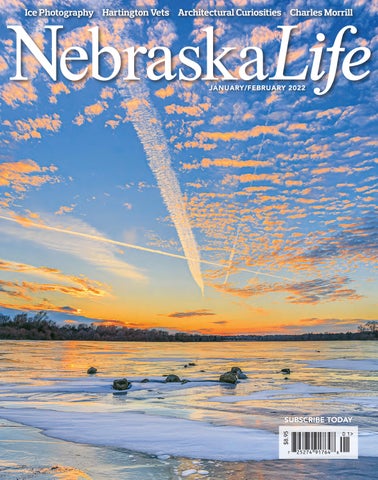

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2022

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2022

One of the greatest North American wildlife experiences lands here in Grand Island. Watch thousands of sandhill cranes parachute onto the river in the evening, hear them trumpet as they wake to a crisp March sunrise. Moments like these make life grand. Visit SeeTheCranes.com.

20 South Omaha Mural Project

Artists and community members work together to depict the rich history and culture of this thriving neighborhood. Large-scale works unite the diverse community as one big family.

Story by Megan Feeney

24 Ice Photo Essay

Photographers from across Nebraska contribute their coolest shots to this photo essay that reflects on our state’s natural wonders and the lessons we can learn.

32 Har tington Veterinarians

Erin and Ben Schroeder treat injured and sick animals, renovate historic buildings and star in a National Geographic Wild reality show that broadcasts the town of Hartington into homes around the world. And what a town it is.

Story by Megan Feeney Photographs by Brooke Steffen-Kleinschmit

50 Charles Henry Morrill

Morrill Hall: University of Nebraska State Museum has many natural history wonders thanks to the man whose love for archaeology and commitment to fund digs in Nebraska kept them here.

Story by Tim Trudell

58 13 Architectural Curiosities

Nebraskans have built structures to protect and provide for their people, honor their history and elevate beauty in their communities – and they’ve used creative methods to get it done.

Story by Megan Feeney

76 Winter Reading

Cozy up with new books featuring Nebraska connections, including a thriller set in the Sandhills, a collection of medical nonfiction mysteries by an Omaha doctor and new poetry from Ted Kooser and Marjorie Saiser.

Story by Megan Feeney

Columbus Community Hospital’s surgical services unit is proud to announce the arrival of a new da Vinci® Xi™ robotic system to provide a wide variety of minimally invasive surgeries, including the following:

• Inguinal hernia repair.

• Umbilical hernia repair.

• Ventral/incisional hernia repair.

• Cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal).

• Appendectomy.

• Colon resection.

• Nissan fundoplication (stomach surgery for reflux).

• Hysterectomy.

This special piece of technology gives surgeons greater capabilities in the operating room and provides a minimally invasive surgery option for patients.

The da Vinci® Xi™ robotic system features 3D imaging of the surgical area with enhanced dexterity for greater precision by surgeons.

For more information on the new da Vinci® Xi™ robotic system, visit www.columbushosp.org.

• Oophorectomy (ovaries).

• Tubal ligation.

• Bladder repair/suspension.

• Prostatectomy.

• Nephrectomy (kidneys).

• Bladder surgery.

Cody pg. 58

Valentine pg. 70

Crawford pg. 50

Harrison pg. 50

Minatare pg. 58

Morrill pg. 50

Morrill County pg. 50

Arthur pg. 58

Madrid pg. 15

McCook pg. 58

9 Editor’s Letter

Gothenburg pg. 58

Kearney pg. 58

Eustis pg. 24

Hartington pg. 32

Norfolk pg. 18

Central City pg. 64

Grand Island pg. 58

Aurora pg. 24

Johnson Lake pg. 58

South Sioux City pg. 58

Meadow Grove pg. 24

Marquette pg. 24

Osceola pg. 50

Seward pg. 58

Lincoln pg. 58, 70

Stromsburg pg. 50

York pg. 16

Blair pg. 24

Omaha pg. 13, 20, 24, 70

Linoma Beach pg. 58

Louisville pg. 24

Nebraska City pg. 12

Observations on the ‘Good Life’ by new editor Megan Feeney.

10 Mailbox

Letters, emails, posts and notes from our readers.

12 Flat Water News & Trivia

Nebraska City dog trainer coaches people and pups in dog agility, family-owned store serves fresh roasted coffee and melt-in-your-mouth pie in Madrid, Joslyn exhibit highlights Nebraska’s Indigenous communities and a vending machine in York sells dry-aged beef 24-7. Test your knowledge about Norfolk’s festivals, famous folks and food. Answers on page 75.

42 Kitchens

Whether you’re on team cinnamon roll or team cornbread, chili combined with an oven-baked treat warms up winter days. We’ll take one of each, please.

46 Poetry

Poets revel in the beauty of a frozen Nebraska landscape.

70 Traveler

A recovered population of Nebraska river otters await wildlife watchers, an annual Reuben competition in Omaha’s Blackstone District promises diners beefy bites and a Lincoln cidery invites imbibers to quaff a flight of appley alcoholic nectars.

80 Naturally Nebraska

A new column from former Nebraska Life editor Alan J. Bartels.

82 Last Look

Fourth-generation Seward farmer reaps rewards of early rising with shot of fuchsia sky.

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2022

Volume 26, Number 1

Publisher & Executive Editor

Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher Angela Amundson

Editor Megan Feeney

Photo Editor Joshua Hardin

Design

Traci Laurie, Open Look Creative Team

Advertising Marilyn Koponen, Lauren Warring

Subscriptions

Lindsey Schaecher, Janice Sudbeck, Azelan Amundson, Teresa Eichenbrenner

Trivia Master

Alex Fernando

Nebraska Life Magazine

c/o Subscriptions Dept. • PO Box 430 Timnath, CO 80547 1-800-777-6159 NebraskaLife.com

SUBSCRIBE

Subscriptions are 1-yr (6 issues) for $25 or 2-yrs (12 issues) for $44. Please call, visit NebraskaLife.com or return a subscription card from this issue. For fundraising and corporate rates, call or email subscriptions@ nebraskalife.com.

ADVERTISE

Advertising deadlines are three months prior to publication dates. For rates and position availability, please call or email advertising@nebraskalife.com.

CONTRIBUTE

Send us your letters, stories, photos and story tips by writing to us, visiting NebraskaLife.com/contribute or emailing editor@nebraskalife.com.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork are copyright 2022 by Flagship Publishing Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@nebraskalife.com.

MEMBER OF

International Regional Magazine Association

AS A NEW member of the Nebraska Life team, I recently enjoyed lunch in the charming town of Hartington with Nebraska Life colleague Janice Sudbeck, who’s worked in subscriptions for 18 years.

Janice regaled me with tales of Nebraska Life’s history as we enjoyed steak sandwiches and split a piece of banana caramel cake at The Globe Chophouse.

The Globe building is a touchstone for the community, Janice said. For many years it was Globe Clothing. Nearly everyone she knew had shopped there – and their parents and grandparents had too.

Globe Chophouse owner Kate Lammers knows the building is part of a bigger story. It’s one of the reasons she feels an obligation to make her business work. Kate isn’t from Hartington – her dad was Air Force, so she grew up in a lot of places, including Omaha – but she recognized the opportunity in that Nebraska town. It was a good place to raise her young children and start a business.

I grew up in Omaha but, like Kate, I’ve lived many places, among them China and New York City, where I worked as a journalist and editor. In 2015, my husband Adam and I traded our one-bedroom Brooklyn apartment for an acreage in Cass County, not far from my folks’ vegetable operation, Paradise in Progress Farm. Farming is Mom and Dad’s second act after raising my four brothers and me. During our years in New York, Adam and I loved visiting and working in the dirt. We saw how happy our firstborn son was walking the beans. We wanted that life.

Today our eldest son and his younger Nebraska-born brother roam our eight acres climbing trees, playing with their goats, dogs, cats, ducks and chickens and finding all kinds of bugs, snakeskins and leaves to put into their pockets. Our garden is bigger than our Brooklyn apartment was. My parents have taught us how to care for the land – how to enrich the soil and prevent erosion.

As Kate is a steward of her historical building in Hartington, I consider myself a steward of this piece of earth in Union and recognize that it’s also part of a bigger story.

I feel the same way about the responsibility publishers Chris and Angela Amundson have entrusted to me. Nebraska Life turns 25 years old this year. With the support of talented long-time employees like Janice, it’s been a source of fun, joy and inspiration for readers near and far who love our great state.

I’m delighted to play my part in Nebraska Life’s ongoing story. As Kate does with her restaurant building and as my family does with their land, I will honor the magazine’s past as we all move forward together.

