Title: The Absence of Presence in Performance Art Documentation

Author: Lewis Cavinue

Publication Year/Date: May 2024

Document Version: Fine Art Hons dissertation

License: CC-BY-NC-ND

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20933/100001303

Take down policy: If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim.

TheAbsenceofPresenceinPerformanceArtDocumentation

DuncanofJordanstone University of Dundee

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Bachelor of Arts (Hons) degree in Fine Art

DJ40002

FineArt - Exhibition Project

Word Count: 7,499

2024

Lewis Cavinue

Contents Acknowledgements 3 Personal Statement 4 List of Figures 5 Abstract 6 Introduction 7 ChapterOne:CuratorialThesis 9 Performance art beyond the White Cube 9 Capturing the Essence 12 ChapterTwo:Curatorialchoices 14 Artists and their Artworks 14 ChapterThree:CuratorialAimsandInfluences 25 Unconventional Exhibition Spaces 25 Intended Audience 26 Encounter becomes Audience, becomes Participant 27 ChapterFour:OtherCuratorialInfluences 29 Forging Connections 29 Hans Ulrich Obrist 30 Marina Abramović 30 Conclusion 32 References 33 Appendices 37

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to my tutor, Hellen Gorrill, for her priceless advice and guidance, all her help inspiring and building my confidence to believe in the things I am writing.

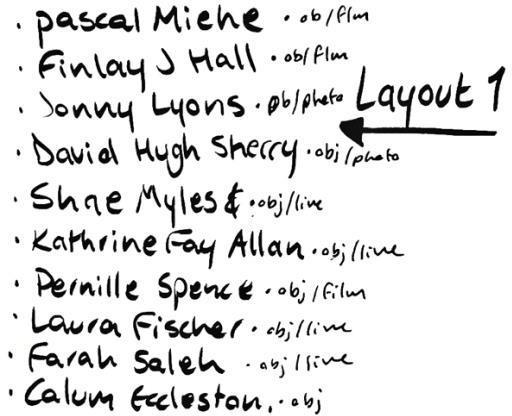

The biggest thanks of all extends to everyone who participated in conversation with me during this project, especially those who I communicated with directly; Callum Eccleston, Pascal Miehe, Pernille Spence, Finlay J Hall, Farah Saleh, David Sherry.

I would like to thank my friends and family, for offering their support and encouragement throughout the full project, be it helping me edit my work or just listening to me rambling on about art for hours.

And finally, to Kathryn Rattray, for fostering a space like The Keiller Centre where people feel welcome and included, generating community, care, and culture within the city. Thank you for your continuous support of me and my work.

3

PersonalStatement

I am a Dundee-based artist originally from Motherwell, Scotland.

4

ListofFigures

Figure 1 Miehe, P. (2023) ARENA. Available at: https://www.pascalmiehe.com/arena-1 Documented by Pascal Miehe. Images courtesy of artist

Figure 2 Sherry, D. (2010) Living the Dream After Death. Available at: http://www.dave-sherry.com/Performance-Dave-Sherry-27-Living-the-dreamafter-death.html Documented by David Sherry. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 3 Myles, S. (2023) Hush Lil Baby. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/C0E62Leonw3/?img_index=1 Documented by Bart Urbanski. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 4 Hall, F.J. (2023) Party Machine. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FziCeTpycNY Documented by Finlay J Hall. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 5 Allan, K.F. (2019) The Rest of Us… We Just Go Gardening. Available at: https://www.katherinefayallan.com/therestofuswejustgogardening Documented by Kathrine Fay Allan. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 6 Spence, P. (1995) NaCl. Available at: https://www.pernille-spence.co.uk/nacl Documented by Gregg Allen, Stewart Petri & Anna McLauchlan. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 7 Lyons, J. (2014) The Sheltering Sky. Available at: https://www.inglebygallery.com/artists/47-jonny-lyons/works/54394-jonnylyons-the-sheltering-sky-2014/ Documented by Jonny Lyons. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 8 Fischer, L. (2023) FORGED (in the tender heat of your embrace). Available at: https://www.laurafisherperformance.com/forged-unlimited-commission Photography by Emily Nicholl. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 9 Saleh, F. (2022) What Does the Space Know. Available at: https://www.farahsaleh.com/what-does-the-space-know Documentedby Lucas Chih-Peng Kao and Meray Diner. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 10 Eccleston, C. (2023) Take Leave. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CoAdGKOjXm0/ Video document by Sarah Smart, photographic document by Judit Bodor. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 11 Exhibition Layout. Floorplan courtesy of The Keiller Centre Available at: https://www.thekeillercentre.com/centre-map

5

Abstract

By abandoning the conformity of the White Cube gallery, this exhibition proposal replaces neutrality with an experience embracing unconventionality and participation. Integrating a programme of live and documented presentations, the audience are invited to encounter the works as they navigate the occupied units of The Keiller Centre, a seventies shopping centre. Each artwork proposes a different interpretation of how to document performance art, and so too how it can be re-exhibited after the act. United through an overall absenceof theperformer, the artworks prompt the audience to participate in activating the space, pondering where the performance lies through a recalled experience of the document. This is supported by a critical exploration into the pillars of performance art, dematerialisation, and the activation of unconventional creative spaces to promote a wider appreciation for contemporary art.

6

Introduction

The following proposal is a critical analysis of performance art, accomplished through curating an exhibition that engages with the pillars of documenting and re-exhibiting works of performance. In utilising the units of The Keiller Centre, an environment of curiosity invites the audience to encounter each artist’s work through a nuanced exhibition experience.

The dynamic and transformative nature of performance art challenges the established norms of art presentation within the traditional White Cube gallery space. Since its emergence in the 1960s and 1970s, performance art has shifted the focus from object-based artworks to the visceral and personal presentation oftheartist's body.Its departure from object-basedtraditions revolted against this standardisation of space and etiquette. This departure, as explored by Lucy Lippard (1997), marked a significant dematerialisation of art, emphasising the importance of conceptual ideas over material objects.

It’s not about the object, and it’s not about the image; it’s about the viewer. That’s where the art happens (Koons, 2009).

Captured in the fleeting interaction between performer and audience, performance is pronounced to us through terms of ephemerality and irreproducibility (Phelan, 1993). The concurrent acceptance of an encounter as both a meeting and a conflict is not just feasible but valuable within the realm of public performance art. This dual perspective is achievable because of the inherent social and political nature of performance, enabling the coexistence of conflicting forces. Navigating this tension within the art world introduces unpredictability, which, from an institutional standpoint, brings forth both challenges and possibilities.

The capacity of performance art to transcend its live occurrence elevates the importance of documentating within the broader context of contemporary art discourse. In our progressively technological and media-driven society, it is unsurprising that the ephemeral nature of performance art would yield to the practice of media documentation. With a growing emphasis on the capability of documentation to capture the subtleties and complexities of live performances, fresh opportunities emerge for individuals to engage with performance art in different ways. The concept of remediation produces insight toward the system of historical inscription that the document holds in relation to its live performance.

7

A new medium is never an addition to an old one, nor does it leave the old one in peace. It never ceases to oppress the older media until it finds new shapes and positions for them (McLuhan, 1964)

It is in these new shapes that the document offers a capacity to engage with different information and ideas within our prominent technological landscape. Specifically for performance art, this presents a chance to explore and expand innovative approaches to engagement and curation, methods that might not be widely known or recognised. With this I intend to explore how the audience will encounter the work in this unconventional space.

Encountering piques interest, and with intrigue comes participation. Participatory art, alike performance art, defies traditional limitations. Through the unconventional space of the centre, I plan to openly encourage a dialogue that broadens the audience's understanding of performance art through the importance of its document. Fostering active participation in this exhibition will enrich the experience of theaudience, subsequently creating a space of constant performance, with the audience at the helm.

Audiences will participate in the art, even if they break the strictures of etiquette, and so the art should be curated and exhibited in a way that encourages it to talk to the observers (Kessels, 2020).

I intend to extend this idea of co-creating into my philosophy around the role of the curator. This exhibition hosts an expansive range of performance work, transcending any one theme or message. Through examining the role of the curator in the contemporary art world and fixing it in relation to how we experience performance art, my explorations aim to build greater connections to the artists who have created the work. Conversing with them directly will help meexplorehowdocumentsofperformancecanexistinanewcontext,whilstremainingfaithful to the artist’s initial concept. In doing so I hope to expand not only my own understanding of this, but also build a collaborative basis of questioning around the ephemeral nature of performance and its document.

8

Chapter One: Curatorial Thesis

PerformanceartbeyondtheWhiteCube

Since its inception in the early 20th century, the White Cube gallery space has been the idealist model for presenting art, particularly suited to the simplicity and modernity of abstract works (Tate, 2017). Brian O'Doherty's seminal work, Inside the White Cube, offers profound insights into the institutionalisation of art within these sterile confines (O’Doherty, 1999). O'Doherty contends that the modernist conception of the gallery as a neutral, detached space, with its ubiquitous white walls and prescribed behaviours, carelessly imposes a specifically prescribed context on the exhibited works.

The White Cube, once considered a sanctuary for art appreciation, has become a symbol of objectivity, isolating art from the external world, and divorcing it from the everyday functions oflife. The controlled and hushed atmosphereexpectedfrom gallery visitors adds another layer of limitation, dictating how one should engage with the art. But if the artwork itself is disconnected from any external contexts, then so too is the audience. The body of the observer is denied within the detached vessel of the gallery.

The space offers the thought that while eyes and minds are welcome, space-occupying bodies are not – or are tolerated only as kinesthetic mannequins for further study (O’Doherty, 1999, p. 15).

