edible NEW MEXICO

THE STORY OF LOCAL FOOD, SEASON BY SEASON

Mountains and Creeks

“Far up on heights, in regions of the mist,” wrote John Shepherd, a nineteenthcentury journalist and poet of Colorado and New Mexico, “silvery lakes . . . sleep calmly near eternal banks of snow—the source of the life which blooms so sweet below.”

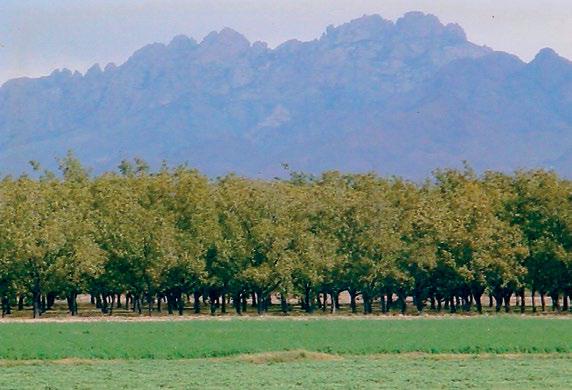

That Shepherd was writing of our region might come as a surprise to those who recognize New Mexico by its capacious horizons, its yucca-studded mesas, its cactus and cottonwoods. Known from afar for its desert landscapes, red rocks and badlands and bone-colored canyons, New Mexico is nonetheless a tapestry of mountains. The Sangre de Cristos, named, if not for alpenglow, for a red-throated bird or a red-crested flower or a crimson-colored spring; the Sandias, named for watermelon sunsets or Native squash or a saint; the Pinos Altos, named for tall trees; the Jemez, the Zunis, the Mimbres, each named for a people.

This issue of edible New Mexico is devoted to life in those mountains. We follow Ellen Zachos up Holy Ghost Creek, where she guides us in foraging for early spring greens. Weaving apprentice leticia gonzales talks with sheep farmer Elena Miller ter-Kuile about coming home, the health in diversity, and regenerating land in the Mountain West. Taking stock of the impacts of fire in Mora and around the state, ecologist Charles Curtin argues for a foodshed-centered approach to managing our drying forests, all likely to confront more fire.

In light of that vulnerability, we’ve gathered stories whose common thread is healing, through food and community as through land. At Whiskey Creek Zócalo, we find a constellation of garlic- and tree-growing, rural community building, pizza baking, and art making. Through Comanche Creek Brewery, we meet a group of disabled veterans finding recovery in fly fishing. On Taos Pueblo, we visit a café whose foods and practices are grounded in remembrance. Turning to the home kitchen, we explore a traditional practice with its own woodland roots: cooking with ash.

The mountains, whatever our perspective of their peaks, are very much of this world. We hope these stories likewise ground you in the tangible, be that through coal-roasted pumpkin fondue, spring greens fritters, a lamb pelt, or holistic, place-based ways to tend our working lands and forests through whatever comes.

Briana Olson, Editor

Briana Olson, Editor

Susanna Space, Associate Editor

Susanna Space, Associate Editor

Stephanie and Walt Cameron, Publishers

Stephanie and Walt Cameron, Publishers

PUBLISHERS

Bite Size Media, LLC

Stephanie and Walt Cameron EDITOR

Briana Olson

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Susanna Space

COPY EDITORS

Marie Landau and Margaret Marti

DESIGN AND LAYOUT

Stephanie Cameron

PHOTO EDITOR

Stephanie Cameron

EVENT COORDINATOR

Natalie Donnelly

SALES AND MARKETING

Kate Collins, Melinda Esquibel

PUBLISHING ASSISTANT

Cristina Grumblatt

CONTACT US info@ediblenm.com ediblenm.com

SUBSCRIBE ∙ LETTERS EDIBLENM.COM

We welcome your letters.

Write to us at info@ediblenm.com

Bite Size Media, LLC publishes edible New Mexico six times a year. We distribute throughout New Mexico and nationally by subscription.

Subscriptions are $32 annually.

Subscribe online at ediblenm.com/subscribe

No part of this publication may be used without the written permission of the publisher.

© 2024 All rights reserved.

Charcuterie & Wine Bar

DINNER PARTY BOARDS to-go for pickup & delivery

Thursday, April 18

Visit kitchenangels.org to see participating restaurants

ENCORE BRUNCH

Legal Tender | Sunday, April 21

Visit kitchenangels.org for details.

115 Harvard SE, ABQ

STEPHANIE CAMERON was raised in Albuquerque and earned a degree in fine arts at the University of New Mexico. She is the art director, head photographer, recipe tester, marketing guru, publisher, and owner of edible New Mexico and The Bite.

CHARLES CURTIN has decades of experience working with communities on climate adaptation in New Mexico and across the globe. He is the author of nearly a hundred articles, monographs, and books, including The Science of Open Spaces, Complex Ecology, and the forthcoming Beyond Resilience. He holds an MS in restoration ecology, a doctorate in landscape ecology, has cofounded programs in adaptive management at MIT, and has taught at MIT, Harvard, and elsewhere. Find him at charlescurtin.com

UNGELBAH DÁVILA lives in Valencia County with her daughter, animals, and flowers. She is a writer, photographer, and Indigenous digital storyteller.

LETICIA GONZALES is an apprentice to Carlos Trujillo of Trujillo’s Weaving Gallery and a graduate of the Ariat-sponsored Chimayo Weaving Apprenticeship hosted by Emily Trujillo and the Española Valley Fiber Arts Center. They live and work in Santa Fe.

BRIANA OLSON is a writer and the editor of edible New Mexico and The Bite. She lives in Albuquerque.

JENNIFER C. OLSON tells the stories of the Land of Enchantment’s people, places, and culture through outlets such as edible New Mexico and New Mexico Magazine. Whether shining a light on a single fruit or diving into the complexities of the rural food system, she relishes the grains of stories in all of life’s moments. She lives on the outskirts of the Gila National Forest.

SUSANNA SPACE is a writer and the associate editor of edible New Mexico and The Bite. Her essays have appeared in Guernica, Longreads, The Rumpus, the Los Angeles Review, and many other literary outlets. She lives in Santa Fe.

ELLEN ZACHOS lives in Santa Fe and is the author of eight books, including the recently released The Forager’s Pantry. She is the cohost of the Plantrama podcast (plantrama.com), and writes about wild foods at backyardforager.com. Zachos offers several online foraging courses at backyard-forager.thinkific.com.

An edible Local Hero is an exceptional individual, business, or organization making a positive impact on New Mexico's food systems. These honorees nurture our communities through food, service, and socially and environmentally sustainable business practices. Edible New Mexico readers nominate and vote for their favorite local chefs, growers, artisans, advocates, and other food professionals in two dozen categories. Winners of the Olla and Spotlight Awards are nominated by readers and selected by the edible team. In each issue of edible, we feature interviews with a handful of the winners, allowing us to get better acquainted with them and the important work they do. Please join us in thanking these Local Heroes for being at the forefront of New Mexico's local food movement.

Tucked along the Rio Ojo Caliente north of Santa Fe is NOSA, Chef Graham Dodds’s restaurant. “I’ve worked in kitchens all over the United States and Europe, from Juneau, Portland, Vermont, and Martha’s Vineyard

to London and southern Switzerland,” he says. But it is New Mexico that has stolen his heart.

“I attribute my love for the culinary arts to spending summers in Scotland cooking

alongside my grandmother with produce from her garden. Also, a family friend, a transplanted Swiss chef, who taught me how to make a soufflé when I was ten years old. My parents were huge foodies and we

would often pick vacation destinations for the restaurants we would want to eat at.”

Dodds graduated with honors from Le Cordon Bleu College of Culinary Arts in Portland, Oregon, and added an intensive pastry course at Le Cordon Bleu in London. Additionally, he took a course in Thailand learning traditional Thai cuisine and fruit and vegetable carving. In 2005, Dodds moved to Texas and ran some of the top kitchens in Dallas, including Bolsa, Hibiscus, Wayward Sons, and Elm & Good. There he rightfully earned accolades, including Restaurant of the Year from D Magazine, Best New Chef from the Dallas Observer, and Chef of the Year from CultureMap. And now he can add this honor from edible New Mexico.

You’ve worked as a chef here in the Southwest as well as in New England and the United Kingdom. You’ve also been visiting northern New Mexico since the 1990s. What draws you to a place? What made northern New Mexico the right spot to launch NOSA?

I love the property and the location so much. There is an absolute tranquility to the place that is so rare and special. The produce of New Mexico is inspiring as well. I never would have guessed it would be so prolific here year-round. The restaurant and inn is a magical space; I’m lucky to be here as a steward for this spectacular space.

NOSA combines fine dining with a particularly scenic, peaceful, and remote location. In your view, how do atmosphere

and aesthetics influence food and wine selections, and vice versa?

