8 minute read

Lowe Speaks at Duke University Forum Series on Conservation and Health

By: Dr. Jim Lowe, Production Animal Consultation

In February 2016 I was one of two speakers at the Duke University Forum in Durham, North Carolina, entitled “Modern Livestock Production: Are the Benefits Worth the Risks?” With a subject like that, there was plenty to talk about as I explained how modern livestock production is critical in meeting the world’s food needs over the next 30 years.

Advertisement

My presentation which was titled “Assuring there is enough to go around” described how modern agricultural practices have helped assure a safe, affordable food supply while using fewer resources and enhancing environmental sustainability.

The forum was attended by over 100 people including Duke University students; faculty from Duke University Schools of Medicine, Law and the Environment; faculty from North Carolina State University Colleges of Veterinary Medicine and Agriculture; and staff from state and federal government agencies.

In my presentation I reviewed the food needs of the 9 billon people that will inhabit our planet by 2050, explaining that as a society we have a moral and ethical obligation to provide food for everyone in a way that creates the least damage to the environment.

Making our food system less efficient is not an option. So how do we use the available land and water with increased efficiency to produce twice as much food as we do today? Achieving this will depend partly on reducing post-harvest losses – estimated to be 30% of all production world-wide – but will mostly rely on adapting and using novel technology. To predict the future, it is important to understand the past. For most of history, agricultural farmers have been price takers, not price makers. Therefore they respond to market trends and demands, which is very different from other industries. Several long-term megatrends have influenced how we raise food in industrialized countries:

1. People want to live in cities.

2. People desire low-cost food.

3. People desire convenient (prepared or partially prepared) food.

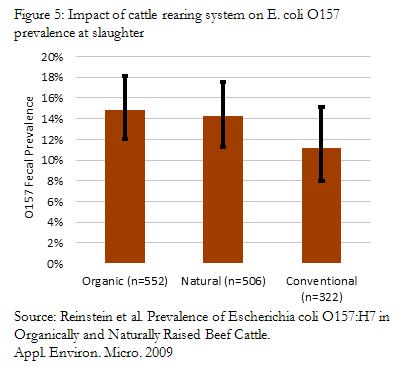

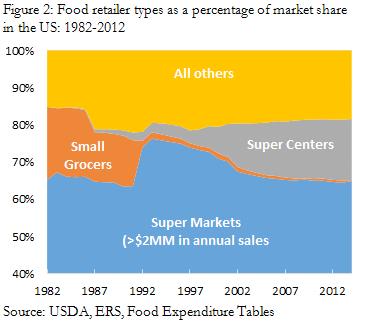

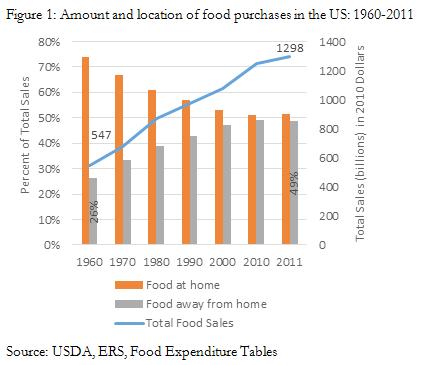

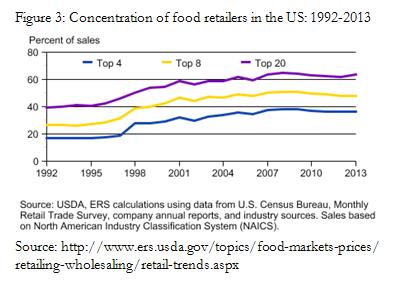

4. People are eating out more instead of eating at home. These megatrends have led to many changes in the food supply chain over time. In the US, there has been a 450% increase in the amount of food consumed outside the home since 1961 (figure 1) and supercenters have replaced small local grocers (figure 2). In addition, the top 4 grocery chains now control 40% of the market, up from 20% of the market 20 years ago (figure 3). These consumer and supply chain trends coincided with consolidation in the packing and production segments of the food chain. It is likely not a coincidence that at the same time consolidation was occurring in the food supply chain, there was an increase in the efficiency of the food supply chain (figure 4).

Some in society believe we should revert to a more local food system that relies less on technology in order to minimize the environmental impact of food production and increase food safety. The facts do not support that these benefits would materialize.

If we change to a local food system where all food is produced within 100 miles of where it is consumed, we would need 25% more fossil fuel to produce the same crop and we would produce 22 million more pounds of carbon dioxide per year than current methods (Sexton 2011). Looking at ONE crop – corn – it would take 37 million more acres, 35% more fertilizer, 23% more chemicals and 23% more fuel to meet human food demands with similar increases for other crops.

Using livestock as part of the sustainable food production cycle and raising them where grain is produced is a critical part of long-term environmental sustainability. Using the manure from 1 pig as fertilizer will replace 74 pounds of nitrogen, 0.17 pounds of phosphorus and 7.58 pounds of potassium per year. This results in a reduction of 81.65 pounds of carbon dioxide being dumped into the atmosphere. Tom, Fischbeck and Hendrickson investigated three dietary and food production scenarios and how they would impact greenhouse gas emissions. They state: The three dietary scenarios we examine include (1) reducing Caloric intake levels to achieve ‘‘normal’’ weight without shifting food mix, (2) switching current food mix to USDA recommended food patterns, without reducing Caloric intake, and (3) reducing Caloric intake levels and shifting current food mix to USDA recommended food patterns, which support healthy weight. This study finds that shifting from the current US diet to dietary Scenario 1 decreases energy use, blue water footprint, and GHG emissions by around 9%, while shifting to dietary Scenario 2 increases energy use by 43%, blue water footprint by 16%, and GHG emissions by 11%. Shifting to dietary Scenario 3, which accounts for both reduced Caloric intake and a shift to the USDA recommended food mix, increases energy use by 38%, blue water footprint by 10%, and GHG emissions by 6%.

