Danish Classical Music

Udgivelsesserien Danish Classical Music (DCM) har til formål at tilgængeliggøre dansk musikalsk kulturarv i pålidelige og gennemarbejdede praktisk -videnskabelige nodeeditioner for musikere og forskere i ind - og udland. Således er ambitionen at overtage stafetten fra Dansk Center for Musikudgivelse, som opererede som et forskningscenter under Det Kgl. Bibliotek, 2009 – 2019. Centeret udgav praktisk- videnskabelige editioner af høj filologisk kvalitet, og siden lukningen af centeret er denne opgave ikke blevet varetaget – men behovet er ikke blevet mindre.

Mens Dansk Center for Musikudgivelse fungerede som et center med ansatte medarbejdere er forholdene for det nye DCM anderledes: Her er tale om selvstændige og individuelt finansierede projekter under DCM - paraplyen. Derfor er der ikke blevet udarbejdet et nyt sæt redaktionelle retningslinjer – i stedet videreføres de retningslinjer, som blev formuleret af Dansk Center for Musikudgivelse. De eneste ændringer fra retningslinjerne er layoutmæssige, og så er der i DCM - udgivelserne tilføjet en kort biografisk introduktion til komponisten.

De redaktionelle retningslinjer sikrer udgivelsernes høje og konsistente editionsfilologiske niveau og grundindstillingen til udgivelsesarbejdet kan sammenfattes i nogle få, centrale punkter.

Om “praktisk - videnskabelige editioner” Med begrebet “praktisk - videnskabelige editioner” sigtes der til, at udgivelserne skal være praktisk anvendelige for musikere, uden at musikerne nødvendigvis skal forholde sig til redaktørens arbejde og filologiske overvejelser. Derfor er selve nodesiden “ren” og uden fodnoter eller lignende. Samtidig er udgivelserne videnskabelige, idet interesserede læsere kan finde den nødvendige information om det editionsfilologiske arbejde i tekstdele placeret før og efter nodedelen: Før nodedelen bringes en introduktion til værket, dets tilblivelses – og receptionshistorie samt generelle kommentarer til det filologiske arbejde (eksempelvis nogle særlige udfordringer eller valg); efter nodedelen følger en grundig kildebeskrivelse og en oversigt over redaktionelle ændringer, deres begrundelse i kilderne samt information om varianter.

Om redaktørens rolle

Som James Grier skriver i bogen The Critical Editing of Music fra 1996, så er al editionsfilologisk arbejde også et fortolkningsarbejde, ideelt set baseret på grundige, kritiske og historisk forankrede studier af kildematerialet. Idéen om at den videnskabelige edition videregiver den “eneste rigtige” version af værket er en fiktion: Ofte vil redaktører komme frem til varierende udlægninger af et værk, og ofte kan der argumenteres lige godt for den ene læsning som den anden. Det er derfor vigtigt at bevæggrunden for de enkelte valg er tydeliggjort i oversigten over redaktionelle rettelser.

I serien undgås såkaldte “eklektiske” editioner, en sammenblanding af forskellige kilder, der kan resultere i en version af værket, der aldrig har eksisteret fra komponistens hånd. Der bestemmes derfor altid en hovedkilde, som editionen er baseret på, mens varianter kan bruges som hjemmel ved rettelser af klare fejl.

Thomas Husted Kirkegaard, ph.d.

Danish Classical Music

The publication series Danish Classical Music (DCM) aims to make Danish musical heritage accessible for musicians and researchers in Denmark and abroad by providing reliable and meticulous practical – scholarly music editions. The ambition is thus to take over the baton from the Danish Centre for Music Publication which operated as a research centre under the Royal Library from 2009 to 2019. The centre published practical – scholarly editions of high philological quality, and since the closure of the centre, this task has not been undertaken –but the need has not diminished.

While the Danish Centre for Music Publication functioned as a centre with dedicated employees, the conditions for the new DCM are different: it comprises of independent projects funded individually under the DCM framework. Therefore, a new set of editorial guidelines has not been developed – instead, the guidelines formulated by the Danish Centre for Music Publication are being sustained. The only changes to the guidelines relate to layout, and in DCM publications a brief biographical introduction of the composer is added.

The editorial guidelines ensure a high and consistent level of philological quality in the publications, and the fundamental editorial approach can be summarized in a few key points.

On “Practical -Scholarly Editions”

The term “practical -scholarly editions” refers to the aim of making the publications practically useful for musicians without requiring them to engage directly with the editor’s work and philological considerations. The sheet music is therefore “clean”, without footnotes or similar additions. At the same time, the publications are scholarly in nature, as interested readers can find the necessary information about the philological work in sections placed before and after the sheet music: Prior to the sheet music, there is an introduction to the work, its genesis and reception history, as well as general comments on the philological work (such as specific challenges or choices). After the sheet music, a thorough description of sources and an overview of editorial changes, their justification based on the sources, and information about variants are presented.