This prescribed etiquette continues to reinforce the notion that art should be experienced in a certain way,within the confines ofapredetermined spaceandcontext. Consequently, theWhite Cube's aesthetic and behavioural restrictions have a profound impact on how we perceive and interpret art, shaping our understanding within the framework imposed by the gallery itself. In questioning the neutrality of the White Cube, O'Doherty (1999) prompts us to reconsider the existing dynamics between art, the audience, and external contexts, encouraging a more critical and nuanced approach to the gallery experience.

Performance art, unlike traditional mediums, is intrinsically contextualised by its surrounding world. The art form as we know it today, emerging from the 1960s and 1970s, marked a departure from the object-based focus of traditional art forms. O’Doherty delves into the audience's interaction with paintings and objects in the gallery. However, to understand the role of performance art within the gallery, it is essential to examine the practice of kinetic artistic forms. Performance artists began to transcend ideas of the material medium. Lucy

9

Lippard delves into the concept of dematerialising art, advocating for a shift away from the prevailing focus onconventional objects, ultimately underscoringthe importanceofconceptual ideas.

Idea as idea, idea as action, idea as performance (Lippard, 1997)

For Performance, dematerialisation came through the form of the body, serving as a conduit for emotional and intellectual expression. By incorporating the artist's body into the work, performances became visceral and personal, challenging conventional notions of artistic creation. Human presence became the relative object within the prescribed space of the gallery (Warr and Jones, 2000). The body became a medium and the site became a canvas. Artists began to use their own bodies as tools to convey complex narratives, emotions, and ideas, moving beyond the necessity for audiences to anthropomorphise static works in hopes of comprehending them. This embodied experience disrupts the traditional passive role of the audience, encouraging active participation and emotional engagement with a work. As performance art continued to embrace the immediacy of the present moment, it allowed for a more direct and intimate connection between the artist and the audience. No longer exiled or confined to observing from a dictated distance by the gallery, the audience are invited into the present moment, sharing a collective experience that transcends the boundaries of traditional art spaces.

Artistssoughttodirectly address andprompttheaudience,beitphysically ormentally,blurring the existing boundaries between art and life. This shift, that coincided and links back to their need to dematerialise, was driven by a desire to break down the elitism and rampant commercialisation associated with art at this time, aiming to make it accessible to a broader audience. Adrian Heathfield suggests that the future of art lies not in the object itself but in its connection with the public sphere. He concludes, particularly in the realm of performance, that there is a shift towards replacing or supplementing material objects with temporal acts (Glendinning and Heathfield, 2004). Therefore, performance holds within it an entity of comprehension for the meaning it presents, a container of shared memory and an intention for understanding that contextualises it.

The communication between artist and audience shows the significance of space and time within this artistic expression. The ephemeral nature of performances mean that they are

10

inherently site-specific, rejecting the notion of art as a static object confined within the walls of a gallery. Nick Kaye's Site-specific art: Performance, Place, and Documentation explores this relationship between performance and its environment, emphasising theimportance placed upon context in shaping the meaning of the work for the audience (Kaye, 2000). When space itself becomes the canvas a dynamic interaction with the artist's movements, gestures, and expressions arises. This challenges the traditional gallery setting where artworks are typically framed and isolated. Instead, performance art engages with the surrounding environment, architecture, and atmosphere, between the notion of the staged and the everyday. Considering this, it is important to discuss how work of performanceartreaches the audienceon a curatorial level.

Curating performance art poses unique challenges compared to traditional artforms. Jen Ortiz's article in Hyperallergic online magazine, titled ‘How to curate performance art and other problems’, addresses the complexities of beginning to think about curating temporal and experiential artworks (Ortiz, 2012). Ortiz emphasises the importance of considering the context, duration, and purpose of making performance in engaging with how it is curated. Conversations between Ryan Hawk andOrtizexplored Hawk’sstatement that, thefundamental nature of performance art is in it is rejection of the mainstream, and subsequently commodification.

An example highlighting the intersection of curation and performance, in developing a strategy for multidisciplinary works, is evident through the idea of Live Art. Lois Keiden, who was the director of Live Arts at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London from 1992 to 1997 (Gitonga, 2023), coined this term and laid the foundation for a dynamic approach to curating. In 1999, Keiden, along with others, established the Live Art Development Agency, a curatorial platform crafted specifically for artists engaged in practices that challenged the conventional categorisation within prevailing structures of the time (Ferdman, 2014, p. 9). This endeavour meaningfully contributed to promoting a variety of performance engagement approaches within gallery institutions. Focus thus began shifting towards unconventional creative spaces.

Unlike static artworks, performance requires careful consideration of temporal and spatial aspects in its presentation. Given that curators must navigate issues of documentation, it is important to acknowledge that the essence of performance lies in the live experience. The

11

challenge is to strike a balance between preserving the integrity of the work and making it accessible to a wider audience through later exhibition.

CapturingtheEssence

In this medium, or rather non-medium, renowned for its ephemerality, the act of documenting holds profound significance. This practice not only aims to preserve the essence of a moment but also allows the art form to transcend its live occurrence, reaching a wider audience and contributing to the broader discourse on contemporary art. The mediums employed in this documentation process photography, video, writing, and object remanence each play a distinctive role in capturing the intricacies and nuances of a live performance, albeit with their own challenges and implications.

Photography, as a prominent medium for documenting performance art, operates by freezing a specific moment in time, aiming to condense animageto depict the heart of thelive experience (MacLennan, 2020). The careful selection of framing and timing becomes a delicate dance for the role of the documenter, attempting to distil the essence of a performance into a single, evocative visual representation. However, the tension arises when the static nature of the photographconflicts with thedynamicandever-evolving natureofthe liveperformance. Peggy Phelan, a notable figure in performance art discourse, vehemently rejects the notion of documenting performance, asserting that its true essence can only exist in the alive moment (Phelan, 1993). Despite these reservations, photography stands as a powerful tool, offering a tangible glimpse into the visual impact and aesthetic elements of a performance, acting as a portal to the past for future audiences. In Kathy O’Dell’s research around the photographic document, she argues for this tangibility proclaiming:

The reception of performance art – which is to say, the reception of the photographic documents from which performance art is inseparable- is not exclusively dependant on the visual experience, but relies heavily on the experience of touch (O’Dell, 1997)

Video, in contrast, provides a more dynamic and immersive medium for documenting performance art. Johannes Birringer, in his thought-provoking article 'Video art/ performance: A border theory,' delves into this intersection of video and performance, emphasising the uniquecapacity video has inconveying the emotional andvisceral aspects ofliveperformances (Birringer, 1991). Unlike static photographs, video captures a fluidity of movement, the resonance of sound, and subtle nuances indicative of a live performance. It becomes a vessel

12

through which audiences can immerse themselves in the feelings, emotions, and connections obtained during the original event.

Objects, as artifacts of the performance, introduce a tangible and physical dimension to the documentation process. These objects, whether intentionally incorporated into the live event or remnants left behind, become relics that bear witness to the ephemeral act. In the book Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object, the discourse revolves around whether these objects, as documentation, re-perform the live work or exist as entities with their own distinct significance (Schimmel, 1998). The physicality of the object adds layers of materiality to the documentation, contributing to the ongoing dialogue between the ephemeral and the tangible. However, the challenge lies in striking a balance between the absence and presence of the performer in the documented piece, whilst maintaining an authenticity to the live experience, leveraging the advantages of the documented medium.

Exploring whether the performer is present or absent in documentation is as complex as the method of documentation itself. Phelan's insistence on the unrepeatable nature of live performance challenges the idea of documentation as a faithful representation. However, Philip Auslander, a scholar in the field, counters this perspective in his works The Performativity of Performance Documentation' and 'Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture (Auslander, 2008). Auslander argues for the intrinsic value of documentation in extending the life of a performance, suggesting that it becomes a separate performative act in itself (Auslander, 2006). This dichotomy raises fundamental questions about the nature of authenticity and the role of documentation in preserving the heart of performance art.

The notion of documentation as relics or reflections from live performances invites contemplation regarding their true nature and function. Can these documents authentically capture the essence of a live performance, or do they exist as separate entities with their own intrinsic significance? The publication ‘Performing the Exhibition’ from oncurating.org explores the intersection of performance art and installation art, emphasising the role of documentation in extending the life of the performance beyond its temporal boundaries (Omlin, 2011). The re-exhibiting of these documents allows for a revisiting of the initial experience, inviting new audiences to engage with the work in novel ways.

