• John Maynard Keynes

• Note from the Heads

• Understanding & Addressing the ‘Gender Pay Gap’

o Christian Ruiz

• What are the ‘PIIGS’ and where are they now?

o Eleftheria Sermpeti

• Is GDP becoming Anachronistic?

o Philip Manipadam

• The Psychology Behind Pricing

•

o Malak Ibrahim

• Margaret Thatcher and Friedrich Hayek

o Antara Kashyap

• Sir Jim Ratcliffe

o Diren Kumaratilleke

• Privatisation of public services – solution or problem?

o

• UK Spring Budget 2024: Impact on the Economy

o

• Yield Curve inversion crystal ball and what it tells us about an economy

o

Kondas

o Kaila

Niza

Soccernomics Book Review o Milo Peters

Saudi Arabia’s Economic Diversification o Kareem Mahmood

The UK Recession and what it means for Sunak’s government

Anna Zaman

•

•

o

• The Downfall of the Japanese Economy

Shyan Ann Teoh

Karan

Maliekkal

Oliver

Locke

Seminars 1 2 3 4 - 6 7 - 8 9 – 10 11 – 12 13 – 14 15 – 16 17 – 18 19 – 20 21 – 22 23 – 24 25 – 27 28 – 29 30 – 31 32

• This Term's

2

Ramadan Kareem!

This term has been amazing in terms of engagement and interest. We have had some incredible speakers – both from in school and out – and we look forward to welcoming many more in Term 3, after Ramadan. Keep in mind that the DKS Team has just launched the Ramadan Essay Competition!

We continue to be moved by the widening interest in Economics outside of the GCSE and A-level course, and continue to thank each and every one of you involved in the sessions.

We reiterate our thanks to Mr. Christopher, who gives us his unwavering support and guidance.

Look out for what next term has to come!

If anyone has speech ideas to organize or has written any economics–related essays for competitions, please do not hesitate to work with us and contact dks@dubaicollege.org.

Keep up the positive attitudes, the dedication to the society and above all the love for economics!

- The DKS team (Eleftheria, Christian and Philip)

3

Understanding & Addressing the ‘Gender Pay Gap’

Christian Ruiz

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences was recently awarded to Claudia Goldin, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics at Harvard University and Co-Director of NBER’s Gender in the Economy group, for “having advanced our understanding of women’s labour market outcomes”.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics monthly job report, labour force participation rate for women reached 77.8% in 2023 (an all-time high). Nevertheless, women “earn 77 cents on the dollar for doing the same work as men (0.77:1.00)” (Obama, 2014). The popular value, which Obama referred to, can be misleading as it relies purely on the ratio of the difference between women’s median earnings versus men’s median earnings (23 cents). This gap can go in either direction: if including part-time workers it widens to 27.6 cents, however, if we were to look at hourly wages across the USA, alone, it would narrow to 14 cents (Kessler, 2014). As shown, this is ultimately dependent on the methodology and there are many issues with outlining any one value as the face of such a large-scale complication.

Economists use data, and account for differences in “productive attributes” and still get a number that’s less than the 1:1 ratio (Goldin, 2016). Realistically, the issue at hand should not simply be discarded as a lack of “equal pay for equal work” and, although possibly the case in certain situations, overt pay discrimination is ‘by and large’ difficult to identify as one of the most significant factors (Goldin, 2016). It is difficult to find actual evidence of firms discriminating now compared to the 1930s when certain firms claimed they “do not hire women”.

However, this is not to say that the playing field is equal in the labour market. One finding is that women are reserved when negotiating salary offers (Bowles, 2014). The “social cost” of negotiating for higher pay is greater for women as opposed to men – found to be nearly insignificant for men (Bowles, Babcock, 2014). This shows that such reservedness is caused by the social environment, where women want to make a good impression but acknowledge that advocating for higher pay puts them in a socially difficult situation. For

4

example, actress Jennifer Lawrence blames herself for poor negotiation as she “didn’t want to seem difficult” when agreeing to her cut of the American Hustle’s profits – she was paid around 7% compared to Bradley Cooper and Christian Bale’s 9% (Smith, 2022).

Another significant finding was discovered when investigating the “impact of ‘blind’ auditions on female musicians” (Orchestrating Impartiality: Goldin, Rouse, 2000), when observing the employment within the USA’s symphony orchestras. There’s recently been a change in the audition procedures of symphony orchestras, adopting “blind” auditions, involving a “screen” which conceals the candidate’s identity – a test for sex-biased hiring. “Using data from actual audition”, with access to the names of individuals and their “blind” and not “blind” auditions across different orchestras, the research discovered an explosion in women auditions. Furthermore, when isolating the effects of blind auditions, their importance was outlined, as the top 5 orchestras had under 5% women in the 1970s and this value increased to over 25% by 1980, due to blind auditions. Interviews are difficult to arrange, having to travel and cover expenses to put your pride on the line, hence this finding highlights an ‘opportunity gap’ in the gender sphere which is very difficult to address.

Some of the best studies of the gender pay gap, which follow individuals longitudinally, show that right out of college wages tend to remain similar (the previously discussed categorical assumption of men being ‘better negotiators or competitors’ is unrecognizable). However, further down their life (10-15 years) far larger differences in pay begin to show up along with increasing differences in where they work and work titles/ ‘positions in the corporate ladder’. The majority of this happens within a year of the birth of a child and the impact on earnings is far greater for women than men.

The “care penalty” is the main driver of gender inequity, because temporal flexibility is seen to incur a huge cost (Anne Marie Slaughter, Unfinished Business) – unmarried women with no children continue earning closer to what men do. The birth of a child often results in the requirement of working flexibly and often part-time work, plus slower progress with tasks which results in slower promotions and growth in earnings. The data shows a very clear split, where women are often the ones searching for jobs with different amenities e.g. flexible hours, working from home or jobs with looser workloads. In many cases, such jobs contain the same total workload, however firms, especially in corporate and finance, value your availability and want to always have you at reach. In comparison, occupational segregation (differences in the jobs women tend to take as opposed to men also impacts earnings) barely competes, where if you were to give women the distribution of male occupations, you’d only wipe out ¼ of the gender pay gap (Goldin, 2016). Care tax is therefore often referred to as the “glass ceiling”.

5

When trying to address such a large-scale issue, it must be broken down into a set of smaller questions that can be answered with data. Essentially, women aren’t being paid the famous 0.77:1.00 ratio for the same work but are often doing different work or work with greater flexibility. Although this may seem a self-inflicted wound, these decisions today are set up in a way where they aren’t really optional for women. Goldin states that there are three main ways of addressing the issue: “fix the women (more competitive, better negotiators etc.), fix the men (resocialise to better understand the family role, having fathers bond and take more responsibility over kids) or fix the organisations and jobs”. Anne Marie Slaughter believes that if men leaned out more, the world would be a better place for women and is certain of the need for resocialisation, to the point where men say, “that’s my issue as much as it is my wife’s issue” (Slaughter, 2015). This has ultimately been pursued in various countries, for example, through the presence of parental leave. However, Goldin argues that it is easier/lower cost to try to lower the cost of temporal flexibility over time (regarding organisations and legislation), than to pursue sole resocialisation. One such suggestion is changes in public preschools with longer school days and years, to lighten parents’ demands at home. Also, Goldin believes in working to ensure firms offer more predictable hours and more flexibility, regarding where and when work is done – this can be achieved by making it easier for workers to substitute one another.

