2 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF DAVID GEFFEN ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I SALE 9 November 2023 S�E�IALIS� Max Carter +1 212 636 2091 mcarter@christies.com

4 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

5

“Gorky was before the books.”

WILLEM DE KOONING

6 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

7 CONTENTS The Ballroom Series — Matthew Spender 27 Gorky’s Originality — John Elderfield 39 Moonlight — Jed Perl 61 From the Ashes — Hayden Herrera 69 Charred Beloved I — Max Carter 79 Endnotes 94 Acknowledgments 99 Sale Information 101

8 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

CONTRIBUTORS

Matthew Spender is a sculptor, the author of Within Tuscany: Reflections On a Time and Place, From a High Place: A Life of Arshile Gorky and A House In St. John’s Wood: In Search of My Parents, and the editor of Gorky’s collected letters, The Plow and the Song.

John Elderfield is Chief Curator Emeritus of Painting and Sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art, New York and was the inaugural Allen R. Adler, Class of 1967, Distinguished Curator and Lecturer at the Princeton University Art Museum. He is the author of many books, more than one hundred articles and, over thirty years, the organizer of seminal retrospectives at The Museum of Modern Art of Kurt Schwitters (1985), Henri Matisse (1992), Pierre Bonnard (1998) and Willem de Kooning (2011-12); and exhibitions in London, Paris, and Washington, D.C., of Cezanne Portraits (2017) and, in Princeton, of Cezanne’s Rock & Quarry Paintings (2020).

Jed Perl is the author of the two-volume biography of Alexander Calder and a regular contributor to The New York Review of Books. His other books include Paris Without End, Magicians & Charlatans, Antoine’s Alphabet, New Art City, and Authority and Freedom: A Defense of the Arts. For twenty years, he was the art critic of The New Republic.

Hayden Herrera is an art historian and the author of biographies of Frida Kahlo, Arshile Gorky, Mary Frank, Isamu Noguchi and Henri Matisse. Her biography of Gorky was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and her biography of Noguchi won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Her most recent book is the memoir Upper Bohemia.

Max Carter is Vice Chairman of 20th and 21st Century Art at Christie’s.

9

10 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

CHARRED BELOVED I

11

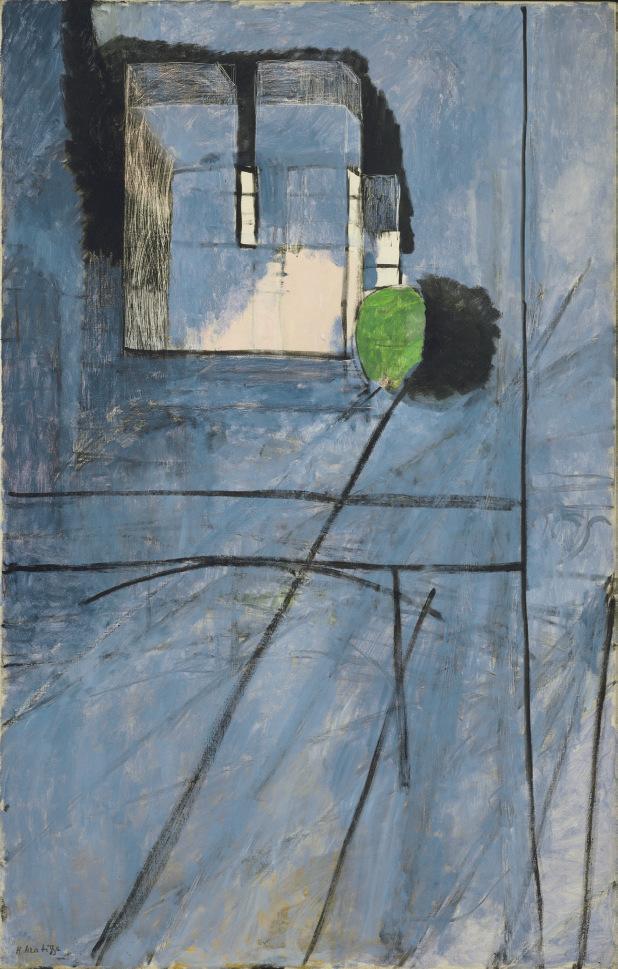

PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF DAVID GEFFEN ARSHILE GORKY (1904-1948)

Charred Beloved I

inscribed by Agnes Gorky Phillips, the artist’s widow, ‘a. gorky’ (upper left)

oil on canvas

53 ½ x 39 ¾ in. (135.9 x 101 cm.)

Painted in 1946

ESTIMATE ON REQUEST

PROVENANCE

Estate of the artist.

Sidney Janis Gallery, New York (1952).

Marie and Walter M. Zivi, Chicago (1956). Richard Gray Gallery, Chicago (1976).

Gerald S. Elliott, Chicago (1976).

Victoria and S. I. Newhouse, Jr., New York (circa 1989).

Adriana and Robert Mnuchin, New York (circa 1993).

Acquired from the above by the present owner, 1993.

EXHIBITED

New York, Sidney Janis Gallery, Arshile Gorky In The Final Years, February-March 1953, no. 11.

New York, Museum of Modern Art and Washington, D.C., Washington Gallery of Modern Art, Arshile Gorky, 1904-1948, December 1962-April 1963, p. 38.

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago Collectors, September-October 1963, p. 5.

Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art, Modern Masters from Chicago Collections, September-October 1972.

New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Acquisition Priorities: Aspects of Postwar Painting in America; Including Arshile Gorky: Works 1944-1948, October 1976-January 1977, p. 35, no. 2 (illustrated). University of Chicago, David and Alfred Smart Gallery, Abstract Expressionism: A Tribute to Harold Rosenberg: Paintings and Drawings from Chicago Collections, October-November 1979, pp. 24 and 47, no. 12.

New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; Dallas Museum of Fine Arts and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Arshile Gorky 1904-1948: A Retrospective, April 1981-February 1982, pp. 57-59 and 178, no. 195 (illustrated).

New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, The New York School: Four Decades, Guggenheim Museum Collection and Major Loans, July-August 1982, no. 16.

Madrid, Sala de Exposiciones de la Fundación Caja de Pensiones and London, Whitechapel Art Gallery, Arshile Gorky 1904-1948, October 1989-March 1990, p. 115, no. 40 (illustrated).

Berlin, Martin-Gropius-Bau; London, Royal Academy of Arts and London, Saatchi Gallery, American Art in the 20th Century: Painting and Sculpture 1913-1993, May-December 1993, n.p., no. 83 (illustrated).

New York, Gagosian Gallery, Arshile Gorky: Late Paintings, January-March 1994, pp. 34-35 and 43 (illustrated).

Washington, D.C., The National Gallery of Art; Buffalo, Albright-Knox Art Gallery and Fort Worth, Modern Art Museum, Arshile Gorky: The Breakthrough Years, May 1995-March 1996, pp. 22, 75, 114-115, no. 13 (illustrated).

Philadelphia Museum of Art; London, Tate Modern and Los Angeles, Museum of Contemporary Art, Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective, October 2009-September 2010, pp. 329 and 391, pl. 166 (illustrated).

12 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

13

LITERATURE

R. Rosenblum, “Gorky, Matta, de Kooning, Pollock,” Arts Digest, New York, vol. 29, no. 17, 1 June 1955, p. 24.

“Special issue on Gorky in Italian and English with text by Toti Scialoja and excerpts from Schwabacher 1957,” Arti Visive, Summer 1957, no. 2 (illustrated).

E. Schwabacher, Arshile Gorky, New York, 1957, pp. 115 and 126. 33 Paintings by Arshile Gorky, exh. cat., New York, Sidney Janis Gallery, 1957, n.p., fig. 38 (illustrated).

H. Rosenberg, Arshile Gorky: The Man, The Time, The Idea, New York, 1962, p. 104 (listed as Charred Beloved).

J. Levy, Arshile Gorky, New York, 1966, p. 161, pl. 137 (illustrated).

B. Rose, “Arshile Gorky and John Graham: Eastern Exiles in a Western World,” Arts Magazine, vol. 50, no. 7, March 1976, p. 67 (illustrated).

H. Herrera, “The Sculptures of Arshile Gorky,” Arts Magazine, vol. 50, no. 7, March 1976, p. 89.

H. Rand, Arshile Gorky: The Implication of Symbols, London and Montclair, 1980, p. 238, fig.14-1 (illustrated).

M. FitzGerald, “Arshile Gorky,” Arts Magazine, vol. 55, no. 10, June 1981, p. 23 (illustrated).

J. M. Jordan, “Gorky at the Guggenheim,” Art Journal, vol. 41, no. 3, Fall 1981, p. 263.

D. Waldman, “Arshile Gorky: Poet in Paint,” Arshile Gorky 1904-1948: A Retrospective, exh. cat., New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1981, p. 57.

J. M. Jordan and R. Goldwater, The Paintings of Arshile Gorky: A Critical Catalogue, New York, 1982, pp. 88 and 468-470, no. 305 (illustrated).

M. P. Lader, Arshile Gorky, New York, 1985, pp. 90-91, fig. 89 (illustrated).

C. Frankel, “Gorky: Tragic Lyricism,” International Herald Tribune, 10-11 March 1990, p. 7.

Arshile Gorky: Oeuvres sur Papier, 1929–1947, exh. cat., Lausanne, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, 1990, p. 36, fig. 19 (illustrated).

H. Rand, Arshile Gorky: The Implication of Symbols, Berkeley, 1991, p. 238, pl. XIV, fig. 14-1 (illustrated).

Arshile Gorky: Works on Paper, exh. cat., Rome, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, 1992, p. 108 (listed as Charred Beloved).

P. Balakian, “Arshile Gorky and the Armenian Genocide,” Art in America, vol. 84, February 1996, p. 109 (listed as Charred Beloved).

D. Ades, Surrealist Art: The Lindy and Edwin Bergman Collection at the Institute of Chicago, Chicago and New York, 1997, p. 212.

N. Matossian, Black Angel: The Life of Arshile Gorky, London, 1998, n.p., pl. 12 (illustrated).

M. Spender, From A High Place: A Life of Arshile Gorky, New York, 1999, pp. 304, 308 and 309.

H. Herrera, Arshile Gorky: His Life and Work, New York, 2003, pp. 482, 507-508, 518, 520, 557 and 566, fig. 166 (illustrated).

P. Schjeldahl, “Self-Made Man,” The New Yorker, Issue 79, 8 September 2003, p. 95 (illustrated).

New York, New York: Fifty Years of Art, Architecture, Cinema, Performance, Photography and Video, Monaco, Grimaldi Forum, 2006, pp. 79 and 521, no. 13 (illustrated).