On the Role of the Editor

As James Grier writes in his book The Critical Editing of Music from 1996, all philological work is also an act of interpretation, ideally based on thorough, critical, and historically grounded studies of the source material. The notion that the scholarly edition presents the “only correct” version of a work is a fiction: Editors often arrive at varying interpretations of a piece, and equally compelling arguments can often be made for different readings. Therefore, it is important to clarify the rationale behind each choice in the overview of editorial revisions.

The series avoids so - called “eclectic” editions, which involve a mixture of different sources and may result in a version of the work that never existed in the composer’s hand. Therefore, a primary source is always determined as the basis for the edition, while variants can be used as evidence for correcting clear errors.

Thomas Husted Kirkegaard,

Ph.D

Biografi

Hilda Sehested blev den 27. april 1858 født ind i en adelig familie på herregården Broholm på Fyn og døde 15. april 1936 i København.

Som del af den almene dannelse, som kvinder fra Sehesteds socialklasse var pålagt, blev hun som barn undervist i klaver og musikteori. Sehested gik ikke på konservatoriet, men hun begyndte at modtage privatundervisning i klaver hos komponisten C.F.E. Horneman som 15-årig i 1873. Fra 1886 studerede hun komposition privat hos Orla Rosenhoff.

Sehested udtrykte en trang til at frigøre sig fra sin hjemegn og sine selskabelige pligter på Broholm og flyttede i 1892 til København. Der var hun tættere på musiklivet i hovedstaden og ligesindede, aspirerende musikere og komponister.

Sehested blev forlovet med arkæologen Henry Petersen, som dog døde kort før deres planlagte bryllup i 1896. Efter dette stoppede hun både med undervisningen hos Rosenhoff og med at komponere. I de efterfølgende år forsøgte hun at finde en ny vej i livet og uddannede sig som organist. Hun fik sit afgangsbevis i 1899, men vides ikke at have haft embede som organist efterfølgende.

Først i 1900 vendte hun tilbage til sin gamle musikalske omgangskreds og begyndte igen at komponere og udgive musik. I 1903 udgav hun værkerne Klaversonate i As-dur og Intermezzi for violin, cello og klaver, og året efter begyndte hun at komponere for blæseinstrumenter. I 1905 skrev hun Suite für Cornet in B und Klavier, der i 1915 blev bearbejdet til Suite for Kornet og Orkester Klaversonatens kompositionsstil blev af hendes læremester Orla Rosenhoff beskrevet som “hyper-romantisk,” og han mente, at den bar præg af hendes kærlighed til Wagner og Schumann.

I 1913-1914 skrev hun sin første og eneste opera Agnete og Havmanden, der havde tekst af forfatteren Sophus Michaëlis, og som blev antaget til opførelse på Det Kongelige Teater. Grundet 1. verdenskrig og den materialemangel, krigen medførte, måtte opsætningen aflyses.

I 1910’erne havde hun opnået anerkendelse som komponist, og hendes værker blev opført af flere solister og ensembler. Orkesterstykkerne Lygtemænd og Mosekonen Brygger blev begge opført ved en kompositionskoncert i 1915, hvor Politikens anmelder skrev, at Sehested viste sig som en “virkelig dygtig Dame.” 1

Sehesteds forkærlighed for at komponere musik for blæseinstrumenter fortsatte, og hun skrev i midten af 1920’erne de to større værker for basun Morceau pathétique pour trombone avec accompagnement de piano i 1924 og Course des athlètes du Nord. Morceau symphonique pour trombone avec orchestra ou piano i 1925. I de sidste ti år frem til sin død i 1936 indstillede Hilda Sehested komponistkarrieren.

Maria Claustad

Biography

Hilda Sehested was born on 27 April 1858 into a noble family at the Broholm manor on Funen and died on 15 April 1936 in Copenhagen.

As part of the general education that was required of women of Sehested’s social class, she was taught piano and music theory as a child. Sehested did not attend the conservatory, but began receiving private piano lessons from the composer C.F.E. Horneman as a 15-year-old in 1873. From 1886 she studied composition privately with Orla Rosenhoff.

Sehested expressed a desire to free herself from her home environment and her social duties at Broholm and in 1892 moved to Copenhagen. There she was closer to the musical life of the capital and like-minded, aspiring musicians and composers.

