THINKING & LEARNING

Are You ARD Ready? How to prepare for the annual meeting to be your child’s best advocate 9 What is Slow Processing Speed? Early signs, impact on development & how to support your child 12 Dyslexia & Depression Decoded How the learning difference can impact a child’s mental health & signs to look out for 15 ‘Here’s What I Need’ Equipping kids with the skills to understand their needs & communicate them effectively

Restoring Order Why kids with ADHD struggle with disorganization & 10 ways to help them stay on top of the mess

The Big Picture 9 Stats around learning differences

ABOVE // Amanda Collins Bernier with her sons Max and Owen.

AOrder our Issues by Mail dfwchild.com/subscriptions

Subscribe to our Email Newsletters dfwchild.com/newsletters

Follow us on Instagram @dfwchildmag

Find us on Facebook facebook.com/dfwchild

Email us

Let us know what’s on your mind. editorial@dfwchild.com

S A PARENT, you wear many hats—caregiver, coach, chef, chauffeur, to name a few. But when you’re a parent to a child with a thinking and learning difference, you wear even more. You’re their advocate, cheerleader and champion.

While a learning difference diagnosis—something up 1 in 5 people will receive—can bring a sense of clarity, it can also bring new emotions. You might be navigating a world of IEPs, 504 plans or specialized educational support. You might learn to decipher acronyms, understand complex evaluations, and fight for the resources your child needs to thrive. And beyond meetings and paperwork, there’s the day-to-day parenting of a child who learns differently. You may worry about their self-esteem or battle over homework.

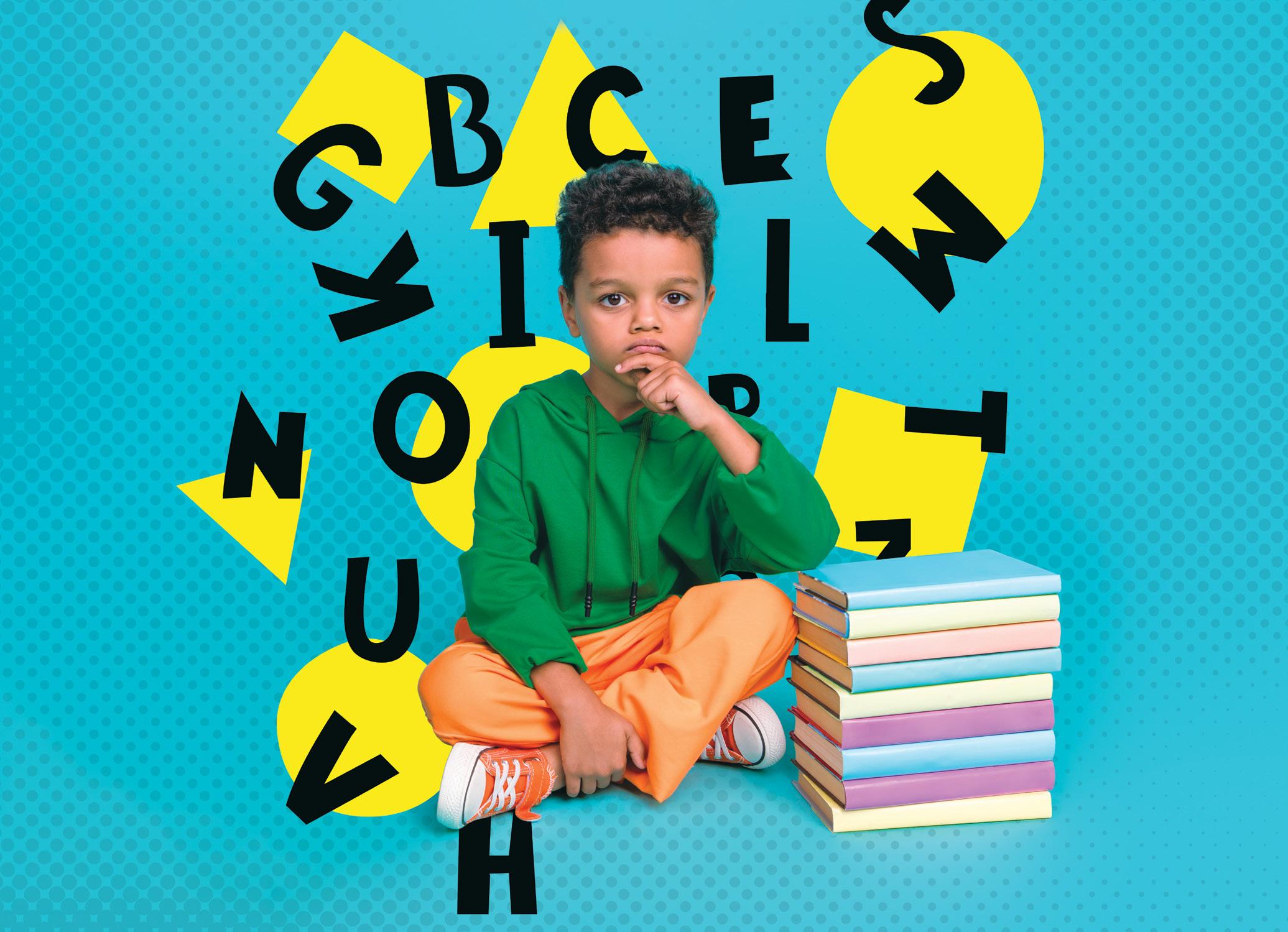

Here’s the thing: Learning differences, such as dyslexia, dysgraphia and ADHD (not a specific learning disability, but something that can significantly impact learning), are not indicators of low intelligence or a lack of effort. They are neurological differences that affect how individuals receive, process, store, and respond to information. In short, they’re a different wiring of the brain. And because there are so many facets to raising a child whose brain is uniquely wired, we bring you this annual issue, looking at the nuances of these common differences.

How do learning disabilities change the way our kids process things? Are kids who learn differently more prone to depression, and what can we do about that? And how can we best advocate for their needs—and, perhaps even more importantly, teach them to advocate for themselves? With expert guidance and actionable advice, this issue helps with all those other hats you wear.

PUBLISHER/ ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

Joylyn Niebes

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

Lauren Niebes

EDITORIAL

Managing Editor

Amanda Collins Bernier

Contributing Writers

Jennifer Casseday-Blair

Erin Hayes Burt

Gina Mayfield

Katelin Walling

DIGITAL

Digital Manager/ Publishing Coordinator

Susan Horn

Web + Calendar Editor

Elizabeth Smith

ART

Contributing Designer

Sean Parsons

ADVERTISING

Account Executives

Alison Davis

Nancy McDaniel

Advertising Coordinator

Emily McDaniel

ADMINISTRATION

Business Manager

Leah Wagner

HOW TO CONTACT US:

Address: P.O. Box 2269

Addison, Texas 75001

Phone: 800/638-4461 or 972/447-9188

Fax: 972/447-0633

Online: dfwchild.com

DFWChild is published bimonthly by Lauren Publications, Inc. DFWChild is distributed free of charge, one copy per reader. Only authorized distributors may deliver or pick up the magazines. Additional or back copies are available for $4 per copy at the offices of Lauren Publications, Inc. We reserve the right to edit, reject or comment editorially on all material contributed. We cannot be responsible for the return of any unsolicited material. DFWChild is ©2024 by Lauren Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or part without express written permission prohibited.