Megan Feeney Editor editor@nebraskalife.com

Your story about the greenhouse was interesting (“Citrus in the Snow,” November/December 2021). I think we will have to get more innovative with how we grow our food. How cool is it that someone in Nebraska figured out this solution? Many pollinators are struggling to survive. Good to know we can pollinate our own crops if we have to. It would be good to have a list of the other facilities’ locations. Do any of them offer tours? I would want to visit the one near my home in Nebraska City.

Ann O’Fallon Nebraska City

Editor’s note: You can see a virtual tour of the original greenhouse at greenhouseinthesnow.com. Contact Russ Finch in Alliance at (308) 760-9718 for more information about onsite visits.

Alan’s wild ride

reignited in the organic movement.

My parents talked often about the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression in reminders to be grateful for what we had.

Jeanette Hopkins Sioux City, Iowa

Thanks for the mention of Mom and Dad in your editor letter, (“New beginnings,” November/December 2021).

Mom immediately called me when she read it to tell me about it – it was a great memory of you bouncing to a stop with a crazy pilot. Dad always fancied himself a wannabe pilot (I think the covered wagon to flying machine transition was the appeal). He never did learn how but they both were very excited when you arrived.

Kevin Howard Sidney

Your mention of the 1930s in “The Decade that could have been” (Flat Water News, November/December 2021) made me think of my grandparents.

The ’30s were difficult, but my grandad utilized conservation practices to survive. He graduated from the University of Nebraska and taught conservation at Columbia University before returning to the family farm in Nebraska in the ’20s.

He used terracing, wind breaks, buffalo tilling and waterways to save the topsoil and the farm. Those conservation practices continue to this day and are being

I was born in 1930. I remember the Dirty Thirties, because I made many mud pies, and I never was reprimanded for digging holes in the yard because there was no grass to destroy. We worked in the state of Nebraska during our years of employment. I will always remember the walking trail on Scotts Bluff Monument as a great stress reliever

Norman Frerichs Genoa

We currently have a house guest named Loralye (Jensen) Sorum who grew up in Obert. I shared your article about Wynot with her (“Why Not get creative when naming your town?” Flat Water News, November/December 2021), which gave her a big chuckle. She told us that as kids growing up, they would say “Wynot go Obert to Maskel to see our Newcastle.”

Someone once said that kids say the darnedest things.

Lyle Tuttle Surprise, Arizona

When I saw there was an article about Bess Streeter Aldrich (“Best-selling Bess”) in the November/December 2021 issue, I stopped what I was doing and read it all. She is my all-time favorite author. I highly recommend all her books. There’s a sweetness to them that is just so special, and really reminds me so much of our beautiful state back when it was being settled. (Not that I was there then!)

I hope this magazine article inspires many people to read her books.

Julie Joyce Fremont

I am very pleased that you included my poem, “In Nebraska” in the September/ October 2021 magazine. It was particularly pleasing to be among poets Lukas, Heath, Vesely and Franzen, whose images create a warm nostalgia for things Nebraska.

Having worked in the Capitol (when I was young) first in the Office of the Attorney General and later for the chief justice of the Nebraska Supreme Court, I especially related to Franzen’s scenes of Lincoln viewed from the tower of the Capitol. Every time I entered that remarkable edifice, it seemed as if all the marble and mosaics epitomized the strong and ever-loyal characteristics of Nebraskans.

Beth Franz Lincoln

Thank you for your wonderful story about DeGroot’s Orchard (“Detour to DeGroot’s,” September/October 2021). As a former Nebraskan from Madison, I remember driving from the Barr’s home to Norfolk.

My mom and dad both worked for Cindy’s mom and dad. I never got to know Cindy, as I was gone from home when she was born. Both my sons know Cindy from Madison High School. I wonder if Cindy remembers my mom and dad and how much she meant to them. Bless her and all her family for always.

Marian Little Port Angeles, Washington

I love Nebraska and have given away three gift subscriptions so far. Friends report several trips within the state have started with the reading of an article or sight of an advertisement. My own subscription continues until 2023.

Nicolle French Bailey Broken Bow

Thank you for another wonderful year of Nebraska Life. For a number of years, Nebraska Life has been a Christmas gift for my wife, Jeanie. We just celebrated 44 years together. She never fails to let me know that Nebraska Life is the gift she cherishes most.

Tom Hughes Tilden

Editor’s note: Thanks for your support of Nebraska Life. We agree – subscriptions make great gifts for friends and family. Visit nebraskalife.com or call us at 1-800-777-6159.

Perusing Nebraska Life , there it was, a story about wolves (“Wolves rejoin Nebraska’s wild kingdom,” Flat Water News, September/October 2021). Immediately, I had a three-year flashback of the photo of our granddaughter in a wire enclosure with a wolf.

In college, Alyssa’s major was ecology, and she had a summer job at a Wolf Reserve in northern Indiana. The pictured wolf had always been domesticated and regularly cared for by staff members. Alyssa’s job description included a gentle approach and letting the wolf approach her.

The wolf did just that and she responded with kind attention. However, strict rules were in place, like making slow, cautious and deliberate movements, avoiding noise and using consistent and calm actions. Though the wolf appears tame, they still have a wild and vicious trait of nature which could be alarmed and become active.

As the article said, the Nebraska ranchers are starting to see a few wolves after an absence exceeding 100 years. By DNA, one carcass was traced back to the Great Lakes region.

Therefore, my unexpected and memorable flashback was verified by connecting two stories.

Lowell Broberg Puyallup, Washington

Please send us your letters and emails by Feb. 1, 2022, for possible publication in the March/April 2022 issue. One lucky winner selected at random will receive a free 1-year subscription renewal. This issue’s winner is Tom Hughes of Tilden. Email editor@nebraskalife.com or write by mail to the address at the front of this magazine. Thanks for reading and subscribing!

BY MEGAN FEENEY

Snickers had a bad case of the zoomies.

Churning four little legs, the young corgi circled dog agility instructor Tammie Gigstad’s Nebraska City barn. Snickers jumped random obstacles. She wiggled her fluffy butt and barked. She somersaulted and, once right side again, kept running. Snicker’s owner, 10-year-old Cosette Wagner, pursued her pup, but the dog added speed. The duo’s panting

streaked the air. Radiant diesel heaters blasted, but the cold January evening winds seeped through the barn’s cracks.

“You’ve got to be more interesting, Cosette,” shouted Gigstad, cupping her gloved hands to her face. Gigstad believed the novice young handler showed promise in dog agility, but even more advanced students needed coaching. The girl had to do something to recapture her young dog’s attention. Cosette ran in the opposite direction with a tug toy and made

gleeful 10-year-old kid sounds. It worked. Dog returned to handler.

After putting an end to Snicker’s shenanigans, one of Gigstad’s weekly dog agility classes was once again underway. Agility requires a handler to direct a dog through a series of obstacles in the correct order within a set time. There are jumps

Tammie Gigstad and her poodle Maui take a break from agility training at their home in Nebraska City.

and tunnels, weaves and teeter-totters, dog walks and a-frames. Gigstad is an accomplished handler. She has placed at national events and competed internationally. Most recently last fall, she and her silver miniature poodle Maui beat a slew of border collies in a national weave pole contest at the Purina ProPlan Incredible Dog Challenge in St. Louis.

Gigstad’s students – humans and their canine companions – come from nearby Nebraska counties, as well as Iowa and Missouri. Cosette Wagner is one of the youngest students; the oldest are in their 70s. Dog agility has become popular in Nebraska in recent years, with an increasing number of people participating in the sport and local clubs hosting more agility trials. Nebraskans used to have to travel to other states to compete, but now enthusiasts can find as many as three in-state trials in three weeks.

Gigstad witnessed the growing Nebraska interest in the sport and wanted to provide a local year-round space for people to learn and enjoy it. She convinced her husband Jimm, a veterinarian in Nebraska City, that if she had a place to teach throughout the year, she’d make it a success. The couple built the barn to hold her classes a little more than a decade ago. She advertised on social media, and classes grew

Gigstad said her greatest hope for her students is to know the joy and connection with a dog that she’s felt with her dogs over the course of her two decades with the sport.

It’s been a year since that January night when the corgi Snickers lost her little doggy mind. She’s come a long way since then. Cosette Wagner competed in her first AKC agility show last fall - and Snickers stayed with her the entire time. Cosette’s mom, Leslie Wagner, who also takes classes with Gigstad and competes with the family’s other dog, a blue heeler named Emily, appreciates being able to share the experience with her daughter. They’ve both found community and friendship through classes and competition. Leslie said Cosette has learned a good life lesson, too. School has always been easy for her daughter.

“But with a dog you have to put the work in,” Leslie said.

