https://ebookmass.com/product/the-biology-of-parasites-1stedition-ebook-pdf-version/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Introduction to 80×86 Assembly Language and Computer Architecture – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/introduction-to-8086-assembly-languageand-computer-architecture-ebook-pdf-version/

ebookmass.com

Stern’s Introductory Plant Biology 13th Edition – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/sterns-introductory-plant-biology-13thedition-ebook-pdf-version/

ebookmass.com

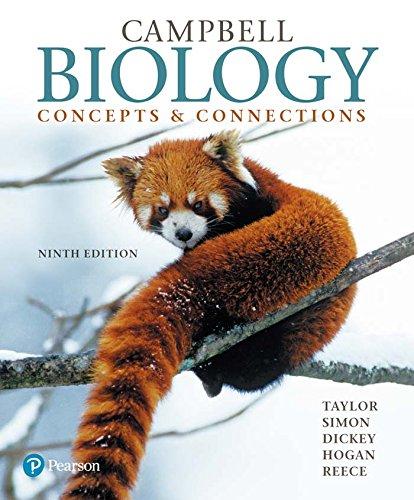

Campbell Biology: Concepts & Connections 9th Edition –Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/campbell-biology-conceptsconnections-9th-edition-ebook-pdf-version/

ebookmass.com

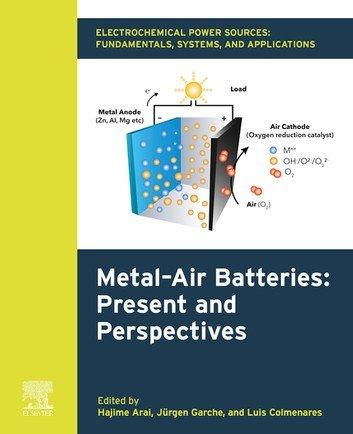

Electrochemical Power Sources: Fundamentals, Systems, and Applications: Metal-Air Batteries: Present

and Perspectives Hajime Arai

https://ebookmass.com/product/electrochemical-power-sourcesfundamentals-systems-and-applications-metal-air-batteries-present-andperspectives-hajime-arai/ ebookmass.com

https://ebookmass.com/product/gestao-de-investimentos-e-geracao-devalor-carlos-patricio-samanez/

ebookmass.com

The Wolf Wore Plaid: 6 (Highland Wolf) Terry Spear [Spear

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-wolf-wore-plaid-6-highland-wolfterry-spear-spear/

ebookmass.com

JACE: Summerset Shore University Book One N. Boeyer

https://ebookmass.com/product/jace-summerset-shore-university-bookone-n-boeyer/

ebookmass.com

Heat Transfer 1 Michel Ledoux

https://ebookmass.com/product/heat-transfer-1-michel-ledoux/

ebookmass.com

Materials

Science in Photocatalysis 1st Edition Elisa I. Garcia Lopez (Editor)

https://ebookmass.com/product/materials-science-in-photocatalysis-1stedition-elisa-i-garcia-lopez-editor/

ebookmass.com

eTextbook 978-9351500827 Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/etextbook-978-9351500827-discoveringstatistics-using-ibm-spss-statistics-4th-edition/

