Autohrs: Barbara Nydegger (atelier verso, b.nydegger@atelierverso.ch), Prof. Elke Menzel (University of Applied Sciences Bern), Dr. Anke Mondschein (FILK Freiberg Institute gGmbH), Dr. Nadim C. Scherrer (University of Applied Sciences Bern), Prof. Dr. Karolina Soppa (University of Applied Sciences Bern)

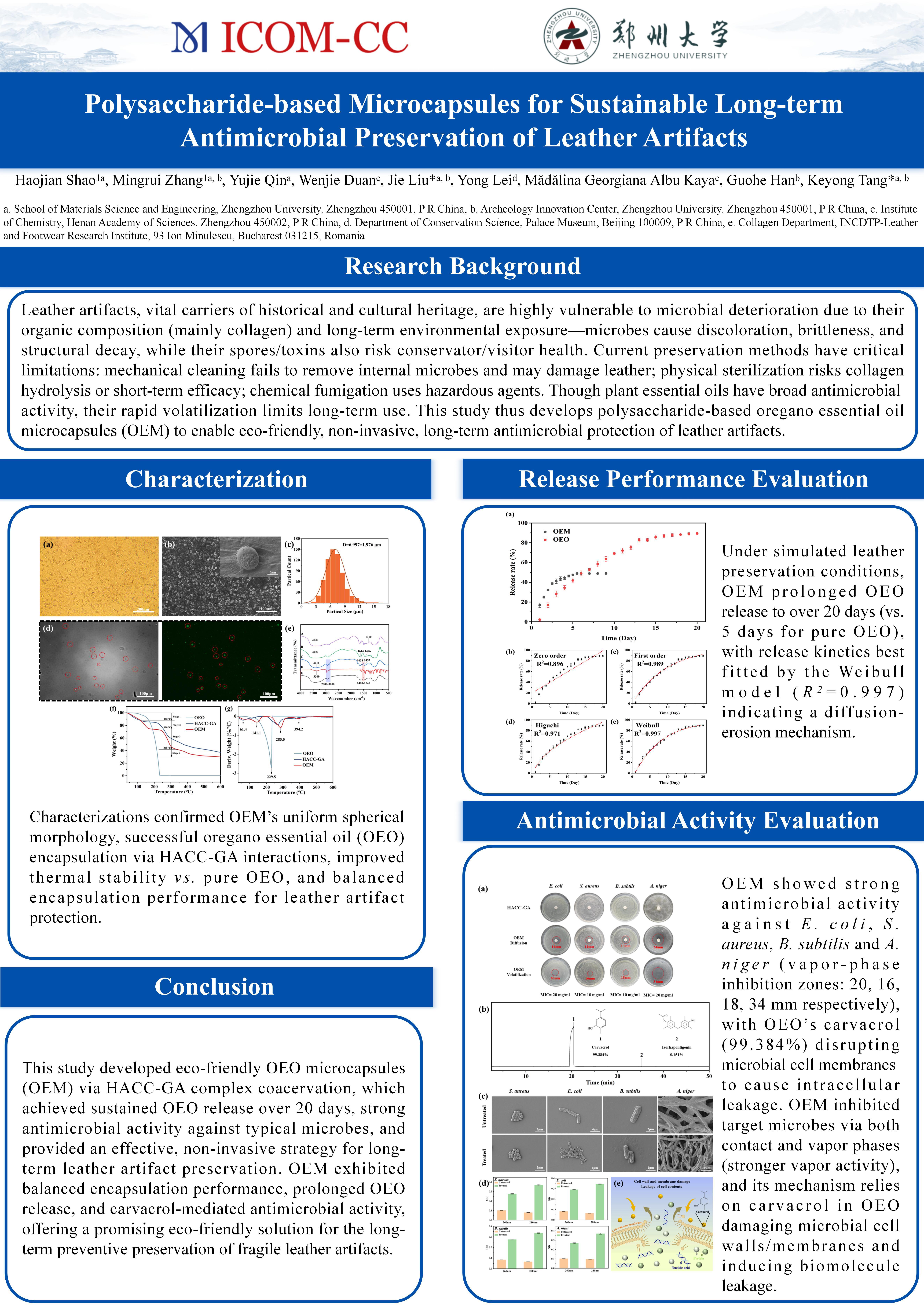

Fig. 1: Problem of the consolidation of powdery leather surfaces: If the consolidant (blue) doesnot fully penetrate the powdery zone consolidation fails and causes a flaky surface.

Introduction

Powdery leather surfaces are a common degradation phenomenon observed with vegetable tanned leathers. In humid environments they tend to discolour and become brittle. The most popular consolidant applied in this context is Klucel® (hydroxypropylcellulose). It is soluble in organic solvents which cause less or no reaction with the leathe compared to water-based solutions. Klucel has been tested on its stabilising effect, ageing behaviour, flexibility and tackiness of the surfaces upon application, and always performed good or very good (Cains, 2005; Kourgierakis, 2013; Mahony, 2014; Müller et al., 2018; Pesch, 2020). Yet studies examining the penetration capability have been missing, though this is fundamental for a sustainable consolidation effect (Fig. 1).