A. Beredjiklian, Arshile Gorky: sept thèmes majeurs, Suresnes, 2007, pp. 55 and 62.

R. S. Mattison, Arshile Gorky: Works and Writings, Barcelona, 2009, p. 109 (illustrated).

Arshile Gorky: 1904-1948, exh. cat., Venice, Ca’ Pesaro Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna, 2019, pp. 226-227 (illustrated and listed as Charred Beloved).

E. Costello, ed., Arshile Gorky Catalogue Raisonné, New York, 2022-ongoing, no. P305 (illustrated in color).

14 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

15

Installation view, Arshile Gorky: 1904-1948, December 19, 1962 - February 12, 1963, Museum of Modern Art, New York (present lot illustrated). Photo: Soichi Sunami. © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. Artwork: © 2023 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

16

ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

THE BALLROOM SERIES

17

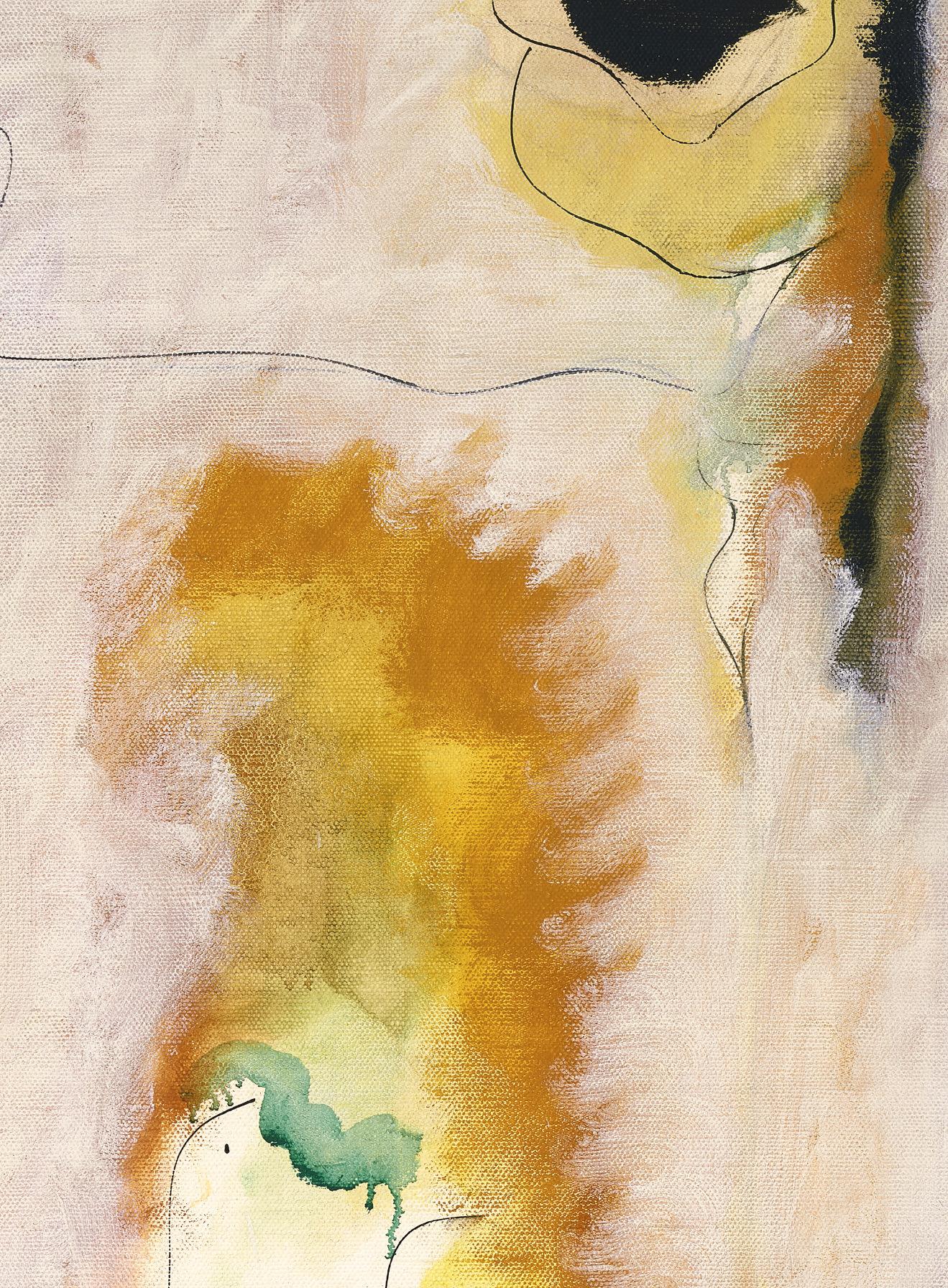

THE BALLROOM SERIES P305*

The present work.

* “P” (paintings) and “D” (drawings) numbers correspond to the works’ respective entries in Arshile Gorky Catalogue Raisonné, ed. Eileen Costello, https://www.gorkycatalogue.org

18

ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

19

Arshile Gorky, Charred Beloved No. 2, 1946. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. © 2023 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

P306

Photo: National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

THE BALLROOM SERIES

20 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

Arshile Gorky, Nude, 1946. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

© 2023 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Photo: Lee Stalsworth / Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

P307

21

Arshile Gorky, Charred Beloved No. 1, 1946. Private Collection. © 2023 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

P371

Photo: Paul Hester.

24

ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

ESSAYS

25

26 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

THE BALLROOM SERIES

On January 16th, 1946, Gorky accidentally burned down the borrowed barn which he’d been using as a studio. It was winter in the Connecticut countryside, and a stove had been installed shortly before he’d moved in. A metal chimney inserted through the wall of the building was not properly insulated and he’d stacked the stove with too much wood. The result was inevitable. But Gorky also loved fires, the bigger the better. They held a haunting fascination for him. His grandmother had burned down the family church on Lake Van after the local Kurds had murdered her son, and her epithet of “God-burner” was part of Gorky’s personal legend.

After the Connecticut fire, through friends, Gorky found a temporary studio in New York: the ballroom of an apartment at 1200 Fifth Avenue, 19 blocks north of the Metropolitan Museum. This large and handsome flat, which had been photographed for House & Garden magazine a dozen years before, was dauntingly grand. It’s unlikely that Gorky moved in carrying large quantities of art materials and a backlog of unfinished canvases.1

He was only here for two or three weeks, before illness in early March sent him to hospital where he underwent a major operation. The four works he painted in this short time, each on a fresh canvas, are the only works connected with this location, and they have something in common. They are simple, and they are vertical. One, called Nude, was an enlarged version of a composition he’d made the year before, the other three were different versions of the same image, which he called Charred Beloved.

27

MATTHEW SPENDER

The canvas titled Nude was probably painted first. It derives from an illustration which Gorky had made for a book of poems by André Breton the previous summer. The composition is simple, because the book was small. Producing twenty perfect copies of the same image was difficult, but it meant that by the time he began the “ballroom series,” he knew this composition by heart. After he’d settled in, it was a question of transferring this composition once, perfectly, onto a pristine canvas.

After 1941, Gorky often divided his time between phases when he drew from the landscape and phases when he painted from these drawings in the studio. Drawings were made on the spot—sur le motif—in the countryside of Virginia, where he spent the summers on his in-laws’ farm. From an initial still recognizable composition, Gorky would make a second drawing, using the first as a launching-pad. “When he works from nature there is always great truth in what he draws, you feel the search & it cannot fail to communicate something—when he draws from memory at night or on rainy days the drawing is perhaps more bold but tends to be more ART… There is less truth, though often it makes a finer drawing.”2 The ballroom series falls in between two such phases. In 1945 he’d lived in Connecticut painting canvases from drawings made in Virginia in 1944; and in 1947 in New York he painted canvases from drawings he’d made in Virginia in 1946. The Nude and the three paintings of Charred Beloved fall between these two periods, and they are distinct from both.

In almost all of Gorky’s late work there is an underlying feeling for the landscape, however abstract the final composition may be. There’s an imaginary horizon, a feeling of distance. In his work of the midthirties, however, the composition lay much closer to the surface of

28 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

“In almost all of Gorky’s late work there is an underlying feeling for the landscape, however abstract the final composition may be.”

29

Kathrin & Walter Hochschild Residence at 1200 Fifth Avenue, New York, 1930s. Courtesy of the Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

