INTRODUCTION

‘I’ve got so much joy out of the art world, and I want to give it back’

Ole Faarup

The home of Ole Faarup was a modern-day Kunstkammer. From room to room, the walls were filled with paintings and the floors piled high with sculptures. This extraordinary, all-encompassing visual environment was a convivial setting for a collector who saw his artworks as a family, and appreciated being in their company every day. Among the most admired in Denmark, Faarup’s exceptional collection remains as testament to the vision and passion of its owner.

While it displays a distinctly Danish sensibility, the story of Faarup’s collection is international. His interest in art was sparked in 1960s New York, where he worked for the Danish design company Georg Jensen. Down the road from his office was the Museum of Modern Art. He began to spend his lunch-breaks among the museum’s masterpieces, and to develop the sharp, intuitive eye that would guide him for years to come.

After his return to Denmark the following decade—where he became director of Illums Bolighus, and later took over furniture retailer 3 Falke Møbler in Frederiksberg—Faarup began to build his collection, with an initial focus on homegrown artists. His first major purchase was Per Kirkeby’s Skovsøen (Lake Forest) (1970), which he kept for the rest of his life. Further highlights among the collection’s Danish names include Ejler Bille, Tal R, Asger Jorn and Sonja Ferlov Mancoba.

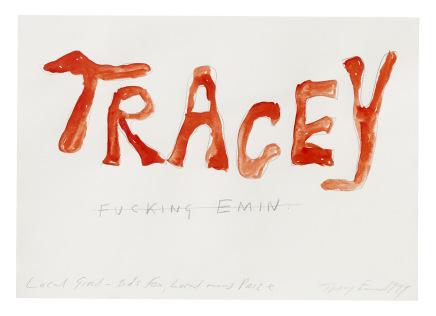

Some other early acquisitions, however, made way for newer art by younger artists. The collection was in constant motion, active and engaged with the present moment. Faarup had a superb sense of intuition and collected many major artists early in their careers. These included many Young British Artists of the 1990s—Damien Hirst, Gary Hume, Grayson Perry, Tracey Emin, Gavin Turk, Sarah Lucas, Noble & Webster—and, during the same decade, the painters Peter Doig and Chris Ofili. Ofili’s Blossom (1997) and Doig’s Country Rock (1997-1998) stand out among their most iconic and celebrated works, and have graced the catalogue covers of major museum exhibitions to which Faarup lent them.

Amid works that hail from many different countries, a grouping of paintings and sculptures from Germany also emerges as a strong vein in the collection. Faarup’s early purchase of a work by Jean-Michel Basquiat—then an artist little-known in Denmark—is yet another example of his forward-looking vision. In more recent years, he acquired works by the up-and-coming Italian artist Guglielmo Castelli, the Cameroonian Pascale Marthine Tayou, and the Polish neo-surrealist Ewa Juszkiewicz. Faarup retained his strong interest in contemporary Danish art, too, forging a close relationship with the rising star Esben Weile Kjær.

Faarup never bought art for the sake of investment, but rather was guided by his own personal emotive responses. He also placed great importance upon meeting the artists whose work he owned, recalling memorable encounters with Doig and Ofili, with Ejler Bille, and with Warhol at Max’s Kansas City in New York. Something of an artist’s soul, he believed, resided in their work. Indeed, it is the capacity to convey another human view of the world—whether it thrills and quickens the pulse, or offers an escape from the noise of day-to-day life—that gives art its power, beauty and integrity.

Living among these artworks as his intimate companions, it is little wonder that Faarup regarded his collection with such warmth. With his legacy, he set out to create a fund through which museums can acquire new works by young Danish artists. The Ole Faarup Art Foundation will share his joy with others, and leave his country’s artistic lifeblood all the stronger. While his collection represents more than half a century of deeply-felt passion for art, Ole Faarup always had an intelligent eye fixed firmly on the future.

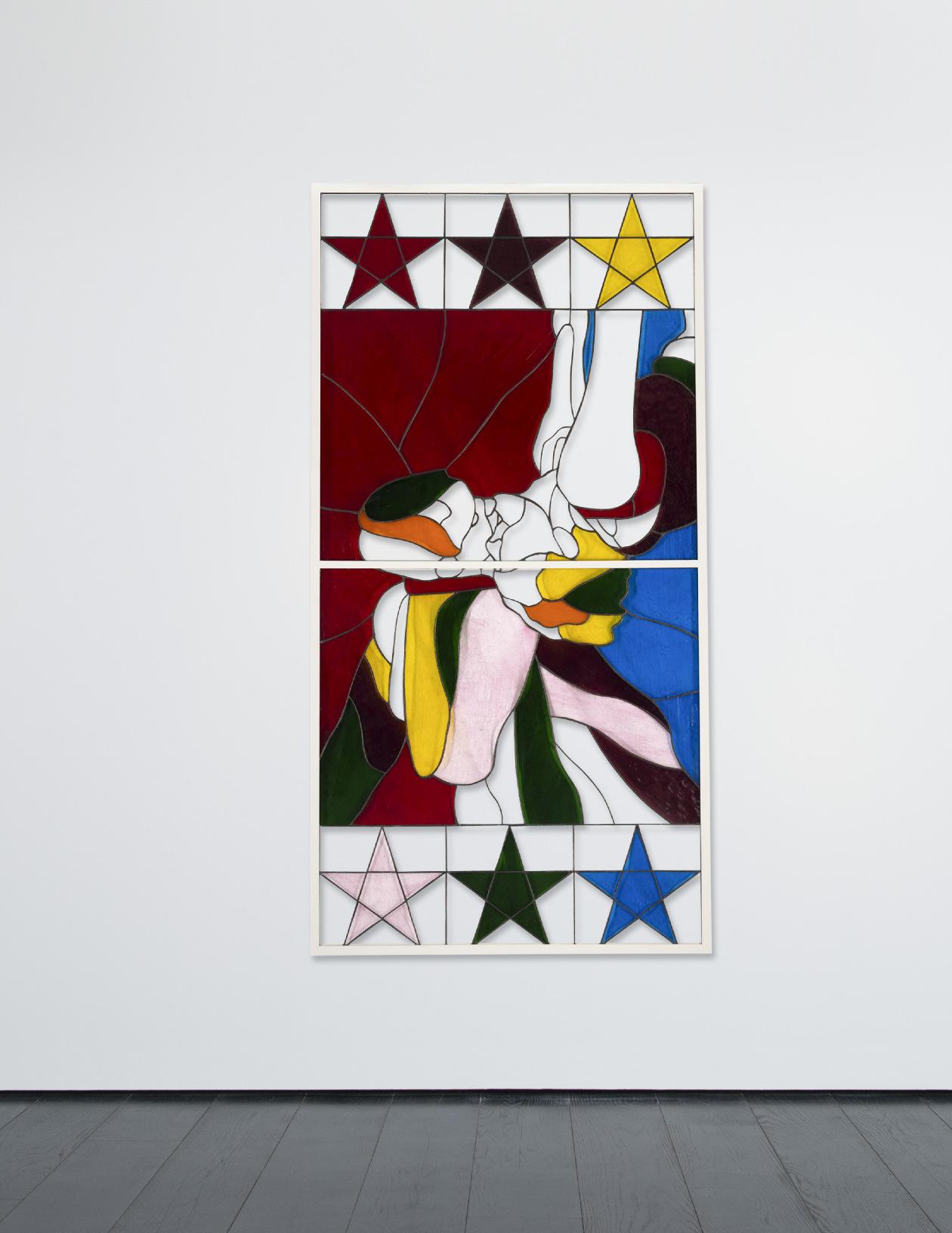

ESBEN WEILE KJÆR (B. 1992)

Aske and Johan upside down kissing in Power Play at Kunstforeningen GL STRAND

stained glass, in artist’s frame

65 x 33¡in. (165.1 x 84.8cm.)

Executed in 2020

£15,000-20,000

PROVENANCE:

Andersen's Contemporary, Copenhagen. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 2020.

Esben Weile Kjær and Ole Faarup in front of the present lot.

Photograph by Lene Renner.

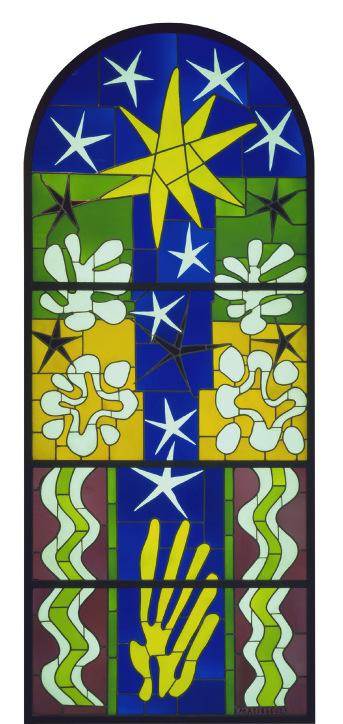

HENRI MATISSE

Nuit de Noel. Paris, 1952

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital image: © 2025 The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence.

Aske and Johan upside down kissing in Power Play at Kunstforeningen GL STRAND (2020) is a mesmeric stainedglass work by the celebrated Danish artist Esben Weile Kjær. With a practice spanning music, performance, installation and fine art, Kjær’s work is guided by a reciprocity between art forms. Many of his stained-glass pieces are based on photographs of his own performance works. From his studio in Copenhagen the artist preserves ephemeral moments of movement and connection with the aid of a lightbox, transforming photographic prints into clean graphic lines and transcendent planes of colour. The present work captures and extends a fleeting second of Kjær’s Power Play, a performance-based exhibition held at the Kunstforeningen GL STRAND in 2020. Kjær, who graduated from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 2022, has risen to huge critical acclaim in recent years. His works are held in museum collections across Scandinavia. Kjær’s first solo museum exhibition opened at the Kunsten Museum of Modern Art, Aalborg last year, and will be followed in 2025 by further shows at the Salzburg Kunstverein and Rudolph Tegners Museum, Dronningmølle.

Installed personally by the artist in the window of Ole Faarup’s home in Frederiksberg, the present work’s glass tableau is shaped and reshaped by light. The scene becomes passionate and euphoric when saturated by blazing sun, and softly intimate as the light fades. Working in stained glass offers Kjær a conscious engagement with European art history. For him the medium marks places of togetherness across time,

‘I want the art to go into real life’

Esben Weile Kjær

and he looks to the sublime windows of soaring Gothic churches or the brilliant stained-glass domes of Parisian casinos as a precedent for his contemporary iconography of dance and performance. An echo is also felt in these works of Olafur Eliasson’s Your rainbow panorama (2006-2011), the sweeping, kaleidoscopic glass installation which crowns the ARoS art museum in Kjær’s native city of Aarhus.

At the same time, Kjær works within a distinctly Pop idiom. He draws on titans of the movement from Andy Warhol to Jeff Koons, creating work that replicates the clean lines and glossy veneers of consumer culture and mass media. There is an archival element to his practice, a preservation of the fleeting ‘now’ which churns ceaselessly on amid contemporary society’s relentless torrent of visual information. His work is concerned with selfhood in this new age, exploring how the individual is shaped by and against popular culture and technological advancement. The artist’s stained-glass works become a mirror of our time, articulated through the nostalgia of traditional media. Aske and Johan upside down kissing in Power Play at Kunstforeningen GL STRAND questions the possibility of the individual or private moment, hovering between the intimacy of the stained-glass image and the public spectacle which formed its basis. Kjær’s practice is fuelled by these intricacies and ambiguities of human connection, and by a powerful sense of nostalgia, conjured from the push and pull between private and shared memory.

PETER DOIG (B. 1959)

Ski Jacket

signed twice, inscribed and dated 'PETER DOIG 1994 London Peter Doig' (on the reverse) oil on canvas

71√ x 83√in. (182.5 x 213cm.)

Painted in 1994

£6,000,000-8,000,000

PROVENANCE: Gavin Brown's Enterprise, New York. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 1994.

EXHIBITED:

Aalborg, Kunsten Museum of Modern Art, Wonders - Masterpieces from Private Collections in Denmark, 2012, p. 170, no. 2 (incorrectly titled 'Ski Jacked [sic]'; illustrated in colour, pp. 76-77).

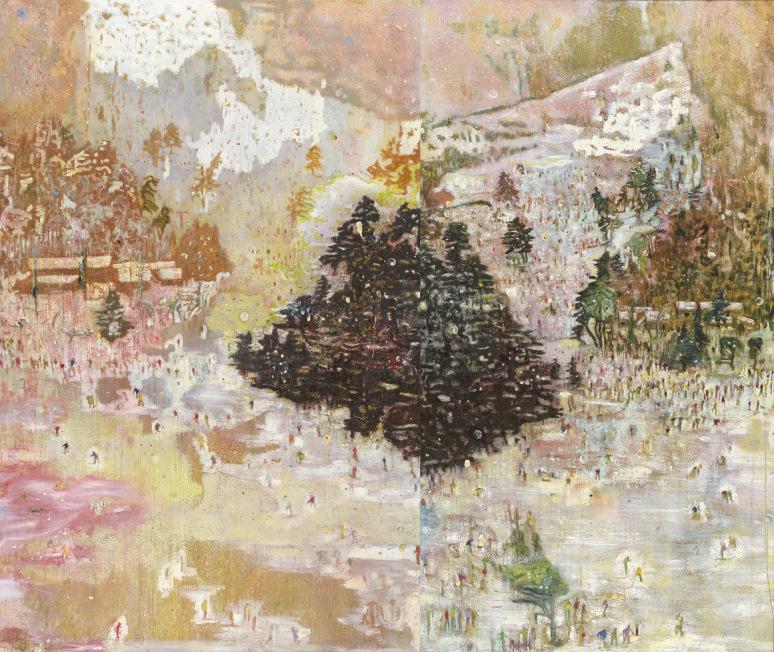

PETER DOIG

Ski Jacket, 1994 Tate, London. Artwork: © Peter Doig. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025. Digital image: © Tate.

Aluminous vision of memory, place and the shifting splendour of paint, Ski Jacket is a majestic work from a pivotal moment in Peter Doig’s career. It was made in 1994, the year of Doig’s Turner Prize nomination: its sister painting, also titled Ski Jacket, was included in the prize exhibition and acquired by the Tate, London in 1995. More than two metres across, the work depicts a ski slope flushed in glowing, auroral hues of pink, gold and blue. Tiny skiers are peppered among conifers and chalet buildings, bringing together the cabins and trees that are among Doig’s most iconic motifs. Snow veils the scene in a dazzling diversity of texture: paint becomes a mist of white powder, a spray of droplets, a glaze of frost, or impasto dots that wink like sequins. This richly layered snowscape dramatises the hazy sensations of remembering, and— through skiing—the slippery, thrilling pursuit of painting itself.

Acquired by Ole Faarup soon after its completion, Ski Jacket has been unseen in public since 2012, when it was shown at Kunsten Museum of Modern Art Aalborg.

Doig’s Turner Prize nomination followed several years of mounting critical acclaim. After graduating from the Chelsea School of Art in 1990, he had been honoured with a major solo exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, London in 1991, and in 1993 he won the John Moores Painting Prize for Blotter (1993, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool). The period saw him paint some of his most beguiling canvases. In wintry, enigmatic works such as Blotter, Charley’s

Space (1991) and Pond Life (1993), as well as the present painting, he used screens of snow to partially veil his images, visualising the fugitive qualities of memory. Many dealt with themes or motifs drawn from Doig’s time in Canada, where he had spent much of his youth. They were sparked by photographs, placing his experience at a further remove. While winter sports had personal significance for Doig—he remains a keen ice-hockey player—Ski Jacket began with a typically indirect source: it is based on a photograph of a Japanese ski slope that his father found in a Toronto newspaper.

The photograph, Doig said, reminded him of ‘Japanese landscape painting, the scroll-like form, with all activities coming down’ (P. Doig quoted in M. Matsui, ‘I Am Never Bored with Painting: Peter Doig, Interview’, Bijutsu Techo, vol. 72, no. 1082, June 2020, p. 186).

Like the figures in those paintings, Ski Jacket’s tiny skiers beckon the viewer into the landscape as they dart, glide and crowd among the sprawling trees and snowbound cabins. While Doig had long been interested in tensions between human presence and natural phenomena, he had at this stage made relatively few works that featured people. The dozens depicted here—some of them fully legible, others little more than distant flicks of colour—introduce a previously unseen sense of scale and activity. The psychedelic palette heightens the drama, with blooming mauve and lilac contrasting with cooler blues and pools of golden light.

CLAUDE MONET

Haystacks (Effect of Snow and Sun), 1891

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Digital image: © 2025 The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

‘… I was looking a lot at Monet, where there is this incredibly extreme, apparently exaggerated use of colour’

Peter Doig

PETER DOIG

Blotter, 1993

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

Artwork: © Peter Doig. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025. Digital image: © Peter Doig. All Rights Reserved, DACS Images.

GERHARD RICHTER

Eis (2), 1989

The Art Institute of Chicago. © Gerhard Richter 2025 (0080).

‘… snow somehow has this effect of drawing you inwards’

Peter Doig

‘When I was making the “snow” paintings’, Doig explained, ‘I was looking a lot at Monet, where there is this incredibly extreme, apparently exaggerated use of colour.’ These art-historical cues were refracted through first-hand sensory memories. He drew upon ‘the way that you perceive things when you are in the mountains— for example, when you are feeling warm in an otherwise cold environment, and how the light is often extreme and accentuated by wearing different coloured goggles … There used to be these rose-tinted goggles that made everything look as pink as cotton candy’ (P. Doig quoted in ‘Peter Doig: Twenty Questions (extract)’, in A. Searle et al. (eds.), Peter Doig, London 2007, pp. 132, 140). Doig’s ‘rose-tinted goggles’ evoke both an actual visual experience and the transformative lens of retrospection.

While snow was a distinctive element of Doig’s Canadian imaginary, it was also a device with which to picture the white-outs, interruptions and accretions inherent to the act of remembering. He has spoken admiringly of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow (1563), where ‘the snow is almost all the same size, it’s not perspectival, it’s this notion of the “idea” of snow, which I like. It becomes like a screen, making you look through it’ (P. Doig quoted in L. Edelstein, ‘Peter Doig: Losing Oneself in the Looking’, in Flash Art, Vol. 31, May-June 1998, p. 86). An artist fascinated by moving images, Doig also saw parallels between Bruegel’s work and the ‘snow’ that can beset television screens with poor signal. Gerhard Richter’s squeegeed abstracts and blurred photo-paintings present similar disturbances. Ski Jacket, derived from a found photograph of a distant country, overlays myriad forms of interference and mediation.

PIETER BRUEGEL THE ELDER

The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow, 1563 Sammlung Oskar Reinhart Am Römerholz, Winterthur.

‘… I am using these natural phenomena and amplifying them through the materiality of paint and the activity of painting’

Peter Doig

JOAN MITCHELL

Grandes Carrières, 1961-1962

The Museum of Modern Art, New York..

Artwork: © Estate of Joan Mitchell. Digital image: © 2025 The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence.

Doig emerged in London at a time when painting was out of fashion. Many of his contemporaries, who became known as the Young British Artists, were engaged with conceptualism, privileging the use of sculpture, installation and found objects. In Ski Jacket, the skiers captured something of his resolve to be a painter. The people in the picture, he noticed, were all beginners, trying to stay on their feet: ‘when you start skiing you slip all over the place, yet over a period of time you learn to cope … I think painting is a bit like that. It takes time to actually take control of the greasy stuff, paint’ (P. Doig quoted in A. Searle et al. (eds.), ibid., p. 140). Like a skier, Doig’s own technical brilliance emerges against the intrinsic instability of his medium. Ski Jacket shimmers between abstract and figurative registers, alive with endless change. Variously embodying human figures, impacted ice, fresh powder or blizzard, the pigment also lays bare its material presence as paint on a flat plane.

This alchemy is at the heart of why Doig paints. Like snow and like memory, oil paint transforms, changes state; it can be opaque, misty, frozen in place or fluid and melting. In later years the artist would privilege more spare compositions, concerned with not making a mannerism of the ‘screen’ effects that had defined his seminal works. In Ski Jacket, however, an unburdened exuberance is on full display. The painting is bejewelled with colour and texture, ornate with metaphorical and physical layers. If memories always lie just beyond reach, painting, in Doig’s hands, creates a new reality to hold on to. As he drifts among the places and images of his past, he becomes the orchestrator of another world. ‘Painting is about working your way across the surface, getting lost in it’, he has said. ‘Sometimes I think—shall I have a bit more weather over here? A snowstorm?’ (P. Doig in conversation with A. Searle, in Peter Doig: Blotter, exh. cat. Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin 1995, p. 10).