Recommended Reads:

- Unfinished Business: Women, Men, Work, Family by Anne Marie Slaughter

- Freakonomics Radio: The True Story of the Gender Pay Gap (Season 5, Episode 18)

6

What are the ‘PIIGS’ and where are they now?

Eleftheria Sermpeti

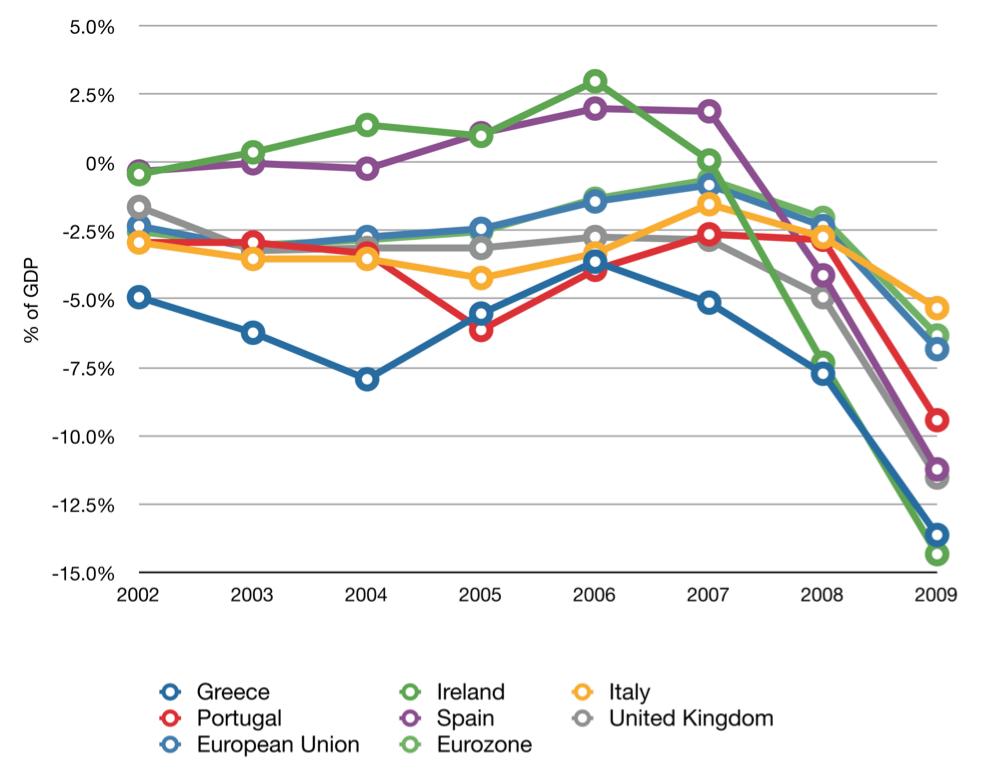

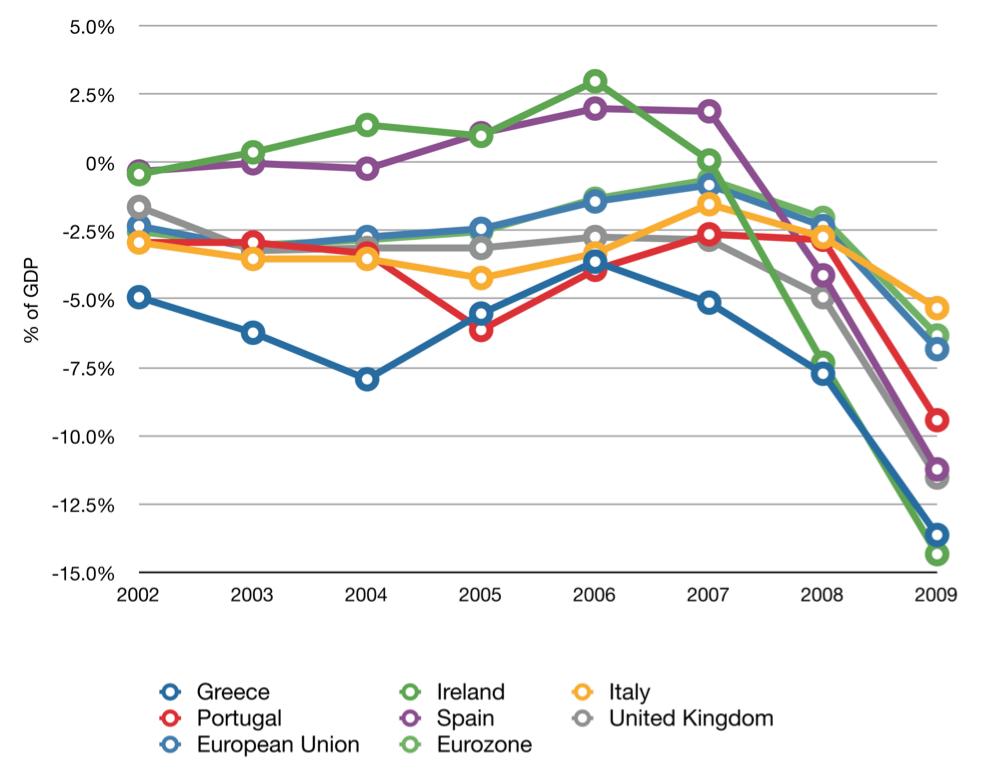

The ‘PIIGS’ – Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain. These countries were the ones blamed for the slow recovery in the Eurozone following the 2008-2009 financial crash due to their unprecedented mountainous debt levels. The reason these countries struggled so much with this was due to ultra-low interest rates in the early 2000s, meaning they borrowed excessively. Then, once the shock of the Financial Crash struck, they were underperforming and ultimately were unable to fund the debt they were in.

After France and Germany provided massive bailout money for Greece, and then also Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus, these economies recovered in very different ways.

Portugal: after a period of decades of austerity which was not bringing about growth, and in fact kept them in recession for over 3 years, they relaxed measures and boosted spending and investment – this is what got them out of the slump. Throughout this process, they had both IMF and EU support to be able to fund the changes until they got back on their feet.

Today, the Portuguese economy is on a slow upwards path – following a trough of -0.2% GDP in Q3 of 2023, they followed on with growth of 0.8%. The forecast for the rest of 2024 on average is growth of 1.2% and for 2025 is said to be 1.8%. So, it is reasonable to argue that Portugal is following a general trend for most European countries today and has come out of the misery of the 2010s.

Ireland: After the crash, Ireland recovered relatively quickly – gaining growth of 4.8% in 2014. Following on, the economy kept going on the positive trend of growth – growing 6.7% in 2015, and unemployment decreasing rapidly.

Now, they maintain a strong fiscal position – they handled both COVID and the crisis with Ukraine-Russia war very well, but threats like an ageing population and climate change are quote certain to face future challenges. Since May 2021, the government has been reforming the healthcare system into a model not dissimilar to the NHS, called Sláintecare. This has not yet diminished their strong fiscal position.

