INTERWOVEN ENERGIES

‘Resonating with the Spirit of Country’

MARC6000 I Thesis Studio 530347509 I Disha Neyanira Ramesh

‘Resonating with the Spirit of Country’

MARC6000 I Thesis Studio 530347509 I Disha Neyanira Ramesh

Thesis Studio MARC6000 LIMINAL NEXUS

Disha Neyanira Ramesh

THESIS PORTFOLIO submitted in partial fulfilment of the award course requirements of the Master of Architecture

Thesis Studio Supervisor: Catherine Donnelley

Thesis Studio Coordinator: Deborah Barnstone

November 11, 2024

The University of Sydney, Faculty of Architecture, Design & Planning

At the core, truth’s wisdom glows, Radiating light that flows, Through all creation, far and wide, In every layer, it’s true inside.

Oneness at its heart, it binds, Connecting all in unseen lines. As this energy within us swirls, Together forward, the world unfurls.

01. Acknowledgement

02. Abstract / Thesis Statement

03. Introduction Country, Culture and Spirituality

04. Deep Listening

4.1 Custodianship and Country

4.2 Country as Living Entity

4.3 Walking on Country: Jigamy Farm

05. Reflection

5.1 Form: Designing with Nature

5.2 Material: Earth and Spirit

5.3 Precedent Studies

06. Interaction/ Design Proposals

6.1 Masterplan of Jigamy Farm

6.2 Extension of existing Office Space

6.3 Sacred Narratives in Space

6.4 Circles of Connection

6.5 Welcome to Country - Visitor Center

6.6 Collaborative: Community Engagement

07. Conclusion Reflections on Cultural Continuity

08. References

I write this thesis as a non-indigenous person, and I acknowledge the privilege and responsibility of conducting this thesis on the Country. I recognize the profound significance of the land, sky, and waterways of Jigamy Farm Yuin Country, and I express my deepest respect to the Traditional Custodians, the people of the Yuin and Monaro nations. I honour their enduring connection to the land and pay tribute to all the elders —past, present, and future—whose wisdom and administration continue to sustain these landscapes cultural, spiritual, and ecological integrity.

I acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which I undertake my studies and extend my respect to the ancestors of the Country I come from, whose energies continue to sustain and guide me. I am grateful for the opportunity to listen deeply, reflect, and engage with the knowledge shared with me. Special thanks are extended to Alison, Uncle Elvis and all the community members for generously sharing their stories and insights, which have greatly enriched this research and my understanding of Country.

“We say Country is the spirit that surrounds you, the earth beneath you, the air you breathe, the food you eat. If you’re looking after the spirit of Country, then you’re looking after yourself.”

- Uncle Max Dulumunmun Harrison, Yuin Elder

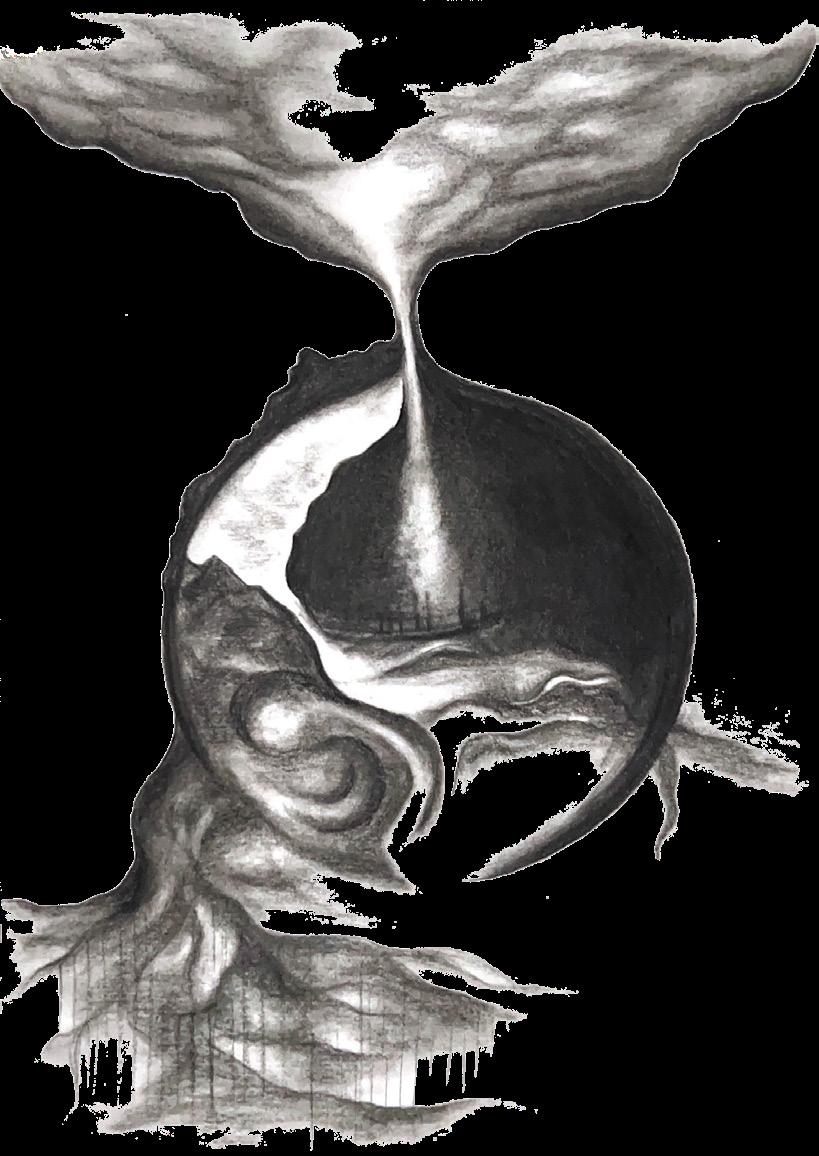

The spirit of Country, for First Nations peoples, embodies a profound connection where land, people, and all living entities are intertwined in a sacred, enduring relationship. Country is not merely a physical space; it is a sentient being that holds ancestral wisdom, identity, and memory, shaping the cultural and spiritual lives of those who care for it. In a world where natural environments are increasingly under threat, the need to honor and protect this relationship is essential.

Guided by this understanding, this project envisions architecture as a living extension of the Yuin community’s spiritual, cultural, and ecological bond with their ancestral Country. Using locally sourced rammed earth, the structure honors the materiality and life cycles of the land, transforming built spaces into tactile narratives of its history, sacred sites, and Dreaming stories. By fostering sensory immersion through the interplay of wind, water, native flora, and natural soundscapes, the design transcends to create a holistic space for healing, storytelling, and cultural continuity. Rooted in the principles of deep listening and oneness consciousness, it invites visitors to experience the land as a sentient, nurturing entity, bridging traditional Aboriginal knowledge with sustainable, community-driven design practices. Therefore, it becomes an act of truth-telling and reconciliation, where architecture serves as a medium for uniting people, land, and culture in a transformative dialogue of healing and shared custodianship.

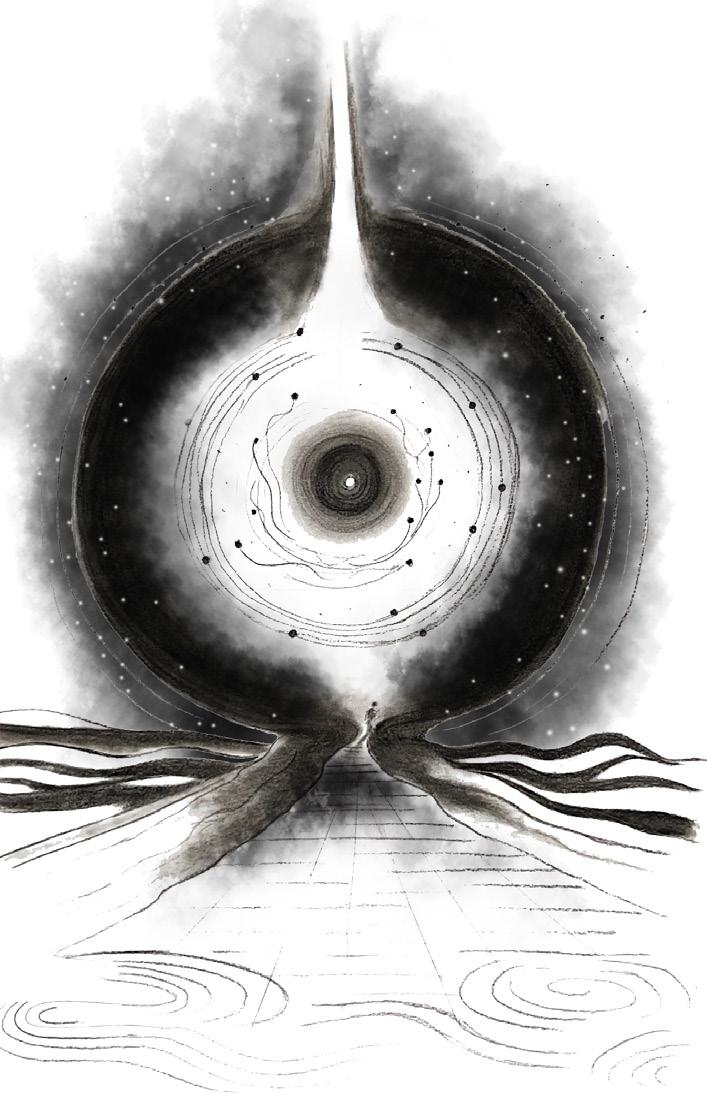

The Dreaming and the creation of the Country represent a multi-dimensional interrelationship where there is no separation between nature and people, and no hierarchical distinctions exist. At the core of all things lies the wisdom of truth, radiating its energy throughout creation. This energy, which embodies truth, flows through all beings and entities, connecting them through layers of interrelations. At its essence is the consciousness of oneness. By allowing this energy to flow within and among us, we can move forward together in unity. As expressed in the Uluru Statement from the Heart (2017: Uluru, N.T.)¹, healing should begin with truth-telling and walking the land guided by ancestral wisdom. It is rooted in the principles of Oneness Consciousness², where it is conceived to reflect the intrinsic unity of humanity, nature, culture, and the cosmic universe.