AYBE IT’S ALL NEW AND CONFUSING. Maybe it’s something you’ve done for years. But if you have a child with a learning difference, you know the ARD meeting is a key in your child’s education. This annual meeting can feel stressful for even the most seasoned parents of kids with unique needs. But you can go into it prepared and ready to talk through your child’s diagnosis, education and accommodations if you do a little work in advance. Here’s how.

BRUSH UP ON ARD BASICS

ARD stands for Admission, Review and Dismissal, a meeting to review your child’s eligibility for special education and related services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). About a third of students receiving services under IDEA have specific learning disabilities, making it the largest category of disability among students served under the act.

Once your child is determined eligible, you’ll work with a team of general and special education teachers, service providers and administrators to review your student’s current level of academic functioning and performance and create an Individualized Education Program (IEP).

The IEP will identify your child’s academic goals and objectives for the school year, what related services they will need and where those services will be implemented, says Sharon Ramage, J.D., who practices special education law with The Ramage Law Group in McKinney.

While ARDs are required to be held annually, you can call additional meetings if you think they’re necessary (like if your child isn’t

showing progress or there are any issues with the current IEP), says Melissa Griffiths, advocate, speaker, trainer and owner of DFW Advocacy. But she cautions that they shouldn’t be called excessively. If you do want to request an additional meeting, it must be done in writing, and “the rules say the school shall promptly convene the ARD meeting,” Ramage says.

As you discuss your child’s individualized education program, you may hear references to accommodations or modifications, two educational strategies that help students with learning differences learn by tailoring them to their specific needs. Here’s how these differ, according to the Texas Education Agency:

Accommodations: These change how your child learns or demonstrates knowledge. Accommodations are intended to reduce or eliminate the effects of student’s disability on academic tasks but do not change learning expectations. Accommodations are not one-size-fits-all; rather, the impact of a child’s learning disability determines the necessary accommodations.

Modifications: These change what your child is expected to master. Modifications typically reduce the requirements for state standards for what students should know and be able to do. With modifications, students access grade level curriculum through prerequisite skills.

Once you have an ARD meeting scheduled, it’s normal to feel anxious but there are things you can do ahead of time to reduce some of those unsettling feelings.

It’s a good idea to get a list of acronyms that are commonly used during ARDs, so you know what exactly is being discussed. Texas Education Agency’s spedtex. org is a good resource for this. And if you need clarification once you’re in the meeting, don’t hesitate to ask.

If your child already has an existing IEP, read it through and make sure you understand everything. Jot down any new skills your child has developed, any areas they’re struggling in, if anything could be done better or differently, what you liked about the previous school year and any questions you may have.

Ramage also recommends reviewing your child’s progress reports and evaluations, so you can go into the meeting with a prioritized list of what you want for your child. She cautions that you likely won’t get everything on your list, so come prepared with data and documentation for what you feel is most important.

In addition to progress reports, experts suggest getting records of the services your child has been receiving in school. This way, you can see documentation of their work and progress.

There are a few other things you should review and bring with you to the meeting, including independent evaluations (if you have them), progress reports from outside therapy providers and/or tutors and information about how your child

A quick reference guide to common acronyms.

ARD: Admission, Review and Dismissal

BIP: Behavior Intervention Plan

ECI: Early Childhood Intervention

ESY: Extended School Year

FAPE: Free Appropriate Public Education

FERPA: Family Educational Rights and Privacy

FIE: Full and Individual Evaluation

IEP: Individualized Education Program

MD: Multiple Disabilities

PLAAFP: Present Levels of Academic Achievement & Functional Performance

SLD: Specific Learning Disability

SI: Speech Impairment

SLP: Speech Language Pathologist

TEKS: Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills

is at home. Griffiths also suggests writing an “about me” page for your child and updating it annually to include things like your child’s likes and dislikes, how to best interact or not interact with your child and a photo to give the school a more holistic picture of your child.

And don’t forget a notebook to jot down notes, questions or ideas during the meeting.

ARD meetings can be very emotional for parents for many reasons. They can last anywhere from 1 to 3 hours. You might feel outnumbered with how many people from the school are in the meeting. And you’re discussing areas in which your child is struggling compared to their peers.

Griffiths and Ramage suggest the following tactics to keep the emotions at bay and be the best advocate for your child:

• Stay focused on your child and their needs.

• Bring support if you think you’ll need it.

• Be knowledgeable and firm about what your child’s needs are.

• Speak in a clear, calm voice. In Ramage’s experience, when a parent gets emotional in a meeting, the school can become defensive.

Above all, Griffiths recommends you “try really hard to take it from that perspective of, this information sounds difficult, but it doesn’t mean that [your] child is not important or is not going to progress or is not going to be successful in life,” she says. “It’s just this is, at this point in time, where they’re struggling, and these are the things that we can work on.”

WORDS JENNIFER CASSEDAY-BLAIR

T FIRST, YOU MIGHT just chalk it up to classic kid stuff. Daydreaming. Dilly-dallying. Taking forever to get out the door and off to school. But as time goes by, you start to realize it isn’t just a morning thing. Homework takes forever, even when your child understands it. They know the answer but pause so long before saying it. And multi-step directions? Forget about it. “Brush your teeth, grab your backpack and meet me by the door” might as well be a riddle in another language. If this sounds all too familiar, your child may have slow processing speed.

WHAT IS SLOW PROCESSING SPEED AND WHAT ARE THE SIGNS?

In simple terms, slow processing speed means a child

takes longer than their peers to take in information, make sense of it and respond. It can show up in all kinds of ways:

• Problems recalling and following verbal directions

• Taking a long time to write things down

• Trouble getting things done (getting dressed, doing homework, cleaning their room)

• Information learned is quickly lost

• Difficulty keeping up with conversations; gets lost easily in social interactions

• Struggling to finish tests or assignments on time

• Does not join in with class discussions

• Finds it hard to tune out distractions

• Becomes anxious, frustrated or tired as the day goes on

• Getting overwhelmed with multi-step directions

• Answering questions more slowly—even when they know the answer

Rebekah McPherson is a speech language pathologist at Key School and Training Center, a school in Fort Worth that serves students with learning differences, and a proud mom to Mitchell, a seventh grader there. McPherson says that she and her husband noticed very early on, when Mitchell was 4 or 5 years old, that he was not picking up on counting and the alphabet. She says, “Certain things weren’t coming naturally like writing his name. My background is in education, education technology and communication. I’ve been a teacher for 23 years, so I was aware of what kids should be able to do at a certain age.”

When Mitchell was in kindergarten, his teacher suggested to McPherson that he be evaluated. She says, “We sought an outside evaluation after speaking with Mitchell’s pediatrician … We found out he was dyslexic, and he also had ADHD in addition to slow processing speed.”

CAN SLOW

Mitchell’s situation isn’t uncommon. Slow processing speed often shows up alongside other learning differences, and it’s not uncommon for kids to experience more than one area of difficulty at the same time. For example, ADHD frequently co-occurs with slow processing speed. While ADHD is more about attention, focus and self-regulation, the added challenge of needing more time to take in or respond to information can complicate things even further. People with ADHD might struggle to get started on tasks or finish them quickly enough, especially in environments that demand fast thinking or rapid responses.