I believe the whole place evokes a peacefulness that translates to the whole experience. It’s a leisurely meal and you get to take your time savoring it all and enjoying the company you are with.

Is there a model that you’ve referred to as you’ve built NOSA, or a place you visited that inspired you to take the leap?

I’ve worked at many places, but nothing ever like this before. I definitely wanted to have a multicourse experience and I just love writing seasonal, ever-changing menus. That keeps it so fresh and new.

How does the dream of NOSA compare with the reality of day-to-day operations? What have some of the challenges been?

■ More intense avors varying by where beans were grown vs. one homogenized avor

■ Higher nutritional quality vs. lower nutritional quality, arti cial ingredients, stabilizers

■ Cornucopia of tastes and velvety mouth-feel vs. waxy mouth-feel and metallic tastes

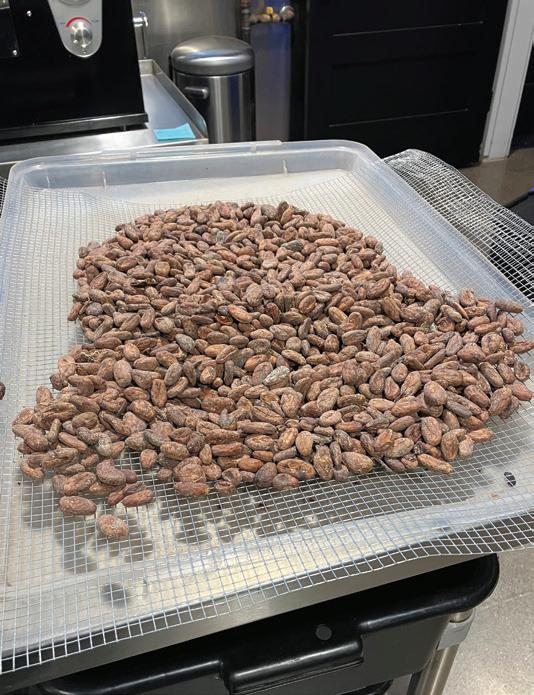

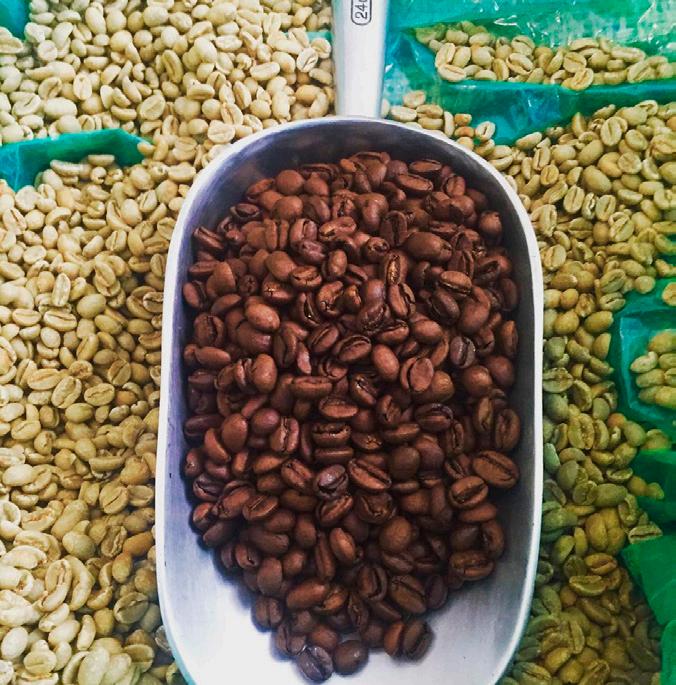

Eldora starts with cacao beans delivered from the world-wide growers we partner with

The harvested, fermented, and dried cacao beans are rst cleaned

go into the concher to be smashed and ground.

Roasting teases out the unique avors of the beans, while reducing any o -tastes from fermentation.

Ingredients are added to the chocolate liquor from the concher before pouring into molds.

Next, the hulls must be detached from the beans (winnowed), leaving the cocoa nibs.

The cocoa nibs will

The ground cocoa nibs become a smooth chocolate liquor in the concher.

The nished artisan chocolate bars are ready to be enjoyed by our discerning customers.

The cocoa nibs will

The ground cocoa nibs become a smooth chocolate liquor in the concher.

The nished artisan chocolate bars are ready to be enjoyed by our discerning customers.

Has anything surprised you?

It’s a huge amount of work. I have a great team, but I do a whole lot of the work myself, including every bit of food prep and cooking. The business side of things is always hard for me—I wish I could just create in the kitchen the whole time. I’m surprised with the quality of the staff I have here. They care immensely and are so genuine and kind. It’s such a great family. I really had no idea if I could even find anyone to work out here in the middle of nowhere.

Restaurants continue to struggle to find and keep staff, both front of house and back. Who do you rely on for help? Any secrets you’d like to share for recruiting workers and keeping your staff happy?

It’s really been word of mouth here. I hired a few people at the beginning and then they would tell their friends, and it’s grown

that way. It’s nice when they think highly enough of NOSA to tell others they are close to, which also adds to this amazing family dynamic we have here.

You’ve talked about NOSA as being focused on hyperlocal ingredients and the seasonality of the menu. Are there any dishes you’re particularly excited about making as the weather warms?

Gosh, I always love when spring comes. It’s a celebration for sure. The Vagabond Farmers had the most amazing fava beans last year, and that truly is one of the first signs of warmer weather! Also can’t wait for mushroom season—I’m a huge fanatic.

You’ve developed relationships with local suppliers like Khalsa Family Farms, Bread Shop, and La Lecheria, incorporating local ingredients and products into the dining experience. What role does community

play in NOSA’s ethos? Are there any new relationships or partnerships in the works? Well, it’s honestly the way I cook. I’d be lost without the stellar ingredients grown right around here. I’m lucky to have great farmers and suppliers nearby growing beautiful and tasty produce and always trying new and unusual things. I’m constantly working with them on what to grow next!

Describe a perfect day off.

Going mushroom hunting in the mountains. Anything else you’d like to share with edible readers?

I really appreciate all the love and support! It’s so nice to feel so embraced by the community, and I’ve really loved getting to know everyone over the last year and a half.

49 Rancho de San Juan, Ojo Caliente, 505-753-0881, nosanm.com

APRIL

- ServSafe Food

APRIL 25 - Bread Baking at Altitude: Using Ancient Grains & Sourdough

APRIL 25 - Water Bath Canning 101

MAY 9 – Koji Rice & Koji Barley: Starter Culture

MAY 23 – Vinegars from Start to Finish

JUNE 6 – Kraut & Kimchi

JUNE 20 – Fermented

“No one in my family eats out,” says Paper Dosa’s chef Paulraj Karuppasamy, speaking about the Indian home in which he lived until going to college. “I was raised vegetarian. South Indian food has a rich tradition in vegan and vegetarian dishes, and I am inspired by vegetables.” He earned a bachelor’s degree in catering science and hotel management, then began working at a resort in the Maldives, where he was exposed to the delicious curries of Sri Lanka. After several

jobs at fine restaurants, he was recruited by a friend to work at Dosa in San Francisco, an upscale South Indian restaurant, which later brought him to Santa Fe and to his own restaurant, Paper Dosa. His philosophy in running the kitchen at Paper Dosa, where everything is made from scratch, is “Use high-quality ingredients, keep it simple and fresh, and use a diverse group of vegetables”—because that’s what brings the flavor.

You’re the child of a mother who loved to cook and a father who was a farmer and grocer. Can you say a bit about how that experience influenced you and your decision to become a chef?

Growing up, the only animal products we ate were milk and ghee—no eggs. My amma makes, still to this day, every meal fresh and from scratch with local and in-season vegetables and fruits. Nothing is premade. No

We are eagerly anticipating this spring’s exciting dining events at La Quinta.

Join us for an unmatched culinary experience showcasing one of our favorite winemakers from the Willamette Valley, Martin Woods Winery. Guided by sustainable, holistic principles, Martin Woods’ wines express the voice of the vineyard and an authentic sense of place. This dinner will feature a beautifully crafted menu designed by the Los Poblanos culinary team that will specifically showcase the remarkable selection of fine wines.

As the historic Los Poblanos gardens burst into bloom, join us for a very special afternoon in celebration of Mother’s Day, with a magnifi cent tea service and an immersive guided experience around the property. Enjoy lovely organic teas from Taos’ small-batch, handcrafted tea company, tea.o.graphy, a sweet and savory menu prepared by Campo’s award-winning culinary team.

Visit lospoblanos.com/events-calendar for more information and tickets.

packaged masalas. I understand everyone says that their mom is a great cook, but my mom—she knows how to season her food perfectly. I cannot make yogurt rice like her, or her sambar or her puli kuzhambu or her biryani. The rasam I make at Paper Dosa is my mom’s recipe. She is my biggest teacher. My father is obsessed with being healthy. He is known for picking the best produce. When I was living in India with my family in 2012, my father would go to the market three or four times a week for our [grocery] store. Every tomato was delicious, every shallot fresh, every mint leaf dark green and lively. Now that my father is getting older and the family’s store is closed, my brother Raja goes to the market every day to bring home the freshest and ripest fruits and vegetables money can buy. Whatever my brother brings home determines what meals will be served for that day.