13

ChapterTwo:Curatorialchoices

ArtistsandtheirArtworks

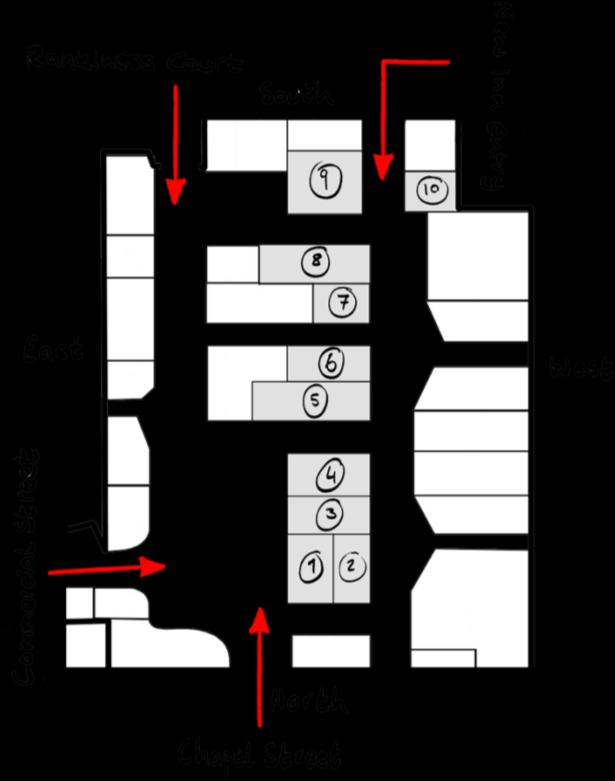

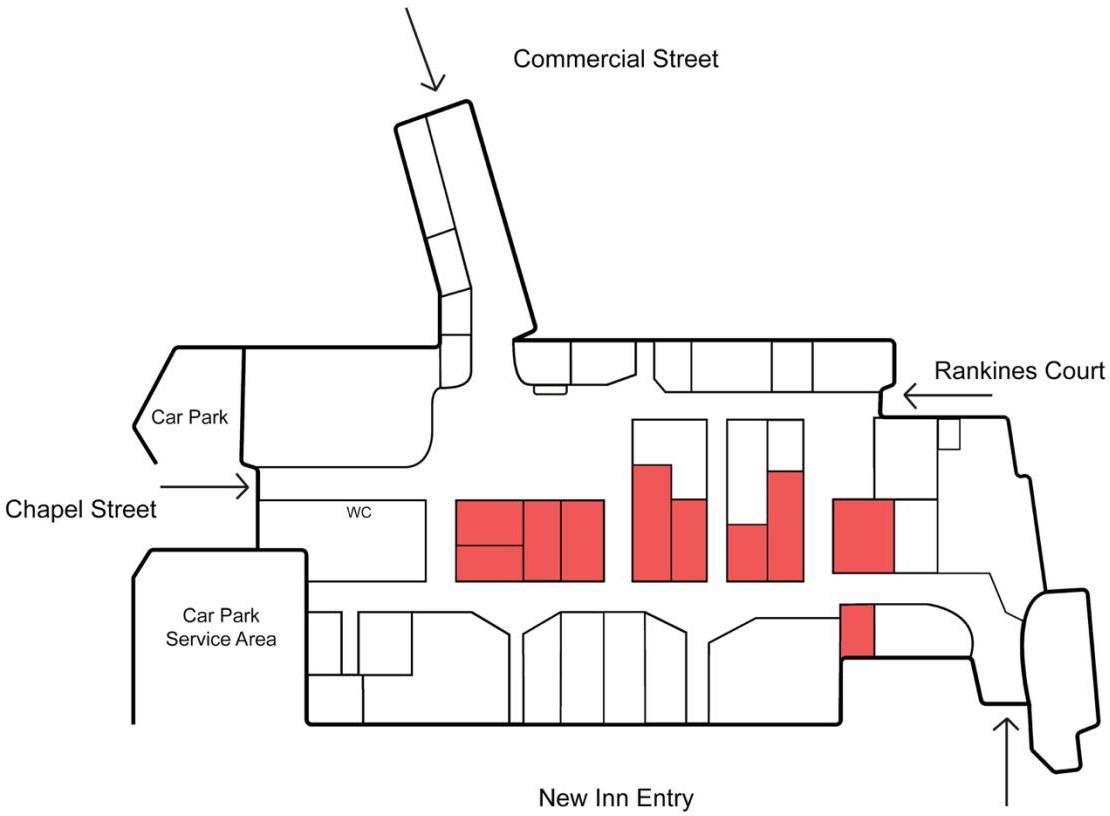

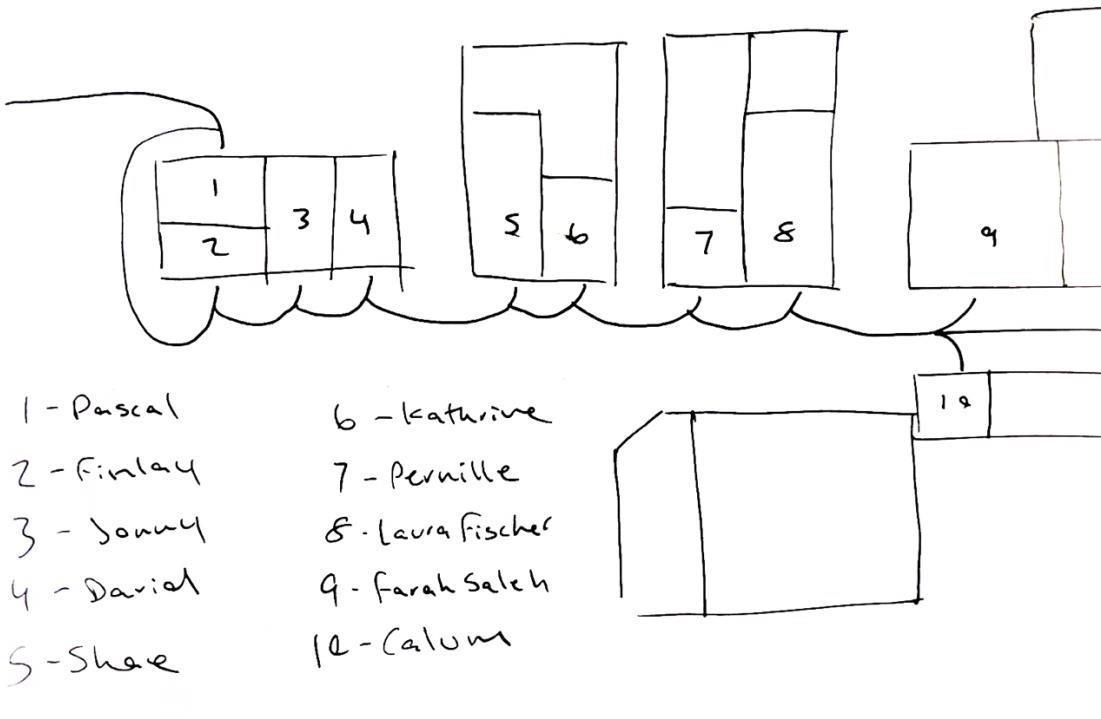

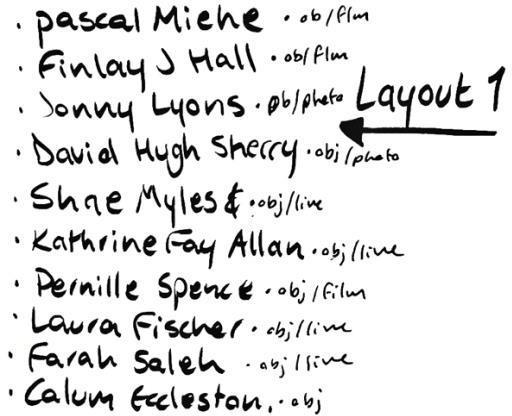

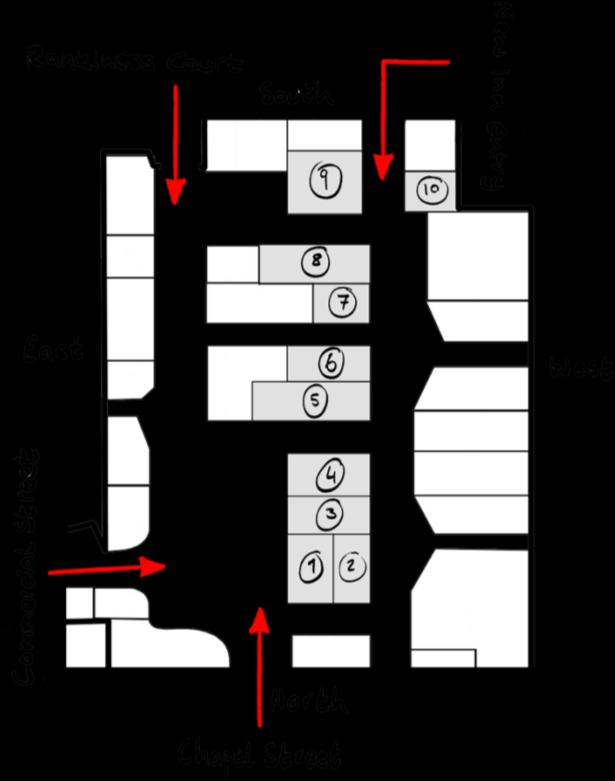

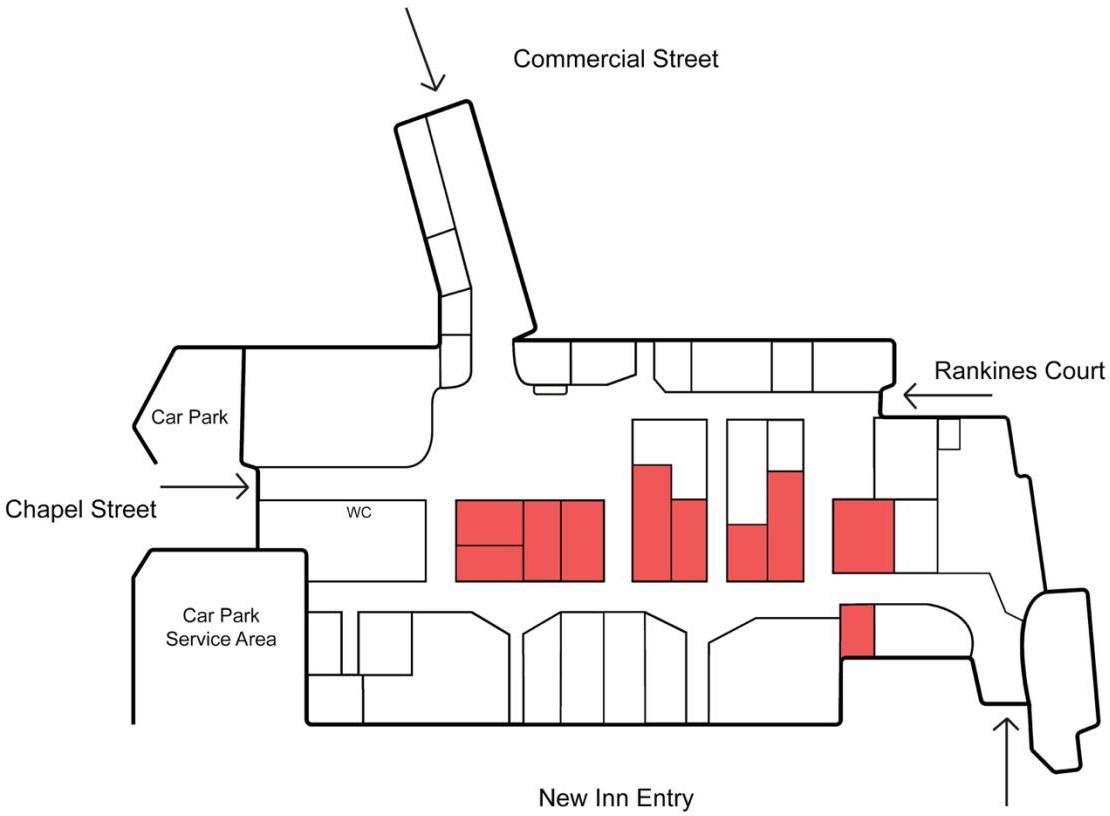

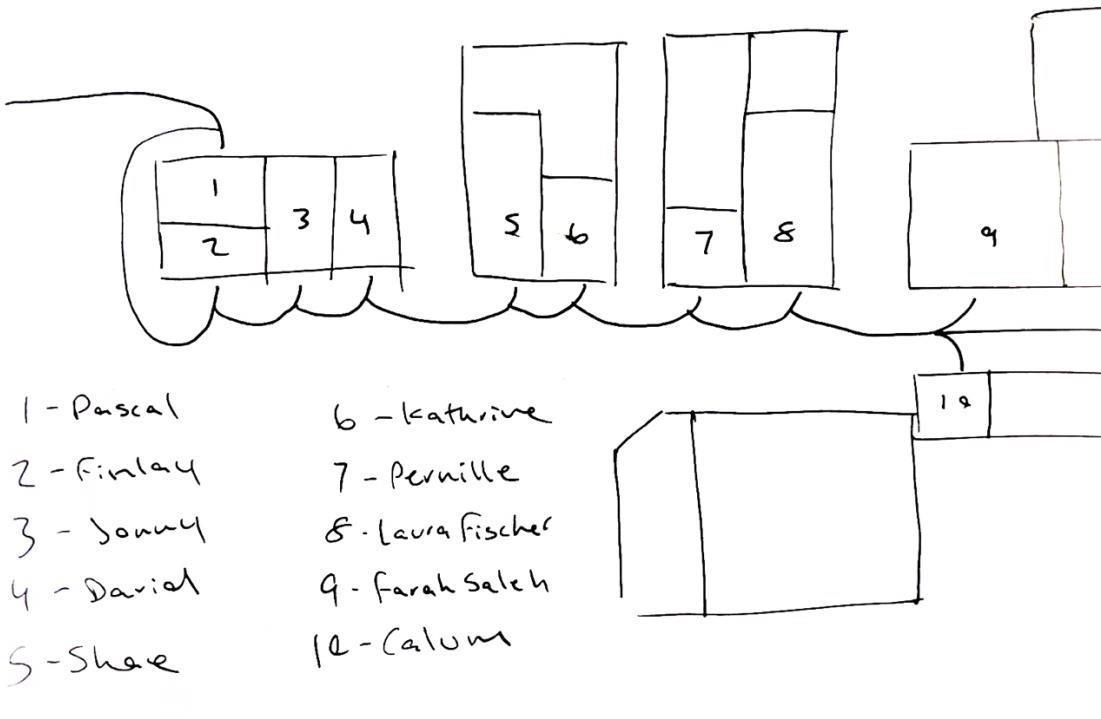

The work of ten artists will be displayed at The Keiller Centre in Dundee, Scotland. Each artist will be curated within an individual unit. The centre was built as a shopping centre in 1979 and is a non-traditional exhibition venue (The Keiller Centre, 2023). There will be a program of live performances at the opening event, intending to activate a performance energy within the centre (See Appendix E, p. 42).

1

Pulling, quite literally, with the connections between drawing and the human body, multimedia artist Pascal Miehe explores our embodied connection to drawing and line (Miehe, 2023).

Commenting on societal systems of dominant power and expanded multiplicity, he creates work ranging from drawings to woodcuts, from paintings to performances. Miehe assumes the roleofdirectorforhisperformancework,whichisfrequently enacted byagroupofperformers.

Miehe created and exhibited this performance work, alongside the rope and woodcut prints, as part of his MFA Drawing studies. ARENA invites the audience, through the video and the object, to embody the immense power and strain that the performers are undergoing whilst pulling at a five-way tug of war. The inclusion of the rope in the unit adds a layer of tangibility for the visitor to interact with, but it also exemplifies the absence of the performer.

Thisvideodocumentand interconnectedropeissituatedinthefirstunitatthenorthernentrance to The Keiller Centre, running parallel to the work of David H Sherry in the next unit.

14

Figure

Through isolating actions in an attempt to understand what influences our human behaviour and opinions, artist David Sherry uses drawing, sculpture, and performance to highlight the actions of the ordinary, in regularly quite a humorous and evocative way (Sherry, 2017). His performance work varies from the heavily scripted, to the process of improvisation, giving the work a space to figure itself out (Sherry, 2023).

Inspired by the work of Steven Parrino (Art Basel, 2018) whilst speaking with a collector who knew Parrino, on a trip to Basel Art Fair, Sherry made this work Living the Dream After Death (See Appendix F, pp. 46- 47). Existing in the space will be the canvas object accompanied by the photograph of Sherry performing the piece in Germany. His absence in the object will encourage the visitor to contemplate what the space would feel like if Sherry was inhabiting the object like when initially live.

This work is placed along the back wall of the unit, with the photograph accompaniment arranged to the right of the work, prompting the audience to explore the object first, before seeing the photographic document of the live moment.

15

Figure 2

Figure 3

Glasgow-based artist collaboration between Shae Myles and Chao-Ying Rao will be situated in the next unit. Myles’ interdisciplinary practice expands ideas of play theory, consumer culture, femme aesthetics and secret obsessions (Myles, 2023). Also performing in this work is Chao-Ying Rao (Betty), an East Asian performance artist based in Glasgow (Rao, 2019). Negotiating complex ideas of narcissism, objectification and femininity, Betty’s work pulls from her lived experiences of the sex industry.