Dyslexia is another common co-occurring condition. Since dyslexia affects reading and language processing, slow processing speed can make decoding words or understanding text more time-consuming. Dysgraphia, which impacts writing skills, can also overlap—making it harder to get thoughts onto paper quickly or clearly. In some cases, slow processing speed may appear alongside anxiety, especially if the pressure to perform quickly leads to stress or worry. Recognizing these combinations can help tailor support strategies that address the full picture, not just one piece of it.

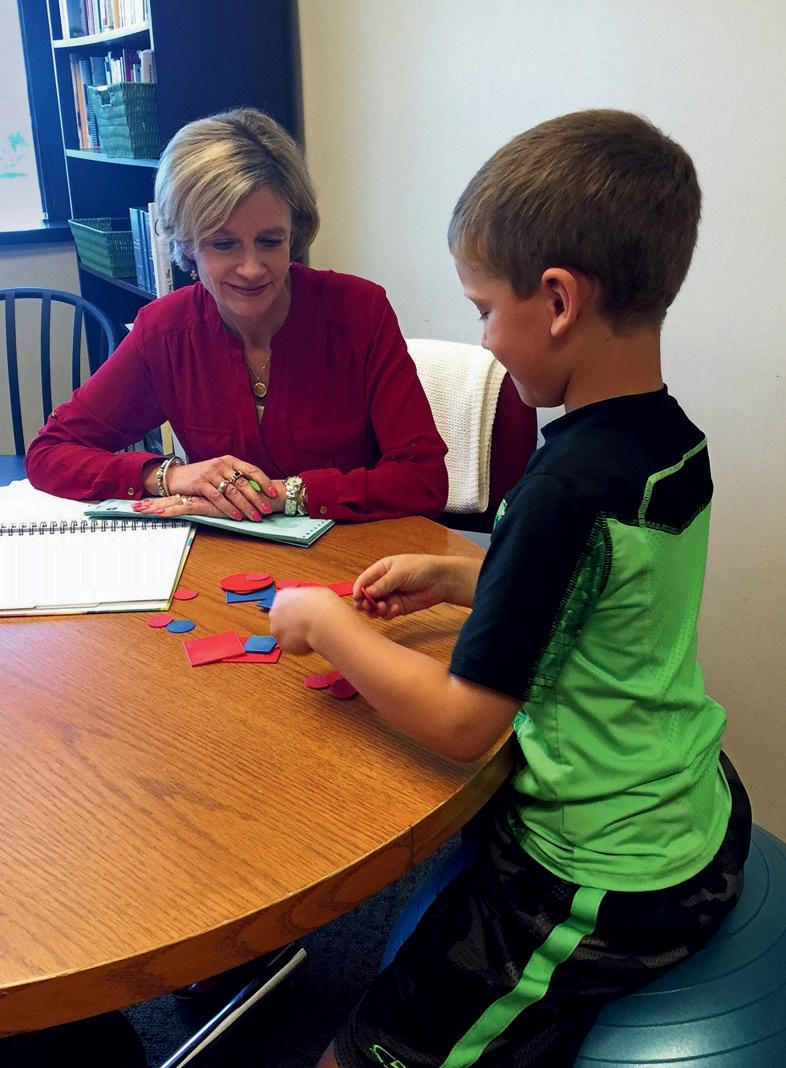

To find out if slow processing speed is what’s really going on, a formal evaluation by a psychologist or other qualified professional is the gold standard. This isn’t your average pop quiz. It includes a full battery of tests that measure cognitive, academic and executive functioning.

The process for diagnosing slow processing speed can involve different types of assessment. Occupational therapist Kyle Welch practices at Little Red Wagon Pediatric Therapy in Fort Worth, which offers specialized services (speech and occupational) for kids in a clinical setting. He says, “A psycho evaluation may be done by a school psychologist. There could be a clinical diagnosis where experts are examining cognitive or sensory delay. An analysis can be done of the child’s academic achievement and/or questionnaires completed by a family member or teacher.”

Part of the evaluation process includes timed tests. These performance tasks help reveal how efficiently your child’s brain is working when the clock is ticking. In addition, the assessor will screen for other possible culprits such as ADHD, learning differences (like dyslexia), or anxiety, to make sure slow processing speed isn’t a symptom of something else entirely.

HOW

Parents, try to imagine keeping up in a game where everyone gets the rules before you’ve even opened the box. That’s kind of what school can feel like for a kid with slow processing speed. They know the answer but didn’t get it out fast enough before the teacher moved on. They’re doing their best to write the sentence but can’t write as quickly as the other kids. They’re spending so much energy just listening and keeping up that by the end of the day, they feel destined to fail. It can lead to frustration, low confidence, and that heartbreaking “I’m not good at school” feeling—even when they are.

Carson James Boswell is an educational diagnostician at the Key School. She explains that there are many classroom tasks

7 ways to help your child with slow processing speed excel at home

1. Keep routines simple and predictable. Knowing what to expect helps reduce overwhelm.

2. Break tasks into small, manageable steps. One thing at a time is easier to process than a long list.

3. Give extra time to respond. Be patient and avoid rushing your child when they’re thinking or answering.

4. Use visuals and checklists. Pictures or written reminders can help your child stay on track.

5. Celebrate effort, not just speed. Praise them for trying and sticking with tasks, even if it takes longer.

6. Build in quiet time. Downtime helps your child reset and process their day.

7. Stay calm and encouraging – Your relaxed energy helps them feel safe and supported.

that can be affected by slow processing speed. “Reading difficulties can interfere with comprehension, which can mean the child has to take the time to reread the content. Writing difficulties may limit their output because of time factors. Language difficulties can make it hard to retrieve information, and then they can’t get thoughts out as quickly. In subjects like math, there might be difficulties with automatic computation,” she says.

McPherson says it’s because of Mitchell’s placement in the Key School that his academic experience hasn’t been negatively affected. “The school is made for those with learning differences. It’s already built into the day-to-day that students have more ‘helps,’ so it is not viewed as anything extra. Audio books…everybody gets them. Text to speech technology…everybody gets it. Because Mitchell has always been in a specialized school, it is such a better situation. He is thriving.”

For kids with slow processing speed, social interactions and emotional well-being can be interrupted. It can be tough for your child to keep up. They might miss the joke, not know when to jump in, or respond a beat too late. And sadly, that can make them feel left out, or like they don’t quite fit. Welch says, “As children with slow processing speed get older, beyond kindergarten and first grade, they may experience frustration, embarrassment, and anxiety. That’s not just in the classroom; it can be while they are playing school sports that require rapid skill execution.”

If your child is exhibiting slow processing speed and in public school, they may require additional support to thrive academically and socially. To ensure equitable access to education, these students may benefit from a customized plan that can provide targeted accommodations or modifications.

ARE KIDS WITH SLOW PROCESSING SPEED ELIGIBLE FOR AN IEP OR 504 PLAN?

“Once there is a formal diagnosis of slow processing speed, a 504 plan is established. An IEP (Individualized Education Program) will also be implemented. This doesn’t mean the student will have to be in special education,” Welch says.