30 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

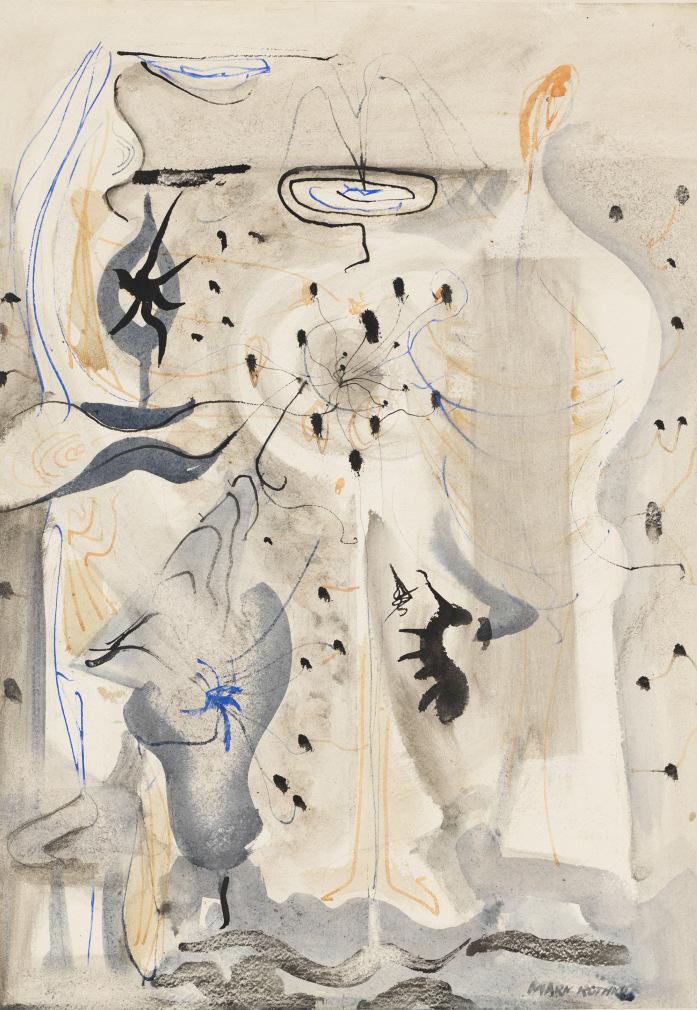

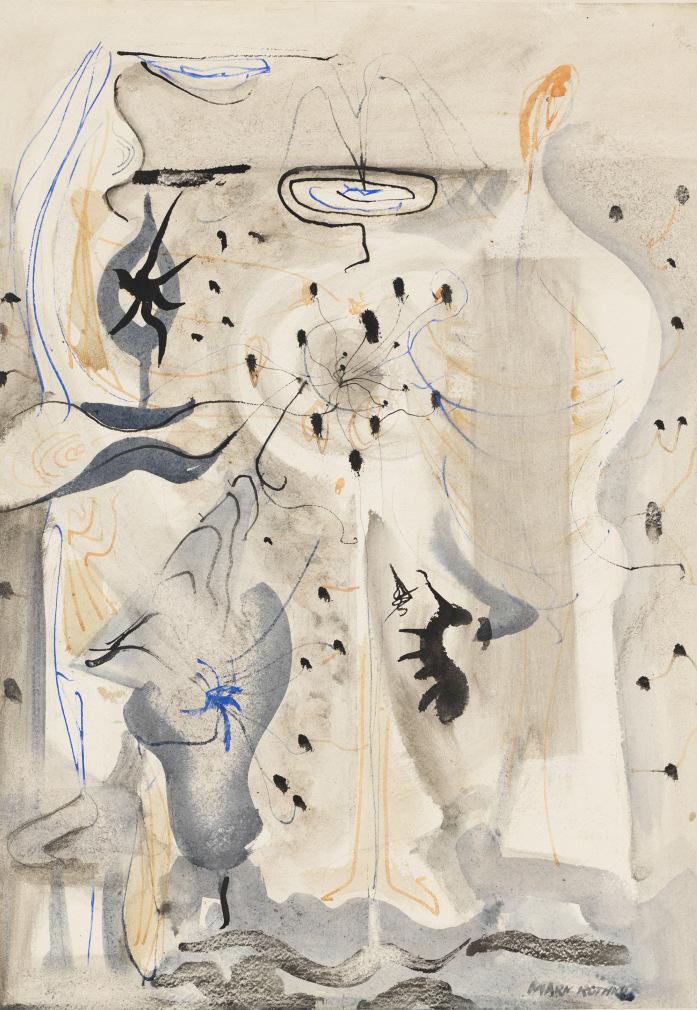

Mark Rothko, Archaic Idol, 1945. Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2023 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Photo: © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

The first buyer of Charred Beloved No. 1, Kenneth MacPherson, loaned Rothko’s Archaic Idol to his 1946 exhibition at Mortimer Brandt. And both artists exhibited works at the Whitney Annual of that year.

Arshile Gorky, Anatomical Blackboard (D1014), 1943. Private Collection.

Photo: Jerry L. Thompson. © The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society, New York.

the picture-plane. Then, Gorky was interested in the “elevation of the object.” It was “the marvel of making the common, the uncommon.” In a composition, “through the denial of reality, by the removal of the object from its habitual surrounding, a new reality was pronounced.” In the ballroom series, the image lies flat on the surface. The paint is immediate, it does not hint at recessive space. It’s a return to a kind of painting he had otherwise laid aside.3

For a while during the mid-forties, there’s a fascinating overlap between the work of Arshile Gorky and that of Mark Rothko. Both artists were struggling to incorporate the Surrealist process of “automatic drawing” into their work. A major exhibition of Surrealist art in New York in 1936 had launched the idea, but understanding automatic drawing required learning directly from the European Surrealists, who only arrived in New York after the outbreak of the Second World War.

A key actor in this development was the young Surrealist painter Roberto Matta, who arrived from Paris at the end of 1939. For a few months after he’d moved into a new apartment in October, 1942, Matta opened his studio every Saturday to a small group of New York artists. He showed them how automatic drawing was made. It was not so much a way of finding an image, but a path “to show the functioning of the mind.”4

Neither Gorky nor Rothko attended these meetings, but Matta was communicating privately with Gorky at this time. A painting such as Waterfall (P259) would never have been made if Gorky had not benefited from Matta’s extraordinary gift for transmitting ideas, and it’s possible that this particular painting influenced Rothko’s development in the mid-forties. To Robert Storr, there is no doubt.

“Without the precedent of Gorky’s Waterfall (1943), The Pirate I (c. 1942-43), and drawings such as Anatomical Blackboard and Study for ‘The Liver is the Cock’s Comb’ (both 1943), Rothko’s works would have been nearly unthinkable.”5

31

At the time he began to paint the ballroom series, Gorky had known Rothko for twenty years. In 1925, he’d been a young instructor at the New School of Design which Rothko briefly attended. “It was part of his job to lecture to us and expound on the techniques used by the artists hanging in the Metropolitan,” Rothko said later. He visited Gorky in his studio on Union Square, remembering one particular occasion because Gorky had asked him to take down the trash. “I also saw him periodically at parties, openings of exhibitions and at art galleries. We weren’t close, but I’d occasionally run into him at events like that.”6

If this sounds distant, it probably was. “Gorky had a role in mind that he played, but Rothko was hypnotized by his own role and there was just one,” Elaine de Kooning recalled. “The role was that of the Messiah—‘I have come. I have the word.’ I mean, Rothko had a very healthy self-worship and he did feel that he had discovered some great secret. He felt that this was of universal import. Gorky in one way seemed more arrogant, but on the other hand, Gorky also had streaks of humility. He had tremendous reverence for other artists.”7

In other words the two men had their art, and they also had an idea of the artist who’d created that art, and this was as much of a creation as the art itself. And these two personae were incompatible.

In the mid-forties—ignoring for a moment the question of dates— there’s a curious ebb and flow in the imagery of the two artists. This derived from their shared interest in automatic drawing and in the surface of the canvas. But there was no overlap in their ultimate aims. In his last great output of canvases painted in 1947, Gorky returned to a feeling for the landscape, and even for the human figure—a reversion to an iconography which at that time Rothko was struggling hard to abandon.

In the early forties, Rothko had written a book about art, including a long discussion about his idea of the “myth.” It reached the stage of a typescript but it was not published during his lifetime. The artists

32 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

33

Mark Rothko, Baptismal Scene, 1945. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

© 2023 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Photo: © Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala / Art Resource, NY.

This work was exhibited in the Whitney Annual of 1946. Gorky showed Anatomical Blackboard in the same exhibition.

The resemblance between these two drawings is coincidental, yet they are connected. Each artist uses lines parallel to the sides of the paper to emphasize composition, each hones in on small details to create drama. They are both exercises in “automatic drawing” according to Surrealist principles.

34 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

Arshile Gorky, Untitled (D1310), circa 1946. Private Collection. © 2023 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Photo: Antonio Carloni.

Mark Rothko, Untitled from Vernon Line Composition Book, 1946-1952, page 104. National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. © 2023 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

of the Renaissance were interested in allegory, he said, but this led them towards anecdote. They became distracted by the sensuality of representation. “In our hope for the heroic, and the knowledge that art must be heroic, we cannot but wish for the communal myth again.” What was needed was “the likeness of reality as an end in itself.” The myth is a feeling, not an illustration. “This, then, is the new myth. The unity is no longer a fact to be described by an anecdote but instead is an abstraction of status, to be intimated and depicted.”8

On June 7, 1943, Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb wrote a letter to The New York Times. “We favor the simple expression of the complex thought. We are for the large shape because it has the impact of the unequivocal. We wish to reassert the picture plane. We are for flat forms because they destroy illusion and reveal truth.” This is a concise summary of Rothko’s book, and it received considerable attention then and later.

Matta, in his conversations held over the winter of 1941-42, had also talked about the “myth,” but he was utterly opposed to Rothko’s ideas. He saw these as a pointless re-hash of ancient clichés. To Matta, the “myth” involved Native American culture plus Einstein. “America” was not a noun but a verb which animated all it touched. The revolution of Einstein says that space is curved, everything is relative to everything else, there are no straight lines. This was where the future of American art would lie. To become involved with ancient myths was not “new,” it was “old-new,” and thus a useless distraction.9

Rothko and Gorky, though they run parallel, are opposites. Gorky’s work is in a constant dialogue with European art, including the geometric rules for depicting recessive space. He was also interested in distilling something from nature, whereas Rothko wanted something entirely new. Rothko’s art starts with an emotion, a transcendental presence that proceeds and dominates the imagery by which this feeling is conveyed. Yet at this particular moment of the mid-forties, in the ballroom series and especially in the three versions of Charred Beloved, Gorky for a moment looks forward to an imagery that Rothko only found later. In this work Gorky has provided an emblem, a space that comes forward instead of receding, a shield.