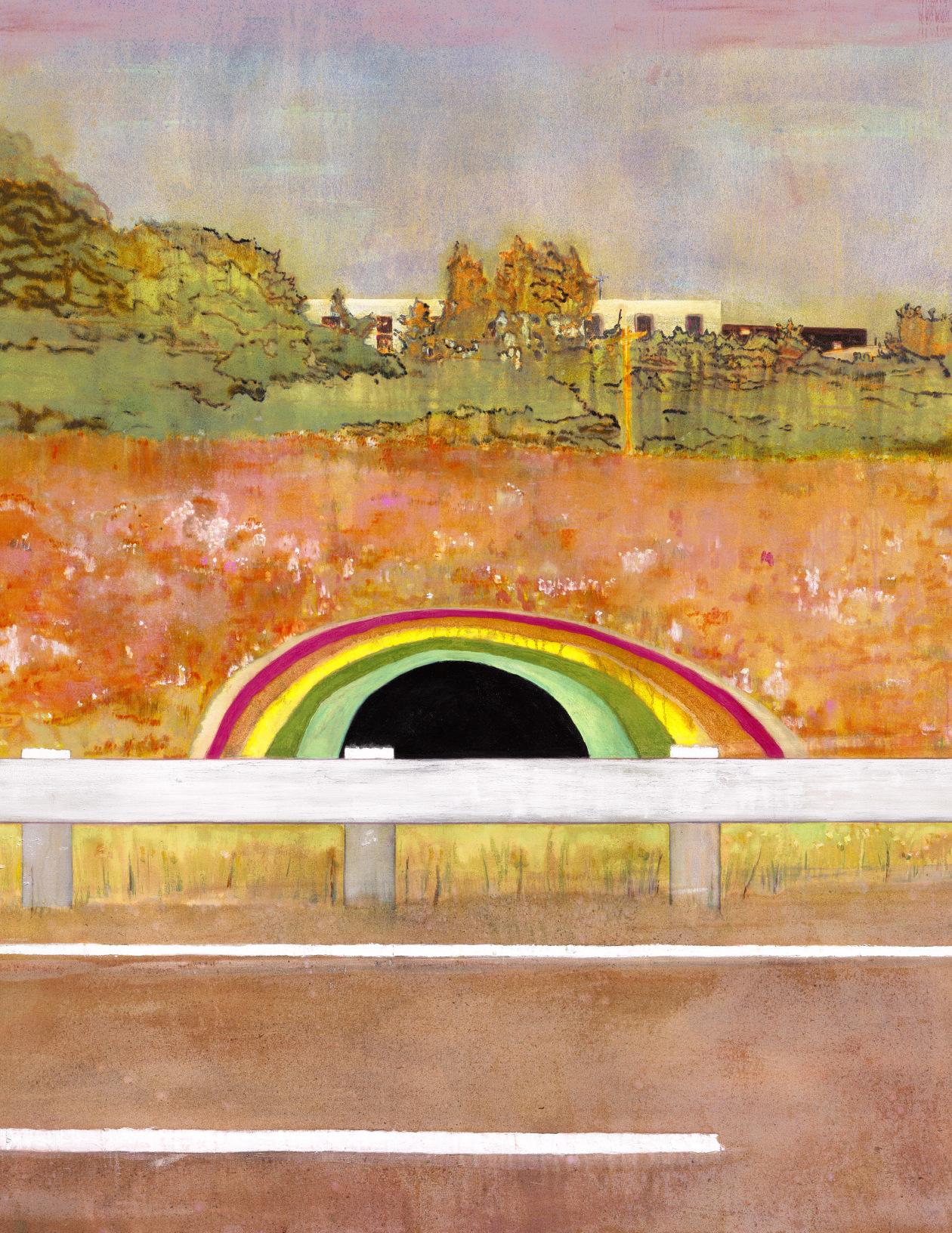

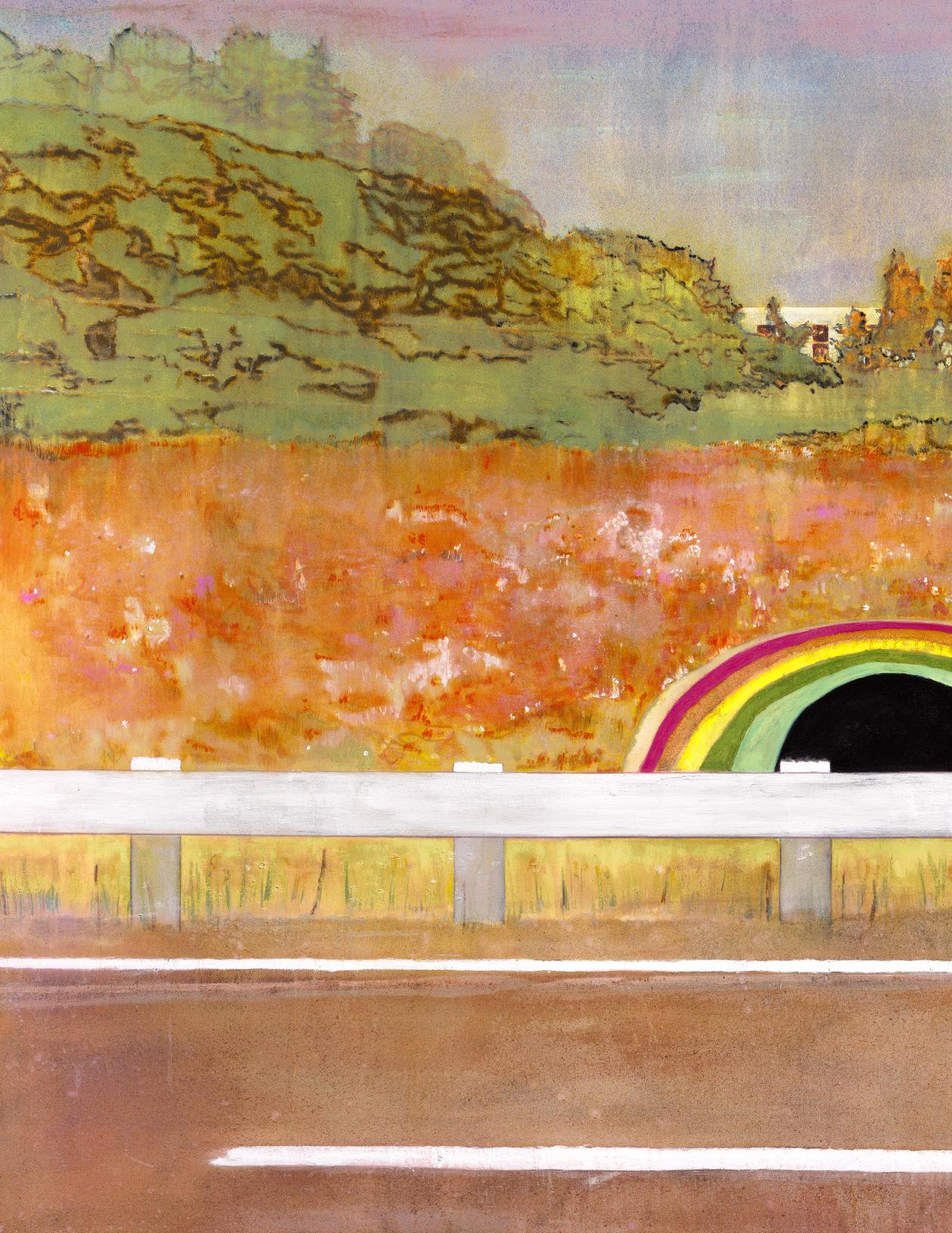

PETER DOIG (B. 1959)

Country Rock

signed twice, titled and dated 'Peter Doig. "country-rock" '98-'99 PETER DOIG' (on the overlap) oil on canvas

78æ x 118¿in. (200 x 300cm.)

Painted in 1998-1999

£7,000,000-10,000,000

PROVENANCE: Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 1999.

EXHIBITED:

Berlin, Contemporary Fine Arts, Peter Doig "country-rock", 1999. Glarus, Kunsthaus Glarus, Peter Doig - version, 1999, p. 47 (illustrated in colour, p. 39).

Dublin, The Douglas Hyde Gallery, Almost Grown: Paintings by Peter Doig, 2000, p. 29 (with incorrect dimensions; illustrated in colour, p. 13).

Eindhoven, Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Twisted, Urban and Visionary Landscapes in Contemporary Painting, 2000, p. 68 (illustrated in colour, p. 18). London, Victoria Miro Gallery, Peter Doig: 100 Years Ago, 2002.

London, Tate Britain, Peter Doig, 2008-2009, p. 156 (detail illustrated in colour on the front and back covers; illustrated in colour, pp. 84-85; and detail illustrated in colour on the exhibition poster). This exhibition later travelled to Paris, ARC/Musée d'Art moderne de la Ville de Paris and Frankfurt, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt.

Humlebæk, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Peter Doig, 2015, p. 94 (illustrated in colour, pp. 48-49).

LITERATURE: Peter Doig: Charley's Space, exh. cat., Maastricht, Bonnefantenmuseum, 2003, p. 137 (illustrated in colour, p. 105).

A. Searle, K. Scott and C. Grenier (eds.), Peter Doig, London 2007, p. 158 (illustrated in colour, pp. 136-137).

C. Lampert and R. Shiff, Peter Doig, New York 2011, pp. 236 & 353 (illustrated in colour, p. 237).

Peter Doig with the present lot at his exhibition Peter Doig “country-rock”, Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin, 1999.

Photo: © Andrea Stappert.

‘I am trying to create something that is questionable, something that is difficult, if not impossible, to put into words’

Peter Doig

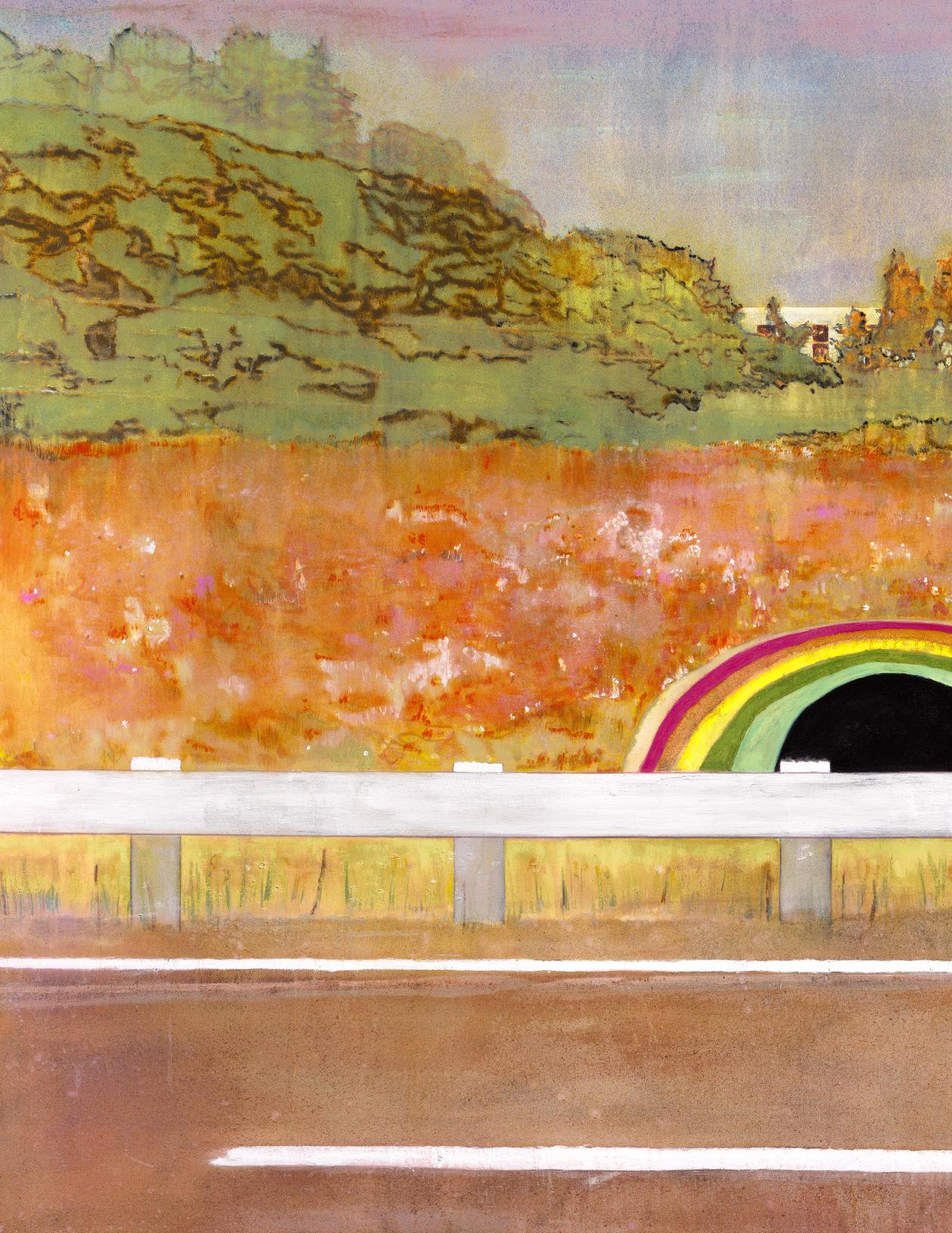

Country Rock (1998-1999) is a sumptuous, dreamlike painting that stands among Peter Doig’s most iconic works. Three metres across and two metres high, it is the largest of three monumental canvases he made on the subject of a roadside rainbow—in fact the painted mouth of a tunnel in Toronto, Canada— during the late 1990s. The rainbow gazes like an eye over the white line of a traffic barrier. It is set in a bank of rosy undergrowth that simmers and glows, rising to a horizon of dark, spectral green trees beneath a lavender sky. The painting comes alive in a rich diversity of tones and textures, charged with the elusive sense of place, memory and reverie that defines Doig’s practice. Acquired by Ole Faarup the year it was made, Country Rock has been included in a plethora of major solo exhibitions since, appearing in Glarus, Dublin, Maastricht, Nîmes, Paris, Frankfurt and London, where—in 2008—it starred as the catalogue cover for Doig’s acclaimed midcareer retrospective at Tate Britain. The painting was most recently seen in 2015 as part of his large-scale survey at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk.

The enigmatic, dislocated quality of Doig’s work has its roots in a life lived on the move. Born in Scotland in 1959, he spent some of his childhood in Trinidad before moving to Canada. Aged twenty he came to London to study art at Wimbledon and then Saint Martin’s, returning at thirty—after another stint in Canada—to complete his MA at the Chelsea School of Art. The 1990s were marked by a swift rise to fame, including a breakout show at the Whitechapel Gallery (1991), his receipt of the John Moores Painting Prize (1993) and a Turner Prize nomination (1994). Living in London during these years, he embarked on something of a ‘Canadian period’ as he sought to come to terms with the country’s formative role in his youth. Distance is important in Doig’s work: he once tried to paint a landscape en plein air in Canada and found it impossible. His paintings instead take shape through second-hand images—found photographs, or his own—that fuel his imagination.

Detail of the present lot reproduced on the poster for Peter Doig at Tate Britain, 2008.

Digital image: © Tate. Photo: Jochen Littkemann.

The rainbow, which can be seen to the east of the Don Valley Parkway, is a beloved Toronto landmark. Doig was drawn to its bittersweet aura. ‘A lot of the paintings portray a sense of optimism that can often be read as being a little desperate,’ he has said, ‘like the image of a rainbow painted around the entrance to an underpass’ (P. Doig quoted in ‘Peter Doig: Twenty Questions (extract)’, in A. Searle et al. (eds.), Peter Doig, London 2007, p. 139). A local teenager, Berg Johnson, painted the mural in 1972 in memory of a friend who had lost her life in a road accident. He maintained his artwork for two decades in a back-and-forth with local authorities, who continually painted it over in grey, until he was ordered to desist. Officially restored in 2012, it still brightens the journeys of commuters today, who call the road the ‘Don Valley Parking Lot’ for its tedious traffic. Doig took his own drive-by photos of the site, refining Country Rock’s composition across multiple watercolours, oil sketches and etching and aquatint editions.

Invoking this motif under the evocative title of ‘country rock’—the type of music one might hear on one’s car radio in Canada—Doig draws upon personal memories of a particular place. Without knowledge of these specifics, however, the painting still casts its spell. ‘My experience is just the spark’, he has explained, ‘… which makes me think about things that are a part of other people’s experience’ (P. Doig quoted in P. Bonaventura, ‘Peter Doig: A Hunter in the Snow’, Artefactum, vol. XI, no. 53, Autumn 1994, p. 12). The road, a zone of transit from one place to another, has a liminal quality in common with the rainbow. Both propose routes to elsewhere. For Adrian Searle, this territory was more psychedelic than country rock. ‘Road-markings are already a kind of abstraction, and so is the entrance to the subway. It is a black hole … a break in reality, like Alice’s rabbit hole. I can almost hear Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit” wafting over from that building’ (A. Searle, ‘Wide blue yonder’, The Guardian, 16 April 2002).

The present lot exhibited in Peter Doig, Tate Britain, 2008.

Photo: © Tate.

Artwork: © Peter Doig, DACS 2025.

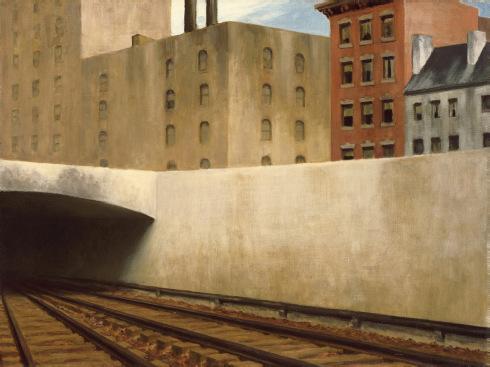

EDWARD HOPPER

Approaching a City, 1946

The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Artwork: © Edward Hopper, DACS 2025. Digital image: Album/Scala, Florence.

PETER DOIG

The House that Jacques Built, 1991 Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv.

Artwork: © Peter Doig, DACS 2025.

‘I’m interested in mediated, almost clichéd notions of a pastoral landscape’

Peter Doig

The picture’s enchanted, in-between atmosphere is heightened by Doig’s contrasting painterly techniques. The road-markings and traffic barrier are stark horizontals, their white pigment cutting through the shimmering, diaphanous treatment of foliage and sky. The tunnel itself is an opaque black. Such tensions between manmade structure and organic form animate much of Doig’s work: his ‘Concrete Cabins’ series, begun in the early 1990s, played Le Corbusier’s geometric Modernist architecture at Briey-en-Forêt against the unruly growth of the encroaching woodland. Doig expresses an awe at nature that is Romantic at heart—Country Rock’s golden telegraph pole even evokes Caspar David Friedrich, who placed reverential crucifixes in his landscapes—and tempered by the melancholy of a world where rainbows are painted on concrete.

Art-historical echoes abound in Country Rock. One image Doig had in mind was Edward Hopper’s 1946 painting Approaching a City, whose dark railway tunnel—another peripheral place—is a void of urban anonymity. His palette conjures the saturated colours of German Expressionism and Edvard Munch. The bold tripartite composition, meanwhile, relates to the abstract ‘zip’ paintings of Barnett Newman. In his early painting The House that Jacques Built (1991, Tel Aviv Museum of Art), Doig had drawn consciously upon Newman’s ‘zip’ effect in order to create three strips of contrasting visual texture, enacting an interplay between nature and human presence. He would employ similar three-way divisions in major works such as Daytime Astronomy (1998-1999), Echo Lake (1998, Tate, London), Country Rock and, later, 100 Years Ago (2000).

Andreas Gursky’s iconic photograph Rhein II (1999), which depicts the Rhine River in Newman-like bands of grey and green, presents a comparable view of the post-industrial sublime.

PETER DOIG

100 Years Ago, 2000

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

Artwork: © Peter Doig, DACS 2025.

‘Painting is … a hopelessly romantic thing to do’

Peter Doig

NEWMAN

Horizon Light, 1949

Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery and Sculpture Garden, University of Nebraska.

Artwork: © 2025 The Barnett Newman Foundation, New York / DACS, London.

Where his paintings of the early 1990s had involved dense build-ups of pigment, often creating ‘screens’ of depicted snow or foliage, towards the decade’s end Doig began a transition to more open and translucent surfaces. ‘I always try to escape my mannerisms’, he has said. ‘… I am always trying to find a way of making something less complicated, more fluent, more fluid’ (P. Doig in conversation with K. Scott, in Peter Doig, ibid., p. 20). This shift is visible in Country Rock, whose lush chromatic veils attain a watercolour-like delicacy. The rainbow runs with a spectrum of fine drips, and soft white splashes bloom on the tarmac. The scrubland sparkles with luminous, blushing hues below the velvet-dark trees, which appear ghostly—almost as if in photographic negative—against the lilacwashed sky. The scene wavers before our eyes like a mirage on the verge of dissolution.

It is this ambiguity—revelling at once in the splendid, mutable actuality of paint and the illusory nature of the image created—that lends Doig’s works their unique magic and mystery. His painting of a painted rainbow points to the mediated nature of postmodern experience, but it also suggests a hopeful entry into another realm, somewhere beyond the surface of the picture. ‘Like ghost stories,’ wrote Peter Campbell of the works in Doig’s 2008 Tate exhibition, ‘they draw on the potency of matters unresolved; it hangs about them like an unearthed static charge’ (P. Campbell, ‘Peter Doig’, The London Review of Books, vol. 30, no. 5, 6 March 2008).

Flickering between past, present, fact, fantasy and personal and collective memory, Country Rock is a wistful vision of painting as possibility: as a way of looking at the world we live in, and a place of imaginative escape.

BARNETT

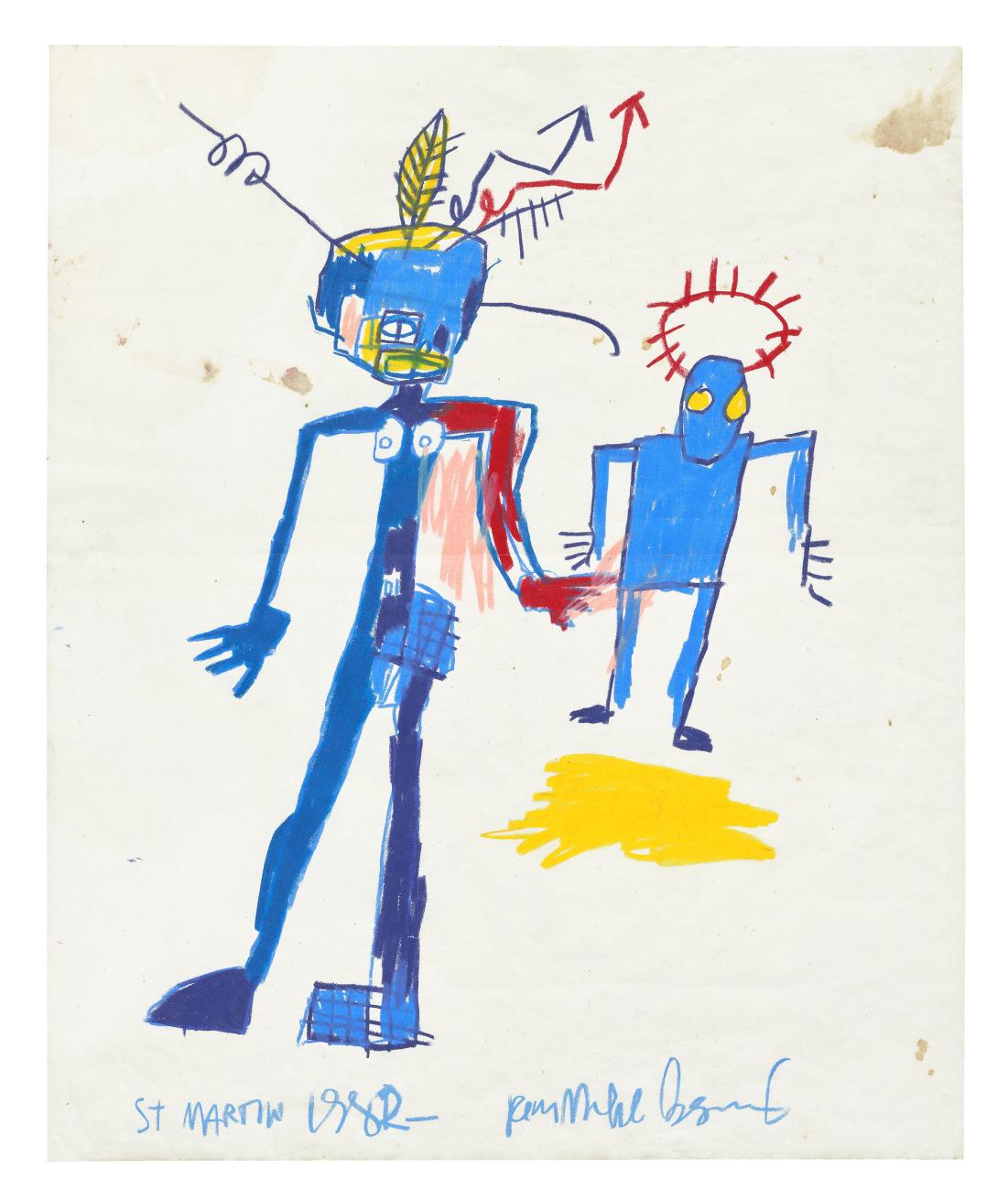

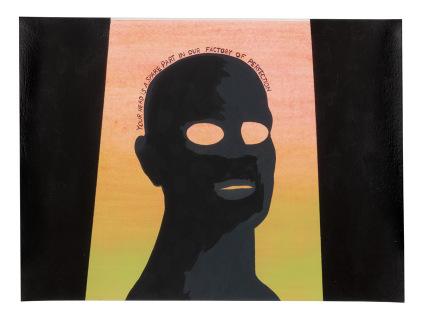

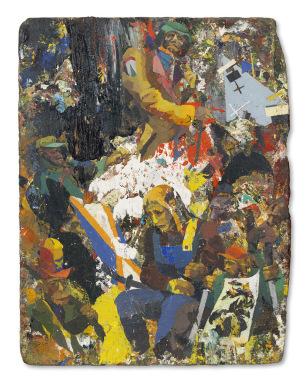

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT (1960-1988)

Untitled

signed, inscribed and dated 'ST MARTIN 1982- Jean-Michel Basquiat' (lower edge) oilstick on paper

17 x 13√in. (43 x 35.3cm.)