An IEP is like a custom-built support system for your child at school. It includes all the bells and whistles—specialized instruction, therapies, accommodations, maybe even a modified curriculum. It’s detailed, written down, and legally binding. A 504 plan, on the other hand, is more like a helpful nudge to level the playing field. It’s for students who don’t need specialized instruction but still face challenges because of a learning difference. This plan helps remove barriers so they can learn alongside their peers.

Certain accommodations and modifications can be extremely effective in supporting slow processing speed in the classroom. Welch says, “Extra time is No. 1. I am a big proponent of the use of technology to eliminate some of these barriers. Text to speech, for one, is great because the student doesn’t have to focus on note taking but can instead just listen and absorb the information. Other modifications may include a reduced workload or breaking down the instructions for tasks a little bit more.”

Boswell agrees that a reduced workload can be beneficial for these students in most situations. She says, “If the child can show that they’ve mastered the subject in five problems instead of 10, why not do that?”

HOW CAN PARENTS SUPPORT A CHILD WITH SLOW PROCESSING SPEED?

“At home, it’s helpful to make a visual schedule. Be up front about time and be consistent by establishing routines. Parents

These tech tools can help kids with slow processing speed excel in the classroom

• Voice-to-Text Software: Use tools like Google Docs’ voice typing to turn speech into text.

• Smartpens: Record audio while writing notes by hand.

• Google Read & Write Toolbar: Offers text-tospeech, word prediction, and more.

• Interactive Learning Platforms: Break lessons into smaller, easier-to-understand pieces.

• Time Management Apps: Help students plan tasks, set reminders, and stay on track.

• Reading Speed Tools: Help boost reading speed and comprehension.

• Visual Aids: Charts, graphs, and images help explain ideas quickly.

can limit distractions when their child is doing homework and should consider implementing breaks and dividing homework into smaller segments to avoid fatigue,” Boswell says. “For most of these kids, their brains are working in overdrive. Another helpful tip is to set microdeadlines. For instance, if you have a big deadline on a certain date, come up with smaller deadlines along the way to help them stay on track.”

Welch says that some therapeutic interventions may help improve processing speed over time. “Repetitive practice helps create muscle memory. It’s important when having a child do a task that they are doing it the exact same way every time. An example of this is teaching a child to tie their shoes. You don’t want to show them three different ways to do it. There needs to be consistency. It’s also important to take the time factor off the table so that the child doesn’t feel rushed,” he says.

The biggest takeaway that McPherson wants people to have is that just because you have slow processing speed, it doesn’t mean you’re not smart. She says, “Mitchell understands that. He feels confident. He says, ‘I know I am a slow reader, but I have a really good vocabulary.’ He’s aware of his weaknesses, but he’s also aware of his strengths.”

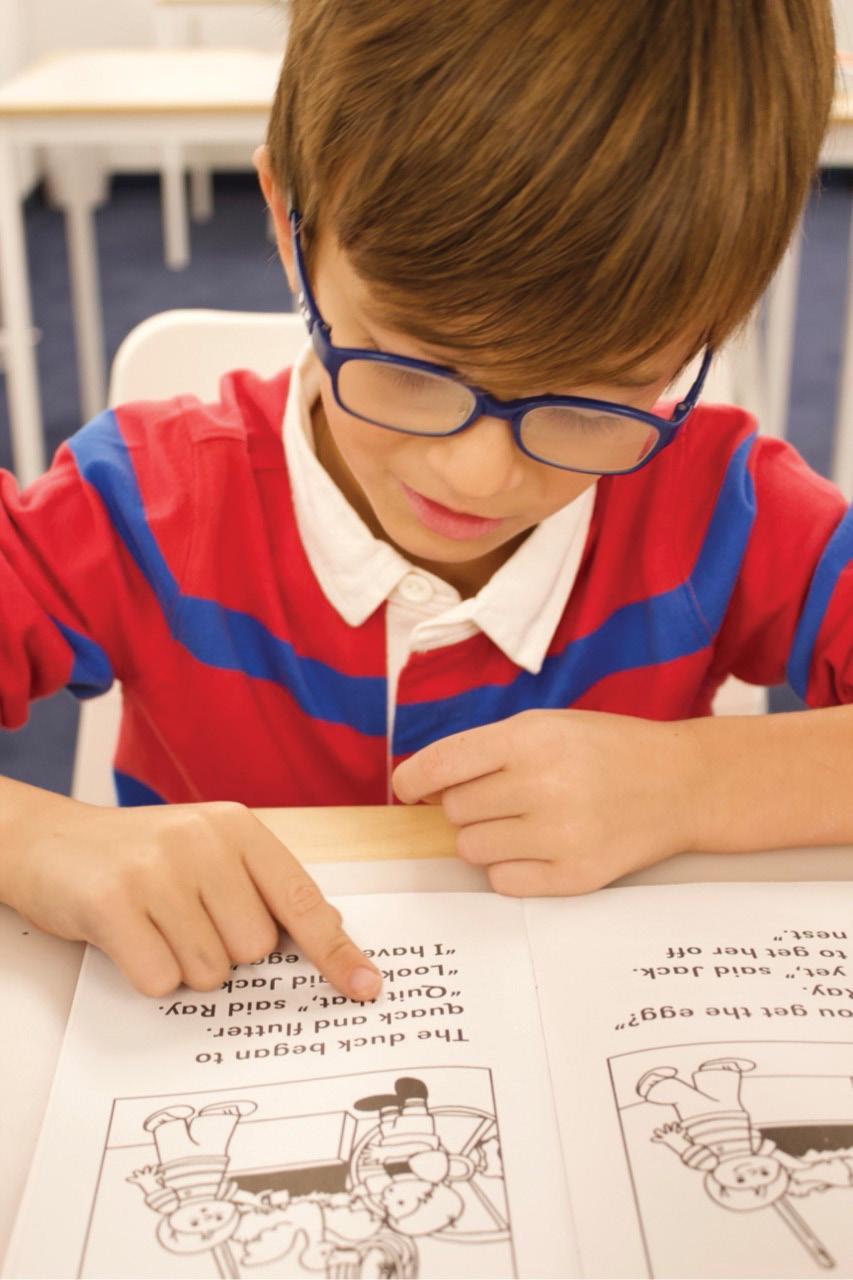

ARA EASTER, AN ARLINGTON MOM OF THREE, knew something was wrong as soon as her youngest son started kindergarten. “By the end of pre-K, he was just really struggling with learning the ABC song and identifying letters and sounds,” she recalls. Then shortly after starting kindergarten, her outgoing, happy boy began crying every day at drop-off. “He wouldn’t talk much in class. He was just a different kid. The teacher was doing everything she could to help him, but there was just clearly something wrong.

“I figured we were probably looking at dyslexia because his reading was really where he struggled…it just was not clicking.”

How the learning difference can impact a child’s mental health & signs to look out for

WORDS ERIN HAYES BURT

Dyslexia—the most common specific learning disability, affecting up to 1 in 5 kids—can impact more than just how a child learns and reads. Individuals with dyslexia are at a higher risk of experiencing anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and other mental health challenges due to the academic and social difficulties associated with the condition. Like in Easter’s son’s case, sometimes stress, tears and isolation are secondary symptoms of the root cause.

