MICA

THE COLLECTION OF MICA ERTEGUN

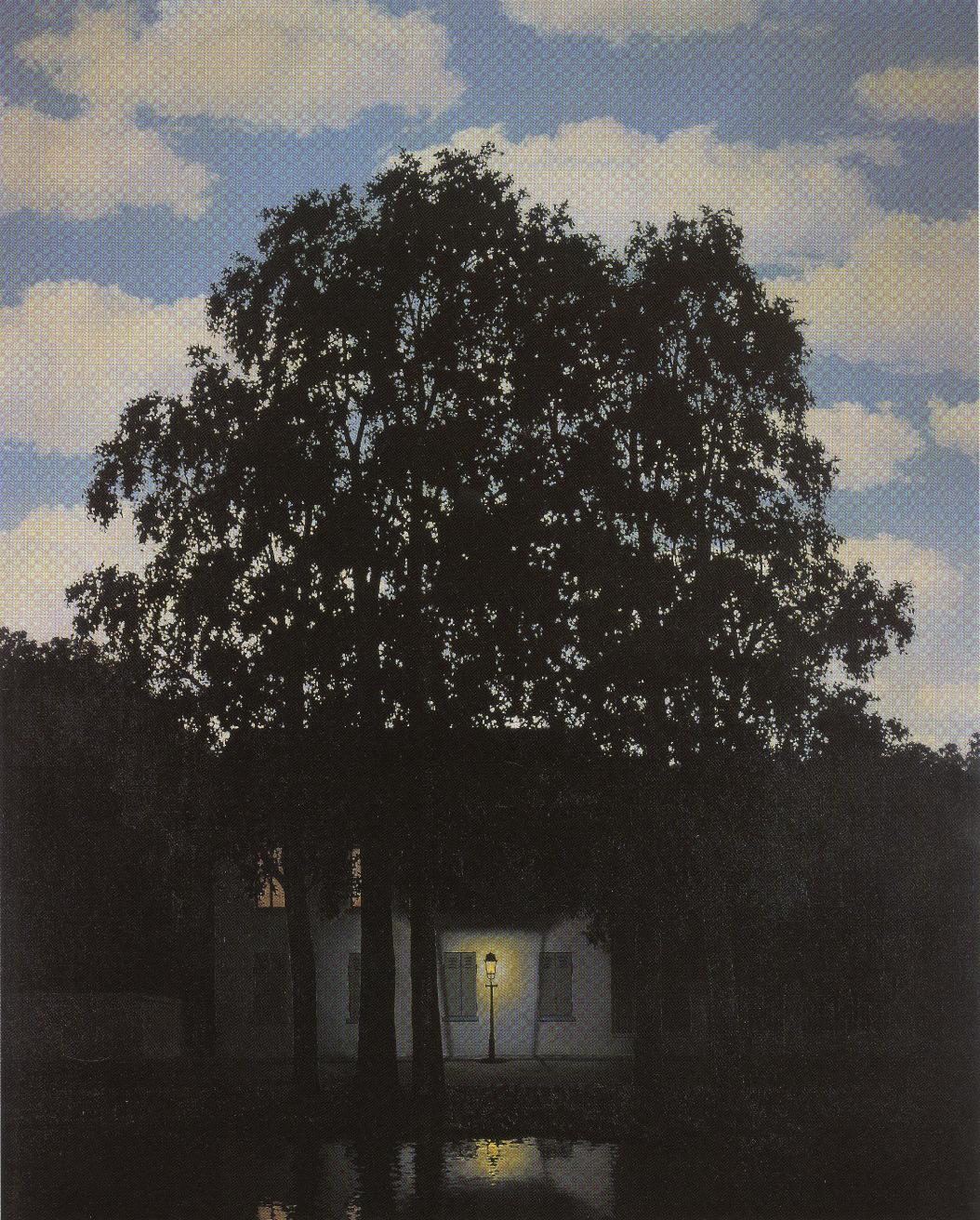

RENE MAGRITTE

L’empire des lumières

RENE MAGRITTE

L’empire des lumières

L’empire des lumières

“I think as though no one had ever thought before me.”

– RENE MAGRITTE

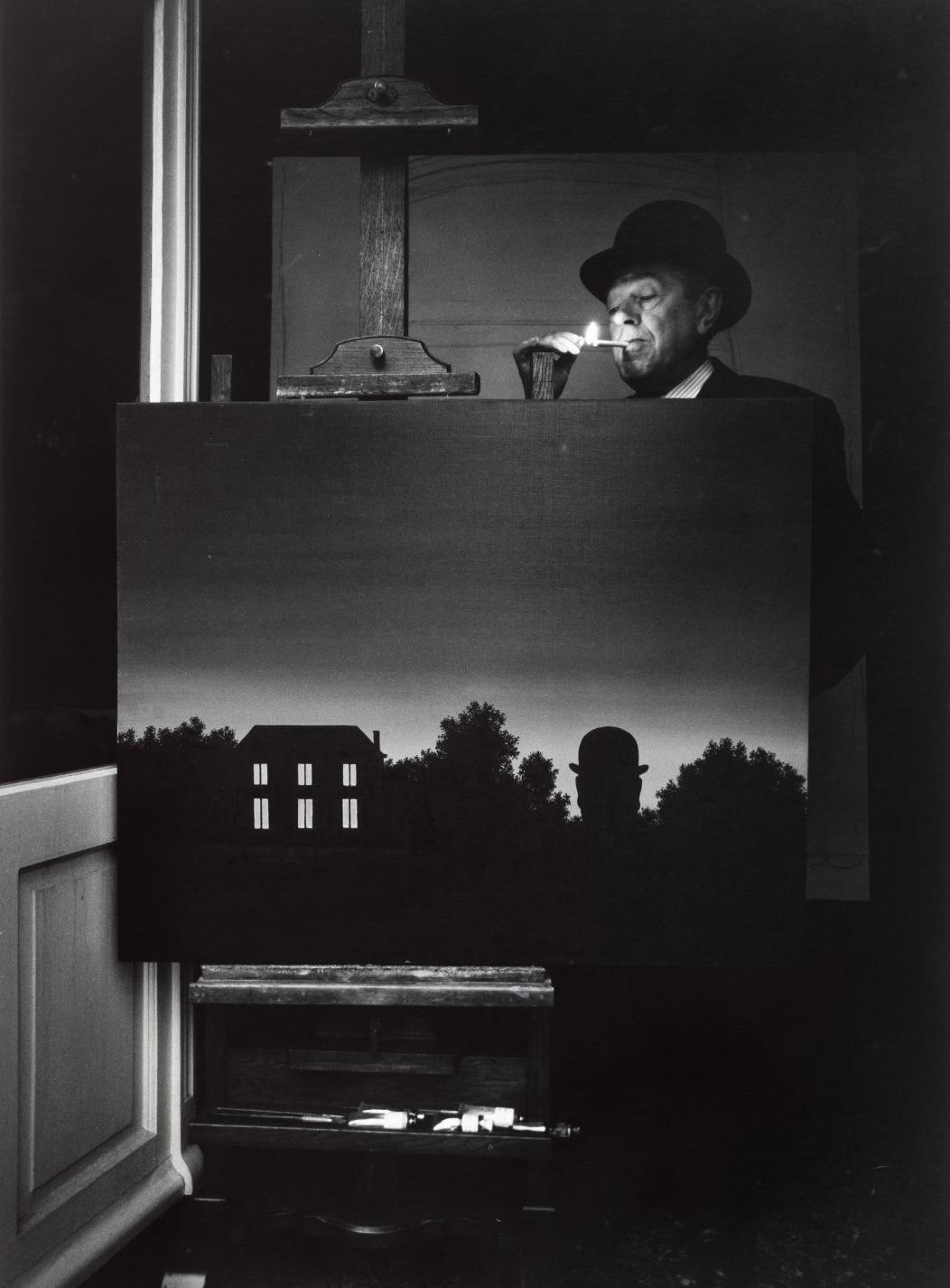

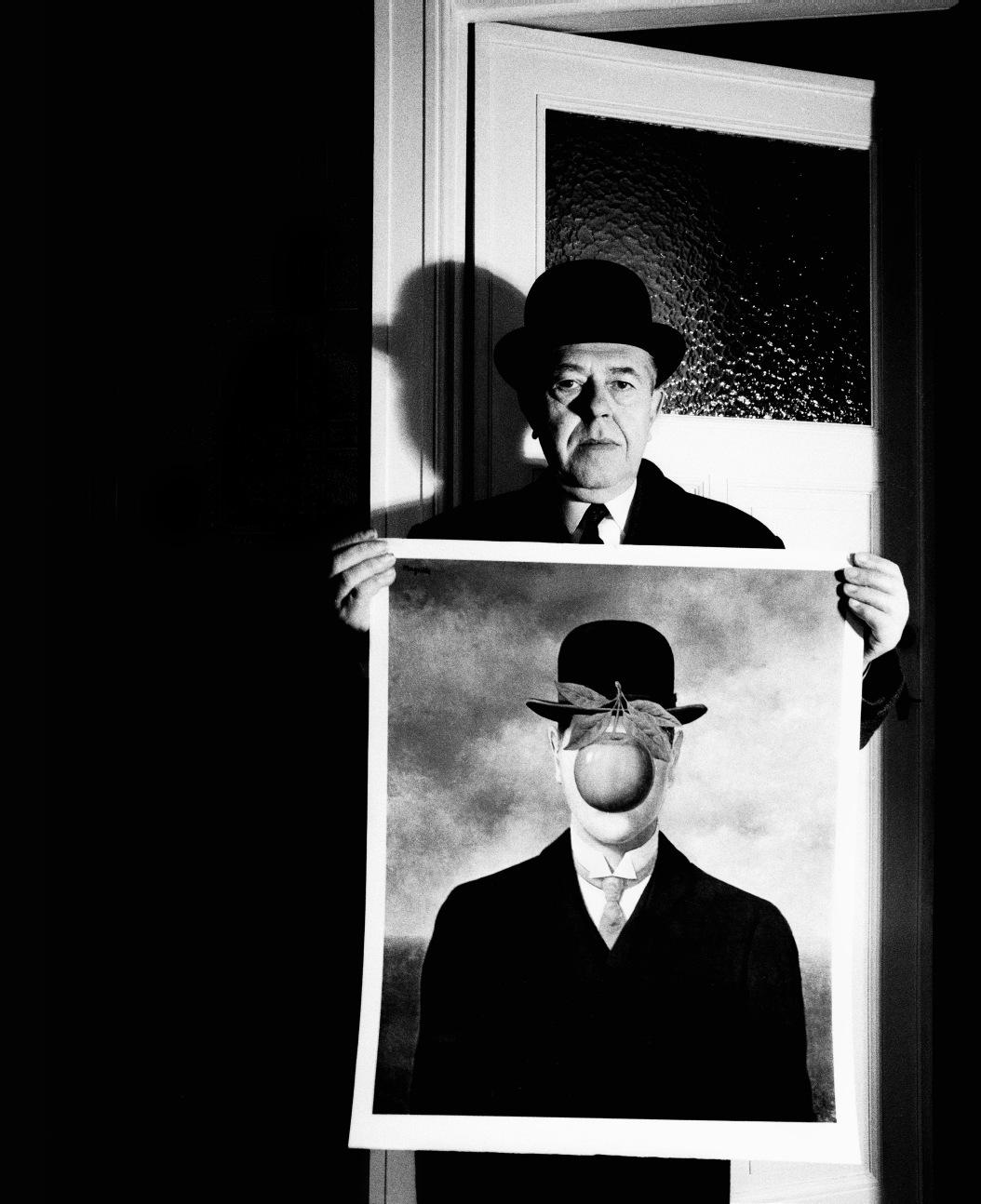

René Magritte, 1967. Photo: Marcel Broodthaers. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SABAM, Brussels. Artwork: © 2024 C. Herscovici / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image: The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY.