Inspired by the world of the 1990’s Polly Pockets compacts, this work Hush Lil Baby is exhibitedasalife-sizedsculpturalinstallation.Positingtheaudienceattheintersectionbetween the themes that the artists explore, one will be left to ponder the installation, to form a relation to what took place, much of what intends to be influenced by the audiences own recalled childhood associations.

Positioned between the work of Sherry and Hall, this work separates the idea of the document being solely existent through relations to video or photographic media.

16

4

Performance, sound, and events are the forte of artist Finlay J Hall in the next unit. Stemming from themes of DIY, collective action and music, Hall adopts a learning by doing attitude in the execution of his work(Coatham, 2022). Typically humorous, and interactive, Hall employs this DIY trait to create props and objects that become his modes for performing within.

For his work Party Machine, he created a box to be performed with in the basement of what was then called The Wild Rover, for the performance night Dain Hings. Situated in the centre of the space, the audience became involved as the balloons periodically emerged from the box that Hall was in. In The Keiller Centre unit, the video and the object will be paired together with the interaction of blown-up balloons positioned in the space.

This work is in the last unit of the first block at the northern wing of the centre, coming after the work of Myles and Betty, adjacent to the work of Kathrine F Allan.

17

Figure

Figure 5

Kathrine Fay Allan encompasses the connections between art, philosophy, and life sciences in her work. Intertwining sculpture and installation with the natural world, like plants, insects, and water, she culminates work that evokes an embodied relation to the senses, our own ecology, and the consideration of therapeutic care (Allan, 2023). This idea of care is something that translates into the roles she assumes for her performance work.

In this work, first shown at her degree show (Allan, 2019) and later selected for the RSA New contemporaries 2020 (Royal Scottish Academy, 2020),weseeAllan assume theroleofanurse. Balancing between the states of sickness and wellness, she evokes the feelings experienced by those undergoing treatment, but also by those at the bedside. Blurring the margins between the outside world and the patient bay, the work transports audences into a prolonged space in time, much like the experience of being in hospital.

Incorporating the living installation, alongside the audio piece and programmed live performance on the opening night, the work will prompt a sensory experience for those that encounter it.

18

Working within performance and moving image since the mid 90’s, Pernille Spence has explored the intrinsic connections between the human body and movement in space. The physiological and psychological limits of the body have been tested in her many daring performance works, from skydiving to being elevated from the ground by giant weather balloons (Spence, 2020).

In this work NaCl, Spence experiences the weight of one ton of salt pouring over her head, collecting inside the box, of which she stands in. Pulling from the idea of the failing body and salts medicinal preservation value as a mineral, Spence is subject to a continuous shower that encases her body entirely. What one may see as a ritual healing or spiritual practice, in fact is actually one of danger, due to the balance of salt and liquid in relation to the body. The salt in reality is drawing fluid from the body, until it leaves the body incapacitated.

The partially salt-filled box will exist within the space, alongside its video document, promptingtheaudiencetorecallthebodythatwas oncethere.Theabsenceofthisbodyrequires theaudienceto draw embodied relations to theweight ofthesalt and theclaustrophobicmanner of the performance.