For First Nations peoples, the connection to the Country is far more than a physical association; it is an intrinsic spiritual, historical, and cultural bond that weaves deeply into their identity, and knowledge systems. Country is not only land but also encompasses water, air, plants, animals, and all living beings. This profound connection is central to their identity, informing the stories, songs, and ceremonies passed down through generations, which are instrumental in maintaining a continuity of culture and knowledge.

The bond with Country is central to fostering a strong sense of belonging and identity among First Nations people. This relationship is often described as interdependent, with the health of the land intimately connected to the well-being of the people. The connection to culture encompasses the preservation, expression, and active practice of Aboriginal cultural heritage. Maintaining this vibrant relationship with culture is vital, as it strengthens identity, enhances resilience, and offers meaningful opportunities to engage with ancestral traditions and histories³.

1 The Uluru Statement. 2017. “Uluru Statement from the Heart.” The Uluru Statement. May 26, 2017. https://ulurustatement. org/the-statement/view-the-statement/.

2 Campbell, Greg. Total Reset. Imprint: Greg Campbell. Greg Campbell Consultancy Pty Ltd trading as Total Reset, March 1, 2022.

3 Dudgeon, Pat, Helen Milroy, and Roz Walker, eds. Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. Canberra: Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2014.

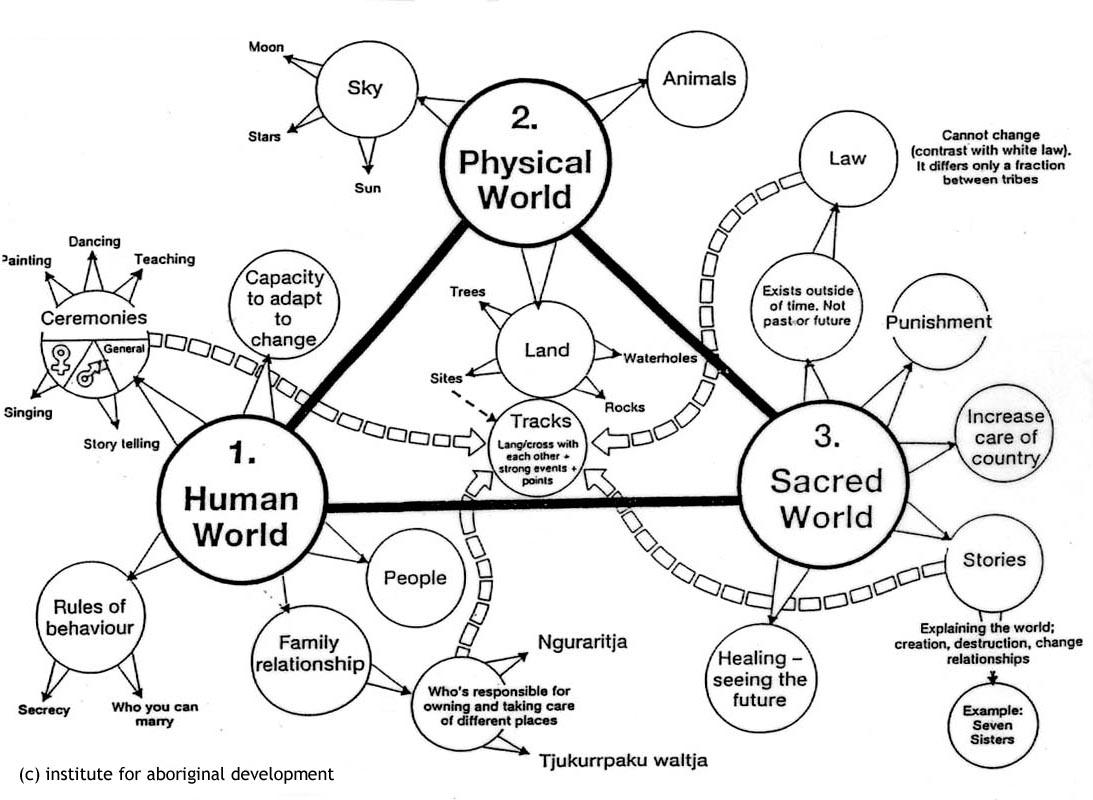

Spirituality within Aboriginal cultures is a multilayered complex concept that bridges the past, present, and future 4. It encompasses a deep connection with all life forces, including relationships with people, living beings (such as animals), and non-living elements (such as tides and natural phenomena). Spirituality is often expressed through various forms of art including songs, storytelling, ceremonies, and the Dreaming—a foundational belief in which ancestral spirits are understood to have shaped the world³. Consequently, Country and spirituality are inter-linked, forming a core aspect of identity for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Throughout history, spirituality has often been dismissed as a myth rather than acknowledged as a system grounded in deeply held truths. Colonization and Westernization largely misunderstood and disrupted Aboriginal spiritual frameworks, undermining Indigenous practices and connections to the Country. Today, however, Aboriginal spirituality is experiencing a resurgence as Indigenous communities reclaim their traditions and reassert their ties to ancestral lands. This revival is bolstered by growing recognition of Indigenous land rights, and cultural heritage, and the support of educational and cultural initiatives that share Indigenous knowledge with wider audiences. The resurgence of Aboriginal spirituality highlights Indigenous culture’s resilience and affirms spirituality’s enduring role as a source of strength, identity, and healing within these communities 5 .

Although the meanings and significance of Country, culture, and spirituality can vary between communities, shaped by age, geographic location, and specific cultural knowledge, they consistently play an essential role in fostering mental, emotional, and physical health⁶. Across diverse Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, this relationship serves not only as a source of spiritual nourishment but also as a foundation for resilience, community cohesion, and healing, offering a connection to ancestors and a responsibility to future generations.

4 Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017-2023. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2017.

5 Grieves, Victoria. Aboriginal Spirituality: Aboriginal Philosophy, the Basis of Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, 2009.

6 Poroch, N., Arabena, K., Tongs, J., Larkin, S., Fisher, J., and Henderson, G. Spirituality and Aboriginal People’s Social and Emotional Wellbeing: A Review. Darwin: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, 2009.

Fig 02 Dreamtime Chart Source: Aboriginalart.com.au

Custodianship is a central concept for Aboriginal communities, grounded in the care and respect for Country. Unlike Western notions of land ownership or exploitation, Aboriginal custodianship emphasizes an enduring responsibility to protect, nurture, and sustain both the land and its ecosystems. Country is not merely a physical landscape; it is viewed as a living, sacred entity, rich with ancestral knowledge, cultural history, and spiritual significance—factors essential to the community’s cultural continuity and collective wellbeing. The well-being of the community is inseparably to the well-being of Country, reflecting a profound interdependence 7 .

For Aboriginal people, Country extends far beyond ‘territory’, mapped boundaries of roads, topography, or vegetation. It encompasses sacred sites, Dreamtime stories, songlines, and an intricate understanding of ecosystems that has been passed down through generations. Aboriginal people see themselves as part of the land’s natural cycles and hold responsibilities to care for it for future generations. Practices like traditional burning, seasonal harvesting, and deep listening to Country sustain ecological balance and biodiversity.

Staying connected and living with the Country requires recognizing it as more than its physical attributes. As Auntie Miriam Rose Ungunmerr expresses, “It is inner, deep listening and quiet, still awareness, the land talks” is an invitation to engage in profound listening, respecting the knowledge, stories, and cultural practices of those who have stewarded the land for tens of thousands of years⁸. It is a concept and spiritual practice that is dadirri (dadid-ee), from the Ngan’gikurunggurr and Ngen’giwumirri languages of the Aboriginal peoples of the Daly River region. Hence, this connection surpasses viewing land as a mere property, emphasizing an enduring, holistic relationship that honours the land as a sentient and sustaining entity for the well-being of all.

7 Rose, Deborah Bird. “Nourishing Terrains: Australian Aboriginal Views of Landscape and Wilderness”. Australian Heritage Commission, 1996.

8 “DADIRRI by Dr Miriam Rose Ungunmerr.” YouTube. Foundation for Indigenous Sustainable Health, 2022.

4.2 Country as Living Entity: Understanding the Spirit of Place

Spirit of life, within us and the Spirit of nature resonates through vibration². It is rooted in what Indigenous Australians call “First Law” or “Natural Law,” which reflects a cosmic harmony, where every being and element of nature is interconnected through vibrations and energy. It is significant to understand what land is, a living spirit for Aboriginal Australians, it is not simply a physical location but a deeply spiritual and sentient force that is intimately connected to their identity and way of life. In “Some Thoughts about the Philosophical Underpinnings of Aboriginal Worldviews,” Mary Graham emphasizes that the Country holds sacredness through its inherent energy and wisdom, which influences the culture, spirituality, and physical survival of the people⁹.