The good news is with the right support, dyslexia can be managed, and kids can thrive, but the earlier it’s caught the better. Here’s more on this common learning difference, and how it can impact your child’s learning and mental health.

Popularly, dyslexia is associated with swapping letters or numbers in context, but it’s more complicated than that. Dyslexia is a difference in how some information is processed in the brain. Often, it appears alongside other processing disorders, like ADHD or auditory processing disorder. Individuals can have a processing difference in one area—such as reading, math or writing—or in all areas.

“It’s an unexpected difficulty learning to read and spell, despite getting the same reading instruction everyone else gets,” explains Dr. Sheryl Frierson, medical director of the Luke Waites Center for Dyslexia and Learning Disorders at Scottish Rite for Children in Dallas. “It’s unexpected for a couple of reasons. First of all, it’s not a lack of instruction. It’s not a lack of having other strengths in learning. Oftentimes, individuals with difficulty learning to read due to dyslexia have very high IQs or very advanced vocabulary skills and are able to express their ideas verbally very well. They may have gifts in art, music, math.” They have to be pretty smart to keep up, says Laurie Peterson, founder and executive director of Diagnostic Learning Services, with locations in Fort Worth and Plano, which specializes in diagnosing learning and processing disorders. “In those first three [school] years, we teach phonics the same way we’re teaching letter sounds, but for a child with dyslexia, it’s like we’re teaching it in German. It’s like a different language.”

Mild dyslexia can be easily masked by students who use their comprehension skills to compensate for not being able to decode words. But it can show up early. “He had struggled with switching ‘pa-sketti’ for ‘spaghetti,’ or ‘ma-rote’ for ‘remote,’ but we just thought it was adorable,” says Richardson mom Brandi Nortman, whose son Max was diagnosed in grade school. “We would’ve never thought that’s an early sign of dyslexia.”

“Trouble with rhyming or mispronouncing words is a big one,” says Stacy Cox, a TEA-certified educational diagnostician and owner of the Texas Center for Educational Testing in Flower Mound. She also looks for anxiety associated with reading out loud. “Even in college kids and adults, you can just see the change in their demeanor as soon as you ask them to read.”

But dyslexia can manifest differently in boys and girls which may lead to girls being underdiagnosed. Research suggests that when boys are struggling in class, they’re more likely to disengage in disruptive ways, while in girls, it may be less obvious. Boys may act out or become class clowns to avoid doing things that are hard for them. Girls tend to avoid participating, says Deana Lee, a provider of dyslexia instruction for Little Elementary in Arlington. “The older they get, the more they will avoid,” she says.

IS DYSLEXIA LINKED TO DEPRESSION?

Dyslexia and mental health concerns like depression may appear together because of the stress the condition can cause or the wearing on a child’s self-esteem. “If you do have dyslexia, you’re more likely to be exposed to being misunderstood, having false assumptions about your motivation and your ability to work,” explains Frierson.

The condition may also lead to social isolation, as kids might rather miss school than struggle in front of their peers. “They’ll go to the bathroom a lot during class. They don’t want to participate. If they’re asked to read in front of a class, they’re not going to do that. They’re going to go to the bathroom, need to go to the nurse,

According to Understood For All, Inc., a nonprofit organization providing support and resources for people with learning differences, depression in kids with dyslexia looks pretty much the same as it would in any kid. If you think your child may be depressed, it’s important to seek help from a mental health professional.

HERE ARE SIGNS TO LOOK OUT FOR:

• Feeling very “down”

• Changes in sleep and eating habits

• Withdrawing from friends or favorite activities

• Refusal to do homework or go to school

• Feelings of hopelessness

or just leave class,” says Lee. This avoidance and procrastination can lead to a cycle of disorganization, anxiety and depression as they get further behind in school.

The older students are when they get diagnosed, the more they struggle with selfesteem. And those feelings can linger at the back of students’ minds long after the struggle is gone. But here’s the good news: Feelings of depression and anxiety can start to turn around on their own when students start to see progress. “That confidence begins to boom,” says Peterson. “The kids are picking up books, and they’re getting excited about reading. It’s phenomenal.”

A dyslexia diagnosis gets your student into their school’s program, where they learn to read in a way that makes sense to the dyslexic brain. Students who start in first grade will generally be doing a two-year program that gets them on the same page as their peers by third grade. The older a student is, the longer it can take to get them caught up, which is why Scottish Rite also developed a program for older students, says Frierson.

In addition to learning how to read in a way that makes sense to them, kids with a dyslexia diagnosis get accommodations that make it easier for them to focus on their work without reading getting in the way. This might look like verbal test-taking, more time on tests, getting word banks, or using manipulatives. “When they first begin, we give them a lot of accommodations,” explains Lee, the dyslexia instructor at Little Elementary. “Then, as they go through the program, we start trying to pull those accommodations away to get them more independent.”

Students may continue to use accommodations on tests well after they have outgrown them for daily work, or for subjects other than reading and writing, so their ability to decode doesn’t get in the way of showing mastery in another subject.

Once kids get the right support and start making progress, the change can be almost instant. Easter vividly remembers her son Cooper’s first day in class with a reading specialist. “I picked him up and he was like, ‘Mom! Did you know that dyslexia isn’t being dumb?’ He was just so excited to tell me about these famous people who were dyslexic. By the end of first grade, he was completely back to his normal personality. He loved school. He still talks about first grade as one of his favorite years.”

“When it comes to strengths, competence builds confidence and plants the seeds for lasting growth.”

That’s a command so many of us have heard in life, sometimes lobbed at us by kind-hearted parents, teachers and even coworkers in a well-meaning attempt to push us into self-advocacy. Thankfully, these days we’re learning the importance of giving our children tools and resources that encourage them to constructively state their needs and represent who they are to the world. Otherwise, telling them to speak up for themselves is kind of like asking them to solve a complicated math problem without any strategies for finding the solution.

The ability to self-advocate matters because it allows our kids to problem solve for what they need and know how to ask for help. When they understand their value and can express themselves clearly, they’re able to say yes or no with confidence to big and small decisions, promote or defend themselves and motivate their peers to do what’s right. For children with thinking and learning differences, those skills may translate into explaining a learning disability by sharing how they use their strengths and accommodations to succeed in school. We don’t want our children just along for the ride of life, we want them in the driver’s seat, clearly able to express themselves as best they can to make sure their voice is heard in a productive way.

To learn more about self-advocacy, we reached out to local expert Amy Cushner, associate head of early childhood to sixth grade at the Shelton School in Dallas, a private nonprofit and the largest independent school worldwide for intelligent children with learning differences. She holds an M. Ed., is a certified academic language therapist, qualified instructor in multisensory structured language education programs for written language disorders and is Montessori certified. Perhaps most importantly, she tells us she has “30 years of joyful experience in working with children with learning differences and their families.”

Here’s what she had to say.

Advocacy doesn’t always mean shouting from a stage–sometimes it’s just having the courage to say, “This is what I think, and it matters.”

One of the most significant barriers to student self—advocacy is recognizing when help is needed. As children grow older, how do we, as parents, help them recognize their strengths and struggles? In my experience, when children enter collective education and begin comparing themselves to others, the recognition of their struggles begins. This awareness often stems from our human tendency to notice what we cannot do before recognizing what we can.

