Interviews

Rules of the Game for a New Era

To address the resource crisis, building regulations and economic models must undergo fundamental change. British architect and social entrepreneur Indy Johar, co-founder of Dark Matter Labs, describes the dimensions of this transformation. The international nonprofit advises governments, public bodies, and private companies on redefining society’s institutional infrastructure. In this interview with Jakob Schoof, Johar explains what this means in practice.

Your work with Dark Matter Labs is about legislation and ownership, resource flows, and our relationship with nature. What motivates you to deal with such fundamental issues?

As an architect, I used to work on open source projects such as WikiHouse, co-founded an open source furniture company and was involved in the founding of impact hubs and other social enterprises. It was all about architecture with an entrepreneurial background – on my own initiative, not as a service for a client. I quickly learnt one thing: form follows capital. The design of architecture follows the availability of capital and the structure of contractual relationships. If architecture is to meet the challenges of the resource crisis, such contracts, rules, and organisational structures must be changed. A second aspect that became clear to me was the linear way of thinking that underlies such structures. They assume framework conditions that will remain unchanged for years. Yet we know how volatile our future will be and that we are facing a temperature rise of 3, 5, and, in some places, 8 °C in cities.

What does this mean in concrete terms?

In most European countries, there are plans to build large quantities of new housing. However, we no longer have the necessary CO2 budget available for this. The World Resources Institute has calculated that greater use of wood in construc-

Indy Johar

tion would increase our CO2 emissions for decades to come.1 As long as we use wood as inefficiently as we currently do, the climate balance is in many cases worse than with steel or concrete. Of course, this does not mean that we should continue to build with concrete, but that both solutions are unacceptable. Ultimately, three things are necessary: Firstly, a moratorium on new buildings. Secondly, our ideas of comfort will have to change radically. And thirdly, we need a bio-regional economy that focuses on retrofitting buildings instead of building new ones. This will almost certainly centre on lightweight constructions that are easily recyclable and consist to a high degree of recycled materials. The purpose of our buildings will also change – from dedicated residential, office, or hotel buildings to structures that can, in principle, be all three.

You work with local groups but also with the European Union. This suggests that building bio-regional economic structures requires cooperation across many different political levels.

That’s right. And you have to look at several systems at once: For a bio-based, regional supply of resources, our food supply must also change – towards a plant-based diet in order to be able to utilise agricultural land for other purposes than growing animal feed. Agroforestry will also play an important role in this. All of this requires changes to European legislation. At the moment, the free European market does not allow regional supply chains to be favoured.

Is a moratorium on new construction realistic? After all, the building stock is not always located where people want to live.

In Europe, 33 % of all buildings are underutilised. That is a huge amount of embodied emissions that we are making far too little of. What’s more, per capita space requirements have

“We no longer have the necessary CO2 budget available to build large quantities of new housing.”

been rising for decades. I think we need to significantly improve the quality of our buildings without taking up more and more space. And we need to talk about investing in shared infrastructure. If there were a coworking space and a communal kitchen on every ground floor, we would need fewer studies and kitchens in the flats. This could free up space for intergenerational living, for example. After all, demographic change and the question of how we organise care in the future are among the greatest challenges of our time. All of this raises an interesting moral question for me, that of spatial justice. Is it okay to leave buildings empty? Is it okay to privatise resources instead of using them for the common good? In recent years, many people have made more money from their house than from their work simply because it was in the right location. If I take your house and move it to Siberia, what is it worth? Nothing! The increase in value of these houses only results from their proximity to public goods – roads, cultural facilities, and other infrastructure that the general public has paid for.

So it’s a question of ownership. What alternatives are there to the status quo?