1833 and 1834.*

BY MEGAN FEENEY

A young Native American boy stared into the distance with soft brown eyes. His body was round and well-nourished. He wore a metal bracelet on his wrist. The eagle feather in his hair, his earrings and paint reflected his family’s status.

“Omaha Boy,” is one of more than 60 recently restored watercolors in Joslyn’s Faces from the Interior: The North American Portraits of Karl Bodmer.

Wynema Morris, an Omaha Tribe Member and adjunct professor at Nebraska Indian Community College, provided text to accompany the painting of the Omaha youth.

Artist Karl Bodmer was a Swiss draftsman employed on an expedition to document the people and nature along the Missouri River. He and his benefactor Prince Maximilian of Wied traveled 2,500

miles by steam and keelboat between 1833 and 1834.

Bodmer’s work provides rare pictorial documentation of people from Omaha, Ponca, Yankton, Lakota, Mandan, Hidatsa, Assiniboine, and Blackfeet tribes in the early 19th century.

The Joslyn exhibition relied on Indigenous artists, knowledge bearers and scholars, like Morris, to contribute text.

Four short films also premiere at the exhibit providing insight into the traditions of beadwork and dancing and illuminating the rich heritage of tribal histories, ecological knowledge and language.

In one of the films, Morris explains that Bodmer’s work becomes a jumping off point to talk about the culture at a certain period in history.

The exhibition is on display until May. A catalogue of paintings is available on the website Joslyn.org.

* Karl Bodmer (Swiss, 1809–1893), Interior of a Mandan Earth Lodge, 1833–34, watercolor and graphite on paper, 11 7/16 in. × 17 in., Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, Gift of the Enron Art Foundation, 1986.49.261.A.

June 2

13 Day WWII Tour, Visiting France, Belgium and Germany

Always a sell out... call today! (Includes airfare from Minneapolis $3,795 or Chicago $3,695)

July 23

Exclusive Norway!

From Oslo to Bergen on land then a six day cruise along the coast of Norway. Call for pricing. Deadline for cruise is March 1, 2022.

August 20

England, Scotland, Wales & Ireland

Includes the Military Tattoo in Edinburgh. Land package $3,895 and air from Chicago $866 or Sioux Falls $1,313. Already 55% sold!

September 24

Unbelievable Europe – A Two Part Tour

Part One: Includes Oktoberfest in Munich, world-famous Passion Play in Oberammergau (deadline for tickets is May 1st), then visits Switzerland, French Alps and Monaco.

Part Two: Tour continues into Spain and Portugal Already 40% sold! Do part one, two or both!

BY SAVANNAH REDL

Four hungry college boys ambled into Sharon Zimmerman’s Madrid General Store in Perkins County looking for pie. The guys, who were traveling across Nebraska on a pie-tasting quest, had reserved it a week in advance and driven hours to get there.

Zimmerman had forgotten all about the special order. Her in-demand pies often sold out. But within an hour, she served the young men a hot juicy blueberry pie – and made sure they had plenty of coffee and ice cream to go with it.

Zimmerman’s Mennonite family has offered this kind of hospitality to customers and curated the store’s offerings to meet the needs of the community.

Madrid, pronounced MAD-drid, is in southwest Nebraska, not far from the Colorado border, just off highway 23. The Zimmermans moved to Nebraska from

Wisconsin in 1996 and established their Madrid store in 2011.

Sharon Zimmerman’s scratch-made breads, pies and pastries from family recipes weren’t originally on the menu. She realized early on that she needed something extra to get folks in the door. Now, on baking days, there’s sometimes a line out the door.

Baking spices fragrance the air, mingling with the smell of coffee roasted on-site. Neatly lined shelves with brown parceled goods create a feeling of tranquility and order. The store offers everything from produce grown by Zimmerman’s son to educational toys, from home goods to local beef. The wooden framed store features hanging baskets and flower boxes in front

Zimmerman built her business with community support, and she has extended her support to other local entrepreneurs and makers. She sells tea towels made by Marcia Spratt from Grant. The honey she

carries comes from Doug Long’s Family Honey Farm in Lexington. The coffee beans are roasted by local coffee entrepreneur Jason Regier. Zimmerman gave up her own office at the store for him.

Sometime after that emergency blueberry pie bake for the college boys, one of them called to thank her again and ask her for the recipe.

The young man said that on their pie tour of Nebraska, it was one of the best.

BY MEGAN FEENEY

In the dead of night, Brian Kurth’s cell phone pinged. A camera sensor at McLean Beef set it off.

Someone had entered the York-area fresh meat market and processing facility at 3:30 a.m.

Kurth, McLean Beef’s general manager, wasn’t worried. He knew cravings for dryaged beef struck at all hours.

Two carousel-style vending machines sell steaks 24-7 in the vestibule.

Glass doors lead into the main market area, open from 8:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.

Handmade prints decorate the black brick walls. Marbled cuts of corn-fed USDA-inspected Nebraska beef gleam behind the

butcher case. A self-serve display below offers grab-and-go items, as does a nearby freezer section. Sitting around round tables, customers tuck into lunch offered on Wednesdays or breakfast served on Tuesdays and Thursdays mornings cooked in the onsite commercial kitchen.

The McLean family has been in the Nebraska cattle business for four generations and maintains 9,000 head near Benedict in York County. Patriarch Max McLean wanted a store where people could walk in, see fresh meat and hand it over to be cut the way they liked it. He brought on Kurth to help realize his vision. Kurth found a building in foreclosure that once housed a firetruck and ambulance builder three quarters of a mile from the 80 Interchange

Customers at McLean Beef near York can choose between shopping the main market or giving the vending machines in the vestibule a whirl.

off Highway 81. They bought and renovated it for their needs and opened last fall.

Customers can pay to process their own animals or buy one of the McLean’s quarter, half or full beef to stock the freezer. They can order online, too.

Customers who’ve come to shop after hours use the vending machines in the vestibule. They rotate the carousel, swipe a credit card and flick the drawer of the product they want. After the card goes through, the drawer unlocks the goodies. There are fresh sides, too. Smoked macaroni and cheese, green beans, and garlic mashed potatoes taste mighty fine with that New York strip.

The York community has welcomed the business and especially delighted in the novelty of the vending machines. The only problem is keeping them full, especially on the weekends. In 24 hours, as many as 40 sales go through.

That’s not a problem that keeps Kurth up at night.

BY MEGAN FEENEY

Terri Hirt, a reader from Lincoln, Nebraska, wrote in to praise Alan J. Bartels’ March/April 2021 Nebraska Life profile of Ashland astronaut Clayton Anderson.

“What an inspirational story... While reading, I bit my fingers nervously, felt my heart stop and skip, jumped for joy, and at other times had tears in my eyes.”

That’s the kind of emotional resonance Nebraska Life hopes to create.

A judge for the 41st annual International Regional Magazine Association (IRMA) awards agreed with our reader’s assessment: “A really well done profile, you feel you really know the subject of the feature.” IRMA awarded Bartels the Bronze for the piece in the 2021 Profile category.

all natural sheep’s milk products. Select scents from kids options, unscented Native Nebraska fragrances and more. Try the “Hope” fragrance and Shepherd’s Dairy 4 Ewe will donate 10% of each sale to the American Cancer Society. See our complete line including our gift sets at shepherdsdairy4ewe.com or request a brochure.

“Clayton Anderson’s story is one of those quintessential American stories, of achieving one’s dreams. And working hard, and not letting anything stand in their way,” said Bartels. “Nebraskans from all walks of life achieve their dreams every day. Anderson took his into orbit. I hope my story about Anderson inspired readers to work even harder to achieve their Nebraska-born dreams.”

Bartels formerly served as the Editor of Nebraska Life. He will continue to contribute to the magazine.

“To be recognized by IRMA is a great honor. But the greatest recognition to me is when our readers are entertained by our stories, and they share the magazine with friends and family,” he said.

After years of service to the magazine, Bartels knows the power of stories.

See riveting photos of the West before it was tamed at the Solomon D. Butcher Gallery. Trace your roots through genealogy at the Mary Landkamer Genealogy Library.

Challenge your brain with our Nebraska quiz. Questions by MEGAN FEENEY and ALEX FERNANDO

Call 308-872-2203 or visit CusterCountyMuseum.org 445 S 9th Ave • Broken Bow

Sponsored by Custer County Tourism

The May Museum takes you back to turn-of-the-century Fremont life. Tour the landscaped grounds, a Nebraska Arboretum Site.