The land is seen as a living spirit sustained through Dreamtime stories, songs, dances, and artworks, each form of expression embedding and preserving essential knowledge of place and spirit. Engaging with these expressions—by listening and interpreting them carefully—provides insight into the spirit of the land itself. The land communicates through nature signs, such as changes in animals, plants, and weather patterns, reflecting a profound spiritual interconnection between people and their environment. Over thousands of years, Elders have embedded knowledge in art forms to ensure that teachings about social structure, culture, and ecological laws endure.

For instance, Dreamtime stories convey more than narrative; they encode ecological knowledge and cultural laws, guiding the community in how to live harmoniously with nature. Similarly, songlines traverse the land, mapping geographical and sacred sites while reinforcing relationships with Country and with Creation Ancestors. In Aboriginal worldview, these ancestors shaped the landscape, created life, and established cultural laws during the Creation Era. Their travels across the land are inscribed in songlines, providing both a literal and spiritual map that teaches people about their origins and responsibilities to Country 10

2 Campbell, Greg. Total Reset. Imprint: Greg Campbell. Greg Campbell Consultancy Pty Ltd trading as Total Reset, March 1, 2022.

9 Graham, Mary. “Some Thoughts about the Philosophical Underpinnings of Aboriginal Worldviews”. Oxford University Press, 2016.

10 Wroth, David. “Why Songlines Are Important in Aboriginal Art.” Japingka Gallery, 2015.

04

Country

“We create this song, dance, and art to be and remember a place or feel it without being there, to remember” - Aboriginal Elder

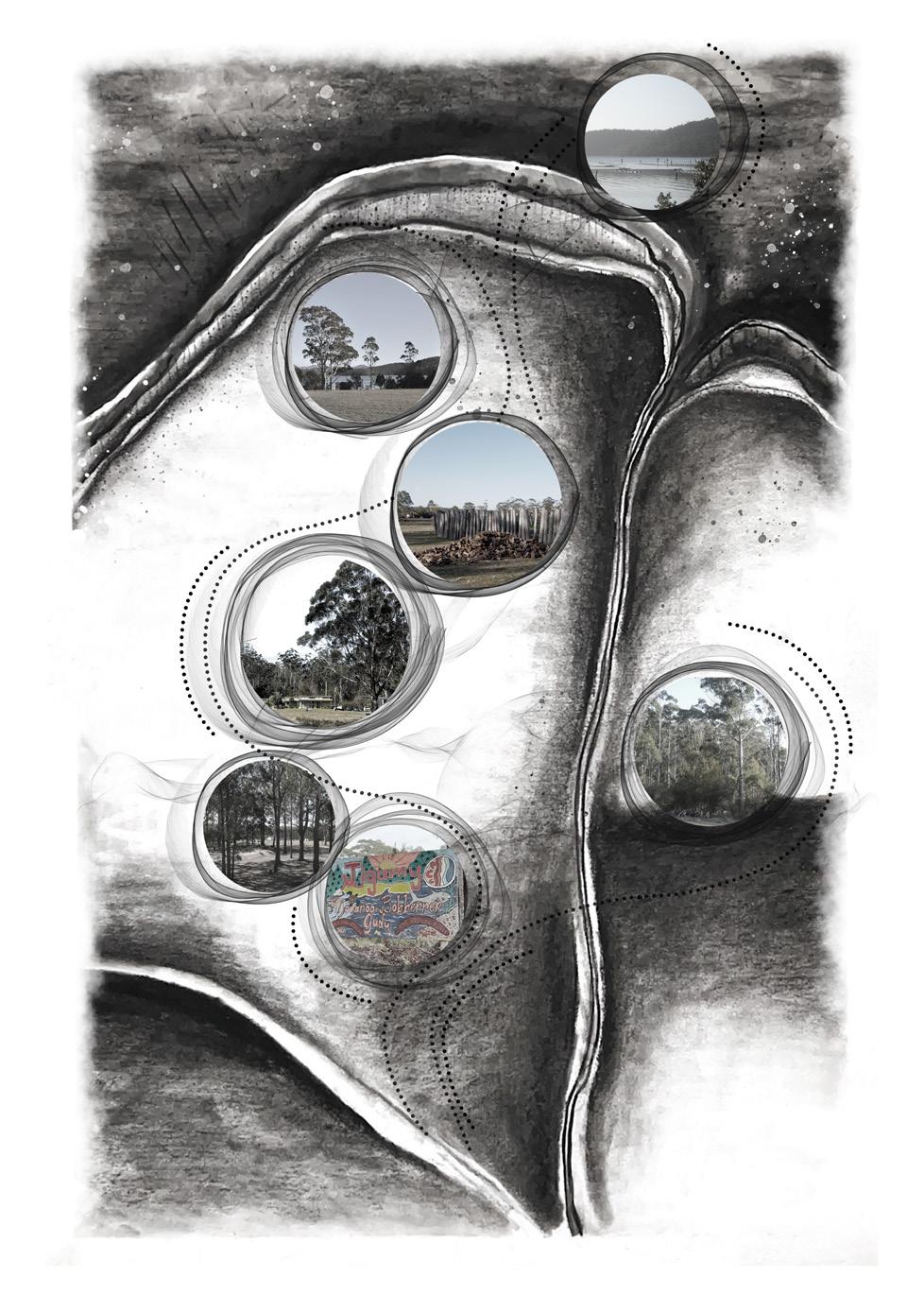

4.3 Walking on Country: Jigamy Farm

Jigamy Farm, a Country known for the basket grass is marked as a gateway to the long historical trail route from the mountains to the sea called the Bundian way 11 . It is located on the edge of the Pambula Lake, north of Eden, NSW, and is looked after by the Twofold Aboriginal Corporation. Established in the late 1960s by the Bega Aboriginal Advancement Association, it became a reality through the determination of Uncle Ossie Cruse, whose tireless efforts helped secure this land for the Youth Group and the broader Aboriginal community 12

The location of Jigamy Farm was, and remains, a place of high cultural significance to the local Aboriginal community. Jigamy Farm is a sacred place with rich cultural heritage, history and is now prominent meeting place for local First Nations people and those that are visitors. The farm is home to sites of cultural heritage, including 3,000-year-old middens, a carved shield tree, and the beginning pathway to a notable songline. These middens, containing shell accumulations primarily of oyster and mussel shells, are remnants of shellfish gathered and consumed by Aboriginal people 13. Each soil layer, rich with shells, charcoal, and ash, narrates its own historical story.

Situated at the farm’s entrance is the cultural center known as Wanneroo Wilber Agadoo, meaning “peoples of the mountain and seas,” which serves as the gateway to the Bundian Way. Uncle Ossie’s mission for Jigamy Farm is to convey the Indigenous lifestyle before colonization and educate visitors on the complex ecological knowledge embedded within Country. The farm is home for the Art and Culture events, one such event is Giiyong (GuyYoong) meaning ‘come to welcome’ in the south coast language spoken by the local elders 14. It is also home to an art studio, camping ground and ceremonial ground. Jigamy Farm is a powerful place that is important to the local First Nations people, as it has become a safe place for them to heal, connect, strengthen their cultural identity, and continue their cultural practices as their old people have done since time immemorial 12

11 “Discover Jigamy - the Gateway to the Bundian Way, Eden.” 2023. Bundianway.com.au. 2023.

12 Clapham, K., et al. 2024. “Wellbeing, Space and Society.” Wellbeing, Space and Society 6. Accessed 2024.

13 Sullivan, M. E., and P. J. Hughes. 2020. “The Stuarts Point Shell Midden Complex: An Assessment of its Nature, Extent and Significance.”

14 “Giiyong Festival.” 2024. Giiyong.com.au. Accessed 2024.

First visit to the Jigamy Farm, I was greeted by the tender embrace of Mother Earth, her calm presence enfolding me as I stepped onto the farm. The soft murmur of water mingled with the rustling of leaves, as if whispering secrets from ages past. As I walked on the Country, I felt like I was hugged between the Sky Country and the Land Country. The light shimmered upon the water’s surface, while the breeze swept gracefully, breathing life into every corner, making this place feel like something sacred, something truly extraordinary.

On the macro level,

Jigamy farm is part of the Yuin nation and Bega Valley. For the Yuin community, the land and water are not merely a physical entity but is embodied with spiritual significance and cultural identity. The Sapphire Coast is situated within an ancient landscape, under the shadow of three mountains - Biamanga (Mumbulla), Gulaga (Mt. Dromedary) and Balawan (Mt. Imlay). These three mountains are of deep significance to the Yuin people and their descendants. They are used today for ceremony and teaching 15 .