19

Figure 6

Figure 7

Jonny Lyons pairs sculpture, photography, and performance together to create his dramatic scenes of action and aftermath. His surreal yet familiar concepts are evocative of the fragility of friendship and the natureof mischievous endless youth. Handcrafted devices are paired with photographic images or film, alluding to physical humour like silent cinema. Lyons functional sculptures then take on a new life as relics of the event, alongside the photographic evidence of the act (Jones, 2016).

Despite the predictability of cause and affect presented in Lyons’ images, the work still has a poignant impact and vulnerability. His work The Sheltering Sky in the unit, offers audiences an opportunity to inspect the photographs on the wall to derive adepiction of theliveevent, whilst relating the photographs to the accompanied performance tool, a smoke bomb, in its crafted wooden box (Ingleby Gallery, 2015).

Presenting the objects paired with the photographs build a tangibility between audience and document. Presented first-hand are the objects used to produce the outcome that the performance photographs depict. From the evident absence in Spences work previously, a purposeful jump is made here to indicate the material object used by the performer during the live event captured.

20

Figure 8

Considering space as an artistic practice and political collaborator, the artist Laura Fischer expands notions of dance, live performance, and installation through the lens of disability. Touching on non-human movement and audience embodiment, they explore site responsivity through expanded dance interactions with material (Fischer, 2023).

In their commissioned work FORGED, recently performed at ‘Take me Somewhere Festival 2023’ inGlasgow, the spacetransforms into a sculptural installation, built between theintimate connection of copper metal and Fischer over the festivals run (Wishart, 2023). A transfer of body heat is exchanged during cycles of moving and resting. The disabled body is enabled and supported by the exchange of body heat into the metal sheets. Through this physical collaboration of bending, heating, cooling, and resting, we see the metal transform into a sculptural presence. The space is in constant flow of change, each performance act leaving imprints of the performer on the metal.

The document of the performers absent presence is ever more evident through the intimate traces left behind on the metal sculptures. Audiences are left to recall the movements that took place between body and object through examining the durational embodied sculptures presented.

21

Farah Saleh, aPalestinian dancer, andchoreographer, works across many artistic and curatorial projects. Ideas of prominence and resonance in the body are explored through an embodied knowledge and decolonial lens. Space becomes activated through the presence of the performer, but also an audience’s interaction with objects, attributing a new participatory aspect to the work (Saleh, 2023).

For me the performance also disseminates and exists in an afterlife because of the experience that people have, me personally as a performer, but also the people who came and experienced it (Saleh, 2023, see appendix G, p. 45)

Performed at GOMA in 2022, by Saleh and collaborator Mirjam Sögner, What Does the Space Know combines installation with performance (Gallery of Modern Art, 2022). An investigation is presented around the resonance of the body in architectural space. Audiences of the live event are prompted to engage memory through a guided imagination of temporary relative embodiment. Activated objects andtheperformers guidetheaudiencethrough an observational journey. Only after the live event does one get the chance to contemplate and arrange the contexts for what was witnessed.

This piece has been allocated the largest unit. This is to accommodate the expanding nature of the object documents, and to prompt audience participation in the work, activating the space. The unit will be in a constant flow of performance.

22

Figure 9

In the final unit of the exhibition is artist Calum Eccleston. Working with the ephemeral heritage of performance art, more specifically in response to the Alastair MacLennan Archive at the University of Dundee, Eccleston addresses the unseen absences that sometimes evade modes of traditional archiving (Eccleston, 2023).

Take Leave was performed live at the Duncan of Jordanstone Research Expo in 2023. The scroll, face casts and other objects were all used within the live performance to produce the final artwork displayed for the remainder of the exhibition. This installation became the documentof theperformance. Pulling andreacting to theworld around him, Eccleston outlined shadows, scribed words, and translated thoughts onto the scroll in front of him.

Opting for a smaller and more contained unit for this work was in response to the nature of which the performance was initially conceived. The audience present at the live creation of the work will be unaware participants in its final outcome. Containing the document within this space hence encourages thought towards participation in audiences encountering live performance.

23

Figure 10

Floorplan:Exhibitionlayout

The choice of curating individual artists within their own unit has resonance within the nature of how people view works of performance through their document. The works are not collectively curated within one open space, making it less immediate to draw contrasts and opinions directly between works when moving from one unit to another. This puts emphasis on the audience to extract connotations about the exhibition though their recalled experience, rather than when in the subjective moment. For full centre plan (See appendix A)

Miehe, P. (2023) ARENA.

Sherry, D. (2010) Living the Dream After Death.

Myles, S. (2023) Hush Lil Baby.

Hall, F.J. (2023) Party Machine.

Allan, K.F. (2019) The Rest of Us… We Just Go Gardening.

Spence, P. (1995) NaCl.

Lyons, J. (2014) The Sheltering Fischer, L. (2023) FORGED (in the tender heat of your embrace).

Saleh, F. (2022) What Does the Space Know.

Eccleston, C. (2023) Take Leave.

It is noteworthy to mention that the choice to only include static documented images of the artist's work in this written project, originates from the inherent significance I attribute to this exhibition. As you read this project, you are immersing yourself in the performances through the photographic documentation provided, mirroring the intended experience of encountering the work in person during the exhibition. This fosters a more profound connection to the underlying concept of the project.

24

Figure 11. Exhibition Floorplan

ChapterThree:CuratorialAimsandInfluences

UnconventionalExhibitionSpaces

The Keiller Centre in Dundee stands as a testament to the transformative power of unconventional exhibition spaces. Once a thriving shopping centre of the seventies and eighties, The Keiller Centre now faces the challenge of vacant units and shuttered storefronts. However, the centre’s management has opposed the fate of demolition, breathing new life into the space by repurposing it for cultural endeavours. The Keiller Centre has become a hub for community, culture, and creativity; hosting art galleries, workshops, and events like the Dundee Fringe (2023).

This unconventional venue provides a distinctive backdrop for the presentation and appreciation of contemporary performance art. The contrast between the original purpose of the shopping centre, and its newfound role as an art space, adds an element of surprise for audiences encountering these works. The selected units in the centre are transformed into a 2week exhibition within the once purely commercial confines of The Keiller Centre.

The utilisation of this non-traditional model echoes the sentiments explored in the Shopping Centre Investigations Project, based in the old Konalanvuori Shopping Centre in Helsinki (Pohjolainen and Valle, 2022). Starting as a blog by artists Miina Pohjolainen and Salla Valle, theproject aimed to investigatetherepurposing of spaces originally occupied forconsumerism, by hosting a program of exhibitions, workshops, screenings, and archival research days. Aligning with the idea of turning the mundane into the extraordinary, the project looked towards transforming a symbol of retail decline into a thriving cultural base.

Finland, in the year 2000, within the field of urban planning, implemented a requirement for the participation of residents into legislation, with a participation and interaction plan being drafted for each urban city development to this day. In her exploration of Finnish government guidelines, Lauri Siisiäinen relates these participatory measures within the shifting process of governance and government (Siisiäinen, 2019).

Governance is more horizontal than government, and it takes place through autonomous, informal and flexible communities and networks, whereas government is thought to work from the top down and in a centrally controlled manner (Pohjolainen, 2022, p. 105)

25

Miina Pohjolainen's concept of ‘Participation as a Symptom of Knowledge-Based Economy’ comes into play here, as these unconventional venues become sites of artistic engagement. Her focus in this chapter is on the intersection of art and urban development, with emphasis on participation as a democracy (Pohjolainen, 2022). In the face of urban development and retail decline, these shopping centre spaces have become vital participatory arenas for audiences to interact with art. Participation in art becomes crucial when discussing urban development within our knowledge-based economy, offering a way to navigate this shift from government or governance. At the forefront stands fostering community involvement, and transforming urban spaces into meaningful, accessible, and democratic sites. The Keiller Centre's revival exemplifies this shift from passive observation to active engagement, turning a space of commerce into one of communal participation.

The act of participation relates into our associations of public art. Much like the pillars of performance art, public art dematerialised the art object in favour of a democratised accessibility to art.With this unconventional spatial connection comes the reinforcement of the link between performance art and life, as fundamental to understanding the significance of utilising unconventional space.

Public art and public art museums brought high arts to the common people, with a patronising attitude. Opportunities for experiencing art were created from the top down, to educate the uncivilised nation (Ruohonen, 2013).

The White Cube gallery, therefore, can no longer be considered the standard exhibition space. For art to be encountered by wider public audiences, the work must be situated within the structures of daily existence. A contrasted and opportunistic setting like The Keiller Centre is perfect for promoting this connection between art and the audience; art and life.

IntendedAudience

The exhibition will primarily cater to a discerning audience of critical and academic individuals, deeply engaged with the nuances of performance art. This primary audience, comprising scholars, students, curators, and practitioners intends to foster a profound questioning of the ephemeral nature of performance through its proposed document. Through the curatorial decisions made, the exhibition intends to offer a scholarly discourse, contextualising each artwork within the broader commentary of the live performance, whilst offering an open discussion on the validity of the document.

26

While the primary audience is crucial, the secondary audience of the general public plays an integral role in the exhibition's impact. The curation strikes a delicate balance, employing accessible narratives and engaging displays to make the content more approachable for those unfamiliar with the intricacies of performance art. The intention is to bridge the gap between specialised knowledge and public understanding, fostering a broader appreciation for this dynamic art form, much like how performance art initially advocated.