ebookmass.com

VI Contents

1.6.1.3ScenariosofDefenseReactionsAgainstParasites 63

1.6.1.4Immunopathology 67

1.6.2ImmuneEvasion 68

1.6.3ParasitesasOpportunisticPathogens 72

1.6.4HygieneHypothesis:DoParasitesHaveaGoodSide? 74 FurtherReading 76

1.7HowParasitesAlterTheirHosts 77

1.7.1AlterationsofHostCells 78

1.7.2IntrusionintotheHormonalSystemoftheHost 79

1.7.3ChangingtheBehaviorofHosts 82

1.7.3.1IncreaseintheTransmissionofParasitesbyBloodsucking Vectors 83

1.7.3.2IncreaseinTransmissionThroughtheFoodChain 83

1.7.3.3IntroductionintotheFoodChain 88

1.7.3.4ChangesinHabitatPreference 92 FurtherReading 93

2BiologyofParasiticProtozoa 95

RichardLuciusandCraigW.Roberts

2.1Introduction 97 FurtherReading 98

2.2Metamonada 99

2.2.1 Giardialamblia99 FurtherReading 102

2.3Parabasala 102

2.3.1 Trichomonasvaginalis103

2.3.2 Tritrichomonasfoetus106 FurtherReading 106

2.4Amoebozoa 107

2.4.1 Entamoebahistolytica108

2.4.2 Entamoebadispar114

2.4.3Other Entamoeba Species 114

2.4.4FurtherIntestinalAmoebae 115

2.4.5 Acanthamoeba115 FurtherReading 116

2.5Euglenozoa 117

2.5.1CellBiologyandGenome 118

2.5.2Phylogeny 121

2.5.3 Trypanosomabrucei121

2.5.4 Trypanosomacongolense131

2.5.5 Trypanosomavivax132

2.5.6 Trypanosomaevansi133

2.5.7 Trypanosomaequiperdum133

2.5.8 Trypanosomacruzi134

2.5.9 Leishmania141

2.5.9.1Development 142

2.5.9.2Morphology 143

2.5.9.3Leishmaniosis 143

2.5.9.4CellandImmuneBiology 143

2.5.10 Leishmaniatropica148

2.5.11 Leishmaniadonovani150

2.5.12 Leishmaniabraziliensis and Leishmaniamexicana151 FurtherReading 151

2.6Alveolata 153

2.6.1Apicomplexa 155

2.6.1.1Development 155

2.6.1.2Morphology 157

2.6.1.3CellBiology 160

2.6.2Coccidea 165

2.6.2.1 Cryptosporidiumparvum166

2.6.2.2 Eimeria169

2.6.2.3 Eimeriatenella174

2.6.2.4 Eimeriabovis175

2.6.2.5 Isospora and Cyclospora175

2.6.2.6 Toxoplasmagondii176

2.6.2.7 Neosporacaninum186

2.6.2.8 Sarcocystis187

2.6.3Haematozoea 190

2.6.3.1 Plasmodium190

2.6.3.2 Plasmodiumvivax,aCausativeAgentofTertianMalaria 199

2.6.3.3 Plasmodiumovale,aCausativeAgentofTertianMalaria 200

2.6.3.4 Plasmodiummalariae,theCausativeAgentofQuartan Malaria 200

2.6.3.5 Plasmodiumfalciparum,theCausativeAgentofMalignantTertian MalariaorMalariatropica 201

2.6.3.6 Plasmodium speciesofMonkeys,Rodents,andBirds 210

2.6.4Piroplasms 211

2.6.4.1 Babesia211

2.6.4.2 Theileria214

2.6.5Ciliophora 218

2.6.5.1 Balantidiumcoli219

2.6.5.2 Ichthyophthiriusmultifiliis219

2.6.5.3 Trichodina221

FurtherReading 222

3ParasiticWorms 225 BrigitteLoos-FrankandRichardK.Grencis

3.1Platyhelminths 228

3.1.1Digenea 230

3.1.1.1Development 230

3.1.1.2Morphology 232

3.1.1.3Adults 234

3.1.1.4SystematicsandEvolutionaryHistory 237

3.1.1.5 Schistosoma238

3.1.1.6 Leucochloridiumparadoxum248

3.1.1.7 Diplostomumspathaceum248

3.1.1.8 Fasciolahepatica251

3.1.1.9 Opisthorchisfelineus254

3.1.1.10 Paragonimuswestermani257

3.1.1.11 Dicrocoeliumdendriticum259 FurtherReading 262

3.1.2Cestoda 263

3.1.2.1Development 265

3.1.2.2EvolutionandOriginofLifeCycles 266

3.1.2.3Morphology 266

3.1.2.4Genome 269

3.1.2.5Diphyllobothriidea 269

3.1.2.6 Mesocestoides272

3.1.2.7Cyclophyllidea 272

3.1.2.8 Monieziaexpansa273

3.1.2.9 Hymenolepisdiminuta274

3.1.2.10 Rodentolepisnana (Hymenolepisnana) 275

3.1.2.11Taeniidae 277

3.1.2.12 Taeniasaginata281

3.1.2.13 Taeniasolium282

3.1.2.14 Taeniaasiatica282

3.1.2.15 Hydatigerataeniaeformis283

3.1.2.16 Echinococcus283

3.1.2.17 Echinococcusgranulosus283

3.1.2.18 Echinococcusmultilocularis285

3.1.2.19 Echinococcusvogeli and Echinococcusoligarthrus286 FurtherReading 287

3.2Acanthocephala 288 FurtherReading 293

3.3Nematoda 294

3.3.1Development 295

3.3.2Morphology 297

3.3.3Dorylaimea 300

3.3.3.1 Trichinellaspiralis300

3.3.3.2 Trichuristrichiura305

3.3.4Chromadorea 306

3.3.4.1 Strongyloidesstercoralis306

3.3.4.2 Ancylostomaduodenale and Necatoramericanus308

3.3.4.3 Angiostrongyluscantonensis311

3.3.4.4 Haemonchuscontortus312

3.3.4.5 Dictyocaulusviviparus315

3.3.4.6 Ascarislumbricoides315

3.3.4.7 Ascarissuum318

3.3.4.8 Toxocaracanis318

3.3.4.9 Anisakissimplex and Anisakis spp. 320

3.3.4.10 Dracunculusmedinensis321

3.3.4.11 Enterobiusvermicularis323

3.3.4.12Filariae 325

3.3.4.13 Wuchereriabancrofti and Brugiamalayi326

3.3.4.14 Onchocercavolvulus330

3.3.4.15 Loaloa and Dirofilariaimmitis334

3.3.4.16RodentModelsofFilariosis 334 FurtherReading 335

4Arthropods 337

BrigitteLoos-FrankandRichardP.Lane

4.1Introduction 338

4.1.1VectorConcepts 340

4.1.2ImpactofBloodfeeding 343 FurtherReading 343

4.2Acari–MitesandTicks 344

4.2.1Morphology 346

4.2.2Development 347

4.2.3Anactinotrichida(= Parasitiformes) 347

4.2.3.1Mesostigmata 347

4.2.3.2 Dermanyssusgallinae348

4.2.3.3 Varroadestructor348

4.2.3.4Metastigmata(= IxodidaorIxodoidea,Ticks) 350

4.2.3.5Development 353

4.2.3.6TickBitesandSaliva 353

4.2.3.7Ixodidae–HardTicks 354

4.2.3.8Argasidae(SoftTicks) 358

4.2.3.9Tick-BorneDiseases 359

4.2.4Actinotrichida(= Acariformes) 361

4.2.4.1Prostigmata = Actinedida = Trombidiformes 362

4.2.4.2Trombiculidae–HarvestMites,Chiggers 363

4.2.4.3Astigmata = Acaridida = Sarcoptiformes 364 FurtherReading 365

4.3Crustacea 366

4.3.1 Argulusfoliaceus367

4.3.2 Sacculinacarcini368 FurtherReading 370

4.4Insecta 370

4.4.1Phthiraptera–Lice 374

4.4.2“Mallophaga”–ChewingLice 375

X Contents

4.4.3Anoplura–SuckingLice 375

4.4.3.1 Pediculushumanuscapitis377

4.4.3.2 Pediculushumanushumanus378

4.4.3.3 Pthiruspubis378

4.4.3.4DiseaseTransmissionbyLice 379

4.4.4Heteroptera–TrueBugs 380

4.4.5Triatominae–KissingBugs 380

4.4.6Cimicidae–Bedbugs 382

4.4.6.1 Cimexlectularius383

4.4.7Siphonaptera–Fleas 384

4.4.7.1BiologyandDevelopment 384

4.4.7.2Morphology 385

4.4.7.3 Pulexirritans387

4.4.7.4 Ctenocephalides:CatandDogFleas 387

4.4.7.5 Tungapenetrans –Jiggers 388

4.4.7.6DiseaseTransmissionbyFleas 388

4.4.8Diptera–Flies 390

4.4.8.1LowerDiptera 390

4.4.8.2Ceratopogonidae–BitingMidges,No-see-ums,Punkies 391

4.4.8.3DiseaseTransmission 393

4.4.8.4Culicidae–Mosquitoes 394

4.4.8.5DiseaseTransmission 398

4.4.8.6Simuliidae–Blackflies 401

4.4.8.7Phlebotominae–Sandflies 404

4.4.8.8Brachycera 408

4.4.8.9Tabanidae–HorseFlies 408

4.4.8.10Muscidae–HouseandStableFlies 410

4.4.8.11Calliphoridae–Blowflies,Screwworms 413

4.4.8.12Oestridae–BotorWarbleFlies 413

4.4.8.13Glossinidae–TsetseFlies 415

4.4.8.14Hippoboscidae,Nycteribiidae,Streblidae–LouseFlies,Kedsand BatFlies 418 FurtherReading 419

AnswerstoTestQuestions 423

Chapter1 423

Chapter2 426

Chapter3 429

Chapter4 431

Index 435

Preface

Parasitismisaspecializedwayoflife,pursuedbyorganismsthathaveevolvedto thriveattheexpenseofalivinghost.Therefore,inabroadsense,allpathogenslike viruses,bacteria,oreukaryoticinfectiousagentsareparasitesandthussharemany commonfeatures.However,theyalsohaveimportantdifferences.Forexample, virusesandbacteriaaregeneticallylesscomplexandemploydifferentstrategies forexploitingahost,leadingtodifferentdiseasesyndromes.Asaconsequence, differentscientificfieldshaveemerged,ofwhichthedisciplineofparasitologyis onethatdealswitheukaryoticpathogens,namely,protozoa,worms,andarthropods.Parasites,inthisnarrowersense,areahugeburdentomankind,withbillions ofinfectedpeople,mainlyintropicaldevelopingcountrieswithrelativelypoor hygiene.Alongwiththeirmedicalandveterinaryimportance,parasiteshavea fascinatingbiology,whichisthethemeofthisbook. TheBiologyofParasites is basedonanearlierGermanbook(Lucius&Loos-Frank(2008),SpringerVerlag, Heidelberg),whichhasbeenextendedandupdatedbythecurrentteamofauthors.

Thelivinghostisaveryparticularniche;itisnotaneutralplaceatall.Parasites areinvolvedinaconstantstrugglewiththeirhosts,whostrivetoridthemselves oftheunwantedcompany,deployingallsortsofmechanismsagainstthem.These rangefromdefensivebehaviortotheeffectormoleculesandcellsofacomplex immunesystem.Inspiteofsuchdefenses,anextraordinarynumberofanimals haveadoptedparasitismasamodeoflife;somespecialistsbelievethat >50%of animalspeciesareparasitesorhaveatleastaparasiticphaseintheirlifecycle. Itseemsthattheparasiticlifestyleissorewardingthatithasbeenworththe greateffortparasiteshavemadetodevelopmostintriguingmeansoflocating theirhosts,survivewithinoronthem,produceoffspring,andensurethatthenext generationreachesanewhost.Toexploitahost,parasitesmaychangetheirmorphologybeyondallrecognition:theymaytrickandcheatbydisguisingthemselves ormanipulatetheirhost’scellularpathwaysoreventheirbehavior.Becauseof theseextraordinary,bizarre,orseemingly“otherworldly”abilities,parasiteshave alwaysfascinatedbiologistsandcapturedtheattentionofthegeneralpublic.