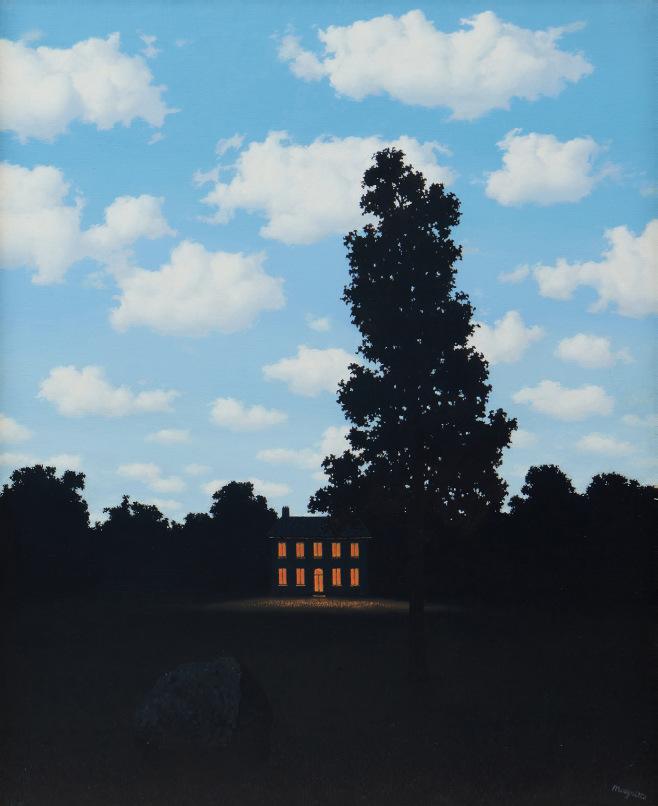

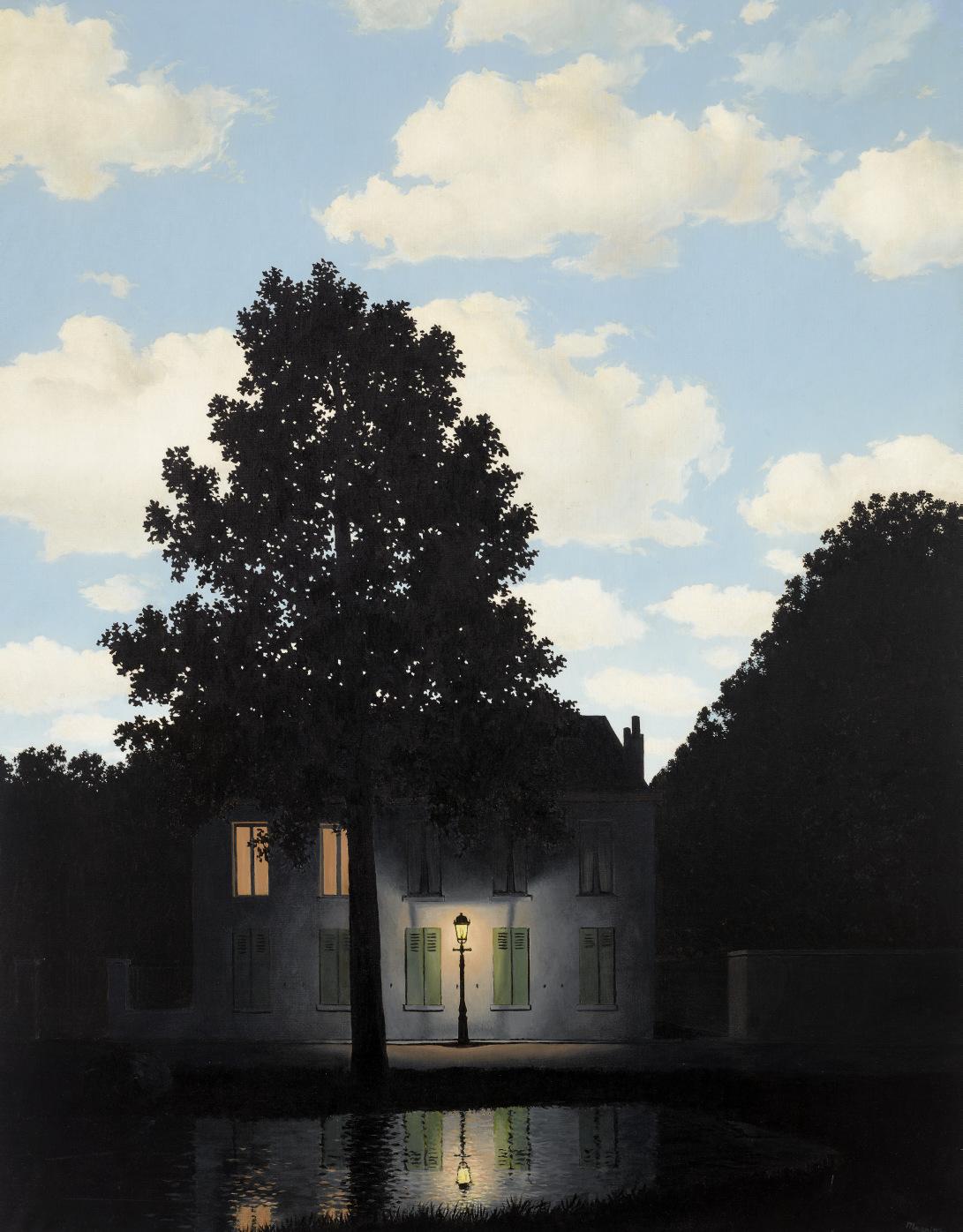

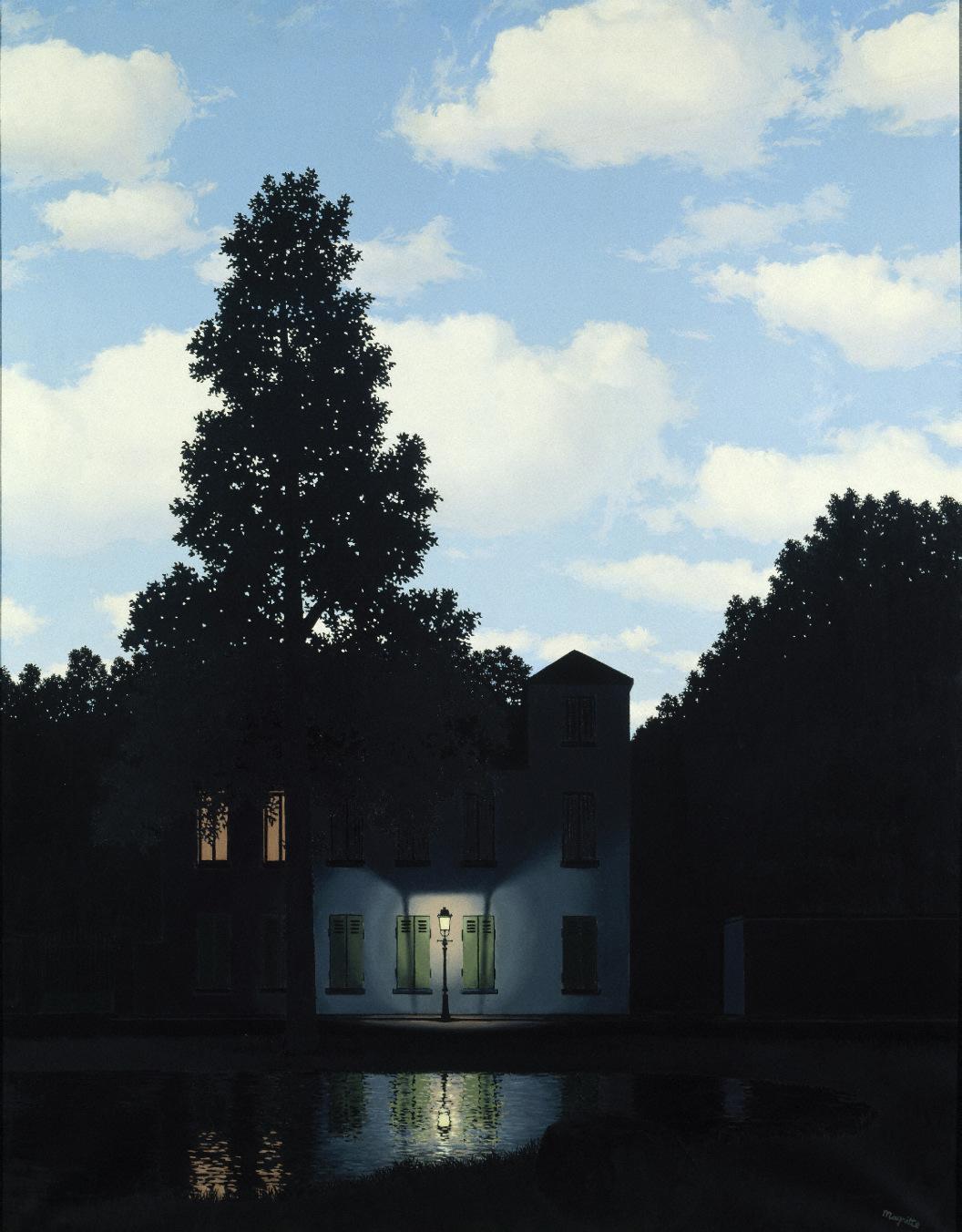

Filled with a rich sense of mystery that confounds and beguiles in equal measure, René Magritte’s L’empire des lumières of 1954 is a powerful example of the artist’s extraordinary, mature Surrealist vision. Focusing on the juxtaposition of a landscape bathed in deep shadows with the blue expanse of a day-lit sky above, this seemingly impossible collision of day and night in a single moment quickly became one of his most celebrated and iconic subjects. Between 1949 and 1964, the artist created a total of seventeen versions in oil, with several more iterations in gouache, on the theme of the L’empire des lumières. Each subtly different from the next, with intriguing variations and diversions from canvas to canvas, these paintings demonstrate Magritte’s endless spirit of invention, as he probed the rich poetic potential of his deceptively simple subjects.

As Magritte explained, the power of works such as L’empire des lumières lay in transforming the familiar, everyday world in unexpected ways: “For me it’s not a matter of painting ‘reality’ as though it were readily accessible to me and to others, but of depicting the most ordinary reality in such a way that this immediate reality loses its tame or terrifying character and presents itself with mystery” (quoted in H. Torczyner, Magritte: Ideas and Images, New York, 1977, p. 203). Executed with a precision and attention to detail that only reinforces the uncanniness of the scene, the L’empire des lumières paintings offer an elegant summation of Magritte’s unique form of Surrealism, reveling in a game of unexpected contradictions, in which all is familiar and yet ultimately strange, and the ordinary is rendered extraordinary.

“This intense personal interest in night and day is a feeling of admiration and astonishment.”

– RENE MAGRITTE

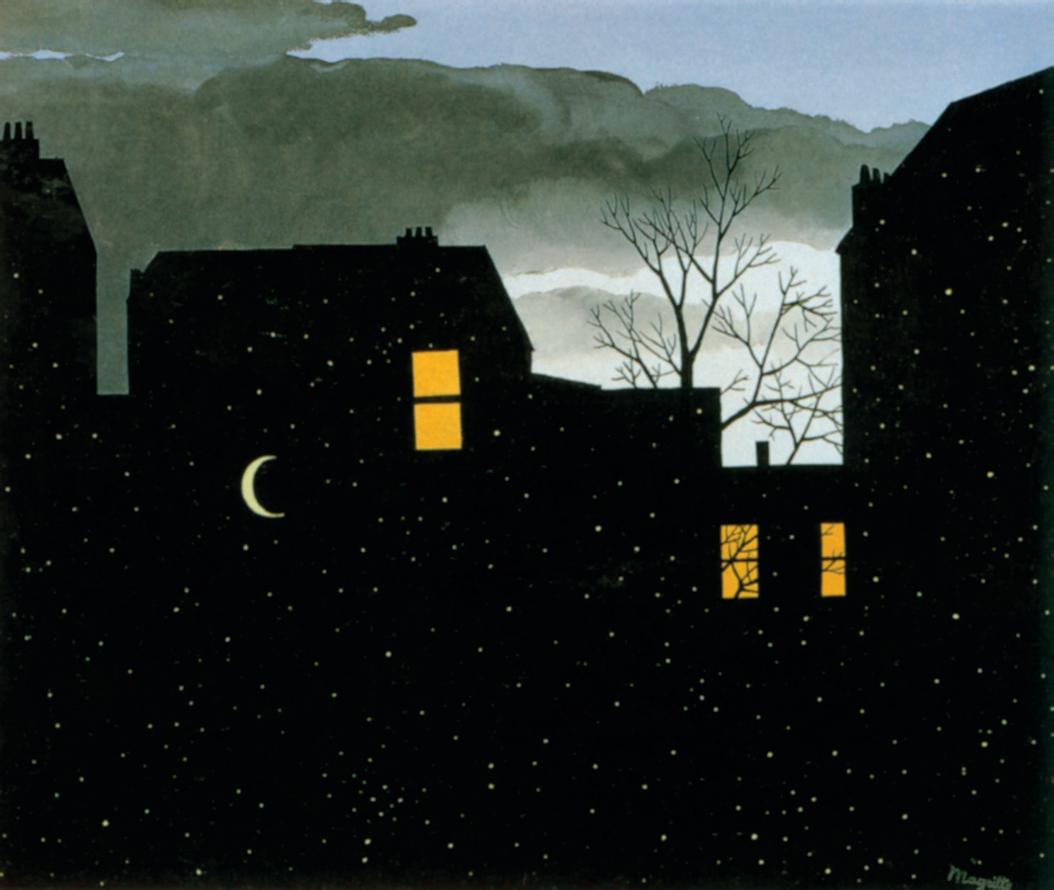

The idea behind the L’empire des lumières series appears to have been percolating in Magritte’s mind for several years prior to his first painting on the theme. While staying with the collector Edward James in London during the spring of 1937, Magritte gave a presentation at Roland Penrose’s London Gallery in which he discussed “certain features peculiar to words, images and real objects” (quoted in D. Sylvester, ed., René Magritte: Catalogue Raisonné, Oil Paintings, Objects and Bronzes, 1949-1967, London, 1993, vol. III, p. 53). In one example early in the discussion, the artist cited the opening line of André Breton’s poem L’Aigrette (from Terre de clair, 1923): “If only the sun would shine tonight” (ibid.). The following year, the artist created a gouache entitled Le Poison (Sylvester, no. 1142; Museum Boijmans-Van Beuningen, Rotterdam) in which a row of buildings took on the appearance of the night sky, dotted with constellations of stars and a delicate crescent moon, transforming the bricks and mortar streetscape into an evocative, otherworldly vision of the cosmos.