As a parent, listen first. Pause. See if more details emerge that help you understand the level of struggle. Then, ask a variation of one of these questions:

• Would you like my help?

• How would you like to handle this?

DFWChild: How early, age-wise, can you start teaching your child to self-advocate, and what does that look like?

AC: Advocacy, simply put, is using language to convey our thoughts. A young child begins developing this ability as language emerges. Even an infant crying is a form of advocacy.

As a child matures and acquires language, “no!” becomes advocacy. It then builds into phrases, sentences and justifications. Ever find yourself justifying to a 5-year-old why it’s bedtime? That 5-year-old is using language as advocacy.

Each experience a child has with advocacy leads to a greater understanding of situational relevance and the guardrails that define what is “appropriate” advocacy.

• Do you want to act on this?

These questions are proactive and create a template for agency. Agency is activation and empowerment. When it comes to strengths, competence builds confidence and plants the seeds for lasting growth. The wise person places themselves in situations where success is achievable.

What should a parent do? Watch. Observe your child. What captures their attention and focus? What do they spend time thinking about or interacting with? These are their strengths. Parents can then provide affordable opportunities to explore these interests. Even if these attempts are not sustainable or successful, they become moments of embodied confidence and self-development.

A note of caution: Showering a child with compliments can create a reliance on others’ opinions, which can lead to a more subjective self-esteem.

How do we help children communicate their needs and rights?

Begin with a family-wide approach to open dialogue–for everyone, not just the adults. Create a mantra or phrase that embraces advocacy with civility. For example: “I see that differently.”

This kind of statement is respectful, opens the door to further discussion, and acknowledges different perspectives. One of my favorite quotes, from an article I read years ago, sums it up beautifully: “Different is not right or wrong. It’s just different.”

How does the ability to speak up positively impact students’ learning, self-image and independence?

I see children as active participants in their learning, and their voices are valued. Speaking up helps them communicate their needs, thoughts and feelings clearly, which fosters independence. By engaging in conversation, asking questions, and making choices, children are not only developing language skills, they are cultivating critical thinking, problem-solving abilities and emotional intelligence. What more could we want?

Why kids with ADHD struggle with disorganization & 10 ways to help them stay on top of the mess

WORDS KATELIN WALLING

ET’S BE HONEST: When a room gets messy and disorganized, it’s pretty overwhelming for anyone to get started. But when your little one has an ADHD diagnosis? The struggle to get your little one to focus and the frustration you feel is—as they say—real.

Why? It largely comes down to challenges kiddos with ADHD have with the executive functioning skills that many unconsciously use every day.

Think of executive functioning as the CEO of your brain. It helps you pause, see the bigger picture, and make connections between ideas. In short: “When our executive function center is on, we think before we act. When it’s off, we act before we think,” says DFWChild Mom-Approved counselor Laura McLaughlin, M.Ed., LPC-S, RPT-S, ADHD-certified clinical services provider

and founder of HeadFirst Counseling in Dallas.

When it comes to staying organized or cleaning a messy room, children with ADHD may have challenges with executive function skills that include the ability to control thoughts, actions, emotions and focus. They may also struggle with remembering things in the moment, aka working memory, initiating tasks, particularly when distracted and overstimulated, as well as planning and time management.

With these challenges, it might seem like keeping your child more organized is a lost cause. But with the right strategies, they’ll develop those skills and learn to keep things picked up.

But what are those strategies? Try these on for size to see which one your child responds to best:

Break things down into smaller tasks. When you tell a kiddo to clean their room, it’s too large of a task and they don’t know where to start. And if you give them a list, chances are they’ll only remember the last thing you said. So give them one step at a time until their room is picked up.

Work together as a team. Whether you’re in their room giving them one task at a time or working together, younger kids are motivated by that sense of connection. Plus, “having you by their side will help them to stay focused and help it feel more like quality time than just a chore,” says Brianna Henderson, MS, LPC, RPT, founder of Lily Pad Child & Adolescent Counseling in Frisco. Make it more stimulating. Changing up tasks just enough to make them feel new and exciting can help sustain your kiddo’s focus and attention a little longer, McLaughlin says. Some ideas?

• Set a timer and ask your little one how much they can get done in 2 minutes.

• Turn off the lights and have her use a flashlight to put everything in their room away.

• Challenge him to do a rainbow cleanup, putting things away one color at a time.

• Put on a fun song and tell them they have to pick up and

When it comes to staying organized or cleaning a messy room, children with ADHD may have challenges with executive function skills that include the ability to control thoughts, actions, emotions and focus.

organized as much as possible while the music is playing.

Create a checklist. It’s hard for kids with ADHD to remember verbal requests, and they respond better to visual cues, McLaughlin says. For younger kiddos, create a picture list to prompt them to tackle specific tasks, but keep it to no more than three to four or it could get overwhelming. With older kids, try a chore chart with short reminders they can check off: make your bed, dirty clothes in hamper, stuffies in basket, LEGO bricks in bin, etc.

In an ideal world, there is no overwhelming mess in the first place. So what can you do to help prevent it?

Set ground rules for all the kiddos in the family. Some parents choose to set limits like only two toys can be out at a time to help mitigate the mess. If your little one has LEGO bricks and dolls out, one has to be put away before the trains come out.

Try a minimalist approach. It’s hard for anyone to keep an overloaded room, desk, backpack, etc. organized, so having fewer things in general is better. If you have the room, consider keeping toys in a separate room. At the very least? Purge your kid’s toys, clothes, books and shoes as they outgrow them.

Rotate out the toys. If your child has a lot of toys, chances are they don’t play with everything all the time. It may be a good idea to put some toys in storage for a few months and rotate the stock. Sure, it’s going to take up some of your time, but it’ll cut down on how much they have to clean up.

Create routines. Kids with ADHD thrive on structure and routine, Henderson says—whether that’s one task per day or Saturday mornings are for cleaning. But remain flexible when things come up, like an invite to a playdate when they’re “supposed” to clean.

Add storage in their room. Make it easy for your kiddo to know where things go with a storage bin for each type of toy. It’ll likely be more helpful for your child if the room is less visually stimulating, McLaughlin says. Just make sure they don’t get too big; the bigger the tote, the more stuff can be shoved in, the more chaotic it can get.

Determine your non-negotiables. In an ideal world, your little’s room is always spotless, but that’s just not realistic. Instead of aiming for perfection, Henderson suggests deciding on a few non-negotiables—like making the bed, blocks picked up—and focusing on those rather than getting upset about every little thing that could be out of place.

A mess is guaranteed to annoy any parent, especially when it feels like you’re nagging your kiddo to just pick up their toys or clean out their backpack. When you’re feeling at wit’s end, first, give yourself some grace. “Just because you know that your kid has ADHD and has these struggles doesn’t mean it suddenly becomes easy to accept it whenever it happens,” Henderson says. “You’re still allowed to feel frustrated.”

Then take a moment to take a deep breath, pause before reacting, reset your expectations, and focus on achieving those nonnegotiables you already determined.

Fort Worth; 817/336-0808; link-ed.org

We provide diagnostic testing for families of individuals with learning differences or disabilities such as dyslexia, dysgraphia and ADHD, as well as provide career and strengths testing. We also link educators to current professional development resources and training. See ad on page 14.