Because of the quality of food I was raised on, I try my level best to give my customers

the food I believe my mom and dad would approve of. When they visited, they were proud of the food we served at Paper Dosa. Describe your journey from culinary student to restaurant owner. What obstacles have you encountered? How did you know the time was right to launch your own place?

Being a chef was not my first choice for my career. I had other talents, but being the eldest son, making money for my family was top priority. After college, I worked at Reethi Beach Resort in the Maldives and The Residency Towers hotel in Coimbatore Tamil Nadu, where they served food from other regions. I was able to get acquainted with grilling techniques from Afghanistan and other Muslim regions. I also became more familiar with alcohol and cocktails. In India, at that time, the best jobs to get with the degree I had were with the cruise lines. The cruise lines only showed me how food could be wasted. I would work the burger

line and make close to a thousand burgers a day. Kids would come by with their trays already full of pizza and pasta and add one or two burgers on top. Being an Indian, this was hard to see. I met wonderful people and saw the most beautiful places while working on cruise ships, but I was not inspired by the cuisine. It felt like a factory.

Dosa [on Valencia Street in San Francisco] was an exciting place to be. To my knowledge, it was the first upscale South Indian restaurant to open in the city. When we first opened, the place exploded. All the best chefs in San Francisco came to eat our food. We had a two-hour wait every night. I learned that people from all over like South Indian food. That gave me so much confidence.

When Nellie, my wife, and I decided to move to Santa Fe, I tried to find work. I realized very quickly that if I wanted to see my career take off in Santa Fe, I would have to make my food. It was not easy. For one year, I would cook food and serve it once a

La Montañita Co-op–Nob Hill & Rio Grande

Lowe’s Market on Lomas

Moses Kountry Natural Foods • Silver Street Market

Triangle Market in Sandia Crest

Sandia National Labs

UPC at UNM • UNM Hospital in Cafe Ristra

Presbyterian Rust Hospital

INTEL- Rio Rancho • Nusenda Corporate Office

Skarsgard Farms

Presbyterian Cooper Center

UNM Campus - Mercado, SRC, Cafe Lobo

SANTA FE

La Montañita Co-op

Kaunes Market

Eldorado Supermart at the Agora

Christus St Vincent Hospital

Pojoaque SuperMarket

Ohori’s Coffee Roasters

LOS ALAMOS

Los Alamos Cooperative Market

Los Alamos National Laboratory

ESPAÑOLA

Center Market • Presbyterian Hospital

TAOS

Cid’s Market

GALLUP

La Montañita Co-op

week at a small tech company downtown. Setting up a small buffet next to vending machines in their break room, Nellie and I would stand there and watch the majority of the office workers make a queue to the microwave to reheat their lunches. It was very humbling. This was the same food that had brought the top chefs of San Francisco to my kitchen to shake my hand and tell me “Job well done.”

What was it about Santa Fe that drew you to launch a restaurant here?

Survival. San Francisco was too expensive to start a family there. I was working six doubles a week. Santa Fe had family and we had support. After I saw how supportive the community was when we first started, it gave me confidence to keep going.

What part does the availability of local foods play in your decision to offer a certain dish?

If I have to source something to complete a dish, I will do my best to get it from a local business. I use more than twenty-five different vegetables. We are a vegetable-based

cuisine along with rice and lentils, and whatever we can source on a consistent basis, we will put it on our menu: okra in summer, different squashes or radishes, sunchokes, greens. . . . Right now getting farmers to supply to restaurants has been a challenge. We are hoping that will change in the future. If an item cannot be sourced at the standard I need, I will take it off the menu. Like our calamari—we have our customers asking for it regularly, but I cannot get the same quality of calamari anymore, so I will not serve it.

What inspires you as a chef? Who are your greatest culinary influences?

South India inspires me. In my free time, I like to watch food videos of home cooks from South India. I always learn something. My years of working with different Tamil chefs in San Francisco has given me a rich background of techniques and recipes. I also get inspired by my family and the residents who live in their village back in Tamil Nadu. I always learn a new recipe when I go home.

What are some of your favorite foods to eat when you’re not at work?

I love New Mexican food! It is comforting and delicious. I also love Mexican food, like fresh tacos. I am inspired by Mexican food and I am now making my own variety of salsas at home. I also love pupusas. Anything else you’d like to share with edible readers?

We just can’t believe how lucky we are. Stepping into our tenth year, we are blown away by how supportive the Santa Fe community has been. I work every day to make them proud to have us as part of Santa Fe. We hope to continue to do our part to improve the quality of life for all who live here. When we see our customers’ faces light up when they walk in our doors, the smiles on their faces, and the graciousness they show to our staff, we feel so good inside. It’s our hardworking staff that makes Paper Dosa what it is, and we are so proud of what each and every one of them brings to the experience. We love Santa Fe. Thank you!

AN INTERVIEW WITH MOLLY RYCKMAN, VP OF SALES & MARKETING, HERITAGE HOTELS & RESORTS

It’s not easy to grasp the whole picture of Sawmill Market. The magic began in 2019 when the historic thirty-four-thousand-squarefoot lumberyard was transformed into a culinary and community hub. First, it’s the building. The industrial yet contemporary design incorporates regional elements while nodding to the historical roots of the neighborhood. Second, it’s The Yard, an outdoor

dining space that mirrors the openness of the food hall’s high ceilings and abundant windows. Third, it’s the more than two dozen individual local food businesses, including a taproom, cocktail and wine bars, and a coffee bar. As the cornerstone of the Sawmill District Development Project, Sawmill Market unites imaginative design with a platform for diverse food entrepreneurs in Albuquerque.

Sawmill Market is housed in a former lumber warehouse. How did that influence and inspire the market’s design? Why repurpose an industrial building as a food hall, and what elements of the historic structure were preserved or repurposed? The intent in designing Sawmill Market was to showcase an urban space rooted in the history of the neighborhood and

the lumberyard itself. According to Islyn Studio, the firm that designed the market in collaboration with owner Jim Long and experienced restaurateurs Jason and Lauren Greene, “Reclaimed timber from the original warehouse demolition and poured concrete comprise the flooring and custom furniture and fixtures. Among the historic materials, we weaved in storied elements of heritage and Indigenous craft . . . that serve as both an homage and, given the industrial architecture, a surprising subversion of New Mexico’s signature adobe.” Wood furniture, handmade tiles, hand-painted signage, and exposed beams nod toward the neighborhood’s roots. With floor-to-ceiling steelframe windows, the market incorporates beautiful New Mexico light along with local building materials and decor focused on reclaimed and local artisan craftsmanship.

The Sawmill District has been shaped by more than two hundred years of history. The earliest permanent settlement in the Old Town area was made by Tiwa-speaking

people about 1350 BCE. They lived between today’s Bernalillo and Isleta Pueblo, growing corn, beans, squash, and cotton in irrigated fields. Spaniards later called this area the province of Tiguex and gave the district its start when they established the Old Town settlement in 1706.

In the 1800s, houses were built along the irrigation ditches and major roads that are now Mountain Road, Sawmill Road, and Rio Grande Boulevard. Between 1903 and 1905, the American Lumber Company built a 110-acre complex in the district, and an electric streetcar line replaced the city’s horse-drawn trolley system. The original site was surrounded by farmland and swamps, yet people continued to flock to this area for jobs, so the streetcar was extended to serve the sawmill workers and businesses in the Sawmill District.

Most of the area’s major housing subdivisions were created during a post–World War I building boom. Farmland buffered housing from the company’s sawmill activ-

ity until the 1940s. Eventually the lumber company operations bordered Twelfth Street to the west and today’s West Sawmill Neighborhood to the south. And both housing and industrial businesses replaced farmland between Fourth and Twelfth Streets, bringing the two uses even closer together.

Old Town began to commercialize in the 1950s, and in the 1960s, I-40 cut through, sandwiching subdivision remnants between the highway and the growing industrial areas south of it. Old Town’s influence spread north and east in the next two decades, with restaurants, hotels, and museums. And the expansion continues today with the construction of the new Hotel Chaco and, of course, Sawmill Market itself.

What distinguishes the modern food hall/market from the food court at a shopping mall?

“In architecting the layout of the space,” Islyn Studio said, “we were inspired by the flexible functionality and wise use of space of the traditional Navajo trading posts, and

employed similar wayfinding structures throughout.”

In terms of cuisine, the intent was to give locals and out-of-town visitors a new standard among our food scene in Albuquerque. We also seek to align ourselves with local brands; we know this industry is competitive and success can be short lived if branding and messaging aren’t right from the start.