Theantagonisticrelationshipbetweenpathogensandtheirhostsdrivestheevolutionofbothadversariesinaprofoundmanner.Thisarmsracehasaffectedthe evolutionofsomeofthemostimportantprocessesoflife,forexample,sexual reproductionandtheimmunesystem.Italsoshapedthegenomesofbothparties

toadegreethatwehaveonlyrecentlydiscovered.Indeed,newmoleculartechniquesdevelopedinpastfewdecadeshaveopenedanextraordinaryrangeofperspectivesontheinterplaybetweeneukaryoticparasitesandtheirhosts.Genome projectshavecastlightonthepeculiaritiesofparasitegenomes.Forexample, wehavelearnedthatmanyprotozoansandwormshaveundergoneareductive evolutionintheirgenomes,especiallywithregardtothosefunctionstheyhave appropriatedfromtheirhost,whileotherareashavebeenexpanded,suchasthose neededforthemanipulationofthehost.Thisexplosioningenomicknowledgehas alsoprovideduswiththetoolstodiscoveranddescribepreciselyparasite-specific metabolicpathways.Ithasalsofacilitatedthedissectionofmolecularmechanisms usedbyparasitestodetecthostcues,invadehostcells,orcopewithimmuneeffectormechanisms.Thisinformationhasalreadyallowedandwillhopefullyfurther allowustodesignspecificmeasuresagainstparasitesandtheirvectors,ranging fromstrategiestopreventinfection,suchasvaccinesandpesticides,todrugdevelopment.However,itisnotthesolegoalofparasitologiststofightdiseases,as worthyasthatis,buttounderstandtheintricaciesoftheparasiticlifestyleandto putthemintoabroaderbiologicalcontext.Thisgreatlycontributestoourwider understandingofkeybiologicalprocesses,suchasevolution,ecology,andgenerationofbiodiversity.Lastbutnotleast,thesimplewonderandawetheextraordinarybiologyofparasitesinstillsinusmakestheirstudyworthwhileinitsown right.

Thisbookisdesignedtoprovideadvancedinformationtostudentsofbiology, medicine,orveterinarymedicineandtointerestedlaypersons.Anintroductory chapterongeneralparasitology,addressingcrosscuttingtopicsofparasitology, isfollowedbyspecificchaptersonthebiologyofprotozoanparasites,parasitic worms,andparasiticarthropods.Thefocusisonparasitesofmedicalorveterinaryimportance,asthesearebestknownfromintensiveresearchandareofthe widestinterest,althoughwealsohighlightparasiteswithinterestingbiological adaptationstoemphasizethosetraitsmosttypicaloftheparasiticlifestyle.To beconcise,wediscussparticularspeciesasrepresentativesoftheirtaxon,while relatedparasitesarebrieflymentionedortreatedintabularform.Inevitably, thebookcannotcovertheentirefieldofparasitology.Itdoesnotgivedetailed treatmentofthetherapyorcontrolofparasiticinfections,parasiteecology, orevolutionaryparasitology.Likewise,wehavesparinglymentionedmarine parasitesorparasitoidsandtheirinterestingbiologies.Tocovercutting-edge topics,wehaveinvitedthreerenownedguestauthorstocontributeconcise informationfromtheirfieldofresearch,namely,JohnBoothroyd(parasite–host interplayof Toxoplasma),KaiMatuschewski(vaccinedevelopmentagainstthe malariaparasite Plasmodium),andNinaPapavasiliou(newdevelopmentsin trypanosomeresearch).

Wearethankfultomanycolleaguesfromdifferentfieldsofparasitologyand beyondfortheirhelpfuldiscussions.Wethankspecificallythosewhoprovided imagesofparasitesorillustrativeresearchdata,inparticularOliverMeckesand NicoleOttawafrom eyeofscience forfascinatingelectronmicroscopepictures, Prof.EgbertTannichforimagesofamoebae,andDr.HeikoBellmannforphotos

Preface XIII ofarthropods.WegratefullyacknowledgethepermissionoftheDepartmentsof ParasitologyofUniversityofHohenheimandofHumboldtUniversitytoutlize picturesfromtheirarchives.Thelifecyclesandotherdrawingsarebasedonthe painstakingworkofFlaviaWolf,Dr.J.Gelnar,andHannaZeckau,whichisgratefullyacknowledged.Aheartfeltthank-yougoestoChristineNowotnyforhermost professionalhelpwiththeorganizationofthemanuscriptandillustrations.This workwouldnothavebeenpossiblewithoutthecontinuoussupportofDr.Gregor CicchettiandDr.AndreasSendtkoandtheirteamfromthepublisherWiley-VCH, whichisgratefullyacknowledged.

September2016

RichardLucius

Berlin

GeneralAspectsofParasiteBiology

RichardLuciusandRobertPoulin

1.1IntroductiontoParasitologyandItsTerminology2

1.1.1Parasites2

1.1.2TypesofInteractionsBetweenDifferentSpecies5

1.1.2.1MutualisticRelationships5

1.1.2.2AntagonisticRelationships6

1.1.3DifferentFormsofParasitism10

1.1.4ParasitesandHosts11

1.1.5ModesofTransmission16 FurtherReading17

1.2WhatIsUniqueAboutParasites?18

1.2.1AVeryPeculiarHabitat:TheHost18

1.2.2SpecificMorphologicalandPhysiologicalAdaptations22

1.2.3FlexibleStrategiesofReproduction27 FurtherReading29

1.3TheImpactofParasitesonHostIndividualsandHostPopulations30 FurtherReading37

1.4Parasite–HostCoevolution38

1.4.1MainFeaturesofCoevolution38

1.4.2RoleofAllelesinCoevolution42

1.4.3RarenessIsanAdvantage45

1.4.4MalariaasanExampleofCoevolution46 FurtherReading50

1.5InfluenceofParasitesonMateChoice51 FurtherReading57

1.6ImmunobiologyofParasites58

1.6.1DefenseMechanismsofHosts60

1.6.1.1InnateImmuneResponses(InnateImmunity)60

1.6.1.2AcquiredImmuneResponses(AdaptiveImmunity)62

TheBiologyofParasites, FirstEdition.RichardLucius,BrigitteLoos-Frank,RichardP.Lane,RobertPoulin, CraigW.Roberts,andRichardK.Grencis.

©2017Wiley-VCHVerlagGmbH&Co.KGaA.Published2017byWiley-VCHVerlagGmbH&Co.KGaA.

2

1GeneralAspectsofParasiteBiology

1.6.1.3ScenariosofDefenseReactionsAgainstParasites63

1.6.1.4Immunopathology67

1.6.2ImmuneEvasion68

1.6.3ParasitesasOpportunisticPathogens72

1.6.4HygieneHypothesis:DoParasitesHaveaGoodSide?74 FurtherReading76

1.7HowParasitesAlterTheirHosts77

1.7.1AlterationsofHostCells78

1.7.2IntrusionintotheHormonalSystemoftheHost79

1.7.3ChangingtheBehaviorofHosts82

1.7.3.1IncreaseintheTransmissionofParasitesby BloodsuckingVectors83

1.7.3.2IncreaseinTransmissionThroughtheFoodChain83

1.7.3.3IntroductionintotheFoodChain88

1.7.3.4ChangesinHabitatPreference92 FurtherReading93

1.1 IntroductiontoParasitologyandItsTerminology

1.1.1 Parasites

Parasitesareorganismswhichliveinoronanotherorganism,drawingsustenancefromthehostandcausingitharm. Theseincludeanimals,plants,fungi, bacteria,andviruses,whichliveashost-dependentguests.Parasitismisoneof themostsuccessfulandwidespreadwaysoflife.Someauthorsestimatethatmore than50%ofalleukaryoticorganismsareparasitic,orhaveatleastoneparasitic phaseduringtheirlifecycle.Thereisnocompletebiodiversityinventorytoverify thisassumption;itdoesstandtoreason,however,giventhefactthatparasiteslive inoronalmosteverymulticellularanimal,andmanyhostspeciesareinfectedwith severalparasitespeciesspecificallyadaptedtothem.Someofthemostimportant humanparasitesarelistedinTable1.1.

