“The idea of subversion is a powerful subject.”

ED RUSCHA

“The idea of subversion is a powerful subject.”

ED RUSCHA

MARK ROZZO is the author of Everybody Thought We Were Crazy: Dennis Hopper, Brooke Hayward, and 1960s Los Angeles, which has been named by The Los Angeles Times as one of the 50 best Hollywood books of all time. He is an editor at large at Air Mail, a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, and has written for The Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, The New York Times, Esquire, Vogue, The Wall Street Journal, The Oxford American, The Washington Post and many other publications. He teaches nonfiction writing at Columbia.

MAX CARTER is Vice Chairman of 20th and 21st Century Art at Christie’s.

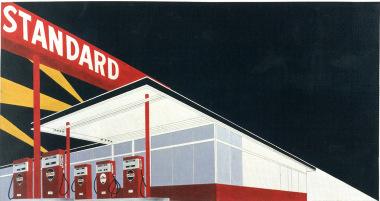

Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half

signed, dated and titled ‘”STANDARD STATION, 10¢ WESTERN BEING TORN IN HALF” 1964 Edward J. Ruscha’ (on the stretcher) oil on canvas

65 x 121 ½ in. (165.1 x 308.6 cm.)

Painted in 1964

Estimate on Request

Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles.

Mr. and Mrs. Donald Factor, Los Angeles.

James J. Meeker, Fort Worth (acquired from the above, December 1970).

Acquired by the exchange of Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas with the above by the present owner, November 1976.

EXHIBITED

Los Angeles, Ferus Gallery, Edward Ruscha, October-November 1964.

IX Fundação Bienal de São Paulo and Waltham, Brandeis University, Rose Art Museum, Environment USA: 1957-1967, September 1967-March 1968 (illustrated, pl. G).

Fort Worth Art Center Museum, Contemporary American Art, Los Angeles, from a Fort Worth-Dallas Collection, January-February 1972, no. 66.

Fort Worth Art Museum, Twentieth Century Art From Fort Worth Dallas Collections, September-October 1974 (illustrated; dated 1963 and titled Standard Station). San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institute, National Collection of Fine Arts, Painting and Sculpture in California: The Modern Era, September 1976-September 1977, no. 221 (illustrated, p. 158; dated 1963 and titled Standard Station with 10¢ Western).

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (on extended loan).

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Masterworks from Fort Worth Collections: A Centennial Exhibition, April-June 1992, p. 69 (illustrated).

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Ed Ruscha, July-September 2001, p. 165 (illustrated in color, pp. 34-35).

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Ed Ruscha: Road Tested, January-April 2011, p. 114, no. 20 (illustrated in color, pp. 60-61).

New York, The Museum of Modern Art and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Ed Ruscha: Now Then, September 2023-October 2024, pp. 14, 102, 154-155, 274 and 316 (illustrated in color, pp. 104-105).

N. Marmer, “Reviews: Edward Ruscha,” in Artforum vol. 3, no. 3, December 1964, p. 12. “Artists: Assemblage at the Frontier, Pop Goes the West Coast” in Time, vol. 86, no. 16, 15 October 1965 (illustrated, p. 108).

“Sculptured House for a Collecting Family,”in House Beautiful, vol. 109, no. 4, April 1967 (illustrated in color in situ in a private Beverly Hills residence, p. 154; titled Standard Oil).

W. Wilson, “Patrons of Pop,” in Los Angeles Times West Magazine, 7 December 1969 (illustrated, p. 19).

Paintings, Drawings and Other Works by Edward Ruscha, exh. cat., Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, 1976, p. 6 (titled Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas (Day)).

L. Wenger, “California Visions,” in New West, vol. 1, no. 13, 11 October 1976, p. 136.

O. Friedrich, “American Renewal: To Reform the System,” in Time, vol. 117, no. 8, 23 February 1981, p. 39 (illustrated, p. 39).

K. Larson, “Billboards Against the Sunset,” in New York Magazine, 26 July 1982, p. 60.

The Works of Edward Ruscha, exh. cat., San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1982, p. 6 (illustrated, p. 31).

John Baldessari exh. cat., Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1990, p. 29 (illustrated in color, p. 28).

A. Skolnick, ed., Paintings of California New York, 1993, p. 23 (illustrated).

Edward Ruscha: Romance with Liquids, Paintings 1966-1969, exh. cat., Gagosian Gallery, New York, 1993 (illustrated, p. 100).

“Driven to Inspiration,” in Los Angeles Times, 28 March 1993 (illustrated, p. E2; dated 1963 and titled Standard Station with 10¢ Western).

N. Moure, California Art: 450 Years of Painting and Other Media, Glendale, 1998, p. 435, (illustrated in color, p. 432, fig. 32-2).

C. Meeks, “Honorary Degree to Artist Ed Ruscha,” in Cal Arts Current, vol. 11, no. 3, June 1999 (illustrated).

A. Schwartz, ed., Leave Any Information At The Signal: Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages Cambridge, 2002, pp. 25 and 223.

R. D. Marshall, Ed Ruscha, London, 2003, pp. 10 and 211 (detail illustrated in color, pp. 4-5; illustrated in color, pp. 38-39).

R. Dean and P. Poncy, eds., Edward Ruscha: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings: 1958-1970 New York, 2003, vol. 1 (illustrated in color, pp. 121-122, no. P1964.04; preparatory sketch illustrated in color, p. 124).

A. Schwartz, Ed Ruscha’s Los Angeles, Cambridge, 2011, p. 100.

C. Tutwiler, Ed Ruscha, Vik Muniz and the Car Culture of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, 2011 (illustrated in color, p. 22).

Ed Ruscha and the Great American West, exh. cat., Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, 2016, p. 14 (illustrated in color, p. 15, fig. 5).

Once Upon a Time…The Western: A New Frontier in Art and Film, exh. cat., Denver Art Museum, 2017, p. 246 (illustrated).

L. Bradnock, “Whatever Happened to the Frontier? Performing Provincialism in Post-War Los Angeles,” in Tate Papers, www.tate.org.uk, no. 32, Autumn 2019 (illustrated in color).

C. Voon, “MoMA to stage major Ed Ruscha retrospective, spanning his text paintings to the infamous Chocolate Room” in The Art Newspaper, www.theartnewspaper.com, 19 October 2022 (illustrated in color).

“‘Ed Ruscha / Now Then,” in Apollo Magazine, www.apollo-magazine.com, 31 August 2023, (illustrated in color).

P. Plagens, “‘Ed Ruscha Now Then’ Review: Iconic Meets Ironic” in Wall Street Journal, 11 September 2023 (illustrated in color).

V. Esposito, “Ed Ruscha: Moma offers pop artist’s biggest exhibition to date,” in The Guardian, www.theguardian.com, 15 September 2023, (illustrated in color).

A. Budick, “Ed Ruscha, MoMA review – from explosive breakthrough to fizzling despair” in Financial Times, www.ft.com, 20 September 2023 (illustrated in color).