Open late April-late Dec. Wed-Sat, 1:30-4:30 pm | Final tour available at 3:30 pm

Admission: $5 for Adults, $1 for Students Free for ages 5 and under

Louis E. May Museum Dodge County Historical Society

MayMuseum.com 402-721-4515 | 1643 North Nye Ave | Fremont

1

Unscramble these words to spell one of Norfolk’s biggest celebrations but be careful not to blow anything up! Nog, gab, om, bib

2

Unscramble these three words to three different words to find out what’s going on in town: loans, wrinkled, foy

3

Corn and soy fields surround Norfolk, but a new kind of farm is under construction on Highway West 275. What kind of farm is it?

4

The Norfolk ‘Fork Fest is a celebration of live music, art and food. The event doesn’t bill a battle of the bands, but there is a competition among another group present. What is it called?

No peeking, answers on page 75.

5 Brave young things try out their gnarliest moves at this Norfolk attraction in the southeast part of Veterans Memorial Park.

6

7

Norfolk’s Nucor Steel produces steel primarily for shipping containers.

Ta-Ha-Zouka Park’s name means “horn of the elk.” It received this name because it’s the eastern-most range of Nebraska’s elk population.

8 Norfolk’s Sculpture Walk Tours take small groups around downtown to admire public art and architecture and to enjoy food and drink at local establishments. Tickets are $30. For those with more money to burn, sculptures are for sale from $2,700 to $20,000.

9 The Cowboy Trail, which runs from Norfolk to Chadron, is the longest rail-to-trail conversion in the United States.

10 Norfolk’s beloved eatery Tastee Treet has been “serving meals and memories since 1949.” Its Tastee Dog is an all-beef hot dog topped with sauerkraut.

11

Native Norfolk son Thurl Ravenscroft voiced Tony the Tiger. His sang all but one of these:

a. “Grinning Ghosts come out to socialize”

b. “S o out come you clowns, all you wolves, all you martyrs”

c. “ Two legs long as willows and paws as big as pillows. Ugh! Such an ugly dachshund.”

12

What was Johnny Carson’s first magician stage name that he used as a teenager in Norfolk?

a. Carnac the Magnificent

b. El Mouldo

c. The Great Carsoni

13

Skyview Park was created out of a flood control project. What activity isn’t allowed?

a. Cross country running

b. Ice fishing

c. Ice skating

14

Before it became Hallmark, what company did three Nebraskan brothers establish in Norfolk in 1908?

a. Norfolk Greetings

b. Norfolk Post Card Company

c. Joyce Hall Cards

15

Verges Cave is named for a doctor that once owned the land. What do urban rumors say?

a. It ’s haunted

b. The doctor performed medical experiments there

c. All of the above

living memorial to renowned writer, Willa Cather! Explore the exhibit, American Bittersweet: e Life & Writing of Willa Cather and tour the nation’s largest collection of nationally designated historic sites dedicated to an American author.

by MEGAN FEENEY

APACK of neighborhood kids skip down the narrow sidewalks of a South Omaha block to the Lithuanian Bakery on South 33rd Street. Father and daughter artists Richard and Rebecca Harrison pause from their work on a mural there to offer the children paintbrushes and simple assignments. Ellie and Robbie Lizdas, trailed by their pug mix Šiauliai, are among the eager young volunteers who have come to help. The children feel proud that the mural, “Sieninis Paveikslas,” tells the story of their Lithuanian heritage. It inspires Ellie and Robbie to share their culture with their tight knit group of neighborhood friends who hail from the diverse backgrounds typical of South Omaha – Polish, Czech, Black, Irish, and Mexican.

Creating new connections and strengthening neighborhoods through collaborative art making is the goal of the South Omaha Mural Project. Started

by the Harrisons eight years ago, the community-funded project employs an arsenal of artists who have completed a dozen murals around “Magic City.” The Lithuanian American Mural, by lead artist Mike Girón, another founding member of the group, was one of the first. Other works include an Irish American Mural on the side of Donohue’s Pub, where regulars flock on the 17th of each month for corned beef and cabbage; a Polish American American Mural on Dinker’s Bar, which serves one of Omaha’s most beloved burgers; and a trio of murals depicting Latino and Indigenous people in Plaza De La Raza, the site of some of Omaha’s biggest annual cultural celebrations.

South Omaha has historically been home to working-class immigrants and their descendants as well as Black Americans who came during the Great Migration (1910-1950) seeking work at the beef packing plants and railroads.

Rebecca Harrison

Historian Gary Kastrick is a consultant for the South Omaha Mural Project. He grew up in a Polish family in South Omaha during the 1950s and ’60s. Back then, people in South Omaha were proud of their family heritage, but another identity unified their different origins, he said. At the stockyards and packing houses, people shared the bond of doing difficult and dangerous work in order to make better lives for their families. Since there wasn’t enough room in the neighborhood to spread out and create separate communities, they lived next to one another and learned from each other.

“My mom made the best gołąbki (Polish cabbage rolls) in Omaha,” said Kastrick. “But when she became friends with our Mexican neighbors and started using Mexican spices, she made the best gołąbki in the world.”

South Omaha used to be a hub for all of Nebraska. Today one South Omaha

Mural Project work located on the side of a grocery store depicts how hard-working Nebraskans from the west to the east have played a role in feeding the nation.

From left to right across the 260’ wall, the scene unfolds. In the background, there is a village of teepees and a train cutting through virgin prairie. In the foreground, a father pulls his baby girl from a covered wagon. Next, a family rejoices in a bumper crop. A Black family raises a “Freeman Family Farm” sign. Men work together to raise a barn as women serve drinks. Fields of cattle loll. The picture gives way to fields resplendent in green, gold and rust. There are corrals for cattle. A woman and her child feed a bottle calf. In the distance, trucks carrying cattle disappear into the horizon. Next, on the other side of those vast fields, trucks arrive in South Omaha, to the stockyards. The slaughterhouses are depicted in silhouette. There are the packing houses of the day – Armour, Swift, Cudahy. And there is a scene of men and women cutting, weighing and sorting meat. Then the picture showcases South 24th Street with its recreation and bustling shops for out-oftowners. Kastrick says the work captures the spirit of those industrious days.

Today 17-year-old Benter Mock is hard at work. As a homeschooled student, she is free to spend her mornings painting a mural devoted to the history and aspirations of Black Americans in South Omaha. Mock was born and raised in South Omaha. Her family is from Sudan. Before she climbs the extension ladder with her can of paint and brush in hand, Mock pauses for a moment to explain her view that it’s a privilege to give back to the place that nurtured her.

“I feel like in South Omaha we’re one big community. You see the same familiar faces every day,” Mock said. “Since I’ve been working on this mural, so many people have stopped by to ask questions and talk to us. People are impressed by the creativity and the history. I hope it brings people even closer together to feel the friendship.”

Soon after Mock begins painting, a local business owner pulls his truck into the parking lot to offer encouragement.

“It’s beautiful,” he says in Spanish.

“Keep going!”

Mock smiles. Her paintbrush doesn’t stop.

On one of the last days of the Lithuanian mural painting, a hot day, Ellie Lizdas brings something to the site that’s even more sustaining than the stories she’s been sharing about her culture. The

9-year-old girl cradles a pitcher of cold beet soup, or šaltibarščiai, that she made with her grandmother to cool and sustain the artists and children. It’s a mixture of seemingly impossible ingredients. And it’s delicious.

Visitors to South Omaha’s murals can take a break at beloved pubs, bakeries, supermarkets and public squares.

Dinker’s Bar & Grill

2368 S. 29th St.

Dinker’s offers one of Omaha’s most raved-about burgers made the old-fashioned way – with an ice cream scoop and a hand press. Homemade onion rings come out sizzling. Creighton fans quaff the Bluejay, a Dinker’s original cocktail made with blue liqueur. On the wall outside, satiated customers take in the Polish Community Mural. Cash only.

Lithuanian Bakery

5217 S. 33rd Ave.

The Lithuanian community mural by lead artist Mike Girón is a deliciously layered masterpiece decorating an exterior wall of the Lithuanian Bakery. Inside the bakery is another deliciously layered masterpiece. The Napoleon Torte is a traditional dessert that takes three days to make – and less than one day to eat. Bakers stack eight paper-thin pastry layers with buttercream and apricot filling. The bakery has a second location in Midtown.

Plaza De La Raza

24th and N Street

Plaza De La Raza, which translates to “the square of the races,” showcases the Mexican, Native American and Mayan community murals. Food venders, live music and artisan booths fill the plaza for Cinco de Mayo in May and Fiestas Patrias in September. Vaqueros mounted on dancing horses eventually cede the floor to salsa enthusiasts.

Donohue’s Pub

3232 L St.

Regulars pack in on the 17th of each month – called St. Practice Day – for corned beef and cabbage. Waitstaff greet people by name, and the owner, Mike Donohue, visits tables to chat with regulars and newcomers. Reuben sandwiches drip and Guinness flows. The Irish community mural, “Sláinte,” graces the outside of the pub facing L Street. On Monday nights, the pub serves tacos. How South O is that?