ThetermparasiteoriginatedinAncientGreece.ItisderivedfromtheGreek word“parasitos”(Greek pará = on,at,beside; sítos = food).Thenameparasitewas firstusedtodescribetheofficialswhoparticipatedinsacrificialmealsonbehalf ofthegeneralpublicandwinedanddinedatpublicexpense.Itwaslaterapplied tominionswhoingratiatedthemselveswiththerich,payingthemcompliments andpracticingbuffoonerytogainentrytobanquetswheretheywouldsnatch somefood.

1.1IntroductiontoParasitologyandItsTerminology 3

Table1.1 Occurrenceanddistributionofthemorecommonhumanparasites.

ParasiteInfectedpeople(inmillions)Distribution

Giardialamblia >200Worldwide Trichomonasvaginalis 173Worldwide Entamoebahistolytica 500*Worldwideinwarmclimates

Trypanosomabrucei 0.01Sub-SaharanAfrica(“Tsetse Belt”)

Trypanosomacruzi 7CentralandSouthAmerica

Leishmania spp.2Near + MiddleEast,Asia,Africa, CentralandSouthAmerica

Toxoplasmagondii 1500Worldwide Plasmodium spp. >200Africa,Asia,CentralandSouth America

Paragonimus sp.20Africa,Asia,SouthAmerica

Schistosoma sp. >200Asia,Africa,SouthAmerica

Hymenolepisnana 75worldwide

Taeniasaginata 77Worldwide

Trichuristrichiura 902Worldwideinwarmclimates

Strongyloidesstercoralis 70Worldwide

Enterobiusvermicularis 200Worldwide Ascarislumbricoides 1273Worldwide Ancylostomaduodenale and Necatoramericanus 900Worldwideinwarmclimates Onchocercavolvulus 17Sub-SaharanAfrica,Centraland SouthAmerica

Wuchereriabancrofti 107Worldwideinthetropics

Source: Compiledfromvariousauthors.

*manyofthoseasymptomticorinfectedwiththemorphologicallyidentical Entamoebadispar .

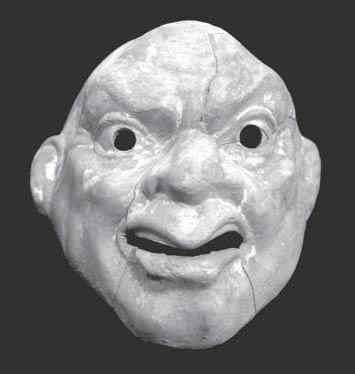

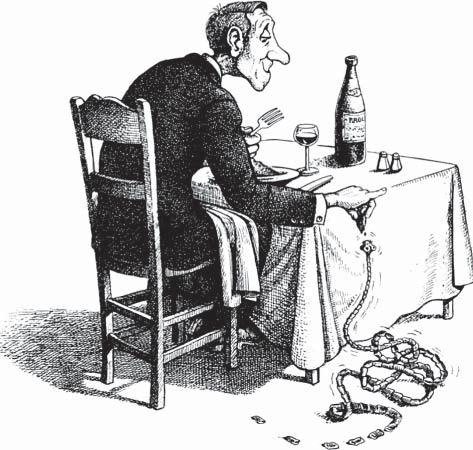

Theresultwasacharacterfigure,atypeofHarlequin,whohadafixedroleto playintheGreekcomedyofclassicalantiquity(Figure1.1).Later,“parasitus”also becameanintegralpartofsociallifeinRomanantiquity.Italsoreappearedin EuropeantheaterinpiecessuchasFriedrichSchiller’s“DerParasit.”Intheseventeenthcentury,botanistswerealreadydescribingparasiticplantssuchasmistletoe asparasites;inhis1735standardwork“Systemanaturae,”Linnaeusfirstusedthe term“specieparasitica”fortapewormsinitsmodernbiologicalsense.

Thedelimitationoftheterm“parasite”toorganismswhichprofitfroma heterospecific hostisveryimportantforthedefinitionitself.Interactionsbetween individualsofthesamespeciesarethusexcluded,evenifthebenefitsofsuchinteractionsareveryoftenunequallydistributedinthecoloniesofsocialinsectsand nakedmolerats,forinstance,orinhumansocieties.Asaresult,theinteraction betweenparentsandtheiroffspringdoesnotfallunderthiscategory,althoughthe directorindirectmannerinwhichtheoffspringfeedfromtheirparentorganism canattimesbereminiscentofparasitism.

Figure1.1 Parasitosmask,aminiatureofatheatermaskofGreekcomedy;terracotta, around100B.C.(FromMyrine(AsiaMinor);antiquitiescollectionoftheBerlinStateMuseums.Image:CourtesyofThomasSchmid-Dankward.)

Theprincipleofoneside(theparasite)takingadvantageoftheother(thehost) appliestoviruses,allpathogenicmicroorganisms,andmulticellularparasites alike.Thisiswhyweoftenfindthatnocleardistinctionismadebetween prokaryoticandeukaryoticparasites.Withregardto parasites, weusuallydonot differentiatebetweenviruses,bacteria,andfungiontheonehandandanimal parasitesontheother;wetendtoseeonlythecommonparasiticlifestyle.Even moleculestowhichafunctionintheorganismcannotbeassignedaresometimes describedasparasitic,suchasprions,forexample,thecausativeagentofspongiformencephalopathy,orapparentlyfunctionless“selfish”DNAplasmidsthatare presentinthegenomeofmanyplants.Manybiologistsareoftheopinionthat onlyparasiticprotozoa,parasiticworms(helminths),andparasiticarthropodsare parasitesinthestrictsenseoftheterm.Parasitology,asafield,isconcernedonly withthosegroups,whileviruses,bacteria,fungi,andparasiticplantsaredealt withbyotherdisciplines.Thisrestrictionclearlyhamperscooperationwithother disciplines,somethingthatseemsantiquatedintoday’smodernbiology,where alloflife’sprocessesaretracedbacktoDNA;itisgratifyingthattheboundaries haverelaxedinrecentyears.However,eukaryoticparasitesaredistinguished fromvirusesandbacteriabytheircomparativelyhighercomplexity,which impliesslowerreproductionandlessgeneticflexibility.Thesetraitstypicallydrive eukaryoticparasitestoestablishlong-standingconnectionswiththeirhosts, usingstrategiesdifferentfromthe“hit-and-run”strategiesusedbymanyviruses andbacteria.Forthesereasons,andforthesakeofclarityandtradition,only parasitesinthestrictersenseoftheterm,thatis,parasiticprotozoa,helminths, andparasiticarthropodsaredealtwithinthisbook.

1.1.2

TypesofInteractionsBetweenDifferentSpecies

Thecoexistenceofdifferentspeciesoforganismsinvolvesinteractionsamong themthattakemanydifferentformsinwhichthebenefitsandcostsareoftenvery unevenlydistributed.Bothpartnersbenefitfrommutualisticrelationships,while inantagonisticrelationshipstheadvantagelieswithonlyoneside.However,a directrelationshipbetweentwospeciesisseldomcompletelyneutral.Different typesofinteractionsarenotalwayseasytodistinguish,suchthattransitions betweenthemareoftenfluidandthedifferencessubtle.Thespectrumofthe partnershipsbetweendifferentorganismscanbebestillustratedbytheuseof concreteexamples.

