® edible NEW MEXICO

THE STORY OF LOCAL FOOD, SEASON BY SEASON

Loose Leaf Farm, Clark Case, Ojo Conejo, Erica Tai, and Keegan Tranquillo

PARADOX Flow Down by Susanna Space FACES OF FOOD

Tending the Seeds of Land-Based Leadership in Northern New Mexico by Victoriano Cárdenas

Capulin Canyon by Ungelbah Dávila

Paletas by Stephanie Cameron

EDIBLE DISPATCH

Forty-Eight Hours in Puebla by Stephanie Cameron LAST CALL Boozy Paletas

A Tour from River to Tap by Erin Elder

THE ONCE AND FUTURE RIVER

From Buckets and Barrels to Tanks, the Work of Preserving Traditional Indigenous Farms and Recovering Sacred Rivers in a Drier New Mexico by Sarah Mock

THE ART OF MAKING WATER by Shahid Mustafa

Paletas, photo by Stephanie Cameron.

Watershed

There is precious little riverside dining in New Mexico, but it’s not for our rivers’ lack of majesty nor for our failure to recognize that rivers, whether wild or tamed, are precious. Their value is especially felt as we transition from spring to summer, when flows slow and farmers and stewards rely heavily on centuries-old acequia systems. Early summer is the season of crisp mornings and crisp harvests, of sunsets witnessed from restaurant patios and backyard gatherings. It is also a season of tremendous thirst, when anyone who lives here can understand the logic of dancing for rain.

In this issue of edible New Mexico, we take an expansive view of the watershed, featuring stories that tell of the many sources that sustain life in our arid land. Reporting from Gallup to the banks of the Zuni River, Sarah Mock shares modern approaches to the ancient art of water collection in communities contending with the repercussions of federal acts. In considering recent efforts at legislation to protect local waters from “forever chemicals,” Las Cruces–area grower Shahid Mustafa’s eye is on the water underground. We hear, too, about an Indigenous-led project to restore watersheds in the long aftermath of wildfire.

Dropping down from the mountains, we trace the ephemeral Santa Fe River to the mill where blue corn is ground for whiskey poured on Agua Fria. Poet and Taos native Victoriano Cárdenas talks acequias, farming, and genízaro identity with a Dixon grower and mayordomo, and we get the story behind the local food hub that just might have delivered the week’s produce to the restaurant where you picked up this magazine. Speaking of the foodshed: Among the Local Heroes highlighted here and in the latest episodes of 5-Minute Fridays are the winners of our Spotlight Awards for Farmworker and Food System.

To quench our thirst (and curiosity), Erin Elder takes us on an illustrated tour of the plant that treats river water for drinking in Bernalillo County. If it’s aqua vitae you seek, turn to the guide to Cocktail Week. For those occasions when you thirst for the boldest and coldest flavors of summer, we offer recipes and tips for homemade paletas. We recommend that you pair one with an afternoon connecting with your river. Stand in the sun and soak in the sticky, cool flavors. This, all of it, is the fruit of our watershed.

Briana

Olson, Editor

Robin Babb, Associate Editor

Stephanie and Walt Cameron, Publishers

PUBLISHERS

Bite Size Media, LLC

Stephanie and Walt Cameron

EDITOR

Briana Olson

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Robin Babb

COPY EDITORS

Marie Landau and Margaret Marti

DESIGN AND LAYOUT

Stephanie Cameron

PHOTO EDITOR

Stephanie Cameron

EVENT COORDINATOR

Natalie Donnelly

PUBLISHING ASSISTANT

Cristina Grumblatt

CONTACT US info@ediblenm.com

SUBSCRIBE ediblenm.com

Bite Size Media, LLC publishes edible New Mexico six times a year. We distribute throughout New Mexico and nationally by subscription. Subscriptions are $40 annually. Subscribe online at ediblenm.com/subscribe

No part of this publication may be used without the written permission of the publisher.

© 2025 All rights reserved.

Nourish your body & soul with fresh, globally-inspired, plant-forward foods scratch-made locally, with love

ANGEL FIRE Lowe’s Market ALBUQUERQUE

La Montanita Co-op Nob Hill & Rio Grande

GRAB & GO

Conveniently available at select fine markets

CATERING

For elevated events across New Mexico, call 505.266.6374

PATIO KITCHEN

Visit Albuquerque’s Nob Hill, 116 Amherst Dr SE Monday–Saturday, 10am–6pm

• ABQ Airport - W H Smiths ( 2 locations) • Lowe’s Market on Lomas • Moses Kountry

Natural Foods • Silver Street Market •

Triangle Market in Sandia Crest • Sandia

National Labs • UPC at UNM • UNM

Hospital in Cafe Ristra • Skarsgard Farms • Presbyterian Rust Hospital • Intel Rio Rancho

• Nusenda Corporate Office • Presbyterian Cooper Center ESPA Ñ OLA Center Market • Presbyterian Hospital GALLUP La Montanita

Co-op LOS ALAMOS Los Alamos

Cooperative Market • Los Alamos National Laboratory PLACITAS The Merc SANTA FE

Eldorado Supermart at the Agora • Kaune’s Market • La Montanita Co-op • Pojoaque

SuperMarket • Skarsgard Farms • Ohori’s Coffee TAOS Cid’s Market

CONTRIBUTORS

ROBIN BABB is the associate editor of edible New Mexico and The Bite. She is an MFA student in creative writing at the University of New Mexico and lives in Albuquerque with a cat named Chicken and a dog named Birdie.

STEPHANIE CAMERON was raised in Albuquerque and earned a degree in fine arts at the University of New Mexico. She is the art director, head photographer, recipe tester, marketing guru, publisher, and owner of edible New Mexico and The Bite VICTORIANO CÁRDENAS is a trans poet and writer from El Prado, and his ancestral home is El Torreón Hacienda. He grew up irrigating fruit orchards and fields of alfalfa with his grandfather, drawing water from the Acequia del Medio del Prado and the Acequia Madre del Prado. His debut book of poetry, Portraits as Animal, was published by Bloomsday in 2023.

UNGELBAH DÁVILA lives in Valencia County with her daughter, animals, and flowers. She is a writer, photographer, and digital Indigenous storyteller.

ERIN ELDER is an artist and writer using creative research methods to understand how people and landscapes shape one another. More of Erin’s place-based illustrated writing can be found on her Substack, site & scene. She lives on the banks of the Rio Grande, just outside Albuquerque.

SARAH MOCK is an agriculture and food writer, researcher, and podcaster, focusing on topics from farm production to ag history and economics. She’s written two books, Farm (and Other F Words)

LOCAL HEROES

An edible Local Hero is an exceptional individual, business, or organization making a positive impact on New Mexico’s food systems. Edible New Mexico readers nominate and vote for their favorite local chefs, growers, artisans, advocates, and other food professionals in two dozen categories. Winners of the Olla and Spotlight Awards are nominated by readers and selected by the edible team.

Over the course of the year, we invite these Local Heroes to share their stories and visions for the local foodshed on our podcast, 5-Minute Fridays.

and Big Team Farms. Her current project, The Only Thing That Lasts, is a podcast for Ambrook Research about the past, present, and future of American farmland. She lives in Albuquerque.

SHAHID MUSTAFA owns and runs Taylor Hood Farms, practicing regenerative organic agriculture on two acres in La Union and offering a CSA with home delivery. Through his nonprofit DYGUP/Sustain (DYGUP stands for Developing Youth from the Ground Up), he has worked with staff at Las Cruces High School to implement an environmental literacy curriculum and establish a one-acre plot where students receive credit for helping with all stages of vegetable production.

BRIANA OLSON is a writer and the editor of edible New Mexico and The Bite. A graduate of the creative writing program at the University of Houston, she lives in Albuquerque and can often be found walking along the Rio Grande.

SOPHIE PUTKA is a full-time journalist and part-time food writer and photographer. She has been a barista, outdoor educator, and mushroom farmer at local New Mexico businesses, and lives in Albuquerque with her dog Iggy.

SUSANNA SPACE, a writer and consultant long based in Santa Fe, is a former associate editor with edible New Mexico and The Bite. Her articles have covered Indigenous cuisine, culinary road tripping, and numerous local restaurants and bars. Her other journalism and essays have appeared in Guernica magazine, Longreads, and Searchlight New Mexico

5-Minute FRIDAYS

Every Friday, we share food stories served up with a side of levity—and no, no episode is actually five minutes. We have a blast while discovering new ways to think about and understand the food and drink that lands on our tables and getting to know the people who put it there.

Listen at ediblenm.com/podcast or wherever you get your podcasts.

FARM / RANCH, BERNALILLO

COUNTY

Loose Leaf Farm

What the Hail Kale: A Conversation with Co-Owners Mark and Sarah Robertson

Loose Leaf Farm is a small half-acre operation in the Village of Los Ranchos. In this episode, we are talking about community, CSAs, tools, leasing land, dwarf goats, limited-edition tomatoes, and all the things that make this little farm go.

Photo by Stephanie Cameron.