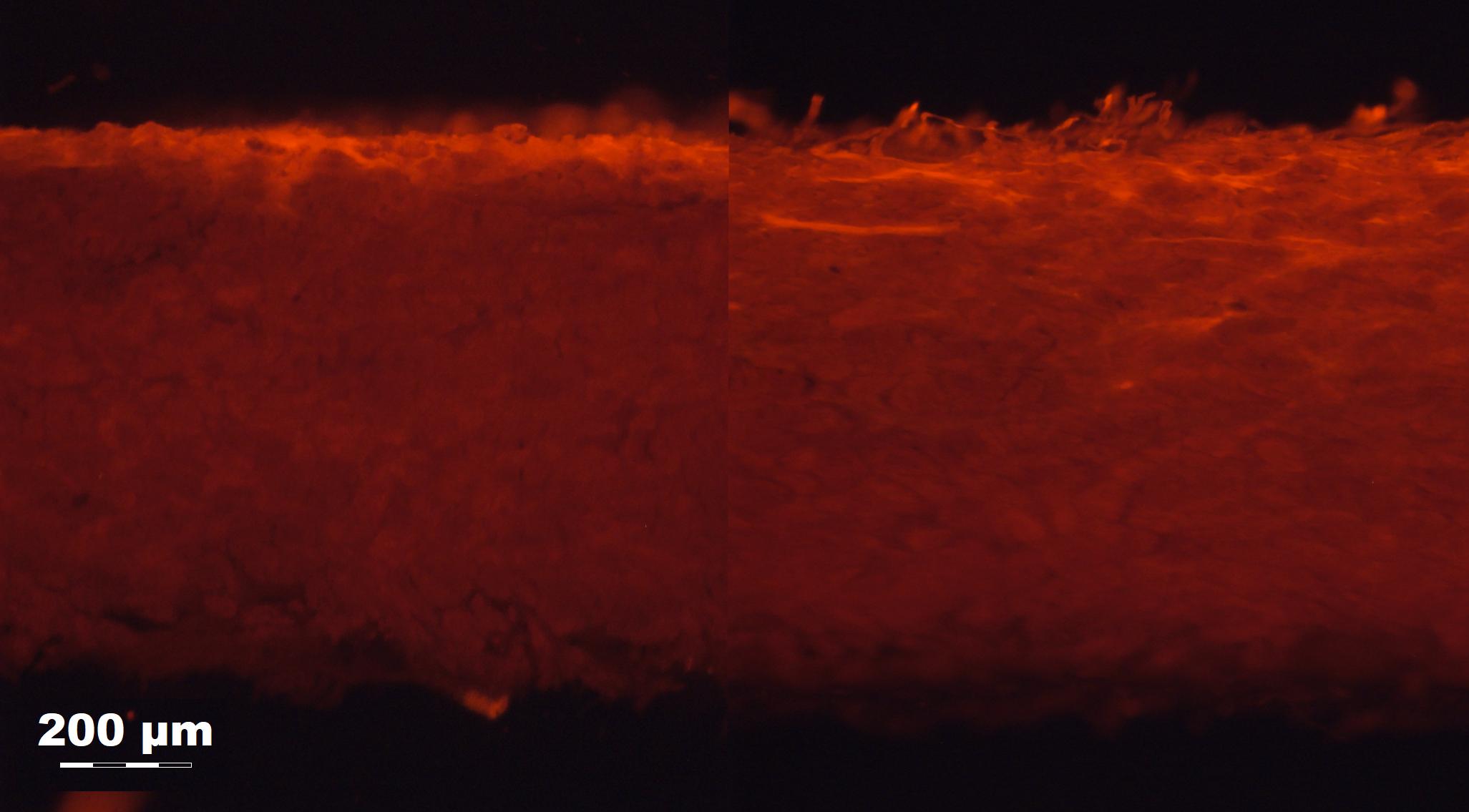

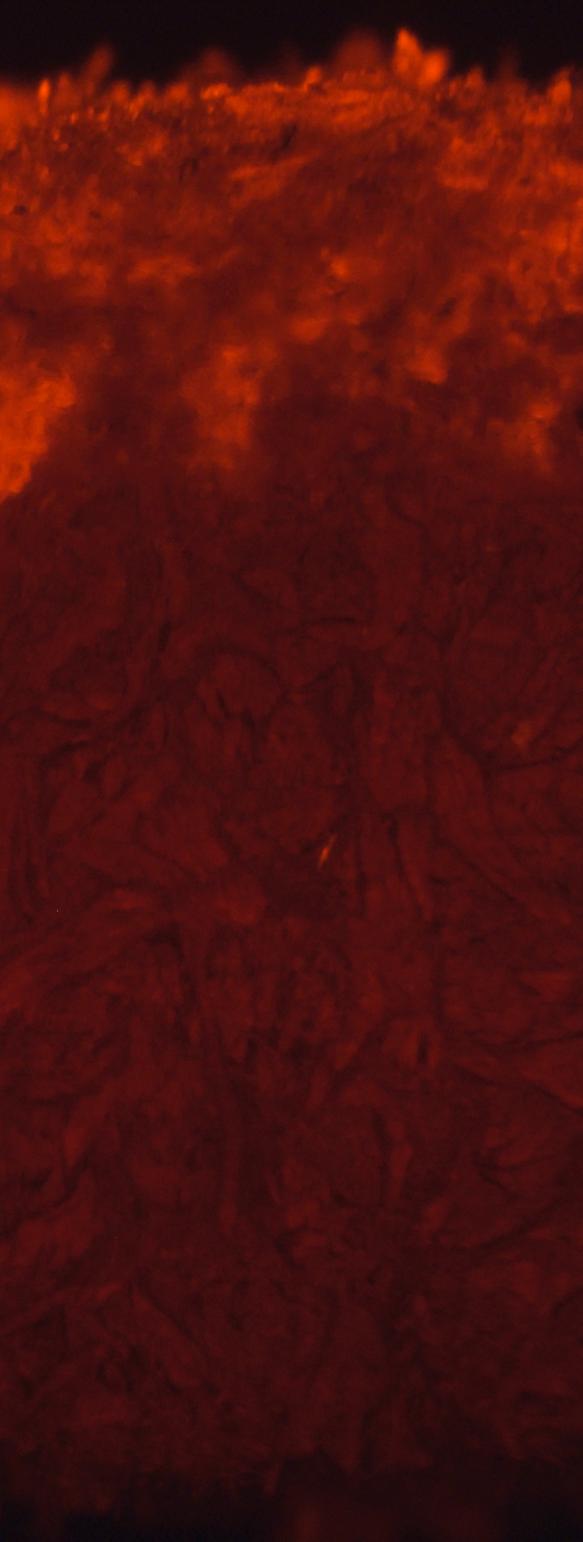

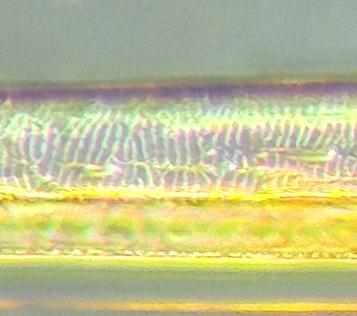

Fig. 2: Comparison of a leather treated with Klucel G 1% in isopropanol (left) and ethyl lactate (right). The solution with ethyl lactate penetrates deeper and spreads better than the one with isopropanol.

Several factors to manipulate the penetration were considered in this study:

- The viscosity of the consolidant was varied by using different degrees of polymerisation (E vs. G) and different concentrations of the glue (0,5%2%).

- Two solvents were compared: The commonly used isopropanol versus ethyl lactate, which is likewise polar and comparable in terms of the octanol-water partition coefficient (IPA: 0,05; EL: 0,06), but differs in the vapor pressure (IPA: 43 hPa (20°C); EL: ca. 2 hPa (20°C)) (Pesch 2020).

- Applications were carried out with a micropipette for reproducibility and with an airbrush, as is the authors chosen method when treating objects.

- One to five applications were compared, with and without time for the substrate to dry inbetween.

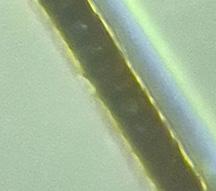

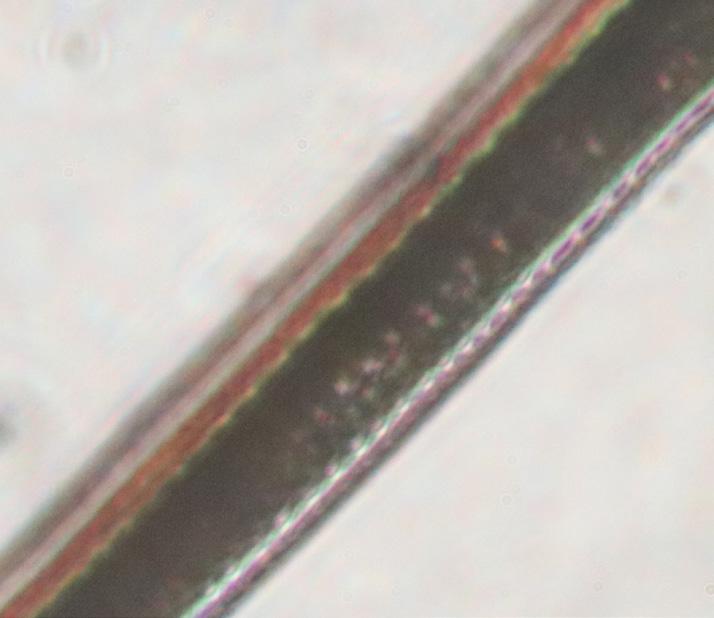

Depth and homogeneity of the consolidant across the penetration zone within the leather were examined by adding 0,01% Rhodamine B to the solution and observing thin sections of the treated leather with a fluorescence microscope (filter: excitation BP 573-613nm; splitter filter LP 510; emission BP 512-542nm) (Soppa 2018)(Figs. 2 & 3).