Executed in 1982

£300,000-500,000

PROVENANCE:

Private Collection (acquired directly from the artist).

Anon. sale, Sotheby's New York, 5 October 1989, lot 321. Galerie Fabien Boulakia, Paris. Knud Thorbjørnsen Collection, Copenhagen (acquired from the above in 1990).

Anon. sale, Kunsthallen Kunstauktioner Copenhagen, 8 March 1995, lot 11.

Acquired at the above sale by Ole Faarup.

EXHIBITED: Paris, Galerie Fabien Boulakia, Basquiat, 1990 (illustrated in colour, p. 24).

‘His hand was swift and sure. The images that trailed behind it crackled and exploded like fireworks shot from the back of a speeding flatbed truck’

Robert Storr

Two totemic figures dominate the picture plane in this vibrant, emblematic work by Jean-Michel Basquiat, executed in a striking primary palette in the artist’s trademark oilstick medium. A larger, female figure is described with an almost Cubist arrangement of form: simultaneously depicted frontally and in profile, she wears an elaborate headpiece crowned with a single, bright yellow feather. The second figure is angular and robot-like. Adorned with a bright red nimbus of thorns, its large yellow eyes gleam like beacons. Along the lower edge the sheet is signed and inscribed in Basquiat’s unmistakable graphic scrawl. It was only recently that Basquiat—known initially as the enigmatic street artist SAMO—had taken to signing works with his real name. The present work was executed in 1982, the exhilarating and pivotal year that saw him rise to stardom. His debut solo show at the Annina Nosei Gallery in New York in March precipitated a string of international solo exhibitions across the year, and that summer he was the youngest artist to be included in curator Rudi Fuchs’s documenta VII.

Basquiat worked amid a ferment of life and art, and his studio brimmed with drawings, paintings, and source material. From this profusion of inspiration, quickfire images poured fully formed from his mind. Drawing—on paper or canvas—formed the basis of his practice, typically with oilstick. The medium’s slick, tacky sheen suited his bold visual lexicon. ‘His graphic ferocity’, suggests Peter Schjeldahl, ‘was tensile and plangent’ (P. Schjeldahl, ‘JeanMichel Basquiat’, in Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light: 100 Art Writings 1988-2018, New York, 2019, p. 39). There is an immediacy and intimacy to Basquiat’s works on paper, which frequently preserve the traces—coffee stains, footprints—of his daily life: ‘scarred, torn and trampled, much of his work on paper bears the direct imprint of his urgency’ (R. Storr, ‘Two Hundred Beats Per Minute’ in Basquiat Drawings, exh. cat. Robert Miller Gallery, New York 1990, n.p.).

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT

Untitled, 1982

Private collection.

Artwork: © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Licensed by Artestar, New York.

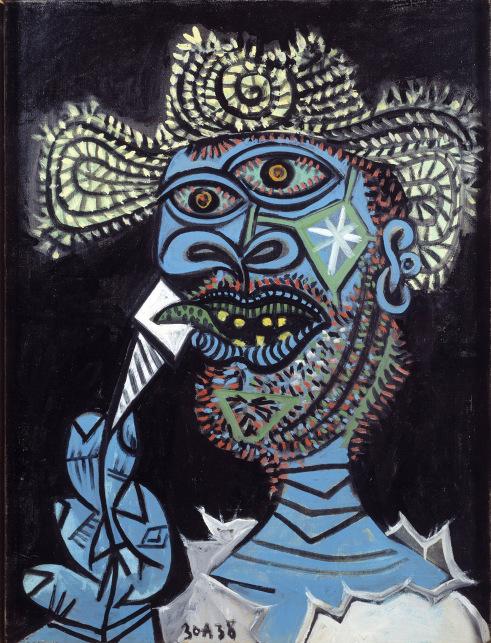

Homme au chapeau de paille et au cornet de glace, 1938

Musée Picasso, Paris.

Artwork: © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2025.

Digital image: © Photo Josse / © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2025 / BridgemanImages.

Basquiat lifted ideas from art history, popular culture and religious iconography. He pored over the collection catalogues of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the British Museum, as well as books such as Burchard Brentjes’ African Rock Art (1969), often translating their idols and statuettes into his drawings. His oeuvre is replete with heroic imagery of crowns, halos, and masks, populated by archetypal images of royalty, athletes, warriors, and robots. Both figures in the present work are crowned in some way. One wears an elaborate plumed headpiece that crackles with electric lines, flying arrows, and antennae-like forms, like an exploding feathered war bonnet. For Basquiat crowns were ambiguous, even mocking: an allusion to the Western obsession with being on top, and the ease with which contemporary life could become a game of snakes and ladders. The brilliant red crown of thorns which adorns the second figure is a trademark motif in his work, emblematic of the weight of glory.

PABLO PICASSO

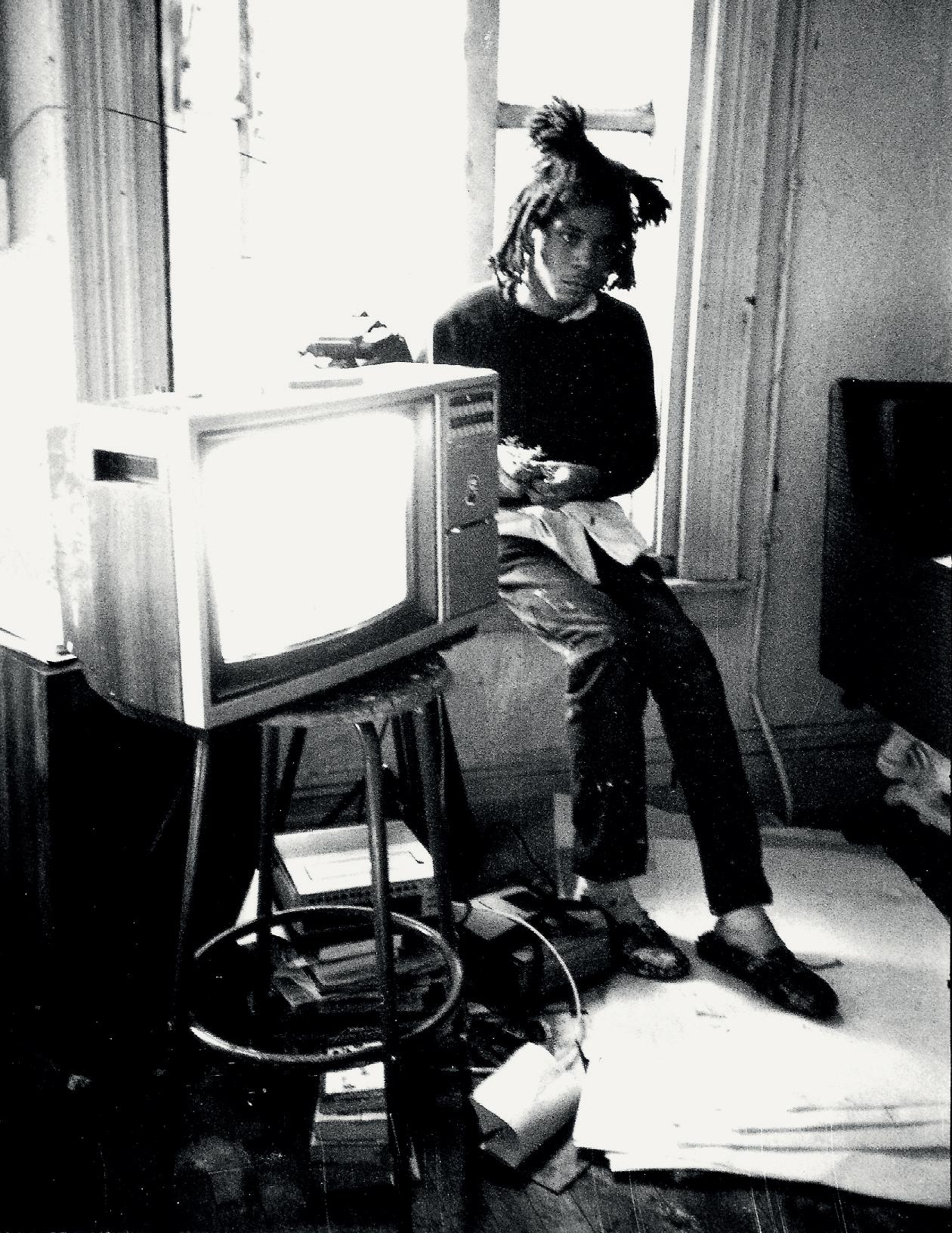

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, NEW YORK, 1983.

Photographed by Roland Hagenberg.

PIERO DELLA FRANCESCA

Madonna del Parto, circa 1450-1470

Musei Civici Madonna del Parto, Monterchi.

Digital image: © 2025 Photo Scala, Florence.

Basquiat was of Haitian and Puerto-Rican descent, and the present work—inscribed ‘ST MARTIN’—may be a tribute to the island of Saint Martin in the northeastern Caribbean Sea. Another inspiration may have been Saint Martin de Porres, the patron saint of social justice, racial harmony and mixed-race people. Born illegitimately in 1579 to a Spanish aristocrat and freed black slave, Saint Martin struggled to be accepted into a religious order in his home city of Lima. Persevering, he volunteered within a Dominican monastery and eventually became one of the few mixed-race Dominican brothers of the time, widely respected for his devotion and compassion. Canonised in 1962, two decades before the present work was executed, his life and work would have resonated with Basquiat, who was keenly aware of the complexities of colonial history and similarly concerned with the plight of social justice. Through works such as the present, Basquiat constructed a bold new visual realm in which to counter the inequalities and hypocrisies built into the fabric of twentieth-century America.

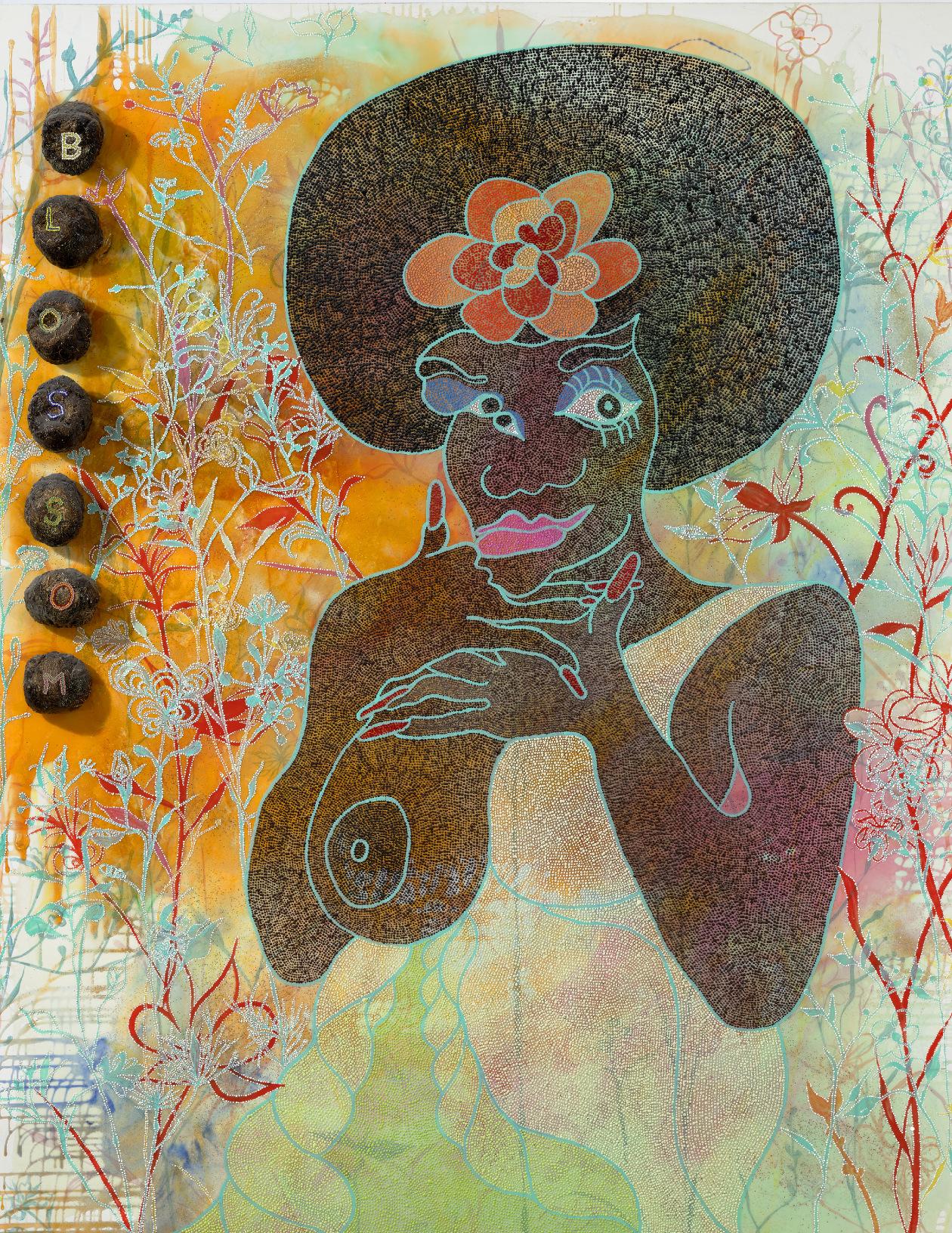

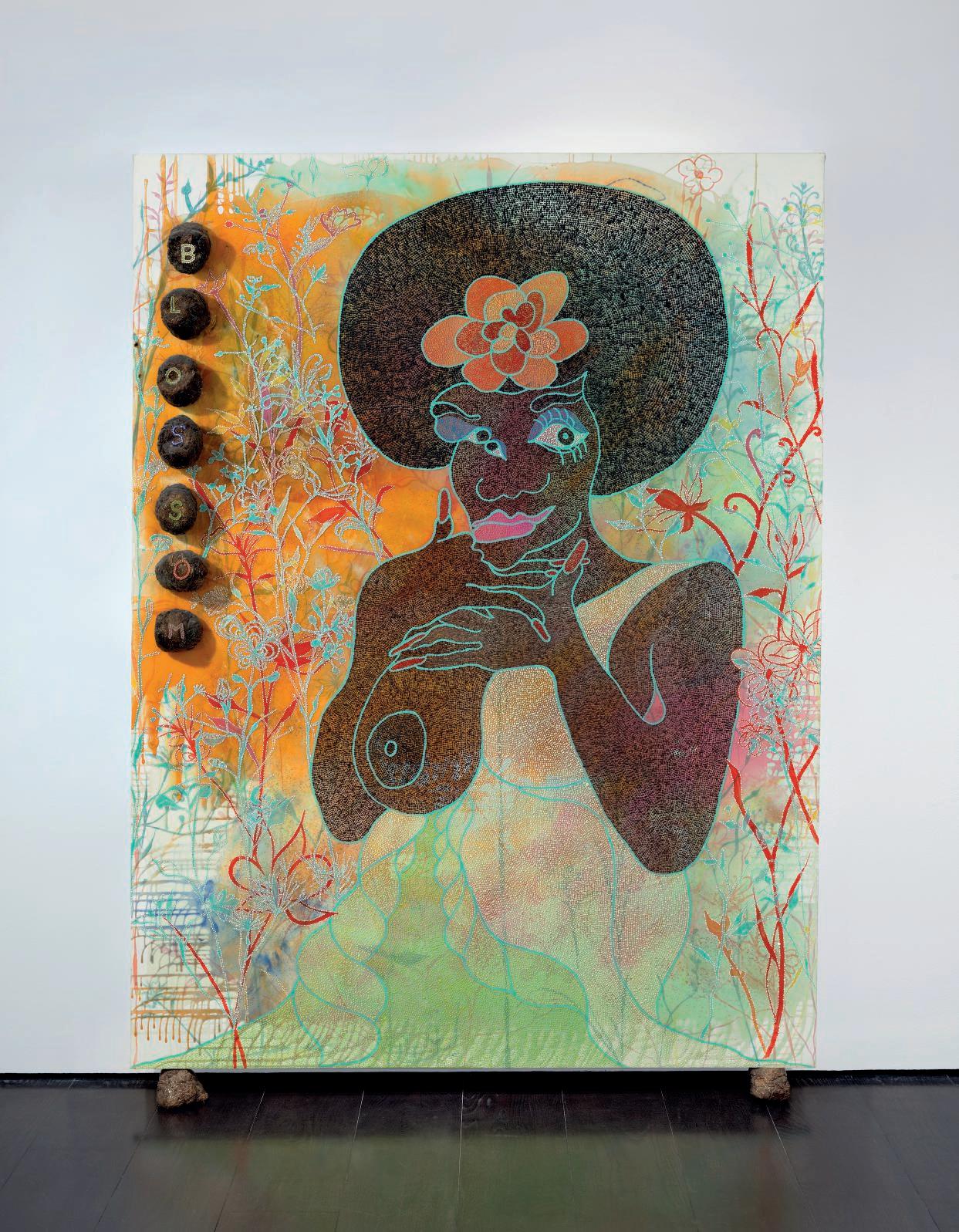

CHRIS OFILI (B. 1968)

Blossom

signed, signed with artist's initials, titled and dated '"Blossom" 1997 Chris Ofili CO' (on the stretcher)

oil, acrylic, polyester resin, glitter, pins and elephant dung on linen

99Ω x 72in. (252.5 x 183cm.)

Executed in 1997

£1,000,000-1,500,000

PROVENANCE:

Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 1997.

EXHIBITED:

Berlin, Contemporary Fine Arts, Pimpin' ain't easy, but it sure is fun, 1997. Southhampton, Southhampton City Art Gallery, Chris Ofili, 1998-1999, pp. 9-10 and 70, no. 26 (illustrated in colour, p. 71). This exhibition later travelled to London, Serpentine Gallery and Manchester, The Whitworth Art Gallery, The University of Manchester.

Brescia, LOLMOCOLMO, Bloom: Contemporary Art Garden, 1999 (detail illustrated in colour, unpaged).

London, Tate Britain, Chris Ofili, 2010, pp. 34 and 166 (detail illustrated in colour on the cover; installation view at Contemporary Fine Arts in 1997 illustrated in colour, p. 15; illustrated in colour, p. 35; and detail illustrated in colour on the exhibition poster).

New York, New Museum, Chris Ofili: Night and Day, 2014-2015, pp. 150 and 210 (installation view at Tate Britain in 2010 illustrated in colour, p. 140; illustrated in colour, p. 151; installation view at Contemporary Fine Arts in 1997 illustrated in colour, p. 158).

LITERATURE: Painting Codes, exh. cat., Monfalcone, GC. AC. Galleria Communale d'Arte Contemporanea di Monfalcone, 2006, no. 4 (detail illustrated in colour, p. 54; illustrated in colour, p. 57).

D. Adjaye, P. Doig, O. Enwezor, T. Golden & K. Walker, Chris Ofili, New York 2009, pp. 54 and 263 (illustrated in colour, p. 61).

PABLO PICASSO

Portrait de Dora Maar, 1937

Musée Picasso, Paris.

Artwork: © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2025. Digital image: © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2025 / Bridgeman Images.

Asublime early masterwork by Chris Ofili, Blossom (1997) is an emphatic celebration of colour and texture. Amid a chromatic, dreamlike reverie, the titular figure is poised and seductive, her diaphanous dress billowing in soft curves as she bares one breast. Raising her hands to her face, slender red nails frame bold fuchsia lips and periwinkle blue eyes. She poses amid creeping tendrils of aquamarine, magenta, and crimson, crowned with a single orange flower. The towering, crystalline foliage is conjured with pearlescent, enamel-like beads of pigment, which catch the light like filigree. Receding into the depths of the picture plane, lush vegetation fades into a milky, translucent haze of orange, pink and turquoise resin. Laced with shimmering glitter, the resin spills across the surface, bleeding in thick rivulets towards its edges. Ofili turned the painting as he worked, so that it drips upwards and sideways in defiance of gravity. Crowned in a regalia of painted flora and the artist’s trademark medium of elephant dung, Blossom unites Ofili’s consummate mastery of medium with his critical study of the base, beautiful, sacred and profane.

‘The only way to really exist is to produce something that has a dialogue with the world’

Chris Ofili

Blossom was acquired by Ole Faarup in 1997, and has been prominently exhibited under the Danish collector’s stewardship. First exhibited that year in the provocatively titled Pimpin ain’t easy but it sure is fun, Ofili’s first solo show in Berlin, it hung as one among a painted pantheon of powerful black women. The following year it was included in the artist’s seminal first institutional exhibition, which travelled from the Southampton City Art Gallery to the Serpentine Gallery, London, and the Whitworth Museum, Manchester across 1998-1999. This exhibition cemented Ofili’s rapidly growing reputation and elicited a Turner Prize nomination. His receipt of the prestigious award that year was a watershed moment; he was the first black artist and first painter in over a decade to win, the intervening years having been dominated by a sculptural and conceptual turn in British art. More recently, Blossom was included in the artist’s acclaimed mid-career retrospective at Tate Britain, London, in 2010—for which it served as the poster and the cover of the catalogue—as well as the major survey Chris Ofili: Night and Day at the New Museum, New York, in 2014-2015.