A number of early vendors at Sawmill still anchor the space, but there’s also been turnover. What makes for success in this setting?

We think it’s important to listen to what our guests are looking for while embracing new culinary experiences that highlight the emerging food scene in New Mexico. We

provide a platform for culinary creators to showcase their talent and vision.

Who manages the soundscape at Sawmill Market?

Trevor Randall, our general manager. Randall is an experienced restaurateur, beverage enthusiast, and motivated operator who takes pride in delivering the best experience possible. He brings his unique background and interests to Sawmill Market, creating a dynamic environment for everyone to enjoy.

Not surprisingly, given its size, Sawmill Market offers customers a wide variety of dining experiences—not just in cuisine but in atmosphere. What do you consider the sweet spots?

We want our guests to have a memorable

experience each time they visit the market. The goal is for guests to try the very best food in each category. A lively and vibrant atmosphere was created inside and carried to the outdoor spaces of Sawmill. The outdoor spaces are gathering places to embrace community while experiencing quality food and entertainment. Inside, each tenant offers a unique culinary experience with a specific offering not to be duplicated. What is a local food issue that matters to you?

Continuing to highlight the talent and creativity of local culinary innovators and creators in New Mexico.

1909 Bellamah NW, Albuquerque, sawmillmarket.com

Kvarøy Arctic Smoked Norwegian Salmon is the perfect way to add salmon to your dishes any day of the week. At Kvarøy Arctic, our smokehouse experts naturally smoke the salmon with extravagant care and technique, creating a luxurious mild flavor that will transport you to the great Norwegian outdoors.

At La Reforma, co-owner Jeff Jinnett says they do three things and they do them well: Mexico City–style street tacos rolled in tortillas they make in-house daily, a lineup of Mexican lagers and craft-style beers, and quality cocktails featuring their house-distilled spirits. Jinnett spent most

of his childhood in Mexico City, which is where he developed his love of Mexican cuisine. His family relocated to Knoxville, Tennessee, where he went to high school and the University of Tennessee. What followed was a career in the restaurant industry, working for independent and chain companies

throughout the Southeast and Southwest, landing squarely in New Mexico in 1994. “After thirty-five years working for others, it was time to strike out on my own,” he says. In 2019, Jinnett and a couple of colleagues started La Reforma in Albuquerque’s Wildflower neighborhood.

1366 Cerrillos Rd

314 S. Guadalupe St

1600 Lena St

Pre-order food and coffee for take-out or dine-in @ Iconikcoffee.com

Free parking everywhere

You and co-owner John Gozigian both have a background in starting breweries. What led you to open a taqueria that is also a brewery and a distillery?

Off and on, John and I had talked and dreamed about opening a casual and fun restaurant serving authentic Mexican food. Through a series of events and coincidences that might have been fate, the stars aligned, and we got that opportunity with La Reforma. Together we had opened Blue Corn Brewery, Chama River Brewing Co., and Marble Brewery, so it made sense to add a brewery component to our concept. The spark to add distilling came from John, who had the vision to take us in a direction that neither of us had any experience in. Talk about Mexico City. Do you have a favorite neighborhood? Was there a formative taco or street food experience that inspired La Reforma?

I love the Polanco neighborhood and its proximity to Bosque de Chapultepec park and Paseo de la Reforma. It is a vibrant cultural and culinary area and a lot of fun to be in. Everywhere you go there are tacos al pastor sizzling away on trompos— absolutely delicious!

Who touches each beer and spirit that you produce, and how did they come to be part of your team?

James Warren is at the helm of our brewery/ distillery and gets the credit for the wonderful creations that are on tap or mixed in our restaurant. James has a long history of success in brewing and distilling and we feel fortunate to have him on our team.

Where do you source the masa for your tortillas? What else is essential to a good taco?

We use yellow Maseca for our handmade corn tortillas, which is a bit uncommon, as most corn tortillas are made with white Maseca. We like the full flavor and heartiness of the yellow corn. Once you have a great tortilla, the key to a great taco is using fresh and high-quality ingredients and, of course, a chef who knows how to develop amazing recipes and execute them consistently. We are fortunate to have that in Javier Castillo, a friend and colleague for over twenty-five years who also happens to be an amazing chef.

Who selects artwork for the dining room?

John came across the artist Charles Harker, and we both love his vibrant depictions of

Mexican towns and landscapes. Our restaurant is almost completely decorated with his art, and it plays a major part in creating the contemporary Mexico City ambience of La Reforma. We get so many questions and requests to purchase the artwork that we have printed information ready to hand out! It’s a dry, windy afternoon in April. What beer or spirit are you drinking, paired with which taco or torta?

You will find me with a crisp, refreshing La Ref Lager in my hand and a tray of carnitas tacos. Our carnitas are simply delicious. Put them on a handmade corn tortilla with some fresh guacamole, cilantro, onions, and our salsas—and wow!

Anything else you’d like to share with edible readers?

We are extremely proud of the wonderful and talented group of cooks, hosts, servers, and bartenders that comprise the La Reforma team. There is an atmosphere of teamwork and caring at La Refoma, and we all share a passion to provide the best dining experience to our guests.

8900 San Mateo NE, Ste i, Albuquerque, 505-717-1361, lareformabrewery.com

What will you find at Whiskey Creek Zócalo? According to the hand-lettered sign out front, the answer appears to be “cold beer, good wine, live music, woodfired pizza.” But there’s more to discover at the site that the former Hurley schoolhouse has occupied since the 1940s or so.

On seven acres in the Arenas Valley, a community bisected by US Highway 180 as it runs between the town of Silver City and the historic mining village of Hurley, the restored stucco building is flanked

today by a wall of shipping containers painted with desert-toned geometric murals by Nichole Graf. You can step into Whiskey Creek Zócalo through the building’s main entrance or slip between a pair of turquoise doors—a break in the murals—to find yourself in a plant nursery. Doing a double take, you might glance back toward the parking lot and notice the antique orange Ford carrying another sign with bubbly letters spelling out the word “nursery.”

Seven-Course Chef’s Tasting Menu

Wednesday & Thursdays this Winter Dinner $100 | Wine Pairings $60

Join Us for Spring Dining!

(Wine) Tour de France

A Five-Course Wine Dinner

March 18 | 6pm | $130

Gravity Bound Earth Day Beer Dinner

Featuring Music by Cali Shaw

April 22 | 6pm | $120

More information and reservations can be found on our website

Yes, at Whiskey Creek Zócalo, you’ll find food, drink, entertainment, and plants. Soon you’ll also be able to glamp and enjoy multiday festivals at the sprawling bar/restaurant/venue/farm/nursery. The owners, Melanie Zipin plus her husband, Jeff LeBlanc, and her son, Rafael Zipin, shrug and say, “We wanted to create a space that reflected all our passions, which is why we’re kind of all over the place.” Each has experience in the service industry but is foremost an artist and musician with an inclination toward building community. “It felt more like a passion project than a business to me,” Melanie says. With no specific intentions, Melanie and Jeff purchased the four-thousand-square-foot building on its creek-side acreage in 2015. During the pandemic, Rafael brought home the experience he’d amassed during a decade of opening and operating bars in Los Angeles and Portland. In the three years they spent remodeling the building and grounds, they expanded their vision. And over their first year of being in business, they’ve allowed even more ideas to sprout rather than pruning back their dreams.

Being “all over the place” is part of what makes Whiskey Creek Zócalo such a gem. But what makes it really special is the way the family makes everyone feel invited. “Our community has felt separated for a while,” says Melanie, acknowledging that most locals live beyond the Silver City town limits and want a gathering place outside of downtown. “You can tell when you talk to people from the rural areas. They hopefully have a place that feels comfortable now.”

The family has devoted their energy and resources to creating a destination for people near—and far. That has come to include an impressive catalog of touring musicians who might otherwise have passed through without performing. “The Southwest is so hard because everywhere is so spread out. Somebody might have a gig in Austin and not have another until Phoenix,” says Rafael, the wizard behind the bookings. He strives to present music as a focus rather than as background noise, hosting about four touring acts each month and sprinkling in low-key events like the regular songwriters’ showcase. “We like to have a combination of giving people what they want to see and showing people what they haven’t seen yet,” Rafael says.

While Whiskey Creek Zócalo imports some of its entertainment, its restaurant sources whatever possible locally. The pizza, which is excellent, is baked in the horno Jeff built of clay. “My first wood-fired oven was probably twenty years ago. We started doing parties at our house, always cooking with fire,” he says, noting that piñon and oak flavor the pies, stuffed mushrooms, and roasted vegetables differently than a conventional oven could.

Radishes, turnips, beets, and squash from Frisco Farm the next county over get chopped into salads. Drinks sometimes include muddled juniper berries or strawberries plucked from containers out back, while salads may be garnished with foraged yucca flowers or sprinkled with the elm seeds that abound each spring. “They’re super delicious,” Jeff says.

