JULY/AUGUST 2022

JULY/AUGUST 2022

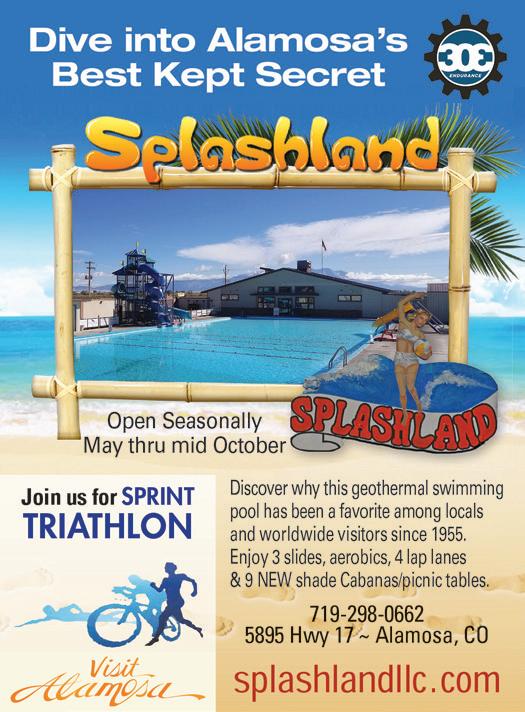

In the southeast corner of Colorado, Baca County’s surprising and scenic natural landscape boasts a stunning array of hoodoos, petroglyphs and wildlife.

Story and photographs by Joshua Hardin

30 Colorado Gem Prospector

On the steep slopes of Mount Antero near Salida, prospector Brian Busse raised six children while hunting for gemstones at his Thank You Lord Aquamarine Mine.

Story by Tom Hess

Photographs by H. Mark Weidman

40 Mulberry Community Gardens

A band of green-thumbed volunteers cultivates a bumper crop of friends while growing vegetables at a beloved community garden in Fort Collins.

Story and photographs by Valerie Mosley

52 Bandimere Speedway

On each Wednesday night in summer, amateur racers burn rubber on a nationally renowned professional drag strip in Morrison known as Thunder Mountain.

Story by Tom Hess

Photographs by Joshua Hardin

Gem prospector Brian Busse hunts for aquamarines on the slopes of Mount Antero. Story begins on page 30.

p 16

Craig p 60

p 15

Morrison p 52

Leadville p 20, 67

Denver p 61

40

A pagoda towers five stories in Longmont; students build trails in Trinidad; artist creates human-size spiderwebs in Durango; motel’s sign puzzles passersby in Lakewood.

Colorado Trivia

Test your knowledge of Colorado’s Wild West past.

These ice cream recipes offer a flavorful way to keep cool.

49 Poetry

Our Colorado poets reflect on the power that wilderness has to show humans our true place in nature.

60 Go. See. Do.

Our statewide roundup of the best local festivals, events and daytrip ideas to check out for fun summertime adventures from all parts of the state.

67 Colorado Camping

May Queen Campground at Turquoise Lake near Leadville offers high-altitude camping in historic mining country.

70 Top Take

In our editors’ choice photo, Dry Creek Falls plunges from a cliff during a scenic sunset outside of Montrose.

JULY/AUGUST 2022

Volume 11, Number 4

Publisher & Executive Editor

Chris Amundson

Associate Publisher

Angela Amundson

Editor

Matt Masich

Photography

Joshua Hardin, Valerie Mosley

Design

Open Look Creative Team,

Advertising Sales

Marilyn Koponen, Lauren Warring

Subscriptions

Meagan Peil, Lindsey Schaecher, Janice Sudbeck, Azelan Amundson

Colorado Life Magazine

PO Box 430 • Timnath, CO 80547 (970) 480-0148

ColoradoLifeMag.com

SUBSCRIBE

Subscriptions are 1-yr (6 issues) for $25 or 2-yrs (12 issues) for $44. Please call, visit ColoradoLifeMag.com or return a subscription card from this issue. For fundraising and corporate rates, call or email subscriptions@coloradolifemag.com.