H. Halle, “Ed Ruscha’s Poetry of the American Experience” in Art & Object, www.artandobject.com, 24 October 2023 (illustrated in color).

H. Halle, “An Ed Ruscha Retrospective at MoMA Presents a Master of Wordplay and Trompe L’Oeil” in ARTnews, www.artnews.com, November 2023 (illustrated in color in situ at The Museum of Modern Art, New York).

P. Kennicott, “Is Ed Ruscha secretly painting American history? Or recycling memes?” in The Washington Post, www.washingtonpost.com 3 November 2023 (illustrated in color).

S. Tallman, “Ed Ruscha Bigger than Actual Size” in New York Review of Books, www.nybooks.com, 23 November 2023 (illustrated in color).

J. Quick, “The Pull of Design: Notes on the Exhibition Ed Ruscha / Now Then,” in Yale University Press, www.yalebooks.yale.edu, 28 November 2023.

“Ed Ruscha Has Always Seen America Like No One Else: Peer Through His Eyes in a Sprawling MoMA Exhibition,” in Artnet News, www.news.artnet.com, 23 December 2023 (illustrated in color).

D. Carrier, “Ed Ruscha,” in Border Crossings, www.bordercrossingsmag.com, January 2024 (illustrated in color).

T. de Monchaux and M. Krotov, “This, This, This and This: Ed Ruscha and his buildings,” in n+1 Magazine www.nplusonemag.com 22 January 2024.

C. Knight, “Review: Ed Ruscha show wowed in New York: Why it’s even better in L.A.,” in Los Angeles Times, www.latimes.com, 7 April 2024 (illustrated in color).

J. Griffin, “Way Out West,” in Apollo Magazine, vol. CC, no. 732, July-August 2024 (illustrated in color, p. 9).

20 3/8 x 39 in.

P1966.01

Mark Rozzo

In August of 1956, the 18-year-old Ed Ruscha set out for Los Angeles from his hometown of Oklahoma City in a 1950 Ford. His copilot was his high-school best friend, a precocious teenage musician named Mason Williams. Their 1,300-mile odyssey along Route 66 is a standard component of the Ruscha origin story, not to mention the cosmology of postwar American art. You could argue that what Warhol was to Campbell’s soup cans and Brillo boxes, Ruscha has been to highways—the allAmerican, high-speed built landscape of yammering signage and cheapo architecture. Roads, streets, freeways, the blowntire detritus on their shoulders, the endless sequence of gas stations that line them: Ruscha has been a visual bard of the world as seen through a windshield. As Adam D. Weinberg, the former director of the Whitney Museum, once put it, “No American artist has a more singular vision of the American landscape, especially the impassive iconography of the road, than Ruscha.” Or, as Ruscha himself said, “Everything you see on the street I’m influenced by.”

After arriving in Los Angeles, Williams would eventually find work as a writer for the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour and fame as the AM-radio hitmaker behind “Classical Gas.” (Ruscha created the artwork for Williams’s 1969 LP, Music.) For his part, Ruscha—a kid with a fixation on India ink who had once dreamed of becoming a comic-book artist—found a carcentric city that had, in his words, “the right kind of decadence

and lack of charm to make an artist.” Make him an artist it did, even if Ruscha, in contrarian fashion, has occasionally deflected this notion. “Being in Los Angeles,” he said in 1966, “has had little or no effect on my work.” Nevertheless, Ruscha grew to become L.A.’s artist laureate by near-universal acclamation. The city has remained his base of operations since the day he arrived 68 years ago.

[L.A.]’s got the right kind of decadence and lack of charm it takes to make an artist.

ED RUSCHA

I once asked Ruscha about that 1956 road trip that brought him west to study at the Chouinard Art Institute (later Cal Arts) and set him on a course to become one of America’s great artists. Were there any particular high points along the way? Ruscha replied, “Santa Rosa, New Mexico! What do they call that, the Fan-Belt Capital of the World?” He didn’t elaborate further.

It’s likely that the teenagers’ westward route brought them past another site that would prove decisive in Ruscha’s formation and early success. Just inside the Amarillo, Texas, city line, two and a half miles down the road from the moderne Triangle Motel and Café, and about 250 miles from Oklahoma City, the boys would have been banking their speed along Northeast Eighth Avenue, the path Route 66 took through the city. On their right, a Western-themed motel called the Silver Spur, with its eye-grabbing neon cowboy-boot sign. And then, a second later, a building barely a notch above nondescript: a jutting roof, perhaps draped with plastic pennants; a plain rectangular slab of signage protruding toward the road; five red fuel pumps. A gas station, not unlike thousands of others from coast to

Ruscha sent a courtesy copy to the Library of Congress, which returned it to the artist with a polite but curt letter, ostensibly rejecting the volume for its lack of informational or aesthetic value.

Ed Ruscha’s advertisement in the March 1964 issue of Artforum to promote Twentysix Gasoline Stations. Published in Artforum 2, no. 9, p. 55. © Ed Ruscha.

coast. Ruscha said that he and Williams probably spent more on gasoline than food on their journey to Los Angeles. Maybe they spent some of that money here, or maybe not. Maybe the gas station was closed, or under construction—or perhaps didn’t even exist in 1956. It’s a fun conjecture.

One way or another, about six years later, Ruscha was reversing the course, driving back home from Los Angeles along Route 66 to Oklahoma City to visit his family. This time he’d brought a camera. It’s easy to imagine how it might have unfolded: The gas station in northeast Amarillo caught his eye. It was on the left now. Ruscha stopped, photographed it from across the road, may or may not have gassed up, kept driving. He’d been doing this for much of the route, stockpiling images of service stations—the less interesting, the better. He would spin this aggressively boring visual documentation of aggressively boring architectural phenomena into an artist’s book with an aggressively boring name: Twentysix Gasoline Stations, published in 1963, available for mail order at three dollars a pop. Ruscha sent a courtesy copy to the Library of Congress, which returned it to the artist with a polite but curt letter, ostensibly rejecting the volume for its lack of informational or aesthetic value. Ruscha would then transform one of the 26 black-and-white photographs from the book—the one of the Standard station on Northeast Eighth Avenue (now East Amarillo Boulevard), in Amarillo—into what is arguably his best-known image as a fine artist.