35

38 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

GORKY’S ORIGINALITY

JOHN ELDERFIELD

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

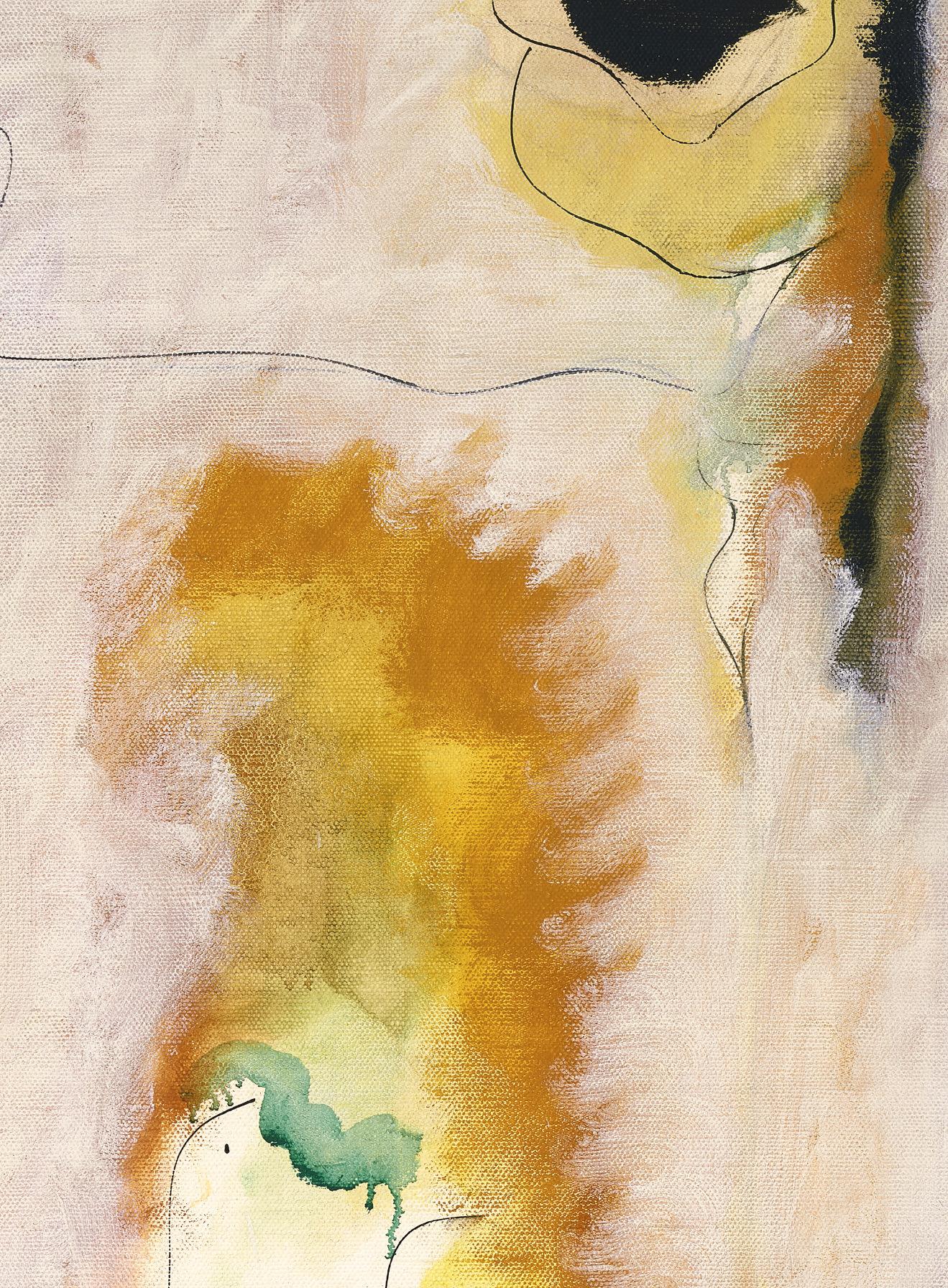

Charred Beloved I is one of a trio of paintings of this name and format that Arshile Gorky made in the Spring of 1946. Their title memorializes the more than twenty of his “beloved” canvases destroyed in January of that year in a fire in his Sherman, Connecticut studio, along with many drawings and his cherished library. As it would turn out, these three paintings came at the center of the final, climactic period of his life, just two years before his tragic death by suicide. This being so, they invite— and support—interpretation in terms of Gorky’s troubled life; and I shall say something on this subject shortly. However, it is important not to pathologize these extraordinary paintings. They do address a difficult subject; yet they belong to a tradition of such works whose pictorial electricity makes them so commanding as to make us pause and wonder what it is they are telling us.

39

“Every author, as far as he is great and at the same time original, has had the task of creating the taste by which he is to be enjoyed… The predecessors of an original Genius of high order will have smoothed the way for all that he has in common with them… [but] for what is peculiarly his own, he will be called upon to clear and often to shape his own road.”

The other two Charred Beloved canvases, being dark and smoky in appearance, withhold themselves, asking us to peer into them as if reprising the artist looking into his studio on fire. In contrast, Charred Beloved I arrests and attracts us at first glance—au premier coup d’oeil, as French nicely describes it, rather, as an image so vivid that it instantaneously travels and hits the beholder’s eye. But it especially is slow in revealing itself. As it does so, it seems fair to say that we realize we are in the presence of one of the earliest and most original of the extraordinary paintings made in America at the middle of the twentieth century.

MUTATION AND METAMORPHOSIS

Among the extraordinary aspects of Charred Beloved I and the paintings that Gorky made contemporaneously with it, is that they come at the end of a long process of continual discovery of his selfidentity as an artist. It will be useful for what follows to be reminded of at least the salient landmarks in Gorky’s process.10

In 1908, four years after Vostanik Manug Adoian was born in what is now eastern Turkey, his father abandoned his family and emigrated to the United States: The Ottoman-Turkish Government’s genocide of its non-Muslim Armenian citizens, which had begun in the latter part of the nineteenth century, had accelerated, endangering men of a military age. By 1915, the process of ethnic cleansing had killed some quarter of a million Armenians; the population of entire towns executed; women and children savagely brutalized. Gorky’s immediate family was among the thousands then forcibly resettled outside the country. With humanitarian aid blockaded by Ottoman Turkey, Gorky’s mother starved to death in 1919 and, like the many others who suffered this fate, was buried in a mass grave. The following year, unexpectedly aided by family friends, Gorky was able to escape to the United States.

40 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

42 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

Gorky painting at his Sullivan Street studio, New York, circa 1927. Photographer Unknown.

It is impossible to know what an early childhood like this could have imprinted on Gorky’s mind; but the many who have written perceptively about his art acknowledge that its traumatic memories never left him. At the same time, once Gorky was in the United States, at around age sixteen, he began to bury them in the creation of works of art: Almost immediately, he began using paintings he saw in books and museums as the subjects of his own paintings—in the spirit of an immigrant learning a new language.11

He also buried his past by discarding his Armenian birth name, claiming to be a relative of the Russian writer Maxim Gorky. His career as an artist was also one of changing identities: Beginning in the late 1920s, he made paintings in close imitation of works by Cezanne, often not signing them with his own name. Then came paintings in imitation of Picasso—until, in the words of the most careful observer of Gorky’s progress, critic Clement Greenberg, he “submitted himself to Miró in order to break free of Picasso;” next, “Kandinsky was even more of a liberator;” until “again he submitted his art to an influence, this time that of Matta y Echaurren, a Chilean painter much younger than himself.”

43

“…we are in the presence of one of the earliest and most original of the extraordinary paintings made in America at the middle of the twentieth century.”

Gorky was following the path that T.S. Eliot had famously commended, writing in 1936, “A poet cannot help being influenced, therefore he should subject himself to as many influences as possible, in order to escape from any one influence. He may have original talent: but originality has also to be cultivated; it takes time to mature, and maturing consists largely of the taking in and digesting various influences.”12 The question, of course, is how to listen and learn from others’ voices while speaking in a voice of your own.13 As late as 1945, Greenberg was one of those wondering whether Gorky had found his own voice, writing that “he has had trouble freeing himself from influences and asserting his own personality.”14 But Gorky’s 1946 exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery, which included two Charred Beloved paintings, began to change the critic’s mind. His mea culpa read: “This writer once made the mistake of thinking Gorky a slave to influences—first Picasso’s and Miró’s, then Kandinsky’s and Matta’s. These influences were indeed there, but the error was in seeing them as something obeyed rather than assimilated and transformed.”15

What had happened to change Greenberg’s mind? He said it was because, as an artist’s work “becomes more familiar, it slowly becomes apparent that the resemblances that used to bulk so large have somehow—incomprehensibly—shrunk and lost their scope and importance, and that the main point of the art in question has become precisely that which is individual about it. This, rather than the resemblances, is now all we can notice.” I am not sure that this suffices. I think we still see the resemblances.

A fine literary critic, Northrop Frye, asked us to consider the difference between how art is reshaped from its own depths by greater and lesser artists: “through its geniuses for metamorphosis… through minor talents for mutation.”16 It seems fair to say that Gorky’s versions of Cezanne’s, Picasso’s, and even Kandinsky’s paintings are mutations of the works he was looking at. But, strange though it may seem at first, as the influences accumulated in each one of his paintings, mutation gave way to metamorphosis. It is common to judge that artistic maturity is

44 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

only achieved when influences are so fully absorbed as to resist their enumeration. Gorky’s remain identifiable; and to Greenberg’s list we should add the anthropomorphic rock formations of Yves Tanguy. In style as well as in subject, Gorky could long have agreed with Ovid, who opened his famous anthology of mythological stories, Metamorphoses, with: “Changes of shape, new forms, are the theme which my spirit impels me now to recite.”17 But with respect to style, part of the power of his mature art is precisely in that his influences are not fully absorbed. Rather, they function as the comingled vehicles of a truly unusual form of pictorial imagination.

As curator Michael R. Taylor explained in by far the best account of the components of Gorky’s “mature style,” they “helped to unleash images from the depths of his fecund imagination and tragic personal history, leading to the creation of some of the most hauntingly beautiful works of art of his time. Or any other.”

If we can bring to mind this range of Gorky’s stylistic influences, we will see that, among the Surrealist ones, he stripped mere playfulness from what Taylor called “the whimsical associative form-language of Miró”; anything boisterous from “the exuberant automatism of Masson”; all the gooey quality of “the melting mineral dreamscapes of Matta.” The “anthropomorphic rock formations of Tanguy” are beautifully mirrored in the Charred Beloved paintings. And yet, his work separates itself from the long tradition of anthropomorphic landscapes, showing figures hidden within rocks or woodland. Hackneyed versions persisted, notably in Pavel Tchelitchew’s famous Hide and Seek of 1940-42, acquired by The Museum of Modern Art shortly after its completion. Gorky does invite us to experience

45

“[Gorky] shows himself as one of the great painters of his time and among the very greatest of his generation.”

CLEMENT GREENBERG

“changes of shape, new forms,” in the process of our viewing, but not in a hide-and-seek switching back and forth of reversible figures. Moreover, most of his drawn descriptions are undecipherable.

As for Kandinsky’s influence, it may seem an unnecessary renunciation for Gorky to have avoided the illuminated backdrop quality of that artist’s great early abstractions. However, what replaces it, we see in Charred Beloved I, is more radical: a cool grisaille with the quality of a radiator warming up. Everything is assimilated and transformed.

Greenberg reprised Wordsworth in summarizing the result: “We have had to catch up with Gorky and learn taste from him; he was one of those artists who had by themselves to form and extend our sensibility before they could be sufficiently appreciated. And we now see that he did do this… he shows himself as one of the great painters of his time and among the very greatest of his generation.”18

METAMORPHOSIS AND HYBRIDITY

Gorky painted his three Charred Beloved canvases in a makeshift studio in a ballroom on the seventeenth floor of a building at 1200 Fifth Avenue at 101st street overlooking the North Meadow of Central Park and just north of the Reservoir. Two of them, but not this work, would be exhibited at an exhibition of Gorky’s paintings and drawings of 1946 at the Julien Levy Gallery, New York in April-May of that year. Matthew Spender, one of Gorky’s biographers, tells us that he worked in the Fifth Avenue studio for only two or three weeks, and observed that the versions of Charred Beloved and Nude, also made there, “are among the simplest designs Gorky ever made.”19 This is true, and yet they are not simple paintings. He did speak of wanting something less “finished” than before, saying “I don’t like that word ‘finish.’” The reason, though, was: “When something is finished, that means it’s dead, doesn’t it? I believe in everlastingness.”20 The natural world, as he pictured it, had to be the very opposite of a dead still life; seemingly imperishable.

46 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

47

Kathrin & Walter Hochschild Residence at 1200 Fifth Avenue, New York, 1930s. Courtesy of the Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

48 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

Arshile Gorky, Drawing for Charred Beloved (D1203), 1946. Collection of Sally and John Van Doren. © 2023 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Photo: Alise O’Brien Photography LLC.

