, 18.

"The Viceroy’s Council has an official majority of three, while all the Provincial Councils have non-official majorities, ranging from 14 in Bengal to three in Burma. In the Viceroy’s Council the Mahomedans will have in the first Council six members elected by purely Mahomedan electorates, and will also presumably get seats in Sind and the Punjab, as the resolution says that a representative of the Bombay landholders on the Imperial Council will be elected at the first, third, and subsequent alternate elections by the Sind landholders, the great majority of whom are Mahomedan, and at the other elections by the Sirdars of Gujarat and the Deccan, the majority of whom are Hindus.

"Again, the Punjab landholders consist equally of Mahomedans and non-Mahomedans, and presumably a Mahomedan will be alternately chosen. Accordingly, it has been decided that at the second, fourth, and alternate elections, when these two seats shall not be held by Mahomedans, there shall be two special electorates consisting of Mahomedan landholders who are entitled to vote for the member representing them in the

Imperial Council, and the landowners of the United Provinces and of Eastern Bengal and Assam respectively. The Bombay Mahomedan member of the Imperial Council will be elected by the non-official Mahomedan members of the Provincial Council.

"The tea and jute industries get five members on the Provincial Councils of the Bengals and Madras.

"All members are required to take the oath of allegiance to the Crown before sitting on any of the Councils, and no person is eligible for election if the Imperial or a Provincial Government is of opinion that his election would be contrary to public interest. This provision takes the place of the old power to reject members selected by the electorate.

"The examination of the annual financial proposals is divided into three parts. The first allows a chance for discussing any alteration in taxation and any new loan or grant to a local Government. Under the second any head of revenue or expenditure will be explained by the member in charge of the Department concerned and any resolution may be moved, and at the third stage the Finance Minister presents his budget and explains why any resolutions will not be accepted, a general discussion following.

"The resolution concludes as follows:

"The new Provincial Councils will assemble early in January and the Imperial Council in the course of that month. …

"‘The maximum strength of the Councils was 126; it is now 370. There are now 135 elected members against 39, while an elected member will sit as of right, needing no official confirmation. The functions of the Councils are greatly enlarged. Members can demand further information in reply to formal answers and discussion will be allowed on all matters of public interest. They will also in future be enabled to