One very far-reaching vision is self-owned buildings that can make decisions for themselves. This may sound like science fiction, but it is possible with artificial intelligence. And these self-made decisions would then determine how the building is used and how it changes over time. Other things could already be realised today, such as partial commons. You could retain ownership of your house but make the roof area available to the general public to generate solar energy, for example. Digital technologies allow us to segment property rights in this way. Another model is solidarity-based community land trusts, which hold land in their possession and allocate it to users on a leasehold basis. On a philosophical level, I am interested in property because it creates synthetic divisibility: you draw a boundary around something and then it is your prop-

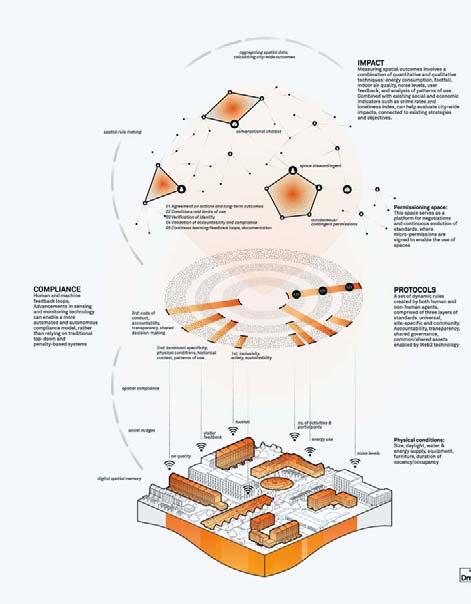

In the project Re:Permissioning the City, Dark Matter Labs explores how vacant and underutilised urban spaces can be aggregated and made accessible for future civic uses.

The City as Forest

Interview

Sou Fujimoto

Sou Fujimoto’s Grand Ring for Expo 2025 in Osaka aims to revitalise timber construction in Japan. After the event, the structure will be repurposed for residential buildings and schools. He discusses the project with Frank Kaltenbach.

The Expo and its main structure opened this April in Osaka. According to the Guinness World Records, it is the largest timber structure in the world. When you gained international recognition in 2006 for your Final Wooden House, did you envision working at such an urban scale?

I could never have imagined something like this. I prefer to be surprised by success. I didn’t even expect to win the Expo masterplan before I was appointed as its lead planner. But of course, it is immensely exciting to work across such a wide range of scales.

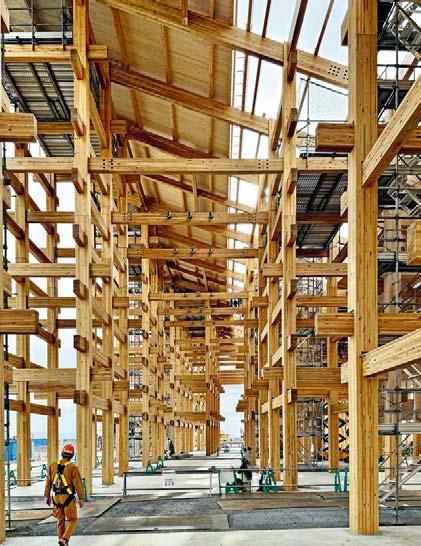

The Expo’s central structure rises between 12 and 20 m in height, spans 60 000 m2, and forms a 30 m wide ring topped with a grass roof. With a diameter of nearly 700 m, it encloses all of the national pavilions.

The building’s appeal lies in this extraordinary size, but at the same time, its 3.60 m grid corresponds to the human scale. So it is not about monumentality for its own sake, but rather about the compelling coexistence of the human scale and the large scale. From the air, it appears abstract and distant. It is only from the perspective of a person walking through the space that the subtle variations in form can be felt: gentle expansions and narrowings, pathways that gently rise and fall, which create a surprisingly dynamic spatial experience.

Why take the risk of building such a large structure in timber, even though Japan currently has no established timber construction industry?

Sou

Fujimoto

The Great Ring embodies both symbolic power and practical sustainability. After the Expo, its timber can be dismantled and repurposed in various configurations for future projects.

Working in Europe, North America, and Australia, I’ve seen how rapidly timber construction has progressed. Despite this international move towards more sustainable building, Japan has stagnated in this respect. The Grand Ring not only reflects the Expo’s theme, “Unity in Diversity”, but also aims to set a strong example for timber construction as best practice. 70 % of the timber – Japanese cedar and cypress – is sourced from domestic forests. The remaining third is imported Scotch pine.

You are going a step further: after the Expo, this massive structure will be repurposed as individual buidings across Japan.