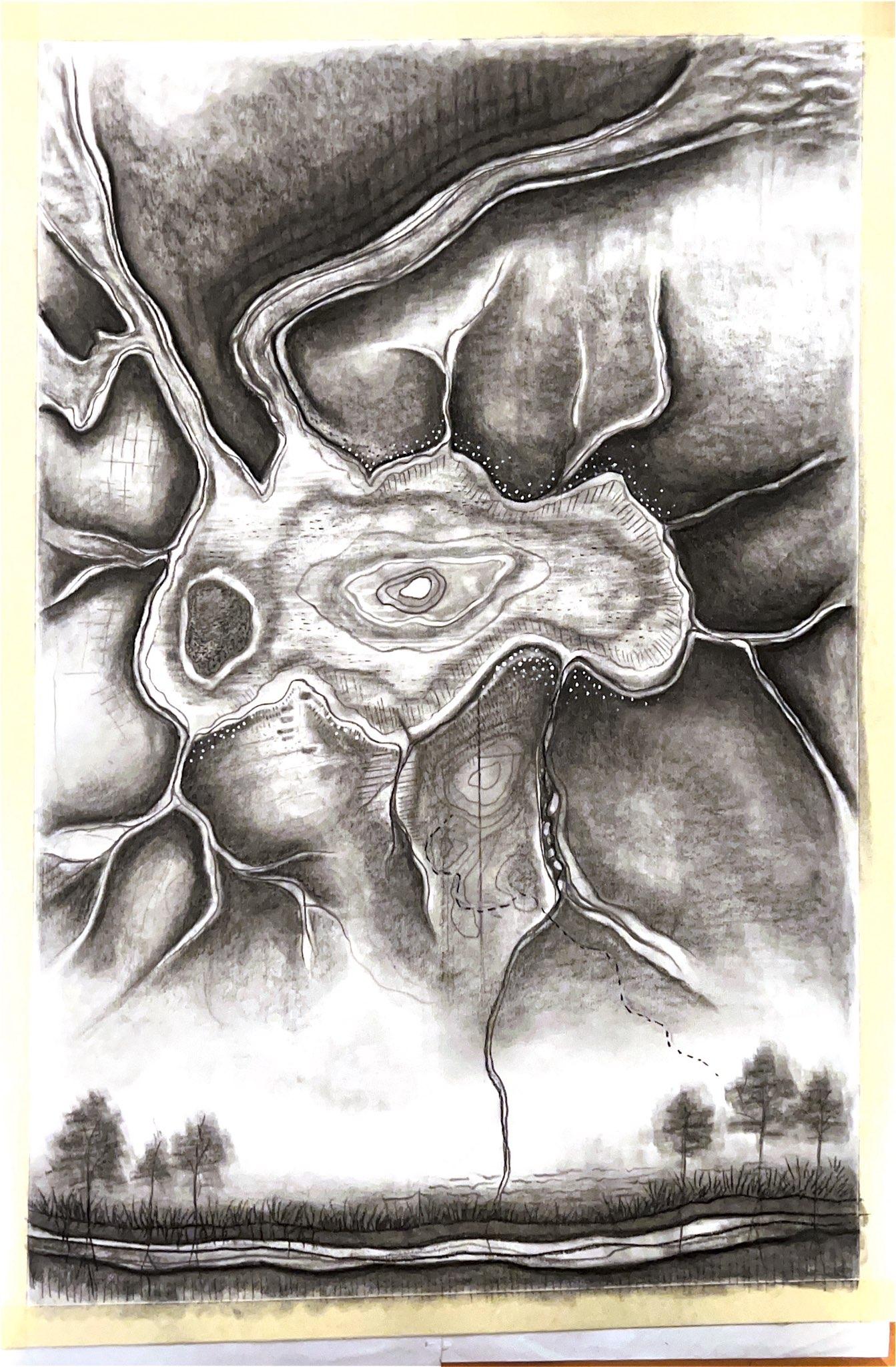

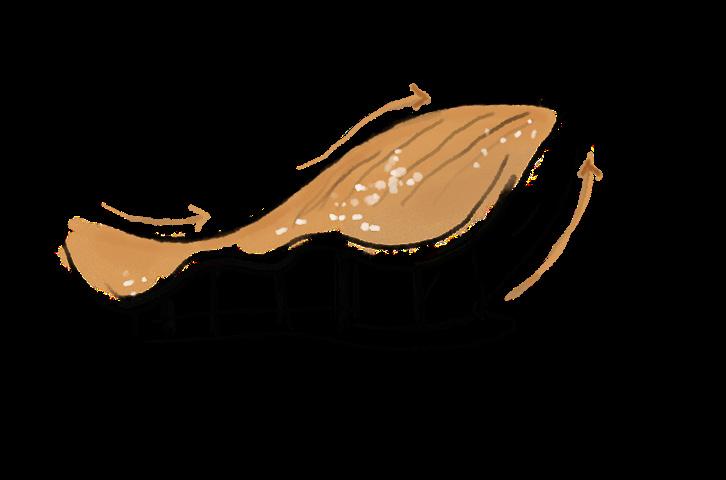

The significant water body, Pambula Lake, located near Jigamy Farm, holds a significant place in the Yuin cosmology. The lake and surrounding areas of shrub forest, riparian vegetation, swamp forest, salt marsh, all are considered sacred, and they are linked to Dreaming stories, which are essential to the Yuin people’s understanding of their world, history, and identity. These stories passed down through generations, connect the people to the land and their ancestors, ensuring the continuation of cultural practices and knowledge. The middens along the site, buried under the soil are the trails left by the activities of the ancestors from thousands of years. The layers of shell, charcoal and ash, each layer of the soil has a story to tell. The killer whale story, the Fire Ceremony and Bogon moth Ceremony 16 hold significance in the Yuin Nation and represent the symbiotic relationship between the country and its people 17. The nurturing essence of the Country is embodied in the natural energies that flow through it. The wind, carrying the sound of water across the land, the gentle rustling of leaves, the songs of birds, and the footsteps of people all contribute to the unique and profound significance of this place. It is this symbiotic relationship that makes the place truly special, as it nurtures not only the environment but the people who engage with it.

15 “Sapphire Coast Aboriginal Cultural Experiences.” 2024. SapphireCoast.com.au. https://www.sapphirecoast.com.au/ aboriginal-cultural-experiences.

16 Stephenson et al., 2020. 2000 year-old Bogon Moth (Agrotis infusa) Aboriginal food remains, Australia. Nat. Res. 10, 22151.

17 Clapham, K., et al. 2024. “Wellbeing, Space and Society.” Wellbeing, Space and Society 6. Accessed 2024. https://www. sciencedirect.com/journal/wellbeing-space-and-society.

5.1 Form

“When we ask nature, first we quiet our human cleverness. Then we ask, and then we listen. The answer is the echo that bounces off the land herself. With the solution in hand, we always end the circle by saying thank you.” - Janine Benyus,

Founder of Biomimicry Institute

Long before the modern world realized the concept of Biomimicry, humans have been practicing this “empathetic interconnected understanding of how life works and ultimately where we fit in” all around the world 18.

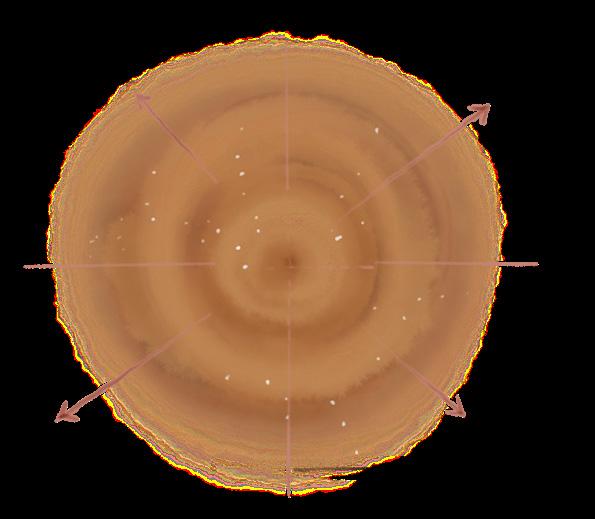

The design concept seeks to achieve harmony with nature by integrating Indigenous knowledge and natural laws. It draws upon principles of biomimicry, examining complex natural forms, dynamic ecological systems, and adaptive solutions to inspire sustainable and intelligent design approaches.

18 “Biomimicry Explained: Quieting Our Human Cleverness.” 2024. Anima Mundi Herbals Blog.https://animamundiherbals. com/blogs/blog/biomimicry-explained-quieting-our-humancleverness.

Air

As the wind sweeps across the ocean’s surface, waves ascend, sculpting shifting mountains that seem to defy gravity itself.

09

Water

The first wave surges forth, setting the dance in motion—a symphony of movement, unveiling forms that inspire, flowing in endless rhythm.

The ocean’s waves touch the soul, stirring a profound sense of wonder and awe.