Further tests examined the stability of the leather after consolidation with sticky tapes (M3) and a brush and wether discolouring is apparent by eye or with a spectrophotometer.

Klucel E 2% in ethyl Lactate 3 applications without drying inbetween

Klucel G 0,5% in ethyl Lactate 3 applications without drying inbetween

Klucel G 1% in ethyl Lactate 3 applications without drying inbetween

Fig. 3: Cross-sections of leather with a thick powdery layer under the fluorescence microscope. On the left, the powdery zone is indicated. The three images on the right show the extend of the consolidant (red fluorescence) in powdery leather sections, treated with different kinds and concentrations of Klucel in ethyl lactate. In this case, only Klucel E 2% reaches the necessary depth of penetration for successful consolidation.

- The lower the viscousity, the deeper the the penetration of the consolidant (Fig. 3). The less viscous, the more stable becomes the treated area.

- The higher the concentration, the more discolouration is observed (Fig.4).

- Concentrations lower than 0,5% Klucel G and 2% Klucel E respectively do not achieve sufficient stabilisation of the leather surface. Concentrations higher than 1% (Klucel G) respectively 5% (Klucel E) can not be applied with an airbrush.

- Solutions with ethyl lactate exhibit better penetration (depth and lateral distribution)than those with isopropanol (Fig. 2). The former also cause less discolouration (Fig. 4).

- Deeper penetration can be achieved with multiple applications as long as the substrate is still absorbing and not dryed.

- With more applications more stability can be achieved, yet more discolouration is observed (Fig. 4).

Within the frame of this study, the following tendencies were observed: If the leather has a thick powdery layer and deep penetration needs to be achieved, 3-5 wet in wet applications of Klucel E 2% in ethyl lactate are recommended,eventhoughlightdarkeningoftheleathermayoccur.Ifthe powdery layer is thin, about 2-3 wet in wet applications of Klucel G 1% in ethyl lactate achieves similar stability with darkening.

Fig. 4: Surface colour changes in differently treated areas: The consolidants Klucel E and Klucel G were applied three (3x) and five (5x) times with an airbrush without drying inbetween. On the very left, pure water (H2O) was applied. It was observed, that the choice of Klucel (E or G) did not affect the intensity of discolouration. Yet the higher the concentration and with every further application, darkening of the leather increased. Pure water caused the worst darkening and showed, how strongly vegetable leather can react to humidity. Ethyl lactate caused less discolouration than isopropanol.

Evaluation of consolidants for the treatment of red rot on vegetable tanned leather: The search for a naturalmaterial alternative. University of California, Los Angeles.

● Müller, J., Pataki-Hundt, A. & Brandt, S. (2018). Festigungsmittel zur Behandlung von abgebautem Leder. Conference: Fachgespräch der Nordrheinwestfälischen-Papierrestauratoren.

● Pesch, K. (2020). Evaluation von Lösemittelnbei der Festigung von abgebautem Leder mit Klucel. CICS – Cologne Institute of Conservation Sciences.

● Soppa, K. (2018). Die Klebung von Malschicht und textilem Bildträger: Untersuchung des Eindringverhaltens von Gelatinen sowie Störleim und Methylcellulose bei der Klebung von loser Malschicht auf isolierter und unisolierter Leinwand mittels vorhergehender Fluoreszenzmarkierung-Terminologie, Grundlagenanalyse und optimierungsansätze. Hornemann Institut HAWK, Hochschule für angewandte Wissenschaft und Kunst.

Anne Lisbeth Schmidt1, Dorte V. Sommer2 , René Larsen 2, Martin N. Mortensen1 , Yvonne Shashoua1, Jane Richter2