Our aim is to lower the threshold for adopting timber construction. To this end, we’re offering a fully developed modular system. The timber ring is not only a symbol, but also a vast material resource. The structure is designed to be dismantled after the Expo and reassembled in variously sized segments at other locations. Its regular 3.60 m grid is not only well suited for multistorey housing but also offices, schools, and other types of public infrastructure.

Are the timber joints easy to dismantle? The large timber roof at Expo 2000 in Hanover was bolted together with heavy steel nodes.

Traditional Japanese nuki joints are neither glued nor screwed. This allows the joints to remain elastic and stable during earthquakes. The joints used in the Grand Ring are based on this age-old technique – they are simply slotted together and can be easily dismantled and reassembled. Rather than a roof, this Expo structure is a ring, which carries strong symbolic meaning. A key source of inspiration was the Expo roof designed by Kenzo Tange for the 1970 World’s Fair in Osaka: a giant steel disc-shaped truss with a central void, framing Taro Okamoto’s Tower of the Sun. That circular cut-out, framing the sky

Sou

Fujimoto

and cloud like a picture, has always fascinated me. In Japanese aesthetics, the ultimate reality is found in emptiness. We even have a word for this concept of nothingness: ku.

Expo 70 was perhaps the most visionary architectural showcase ever, embodying an incredible wave of creative energy sparked by the euphoria of the moon landing. Have we lost that enthusiasm for the future?

National moods are always subject to fluctuations. After the excitement surrounding Expo 70 came the oil crisis. Japan recovered, only to face another downturn when the economic bubble burst. Just like in the early 1970s, we again face another turning point. The entire world must change course and work together to address climate change. That gives me reason to be enthusiastic again today, despite all the crises. The transformation we urgently need carries immense creative potential for everyone involved in design. I believe we can look to the future with optimism – not blind optimism, but one grounded in critical reflection. As architects, we can help channel that mindset through our work.

Compared with your other projects, the Grand Ring feels almost restrained.

This structure was never intended to draw all the attention to itself. Quite the opposite – it serves as a calm backdrop for the eye-catching national and thematic pavilions and for the colourful, energetic flow of visitors from around the world. Here, too, it’s about the playful discovery of different experiences.

What architectural guidelines did you set for the national pavilions?

We strongly encouraged the use of natural or recycled materials, and emphasised reuse. While many countries chose to

Traditional Japanese nuki joinery uses no screws or glue, keeping structures elastic and stable during earthquakes.

Sou Fujimoto

Less Techno logy, More Architec ture

Interview

Elisabeth Endres

For Elisabeth Endres, climate-friendly construction means treating architecture and building technology as a unified whole. In conversation with Frank Kaltenbach, she explores the question: How little technology is enough?

In 2020, you were named the head of the Institute for Building and Solar Technology at the Technical University of Braunschweig. The first thing you did was change its name – why?

The new name, Institute for Building Climatology and Energy Architecture, shows the need to think broadly about sustainability in terms of building physics, building services, and energy, also in teaching. My background is in architecture, not mechanical or power engineering. Solar technology is vital for the future; in energy production, everything will come down to electricity, and combustion systems will be reduced to a minimum. But for me, the question does not start with building or solar technology; it is about much more, namely building culture and how we will live. My teaching and research cover three areas: design and the necessary technical equipment, materials and the grey energy bound in them, and energy generation and storage. The focus is on the challenge of creating robust and comfortable buildings with as little technical effort as possible that are as sustainable as possible; they should be highly durable, not only in their operation but also in their construction and end of life. The building itself, with its materiality, room layout, and structural details, must become the focus of energy and climate planning. The performance of architecture and its local context must be addressed, followed by a discussion of the comfort requirements, and then the technical systems. We need to think in terms of networks –from energy generation to buildings to mobility. If I don’t have to build parking spaces in underground garages, I save a lot of concrete and, with it, CO2 emissions.

Elisabeth Endres

Where do you encounter resistance?

The fee for building services planning is based on a percentage of the amount invested in the technical systems; this needs to be replaced by a fee schedule. At the same time, there need to be incentives for holistic concepts and planning that reward interdisciplinary processes. We once received a bonus for being well below the targeted budget for the cost group 400 (building services systems according to German DIN 276), thanks to our intensive, positive work with the architects. This is money well spent, with no maintenance costs.