The bar offers New Mexico wines along with beer from Silver City’s Little Toad Creek and other regional breweries. The wine- and beerbased cocktails, like sangrias, are mixed with house-made simple syrups. Rafael already plans on serving mesquite flour–rimmed cocktails when the venue receives its craft spirits license this spring. “We did make some of our own tepache too,” Melanie says.

In alignment with their homegrown ideals, the family started farming. With help from a Healthy Soils Grant from the National Resources Conservation Service, they grew the garlic used on their pizzas. This season, they’ll cultivate tomatoes and basil in their quarteracre garden. “We’ve started planting agave with the International Bat Conservation group,” says Jeff, who also rooted over a dozen fruit trees on site. “We love plants and growing,” Melanie says. The first component of the business to open its doors, the nursery sells pollinatorattracting perennials, cacti and desert shrubs, and heirloom fruit trees from a grower in the Mimbres River Valley.

As a restaurant and bar that spills into the sandy countryside via its nursery, garden, and orchard, Whiskey Creek Zócalo turns out to be a family-friendly meeting spot where adults can mingle while children run wild, exploring the arroyo, climbing tree stumps, roasting marshmallows around the firepit, and playing yard games. “When the weather is nice, to have people come and walk around the nursery and get something to eat feels like a nice merger of things that makes it feel more welcoming to people,” Melanie says.

Outdoors and in, diverse spaces create varied compartments for people to assemble, making Whiskey Creek Zócalo whatever the community needs it to be that day. In the airy main room, a birdcage strung with faux succulents passes for a chandelier, and reclaimed lumber shelves hold decanters and retro posters. A highway sign with peeling yellow paint reading “Welcome to New Mexico: Land of

Enchantment” brightens the burgundy wall behind the curved bar. Outside, stuccoed-over mine truck tires become planters, while a cattle trough nurtures goldfish and lily pads. “There are places to see the music or get away from the music. I’ve heard from people they can come be social if they want to, but they don’t have to,” Rafael says.

Visually, the speakeasy—or, as Rafael refers to the space, The Lodge—stands out. It’s a room “with its own mythos” that promotes ritual, conversation, intimate congregations, film screenings, or brazen performances for micro audiences. Rows of chairs and benches face a small stage. Another bench—as long as a pew but made from a vintage toboggan—runs along the wall between the bar and a brick hearth styled like an altar. Murals depict a ladder with swords as rungs, the silhouettes of snakes tangled up among thorny desert shrubbery, and a portal to who knows where. A phone booth on stage left is relabeled “Confessional,” while stained-glass artwork imbues reverence. The dark wood window aprons could have been reclaimed from either a Gothic church or pagan altar.

A rosy-walled chamber kitty-corner from the entrance is part greenroom, part flex space for artist demonstrations or workshops. It may prove especially essential when Whiskey Creek Zócalo holds a music festival, perhaps as soon as this summer. To accommodate musicians and artists coming for residencies, they’re adding a vintage RV campground. “We have four trailers we’re fixing up,” Jeff says, including a VW pop-up.

“There are a lot of irons in the fire,” says Melanie, who hopes that the guys will make time to build a bay out by the nursery where she can create a vintage shop. Rafael affirms, “It feels like if there’s something for everyone, it’s better.”

11786 Hwy 180 E, Arenas Valley, 575-388-1266, whiskeycreekzocalo.com

It was July 2020, the height of the pandemic, when the call came from New Mexico. Carpio J. I. (CJ) Bernal’s sister, Coral Dawn Bernal, had been found dead. CJ, who had grown up on Taos Pueblo, was with his mother’s family in Chilliwack, British Columbia. The US border was closed to all but essential travel, but he had to get home.

As he made his way to his family, CJ learned more about Coral’s death. The cause was a heart arrhythmia, but the family suspected negligence on the part of the Indian Health Service and the police. They called for a thorough investigation into the cause of Coral’s death, and a lawsuit followed. “They just didn’t do their job,” he told me when we talked in December.

The family held press conferences and drew up a list of demands, calling for justice for Coral. But the work took a toll. So CJ began to imagine something different: the creation of an arts center to honor Coral’s memory. The center would also preserve the legacy of CJ and Coral’s late grandfather, Paul Bernal, who fought for justice of a different kind: the 1970 return of Blue Lake, forty-eight thousand acres of Taos Pueblo land taken by the US government at the turn of the twentieth century.

Growing up on the pueblo, CJ knew hard work. Beginning in his early teens, he worked at restaurants in Taos, eventually becoming sous-chef at Deija. There he learned the fundamentals of culinary work, preparing him to cook in restaurants and cafés from New York

From thoughtfully curated treatments infused with functional botanicals inspired by the native herbs and plants of the high desert region to the healing energy of a holistic wellness journey, your experience at the Spa at Chaco will be… like no other. Wed–Sun

to Colorado to Canada. In New Orleans he learned about Southern cuisine; working in Los Angeles helped him master vegetarian cooking. All the while, he pursued modern dance and choreography, work he hardly mentioned when we spoke. But that his passions don’t end with food isn’t surprising given the creativity that abounds in his family—his parents are artists, and Coral, who studied at the Institute of American Indian Arts, was a prolific poet who received a Native Writers Award through the Taos Summer Writers’ Conference.

“It is definitely unexpected when people come in here,” CJ told me about Dawn Butterfly Cafe’s location inside his parents’ shop, House of Water Crow & Red Coral Flower. The month before, I’d visited the pueblo, and after an horno bread-baking session under a deep blue autumn sky, I crossed over the stream that flows between the clusters of adobe dwellings. A chair upholstered in gold and the scent of woodsmoke drew me toward the shop and café. Inside, the shop featured sculptures and carvings. A drum nearly as high as the ceiling stood against the wall beside a roaring fire.

What lay beyond, though, was indeed unexpected: a café space whose chalkboard was fully worthy of a big-city bistro. The list spanned from cortados to chai lattes to a dreamy tea menu offering clove, nettle, and yerba maté blends. A long table beside a second fireplace was lit with candles and decorated with dried flowers perched in architectural steel vases. On the far end of the kitchen area was an illustration of

a butterfly with a QR code printed beneath it. Beside that, above the small residential-style stove, hung a close-up photograph of a sunlightsplashed Coral, the image blurred, like a still from a dream.

The meal at Dawn Butterfly Cafe began with CJ’s father performing on the drum as we settled into our seats beside the fire. Hot handblended tea was set before us, a sprig of fresh mint on top, along with a mascarpone butternut squash soup and a delicious spinach salad with plum vinaigrette made from locally preserved fruit. CJ and two helpers, Sequoia Lefthand and Rannon Jiron, presented the dishes gently and unpretentiously, proffering plate after beautiful plate. When I learned about CJ’s time as a dancer and dance company director, his attention to arrangement made sense; there is a deliberateness to his movements, a sure hand, a performer’s calm.

If that had been the end of the experience, it would have been remarkable. But that was just a preview. Next came a bright pink mocktail made with chokecherry, orange, and honey; a dish of rich and textured blue cornmeal with chokecherry honey sauce and fresh berries; succotash with cedar-smoked salmon and honey goat cheese; and a dessert of blue corn lemon cake with bee pollen, accompanied by a lightly sweetened cortado. As the courses flowed and the burners hissed behind the counter, I exchanged glances with the other women around the table. This meal was far more than an opportunity to taste CJ’s cooking. This was an experience, an honor, a gift.

“This has not been an easy ride for me,” CJ told me later, recalling the process of getting the restaurant up and running. “This has been a lot of work, a lot of thinking, and a lot of planning.” The perseverance and grit he’s put in go far beyond the typical hassles and headaches of launching a business. Dawn Butterfly sits in the heart of Taos Pueblo, within a UNESCO World Heritage Site where electricity and running water are prohibited, and the tapering COVID restrictions that caused the pueblo to shut down to visitors for two years has made the process unpredictable. And then there is the grief of losing Coral. Any of it could easily have thwarted a less determined chef from attempting what CJ has created here. And yet.

To make the current location work, CJ applied for and won an economic development grant that allowed him to invest in lithium batteries to power the café, as well as refrigeration and an espresso machine. But working inside his parents’ shop is only the beginning for CJ. Another infusion of grant money allowed him to purchase shipping containers, which he’ll use to build a permanent space for Dawn Butterfly on Veterans Highway. Adjacent to the café, a center for art and literature honoring Coral Dawn and Paul Bernal will offer resources to tribal members. CJ plans to break ground on the new location this spring.

Until then, CJ will offer his café menu, hold special dinners to raise funds for the arts center, and cater events. Asked about how he plans to develop his menu over time, CJ says he’d love to create dishes made with only traditional Native foods, but the cost is too high for that, at least right now. So he’ll continue to serve meals that fuse traditional and modern culinary techniques and highlight local and traditional ingredients, like preserved fruit compotes, blue corn, and sage. The café will work with another Taos Pueblo–based business, Red Willow Farm, for access to local produce.