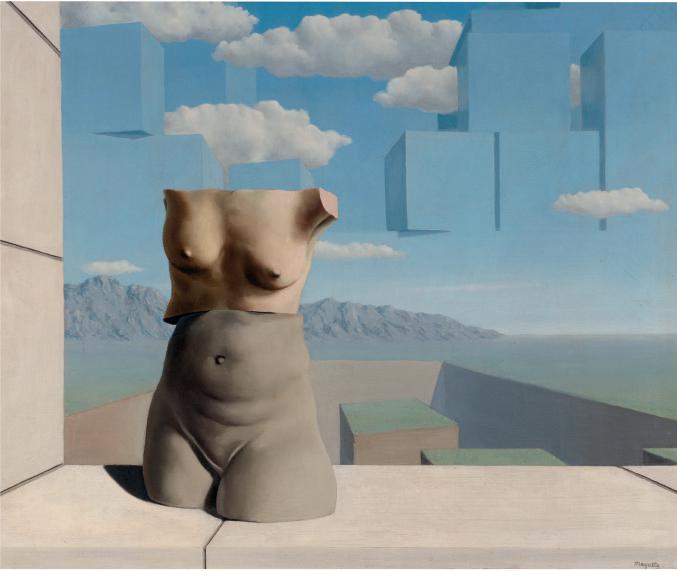

In this way, Le Poison was a continuation of Magritte’s different translations and juxtapositions of the sky, which was a recurring character in his work, its familiarity allowing him to investigate the world of appearances, and question our understanding of its properties. While paintings such as Les muscles célestes (Sylvester, no. 166; Private collection) explored the physicality and presence of the sky, and L’ombre céleste (Sylvester, no. 168; Private collection) transformed it into a flat piece of stage scenery, it most frequently appeared as a framed picture within Magritte’s oeuvre. In these works, a little segment of the vast blue expanse, dotted with clouds, has been magically captured and condensed into a small, portable object as in Les perfections célestes (Sylvester, no. 329; Private collection), Le Salon de Monsieur Goulden (Sylvester, no.

René Magritte, Le Poison, 1938 or 1939. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. © 2024 C. Herscovici, London / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“Optical illusions [are] the privileged moments that transcend mediocrity. But for that there doesn’t have to be art—it can happen at any moment.”

– RENE MAGRITTE

300; Private collection) and Le palais de rideaux (Sylvester, no. 305; The Museum of Modern Art, New York). In other works, Magritte used the ubiquitous sight to generate impossible scenarios, as in his famed oiseau de ciel, a magical bird, captured mid-flight, which appears to be cut from the sky itself, its body filled with a pale blue sky and soft, fluffy clouds.

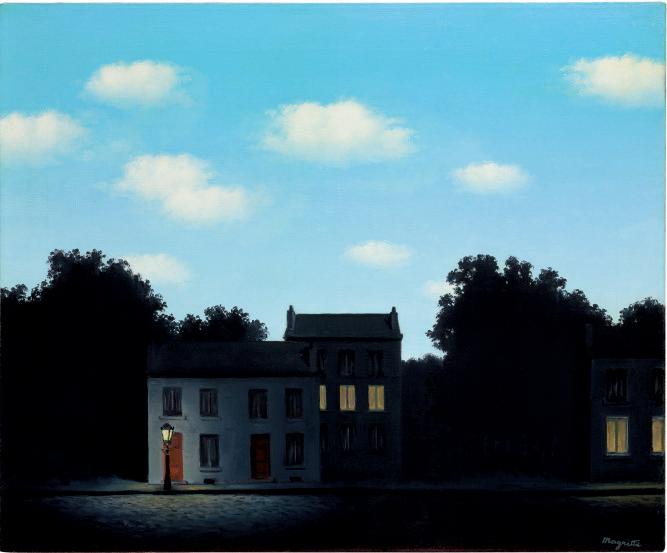

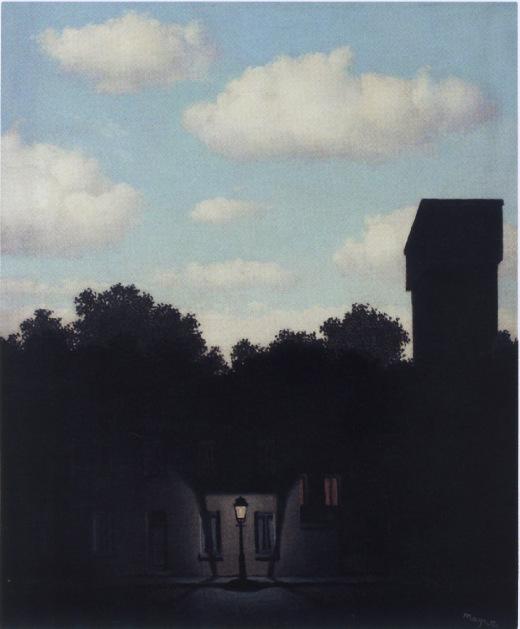

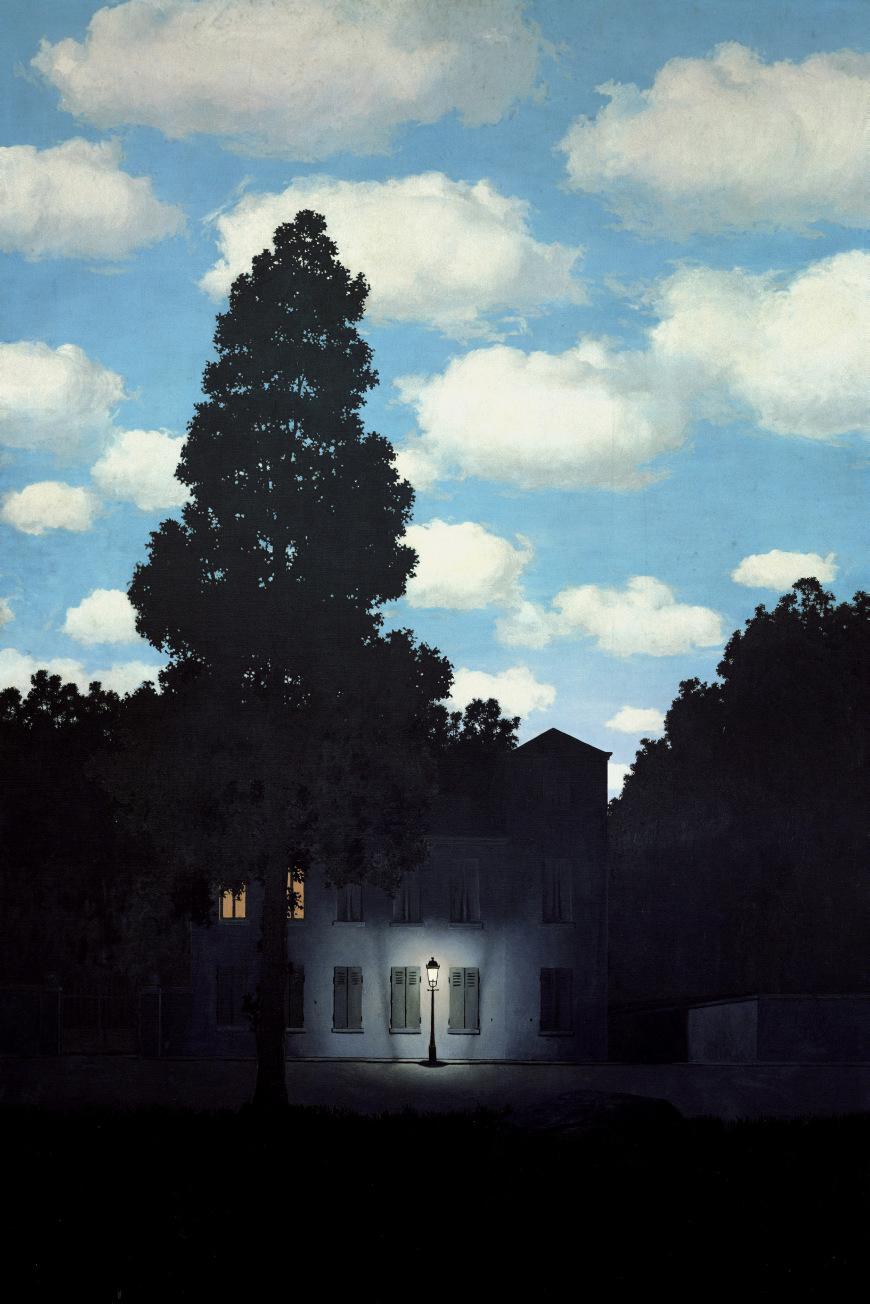

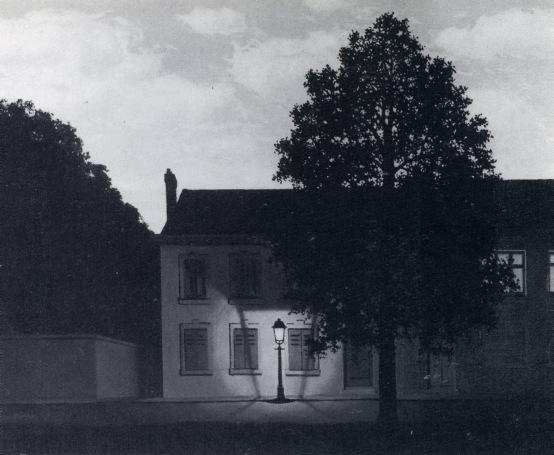

In the L’empire des lumières paintings, the sky is once again an essential tool in Magritte’s elegant disruption of our understanding of the world around us. With these works he adopts a subtle evocation of the dichotomy of night and day, simplifying the concept explored in Le Poison to create a composition that is all the more unsettling for its quiet strangeness. The first work in the series to be completed (Sylvester, no. 709; Private collection) depicts a quiet, suburban street scene, with eerily shuttered houses, some curtained windows faintly lit from within, and a single lamppost, shining forth like a beacon, the sole illumination along this darkened length of avenue. Above, the sky remains in its natural position, untouched by unexpected cracks or objects, but rather than a scattering of stars, broad daylight and white clouds fill the pale blue expanse. While at first glance the painting appears to simply present the crepuscular light of dusk, on further inspection the deep shadows and soft glow of the streetlamp suggests the sky exists in an alternate timeline to the rest of the scene. In this way, the painting pivots on the construction of a somewhat familiar, yet impossible scenario, that forces us, the viewer, to examine and question our own expectations.