The paintings destroyed in the Connecticut studio fire appear to have been mainly heavily reworked canvases that Gorky had made and remade.21 Those painted in New York reflect, in Greenberg’s words, the abandonment of “his customary heavy, flat impasto… to rely on the draftsmanship that has become his most powerful and original instrument.”22 He added: “Thin black lines, tracing what seem to be hidden landscapes and figures, wind and dip against transparent washes of primary color that declare the flatness of the canvas.” Gorky was now using a “liner,” a thin-bristled sign-painters brush, which de Kooning supposedly had introduced to him.23 This “tracing” does indeed “wind and dip against transparent washes” across the surface. However, these washes are rarely of a primary color; more often of variegated grays or, here, in pink-beige. And they may “declare the flatness of the surface;” but they also model a shallow depth within as well as against which Gorky disposed his black lines in their winding and dipping movements.

Greenberg spoke of the black lines as tracing hidden landscapes and figures; not landscapes or figures. The tracings resemble threadlike, leafless tendrils, but also subcutaneous fibrous tissues like ligaments and tendons. And the vertical format of the Charred Beloved canvases, customary for portraits, encourages their reading of nature as embodied, especially when we remember that his Nude was made along with them and shared their composition.

Earlier, I suggested that Gorky could long have said with Ovid, “Changes of shape, new forms, are the theme.” An essay by art historian David Anfam on Gorky’s summer 1946 paintings, canvases that followed those discussed here, is titled “Metamorphoses” and takes as its motto Ovid’s statement of intent. He is correct in claiming that “Gorky’s art followed a transformative typology established as far back as the classical storyteller Ovid.”24 But with an important qualification: Ovid’s narrative art allowed him to unfold the sometimes-lengthy

49

“When something is finished, that means it’s dead, doesn’t it? I believe in everlastingness.”

ARSHILE GORKY

stories of the process of a metamorphic transformation. A visual art is limited to showing either its result or a moment in its development: The classic example of the former is, of course, the many images of the climax of the story, in Book Ten of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, of the transformation of the sculptor Pygmalion’s statue of a perfect woman from marble into human flesh. The latter has one great illustration— the nymph Daphne in the process of being changed into a laurel tree, as told in Book One of Ovid’s stories—in the youthful Bernini’s sculpture at the Borghese Gallery in Rome. The “wonder reaction” produced by that image of the process of metamorphosis, stopped for us to see, is simply without parallel.

Charred Beloved I catches something of the same thrill of suspended animation, which is more properly described as a vision of hybridity rather than of metamorphosis. As the art historian Caroline Walker Bynum explains, “Metamorphosis goes from an entity that is one thing to an entity that is another. It is essentially narrative.” She adds, “It is about a one-ness left behind or approached. In contrast, hybrid is spatial and visual, not temporal. It is inherently two.” A state of hybridity is “not just frozen metamorphosis” but “a double being… [and] an inherently visual form.”25 This is to say, it can be pictured to show two in one.

Aided by comparison with Nude, we may see the oblique, distorted rectangle drawn by thin black lines at the top left of Charred Beloved I as perhaps depicting a mirror. And yet, it attaches to an outlined falling shape, suggestive of an arm with a hand or clenched fist at its base. If we admit that suggestion, we may also allow that the single, looping filament that Gorky attached to the top of this feature— stretching to the left edge of the painting—somewhat resembles the neckline of a garment. Whether or not we are ready to go so far, I think it is consistent with his practice to view as corporeal the shapes that fall down from the center of this line, and that increase in size and distortion as they turn and spread across the bottom of the painting.

50 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

51

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Apollo and Daphne, 1924. Galleria Borghese, Rome.

Photo: Andrea Jemolo / Scala / Art Resource, NY.

52 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

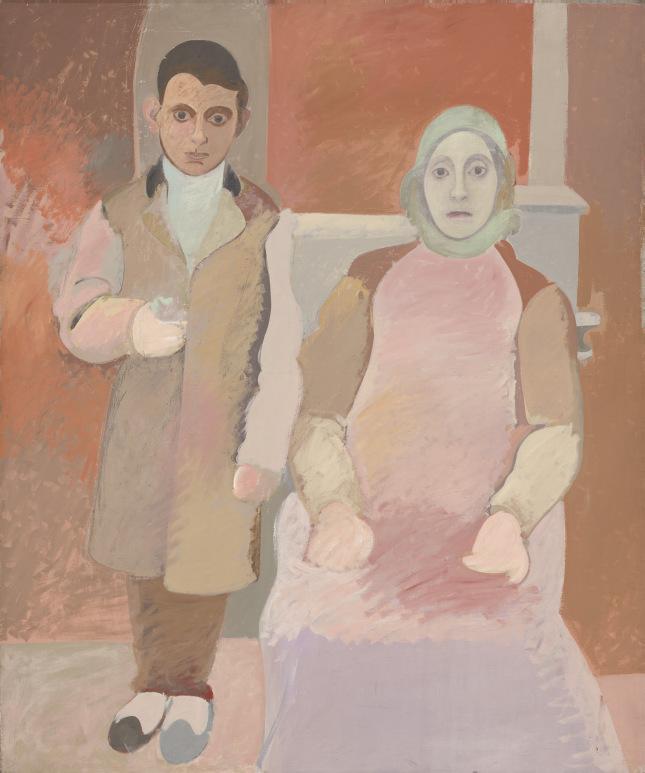

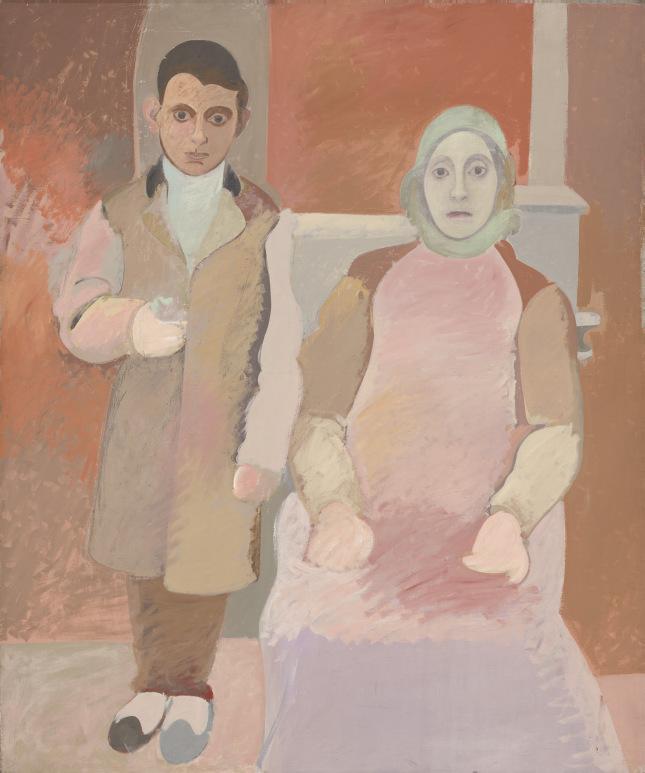

Arshile Gorky, The Artist and His Mother (P114), circa 1926-1942.Photo: National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. © 2023 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: National Gallery of Art.

Whether or not we associate the black and red passages within the lower part of this large horizontal form as bruising and wounding, and whether to think of the form itself as part of the surface or of the interior of the body, it is hard to dispute that the embodiment of form was, whether consciously or not, Gorky’s intention. Also, that his pictorial understanding of such embodiment recalls a famous statement of 1923 by Sigmund Freud: “A person’s own body, and above all its surface, is a place from which both external and internal perceptions may spring. It is seen like any other object, but to the touch it yields two kinds of sensations, one of which may be equivalent to an internal perception…”26 Some of how Freud modified this statement four years later may be judged especially relevant to Gorky, given his early history: “Pain, too, seems to play a part in the process, and the way in which we gain knowledge of our organs during painful illness is perhaps a model of the way by which in general we arrive at the idea of our body.”27 In Charred Beloved I, the proximate aliveness of the painting’s surface, substituting for that of a human epidermis, and seeming to have a pulmonary quality to it, invites imagination of the vivacity of flesh beneath and, within it, of the body’s sentient aliveness.28

Just below the “neckline” feature in Charred Beloved I, there is a strange three-part feature comprising a shallow black concavity beneath a red stem beneath a dark spreading shape. Aided by comparison with the other two Charred Beloved canvases, we may see this as something supported by a cupped hand. And comparison especially with Charred Beloved No. 2 allows that Gorky thought of including a second standing figure to the right, only to have shown it in Charred Beloved I by form dissolved and dissolving, dripping down the surface leaving stains and sediment. Taken together, the two associations gain a particular significance: We know that from around 1926 to around 1942 Gorky was painting images of himself, holding a bouquet of flowers, and his mother, wearing a headscarf and a flowered silken pinafore dress, based on a photograph of them together taken in

53

“Charred Beloved I catches something of the same thrill of suspended animation…”

Armenia in ca. 1912 when he was around ten years old.29 And we know that this prized photograph was one of the things that Gorky rescued from the fire in his studio in 1946.

The latest of these compositions, in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., is commonly thought to have been completed—or abandoned—in 1942, just four years prior to his making the Charred Beloved paintings. I do not suggest that Gorky consciously, deliberately made his Charred Beloved paintings to form a coda to his The Artist and His Mother works, reshaping their compositions with the aid of hidden imagery. But we may reasonably conclude that that memory of this theme, speaking of his lost homeland, was in his mind after the loss of his studio.

Art historian Kim Servant Theriault, who wrote movingly about Gorky’s The Artist and His Mother compositions, points out that “the lack of the solidity in the forms of the National Gallery painting exploits Gorky’s belief in the mutability of natural forms and his tendency to dislocate them within the space of the canvas.”30 She adds that Gorky has expunged details—for example, making the flowers in the boy’s right hand almost unrecognizable—and that the mother’s face, “drained of expression, betrays loss—of individuals or homeland— and perhaps reflects death.”31 If we are ready to see the Charred Beloved paintings as continuous with The Artist and His Mother compositions, we will recognize their further development of the qualities that Theriault describes. She speaks of Gorky’s “in-between state” as an artist in exile, trying to remake his identity and forget his trauma by “the working through of his dislocation, disjuncture, and displacement.” To put this differently, he knew that he could not change from being one person to being another, but he could be a double being. This is mirrored in his art: metamorphosis was not possible; only hybridity, which is what holds the Charred Beloved paintings in their in-between states—neither images of landscape nor of the figure, but both; neither images of surfaces nor of interiors, but both; neither abstract nor representational, but both; neither beautiful nor sorrowful, but both.