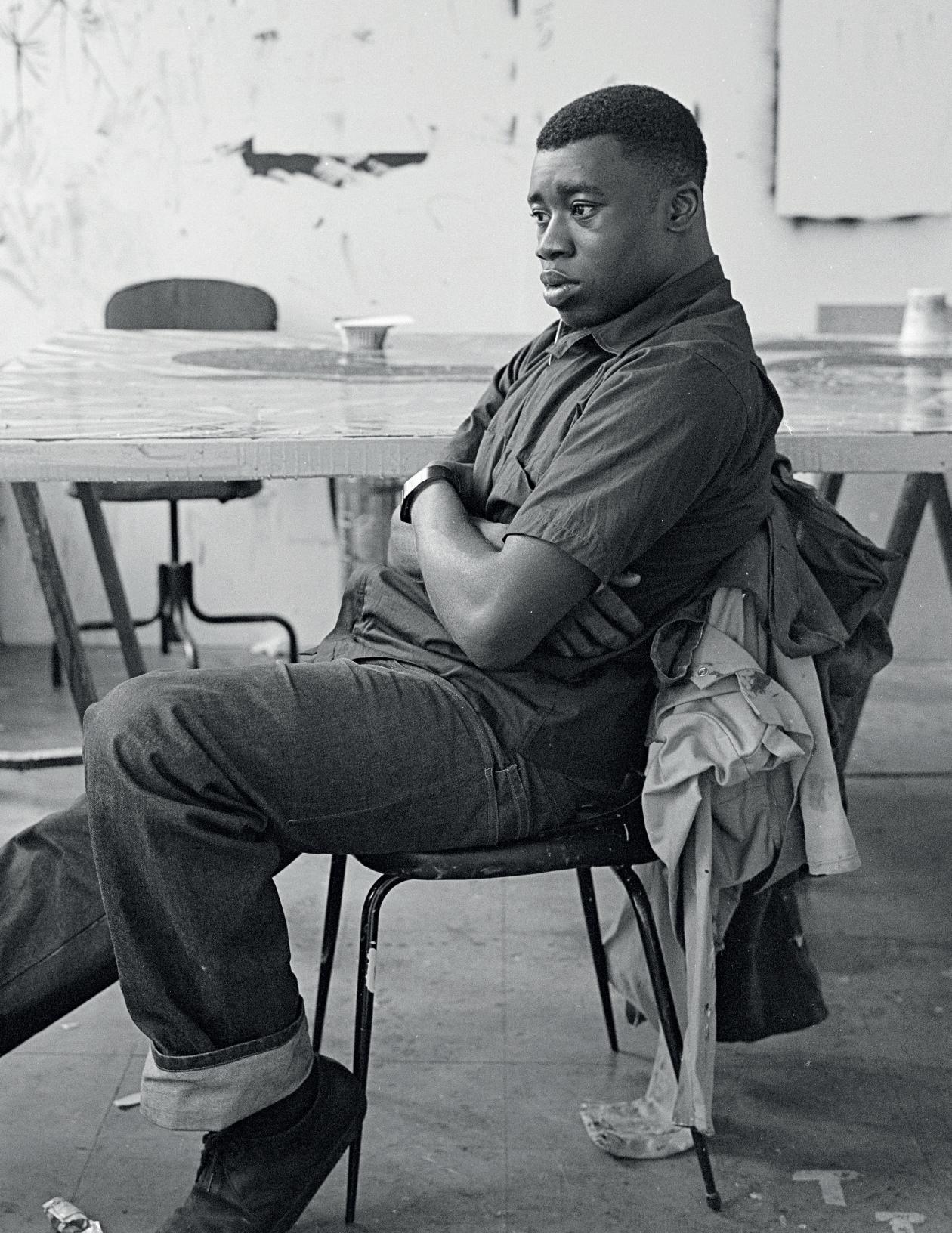

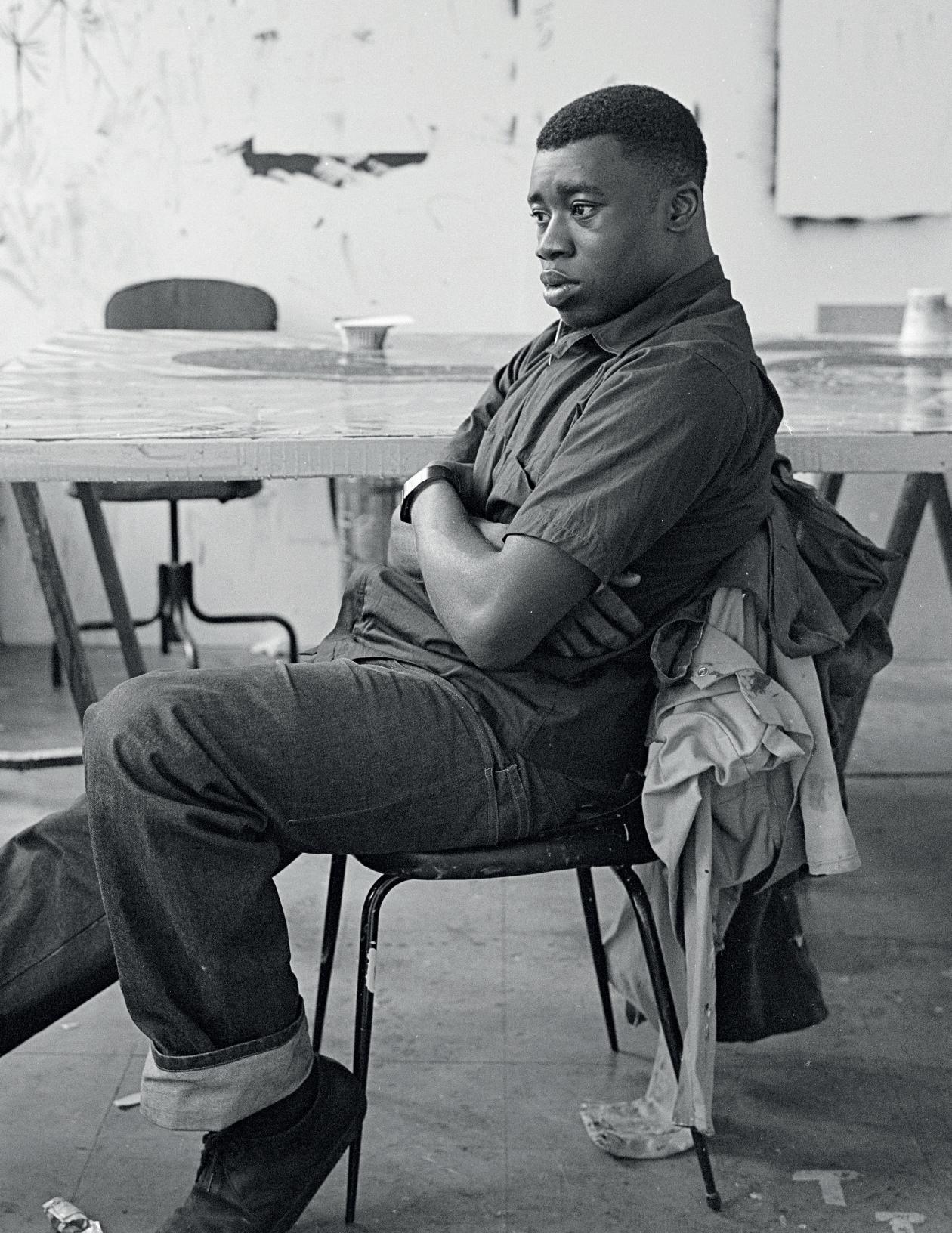

Chris Ofili photographed in the artist’s studio, King's Cross, London, 1999.

National Portrait Gallery, London. Photograph © Stephen Gill.

Detail of the present lot reproduced on the poster for Chris Ofili at Tate Britain, 2010.

Photo: © Tate. Artwork: © Chris Ofili.

The present lot exhibited alongside The Holy Virgin Mary (1996, Museum of Modern Art, New York) and No Woman, No Cry (1998, Tate, London) in Chris Ofili, Tate Britain, 2010.

Photo: © Tate Artwork: © Chris Ofili.

The present lot exhibited during Chris Ofili: Day and Night at the New Museum in New York, 2014-2015.

Photo by Maris Hutchinson/EPW. Artwork: © Chris Ofili.

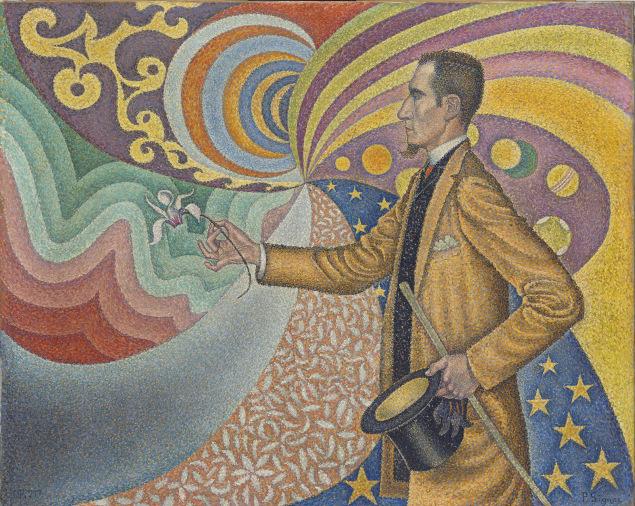

PAUL SIGNAC

Portrait de Félix Fénéon, Opus 217. (Sur l’émail d’un fond rythmique de mesures et d’angles, de tons et de teintes, portrait de M. Félix Fénéon en 1890), 1890-1891

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital image: © 2025 The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence.

‘The paintings are layered. My surfaces are always about seduction’

Chris Ofili

Seeking to examine and extend the possibilities of painting, Ofili’s oeuvre was characterised from the beginning by richly layered and alluring surfaces. ‘That was it for me,’ he recalled of first picking up a brush (C. Ofili quoted in Chris Ofili, exh. cat. Tate, London 2010, p. 8). Blossom is an unabashed celebration of paint, in which Ofili’s emblematic painted dots—inspired by the ancient cave paintings of the Motobo National Park in Zimbabwe, and reminiscent of Australian Aboriginal dot painting—gleam atop pooling, jeweltoned resin, through which earlier layers of paint are glimpsed as if preserved under glass. They unfurl in patterns of delicate floral tracery and coalesce to conjure the woman’s rippling gown, softly curving flesh and perfectly coiffed afro.

Blossom is supported from the ground by two pedestals of elephant dung. Further orbs descend along the left-hand edge of the work, studded with jewel-like map pins that spell out its title. Ofili’s use of the material—sourced from London Zoo—was an early and defining intervention in his practice. In 1992, while studying at the Royal College of Art, he received funding from the British Council to attend the Pachipamwe International Artists’ Workshop in Zimbabwe. It was the first time the artist, born to Nigerian parents who had recently moved to Britain, had visited the African continent. In a direct and impulsive effort to bring the landscape into his practice, Ofili affixed a ball of dung to one of his works. He identified a striking aesthetic dissonance between the beauty of the painted surface—at that time he was working in a fluid and modernist abstract style—and the earthy coarseness of the dung.

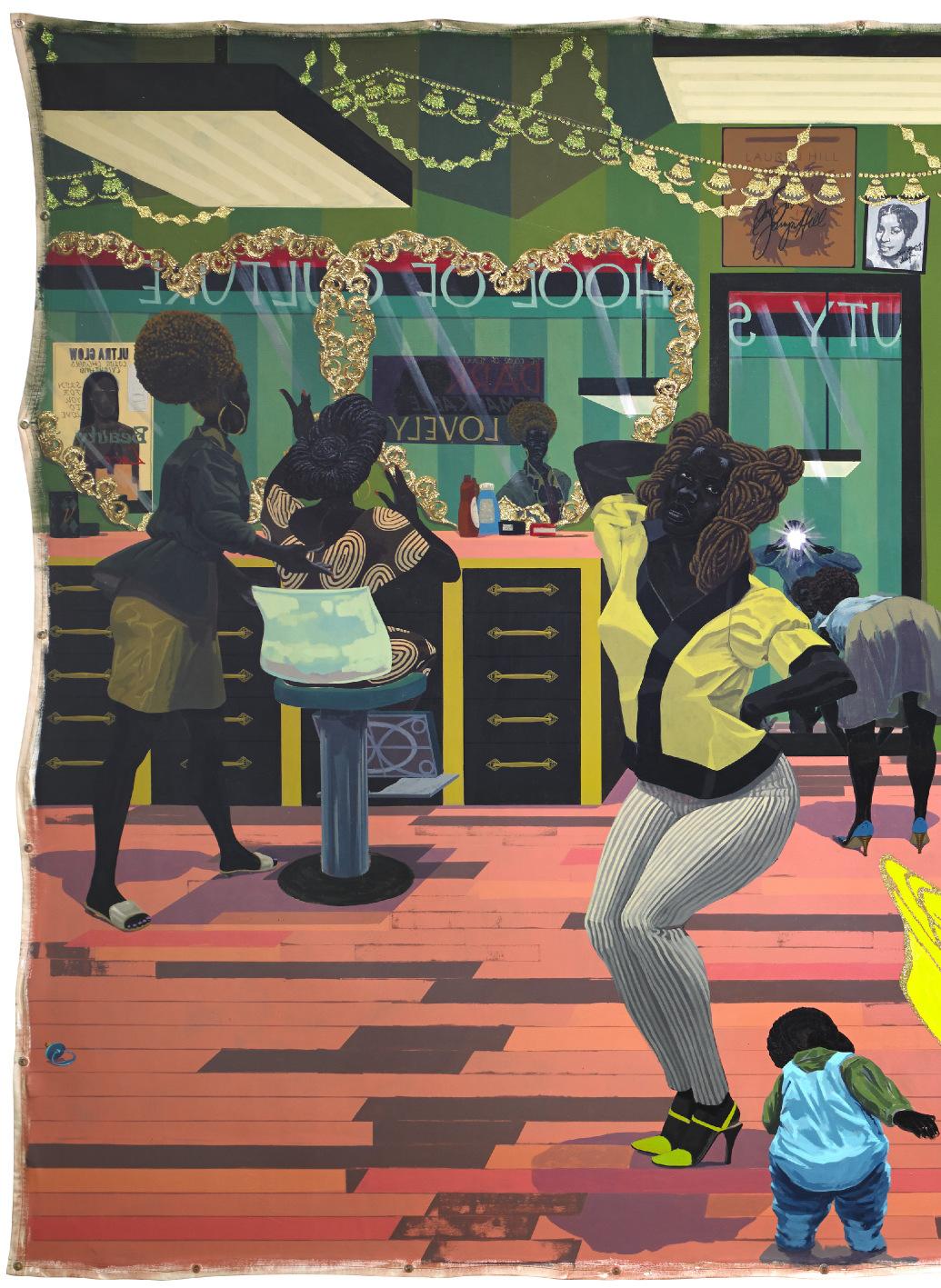

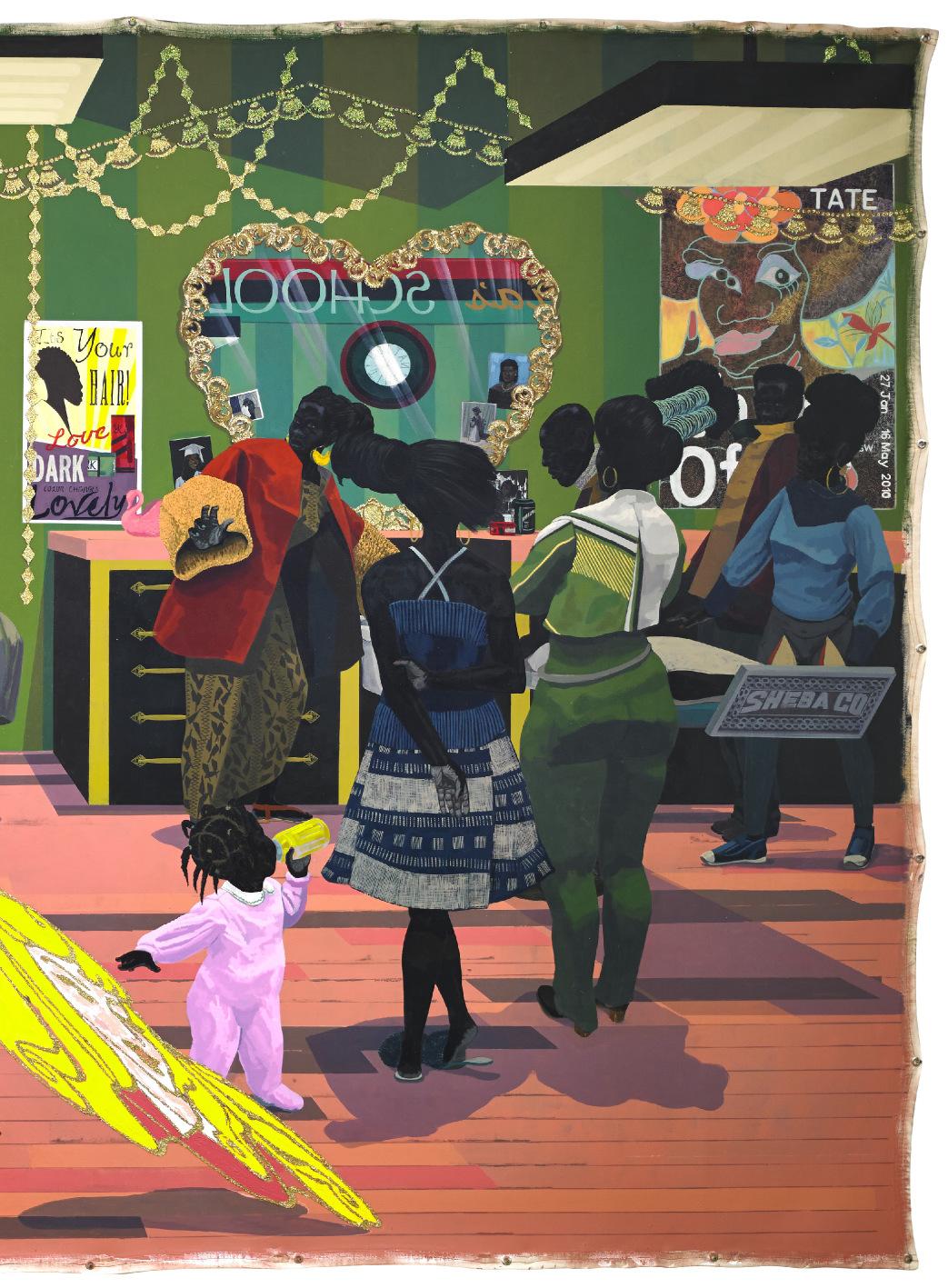

KERRY JAMES MARSHALL

School of Beauty, School of Culture, 2012

Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, Alabama. Artwork: © Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, London. Digital image: Collection of the Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama; Museum purchase with funds provided by Elizabeth (Bibby) Smith, the Collectors Circle for Contemporary Art, Jane Comer, the Sankofa Society, and general acquisition funds. Photo: Sean Pathasema.

‘In that practice of examining being black and examining being Afro, there has been so much to learn’

Chris Ofili

Drawing on the Duchampian concept of the readymade, Ofili’s prolific use of elephant dung as an artistic medium echoed Georges Bataille’s theory of informe, or formlessness. First articulated in 1929 in Bataille’s dissident surrealist journal Documents, informe sought ‘to bring things down in the world,’ advocating the dissolution of art-historical distinctions between ‘high’ and ‘low’. At the time of the present work’s execution the concept of informe had been newly exhumed. The year prior, a major exhibition by Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, had centred formlessness as a lens through which to understand the trajectory of contemporary art history, from Pablo Picasso’s collages of discarded rubbish to Jackson Pollock laying his canvases on the floor and Cy Twombly’s graffiti-like aesthetic. Lifting his works from the wall and placing them instead on excrement, Ofili offered a provocative and timely continuation of informe.

A year before he painted Blossom, Ofili relocated from a studio in London’s Chelsea Harbour to King’s Cross. The roaring sex and drugs trade which neighboured his new studio inspired the Berlin exhibition in which Blossom was first exhibited. ‘I wouldn’t have done it if I didn’t work in King’s Cross,’ Ofili reflected on the series. ‘Those works came out of being here. I wouldn’t have made those paintings if I was in Chelsea Harbour’ (C. Ofili quoted in Chris Ofili, exh. cat. Southampton City Art Gallery, Southampton 1998, p. 87). Blossom draws on archival black and white pornography images taken from magazines Ofili purchased in shops around King’s Cross, fronted as traditional bookshops. He was playing with the idea of beauty, and of what is allowed or not allowed to be considered beautiful, and the incorporation of bejewelled, resin-coated elephant dung into the work was integral to this project.

CHRIS OFILI No Woman, No Cry, 1998 Tate, London.

Artwork: © Chris Ofili. Digital image: © Tate.

The same year Ofili moved to King’s Cross, the British Film Institute—then called the National Film Theatre—at London’s Southbank Centre staged a ‘blaxploitation season,’ showing classic films of the early 1970s genre such as Coffy, Black Caesar, and Mandingo. Distinguished by baffling slang, vitriolic insults, and a cast of black ‘types’, it was the first time many of these films had been aired in Britain, and Ofili went to every showing. Blossom pays tribute to pioneering actress Pam Grier, whose starring role as Blossom in The Big Bird Cage (1972) saw her devise an ill-fated plan to liberate the inmates of a women’s prison. Later roles as the titular vigilantes Coffy (1973) and Foxy Brown (1974) would make Grier cinema’s first female action star and a face of the blaxploitation genre. In each of these roles Grier wore her hair in a regal, electrifying afro. In her autobiography she later reflected ‘what really stood out in the genre was women of colour acting like heroes ... street-smart women who were proud of who they were. They were far more aggressive and progressive than the Hollywood stereotypes’ (P. Grier in conversation with R. Gilbey, ‘I was part of a female cinematic revolution’, The Guardian, 3 September 2022). With its subject’s name blazoned down the painting’s edge, Blossom draws on the aesthetic of film posters to present a heroic depiction of black womanhood.

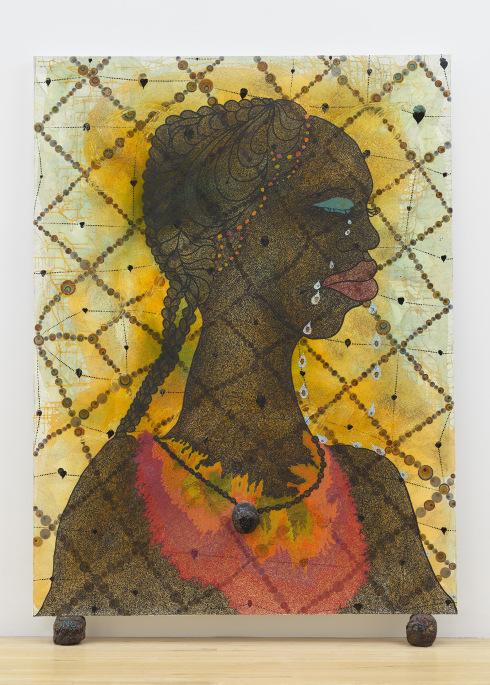

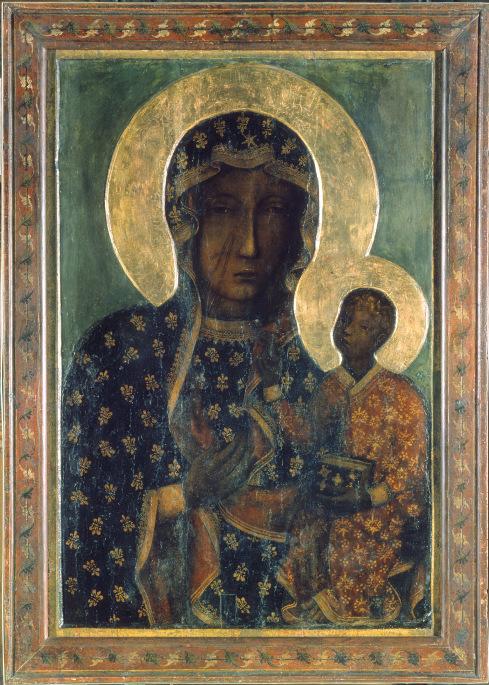

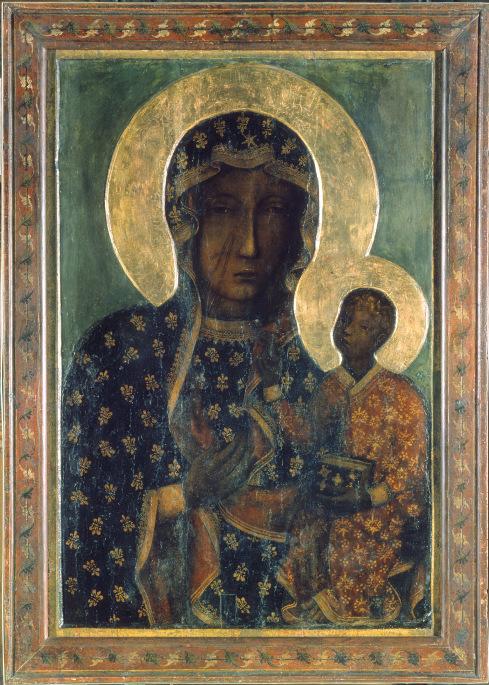

Our Lady of Czestochowa Byzantine icon Jasna Gora Monastery, Czestochowa.