1 National Museum of Denmark, I.C. Modewegsvej1, Brede, 2800 Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark

2 Fonden Bevaring Sjælland, Vasebækvej30D, 4600 Køge, Denmark

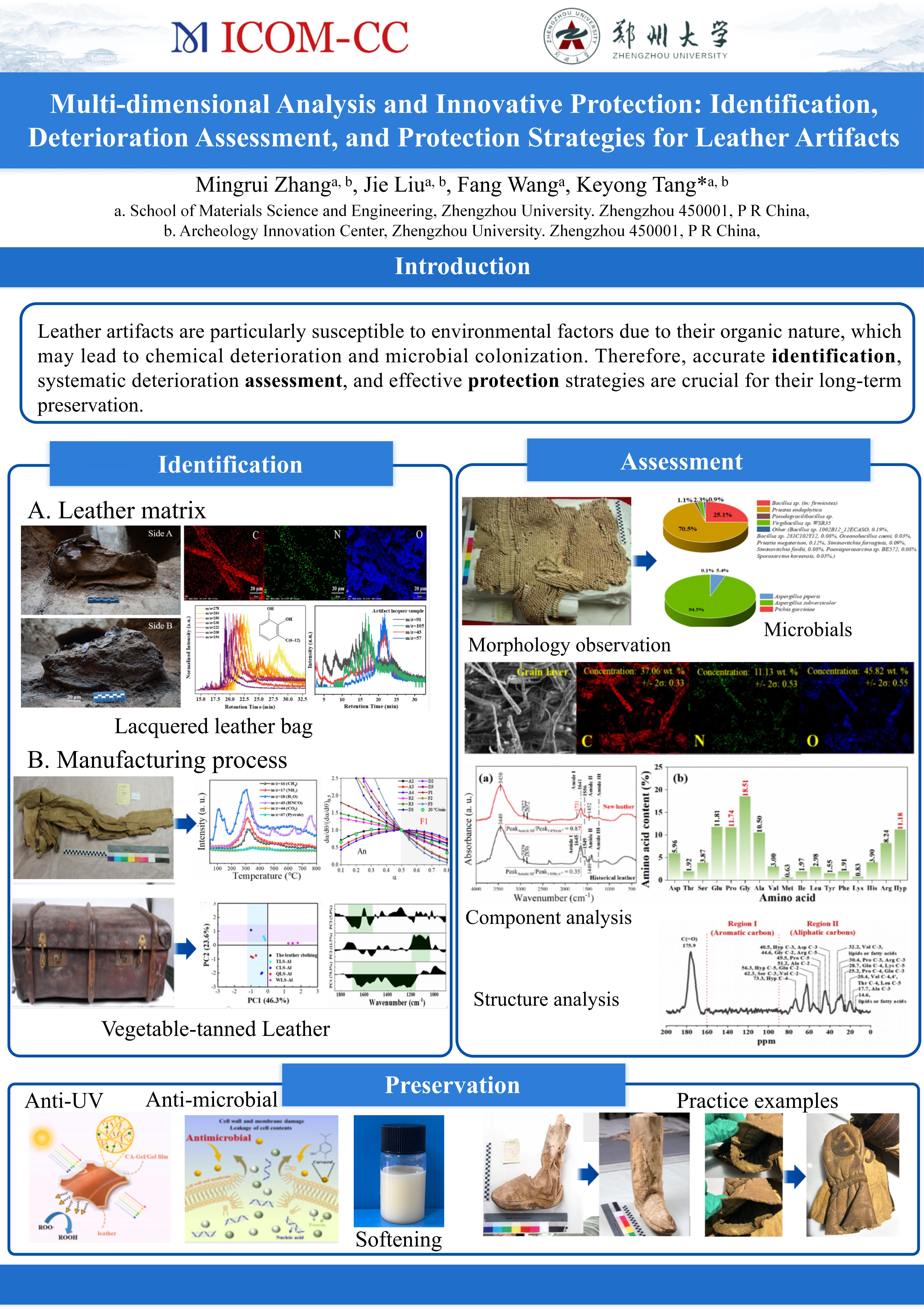

Iron Age fur capes excavated from Jutland bogs in Denmark were analysed using ATR-FTIR, GC-MS, and morphological assessment to identify the original tanning substances and evaluate the degradation of the historical samples.

The four capes, as shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1, were deposited in raised bogs around 2000 years ago, and the influence of the bog environment on fur skin tanning has not previously been recognised. Furthermore, the tanning agents have not been identified before.

and their sites

Denmark, Roberto Fortuna.

Table1. Surveyof analysedfur capes.

Provenance and inventory no.

Sheep 350-41 BC 1879 Asymmetrical inner fur cape Huldremose I, Nimtofte, Djurs Nørre, Randers. C3471

Sheep 365-116 BC 1946 Symmetrical fur cape Borremose I, Aars, Aars, Aalborg. C26450

Baunsø Mose, Roum, Rinds, Viborg. D11103b

Symmetrical fur cape

Cattle 20-220 AD 1927

Sheep 386-203 BC 1883 Fur fragments Vindum Mose, Vindum, Middelsom, Viborg. C5030

ATR-FTIR

Height80

Width 150

Height90

Width 158

Height89 Width 194

Not measurable

Application of ATR-FTIR spectroscopy has previously been successfully used to identify tannins (Falcao et al. 2018, Warming et al. 2018). Several marker bands for vegetable tannins occur within the range of 1731 to 758 cm-1 (Falcao and Araujo 2018, Larsen et al. 2024).

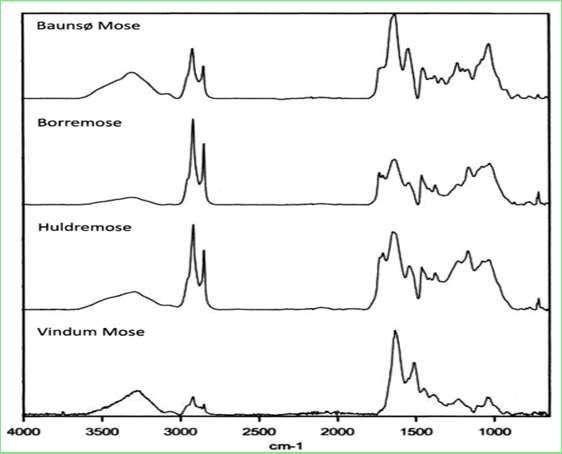

From the spectra shown in Fig. 2, it is evident that the Vindum Mose cape contains no vegetable tannins. Since this cape lacks vegetable tannins, it can be deduced that the bog environment has not modified the initial vegetable tanning process, which was positively confirmed in the three other capes from Baunsø Mose, Borremose and Huldremose I. Moreover,fatty substancesspecificto cattle and sheep have been identified in the respective capes

Figure2. ATR-FTIR absorption spectraof the fourcapes. The analyses are performed in accordance with Larsen et al. 2024.

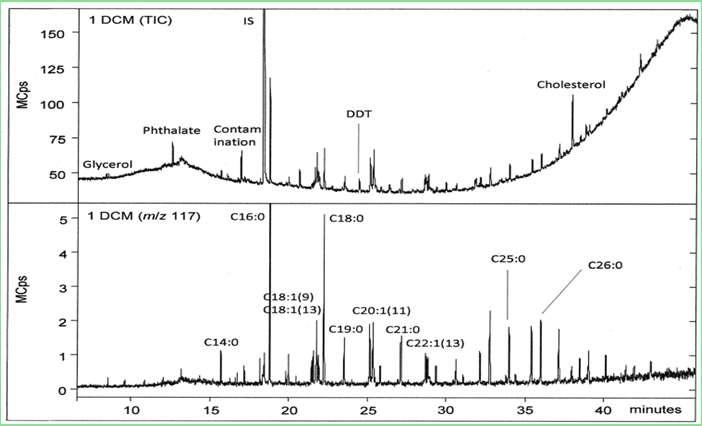

Analysis by GC-MS was aimed at identifying fatty acids as potential tanning compounds. The analytical method followed the protocol outlined in Larsen et al. 2024. The results were inconclusive regarding the likelihood of the capes being fat-tanned. Instead, we obtained information about previous conservation substances, such as pesticides, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure3. Partialchromatogramby GC-MS for dichloromethaneextractof Huldremose I showinga total ion count(top) and a plot of m/z 117 to highlight fattyacids. The analyses are performed in accordance with Larsen et al. 2024.

In the future Iron Age vegetable tanning methods may serve as a viable alternative to modern industrial tanning processes in the future. Given that current tanning techniques are significantly polluting, these ancient methods present a sustainable option for contemporary tanning practices.

References: Falcao, L. and Araujo, M.E.M., 2018. Vegetable tannins used in the manufacture of historic leathers. Molecules 23(5), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051081

Hald, M. 1980. Ancient Danish Textiles from Bogs and Burials. Archaeological –Historical Series Vol XXI: Copenhagen: Publications of the National Museum. Larsen, R., Schmidt, A.L., Mortensen M.N., Shashoua, Y., Sommer, D.V.P. and Richter, J. Iron Age Fur Skin Tanning –a Sustainable Practice? (2024) DANISH JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY, VOL 13, 1-26, https://doi.org/10.7146/dja.v13i1.141323

Warming, R.F., Larsen, R., Sommer D.V.P., Ørsted Brandt, L. and Jensen, X.P., 2020. Shieldsand hide–On the useof hidein Germanicshieldsof the Iron Age and Viking Age. Berichtder Römisch-Germanischen Kommission 97, 155-225. https://doi.org/10.11588/berrgk.2016.0.76641 Object dimensions (cm) Species C14 dating Unearthed Object

by Lu Allington-Jones, The Natural History Museum London (UK)