11

5.2 Material

Earth and Spirit: The Materiality of Rammed Earth in Architecture

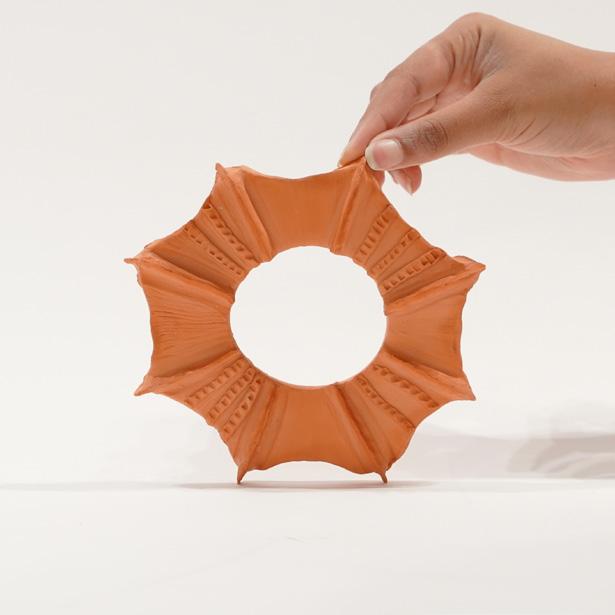

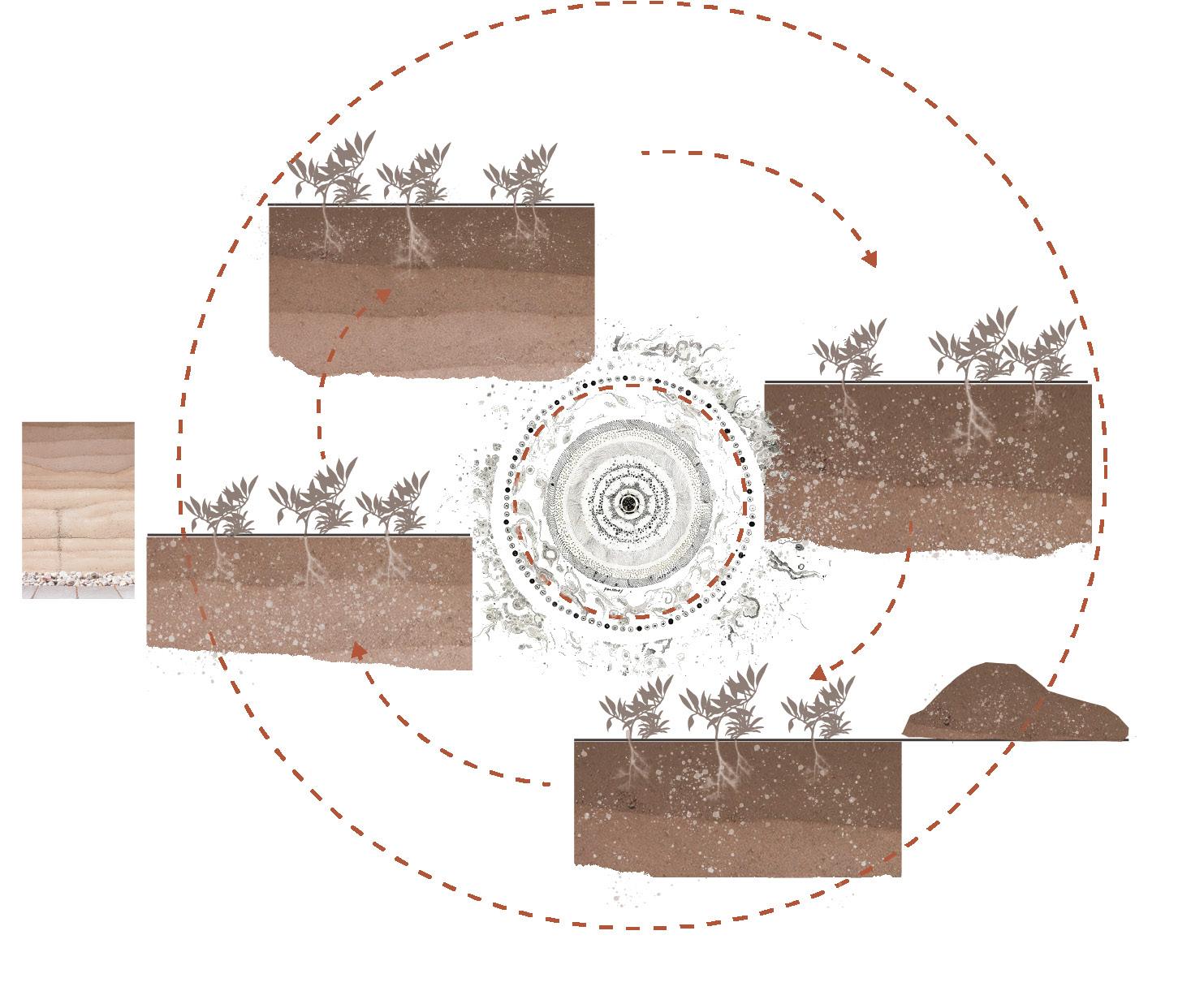

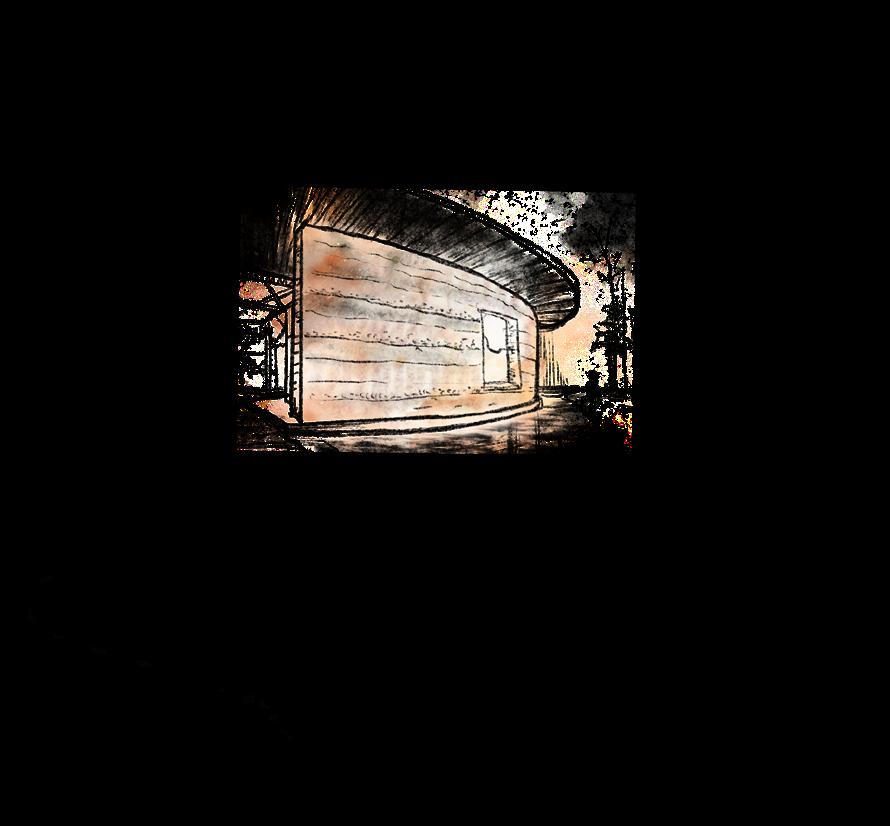

The materiality of this project centres on the use of locally sourced rammed earth, a material that connects the structure directly to the soil and the life cycle of the land. Rammed earth, celebrated for its sustainability and connection to place, is not only a building material but a medium for storytelling. The earth used in the construction is drawn from the local environment, reflecting the colours, textures, and history of the land itself.

Rammed earth has served as a construction material for thousands of years, commonly used in regions with moderate temperatures and humidity. The soil at the farm, rich in sand, silt, and clay, is particularly suitable for rammed earth construction. By incorporating insulation and water-resistant materials, its durability can be further enhanced. In designated construction areas, formwork for the walls will be built using wooden planks, which are recyclable and reusable. For curved walls, customized formwork will be employed using the same technique.

Utilizing soil from the land requires a respectful approach to this resource, as the extraction of topsoil for construction impacts the local ecosystem and land health. Thus, careful consideration of the soil life cycle is essential. This cycle plays a crucial role in ecological balance, supporting plant growth and carbon sequestration, which aids in climate change mitigation. Soil is a dynamic system of organic and inorganic components, housing a complex network of microorganisms, insects, and fungi that drive nutrient cycling and carbon storage 19. Through decomposition and respiration, these organisms break down the organic matter, releasing some carbon dioxide (CO₂) back into the atmosphere, while a portion of carbon remains stabilized in the soil as humus or other organic matter, a process known as carbon sequestration 20

19 Lehmann, Johannes, and Markus Kleber. “The Contentious Nature of Soil Organic Matter.” Nature 528, no. 7580 (2015): 60-68. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16069.

20 Lal, Rattan. “Soil Carbon Sequestration Impacts on Global Climate Change and Food Security.” Science 304, no. 5677 (2004): https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1097396.

To maintain soil health during ground extraction, it is essential to consider the soil’s natural cycle of use. With the help of farm’s existing carbon sequestration practices, the continuous process of carbon-rich soil can be sustained. After the topsoil—rich in carbon—is extracted for construction, these practices can be extended to deeper layers, allowing for continued carbon sequestration in the underlying soil. This approach not only supports the soil's regenerative cycle but also encourages plant roots to access deeper soil layers, enhancing long-term carbon storage.

Clay Bricks - Possibility of 3D printing to customised forms using biodegradable materials

Wall - Possibility of curved wall of locally made mud bricks

Clay Dome - Possibility of constructing dome and organic forms

Locally Sourced Materials

Uluru Kata Tjuta National Park Cultural Center

Gregory Burgess Architects I 1995 Aboriginal people of Anangu Country

“This building is for all of us Our beautiful Cultural Centre has Kuniya, the woma python woman, built within its shape Her body is made of mud and the roof is her spine” - Traditional Owner 21

The Cultural Centre is built with locally made mud bricks crafted into a free-form structure 21

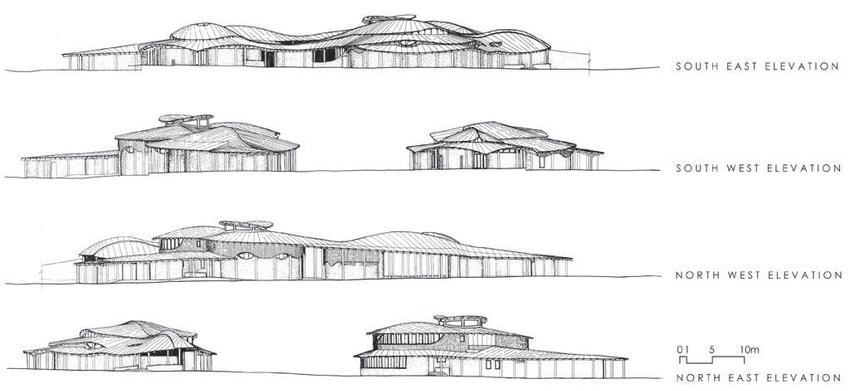

The Anangu Aboriginal community, deeply connected to the desert landscape and dunes surrounding Uluru, draws upon locally available materials and cultural features for their architectural expression. The design of their center reflects traditional Anangu values through modern construction techniques, blending cultural identity with contemporary forms. Inspired by the significance of Tjukurpa—an interwoven network of stories, laws, and ancestral acts that link people, land, plants, and animals— the design evokes the dynamic experience of walking Anangu Country. This landscape is known through repeated walking and storytelling, creating a sense of place that resonates through memory and rhythm rather than singular, fixed views 22

The center’s two serpentine buildings emerged from earlier symmetrical forms, embodying fluid and shifting rhythms. The building’s contours—floor, walls, and roof—swell and contract, generating a sense of motion, energy, and continuity with the surrounding landscape. Movement through the space changes in pace and density, as the structure alternates between openness and enclosure. This choreography of space creates an experience of presence and absence, guiding visitors through an Anangu interpretation of Uluru’s landscape. The roof, crafted from bloodwood and copper shingles, blends into the view, grounding the building within its sacred setting 22 .