1.1.2.1 MutualisticRelationships

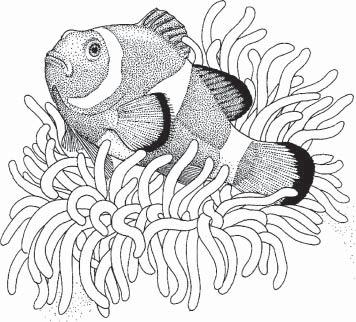

Ifdifferentpartnersrelyontheircoexistenceandarelimitedintheirviabilityor evennonviablewhenseparated,thiscloseassociationisdescribedasa symbiosis (Greek: sym = together, bíos = life).Forexample,Lichens–acombinationoffungi andphotosyntheticallyactivealgae–canonlycolonizecompletelynewhabitatsinthiscombinedform.Anotherexampleisthepartnershipoftermiteswith cellulose-digestingprotozoa,whichliveintheintestinalblindsacsofthehosts. Themetabolitesoftheprotozoacomplementthehosts’ratherunbalanceddiet. Whenthetwopartnersbenefitfromcoexistencewithoutlosingtheabilitytolive independently,itisknownas mutualism.Aclosemutualisticrelationshipexists betweenclownfish(anemonefish)andseaanemones:thefishcangainprotectionfrompredatorsbysnugglingintothetentaclesoftheseaanemoneswithoutbeingattackedbythelatter’spoisonousstingingcells(Figure1.2)andalways returnstotheanemonewhendangerthreatens.Theseaanemonebenefitsinturn

Figure1.2 Aclownfishinthetentaclesofaseaanemone.Thepartnersformamutualistic symbiosis,buttheycanalsosurviveindependently.(Image:RichardOrr,courtesyofRandom HousePublishers,Munich.)

Figure1.3 Thepearlfish Carapus (syn. Fierasfer ) acus livesinthewaterlungsofseacucumbers.(EditedfromOcheG.(1966)“TheWorldofParasites”,Springer-VerlagHeidelberg.)

fromthefoodremnantsofthefish.AnotherexampleofalessintimatemutualisticassociationistheinteractionbetweenCapebuffaloandthecattleegret. Whilegrazing,abuffaloflushesoutinsects,whicharethensnappedupbythe egrets–andthedanger-sensitivebirdswarnthebuffalobyflyingupwhenthey spotbigcatsapproaching.

Commensalism describesafeedingrelationship,inwhichonepartnerbenefits withoutprovidinganyreciprocalbenefitsnorimposinganycosttotheother.The commensaldrawssustenancefromthehost’swastematerialsorfromthecomponentsofthehost’sfood,whichareofnovaluetoit.Theflagellatesthatresidein theanalcanalsofarthropodsprovideanexample,becausetheseareareasofthe digestivesystemwherenomorefoodabsorptiontakesplace.

However,therearesymbioticrelationshipsinwhichahostismerelyusedasa livingplace.Thisinvolvesorganismssettlingontheexternalsurfacesofadifferent species(e.g.,barnaclesoncrabsandshellfish),oreveninsidethehost’sbody.One exampleofthisisthepearlfish,amemberofthecodfamily,whichcangrowtoa lengthofapproximately20cm.Thefishlivesinthewaterlungsofseacucumbers intowhichitskillfullywriggles,pointedtailfirst(Figure1.3).Pearlfishonlyleave theirhoststoforageandreproduce.

1.1.2.2

AntagonisticRelationships

Whenaguestorganismextractsnutrientsfromitshost–andthehostincursa costfromtherelationship–itisknownas parasitism.Parasitescanalsocause damagingeffectssuchasinjury,inflammation,toxicmetabolite,andotherfactors,

Figure1.4 Coexistenceofatypicalparasitewithitshost.Tapewormsdrawnourishment fromtheirhostandexploitthehostinthelongterm–theyare,however,onlymoderately pathogenic.(DeboucheàOreillebyClaudeSerre©EditionsGlénat2016) andresultinreducedevolutionaryfitnessofthehost,eveniftheeffectsareonly slight.Adulttapewormsmayberegardedastypicalexampleshere:theyabsorb nutrientsfromthedigestedfoodinthesmallintestineofthehost,therebyharming thehost,butdonotattackitstissues.Thehostisthusweakenedalittle,butnot killed,andtheparasitelivesoftheinterestwithouttouchingitscapital.Claude Serreexpressesallthesequalitiesveryaptlyinhiscartoon(Figure1.4).Parasites areusuallysmallerandmorenumerousthantheirhost,whereaspredatorsare largerandlessnumerousthantheirprey.Whenoneparasitesettlesonanother,we callthis hyperparasitism. Nosemamonorchis,forexample,asingle-cellorganism ofthephylumMicrospora,parasitizesthedigenean Monorchisparvus,whichis itselfaparasiteoffish.

Weusuallyexpectanintimate,physicalrelationshipbetweenparasiteand host.Intimatecontactlikethisexistsinendoparasitismand(inmanycases) ectoparasitism.Therearealsoformsofparasitisminwhichthephysicalcontact betweenthepartnersislessintimate,wheretheparasitedoesnotexistasa pathogen,butexploitsthehostinotherways.Theexploitationofinteractions betweenmembersofsocialorganismsisdefinedas socialparasitism.Inthe caseofsocialinsectssuchasants,theinteractionsofahostspeciesareexploited byaparasiticspecies.Thespectrumofsocialparasitismrangesfromfoodtheft toslaveryandthetargetedassassinationofthequeen,whichisthenreplaced bythequeenofaparasiticspecies.Onespecificformofsocialparasitismisthe exploitationofadifferentspeciestorearone’sownoffspring,whichisknown as broodparasitism.Awell-knownrepresentativeofthebroodparasitesisthe

Figure1.5 Broodparasitism:Ayoungcuckooisfedbyawarbler.(Image:Courtesyof OldrichMikulica.)

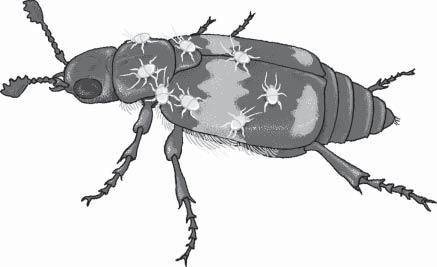

Figure1.6 Phoresy:Miteslatchontoasextonbeetle,“hitchingaride”tothenearestcarrion.(DrawingfromaphotobyFrankKöhler.)

cuckoo(Cuculuscanorus).Thefemaleofthespecieslaysitseggsinthenests ofsmallersongbirdstohavethemraiseitsyoungones(Figure1.5).Thecuckoo bee’sbehaviorisverysimilar.Cuckoobeesaccountfor125ofatotalof547 speciesofbeesinGermany–afactthatsaysmuchforthesuccessofthisform ofparasitism.Notonlyfoodbutalsofunctionssuchastransportationcanbe exploitedbyparasites.Forinstance,somemitesandcertainnematodeslatchon toinsectsfortransportation.Inthistypeofparasitism, phoresy,thecarriersare referredtoastransporthosts(Figure1.6).