ADVERTISE

Advertising deadlines are three months prior to publication dates. For rates and position availability, please call or email advertising@coloradolifemag.com.

CONTRIBUTE

Send us your letters, stories, photos and story tips by writing to us, visiting ColoradoLifeMag.com or emailing editor@coloradolifemag.com.

COPYRIGHT

All text, photography and artwork are copyright 2022 by Flagship Publishing Inc. For reprint permission, please call or email publisher@coloradolifemag.com.

COLORADO DOESN’T HAVE a coastline. Besides that, we have just about every kind of terrain and ecosystem a state could want: mountains and plains, forests and deserts, and most things in between.

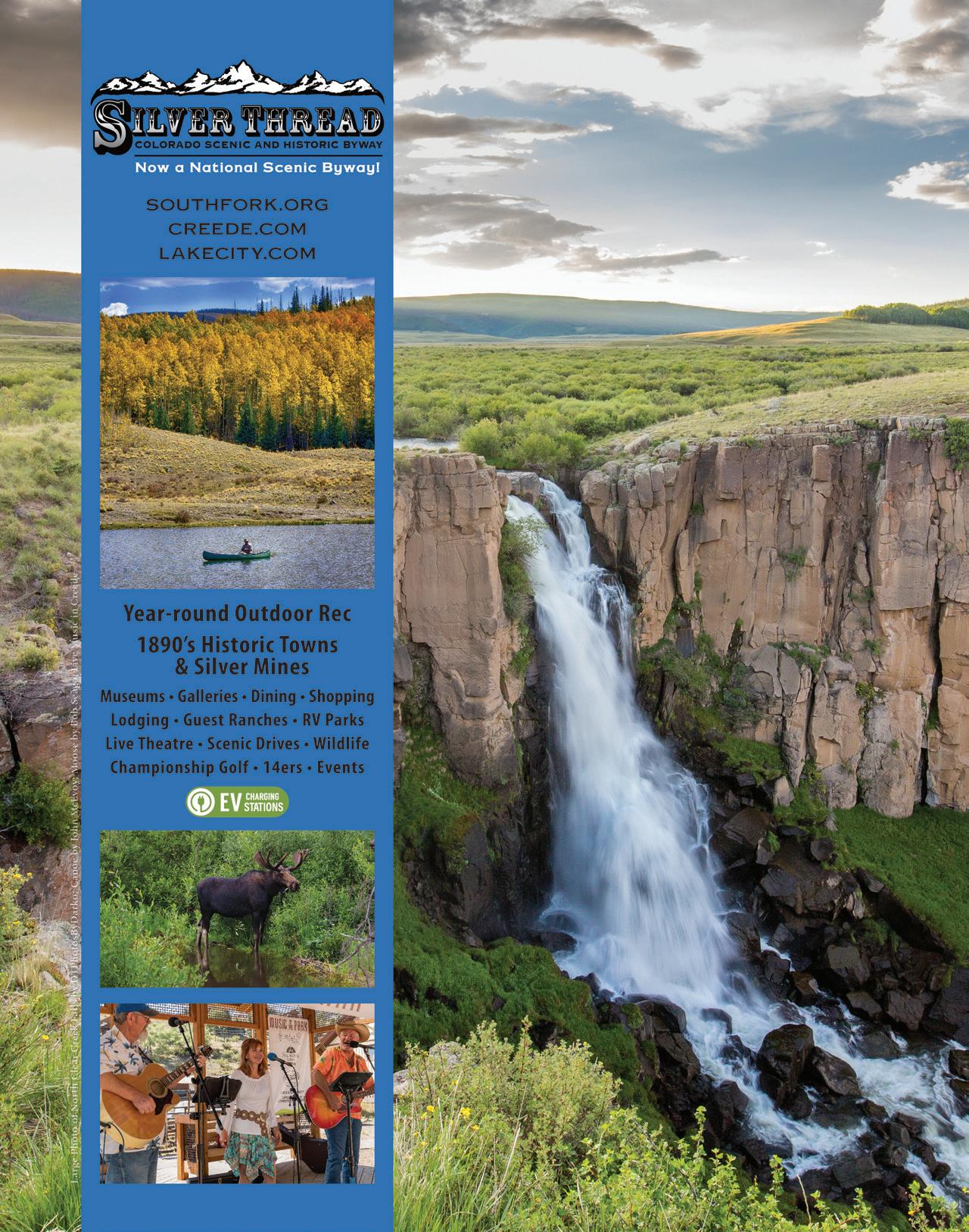

Given the abundance of Colorado’s natural beauty, it’s fitting that nature plays a starring role in the pages of Colorado Life. On page 20, we venture down to Baca County in the far southeast corner of Colorado to explore that region’s beautiful canyons – a surprise for anyone who still mistakenly thinks the Eastern Plains are uniformly flat.

But as fascinating as the natural world is, this magazine isn’t just about the beautiful places to be found throughout the state; it is also about the people who make living in Colorado such a rewarding experience.

In the decade Colorado Life has existed, we have profiled people in communities across the state, from Palisade to Trinidad, from Cortez to Julesburg. As different as these towns are from one another, I have found that getting to know people in each place has given me a fuller appreciation for what it means to be a Coloradan.

But towns aren’t the only type of community to be found in Colorado. There are also those groups of likeminded people who create their own communities, not based on lines on a map but on a feeling of common purpose shared by its members.

These self-made communities revolve around things as action-packed as drag racing or as peaceful as gardening. In this issue, we feature both.

Tom Hess’ page 52 story focuses on racers at Bandimere Speedway near Morrison. Known in the racing world as Thunder Mountain, the drag strip at Bandimere is ordinarily reserved for professional drivers who reach truly mind-blowing speeds – last year, pro driver Brittany Force set a track record of 326 mph, completing a quarter-mile in just 3.717 seconds.