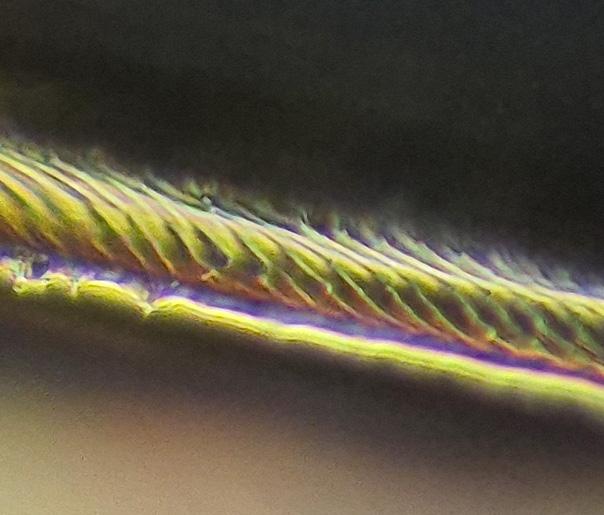

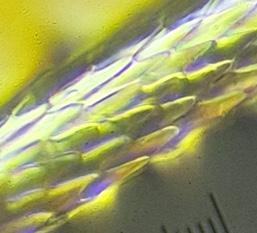

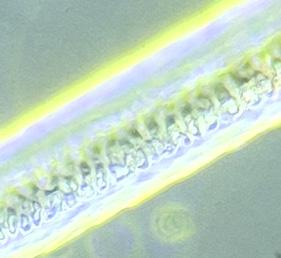

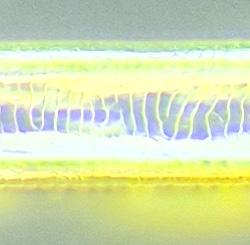

Identifying the animal used to create a piece of clothing, musical instrument or other type of object can be extremely useful when detecting fakes and researching aspects of past cultures such as trade routes. Outlined below are two readily available techniques that can be used to identify animal fur. The overall method uses a normal light microscope and materials which can be easily purchased on the internet, so it is very useful for conservators who do not have access to DNA testing. Once you have made imprints and transparency slides, the images can be compared with published hair catalogues and journal articles. Samples