Parasitoidism occurswhenthedeathofthehostisalmostinevitablefollowingparasiticexploitation.Onetypicalexampleofthisinvolvesichneumonwasps, whichlaytheireggsoncaterpillars.Whentheyoungwaspshatch,theyfeedon thehost’stissues(Figure1.7).Theparasiticwasplarvaefirstdevourthebodyfat, andtheneatthemuscletissueandfinallykilltheirhostsbyconsumingtheneural

Figure1.7 Parasitoidism:Aparasiticwaspofthegenus Ichneumon laysitseggsinacaterpillar.(Fromaphotoin“TheAnimalKingdom,”courtesyofMarshallCavendishBooksLtd.)

tissue.Thelarvaefinallybreakoutofthecaterpillarandpupate.Aparasitoidlike thisattacksthecapital,ratherthanlivingoftheinterest.However,itdoesexploit thehostforarelativelylongperiodoftimeandonlykillsitwhentheparasitoidis finishedwithit.

Theinteractionbetweenparasitoidsandtheirhostshowssomesimilarities to predator–preyrelationships,forexample,betweenalionandwildebeest (Figure1.8).However,whereastheparasitoidonlykillsitshostaftereatingmost ofit,thepreyisimmediatelykilledbythepredatorandtheneaten.Inaddition, predatorsaretypicallylargerthantheirprey,andconsumemorethanonepreyin theirlifetime,twofeaturesthatseparatethemfromparasites.

Figure1.8 Predator–preyrelationship:Alionattacksawildebeest.(Image:IngoGerlach, www.tierphoto.de.)

1.1.3

DifferentFormsofParasitism

Organisms,whichcanliveasparasites,butarenotnecessarilydependenton theparasiticmodeofliferepresent facultativeparasites.Oneexampleisthe bloodsuckingkissingbug, Triatomainfestans. Itcanalsoliveasapredatorby suckingoutthehemolymphofsmallerinsects. Obligateparasites haveno alternativeotherthantheirwayoflife.Inthecaseofsomeorganisms,onlyone sexlivesparasitically.Inmosquitoes,forinstance,onlythefemalesneedamealof bloodtoproduceeggs;themalefeedsonthesapofplants. Permanentparasites areparasiticinallstagesoftheirdevelopment,while temporaryparasites spend onlycertainphasesoftheirlifeinahost.

An ectoparasite attachestotheskinorotherexternalsurfaces(e.g.,thegills)of itshost,whereitsubsistsonhairorfeathers,feedsonskin,orsucksbloodortissue fluidsubstance.Includedamongectoparasitesarenumerous temporaryparasites (sometimescalledmicropredators),whichonlyseekouttheirhoststofeed (e.g.,bloodsuckingmosquitoes),andmany permanentparasites thatremainin constantcontactwiththeirhosts(e.g.,lice,orthemonogeneansparasiticonfish). Parasitesthatliveinsidetheirhostsareknownas endoparasites.Thewormslivinginthegutlumenofvertebratesillustratethesimplestformofendoparasitism. Thedifferencebetweenrottingsubstancesintheoutsideworldandthecontentsof thedigestivetractisnotparticularlysignificantanditisrelativelycommontofind organismsthathaveadaptedtoendoparasitismofthistype.Oneexampleofthese residentsofthegutlumenisthenematode Strongyloidesstercoralis,thelifecycle ofwhichillustratesthatithastheoptionofeitherthefree-livingortheparasitic modesoflife.Otherendoparasiteseitherliveinorgans(suchasthegreatliverfluke Fasciolahepatica),livefreelyinthebloodoftheirhosts(suchas Trypanosoma brucei),orinhabitbodytissue(suchasthefilarialnematode Onchocercavolvulus). Intracellularparasites induceverypronouncedchangesinthehostcell:using thesehighlyspecificmechanisms,theseparasites(e.g., Leishmania and Plasmodium)invadehostcells,reorganizethemtofittheirownneeds,andexploitthis extremeecologicalnicheduetoamultitudeofadaptations.

Asanadaptationtotheirmodesoflife,manyparasiteshaveevolvedcomplex lifecycles,whichincludeswitchingbetweenmultiplehostsandsexualand asexualreproduction(Figure1.9).Inthesimplestformsofparasitism,only onehostisexploited;theseparasitesasreferredtoas monoxenous (Greek mónos = single, xénos = foreign).Inthiscase,transmissionfromonehosttothe nexttakesplaceamongmembersofthesamehostspecies,andisreferredto as directtransmission.Bycontrast, indirecttransmission occurswhenthe parasiteswitchesbetweentwoormorehostspecies.Theseparasitesareknown as heteroxenous (hetero = differing);theircomplexcyclesrequiretwoorthree, sometimesevenfour,hostspecies,dependingontheparasite.Byswitchinghosts fromonestageoftheirlifecycletothenext,heteroxenousparasitesachieve greateroverallfitness,ortransmissionefficiency,thantheywouldbyutilizing asinglehostpergeneration.Forexample,theuseofbloodsuckingmosquitoes

Life cycles

Host

MonoxenousDiheteroxenousTriheteroxenous

Figure1.9 Lifecyclesofparasites. Left : Monoxenouscyclewithonehost,for example, Ascarislumbricoides Center :Heteroxenouscyclewithfinalandintermediate

hosts,forexample, Trypanosomabrucei. Right:Heteroxenouscyclewithfinalhostand twointermediatehosts,forexample, Dicrocoeliumdendriticum.

as vectors,thatis,carriersoftheparasitebetweenvertebratehosts,results inamuchhigherlevelofefficiencyinthetransmissionofmalariathanhas beenmeasuredinhighlycontagiousviraldiseasestransmittedthroughdirect transmission.Theevolutionofcomplexlifecyclesfromwhatoriginallywere simpleoneshasoccurredinseveralunrelatedparasitelineages,rangingfrom microorganismstomulticellularparasites,throughthestepwiseadditionofa newhostwheneverthiswasfavoredbynaturalselection.

Modesofreproductionvarygreatlyamongparasites,andmanyparasite speciescanswitchfromonereproductionmodetoanotherduringtheirlife cycle.Whenaparasitealternatesbetweensexualandasexualreproduction,this isknownas metagenesis.TheApicomplexa,alternatingbetweenschizogony (asexual),gamogony(sexual),andsporogony(asexual),isagoodexampleof metagenesis.Switchingfromsexualtoasexualreproduction(i.e.,parthenogenesis = virginbirth)isalsoseeninsomeintestinalnematodes,suchas Strongyloides stercoralis,forinstance;itslifecycleillustratesachangebetweengenerations ofparthenogeneticallyreproducingparasiticfemalesandfree-livingsexually reproducingworms.Amongsexuallyreproducingparasites,hermaphroditismis acommonstrategy,inwhichindividualparasitespossessbothmaleandfemale reproductiveorgans.Thisisthecaseamongplatyhelminthssuchastapeworms andflukes(exceptthebloodflukes,orschistosomes).Hermaphroditeshavethe greatadvantageofbeingcapableofreproductioneveniftheycannotfindanother memberoftheirspeciesinahost,byself-fertilization.