LISTEN

'Chimayó Tradition Green Chile Cornbread': A Taste of New Mexico Heritage

Imagine transforming a simple cornbread mix into a masterpiece of New Mexican flavors that brings generations together. That’s what you’ll experience with Chimayó Tradition Green Chile Cornbread. When that golden, chile-studded crust emerges from your oven, you’re not just baking cornbread – you’re creating moments to remember.

"The first time I made this cornbread," says Elena Martinez, a third-generation Chimayó home baker, "the aroma took me right back to my grandmother’s kitchen. The way the flame-roasted green chile weaves through every bite—it’s pure New Mexico magic."

Our mix isn’t just another cornbread recipe; it’s a celebration of regional flavors where sweet meets heat, where

tradition meets innovation. Each batch carries the soul of New Mexico’s cherished chile fields.

Find us at your local grocery store and transform your family table into a celebration of New Mexican flavor.

SPOTLIGHT: FOOD SYSTEM

Clark Case

Meet Me at the Co-op: A Conversation with the Manager of the Dixon Cooperative Market

Clark Case was pivotal in conceptualizing and establishing a local market in 2003 and became an employee in 2020. In this episode, we are talking about how the Dixon Co-op puts $400,000 back into the community annually by creating jobs, buying from local producers, and paying rent to the library.

Photo by Stephanie Cameron.

LISTEN

www.pigandfigcafe.com

pigandfigcafe@gmail.com

www.beefandleafcafe.com

FARM / RANCH, GREATER NEW MEXICO

Ojo conejo

Everyone Benefits from the Cow: A Conversation with Co-Owners Jen Antill and Heathar Shepard

Ojo Conejo has big dreams for the future in Ojo Sarco. In this episode, we are talking about homesteading, manure, Rose the dairy cow, fresh milk, and feeding the community.

Photo by Stephanie Cameron.

LISTEN

photo: Kitty Leaken

CHEF, SANTA FE Erica Tai

A Drive to Do the Impossible: A Conversation with the Executive Chef at Alkemē

From creating nutritional labels to helping open a restaurant with Hue-Chan Karels, Erica Tai has learned by leading in the kitchen. In this episode, we are talking about Alkemē’s culture-totable concept, taking inspiration from Vietnamese, Taiwanese, Korean, and Hawaiian Pacific Rim cuisine, and having fun while creating whatever they can dream up.

Photo by Stephanie Cameron.

SPOTLIGHT: FARMWORKER

Keegan Tranquillo

Early Bird Catches the Worm: A Conversation with a Farmer in the Española Valley

Keegan Tranquillo knows he wants to be outside for a living, and from birding to farming, he has found a path to fulfilling that dream. In this episode, we are talking about the seasons, the extremes of farming in the Southwest, adventurous eating, supporting farmworkers, and the birds .

Photo by Stephanie Cameron.

Photo by Eric O'Connell

Flow Down

TUMBLEROOT FARMHOUSE WHISKY

By Susanna Space

If you follow the Santa Fe River from its headwaters high in the Sangre de Cristos down into the foothills, through McClure Reservoir, past the adobe houses that line Upper Canyon Road, all the way along Patrick Smith Park and under Palace Avenue, you’ll find yourself traversing, as the land flattens, what was once fertile farmland irrigated by abundant acequias, their silver branches flowing north and south from the central trunk of the river.

Continue past the skate park, under the roaring traffic of Saint Francis Drive, and you’ll find the water rushing or trickling or absent altogether, depending on the season and the year. Past the tennis courts of Alto Park, just up the riverbank along the street named for the waters, among the gas stations and houses and dirt side roads, you’ll find the Agua Fria location of Tumbleroot Brewery and Distillery.

The mill at El Rancho de Las Golondrinas, a living history museum, photo by Jason Kirkman.

Sitting on the taproom’s spacious patio, you could be forgiven for not taking in the riparian landscape in favor of enjoying the sunshine warming your back. And if you did connect the fact that you were patronizing a watering hole just steps from the flow of snowmelt for which Native people named the land O’Gah Po’Geh as you sipped a drink made with Tumbleroot’s Farmhouse Whisky, you could risk underestimating the strength of that connection.

But let’s back up. That whiskey’s raison d’être begins, as many things do, with beer. Among Tumbleroot’s staple brews is its Farmhouse Ale, a beer whose roots reach far from the Santa Fe River and the US Southwest and back a couple of centuries. Tumbleroot co-owner Jason Kirkman crafted the beer with inspiration from the saisons of French-speaking Belgium, lightly fruity, hoppy ales developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and brewed in winter to refresh farmworkers—les saisonniers—during the busy summer months. Of particular interest to Kirkman was what many brewers consider the saison de saisons, the one produced by Brasserie Dupont since 1844, well known to be a classic example of the type.

From the Farmhouse Ale, a whiskey companion was kind of a no-brainer. “We loved the idea of a malt whiskey based on one of our favorite beers,” Kirkman says. With the tools already in hand at their brewery and distillery, creating a malt whiskey was relatively easy. It didn’t hurt either that Kirkman has a thing for Irish and Japanese whiskies, which are malt based.

But Kirkman, a bona fide craftsperson, isn’t one to take the easy way. Like the river, the process meandered. “We wanted [the whiskey] to be local and we wanted it to have a variety of grains. And we wanted to use some zippy farmhouse ale yeast”—the kind used to make those Belgian saisons. For additional complexity in the grain bill and a dash of New Mexican terroir, he sought a source for local blue corn. And the waterway that threads past Tumbleroot’s back door followed.

“Brewers will normally use flaked corn or something that’s been precooked,” Kirkman says, rather than raw kernels. But the New Mexican blue corn he bought from Sunny State, outside of San Jon, was distinct and hearty—and not easily tamed. “Those huge corn kernels will jam our barley malt mill,” Kirkman remembers thinking.

“I thought, we could take it to this distillery or that,” Kirkman says, reflecting on the decision on how and where to have the grain processed. He’d been visiting El Rancho de Las Golondrinas for years and offering Tumbleroot’s beers at events there.

“They grow grapes and they make wine,” Kirkman thought as he made the connection. “They’ve been growing hops. They have their own wheat and they mill it and they make tortillas. So it really is a working farm.” After a conversation with Las Golondrinas’ director of operations Sean Paloheimo, a history-loving brew nerd’s dream plot surfaced—one that circles back to the Santa Fe River’s journey west across the city and into La Cienega.

Left: Las Golondrinas director of operations Sean Paloheimo watching the mill's gears, photo by Jason Kirkman. Right: Former lead brewer Andy Lane and Jason Kirkman grinding the blue corn for the Tumbleroot Farmhouse Whisky, photo by Michael Chavez.

You could say the idea took Kirkman and his production team across the parking lot behind Tumbleroot’s Agua Fria location, tracing the water as it trickled away from its namesake street, under NM 599, and alongside the geometric patchwork of the Santa Fe Airport’s runways. There, those waters meet La Cienega Creek, which has long been a source of irrigation of Las Golondrinas’ property, and, traditionally, the power behind the historic mills that sit there among the fields.

Each fall since then, when the tide of visitors has receded and as the museum is packing up for winter, Kirkman and his production team take a field trip. Sacks of blue corn in their arms, they enter the largest and most prominent of the mills, a structure so picturesque it could have been lifted from the page of a storybook. “It’s a huge wheel,” Kirkman says of the towering wooden waterwheel that powers the mill, and when the stone that grinds the corn gets moving, “it’s definitely loud in there, but it’s pretty cool.” Paloheimo gets a bottle of whiskey from Tumbleroot’s newest batch for his trouble.

Back at the production space, Kirkman cooks the milled corn in batches, adding it to the stainless steel tank, the mash tun, where it’s

mixed with the grain mash to create the Farmhouse Whisky’s distinctive flavor profile. Finally, the whiskey is left to age in oak barrels. Two years later, the result is a springy and pleasantly sharp spirit with an effervescent warmth.

Served alone inside an aqua-blue, earth-shaped tumbler at the downtown Tumbleroot Pottery Pub—the location closest to the river’s source near Deception Peak—the spirit’s clarity and potency seemed to this writer to embody the river. And in a cocktail made with agave spirits, lime, and chipotle, the cool wash of flavor brought to mind mountain snow against a hiker’s warm palm. There at the bar, I thought of a walk I’d taken along the river when January’s cold snap hit and the young cottonwoods and willow branches were bare. The waters, unusually high for that time of year, had partially frozen over. I was struck by the play of light at sunset, and for a moment I stood still breathing the fresh air, watching my dog squint into the breeze, her paws balanced on the ice.

Multiple locations in Santa Fe, tumblerootbreweryanddistillery.com

Tumbleroot's head of production Michael Chavez and co-owner Jason Kirkman, photo by Stephanie Cameron.

New design, same trusted products. Visit lospoblanos.com

Rooted in Los Poblanos’ history and inspired by a traditional apothecary aesthetic, our refreshed packaging brings an elegant sophistication to our signature bath and body collection. Our artisan lavender products are proudly made in New Mexico, with essential oil from the certified organic Grosso lavender that is grown, harvested and distilled by our farmers. Incorporate the tranquil scent of Los Poblanos in your daily routine.

