3 minute read

Clinical Case Review: Septic Peritonitis in Feedlot Cattle

By Dr. Jacob Hagenmaier, Production Animal Consultation

Abdominal organs are cov ered with a thin serous lining, known as the visceral layer, and the abdominal wall is also covered with a serous lining, known as the parietal layer. Together, the visceral and parietal serous membranes comprise the peritoneum. A potential space exists inside the peritoneum, both between the abdominal wall and organs or amongst the organs themselves and is referred to as the per i toneal cavity. This cavity is the anatomic loca tion where peritonitis is found on necropsies in feedlot cattle.

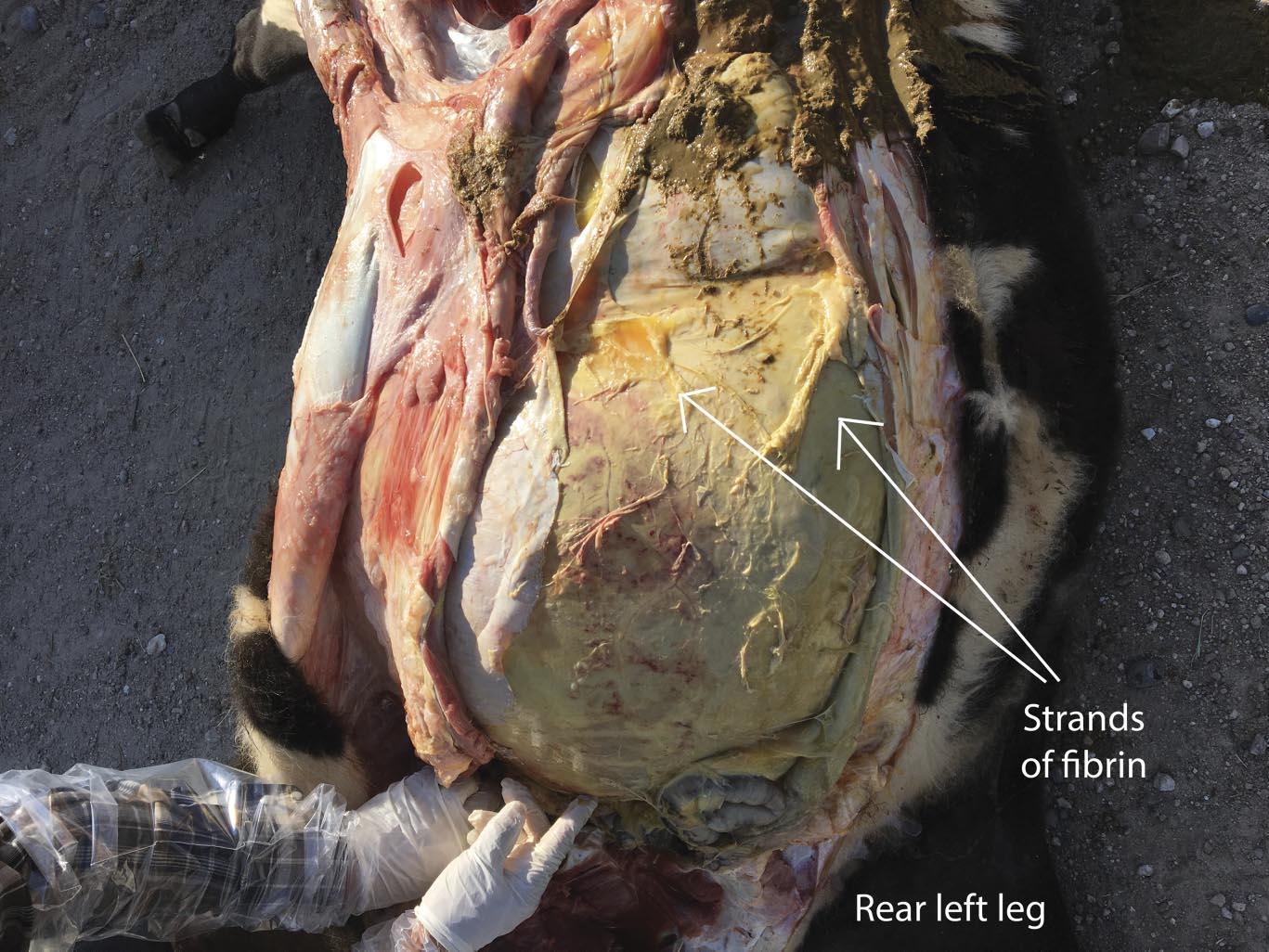

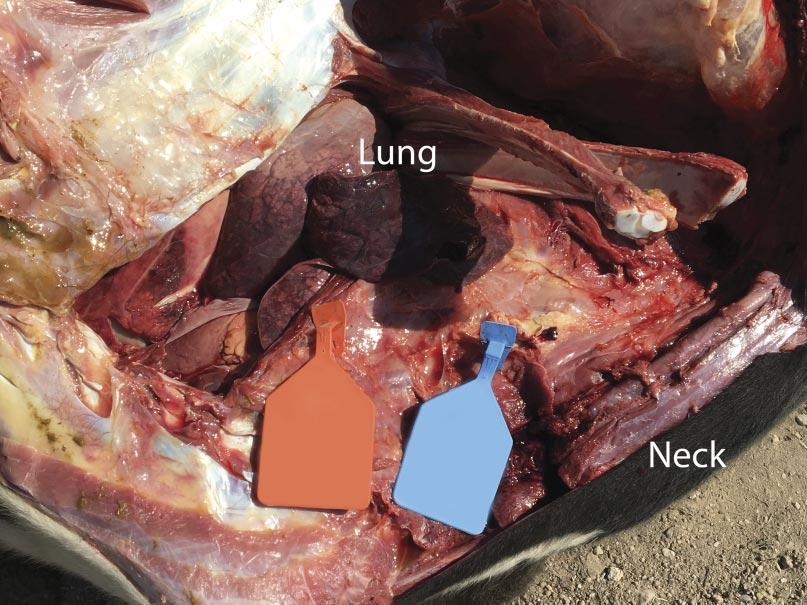

Infectious peritonitis most commonly occurs as a sequela to another disease affecting the gastrointestinal tract or other abdominal viscera. Some examples include the rupture of a liver abscess, hardware disease, perforation of the intestines, abomasal ulcers, grain overloads, and dystocia. Regardless, each of these examples revolves around the translocation of bacterial pathogens into the peritoneal space and subsequent inflammation of the peritoneum due to migration of inflammatory cells. Cattle are notorious for producing fibrin during bouts of peritonitis, which is a stringy, insoluble protein formed during the acute inflammatory process that is involved with clotting blood (Fig. 1). The clinical signs of acute peritonitis may be difficult to discern from other diseases such as BRD, but typically include reduced feed intake, fever, depression, continuous shifting of weight, abdominal discomfort (kicking at their belly), and an arched stance. In chronic cases, fluid accumulation may result in a noticeable pendulous abdomen, which can be confirmed by tapping the ventral abdomen with a needle. Depending on the location of the peritonitis (diffuse versus localized), transrectal palpation may reveal fibrous adhesions in chronic cases as well. It is not uncommon to notice lesions outside of the abdomen that are a sequela of peritonitis, especially in cases where sepsis (infection of the blood by bacteria) occurs and allows the bacteria to seed other organs such as the lungs (Fig. 2) and vasculature. In fact, bacterial absorption into the blood resulting in endotoxemia, shock, and disseminated intravascular coagulation is frequently the ultimate cause of death in cattle affected by infectious peritonitis.

Unfortunately, the prognosis for cattle affected by either infectious or septic peritonitis (or both) is poor and highly dependent on the chronicity of the disease at detection. Fluid, anti-inflammatory, and antibiotic therapy are all warranted in these cases, although they may be unrewarding. Effort should be taken to understand the potential cause of the peritonitis and implement corrective action to prevent future cases.