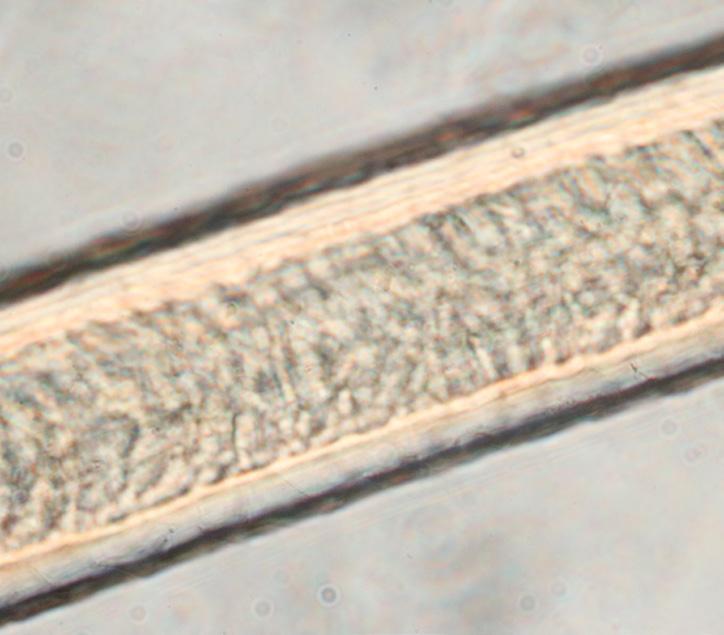

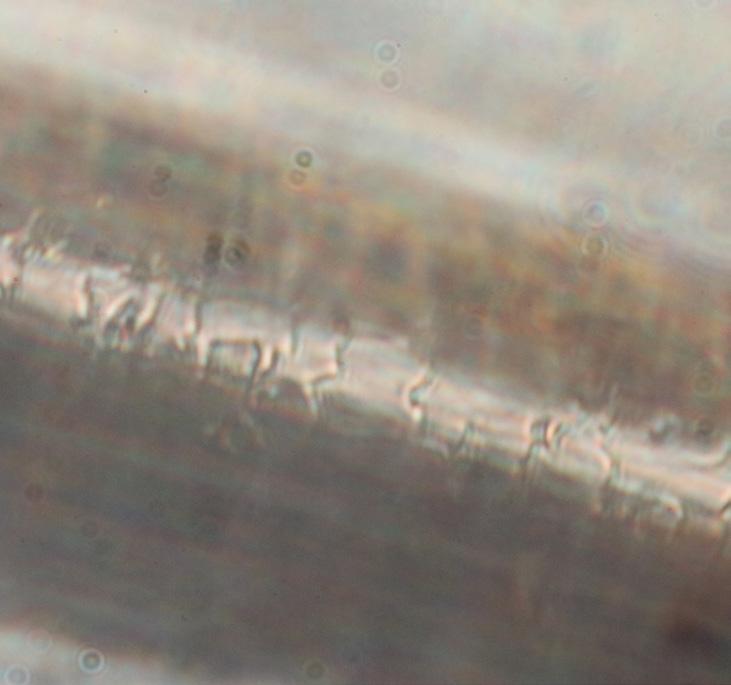

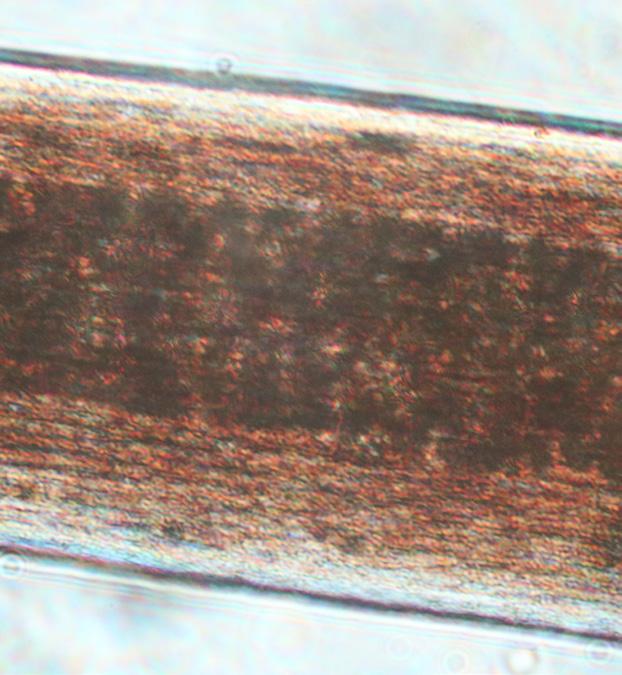

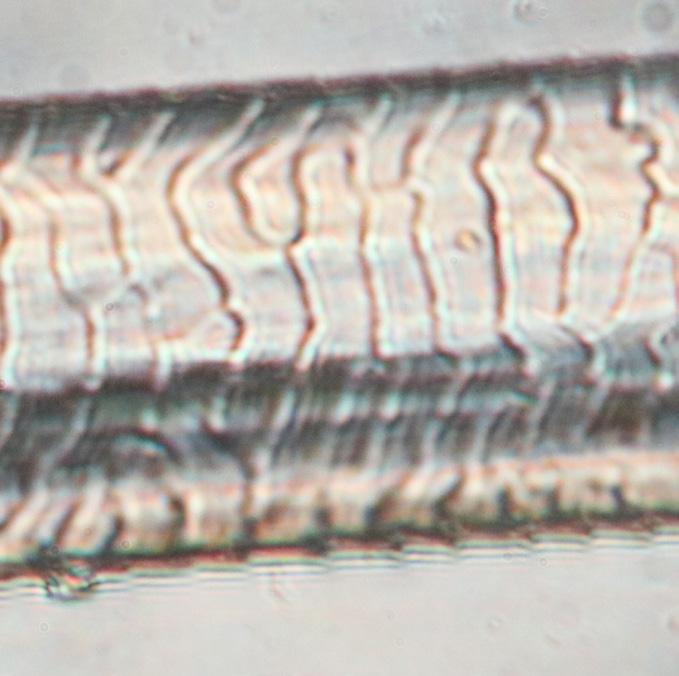

Imprints under magnification

Transparencies

The technique for creating imprints:

1. Dribble a line of UV resin onto your slide and lay one hair on top

2. Place under UV light (available as a kit with the resin) for a couple of minutes or whatever is recommended by the manufacturer

3. Gently peel away the hair using tweezers

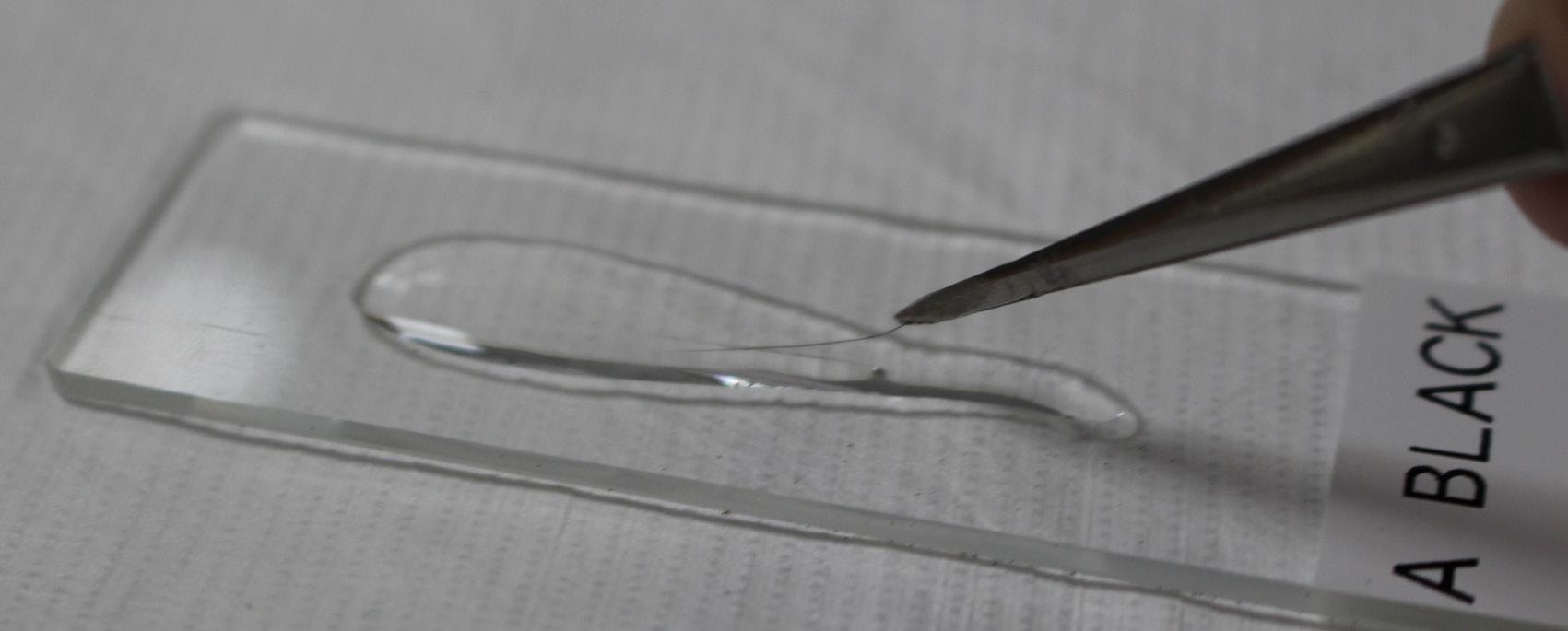

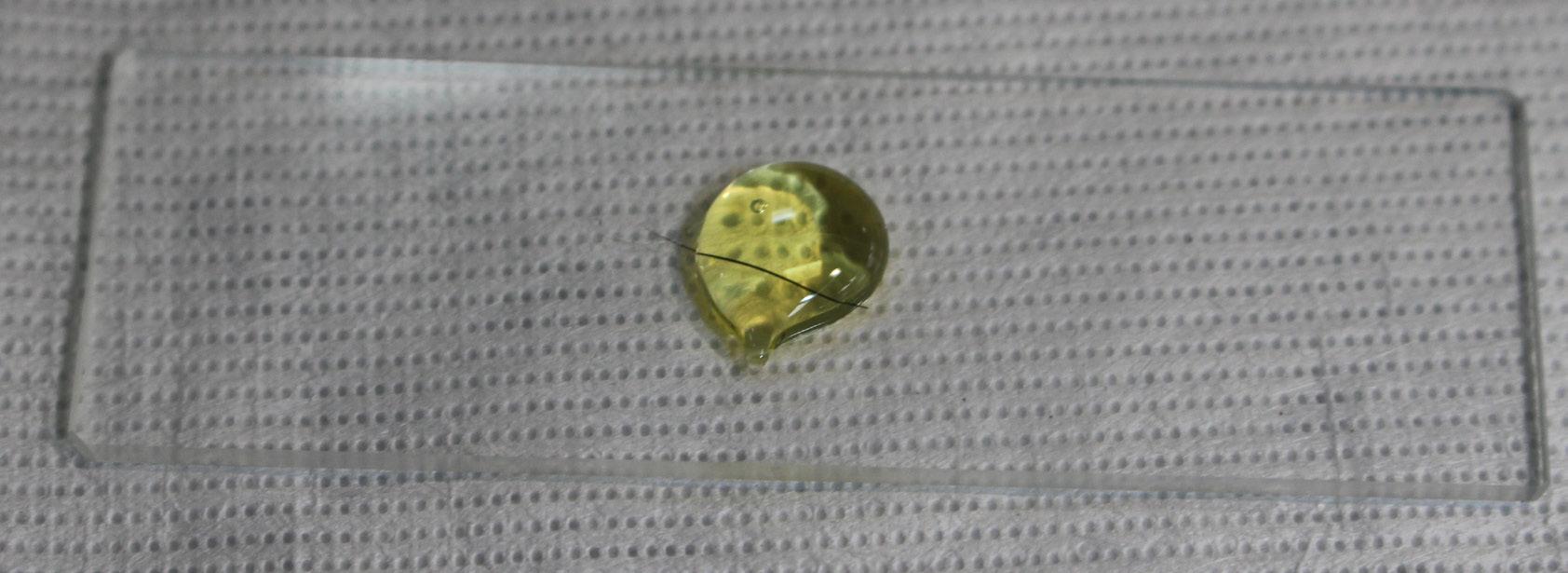

The technique for creating transparent views:

1. Place the hair on a slide and add one drop of Canada balsam on top

2. Drop a coverslip on top of the resin and allow it to settle

3. Place slide onto a hotplate or into an oven at 60oC for a few days then allow to cool. No fiddly hair slicing is required because the refractive index of Canada balsam allows you to see right through the hair.