Tending the Seeds of Land-Based Leadership in Northern New Mexico

A CONVERSATION WITH JOSELUIS “AGUA Y TIERRA” ORTIZ Y MUÑIZ

by Victoriano Cárdenas

Acequia del Llano in Dixon, photo courtesy of Joseluis “Agua y Tierra” Ortiz y Muñiz.

An acequia runs with pure, cold water from the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, soaking a field of corn under the watchful eye of a parciante. Farmland is lush in the high desert of northern New Mexico because of these unique systems of irrigation and the tender care of their traditional stewards.

I’m native to Taos and while I now live in Albuquerque, I grew up learning how to irrigate from my grandfather, drawing water from the Acequia del Medio del Prado and the Acequia Madre del Prado to water our fruit orchards and alfalfa fields. I followed him all around our fields, learning when to plant, where to release the water, how to steer it where we needed it to go. A lot of kids went to the pool at the youth center to play in the water, but I had acequias in my backyard and that’s where I played—finding fossils and digging for worms, and making adobe bricks in empty SPAM cans. It was the perfect place to grow up, to learn about the ecosystem through a balance of work and play.

“Acequia technology is perfect technology; they are perfect systems. And it’s a social determinant of health: acequias flowing and corn growing,” says Joseluis “Agua y Tierra” Ortiz y Muñiz. “Not only to produce food, but people demonstrating traditional farming is in itself a healing practice. It’s healing, even just to see it.”

Ortiz y Muñiz is an Indigenous, land-based native New Mexican from his maternal village of San Antonio del Rio

Embudo (Dixon) and the Llano de La Yegua in the Santa Barbara Land Grant (Northern Tiwa territory). Together with his family, he tends crops and livestock and stewards his ancestral lands within the Embudo River Basin. His roots in traditional agriculture were passed on intergenerationally and he maintains a traditional land- and acequia-based way of life. Today, he is the mayordomo for the Acequia del Llano and the community liaison and project director of the ¡Sostenga! Center for Sustainable Food, Agriculture, and Environment at Northern New Mexico College (NNMC). I talked with Ortiz y Muñiz, who now goes by Agua y Tierra, about his work revitalizing these ancestral forms of knowledge, and the challenges he’s faced along the way.

Homecoming

Generation after generation, from colonization onward, so many of us have been uprooted from our lands. Still, some journeys back to the land begin with departure. Agua y Tierra left his homelands to move to the South Valley of Albuquerque, where he worked at La Plazita Institute, providing traditional healing to previously incarcerated and addicted youth and families, before returning to Dixon in 2019.

“Originally, I came up here with all this energy. I’d been in a bad car accident and broke my back. I had to relearn how to walk. After that, I moved back home, motivated and wanting to do some big work, only to face hurdle after hurdle. I came back hoping for welcome, trying to

Agua y Tierra with his daughter, Corina, on their family farm in the Embudo River Basin, photo courtesy of Joseluis “Agua y Tierra” Ortiz y Muñiz.

reestablish a sense of home, only to find myself homeless in my own homelands. I spiraled into a heavy depression when I realized those big changes wouldn’t occur overnight. Change has to be grassroots, from the ground up, and being able to appreciate that process helped me to root into this new person, focusing all of my intention around land and water.

“So I went on this inner search of identity and development of my genízaro consciousness, but my family has always bought into . . . that violent Spanish settler culture that was superimposed on us. And I thought, Who am I really? Do I want to be connected to that anymore? Don Bustos [of Santa Cruz Farm] mentored me through this process, and Richard Moore and Sofia Martinez through Los Jardines Institute mentored me in my recovery, which led to me entering this realm of leadership in my community, walking the same steps of my grandfather along the acequia and being a mayordomo, and defending the water and the land as an activist. I had this revival of self-identity as I began to understand my purpose . . . so I renamed myself Agua y Tierra, the Water and the Land.”

On Being Genízaro

Genízaro is the term used for Native Americans detribalized between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries in New Mexico and the surrounding Southwest. Under Spanish settler rule, genízaros were forced to work as slaves or indentured servants, and

were sometimes forcibly married or adopted into Spanish families. Gentrification and institutional violence continue to uproot us in the present day, not only from our land but from our food as well.

Like many New Mexicans, I didn’t understand my own family’s roots for a long time; we had only ever claimed Spanish identity. But I learned that several of my ancestors were detribalized from their original Indigenous communities—through displacement, conflict, and slavery—and forced to assimilate into a Spanish household, taking on new names, a new language, and a new religion. That erasure and many other violences still have effects on my family and, as Agua y Tierra says, in our wider communities today.

“I’m an heir to these land grant areas and to genízaro identity and history, and part of that history was settlers taking our land and resources by violence, and a mass erasure of our identity,” says Agua y Tierra. “Our ancestors’ systems were so dismantled that there was no capacity for the community to retain its leadership. They went defunct and weren’t able to self-determine by the systems governed by natural law. Part of the reason we’re so impoverished materially and in crisis is directly because of displacement and colonization. The descendants of the land and its stewards still exist but don’t know their history, identity, traditions. A big focus in my work is to bring out of obscurity the genízaro consciousness in the Indigenous peoples.”

Community limpia in Dixon, photo courtesy of Joseluis Agua y Tierra Ortiz y Muñiz.

Learning and Leadership

But how to develop leadership in a vacuum of understanding? In 2019, together with Don Bustos, founder and executive director of the Greenroots Institute, and Camilla Bustamante, former dean of community, workforce, and career and technical education at NNMC, Agua y Tierra helped to revitalize the ¡Sostenga! pilot program and turn it into a full-scale demonstration farm at the college, a crucial step in the growth of an agriculture program, unique to northern New Mexico, that aims to offer a support system to engage students in their own communities, farmlands, and businesses, and to use the classroom for teaching traditional practices.

“On my mom’s and dad’s sides, they weren’t the first generation [of] college graduates but instead stayed poor on the land as farmers, leaving behind a beautiful legacy of work with the land. I didn’t inherit anything when my grandparents died, but I inherited their stories and practices, and that is a great deal of wealth. That saved my life. If every descendant of northern New Mexico could hear these stories, they would feel such a strong sense of pride and an urge to go home, to return, and farm their grandparents’ land. Without that deep querencia for this place, as a recovering drug addict, and as a single father to an Indigenous baby girl, I didn’t know where I would land.”

Farming Is the Way Forward

Although there’s still plenty of work to be done, it’s easy to see that querencia for the land is alive at the ¡Sostenga! Center. After being a grassroots organizer for so long, Agua y Tierra is now stepping back to see how the seeds he’s planted have grown, focusing on being a father, and looking for the next generation of leaders to step up and lead the way.

“[Right now,] very few farms are producing food and most aren’t producing it commercially. We are not utilizing our traditional water-based/land-based networks, and so the water and land are not connecting to support mycelial networks in soil and other processes that can help to restore it. A return to the land would be a remedy for climate change and a lot of other issues our communities face. . . . Farming is our strength. Especially in a world where climate change is having such an impact, it is going to be our traditional wisdoms that pull us through, especially when it relates to food, to water. The land is forgiving, and there is still so much left of our culture. Our ancestors gave us tools to collaborate with nature and our connection to land and water. Engaging in land-based practices feels so familiar, it makes sense. We can feel the land calling us back home.”

Left: Agua y Tierra with one of his horses. Right: Greenhouse at ¡Sostenga! Center for Sustainable Food, Agriculture, and Environment. Photos courtesy of Joseluis Agua y Tierra Ortiz y Muñiz.

IN THE WILD

CAPULIN CANYON

REVITALIZING A WATERSHED WITH THE INDIGENOUS LANDS PROGRAM

By Ungelbah Dávila

Photos of Capulin Canyon from 1980, when Congress designated the surrounding 5,000 acres as a wilderness area, are a shocking contrast to the current view of the canyon. Today, a blackened, burnt swath of earth cuts through what was once a verdant ecosystem. Located in the Jemez Mountains, Capulin, once home to Ancestral Puebloans, natural builders and artists, belongs to a landscape altered by fire. In 1996, the human-caused Dome Fire ripped through 16,500 acres, destroying most of the Dome Wilderness. Fifteen years later, just as the grasslands and forests were coming back to life, the Las Conchas Fire, one of the largest in New Mexico’s history, burned 156,000 acres—scorching the same area, as well as nearby Bandelier. Then, in 2022, the Cerro Pelado Fire devastated 45,600 acres, mostly within the bounds of the Las Conchas burn scar. Capulin Canyon, cradling its namesake tributary, cuts through burn scar within burn scar on its way down to the Rio Grande. Now a field of charred sticks occupies what thirty years ago was a lush haven for plants and wildlife.

Without the presence of plant life that would naturally regulate how rainwater or snowmelt is collected and passed along to the Rio Grande, tribal and agricultural communities in the Middle Rio Grande Basin, which stretches from Cochiti Pueblo to Socorro, have one more card stacked against them in their struggle to access healthy water. Native Americans, often acknowledged as our region’s first farmers, were also this land’s first scientists, hydrologists, architects, engineers, botanists, astronomers, and ecologists. This could be one reason that Indigenous-led organizations around the state have long recognized not only the impact fire damage has on the watershed but the connections between all land uses, lifeways, and communities.