Arriving in Los Angeles, Ruscha would have found at Chouinard an emergent Southern California art scene in microcosm. Robert Irwin, John Altoon, and Billy Al Bengston were among the instructors there, all destined to be Ruscha’s future friends and gallery mates. (Ruscha seemed to share a particular closeness with the Kansas-born Bengston, another heartlander.) Attending Chouinard during the late 1950s were Larry Bell, Ed Bereal, and Llyn Foulkes, along with Ruscha’s fellow Oklahomans Joe Goode, Jerry McMillan, and Patrick Blackwell. The young Okies eventually shared a “semi-detached Victorian house” and billed themselves the Students Five (the fifth being a poodle), getting up to an assortment of art-school japery. At Chouinard, Ruscha won plaudits for his participation in a poster contest sponsored by the Wool Board and edited and designed an alternative campus publication called Orb

Back home in Oklahoma City, his insurance-adjuster father, initially skeptical about the prospects of a career in fine art, was satisfied that his son was on a commercial-art path at an institution famous for its connections to the Disney studio. (In fact, Walt Disney was granted a doctorate in fine arts at Chouinard the spring before Ruscha arrived.) The late critic Dave Hickey referred to Ruscha—who was born in Omaha before the family moved to Oklahoma City when he was a toddler—as a “Child of Pop from the Cities of the Plain.” It’s an insightful thumbnail: Growing up, young Ed was besotted with Hollywood movies, the “race music” he heard on after-hours radio, and the comic strips, particularly Dick Tracy, that were featured in the copies of the Daily Oklahoman he delivered along his paper route and which he would emulate with ink and paper. When he was about 12 years old, a defining moment came in the

form of an encounter with the zany bandleader Spike Jones, in town to play a show with his City Slickers. Ruscha staked out the stage door and asked the bandleader to give him a task in exchange for admission. “Here’s a dollar,” Jones said. “Go get a dozen eggs.” The boy did as he was told, was granted entry, and was delighted when the City Slickers pelted each other with raw eggs onstage and the audience went nuts. Ruscha would later work such elements into his art: goofball humor, the element of surprise, and even eggs, whose yolks he would one day employ as pigment. There were early urges toward near-fanatical documentation, as when the boy daydreamed about creating a precise diorama of his entire paper route or accumulated commonplace items in matchboxes that he assiduously labeled: “TEETH I HAVE LOST,” “MONEY I HAVE FOUND.” His mother and siblings—an older sister and a younger brother—found it all hilarious.

Dave Hickey referred to Ruscha ... as a “Child of Pop from the Cities of the Plain.”

Ruscha’s work as an art student ran along two parallel tracks. On the fine-art side, there were canvases inspired by the likes of de Kooning and Kline. Abstract expressionism, after all, was ascendant. On the commercial side, the school hammered the elements of design into first-year students. These were intended to be applied to whatever art the student would ultimately pursue at Chouinard and beyond. (In Ruscha’s case, he certainly did apply them; in his future career, he would effectively harness design and commercial-art techniques to high-art ends.) Toward the end of his time at art school, these two strands in Ruscha’s work began to entwine. He was experimenting with splitting

canvases horizontally, with swashy Ab-Ex gestures on top and stately lettering below, as in the works Su (after his thengirlfriend Su Hall), Dublin, and Sweetwater. The words were often place names, known to Ruscha from road signs and maps, many of them encountered on a hitchhiking trip in the summer of 1954—east to Florida and back to Oklahoma. In particular, Sweetwater, from 1959, was a breakthrough. It met a tragic end. Another student, apparently hard up for canvas, painted over it. It can only be seen in black-and-white photographs. Another early Ruscha piece was lost when one of his teachers set fire to it in anger.

The words played as still lifes and they played as signs.

Ruscha has described Jasper Johns’s Target with Four Faces, which he found in a copy of Print magazine in 1957, as an “atomic bomb in my training.” His early word paintings are evidence of this impact, as Ruscha chose to work in a “premeditated” fashion—following a set plan—and depicting stuff from everyday life. It was proto-Pop. Graduating in 1960, Ruscha got a gig at an advertising firm, hated it, and quit. At some point, he made rent money by hand-lettering names on novelty denture holders called Ma and Pa Chopper Hoppers. In his own work, words came to take over the canvases: Boss, Ace, Gas, Smash, and, perhaps the best known, OOF, three dead-center block letters, sans serif, yellow on cobalt and Bellini blue. The words played as still lifes and they played as signs. The viewer’s mind oscillated between seeing the words as forms and reading them as language, a cognitive head-spinner. Still in his early twenties, Ruscha had found his groove: ingeniously deflecting words—the basic building blocks of the Information Age—from the work-for-hire dominion of commercial art into the topmost reaches of high art.

Ruscha had chosen Los Angeles over the art-world behemoth of New York mainly because he liked the sunshine, the relatively easy way of life, and the cheap rent. (He visited New York for the first time in 1961 and said he was “thrown back by the coldness of it.”) As an art town, L.A. had a certain underdog spirit.

As an art town, L.A. had a certain underdog spirit.

In 1956, the boosterish art critic of the Los Angeles Times, Arthur Millier, declared L.A. the second biggest art colony in the United States. This might have been true. During Ruscha’s student days, outside of Chouinard, the city was home to a colorful art-world fringe, which the curator Walter Hopps described as “the obstreperous, deadly serious underground of vanguard art hanging on in the middle fifties in Los Angeles.” It was the era of beatnik bohemia. There was the occult artist Cameron, who starred as the Scarlet Woman in Kenneth Anger’s hypnagogic underground movie Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, and the tremendously influential Wallace Berman, the assemblage artist and charismatic ringleader of an emerging avant garde that coalesced around his art journal Semina, a visual and literary grab bag that featured the latest from Ginsberg and Bukowski. Berman’s house on Crater Lane became a focal point of a new generation of artists and Hollywood hangers-on, including Dennis Hopper. “When you couldn’t get a joint anywhere else,” Hopper said, “you could always go to Wallace’s house and get a joint—so we hung out there.”

When it came to collecting, there were a few art-mad Hollywood moguls, such as William Goetz, of 20th Century Fox, who lined the walls of his house on Delfern Drive with Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works, including a Van Gogh self-portrait of dubious authenticity. The creepy actor and bon vivant Vincent Price took a more cutting-edge approach, filling his massive Spanish Mission house in Beverly Glen with

Diebenkorns and Stills, along with all order of meso-American artifacts. He was Hollywood’s most high-profile collector but his taste in contemporary art had ossified by the mid-50s. (Works from Price’s collection would form the basis of the Vincent Price Art Museum, in Monterey Park.) The storied Angeleno collectors Louise and Walter Arensberg, who had gotten the art bug at the Armory Show in 1913, welcomed visitors from around the world to their house on Hillside Avenue to view a profusion of Duchamps, Picassos, Matisses, and Brancusis. (The pioneering food writer M.F.K. Fisher was one; she found the experience “almost unbearably fatiguing.”) The city lost that trove to the Philadelphia Museum of Art six years before Ruscha arrived in Los Angeles. All in all, it was a mixed record.