Note

All images were taken with a mobile phone or a digital SLR camera down a normal polarised light microscope. The samples were all mystery items found in my Mum’s attic.

Conclusion

It is quick, cheap and easy to make the slides but it is impossible to identify what the hairs are from the microscope images alone. It is essential to be able to view the fur object as well.

References

Lee, E., Choi, T.Y., Woo, D., Min, M.S., Sugita, S. and Lee, H. 2014. Species identification key of Korean mammal hair. JVetMedSci . 76(5):667-75. doi: 10.1292/jvms.13-0569.

Tóth, M.2017. Hairandfuratlasofcentraleuropeanmammals . Pars Ltd, Hungary.

More on this technique can be found in the upcoming new edition of Routledge’s Conservationof Leather,SkinandRelatedMaterialsbook.

Arianne Panton ACR

The Leather Conservation Centre Arianne@leatherconservation.org

In 2003 the Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) carried out a survey to understand the range of adhesives used on leather (see Anderson et al, 2003). Since then, several publications have explored the use of specific types of adhesives on leather and skin materials and/or adhesives used for a particular type of treatment – see: Ritchie, 2023 (Lascaux adhesives), Kronthal et al, 2003 (BEVA 371); John, 2000 (general survey of methods and materials including adhesives). However, publications don’t always detail the ‘type’ of leather participants worked with (most of the information pertains to book and paper conservation specifically).

In many collections, the term ‘leather’ is used to describe a number of different skin materials which have undergone different processing methods (oil-tanned, alum-tawed, mineral-tanned). The properties of these materials vary greatly; adhesives commonly used on one material may be highly unsuitable for use on another, thus the information available doesn’t necessarily provide a clear picture of adhesive practices.

The aim was to gather information about the range of adhesives used on vegetable tanned leather specifically, which are most commonly used and whether there is any link between collection type and a preferred adhesives. Participants were also asked to note the main challenges they encounter when using their chosen adhesives.