Capulin Canyon watershed, photo courtesy of Trees, Water & People.

“I come from a farming family in Santo Domingo Pueblo. We are a rich, vibrant community that still does farming as a way to preserve our lifeways,” says James Calabaza, program director for the Santa Fe– and Fort Collins–based Indigenous Lands Program (ILP), which was created in 2005 under the nonprofit Trees, Water & People to support Indigenous communities in preserving their lands. “For some families, it’s a major form of economical revenue for them when they sell their harvest and their crops in the fall time.”

Calabaza says that every year communities along the Rio Grande that depend on irrigation for their fields are having to ration water more and more, and that this has started causing tension among communities. “A lot of the communities downstream of Cochiti Dam are senior water right holders, and they have the first right to irrigate their fields. But communities in between, like Peña Blanca and Algodones, who are also big ag-producing communities, are facing a lot of those shortages and challenges because they have junior water rights.”

But Calabaza is optimistic that the work ILP is doing will eventually help resolve some of these issues. “If we can invest a lot of our knowledge and our science and man-power resources back into rehealing these watersheds, our water systems will improve,” he says.

Revitalizing the hydrological function of the watershed around ancestral locations and Pueblo communities post-fire is the ILP’s primary focus. This spring, they cohosted the 2025 New Mexico Tribal

Forest & Fire Summit in Mescalero, and in partnership with the Pueblos of Santo Domingo, Cochiti, and Jemez, they are about to launch an ongoing project to rehabilitate the Capulin Canyon watershed.

Another key project partner is High Water Mark, a company launched by hydrologist and engineer Phoebe Suina, of the Pueblos of San Felipe and Cochiti, in response to flooding in the Rio Grande Valley after the Las Conchas Fire. Since 2013, Suina has worked to support tribal governments and communities in post-fire and postflood watershed management and rehabilitation. ILP will also be collaborating with Ancestral Lands Conservation Corps, whose projects include habitat restoration programs for adults and youth.

This year, ILP and their partners will begin work on the canyon’s 2,200-acre headwaters, and they plan to use the project as a template for all of the adjacent canyons in the Jemez Mountains.

“What we’re trying to do is bring together that traditional ecological knowledge that exists and has survived years of colonialism and oppression, to combine it with the cutting-edge Western science that is coming out of academic institutions and research facilities,” says Calabaza. “We’re hoping that this project is also reconnecting people back to the land. The water, it’s a living thing, and we treat it as a living thing moving forward. There’s just so many intersectionalities between the conservation of water, language, community, resistance, farming, education, youth engagement and outreach, and the idea of

James Calabaza and Michael Martinez of Trees, Water & People, photo courtesy of Trees, Water & People.

August 1 - September 30, 2025

America’s Farmers Market Celebration™ (AFMC) is the only annual ranking of the top farmers markets in the United States as voted on by the public. Since 2008, the AFMC has highlighted the important role farmers markets play in communities across the nation while celebrating the farmers, staff, and volunteers who make markets happen.

intergenerational transfer of knowledge between elders and youth. Those are all factors that are going to be webbed into our project. But the very center of it is water. Water is life, and water brings people together.”

Watershed restoration work starts with planting trees, and Calabaza says they have planted more than 125,000 trees in the last five years, with about 85,000 of them in New Mexico. This fall, with the help of the Forest Service, Ancestral Lands Conservation Corps, Santa Fe Indian School, and others, ILP will begin planting 10,000 Douglas fir, ponderosa pine, and white fir trees in and around Capulin Canyon.

Having trees on the landscape is critical for watershed function, he says, because trees help protect the soil from erosion and control the underground movement of water to prevent fast runoffs. Farmers using the water downstream are impacted by the loss of trees in higher elevations because trees are instrumental in creating a canopy for snowfall that allows it to melt more slowly and better absorb into the earth and the watershed, something that becomes vital during the hot summer months.

“The trees are eleven months old that we’re planting back in this landscape, and it’s going to take a few years for them to acclimate,” says Calabaza. “We’re going to start also working on installing and building structures [in the canyon] that can help control some of the [runoff], especially after a really heavy rainstorm, because right now that water is just flowing very fast back into the Rio Grande. But if we’re able to stop and retain it, it’s going to just recharge that landscape. It’s going to seep in and infiltrate into the ground, and then hopefully, over time, naturally release through springs.”

ILP project manager Michael Martinez is from the Pueblos of Ohkay Owingeh and Jemez, and he says that the devastation from these human-caused wildfires is so bad that a new word needs to be invented to describe it. He says the area encompassing Capulin Canyon has been neglected, and now people’s livelihoods downstream are in jeopardy. He wishes someone had started revitalization work much sooner because of how long it takes for trees to grow and for nature to find its balance again.

“Now we’re probably fifteen years past everything, and now we’re getting into it, but it will take some time,” Martinez says. “But Mother Nature, she knows what she’s doing, and we just need that little push. That’s what we’re hoping, that once we get these structures implemented, that she can handle the rest on her own.”

Calabaza says they want to also create job opportunities for Indigenous communities and expose young people to conservation work as a possible career path. This underpins their partnerships with both the Ancestral Lands Conservation Corps and the Santa Fe Indian School, which offers a field-based agriscience class that gives students hands-on exposure to chemistry, biology, botany and ethnobotany, horticulture, and ecology.

“Natural resources–related work is seeing a decline in young adults or students coming into this field, so we’re trying to build activities and real-world opportunities for young Native Americans to participate in,” Calabaza says. “We have a partnership with Santa Fe Indian School where we’re going to provide volunteer days for middle school and high school students to come out to do some basic project activities like tree planting. . . . [E]ven though they might not want to do natural resource–related work today, they’re still going to have to take on responsibility in the future as the next stewards of our landscape, and carry on that generational knowledge that we’ve learned or has been passed through time.”

Phoebe Suina of High Water Mark LLC in a gully in the Capulin watershed, photo courtesy of Trees, Water & People.

IT TAKES A FOODSHED

BEHIND THE WHEEL WITH NEW MEXICO HARVEST

By Sophie Putka . Photos by Stephanie Cameron

It’s tricky to pin down just what New Mexico Harvest does— because when it comes to getting locally grown food onto New Mexican plates, they do it all. I get a taste of this over the course of a late morning at their small kitchen and processing facility in Albuquerque’s North Valley, where owner Thomas Swendson greets a local grower who’s dropping off crates of jewel-like tomatoes, demonstrates the sealing power of a machine that packages meals for schoolkids, and gifts me a selection of their prepared foods, wrapped in neat brown paper. It’s fitting that Swendson’s title on New Mexico Harvest’s website reads “El Presidente/Wearer of many hats.”

Yes, New Mexico Harvest runs a CSA (community supported agriculture) program, aggregating produce and meat from family-run growers and farmers, then distributing some 130 shares to members in their distinctive blue tote bags every week. But they also run an online farmers market with à la carte items; deliver local produce

wholesale to restaurants, grocery stores, schools, and senior centers; prepare ready-to-eat items in their commissary kitchen; and by 8 am each morning, make 450 meals for kids at thirteen nearby schools.

For Swendson, it’s all part of a family legacy. His stepfather, Steve Warshawer, started the company as Beneficial Farms CSA in 1994, delivering eggs and cheese out of his car from a loading dock in Santa Fe. Warshawer handed the business off to Swendson about a decade ago, and Swendson renamed it in 2020 to reflect the network’s expanding reach. At times, Swendson has worked as a commercial truck driver, pouring what he made into keeping the operation afloat. All five of his siblings have worked for New Mexico Harvest at one time or another, he said, and three still pitch in, along with his partner, Electra Kennedy-Hall, who has worked in most areas of the business and continues to write their weekly newsletter. Swendson’s mother, Colleen Warshawer, runs Ewe Matter Farm & Dairy, which provides lamb for the food hub.

Jon Agard off to deliver shares to New Mexico Harvest members.

“I’ve dedicated my life to try and highlight the work that these farmers are doing,” Swendson said, speaking of the more than eightyfive farmers that New Mexico Harvest works with over the course of the year. “It’s incredible. Our local food movement is unique.” Part of what makes New Mexico’s food system so robust, in his view, is how supportive local farmers markets are—both of generational growers and newcomers entering into agriculture.

Over the years, New Mexico Harvest has expanded their CSA program to include a customizable membership option and an online marketplace, where anyone can order locally grown or made items for home delivery in an area that spans from the Albuquerque metro area to Santa Fe. (CSA members get a 10 percent discount on à la carte purchases.) Offerings include classics like heirloom tomatoes, Swiss chard, red onions, and mung bean sprouts, but also newer, prepared items like their addictive pumpkin spice candied pecans, chewy apple pie fruit leather, green chile corn bread, and, most recently, delistyle meals like sandwiches and salads made with local fare including M’tucci’s focaccia and Tucumcari Mountain Cheese Factory feta. These prepared items are not only convenient but pivotal to the local food economy. “Our new commissary kitchen and food hub are equipped to process surplus crops, extend the life of seasonal harvests,

and reduce food waste,” a recent newsletter reads. “These efforts not only sustain our farmers but also build resilience in our food system.”