1.1.4

ParasitesandHosts

Inheteroxenouslifecyclesadistinctionisfirstmadebetweenthefinalhost andintermediatehost.Sexualreproductiontakesplaceinthe final(definitive) host.Someconfusioninterminologycanoccasionallyarisewiththisdefinition;

1GeneralAspectsofParasiteBiology

forplasmodia,forexample,themoreimportanthostfromananthropocentric viewpointisthehumanbeing.However,fertilizationtakesplaceinthemosquito, andhencetheinsectmustberegardedasthedefinitivehost.Anotherpartof thelifecycleofparasitestakesplaceinthe intermediatehost,wheresignificant developmentalprocessesorasexualreproductionoccur.Thisisthedistinguishing factorbetweenintermediatehostsandpuretransmissionagents(vectors),which transmitpathogensmechanically(e.g.,throughthestyletsofbloodsucking insects).Severalintermediatehostsmaybeexploitedinsuccessionduringa lifecycle,andtheseareknownasfirstorsecondintermediatehosts.Insome lifecycles,ahostindividualplaystherolesofthefinalandintermediatehosts simultaneously,asobservedinthecaseofthenematode Trichinellaspiralis. Thetrichinareproducessexuallyinthegutofitshost(finalhostfunction),and thenformsrestingstagesinacompletelydifferentcompartment,themusclecell (intermediatehostfunction).Inmanycases,transmissionfromintermediateto definitivehostsoccursbypredationoftheformerbythelatter.Thelarvalstages ofsomeparasitescanalsobetransmittedfromsmallertolargerintermediate hoststhroughthefoodchain,withoutanysignificantmorphologicalchanges occurring.Suchhosts,knownas paratenichosts,accumulatethelarvae,and theirinsertioninthelifecyclefacilitatestransmissionoftheselarvaetothe definitivehost.

Ateachstageoftheirlifecycle,manyparasitesareoptimallyadaptedtoaparticularhostspecies,whichmayrepresenttheirmainhostinfat,thatis,theone theyhavecoevolvedwithforalongtime.Onthishost,growthandreproduction areoptimalandtheparasiteenjoysalonglifecycle.Bycontrast,livingconditions areworsefortheparasiteinalternativehostinfatthatnonethelessallowthesurvivaloftheparasite,withtheresultthatthesehostsplayalesssignificantrolein theperpetuationofthelifecycle.Thesealternativehosts,however,mayserveas reservoirhosts infatandbeofmajorepidemiologicalimportance–whencontrolmeasureshavebeenusedonthemainhost,forexample,chemotherapyon farmanimals,theparasitecycleinwildreservoirhostscannotbeeradicatedand areinfectionmaytakeplaceviathesehosts.Bycontrast,parasitedevelopment stagescansometimesoccurina wronghost ordead-endhost,wherenofurther transmissioncantakeplace(e.g., Toxoplasmagondii inhumans).

Oneindispensablebasisfortheestablishmentofahost–parasiterelationship isthe susceptibility ofthehost.Susceptibilityisessentiallydeterminedbythe behavioral,physiological,andmorphologicalcharacteristicsofthehost,and alsobythehost’sinnateandadaptiveimmuneresponses.Withinapopulation,therefore,thehostgenotypeoftendeterminestheindividualdegreeof susceptibility–certainhostsmaythusbepredisposedforinfection.Acquired characteristics,suchasphysicalconditionorage,canalsoaffectanindividual host’ssusceptibilitytoparasites.

Host resistance toaparasiticinfectioncandependontheimmuneresponses ofthehost.Thisbecomesclearwhenahostonlybecomessusceptiblewhenelementsoftheimmunesystemaredisabled.Forexample, Aotus monkeys–usedas experimentalanimalsinmalariavaccineresearch–canonlybereliablyinfected

1.1IntroductiontoParasitologyandItsTerminology 13 aftersplenectomy.However,resistancecanalsobedefinedbybiochemicalfactors. T.brucei, forinstance,iskilledbyaproteininhumanserum,whichisassociated withhigh-densitylipoproteins. Immunity isthetermusedwhenapastinfection leavesbehindprotectiveimmuneresponses.Inthecaseofparasiticinfections, anexistinginfectionoftenprovidesimmunitytofurtherinfections.A concomitantimmunity (premunition)likethispermitsalready-establishedparasitesto survive,butleadstotheeliminationofnewinfectivestagestryingtoinfectthe host.Thissituationcancauseparasitedensitytobedownregulatedtoatolerablelevelforthehost.Hostswithdefectiveimmunesystemsareoftenmoresusceptibletoparasites;thesehostsmayconsequentlybecolonizedby opportunisticpathogens,whicharepresentonlyinlowdensitiesornotatallinimmunocompetentindividuals.Suchopportunisticparasiticinfectionsarecommonin AIDSpatients–andinmanycases,theseinfectionsarethedirectcauseofdeath. Examplesofthisarethefrequentoccurrenceof Toxoplasmagondii, Cryptosporidiumparvum,and Leishmania speciesinAIDSpatientsandotherimmunocompromisedpersons.

Parasitescanspecializeinvaryingdegreesinthewaytheyexploittheirhosts. Thedegreeofspecializationisexpressedinthe hostspecificity,whichcombines thenumberofhostspeciesthatcanbeusedatanystageofthelifecycle,andthe relativeprevalenceandintensityofinfectionbytheparasiteonthesehosts.For instance,parasitesthatcaninfectonlyonehostspeciesorinfectafewhostspecies butachievehighprevalenceandintensityononlyoneofthesespecieshaveahigh degreeofhostspecificity(“narrowhostspecificity”).Featherlice(Mallophaga,see Section4.4.2)areoneexampleofhighlyhostspecificparasites.Theyarenotonly adaptedtoaparticularhostspeciesomit–theycanonlycolonizecertainparts ofthehostbird’sbody(Figure1.10).Otherhighlyhost-specificparasitesinclude omitthelarvalstagesofdigeneans(flukes)fortheirmolluscanfirstintermediate host.Bycontrast,parasiteswithwidehostspecificitycancolonizeawiderangeof hostssuccessfully,andoftenachievehighprevalenceorintensityofinfectionon manyofthesehosts.Forexample,certainstagesof Trypanosomacruzi and Toxoplasmagondii exploitalmostallmammalsashostsandinvadealmostalltypes ofthehosts’nucleatedcells.Relyingonthe hostrange combinedwithinformationonprevalenceandintensityofinfectionasameasureofspecializationcan be,however,misleading.Letusconsidertworelatedparasitespecies,AandB, eachusingfourhostspeciesandachievingalmostequalprevalenceandintensityinalltheirhosts.However,thehostsofparasiteAbelongtodistantlyrelated families,whereasthoseofparasiteBallbelongtothesamegenus.Therefore,we caneasilyarguethatparasiteBdisplayshigherhostspecificitythanA,sinceits hostsarerestrictedtoanarrowerphylogeneticspectrum.Hostspecificityisthe outcomeofcolonizationofnewhostsandadaptationtothesehostsoverevolutionarytime,andthemorehost-specificparasitesarethosethatcannotmake thelargejumpnecessarytocolonizeanimalspeciesnotcloselyrelatedtotheir mainhost.Inthiscontext,severalparasiteshavemadethe“jump”fromwildor domesticanimalstohumans;diseasescausedbyparasitestransmittedbetween vertebratesandhumansundernaturalconditionsarereferredtoas zoonoses (e.g.,

Figure1.10 DistributionofvariousMallophagaspeciesonanIbis(Ibisfalcinellus), anexampleofhighspecificityforparticularhabitatsonahostindividual.(a) Ibidoecusbisignatus.(b) Menoponplegradis

(c) Colpocephalum and Ferribia species.(d) Esthiopterumraphidium.(FromDogiel,V.A. (1963) AllgemeineParasitologie(GeneralParasitology),VEBGustavFischerVerlag,Jena.)

T.spiralis,transmissionbetweenpigsandhumans;and Taeniasaginata,transmissionbetweencattleandhumans).