On the gallery front, the establishment that would become synonymous with putting L.A. on the art-world map was Ferus, founded by Hopps and Ed Kienholz, an assembleur with a lumberjack’s mien, in 1957, a partnership that was famously cemented with a one-line contract scrawled on a hot-dog container. The Ferus Gallery opened shop at 736A North La Cienega Boulevard, amid the city’s gallery row. An early highlight was Berman’s June 1957 solo show, which had the distinction of being shut down by the L.A.P.D. vice squad. The following year, Kienholz sold his stake in Ferus to Irving Blum, a charming, natty operator with Cary Grant-worthy insouciance and an impermeable affability; he moved the gallery across La Cienega to smarter digs at number 723 and ran the place like an actual business. In time, Ferus would become the best-known gallery west of the Hudson River, and the focal point for so many of the student artists and teachers Ruscha knew at Chouinard, including himself. It was also in 1958 that L.A.’s novel tradition of Monday-night art walks began along La Cienega. Mixing art, commerce, and a party atmosphere, the art walks could be said to have anticipated such fairs as Art Basel and Frieze. (After several years, the art walks were discontinued; according to Blum, they had become “a circus.”)

The question for Southern California is not so much whether the area was/is ripe for Pop, but whether the whole ambience is… not preemptively Pop in itself...

PETER PLAGENS

By some accounts, Ruscha’s first memorable brush with Ferus came when he ducked into the gallery in 1960 to take in a joint exhibition of Johns’s sculptures and Kurt Schwitters’s collages. By the following year, he had met Hopps and Blum. In June of 1962, Ruscha was wowed when Ferus hosted Andy Warhol’s first solo show as a fine artist—the Campbell’s soup cans, all 32 varieties. “They were meant to be bad and they were meant to be badass,” Ruscha remembered of those stark redand-white canvases. “They were jarring.” It was the beginning of Warhol’s fine-art career, the moment Warhol became Warhol. Later that year, Hopps, who had moved over to the Pasadena Art Museum, included Ruscha in his “New Painting of Common Objects” show there, along with the likes of Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. The exhibition was Pop art’s Big Bang, and it trumpeted L.A.’s integral role in the genre’s emergence: After all, the entire city—with its cars, billboards, diners, movie stars—was practically a Pop-art readymade. “The question for Southern California,” the critic Peter Plagens wrote, “is not so much whether the area was/is ripe for Pop, but whether the whole ambience is… not preemptively Pop in itself.” The family who built the Space Needle in Seattle bought one of the Ruschas in the Pasadena show—Box Smashed Flat (Vicksburg), depicting a flattened Sun-Maid raisins box—for 50 bucks. It was Ruscha’s first real sale.

Hanging around Ferus, ground zero for an explosive moment in West Coast art, the young Ruscha acquired the nickname “water boy” from the accumulation of big, fractious personalities there, including the likes of Billy Al Bengston, Ed

Kienholz, Robert Irwin, John Altoon, Ed Moses, Craig Kauffman, and Kenneth Price. It was a veritable testosterone clubhouse, which Bengston described, in his inimitable way, as a “macho intellectual gang bang.” Blum recalled that Ruscha’s work was often met with bafflement among his would-be peers: “Was he celebrated? Not at all! Ed’s reception was lukewarm, if anything, among other artists, who were somewhat mystified by Ed and what he was up to. There were no precedents, as you might say. He did do a number of Pop-like paintings, but he was always on his own path.” Nevertheless, Blum took him on. “I just had a feeling,” he said. And so Blum offered the enigmatic young artist from Oklahoma City a solo show at Ferus in May of 1963. Ruscha was now in the club.

Route 66... It was a continuous ribbon, it was like a real magical formula for keeping my life going.

ED RUSCHA

“I had a vision that I was being a great reporter when I did the gas stations,” Ruscha once said. “I drove back to Oklahoma all the time, five or six times a year. And I felt there was so much wasteland between L.A. and Oklahoma City that somebody had to bring in the news to the city.” On another occasion, when Ruscha was asked why he chose to photograph gas stations, he said, “Because they were there.”

For Ruscha, Route 66 was “a continuous ribbon, it was like a real magical formula for keeping my life going.” During those road trips on which he amassed the images for Twentysix Gasoline Stations he would often get the side eye from servicestation attendants and owners. (One of Ruscha’s daybooks suggests that one such trip occurred in June of 1962, which is

possibly when the Amarillo photo was taken.) He didn’t always gas up and must have looked vaguely suspicious: a thief casing the joint or a Russian spy. He was occasionally accosted. When the book came out, many of his artistic peers were bemused. “The general response when you got a Ruscha book was to look through it with interest, then laugh, then look through it with interest,” Irwin remembered. “You kept looking for the story.” Warhol marveled at Ruscha’s gas-station photographs: “Ooh, I love that there are no people in them.” (Ruscha has always disliked having human figures in his work.)

I realized for the first time this book had an inexplicable thing I was looking for... and that was a kind of a ‘Huh?’

ED RUSCHA

For Ruscha, the book was a breakthrough in his development as an artist. “I realized for the first time this book had an inexplicable thing I was looking for,” he recalled, “and that was a kind of a ‘Huh?’” This became a kind of credo. From then on, Ruscha would be searching for ways to harness the power of “huh?” in idiosyncratic and enigmatic work that, as he put it, “makes you want to scratch your head and not resolve, not understand.”

The images themselves were decidedly not arty, not allegorical, not mystical, not romantic. Ruscha said of the gas stations, “They’re just natural facts.” If the Abstract Expressionists could be said to have avoided subject matter altogether, the Pop way, as in Twentysix Gasoline Stations, was to have subject matter so frank and obvious as to be both everything and entirely beside the point. Yet, as a subject, the gas station was highly redolent. There had been artistic antecedents in, say, Walker

Evans’s photographs and Edward Hopper’s moody, nocturnal Gas, from 1940. Midcentury architects such as Richard Neutra and Eliot Noyes were imbuing service stations with design panache, as befitting structures that stood along every roadside in an America that was defined by endless peregrination and conspicuous petroleum consumption.

...he began conceptualizing how to transfer the image of the Standard station in Amarillo into a large-scale painted image: “a gargantuan approach to a big canvas”...

Ruscha would later claim that he originally had no intention of ever using the photographs from Twentysix Gasoline Stations as the basis for painted works. But after the book came out, he began conceptualizing how to transfer the image of the Standard station in Amarillo into a large-scale painted image: “a gargantuan approach to a big canvas,” as he later summed it up. Starting with tempera and ink-and-paper studies, Ruscha mapped out a design that boldly split the canvas on a diagonal, from upper left to lower right, as he had done previously with his Large Trademark with Eight Spotlights (depicting the 20th Century Fox logo), a work shown at his 1963 Ferus show, suggesting, as Ruscha himself would later observe, that he saw the Standard station as another kind of “trademark.” He also included spotlights in the new painting (three, winnowed down from seven in early studies), which reversed the orientation of the Amarillo photograph and showed the Standard station from a vantage point that seemed to be practically below the paved surface of Northeast Eighth Avenue. The steep angle, exaggerated perspective, and vaulting diagonals evoked the timetested Hollywood filmmakers’ trick of shooting an approaching train from a low angle: Ruscha thus brought surging velocity to this still image, a maneuver he would continue to employ in future paintings.