There is a cinematic quality to the motif, a comparison that Alex Danchev and Sarah Whitfield highlighted in their recent biography on the artist, noting that the L’empire des lumières paintings find parallels in a sequence from Charlie Chaplin’s 1921 film The Kid. At the same time, comparisons have been drawn between the motif and “The Sleepwalker Song” in Nietzsche’s seminal Zarathustra, while some scholars have pointed to Lewis Carroll’s whimsical poem, “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” as a potential source of inspiration: “The sun was shining on the sea, / Shining with all his might: / He did his very best to make / The billows smooth, and bright—/And this was odd, because it was / The middle of the night” (quoted in A. Danchev and S. Whitfield, Magritte: A Life, London, 2021, p. 226). While the first painting was quickly purchased by Nelson A. Rockefeller in New York, the image lived on in Magritte’s imagination, and had a profound impact on his own conception of reality: “After I had painted L’empire des lumières,” the artist explained in 1966, “I got the idea that night and day exist together, that they are one. This is reasonable, or at the very least it’s in keeping with our knowledge: in the world night always exists at the same time as day. (Just as sadness always exists in some people at the same time as happiness in others). But such ideas are not poetic. What is poetic is the visible image of the picture” (quoted in S. Whitfield, Magritte, exh. cat., The Hayward Gallery, London, 1992, no. 111).

The artist’s friend Paul Nougé, the leader of the Brussels Surrealist group, is reported to have provided the title for the subject, for which the most appropriate English translation is “The Dominion of Light.” “English, Flemish, and German translators take [dominion] in the sense of ‘territory’,” Nougé noted, “whereas the fundamental meaning is obviously ‘power’, ‘dominance’” (quoted in D. Sylvester, op. cit., 1993, vol. III, p. 145). Nougé was undoubtedly sensitive to Magritte’s conviction that his paintings never expressed a singular idea, but rather were a form of stimulus that created new thoughts in the mind of the viewer. “Titles play an important part in Magritte’s paintings,” stated the poet, “but it is not the part one might be tempted to imagine. The title isn’t a

program to be carried out. It comes after the picture. It’s as if it were its confirmation, and it often constitutes an exemplary manifestation of the efficacy of the image. This is why it doesn’t matter whether the title occurs to the painter himself afterwards, or is found by someone else who has an understanding of his painting. I am quite well placed to know that it is almost never Magritte who invents the titles of his pictures. His paintings could do without titles, and that is why it has sometimes been said that on the whole the title is no more than a conversational gambit” (quoted in exh. cat., op. cit., 1992, p. 39).

Magritte discussed the idea behind his L’empire des lumières paintings in a commentary written for a 1956 television program, later published in the exhibition catalogue Peintres belges de l’imaginaire, in 1972: “For me, the conception of a picture is an idea of one thing or of several things which can be realized visually in my painting. Obviously, all ideas are not ideas for paintings. Naturally, an idea must be sufficiently stimulating for me to get down to painting the thing or things that inspired the idea. The conception of a painting, that is, the idea, is not visible in the painting: an idea cannot be seen by the eyes. What is depicted in the painting is what is visible to the eye, the thing or things that had to inspire the idea. So, in the painting L’empire des lumières are things I had an idea about—to be precise, a nocturnal landscape and a sky above in broad daylight. The landscape evokes night and the sky evokes day. This evocation of day and night seems to me to have the power to surprise and enchant us. I call this power ‘poetry.’ I believe this evocation has such a ‘poetic’ power because, among other reasons, I have always been keenly interested in night and in day, although I’ve never had a preference for one or the other. This intense personal interest in night and day is a feeling of admiration and astonishment” (quoted in K. Rooney and E. Plattner, eds., René Magritte: Selected Writings, trans. J. Levy, Richmond, 2016, p. 167).

To this day, the motif serves as a powerful illustration of Magritte’s extraordinary ability to deploy symbols of a normal, ordinary, conventional life to contradictory ends: to surprise, unsettle and reconfigure the viewer’s expectations and thus, their experience of everyday reality. It was an aspect of the L’empire des lumières series that André Breton recognized as inherently Surrealist in spirit, stating: “To [Magritte], inevitably, fell the task of separating the ‘subtle’ from the ‘dense,’ without which effort no transmutation is possible. To attack this problem called for all his audacity—to extract simultaneously what is light from the shadow and what is shadow from the light (l’empire des lumières). In this work the violence done to accepted ideas and conventions is such (I have this from Magritte) that most of those who go by quickly think they saw the stars in the daytime sky. In Magritte’s entire performance there is present to a high degree what Apollinaire called ‘genuine good sense, which is, of course, that of the great poets’” (“The Breadth of René Magritte,” in Magritte, exh. cat., Arkansas Art Center, Little Rock, 1964, n.p.).

The idea proved incredibly popular with the artist’s collectors, leading to a number of direct commissions for new versions. However, the artist was adamant that each work should evolve naturally from his own artistic pondering, writing to his dealer Alexander Iolas “I have to find a way of justifying the replica in my own mind” (quoted in C. Greenberg and D. Pih, eds., Magritte A-Z, London, 2011, p. 49). As a result, Magritte actively sought alterations between each variation, in nuance and motif, which allowed him to expand and enhance the poetic effect of the scene. Similarly, changes to the size of the canvases, alternating as well between horizontal and vertical formats, enabled the viewer to experience the impact of the juxtaposition in different ways. As Siegfried Gohr has highlighted, by repeating and reinterpreting the theme, Magritte was “arranging and rearranging visual elements until they produced a shock like a blow from a boxer’s glove—whose force, however, remained purely visual and mental” (in Magritte, exh. cat., San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2000, p. 17).

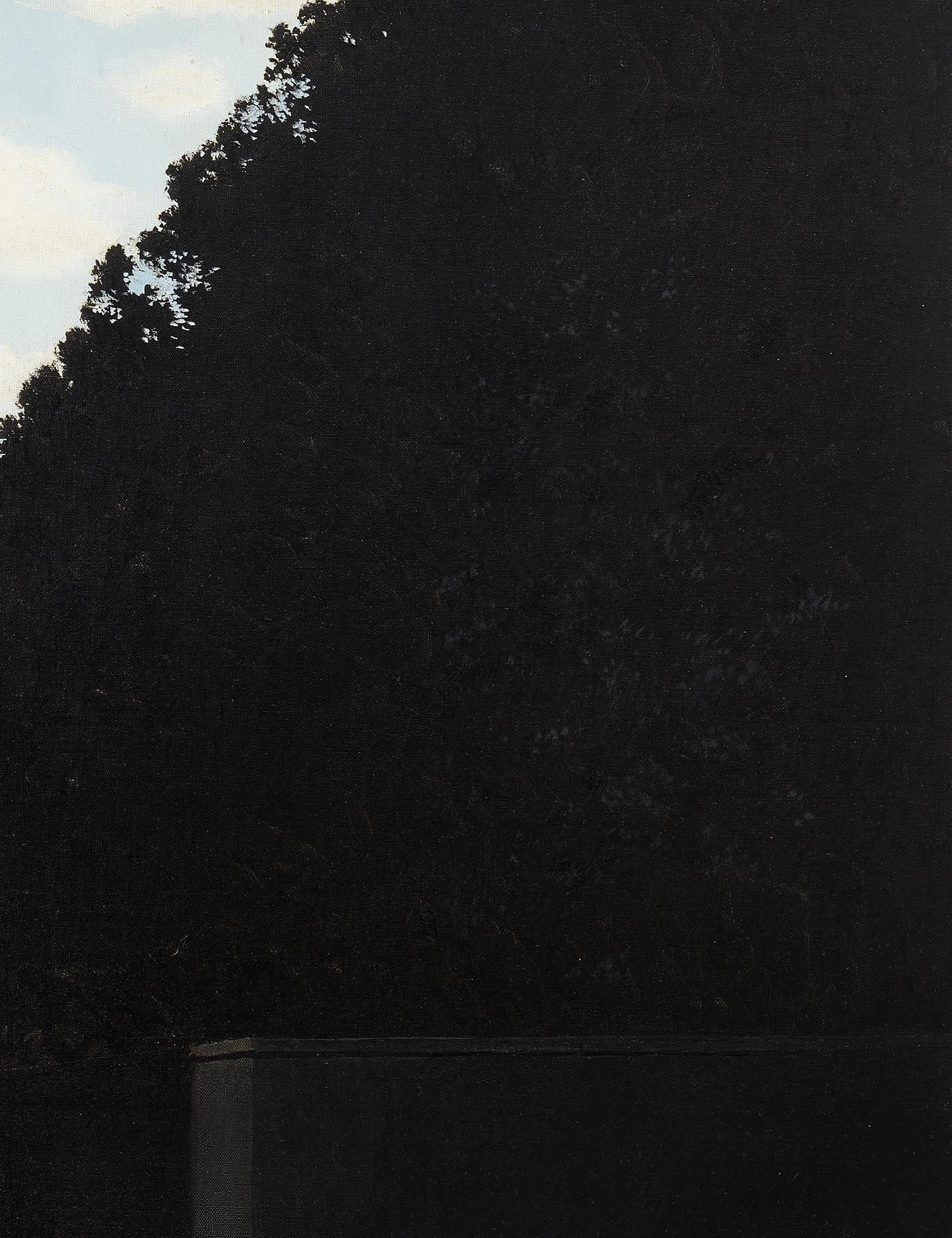

René Magritte, L’empire des lumières, 1949. Private Collection. © 2024 C. Herscovici / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“…night always exists at the same time as day.”

– RENE MAGRITTE

The second version of the L’empire des lumières theme (Sylvester, no. 723; The Museum of Modern Art, New York) was painted in June 1950, on a larger sized canvas, allowing a broader array of building façades to populate the scene. Though Magritte told Iolas he had “revealed the full strength of the idea” in this composition, he continued to revisit the L’empire des lumières motif multiple times over the course of the following fifteen years, in what may be considered Magritte’s only exploration of working in series (quoted in D. Sylvester, op. cit., 1993, vol. III, p. 157). In each iteration he made subtle alterations, experimenting with the particulars of the scene, amplifying different aspects of the landscape, subtly adjusting the colors of the sky or the density of the clouds, even expanding the sense of space and recession within the picture. Different architectural styles were portrayed in some versions, providing unexpected hints as to the location of the setting, or the socio-economic status of the residents, while the towering trees that surround the building began to take on a distinct sense of individuality and character from one canvas to the next. However, it was the extraordinary duality of night and day that remained at the heart of the L’empire des lumières paintings, a phenomenon to which the viewer appears to be the only witness.

Magritte created the present L’empire des lumières under unusual circumstances, driven in part by his growing renown and public appeal. When the Venice Biennale opened its doors to the public in June 1954, visitors were treated to a compact exhibition dedicated to the Belgian artist’s work, which featured some of his most important canvases. Discussing his visit to the event, Douglas Cooper explained the central organizing principle that lay behind this iteration of the Biennale: “For the first time, the secretary-general had attempted to give the Biennale a certain coherence; having decided that the Presidenza would undertake

special exhibitions of Arp, Ernst and Miró, he asked his committee of experts to persuade the national commissaries to take ‘Fantastic Art’ as a theme for their pavilions” (“Reflections on the Venice Biennale,” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 96, no. 619, October 1954, p. 318). While this dedicated showcase was intended to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of Surrealism, in reality the selection of artists across the Biennale was much more diverse than just those directly associated with the movement, and included works by Henri Matisse, Kees van Dongen, Paul Klee, Edvard Munch, Lucio Fontana and Nicolas De Staël.

In the Belgian Pavilion, the organizers took the decision to showcase the many different explorations of the fantastic theme across several centuries, with the mini-retrospective of Magritte’s work its centerpiece. Among the most popular pieces included in the show was L’empire des lumières (Sylvester, no. 804; The Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice), which caught the eye of the illustrious collector Peggy Guggenheim, who purchased the work directly from the exhibition. However, the painting had already been promised to three other interested parties, and suddenly Magritte found himself with the unprecedented problem of having sold the same painting multiple times over. As a result, he arranged to create three more versions of the L’empire des lumières subject for each of the disappointed parties, all of which were completed by the end of the year.

With these works, Magritte began to expand upon the mysterious, uncanny atmosphere of the scene, adding the shimmering surface of a canal or riverway to the foreground. This marked the first time that the artist had introduced a body of water to the L’empire des lumières, and the rippling reflections lend a new dimension to the imagery, the points of light within the nocturnal scene suddenly doubled. Magritte’s decision to add water to these pictures may have been inspired by his new surroundings—the artist and his wife had moved to an apartment at 207 Boulevard Lambermont in Brussels in May 1954, just a ten minute walk to Parc Josaphat, which boasted several ponds and streams. Describing the neighborhood in a letter to Iolas the following year, Magritte wrote,

Artwork:

“The poetic title has nothing to tell us, but must surprise and delight us.”