With everything he does, CJ keeps in mind the sister whose image watches over the kitchen, her features striking in their similarities to his. “We haven’t given up yet,” CJ says of the fight for justice and accountability for Coral. Last year, talks began with filmmakers to create a movie about the case. It’s hard to know what the outcome will be, but it seems certain her legacy will remain strong in her

hands.

Words and Photos

by Stephanie Cameron

vegetable ash simple syrup

vegetable ash salt

vegetable ash

leek ash shards

We humans have five basic taste sensations: sweetness, sourness, saltiness, bitterness, and umami. Some have argued that a sixth taste sensation—smokiness—imparts a rich earthiness to food. This is where edible ash comes into play in this edition of Cooking Fresh.

Ash has been a part of food culture for centuries, mainly due to chemical properties that make it an asset in food preservation. For hundreds of years, Native Americans have soaked field corn in lye made from wood ashes, helping make specific B vitamins bioavailable, which can prevent nutritional deficiencies. Europeans have long used ash in cheese making to help develop a rind. More recently, edible ash has become part of the tool kit for contemporary chefs.

You might expect vegetables reduced to ash to taste like carbon, but the ash retains a remarkable amount of the vegetables’ original character. Vegetable ash can be a finishing sprinkle on soups, cooked veggies, cheeses, or meats. It’s also great in sauces, where it adds flavor. There are manifold possibilities, both for the vegetable matter used to create the ash and the applications.

For this recipe, we are sticking with onion skins and the pale and dark green parts from leeks, but you can use almost any vegetable scrap to create different nuances. Corn husks and silk, fennel fronds, citrus peel, and herbs all provide opportunities to get creative with ash. After making your vegetable ash, create salts and simple syrups to use for seasoning dishes and creating cocktails/ mocktails.

4 leek tops, roughly chopped

Any amount of onion skins

Spread a single layer of onion skins and leek tops on a metal baking sheet. Place under the broiler with the rack 8 inches from the flame and cook, turning once or twice, until thoroughly charred and crisp, about 1 hour. Ensure adequate ventilation with an open window and the oven vent on high.

Remove from the oven, cool completely, then pulverize in a food processor or powerful blender, or in batches in a spice grinder. Store indefinitely in a tightly sealed container.

Combine equal parts powdered ash with sea salt (smoked or plain) and pulverize once again. Store indefinitely in a tightly sealed container.

The flavor of ash can vary widely, producing overtones that go from charred to acidic to sweet or smoky. The technique is versatile and can be used to bring a broad range of flavors out in a dish. Used sparingly, ash can add a delightful bitter/charred note to dishes. That said, it doesn’t appeal to everyone.

A word of caution: Given that research on the potential health impacts of burnt foods is inconclusive, it’s recommended that you use restraint when cooking with ash, as is the practice in traditional foods. Consider the purity of your ashes when cooking any of these recipes. Ashes made from chemically treated wood, newspaper, egg cartons, crumpled paper, and chemical logs may be toxic and are unsuitable for cooking. While some compounds produced from cooking foods at high heat may be carcinogenic, there is not consistent evidence linking them to cancer.

To make syrup, heat 1 cup of sugar and 1 cup of water on the stove until sugar dissolves, then add 2 tablespoons of vegetable ash. Let sit for 30 minutes, until cool. Strain through a mesh sieve into a glass jar. Store in the refrigerator for up to a month.

Makes 1 mocktail

Using ash salt and ash syrup, you have lots of options to smoke up your next mocktail. Ash salt is used to garnish the rim of the glass, and ash syrup and grapefruit mimic the citrus and smokiness of a mezcal paloma.

3 ounces grapefruit juice (about 1 small grapefruit)

2 ounces lime juice (about 1 large lime)

1 ounce ash simple syrup

1/2 ounce maple syrup

2 dashes grapefruit bitters (or orange bitters)

3 ounces soda water

Vegetable ash salt, for rim Lime wedge, for rim

Juice grapefruit and lime. Rub the rim of a collins-style glass with a lime wedge, dip it into vegetable ash salt, fill it with ice, and set aside. Add grapefruit and lime juice, ash syrup and maple syrup, and bitters to a cocktail shaker and shake. Pour into glass and top with soda water.

Adapted from Marjory Sweet

Serves 2–4

I highly recommend getting fresh carrots from your local farmers market and experimenting with different varieties. I used orange carrots, but this recipe works wonderfully with white, yellow, red, or purple ones—the key is freshness. The sauce stores well in the refrigerator, and you can keep the surplus in a squeeze bottle to drizzle on roasted vegetables.

2 cups carrot juice

2 sheets of kombu or other dried kelp

3 tablespoons butter

1 pound carrots, chopped into 1-inch chunks

1/2 teaspoon kosher salt

Zest of 1/2 orange

Juice of 1/2 orange

Vegetable ash, for garnish

Heat carrot juice and kombu over very low heat, uncovered, and steep for 45 minutes. Heat butter in a wide pot until foaming; add carrots and salt. Toss carrots in butter and add carrot juice, discarding the kombu. Cover and cook, stirring occasionally, for 6–8 minutes, until the texture is fork-tender but not mushy. Drain, reserving the juice, and cover carrots to keep warm. In saucepan, over high heat, add orange zest and juice to the reserved liquid and reduce by half, until slightly thickened, about 7–8 minutes. Serve braised carrots with their juice and sprinkle with vegetable ash.

Explore our beautiful space filled with the best wines, spirits, and beers from around the world! Enjoy a beverage in our Purple Pachyderm in-store lounge.

632

•

•

2574

Adapted from Fire and Ice: Classic Nordic Cooking by

Darra GoldsteinServes 4

This ancient culinary technique still resonates today. When you smear celery root, or celeriac, with a paste of salt and ash, the interior turns out creamy, with smoky undertones. Cracking it open at the table will add a touch of drama and expose the perfectly seasoned and tender flesh.

You can use ash from a regular fireplace or grill if it comes from untreated hardwood. I used juniper ash sourced from Shimá of Navajoland. You can make your own ash as well. Lois Ellen Frank of Red Mesa Cuisine details the process in her cookbook Seed to Plate, Soil to Sky: Modern Plant-Based Recipes using Native American Ingredients, and also has an instructional YouTube video.

1 small celery root (about 14 ounces), scrubbed

2 1/2 cups sea salt

3–4 ounces wood ash

1/2 cup water, or as needed

2 tablespoons butter

2 tablespoons parsley, chopped

Preheat oven to 350°F.

In a small bowl, stir together salt, ash, and water to make a paste that holds together when you squeeze it with your hand (the amount of water will depend on how dense the ash is).

Cover the celery root with the paste, pressing it down so that it adheres. Place the celery root in a baking dish. Bake until you can easily insert a small knife, about 2 hours.

Just before the celery root comes out of the oven, melt the butter in a small pan over low heat, and stir in the parsley. Set aside.

Remove celery root from the oven and place on a serving dish. Serve whole at the table and crack the crust with a meat mallet or the heel of a knife. Use a spoon to scoop out the celeriac and drizzle the parsley butter over the top. Celery root can also be sliced and served in individual portions.

Serves 4

This recipe is a campfire showstopper, but you can also make it in a firepit in your backyard. Use only established firepits, fire rings, or grills in areas without risk of wildfire, and take appropriate cautions when building fires at home. A cast-iron dutch oven is ideal here, but a camping saucepan would also work. The ash-charred pumpkin becomes a serving dish for the fondue.

I hit up The Mouse Hole Cheese Shop in Albuquerque to source the perfect duo of cheeses for our creation, but gruyère and emmentaler are tried-and-true choices. Grab a crusty French baguette and dig in! The best part is when the tender, sweet pumpkin flesh begins to combine with the melty cheese in each scoop. If you are lucky enough to forage chanterelle or porcini mushrooms, by all means, substitute them for the shiitakes.

1 3-pound kabocha squash (or other small pumpkin)

3 tablespoons unsalted butter

16 ounces shiitake mushrooms, cleaned and sliced

1 garlic clove, thinly sliced

1/2 cup white wine (preferably a dry, light-bodied wine like sauvignon blanc)

12 ounces cheese, grated (I used a mix of alpenhorn and gruyère cheeses)

Sea salt

Set the pumpkin in hot coals at the base of a campfire or in a portable firepit located on a nonflammable surface at least 15 feet away from any structures or woody material. Pile up the coals around the pumpkin. Roast until tender, about 20–30 minutes. Don’t worry about the exterior char; move the pumpkin around while roasting so it cooks evenly.

Carefully remove the pumpkin from the coals, let it cool to the touch (10–15 minutes), then remove the top with a knife, jack-o’-lantern style, and scoop out the seeds.

Place the pumpkin in a small-to-medium (~2 quart) cast-iron dutch oven and return to the coals. Place the lid on and keep warm while you prepare the mushrooms.