The marketplace option, on top of traditional CSA offerings and wholesale relationships with dozens of local businesses and institutions, can make for a dizzying weekly delivery system—meticulously planned and executed. Swendson reeled off daily pickup and distribution routes that reach as far as Dixon in the north and, in coordination with other regional food hubs, Las Cruces and Silver City in the south. Including volunteers and part-timers, just nine people make it all happen each week. As if this weren’t enough, the team adjusts their routines seasonally. “There’s a lot of complexity to it,” Swendson acknowledged.

Their participation in New Mexico Grown, a federally funded food-purchasing program whose aim is to provide fresh, locally grown food to children and older adults, takes New Mexico Harvest another step beyond the realm of a traditional CSA. It lets them act as a distributor for a broad network of midsize local growers, creating a values-based food supply chain and allowing schools and other institutions to rely less on food giants such as Sysco and Shamrock.

Meals being prepped for kids' after-school program.

Chef Bila Conchas

COVID-19 may have pushed New Mexico Harvest to focus more on delivery, but the ability to distribute local food more widely was ushered in, Swendson said, partially by the Food Safety Modernization Act, which put in place sweeping new food safety regulations, including for smaller food facilities. While it meant more stringent rules that could pose a challenge for small food producers (for example, food handling had to be moved indoors), Swendson said it also represented “a ‘between’ step for the very commoditized USDA regulations and these natural, local, organic movements of, not just the organic specifically, but trying to bring small-scale farmers to the bargaining table with the larger-scale [ones].” Swendson said their involvement with New Mexico Grown is a prime example of the lasting impacts of this transition: “Through going through those steps as farmers and our steps as a food hub, we can now sell directly to the institutions, whereas prior to the Food Safety [Modernization] Act, it was just—you had to be a big farmer.”

With the addition of the commissary kitchen two years ago, they also inherited a kids’ meal program—the one Swendson demonstrated

packaging for on my recent visit. The meals serve kids enrolled in afterschool programs run by Community for Learning, which provides support to low-income and at-risk children outside of school hours. It’s funded by grants from the state departments of health and education as well as the federal Department of Education. Recent threats to this department and cuts to the USDA have endangered New Mexico Grown and programs like it, Swendson said, but he’s hopeful. “The state is hugely behind it, and they’re going to find a way, I know they will.” Also uncertain are upgrades to their infrastructure—a flash freezer and dehydrator for prolonging the life of more food—that Swendson was hoping would be funded by a federal grant.

Still, there’s more in the works: Swendson wants to get New Mexico Harvest certified for jamming and pickling. Plans are underway to add more charcuterie boards, cookies, and other baked goods to the online marketplace. And, Swendson said, maybe soon he and his partner will add an even more personal contribution to the operation: pineapple and citrus fruits from a greenhouse in their own backyard farm.

505-585-5127, newmexicoharvest.com

Top left: CSA bags being loaded for weekly delivery. Bottom left: A large variety of local products available to New Mexico Harvest members. Right: El Presidente/Wearer of many hats, Thomas Swendson.

out and about WITH The Bite

FIELD NOTES ON A FEW PLACES TO EAT AND DRINK

Santa Fe’s Sassella, closed late last year in response to some plumbing issues, is never to reopen. Some voiced hope that Chef Cristian Pontiggia would follow the restaurant’s closure by at last opening his very own restaurant, but that is not to be. The good news is that, with his taking the role of executive chef at the Rosewood Inn of the Anasazi, you won’t have to wait for months of fundraising and planning in order to eat his food again.

Rustica Fresh Italian Kitchen closed not long after Sassella, but, incredibly, has already reopened as Piazza Caffè Leonardo Razatos, generational owner of the Plaza Cafè, and his husband, Giuliano Marcheschi, bought the venue in south Santa Fe in February, put up a circus mural and made a few other changes, then reopened with much of the same kitchen staff. Pasta is handmade and prices verge on bargain—just don’t call the grissini breadsticks.

George R. R. Martin continues to expand his influence in the “real world”: Next door to Jean Cocteau Cinema and

Beastly Books, you can now find Milk of the Poppy, an apothecary-style cocktail bar with slipstreamy, plum-colored seating from which you can sip grassy-hued cocktails, lychee fruit concoctions, and all manner of other artful libations, along with dishes featuring bone marrow, pea shoots, and flowers. Sokhang Pan, who charmed The Bite contributor Raven Del Rio when she interviewed him at Radish & Rye, is the head alchemist; Adam Garcia is leading the culinary team.

Hello Sweet Cream, the ice cream shop in La Tienda at Eldorado where you can find such flavors as Raspberry Rose (rose as in petals, although they remove those from the cream before churning it) alongside kid pleasers like peanut butter cookie dough, has opened a second location at CHOMP in Santa Fe.

After spending millions of dollars restoring the Plaza Hotel and the Castañeda Hotel, Allan Affeldt has decided to put both Las Vegas hotels up for sale. Affeldt has said that the hotels will operate as normal throughout the sale and that none of the staff will be impacted—although, after replacing Bar Castañeda when Chef Sean Sinclair resettled full time in Albuquerque, the Trackside dining room closed for the season last fall,

never to reopen, so you’ll have to dine elsewhere in town. The Skillet, perhaps?

On that note: Prairie Hill Café and Byron T’s Saloon, the restaurant and bar at the illustrious Plaza Hotel in Las Vegas, have closed their doors for good. Run by native Las Vegans Sara Jo Mathews and Ryan Snyder, Prairie Hill will be missed by tourists and local patrons alike, and will be remembered for—among other things—providing hot meals to evacuees and first responders during the Hermit’s Peak / Calf Canyon Fire. Mathews and Snyder have already teased their next Las Vegas project, though, which is actually a return to an earlier project: Borrachos Craft Booze & Brews. No further details yet, but we’ll keep you updated.

DWTNR Cocktail Bar & Lounge, the swanky cocktail bar and restaurant in the newly remade ARRIVE Albuquerque, held its grand opening in late February. (The hotel itself, formerly Hotel Blue, opened a week or so prior.) Our crew enjoyed a Big Bad John, a glass of Gruet, and some surprisingly satisfying shaved ice on a first visit; next time we’ll take a Mama Tried with some Mom-style tacos. They also do small plates and green chile smash burgers, and devote a corner of the menu to variations on the Boilermaker, sometimes known as the Indie Sleaze.

DWTNR Cocktail Bar & Lounge.

Sokhang Pan, photo by Raven del Rio.

The Skillet, photo by Douglas Merriam.

In March, Afghan Kebab House opened in the spot that used to be Knead Dough Bar (and, before that, Gold Street Caffe) in downtown Albuquerque. While we’re sorry we can no longer stop by to grab one of Chef Herrera’s doughnuts, kebab and qabuli palow are a welcome addition to the local lunch scene, as is the spirit of this new place.

Obviously that means Knead Dough Bar & Eatery is closed closed, but Knead Bakery is still taking orders. If you’re longing for one of those Potato Cake Doughnuts or like the idea of a Dubai Chocolate Croissant, follow them online to find out when orders go live.

For those who’ve been waiting for straight-up Ethiopian to come to New Mexico: Clay Pot Ethiopian Cuisine hosted the grand opening of their food trailer in February, and have since been popping up at breweries from Corrales to Nob Hill to downtown Albuquerque. Ethiopian vegetarian is among the best, but they offer meat dishes too, all served with tangy injera. May 3 they’re hosting a spring brunch in Placitas, and we hope it won’t be the last. As with all food trucks, check their social channels for current schedules. (ICYMI, Clay Pot has been running occasional classes and doing catering around town for a while, to much joy and acclaim.)

What was MÁS is now Char, opened March 20 in the revamped restaurant space at Hotel Andaluz in downtown Albuquerque. They’re talking live-fire cooking and spins on New Mexican, with the upstairs bar styled for the Prohibition era.

New downtown Albuquerque brunch spot Smothered is now fully opened, and our sources report that we must get there soon, and to order the chicken and waffles.

The 377 Brewery in Albuquerque is also shutting its doors. Co-owners Cliff Sandoval and Fred Atencio opened the place in 2016 on the corner of Gibson and Yale, meaning it was the first stop for New Mexico beer for folks flying into the Sunport.

One of Albuquerque’s most beloved Chinese restaurants has shuttered: Budai Gourmet Chinese served its last meal in late February. Returning there to eat duck had been on our to-do list all winter, and their closure has offered incentive to get to the rest of the places we love, be they Chinese or Italian, while they are still here.

Down in Mimbres, where dining-out options have long been limited to the Living Harvest Bakery, a.k.a. Three Questions Coffee House, and the Log Cabin Restaurant, there’s a new spot:

Oluv. Located in the old Mimbres Cafe on NM 35, their menu is American, meaning it’s all over the map. Per the Silver City Daily Press, one of the chefs (also a co-owner) grew up in Louisiana, which explains the Southern leanings of their Sunday brunch menu.