The gallery is consistently used as a means to reproduce specific sets of relations, both between the artist and their audience, but more importantly between the curatorial object and its reception. (Hao, 2014)

Carefully orchestrated curation has a significant influence on the audience experience. In this case, an encounter transforms into active participation in the artistic process. As the audience navigates through the curated collection, they are encouraged to perceive themselves as potential collaborators in the ever-evolving act of performance. The narrative unfolds, not as a mere presentation of documents, but as an invitation to explore the boundaries between audience and performer.

EncounterbecomesAudience,becomesParticipant

Performance is encapsulated in the transitory interplay between the performer and the audience. This understanding prompted Peggy Phelan to conceptualise performance as inherently irreproducible, a phenomenon that ‘becomes itself through disappearance’ (Phelan, 1993). Despite challenges to Phelan's ideas in the context of evolving media technologies, her emphasis on the audience's integral role endures how we encounter works of performance art (Auslander, 2007). Adrian Heathfield, for instance, characterises performance as a physical relationship between the art and its audience and subsequently art within its surrounding domain (Heathfield, 2009).

It is essential to recognise that while an encounter can signify an unexpected meeting, it also implies engagement in conflict. Through performance, the simultaneous assumption of both positions encounter as meeting and encounter as conflict is not only possible but desirable when in a public sphere. This duality is achievable because performance, inherently challenging on social, political, formal, and commercial fronts, allows for the coexistence of opposing forces. Performance artists predominantly navigate tension within the art world,

27

where the unpredictability presents both liabilities and potentials, particularly from an institutional perspective. Embodied, timely, and critical, performance holds the potential to simultaneously resist and destabilise hegemonies of power, extending beyond the confines of the art world.

Performance art shares the language of protest (Gascoigne, 2012).

The notion that performance provides a space for resistance serves as a means to disrupt power structures. Hence why there is a potential for unpredictable and antagonistic encounters to be produced positively. Performance remains open to the unknown due to the agency it grants. As Heathfield suggests, it is concerned not only with the physical relationship to the act and the actions of theperformer, but most critically, to that of the actions and reactions of the audience. This raises the question: who possesses the empowerment to act in this dynamic the performer, the audience, or both?

Claire Bishop contends that participatory art redefines the audience's role, positioning them as active contributors, rather than passive observers (Bishop, 2022). Participatory art, much like public and performance art, challenges conventional boundaries, prompting individuals to become co-creators in the artistic process. This dynamic shift from audience to participant fosters a sense of agency and communal involvement, generating a reflective dialogue through the questioning of the art objects presented.

Inthis exhibition, an encounterbecomesan audience, thatbecomes aparticipant. Thecuratorial choice of the units helps emphasise this by prompting the audience of the documents to recall their own contexts and ideas about a performance through the captured media or objects remaining. This resonates with the transformative power of participatory art situated in unconventional spaces, creating democratic environments where art integrates into daily existence.

28

ChapterFour:OtherCuratorialInfluences

ForgingConnections

Curation, at its essence, is an act of care an intentional selection and arrangement that speaks to a curator's understanding, appreciation, and connection to the chosen works of the artist. In my pursuit of curating an exhibition centred on performance art documentation, I made a deliberate choiceto focus onartists primarily operating out ofScotland. However, my selection process extended beyond mere geographical proximity. I sought artists with whom I could forge a direct and personal connection with. Albeit this exhibition exists under hypothetical terms, the value I placed on choosing artists within my reachability was not purely logistical, but an intrinsic part of creating a more profound and meaningful curatorial experience.

In hopes of gaining greater purpose in this project, proximity and accessibility became a catalyst for forging connections. My selection process stemmed from a desire to cultivate a stronger connection, not just with the works themselves, but with the individual artists behind them. Having had the opportunity to witness performances live or experience them through their documentation in person, I was provided with a tangible connection that went beyond the confines of a gallery or a book when it came to conversing with the artist. The physical proximity also allowed me to immerse myself in the art scene of Scotland, fostering a deeper sense of shared experience and understanding. This direct communication I feel aided in bridging the gap that sometimes exists between establish artist and art student.

Of the ten selected artists, I engaged directly with six. A decision driven by the conviction that a curator's role extends beyond passive observation; in that so too does performance. Through discussions, conversations, and correspondence, I sought to unravel the layers of their artistic processes, inspirations, and intentions. The act of reaching out and engaging in dialogue transformed the curation process from a detached selection of artworks into a dynamic and collaborative venture.

The meaning of curation as an act of care took on a personal dimension. It became about not only caring for the artworks in the context of situating them, but also for the narratives, intentions, and nuances that the artists initially embedded within their original work. As the work is being resituated within this exhibition, I pulled questions that arose from my research into our discussions about their work. Communication fostered a sense of mutual respect and

29

understanding, reinforcing the idea that the curator is not a distant observer but an active participant in the artist's journey.

Exhibitions should develop a life of their own, more like a conversation between curator and artist than an arrangement of their work to suit a pre-existing idea (Obrist, 2015, p. 87).

A conversational catalyst. Theroleof the curator reacts likea chemical catalyst thatdisappears, so too like history. We may then also attribute this philosophy toward the document of performance. The live act becomes the chemical catalyst that is no longer present, yet remains in the knowledge of recollection, of what took place, its document.

HansUlrichObrist

In my explorative reading for this project, I took my summer to read about the work of Hans Ulrich Obrist in his book Ways of Curating (Obrist, 2015). I was instantly fascinated by his philosophy of curation as a conversation. Reading about his early conversations and meetings with artists like Peter Fischli and David Weiss were captivating for me in understanding the true relationship of artist and curator. Placing an emphasis on the work of collaboration and dialogue led me toward implementing this into my own process of researching and curating for this project.

Once again the role of the curator is to create free space, not occupy existing space (Obrist, 2015, p. 154)

Obrist emphasises the need to adapt to the evolving dynamics of contemporary art. In doing so I found his introduction to his own practice fascinating. His work with unconventional conditions, from the cupboards and appliances of a kitchen for a group show, to helping realise a project with Alighiero Boetti in every plane of an airline for a year, was fascinating (Obrist, 2015, p. 11). This provided me with a confidence in understanding the concepts of exhibition making in unconventional spaces.

Marina Abramović

As well as Obrist’s insights, I made a point of travelling to exhibitions to gain a physical sense of what I was hypothesising. In early December of 2023 I travelled to the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) in London to visit the final month of Marina Abramović’s retrospective exhibition

30

(The Royal Academy of Arts, 2023). The exhibition showcased a comprehensive collection of Abramović’s career defining performances. Upon entering, I was interested to see how the curators used the galleries of the RA to display the documented works. As imagined with a large-scale institutional show, the expanse of resources available constructed a spectacle of the work. Nevertheless the curation remained inventive. From expanses of selected photographs, videos and object artefacts, each space was transformed to relate to a different period of Abramović’s artistic expression. With a balance of programmed live performances and documented work, the audience became encapsulated as a participant in a constant state of performance, further inspiring me to incorporate this philosophy into this project.

I cannot do anything without an audience, I need their energy (Abramović, 2023)

I became engrossed in observing not just the artworks and live performances, but how the general public audience interacted with and responded to the works. This was a unique opportunity for me to witness how people interact with performance art, be it live or when separated from its temporal act in document form. This exhibition solidified my knowledge in validating that there is a lasting impact for the curated document of performance in a curatorial landscape.

To round off my observation, I was amazed at how many people were using their own phones as a means of photographing the documents. There now exists a document of a document of a performance. I felt this comfortably rounded off my research and exploration into how interactions with artworks and performance documents operate in our contemporary society.

31

Conclusion

This exhibition is an essential addition to the conversation around the validity and documentation of performance art for re-exhibition. By intending to ensure an open dialogue across a scope of audiences, the exhibition employs accessibility and engagement as an art form, to produce and amplify the voices of performance artists within contemporary art. In activating the space with encountering audiences, the space itself becomes a constant site of performance, with the audience as participants. Roaming from unit to unit, the audience will expand their notions of what art can do and how it can be experienced. Much like how we are attuned to experience artworks and documents of performance today. The recalled experience is superior to the subjective moment.

The prevalence of the White Cube, as the sanctioned space for showcasing contemporary art, hinders the communicative impact of such artworks in our broader world. This is a result of associations with commodification, excessive detachment, and a sense of exclusivity. This limitationconstrains theartwork's capability toengagewith amorevaried audienceandcurtails its potential to instigate shifts in artistic pedagogy and, by extension, society. As exemplified by this proposed exhibition, performance art and their documents would benefit from being situated in a dynamic environment that stimulates critical dialogues involving encountered space, the audience, and documentation. The Keiller Centre stands as a testament to these operational ideals, expanding our method of exhibition making.

Embedded within the essence of performance art lies the daring spirit to defy conventions. To introduce a concept exceeding the established norms of artistic creation. In moments of profound crisis, turmoil, and injustice, performance art emerges as a folded testimony to usher in change. It is through the most impactful performances in history that we gain profound insights into our shared human experience, prompting us to scrutinise the notions of artistic legitimacy. Championing the accessibility of this art form will further broaden the impact of art. This form of expression and its crucial document, serve as an imprinted narrative of our past, guiding us in shaping the trajectory of our future.

32

References

Abramović, M. in Dinneen, S. (2023). Marina Abramović at the Royal Court: As harrowing and vital as ever [online] CityAM. Available at: https://www.cityam.com/marina-abramovicat-the-royal-court-as-harrowing-and-vital-as-ever/ [Accessed 9 Jan. 2024].

Allan, K.F. (2023) About. [online] Available at: https://www.katherinefayallan.com/aboutme-15 [Accessed 23 October 2023].

Allan, K.F. (2019). ‘The Rest of us... We Just Go gardening’. [online] Katherine Fay Allan. Available at: https://www.katherinefayallan.com/therestofuswejustgogardening [Accessed 23 October 2023].