– RENE MAGRITTE

“You will see: in the evenings, it’s like being in the picture—L’empire des lumières… surrounded by gardens, and the houses looking directly on to the Boulevard Lambermont stand out against a wide sky” (quoted in D. Sylvester, op. cit., 1993, vol. III, p. 63). In the present work, the glow from the singular lamppost is softened, granting the composition a greater sense of warmth, which is echoed in the subtle illumination from the windows in the upper story of the house. As a result, the reflections in the water are more clearly discernible to the viewer, the outlines of the lamppost and the windows crisper as they appear mirrored in the water’s surface, creating the impression that perhaps another world hovers on the very edge of our own.

At its heart, the mystery of the L’empire des lumières lies in its subtle subversion of reality—by anchoring his compositions within the most ordinary, quotidian of scenes, Magritte offers a profound meditation on the universe’s endless capacity to surprise us. It is this quality that led James Thrall Soby to write: “Magritte’s art is far-fetched in both the literal and the figurative sense of the word, and deliberately so. This art comes from deep regions of the perceptive mind, where only true artists, poets or musicians can breathe. Once surfaced, its equivocations remain inspired. It should be our startled purpose, not to probe, but to respect and enjoy them” (René Magritte, exh. cat., The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1965, p. 19).

“After I had painted L’empire des lumières, I got the idea that night and day exist together, that they are one. This is reasonable, or at the very least it’s in keeping with our knowledge: in the world night always exists at the same time as day. (Just as sadness always exists in some people at the same time as happiness in others). But such ideas are not poetic. What is poetic is the visible image of the picture.”

– RENE MAGRITTE

L'empire des lumières

signed 'Magritte' (lower right); signed again, dated and titled '"L'Empire des Lumières" Magritte 1954' (on the reverse)

oil on canvas

57Ω x 44√ in. (146 x 114 cm.)

Painted in 1954

Estimate on Request

PROVENANCE:

Willy Van Hove, Brussels (acquired from the artist, 1954, until at least 1964).

Byron Gallery, New York.

Acquired from the above by the late owner, 8 June 1968.

EXHIBITED:

Mons, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Hainaut cinq, March 1964, no. 19 (with inverted dimensions).

New York, Byron Gallery, René Magritte, November-December 1968, p. 26, no. 16 (illustrated in color, p. 27).

Southampton, The Parrish Art Museum, René Magritte: Poetic Images, August-September 1979, no. 25. Tokyo, Isetan Museum of Art, Surrealism, February-March 1983, no. 51 (illustrated in color; detail illustrated in color on the cover).

Lausanne, Fondation de l'Hermitage and Munich, Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung, René Magritte, June 1987-February 1988, p. 200, no. 89 (illustrated, p. 200; illustrated again in color, p. 134).

The Montréal Museum of Fine Art, Magritte, June-October 1996, pp. 50 and 167, no. 84 (illustrated, p. 50; illustrated again in color, p. 167).

Paris, Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume, Magritte, February-June 2003, p. 185 (illustrated in color, p. 184).

Vienna, BA-CA Kunstforum and Basel, Fondation Beyeler, René Magritte: Der Schlüssel der Träume, August-November 2005, pp. 150-151 and 200, no. 77 (illustrated in color, p. 151).

New York, Blain Di Donna, René Magritte: Dangerous Liaisons, October-December 2011, pp. 32 and 73 (illustrated in color, p. 33; detail illustrated in color on the cover).

LITERATURE:

P. Devlin, "Space Venture: The Ahmet Ertegun Town House in New York, 'Why Imitate When Now is New'?" in Vogue, 15 August 1969, p. 129 (illustrated in color in situ at the Ertegun Manhattan residence).

S.M.L. Aronson, "Classical Cool: Mica and Ahmet Ertegun's town house reflects a discerning couple's original taste" in House & Garden, March 1987, pp. 100 and 218 (illustrated in color in situ at the Ertegun Manhattan residence, p. 101).

P.A. Caracciolo, "Ahmet y Mica Ertegun: La Fuerza y La Tersura" in Cases & Gente, vol. 7, no. 71, October 1992, p. 57 (illustrated in color in situ at the Ertegun Manhattan residence).

D. Sylvester, ed., René Magritte: Catalogue Raisonné, Oil Paintings, Objects and Bronzes, 1949-1967, London, 1993, vol. III, p. 233, no. 809 (illustrated).

G. Ollinger-Zinque, Magritte in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, Brussels, 2005, p. 64 (illustrated in color).

S. Gohr, Magritte: Attempting the Impossible, Paris, 2009, p. 223, no. 300 (illustrated in color, p. 222).

C. Haskell, ed., René Magritte: The Fifth Season, exh. cat., San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2018, p. 44 (illustrated in color, fig. 2).

E. Taylor, “'I Hate Clutter': The Chic, Cultivated Interiors of Mica Ertegun, As Seen in Vogue" in Vogue, www.vogue.com, 6 December 2023 (accessed 9 October 2024; illustrated in color in situ at the Ertegun Manhattan residence, pl. 10).

On the 19 June 1954, the twenty-seventh iteration of the Venice Biennale opened to the public, filling the Giardini with visitors eager to see the latest and most dynamic contemporary art on offer. To celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of the founding of the Surrealist movement, the organizers had suggested a unifying theme for the exhibition, focusing on the concept of “the fantastic.” The event proved to be a watershed moment for Surrealism, cementing its position in the history of modern art, alongside the likes of Fauvism, Cubism and Expressionism. When the curatorial topic for the Biennale was announced, the commissioners for the Belgian pavilion conceived of an ambitious exhibition to showcase the breadth and variety of Flemish art, from the 1500s through to the twentieth century. Central to their plans were the paintings of Belgium’s greatest living proponent of the Surrealist spirit—the unique stylings of Monsieur René Magritte.

In the wake of the Second World War, the Biennale di Venezia was searching for a new identity and focus, which would counter the perception of the show that had taken root during the Fascist period. Throughout the previous decade, the event had been heavily influenced by the political climate within Italy, with the Fascist Union of Fine Arts championing a more traditional, patriotic style of painting. The governing body focused on showcasing art that celebrated a Utopian, imperialistic style, favoring monumentality, classicism and heroic subjects, as well as Futurist artists loyal to the regime. As early as 1936, several international countries had chosen to halt their participation in the event, including the USA and the United Kingdom, due to the rising political tensions in Europe, and between 1938 and 1942,

RENE MAGRITTE L’empire des lumières

the festival’s top prizes were awarded to countries on the basis of political allyship. Following the outbreak of war, the situation became even more pronounced. In 1942 Mussolini used the event as an unabashed propaganda tool to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of Fascism in Italy, staging a large exhibition dedicated to military art— the vacant British pavilion became a showcase for the Army, the United States’ building was dedicated to the Navy, and the French exhibition space transformed into the Air Force pavilion—as well as documentary views of hospitals and submarine bases, heroic effigies to the country’s leadership and artworks celebrating the might of Italian power.

Following the end of the conflict, the Venetian authorities set out to overhaul and transform the Biennale into a modern, outward looking event, which would embody “the new climate of liberation” sweeping the country (R. Pallucchini, quoted in L. Alloway, The Venice Biennale, 1895-1968 – from salon to goldfish bowl, London, 1969, p. 133). In doing so, they sought to not only educate the public about modern art and repair the cultural gaps of the Fascist years, but also to refocus attention on great artists who had been forgotten, ignored or persecuted during the turbulent 1930s and 1940s. The art historian Rodolfo Pallucchini was elected to the post of Secretary General of the Biennale and, though a specialist in Renaissance art with limited knowledge of the twentieth century avant-garde, he proved integral to the redirection of the event through his tenure. For example, it was Pallucchini who introduced the idea of staging a series of retrospectives dedicated to the key movements, ideas and styles that had transformed art-making through the previous fifty years, from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, to Cubism, Abstraction and Expressionism. Paying homage to the past while also celebrating the contemporary moment, Pallucchini’s curatorial approach focused on artistic styles and ideas that crossed borders, eschewing the overt nationalism of previous iterations of the Biennale, and instead drawing attention to the themes, ideas and subjects that united artists across geographical and ideological boundaries.

As a result, the 1948 Biennale—the first time the event was staged following the cessation of the conflict—was suffused by a spirit of renewal and reform. Austria introduced the art of Egon Schiele to the Italian public, while France showcased paintings by Marc Chagall, Georges Braque and Georges Rouault alongside the sculptures of Aristide Maillol, and the British pavilion hosted masterpieces by J.M.W. Turner alongside recent pieces by Henry Moore. A large-scale survey of Impressionism was held at the empty German pavilion, featuring paintings by Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Paul Cezanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin, while the central pavilion staged a series of special exhibitions, including one dedicated to the artists labelled as “Entartete” or “Degenerate” under Hitler’s regime, and a special display of Pablo Picasso’s work. “The 1948 Biennale was like opening a bottle of Champagne,” Vittorio Carrain recalled. “It was the explosion of modern art after the Nazis had tried to kill it” (quoted in K.P.B. Vail, Peggy Guggenheim: A Celebration, exh. cat., The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1998, p. 77).

Perhaps most importantly, Pallucchini invited Peggy Guggenheim to show her collection of ground-breaking modern art as part of the festival, taking over the Greek pavilion, which was unoccupied that year due to the ongoing civil war in the country. The idea had been suggested by the Venetian artist Giuseppe Santomaso, who Guggenheim had met shortly after her arrival in the city. “In Italy, the Surrealists, Brancusi, Arp, Giacometti, Pevsner and Malevich had never been heard of,” Guggenheim recalled in her autobiography Out of this Century, explaining these artists were only known to a select few members of the Italian avant-garde through clandestine copies of Minotaur and Cahiers d’Art, which had made their way across the border from Paris (Out of this Century: Confessions of an Art Addict, London, 1980, p. 327). After years of disuse, the Greek pavilion was in need of extensive refurbishment, and the renowned architect Carlo Scarpa was commissioned to carry out the project. Within his elegant redesign, Guggenheim spent three days working on the display for her collection: “Fortunately, I was given a free hand and a lot of efficient workmen, who did not mind my perpetual changes,” she wrote. “We managed to get the show finished in time, and though it was terribly crowded it looked gay and attractive, all on white walls…” (ibid.).

“My exhibition had enormous publicity and the pavilion was one of the most popular of the Biennale.”