Supermercado Nuestra Familia

3548 Q St.

After taking in the panoramic “Sesquicentennial Mural,” art lovers can spread out at picnic tables inside and tuck into an enchilada, tamale or fried chicken dinner from the deli, which also serves ice cold horchata – a beverage made with rice, vanilla and cinnamon. Aspiring chefs of Hispanic cuisine thrill at the assortment of fresh and dried chilies, dried hominy and beans, and generous cheese, meat and fish selections.

Photographers capture frozen Nebraska

OnNebraska’s rural highways and city streets, ice forces us to slow down. Ice stills what is frail and what is forged – it freezes the wildflower and the tractor. Ice quiets the drumbeat of waterfalls and the lapping of lakes. It softens the barbs of fences and the prick of pine needles. Sun streaming through ice invites us to celebrate the magnification of light. We know it won’t last long. In winter, the night is always close by. We choose each step on the ice. We comfort ourselves that someone might catch us if we fall. We take time to look for the light. We take time to wonder.

Above, the Platte River by Gjerloff Prairie near Marquette. Ice suspends shore-lapping ripples. Top right, the first sunny morning after a two-day ice storm in Aurora. Wet seeds will drop to the earth. Middle right, ice bejewels pine needles in Eustis. Bottom right, usually associated with spring, robins don’t often winter in Nebraska, but some, like these beauties enjoying a bath in an Omaha backyard, adapt to eat berries and flock together to survive.

Spinning steel wool on the Elkhorn River, light spiders its radiance across the frozen surface. The effect is created from high speed oxidation. The Desoto Wildlife Refuge near Blair (far left) and photo of a gravel pit in Madison County near Meadow Grove (left) offer icy reflections of big Nebraska skies.

story by MEGAN FEENEY

photographs by BROOKE STEFFEN-KLEINSCHMIT

AFTER A LONG day working cattle in Cedar County, veterinarian Ben Schroeder came home one evening to discover his pregnant wife Erin wielding a sledgehammer.

The two had fallen hard for each other a few years earlier during veterinary studies at Kansas State. Erin was a freshman; Ben was a junior. For their first date they played basketball and grabbed a sandwich. Within two weeks, they were engaged. Within six months, they married. The newlyweds studied side by side until Ben graduated and went to work for a local animal hospital. They had their first son, Charlie, and, after Erin graduated, the family moved back to the rolling hills of Northeast Nebraska where Ben had grown up. Erin and Ben went into practice with Ben’s veterinarian father, Dr. John Schroeder, and bought a charming old farmhouse, where they anticipated the birth of their second child.

The farmhouse had a kitchen wall that Erin couldn’t abide a moment longer. It needed to come out that night.

Ben knew that once Erin made up her mind, nothing could stop her –just like when Erin was a 12-year-old girl and asked her parents for a horse.

years,

Her father told her that if she filled two buckets with water and dragged them to the garden every morning at dawn to water and weed for a month without fail, he’d think about it. Erin not only got her horse, but she also earned the money to pay for its hay.

Ben loved his wife’s determination –even if it meant he had to knock out a wall after work.

Making their home a better place became a motif in the Schroeder’s lives in Cedar County. “Home” extended beyond the four walls in which their growing family resided. The Schroeders sought to improve quality of life for their community’s livestock and domestic animals, volunteered their time with their children Charlie and Chase’s schools, and bought and renovated historic real estate in downtown Hartington. More recently, as stars of a reality tv show, Erin and Ben have become de facto ambassadors for Nebraska and rural veterinary medicine.

OVER THE YEARS, emergency calls sometimes interrupted dinner. One evening Erin and Ben, along their now teenage sons, Charlie and Chase, rushed to the Schroeder’s Hartington clinic, Cedar County Veterinary Services, to attend to a newborn deer. It had been hit by a lawn mower and couldn’t move its back legs or stand. Erin and Ben cradled the spotted fawn gently as they examined it. An x-ray revealed no fractures. They couldn’t rule out neurological damage. The fawn quivered its black nose and blinked its soft eyes.

For the next few days, the Schroeders shuttled the fawn between their home, where they could observe it overnight, and back to their clinic. They enlisted Chase to cuddle the deer at night. Ben bottle-fed it and gave it anti-inflammatories. Erin rejoiced one day when the fawn seemed to respond to the water therapy that she’d devised using a stock tank with a pool noodle assist.

Three days on, the fawn’s temperature dropped. Its legs felt cold to the touch, and it had no pain response. It was time to say goodbye. The fawn squeaked as Erin administered a shot to relax it. Ben took over the next part. When it was done, the couple cried and held each other.

These vulnerable moments played out in front of an eight-person film crew that tags along with the Schroeders for about six months of the year taping Heartland Docs. The show just wrapped filming its fourth season for National Geographic Wild, a network owned by The Walt Disney Company and National Geographic Society. Heartland Docs follows the Schroeders working at farms in Cedar County and at their Hartington clinic. It brings the small farming community of Hartington, population 1,500, into tens of millions of households worldwide and showcases the town’s thriving downtown, well-kept homes and natural beauty with poetic sweeping shots.

Heartland Docs doesn’t flinch from the hard choices people make or the copious poop animals make. It also reflects the truth that farmers – even those that raise livestock for meat – care deeply about their animals and suffer when their animals do. Erin and Ben’s tenderheartedness also radiates.

John Schroeder was certain his son would make a good vet because even as a boy Ben demonstrated that sensitivity. One day on a veterinary call with his dad, 10-year-old Ben spotted the family’s border collie Katie dead on the side of the road. Ben leapt from the truck and hurried back to the spot they’d seen her. Cradling her body in his arms, he ran the quarter-mile home sobbing.

Shortly after the deer’s death, Ben bought a fawn statue to memorialize it. “John Deer” stands on a coffee table in the clinic foyer.

Knowing love, knowing loss – it helped Ben support clients navigating difficult times.

Ben takes some air after doing “preg checks” at a dairy farm in Hartington. Ben felt called to the profession from a young age when he went on veterinary calls with his dad.

FOUR FAT GREY geese patrolled a Hartington farmyard on a recent morning. Single file, they paced in front of a red barn and honked alarm. Sixty mileper-hour winds rattled the chains on livestock gates and bent cedar trees sideways. A loose bucket rolled like a tumbleweed. Grey skies spit snow.

Inside the barn, cows lowed as Ben worked with farmer John Steffen on “preg checks.”

They worked in batches, coaxing about a dozen mostly Holstein and some Jersey cows at a time along a walkway into a smaller area, where they closed the gate with Ben inside. He shouldered for space among the 1,500-pound behemoths.

Holding an ultrasound probe, Ben inserted his glove-covered arm into each cow. A visor on his head displayed the images.

The cows muscled for position in the tight space. Pressed by the weight of the animals, Ben held his ground, using the full force of his 6’4” frame. But one cow whipped her backside hard against him, and for an instant, he rocked on his heels. His hands scrambled for the back of another cow to regain his footing.

“You alright there, Ben?” Steffen yelled from the door ledge above the gated area.

Ben grimaced and asserted yes.

Ben had his first dangerous encounter with a cow when he was 8 years old doing rounds with his dad. A cow put her nose down and chased him around the family truck. Ben’s dad scooped him up and tossed him on the battery box out of harm’s way.

Steffen and Ben didn’t talk about what could have happened if the vet’s manure and snow-slicked boots had gone out from underneath him.

Instead, they got back to work.

On a clipboard, Steffen noted the animals’ ear tag numbers and the gestation results Schroeder called out, cow by cow.

“This one’s five, six…whoa girl, easy… This one’s six, close to seven….This one’s open.”

Five or six meant the cows were that many months bred. Open meant not pregnant. It wasn’t what Steffen wanted to hear. Especially on that day.

After 32 years as a dairy farmer, Steffen was getting out. This was Ben’s last time coming to his farm for a preg check.

It was a bittersweet day for the farmer.

“And there’s going to be a lot more days like this one,” Steffen said.

In the distance, a truck rumbled. Tires crunched on the gravel driveway.

“There’s the trailer,” said Ben, without looking up from his work.

A man from another Nebraska dairy operation had come to load Steffen’s cows.

Steffen loaded the ones scheduled to go that day. Hooves thumped and bodies shuffled and clanged against the aluminum sides of the trailer. The truck engine fired, and, just like that, his cows were gone.