Art Basel. (2018) Steven Parrino, 13 Shattered Panels (for Joey Ramone), 2001. [online] Availableat:https://www.artbasel.com/catalog/artwork/85761/Steven-Parrino-13-ShatteredPanels-for-Joey-Ramone [20 September 2023]

Auslander, P. (2006) ‘The Performativity of Performance Documentation’ PAJ (Baltimore, Md.), 28(3), pp.1-10. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1162/pajj.2006.28.3.1 [22 August 2023]

Auslander, P. (2008) ‘Liveness: performance in a mediatized culture’. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Auslander, P. (2007) ‘After the Act: The (Re)Presentation of Performance Art’ Nürnberg: Verlag Moderne Kunst.

Bishop, C. (2022) Artificial hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso.

Birringer, J. (1991) ‘Video Art / Performance: A Border Theory’, Performing arts journal, 13(3), pp. 54–84. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/3245541. [17 September 2023]

Coatham, C. (2022) Q&A: Finlay J Hall. [online] WORKSITE. Available at: https://wwworksite.wordpress.com/2022/05/02/finlay-j-hall/[12October 2023]

Dundee Fringe (2023). Dundee Fringe [online] Available at: https://dundeefringe.com/ [18 October. 2023].

Eccleston, C. (2023) University of Dundee, UK. [online] Available at: https://www.dundee.ac.uk/djcad/research/students/eccleston [21September 2023]

Ferdman, B. (2014) ‘From Content to Context: The Emergence of the Performance Curator’.

Fischer, L. (2023). About| Dance Artist | Laura Fisher Performance | Producer | Scotland. [online] Available at: https://www.laurafisherperformance.com/artist-statement [09 October 2023].

Gallery Of Modern Art (GoMA) Glasgow. (2022). Gallery Of Modern Art (GoMA) GlasgowWHAT DOES THE SPACE KNOW |Farah Saleh & Mirjam Sögner | Sunday 2 October 3pm. [online] Available at: https://galleryofmodernart.blog/what-does-the-spaceknow-farah-saleh-mirjam-sogner-sunday-2-october-3pm/ [12 October 2023].

33

Gascoigne, L. (2012). Will Performance Art Tank? [online] www.prospectmagazine.co.uk. Availableat:https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/culture/50408/will-performance-art-tank [14 October 2023].

Gitonga, G.D. (2023). ‘Performance and Visual Art 101: Curating Performance’. [online] Available at: https://www.byarcadia.org/post/performance-and-visual-art-101-curatingperformance. [18 October 2023]

Glendinning, H and Heathfield, A. (2004) Live: Art and Performance. London: Tate Gallery

Hao, S.Y. (2014) ‘Attending the Gallery’ in Remes, O., MacCulloch, L. and Marika, L. Performativity in the gallery: staging interactive encounters New York, NY: Peter Lang. pp, 191 – 204

Heathfield, A 2009, It's a Bit Trippy: Difficult Artforms and Different Audiences. In Frank, T and Waugh, M (eds), We Love You: On Audiences. Frankfurt: Revolver. pp, 72 – 87

Ingleby Gallery. (2015). Jonny Lyons, The Sheltering Sky, 2014. [online] Available at: https://www.inglebygallery.com/artists/47-jonny-lyons/works/54394-jonny-lyons-thesheltering-sky-2014/ [25 September 2023].

Jones, S.U. (2016) Photographer Jonny Lyons Captures a Precipitous Reality. [online] The Herald. Available at: https://www.heraldscotland.com/life_style/arts_ents/14242309.photographer-johnny-lyonscaptures-precipitous-reality/ [25 September 2023]

Kaye, N. (2000) Site Specific art: performance, place, and documentation. London: Routledge

Kessels, E. (2020) ‘Onlookers Versus Participant’, in Idema, J. A Spectator is an Artist Too: How we Look at Art, How we Behave Around Art. Amsterdam: Bis Publishers, p.5.

Koons, J. (2009). Art Changes Every Day. [online] Available at: https://art21.org/read/jeffkoons-art-changes-everyday/#:~:text=It's%20not%20about%20the%20object,that's%20where%20the%20value%20is [04 December 2023]

Lippard, L.R. (1997) Six Years; the dematerialisation of the art object from 1966 to 1972. Berkeley. University of California Press. [25 August 2023]

MacLennan, A. (2020). Alastair MacLennan Interview. [online] Available at: https://amaclennan-archive.ac.uk/2020/11/18/alastair-maclennan-interview-november-2020/ [15 September 2023].

McLuhan, M. (1964) Understanding media: the extensions of man London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Miehe, P. (2023) Statement. [online] Available at: https://www.pascalmiehe.com/statement [18 September 2023]

34

Myles, S. (2023) Shae Myles. [online] Available at: https://www.shaemyles.com/ [26 October 2023]

Obrist, H.U. and Raza, A. (2015). Ways of Curating. New York: Farrar, Straus And Giroux.

O’Dell, K. (1997) ‘Displacing the Haptic: Performance Art, the Photographic Document, and the 1970s’ Performance research, 2(1), pp. 73–81. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.1997.10871536 [27 August 2023]

O’Doherty, B. (1999) Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space. Berkley: University of California Press.

Omlin, S. (2011). ‘Perform the Space: Performance Art (Re)Conquers the Exhibition Space’. Performing the Exhibition, Oncurating.org [online] (15), pp.3–12. Available at: https://www.oncurating.org/files/oc/dateiverwaltung/old%20Issues/ONCURATING_Issue15.pdf [14 November 2023]

Ortiz, J. (2012) How to Curate Performance Art, and Other Problems. Hyperallergic [online] Available at: https://hyperallergic.com/62007/how-to-curate-performance-art-and-otherproblems/ [27 September 2023]

Phelan, P. (1993) Unmarked: the politics of performance. London; New York: Routledge.

Pohjolainen, M. and Valle, S. (2022) ‘Participation as a Symptom of Knowledge-Based Economy’, in Toim. (ed.) Ostaritutkimuksia – Shopping Mall Investigations. Helsinki: Taideyliopiston Kuvataideakatemia. pp, 103 - 111

Rao, C-Y. (2019) About. [online] Available at: https://chaoyingrao.wordpress.com/cv/ [27 October 2023]

Royal Scottish Academy. (2020). Works - RSA New Contemporaries 2020 [online] Available at: https://www.royalscottishacademy.org/exhibitions/6/works/image27/. [23 October 2023]

Ruohonen, J. (2013) ‘Looking at the new society: Public art policies in post-war Finland’. University of Turku: Tahiti journal 1/2013. Available at: https://tahiti.journal.fi/article/view/85477/44427#JR2 [27 October 2023]

Saleh, F. (2023). Palestinian Choreographer | Farah Saleh Website. [online] mysite. Available at: https://www.farahsaleh.com/ [16 October 2023]

Schimmel, P. (1998) ‘Out of actions: between performance and the object 1949-1979’ [published on the occasion of the exhibition held at the Museum of Contemporary Art at the Geffen Contemporary, Los Angeles, 8 February - 10 May 1998; Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, 17 June - 6 September 1998; Museu d’Art Contemporani, Barcelona, 15 October 1998 - 6 January 1999; Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, 11 February - 11 April 1999]. London: Thames and Hudson.

Sherry, D. (2023) In Conversations with David Sherry & Sara Damaris Muthi. 22 Nov. Catalyst Arts [online]

35

Sherry, D. (2017) Statement. [online] Available at: http://www.dave-sherry.com/DaveSherry-Statement.html [20 September 2023]

Siisiäinen, L. (2019) ‘Participation steered by governance reinforces power relationships’ in Participate! Will participation save democracy? Ed. Meriluoto, T and Litmanen, T. Tampere: Vastapaino. pp. 95 – 122.

Spence, P. (2020) About. [online] Available at: https://www.pernille-spence.co.uk/ [22 October 2023]

Tate (2017) White Cube [online] Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/w/whitecube [22 November 2023].

The Keiller Centre. (2023). The Keiller Centre. [online] Available at: https://www.thekeillercentre.com/ [14 October 2023].

The Royal Academy of Arts (2023). Marina Abramović | Exhibition | Royal Academy of Arts. [online] Available at: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/marina-abramovic [28 November 2023]

Warr, T and Jones, A. (2000) The Artist’s Body. London: Phaidon Press.

Wishart, S. (2023). LAURA FISHER - FORGED (IN THE TENDER HEAT OF YOUR EMBRACE). [online] Take Me Somewhere. Available at: https://takemesomewhere.co.uk/laura-fisher [09 October2023]

36

Appendices

AppendixA:Floorplan

Hereis thecorporate floorplan for TheKeillerCentre, complete with highlighted selections for the units utilised in the exhibition.

37

38 AppendixB:

AppendixC:Unsuccessfullayouts

Whenexploring ideas for allocating artists to units Iencountered questions that influenced how I wanted to curate the exhibition. To prompt the audience to ponder different methods of documentation, I spread out variations of documentation methods throughout the exhibition.

These considerations took the form of identifying the types of documents that would be exhibited within the spaces. Spreading out the work of objects vs video or photographic documents.

I ultimately noticed also that the layout above unintentionally segregated with works by assumed gender. This was not something I felt comfortable with as I felt it created a negative narrative for people to examine the artists as separated by gender, which was in no way the intention of this exhibition. So, this was rectified.