Italy: the toll taken on the Italian economy during the 2008 financial crash was at a cause of poor productivity and significantly low output. In the time between 2014 and 2017 the Italian economy recovered, but did not peak as far as other European economies.

Today, the Italian economy is seeing steady GDP rises of approximately 1% a year. After a period of moderate to high inflation, disinflation forecasts

7

are projected to increase household purchasing power. There is set to be stronger growth of both imports and exports which may come as a result of increased investment.

Greece: post-financial crash, in 2015, Greece was the first developed nation to default on its debt. This was caused partly by the very low tax revenues in Greece, and then their liquidity crisis.

Following on, austerity only worsened the situation by bringing around a humanitarian crisis. After a national vote resulting in the rejection of further EU austerity measures, there was economic turnaround marked mainly of the halving of the unemployment rate from 28% to 13%.

Today, although there has been strong recovery from COVID, surging energy prices have dampened this a bit. Nevertheless, in recent times the Greek economy has been boosted by rising exports and investment and what is said to come next is rebuilding the banking sector where there is still lots of work to be done, and the green transition.

Spain: the Spanish government only got the help it required after the banking sector crisis in the middle of 2012, when Spain formally requested help from the European authorities. Previously, right after the financial crash, there were large risks taken that all proved inefficient. The main cause of the crash in 2008, however, was not the banks – that was more so an effect – it was the real estate and property crisis which lead to deregulation which then impacted the banks. They ended up needing up to €100 billion to get out of this in the end.

Today, Spain is not doing as well as other European countries in that in an era post-COVID with inflationary effects of the energy shortages caused by the Russia-Ukraine war. National debt is once again rising unsustainably, but consumption is supporting the economy to keep on growing due to some real income increases and high households savings from the past.

The ‘PIIGS’ all have come to very different positions in present day, but from a crisis where all nations struggled, their economies have remarkably healed with the necessary international aid.

8

Is GDP Becoming Anachronistic?

Philip Manipadam

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the capstone metric of a nations progress and economic success. It’s embedded in the structure of a country’s economy –government policies (including tax rates and management of inflation), sales forecast by firms, and even the political survival of the government in power. As economist Philipp Lepenies stated, GDP is “the most powerful statistical figure in human history.” (The Power of a Single Number, A Political History of GDP Philipp Lepenies 2016)

GDP is a product of the Great Depression of 1929 and World War 2. In the wake of these events, USA economist Simon Kuznets was tasked in 1932 with devising a metric to estimate the true impact of the Depression. Kuznets computed National Income and conceptualized Gross National Product. The modern definition of GDP was developed by John Maynard Keynes in 1940 as a war time metric to measure an economy’s productive capacity. Post the 1944 Bretton Woods conference, it became a global metric for measuring a country’s economic progress.

Essentially, GDP is the monetary value of all finished goods and services made within a country during a specific period (normally a year). GDP is easy to compute given its quantitative nature. It gives a single headline figure which makes it easy to compare and quantify a country’s progress across years as well as cross nation comparisons. GDP can be computed in three ways: expenditure, production, or income. Furthermore, it can be adjusted for inflation to provide Real GDP.

The main criticisms of GDP are that it ignores the negative effects of economic growth on the environment, society, and quality of life. GDP’s creators had never intended to be an index metric to show the overall health of an economy. Kuznets himself had warned, “The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income.”

A key negative externality that GDP fails to account for is environmental degradation. The production of more goods adds to an economy’s GDP, but is detrimental to the economy and society in the long term – for instance environmental damage like pollution and carbon, and the consequent adverse impact on the climate. GDP ignores depletion of

9

The basis of GDP is that more economic activity translates to a better life. However, the welfare of all citizens – quality of life, health, education, and happiness – does not necessarily improve with economic growth. Citizens may be dissatisfied even if GDP if growing. The distribution of income across society is not captured. A country could show a strong GDP growth, but majority of the population may not be better off with leading to exacerbating income inequality and consequently social discontentment. Having everyone better off, rather than just a few is critical in today’s world. GDP, by convention, only measures goods and services that have a price. This means that unpaid work such as housework or volunteer work is excluded in GDP as it doesn’t “produce” anything.

GDP as a metric has not kept pace with the changing nature of the economy. GDP originated during a period dominated by manufacturing, and hence gives disproportionate focus on production. However, today’s economies, especially affluent ones, are service-led and focus on consumer experience rather than just consumption. Services do not have a physical unit which can be easily counted for GDP purposes.

Furthermore, the technological transformation of society has resulted in a world where many services like information and entertainment are free or the value of which may not lie in a simple figure. Hence these services are excluded from GDP leading to GDP being understated. Another lacuna is that GDP does not reflect growth in balance sheets and net worth of companies, which are substantially higher than GDP growth itself.

Clearly, while GDP provides an insight to a country’s economic performance, its one-dimensional prioritizing economic growth. As Kate Raworth says, “We must measure progress not just by GDP but by wellbeing and quality of life. Economic growth is not the be-all and end-all of human progress.” (Donut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21stCentury Economist by Kate Raworth). A new way of thinking about the economy is required - either a new metric or alternative metrics which complement GDP, reflect the increasing complexity and changing structure of the economy, as well as incorporate welfare metrics. These new metrics must capture production growth as well reflect intangible and non- paying services, levels of economic inclusion and equality, empowerment and sustainability. Despite its limitations, GDP will continue to be the mainstay indicator of economic health especially for policies for. As David Pilling states, “Its great virtue, however, remains that it is a single, concrete number. For the time being, we may be stuck with it.”

10

The Psychology Behind Pricing

Kaila Kondas Niza

Many economic techniques use psychology to maximize profits, engagement, and more. Psychology is used by companies to determine which price is the most attractive to customers, while still ensuring it is high enough to generate profit. Many concepts are used in the psychology of pricing. I'll briefly mention four - Anchor pricing, Decoy price effect, Quality perception, and Sense of bargaining or discount.

Anchor pricing:

This is the initial price that a consumer sees. It is used as a comparison to all future prices. Due to this, if a product is originally priced high, slightly reduced pricing may seem more reasonable in comparison. Therefore a business may establish a visible starting price for a product but will then emphasize its current discounted price, making the consumer think they are getting a good deal or saving a large sum of money.

Decoy price effect:

This is where a third product or option that is inferior in value is introduced. this can make the desired option seem more attractive and influence the consumer's choice.

For example, as seen to the right, the $30 drink seemed expensive until the $50 item was introduced and suddenly it seemed reasonable.

Quality perception:

This is where consumers associate a higher price with a higher quality product, therefore a higher-priced product may be perceived as superior, even if the differences in quality are minimal.

Sense of bargaining or discount:

Consumers are typically attracted to discounts and offers. A reduced price or special promotion can stimulate purchase, as the consumers feel like they are getting a good deal and don't want to miss out, especially if it's for a limited period.

But how does pricing impact consumer perception?

Brand prestige can affect consumer behaviour. As I mentioned earlier, a high price can be a prestige statement for consumers. Luxury brands often use high prices to create an image of superior quality and exclusivity. They may feel like they are buying a higher-status product

11

when they opt for higher-priced products, which is the technique designer/luxury brands use.