– PEGGY GUGGENHEIM

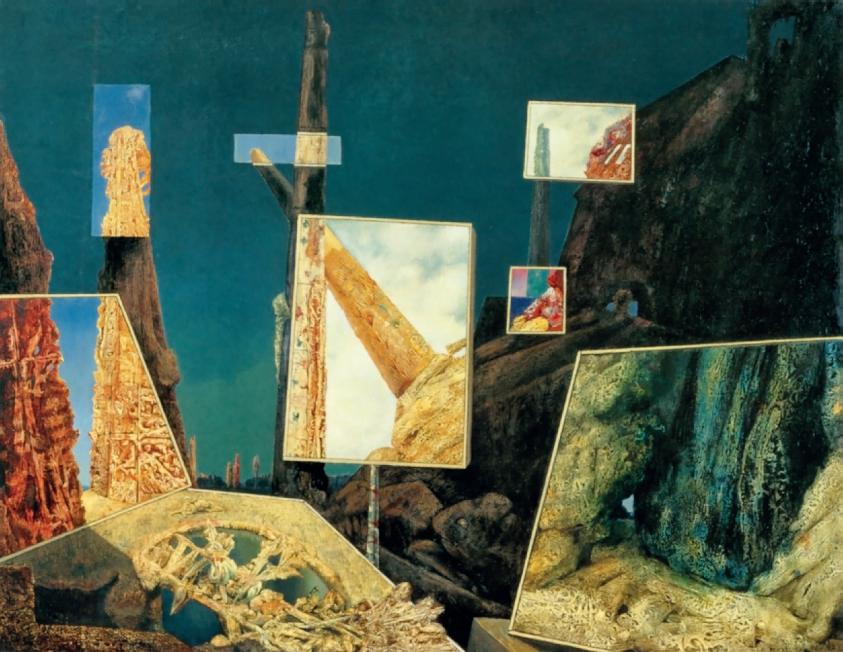

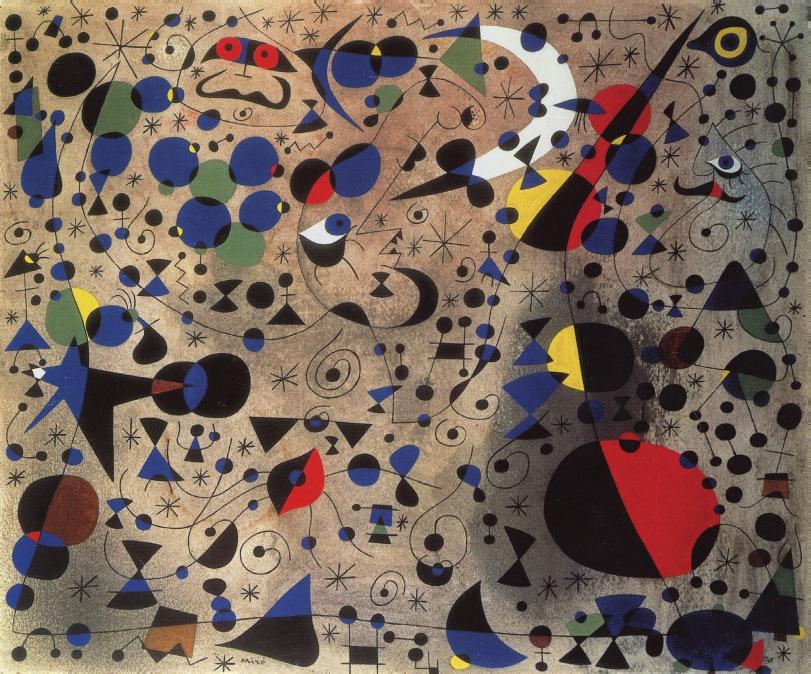

La Collezione Peggy Guggenheim, as the exhibition was known, was a defining event of that year’s Biennale, featuring over seventy individual artists that together offered an extraordinary, comprehensive survey of avant-garde, abstract and Surrealist art. The space was loosely divided into three interconnecting sections—in the first, Guggenheim arranged a group of works by Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, Georges Vantongerloo, Alexander Calder and Constantin Brancusi; in the second, a multifaceted review of Surrealism was on show, with sculptures by Alberto Giacometti and Jean Arp displayed next to paintings by Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, Yves Tanguy and Magritte; the final space showcased a new generation of young American painters, including Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still, many of whom were showing for the first time outside of the USA.

In her article about the 1948 Biennale for British Vogue, Lee Miller singled out Guggenheim’s exhibition for the highest praise, labelling it the “most sensational” pavilion of the year and commending the collector’s curatorial choices (“The Venice Biennale Art Exposition,” in Vogue, 1 November 1948, London, pp. 193-195). In a series of photographs taken during her visit to the pavilion, Miller recorded an enthusiastic meeting between Guggenheim and the great Italian art critic Lionello Venturi, during which Venturi was inspired to “swing the Calder Mobile for half an hour” (ibid.). “My exhibition had enormous publicity and the pavilion was one of the most popular of the Biennale,” Guggenheim proudly recalled. “I was terribly excited by all this, but what I enjoyed most was seeing the name of Guggenheim appearing on the maps in the Public Gardens next to the names of Great Britain, France, Holland, Austria, Switzerland, Poland… I felt as though I were a new European country” (op. cit., p. 329). Indeed, the success of the Guggenheim Collection with the public, and its cutting-edge selection of artists had a profound impact on Pallucchini’s view of modernism, opening his eyes to new movements, artists and ideas, that would directly influence the curatorial direction of the Biennale during his time as Secretary General.

While the 1950 and 1952 Biennales had focused on Fauvism, Cubism and Futurism, for the 1954 event Pallucchini envisioned an ambitious survey exhibition dedicated to Fantastic Art and Surrealism, spread across several rooms of the central pavilion. His proposal included plans for a large display celebrating the multiple different strands of the movement, which would be shown alongside a retrospective of Gustave Courbet, and an exhibition dedicated to Italian art of the eighteenth century. As well as sections devoted to documentation and archival material relating to the DADA movement, Pallucchini wished to include a diverse array of artists in the exhibition, from William Blake, Gustav Moreau, and Odilon Redon, to Salvador Dalí, Marcel Duchamp, André Masson, Francis Picabia, and Max Ernst. The aim was to re-situate Surrealism in the history of art, contextualizing it in relation to its artistic predecessors in Symbolism and the Romantic period. In this way, Pallucchini appears to have drawn inspiration from the model of Alfred J. Barr’s legendary show, Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism, at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, which had caused a sensation when it opened in 1936.

Pallucchini’s concept, however, proved controversial. Critics, curators, art historians, politicians and even members of the clergy, protested vehemently against the suggestion, labelling the movement and its most famous protagonists as perverse, immoral and a danger to society. Even in his introductory essay in the catalogue for the Biennale, Pallucchini himself admitted, “There is no doubt that the Italian temperament is very far from the surrealist adventure” (quoted in J. Drost, “« Trop dangereux, trop inquiétant, trop incertain ». Le surréalisme à la XXVIIe Biennale de Venise en 1954,” in Drost et al., eds., Le surréalisme et l’argent, Heidelberg, 2021, p. 364). Claiming a lack of space within the central pavilion, plans for the Surrealist exhibition were thus dramatically scaled back, and instead, the organizers chose to spotlight just three artists—Max Ernst, Jean Arp and Joan Miró, each of whom were awarded one of the Biennale’s top prizes that year. After working in forced isolation during the Second World War, this recognition and its associated awards proved to be an enormous boon to their careers, bringing each of the artists to the very forefront of the international art world. André Breton, however, was incensed that he hadn’t been invited by the organizers to curate the Surrealist show, and decried the Biennale’s narrow approach, as well as their failure to recognize the essential diversity of Surrealism as a movement.

In conjunction with the central showcase devoted to Ernst, Arp and Miró, the Biennale’s organizing committee issued a formal invitation to the thirty-one participating countries to follow the common theme of Surrealism in each of their national pavilions, encouraging the commissioning bodies to select artists whose work carried a “surrealist taste” (quoted in ibid.). The aim was to establish an overarching curatorial concept that would provide a sense of unity across the different pavilions, while also fulfilling Pallucchini’s initial goal to stage a historical showcase of Surrealist art. The response from the various national pavilions, however, was mixed—some appear to have ignored the suggestion entirely, including Egypt, Denmark, Italy, Japan, and Brazil, while others made only a nominal reference to it. For example, the German pavilion showed a mixture of works by Paul Klee and the Bauhaus artist Oskar Schlemmer, while the British pavilion juxtaposed the minimalist abstract paintings of Ben Nicholson with the daring compositions of Francis Bacon. The French pavilion took an even more unusual approach, dividing its exhibition into four sections—while the first room was dedicated to Fauvism, the third to Abstract and Informal works, and the fourth to the cubist tradition, only the second room responded to the theme of “Fantastic Art,” with a focus on young artists such as Victor Brauner and André Masson, rather than those associated with the founding of the Surrealist movement in the 1920s.

In contrast, the organizers of the Belgian pavilion fully embraced the curatorial thread, staging an exhibition that showcased the many different explorations of the fantastic theme through several centuries of art making. Across the walls of the space hung paintings that encompassed over four hundred years of art history, from the hallucinatory visions of Hieronymus Bosch and the unsettling scenes of Pieter Huys’s canvases, through to the uncanny compositions of James Ensor and the dreamworlds of Paul Delvaux. The centerpiece of the pavilion was a mini-retrospective of Magritte’s work, featuring twenty-four paintings, ranging from his earliest engagements with the Parisian Surrealists in 1926, right up to his most recent compositions from the opening months of 1954. While Magritte had featured in Peggy Guggenheim’s exhibition at the Biennale in 1948, and had enjoyed a dedicated solo-show in Rome in 1953, this was his first opportunity to show a large selection of his most important paintings together in the

Jean Arp, Venice Biennale, 1954.

Photo: Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche / Getty Images.

Artwork: © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

“I am showing in Venice, in a room entirely devoted to my work…”

– RENE MAGRITTE

country. The invitation to exhibit at the Venice Biennale also reflected the significant shifts that were occurring in his reception in his homeland of Belgium during this period, as Magritte was increasingly lauded as the country’s leading modern artist.

For much of the first half of the year, Magritte had been immersed in the planning for a retrospective of his work at the Palais des BeauxArts in Brussels, which ran from 7 May to 1 June 1954. The artist was heavily involved with the selection of works for the show, sending its curators Robert Giron and E.L.T Mesens numerous lists advising them of the most important paintings from each of the various stages of his career thus far. The show at the Biennale was essentially a condensed version of the exhibition in Brussels, with the 24 works travelling from the Palais des Beaux-Arts directly to Venice. However, it appears that Magritte was unhappy with the final group of works that were chosen for the Belgian Pavilion—in a postcard dated 10 April 1954, the artist lamented “I have received the list for Venice. My opinions have been completely disregarded… This is amusing, sad and perfectly in keeping with respect for confusion” (quoted in D. Sylvester, ed., René Magritte: Catalogue Raisonné, Oil Paintings, Objects and Bronzes, 1949-1967, London, 1993, vol. III, p. 53). Nevertheless, when the exhibition opened in mid-June, Magritte was represented by a rich group of his most celebrated compositions, the condensed display offering a survey of his quintessential motifs and iconic pictorial concepts.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the uproar that had preceded the event’s opening, the critical response to the 1954 Biennale was largely negative. Traditionalists blasted the provocative work of artists such as Dalí, claiming his images were immoral and blasphemous, caricatures in the Italian press mocked Arp’s sculptures, while Miró’s paintings were

described as “blobs and squiggles” by one American critic (“Under the Four Winds,” in Time, vol. 68, no. 6, 28 June 1954, pp. 77-78). Even the more progressive journalists, such as Douglas Cooper, lamented the lack of cohesion across the Biennale, writing that “there was neither a possibility of studying the role of the fantastic element in European pictorial art during the last 100 years, nor of assessing Surrealism’s contribution as a whole…” (“Reflections on the Venice Biennale,” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 96, no. 619, October 1954, p. 318).

Within the Belgian pavilion, Paul Delvaux was accused of being a vulgar pornographer, while Magritte’s style was dismissed by a younger, more revolutionary group of Surrealist artists as being outdated. However, the exhibition succeeded in drawing over 170,000 visitors during its run, and the commercial response proved positive, with a number of the Surrealist artists reporting sales. As such, the event set an important marker in the international art market, enhancing and broadening the taste for Surrealism among European audiences and collectors, that would have a lasting impact through the rest of the twentieth century.

Among the undisputed highlights of Magritte’s exhibition was the enormous L’empire des lumières (Sylvester, no. 804; The Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice), which was matched in its scale by only two other works in the Venice show—L’assassin menacé (Sylvester, no. 137; The Museum of Modern Art, New York) and Le monde invisible (Sylvester, no. 805; The Menil Collection, Houston). However, within weeks of the Biennale opening, the artist found himself caught in an unexpected dilemma—he had promised the work to three different interested buyers. As he explained in a letter to Jan-Albert Goris on 21 July, “I have had a visit from Iolas, who bought a number of pictures from me. It is quite complicated from certain points of view: two big pictures on show at the Venice Biennale, and one of which was ‘reserved’ by a collector here and by the Museum [the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, in Brussels]. I have just heard that the Museum has made up its mind (too late unfortunately), and wants to buy L’empire des lumières. As I was in a state of uncertainty, and as I hadn’t committed myself to refuse sales of pictures about which there had already been some financial discussions, and as, in addition, Iolas paid me a flying visit late at night, it was difficult for me to please everybody…” (quoted in D. Sylvester, op. cit., 1993, vol. III, p. 55).

“The landscape suggests night and the skyscape day.”

– RENE MAGRITTE

Along with Iolas and the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, the Belgian collector Willy Van Hove had placed a reserve on the work when it was shown in Brussels. Faced with the prospect of disappointing multiple important patrons, Magritte turned to Mesens for advice. In the end, the painting found a different buyer altogether—Peggy Guggenheim, who purchased L’empire des lumières directly from the Biennale for 1,000,000 lire. Though not directly involved in the 1954 Biennale, the collector’s palazzo had become an important hub for artists, dealers and collectors visiting the exhibition. Her guest book from 1954 includes entries by Arp and his wife Marguerite, as well as Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning, and Guggenheim visited the various pavilions on multiple occasions during the festival’s run. According to correspondence between Magritte and Mesens, Guggenheim’s interest in the canvas had been prompted by a not-so-subtle hint from the latter: “it was I, after my last visit to Venice, who wrote to Peggy saying that your work was inadequately represented in her very considerable collection,” Mesens explained. “She replied by return that I was right. And she took action” (quoted in ibid., p. 56).