39

AppendixD:Notesonreperforming

The concept of re-performing the work of performance art through the exhibition of documented counterparts raises intriguing questions about the preservation and recreation of the live experience. When an audience encounters documented representations of a performance, whether through photographs, videos, or other mediums, the exhibition inherently engages in a formof re-performance. However, the challenge lies in determining the exhibition'sintent isittofaithfullyrecreatetheliveperformanceortoestablishanew,distinct experience? I’d argue the later. The exhibition may unintentionally employ strategies to overstimulate the space, incorporating sensory elements that recall the original moment, but this should be avoided. The curation should evoke the visceral sensations of the live performance through only a recalled experience that is relative to the individual audience member. In doing so, the exhibition seeks to bridge the temporal gap between the documented past and the present audience, offering a heightened and perhaps altered encounter with the artistic expression. The intention might not be a mere replication but rather a reinterpretation through discussion with the artist, re-establishing the essence of the performance in a way that resonates with contemporary issues. In this dynamic interplay between documentation and reperformance, the exhibition becomes a space for both reflection on the past and the creation of a unique, immersive encounter that transcends the boundaries of time and space.

40

AppendixE:Exhibitioninformationandliveperformanceschedule

At the opening event of the exhibition, there will be performances by five of the exhibited artists. The choice to incorporate live performances into the exhibition centred on the validity of the document is to emphasise that the document can only exist due to its live counterpart. In this case, the artists performing live are activating the space, inviting, orincluding the audience directly within the work. After the live performances, the exhibition will exude a sense of historical value. This will be especially in the case of object-based performances that will leave object traces as their document for the remainder of the exhibitions run.

Exhibition running for 2 weeks.

Opening event from 12pm midday until 5pm, with performances scheduled within this time (see below)

The Keiller Centre opening times:

Monday 09:00 – 17:00

Tuesday 09:00 – 17:00

Wednesday 09:00 – 19:30

Thursday 09:00 – 17:00

Friday 09:00 – 17:00

Saturday 09:00 – 19:30

Sunday 09:00 – 18:30

From the above opening times of the centre, it would appear that a Wednesday, Saturday, or Sunday would be most ideal for the opening event. To try and engage as wide an audience as possible I would be inclined to choose the Saturday option to ensure people working during the week would make the event.

Live performance schedule:

12:30 – Farah Saleh and Mirjam Sögner (40 minutes to 1-hour performance duration)

13:45 – Calum Eccleston begins (estimated 3-hour durational performance)

14:30 – Finlay J Hall begins (estimated 15 to 30 minutes performance duration)

15:15 – Laura Fischer begins (estimated 45 minutes performance duration)

16:15 – Kathrine fay Allan begins (estimated 30-minute performance duration)

The above schedule is an idea towards how audiences would be able to encounter the works at different stages. Some may see a performance start; some may see it end. There is a festival idea to the live performances on the opening night, offering people the chance to move freely from place to place around the centre across the days event.

41

– 31October2023

Discussing the idea of maintaining ephemerality within a performance. Doing the performance behind closed doors. Exploring the idea of creating a myth or a persona by using a fake name and fragments of someone else's life, leading to the creation of a concrete life mask.

Discussion around the ambition and restrictions of artistic expression, particularly in relation to documenting and presenting performance art. Emphasises the constant open discussion about why they document, why they show the document, and how audiences interpret it.

The concept of the absence of presence is highlighted, suggesting that the artwork aims to provoke thought towards a recollection by creating a provocative image that evoke the previously live moment audience, prompting imagination.

Focus on why documentation is important and how it contributes to the overall understanding of art. Acknowledging the limitations in answering questions about the artwork all but emphasises the importance of discussion throughout the process.

Theuseof provocative imagery, which serves as a tool to evoke emotions, prompt recollection, or stimulate the imagination of the audience.

Reference is made to the work from the 70s, suggesting a consideration of temporal context in performance art and acknowledging the artist's personal timeline in relation to the historical context of the work.

42

AppendixF:Notesfromconversationswithexhibitedartists

– 02November2023

Conversation around the nature of performance art, emphasising its ephemeral quality and the shift towards existing primarily through documentation. The role of documentation in performance art, with a focus on how the absence of live presence contributes to the artistic experience.

Discussing the considerations and decisions involved in documenting a performance for ARENA, particularly in the context of the space where it is presented. Exploring how video documentation allows for a more controlled and intimate audience experience compared to live performances where perspectives vary. Touching upon the physical layout of the exhibition space, considering how each artist's work will be presented and its impact on the audience.

Related to the issues surrounding ARENA when exhibited.

Thoughts on curating an exhibition dissertation, including the selection of local artists, the challenge of balancing various elements, and the impact of documentation on audience perception.

Questioning Live vs. Documented Performance. Questions around the distinction between live performances and their documented versions, pondering whether presenting documented works as live performances is a form of reperformance. Discussing the theme of "presence and absence" as a unifying factor in the selected artworks for the exhibition dissertation.

43

– 24November2023

Shared perspectives on performance as an embodied experience, emphasising the importance of the audience's sensations and involvement. Discussing the idea of how performance documentation, such as videos, captures the essence of live performances. Challenges of representing performance art in an exhibition and the absence of presence in documented works.

The concept of activating elements from a performance, such as objects, during the exhibition is discussed. Mentioning of Laura Fisher's work, particularly a performance involving metal pieces that transform over time and can be activated by the audience. Interested in exploring the concept of recalling performances through memory.

‘For me the performance also disseminates and exists in an afterlife because of the experience that people have, me personally as a performer, but also the people who came and experienced it.’

The responsibility of seeking permission from artists to hypothetically exhibit their work is discussed, Saleh expressing willingness to grant permission. Discussing the possibility of recalling performances through memory and the impact of time on memory. Conversation touches on the idea of creating a 3D model or images to represent the exhibition in the dissertation. Discussions had around how the reader will experience the work through the written dissertation.

Mention of Steve Greer, a lecturer in theatre studies, who works on global majority performance. Discussion of plans to visit Marina Abramovic's exhibition in London and compares it to this project.

44

– 21November2023

The nature of Performance Art: the essence of performance art. Emphasising the importance of the live experience, audience engagement, and the challenge of translating it into documentation. Highlighting the role of documentation in preserving performances, with an emphasis on how it shapes the memory and perception of the audience. It questioned the balance between preserving authenticity and creating a meaningful record.

The importance of considering the audience and their experience. The challenges of engaging different types of audiences, from art enthusiasts to the general public, and how the exhibition settinginfluencesthis.Theconceptofobjectsassociatedwithperformancesasartefacts,raising questions about their significance and the potential to exhibit them separately or alongside other forms of documentation.

What is the context and Intent of documents. Ideas that the context and intent of an artwork influence its display. It’s considered whether certain works are meant to be shown in a specific way or if there's room for reinterpretation and creative exhibition design. Curatorial considerations, contemplating how to showcase works by various artists in a coherent manner while respecting their individual intentions and practices.

‘Trying to read into a work almost like reproduces it, sort of. It becomes something different, maybe when it's exhibited after, its document isn't necessarily the performance’

Thevalueof personal anecdotes and stories related to art, as shared by the artist. Bringing forth the idea that these narratives contribute to a deeper understanding and appreciation of the artwork. The challenges and dilemmas of developing an artistic practice within the academic setting, touching upon the balance between prescribed approaches and personal inclinations.

The role of the audience's perception, the subjective nature of performance art, and the importance of considering the audience experience. Embracing creative exploration, trying different approaches, and not being constrained by preconceived notions of what artistic or curatorial practice should entail. Looking at a primary and secondary audience.

45

When I get asked to make a performance it kind of starts at this point, the practical ideas about what it is and what I want the outcomes to be also this begins the emotional investment, this is a really interesting part because you put so much emotional energy into it. And after days later that can affect you - that you have put so much thought into a project. I just start building up to making a piece. I start thinking about what it could be. Also, I try to bring something new to it.

It’s amazing how it happens and then it’s gone. You can never replicate the experience. So, it is addictive for this aspect. The singular moment. And you have worked on that, so it becomes important to you and that effect it the most. I want to get it right and get something out of it. I always think that I don’t want that ‘flat’ feeling after the performance gone wrong. Of course, I remake lots of pieces. I never say never again. So, everything I have made I am happy to remake. Then it’s always different in a different time. Time has really changed even over the last few years, and this affects everything. It is always changing.

Yeah maybe the performance props are sculptures. I have some I really like; I keep in my studio. The performance pushes me to make sculptures and vice versa. I like when I look at people like Claus Oldenburg and discover he made loads of performances, Franz West is like a performance artist when he sits on those sculptures. He is saying you can be a performance artist in a Franz West artwork. I don’t put value on my performance props, mostly they are just for the performance. I keep them for the next performance.

It depends on the re-performance, if it’s totally staged and made like the original, it’s not really adding to my thinking or exploration. Although it is in a new time and place and that’s interesting. I made a work ‘brushing teeth’ nearly 20 years ago, hiring a woman to brush my teeth for a month. Now I have kids and my life has changed so much since then, so if I remade this one exactly the same it would be totally different. It would be really weird. But I like to change things and try to learn something. That keeps me interested in art - and curious. I’m always looking for a great new work I can add to my set list, that’s funny and odd and surreal and connects.

It really depends on where the work is being shown, or where the performance is happening. I think about this as the starting point and then every decision is based around the context. One

46

of the things I have become really interested in is the context. The gallery is interesting but if you are always showing in a gallery it might get repetitive. I haven’t shown in a gallery for years. Not out of choice. But I have made a series of performances this year and kept busy. If I didn’t force my work out there it wouldn’t get shown anywhere, so it’s kind of `necessity. I make a lot of work for Instagram, just for me and to show work. The opportunities to show works are very limited but a performance practice can kind of upend this by enabling me to make new work all the time if I want. And then sometimes something nice comes also. I’m planning a show of a lot of video documentation, and I don’t know how this will work. I’m not precious about my documentation. I just keep it all and try to make as much documentation as I can.