The fat grey geese marched and marched and screamed at the wind.

clinic, dressed in scrubs, Erin performed what she jokingly called “brain surgery.” In fact, she was neutering and spaying feral kittens a farmer had brought in that snowy morning. She also removed a tiny tip from each kitten’s ear –a recognized indicator that an animal has been altered. This kind of routine daily work doesn’t make the show. Producers create a 52-minute episode from 150 hours of taping. Having an eight-person filming crew around hasn’t affected how the Schroeders do business. If there was an emergency, the crew had to hustle, too. One benefit of wrapping the season and saying farewell to the film crew was that staff could listen to music in the clinic again. Music messed with editing tape.

Finished with the kittens, Erin tucked them into a warm towel and placed them into a carrier. She paused a moment to stroke their little heads and coo, but she didn’t have time to linger. The white board in the hallway still had unfinished tasks, and she had to leave early to apply stage makeup for her high school kids’ one act rehearsal in Wynot.

Next up, Erin removed a cast from a dog who’d been hit by an ATV. The little white dog shivered on the stainless-steel table as Erin worked. When Erin was done, she put the dog on the floor. It gingerly became a four-legger again.

“Animals amaze me with how adaptable they are,” Erin said. “I stub my toe and complain about it for a week. Three legs, or a leg in a cast – animals are so dang resilient.”

As if on cue, Spaghetti Bob loped into the room. A Department of Transportation worker had brought the kitten in a few weeks back. Its tail was degloved – the fur and skin stripped away – and Erin had to amputate it. Spaghetti Bob – named because he goes limp as a noodle when petted and Bob, because, well, his new tail – had become a clinic kitty and will make his debut television appearance on the fourth season.

Erin has navigated plenty of her own life twists and turns. Like Spaghetti Bob, she landed on her feet. About nine years back, Erin felt weak and cold at the clinic. She lay down on the floor. A client gathered her and rushed her to the doctor. Erin had contracted an infection from the bacteria that causes the respiratory disease strangles in horses. She spent two weeks in the ICU. Her Nebraska community rallied around her. She wasn’t a native daughter, but she was their daughter. With their help and love, she made a full recovery.

Erin grew up on a farm in Upstate New York. When she went to vet school in Kansas, she wasn’t sure where she’d end up.

She credits her Nebraskan father-in-law for her introduction to the community she would serve and call home.

In the early days of her relationship with Ben, Erin bonded with his dad John on calls down gravel roads deep in the country hills.

“I’d joke with him that he couldn’t die because I’d never find my way out,” said Erin. “And he knew everybody. He’d say, this is so-and-so, who is so-and-so’s nephew, who married so-and-so’s daughter, who works at so-and-so…”

John Schroeder retired, but he still liked to ask Erin and Ben about people’s farms and animals. Many times, Erin and Ben had to break the news – like Steffen, those farmers got out. They worked in town now.

lunchtime diners dug into steak sandwiches and turkey cobb salads at The Globe Chophouse. Owner Kate Lammers walked among the tables greeting guests, helping waitstaff and assisting an ad salesperson from Cedar County News, which operates across the street.

The corner-facing Globe Chophouse sits at East Main Street and North Broadway

Avenue. Natural light pours in from oversized windows. Wood floors, black walls, and a silver-painted tin ceiling with enormous metal ceiling fans create a dramatic effect. Upstairs is a second dining area with exposed brick walls and a “Globe Clothing” sign. Rebuilt in 1901 after a fire devastated much of downtown Hartington in 1888, Globe Clothing was once a shopping destination for people in the tri-state area until it closed at the end of 2016.

“Everyone in Hartington has a memory of renting a tux or buying a dress from Globe Clothing,” Lammers said. “Every-

one has a story connecting them to this place.”

Erin and Ben Schroeder do too. After Globe Clothing closed, they took over the building and began renovating it. They created a loft apartment for their family in the space above the first two floors and refinished the building’s hardwood floors and tin ceiling. Each morning, they rose early to carry out the plaster they’d chipped off the brick interior.

People noticed. Other new downtown businesses opened, like Uptown Charm, a clothing and décor store, and Leise Tax

Erin didn’t grow up in Nebraska, but people in Cedar County have claimed her as their own. She and Ben have not only restored local historic buildings, like Hotel Hartington (featured in the background), they’ve also coached and mentored young people in their community.

& Bookkeeping, which later underwent its own ambitious historic renovation. Owners spiffed up established businesses, too. Broadway Lanes refreshed its façade. The gym REPS replaced its windows and door.

Downtown Hartington doesn’t have empty buildings. It has a family-owned pharmacy, a local grocery store and a bank. It has shops and eateries and pedestrian sidewalk traffic. Lammers said the Schroeders helped ignite downtown Hartington’s revival.

“Their tremendous passion showed every entrepreneur the possibilities,” Lammers said.

Lammers bought the Globe building from the Schroeders at the beginning of 2021, put in an extra restroom, a wooden bar and a special occasion booth and opened her restaurant in late spring. She moved into the upstairs apartment with her three children. It’s perfect for their needs, except for those hard-to-reach custom-built kitchen cabinets and counters.

“The previous owners were both at least a foot taller than me,” Lammers laughed.

She hopes that like Globe Clothing before it, her restaurant can not only serve

the local community but draw tourists. For that reason, she’s grateful for another business that launched across the street around the same time hers did.

Big Hair Brewhaus resides in the building that once housed Surge Sales & Equipment, a dairy and machinery equipment company. Cousins Brett Wiedenfeld and Reed Trenhaile bought the building from Erin and Ben who’d redone the floors and put in new windows during the year they owned it. Wiedenfeld and Trenhaile knocked out an office and constructed a bar in its place. They installed a brewing room, built a beer garden out back and decorated the interior with historic Hartington items, like the original Surge sign and a scoreboard from Hartington City Auditorium. Trenhaile brews beers with ingredients like a domesticated version of a wild Nebraska hop and local honey.

After the business opened, the widow of the man who ran the Surge business visited. She ordered a gin and tonic and marveled at what the young men had done with the space. The stainless steel, the décor, the drinks and the way they’d kept that “garage” feeling – it would have made her husband so proud.

When other visitors said, “This could have been out of Omaha or Lincoln,” Wiedenfeld’s response was always the same. “Why couldn’t it have been out of Hartington?”

SOME PLACES COULDN’T have been from anywhere else. That’s why Erin and Ben took on the three-story historic Hotel Hartington just before the beginning of 2018. They’d hoped to restore the 1915 beauty to her former glory. But now, in the freezing dark, staring at a sinkhole the size of a tractor, Ben was having some serious second doubts. He’d been jackhammering to install a new septic line in the basement when he hit a spot so soft that he nearly lost his power tool. Concrete crumbled into an abyss.

Early estimates to fix the sinkhole ran $100,000. In the same month, the Schroeders were told they needed to put in an elevator to make the building ADA compliant. That would run them another $300,000.

“We were just like, ‘what have we done?’ We had so much hope,” Erin said.

She made some calls. If they couldn’t find more affordable options, the hotel would become another grassy lot. The city

provided a grant. The Schroeders secured an economic development loan. They got a substantially better bid for the sinkhole repair. They committed more personal funds. They pushed through their despair to find solutions. It was a skill they’d honed as vets, as parents and as athletes. (Erin played Division 1 basketball at Syracuse University; Ben was a competitive intramural player. Both coached the sport.)

Today, the hotel shines. Original wallpaper in the lobby received a cleaning and mending. Look closely enough, and it’s possible to see the tiny fissures where bits were glued back together. These are the grand dame’s smile lines. The cracks in her original tile recall the people she’s welcomed. Glowing wood floors and a regal staircase creak their greetings. Erin designed each of the rooms and gathering areas in the hotel’s four wings and furnished them with a mixture of thrifted and new items.

The National Geographic film crew stays here when they are shooting. On a recent weekend, a bridal party booked one of the wings. The pandemic forced some changes. The Schroeders closed their onsite restaurant – now it’s the site of Chasin’ Charlie’s General Store – and the lobby coffee shop. Erin and Ben offered Elsie Driver, the coffee-loving teenager who’d worked as their barista, their Italian espresso machine in exchange for help cleaning rooms. The home-schooled girl accepted the offer. With the machine, she rented a spot at a boutique a couple doors down and opened Elsie’s Sassy Brew. She was 16 years old. A year into her venture, customers line up at 7 a.m. for Elsie’s lattes, cappuccinos and Italian sodas to-go.

Hartington business launched across the street from the hotel by another photogenic couple. Racheal and Travis Folkers bought their building from Erin and Ben in 2021. Travis needed space for his painting business. The building had a basement and a garage that fit the bill, but there was more space to work with. The Folkers created a community gathering place. There is a spacious wifi lounge for people to hang out, play board games or get some work done. Admission is a rotating

free-will donation that goes toward local organizations, like a women’s shelter or a food bank. The Folkers constructed forrent office spaces and study cubbies and are putting the final touches on an Airbnb rental upstairs. Like Erin, Racheal is the one in her relationship with the artistic vision.