Rational vs. emotional decisions. Price can influence the type of decision a consumer makes. If the price of a good or service is lower, it will appeal to logic and rationality, while higher prices can trigger emotional responses. Companies and producers use these dynamics to tailor their strategy to fit their product and target audience.

Actual changes that are made to the prices to influence consumers. Psychological pricing is a common technique many people are likely to be aware of. This is where companies make their goods or services end in numbers such as 9 or 99, for example, $999 instead of $1000, which makes products seem more affordable and attract buyers who are often impulsive with their purchasing choices. Even though the difference is $1, $999 sounds much cheaper than $1000, simply because it's fewer digits and is still technically 'less than $1000’.

Value packages are also a technique used by producers to incentivize consumers to purchase goods. By creating bundles of products or services it can influence purchasing decisions. Consumers may perceive that they are getting a better value for money by purchasing a bundle instead of the individual item, even though it is likely more expensive than the singular item within the bundle they actually need.

12

Soccernomics Book Review

Milo Peters

Recently, I read Soccernomics by Stefan Szymanski and Simon Kuper. I chose to read the book as I have always had a passion for football and have always been intrigued to see how economics can be applied within football. There book was split into different key ideas, the first of which I found most amusing. Titled: Why England Always lose, I found it hilarious the way Stefan and Simon portrayed the controversies and reasons for England not winning a World Cup since 1966. How the expectation in England before a World Cup is always that they will win but always end up underperforming. Or do they?

In the book, many different statistical figures are compared like GDP per capita, population, and footballing experience to calculate a table of how countries perform in international football compared to the resources available to them.

There are many different tables and graphs in the book portraying different types of statistical comparisons related to footballing performance. The book has lots of different data calculations and it is super interesting to see how these values are applied to football in real life. For example, the authors calculated Portugal and Greece to be part of the most overperforming countries when their relatively low populations and GDP per capita is taken into account. Portugal and Greece have both won European Championships, with a population of about 10 million, beating countries like France, Germany and England populations more than 6 times that of Portugal. Another statistic found by the authors is that playing at home gives you an advantage of 2/3 of a goal. The authors looked at massive data bases where thousands of football scores over many years are stored and performed calculations to find the importance of playing at home, the importance of footballing experience, population and GDP per Capita.

Another super interesting chapter of the book was the laws of the transfer market. In this chapter, the authors explained how the transfer market works and why clubs pay a premium for certain players. For example, one of the laws was to never buy a player coming off the back of a great World Cup or European championship campaign. The reason for this is that their price is greatly inflated from their recent performances on the biggest footballing stage and you are very likely to pay a big premium for the player. The

13

greatest example, Chelsea paying over £120,000,000 for Enzo Fernandez who was one of the key players in Argentina's World Cup winning campaign. Arguably, Enzo Fernandez’s performances at Chelsea have been no where near his price tag.

Another law of the transfer market is that blonde players always catch the eyes of scouts and will often be worth more on the transfer market. There is a really interesting explanation in the book to this, so I will leave that for you to explore. These are just 2 out of 11 very applicable and intriguing rules of the transfer market. Moreover, Stefan and Simon also explain how the business of football works and compares the scale of it to other companies. You may think football clubs are massive profit machines that attract lots of investors and create massive revenues however, this is a misconception. The greatest outflow of cash from the clubs is the salary of the players. Up to 68% of clubs revenues are spent on their wage bill. In the book there is a statistical representation that shows the correlation between the wages paid to players and league position. There is an obvious trend that the clubs that pay their players better and spend less on massive transfer sums are the better performing clubs. We can see this at the moment with clubs like Liverpool and Borussia Dortmund who never splash great amounts of money for transfers but always pay there players good salaries and make sure they are feel at home and content at the club.

In contrast, a club like Chelsea who have spent £672.8 million pounds on transfers in the last 5 years are struggling in the bottom half of the premier league. There are so many different dimensions to this book and I feel all of the theory is perfectly backed up by visual representation of tables and graphs.

The only downside to the book: it was written in 2009, so a few statistics and data is outdated. I highly recommend this book to anyone who has an interest in Football and is keen on calculations and the business involved in sport.

14

Saudi Arabia’s Economic Diversification

Kareem Mahmood

Saudi Arabia’s economy has been undergoing a transformation, as it implements reforms to reduce its dependence on oil, diversify income sources and enhance its international competitiveness. As of September 28th, 2023, in the IMFs annual review of Saudis economy, progress was reflected in non-oil growth, which had accelerated since 2021, averaging 4.8 percent in 2022. Despite lower overall growth, non-oil growth remained close to 5 percent in 2023, spurred by strong domestic demand. Diversification has been driven by regulatory improvements creating a more appealing business environment. This has been brought about by a set of recent laws passed in 2023 promoting entrepreneurship, protection of investors rights and reducing overall costs for firms. This has had a direct impact as new investment deals and licenses grew by 95 percent and 267 percent in 2022, respectively. Additionally, the Saudi Investment Fund (PIF) has been investing in significant amounts of capital to stimulate private sector investment.

Oil still dominated the Saudi economy in 2022, accounting for 74% of total exports of goods and services, but this is below the 84% average share seen from 2012-13. This decline in share of Saudi exports is due to the expansion of tourism and petrochemical exports. Travel exports increased from 2% to 5% from 2012 to 2022 whilst petrochemical exports increased from 9% of goods and service exports in 2012 to 12% in 2022. The private sector’s share of the GDP grew from 37% in 2012 to 39% in 2022. The non-oil sector (including the public and private sectors) made up 56% of the GDP in 2022 which showed an increase from just under 52% in 2012. ` within the private non-oil sector, real estate, retail and wholesale trade and community, social and personal services had the most significant growth. The correlation between non-oil private sector GDP and oil prices remains high but has fallen since 2013 suggesting less of a dependency on oil prices than previously.

According to Goldman Sachs, Saudi Arabia’s economy is benefitting from increased investment which is likely to drive a “capex super cycle” (extensive capital expenditure). The areas that are benefitting from this super cycle are Clean tech, Metals and mining, transportation and logistics and digital transformation (which includes a focus on the nations telecommunications).

More recently, Saudi Arabia has attracted about $13 bn in private sector

15

investment into its tourism industry as it aims to share the cost of spending associated with its plans to become a new travel hotspot. The investments aim to add another 150K- 200K hotel rooms within the next two years, according to Princess Haifa M. Al Saud, Saudi’s vice minister for tourism. The country is also targeting raising tourism revenue to $85bn in 2024 from around $66bn in 2023.

Saudi hopes to have 150 million tourists a year by 2030 as part of the Crown Prince’s vision for the economy aimed at diversifying revenue streams away from oil towards industries such as sports and technology. The kingdom has been splashing out capex on mega project developments like the entertainment city of Qiddiya and last year spent large on football to boost its appeal as a foreign travel destination. It’s also the sole bidder for the 2034 world cup. In 2023, Saudi recorded 100 million tourists, most of them locals. International visitors accounted for about 27 million. The government is planning to spend some $800 bn of its own on tourism alone over the next decade.