54 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

Despite the present numbering of the three paintings, the sequence in which they were painted is unclear. Two were exhibited at the Julien Levy exhibition as Charred Beloved No. 1 and Charred Beloved No. 2. This does not prove that the present painting was made third, although it may well have been; only that Gorky withheld it from his exhibition. It is very different to the other two, which do seem to form a pair. Initially seeming melancholic and elegiac, they transform in their viewing to invoke something akin to the primordial “entangled bank” of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species, “clothed with many plants of many kinds… various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that that these elaborated constructed forms, so different from each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us.”32 Such a description also applies to the teeming biology of Gorky’s big late horizontals; how his art is often as much Darwinian as Ovidian is a subject awaiting discussion. The work now titled Charred Beloved I is more Ovidian than Darwinian.

Although the sparest, it is more complicated thematically and more original than the other two. It is reported that, after walking into his new, temporary studio, “he says it is all inside him, the painting on his easel. The one he was working on during the fire is still burning in his mind & he only wants to get to work immediately.”33 And later, that he felt “a new freedom from the past now that it is actually burned like you feel when you are young and there is no past.”34 Is he saying that he was feeling free of his traumatic past, which had been burned along with his Connecticut studio? And, if so, that this was a feeling he had not yet found when painting the other two, darker canvases? Or that it came and went, going from light to dark, or dark to light?35

55

“But it is fascinating that he withheld [Charred Beloved I] from his Julien Levy exhibition. Did its novelty perhaps perplex him?”

But it is fascinating that he withheld the light canvas from his Julien Levy exhibition. Did its novelty perhaps perplex him? It recalls Henri Matisse’s choosing, probably for that reason, not to illustrate in a survey of his recent works—then release neither for exhibition nor sale—the more radical of his two 1914 paintings, View of Notre Dame.36

I began by quoting the poet Wordsworth. He famously said that “Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings; it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.” Another poet, and great critic, Eliot, demurred, saying: “For it is neither emotion, nor recollection, nor without distortion of meaning tranquility. It is concentration, and a new thing resulting from the concentration, of a very great number of experiences which to the practical and active person would not seem to be experiences at all.”37 The power of Charred Beloved I lies in such concentration. Gorky spoke on occasion of his inspiration in the close-up inspection of nature: “You see, these are the leaves, this is the grass. I got down close to see it.”38 Charred Beloved I was painted from some 150-feet in the sky—which may be an unprecedented height for an artist’s studio—looking down onto the North Meadow of Central Park and very far from Darwinian entangled banks. I do not think it is amiss to conclude that this may have encouraged his simplification of nature in isolated anthropomorphic images, as if caught in suspended animation by distant viewing. In any event, its concentration seems less of experiences recollected, as those distant and distilled.

It also speaks of another kind of distant and distilled experience. I have spoken of Gorky’s originality, and it seems fair to say that he had made himself the most original painter among those called Surrealists, and among the most original of his generation. What is inescapable, though, is that his originality owes a lot to his continuing sense of his own origins. He could well have said with another, later troubled painter, Philip Guston, “I’m afraid, if my devils are to leave me, my angels will take flight as well.”39 A part of the force of Charred Beloved I is how a massive atavistic anxiety and a desire for calmness appear to live in it with each other—and a greater part may be the wonder it produces.

56 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

57

Henri Matisse, View of Notre Dame, 1914. Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2023 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Photo: © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

Copyright © 2023 by John Elderfield.

60 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

MOONLIGHT

JED PERL

A year or so after he finished Charred Beloved I, Arshile Gorky suggested to a friend that there were two kinds of painters: sun painters and moon painters. Ethel Schwabacher, who wrote an important book about Gorky, had come upon the artist standing in front of a canvas by Vermeer in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Vermeer,” Gorky explained to her, “is not a sun painter, but rather a moon painter—like Uccello—that is good, it is the pure, final stage of art, the moment when it becomes more real than reality.” Charred Beloved I is a moon painting. This enigmatic canvas, with its shimmering hieroglyphs, is full of light. But this isn’t daylight. It’s an indirect light. It’s moonlight. Or an abstraction of moonlight.

The strokes and counterstrokes of pale violet pigment that fill Charred Beloved I end-to-end set the stage for a midsummer night’s dream—a moon painter’s dream. And the vertical orientation of the canvas, less common in Gorky’s later work than the horizontal formats that inevitably evoke a landscape, draws us into that dream, invites us to look up, to an antigravitational realm. Apprehensions and experiences are untethered. There’s something of the spirit of the old Chinese painters, who loved a vertical format and knew to stop before they revealed too much. Whatever we see in Charred Beloved I—a line, a shape, a color—is unique, an event unto itself. Consider the burst of soft, inky black in the distant upper right, as inscrutable as the stain on a wall that Leonardo da Vinci believed might offer an artist some inspiration. That black shape is rising—and escaping the painter’s enclosing rectangle.

61

Gorky will not decide a form’s fate. His compositions, casually but purposefully arranged, have some of the fascination of drafts or rehearsals. He’s constructing a private cosmology—impossibly ambitious, forever unfinished and unfinishable. There are matters, so Gorky suggests, that are beyond a painter’s control. His title, Charred Beloved I, memorializes the horrific fire in his Connecticut studio that had left much of his recent work burnt beyond recognition. There’s a ferocity about this title; it startles me. The title introduces an autobiographical dimension into a painting that yearns for the epical, the mythological. The title can’t help but remind us that the painting’s halcyon beauty—any painting’s beauty—is hard fought, hard won. Charred Beloved I was one of three paintings to which Gorky gave the same title and the same composition. If Charred Beloved I is a moonlit moment, then the other paintings, with their dominant grays and blacks, disclose equally but differently challenging aspects of the nighttime world.

But I risk making Charred Beloved I sound more literal than it is. Gorky’s metaphors refuse to stand still. They decompose. They recompose. He’s less interested in certainties than uncertainties. His forms hover between animal and vegetable and mineral and the purely Platonic—and then, when we’ve settled on a meaning, Gorky defeats our speculations by reminding us that what we are seeing is the beauty of paint on canvas, nothing more, nothing less. The light may or may not be moonlight. What’s certain is that it’s painted light. Looking at Charred Beloved I, I’m tempted to describe the single meandering stroke of thin green paint as snakelike. But it isn’t a snake. As for the strong horizontal blast of red, I see that it’s echoed or accompanied by a much smaller vertical stroke of red. The relationship between these two reds has a prelapsarian immediacy.

Nothing in Charred Beloved I is more singular and more ambiguous than the plant or bone shape that Gorky has drawn, lightly overpainted, and redrawn. This is less a shape than an invocation

62 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

“The title can’t help but remind us that the painting’s halcyon beauty... is hard fought, hard won.”

63

Johannes Vermeer, Allegory of the Faith, circa 1670. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY.

64 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Madame Jacques-Louis Leblanc, 1823. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY.

of a shape; the magician pulls back the curtain and allows us to see how he does what he does. I am reminded again of something that Gorky said to Schwabacher, when they were looking at a portrait by Ingres in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Yes, the surface of the painting is smooth, finished and incorruptible as a diamond, but under the accomplished surface are pentimenti—see there at the shoulder, how the line of the black dress was lowered a fraction and the hand was extended to give greater elegance.” The revisions of the plant or bone shape in Charred Beloved I suggest both the yearning for the “accomplished surface” and the necessity of the pentimenti, without which the painting can never be as “incorruptible as a diamond.”

Darkly handsome, quietly charismatic, and burdened with a melancholy that his extraordinary energy and charm could never defeat, Gorky was a man who refused to fit in. There’s a quality in his work, definitely in Charred Beloved I, that draws us back, at least draws me back, to the romantic optimism and free-spirited symbolism of European culture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I find echoes of art nouveau’s dreamy arabesques in Gorky’s unfolding, unfurling, meandering lines—and something of the music of Debussy, Ravel, and Satie’s Gymnopédies in Charred Beloved I’s insistent evanescence. There’s no question that Gorky learned a great deal from Cezanne’s hesitating, questing, furiously intelligent strokes of paint. And however profound his exploration of Picasso’s hard-edged distortions, I suspect that what Gorky loved most in Picasso was the delicacy of the Rose Period and the intrepidness of his neoclassical lines, those reincarnations of Ingres’s incorruptible surfaces.

Gorky’s gracefulness, so much on display in Charred Beloved I, brings to mind not the shock tactics, hyperbolic comedy, and scabrous irony cultivated by the poet André Breton and Gorky’s other supporters among the Surrealists of the 1940s, but the poetry of an earlier period in the great modern adventure. I’m thinking of T.S. Eliot’s “whispering lunar incantations” and “violet hour,” Ezra Pound’s “petals on a wet, black bough,” and, from another poem by Pound, one dedicated to the American painter James McNeill Whistler, this stirring line: “You had your searches, your uncertainties.” So Gorky did. Charred Beloved I is all searches and uncertainties, but pursued with a steadfastness that turns searches into discoveries and uncertainties into certainties.

65

68 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

FROM THE ASHES

HAYDEN HERRERA

In 1946, soon after a studio fire destroyed much of his recent work, Arshile Gorky painted three versions of Charred Beloved. Charred Beloved I is tender and elegiac. There is a lightness to it, a sense of possibility. But, as always with Gorky, hope is tinged with melancholy. This version is much more colorful than its sisters. Yellow, orange, and red burst through an ash-gray ground. It is also the most richly textured. A layer of red pigment pulses beneath a scumbled gray background that sometimes submerges and sometimes forms the body of shapes. A bright red slash framed by white and floating above smudges of black could be a cry of joy or pain. To me it says “Yes!” Like hot coals under cinders, Charred Beloved I glows from within.

In the other two versions, forms float in liquid charcoal—a sort of sfumato of the conjuring mind. Sometimes forms half disappear behind the transparent black-gray wash that changes in density and darkness like clouds amassing before a storm. In Charred Beloved No. 2, areas of white where the canvas has been left unpainted can be seen as light promising to break through clouds. The remaining version is somber. Whereas Charred Beloved No. 2 has accents of red and yellow, Charred Beloved No. 1 is colorless except for a thin red line that, as in Charred Beloved I and No. 2, connects a bird’s head shape (a favorite Gorky motif) with the biomorphic form below.