But on Wednesday nights, Bandimere opens its track to amateur drag racers. Ordinary Coloradans with a passion for hot rods gather here to compete against each other for bragging rights. The crowd is a cross-section of Colorado: Drivers include young couples, father-son duos and grandmothers. The same faces show up again and again, kindling camaraderie amid the competition.

On page 40, you’ll find Colorado Life staffer Valerie Mosley’s story on Mulberry Community Gardens in Fort Collins. The project kicked off when Lorraine Dunn opened her backyard as a garden to anyone who had or hoped to acquire a green thumb. The garden’s ostensible purpose is to grow vegetables, but to the volunteers who gather to work this acre of earth, the most important thing cultivated here are friendships.

Valerie uses her storytelling talent – both as a writer and photojournalist – to capture the relationships that blossom at the garden. She has firsthand experience with this, having joined the gardening crew in 2016. At the time, Valerie was new in town and, though she didn’t initially realize it, longed for the type of community the garden provided. Today, Mulberry Community Gardens is an integral part of her life.

What appeals to me about stories like this is that you don’t need to have a pre-existing interest in the subject matter, be it fast cars or veggies. As with all Colorado Life stories, all you need is an appreciation for the experience of being alive in Colorado.

Matt Masich Editor editor@coloradolifemag.com

Diagonal inspiration

India H. Wood’s story of her Colorado diagonal adventures was one of the best stories I’ve read in Colorado Life (“Going Diagonal,” May/June 2022). Long ago, I drew diagonal lines on the Colorado page of my U.S. Atlas just to see where the approximate “heart” of Colorado lies. My lines indicated a location somewhere between Hartsel and Lake George.

As I followed Wood’s itinerary, I found that she, indeed, passed near Lake George, right about where my lines fell. As I read her fascinating account, I found myself yearning to walk beside her, but only along the flat stretches, I’m afraid. I look forward to her next article about hiking the diagonal from Julesburg to the Four Corners. Congratulations, India H. Wood. You are an inspiration.