Set a cast-iron skillet over low flames on a grill grate or directly on the coals. Add the butter and shiitakes. Sauté until deeply caramelized, add the garlic, and cook for a minute longer. Add a pinch of salt.

Remove the lid from the dutch oven. Add wine into the pumpkin, then slowly stir in cheese a handful at a time, waiting for each batch to melt before adding the next. Once all the cheese has been added, top with the mushrooms and remove from the fire. Eat with spoons, scooping out chunks of soft, roasted pumpkin and melted cheese. Serve with a crusty French baguette.

Come in for breakfast or lunch. Creative American classics made from local and organic ingredients.

Wednesday–Sunday 8am-3pm

BREAKFAST ‧ LUNCH ‧ CATERING

2933 Monte Vista NE, Albuquerque ‧ 505-433-2795 theshopabq.com @theshopbrealfastandlunch on Instagram and Facebook

Makes 1 quart

Yes! Drop the burning piece of wood into the cream! It will delight your sixth sense in a way you’ve never experienced. Use wood chips or a piece of your favorite smoking wood. I am using cherrywood because, sadly, my cherry tree died this year, but you could use apple, hickory, or oak. Each one will lend a different smoky profile.

2-inch piece of clean cherrywood or 1 cup wood chips

1 1/2 cups heavy cream

1 1/2 cups whole milk

6 egg yolks

3/4 cup light brown sugar

1/8 teaspoon kosher salt

1/2 cup pecan pieces, toasted

Pour cream and milk into a large bowl. Heat the wood over a fire until it’s engulfed in flames—I did this standing over my gas grill. If using wood chips, light a fire in a metal pan you don’t mind scorching. Extinguish wood or chips in the cream mixture and allow it to infuse for 20–30 minutes, then remove wood and discard.

Add egg yolks, sugar, and salt to the infused cream and whisk. Transfer to a saucepot and heat on medium high, turning down the heat when the mixture starts to warm and the cream mixture has barely thickened. Continue to whisk continuously, being very careful not to curdle the eggs. As the cream warms through, remove pan from heat and continue to whisk for a couple of minutes; it will continue cooking off the heat.

Pour custard mixture into a bowl, and allow to cool. For the best texture, cover and refrigerate overnight.

Process the ice cream in an ice-cream machine according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and churn until the cream starts to thicken. Stir in the toasted pecans while the mixture is still soft. Remove the ice cream from the machine, transfer it to a covered container, and freeze.

Serves 8

Level: Intermediate | Prep time: 15 minutes; Cook time: 55 minutes;

Cooling time: 10 minutes;

Total time: 1 hour, 20 minutes

This savory tart is layered with caramelized onions and is the perfect appetizer for parties or serving as a main course for Sunday brunch.

Ingredients

14 ounces (1 package, if using premade) of all-butter puff pastry (we used Dufour Classic Puff Pastry)

3 tablespoons butter, divided

2 medium yellow onions, halved and thinly sliced

1/2 teaspoon salt, divided

1/4 teaspoon black pepper, divided

1/4 cup white wine

1/4 cup beef stock

12 ounces shiitake mushrooms

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 tablespoon fresh sage leaves, finely chopped

1 3/4 cups cheese, grated (we used a mix of asiago and sharp white cheddar cheese from Tucumcari Mountain Cheese Factory*)

1 egg, beaten, for egg wash

Thaw puff pastry according to package instructions and keep in the refrigerator until ready to use.

In a large, heavy-bottomed skillet over medium-high heat, add 1 1/2 tablespoons of butter. Once butter is melted and the skillet is hot, add sliced onions, 1/4 teaspoon salt, and 1/8 teaspoon black pepper, and turn the stove to medium heat. Cook onions, stirring frequently, until cooked down, deeply caramelized, and jammy—approximately 20 minutes. Once caramelized, turn heat up to medium high, pour in the wine, and let it bubble up for a minute and evaporate. Next, add in beef stock and allow it to cook until almost completely absorbed. Reduce heat to low momentarily, and spoon the onions into a bowl to cool.

Add remaining 1 1/2 tablespoons of butter to the same skillet and return the heat to medium high. Add in sliced mushrooms, 1/4 teaspoon salt, and 1/8 teaspoon black pepper, and sauté mushrooms for about 5–7 minutes, until golden but still meaty with some texture. Add garlic and stir in 1/2 tablespoon of fresh sage. Once aromatic, turn off the heat. Spoon mushrooms into a separate bowl lined with a paper towel to absorb excess moisture while cooling. Preheat oven to 400°F.

Place parchment paper the size of your baking sheet (at least 10x13 inches) on a work surface and sprinkle lightly with flour. Place the thawed puff pastry sheet on the parchment paper, and give it a gentle roll with a rolling pin, just enough to even the edges and make it symmetrical. (You want a size roughly 10x13 inches and 1/8 inch thick.)

Create a border for your tart, using a sharp knife to gently score the pastry about 1/2 inch from the edge, all the way around, taking care not to cut through the pastry. Use a fork to prick the center of the puff pastry a few times (not the border)—this helps it to bake flat. Slide the pastry, with the parchment paper, onto the baking sheet, and chill for 5–10 minutes in the refrigerator. Lightly sprinkle 3/4 cup of cheese around the bottom of the pastry, then top with sautéed mushrooms and caramelized onions. Sprinkle on remaining cheese. Gently egg-wash the border you created, and bake the tart until the pastry turns a deep, golden brown, approximately 22–28 minutes.

Allow tart to cool on the baking sheet for 10 minutes, sprinkle on the remaining sage leaves as garnish, and cut the tart into 8 pieces. Serve hot or at room temperature.

*Sourcing note: La Montañita Co-op carries Tucumcari Mountain Cheese Factory cheeses and Dufour Classic Puff Pastry at all their locations.

“When you see the beauty of the fish, you almost don’t want to eat them,” Louis says softly when I ask if the Trout Warriors eat the fish they catch. The answer is no—the group, which uses fly fishing and fly tying as a form of emotional and physical healing for disabled veterans in northern New Mexico, practices catch and release. “It’s more about the challenge than dinner or trophies,” adds Noah.

I’m momentarily surprised, although I know that the brassy Rio Grande cutthroat, New Mexico’s state fish, is renowned for its colors— and for occupying a small fraction of their historic waters. Through a decades-long restoration project, some 120 miles of stream in northern New Mexico’s Rio Costilla watershed were restored for the trout, and in fall 2022, volunteers released ninety thousand Rio Grande cutthroats into Rio Costilla and Comanche Creek. Perhaps that’s one reason that Doc Thompson, the Trout Warriors’ coordinator and president of the program’s nonprofit parent, Enchanted Circle Trout Unlimited, describes the fish—not only cutthroats but wild browns, rainbows, and brookies—as partners and relatives. Beyond conservation, it also

feels like a way to express how the group’s mutual supportiveness extends into the animal world.

“We treat each other like brothers and sisters,” Louis says of the Trout Warriors, and the care and love the group members feel for one another is palpable, even through Zoom. (The group’s twenty-some members represent three counties, and snow conditions had effectively closed the Enchanted Circle to travel the day I’d planned to visit.) Speaking to what he gets from fly fishing that he gets nowhere else, Gulf War veteran Victor talks of the serenity of being on the water but also of what Thompson calls “the camaraderie factor,” reflecting on the experience of being part of a like-minded group in the military.

“I like the outdoors,” says Ed, who was born and raised in the Española Valley and served in Vietnam. “Fly fishing has helped with my PTSD.” His words, simple and direct, belie the complex, difficult, deeply personal, and often lifelong struggles encompassed in that acronym.

“Fly fishing is almost like a zen experience. Trout are very smart fish—you have to be in the moment,” Noah says. With the ocean fish he cast for during his thirty years in Florida, he explains, you knew right away when you had one. In contrast, he describes trout as selective and wily. You get the feeling they’re inspecting the fly, considering it, he says, and then sometimes declining and moving on. “When we’re fishing, we’re in their world.”

Between May and October, the Trout Warriors meet monthly to fly fish, usually with the support of skilled volunteers. Funded entirely by donations, they also, Doc says, strive to go on a fly fishing healing retreat every year—an experience that allows them to deepen their connections both to the trout’s world and to one another. Fly fishing has been romanticized as a solitary endeavor, but one after another, the members of this group express the joy of watching other people fish—not only the thrill of observing a good catch but the joy of watching the expressions on one another’s faces. Off season, they get together once or twice a month, sometimes in person and sometimes via Zoom, for fly tying sessions.

I first learned of the Trout Warriors from Comanche Creek Brewery, whose original location sat within twenty feet of the eponymous creek. As it turns out, the Trout Warriors owe their name, in part, to a variety of hops. A few years ago, Thompson approached Comanche Creek Brewery owner and head brewer Kody Mutz with the idea of a fundraiser beer. At the time, Kody was working on a new beer, a Helles lager made with warrior hops—now known as Trout Warrior

Lager. Originally, I’d aimed to meet some members of the group at the brewery, but blizzard conditions and other logistics dictated that we meet virtually.