21 “Cultural Centre Building.” 2017. Parksaustralia.gov.au. 2017. https://parksaustralia.gov.au/uluru/do/cultural-centre/ building/.

22 “Liru and Kuniya.” n.d. ArchitectureAU. https://architectureau. com/articles/liru-and-kuniya/.

Vanuatu School

Kaunitz Yeung | 2012

Vanuatu School is a community lead and directed project with the partnership of the Ministry of Education in Vanuatu. It is a hybrid classroom which is built with the local knowledge and skills by the community.

The structure is built as a hybrid of concrete and locally sourced timber that is cyclone and earthquake resistant as the site is prone to these natural calamities. The timber structures can be easily replaced when damaged, as the material is locally available, and the local labourers are equipped with the required skill set to work with these materials. Thus, forming a cycle of construction, deconstruction and reconstruction with the design environment 23 .

By utilizing locally sourced materials, the building’s total cost was reduced by 50% compared to a conventional concrete structure and with further refinements in timber sourcing this design will save up to 70% on the concrete standard 23. Beyond cost savings, the construction process also benefited the local community by incorporating traditional skills, such as crafting the Takara, handwoven roofing and window systems, as well as coral infill walls. This approach not only minimized expenses but also celebrated local craftsmanship and community involvement. Kaunitz Yeung’s inclusive approach underscores the power of architecture to support not only education but also community resilience.

23 “Vanuatu School.” n.d. Kaunitz Yeung Architecture. https:// kaunitzyeung.com/project/vanuatu-school/.

24 Lawther, Peter. n.d. “Community Directed School Infrastructure Development in Vanuatu.” https://kaunitzyeung. com/wp-content/uploads/Peter-Lawther.pdf.

Fig 19 Vanuata School Structure from Exterior Source: Kaunitz 2012a

Fig 20 Construction with community involvement

Source: Kaunitz 2012a

Fig 21 Hand-woven natangura (sago leaf) roof, bamboo window hatches and dead coral infill walls