Sehested became engaged to the archaeologist Henry Petersen, who, however, died shortly before their planned wedding in 1896. Following this, she stopped both her lessons with Rosenhoff and composing. In the following years, she tried to find a new path in life and trained as an organist. She obtained her graduation certificate in 1899, but is not known to have held office as an organist afterwards.

It was not until 1900 that she returned to her old musical circle and began to compose and publish music again. In 1903 she published the works Piano Sonata in A Major and Intermezzi for Violin, Cello and Piano, and the following year began composing for wind instruments. In 1905 she wrote Suite for Cornet in Bb und Piano, which in 1915 was adapted into the Suite for Cornet and Orchestra The compositional style of the piano sonata was described by her teacher Orla Rosenhoff as “hyper-romantic,” believing that it was influenced by her love of Wagner and Schumann.

In 1913 – 1914 she wrote her first and only opera Agnete og Havmanden, to a text by the author Sophus Michaëlis, and which was accepted for performance at the Royal Theatre. Due to the 1st World War and the shortage of materials caused by the war, the staging had to be cancelled.

By the 1910s, she had achieved recognition as a composer, and her works were performed by several soloists and ensembles. The orchestral pieces Lygtemænd and Mosekonen Brygger were both performed at a composition concert in 1915, where Politiken’s reviewer wrote that Sehested proved to be a “really talented lady.” 1

Sehested’s penchant for composing music for wind instruments continued, and in the mid-1920s she wrote the two major works for trombone Morceau pathétique pour trombone avec accompaniment de piano in 1924 and Course des athlètes du Nord. Morceau symphonique pour trombone avec orchestra ou piano in 1925.

In the last ten years before her death in 1936, Hilda Sehested suspended her career as a composer.

Maria Claustad

1 “Gusch”, Politiken 26.3.1915.

Forord

Det vides ikke, præcist hvornår Hilda Sehested komponerede Mosekonen brygger. Men vi ved, at værket blev komponeret i en klaverversion senest i 1911 – om orkesterversionen er komponeret på baggrund af klaversatsen eller omvendt, er uvist. Vi ved også, at Sehested var fascineret af den tåge, der fandtes på Broholm, hendes barndomshjem, og at denne formentlig har fungeret som en form for inspirationskilde til værket, hvor mosekonens brygdamp lydliggøres. 1

Første gang, Mosekonen brygger nævnes i dagspressen, er i 1911, hvor den berømte russiske violinist Issay Mitnitzky sammen med pianist Alexander Stoffregen afholdt en koncert i Borgerforeningen den 26. marts. 2 Til koncerten fremførtes både violin- og klaverstykker – bl.a. af Paganini, Chopin og altså også af Sehested. Stoffregen opførte her en klaverversion af værket, som kan have været identisk med Sehesteds klaverbearbejdelse Sommerminder (se nedenfor). 3

Den 25. marts 1915 afholdt Hilda Sehested en kompositionskoncert i Studenterforeningens Store Sal. Til denne koncert blev bl.a. hendes Suite for Kornet og Orkester opført, ligesom de to orkesterværker betegnet Miniature for Orkester (“Lygtemænd” og “Mosekonen brygger”) var på programmet. I forbindelse med koncerten fulgte Hilda Sehested interesseret indstuderingsarbejdet, som blev ledet af dirigent Peder Gram:

Næsten betydningsfuldere end Koncerten selv, var for mig alt det, der gik forud – Orkesterprøverne først og fremmest. Hvad man kan lære af saadan 3 Prøver! [...] Og hvor uhyre interessant at følge min unge begavede Dirigent, Peder Grams Arbejde med at faa de vigtige Replikker frem og alle Farver lagt i de retter Planer. Hans Mening om mine Orkesterarbejder var: at Suiten, som jeg instrumenterede for et godt halvt Aar siden, det var i Sommer før Ferien, var for massivt instrumenteret; Rhapsodien, som jeg skrev nogle Maaneder senere, har han kaldt “et ganske ulasteligt Partitur” – Lygtemænd, som er det allersidste Arbejde, sagde han, var det bedste, men dertil krævedes et ‘Elite Orkester’ […] En anden Ting af Betydning for mig var Orkestrets Holdning til min Musik [...]. Og jo længere de arbejdede, jo mere Interesse mærkede jeg hos dem. “Skriv bare noget mere for os, det ligger saa vi kan blæse det” – har de sagt, og mere til. Han, der blæste “Engelsk Horn”, har meldt sit Besøg herud med Instrumentet, han er rent begejstret som hans Soloer laa [...]. Og Kornetten, den dygtige unge Tycho Mohr, har meldt sig med en anden Blæser herud paa Torsdag, for at blæse for mig en brillant Solo, jeg har ytret Ønske om at høre for at lære nogle Tricks deraf. Alt dette viser jo, at jeg maa være i mit rette Element naar jeg skriver for Orkester, og jeg gaar ganske rolig videre. Bladene er jeg tilfreds med, fordi Kritikken er holdt i en høflig og saglig Tone. Jeg vidste, det hele var et meget voveligt Foretagende, og jeg gøs for at Anmelderne skulle blive enige om at “smadre mig”. [...] Og dersom nu Kritikken havde givet mig saadan en “Damebehandling”, saa ville jeg heller ikke kunne gøre mig gældende blandt de andre Komponister. [...] Ja, det har virkelig været betydningsfulde Dage! 4