On March 27, the Street Food Institute cut the ribbon on its newest project: the Barelas Community Kitchen, at Fourth Street and Barelas. The community kitchen will provide job training, a food business incubator program, and affordable commercial kitchen rentals for small food businesses.

Sadly, edible New Mexico’s Burrito Smackdown has been postponed to 2026, due to predictions of record heat this June. However, tickets for the Green Chile Cheeseburger Smackdown go on sale July 1—an event that always sells out, usually over a month before it actually goes down. (VIP tickets sell out even faster, so you might want to set that calendar reminder now.)

Stephanie Herrera of Knead Bakery, photo by Ungelbah Dávila.

Char in Hotel Andaluz.

Green Chile Cheeseburger Smackdown.

Stay Local, Discover New Mexico

SIP / SAVOR / SPA / SWIM SUMMER STAYCATION

As we celebrate 20 years of effortless escapes, we invite you to indulge in the ultimate summer staycation. Relax by our tranquil pools, savor local dining, and enjoy the unique charm of each of the destinations we call home—Taos, Santa Fe, Albuquerque, and Las Cruces. Your ideal getaway is closer than you think. New Mexico residents enjoy exclusive savings with a valid state ID. Enjoy up to 20% off with Code: SUMMER25 when you visit HeritageHotels.com.

EDIBLE INGREDIENT

Tomatoes

Let’s face it: At some point in the near future, our kitchen counters will hit a crescendo with tomatoes spilling out of bowls, from cherries to zebras, and Romas to beefsteak. Whether they are coming from the garden, the farmers market, or the co-op, we can’t help but hoard tomatoes like we will never see them again. In preparation, we are arming you with a handful of super-quick recipes inspired by New York Times Cooking to help you make good use of them before you begin canning and freezing them to savor year-round.

Photo by Stephanie Cameron.

TOMATO YOGURT DIP

Sliced crusty bread

Extra-virgin olive oil

1 garlic clove, peeled

2 cups Greek yogurt, full-fat

1 large ripe tomato, halved horizontally (any variety)

Salt and black pepper

Brush bread with olive oil and toast under the broiler or on the grill. While bread is still warm, rub slices with garlic clove. Add yogurt to a shallow bowl and spread into an even layer. Using a box grater, grate cut sides of the tomato on top of the yogurt and discard skins. Season with salt and pepper and serve with the toasted bread for dipping.

TOMATO TOAST WITH CHEDDAR MAYO

2 medium tomatoes, thinly sliced

Flaky salt (or smoked sea salt)

1/2 cup mayonnaise

1/2 cup (packed) white cheddar, finely grated

4 slices rustic bread

Arrange tomatoes on a plate and sprinkle with salt. Stir together mayonnaise, cheddar, and a pinch of salt. Toast

bread using whatever method you like. When the bread is hot and ready, slather on the cheddar mayo. Top with tomatoes and serve.

BAKED EGG WITH TOMATO

Butter, as needed (or oil of choice)

1 slice tomato (any large variety)

1 small slice prosciutto or other cured meat (optional)

1 egg

Flaky salt and freshly ground black pepper

Shredded basil and/or parmesan, for garnish (optional)

Heat oven to 375°F and position rack in the middle. With a paper towel, wipe a bit of butter into a ramekin or other small oven-proof dish that holds 4–6 ounces. Place a tomato slice in the bottom and then a slice of prosciutto. Break one egg into ramekin and place on a baking sheet. Bake for 10–14 minutes, or until egg is set and white has solidified. The egg will continue to cook after you remove it from the oven, so it is best to undercook it slightly. Sprinkle with salt, pepper, basil, and parmesan.

*Sourcing note: La Montañita Food Co-op carries local tomatoes at all their locations when in season.

Paletas

ICE POPS TO BEAT THE SUMMER HEAT

Words and Photos by Stephanie Cameron

Popsicles evoke carefree childhood days. I remember bright, neon colors dripping down my fingers as I stood beside the ice cream van blaring its weird pied piper music during hot summer vacations. Unfortunately, as an adult who’s just a little more attuned to the subtleties of flavor than my childhood self, I find that most store-bought Popsicles disappoint—they’re loaded with excessive sugars and artificial ingredients and often priced beyond their worth. You don’t have to settle for these subpar sweets when you make ice pops or paletas at home. Paletas, made with natural ingredients, are slightly more sophisticated than those Popsicles of yore; with flavorful chunks of fruit, nuts, or herbs dispersed throughout the treat, textures emerge to chew through as the ice pop melts in your mouth. The paleta recipes in this edition of Cooking Fresh are meant to spark your creativity—whether you opt for water and fruit juice–based (paletas de aguas), cream-based (paletas de crema), or some boozy versions (see page 72), the possibilities are unlimited.

Here are some general guidelines for creating your own paletas.

• No Popsicle mold? Substitute Dixie cups, individual yogurt containers, muffin tins, or ice cube trays. To get the sticks to stand upright in these unconventional molds, tightly wrap the top of the mold with aluminum foil and poke your Popsicle sticks through the foil.

• To alleviate spills when freezing and because pops will expand when they freeze, don’t fill molds to the very top—leave a 1/8-to-1/4-inch gap at the top of each cup. This gap will also leave room for topping when desired.

• Ingredients lose flavor when they freeze, so the puree should have an intense, sweet flavor—even more so than you might expect.

• Add cornstarch to cream-based pops to make them creamy and not icy.

• Honey is an excellent sweetener for homemade Popsicles because it has a delicate flavor and prevents ice crystals, making for a creamier texture. Agave syrup can yield similar results.

• Amplify the flavors of ingredients by roasting them.

• Create layers of texture by including whole pieces of fruit, or add a nutrient boost with bee pollen, chia, hemp, and/or flax seeds.

• Freeze paletas for 6–7 hours, preferably overnight, and until they are completely frozen through.

• To remove the paletas, run the mold under warm water for a few seconds to loosen them.

Agua de Jamaica Paletas

These pops are a refreshing burst of tartness with a subtle hint of floral goodness. The jamaica (hibiscus) petals imbue their bright, ruby-red hue with a punch of tanginess that puckers your lips and keeps you longing for more. If desired, add another splash of color with fresh mint leaves.

Makes 8–12 ice pops

4 cups water

1/2 cup dried jamaica flowers

1/2 cup honey or sweetener of choice

Juice of 1 lime

1/2 cup mint leaves, plus more for garnish (optional)

Rinse and drain dried jamaica flowers in a large colander. Bring water to a boil in a large pot. Add flowers and mint (if using), and cover with a lid. Remove from heat and steep for 20 minutes.

Strain jamaica water into a pitcher and discard flowers. Add honey and stir. Taste tea, and add more honey or dilute with water to your liking; just keep in mind that some flavor will be lost as the paletas freeze. Refrigerate until cold. Push 4–5 mint leaves (if using) to the bottom of Popsicle molds and fill with jamaica tea. Snap on lids, insert Popsicle sticks, and freeze until solid, for 6 hours or overnight.

Balsamic Roasted Cherry Pops

Adapted from Rachael Bryant, Meatified

My ultimate sweet treat is vanilla ice cream with strawberries and balsamic, so when I stumbled across this recipe, I knew it would be magic with Monticello’s balsamic condiment. You can make this recipe vegan by swapping agave for honey.

Makes 8–12 ice pops

1 1/4 pounds dark sweet cherries, pitted and divided

3 tablespoons high-quality balsamic vinegar

3 tablespoons honey

1/4 teaspoon fine sea salt

1 2/3 cups unsweetened coconut milk, full-fat

2 teaspoons cornstarch

Unsweetened shredded coconut

Preheat oven to 400°F. Place 1 pound of cherries in a baking dish and drizzle them with the balsamic vinegar and honey, then sprinkle sea salt over the top. Roast for 35 minutes, stirring halfway through the cooking time, until cherries have released their juices and just begun to wrinkle a little.

Allow cherries to cool slightly, then transfer to a blender, making sure to scrape up all the pan juice too. Add the coconut milk and cornstarch and blend together. Taste and add additional honey or salt, if needed.

Cut remaining 1/4 pound of cherries in half; add to the Popsicle molds, and fill with cherry mixture. Use a skewer or chopstick to break up any air bubbles in the mixture, leaving a gap at the top of each mold for adding shredded coconut. Pop the molds into the freezer for 30 minutes.

Remove from the freezer and sprinkle the top of each mold with the shredded coconut, then snap on the lid and slide Popsicle sticks into each carefully. Return to the freezer and freeze until solid, for 6 hours or overnight.

Chocolate-Coco Paletas

These paletas can be made with Oaxacan chocolate or high-quality local chocolate such as Eldora in Albuquerque or Chokolá in Taos. Experiment with single-origin bars and flavored bars like Eldora’s Chili Blast. This recipe makes use of avocados on the edge. When too soft for slicing and too brown for guacamole, they can be an excellent substitute for butter and add creaminess to vegan recipes.