16

The UK Recession and what it means for Sunak’s government

Anna Zaman

In the second half of 2023, the UK fell into a recession (a sustained period of weak or negative growth in economic activity). According to the Office of National Statistics, the UK’s economy shrank by 0.3% in the final three months of 2023, meeting the criteria for what is known as a ‘technical recession’, as there had been two consecutive quarters of falling GDP. But what does this mean for Sunak’s government, and can he come back from this?

The recession is a clear embarrassment for Sunak, not only because economic growth was one of his five pledges, but with the upcoming general election this year, the prospects of the conservatives winning are even more dire. Jeremy Hunt, Chancellor of the Exchequer, has defended the conservative government by saying: “High inflation is the single biggest barrier to growth, which is why halving it has been our top priority. While interest rates are high – so the Bank of England can bring inflation down –low growth is not a surprise.”. However, do the public agree with him?

According to the most recent IPSOS voting intention poll, the public do not. The conservatives vote share fell to a record low of 20% in the most and whilst Tory unpopularity is also influenced by other factors, the recession has indefinitely contributed towards this extremely low opinion poll. According to opinion polls now, Labour is actually more trusted with the economy, a hard blow to the Tories who have had a long-term reputation of being more fiscally competent.

However, if the government were perceived to be taking the appropriate actions to effectively combat the recession, and improve the economic situation of the UK, then public opinion of the Tories could actually improve, and this would enhance the governments credibility. The delivery of Jeremy Hunts final budget has not seemed to greatly affect the public’s

17

opinion of the conservatives, with the public split on whether it is fair (27%) or not (32%). This is a more pessimistic assessment than Hunt’s Autumn statement back in November which was viewed as fair by 38% to 23%. Therefore, it can be inferred that the public arguably do not think that Sunak’s government are taking appropriate actions to address the recession.

To conclude, the UK in recession has negatively impacted Sunak’s government. It has led to the government being under increased pressure and scrutiny and has further embarrassed Sunak due to the great emphasis he placed on economic growth in his five pledges. Unless the government is perceived by the public as taking appropriate actions to address the recession, and improve the economic situation of the UK, then public perception of Sunak’s government will indefinitely worsen.

18

The Downfall of the Japanese Economy

Malak Ibrahim

Japan is facing many economic issues such as the recession that it has slipped into earlier this year, its ageing and shrinking population and its weak currency due to their negative interest rates. As well as that, Japan’s position as the world’s third largest economy was overtaken by Germany in 2024 as its GDP stood at $4.2tn in 2023 compared to Germany’s GDP $4.5tn.

The Japanese currency, the Yen, has significantly depreciated against the dollar in the last few years. In February 2019, 1 USD was equivalent to around 108 JPY whereas in February 2024, just 5 years later, 1 USD is equivalent to 150 JPY. The Japanese Yen is so weak because the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has kept interest rates very low at -0.1% in January 2024 in order to correct deflation. This has caused the Japanese Yen to depreciate because other countries have raised interest rates making it more attractive for investors to invest in those countries rather than Japan as they have a greater reward for saving. This means that “hot money” flows out of the Japanese economy and so the supply of the Japanese Yen increases and the currency depreciates.

The depreciation of the Japanese Yen negatively affects Japan because the nation is highly reliant upon the import of natural resources, with it being the world’s largest importer of liquefied natural gas (LNG) for many decades as well as the world’s largest net importer of food. Higher import prices can lead to higher production costs for firms, reducing their profit margins. These higher production costs can also feed into higher consumer prices and have inflationary effects, eroding purchasing power and reducing the standard of living. However, a weak Yen is not all bad as it means that exports are more attractive and internationally competitive as they are relatively cheaper and this has specifically benefitted Japanese car makers. A weak currency also helps promote tourism as the purchasing power of visitors from abroad increases.

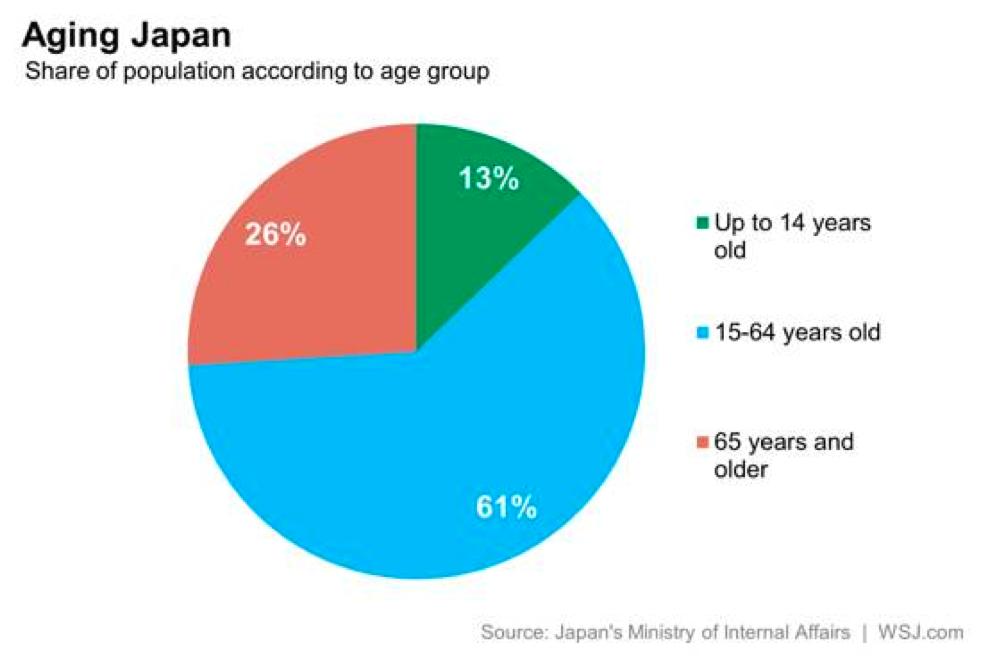

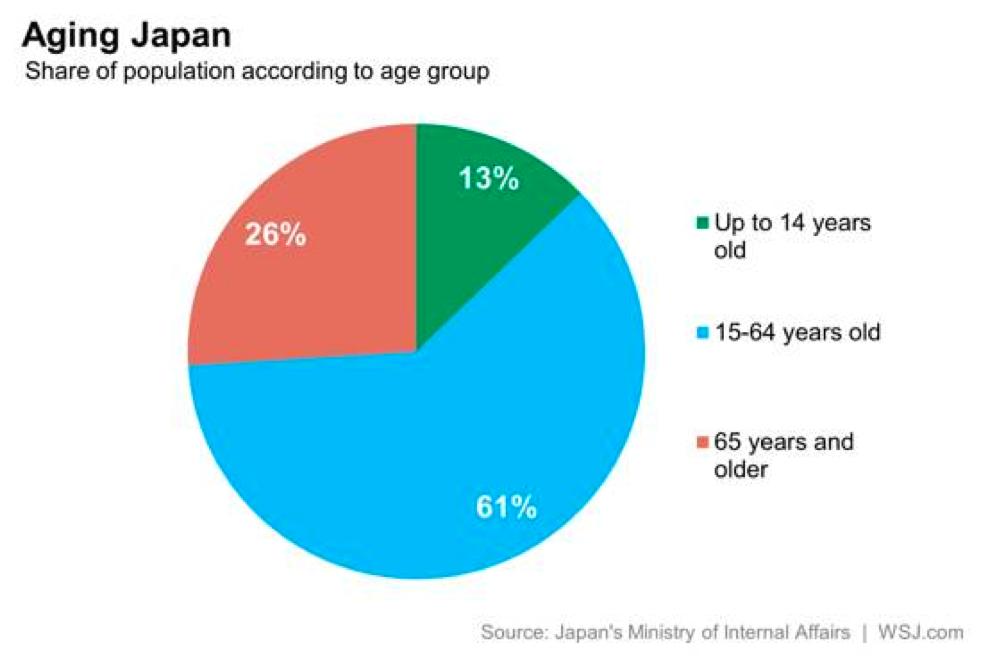

Japan has a serious ageing and shrinking population that is negatively affecting its economy in many ways. Japan is consistently the oldest population in the world with almost a third of its population is over 65 (approximately 36.23 million people) and in 2022, almost half of Japanese firms relied on workers over 70 while The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs report in 2023 found that only 35% of companies prioritise workers aged over 55.