Source: Kaunitz Yeung Architecture

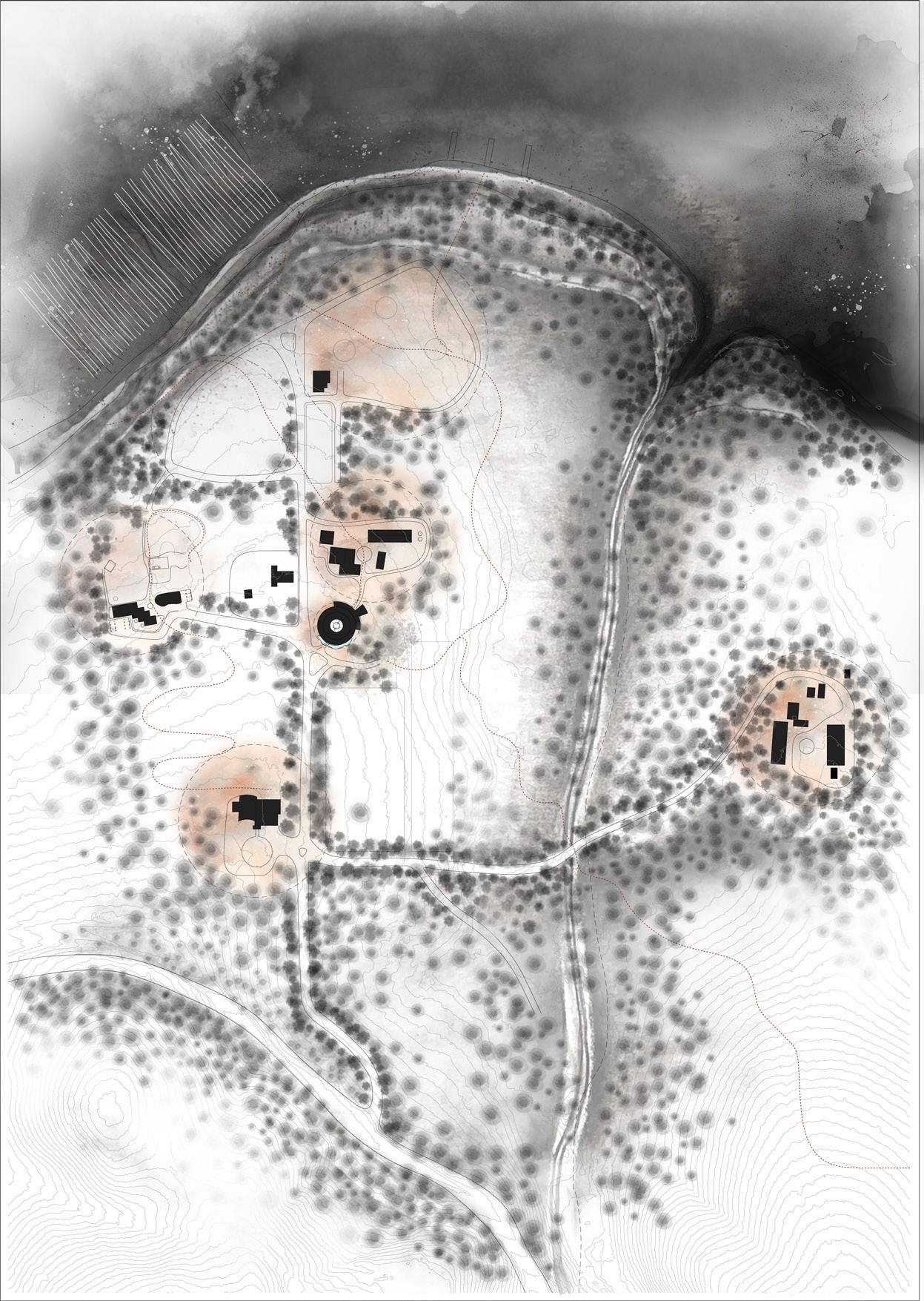

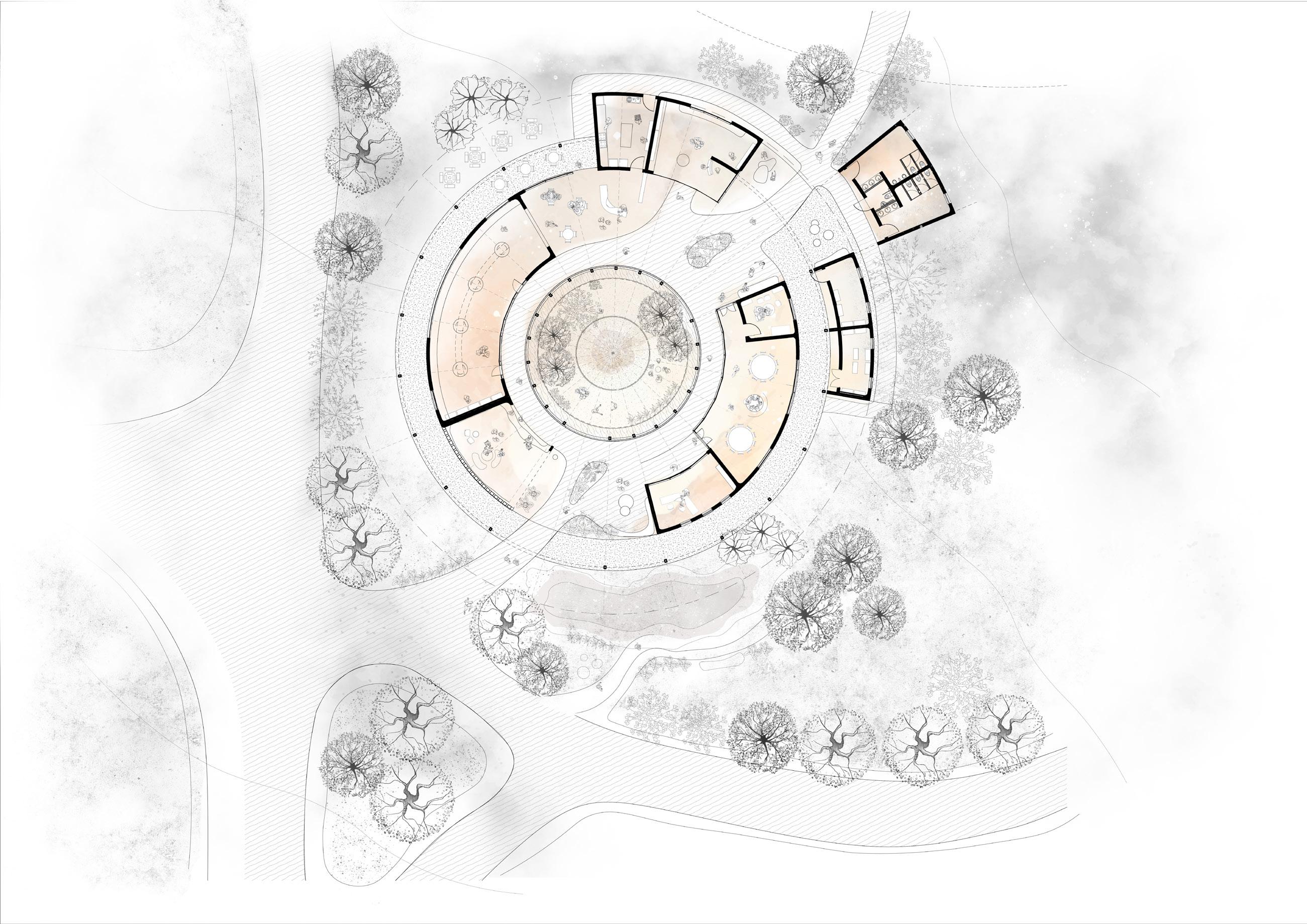

Jigamy Farm, a significant cultural site spanning 57.38 hectares across three parcels of land, has been developed since the 1980s and features a landscape that transitions between forested areas and open clearings 25. A central road reserve intersects the property, with the Princes Highway bordering its southern edge. This setting offers both accessibility and a connection to surrounding natural elements, making it ideal for an expansive and culturally rich master plan.

The master plan for Jigamy Farm was co-envisioned with the Twofold Aboriginal Corporation and the local Aboriginal community, placing a strong emphasis on celebrating Country and fostering community wellbeing. This collaborative vision seeks to honor the land’s cultural heritage and ensure its ongoing role as a safe, empowering space for all who visit. Jigamy Farm holds special importance as the site of the Giiyong Festival, a major cultural event that draws visitors from near and far to connect with the land and Indigenous traditions.

The comprehensive master plan for Jigamy Farm envisions a dynamic space that will include a Visitor Culture Center, art studios, an oyster farming operation, and a canoe workshop that pays homage to traditional practices. Additionally, the plan outlines spaces for community care and services, including an aged care facility, an office for Twofold’s operations, and a meal service. An eco-tourism section with 150 camping and cabin sites is also envisioned, offering visitors a place to stay and experience the land in a sustainable, respectful manner.

Each element of the master plan is carefully designed to be sensitive to the land and its cultural significance, creating a space that welcomes and celebrates the Spirit of Country while prioritizing the health and preservation of Country. This thoughtful approach reinforces Jigamy Farm’s identity as a place of learning, celebration, and community support, aligning with Aboriginal values of caretaking and respect for the environment.

25 Bega Valley Shire Council. Bega Valley Local Environmental Plan 2013: Planning Proposal, Environmental Zones – 5 Sites. July 2018.

The current Twofold office will remain as office space, with a new commercial kitchen building planned to the right of the office entrance. An extension will add a separate boardroom to the office to meet the Twofold members’ needs, using the same material palette for cohesion. The new kitchen, constructed from rammed earth to blend subtly with the office, will feature a fully equipped, compliant kitchen and meal service station, accessed by a dedicated driveway. The dining area will extend towards a vegetable garden, offering views over the lake.

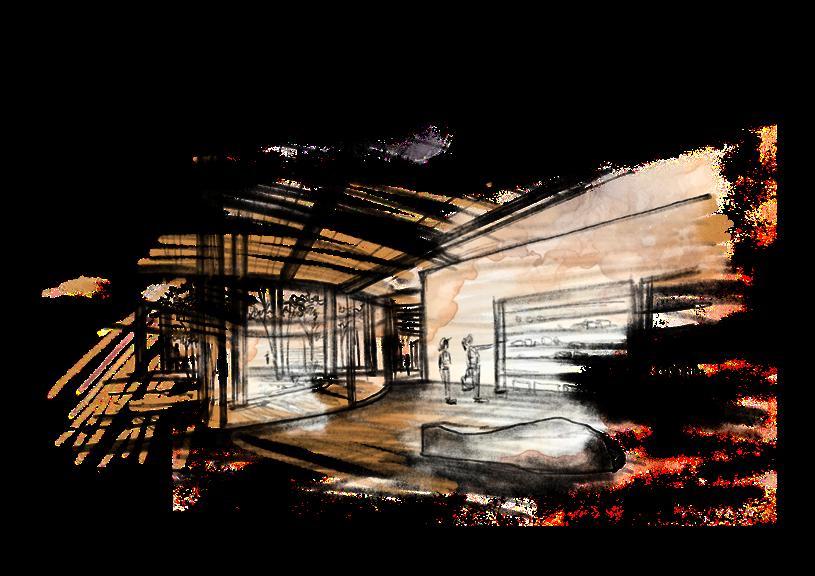

Sensory elements such as wind, water, and plant life contribute to creating immersive spaces that foster a holistic engagement between visitors and the environment. By integrating these natural elements, spaces can evoke multisensory experiences that deepen visitors’ connection to their surroundings, encouraging awareness, presence, and ecological sensitivity.

The circle is Universal, from Galaxy to the atoms the significance of circular can be identified. It symbolizes interconnectedness, continuity, and balance, reflecting a worldview where all beings—humans, animals, plants, and spirits—exist in a reciprocal relationship. Circles are central to community life, where gatherings, decision-making, and storytelling often occur in circular formations, ensuring everyone has an equal place and voice. This structure embodies a philosophy of equality and shared responsibility, as described by Deborah Bird Rose in Nourishing Terrains (1996), emphasizing that life is a continuous flow of relationships.

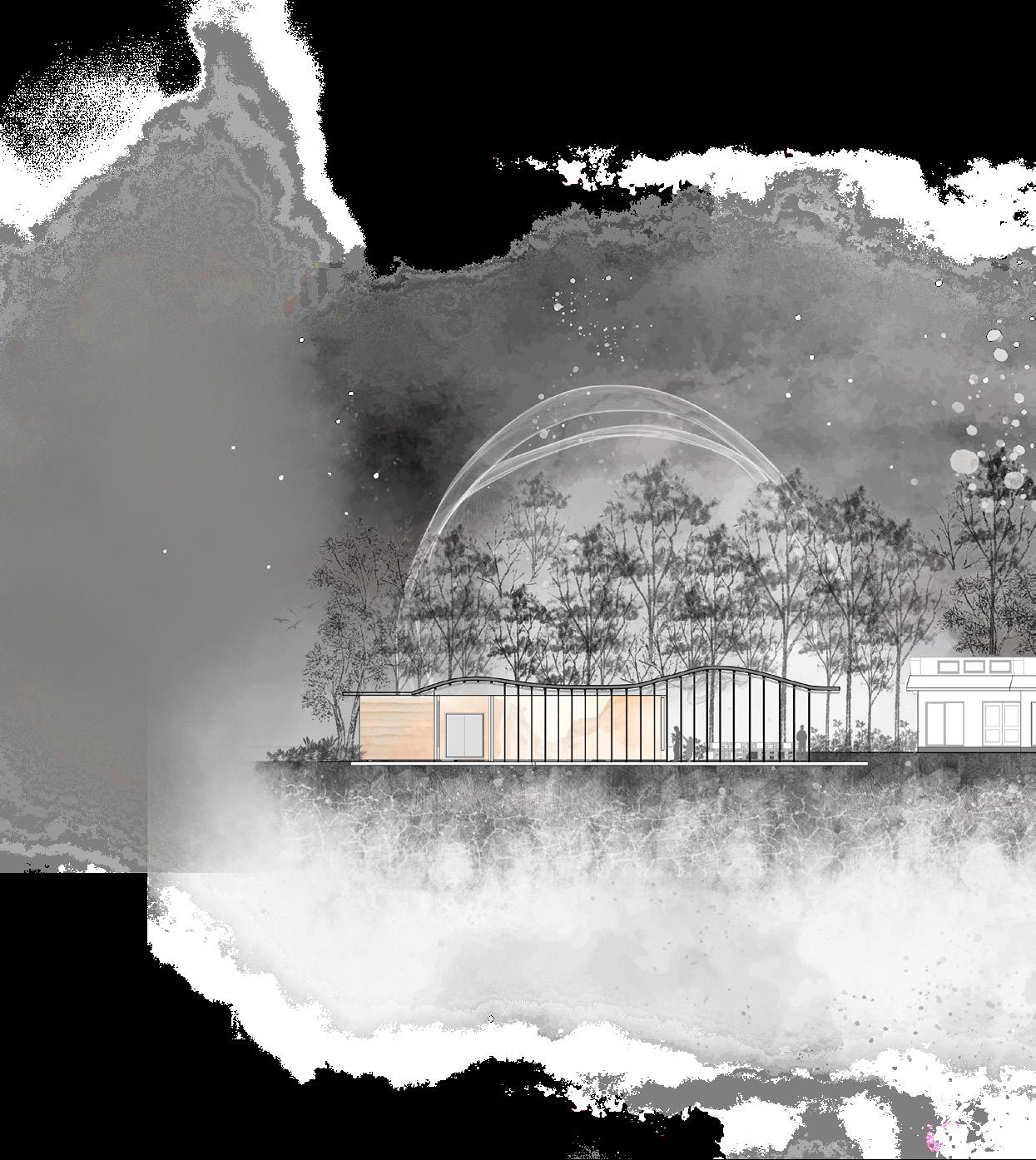

Source: David Rogers Photography

The Visitor Center welcomes all to the farm with a structure that honours the deep connection to the Country. Upon entering, guests are greeted by the Welcome Place, an inviting space that radiates warmth and hospitality, reflecting the cultural significance of the land from which it is built. The architecture tells the story of the land, symbolically enhancing its importance and embracing the spirit of the Country.