Preface

It is not known exactly when Hilda Sehested composed Mosekonen brygger (Mist Over the Meadow). But we do know that the work was composed in a piano version no later than 1911 – whether the orchestral version was composed based on the piano movement or vice versa is unknown. We also know that Sehested was fascinated by the fog that existed on Broholm, her childhood home, and that this probably served as a kind of source of inspiration for the work, where the marsh-crone’s brew is made audible. 1

The first time Mosekonen brygger is mentioned in the daily press is in 1911, when the famous Russian violinist Issay Mitnitzky, together with pianist Alexander Stoffregen, held a concert at the Borgerforeningen (Citizen’s Society) on 26 March. 2 The concert featured both violin and piano pieces – including Paganini, Chopin and Sehested, amongst others. Stoffregen performed a piano version of the work here, which may have been identical to Sehested’s piano arrangement Sommerminder (see below). 3

On March 25, 1915, Hilda Sehested held a composition concert in the Great Hall of the Student Association. For this concert, among other things, her Suite for Cornet and Orchestra was performed, as were the two orchestral works titled Miniature for Orchestra (“Lygtemænd” and “Mosekonen brygger”) on the program. In connection with the concert, Hilda Sehested followed the rehearsals, which were led by conductor Peder Gram, with interest:

Almost more significant for me than the concert itself was everything that preceded it – the orchestral rehearsals first and foremost. What one can learn from 3 such rehearsals! [...] And how incredibly interesting it was to follow my young gifted conductor, Peder Gram’s work in bringing out the important lines and placing all the colours on the right planes. His opinion of my orchestral works was: that the Suite, which I orchestrated a good half a year ago, that was in the summer before the holidays, was too heavily orchestrated; the Rhapsody, which I wrote a few months later, he called “a completely impeccable score” – Lygtemænd, which is the very last work, he said, was the best, but it required an ‘elite orchestra’ […]

Another thing of importance to me was the orchestra’s attitude towards my music [...]. And the longer they worked, the more interest I felt from them. “Just write something more for us, it’s ready for us to play” – they said, and more. He who played the “English horn” has announced his visit here with the instrument, he is absolutely thrilled with the way his solos were [...]. And the cornet, the talented young Tycho Mohr, has announced his visit here with another wind player on Thursday, to play a brilliant solo for me, I have expressed a desire to hear it in order to learn some tricks from it. All this shows that I must be in my right element when I write for the orchestra, and I am moving ahead quite calmly. I am satisfied with the magazines because the criticism is kept in a polite and objective tone. I knew that the whole thing was a very daring undertaking, and I shuddered lest the reviewers would agree to “smash me”. [...] And if the criticism had given me a “ladylike treatment”, then I would not have been able

1 Lisbeth Ahlgren Jensen, Hilda Sehested og Nancy Dalberg, Danske komponister, bind 4 (København: Multivers, 2019), 67.

2 Svendborg Avis. Sydfyns Tidende 22.3.1911, s. 3; Svendborg Avis. Sydfyns Tidende 24.3.1911, s. 3.

3 Det er også muligt, at orkesterversionen er en orkestrering af klaverversionen; om sidstnævnte har fået sit navn Sommerminder allerede tidligt i værkets liv eller først ved udgivelsen i Nordens Musik, vides ikke.

4 Brev fra Hilda Sehested, 29.3.1915, i Hannibal Sehesteds Arkiv, Rigsarkivet; citeret i Ahlgren Jensen, Hilda Sehested og Nancy Dalberg, 63-65.

1 Lisbeth Ahlgren Jensen, Hilda Sehested og Nancy Dalberg, Danske komponister, vol. 4 (Copenhagen: Multivers, 2019), 67 In Danish folklore the marsh-crone (mosekonen) is a woman that lives at the bottom of a marsh and thick fog is often referred to as her ‘brew’.