Beckloff Behavioral Health Center

Dallas; 972/250-1700; drbeckloff.com

We are a full-service counseling center, offering counseling to all family members. We serve children, teens, young adults and regular adults, too! We have state-of-the-art play therapy rooms and activity rooms (pool table, etc.) to connect with kids and teens. See ad on page 5.

Cole Health

Frisco; 469/840-9670; colehealth.com

Cole Health provides life-changing speech, occupational and ABA therapy services to children of all ages and abilities. We are about making a real difference in real lives. See ad on page 5.

Dallas Academy

Dallas; 214/324-1481; dallas-academy.com

For 60 years, Dallas Academy has been enriching the lives of learning different students. We serve bright students in grades 1–12, have small class sizes, college preparatory curriculum and traditional school offerings (Athletics/ Arts/Clubs). See ad on page 8.

Fairhill School

Dallas; 972/233-1026; fairhill.org

Fairhill builds confidence/self-esteem in students with learning differences. With smaller classroom sizes and continuous check-ins from educators, students can tune in on their strengths and grow in

places where they need help without judgment. Come tour our newly renovated campus. See ad on page 8.

Hill School of Forth Worth

Fort Worth; 817/923-9482; hillschool.org/our-difference

Hill School partners with families to provide an education for students who learn differently by addressing the needs of the whole student in a supportive environment.

See ad on page 23.

Jane Justin School

Fort Worth; 682/303-9356; childstudycenter.org

Jane Justin School provides state-ofthe-art special education to students with disabilities ages 5-21. Our mission is to foster the knowledge and life skills necessary for students to achieve productive and meaningful lives while respecting and embracing their individuality. See ad on page 24.

Key School and Training Center

Fort Worth; 817/446-3738; ksfw.org

Founded in 1966, Key School and Training Center has a mission to unleash student and teacher success through individualized instruction, training, and advocacy. Today, we operate three programs including the K–12 school, Key Summer Program and the Training Center. See ad on page 25.

The Novus Academy Grapevine; 817/488-4555; thenovusacademy.org

The Novus Academy actively seeks to shape a future where neurodivergent learners are valued for their ability to think in creative and innovative ways. Our supportive school climate sets our students up for overall success. See ad on page 14.

Oak Hill Academy Dallas; 214/353-8804; oakhillacademy.org

Oak Hill Academy provides complex, neurodiverse students with a tailored, whole-child learning experience to empower our students and their

families to reach their full potential. OHA celebrates each student’s uniqueness and creates a customized learning path for growth and independence. See ad on page 2.

Preston Hollow Presbyterian School

Dallas; 214/368-3886; phps.org

For over 60 years, PHPS has empowered students with learning differences in Dallas. In Fall 2025, we continue that legacy at a new, state-of-the-art campus—advancing personalized education in a supportive, nurturing learning environment. Inquiries now open for K–5. See ad on page 27.

Shelton School

Dallas; 972/772-1772; shelton.org

The Shelton School & Evaluation Center is the largest independent school for students with learning differences, including dyslexia, ADHD and other language-based disorders. Shelton serves students from Early Childhood–12th grade with an individualized curriculum and a multisensory approach.

See ad on page 14.

Art of Problem Solving Frisco; 469/200-1010; aopsacademy.org/campus/frisco

AoPS Academy is an enrichment program for grades 1–12, offering after-school and weekend classes for highly-motivated students. Students develop their creativity, critical thinking and complex problem solving skills with outstanding peers and mentors. See ad on page 22.

Pacioretty Academics

Dallas; 469/466-9385; pacioretty.com

At Pacioretty Academics, we understand that each child is different, and we’re here to help them shine, from Pre-K through grade 12. Our dedicated team of professionals provides personalized support with the aim of mastery in a range of subjects. See ad on page 26.

1 IN 5 CHILDREN IN THE U.S. HAS A THINKING OR LEARNING DIFFERENCE

10%

Of people will get a learning disability diagnosis in their lifetime

½

YOUNG ADULTS WITH LD ENROLL IN FOUR-YEAR COLLEGES AT HALF THE RATE OF THE GENERAL POPULATION

700,000

9 Stats around learning differences

COMPILED BY AMANDA COLLINS BERNIER

AS MANY AS 20% OF CHILDREN in the U.S. grapple with thinking and learning differences, ranging from attention disorders to difficulties with reading, math or writing. Take a look at just how common these differences are, and the impact they can have on individuals and learning.

NO.1

“Specific learning disability” is the most common disability type among students served under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

20%

Of people are estimated to have dyslexia, the most common learning difference, accounting for at least 80% of all learning disabilities

Public school students in Texas had an IEP (Individualized Education Program) in 2023, for learning differences or other impairments; about 11% of students in the state

80%

THE AMOUNT OF TIME MOST KIDS WITH LEARNING DIFFERENCES SPEND IN GENERAL EDUCATION CLASSROOMS

1 IN 42

Public school students in the U.S. have 504 plans, which provide accommodations for kids with disabilities, but unlike IEPs, not specialized instruction

3X BOYS ARE THREE TIMES MORE LIKELY THAN GIRLS TO BE IDENTIFIED WITH A LEARNING DISABILITY

In an educational landscape focused on standardization, AoPS Academy thinks differently with its mission to discover, inspire, and train the great problem solvers of the next generation.

A DIFFERENT APPROACH

Our academic year and summer program offers math, language arts, and science for grades 1–12 that explore advanced ideas through creative activities—all taught through the lens of problem solving. AoPS Academy’s integrated approach develops critical thinking and problem-solving skills across disciplines, encouraging students to find multiple pathways to solutions rather than memorizing procedures.

EMBRACING NEURODIVERSITY

At AoPS Academy, thinking differently isn’t just accepted—

it’s celebrated. Students reach new academic heights when they collaborate with like-minded peers to innovate new approaches to every challenge.

North Dallas families can join small, in-person classes for focused, personalized attention at our Frisco campus. AoPS Academy also offers a Virtual Campus option available for families interested in different class times and options. Both formats maintain AoPS’s commitment to intellectual exploration and creative approaches.

OUR COMMUNITY OF PROBLEM SOLVERS

For families seeking a unique educational journey, AoPS Academy provides a haven—both physical and virtual— where tomorrow’s great problem solvers thrive.

At Hill School, we understand that learning is not onesize-fits-all. For students with ADHD, dyslexia, dysgraphia, high-functioning autism, and other learning differences, a traditional classroom environment can often feel overwhelming and limiting. That’s why for more than 50 years, Hill School has provided a transformative educational experience where students are not only supported—they are seen, valued, and celebrated for who they are.

We work in close partnership with families to nurture the whole child—academically, socially, and emotionally. Our specialized approach is built around each student’s unique strengths and challenges, helping them rediscover their confidence and build independence. With intentionally small class sizes, caring and experienced educators, and evidence-based teaching strategies, we deliver personalized instruction that meets students where they are and helps them grow beyond what they thought possible.

Hill School is proud to be an accredited partner with the Institute for Multi-Sensory Education (IMSE), providing

targeted reading intervention rooted in the Orton-Gillingham methodology. With a full-time, on-site Master-level instructor, students with reading challenges receive consistent, expert support that empowers them to succeed.