Digital image: © Photo Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

Blossom was painted between two icons of Ofili’s practice: the now infamous The Holy Virgin Mary (1996, Museum of Modern Art, New York) and the poignant No Woman, No Cry (1998, Tate, London). The exposed breast in Blossom mirrors that of his celebrated black Madonna, drawing provocatively on traditional depictions of the mother and child. ‘When I go to the National Gallery and see paintings of the Virgin Mary, I see how sexually charged they are,’ explained Ofili. ‘Mine is simply a hip-hop version’ (C. Ofili, quoted in Chris Ofili, exh. cat. Tate, London 2010, p. 17). Ofili’s monumental depictions of black women played a critical role in his dismantling of aesthetic hierarchies, and his driving desire to reflect his own contemporary black experience. The American painter Kerry James Marshall paid tribute to Blossom’s impact in his painting School of Beauty, School of Culture (2012, Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, Alabama), which included the exhibition poster for Ofili’s 2010 Tate retrospective amid a rich tableau of art-historical and black cultural references. Powerfully uniting the sacred and profane, Blossom is a visual tour de force, an exemplar of Ofili’s technical virtuosity, and a sumptuous celebration of paint.

PETER DOIG (B. 1959)

Concrete Cabin

signed, titled and dated ''CONCRETE CABIN' '93 Peter Doig' (on the reverse) oil on plywood

15 x 20¿in. (38 x 51cm.)

Painted in 1993

£450,000-650,000

PROVENANCE: Victoria Miro Gallery, London. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 1994.

EXHIBITED:

Kiel, Kunsthalle zu Kiel, Peter Doig: Blizzard seventy-seven, 1998, p. 133, no. 9 (incorrectly titled 'Briey' and dated '1994'; illustrated in colour, p. 88). This exhibition later travelled to Nuremberg, Kunsthalle Nürnberg and London, Whitechapel Gallery.

PIET MONDRIAN

Composition with large red plane, yellow, black, grey and blue, 1921

Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague.

Digital image: © Kunstmuseum den Haag / © Mondrian/Holtzman Trust / Bridgeman Images.

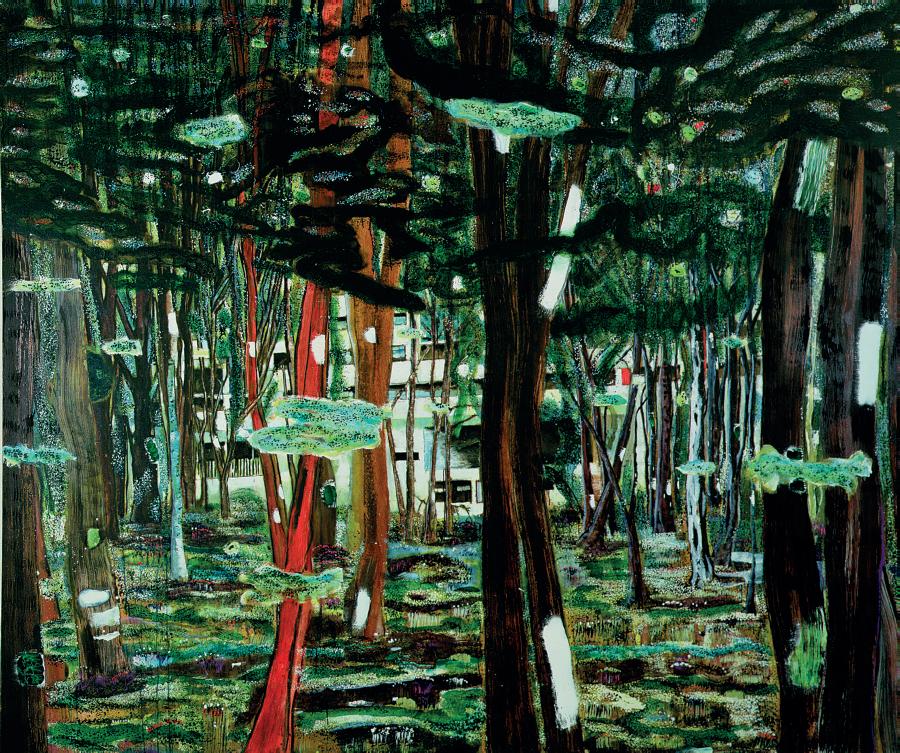

Acquired by Ole Faarup in 1994, Concrete Cabin (1993) is a vivid, deeply textural painting from one of Peter Doig’s most celebrated series. The ‘Concrete Cabin’ works occupied the artist for much of the 1990s. Inspired by an encounter with Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation housing project in Briey-enForêt, France, they depict the building’s Modernist façade as seen through the trees of the surrounding woodland. They form poignant meditations on utopian dreams, mankind’s place in nature and the passage of time. In the present work, the building—bright white, with flashes of blue, purple and red—is glimpsed through a screen of dark greenery and fiery orange tree-trunks. Doig’s thick, tactile impasto charges the forest with life. Globules of white paint, derived from his paint-spattered source photograph, add a further layer of intrigue. The work has been unseen in public since its inclusion in Doig’s major exhibition Blizzard seventy-seven, which toured the Kunsthalle Kiel, the Kunsthalle Nürnberg and Whitechapel Gallery, London in 1998.

Completed in 1960, the Unité d’Habitation of Briey—like its counterparts in Marseille and elsewhere—was a beacon of hope and community in post-war Europe. Le Corbusier envisioned a modular system that would allow for a complete way of life in one building, and the distinctive concrete structures became exemplars for what would later be known as Brutalism. By the time Doig visited in 1991, the Unité at Briey had been abandoned. Its contrast with the forest had a powerful emotional impact. ‘I never dreamed that I would end up painting it’, Doig said. ‘I went for a walk in the woods on one visit, and as I was walking back I suddenly saw the building anew. I had no desire to paint it on its own, but seeing it through the trees, that is when I found it striking’ (P. Doig in conversation with K. Scott, in A. Searle et al. (eds.), Peter Doig, London 2007, p. 20). Le Corbusier’s woodland setting had proposed an idealised meeting between nature and culture. For Doig, the sight of the architecture’s geometry amid the encroaching branches instead evoked a sense of loss and folly.

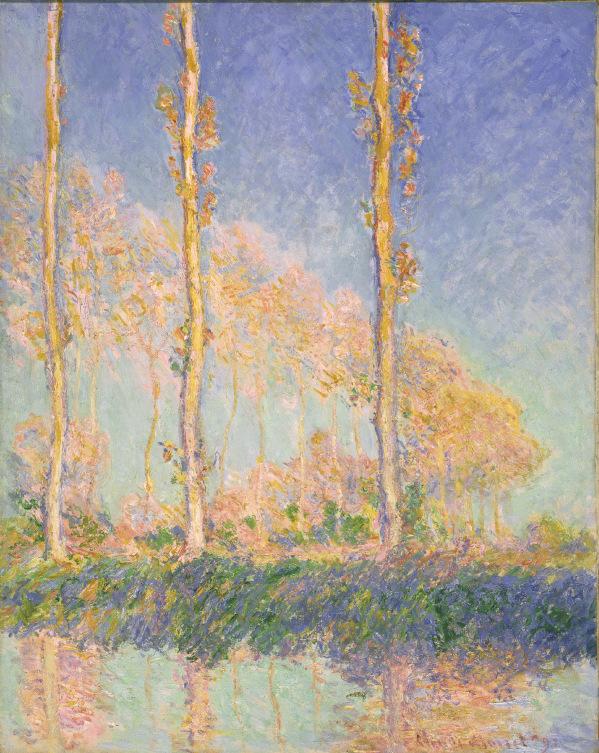

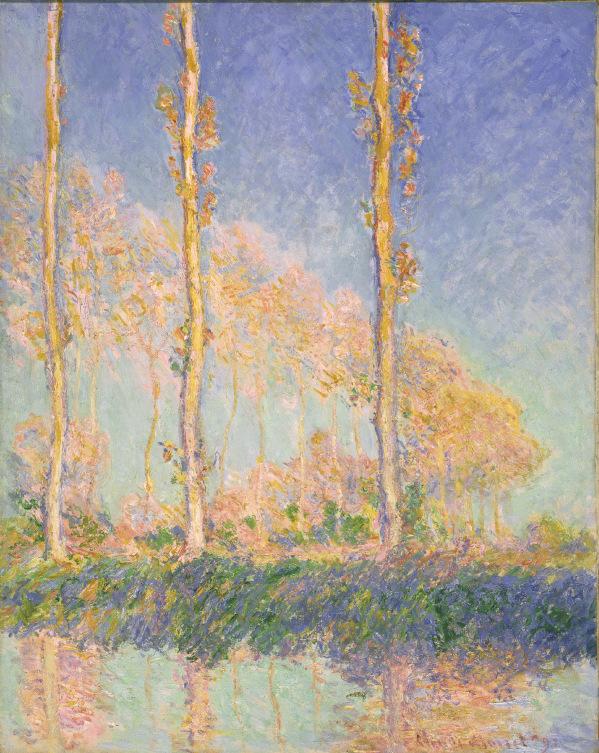

Poplars, Three Trees in Autumn, 1891

The Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Digital image: The Philadelphia Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

‘I was surprised by the way the building transformed itself from a piece of architecture into a feeling’

Peter Doig

CLAUDE MONET

PETER DOIG

Concrete Cabin, 1991-1992

New Walk Museum & Art Gallery, Leicester.

Artwork: © Peter Doig. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025.

Doig took photographs and recorded a video of his approach towards the building, which became the basis of his drawings and paintings. He incorporated the marks and splashes that the printed images gathered during their time in his studio. These abstract, amorphous shapes hover before the tangled trees, adding to the works’ air of mystery and dereliction. Doig had already painted cabins and other modest dwellings—often inspired by his youth in Canada, and masked by foliage or snowfall—but the Unité was different. ‘Whereas other buildings had represented a family or maybe a person somehow,’ he said, ‘this building seemed to represent thousands of people’ (P. Doig, ibid.). For him, this haunting quality was heightened by its proximity to the countless First World War graveyards he had driven through in northern France.

Weaving together painterly, personal and cultural strands of experience, the ‘Concrete Cabins’ have become emblematic of Doig’s practice. Several large-scale paintings from the series were included in his 1994 Turner Prize installation at the Tate, and one is now held in New Walk Museum and Art Gallery, Leicester. The present work condenses their wistful magic into a jewel-like, richly worked vision, alive with narrative suspense. The built structure is almost entirely obscured by the trees, which impose their own organic verticals and horizontals upon the picture. As in so many of Doig’s works, this screening device also pictures the overlay and transformation inherent to the act of memory—a pictorial whole, or unity, remaining just beyond reach.

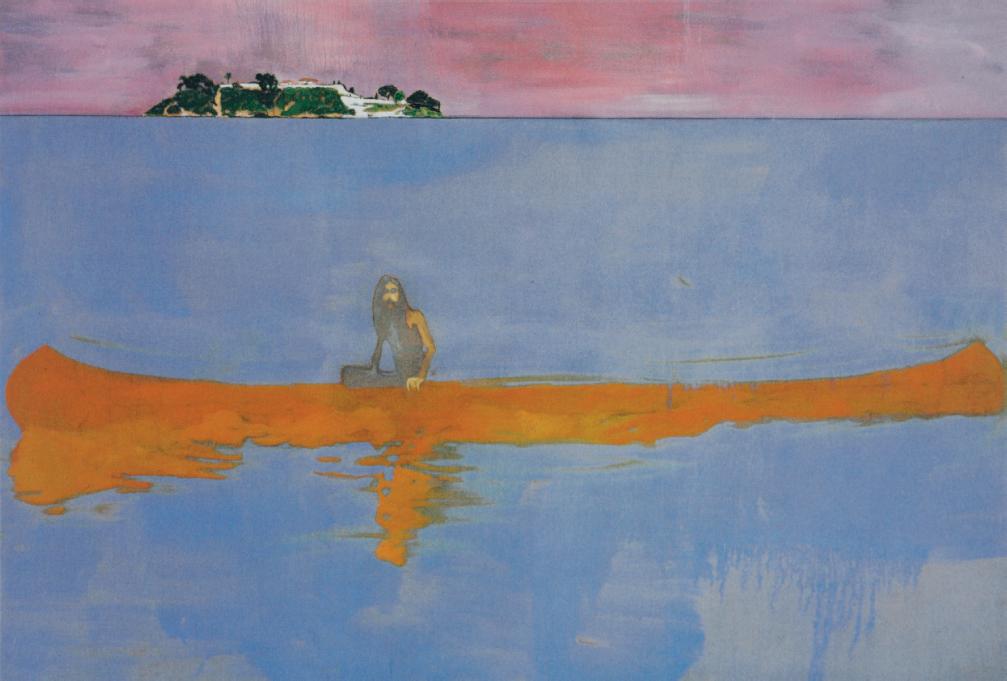

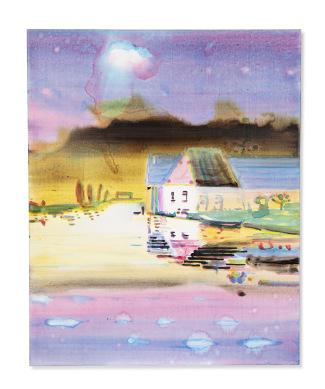

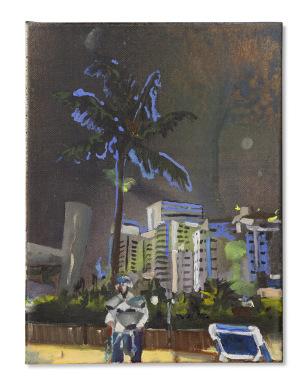

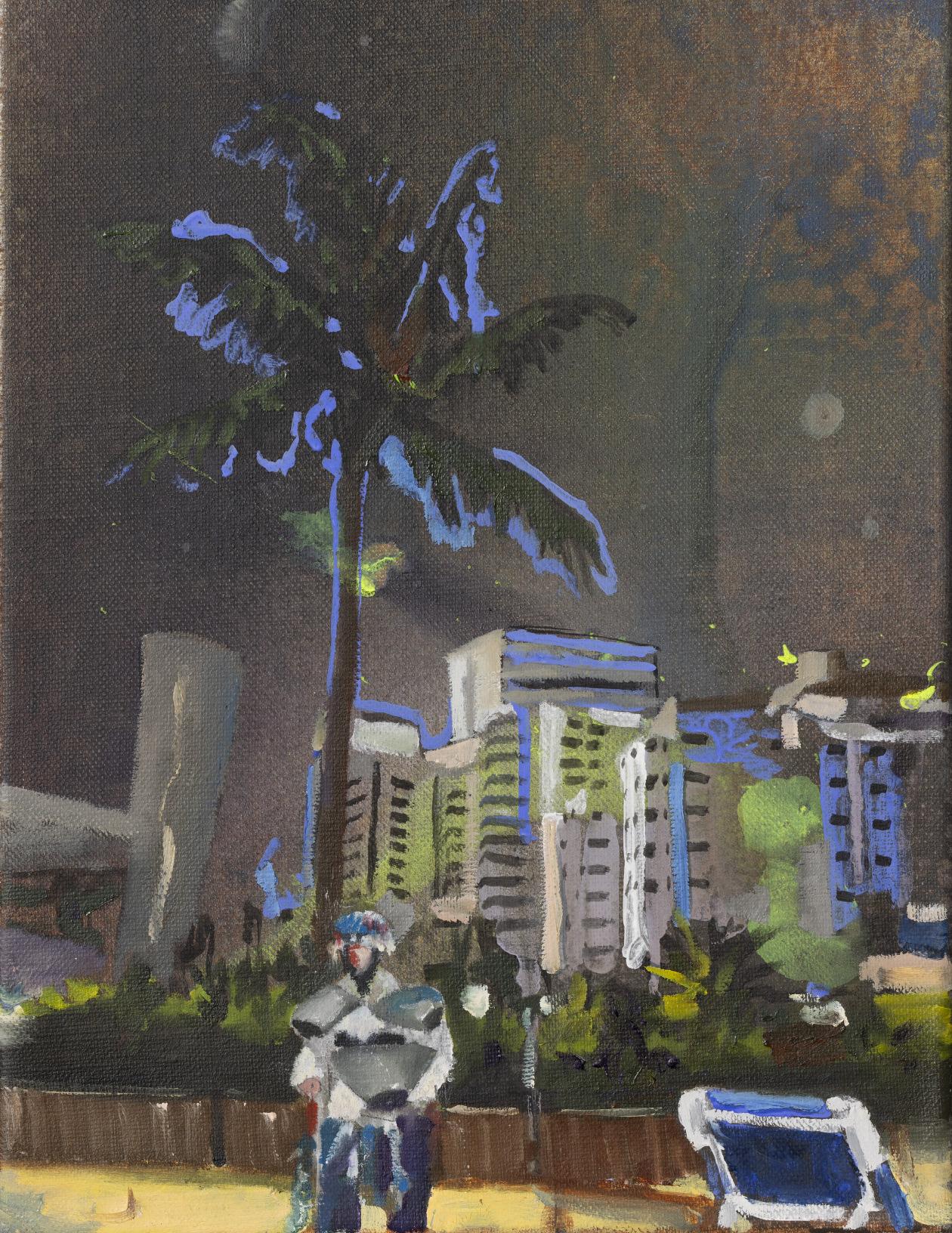

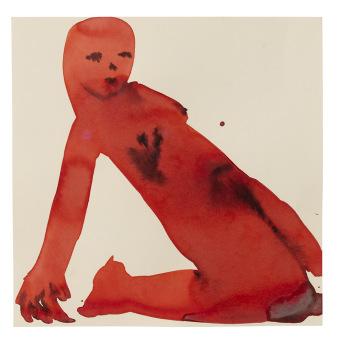

PETER DOIG (B. 1959)

Yara

signed and dated 'Doig 2001' (on the reverse); signed and dated 'Doig 2001' (on a label affixed to the backing board) watercolour on paper 22Ω x 15æin. (57.2 x 39.8cm.)

Executed in 2001

£120,000-180,000

PROVENANCE: Victoria Miro Gallery, London. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 2002.

EXHIBITED: Dallas, Dallas Museum of Art, Peter Doig - Works on Paper, 2005-2006, p. 168, no. 84 (with incorrect dimension; illustrated in colour, p. 93). This exhibition later travelled to Vero Beach, The Gallery at Windsor and Toronto, Art Gallery of Ontario. London, Tate Britain, Watercolour, 2011, p. 202, no. 126 (with incorrect dimension; illustrated in colour, p. 177).

LITERATURE: Peter Doig - Charley's Space, exh. cat., Maastricht, Bonnefantenmuseum, 2003, p. 138 (incorrectly titled 'Untitled (Yara)' and dated '2002', with incorrect dimensions; illustrated in colour, p. 134).

‘I think Trinidad took me by surprise in that it’s such a potent place visually: as soon as you open up the door it’s like, boom!’