2 Svendborg Avis. Sydfyns Tidende 22 Mar. 1911, p. 3; Svendborg Avis. Sydfyns Tidende 24 Mar. 1911, p. 3.

3 It is also possible that the orchestral version is an orchestration of the piano version; whether the latter was given its name Sommerminder early in the work’s life or only upon its publication in Nordens Musik is not known.

Koncerten fik fine anmeldelser, men den tunge orkestrering, som Peder Gram noterer sig, blev også bemærket af Berlingske Tidendes anmelder, der skrev:

Man fik i aftes Indtryk af Komponistens gode teoretiske Grundlag og Evne til at gribe en Stemning. [...] De to Miniaturer for Orkester indeholdt virkelige brugbare Indfald, der dog ikke fastholdes med tilstrækkelig Konsekvens. Det mystiske Sommernatskogleri var momentvis godt anslaaet i “Mosekonen brygger” og der fandtes lovende Tilløb i “Lygtemænd”, der for øvrigt maatte gentages, men i intet af disse Stykker kom den ledende Idé rigtig frem, og de led begge under en for massiv Orkestration. 5

Mosekonen brygger blev i 1921 udgivet i musiktidsskriftet Nordens Musik i en klaverbearbejdelse (under titlen Sommerminder), og i 1929 indspilledes den fulde orkesterversion til radiobrug. 6 Udgivelsen i Nordens Musik er hidtil den eneste udgivelse af Mosekonen brygger, og med denne udgivelse trykkes således orkesterversionen for første gang.

Asmus Mehul Mejdal Larsen

to make my mark among the other composers either. [...] Yes, these have really been significant days! 4

The concert received fine reviews, but the heavy orchestration, which Peder Gram notes, was also noted by the reviewer of Berlingske Tidende, who wrote:

Last night one got an impression of the composer’s good theoretical foundation and ability to grasp a mood. [...] The two Miniatures for Orchestra contained really useful ideas, which, however, were not maintained with sufficient consistency. The mysterious summer-night foraging, was at times well-executed in “Mosekonen brygger” and there were promising approaches in “Lygtemænd”, which had to be repeated, but in none of these pieces did a leading idea really emerge, and they both suffered from too heavy an orchestration. 5

Mosekonen brygger was published in 1921 in the music journal Nordens Musik in a piano arrangement (under the title Sommerminder (Summer Memories)), and in 1929 the full orchestral version was recorded for radio use. 6 The publication in Nordens Musik is to date the only publication of Mosekonen brygger, and with this publication the orchestral version is thus printed for the first time.

Asmus Mehul Mejdal Larsen

5 Den til Forsendelse med de Kongelige Brevposter privilegerede Berlingske Politiske og Avertissementstidende 26.03.1915, 2. udg., s. 3; citeret i Ahlgren Jensen, Hilda Sehested og Nancy Dalberg, 66-67.

6 Hilda Sehested, Lygtemænd, redigeret af Bendt Viinholdt Nielsen (København: Edition·S, 2024), vi.

4 Letter from Hilda Sehested, 29.Mar.1915, in Hannibal Sehested’s Archive, Rigsarkivet; cited in Ahlgren Jensen, Hilda Sehested og Nancy Dalberg, 63 – 65.

5 Den til Forsendelse med de Kongelige Brevposter privilegerede Berlingske Politiske og Avertissementstidende 26.Mar.1915, 2nd ed., p. 3; cited in Ahlgren Jensen, Hilda Sehested og Nancy Dalberg, 66 – 67.