19

Japan is facing many threats to its economy with falling birth rates and an increasing elderly population. This could lead to a huge fall in innovation and productivity as Japan is already facing a labour shortage and by 2040 it could be short of 11 million workers leading to Japan’s prime minister Kishida to pledge $7.6 billion in 2023 to train workers for high-skilled jobs in the next five years along with relaxing strict immigration laws. A shrinking labour force can also lead to lower economic growth due to households having less disposable incomes to spend on goods and services which is a already big issue as Japan has slipped into a recession earlier this year. This can also hinder Japan’s global competitiveness and its position in the global economy (which has already been overtaken by Germany). An ageing population can also be associated with lower employment rates as labour is derived demand.

In conclusion, Japan is facing many economic issues rooting from its negative interest rates and ageing population. Along with the tightening of the monetary policy, Japan requires structural reforms and the introduction of policies to improve its economic situation.

20

Margaret Thatcher and Friedrich Hayek

Antara Kashyap

Margaret Thatcher, the ‘Milk Snatcher’, ‘Iron Lady’ and the UK Prime Minister from 1979 to 1990 characterised the UK in this era by developing radical and new economic policies, with the overarching aim of bringing the UK economy out of recession. Thatcher revolutionised economic policy, not only in the UK but globally, through her neo-liberal outlook and transformative use of ‘Thatcherism’. Thatcherism stresses on the belief in free markets, reduced state intervention, reducing the power of trade unions and a clear focus on privatisation and deregulation. All of these beliefs can be reflected in the theories and ideas of Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek.

Hayek lent great prestige to economic liberalism, helping to shift the intellectual and economic climate to the right. Thatcher’s first exposure to Hayek’s work was during her time as an undergraduate at Oxford, where she read Hayek’s ‘The Road to Serfdom’. Thatcher was drawn to Hayek’s idea that socialism cannot be compromised, because socialism tends to always lead to totalitarian outcomes. This was especially important during Thatcher’s time in office, as she had won against Jim Callaghan, who was accused of being socialist, therefore allowing Thatcher to play into public fears of socialism throughout her election campaign. Furthermore, Hayek’s emphasis on individual freedom, limited government and the dangers of central planning connected with Thatcher’s liberal view on economics.

Hayek and Thatcher both showed mutual respect and admiration for each other, with Hayek praising Thatcher for questioning Keynesian economics and advocating for a free market approach for the UK economy. Thatcher famously, during a Conservative Party conference, held up a copy of Hayek’s ‘The Constitution ofLiberty’ and banged it down on the table, sternly stating ‘This, is what we believe’. This clearly shows Hayek’s profound impact on Thatcher and her outlook on policies and political planning during her time in office, highlighting how Hayek’s ideas helped to form the roots of

21

Thatcherism.

However, it is important to note that Hayek did not view himself a conservative thinker, even going as far as to write an essay titled ‘Why I am Not a Conservative’. In this essay, Hayek scrutinises conservatism and shows his rejection for this ideology. Hayek was compelled to explain he was not a conservative because conservatives had always seen him as one of theirs, and Hayek wanted to dispel this claim. Therefore, it is evident that although Hayek did influence Thatcher, their beliefs were not completely aligned, with Hayek believing in ‘another kind of individualism’, associated with Edmund Burke and Lord Acton, whereby the individual is born into a society and social relationships within the family and closer environment are of paramount importance. Nevertheless, there are echoes of ‘The Constitution of Liberty’ in Thatcher’s ideas. The book focused on the rule of law, the exclusion of the arbitrary and the personal in favour of the open and equal application of rules.

Hayek’s revolutionary work on economics and politics was not just popular with Thatcher in the late twentieth century but remains to have a lasting legacy in today’s day and age. Elon Musk even tweeted a picture of ‘The Road to Serfdom’ on Twitter, telling his followers about this ‘good book’. Ronald Reagan also deeply resonated with Hayek’s work, with Reagan listing Hayek as one of the most influential people for his philosophy and welcomed Hayek to the White House as a special guest. Therefore, it is evident that Hayek’s theories and economic ideas helped shape the political climate of the late 20th century, most notably through Thatcher and Reagan and also has left a great impression on the economic mindsets and ideas of political and powerful figures today. Overall, Hayek’s influence over Thatcher can be seen that as a political and economic philosopher that her mattered, not simply as an economist.

22

Sir Jim Ratcliffe

Diren Kumaratilleke

Sir Jim Ratcliffe

The richest man in the UK has been sent to save a dying giant.

And... He has based his entire business strategy off awakening sleeping giants.

Antwerp 1997

A largely underperforming wing of BP has been put up for sale as part of a major shift away from bulk chemicals with low margins.

Solihull 2016

The last Land Rover Defender slowly rolls off the production line with a tear filled goodbye for this beloved car model.

Sir Jim Ratcliffe sees an opportunity.

Inspec has purchased BP Antwerp in an 84-million-pound deal.

It is done unconventionally with no equity being given up but rather being funded by high-risk debt and bonds, if this goes downhill, Sir Jim Ratcliffe goes down with it.

It was the biggest producer of ethylene oxide and BP overlooked its true potential. A plant the size of London and 400 people will be the foundation for the petrochemicals giant INEOS is today.

Output tripled under Inspec in the first years.

However doom starts calling when a recession loomed, plant sales fell and Inspec shares followed suit.

Everyone was screaming to sell but Sir Jim Ratcliffe had other plans, he completed a management buyout of Inspec and it became the INEOS we know today. This led to more acquisitions with INEOS beating out established giants like Innovene (buying them out completely later) and Reliance Industries.

“How can a chemical company create a car?, this is insanity”

Sir Jim Ratcliffe had a dream to revive his favorite car the Defender and these were the things he heard initially coupled with a few IP lawsuits.

But he never listened to the doubters, using the INEOS Philosophy as the crutch to rely on focusing on what can be done, not what cant.

He got to work on this ambitious project with no backing from major car companies or suppliers as a totally new entrant to the automobile industry.

23

To his dismay he couldn’t start production where the heart of the defender production was in the UK so he looked overseas to Hamburg. He had to make unique parts for the vehicle so he built supplier relations. He traded off certain modern car features to maximise the fundamental principle of the car; utility above all else.