What legislative changes are needed?

We need a new building energy code. So far, the government has measured billions of euros in subsidies according to the theoretical energy use of low-energy houses in kilowatts per square metre (kWh/m2a). How about a person-related unit, such as tons of CO2 emissions (t CO2) per capita? That would make the materiality and measures more important, and users would also be held responsible. Large villas with only two residents would not count the same as dense urban spaces. On the other hand, low-cost, densely occupied multistorey apartment buildings could be built without a lot of technology and excessively thick insulation. In essence, goals would have to be defined instead of measures.

Aren’t the existing certification labels enough, such as DGNB, Leed, and Breeam?

I think the added value of these systems is not the certifying but the monitoring of the process. I doubt whether a true, comparable assessment of sustainability is even possible. In the past, sustainability strategies have been strongly driven by the idea of efficiency and relied heavily on energy requirements. This does not only concern certifications. In practice, when users

With minimal technological intervention, gmp Architekten and IB Hausladen transformed an old industrial hall into the foyer of the Isar Philharmonic in Munich.

Elisabeth Endres

constantly leave the windows open for ventilation, consumption skyrockets. So it is much more realistic not to define absolute, optimal parameters but to require the values to lie within a specified range. In high-tech buildings, if the systems fail, the buildings don’t function at all. On the other hand, simple, low-tech buildings with a high thermal storage mass are less vulnerable. Robust and resilient construction must replace the smart home. With my team at Ingenieurbüro IB Hausladen, I am currently developing ClimaDesign concepts for high-tech buildings with double facades and full glazing. Even in buildings like that, you can use less technology and plan for possible upgrades should problems really arise. But the focus should also be on sustainably renovating highrises.

Your department at TU Braunschweig has its spaces in one of those run-down postwar highrises…

It’s not the reinforced concrete structure that is run-down but only the facade and the interior; that does not mean the building itself is bad. In terms of building climate, the decades-long use of suspended plasterboard ceilings makes no sense – it minimises room height and reduces the thermal storage capacity of solid ceilings, especially when exterior sun protection is impossible. We gutted the interior and turned the entire floor into a living laboratory. Three strategically placed wooden stud walls are covered with clay panels, where we have different capillary tube systems for room temperature control. In combination with a heat pump, solar power is enough to cover our peak loads in winter and summer. To facilitate this process, the floor plan is organised so that we do not have to heat the whole space in winter. Clay plaster provides additional thermal storage mass and acts as a humidity buffer. We also used similar techniques in a historic preservation project: for the industrial building designed by Egon Eiermann in Apolda in the 1930s, our practice developed a room-in-room concept together with the International Building Exhibition (IBA)

“We have to move away entirely from the notion of efficiency. I don’t think you can certify sustainability in any meaningful way.”

Elisabeth Endres

Conversation Partners

Imprint

Editor

Dr. Sandra Hofmeister

Interviewers

Florian Heilmeyer, Claudia Hildner, Sandra Hofmeister, Frank Kaltenbach, Julia Liese, Peter Popp, Jakob Schoof, Heide Wessely, Barbara Zettel

Project Management

Sandra Hofmeister, Anne Schäfer-Hörr

Editorial Assistance

Laura Traub

Translations

Alisa Kotmair, Mark Kammerbauer

Copyediting

Alisa Kotmair

Design

Claudia Scheer, Manuel Federl (Berlin, DE)

→ muskat.design

DTP

Simone Soesters

Reproduction

ludwig:media (Zell am See, AT)

→ ludwigmedia.at

Printing and Binding

Gutenberg Beuys Feindruckerei (Langenhagen, DE)

→ feindruckerei.de

Paper

Cover

Chromosulfatkarton 280 g

Content

Munken Print White 100 g

This book has been made from materials that originate from responsibly managed, FSC®-certified forests and other verified sustainable sources.

© 2025, 1st edition

Detail Architecture GmbH (Munich, DE)

→ books@detail.de

→ detail.de

ISBN:

978-3-95553-668-8 (Print)

978-3-95553-669-5 (E-Book)