6 Hilda Sehested, Lygtemænd, edited by Bendt Viinholdt Nielsen (Copenhagen: Edition·S, 2024), vi.

Critical Commentary

Description of Sources

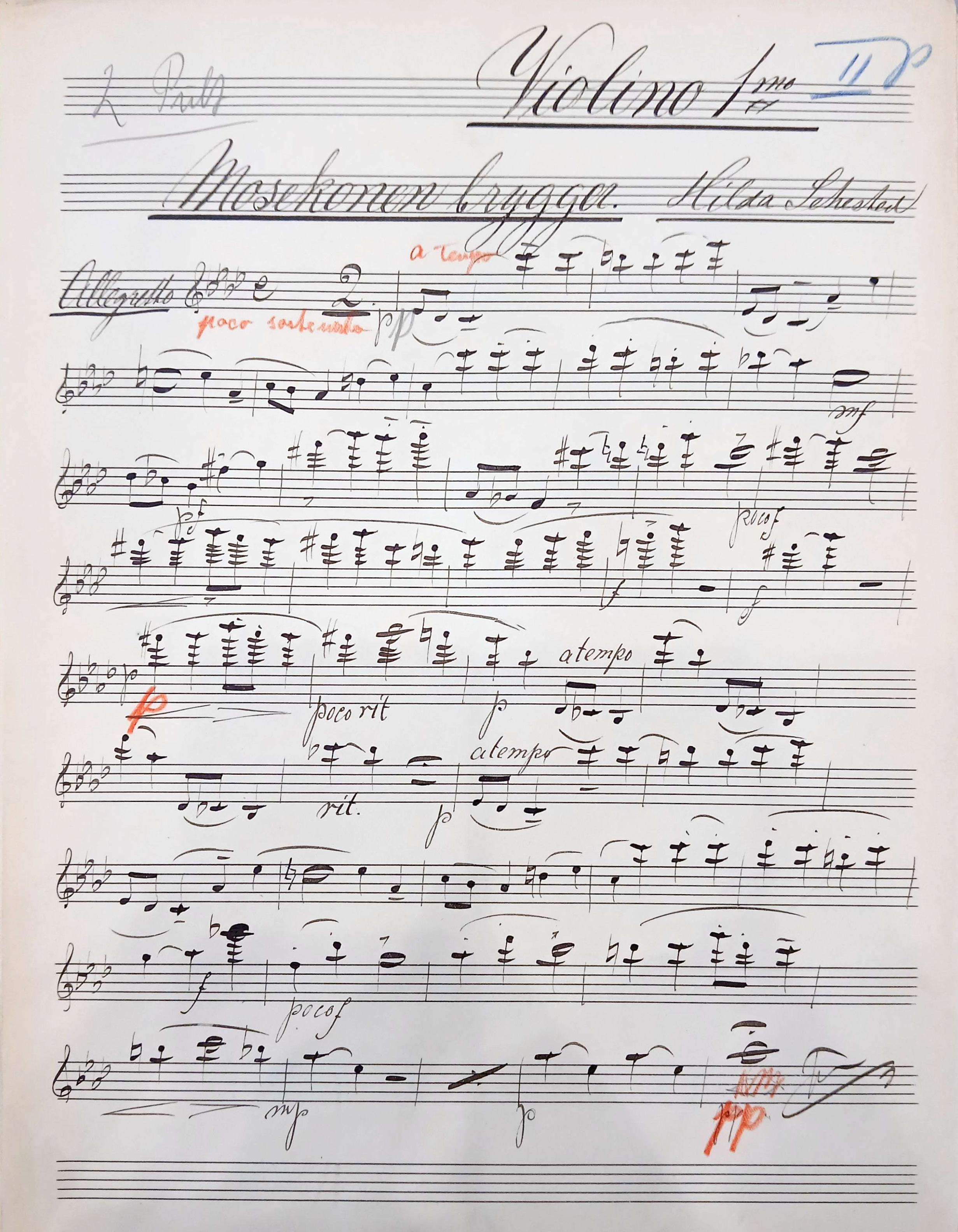

A Set of parts, transcript.

Printed title label: “[instrument] / Mosekonen brygger/ Hilda Sehested.”

The set of parts was written out for the performance in 1915.

34.4 × 25.6 cm. 25 parts, written in ink with pencil and crayon corrections.