Peter Doig

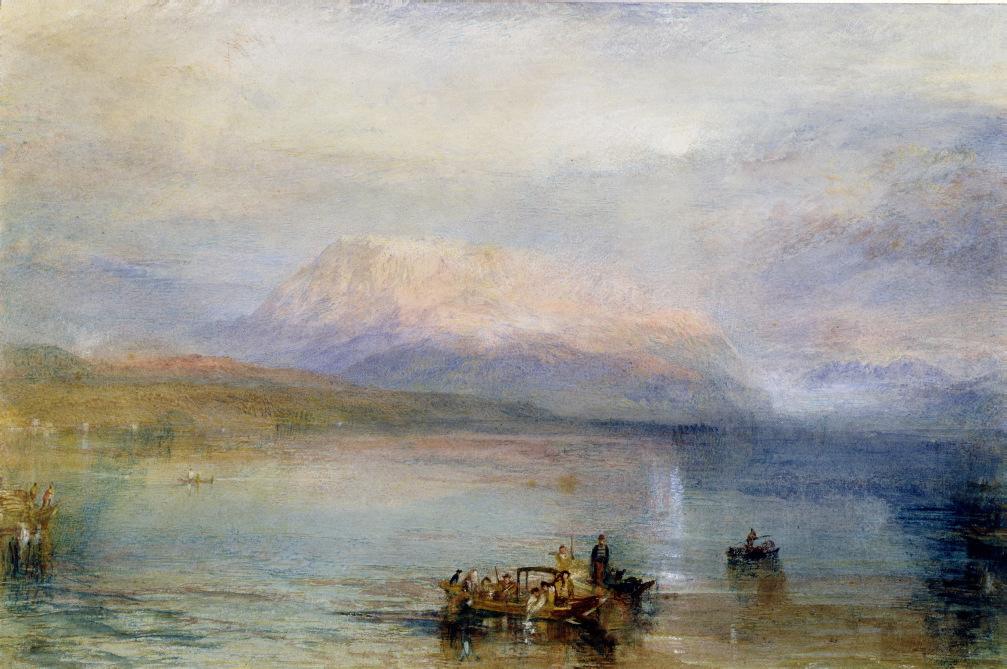

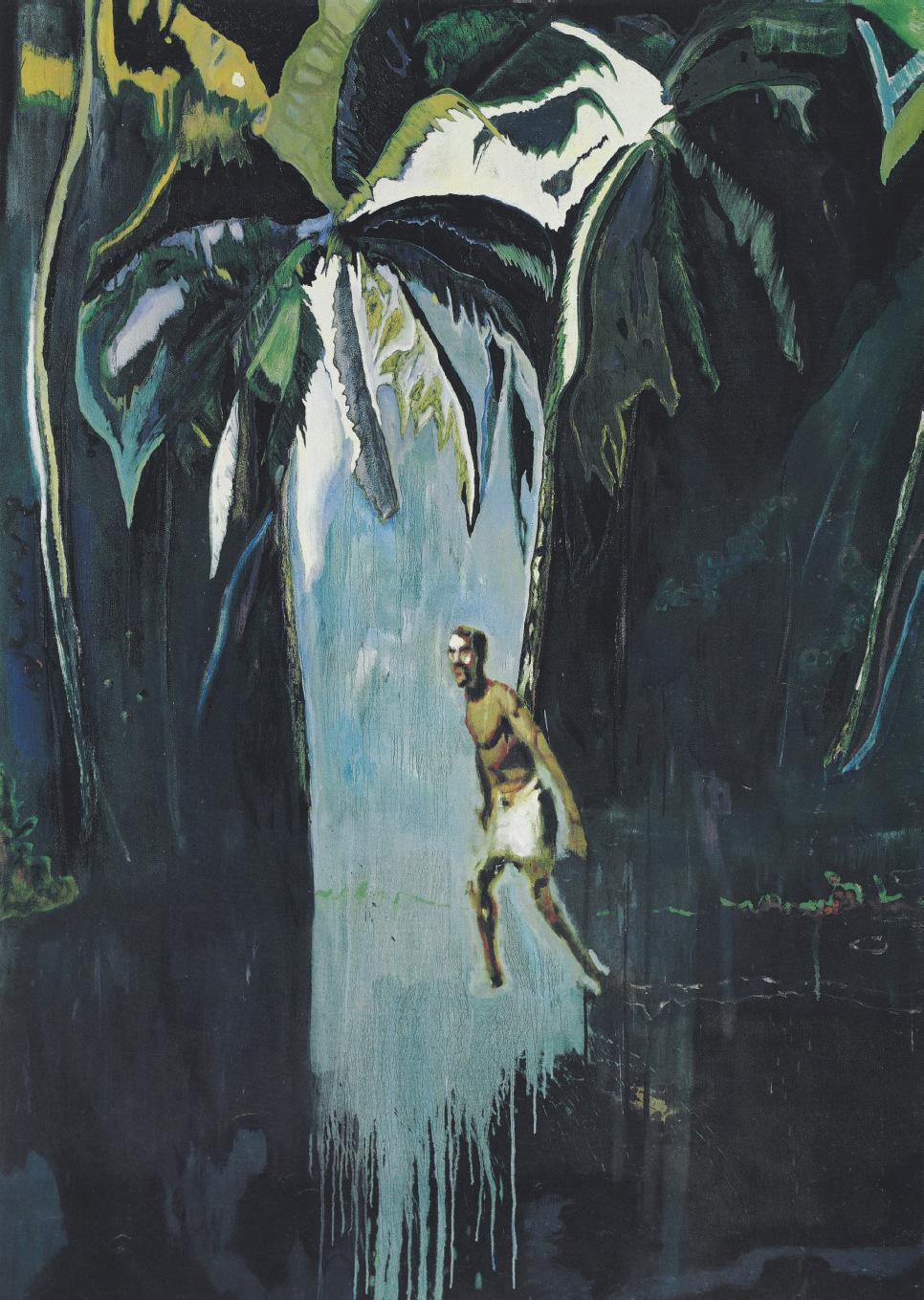

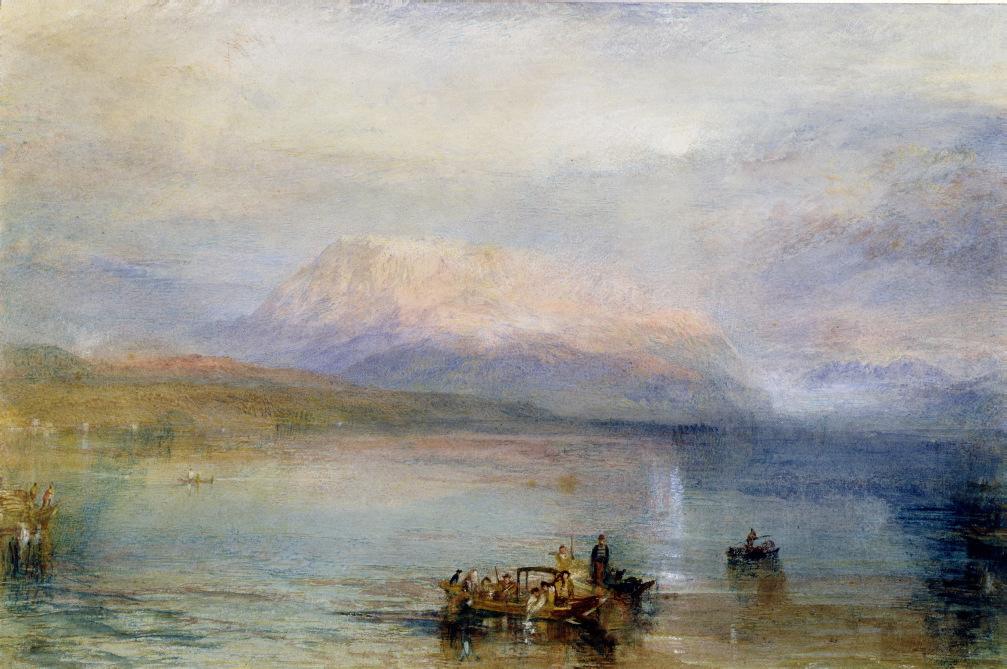

Peter Doig’s exquisite watercolour Yara (2001-2002) captures the magic the artist found on his return to Trinidad: the island where he had spent his early childhood, and where, some forty years later, he made his home. The work depicts Yara Beach, a place which would inspire some of Doig’s most iconic and otherworldly paintings. Bathed in lilac and emerald green, feathery strokes and dripping, aqueous washes convey foliage and glimmering reflections. The bay curves out to a hazy horizon. White pigment sparkles across the surface like ocean spray. Acquired by Ole Faarup soon after its creation, Yara has been exhibited internationally, appearing in Peter Doig: Charley’s Space in Maastricht and Nîmes (2003-2004); Peter Doig: Works on Paper, which opened at the Dallas Museum of Art before travelling to Canada (2005-2006); and—alongside historic masters of the medium such as J. M. W. Turner—in Tate Britain’s centuries-spanning group exhibition Watercolour (2011).

Following his father’s work for a shipping company, Doig’s family moved from Scotland to Trinidad when he was two years old, and to Canada when he was seven. He grew up between Canada and Scotland, eventually studying art in London, where he rose to fame during the 1990s. In 2000, Doig joined his friend Chris Ofili on a month-long residency in Trinidad, which rekindled his fondness for the island: he settled there with his family two years later, and Ofili followed soon afterwards. Together the two artists would kayak around the bays and islets of the north coast, exploring ‘incredible landscapes and caves, archaic spaces, natural cathedrals, and chasms, strange pelicans …’ (P. Doig quoted in C. Ofili, ‘Peter Doig by Chris Ofili’, BOMB, 1 October 2007). An encounter between a man and a bird they witnessed on Yara Beach led to Doig’s landmark paintings Pelican (Stag) (2003) and Pelican (2004). With its looming palm trees and ethereal palette, Yara echoes those works’ mysterious, supernatural grandeur.

Doig’s work had long been defined by the dynamics of memory, movement and mediation. He approached subjects via secondary sources and veiled them in painterly layers—only depicting Canada, for example, from the distance of London. While these themes remained important, Trinidad led to a marked shift in his practice. The environment demanded a direct response. ‘I think Trinidad took me by surprise’, Doig said, ‘in that it’s such a potent place visually: as soon as you open up the door it’s like, boom! … I don’t think I’m referring back to my past here, [the work] seems to be more about things I’m experiencing in the here and now’ (P. Doig quoted in L. Buck, ‘Interview with Peter Doig on how Trinidad gave his art immediacy’, The Art Newspaper, 1 February 2008).

After initially working with postcards and other found images, Doig began to take snapshots on his coastal excursions, and, later, would sometimes paint without photographs altogether. In hallucinatory hues, dilute textures and increasingly essentialised form, he distilled the island’s extraordinary atmosphere into luminous, lucid visions that reached a transcendent new plane. ‘I don’t think of the present day as being that important to depict’, he said. ‘A painting becomes interesting when it becomes timeless’ (P. Doig quoted in ibid.). In Yara, he conjures an eternal, primal image of the shore—a place between—that could be seen now, a thousand years ago, or only in a dream.

J. M. W. TURNER

The Red Rigi, 1842

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Digital image: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne / Felton Bequest / Bridgeman Images.

PETER DOIG Pelican (Stag), 2003

Private collection.

Artwork: © Peter Doig. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025. Digital image: © Peter Doig. All Rights Reserved, DACS Images. Photo: Jochen Littkemann. 73

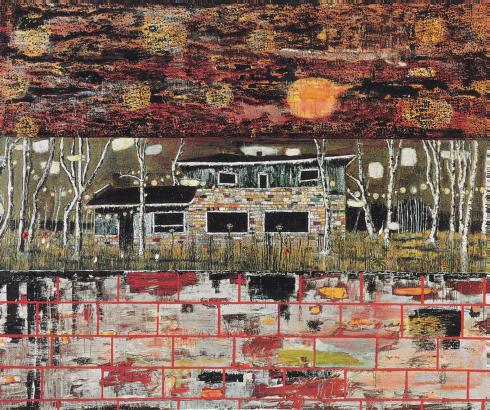

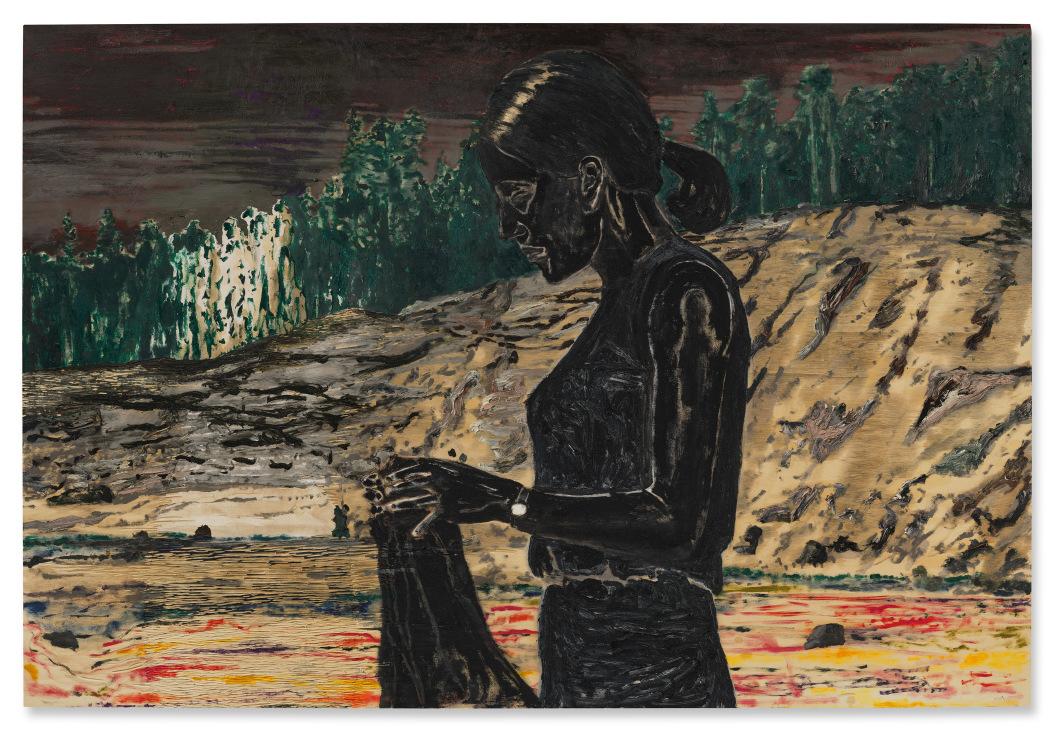

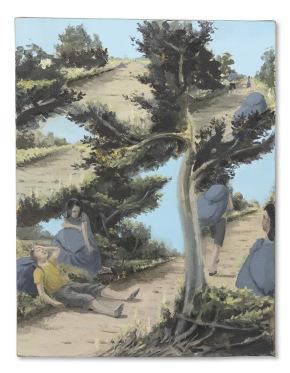

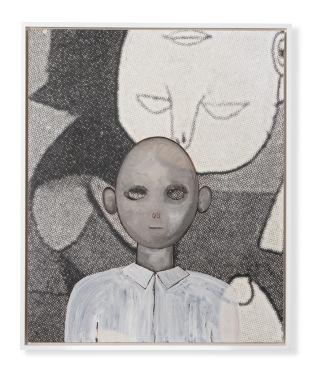

KARIN MAMMA ANDERSSON (B. 1962)

Hon (She)

signed, titled and dated 'Hon 2013 Mamma Andersson' (on the reverse) oil on panel

42æ x 63ºin. (108.5 x 160.5cm.)

Painted in 2013

£150,000-200,000

PROVENANCE: Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Stockholm. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 2013.

EXHIBITED: Stockholm, Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Time Waits for Us, 2013.

‘It is just daily life that interests me, all those days that just go on. It is in them that great events take place, right in front of us’

Karin Mamma Andersson

In Hon (She) (2013), Karin Mamma Andersson revels in the slipperiness of paint and memory, and the monumentality of ordinary moments. Dominating the composition, a lone female figure looks down towards a swathe of fabric held in her hands. Her hair is tied in a low ponytail, which curves gently into the nape of her neck. Painted in black, she seems removed from the delicately technicolour scene which unfolds beyond her: under a mauve sky, a regiment of towering birch trees follows the craggy contours of a rockface which descends, in impasto crests and hollows of raw panel, to meet a body of water below. Gesturally painted, the landscape might exist only in the hazy recesses of the woman’s memory. Yet she is tethered to the scene by the rays of a setting sun, which illuminate the trees and fleck the water and sky with yellow, crimson, and royal purple, and glint, too, on the crown of her head and the round white face of her watch. An inveterate ‘painter’s painter’, Andersson’s breakthrough came in 2003 when she exhibited as part of the Nordic Pavilion at the 50th Venice Biennale. Painted a decade later and acquired by Ole Faarup that same year, Hon followed a host of highly acclaimed institutional surveys of the artist’s work, including at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm (2007) and the Aspen Art Museum, Colorado (2010). In 2021, Andersson was the subject of a major retrospective at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk.

Painted in oil on wood panel, the plasticity of Hon is integral to the work. Andersson describes oil paint as a ‘tensile’ medium; like memory, it is amorphous and pliable. By turns breathy and viscous, it hovers precariously upon the coarse wood surface—visible through broad passages of the picture plane—as though at any moment the illusion it conjures will collapse. The panel itself is poplar, a low-density and finely grained hardwood whose erratic growth patterns are impervious to dendrochronology: the wood assumes an active role in this temporally elusive tableau. Andersson works the panel with rough chisels to evoke rippling water and craggy terrain, countering the delicacy of her brushwork with a tactile and visible weight. The artist originates her unsparing use of black paint—she hand-mixes matte, velvety blacks with burnt umber and cobalt blue, achieving a more vivid colour than can be purchased off the shelf— in the stark visual impact of Japanese woodblock prints. With its graphic, linear quality and tactile grooves and grain, Hon draws on the aesthetic of woodblock printing and its suggestive allusions of a doubled or mirrored reality.

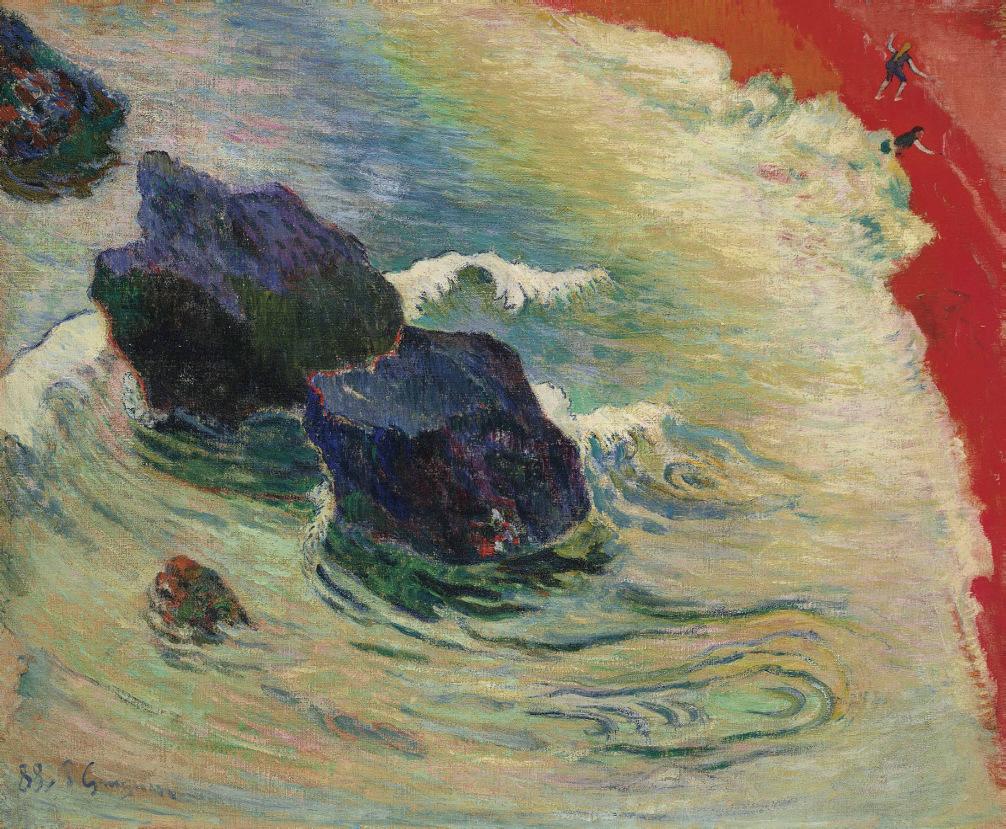

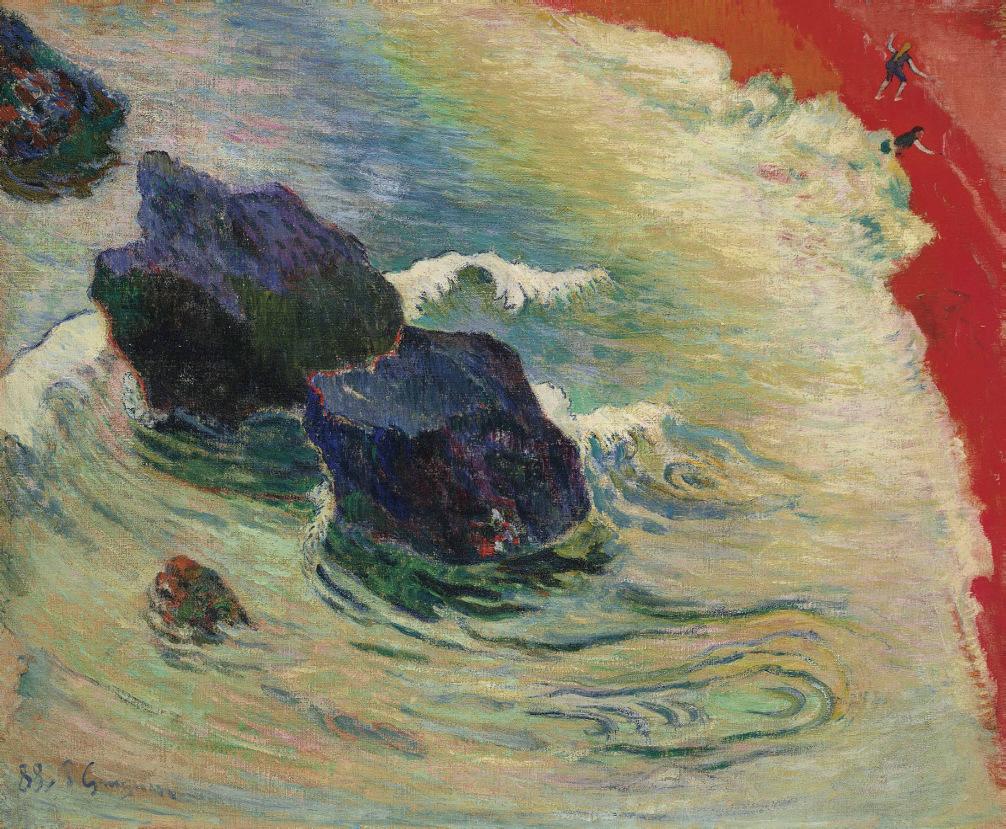

PAUL GAUGUIN

La Vague, 1888

Private collection.

EDVARD MUNCH

Toward the Forest, 1915

Munch Museum, Oslo.

Photo: ©2025 Photo Scala, Florence.

Andersson’s landscapes are typically inspired by archival black and white photographs of Hälsingland, a province in northern Sweden close to her own hometown of Luleå. Sparsely populated, mountainous, and carpeted by dense forest, Andersson identifies a rich psychological potency and temporal ambiguity—the sun barely sets in midsummer, nor rises in midwinter—in this familiar landscape. Black and white photography offers a point of entry into the work from which she might later depart, to draw on disparate sources or her own imagination. She believes that each work contains an element of self-portraiture. ‘You draw from your own well,’ she suggests. ‘Where else would you draw from? It never runs dry’ (M. Andersson in conversation with M. Laurberg, in Mamma Andersson. Humdrum Days, exh. cat. Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk 2021, p. 22).

DICK BENGTSSON

Bergsvandrare, 1974

Stockholm Art Collection.

Artwork: © Dick Bengtsson, DACS 2025.

In paintings such as Hon, Andersson imbues the Romantic terrains of Caspar David Friedrich with the emotional isolation of Edward Hopper, extending a singularly Nordic sensibility in which the human condition is examined through sparse and psychologically charged topographies. As an art student in Stockholm, Andersson worked as a museum guard at the Moderna Museet. The Swedish landscape tradition of artists such as Karl Fredrik Hill and Dick Bengtsson was highly formative—of the latter she writes ‘it is impossible to place him, and a venture into his domain is a reckless adventure. But it is a voyage within a frame’ (M. Andersson, ‘A Voyage Inside a Frame’, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, online). Andersson’s porous paintings are similarly elusive, so that the ‘frame’ remains critical; the borders of her picture planes anchor the viewer amid evocative and unreal worlds.

Alongside contemporaries such as Peter Doig, Luc Tuymans, and Marlene Dumas, Andersson’s oeuvre is shaped by an interrogation of the image. Her paintings are not arbiters of truth but a point of entrance into the vast, murky shores of human memory and the landscapes onto which it latches. Hon feels strikingly cinematic, as though imminently the camera will pan out, and the interior world of the protagonist will be juxtaposed with the vastness of the world she inhabits. Indeed, Andersson’s rich corpus of ordinary domestic interiors, still lifes, and rugged Swedish landscapes forms a kind of painterly noir. ‘I always used to think I would work with film,’ she reflects. ‘I feel I’ve succeeded, because that’s what I do, in a way’ (M. Andersson in conversation with L. Norén, in Mamma Andersson, exh. cat. Moderna Museet, Stockholm 2007, n.p.). Like a film, Hon invites the viewer to enter a new realm, a pictorial ‘elsewhere’, in which memory and time—symbolised by the gleaming, blank watch-face at the centre of the composition—slip, stretch, and are suspended.

‘A painting is always frozen in its own moment in time, and only the viewer can trigger the imagination of a before and after’

Karin Mamma Andersson

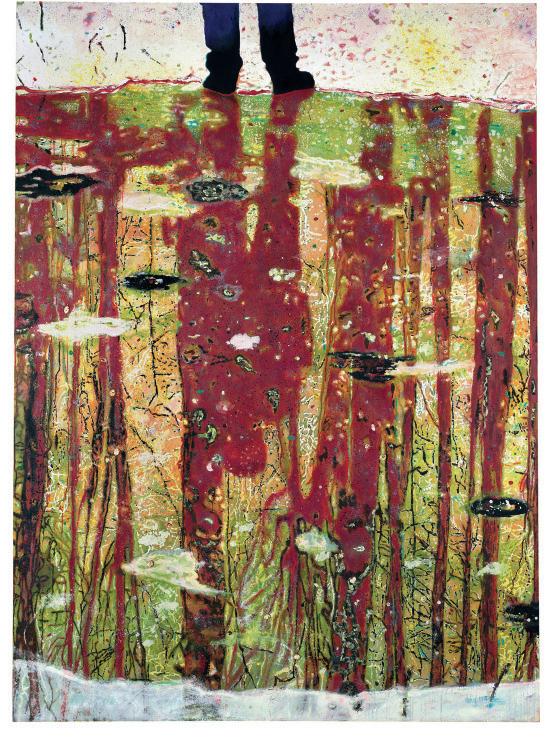

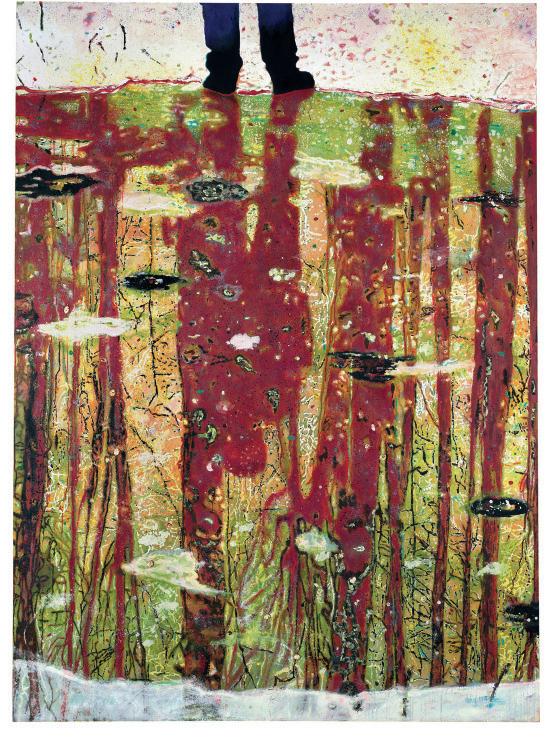

PETER DOIG

Reflection (What Does Your Soul Look Like), 1996 Private collection.