Through a global pandemic and terrible economic downturn, the Grenadier was born. A true symbol and testament to its name.

Manchester 2023

Manchester United have been abysmal for the better part of a decade and a far cry from the club that dominated England and Europe, setting the standard for football. It has devolved to one of the worst managed organisations with crumbling infrastructure, terrible cost management with debt and wages as well as the loss of the Red Devils identity.

Sir Jim Ratcliffe sees an opportunity.

24

Privatisation of public services: solution or problem?

Shyan Ann Teoh

Privatisation is the act of transferring nationalised entities under state ownership into the private sector. Following the breakdown of the ‘post-war consensus’ in the 1970s, Margaret Thatcher and the Conservative Party began the process of privatising numerous nationalised industries, such as British Airways, as part of her commitment to neo-liberalism, which focuses on the free-market’s ability to efficiently allocate resources and limiting government spending and regulation. The significance of privatisation is illustrated in a 1989 poll (Ipsos, 2013), showing that 18% of British people considered privatisation the worst policy under Thatcher’s government in comparison to other widely controversial policies such as the poll tax. Nevertheless, despite a polarised public opinion, the Conservatives went on to win three consecutive general elections, implying the issue of privatisation was not of considerable significance, which begs the question, if whether privatisation is the solution or problem?

The wave of privatised firms in the 1980s held the objective of ending the natural state monopoly of utilities by introducing competition. Since the government operates free from competitive forces and are not subject to the same pressures of making a profit and pleasing shareholders, public sector programmes often stagnate and fail to achieve soluble results. By 1990, over 40 state owned firms employing 600,000 workers had been privatised under Thatcher (Privatising the UK’s nationalised industries, 2016). The success of British Telecom demonstrates the ability for privatisation to succeed, where privatised firms operating under government contracts have strong incentives to deliver on performance since failure to do so would result in cancellation of the contract or losing out to a competitor. Privatisation is expected to dominate the economic agenda of many developing countries, notably in Eastern Europe. In 1990 alone, the German government arranged the sale of over 300 companies for approximately $1.3 billion (Goodman & Loveman, 1991). Competition fosters innovation, efficiency and greater effectiveness in meeting the ever-changing demands of consumers. As a result, this can lead to contractors providing comparable or even superior wages whilst reducing costs of production and improving quality of service.

Although economically privatisation is seemingly the solution rather than the problem, it is imperative that firms remain nationalised in order to serve public interest. Private firms seek to deliver public services while desiring to make a profit, and instead of offering superior wages as previously suggested, tend to do so by lowering wages and quality of materials, ultimately leading to the erosion of the quality of service. Private sector firms have no compunction implementing policies that render essential services unaffordable and

25

inaccessible to significant portions of the population, which disproportionately impacts lower income earners. Profit-seeking firms may not, for example, choose to extend education to the poor or disabled, which presents the strongest argument that firms should remain nationalised to serve public interest and ensure equal access and opportunities to reduce the wealth gap. For this reason, this explains the strong consensus behind keeping the NHS in the public sector. The fundamental principle of healthcare being free at the point of delivery and entirely funded through direct taxation has been an article of faith in Britain since its creation in 1948. Professor Stephen Hawking attested to this by stating that the NHS is “the fairest way to deliver healthcare” (Hawking, 2017). Private firms are unlikely to continue offering an unprofitable service beyond the necessary duration to maintain profitability, leading to a lack of continuity in treatment for patients, ending abruptly and needing to change health providers. Despite the recent strikes and shortcomings of the NHS’ ability to provide decent healthcare, calls for reform have been viewed as the solution, rather than privatisation, indicating the lack of political will to privatise the national service. Additionally, despite the strong Thatcherite belief of state control being inherently inefficient, OECD figures show that the US’ private insurance-based healthcare system spends more on healthcare per person than any other nation (OECD, 2021).

The extent of the desire to maximise profit is highlighted through scandals of illegal activity. For example, a 2016 Tantus Solutions Group review revealed that Alberta Transportation, privatised in 1993, had been caught receiving bribes in exchange for issuing over 600 fake licenses and false certifications (McIntosh, 2018). A lack of transparency within privatised firms arise as private firms are not required to publish accounts showing the allocation of funds like public firms are. An additional argument points to the irregularities and corruption that takes place during the privatisation process itself. Pakistan had begun effective privatisation from 1991 onwards, with the primary objectives of poverty alleviation and paying off foreign debt, but the success of privatisation has been damaged with a current debt at $60 billion and around 43% of the population living below the poverty line (Chodhury, 2012). Furthermore, the lowering of wages provokes more precarious working conditions that jeopardise the living standards of many workers. Despite the existing evidence being limited in illustrating the relationship between employment and wage effects on privatization (Brown, Earle, Telegdy, 2010), this is sharply contradicted with the common fears’ workers have about the anticipated job losses and fallen wages following privatisation, such as when France Telecom unions protested against its privatisation (Evagora, 1996). The impact is primarily experienced by lower-paid workers, among which women and people of

26

colour are disproportionately represented. Benefit packages, such as pension plans and other forms of non-financial compensation, are significantly less for private sector workers compared to their public sector counterparts. That being said, it should be noted that the current strikes taking place predominantly within the health and teaching sector in the UK regard a lack of rise in pay. However, the government’s inability to respond can be mainly attributed to the current economic climate, with inflation spiralling out of control, and a piling national debt.

The fundamental conversation surrounding privatisation has been the debate regarding the extent of the government’s involvement in a capitalist economy. Neo-liberals view the government as an expensive drag on an otherwise effective system, whereas critics argue that the government plays a vital function in ensuring equal provision of essential services. However, a third perspective presents the idea that ownership of firms is not the issue, but rather what conditions firms are likely to act in the public’s interest. As we move away from ideological grounds, a key conclusion emerges: neither private or nationalised firms will always act in the public interest. The underlying threat of corruption and political self-interest means that privatisation will not be able to simply solve the problem of avoiding public interest.

While it has become clear that privatisation causes an overall reduction in the role of the state, therefore applying less pressure on government budgets, and leads to overall economic efficiency, implying that it is the solution, it is imperative that certain services remain under government control, including the NHS and prisons, in order for them to be held accountable by the people during general elections and ensure greater transparency than it would have in the private sector. Although nationalised firms do not necessarily translate into greater efficiency, the moral grounds for keeping such services under the public sector are ultimately much more important when it comes to the issue of privatisation.

27

UK Spring Budget 2024: Impact on the Economy

Karan Maliekkal

The UK Spring Budget 2024, delivered by Chancellor Jeremy Hunt, details important actions which aim to support economic expansion, improve public services, and tackle major financial issues. Despite the good intentions of the policies introduced, concerns were still raised on the effectiveness of these policies in achieving the UK’s macroeconomic objectives. Here is a brief outline on the main policies/actions that were stated to happen by the Chancellor:

National Insurance and Economic Growth

The national insurance contribution rate will be reduced from 10% to 8% of pay in April, following a prior decrease from 12% to 10% in the autumn statement.

Projections suggest the economy will grow by 0.8% this year, followed by 1.9% in 2025 and 2% in 2026, declining slightly in the following years. Inflation, Savings, and Energy Investments

Inflation is expected to drop below the government's 2% goal in the upcoming months, decreasing from 4% in January.