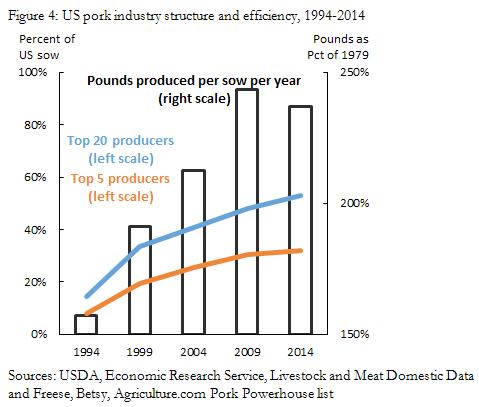

Local food production and smaller supply chains, with more “natural and organic” production, will not improve food safety. Reinstein et al. (2009) demonstrated that the prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in organically and naturally raised beef cattle was the same as conventionally raised cattle, suggesting that there is no food safety benefit to alternative production methods (figure 5).

In addition, Chipotle, who touts its “local, natural” supply chain, has experienced a high number of food poisoning outbreaks at its restaurants over the last 6 years, again demonstrating that small local supply chains are not safer. In fact, there appears to be a benefit of tighter supply chains (fewer suppliers) because of increased transparency and therefore accountability for who is supplying unsafe food.

Local and alternative food production methods also create economic hardships for consumers as organic foods have a much higher price (68% in 2012 shopping comparison, Thomson, personal communication) than conventionally produced foods.

This higher food price can have broad-ranging implications by shifting spending patterns. According the US Census, the bottom quartile of incomes in the US spend 13% of their disposable income on food. If food prices increase 68% due to changes in the food supply chain, they will now be spending 22% of their disposable income on food.

This shift is likely to change demand for other goods and services in the economy. As an example, for every $1 spent on housing, an additional $1.40 is created in the overall economy (http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2003/200317/200317pap.pdf). Over the last three years, the US has spent over $4.4 trillion per year on new home construction. This is worth $6.2 trillion to the economy. If there is a 10% change in food price, on average there will be a 6% change in money available for housing and a resulting reduction of 2.4% in housing prices. This means there will be a reduction of $100 billion in new housing construction and $150 billion in associated economic activity.

If “local” food systems are not the way forward, what is? In the US, the market is already driving changes to meet the demands of the consumer. The integration and consolidation of the retail and food service sectors are sending clear market signals that different models of production and processing are desired in the market and over time there will be many different supply chains feeding the US at different price points and many products with different “attributes” that are valued differently by different people.

We see these examples in the market every day: organic, natural, grass fed, antibiotic free, cage free, etc. The most interesting part of this change is that these products are no longer the sole province of specialty retailers like Whole Foods; Walmart, the discount chain, is now a major player in the “organic” business. Conversely, Aldi, who is known for no frills groceries, is still a rapidly growing chain in the US, suggesting there is still a large part of the US consumer base that expects low-cost, high-quality, safe food. What we are seeing is that choice will be king: the top of the market will continue to expand and differentiate, but the core commodity product will always be there.

A key to feeding 9 billion people will be to transfer the right technology to areas where food needs to be grown, to allow those regions to develop and feed themselves in a sustainable way. Optimizing the efficient use of resources and minimizing environmental impact at a pace and scale the world has never seen is the challenge before us.

We can export food or technology or BOTH… but the challenge is daunting: 22% of the world’s people (1.2 billion) live on less than $1.25 per day and 40% (2.2 billion) live on less than $2 a day, but 75% of these people raise livestock – livestock are literally LIFESTOCK for these people (BeVier, 2016).

The US and western Europe are mature markets and meat production will stabilize or shrink over time in response to slowing population growth. Growth of livestock production will happen in the rest of the world. If we are worried about the US then our strategy is wrong as the game will be played half way around the world.

The challenge will be to increase livestock production in a sustainable way as we strive to meet the needs of a growing middle class. The pace and scale needed for growth while dealing with issues of bad government and climate change is truly a daunting challenge. Think about the impact of the Industrial Revolution on the environment – these coming changes will be orders of magnitude larger.

Roughly one-third of food produced for human consumption is lost or wasted globally, which amounts to about 1.3 billion tons of food per year. This appears to be an area where gains in food availability can be made quickly. We have already developed technology to minimize post-harvest food losses in the large-scale US production system.

Adapting this technology in developing countries will be key. But we cannot forget the critical role that animals play as they can serve as a storage of grain and converter of “waste products” for human consumption. Our goal is to retain calories in the human food chain and improve the quality of those calories by using animals.

The key will be to understand HOW to apply those technologies for them to be successful. Dennis DiPietre, a well-respected ag economist said, “Every new technology has to come wrapped in a set of standard operating procedures for it to be successful” (2016). His key point was that while “technology” is useful, it only works if the people with access to it know how to use it correctly. This is the key part of any development program that is often forgotten and hard to do.

In his 2016 article in JAVMA, Gregg BeVeir noted, “Improvements in livestock genetics, nutrition and health are needed to increase efficiencies of production, but these improvements will not succeed without greater veterinary support services.” He like DiPietre suggests that the US food production system needs to be able to export not only the technology that has made it successful but the human capital to make it work where it is most needed.

There is not a “simple solution” and going backwards is not an option. Our challenge is to meet the needs of everyone, especially those most in need, but to do it in a way that creates the greatest good for the most people. Integrated, systems-based approaches are needed but they have to be market based if they are going to be sustainable. People have to WANT and be willing to PAY FOR the food that we produce if any food production system is to be sustainable.