“I just say what I want, and Travis makes it happen,” she said.

Together, the Folkers took the plaster off the wall brick-by-brick.

It seems it’s just the way Hartington’s young entrepreneurs operate.

ERIN CROSSED HER last task off the clinic whiteboard. Ben would be leaving shortly to work on one of the couple’s latest renovation projects, a big red barn. Erin was heading to Wynot Public School to help with stage makeup for the high school’s one-act rehearsal of “The Jungle Book.”

Before Erin and Ben split ways to conquer their own undertakings, they took time for a proper kiss goodbye. After renovating 10 buildings in Cedar County, serving farmers and pet owners for near-

ly two decades, championing other local entrepreneurs, taping a beloved show, and raising two well-adjusted kids, their marriage was still a top priority.

Erin grabbed her makeup bag and jumped in her truck. Being on television hadn’t changed how people in their community interacted with her. She was just another mom running slightly behind schedule.

Inside the gym, teenagers shouted, laughed and ran around. Wynot has one building for all its grades. The elementary scent of crayons mixed with the tang of teenage sweat. Forty-five of the 60 high schoolers at Wynot were involved in the production. And it sounded like it.

“I don’t have my leggings!”

“I forgot my t-shirt!”

“Who’s going to do my makeup?”

Erin started with her oldest son, 18-year-old Charlie, who was playing the bear Baloo. She put a hairnet on his head and traced black lipstick around his nose. What was the role’s biggest challenge for him?

“Mom has always told me to stand up straight, but Baloo slumps,” Charlie said.

After the bear was finished, Erin worked on her first of 10 monkeys, her 16-yearold son Chase. His favorite part about taping the show was meeting crew members from across the country. As the baby born into that first farmhouse renovation project, Chase joked that it’s totally normal for him to have a sink in his bedroom or a stove sitting outside his door. He’s not surprised if his parents ask him and his brother to help move furniture at 10 p.m. This is what they do to relax. He said he’ll probably be the same way someday.

Erin used the steadiness of her surgeon’s hands to whip through her barrel of monkeys just in the nick of time. The drama coach called the kids to the stage. Erin sat in the front row to watch.

When the house lights went down and the stage lights went up, her sons helped their classmates tell a beautiful story. It was a story about belonging to a community and contributing your unique gifts to it.

recipes and photographs by DANELLE

McCOLLUM

MANY NEBRASKANS CHERISH fond memories of school lunches featuring chili with a cinnamon roll. When Nebraska Life reader Carol McDonough Carpenter’s kids were in elementary school in Peru, she’d join them on Wednesdays when the cafeteria served the combo. Other readers, like Crystal Powers from Ceresco, prefer cornbread with their chili. After all, we’re “Cornhuskers, right?” No matter what your preference, everyone will find something to delight them in these recipes from food blogger Danelle McCollum.

The sweet, caramelized flavor of Dr Pepper dances with the heat of the jalapeño and the zing of fresh garlic in this chili. Chuck roast lends a rich beefy body to the piquant stew.

Cut roast into bite-size pieces. Heat 1 Tbsp oil in a large skillet over medium-high heat. Sear meat on all sides, being careful not to crowd the pan. Transfer meat to a lightly greased slow cooker. In same pan, sauté onions, peppers and garlic, adding more oil if necessary, until soft, about 5 minutes. Add to slow cooker along with meat.

Stir one can of Dr Pepper, along with tomatoes, spices and beans into the slow cooker. Cover and cook on low for 8-10 hours. About 30 minutes before serving, stir in cornmeal. If desired, stir in another half can of Dr Pepper before serving. Add toppings like cheese, fresh veggies and corn chips, according to taste.

1-2 Tbsp cooking oil

1.5-2 lbs beef chuck roast

1 medium onion, diced

1 red pepper, chopped

1 jalapeño pepper, seeded and diced

3 cloves garlic, minced

1-2 cans Dr Pepper

1 28-oz can crushed tomatoes

1 14.5-oz can diced tomatoes

2 Tbsp chili powder

1 tsp ground cumin

1 tsp dried oregano

1/4 tsp red pepper flakes (optional)

1/2 tsp salt

1/2 tsp pepper

1 15-oz can pinto beans, rinsed and drained

1 15-oz can kidney beans, rinsed and drained

1/4 cup cornmeal

Ser ves 10-12

This easy-to-make recipe combines the earthy flavor of cornbread with the robust taste of cheddar and the grassy sweetness of green onions. A hint of jalapeño provides balance but doesn’t overwhelm.

Preheat the oven to 350°. Grease a 9 x 9-inch square baking pan.

In large bowl, combine the flour, cornmeal, sugar, baking powder and salt. In separate bowl, whisk together milk, egg and egg yolk and melted butter. With a wooden spoon, stir wet ingredients into dry until most lumps are dissolved. Don’t overmix. Stir in 1 cup of the cheese along with green onions and jalapeños. Allow mixture to sit at room temperature for 1015 minutes.

Pour batter into prepared pan and smooth top. Sprinkle with remaining cheese.

Bake 23 minutes, or until a toothpick inserted into the center comes out clean. Place on wire rack to cool slightly before slicing and serving.

1/2 cups flour

1/2 cup cornmeal

2 Tbsp sugar

1 Tbsp baking powder

1 tsp salt

1 cup milk

1 egg + 1 egg yolk

1/2 cup butter, melted

1 ½ cups shredded cheddar cheese

2 green onions, chopped

1 small jalapeño, seeded and finely diced

Ser ves 8-10

A bold claim and a time-intensive project for a weekend or a day off, but food blogger McCollum says patient bakers will find this recipe’s result worthy: frosted pillowy soft cinnamon rolls that stay delectable for days. Think they’ll last that long?

Rolls

Heat milk in medium saucepan until just simmering and bubbles form around edge of pan. Pour milk into bowl of an electric stand mixer fitted with dough hook. Add butter, sugar and salt. Mix on low speed until butter is melted. Let mixture cool until warm but not hot. Add yeast and eggs and mix until combined. Gradually add flour until dough clears sides of bowl. Dough should be soft and slightly sticky. Knead two to three minutes.

Transfer dough to a large, lightly greased bowl. Cover with clean kitchen towel or lightly greased plastic wrap and let rise until doubled, about one hour. Roll dough into a large rectangle, about 18 x 12 inches. Spread 1/2 cup softened butter over the dough. Stir together brown sugar and cinnamon and sprinkle over dough. Pat it in slightly with palms of your hands. Starting with a long end, roll up the dough as tightly as possible, pinching seam lightly to seal. Using a serrated knife, cut roll in half. Then cut each half in half again (forming four equal portions). Cut each of the four portions into three rolls – 12 cinnamon rolls total.

Place rolls evenly spaced on a large, parchment-lined, rimmed baking sheet. If ends have come free, carefully tuck them under the cinnamon roll. Cover and let rise until doubled.

Preheat oven to 350°. Bake the cinnamon rolls for 18-22 minutes until light golden brown. Let rolls cool about 10 minutes before frosting.

Frosting

In large bowl, whip together cream cheese and butter. Add vanilla, maple syrup and salt and mix until combined. Gradually add powdered sugar and mix until thick and creamy. Add cream or milk a tablespoon at a time until the frosting is smooth and spreadable. Spread cinnamon rolls with frosting.

Rolls 2 cups whole milk 1/2 cup butter, softened 1/2 cup white sugar 1 tsp salt 1 Tbsp instant yeast 2 eggs 5 ½-6 cups flour 1/2 cup butter, very soft 1 cup packed brown sugar 1 Tbsp ground cinnamon

Frosting

4 oz cream cheese, softened 1/4 cup butter, softened 1/2 tsp vanilla

1 Tbsp pure maple syrup

Pinch of salt

2 cups powdered sugar

1 Tbsp milk, or as needed for consistency

Makes 12 rolls

Send your family recipes, and the family stories behind them, for possible publication in Nebraska Life. Submit by emailing kitchens@nebraskalife.com or by mail to the address at the front of this magazine.

Ken Smith

Surrendering to the slower pace of colder days and longer nights, Nebraska’s poets discover moments of grace and beauty in the natural world and its many gifts. Wrapped in the coziness of these images, winter doesn’t seem so bad.

Earl Sampson, Newcastle

Turkeys came this morning to sample corn put out for the deer. Nearing noon now, the squirrels are here. They sit with fluffed tails up on their backs, Scratching for kernels in old turkey tracks.

Juncos, jays and a tufted titmouse, Eating sunflower seeds up by the house. Now we’re approaching the best time of day, With the sun in its blankets and deer on the way.