Makes 8–12 ice pops

3–4 ounces chocolate, broken into pieces

2 cups unsweetened coconut milk

1/2 avocado, ripe or overripe

2 tablespoons agave syrup

2 teaspoons cornstarch

Bring coconut milk to a very gentle simmer over low heat. Add chocolate and agave, and stir with a whisk or molinillo until chocolate has dissolved. Pour into a container and let it cool completely in the refrigerator or freezer. Put chocolate mixture, avocado, and cornstarch in the blender, and puree until smooth. Pour into Popsicle molds, snap on lids, insert Popsicle sticks, and freeze until solid, for 6 hours or overnight.

Thai Tea and Cheese Foam Paletas

Cheese foam originated in Taiwan and quickly gained popularity in East Asia before reaching the United States. Adding cheese foam topping to iced coffee or tea drinks takes your beverage experience to the next level, and the same goes for these paletas.

Makes 8–12 ice pops

Cheese Foam

4 ounces cream cheese

1/2 cup heavy whipping cream

1/4 cup sweetened condensed milk

1/4 teaspoon sea salt

Thai Tea

4 black tea bags

2 cups water

2 teaspoons vanilla extract

2 star anise pods

3–4 black cardamom pods, cracked open

1 cinnamon stick

1/4 piece vanilla bean pod

2 teaspoons turmeric, ground

2 tablespoons sugar

1/4 cup sweetened condensed milk

2 tablespoons evaporated milk or whole milk

Cheese Foam

Set up a stand mixer or large mixing bowl and hand mixer. Add cream cheese and beat on high until smooth and creamy. Add heavy whipping cream and condensed milk and beat until the texture starts to foam up into soft peaks. Add sea salt a pinch at a time and adjust to desired taste. Continue mixing until you reach a light and airy mousse-like consistency. Be careful not to overmix; stop before you have the firm peaks characteristic of whipped cream. Pour into a piping bag. Set aside in the refrigerator.

Thai Tea

Place tea bags, water, vanilla extract, star anise, cardamom, cinnamon stick, vanilla bean, and turmeric into a medium-sized pot and bring to a simmer over medium heat. Reduce the heat to low and continue to simmer for 3–5 minutes. Strain tea mixture and place in refrigerator to cool.

In a large bowl, whisk sugar, sweetened condensed milk, evaporated milk, and cooled tea until thoroughly combined.

Assembly

Pour Thai tea 1/3 of the way up the Popsicle molds. Then pipe in cheese foam, creating a layer about 1/4-inch thick. Continue layering until the mold is nearly full. Snap on lids, insert Popsicle sticks, and freeze overnight.

Forty-Eight Hours in Puebla

Words and Photos by Stephanie Cameron

Arriving in the city known for mole poblano, chiles en nogada, and Talavera pottery, I was surprised by the dichotomy of modern and colonial-era architecture. Despite the many department stores in Puebla today, the zócalo, the main square, remains the city’s cultural, political, and religious center and was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1987. Many downtown buildings incorporate glazed, decorative Talavera tiles, introduced by early residents from Spain. The cuisine, as I discovered, is also not limited to the stuff of colonial legend: Puebla’s chalupas, tacos dorados, tacos árabes, cemitas poblanas, and molotes are all must-trys.

Sabor a Puebla: CHALUPAS

In the heart of Puebla’s historical district stands an old fountain, which serves as the centerpiece of the lively zócalo. This vibrant gathering place, surrounded by notable buildings such as City Hall, the Casa de los Muñecos, and the Basilica Cathedral of Puebla, is ideal for people watching. You can relax and enjoy the view from the patio of one of the many adjacent bars and cafés that look over the zócalo. At Sabor a Puebla, chalupas served in sets with salsa verde,

salsa roja, and mole poblano were perfect for sharing while drinking cerveza and watching the barrenderos (street sweepers).

Clementina Cocina Poblana: CHALUPAS and TACOS DORADOS

Eating chalupas only once on my trip wasn’t an option. This quintessential Pueblan street food, closer to a light tostada than what often passes for a chalupa in the United States, is essentially a corn tortilla fried in lard, bathed in salsa, and topped with shredded pork or chicken, onions, and sometimes a sprinkling of fresh cheese. At Clementina, I paired my chalupas with tacos dorados: crispy, golden corn tortillas filled with chicken and potatoes, served with sour cream and cheese (and, of course, table salsas). Clementina is situated on the Street of Sweets, known for its forty dulcerías, so be sure to save room for dessert. I went with the strawberry tres leches cake at Dulceria Dos Hermanos.

Mezcalería Míel de Agave: ESQUITES and MEZCAL

“Mezcaleros somos, y en el camino andamos” is the phrase scrawled in neon on the wall of Míel de Agave which reflects the passion

and spirit of this space. The proprietors may not produce mezcal, but they’re all about honoring the culture and diversity of mezcal. My dinner companions and I ordered four flights (twelve tastes) of mezcal and several dishes to share. The esquites, a creamy corn dish prepared with mayonnaise, chopped chile poblano, epazote, cheese, and salsa macha, was a highlight for me, as well as the Candinga Papalometl mezcal. From the food to the cocktails to the service, Míel de Agave delivered an exquisite taste of Puebla.

Dahlias

Petunias

Chile Basil

Cape Daisy

Heirloom tomatoes

Finished Water, 2025, gouache on paper.

DRINKING WATER IN ALBUQUERQUE

A TOUR FROM RIVER TO TAP

Words and Illustrations by Erin

Elder

Chances are you’re reading this article with a glass of water nearby. Chances are you have sipped from this water in the last few minutes and may sip some more while reading. Chances are, if you use municipal utilities, drinking water is not something you think much about, despite the fact that you do it many times every day of your entire life.

If you live in the United States, chances are that, thanks in part to the Safe Drinking Water Act, the water coming from your tap is safe to drink. Whether you filter your water or drink it straight from the faucet, you can, in most parts of this country, trust that tap water will not kill you. Thanks to the governance of American water since 1974, you are not likely to get cholera or dysentery or any number of diseases that could be contracted by drinking water in many other parts of the world; nor, with rare exceptions, are you likely to be poisoned by lead. You may know and appreciate this. But how does drinking water get to the tap? Where does it come from and how does it work?

Curious about such things, I recently toured the San Juan–Chama Drinking Water Treatment Plant, which is responsible for cleaning the majority of the water we drink in Albuquerque and Bernalillo County. The tour was led by Cassia Sanchez, the plant’s chief engineer, who met me and a few others in the visitors’ lobby. We gathered around a roomsized 3D model of the city’s water system; after donning hard hats and protective glasses, we walked out into the warm afternoon sun.

Opened in 2008, the plant is a sprawling complex of pools and piles, trucks and storage tanks, whirring buildings, winding staircases, metallic smells, and color-coded pipes. Encircled by chain link and razor wire, the plant is run twenty-four hours a day by thirty-three full-time operators who control every aspect of the system through a closed network of cameras, screens, sensors, mechanisms, and monitors. Solar panels adorn employee parking structures to provide 20 to 30 percent of the plant’s electric power. Currently serving 680,000 people, the plant produces 50 to 60 million gallons of clean drinking

water each day of winter and, the river permitting, twice as much during summer months. It took four years and $160 million to build this facility. Considering the long history of humans drinking water in Albuquerque, the plant is expensive, high tech, and new.

People have lived along the banks of the Rio Grande for twelve thousand years and while its water has long been used for crops, the river, which has always been brown with silty sediments, has never been good to drink. Ancient people collected drinking water from intermittent springs and rain, storing it in clay vessels. Spanish colonists built acequias to channel river water for irrigation, but dug wells for drinking. The city’s twentieth-century water system was entirely supported by wells drilled into the underlying aquifer. For decades, it was believed that these groundwater deposits were massive, that they held as much water as Lake Superior and would never run out. But by the 1990s, it became clear that the Albuquerque aquifer—a fraction of its imagined size—was being depleted at an unsustainable rate.

Meanwhile, New Mexico had been bolstering its water supply for irrigation and, through the 1948 Upper Colorado River Basin Compact, the state received rights to water from the San Juan River’s smaller tributaries: the Navajo, Little Navajo, and Blanco rivers. Because these rivers flow on the other side of the Continental Divide, a system of diversion dams and tunnels was built in the 1970s to move the water under the mountains and into the Rio Grande watershed. This imported water travels underground for twenty-six miles before joining up with the Chama River near its headwaters. Moving through a number of dammed reservoirs, the water eventually mixes with the Rio Grande and flows into New Mexico’s largest city.

The earth naturally filters groundwater; there is no need to purify it for drinking. But, with Albuquerque’s population growing and the aquifer shrinking, and with the San Juan River waters successfully delivered into its watershed, drinking river water became a twenty-first century imperative. It just needed to be cleaned.

Pipe Room, 2025, gouache on paper.

If you have visited the Bachechi Open Space or walked the river just south of Alameda, you have likely seen the site where much of Albuquerque’s drinking water is drawn. There, a small inflatable dam stretches across the Rio Grande, diverting water into two mechanized structures on the east bank. That water flows into a large pump house designed in the style of a Spanish mission, then travels seven miles underground to the surface water plant where it is treated by Sanchez and her team.