There was another, improbable influence behind the stunning composition that became known as Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas. Ruscha has also claimed that he modeled the Standard station “after the way Bambi’s father stood in the forest.” This, in turn, reminded him of the stately buck used as a corporate symbol by the Hartford Insurance Company, where his father (who died in 1959) had worked. The autobiographical dimensions of Ruscha’s Standard station imagery have rarely been probed.

If the original black-and-white photograph had been pointedly boring, the resulting painting—reds and whites with an infinite inky sky and three probing yellow spotlights, all stretched across five-and-a-half by ten feet of canvas—was over-the-top drama. Ruscha had imbued a banal specimen of roadway architecture with jaw-dropping beauty and thunderous monumentality. “It has to be called an icon,” Ruscha later said. “It sort of aggrandizes itself before your eyes. That was the intention of it, although the origins were comic.”

Having never intended to make a gas-station painting, Ruscha now decided to make another one. For this iteration, the same size as the first, he would show the Standard station in daylight. He had toyed with the notion of a book called Standard Station at Various Times of Day, which seems related to this idea. The book never happened (Ruscha ultimately deemed this Monet-esque conceit “too simple”), but the painting did. Ruscha’s studio notebooks show him at work on the piece during the summer of 1964, with his second Ferus show scheduled to open October 20th

Standard Station, Amarillo Texas (Day) was perhaps an early title, as Ruscha kept the layout he used for the first painting but dispensed with the night sky and replaced it with a bright blue that, for all its stylization, is pretty much an exact match for a clear afternoon sky on the Great Plains. For obvious reasons, the yellow spotlights are now gone. As in the first painting, there are five red Chevron pumps (close inspection reveals their make and model to be Wayne 505s) in the same two-three configuration. (The totals on the pumps—$2.27, $4,21—remind us that we’re looking at the early 1960s.) But, because we’re now seeing the service station in daylight, there are deeper shadows, cool blue ones, under the canopy; the first painting had shown this area illuminated by fluorescent tube lighting, drenching everything in shadowless, artificial white. In the original Standard station painting Ruscha left in some perspective lines, displaying draftsmanlike underpinnings; in the second version they have been expunged.

Often, when an idea is so overwhelming I use a small unlike item to ‘nag’ the theme.

ED RUSCHA

A wholly novel element differentiates the new painting: a pulp magazine hovering near the top-right corner that determined the title Ruscha ultimately gave the piece: Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half. The dime Western in question, ripped and spindled, is the October 1946 issue of Popular Western, which Ruscha had included in his Noise, Pencil, Broken Pencil, Cheap Western, executed in the spring of 1963. In the Standard station painting, the mutilated magazine appears to sit, trompe l’oeil style, on the flat, pristine surface. In one of his studies, Ruscha had placed a cocktail olive there

October 1946 issue of Popular Western, A Thrilling Publication, vo. 31, no. 2.

instead of the magazine. Ruscha later described this impulse toward such visual non-sequiturs: “Often, when an idea is so overwhelming I use a small unlike item to ‘nag’ the theme.” He has also compared this antagonistic, “unlike” element to the coda on a piece of music. In adding Popular Western, Ruscha also slyly brought a human figure into the composition, as the cover shows a Texas Ranger who has just shot a bank robber. “So I was painting a painting of a painting,” the artist said.

Ruscha’s twin Standard station paintings hinted at the seriality Warhol had explored in his Campbell’s soup can paintings. As in other Ruscha works there was an emphasis on a word—“STANDARD”—but now the word was part of a landscape. There have been inflated interpretations attempting to read “standard” as a commentary about standardization or ordinariness, but Ruscha has always shot them down, suggesting that any buried meanings are in the eyes of the beholder.

The immense canvas was the sole occupant of the left-hand wall, a head-snapping opening chord.

At the opening of Ruscha’s 1964 Ferus show, when visitors swung through the gallery’s front door and made a hairpin left into the front space, they were confronted with Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half; the immense canvas was the sole occupant of the left-hand wall, a head-snapping opening chord. Ruscha placed Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas, on the far back wall of the gallery, thus bookending the show: a rousing grand finale. Nancy Marmer, writing in Artforum, was

impressed by the colossal paintings; she preferred the ten-cent Western version. (The San Francisco-based magazine would relocate to a space above Ferus in 1965; Ruscha worked there doing layouts under moniker Eddie Russia.)

Blum sold the twin Standard station paintings to two couples who had emerged as friendly rivals among Los Angeles collectors; they were perhaps the most significant Southern Californian collectors of the mid-1960s, at least in terms of boldness and youth. Donald and Lynn Factor—the grandson of the cosmetics titan Max Factor and his high-school sweetheart— bought Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half while Dennis Hopper and Brooke Hayward—the twentysomething Hollywood couple who seemed to connect and catalyze everything in 1960s Los Angeles, like a modern-day Gerald and Sara Murphy—bought Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas. Hopper remembered that he and his wife paid $780 for it; Ruscha’s recollection put it closer to $1,500. (It may be that they paid Blum $1,540, with half going to Ruscha, or that they paid in two installments of $780.) Presumably, the Factors paid the same, or a similar, price for their Standard station painting.

Hopper and Ruscha shared an intimate friendship, with Hopper becoming part of the Ferus club as cheerleader, patron, and something of a staff photographer, shooting portraits of Kienholz, Bengston, Irwin, Larry Bell, and, naturally, Ruscha. Hopper’s 1964 portrait of Ruscha standing in front of Koontz’s hardware store on Santa Monica Boulevard may well be the best-known photographic portrait of Ruscha. His photograph Double Standard, a cacophonous image of a multi-pronged intersection with a Standard station right at the center of it, was used in the announcement for Ruscha’s Ferus show.

The Hoppers’ modest Spanish Colonial house at 1712 North Crescent Heights, in the Hollywood Hills, was the de facto living room of 1960s L.A., a stopping place for artists, writers, rock stars, activists, Hells Angels, Black Panthers, Old Hollywood royals, and New Hollywood upstarts. It was also filled with one of the most avant-garde art collections in America: Warhols, Stellas, Lichtensteins, Kienholzes, Rauschenbergs, even a Duchamp coauthored by Hopper himself. (Hopper, Hayward, Ruscha, and many others in their set met Duchamp when Hopps organized a landmark Duchamp retrospective at the Pasadena Museum in 1963.) The couple, whom Blum remembers as the only Hollywood people who made a habit of coming to Ferus, installed the Standard station painting over a couch in the den, amid a fanciful interior—cutting-edge Pop art combined with piles of found objets, Belle Epoque posters, Americana junk, Victoriana—that Ruscha remembered being like “a carnival, with a candy-store energy.” (Warhol, the guest of honor at a raucous party the couple threw there in September of 1963, compared it to an amusement park.) The couple’s children would forever remember whiling away Saturday mornings watching Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoons and learning how to hula hoop underneath the wide expanse of Ruscha’s Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas

Over at the Factors’, Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half graced a wall in the vast, atrium-like living room at their semi-famous “house with no windows,” a modernist molehill at 701 North Maple Drive, in Beverly Hills, designed by Richard Langendorf. (In later decades, the house became the residence of the singer Diana Ross.) A similarly massive Craig Kauffman relief piece was hung on an adjacent wall. The Factors’ collection echoed that of the Hopper-Haywards: Lichtensteins, Stellas, Kienholzes, Bengstons. They decorated their son’s bedroom with one of Warhol’s Liz Taylor silkscreens; his name, appropriately enough, was Andy. The two couples

shared interests, outings, and kids’ birthdays, with Hopper occasionally photographing the proceedings. Their children may well have assumed that nearly everyone had a ten-foot-wide Standard station painting at home. (In early 1967, the couples loaned works to the Three Young Collectors show at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, the third collecting couple being André and Dory Previn.)