Our commitment to student growth extends far beyond academics. Hill School offers a well-rounded program that includes art, music, foreign language, theater, and athletics. These programs foster creativity, build collaboration, and encourage students to express themselves confidently in a variety of settings. Every student can explore their passions and discover new interests in a supportive, inclusive environment.

With rolling admissions, students can begin their journey when the time is right. Whether your child is just starting out or in need of a more understanding environment, Hill School offers a path forward. Come visit and see what’s possible when students with learning differences are seen, supported, and empowered to reach their full potential.

Jane Justin School provides state-of-the-art, evidencebased special education to children, adolescents and young adults with learning and developmental disabilities ages 5–21. Our mission is to foster the knowledge and life skills necessary for students to achieve productive and meaningful lives while respecting and embracing the individuality of each child. Jane Justin School is accredited by Cognia and has been designated a School of Excellence by the National Association of Special Education Teachers since 2022.

The faculty at Jane Justin School adopt a holistic approach to special education by providing custom learning plans to meet each student’s academic, social, and emotional needs. All faculty work from the perspective that learning is personal and instruction must be individualized. To meet our students’ needs, learning at Jane Justin School must extend beyond the traditional classroom. The Lower School offers music and art and an optional after-school enrichment program. Upper School students spend time in our mock apartment, school store, in the community, at work-sites with our community partners and in supported internships, preparing for independent adulthood.

Our commitment to evidence-based, individualized instruction results in meaningful outcomes for our students and their families. Despite facing significant barriers to learning, our students acquire skills at an accelerated rate, routinely demonstrating growth that outpaces time enrolled. Families consistently report high satisfaction for educational outcomes and value Jane Justin School for its family-like feel, welcoming culture and commitment to excellence. We are proud to be a beacon of hope for families whose children have been marginalized, under supported and underestimated. Jane Justin School sees strength, resiliency and promise in every single one of its students, and is committed to providing the effective special education they deserve so that they may meet their full potential.

Jane Justin School operates on a traditional school calendar and offers a six-week summer program. We know that finding the right school for children with disabilities can be overwhelming and frustrating. We invite you to give us a call so we may help you navigate this difficult road and help your child get on the path to meeting his or her full potential.

+ Small class sizes and student-to-teacher ratios

Key School and Training Center’s mission is to unleash student and teacher success through individualized instruction, training and advocacy. We serve students in grades K–12 with diagnosed learning differences, providing a nurturing, flexible environment with low student-to-teacher ratios that foster academic and social growth.

With over 55 years of success, Key School has helped hundreds of students discover their strengths through small class sizes, tailored instruction, and a curriculum designed to meet the needs of diverse learners. Fully accredited by COGNIA, we consistently increase academic achievement by focusing on each student’s unique learning profile.

Our campus in Fort Worth is home to more than 100 students and is designed with intention—creating an environment where learners thrive. Our educators go beyond traditional teaching, building personal relationships that support student success in both academics and life.

Key School specializes in academic language therapy. We follow a structured, multi-sensory approach to reading based on the Orton-Gillingham method. Students work one-on-one or in

small groups with Certified Academic Language Therapists who deliver personalized, evidence-based instruction.

Our keys to success are rooted in the legacy of our founder, Mary Ann Key. She developed the “Pillars of Key”—a unique academic foundation that includes Greek and Latin Roots, Classic Literature, Word of the Week and the Student Organizer System. These are exclusive to our school and reflect our commitment to deep learning and lasting skills.

Key School addresses the whole student—and the whole family. Student Advocates support emotional and academic needs, while after-school clubs build leadership and community. Our parent volunteer group, Key Community, fosters connection and raises awareness and funds for school initiatives.

We are more than a school. The Key Summer Program offers academic support for students in grades pre-K–12. Our Training Center equips educators to become Academic Language Therapists and supports parents with resources on learning differences. Since 1966, we’ve empowered thousands of learners and trained hundreds of educators across our region.

Could a tutor help your child with a learning disability? Sure. But sometimes it takes more than a tutor.

Pacioretty Academic Support Services began with this in mind. Founder Christine Pacioretty, a former teacher, academic interventionist, and 504 coordinator, knows the ins and outs of the system—and also that there’s a more effective way to help students excel. She combines her experience in education with her background in cognitive psychology and nutritional therapy to create a plan that focuses on the whole child. The model goes beyond tutoring and can include a full suite of tailored programs and resources designed to help all children thrive.

Support for specific learning disorders with Pacioretty Academics takes a holistic, integrated approach. Because every child is different, so is the plan to mitigate their academic challenges. It starts with the needed intervention, focusing on explicit instruction that helps students master foundational skills. This means personalized academic support, with customized instruction to work towards a child’s unique goals. It’s not onesize-fits-all; each child’s individual goals drive the lesson plans.

In a comprehensive manner, Pacioretty Academics looks at the entire student when it comes to their academic success. They connect families to practitioners specializing in nutrition, sleep, health and wellness to get the whole picture. If needed, additional supports are added to the plan to help the child meet their full potential. It’s a team approach.

It’s one thing to complete intervention for a specific learning disorder, it’s another to ensure it’s applied and transitioned to the classroom. The Pacioretty approach builds work-endurance and stamina. They help students develop study and classroom skills to become successful independent learners.

Parents need support too. Pacioretty Academics helps you learn the most effective ways to advocate for your child. Together, you will select the best school to fit your child and family, along with the accommodations that will support their immediate and long-term goals. You will work together to prepare for ARD meetings. Pacioretty Academics empowers parents with knowledge and understanding of their rights.

Academic interventions with a holistic approach for Grades PK–12.

Services tailored to your child’s needs: Dyslexia, Dyscalculia, Dysgraphia, SLDs in reading, math, and written expression, among others.

For more than six decades, Preston Hollow Presbyterian School (PHPS) has been at the forefront of educating children with learning differences in the Dallas area. Established in 1962, PHPS was the first school in Dallas designed specifically for students who learn differently—and that pioneering spirit continues as we prepare to open our brand-new, state-of-theart campus in fall 2025.

Our new home at 4000 McEwen Road, Dallas, TX 75244 marks an exciting new chapter in our school’s story. We are currently accepting inquiries for students entering grades K–5 for the 2025–2026 academic year

PHPS is dedicated to supporting students of average to superior intelligence who face mild to moderate learning differences, including dyslexia, auditory processing disorders, oral and written language challenges, and math-related disabilities. What sets us apart is our commitment to offering a highly personalized, nurturing educational environment tailored to each child’s unique learning profile.

Our mission is to help students thrive academically, personally, socially, and spiritually. By equipping them with confidence and effective learning strategies, we prepare our students for successful transitions back into mainstream educational settings.

With small class sizes, individualized instruction is at the heart of everything we do. Each class benefits from the support of trained remedial specialists and teaching assistants. Our multisensory, research-based curriculum is enriched by classes in physical education, music, art, technology and weekly chapel while students in kindergarten and first grade also attend a fine-motor lab.

As we look ahead to our new campus, our dedicated faculty and staff are thoughtfully designing a space that enhances learning and fosters growth—ensuring that every student feels supported, inspired, and ready to reach their full potential.