As a result, Magritte arranged to create three more versions of the L’empire des lumières subject to appease each of the disappointed parties, all of which were completed by the end of the year. While the painting intended for Iolas (Sylvester, no. 814; The Menil Collection, Houston) was created on a canvas 130 x 95 cm, the other two from this group— the present work, made for Van Hove, and the example for the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts in Brussels—were executed on a slightly larger scale, both standing at 146 x 114 cm (Sylvester, nos. 809 and 810). With these works, Magritte began to expand upon the mysterious, uncanny atmosphere of the scene, adding the shimmering surface of a canal or riverway to the foreground, enhancing the visual poeticism of the image. For Magritte, the Venice Biennale thus represented more than a formal acceptance into the canon of twentieth century art—it provided him with an unexpected creative spur, prompting him to revisit and expand once again his iconic motif of the L’empire des lumières.

“…each moment is an unforeseeable appearance, each moment demonstrates the absolute mystery of the present.”

– RENE MAGRITTE

The L’empire des lumières Series (1949-1965)

“I have a very limited vocabulary: nothing but ordinary, familiar things. What is “extraordinary” is the connection between them.”

– RENE MAGRITTE

The L’empire des lumières Series (1949-1965)

MICA: THE COLLECTION OF MICA ERTEGUN

L’empire des lumières

signed ‘Magritte’ (lower right); signed again, dated and titled ‘”L’Empire des Lumières” Magritte 1954’ (on the reverse) oil on canvas

57Ω x 44√ in. (146 x 114 cm.)

Painted in 1954

Sylvester, no. 809.

L’empire des lumières II on view in the exhibition, René Magritte, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 15 December 1965 – 27 February 1965.

Photo: © The Museum of Modern Art/ Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

Artwork: © 2024 C. Herscovici / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

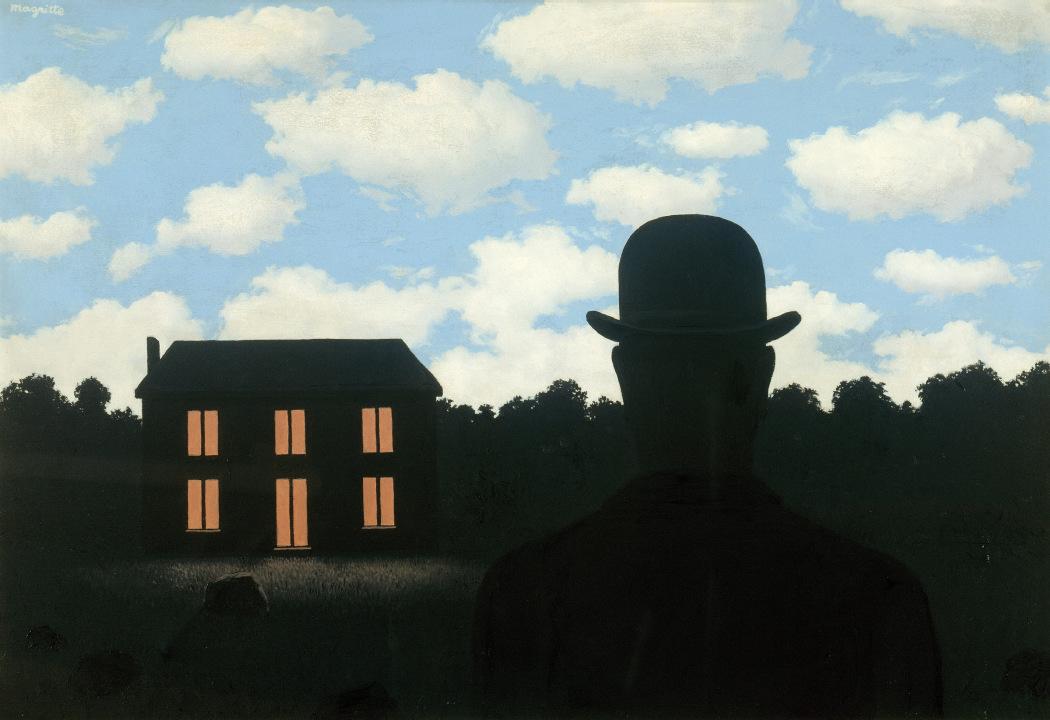

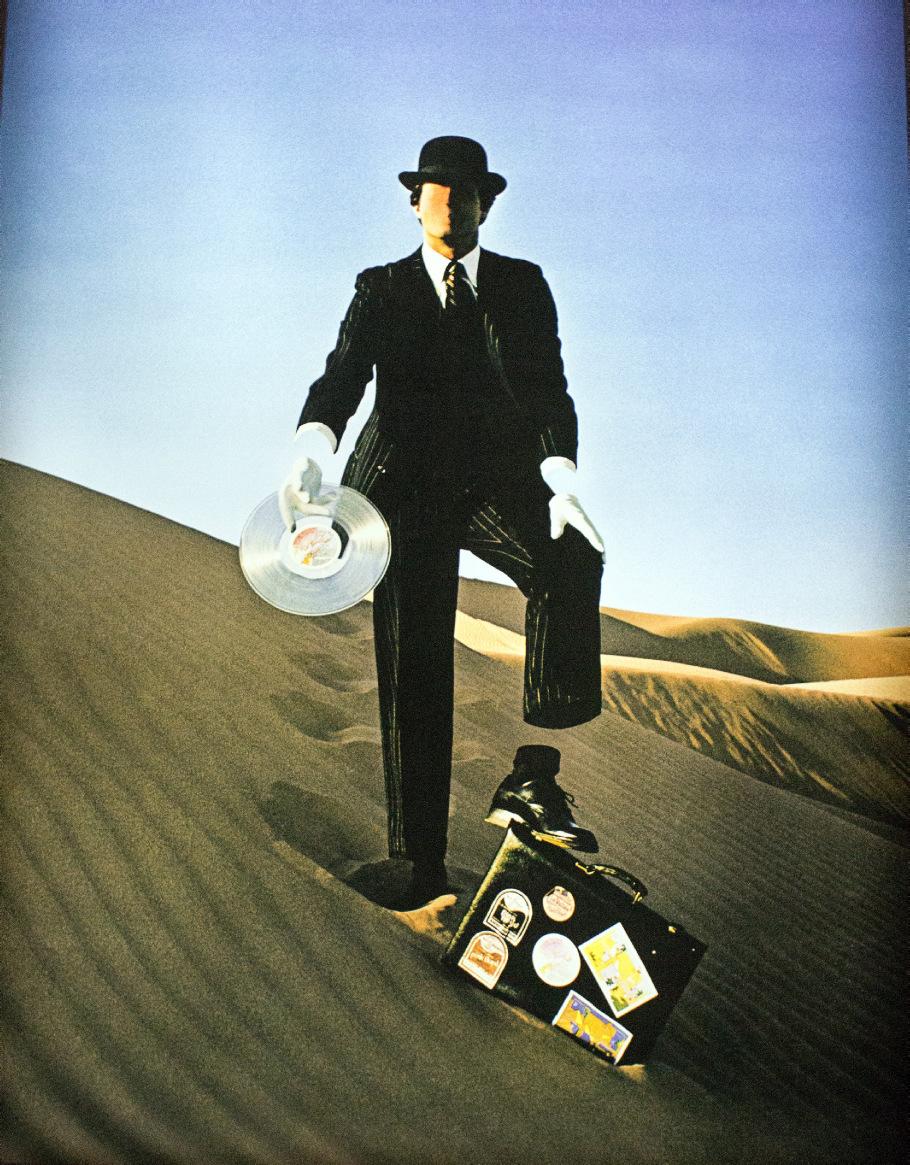

Throughout the past century, René Magritte’s paintings have captivated the public with their simple, evocative imagery and playful subversion of expectations. Magritte was profoundly aware of the inherent power of an idea, its ability to take root in the imagination of the viewer and transform their perception of the world. “I firmly believe that a beautiful idea is ill served by being presented in an ‘interesting’ way,” the artist proclaimed, “the interest is in the idea” (quoted in Magritte/ Torczyner: Letters between Friends, trans. R. Miller, New York, 1994, p. 18). Over the years, the Belgian Surrealist’s images seeped into the public consciousness, and his influence was widespread, permeating all aspects of pop culture, from music and fashion, to film and television. His iconic leitmotifs have inspired everything from episodes of The Muppets to the album covers of Pink Floyd, with each iteration and quotation reinterpreting Magritte’s paintings for new audiences.

Numerous companies also looked to Magritte’s example when conceiving of simple, effective logos that would capture people’s attention—for example CBS, one of the United States’ largest television networks, appeared to invoke the artist’s 1929 painting Le faux miroir (Sylvester, no. 319; The Museum of Modern Art, New York) in its 1951 rebrand, which juxtaposed a graphic eye against a cloud-filled sky, while the Belgian airline Sabena adopted Magritte’s famed oiseau de ciel, or sky-bird, for its advertising campaigns in the late 1960s and 1970s, even painting the motif on the company’s fleet of planes. Similarly, it was a

“What I love about Magritte is he turned the world upside down and inside out in terms of meaning and significance.”

– PAUL MCCARTNEY

Magritte painting that inspired the logo and moniker for The Beatles dedicated multi-media company, Apple Corps, in early 1968. “I had this friend called Robert Fraser, who was a gallery owner in London,” Paul McCartney recalled in a 1993 interview. “I told him I really loved Magritte. We were discovering Magritte in the sixties, just through magazines and things. And we just loved his sense of humor…” (radio interview with Johan Ral for Studio Brussel, 17 October 1993). One day, so the legend goes, Fraser brought a painting to McCartney’s house and, not wishing to interrupt some filming that was taking place, he placed the canvas on the dining room table and left. When McCartney came inside, he was astounded to find it sitting there, waiting for him: “It was an apple… It just had written across it ‘Au revoir,’ on this beautiful green apple… it was like wow! What a great conceptual thing to do” (quoted in ibid.).

The work in question was Magritte’s 1966 composition Le jeu de mourre (Sylvester, no. 1051; Private collection), which became an integral part of McCartney’s collection thereafter. It provided the initial visual prompt for the logo of their newly-formed company—which encompassed The Beatles’ ventures in film, publishing, merchandise, and music— with the group settling on a close-up photograph of a bright green Granny-Smith apple. The image would feature on each of The Beatles’ records from Hey Jude onwards, with the B-side of the vinyl including another photograph of the apple sliced down the middle, revealing its inner core. In turn, The Beatles’ nod to Magritte would inspire another group of industry disruptors, as they brainstormed ideas for a symbol to best represent their new corporation—Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak’s bourgeoning Apple Computers.

In many ways, it was the inherent accessibility of many of Magritte’s motifs, their initial familiarity and use of common-place objects and scenes, that proved the key to their success. They provided a visual anchor for the viewer, and enhanced Magritte’s ability to surprise, shock and delight audiences around the world with his unexpected images. Nowhere is this perhaps more true than in the profound, poetic mystery at play in the L’empire des lumières series. The motif quickly became synonymous with Magritte, thanks, in part, to the multiple versions the artist created in both gouache and oil, which featured in numerous international exhibitions and retrospectives dedicated to the artist’s work. In particular, the generous donation of Magritte’s second version of L’empire des lumières to The Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1951 by John and Dominique de Menil had an enormous impact on generations of young creatives in the United States.

For the maverick film director William Friedkin, his encounter with Magritte’s L’empire des lumières offered an intriguing solution to one of the most important scenes of his latest project, an adaptation of William Peter Blatty’s controversial horror novel, The Exorcist. “In the novel, Blatty’s description of Father Merrin arriving outside the home of the child’s mother says he was standing under a streetlight in a misty glow, ‘like a melancholy traveler frozen in time’,” Friedkin recalled. “I had to find a way to visualise that” (quoted in J. Ressner, “Devil’s Playground,” Director’s Guild Quarterly, Fall, 2008; https://www.dga.org/Craft/ DGAQ/All-Articles/0803-Fall-2008/Shot-to-Remember-The-Exorcist [accessed 30 September 2024]). Friedkin often found inspiration in art, recalling the dramatic chiaroscuro effects of artists such as Caravaggio and Rembrandt in his cinematography, or the Paris street scenes of Gustave Caillebotte and Georges Seurat in the addition of small, incidental moments to his sequences. “Images stick in my minds eye,” he explained. “I’ll see something and it’ll go into a mental file, and occasionally I’ll have use for it” (speaking in Leap of Faith (2020), dir. by A.O. Philippe, Shudder Studios, [53.56-54.06]).