For Ruscha, the sale of these pieces changed everything. “I was floored,” he recalled. “I never knew that I would ever be able to move something like that through the gallery. I would make these artworks and I was doing it for sport. I never expected to make a career out of it.” In a meaningful way, the Factors and the Hopper-Haywards had provided momentum for Ruscha to achieve viability as a working artist. The Standard station paintings made it so. They also helped define a vibrant period in postwar American art, not to mention the cultural ferment that erupted in Los Angeles in the 1960s, a time of Brian Wilson’s “Good Vibrations,” Joan Didion’s “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream,” and the first rumblings of the New Hollywood: the California dream at its brief, golden apogee.

[The Standard Stations] helped define a vibrant period in postwar American art…

At some point in the first half of the 1970s, Brooke Hayward, having divorced Dennis Hopper, sold Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas, to Artforum publisher Charles Cowles. In late 1976, the painting landed at Stephen Mazoh’s gallery in New York. Irving Blum flirted with the idea of reacquiring the piece he had sold in 1964, but another buyer ended up with it. “I often think about it,” Blum said, “and I regret it to this day!” The buyer’s friend

James Meeker, the art critic for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, happened to own Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half, having obtained it from the Factors. The buyer and Meeker immediately arranged an extraordinary trade of their twin Standard station paintings. Shortly thereafter, Meeker gave Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas to his alma mater, Dartmouth, where it has been in the permanent collection of the college’s Hood Museum of Art ever since. Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half has remained under the same ownership for 48 years, having been on loan to the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth since 1977. In 1976, it was requested for inclusion in the American pavilion of that year’s Venice Biennale, but it was already committed to the Painting and Sculpture in California: The Modern Era show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Over the decades, the painting has traveled to various exhibitions, including Ruscha’s mammoth Now/Then retrospective, which opened at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York in September of 2023 before moving to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in April of 2024. (Now/Then reunited the two Standard station paintings.)

Ruscha would later suggest that the image of the Standard station in Amarillo was the best-known of his creations. He revisited it in a handful of iterations, in various media, including two versions that showed the station engulfed in flames. In 2009, Ruscha said he was considering a new version of Standard Station, with “reference to the passage of time,” perhaps along similar thematic lines as his Course of Empire series. There is no evidence that he ever pursued this. While Ruscha never wanted to imbue his Standard station paintings with nostalgia, in the 21st century, they are now something out of the American past, evoking a phrase the artist likes to employ: “It’s from ago.” Yet the Standard station building still exists, at 4001 East Amarillo

You want to instill a thing with some earth-shaking religious feeling. You want to hear organ music.

ED RUSCHA

Boulevard, in Amarillo. It is now a transmission shop. When I called the establishment recently to ask a few questions about the famous artist and his famous work, the person on the other end had no idea what I was talking about.

Ruscha, now 86, is still at it every day in his Culver City studio. When I once asked him about his daily routine there, he said, “Well, sometimes I’m fumbling. And sometimes I have a vague idea.” Yet, across the decades, Ruscha has continued to explore modern life with mordant wit, exquisite technique, and probing attention to picture-making. In the stuff of the everyday—conversational snippets, a pothole in Sepulveda Boulevard, a nondescript gas station in west Texas—he has found deep reservoirs of meaning, or, at least, opportunities to stop, look, consider, appreciate, laugh, or scratch your head: “Huh?” Like, say, Bob Dylan and Don DeLillo, he has shown Americans who they are. And his impassive gaze on the bland surface of things has imbued them with unmistakable aura and hum. “Once you pick the object and reproduce it faithfully,” Ruscha has said, “you want the thing to glimmer. You want it to have inner power. You want to instill a thing with some earthshaking religious feeling. You want to hear organ music.” When you look at a painting like Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half you hear it loud and clear.

Max Carter

Walter Hopps, the co-founder of the Ferus Gallery and former director of the Pasadena Art Museum, divided 20th century art into three streams, or “imperatives”: realism, abstraction and imagism. The realist tendency was represented by Walker Evans and Edward Hopper; the abstract by Barnett Newman and Jackson Pollock; and the imagist way, which Hopps characterized as depicting “specific literal objects, but in ways that are disjunctive, often arranged as visual metaphors”, by Ed Ruscha, notwithstanding his “dead on, straight ahead” photography. To Hopps, Ruscha’s closest imagist peers were René Magritte and Jasper Johns.

In 1977, Ruscha called seeing Johns’s Target with Four Faces (1955) two decades before, in Print magazine, “an atomic bomb in my training”. But I suspect his kinship with Magritte, whom Ruscha met through their mutual dealer, Alexander Iolas, better explains the sort of artist he wished to be, and how he came to paint his masterpiece of American paradox, Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half (1964). Ruscha once described Magritte’s roundabout influence to Howardena Pindell as “360-degree influence. That’s influence from a person’s thoughts and force and not from his pictures, which the person being influenced has not seen, until later…”

Magritte was raised on the thrills of detective fiction, Ruscha on cheap Westerns. Although Magritte preferred bowler hats to bolo ties, he enjoyed the cowboy films of John Wayne, who apparently reciprocated. (The young Wayne, then known as Marion Morrison, was Hopps’s mother’s first serious boyfriend.) His native Belgium was an outpost, as far culturally from Paris as Ruscha’s Oklahoma and Los Angeles were from midcentury New York. (“What is the difference between a potato and a Belgian?” went the old joke. Answer: “A potato is cultivated.”) And this distance suited them.

It was an enormous freedom to be premeditated about my art.

ED RUSCHA

Like Ruscha, Magritte’s “revelation” came via reproduction. A friend showed him Giorgio de Chirico’s Le Chant d’amour (1914) in 1923. “Chirico was the first,” Magritte remembered admiringly, “to consider what has to be painted rather than how to paint.” On being exposed to Johns, the 20-year-old Ruscha similarly “began to see that the only thing to do would be a preconceived image. It was an enormous freedom to be premeditated about my art. I wanted to make pictures, but I didn’t want to paint. Some painters just love paint—they get up in the morning and grab a brush, not knowing what they are going to do, but they just have to have that hot brush moving those colors. But I was more interested in the end result than I was in the means to the end.” What, then, is the end result of Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half? What had to be painted?