Breezes have died and everything’s still. They come from the cedars west on the hill. They stop at a puddle as still as a mirror, Filled with reflections of snows, trees and deer.

They pause, heads raised to sample the wind, Seeking messages that it might send. They lower them now, sipping what’s there. Drinking themselves and the cooling night air.

Gene Fendt,

Kearney

It has been falling for hours in the night –straight down, great, soft flakes: the mercy of God.

It clings to rest on everything, this cope of grace, an inch of thick, bright heaven on each brief twig.

We will make a mess of it with our engines, the mess will freeze tonight: curse it.

Kim Zach, Omaha

gnarled charcoal fingers stretch towards the sheet-metal sky snatching pearl gray clouds

Faye Tanner Cool, Broken Bow

From my second story apartment window I view snow-covered rooftops… White smoke rising from chimneys… Bare branches of trees stirring…and A whirl of birds, one making A brief rest stop While the sky blankets all of this With its grey eiderdown.

Just outside of Omaha, hoarfrost covers weeping willow trees to create an otherworldly landscape of blue and white. Winter days like this one inspire restful contemplation.

Jerry Gronewold, Kearney

The early morning comes as the sun creeps to the east cottonwood trees

There is a certain calm around the farm as if it’s waiting.

To the north it sounds like a cat purring on grandpa’s lap

The purring turns into a wind that turns the old windmill.

Stormy the palomino horse seems to sense something is coming

Her ears are perked to the north as if she’s watching.

Her colt Cocoa stands beside her listening to the wind coming

The door on the white barn slaps against the side scaring the cats.

A white curtain filled with diamonds of color swirl up the east driveway

The old white propane tank is full waiting for the cold days.

The wind seems to say, “I’m here,” and visits you all day

The white snow accumulates in the barnyard and farmstead.

The old milk cow meanders toward the barn to get inside.

All is quiet in the chicken house, where they are in their roost.

The snowy wind touches all the buildings with a gentle caress.

There is light in the kitchen farmhouse.

Mitsy the German shepherd has taken shelter in her bale house.

All is quiet, as the wind and snow seem to dance like a New Year’s Eve ball.

The snow makes white sculptures around the buildings and on the fence

The day creeps on like a day in the fourth grade at the country school.

The wind seems to die and the white snowdrops drop like a curtain

The farm is now a beautiful white covered with the first snow.

Tomorrow will be a busy day with the tractor and the scoop

There will be snowbanks for the kids to play on.

Ian Nauslar, Omaha

The winds cut like a razor. Temperatures leave little to savor. Shivers knock knees, so why do we choose to freeze when in the land of the free we could move as we please?

There’s a magical warmth in that first snow blanket covering a land turned barren and naked by a fall that fell too fast. We Nebraskans are resilient, built to last.

Like the snowballs we make, it’s a blast.

Those wooded walks in the middle of winter, when life leads me astray it’s where I find my center. With a silence so sweet me and the creator meet face to face.

We hold each other in the warmest embrace.

So ask me again why I chose to stay when some would rather stray away.

I’ll tell you how I decided this was it a bountiful land that’s surely a gift.

It’s a beautiful song nature boldly screams, A place to play, a place for dreams.

NEBRASKA LIFE IS seeking poems about picnics, family or class reunions, neighborhood block parties and other communal activities enjoyed during late spring/early summer in Nebraska. Feel free to send along photos, too! Poems set in specific Nebraska places are preferred. Send to poetry@nebraskalife.com or by mail to the address at the front of this magazine.

Charles Henry Morrill safeguarded Nebraska’s archaeological relics

by TIM TRUDELL

ON THE WESTERN-BOUND train, Charles Henry Morrill watched the besieged Nebraska land whiz past. Where corn once grew tall, there were bare scarred fields. A second year of Rocky Mountain locust swarm had devastated the land and the hopes of many homesteading farmers. It had also dimmed prospects for the farm implement store Morrill established after he moved his young family to a homestead south of Stromsburg. Farmers without crops had no use for Morrill’s plows, sickles, hoes and pitchforks.

Morrill was on his way to South Dakota to pan for gold. It was a last-ditch effort to save his family farm. His wife, Harriet, and their young children would await his return in their 16 x 16-foot wooden house he’d had built for them. Many homesteading families lived in sod homes, but Morrill had greater ambitions.

From the train window, Morrill couldn’t see where his journey would lead. Ultimately, he wouldn’t make it to South Dakota to search for gold. Instead, he would encounter a different kind of treasure in Nebraska’s Badlands. Fossils of ancient creatures fascinated him and compelled him to devote the fortune he would one day make to preserve natural history wonders for all Nebraskans.

BY THE TIME, he reached Fort Robinson in Western Nebraska, Morrill realized odds of striking gold in South Dakota weren’t good. He accepted the offer of a reliable wage as the trading post clerk there and stocked shelves, kept books and sold goods.

One day he noticed a long row of white tents nearby. He learned that men were digging for fossils under the guidance of O.C. Marsh, a world-renowned archaeologist from Yale University. Marsh was one of the first bone diggers to explore Western Nebraska. Considered America’s version of Darwin, Marsh had discovered the first pterosaur fossils in America, as well as the remains of dinosaurs, including Triceratops, Stegosaurus and Allosaurus.

Morrill joined the team for the Hat Creek excavation in Nebraska’s Little Badlands – an area featuring buttes, deeply cut crevices and narrow rocks stretching skyward. As Morrill investigated the area, bones crunched under his feet. These were the bodies of animals that traveled across Nebraska before the Ice Age.

There were large mammals resembling ancient rhinoceros. These titanothere fossils dated back 35-38 million years. On the North American continent, they have only been found in the Chadron Formation, a region that stretches from western North Dakota to Northwest Nebraska.

There were tiny horses and enormous turtles that thrived in the vast rolling plains with long grass for food and shel-

ter and watering holes to quench thirst. They’d likely died during a drought. Their remains baked in the soil, forever linking them to Nebraska.

O.C. Marsh instructed his men to pack up their finds. The fossils were leaving the state for museums in the East.

That troubled Morill.

“It seemed desirable that the remains of these remarkable creatures be preserved for the state,” he later wrote in his autobiography, The Morrills and Reminiscences.

He came away from his first bone-digging experience determined to find a way

to do that. He would get the chance 16 years later when he teamed up with an energetic young fossil-hunter named Erwin Barbour.

MORRILL REJOINED HIS family in Stromsburg to give farming another try. This time, they succeeded. They added 400 more acres to their 160-acre homestead and made improvements to the house. As the children grew, Morrill turned over more farming responsibilities to them and focused on other business ventures. He befriended Gov. Albinus Nance, a

fellow Polk County resident, who hailed from nearby Osceola. Morrill accepted a position as personal secretary to the governor, splitting time between the Lincoln State Capitol and the family farm. His work with Nance connected him to some of the state’s most powerful men.

Morrill left Nance’s administration and became president of the Bank of Stromsburg. It marked a successful turn in his career, which would lead to additional ventures with land banks and corporations. These political and social connections led to his appointment to the Board of Regents at the University of Nebraska, where he would serve for more than a decade, starting in 1890. Erwin Barbour, a university hire who’d come on board the following year, would reignite Morrill’s passion for Nebraska’s natural history.

ERWIN BARBOUR BELIEVED the Nebraska State Museum at the University of Nebraska could become a world-renowned institution. It just needed a bigdeal artifact that could rival the stuff in history museums back East.

Right before he assumed his post as the museum’s new director in 1891, he traveled to the Agate area in Western Nebraska on his own dime. He discovered an artifact that would be the envy of any institution’s – the Daimonelix, or Devil’s Corkscrew, a tall, spiraled helix rising from the depths of the earth.

“Their forms are magnificent; their symmetry perfect; their organization beyond my comprehension,” he wrote.

The mysterious formations left scientists puzzled for many years until it was ultimately determined enormous extinct rodents had made them.

Barbour shipped the fossils to the university and traveled to Lincoln to begin his new job. There were so many fossils –and they were so heavy – that they made the museum floor sag.

Morrill summoned Barbour to his office after learning of Barbour’s adventure in Western Nebraska. Barbour feared he was in trouble for bringing “only” 70 fossils from his dig. He was surprised to learn that Morrill had called him there to tell him that he’d finance Barbour’s future expeditions. Morrill also arranged free

rail transportation through his contacts with the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad.

In the early 1900s on a trip to Agate, near Harrison, Barbour found a bevy of fossils in one of two conical hills. There were prehistoric horses, rhinos and beavers the size of large dogs.

With more than 3,000 acres to explore, visitors to Agate Fossil Beds National Monument today can view exhibits featuring animals, such as the Dinohyus, which resembles a cross between a bison and a pig, and the Daphoenodon, a “bear dog.”