A Recent Encounter

Recently, a feedyard consulted by a veterinarian member of PAC had a flurry of acute mortalities occurring in heifers. The mortalities began occurring near the end of August and were only present in two groups: one set of 600-pound heifers that were placed on August 28, and another set of heifers that weighed 540 pounds when placed on June 28 (approximately 60 days on feed at onset of mortalities). Affected cattle were lethargic, off-feed, and non-responsive to therapy with multiple antibiotics. By the end of September, 16 mortalities attributable to septic peritonitis had occurred in these groups of heifers alone, without issue for the remainder of the cattle in the feedyard.

It was communicated to the veterinarian immediately following the first mortality on August 29 that both groups of heifers had been processed during the morning of the previous day. The cause of death was investigated at necropsy and confirmed to be attributable to septic peritonitis. Further examination revealed perforations in either the distal colon or rectum (Fig. 3), the presence of fecal material within the abdomen, and pulmonary petechial hemorrhage (Fig. 4). Additional necropsy findings included exudate around the perforations and fibrous adhesions throughout parts of the gastrointestinal tract and on the surfaces of the abdominal viscera. Collectively, these findings are consistent with peritonitis, followed by a secondary septicemia resulting in death.

It was concluded the cause of these rectal perforations was due to an ultrasound wand being used to introduce the probe for imaging for detection of pregnancy (Fig. 5). While the technician performing these pregnancy diagnoses was experienced, this case speaks to the training and experience required before using such tools. The wands are more rigid and do not move with the gastrointestinal tract as an arm would during manual palpation, and this case highlights the need to evaluate facilities and personnel when deciding which modality to use for pregnancy diagnosis. Ultrasound technicians should always take the time to make sure adequate lubrication is being applied to the arm or wand and consider the size of the heifer when deciding whether or not the use of a probe is appropriate.

Over the last decade, ultrasound technology has been rapidly adopted as a means of pregnancy diagnosis in lieu of manual palpation. While ultrasound can be an effective tool, managers and caregivers must understand the potential risks and prioritize education and training to minimize preventable complications following its use.