When, admitting my ignorance about fly fishing, I ask what goes into fly tying, Kelly compares the art of fly tying to a grandmother’s cooking. She runs through all the layers, from learning about entomology—“all the phases of the bug, learning how to tie the bug in the different phases of its life”—to learning about what fish eat in the different rivers and creeks they visit. Echoing what others have shared about developing mindfulness, she says, “Every time I come back to the table, I’m a beginner again.”

Earlier, Doc told me that the physical nature of fly fishing is good for reconnecting motor skills, but the members of the group have as much to say about the satisfaction of workmanship. Ed shares the excitement he felt the first time he caught a fish with a fly he tied himself—a zebra midge, he thinks. Victor talks about attending a workshop in rod building and the fifty-plus hours he spent building his rod, saying, “I’ve always enjoyed working with my hands.” The patience he and others have gained seems to breathe in the space they give one another on our call, listening as carefully as they speak. Reflecting on his own joy in working with glass and wood, Louis tells me about the mosaics he’s designing for the footstools and benches he’s building—some for his grandkids, some for a silent auction that will benefit the Trout Warriors.

One such auction is held in conjunction with an annual fundraiser at Comanche Creek Brewery. Opened in 2010 after Kody and his wife, Tasha Mutz, relocated from Denver to old family land in Eagle Nest, the brewery moved to its stunning location on NM 38 in 2019. In addition to brewing the Trout Warrior Lager twice a year and hosting fundraisers for the Trout Warriors, the brewery, which leans toward German styles like Altbier and Kölsch, has become a solid gathering place in the community. When I finally made it up in late January, a local father-son duo played sweet songs while others added plates to a table set up for a community potluck. The meadow beyond the patio was still snow covered, and as dusk approached, light danced in through abundant windows while community vibes (perhaps along with the effects of a glass of rich, silky porter) brought radiance into the space.

Not every regular is a local, yet the brewery offers a space for those fluent in remoteness, the curves of Palo Flechado Pass, and the expanse of the Moreno Valley, whether it’s the season for fly fishing or ice fishing. In that sense, it’s kin to as well as supporter of the Trout Warriors. While the group’s members include veterans of the

post-9/11 Afghanistan and Iraq era alongside those like Noah, whose military service stretched from the Cuban missile crisis to the Gulf War, Doc says they’ve faced similar hurdles and challenges, and he sees the group making a difference in members’ lives.

“It’s important to me as a veteran to get support from other veterans,” Kelly shares near the end of our Zoom gathering. “We tend to minimize the contributions of people who weren’t in combat,” she says. “Being in the military is its own kind of journey. Being in this group helps me understand how much healing I’ve done and how much is left to do.”

Given the Trout Warriors’ praise and gratitude for his work, I can’t conclude the interview without asking Doc what he’s gained from them. He’s quick to reiterate that while family members from past generations served, he did not. Then he says, “For anybody, whatever you’re dealing with, it’s one foot in front of the other. And you’re not necessarily alone in what you’re going through.”

ec-tu.org; contact Doc Thompson with interest or questions, at doct@flyfishnewmexico.com.

Edited and Transcribed by Ungelbah Dávila

riends. Sisters. Mothers. Professors. When women affirm women, it unlocks our power. It gives us permission to shine brighter.” In this conversation between sheep farmer Elena Miller-ter Kuile and writer and weaver leticia gonzales, both invested in healing the world from the ground up, the truth in this quote by journalist Elaine Welteroth becomes reality. In a land traumatized by the brutality of history, healing begins with the soil, travels up into blades of grass, vanishing into the atmosphere and returning in summer rains and winter snowpack. It passes through the mouths of the animals we raise with reverence, into the fibers of a flock’s wool and their sacred flesh that eventually feeds our children and community with the DNA of kindness.

At Cactus Hill Farm in high-elevation Capulin, Colorado, Elena and her father, Alan Miller, have become healers through agriculture. At their ranch, which sits at nearly eight thousand feet, they are sowing the seeds of ancestral knowledge and readying the land for future generations. From eight wool sheep purchased through the Taos Wool Festival, they’ve built up a diverse and tenacious herd. With every lamb born, every sheep harvested, and every pelt processed, Cactus Hill Farm regenerates identities and lifeways on the brink of extinction.

It’s such a complex history. And then—that’s the history of my farm, but my mother was born in Honduras and then came to the United States to study soil science. Genetically, she’s Dutch, but she mostly grew up in Central and South America. You know, we are very embedded in the community. We’ve been here since before Colorado was a state. But I think it is also good to have a little bit of an outside perspective. leticia: What is the name of your community?

Elena: It’s Capulin, C-A-P-U-L-I-N.

leticia: Like the cherries.

Elena: Exactly. One thing I see, because I’m very ag-oriented, there used to be this identity around sheep, wool, and textiles, but also around food and community. I think policy has really marginalized these traditional farms, and we’ve lost so many. A lot of it is because they’ve lost their water. There is definitely this sadness of how these vital, beautiful little towns and communities that were based around agriculture are ghost towns now.

I think the economic part is key, too, because you had people that were able to make a living on a small acreage and then suddenly they had to get jobs and leave the community, and a lot of them never came back. I always think that our biggest export is talent, but there are weirdos like me that do come back home again.

leticia: I understand you’re trying to rehab the land you’re on and you’ve chosen to use sheep. Would you share some of the history around your family’s farm?

Elena: When this part of the United States was part of Mexico, the Mexican government created a series of land grants all the way through New Mexico into Colorado. Families were allowed to come in and homestead, and then make land claims. So that’s how my family ended up in New Mexico, and kept moving up north into northern New Mexico—Nambé and Española, Cuba—and then slowly started moving into Colorado in the 1850s. And then, of course, the Mexican-American War happened. So I always say we didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us, and we basically stayed in one place and became American citizens.

leticia: That’s the legacy of trauma. Some people come back to life, and some people you lose. A lot of what I see in our communities are people who haven’t been allowed to come back to life after incredible trauma. As you say, the border crossed us, and how is it possible to come back to life? What are the things that make us feel lively? Music, dancing, food, culture, fiber, working the land.

I’m deeply interested in your vision for your land and your career and company.

Elena: I come from this generational farm. I went to school for agriculture at Cornell, graduated in 2010. As I was there, I did a study abroad program called Rethinking Globalization, and it really helped me rethink how we think about poverty, how we think about other cultures, how we think about other countries. I came home and was like, I don’t think aid work is for me. The other thing I realized through these travels is we have a lot of work to do here.

“W We really need to step back the clock on a lot of damage that we’ve done and rethink how we consume. I don’t want my legacy to be for my father and grandparents—I want my legacy to be for my children and grandchildren.

Anyway, I’ve been slowly taking over the farm from my dad, and one of the things I got into was knitting. If you look at Indigenous cultures, Hispano cultures, there is a strong fiber art tradition in every culture.

We’ve had sheep since—I don’t even know how many generations of sheep. We have family that came from the Basque region of Spain, and they had sheep. My great-great-grandfather brought his sheep to Colorado when he was eleven. He herded them over the mountains from New Mexico into the landholdings here.

My dad—he was more of a farmer and less of a rancher—he sold all the sheep before I was born, but my grandfather raised penco (orphan) sheep when I was little, and I remembered them, so I convinced my dad to get more. I got into that and have been working toward having wool products. I love sheep; I think they’re really neat animals. What I also love is that there’s this huge capacity to do regenerative work using livestock, and so that’s what I’ve been focusing on.

leticia: When did you bring the sheep onto the farm?

Elena: In 2012. Somebody gave me some lambs, some pencos [Columbias], and I raised them. Then I bought eight wool sheep [CVM/Merinos]. And that was the start of my entire herd—I just found somebody at the Taos Wool Festival who won an award, and

I was like, “Can I buy sheep from you?” From eight sheep, I built up to 350. I’ve downsized a lot, but I’m probably going to go back up again.

My dad has also done a lot of work on regeneration on our farm. There was a mining disaster on our river that killed all the fish, and [the US Army Corps of Engineers] straightened the river and killed all the trees. So he’s worked really hard to rebuild a beautiful river; that’s the kind of work my dad’s been doing. And I am excited to be buying the farm this year, which is a big deal.

leticia: Congratulations!

Elena: Yeah, and I have some ideas on how to kind of set the farm up a little differently so we can do some really intentional grazing. We’re already seeing some results. We have some farm fields that have gone from 1 percent organic matter to 3 percent organic matter. It’s made a huge difference as far as drought tolerance and water retention, so I’m really excited to expand that.

And then I have a dream of someday creating an educational farm where people can tie into culture in a really deep way. I want to create a space where people can teach and talk about where they’re coming from and base it in some sort of ranching tradition.