The launch of a new "British Isa" includes a £5,000 tax-free allowance boost for investors, alongside a British Savings Bond with a fixed guaranteed rate

28

over three years.

Funds will be directed towards nuclear facilities, eco-friendly sectors such as offshore wind energy projects, and carbon capture and storage by expanding the windfall tax imposed on North Sea oil and gas corporations.

Climate and Clean Technology

The government chose to keep fuel duty on petrol and diesel at the same rate for the 14th year in a row, decreasing the encouragement for using fuelefficient vehicles.

Funds were allocated to support the growth of clean technology projects, with investments including the acquisition of two nuclear sites from Hitachi for £160m and funding exceeding £1bn for renewable energy initiatives.

Additional Insights

Continuation of the Household Support Fund (HSF) for a brief duration despite anticipations of worsening difficulties.

Worries regarding limitations in local government funding could result in possible reductions or shutdowns of services in the beginning of the fiscal year.

Confirmation of extra funding for Cambridge project to enhance transportation links and aid in growth initiatives for Cambridge University NHS Trust.

The main points of the UK Spring Budget 2024 emphasize on boosting the economy, investing in green technology, making changes to tax policies, and providing financial assistance to different sectors to address specific issues and drive sustainable growth.

In my opinion, whether the UK Spring Budget 2024 will positively impact the economy is unpredictable. Despite the positive focus on long-term growth and investments in local development, concern exists within certain groups of the parliament about the limited impact on public finances, challenges for local governments, and the necessity for more funding certainty. So, the effectiveness of the new policies introduced could go both ways: positively or negatively. The budget's ability to boost economic growth and tackle financial problems will rely on how well it deals with the issues that the economy is currently facing and turns the investments made by the government into concrete results for economic well-being and public welfare.

29

Yield curve inversion crystal

ball and what it tells us about an economy

Oliver Locke

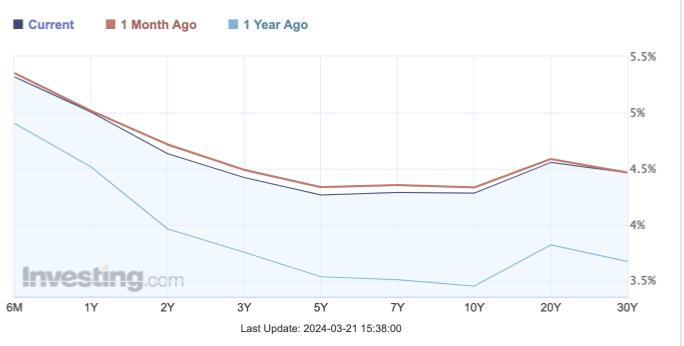

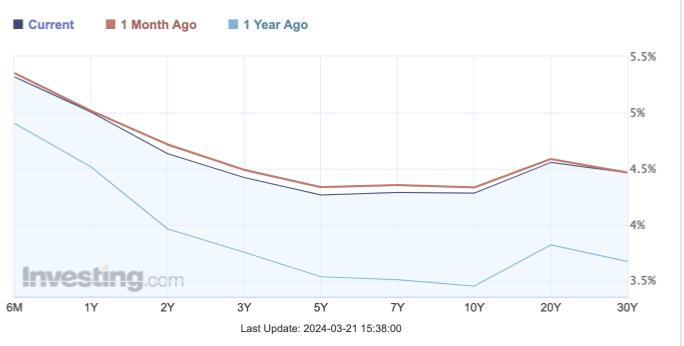

The yield curve shows the relationship between the yield (reward) on debt and the time until it matures. A typical yield curve should show a higher yield offered to lenders as the time until maturity increases (Figure 1). This is due to lenders demanding more reward due to the greater uncertainty over longer time periods. When a yield curve inverts, counterintuitively, the reward for lending is greater in the short term.

The yield curve for US T-Bills March 2024(Figure 2) shows us this inversion, where yield offered is higher in the short term. This tells us that institutions are selling shorter term T-Bills which hence pushes the yield higher. Investors buying longer term bonds tells us that there is an expectation interest rates will be cut in the future and therefore they lock in higher yields in longer term bonds before interest rates are cut (no surprise with 3 expected cuts 2024) . This also suggests a pessimistic outlook by investors on the economy, as they see greater uncertainty in the short rather than long term.

So why is this a problem? Well, the inversion of the yield curve has been seen as a historic predictor of recessions; inverted yield curves have predicted the last 6 recessions, most recently, the financial crisis where the yield curve initially inverted in August 2006, over a year before the official onset in December 2007. This is likely down to lending behaviour that fuels consumption and investment made by households and firms. If the market rate(essentially risk free rate in the case of T-bills) for credit is higher in the short term, then this will impact the demand for short term borrowing hence causing recessions as it becomes more costly for firms and consumers to borrow. It can be argued that the yield on T-bills is as if not more important than interest rates when it comes to day to day lending such as on

30

mortgages or car loans, because if the T-Bill yield rises in the short term then lenders will want a greater reward for lending to individuals if they can gain more buying government debt essentially a risk free decision. While likely less impactful, it may also lead to a negative wealth effect as rising yields in short term bonds means investors need not look at higher risk assets such as stocks for high returns creating greater competition for consumer and institutional capital hence a fall in stocks leading to people being less wealthy.

31

03/01/24

Term 2 Seminars

Mayher Tyagi

17/01/24

Mr. Christos Sermpetis, McKinsey and Company

'All About Poverty’ – a session encompassing the definition of poverty, trends, globalisation, climate change and reduction in poverty.

‘Management Consulting’ - Mr. Sermpetis delivered a ‘Q and A’ type session on the world of Management Consulting, explaining what the job is, how he got in to the job and the firm and how a consultant’s life looks like.

23/01/24

Diren Kumaratilleke

07/02/24

Eleftheria Sermpeti, Christian Ruiz, Philip Manipadam

21/02/24

Christian Ruiz

28/02/24

06/03/24

Eleftheria Sermpeti, Christian Ruiz, Philip Manipadam

Ms. Donna Benton, The Entertainer, The Benton Group

‘The Vape Industry’ – Diren delivered a compelling session about how vaping companies make profits, their marketing strategies and policies around the world trying to mitigate the sales of vapes as well as potential future economic effects or consequences of this industry.

‘The Houthi Attacks’ – a session led by the DKS Heads on the ongoing Houthi attacks in the Red Sea and their economic repercussions.

‘Financial Markets’ – Christian examined and explained how financial markets work, macro analysis and trading tools stemming from his internship at a hedge fund.

QUIZ – the Heads hosted a quiz about current economic affairs

‘How The Entertainer and The Benton Group came to being’ – Ms. Benton delivered a fantastic session about her journey to the Entertainer, her work in the company, the transition out and back in to The Entertainer, and the founding and creation of The Benton Group along with other ventures like Caha Capo she founded along the way.

32

THANK YOU EVERYONE FOR SUCH AN AMAZING TERM! HAVE A FANTASTIC SPRING BREAK AND RAMADAN KAREEM!

- THE DKS TEAM

ELEFTHERIA, CHRISTIAN AND PHILIP