69

These three paintings have a story, but they do not tell it. As Gorky insisted, “I never put a face on an image.” What they allude to is the first of the catastrophes that embittered the last two years of Gorky’s life and that sharpened the despair that led to his suicide in 1948. On January 16, 1946, a potbellied stove that Gorky had recently installed too close to a wooden beam in his Sherman, Connecticut studio ignited a fire that burned the building to the ground. At first, he thought the smoke came from his cigarette. When he saw flames licking the roof, he panicked. As his wife, Agnes (called “Mougouch”) recalled, in moments of crisis Gorky acted like a donkey. Instead of calling the fire department, he walked up to the main house that he and his family were sharing with the homeowner and fetched a pail of water. Back and forth he went, carrying water to the fire. He passed the homeowner each time, but was too ashamed to tell her what was happening. Finally, she asked and he mumbled, “studio on fire.” She called the fire department. Neighbors and volunteer firemen came, but it was too late. Gorky rushed into the smoke-filled building and shut the door behind him. When his friends hauled him out, he lay on the ground weeping and banging his head against the earth. He’d lost all his work, he said. In fact, he did manage to salvage a hammer, a screwdriver, a box of charcoal, a few canvases, and the photograph of himself at around age twelve standing beside his mother in Van City in Ottoman Turkey.

Gorky’s chaotic behavior may reflect his belief that he was cursed. After the Turks nailed his grandfather, an Armenian Apostolic Priest, to his church’s door and when five years later, Kurds or Turks murdered his uncle, his maternal grandmother took her revenge against God and set fire to the family’s ancestral church. Her blasphemous act brought a curse on her descendants. “I am a man of fate,” Gorky once said. Fire became a leitmotif in his life. “I think,” he wrote, “our lives flow like a molten lava.”

70 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

“A bright red slash framed by white and floating above smudges of black could be a cry of joy or pain. To me it says ‘Yes!’”

72 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

Arshile Gorky, They Will Take My Island (P288), 1944. Art Gallery of Ontario. Toronto. Purchased with assistance from the Volunteer Committee Fund, 1980. © 2023 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: © Art Gallery of Ontario.

Two hours after the fire had been put out, Mougouch, who was in New York City seeing her dentist, spoke with Gorky over the telephone. His voice sounded so hollow that she dreaded the anguished state she was sure he would be in when they met in the city the following day. To her astonishment, Gorky was elated. “He was not dejected at all. There was an element of relief…” He told her that the painting he had been working on when the fire broke out was burning inside his head. “It’s all right. I’ve got it all inside me. I can go on painting.” Mougouch wrote to a friend, “Gorky is a most awesome phoenix.”

Looking back two years later, Gorky observed, “Sometimes it is very good to have everything cleaned out like that, and be forced to begin again.” With a sense of release and energized by the tragedy, Gorky went to work as if his life depended on it. He was driven also by the fact that he needed to produce paintings for an upcoming exhibition. “It’s amazing how he feels like working,” Mougouch wrote. “I don’t believe I have ever seen him so free about his work it’s just the right time that[’s] all & nothing can stop him—& when it’s not just the right time nothing on earth can help him.” That freedom and urgency can be felt in Charred Beloved I.

In the weeks that followed the fire, in a borrowed studio, Gorky painted all three versions of Charred Beloved, plus two other canvases, Nude and Delicate Game (P308). To fill out his April 9 exhibition, he added several paintings from 1945, paintings that, like the 1946 canvases, continued the separation of line and color first seen in late 1944 works like They Will Take My Island. In that earlier painting, black lines of various widths careen around bursts of color. In the 1945 and 1946 paintings, taut, wire-thin black lines, now all of the same width, are more ruminative. To create this delicate tracery, Gorky must have pulled some of the hairs out of the sign painter’s brush that Willem de Kooning had encouraged him to use in 1944. Black lines that move over the surface with the precision and equipoise of a figure skater look continuous, as if the tip of the sign painter’s brush had never left the canvas. Closer inspection reveals that when his brush went dry, Gorky dipped it again in black paint.

73

“Gorky is a most awesome phoenix.”

AGNES “MOUGOUCH” GORKY

As lines search through space, they both define and circumvent shapes and spots of color. They also link all the shapes together, creating a gentle upward drift of forms starting with Gorky’s familiar boot motif in the canvas’ lower third and circling upward to a kite-like shape in the upper right corner. Shapes attached to thin black lines gently jostle back and forth bringing to mind the mobiles of Gorky’s friend and neighbor Alexander Calder. (Both artists were inspired by Joan Miró’s paintings of the 1920s.) Compared to the voluptuous lushness of the paintings Gorky did in the spring and summer of 1944—works such as The Liver Is the Cock’s Comb (P281) and Water of the Flowery Mill (P292) the 1945 paintings are spare. The paintings from 1946 are sparer still. Some observers thought of them as tinted drawings. Charred Beloved I, with its layered and loosely brushed ground, does retain some of the sensuousness of Gorky’s work from early 1944, but that sensuousness is no longer wild and exuberant. Gorky has moved toward simplicity, a filtering of feeling. He wanted something stripped down, vitality within calm.

Although the metamorphic shapes in the Charred Beloved paintings allude to the studio fire, their meaning remains elusive. In Charred Beloved I, the embers are still hot. The fire has mostly died out in the two versions that followed. Touches of color bring life to the smoke-filled space, reminding us of what is lost. Darkness lurks behind light. Still, the kite shape in the upper right corner flies high. There is always the possibility of transcendence, it seems to say. In the end, tempting though it is to put faces on Gorky’s images, the colors and shapes in the Charred Beloveds are the colors and shapes of reverie. We can enter that reverie, but we cannot pinpoint what is going on inside the artist’s mind.

Two and a half months after the studio fire, Gorky underwent a colostomy for rectal cancer. Once again, his spirit rose from the ashes. That summer he sat on a stool in a Virginia field and drew what weeds and grasses triggered in his imagination. Gorky was, Mougouch said, “working like a mad man—a happy one.” He was convinced that his best work was in front of him. In November, just before leaving Virginia, he wrote to his younger sister: “this summer I finished a lot of drawings… 292 of them. Never have I been able to do so much work, and they are good, too.”

74 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

75

Arshile Gorky, The Liver is the Cock’s Comb (P281), 1944. Buffalo AKG Art Museum. © 2023 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Photo: Buffalo AKG Art Museum / Art Resource, NY.

78 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

CHARRED BELOVED I

MAX CARTER

In The Shock of the New (1980), Robert Hughes suggested that Arshile Gorky’s life “as a mature artist formed a kind of Bridge of Sighs between Surrealism and America; he was the last major painter whom Breton claimed for Surrealism and the first of the Abstract Expressionists as well.” Hughes’s analogy is not, of course, particularly sound. Surrealism led to Abstract Expressionism; whatever one thinks of post-war art, the Bridge of Sighs carried Venetians from the Doge’s Palace to prison. But insofar as Gorky was the period’s singular hinge figure, and the view from the bridge was beautiful in itself and in its sublime possibility, there are affinities with his maturity and with Charred Beloved I and its three related works.

Gorky was born Vostanik Manug Adoian in ca. 1904 in Khorkom, on the shore of Lake Van in Ottoman Turkey. Stuart Davis would question the posthumous caricature of Gorky as “handmaiden of Misery” in the late fifties: “He had many unique qualities, but poverty was not one of them.” Gorky’s past, however, was distinct from his peers. Davis’s father was an editor of The Philadelphia Press; Gorky’s father left his family for America when his son was four. Davis’s mother sculpted; Gorky’s maternal grandfather was killed in one of the Hammidian massacres of the 1890s—Gorky would say that he had been crucified on the door of his own church—and his mother Shushan’s first husband was executed for revolutionary activity. Shushan was forced to abandon her daughter, Sima, on the occasion of her arranged, and unhappy, second marriage (Sima died in an orphanage shortly after); she fled with her remaining children on foot for eight days from the subsequent genocide; she died after being refused entry to the hospital on the outskirts of the city of Van; and she was buried in an unmarked communal grave. As Gorky’s younger sister, Vartoosh recalled, the hospital’s rejection was vicious. Gorky, who tried to have her admitted, was thrown down the stairs.

79

He emigrated to Watertown, Massachusetts with Vartoosh—and limited English—in 1920. How an artist resolves to become an artist is very rarely clear, and Gorky is no exception. He was soon to be found drawing on the black tarpaper tiles on the roof of Hood Rubber, where he and his sisters worked in the early twenties. Gorky was fired within several months and thereafter enrolled at Providence’s Technical High School.

Contemporary photographs show Gorky channeling his inner Whistler—sitting outside before an easel, wearing jacket and tie, or striking his most studiously romantic pose, devil-may-care chain draped pointlessly around his neck. On seeing “Gorky walking down the street clad in a long, flapping cloak,” his cousin Lucia “laughed and laughed, and thereafter whenever she saw him again, she laughed,” Matthew Spender recounted in his biography of the painter. “‘Well,’ she said, as if it explained everything, ‘he looked like Jesus Christ.’” As part of his self-fashioning he adopted the name Arshile (“Arshel”, at first) Gorky. He was possibly unaware that Maxim Gorky, who some took to be his uncle, was born Alexei Peshkov.

By the time he moved to New York in 1924, Gorky was already an accomplished draftsman—he claimed to have studied in Paris—and an eloquent, often contrarian exponent of the techniques of the past. His admiration for William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s “licked” paint surface was likely as unpopular in the halls of the Art Students League as it would have been among the Impressionists.

It was in these years that the myth of what might be styled “method painting” attached itself to Gorky. “[John] Graham told a friend that Gorky even emulated the lives, as well as the styles, of his heroes. He’d even had a Modigliani moment, complete with Modiglianiesque girlfriend and Modiglianiesque beard,” wrote Spender. “Once, Gorky sat down in front of Graham in a café and drew a Picasso, complete with signature, without a moment’s hesitation. Graham told the story with awe in his voice. Graham saw that for someone like Gorky, coming from so far away, the need to acquire the culture of the West was much stronger than for those who were born there. It was more than a question of ‘influences.’”

80 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

81

Arshile Gorky, The Artist’s Mother (D0663), 1926 or 1936. Art Institute of Chicago. © 2023 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Photo: The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY.

82 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

Arshile Gorky, Water of the Flowery Mill (P292), 1944. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. © 2023 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY.

Spender revisited this theme in his introduction to Gorky’s letters: “He never felt the urge to push towards ‘originality’. He never wanted, to put it in Freudian terms, to ‘kill the father’ in order to break free from some imponderable weight. When Levy accused him of being too much under the influence of Cezanne and Picasso, he replied: ‘I was “with” Cezanne for a long time. And then naturally I was “with” Picasso.’ It is an excellent choice of words, but it is much more in keeping with the early twenty-first century than with the language of postwar New York.” One need only look at or juxtapose what Pollock or Rothko was up to in the mid-forties to take the measure of Gorky’s originality—which John Elderfield explores memorably through the prism of hybridity and metamorphosis—but it was not its own end. This “rejection of originality as a goal,” Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan noted in their biography of de Kooning, “deeply affected de Kooning. ‘Aha, so you have ideas of your own,’ Gorky told de Kooning when he first looked at his work. ‘Somehow,’ said de Kooning, ‘that didn’t seem so good.’”