“We treat every bit of water, and then we re-treat it,” Sanchez commented as she led us in and out of the plant’s many buildings. But what does that mean?

Water treatment is a technical process that begins with the removal of sticks, rocks, trash, and other debris that settles to the bottom of two huge storage ponds. Then the water begins its dizzying journey through columns and pipes and refinements, including the addition of ferric chloride, which bonds with tiny particles and settles out from the clarified water. Liquid ozone is pumped through the water to kill

viruses and bacteria, and lyme is used to control its pH; a foot of sand and five feet of granulated carbon filter out any remaining toxins. Tiny bits of chlorine and fluoride are added to the water and once it is finished, the water is divided into reservoirs destined for the east and west sides of the city. Massive pumps move water uphill to large holding tanks, where it is then gravity-fed into individual homes and businesses through three thousand miles of underground pipes. Six hundred employees are responsible for the distribution of drinking water, working around the clock to ensure that whenever you turn on the tap—whether it’s to drink or to water your lawn—clean water comes out.

As we moved through the plant, climbing metal stairwells and peering into stories-tall pools, Sanchez shared ways that the plant is continually evolving as the team responds to new realities. One building held pallets piled high with LED lights that would soon replace less sustainable halogen bulbs. Outside, several large tankers were ready to transport stopgap emergency water to neighboring communities such as Las Vegas or the Navajo Nation, places that need clean

drinking water when their wells become contaminated or run dry. Other forms of responsiveness were less visible, like the discussions and proposed plans about how to deal with PFAs and microplastics, which are increasingly present in water everywhere.

Standing in the shadow of a large storage tank, Sanchez told us how the surface water plant, designed to protect the depleting aquifer, has shut down every summer since 2020 because the river has not delivered enough water to serve the city as well as people and places downstream. This means that if you drink a glass of tap water at a Nob Hill restaurant in July, you’re probably drinking groundwater. Now the city’s water comes from a combination of both systems— which, when needed, can switch back and forth in the course of mere hours or days.

Meanwhile, the Colorado River Compact will expire in 2026 and is currently being renegotiated by elected officials from seven western states and thirty tribes. This extremely difficult compromise, already swollen with the uncertainties of climate change and population booms, is being overseen by the newly reduced Bureau of

Reclamation. Forty million people depend on Colorado River water and these careful agreements about how it is used, moved, measured, valued, and cleaned.

I know that our bodies are 60 to 70 percent water and that water comes from specific places, but now, having toured the surface water plant, I recognize that we are ambulatory reservoirs, each made up of different water collections. Sipping from my glass, I imagine the journey this particular drink has taken. Can I taste the spring snowmelt in those San Juan River tributaries? Is the influence of Rio Grande water palpable? Or has this water come partly from the aquifer? Does it bear traces of the local storage reservoir from which it traveled to my home? Does the cumulative distance traveled somehow flavor these waters? Do the machines and chemicals and pipes and pumps? Do the laws and compacts and evolutions in technology? The countless hours of human care?

Feeling the confluence of my body’s waters meeting everything contained in each new gulp, I sip and sip again. Once emptied, I walk to the kitchen, turn on the faucet, and refill my glass.

Plant Pool, 2025, gouache on paper.

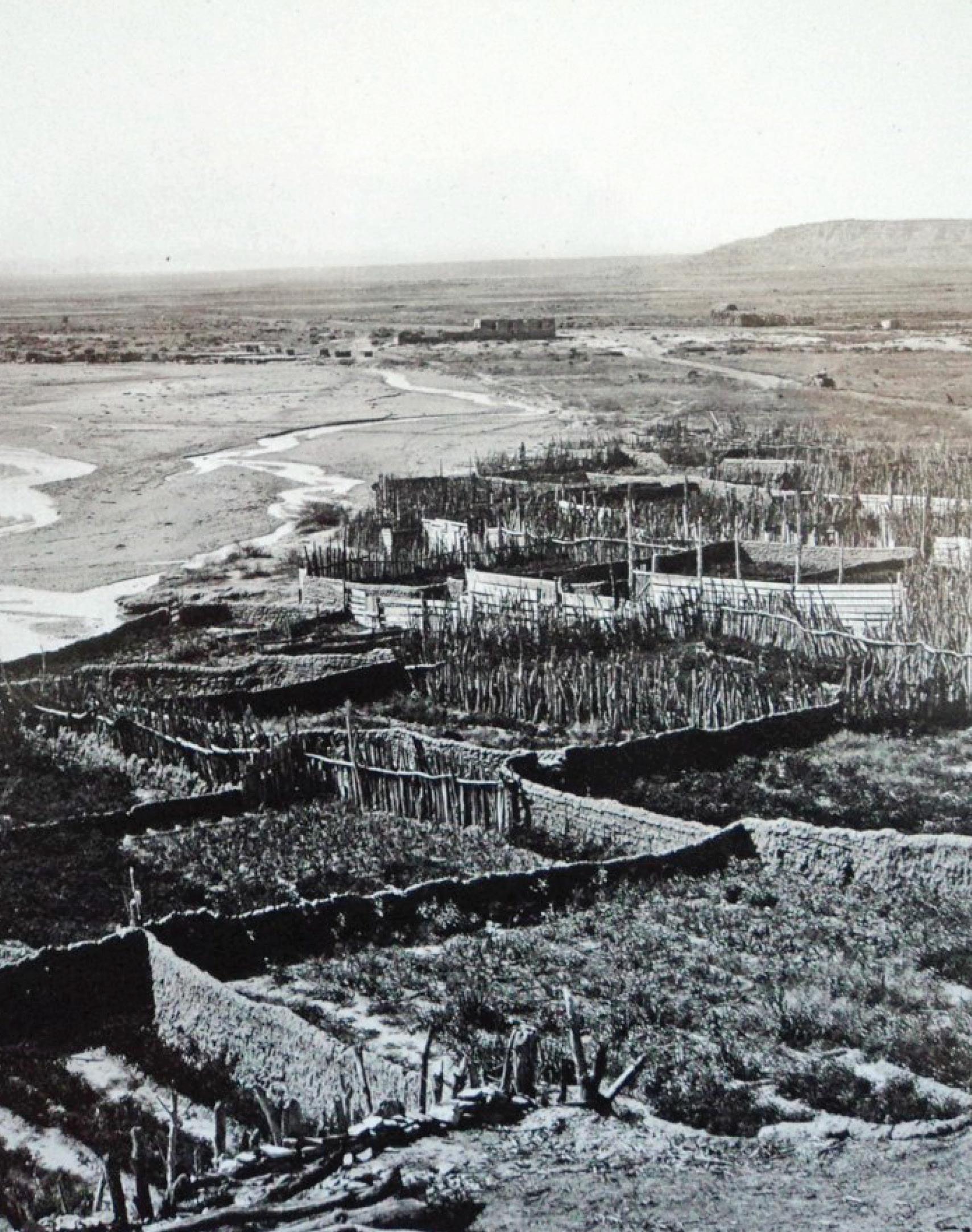

THE ONCE AND FUTURE RIVER

FROM BUCKETS AND BARRELS TO TANKS, THE WORK OF PRESERVING TRADITIONAL INDIGENOUS FARMS AND RECOVERING SACRED RIVERS IN A

By Sarah Mock

DRIER NEW MEXICO

Traditional Zuni olla water jars, painted by Eileen Yatsayte and Noreen Simplicio, serve as rain catchment vessels at Ho’n A:wan Park in Zuni and supply water for the Zuni Youth Enrichment Project community garden, photo courtesy of Zuni Youth Enrichment Project.

For James and Joyce Skeet, farmers at Spirit Farm near Vanderwagen, when water doesn’t come from the sky, it comes from a truck.

“We’ve collected seven or eight thousand gallons of water since last year,” James explains, “from the Little Sisters of the Poor.” This organization, which runs a Gallup-based assisted living facility, is not supplying water from the tap but from their roof. A three-thousand-gallon tank (about twelve feet high, six or eight feet across) set up outside the Little Sisters’ Villa Guadalupe collects water from the roof and gutters when it rains, and stores it until the Skeets can haul the water from Gallup to their farm miles away.

Eight thousand gallons may sound like a lot, but on Spirit Farm, where chickens, pigs, cattle, Navajo-Churro sheep, and many gardens grow year-round, it will last about a month, and more water is always needed. Surface water from rivers is not an option, given that in a good year, only four small rivers flow in the entirety of the nearly six-thousand-square-mile county where the farm is located. A well isn’t an option either, because the Skeets’ farm is on Chichiltah Chapter lands of the Navajo Nation and securing permission from the multiple bodies required to drill a water well on tribal lands involves a long, bureaucratic, and very costly process that can take years to complete.

Spirit Farm is not alone in this challenge. Across the Navajo Nation, a third of all households and families don’t have access to

running water, due to lack of municipal infrastructure and difficulties with drilling wells. Families without running water to their homes or farms must haul water for drinking, cleaning, and all other uses, usually from nearby municipalities.