As visitors move through the space, they are invited to listen attentively to the sounds of the environment—the whisper of the wind, the rustling of leaves, and the flow of water—creating a symphony that resonates within the structure. At the heart of the design lies the Central Space, a dedicated area for healing, storytelling, communication, and respect. This space, rooted in tradition and cultural exchange, features a Hearth—a ceremonial fireplace that serves as a gathering point for reflection and community.

From this core, the structure branches out into other significant areas, including an outdoor gallery, cultural and bush walks, workshops, and camping sites—all of which invite visitors to engage deeply with the land and its stories. A path leads directly to the expansion of the Twofold Office, a key component of the project’s focus on growth and continued connection to the surrounding community.

The cultural center’s layout fosters an immersive journey, with a language center on one side and an art gallery on the other, seamlessly leading visitors toward a safe space and a community-run shop. The shop will feature locally crafted goods, generating revenue to support the community’s welfare initiatives. This design encourages visitors to pause, connect with the land, and engage meaningfully with Country before moving on to explore other aspects of the farm. This sequence of spaces is crafted to cultivate reflection and respect for cultural heritage, integrating commercial, educational, and cultural experiences in a holistic environment that serves both the community and its guests.

The project integrates innovative techniques in rammed earth construction, enabling on-site experimentation and learning. These methods will be shared with the local community through hands-on workshops, equipping participants with the skills and knowledge necessary to build and maintain structures independently. This approach fosters a sense of ownership and stewardship, resonating with the traditional Aboriginal relationship to the land, where soil is regarded as a living entity. Preparing rammed earth walls, floors, clay tiles, and roof tiles onsite serves as both a community engagement activity and a means of enhancing well-being. This initiative not only reinforces a direct connection to Country but also strengthens community bonds and cultural identity.

Handcrafted with care and technical expertise, the rammed earth walls become more than just functional elements; they embody the stories of Country. The layered earth walls not only honour the life cycle of the soil but symbolize the layers of history, culture, and spirit embedded in the land. The material’s natural properties also promote thermal efficiency and durability, further integrating the principles of sustainability and respect for the environment into the heart of the design. In this manner, the use of rammed earth is a vital connection to the land, its cycles, and the community, making the structure an organic extension of the environment it inhabits.

In honoring the spirit of Country, this project underscores the powerful connection between Aboriginal communities and their ancestral lands, recognizing Country as a sentient and enduring entity that holds memory, wisdom, and life. This approach fosters cultural continuity, a commitment to safeguarding traditional knowledge systems and deepening the understanding of land as a sacred part of life. Through the involvement of the community, here the Twofold Aboriginal community along with the use of local materials and sensory immersion, this work becomes a testament to sustainable practices informed by ancestral wisdom and community needs. By cultivating spaces that encourage deep listening and invite reconciliation, the project affirms the importance of preserving Indigenous perspectives, ensuring they continue to inform and guide us to the natural world.

Hence, this co-envisioned architectural dialogue contributes to the ongoing cultural resilience and ecological harmony, demonstrating the power of Indigenous knowledge in guiding collective stewardship and honoring the enduring spirit of Country.

Fig 42 Construction Process

Source: architexturez.net

Community

Performance

• The Uluru Statement. 2017. “Uluru Statement from the Heart.” The Uluru Statement. May 26, 2017. https://ulurustatement.org/the-statement/view-thestatement/.

• “DADIRRI by Miriam Rose Ungunmerr.” n.d. Www. youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pahz_ WBSSdA.

• “Discover Jigamy - the Gateway to the Bundian Way, Eden.” 2023. Bundianway.com.au. 2023. https://www. bundianway.com.au/jigamy.

• “The Land: Working with Indigenous Australians.” 2020. Workingwithindigenousaustralians.info. 2020. https:// www.workingwithindigenousaustralians.info/content/ Culture_3_The_Land.html#:~:text=The%20land%20 was%20not%20just.

• “Home | Twofold Aboriginal Corporation.”. TAC. https:// www.twofoldjigamy.org.au/.

• Rose, Deborah Bird. “Nourishing Terrains: Australian Aboriginal Views of Landscape and Wilderness”. Australian Heritage Commission, 1996.

• “Discover Jigamy - the Gateway to the Bundian Way, Eden.” 2023. Bundianway.com.au. 2023. https://www. bundianway.com.au/jigamy.

• Sullivan, M. E., and P. J. Hughes. “The Stuarts Point Shell Midden Complex: An Assessment of its Nature, Extent and Significance.” Australian Archaeology 15, no. 1 (2020): 27-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.1982.1 2092855.

• “Giiyong Festival.” 2024. Giiyong.com.au. Accessed 2024. https://www.giiyong.com.au/.

• “Sapphire Coast Aboriginal Cultural Experiences.” 2024. SapphireCoast.com.au. https://www.sapphirecoast.com. au/aboriginal-cultural-experiences.

• “Biomimicry Explained: Quieting Our Human Cleverness.” 2024. Anima Mundi Herbals Blog.https:// animamundiherbals.com/blogs/blog/biomimicryexplained-quieting-our-human-cleverness.

• “The Life in Soil - SARE.” 2023. SARE. July 24, 2023. https://www.sare.org/publications/farming-with-soillife/the-life-in-soil/.

• “What Is Earth Law? – Earth Law Alliance.” 2022. Earthlawyers.org. 2022. https://earthlawyers.org/earthlaw.

• Cao, Lilly. 2020. “How Rammed Earth Walls Are Built.” ArchDaily. February 11, 2020. https://www.archdaily. com/933353/how-rammed-earth-walls-are-built.

• “Liru and Kuniya.” ArchitectureAU. https://architectureau. com/articles/liru-and-kuniya/.

• “Cultural Centre Building.” 2017. Parksaustralia.gov.au. 2017. https://parksaustralia.gov.au/uluru/do/culturalcentre/building/.

• “Vanuatu School.” n.d. Kaunitz Yeung Architecture. https://kaunitzyeung.com/project/vanuatu-school/.

• Bega Valley Shire Council. Bega Valley Local Environmental Plan 2013: Planning Proposal, Environmental Zones – 5 Sites. July 2018.

• “Building With… Mud Bricks.” 2013. Completehome. July 17, 2013. https://www.completehome.com.au/newhomes/building-with-mud-bricks.html.

• world, STIR. “Thais Pupio Uses Rammed Earth to Design a Dwelling in Byron Bay, Australia.” Www.stirworld.com. https://www.stirworld.com/see-features-thais-pupiouses-rammed-earth-to-design-a-dwelling-in-byronbay-australia.

• Wroth, David. 2015. “Why Songlines Are Important in Aboriginal Art - Japingka Aboriginal Art Gallery.” Japingka Aboriginal Art Gallery. February 24, 2015. https://japingkaaboriginalart.com/articles/songlinesimportant-aboriginal-art/.

• “PechaKucha 20x20.” 2024. Pechakucha.com. 2024. https://www.pechakucha.com/presentations/designand-resistance.

• Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet. (2024). Country, culture and spirituality - Social and Emotional Wellbeing - Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet. [online] Available at: https://healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/learn/health-topics/ social-and-emotional-wellbeing/country-culturespirituality/#aihref10 [Accessed 10 Nov. 2024].

• Wroth, David, Japingka Gallery, and 2015. n.d. “Custodianship in Aboriginal Art.” Japingka Aboriginal Art Gallery. https://japingkaaboriginalart.com/articles/ custodianship-aboriginal-art/.

Bibliography:

• Campbell, Greg. Total Reset: realigning with our timeless holistic blueprint for living. Greg Campbell Consultancy Pty Ltd. March 1, 2022.

• Mayor, Thomas. 2019. Finding the Heart of the Nation;the Journey of the Uluu Statement towards Voice, Treaty and Truth. Hardie Grant Books.

• Yunkaporta, Tyson. 2019. Sand Talk. HarperCollins.

• Pascoe, Bruce. 2014. Dark Emu. Broome, Wa: Magabala Books.

• Memmott, Paul. 2007. Gunyah, Goondie + Wurley : The Aboriginal Architecture of Australia. St Lucia, Qld: University Of Queensland Press.

• Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjar Yankunytjatjara Women’s Council Aboriginal Corporation, and Magabala Books Aboriginal Corporation. 2013. Traditional Healers of Central Australia : Ngangkari. Broome, Western Australia: Magabala Books Aboriginal Corporation.

• Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr-Baumann. 1988. Ngangikurungkurr = Deep Water Sounds. Hobart: International Liturgy Assembly.

• “Connecting with Country.” n.d. Www. governmentarchitect.nsw.gov.au. https://www. governmentarchitect.nsw.gov.au/projects/designingwith-country.

• Pelizzon, Alessandro. 2015. “Aboriginal Customary Law: A Source of Common Law Title to Land.” Griffith Law Review 24 (1): 147–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/1 0383441.2015.1048583.