Artwork: © Peter Doig, DACS 2025.

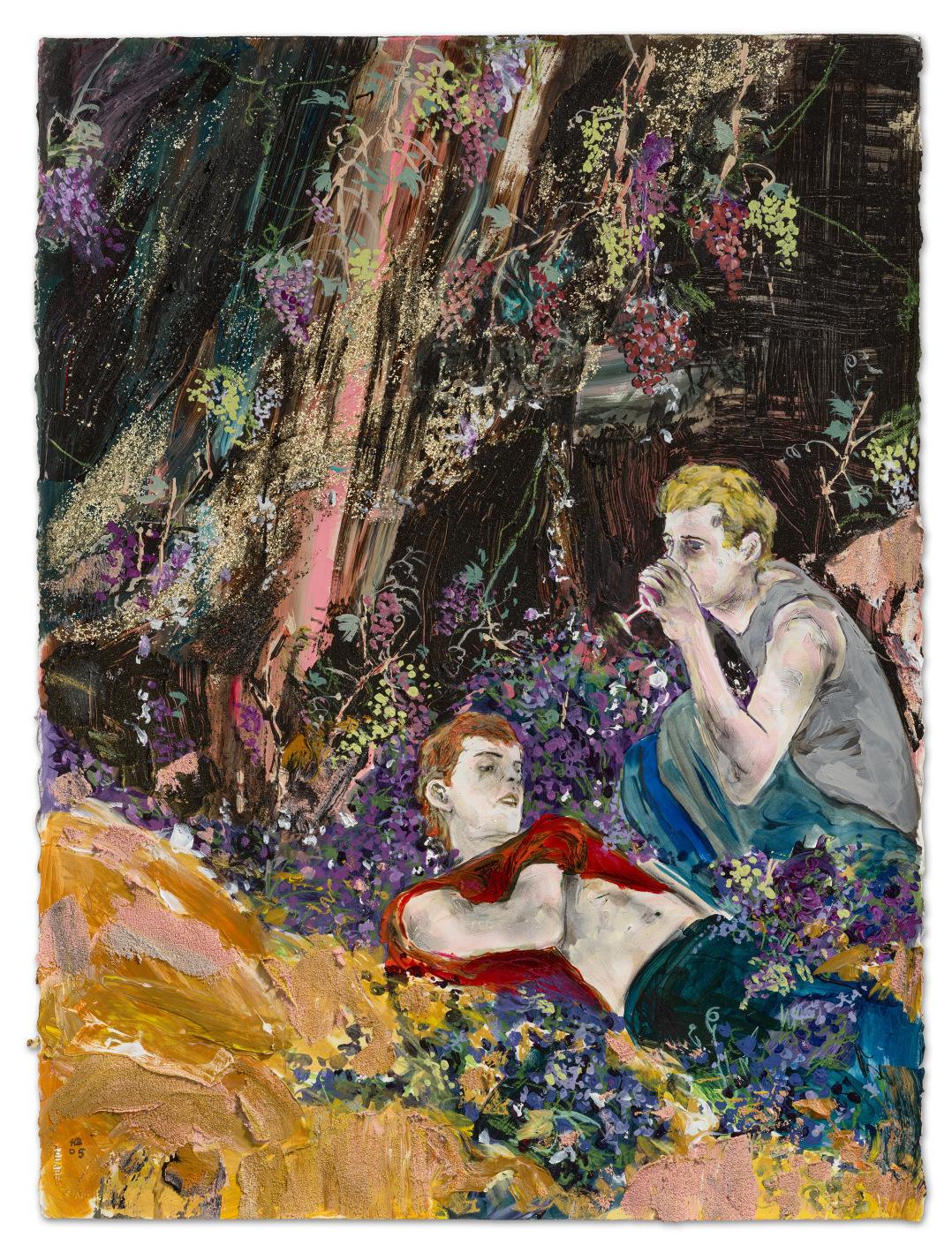

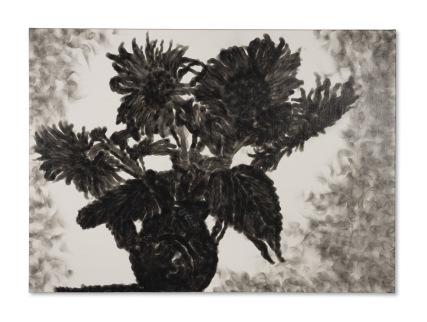

HERNAN BAS (B. 1978) Well Aged

signed with the artist's initials and dated 'HB 05' (lower left) oil, acrylic, gouache, charcoal, sand and glitter on paper

30º x 22¬in. (76.8 x 57.5cm.)

Executed in 2005

£40,000-60,000

PROVENANCE: Victoria Miro Gallery, London. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 2005.

EXHIBITED: London, Victoria Miro Gallery, Hernan Bas: In The Low Light, 2005. Frankfurt, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Ideal Worlds - New Romanticism in Contemporary Art, 2005, p. 119, no. 1 (illustrated in colour, p. 111).

JOHN SINGER SARGENT

Simplon Pass: Reading, circa 1911

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Digital image: © 2025 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All rights reserved. / Bridgeman Images.

Two willowy adolescents recline amid a sylvan idyll in Hernan Bas’s Well Aged (2005). The forest floor is strewn with lavender and periwinkle blossoms, and creeping grapevines cling to the tree trunks’ ridges and furrows, bursting into fantastic abstract daubs of chartreuse, crimson, magenta, and lilac fruit. Drunk on the heady scent of ripe flora and wine sipped from a thinstemmed glass, the couple lie in blissful oblivion. Bas’s celebrated cast of lithe and androgynous young men are typically depicted amid dreamy vignettes of abundant nature. Extending into the twenty-first century the traditional art-historical motif of the figure in a landscape—from the awe-inspiring Romantic vistas of Caspar David Friedrich to the fêtes galantes of Jean-Antoine Watteau—Bas captures his subjects in scenes of tender emotional poignancy and homoerotic encounter. Acquired by Ole Faarup the year it was painted and held in his collection for two decades, Well Aged dates to the artist’s celebrated breakthrough period, following his inclusion in the Whitney Biennial a year prior.

Born in Miami in 1978, Bas spent his earliest years on a remote farm in Ocala, northern Florida. The surrounding national forest looms large in his memories of this time, a wild and expansive landscape of longleaf and sand pines which soar skyward from porous sandhills, spreading their canopies across hundreds of springs, lakes and ponds. ‘I think that overwhelming fear and fascination with the unknown, with what the forests “held”, is embedded in a lot of my work,’ he explains (H. Bas quoted in K. Tylevich, ‘Hernan Bas: The Story at the Intermission’, Elephant Magazine, Spring 2014). In Well Aged, Bas reimagines this evocative landscape overgrown with a profusion of wild vines, trimmed with jewel-toned grapes. His ornate depictions of nature draw upon the late nineteenthcentury Decadent movement, exemplified in the novels of Joris-Karl Huysmans and Oscar Wilde. In one scene from the latter’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, Wilde’s titular protagonist is encountered ‘burying his face in the great cool lilac-blossoms, feverishly drinking in their perfume as if it had been wine’ (O. Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, London 1891, p. 30). In Well Aged, fruit mingles with the forest’s floral carpet and Bas’s waifish subjects ease into a similar, trance-like languor.

‘I find painting to be a way of channelling magic. You can get lost in the paint’

Hernan Bas

ODILON REDON

Ophelia among the flowers, circa 1905-1908

The National Gallery, London.

Digital image: The National Gallery, London/Scala, Florence.

MICHELANGELO MERISI DA CARAVAGGIO

Bacchus, circa 1598

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Digital image: Bridgeman Images.

An admirer of the Symbolist canvases of Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, Bas is renowned for his alluring and tactile painted surfaces. In the present work the figures’ forms are finely modelled with charcoal and luminous, delicate washes of pale pink and white paint. Around them, oil paint, acrylic, and gouache is scraped, stippled, flecked and daubed. Bas lays down the ochre-coloured earth in a gritty mixture of sand and pigment, applied in crisp encrustations with a palette knife. Flurries of impasto suggest laden vines whose ripe bunches droop towards the forest floor, and glitter forms crystalline constellations, falling like shafts of sunlight through the overgrowth. The picture plane is characterised by a sense of frenzied excess, as though at any moment the illusion will give way. ‘Paintings that I consider to be successful are always on the verge of falling apart,’ suggests Bas. ‘To me, that’s the fun of it—the imminent collapse’ (H. Bas quoted in S. Margolis-Pineo, ‘Against Nature: An Interview with Hernan Bas,’ Art21 Magazine, December 2011).

Captured amid lavish natural scenery conjured by florid, gestural brushwork, Bas’s ethereal youths evoke Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, whose name is given to festivals of uninhibited and ecstatic revelry. Within the artist’s critical exploration of same-sex love, the allusion to Bacchus in Well Aged becomes a symbol of erotic and social freedom. At the time the work was painted, Bas was thinking about the ambiguities of morality and conceptualising the possibility of ‘hell’ as a place of freedom and abandon, in opposition to the stifling and puritanical nature of ‘heaven’. In Well Aged, Bas draws the viewer into one such dreamlike realm, in which nature, youth and love are suspended in perpetual bloom.

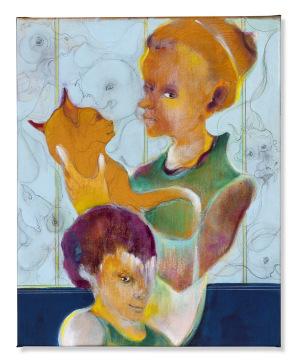

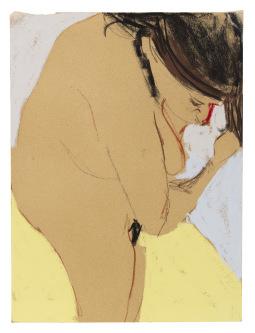

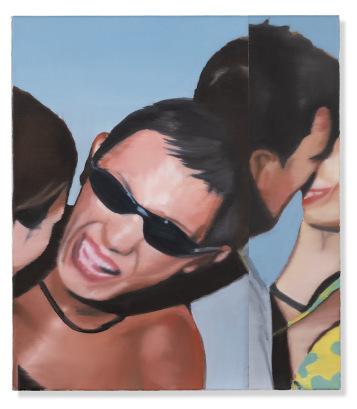

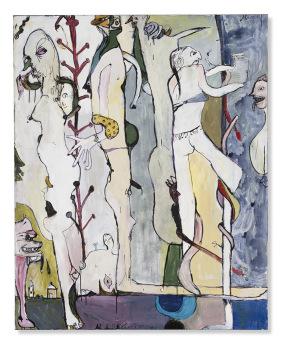

GUGLIELMO CASTELLI (B. 1987)

The Discreet Force of Sadness

signed, titled and dated ‘Guglielmo Castelli 2019 THE DISCREET FORCE OF SADNESS’ (on the reverse) oil on canvas

39¡ x 31Ωin. (100 x 80.1cm.)

Painted in 2019

£20,000-30,000

PROVENANCE:

Francesca Antonini Arte Contemporanea, Rome. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup.

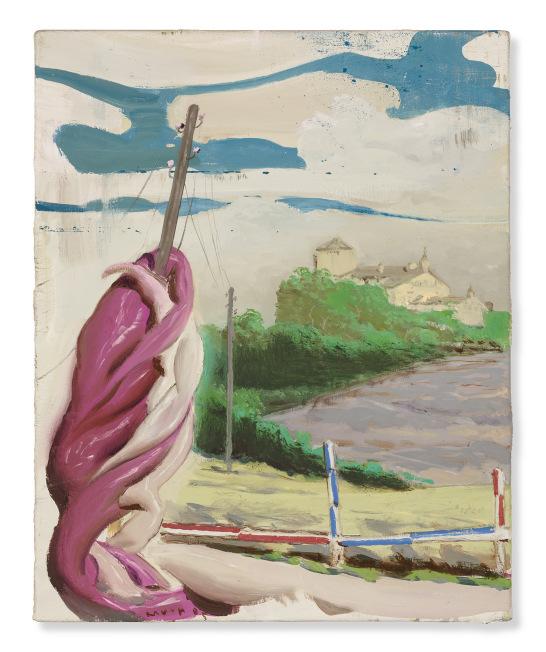

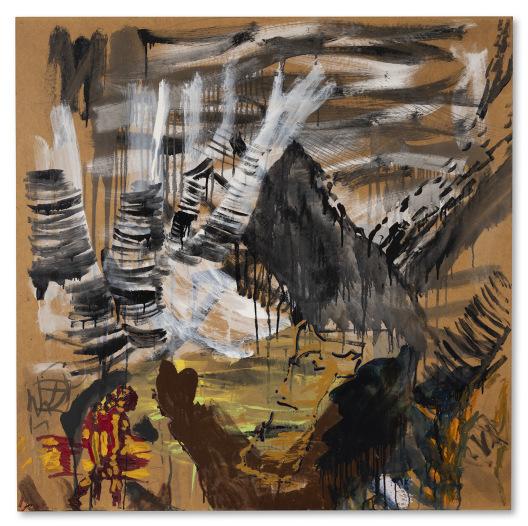

DANIEL RICHTER (B. 1962)

Mappez

signed twice, titled and dated three times ‘95 D. Richter 95/96 Daniel Richter 'Mappez'’ (on the reverse) oil on canvas

47¡ x 40ºin. (120.2 x 100.2cm.)

Painted in 1995-1996

£50,000-70,000

PROVENANCE:

Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup.

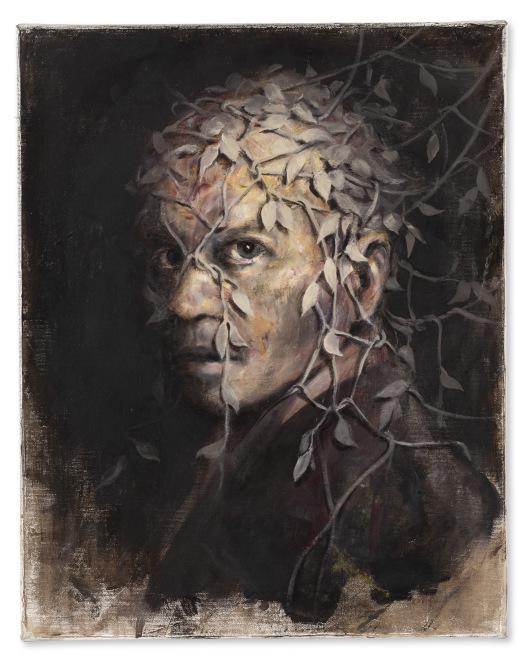

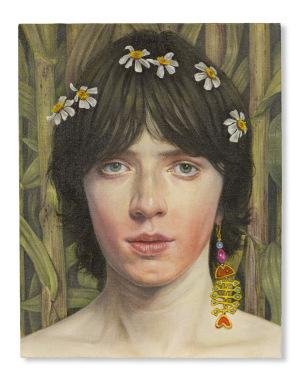

EWA JUSZKIEWICZ (B. 1984)

Untitled

signed and dated ‘Ewa Juszkiewicz 2014’ (on the reverse) oil on canvas

19¬ x 15¬in. (49.7 x 39.7cm.)

Painted in 2014

£80,000-120,000

PROVENANCE:

lokal_30, Warsaw.

HERNAN BAS (B. 1978)

Knife Passage (Mason)

signed with the artist’s initials and dated ‘HB 07’ (lower right); signed with the artist’s initials, titled and dated ‘Knife Passage (Mason) HB 07’ (on the stretcher) oil and metallic paint on linen

14 x 11in. (35.5 x 27.7cm.)

Executed in 2007

£30,000-50,000

PROVENANCE:

Victoria Miro Gallery, London. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 2007.

WILHELM SASNAL (B. 1972)

Mickiewicz

signed and dated ‘WILHELM SASNAL 1999’ (on the reverse) oil on canvas

15√ x 15√in. (40.2 x 40.2cm.)

Painted in 1999

£10,000-15,000

PROVENANCE:

Galleria Laura Pecci, Milan. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup.

NEO RAUCH (B. 1960)

Studio

signed and dated ‘RAUCH 99’ (lower right)

oil and gouache on paper

40¿ x 49¡in. (102 x 125.5cm.)

Executed in 1999

£70,000-100,000

PROVENANCE:

Galerie EIGEN + ART, Berlin. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 1999.

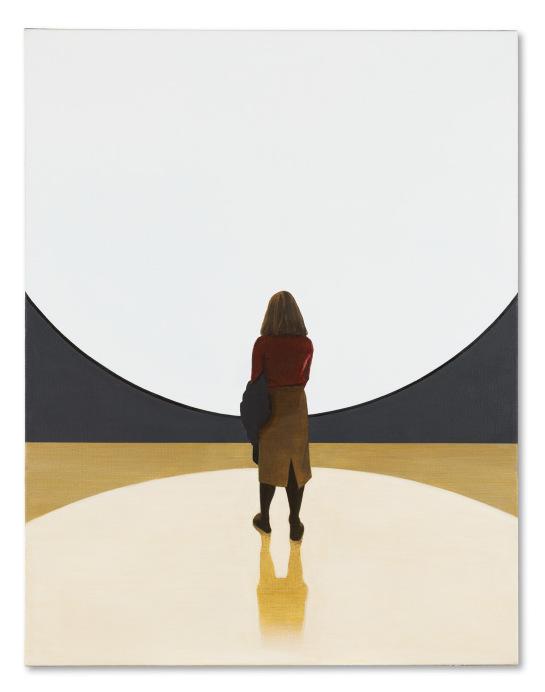

TIM EITEL (B. 1971)

Halbkreis

(Semi Circle)

signed, titled and dated ‘EITEL 2002 “Halbkreis”’ (on the reverse)

oil on canvas

35¡ x 27Ωin. (90 x 70cm.)

Painted in 2002

£15,000-20,000

PROVENANCE: Galerie LIGA, Berlin.

Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup.

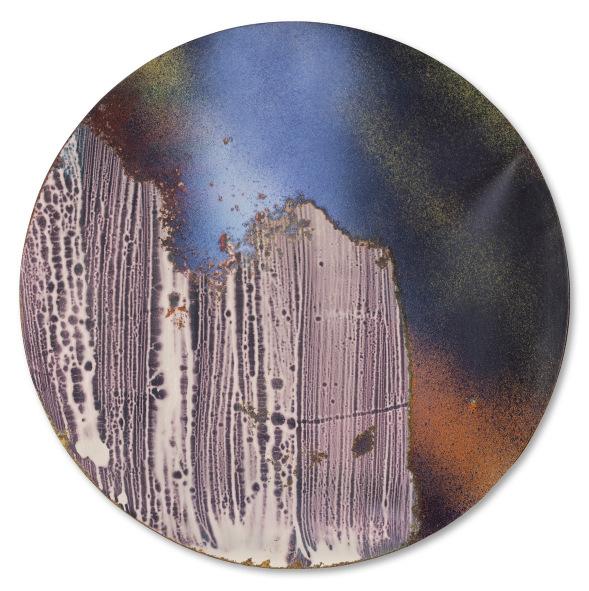

KATHARINA GROSSE (B. 1961)

Untitled

signed and dated twice ‘Katharina Grosse 2008’ (on the reverse) acrylic and soil on canvas diameter: 35¡in. (90cm.)

Executed in 2008

£30,000-50,000

PROVENANCE: Barbara Gross Galerie, Munich. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 2010.

NEO RAUCH (B. 1960) Schlinger

signed and dated 'Rauch 05' (lower left) oil on canvas

19æ x 15æin. (50 x 40cm.)

Painted in 2005

£40,000-60,000

PROVENANCE: Galerie EIGEN + ART, Berlin. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup.

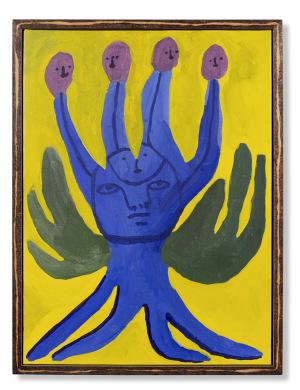

SONJA FERLOV MANCOBA (1911-1984)

Maske (Mask)

incised with the artist's initials and number ‘SFM 1/6’ (lower edge) bronze

8¬ x 9√ x 4æin. (22 x 25 x 12.2cm.)

Executed in 1984, this work is number one from an edition of six

£5,000-7,000

PROVENANCE:

Veksølund, Copenhagen. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup.

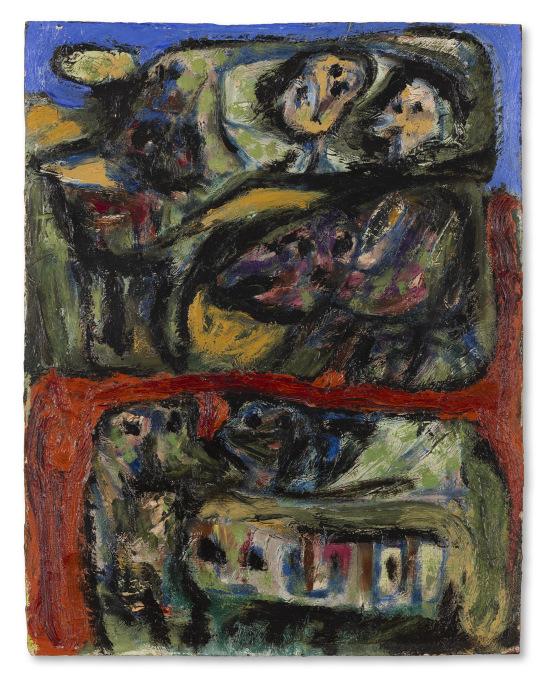

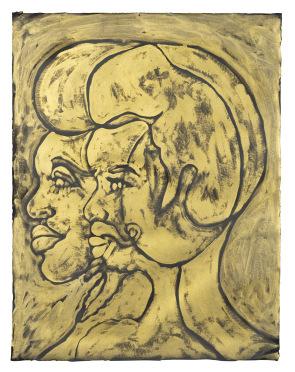

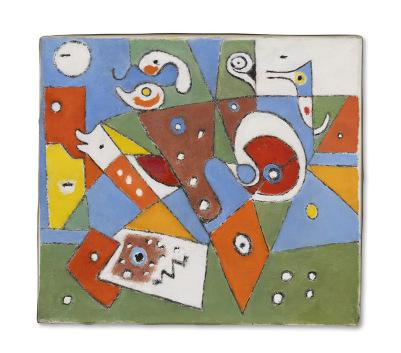

ASGER JORN (1914-1973)

Spaltet verden (Split World)

signed and dated ‘Jorn 1952-53.’ (on the reverse) oil on Masonite

16¡ x 12√in. (41.7 x 32.6cm.)

Painted in 1952-1953

£25,000-35,000

PROVENANCE:

Galerie Jerome, Copenhagen.

Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup.