I picked more or less neutral subjects that would not ordinarily be chosen as subjects for art.

ED RUSCHA

When Ruscha left home for California and the Chouinard Art Institute in 1956, he drove along Route 66 with his childhood friend Mason Williams; the poverty-stricken Joad family had taken the same path west from Oklahoma in The Grapes of Wrath (1940), John Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Depression-era novel. The world-famous highway, established in 1926 and running from Chicago to Los Angeles, was the basis for the 1946 rhythm and blues song, “(Get Your Kicks) Route 66” (“if you ever plan to motor west / travel my way, take the highway that’s the best”). And in the early 1960s it served as the backdrop for Route 66, an anthology series filmed entirely on location.

Recent travels around Europe offered Ruscha surprisingly little in the way of inspiration: “I really learned nothing… I just yawned a lot.” (His Chouinard teacher, the perceptual artist Robert Irwin, had been no more impressed ten years earlier: “I was so fucking tired of brown paintings. I mean, they all looked exactly the same!”) Returning to Oklahoma to visit family in 1962, Ruscha photographed the nondescript gas stations studding the roadside. These unpeopled, essentially documentary images, which possessed “that factual kind of army-navy data look to it” Ruscha favored, would form his first book, Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963). Why take up gas stations? “Because they were there,” Ruscha observed, “like trees... I picked more or less neutral subjects that would not ordinarily be chosen as subjects for art.”

These unpeopled, essentially documentary images, which possessed “that factual kind of army-navy data look to it” Ruscha favored, would form his first book, TwentysixGasolineStations(1963).

Standard, Amarillo, Texas (1962), the source photograph for the 1963 oil of the same title as well as the present painting, suggests something like the opposite of greatness. Shot at street level from the left with no discernible subtext, the simple, lowslung structure looks deserted and thoroughly unremarkable. Its dramatic transformation onto canvas over the next two years saw it flipped, elongated and endowed with breathtaking color and movement.

The present work relates to, and is anticipated by, three paintings from this intervening period: Large Trademark with Eight Spotlights (1962), Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas and Noise, Pencil, Broken Pencil, Cheap Western (both 1963). And it responds formally in its way to each.

Large Trademark with Eight Spotlights was Ruscha’s first monumental horizontal canvas. Measuring 5 ½ feet by slightly over 11, it shows the 20th Century Fox logo projected in red at left, trailed by white beams emanating from the lower right corner and set against black with eight golden spotlights overhead. (Ruscha never forgot the “big movie searchlights” on La Cienaga the Ferus directors rented for an opening for John Altoon: “There were hijinks like that, which you couldn’t ignore.”) The effect is at once Hollywood premiere and panorama, with the studio’s logo itself as the attraction.

The painting’s unusual format replicates the immersive double width of the CinemaScope anamorphic lens, the brainchild of 20th Century Fox’s then-president, Spyros P. Skouras. (Fox’s first CinemaScope production, the now-obscure biblical epic, The Robe, was the top-grossing movie of 1953.) That 20th Century Fox was quite literally in the red—faced with highly publicized cost overruns on Cleopatra (1963), it sold its back lot and accepted Skouras’s resignation—only adds piquancy to the composition’s peculiar weightlessness and unsettling sense of “Hollywoodization”.

The effect is at once Hollywood premiere and panorama, with the studio’s logo itself as the attraction.

“Hollywood is like a verb to me,” Ruscha said in 1981. “It’s something that you can do to any subject or any thing. You can take something in Grand Rapids, Michigan and ‘Hollywoodize’ it. They do it with automobiles, they do it with everything that we manufacture. It all somehow comes out of that… ‘Hollywood dreams’—I mean, think about it. Close your eyes and what does it mean, visually? It means a ray of light, actually, to me, rather than a success story. And so I play around with the ray of light rather than with the success story. I’m not interested so much in success stories or living out success stories personally. The phenomenon of the thing is just the imagery that comes out of it. If you look at the 20th Century Fox, you get this feeling of concrete immortality. The letters actually come out of this shaft that is shooting way back in the ground like this, you know, and it’s all substance. But in a sense that’s like a ray of light so those images are in my work.”

And, indeed, Ruscha’s Hollywoodization was everywhere and, practically by definition, as old as Hollywood. From 19461948, the victorious Allied powers tried Japanese war crimes

amidst the ruins of Tokyo. Despite—or possibly because of—the grave, life-and-death nature of the proceedings, six large arrays of klieg lights were built into the courtroom’s ceiling. The Chinese judge, Mei Ruao, prefiguring Ruscha, marveled that “Anything could be Hollywood-ized.” For Time magazine’s foreign reporter, “The klieg lights suggested a Hollywood premiere.”

A logo on its own, no matter how suggestive, would not achieve the desired impact...

A logo on its own, no matter how suggestive, would not achieve the desired impact, however. (It may be that Ruscha later destroyed his square, unfinished painting bearing the Paramount Pictures logo for this reason.) In Large Trademark, Ruscha goes further and slices the picture plane diagonally from lower right to upper left. As he recalled in 1989, “The diagonal comes out of the idea of motion and speed, as well as perspective. When you divide the canvas like that you always have the suggestion of speed and depth.” The 20th Century Fox logo, static on the screen, flies headlong across the canvas with the force of an approaching train. The combination of speed and striking lettering evokes the 20th Century Limited, the express passenger line linking New York and Chicago, Route 66’s eastern origin and terminus. The 20th Century Limited rivaled Route 66 in the country’s popular imagination—”red carpet treatment” was coined for the crimson carpeting passengers entered from in New York, and it was the subject of the 1934 play, Twentieth Century, and its film and musical adaptations.

It also echoes a memory I had of watching movies when I was young. It seemed like all movies would have a train in them.

ED RUSCHA

Twenty years ago, Ruscha looked back on the photograph of the Standard station in Amarillo, Texas as “the model for other depictions, with its baseline perspective and its diagonal screaming overhead. It followed an idea I had about cinematic reality. In the painting, Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas (1963), the spotlights connote something as farfetched as trumpet sounds or an announcement of a gala of some sort. It’s like adding noise to a picture. It’s not simply a story about a type of architecture that I might be interested in. It also echoes a memory I had of watching movies when I was young. It seemed like all movies would have a train in them. Invariably, they had the camera down on the tracks and shot this train so it appeared as though it was coming from nowhere, from a little point in the distance, to suddenly zooming in and filling your total range of vision. In a sense, that’s what the Standard gas station is doing. It’s super drama.” The offscreen swell of trumpets and gala atmosphere were the special hallmarks of Large Trademark, the aggrandized logo, propulsive train-like motion, black background, cinematic spotlighting and sleek, diagonal orientation of which carry into Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas.