Whatever Gorky’s conception of originality, his genius flowered in roughly the last five years of his life, with the nurturing of Agnes Magruder (“Mougouch”, to Gorky), whom he married in 1941, and the instrumental financial and emotional support of Jeanne Reynal. A trip to San Francisco with Noguchi at Reynal’s instigation enabled him to move beyond his prior, pathologically thick application of paint. (“At this period,” Gorky remarked, “I measured by weight.”) And he exulted in the landscape of Lincoln, Virginia, where he stayed on the Magruder family farm. In September 1945, the Gorkys relocated to the house of Jean and Henry Hebbeln in Sherman, Connecticut. The following January, while Mougouch and their daughters were away, Gorky’s studio in the Hebbelns’ barn was consumed by fire. He lost some twenty paintings, along with his drawings and books. For an artist with fewer than 400 recorded oils and meticulous habits, the experience could have been debilitating—or worse.

83

“One need only look at or juxtapose what Pollock or Rothko was up to in the mid-forties to take the measure of Gorky’s originality…”

More than three decades earlier, in 1913, Alfred Stieglitz received an alarming call in the middle of the night. A fire had broken out in the apartment below his gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue. He assumed that nothing inside would survive and therefore saw no point in rushing to the scene. An account of his agony was featured in The New York Globe: “He knew that the loss of [the work of his artists] would to them mean tragedy and might change the course of their lives. That these tangible manifestations of his own idealistic spirit and of that of the artists should be destroyed meant that for several hours Alfred Stieglitz went through perhaps the most intense experience of his life. When he went to the gallery and found that nothing had been touched he had no feeling of relief or pleasure. His capacity for emotion had been exhausted… [But] he said… if those pictures, plates, photographs, and drawings had been destroyed, he would have gone to some pseudo art collection, to some gallery of respectable paintings, to some museum in which academical compromise in the way of art was stored, and would have burnt it up.” Stieglitz’s tragedy was imagined. Gorky’s was not. But instead of visiting the torch on others, he began again.

Of the four 40 paintings Gorky completed in the ballroom he borrowed in the wake of the fire on the 17th floor of 1200 Fifth Avenue, three were Charred Beloveds: I and Nos. 1 and 2. Although the sizes and formats are uniform, their tonality is not: Nos. 1 and 2 are sooty, grisaille. (Nude, which is the fourth canvas, is nearer in palette to I.) A rigidly literal interpretation would place I in the midst of the blaze, and the further pair in its dimming embers. The numbering, in any event, does not correspond to an established chronology. No. 1 is so called because that is how it appeared in the checklist for the first and only time it was shown during Gorky’s lifetime in 1946. The irresolvable question of Gorky’s order becomes rhythmical. Did he proceed from light to dark? Dark to light? Light to dark to light? Dark to light to dark?

84 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

“A rigidly literal interpretation would place [Charred Beloved I] in the midst of the blaze, and the further pair in its dimming embers.”

85

Arshile Gorky in the “Glass House,” Sherman, Connecticut, January 1948.

Photo: Ben Schnall. Courtesy of the Arshile Gorky Foundation.

86 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

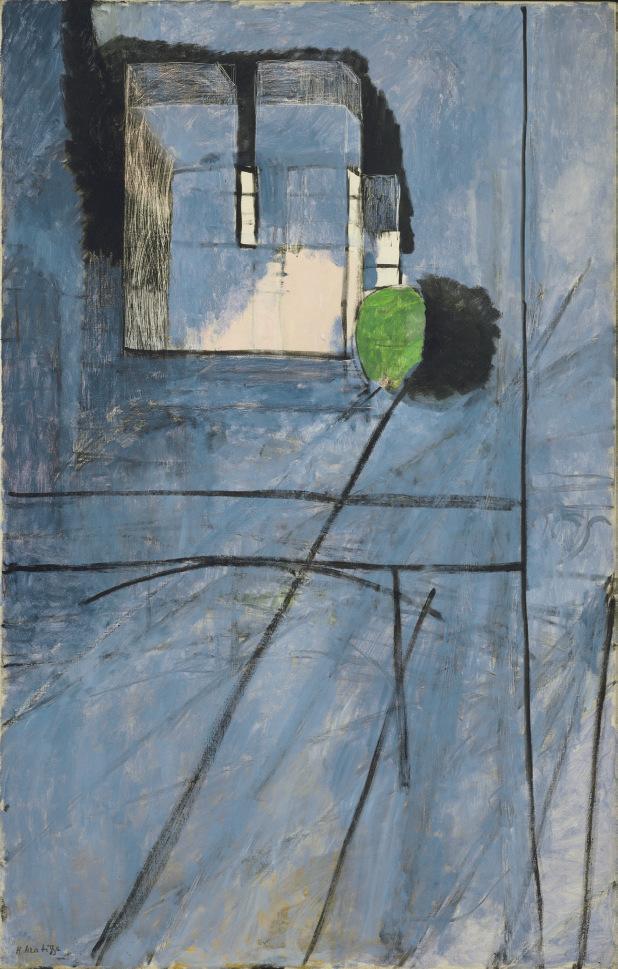

Arshile Gorky, Nighttime, Enigma and Nostalgia (P120), circa 1933-1934. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. © 2023 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston / Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund / Bridgeman Images.

From this devastating episode unfurled the nightmarish series of events that preceded his death in 1948: his operation for rectal cancer (at Mount Sinai, three blocks south from his ballroom perch at 1200 Fifth Avenue); the storm-induced car accident with his dealer, Julien Levy, in which he broke his neck and briefly lost the use of his painting arm (“You want me to be brave,” he told the attending nurses, “but I am like an onion which has been peeled of its skin and of its layers, until I feel everything. I feel even the trembling of a leaf”); and his strange, poignant confrontation with Matta in Central Park over the latter’s weekend dalliance with Mougouch. (Gorky’s studio in Lincoln was, in his absence, also struck down by fire.) In the burst in which he painted the four great Ballroom canvases, Gorky was suspended 17 floors in the air, between the vestiges of his past and an uncertain but still hopeful future.

If, as has been said, Gorky was not good at small talk, then neither are his paintings. There is no throat clearing, trivia, or form or flourish to no purpose. Jed Perl cites Gorky’s distinction between “sun” and “moon” painters with reference to Charred Beloved I. The painting evokes, too, his onetime friend John Graham’s feelings of “enigma” (in Spender’s words, “meaning the quality of emotion which a work of art could carry—the far side of its physical appearance, as it were”) and “nostalgia” (“in the sense of endowing a work with the accumulated weight of the past, not necessarily in its figurative references but in its mood”). Charred Beloved I is, in Graham’s terms, deeply enigmatic and nostalgic. (These were not alien notions to Gorky: see his more than 100 versions of Nighttime, Enigma and Nostalgia.)

87

The particulars and aftermath of the Sherman studio fire are addressed far more authoritatively in the preceding essays than they might be here. But it is worth considering what Spender calls “a moral problem”41 as the guest of the Hebbelns: “If he saved his works while the barn burned, wouldn’t that make the situation even worse? He allowed a certain number of paintings to be destroyed so that his loss and the owner’s would somehow be equalized.” There is an element of selfless concern—and another of propitiation.

For the turn-of-the-century Adoians, fire represented more than simply another calamity. “In the Zoroastrian religion,” Spender related, “which underlies the faith of so many Armenians of Van, fire is not a symbol for God, but God itself, and to extinguish fire without permitting it to run its course is a form of sacrilege.” Gorky never left his native identity behind. He corresponded in his local Armenian dialect throughout his life and his bank book in America was under Manug Adoian.

88 ARSHILE GORKY CHARRED BELOVED I

“In the Zoroastrian religion, which underlies the faith of so many Armenians of Van, fire is not a symbol for God, but God itself, and to extinguish fire without permitting it to run its course is a form of sacrilege.”

MATTHEW SPENDER

89

Lake Van, Akhmatar Island. Photo: John Donat / RIBA Collections.

Elderfield refers to Gorky’s “atavistic anxiety”. Hayden Herrera observes his identification as “a man of fate”, and the leitmotif of fire. His grandmother burned down the village church, and he was himself to know fire’s inextricable powers of creation and destruction. Graham likened the artist’s struggle to the primitive man attempting to make fire, rubbing two sticks together over and over again before giving up in despair: “Perhaps if you had kept on trying only one minute and a half more a blue flame would have risen up!” A fire destroyed the dozen or so paintings he had given his half-sister, Akabi. Upset—was it carelessness?—he denied her more. “And the world is ruthless, ruthless, has always / consumed [everything] with fire and sword,” Gorky lamented in an undated poem of the thirties, “[inflicted] such pain before this understanding. / And the melancholy fire came under cover / of darkness.”

One can easily imagine the studio of Pollock or, later, de Kooning engulfed in flames after an all-night binge. Yet it was Gorky’s lot. He whose habit of polishing his floor at home until it shone impressed Noguchi; who, according to Spender, “worked as methodically as an artist of the Quattrocento”; who had Rothko, one of his first students at the New School of Design, carry out the trash; who always took care. “Do you seek fire?” asks an ancient verse. “Here is a man of fire.”

91

ENDNOTES

1 “Past Perfect: A young New York couple build their daughters a playground in the sky,” House & Garden, April 1931.

2 Anges Mgruder Gorky, letter to Jeanne Reynal, November, 1944, in Arshile Gorky: The Plow and the Song: A Life in Letters and Documents, ed. Matthew Spender, Hauser & Wirth Publishers, 2018.

3 Arshile Gorky, “My Murals for the Newark Airport: An Interpretation, in Arshile Gorky: The Plow and the Song,” op. cit.

4 “Concerning the Beginnings of the New York School: 1939-43” Sidney Simon interview with Peter Busa and Roberto Matta Echaurren, December, 1966, in Art International, Summer 1967.

5 Robert Storr, “The Painter’s Painter,” in Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective, ed. Michael Taylor, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2009.

6 Interview with K. Mooradian, 29 April, 1967, in The Many Worlds of Arshile Gorky, Karlen Mooradian, Gilgamesh Press, 1980.

7 AAA Smithsonian, Rothko project. Interview with Elaine de Kooning, by Phyllis Tuchman, August 27, 1981.

8 The Artist’s Reality, Yale, 2004, pp. 93-104. Christopher Rothko, in his introduction, dates this book to 1940-41.

9 Matta to Maro Gorky, Thursday, May 29, 1997, in Arshile Gorky: The Plow and the Song, op. cit.