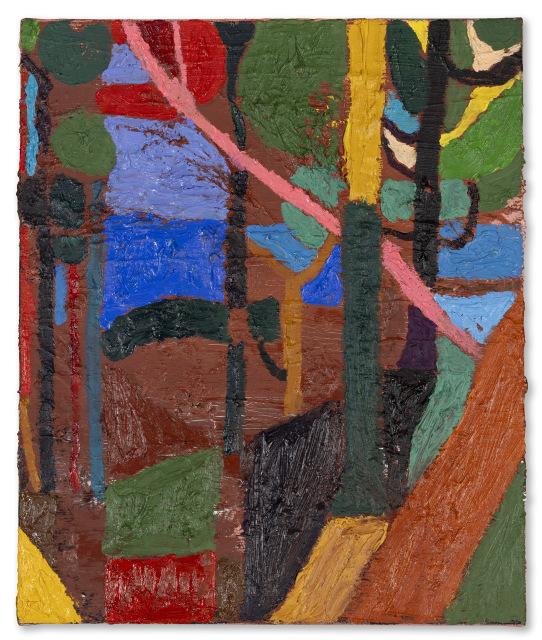

PER KIRKEBY (1938-2018)

Skovsøen (The Forest Lake)

signed, titled and dated 'Per Kirkeby 1970 Skovsøen' (on the reverse) oil, acrylic and graphite on Masonite

48¿ x 48¿in. (122.3 x 122.3cm.)

Executed in 1970

£35,000-55,000

PROVENANCE:

Acquired directly from the artist by Ole Faarup.

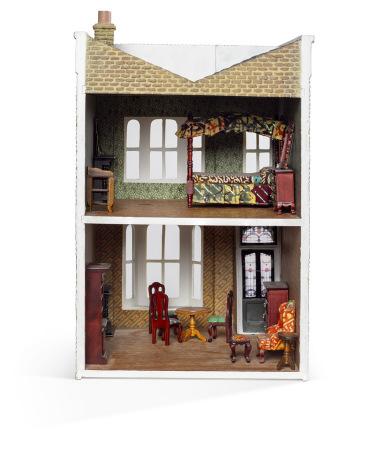

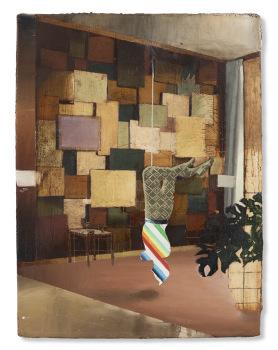

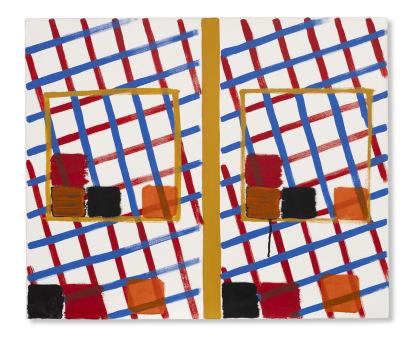

MATTHIAS WEISCHER (B. 1973)

o.T. 9

each: signed, consecutively numbered and dated ‘M.WEISCHER 03

PART I-V’ (on the reverse)

oil on five joined canvases

55¡ x 52in. (140.8 x 132.1cm.)

Executed in 2003

£15,000-20,000

PROVENANCE:

Anthony Wilkinson Gallery, London.

Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup.

TAL R (B. 1967)

Walk towards Hare Hill

signed ‘Tal R’ (on the overlap); signed with the artist’s initials ‘T.R’ (on the stretcher)

oil on canvas

23æ x 19æin. (60.2 x 50.2cm.)

Painted in 2013

£5,000-7,000

PROVENANCE:

Victoria Miro, London.

Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 2014.

GRAYSON PERRY (B. 1960)

Scorched Earth

stamped with the artist's monogram (lower edge) glazed earthenware

13 x 9 x 9in. (33 x 23 x 23cm.)

Executed in 2003

£30,000-50,000

PROVENANCE: Victoria Miro Gallery, London.

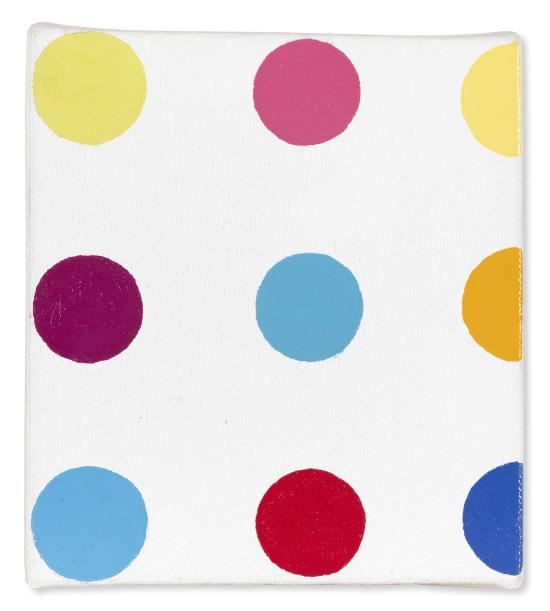

DAMIEN HIRST (B. 1965) N-t-Boc-I-Alanine

signed twice 'Damien Hirst D Hirst' (on the overlap)

household gloss on canvas

5¿ x 4Ωin. (13 x 11.5cm.) (1 inch spot)

Executed in 1995

£20,000-30,000

PROVENANCE: White Cube.

Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 1997.

CHRIS OFILI (B. 1968)

Scatology 1

signed, signed with the artist's initials, titled and dated ‘(Chris Ofili)

SCATOLOGY 1 (Feb 1993) CO’ (on the stretcher); signed and signed with the artist's initials twice ‘CO OFILI CO’ (on the reverse) oil and ink on canvas

25º x 21ºin. (64 x 54cm.)

Executed in 1993

£50,000-70,000

PROVENANCE: Anthony Wilkinson Fine Art, London. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 1995.

CHRIS OFILI (B. 1968)

Genuflect

incised with the artist's initials and number 'CO 1/7' (lower edge) bronze

23º x 14¬ x 13in. (59 x 37 x 33cm.)

Executed in 2006, this work is number one from an edition of seven plus one artist's proof

£15,000-20,000

PROVENANCE:

David Zwirner, New York.

Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup.

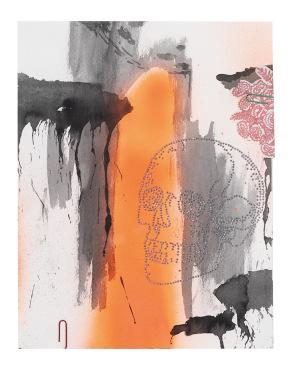

JONAS BURGERT (B. 1969)

bleibt

signed, titled and dated ‘-bleibt- 2015 J Burgert’ (on the reverse) oil on canvas

19√ x 15æin. (50.5 x 40cm.)

Painted in 2015

£15,000-20,000

PROVENANCE:

Produzentengalerie Hamburg, Hamburg.

Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup.

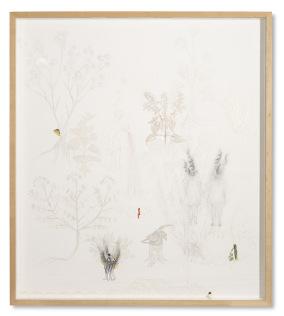

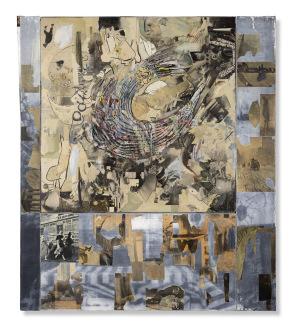

PASCALE MARTHINE TAYOU (B. 1966) Coffenerie

signed, signed with the artist's initials, titled, inscribed and dated ‘Coffinerie [sic]

Pascale PMT@ 2015’ (on the reverse) pastel, graphite, fabric, plastic and glitter on found paper collage, laid on board 56æ x 76æin. (144 x 195cm.)

Executed in 2015

£20,000-30,000

PROVENANCE:

Galleria Continua, Paris. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 2015.

SONIA GOMES (B. 1948)

Lugar, Aconchego

signed, titled, inscribed and dated 'objeto 2013 Sonia Gomes LUGAR, Aconchego.' (on the reverse)

fabric, laces, zipper, found ceramic, stitching, bindings and wire

22¬ x 12º x 6æin. (57.5 x 31 x 17cm.)

Executed in 2013

£10,000-15,000

PROVENANCE:

Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 2013.

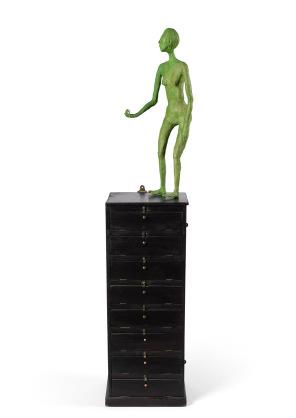

KIKI SMITH (B. 1954)

Verge

stamped with the artist’s initials and date ‘K S 2016’ (to the underside) bronze

22æ x 13Ω x 7¿in. (57.8 x 34.3 x 18cm.)

Executed in 2016, this work is unique

£6,000-8,000

PROVENANCE:

Galerie Lelong & Co, Paris. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 2018.

ALICJA KWADE (B. 1979)

Deer Desire

bronze, rock crystal and marble

68√ x 12º x 12ºin. (175 x 31 x 31cm.)

Executed in 2018

£10,000-15,000

PROVENANCE: KÖNIG GALERIE, Berlin.

Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 2019.

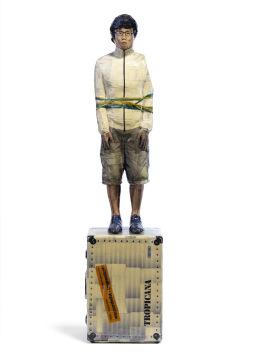

TONY MATELLI (B. 1971)

Shallow Grave

silicon, foam, epoxy, yak hair, paint and cardboard box, in three parts

36º x 19º x 16¿in. (92 x 49 x 41cm.)

Executed in 2002

£8,000-12,000

PROVENANCE:

Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 2004.

JEPPE HEIN (B. 1974)

One Wish for You (dark may green)

glass fibre reinforced plastic, chrome lacquer (dark may green), magnet and string (white smoke)

balloon: 16¿ x 10º x 10ºin. (41 x 26 x 26cm.)

Executed in 2020, this work is number two from an edition of three plus two artist's proofs

£8,000-12,000

PROVENANCE:

Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup.

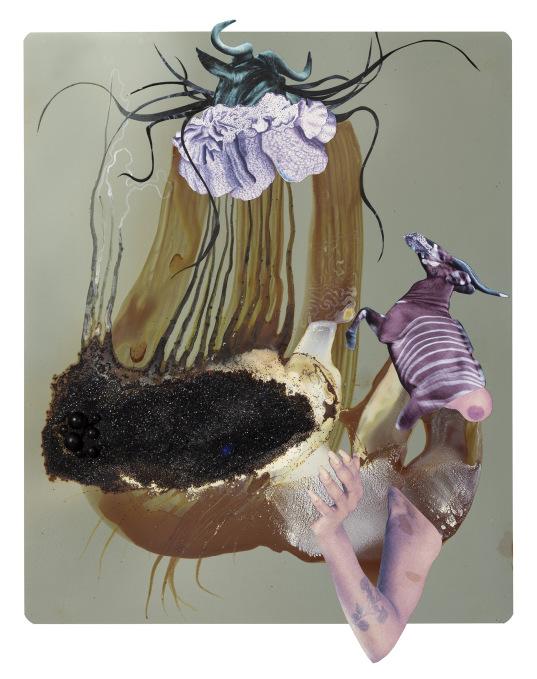

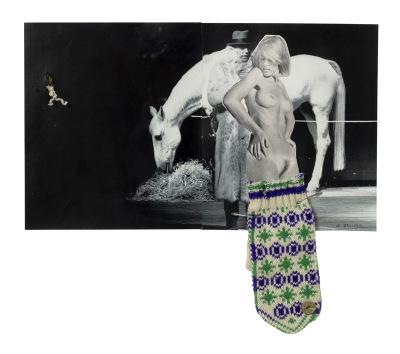

WANGECHI MUTU (B. 1972) Drowning Nymph III

signed with the artist’s initials and dated ‘W.M. 07’ (lower right) ink, acrylic, plastic pearls, plant material, glitter and printed paper collage on X-ray paper 18º x 14in. (46.5 x 35.5cm.)

Executed in 2007

£12,000-18,000

PROVENANCE:

Victoria Miro Gallery, London. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup.

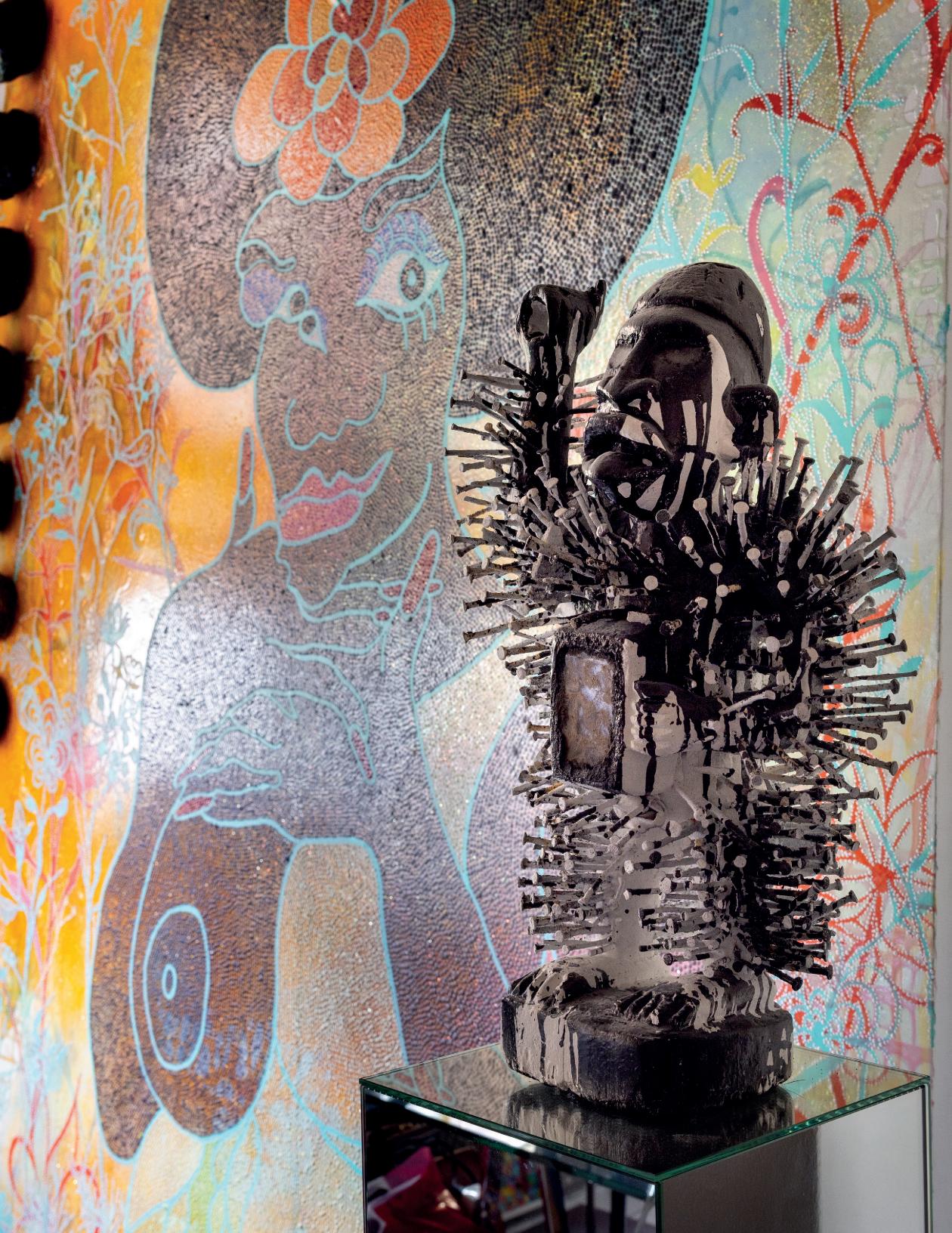

KENDELL GEERS (B. 1968)

Mutus Liber (Fetish) 68

signed ‘Kendell Geers’ (on the underside) oil, nails, glass, fabric and mud on found wooden object on mirror plinth overall: 65¿ x 9 x 9in. (165.5 x 23 x 23cm.)

Executed in 2016

£4,000-6,000

PROVENANCE:

ADN Galerie, Barcelona. Acquired from the above by Ole Faarup in 2016.

ANDREAS ERIKSSON (B. 1975)

Promenad VIII

signed, titled and dated ‘Andreas Eriksson PROMENAD VIII 2021’ (on the reverse) oil and tempera on panel 19æ x 15æin. (50 x 40cm.)

Executed in 2021

£4,000-6,000

TAL R (B. 1967)

Walk Towards Hare Hill signed ‘Tal R’ (on a label affixed to the reverse) oil on canvas

17√ x 14in. (45.4 x 35.4cm.)

Painted in 2013

£4,000-6,000

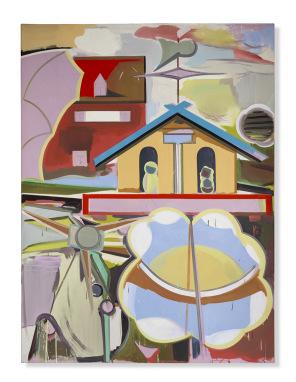

THOMAS SCHEIBITZ (B. 1968)

Garten

signed, titled and dated ‘Garten Scheibitz 98’ (on the reverse) oil and graphite on canvas 78æ x 59in. (200 x 150cm.)

Executed in 1998

£6,000-8,000

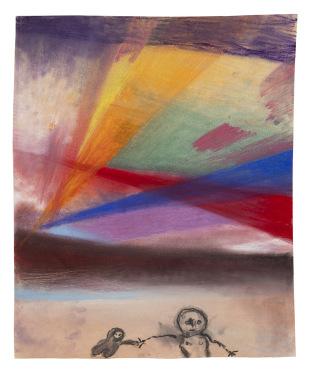

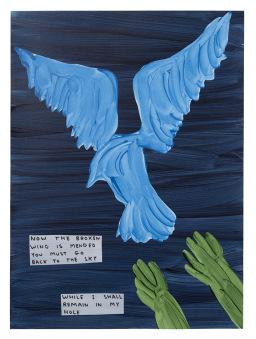

FRIEDRICH KUNATH (B. 1974)

Old Love

titled ‘OLD LOVE’ (lower left); signed and dated ‘Friedrich Kunath 2018’ (on the reverse) oil on canvas

30 x 241in. (76.2 x 61.1cm.)

Painted in 2018

£10,000-15,000

CONNY MAIER (B. 1987)

Kopfbedeckung Grüne (Study case 5)

(Headgear Green (Study case 5))

signed with the artist’s initials ‘CM’ (lower left); signed with the artist’s initials, titled and dated ‘CM’ 21 (study case 5) Kopfbedeckung Grüne’ (on the reverse)

oil on canvas

15√ x 15√in. (40.3 x 40.3cm.)

Painted in 2021

£3,000-5,000

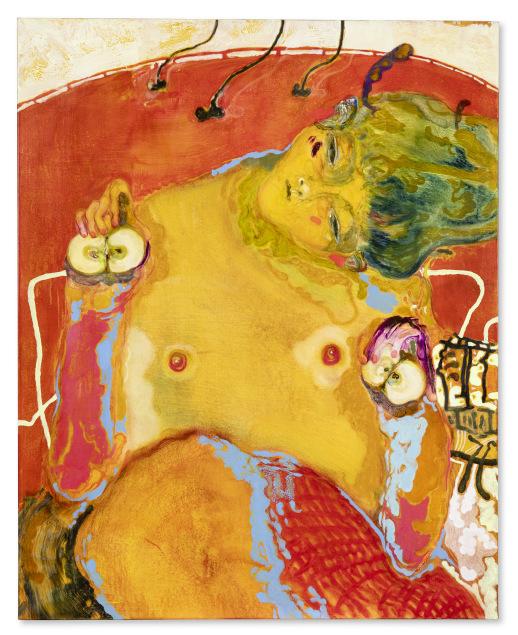

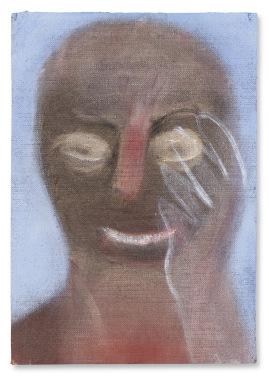

MIRIAM CAHN (B. 1949)

lachenmüssen 15. + 22.12.2017 + 7.1.2018 (have to laugh 15. + 22.12.2017 + 7.1.2018)

signed with the artist's initial, titled and dated ‘lachenmüssen M 15 + 22.12.17 + 7.1.18’ (on the reverse)

oil on canvas paper laid on board

11æ x 8ºin. (30 x 21cm.)

Executed in 2017-2018

£6,000-8,000

DANIEL RICHTER (B. 1962)

Untitled

signed and dated ‘D. Richter 2008’ (on the reverse) oil and metallic paint on canvas

19æ x 15√in. (50.3 x 40.3cm.)

Painted in 2008

£15,000-20,000

GUGLIELMO CASTELLI (B. 1987)

I corpi senza vacanza (Bodies without a holiday)

signed, stamped with the artist's signature, titled and dated ‘GUGLIELMO CASTELLI Guglielmo Castelli, 2019, I corpi senza vacanza’ (on the reverse) oil on canvas

15æ x 11æin. (40 x 30cm.)

Painted in 2019

£8,000-12,000

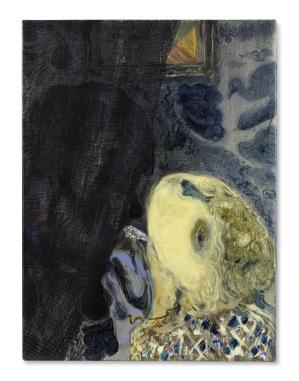

MIRIAM CAHN (B. 1949)

flüchtenmüssen 01.02.2011 (have to flee 01.02.2011)

signed with the artist’s initial, titled and dated ‘flüchtenmüssen M 1-2-11’ (on the reverse)

pastel on paper

29√ x 24æin. (76 x 62cm.)

Executed in 2011

£5,000-7,000

ALICJA

KWADE (B. 1979)

My candle burns at both ends

painted bronze on Bianco Dolomite base

overall: 2¬ x 4√ x 4√in. (6.8 x 12.4 x 12.4cm.)

Executed in 2020, this work is from an edition of thirty, each unique

£3,000-5,000

KATHARINA GROSSE (B. 1961)

Untitled

signed and dated ‘K Grosse 2010’ (on the underside)

acrylic on cast aluminium

13√ x 14¬ x 24in. (35.3 x 37 x 61cm.)

Executed in 2010

£15,000-20,000

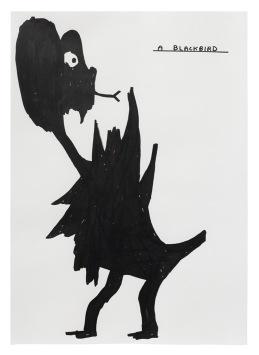

GERT

& UWE TOBIAS (B. 1973)

Untitled

signed and dated ‘Gert Uwe Tobias 2015’ (on the reverse)