Theestablishmentofparasitesinasusceptiblehostresultsinan infection.In strictcontext,thistermappliesonlyifanincreaseinthenumberofparasites occursbyreplicationoftheoriginalparasitewithinthehost,asinthecaseofprotozoa.However,thetermisnowwidelyusedinthecaseofhelminths(worms) orarthropodparasites,too,whereonlyonematureparasitedevelopsfromeach infectivelarva.Thetermformerlyusedforthesegroupsis“infestation.”Theperiod duringwhichdiagnosticallyrelevantparasitestagesappear,suchasplasmodiain theblood,isknownas patency.Theperiodfrominfectiontopatencyiscalled prepatency ortheprepatentperiod,whiletheperioduntiltheonsetofthefirst symptomsisknownasthe incubationperiod.Forhelminthparasites,prepatency correspondstotheperiodfrominitialinfectionofthehosttotheonsetofeggproduction,wheneggsstartappearinginthefecesorurineofthehost;patencythen correspondstotheadultlifeoftheworm,fromtheonsetofeggproductionto itsdeath.Inaccordancewithaninternationalagreement,theinfectionandthe resultingdiseaseareknownbythenameoftheparasitewiththesuffix-osis,for example,toxoplasmosis.However,formanydiseasesthesuffix-iasisisinwideuse.

Thetermusedwhenaninfectionwiththesamepathogenoccursaftera parasitosishashealedis reinfection.Aninfectioncontractedinadditionto

1.1IntroductiontoParasitologyandItsTerminology 15 anexistingparasitosisandcausedbythesamespeciesofparasiteisknownas superinfection.Simultaneousinfectionswithmultiplepathogenspeciesare knownas mixedinfections.Bothsuperinfectionsandmixedinfectionshave consequencesforhostwelfare,astheoverallharmfuleffectonthehostmay dependonadditiveorsynergisticeffectsbetweenthedifferentinfections.Ifa hostinfectsitselfwithstagesthatoriginatefromitsowninfection,itiscalled autoinfection;anexampleofthisisautoinfectionwiththepinworm Enterobius vermicularis.

The harmfuleffect whichthehostsuffersfromparasitesmayhavedifferent causesandmanifestations,andismeasuredindifferentwaysbydifferentgroups ofresearchers.Asameasureoftheimpairmentcausedbyparasites,evolutionarybiologistsusethereductioninthehost’s geneticfitness attributable toinfection.Thisdecreaseinhostfitnessisreferredtoasthe virulence ofthe parasite,andisquantifiedastherelativedifferencebetweenthereproductive capacityoftheinfectedhostcomparedtowhatreproductionitcouldachieve withouttheinfection.Intheassessmentofmedicalimportance,theparameters morbidity (incidenceofdisease)and mortality (incidenceofdeath)areused.A quantificationisdeterminedbycalculatingthe disability-adjustedlifeyears (DALYs);thisisaWHOindexintowhichupto140individualparameters flowfortheassessmentofadisease.Finally,theharmfuleffectofparasitic infectionsinlivestockiscalculatedbydeterminingthelossofproductivity(e.g., milkyieldincowsandwoolproductioninsheep)andthecostofinfection control.

Ataphysiologicallevel,parasiticinfectionsusuallyhaveapathogenicimpact oreffect;thisisgenerallydescribedas pathogenicity andthedefinedmolecular factorsthatareimportantinthiscontextarecalled pathogenicityfactors.The amoebaporeproteinproducedby Entamoebahistolytica isapathogenicityfactor, sinceitplaysacrucialroleduringtissueinvasion.Thetermusedforthequantitativeexpressionofpathogenicityis virulence (Latin virulentus = fullofpoison), whichwasoriginallyameansofassessingapathogen’sdegreeofaggressiveness. Unfortunately,thesametermisusedbyevolutionarybiologiststorefertotheparasite’seffectonhostgeneticfitness.Fromaphysiologicalperspective,thehostis thereforenotonlyharmedbyfooddeprivation–thedestructionofcellsortissues throughtheactionoftoxicmetabolicproductsandimmuneresponsesthatharm thehost’sowntissue(immunopathology)alsocausedamage.Itusedtobethought thatphylogeneticallyancientparasite–hostrelationshipsshouldbecharacterized byarelativelylowpathogenicity,sinceparasiteswhichonlyminimallyharmtheir hostsmaypersistlongeroverthecourseofevolution.However,followingboth theoreticalworkandexperimentalstudieswithfast-evolvingpathogens,itisnow acceptedthatthepathogenicity(orvirulenceinitsevolutionarysense)ofparasitescanincreaseoverthecourseofevolution.Indeed,underarangeofcircumstances,naturalselectioncanfavoraggressiveexploitationofthehost,resultingin highparasitereplicationandtransmissionrates,attheexpenseoflong-termhost survival.

1.1.5

ModesofTransmission

Duetothedifferentvarietiesofparasiticorganisms,modesoftransmissionare verydiverse.Thesimplestformoftransmissionis bydirectcontact,forexample, throughcontactwiththeskin,suchasinmitesorlice.Onespecialcaseofcontactinfectionis sexualtransmission,asinthecaseofinfectionscausedby Trichomonasvaginalis and Trypanosomaequiperdum. Manylifecyclesofparasitesarebasedon oralinfection, thatis,theintake ofinfectivestagesviathemouth.Intakecanoccurviathefoodchainandfoodstuff–aprocessknownas alimentaryinfection,orinecologicalterms, trophic transmission.Someofthesecyclesarebasedonapredator–preyrelationship betweentheintermediateanddefinitivehosts(e.g.,catchingofmicebythe finalhost,thefox,whichsimultaneouslyingestsmetacestodesof Echinococcus multilocularis,thefoxtapeworm).Transmissionfromanintermediatehostto aplant-eatingdefinitivehostrequiresaslightadjustment;here,theparasite stagesleavetheintermediatehosttoencystonfoodplants(Fasciolahepatica: encystmentonwetlandplants).Infectionby fecal-oralcontamination occurs wheninfectivestagesderivedfromfeces(e.g.,amoebacysts,coccidiaoocysts, andnematodeeggs)areingestedorally;diversemediasuchascontaminated water,food,andair(airbornetransmission)canbeusedastransmissionmedia. Sincetransmissionisusuallylefttochanceinfecal-oralinfections,largenumbers ofinfectivestagesaretypicallyproducedbyparasitesusingthisroute(e.g., severalbillion Cryptosporidiumparvum oocystsperkilogramofcattledung). Infectionsoccurringthroughotherbodyorificessuchasthenose,ear,eye, rectum,genitalapertures,andwoundsarelesscommon.Oneimportantdecisive factorinwhetherornotinfectivestagesaresuccessfulintransmissionistheir persistence intheexternalenvironment,thatis,theinfectivestages’resistanceto environmentalinfluencessuchasextremesoftemperature,desiccation,salinity, andtheeffectsofchemicalexposure.

Percutaneousinfection orskinpenetrationplaysanimportantrole,particularlyinhelminthinfections.Inthesecases,infectivestagesinthesoilorwater activelyboreintotheskinofthefinalorintermediatehost(e.g.,thecercariaeof schistosomesandotherdigeneans,theinfectivelarvaeofthehookworm Ancylostomaduodenale).

Onehighlytargetedandthereforeextremelyefficientmodeoftransmission occursthroughtheuseof vectors (Latin vectus = carried)inthelifecycleofmany parasites,mostlythoselivinginthebloodofvertebrates.Thismaybepurely mechanical,suchasthetransmissionof Trypanosomaequinum viathelancets oftabanidflies.Morecommonly,however,thetransmittingorganismshavea functionashosts,forinstancebloodsuckingarthropodsthatingesttheparasites withtheirbloodmeal,withpartoftheparasite’sdevelopmentoccurringinside thevector(e.g.,malariaparasitesinsidethemosquito).Otherbloodsucking animalscanalsoserveasvectorsofparasites,includingleechesandvampirebats.

Manyoftheaforementionedtransmissionmodes(directcontact,sexualtransmission,fecal-oralcontamination,transmissionbyvectors)enabletransmission