As in Large Trademark, the significance of the logo is ambiguous—is “Standard” banal and uniform, or does it, as John D. Rockefeller intended, communicate quality?—and the colors run white-to-red from left to right. While the photograph’s five pumps are richly executed, the gas station retains the bare expanses and hard, precise tracings of an architectural rendering.

With Noise, Pencil, Broken Pencil, Cheap Western Ruscha reverted to his more customary 6 by 5 ½ feet canvas size. The dark, monochrome background and bold red letters in white silhouette—“Noise”, blaring from above—recur. To these, Ruscha has added disparate elements: an intact pencil at left, its broken counterpoint at right and, floating above the lower edge, the “Cheap Western” of the title.

Ruscha termed these curious items “Unlike thoughts or objects inserted at the end or out-of-the-way from a main dominant theme.”

Ruscha termed these curious items “Unlike thoughts or objects inserted at the end or out-of-the-way from a main dominant theme. Often, when an idea is so overwhelming I use a small unlike item to ‘nag’ the theme.” If noise is impossible to paint, the unopened magazine at the opposite end plays on silence. It “nags”. (Or is the fracturing pencil lower case “noise”?)

Hollywoodized, in double-wide format, containing the thrusting diagonal sight line and small “unlike item”—Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half is, in many respects, the grand synthesis of this masterpiece sequence. In her 1964 Artforum review of Ruscha’s second one-man exhibition at Ferus, Nancy Marmer singled out Standard Station, Ten-Cent Western Being Torn in Half for praise. The Western is an assertion of “personality” and “The vacant station is painted as a lunar architect’s plan might be, using hard-edged forms, clean lines, sharply defined perspectives in airless flat space, and brilliantly stifling color. In the upper right-hand corner is a torn western magazine, illusionistically portrayed so as to seem attached to,

TorninHalfis, in many respects, the grand synthesis of this masterpiece sequence.

rather than painted on, the canvas. The placement is surrealistic, the notion poetic; but the ontological gap between magazine and painting is finally impossible to bridge.” Lacking “such literary devices”, the scheme of Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas was, for Marmer, “less satisfying in [its] heavy-handed reliance on value contrasts for dramatic effect.”

Superficial similarities with Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas have seen the present painting occasionally titled Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas (Day) and incorrectly dated 1963. Yet its differences, as Marmer noted, are profound.

An exquisite blue has replaced black in the sky; the spotlights and gas hoses on the leftmost and center pumps have been eliminated; angled shadows and shades of blue-gray now lend mass and reality to the façade; and the October 1946 issue of Popular Western from Noise, Pencil, Broken Pencil, Cheap Western mysteriously reappears, half-torn, in the upper right where before there was only darkness. (Naturally, Popular Western’s parent company from 1943-1955 was Standard Comics.) I am not sure, as Marmer had been, that the gap between the Western and painting cannot be bridged.

There is first the matter of placement. In Ruscha’s sketchbook, on July 6th, 1964 he toys with positioning the Western at the center right edge (“would it be better here?”), roughly where the broken pencil had been in Noise, Pencil, Broken Pencil, Cheap Western. On the right-facing sheet, Ruscha makes the obscure notation “celery, lettuce” below his ink study, which illustrates their corresponding shapes at center and upper right. Ruscha’s use of vegetables as visual shorthand is not necessarily surprising. In 1990, he likened making art to “working in the kitchen: there are all these vegetables. I’m always looking at ways to concoct new things, I use different elements, and I feel I have to surprise myself, while at the same time staying faithful to my art.” In the final version, the Western sits neatly between an invisible diagonal from the lower left to the upper right corner, and the line of the overhang’s principal shadow if traced all the way to the right edge.

I’m always looking at ways to concoct new things, I use different elements, and I feel I have to surprise myself, while at the same time staying faithful to my art.

ED RUSCHA

“How do you get all these pictures without people in them?” Andy Warhol asked Ruscha of Twentysix Gasoline Stations. “I don’t like imagery of people,” he acknowledged in 1973. “Instead of using people, I’ll use something else. But I’ve painted a picture of a dead man—it was actually a painting of a magazine cover that had a dead man on it. So I was painting a painting of a painting.” On the Popular Western cover— which lists the contributor aliases “Tom Gunn” and “Gunnison Steele”—the sheriff strides forward, leaving the dead bank robber in his wake; ironically, the only smoke in the gas station’s vicinity issues from the bygone cowboy’s pistols.

Interviewed for his first retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1982, Ruscha reflected that “Books and their titles have always been important to me. So the title of my artworks is very important to me—sometimes as important as the work itself.” It is probably no coincidence that the Western’s qualifying adjective evolved from “Cheap” to “Ten-Cent”, or the amount of tax per gallon quoted on the pumps. The oncepriceless frontier experience could be bought, in 1946, for 10 cents. By 1964, 10 cents was the tax on one gallon of gas; not merely cast aside, the Western is being ripped in half. (Ruscha had not yet satisfied this destructive urge. The snapped pencil and torn magazine give way to the focal conflagrations of Norm’s, La Cienaga, on Fire [1964], Los Angeles County Museum of Art on Fire [1965-68] and the smaller-scale burning gas stations.) Are we to judge between the fading romance of the West and the station’s cool, ascendant modernity? Standard Station, TenCent Western Being Torn in Half asks but does not answer.

Does “Standard” mean the base or the bar? Is the Western an artifact of rugged individualism or disposable mass media, the boy’s treasure of today or the tattered refuse of tomorrow? Times change, standards shift, heroes are replaced. What could be more American than that?

EDITOR

Max Carter

ASSISTANT EDITORS

Lee Cohen

Anne Homans

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Stacey Sayer

ART DIRECTOR & DESIGNER

Kent Albin

SPECIAL THANKS

John Elderfield

Johanna Flaum

Sara Friedlander

Maggie Hoag

Emily Kaplan

Rachel Ng

Mark Rozzo

Corrie Searls

Lawrence Weschler

Kathryn Zabik

19 November 2024

20 Rockefeller Plaza

New York, NY 10020

Admission to this sale is by ticket only. Please call +1 212.636.2000 for further information.

Saturday, November 9 10:00am - 5:00pm

Sunday, November 10 1:00pm - 5:00pm

Monday, November 11 10:00am - 5:00pm

Tuesday, November 12 10:00am - 5:00pm

Wednesday, November 13 10:00am - 5:00pm

Thursday, November 14 10:00am - 5:00pm

Friday, November 15 10:00am - 5:00pm

Saturday, November 16 10:00am - 5:00pm

Sunday, November 17 1:00pm - 5:00pm

Monday, November 18 10:00am - 5:00pm

The sale of this lot is subject to the Conditions of Sale, Important Notices and Explanation of Cataloguing Practice which are set out online, with other important sale information at christies.com. Please see the Conditions of Sale at christies.com for full information about the sale and descriptions of symbols.