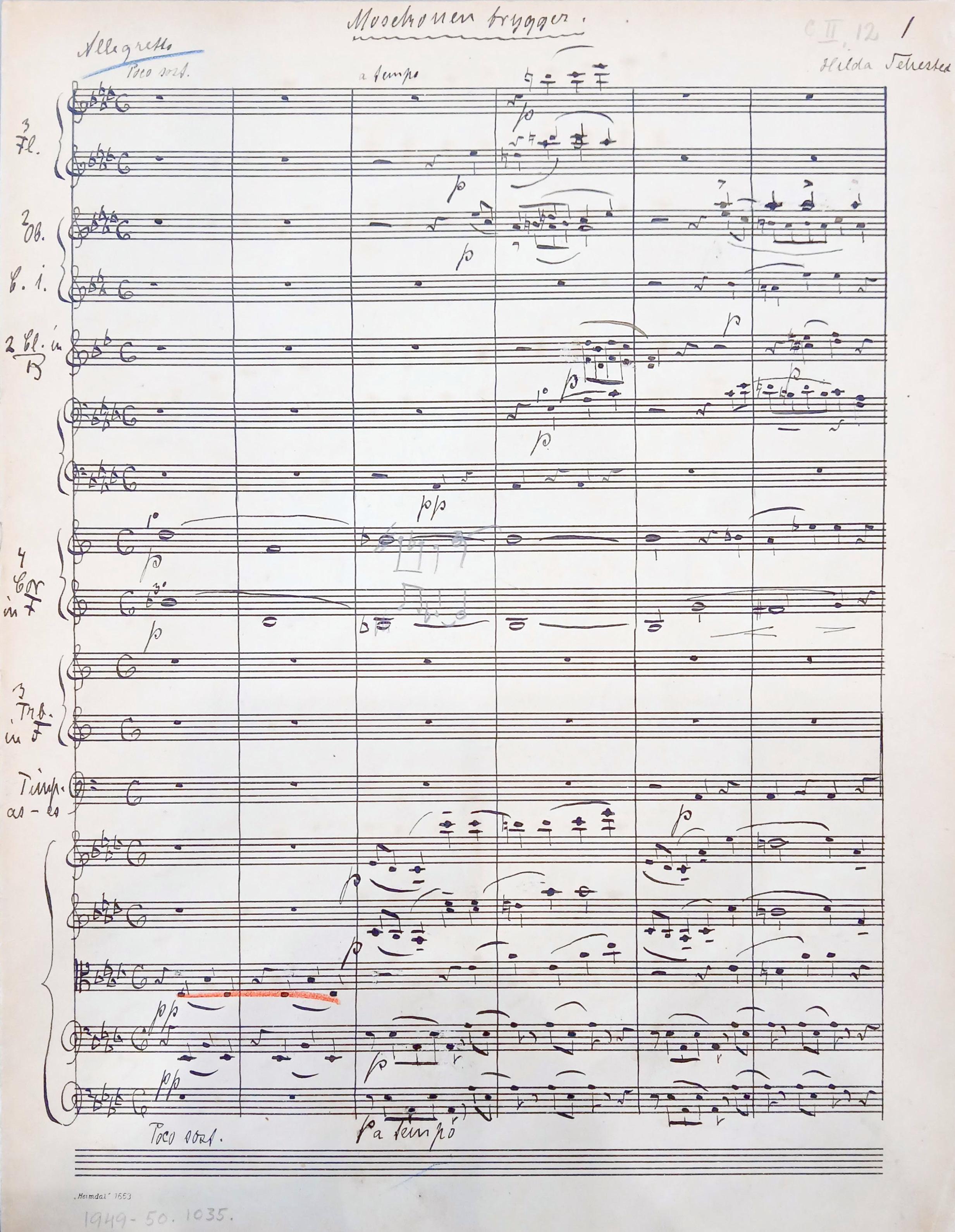

B Autograph score, draft.

No cover. On top of page 1 written: “Mosekonen brygger. / Hilda Sehested.”

33.6 × 24 cm. 8 pages, written in ink.

Evaluation of Sources

A has (most likely) been used under rehearsals supervised by the composer in 1915, which is one reason it has been chosen as the main source. Since A is a set of parts, the different parts will be identified with their part name (fl.1,2, cor.3, vl.2a) etc. with latin letters used to identify string desks. Although B is a score written in the composer’s hand, with ink and crayon markings (in unknown hand?), it has been regarded as a draft. It remains unclear when B was produced; however, if it is indeed a draft, B must have been produced prior to A

Discrepancies between A and B suggest the existence of another score (α) from which A was copied. α is believed to have been a fair copy – possibly based on B – and may have been used in the 1915 performance. This leaves A as the score closest to α, and its significance is further established by the fact that it contains corrections in Hilda Sehested’s hand. Since there is no proof that the corrections appear in α, the editor has selected A as the main source. B has been consulted in cases where A is ambiguous or deficient, since any reading found in both B and A must also have been present in α

Regarding the string parts – where 2 to 6 desks exist depending on the instrument – the editor has evaluated each desk part carefully and chosen a main source for the specific instrument (see below). In this process, B has been consulted in a few instances to confirm if an argument was valid.

Violin 1 has 5 desks, designated a – e. 7 These often fall in two groups, when there are more than one plausible reading; in b. 3, for instance, desks a and e agree that there should be a slur from notes 1 – 2 and another slur from notes 3 – 4. Desks b – d, however, all agree that the first slur should begin on note 1 and end on note 3. In bar 34, the placement of f differs; in a, c, and d, it is placed between notes 2 and 3 while in b and d, it is placed immediately after note 2. This suggests that c was copied from d. Other discrepancies (for instance in b. 16) show that d’s reading agrees with B. Hence, d has been chosen as main source for vl.1.

Violin 2 has 3 desks, a – c, with b as the main source. For graphical reasons alone, it is possible to determine b as the source copied from α: b has the most clean look when it comes to the horizontal and vertical distribution of the notes; a and c look more rushed, as if they have had to follow a layout standard dictated by b. However, in b. 13, the slur’s endpoint on the last note in b. 13 has been emended to b. 14, note 5 thus following a and c. In bb. 23 – 25, it is unclear if the slur should go from notes 1 – 2 or notes 1 – 3. The editor has chosen the latter interpretation by analogy with vl.1 (= vl.1d).