“[L’empire des lumières] had a profound effect on me, and I decided to put a figure in it… It’s remained forever the iconic image of The Exorcist.”

– WILLIAM FRIEDKIN

While Friedkin had first seen Magritte’s painting at The Museum of Modern Art, it was the version of the motif housed in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts in Brussels that provided the direct inspiration for The Exorcist. “I saw a powerful light shining from Regan’s bedroom window, down to a silhouetted figure standing near the streetlamp. The man would be Father Merrin [played by Max von Sydow] arriving at the Georgetown house,” he explained. “Magritte’s painting is an example of how he juxtaposed realistic but unrelated objects. In the film it became a real house, on a real street, an upstairs bedroom in which a young girl is possessed by a demon” (The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir, New York, 2013, pp. 261-262). Noting the similarities between the street in Magritte’s painting and the houses that lined Prospect Avenue in Georgetown, Washington, D.C., Friedkin decided to shoot the film in this quiet residential location. He and his team then began to explore practical effects and lighting techniques that could invoke Magritte’s iconic image.

“To achieve the effect of light from the bedroom window,” Friedkin recalled, “we had to construct a platform behind the extension built onto Mrs. Mahoney’s house. On the platform was an arc light, aimed directly at Merrin as he emerged from a taxicab. Prospect Avenue was wetted down and we used a fog machine to enhance the mood. We put our own streetlamp in front of the house… We set aside a full day and night to light this one shot and photographed it the next night in one take” (ibid.). Evoking the atmosphere and mood of Magritte’s Surrealist masterwork, Friedkin infused this simple, ordinary moment with a powerful sense of the uncanny, enhancing the feeling of foreboding that precedes the grand reveal of what lies inside this unassuming house.

The imagery from this pivotal scene became the centerpiece of the film’s marketing campaign when it was released in December 1973, appearing on posters, billboards, and later, the film’s VHS and DVD covers. However, Freidkin had to push for it to be included in the studio’s plans. He disagreed with the head of Warner Brother’s marketing department, Dick Lederer, who preferred the sensationalist image of a child’s bloodied hand clutching a crucifix, above the phrase “For God’s Sake, Help Her.” Friedkin was adamant that Lederer’s choice would hurt the film, and that instead, the inherent mystery of Max von Sydow’s silhouette, standing alone on the street, would prove more powerful, telling Lederer that “the ad should understate the film’s content” (quoted

in A. Danchev and S. Whitfield, Magritte: A Life, London, 2021, p. 335). As Alex Danchev and Sarah Whitfield noted, “Like Magritte, Friedkin understood the power of understatement” (ibid.).

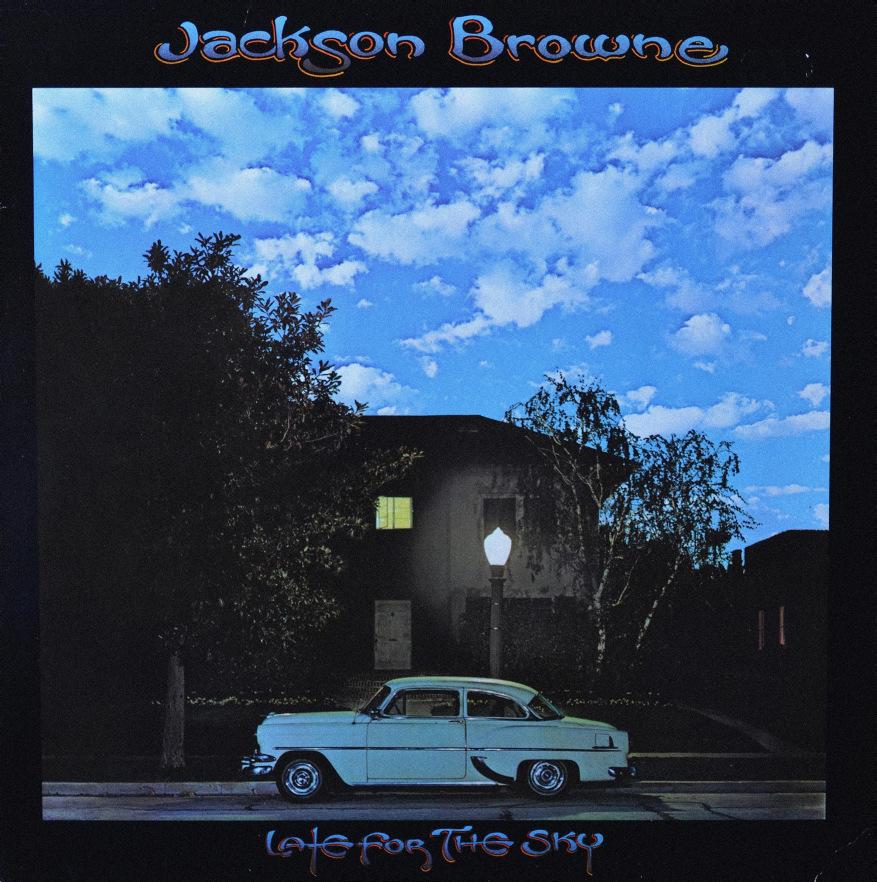

While Friedkin had valued the unsettling nature of the L’empire des lumières series, the singer-songwriter Jackson Browne appears to have been more intrigued by profound sense of magic within the paintings. For his third album, Late For The Sky, Browne proposed a photographic image that played with Magritte’s motif, transporting the scene to a typically Californian setting. According to the graphic artist Bob Seidemann who was commissioned to create the album sleeve, Browne arrived at his studio in Los Angeles with a clear idea in mind, pinning a poster of L’empire des lumières to the wall. At the time he was writing the album, Browne recalled, “I lived in the house that I’d grown up in and it was that place where every hallway and every view was really carefully thought out, you know, a beautiful picture” (N. Tucker, “Interview with Jackson Browne,” Library of Congress, 24 March 2021; https://www.loc. gov/static/programs/national-recording-preservation-board/documents/ Interview_Jackson-Browne.pdf [accessed 1 October 2024]). Browne suggested they replicate the scene, adding the singer’s own Chevy BelAir to the foreground, a move that transformed Magritte’s timeless subject into an image squarely rooted in the contemporary moment.

The photograph was shot on South Lucerne Avenue in Los Angeles, not far from Browne’s childhood home, and Seidemann recalled the difficulty of capturing the scene at the precise moment when the light balance was just right. In the end, they were unable to find a view of the California sky with a suitable play of clouds that recalled Magritte’s visionary series, and so Seidemann ended up borrowing an image of the New Mexico desert by the photographer David Muench to achieve the effect. When Late For The Sky was released in September 1974, Browne openly acknowledged his debt to Magritte, crediting the cover image “Jackson Brown—if it’s all reet with Magritte.”

AUCTION

Tuesday 19 November 2024 at 7.00pm 20 Rockefeller Plaza New York, NY 10020

EXHIBITION

Saturday 9 November-Tuesday 19 November 2024

Monday-Saturday 10.00am-5.00pm Sunday 1.00pm-5.00pm

AUCTION CODE AND NUMBER

In sending absentee bids or making enquiries, this sale should be referred to as TOPKAPI-23870

ABSENTEE AND TELEPHONE BIDS

Tel: +1 212 636 2437

INQUIRIES

Max Carter Vice Chairman, 20/21 Americas

mcarter@christies.com

+1 212 636 2091

Emma Boyd

Junior Specialist, Impressionist and Modern Art

eboyd@christies.com

+1 212 636 2063

EDITOR

Jennifer Duignam

DESIGN

Kent Albin

PICTURE RESEARCH AND COPYRIGHT COORDINATION

Anne Homans and Sebastien Grimbaum

SPECIAL THANKS

Nicole Arnot

Emma Boyd

Charlie Capstick-Dale

Melanie Davroux

Lee Cohen

Sheri Farber

Vanessa Fusco

Ava Galeva

Vlad Golanov

Imogen Kerr

David Kleiweg de Zwaan

Anita Martignetti

Matthew Masin

Nicholas Michael

Rita Nakouzi

Kelsy O’Shea

Marc Porter

Joseph Quigley

Rusty Riker

Rebecca Roundtree

Stacey Sayer

Sarah Silverstein

Erica Thorpe

Anndrew Vacca

Cara Walsh

FURTHER INFORMATION

This is not a sale catalogue. The sale of this lot is subject to the Conditions of Sale, Important Notices and Explanation of Cataloguing Practice which are set out online. Please see the Conditions of Sale at christies.com for full information about the sale and descriptions of symbols.

“I think as though no one had ever thought before me.” – René Magritte (quoted in S. Whitfield, Magritte, exh. cat., The Hayward Gallery, London, 1992, p. 21).

“This intense personal interest in night and day is a feeling of admiration and astonishment.” – René Magritte (quoted in K. Rooney and E. Plattner, eds., René Magritte: Selected Writings, trans. J. Levy, Richmond, 2016, p. 167).

“Optical illusions [are] the privileged moments that transcend mediocrity. But for that there doesn’t have to be art—it can happen at any moment.” – René Magritte (quoted in in A. Danchev and S. Whitfield, Magritte: A Life, London, 2021, p. 335).

“…night always exists at the same time as day.” – René Magritte (quoted in A. Danchev and S. Whitfield, Magritte: A Life, London, 2021, p. 335).

“The poetic title has nothing to tell us, but must surprise and delight us.” – René Magritte (quoted in X. Canonne and J. Waseige, Magritte: A Lab of Ideas, Works on Paper, exh. cat., Nordiska Akvarellmuseet, Skärhamn, 2022, p. 88).

“After I had painted L’empire des lumières, I got the idea that night and day exist together, that they are one. This is reasonable, or at the very least it’s in keeping with our knowledge: in the world night always exists at the same time as day. (Just as sadness always exists in some people at the same time as happiness in others.) But such ideas are not poetic. What is poetic is the visible image of the picture.” –René Magritte (quoted in S. Whitfield, Magritte, exh. cat., The Hayward Gallery, London, 1992, no. 111).

“My exhibition had enormous publicity and the pavilion was one of the most popular of the Biennale.”

– Peggy Guggenheim

(Out of this Century: Confessions of an Art Addict, London, 1980, p. 329).

“I am showing in Venice, in a room entirely devoted to my work…” – René Magritte (quoted in D. Sylvester, ed., René Magritte: Catalogue Raisonné, Oil Paintings, Objects and Bronzes, 1949-1967, London, 1993, vol. III, p. 54).

“The landscape suggests night and the skyscape day.” – René Magritte (quoted in C. Haskell, ed., René Magritte: The Fifth Season, exh. cat., San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2018, p. 44).

“…each moment is an unforeseeable appearance, each moment demonstrates the absolute mystery of the present.” – René Magritte (quoted in K. Rooney and E. Plattner, René Magritte: Selected Writings, trans. J. Levy, Richmond, 2016, p. 180).

“I have a very limited vocabulary: nothing but ordinary, familiar things. What is “extraordinary” is the connection between them.” –René Magritte (quoted in K. Rooney and E. Plattner, René Magritte: Selected Writings, trans. J. Levy, Richmond, 2016, p. 214).

“What I love about Magritte is he turned the world upside down and inside out in terms of meaning and significance.”

– Paul McCartney

(“Percy Thrillington, Magritte & me,” in The Guardian, 29 Nov 2008, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2008/nov/29/paulmccartney-the-fireman-interview).

“[L’empire des lumières] had a profound effect on me, and I decided to put a figure in it… It’s remained forever the iconic image of The Exorcist.” – William Friedkin (speaking in Leap of Faith (2020), dir. by A.O. Philippe, Shudder Studios, [54.42-55.45]).

Cover and frontispieces illustrate the present work, unless otherwise stated. © 2024 C. Herscovici / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Page 34-35, 58, 97 – Photograph by Nina Slavcheva.

Artwork: © 2024 C. Herscovici / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.