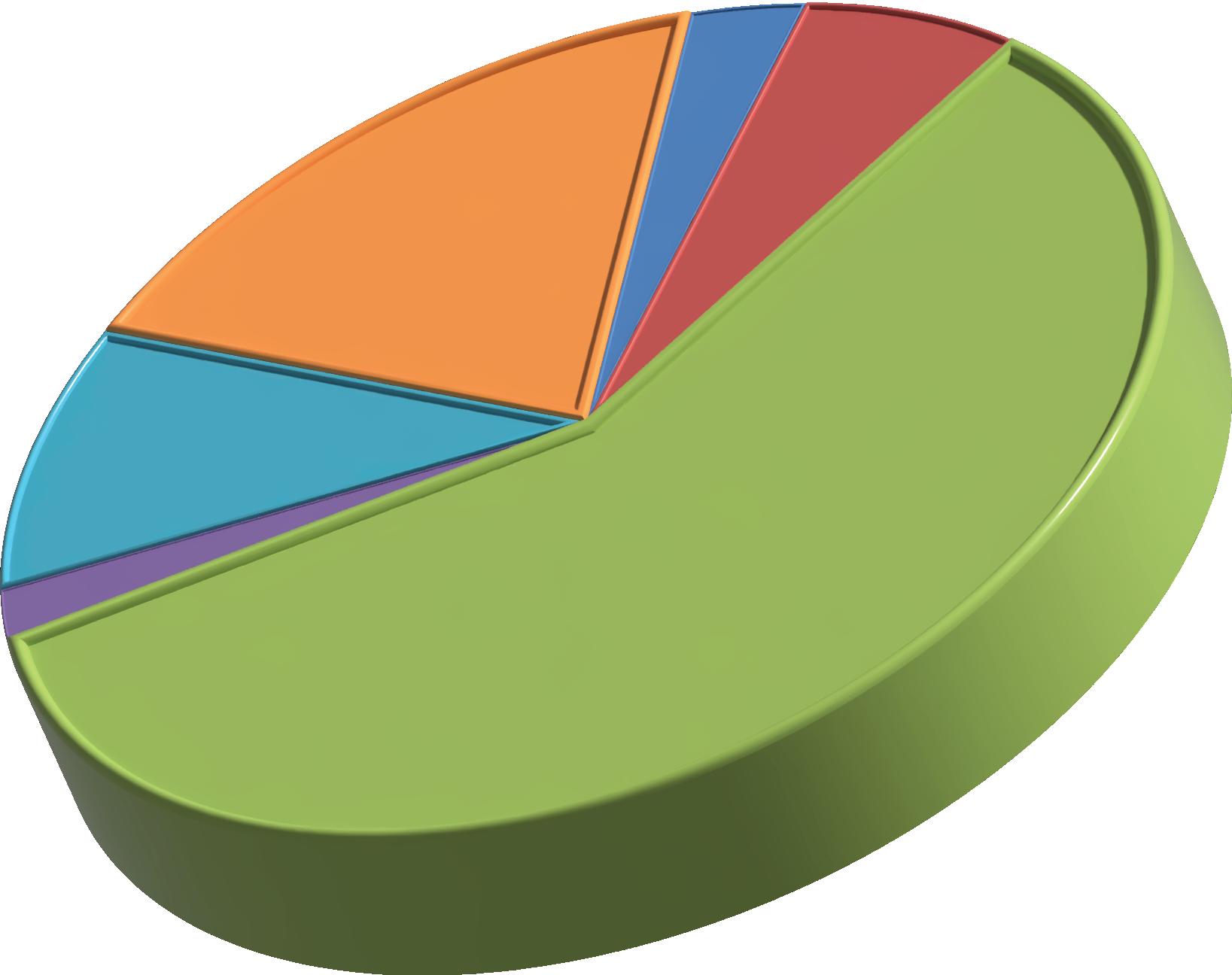

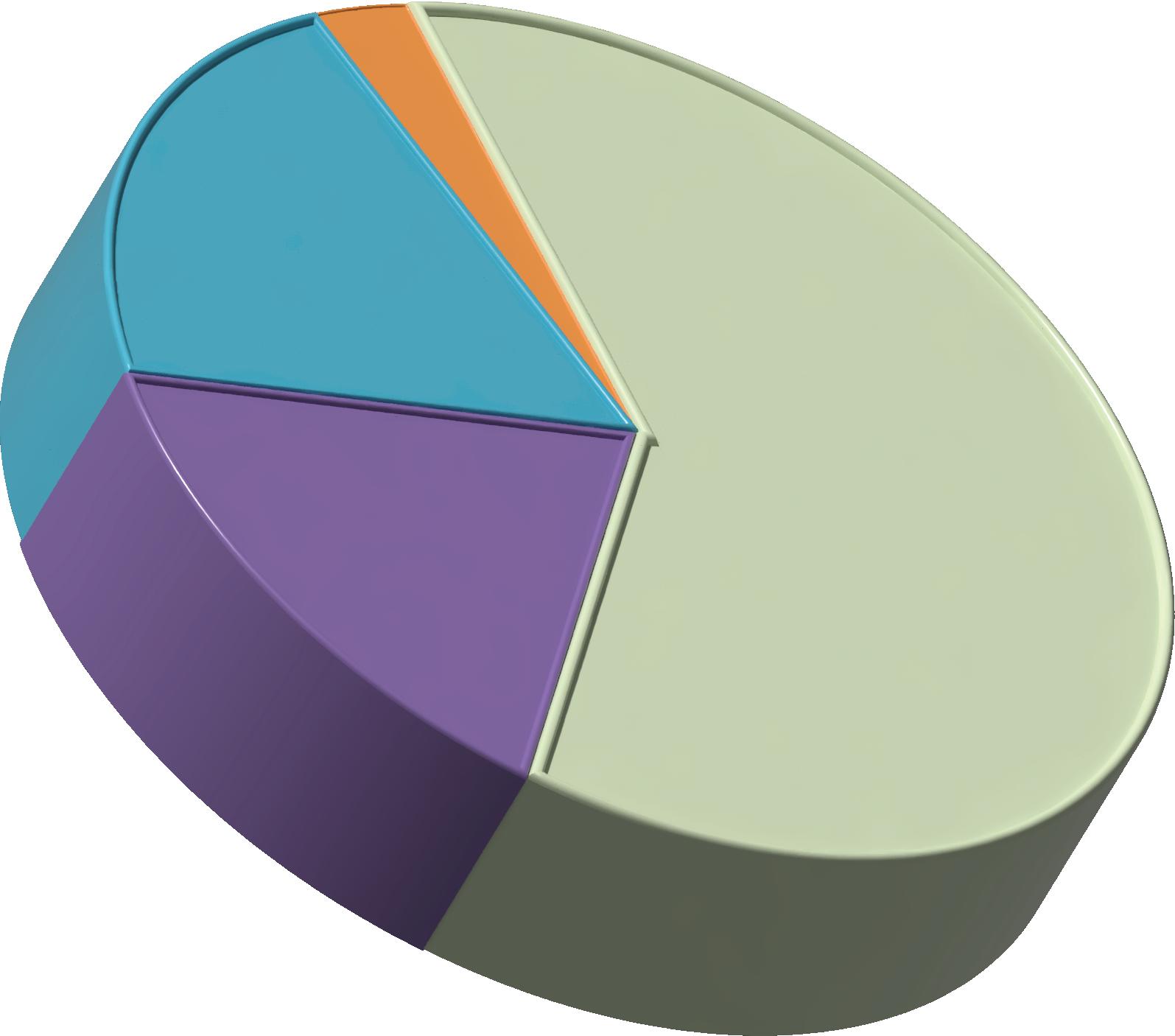

The survey received 61 responses. Of these, 23 people use 4 or more different types of adhesive; 29 people use 2-3 different types, 9 people recorded the use of a single type of adhesive only (7 being wheat starch paste and 2 being a combination of Lascaux 303/498), and 1 respondent doesn’t use any adhesive.

Books

Archaeology World

LASCAUX 303 LASCAUX 498

303/498

WHEAT STARCH PASTE ANIMAL GLUES

HYDROXYPROPYL CELLULOSE

CARBOXYMEYTHL CELLULOSE OTHER

- PVA: 14/19 Specificed Jade 403N

- EVA: 5/12 specified Evacon-R

- HPC: 5/14 specified Klucel G, 1/14 specified Klucel M

- Animal glues: 2/11 specified Hide. 4/11 specifed Gelatine, 2/11 specified Isinglass

- Other adhesives: Rice Starch, Paraloid (type not specified), Beva D-8, Canadian Wheat Flour and Beva Gel

- Other combinations of adhesives used include EVA/Lascaux and EVA/Wheat Starch Paste

4 References 5

- There was a clear preference for wheat starch paste despite noted drawbacks including darkening, lack of flexibility of dried film, and bio-receptivity. Wheat starch paste is a long-time favorite of book and paper conservator (33/37 respondents from this category regularly use it), which is demonstrated in the results.

- Lascaux combinations are also a popular choice. Respondents like the flexibility of the dried film and ability to modify adhesive properties to specific requirements. Concerns were noted about the reversibility of Lascaux and weakness of the bond formed when reactivated with heat.

- PVA is used by nearly a third of respondents (with most specifying Jade 403 as their preferred brand), however it was noted to be overly strong in some situations, and concerns were raised over darkening and re-treatability.

- Klucel G is rarely used as an adhesive, a major drawback being its low tack and weak bond formation when used as an adhesive.

- Beva 371 film is used by one fifth of respondents however a common complaint by users is poor response to the recommended activation temperature. This issue has been raised in other specialism following several reformulations and was the topic of focus in the Getty/BEVA 371 Project. A new formulation, BEVA 371 Akron, may offer a solution to this in the future (Getty, n.d.).

- Direct wet application is the most common application method by far. Challenges of heat reactivation were listed as limited access and poor condition of the leather. Mist application is only used by 4 respondents and a main drawback noted as lack of control regarding quantity of adhesive applied.

‘I think that there is enough diversity in properties across the range that there is usually a good match. Lascaux 498 has good aging properties and heat reversibility is a bonus but can be difficult to work with due to lack of initial tack, and I personally don't feel that mixing with 303 makes up for this. PVA has great working properties but poor reversibility/ reputation for stability. BEVA is a fav in terms of working properties but cannot be used in many circumstances because of access.’ ANON

‘Lascaux - dries as a plastic film, concerns about reversibility/retreatability Wheat starch paste - high moisture content causes risk of damaging degraded leather Klucel-M - it is a very weak adhesive, too weak for most applications’ ANON

- Kristen, J. (2000). Survey of Current Methods and Materials Used for the Conservation of Leather Bookbinding. The Book and Paper Group Annual. 19, 131-140.

- Kronthal, Lisa & Levinson, Judith & Dignard, Carole & Chao, Esther & Down, Jane. (2003). Beva 371 and Its Use as an Adhesive for Skin and Leather Repairs: Background and a Review of Treatments. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. 42(2). 341.

- Ritchie, F., & Palumbo, B. (2022). Lascaux Adhesives in Objects Conservation: Three Practical Case Studies on Leather, Skin, and Entomological Specimens. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, 62(3), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/01971360.2022.2093538

- Anderson, P., Primanis, O., Puglia, A., & Raphael, T. (2003) Use of Adhesives on Leather Discussion. The Book and Paper Group Annual, 22, 99-104

- Getty (n.d.) Scientists and Conservators Reinvent Formula for Vital art Conservation Materials [online]. Available at: https://www.getty.edu/news/scientists-and-conservators-reinvent-formula-for-vital-art-conservation-material/