Viola has three desks, a – c. Vla.b, however, is clearly a copy of a or c, since one system is missing and added in pencil at the bottom of the page. In b. 11, a has slur on notes 1–4 and c has slur on notes 1 – 3. Since a’s reading equals B’s, a has been selected as the main source.

Cello has three desks, [a] – [c]. Since any of them could plausibly serve as the main source, the editorial strategy in this case has been to adopt the reading supported by the majority of witnesses when multiple variants are present. Thus, in b. 19, [b] and [c] have f on note 1, while [a] has f before note 3. In b. 19 [a] and [b] has a tenuto on note 2 – [c] has an accent on note 2. In b. 36, [a] and [b] have a cresc. harpin on notes 1–2, while [c] has it only on note 2. For the contrabass, there are 2 desks, a and b. A tie in bb. 37 – 38 is present in both b and B; accordingly, b has been used as the main source.

In addition to the sources A and B, a piano arrangement (by the composer?) from 1921 also exists, titled “Sommerminder: Mosekonen brygger”. Since the work was performed on a piano already in 1911, another piano score (β) must also have existed (the same or in another arrangement). However, the piano scores have been regarded as arrangements and have therefore not been considered in the production of this orchestral version.

7 In A, desk parts are designated with Arabic numerals, except for Violin 1, which uses Roman numerals, and cello which have no designation. In this edition, desks are labeled with letters, such that letter a = 1/I; b = 2/ II; and so on.

Comments

In the Critical Commentary the following conventions are used:

1. “by analogy with” is used when something as been “added”, “emended” or “omitted” by analogy with another passage in the main source. The analogy may be vertical: when something is added “by analogy with” one or more instruments, it is understood that the analogy is with the same place in the same bar(s); or it may be horizontal: when something is added “by analogy with” one or more bars, it is understood that the analogy is with a parallel place in the same instrument(s).

2. “as in” is used when something is “added”, “emended” or “omitted” to correspond to the same place in another source.

3. “in accordance with” is used in cases where there is no authoritative source, only a guideline – for example, printed part material (or in the case of “Mosekonen brygger”, the draft score)

Furthermore:

1. the name of the timpani part is “Timpani As Es”. Despite of this, there are no flats before the notes a or e in the reprise part (from b. 27). Flats before these notes have been added tacitly.

2. In cases where one slur ends on a note, and the next begins on the same note, they have been emended to one slur tacitly.

3. tempo markings might be emended tacitly within the bar so that all instruments have the marking at the same time.

4. “by analogy”, “as in” or “in accordance” with “tutti” refers to all other instruments than the one in question.

Editorial Emendations and Alternative Readings

bar part comment

1 fl.1,2 ob. fag. “poco sostenuto” added by analogy with crayon/pencil corrections in parts and in cor.ing. accordance with B

cor. 2,3,4

trp. timp, vla. vlc. cb

3 fl.1,2 ob. fag. “a tempo” added by analogy with crayon/pencil corrections in parts and in accordance cor.ing. with B

cor. 2,3,4 trp. timp, vla. vlc. cb

6 fag.1

A: note 2: natural in pencil; correction respected by analogy with b. 30 (b with natural in ink)

11 cl.2 note 1: pf emended to p by analogy with cl.1 cor.1 note 1: mf added by analogy with cor.3 vl.1 note 1: mf at b. 10, note 3 moved to b. 11, note 1

15 fl.2 slur notes 1 – 2 added by analogy with fl.1, ob.1, cl.1 cor.4 A: before note 1: bass clef in pencil; correction respected

16 fl.1,3 ob. cresc dec notes 1 – 4 and 5 emended to notes 1 – 2 and 3 – 5 by analogy with fag.1 fl.2, cl. and in accordance with vl.1,2

18 fag.1 note 1: slur endpoint at b. 17, after note 4 emended to b. 18, note 1 (A: system break)

20 fag.2 A: natural in pencil; correction respected vl.1 notes 3 – 5: slur endpoint on note 4 emended to note 5 by analogy with vl.1

33 – 34 fag.2 tie b. 33, note 1 – b. 34, note 1 added (b. 34 – open tie from b. 33 (B: system turn)) in accordance with B

37 ob.2 cl.1

cor.1 notes 3 – 4: slur added by analogy with fl.2, fag.1, vl.1,2 cl.2 notes 2 – 3: slur added by analogy with fl.2, fag.1, vl.1,2 vl.2 notes 1 – 5: slur added by analogy with vl.1