Vaughn Neeld Cañon City

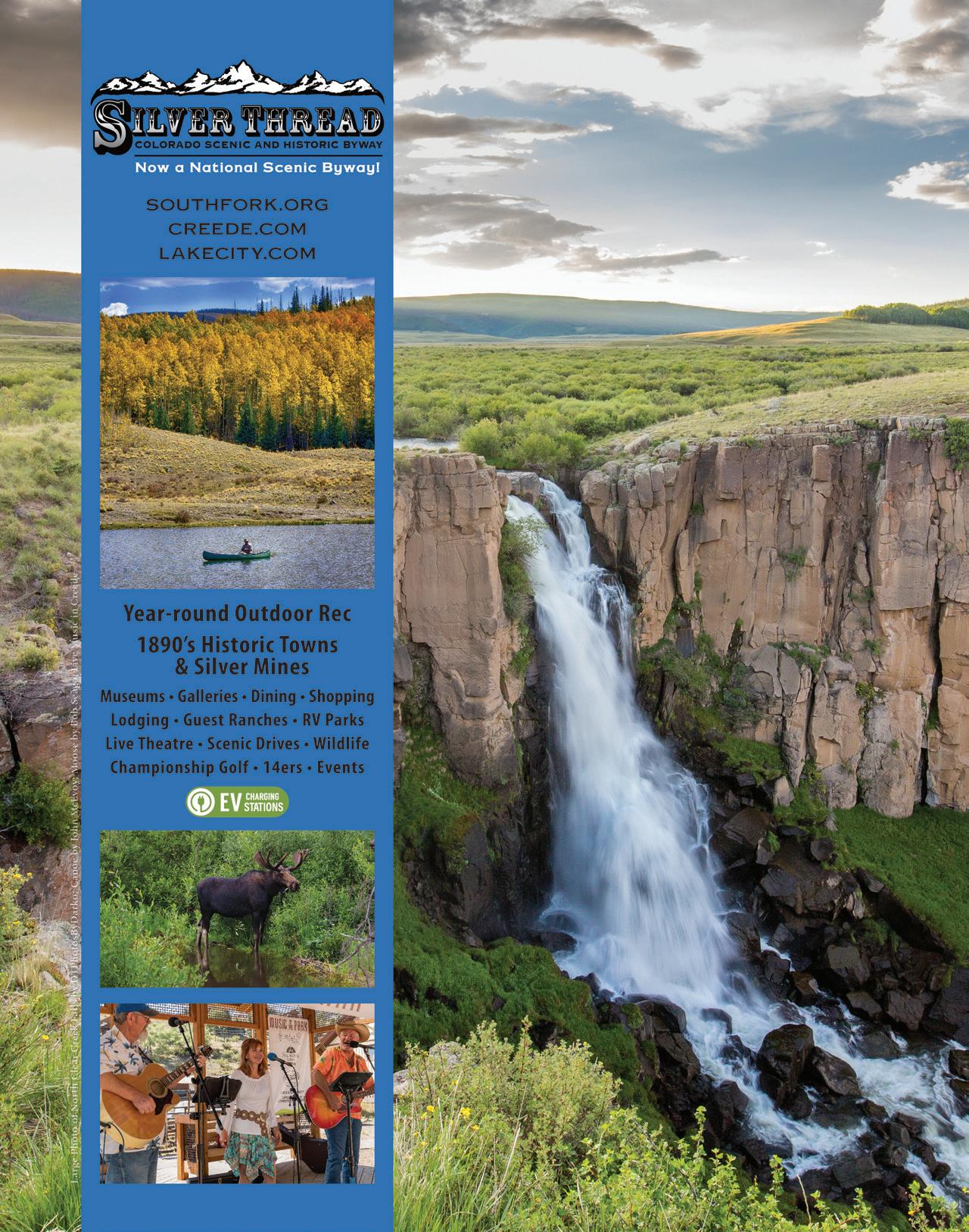

Many byways to travel

I look forward to receiving every issue of Colorado Life and enjoyed the May/June 2022 issue, especially the article about the Silver Thread National Scenic Byway (“Summer on the Silver Thread”). I have fond memories of living off the byway near Powderhorn and Gunnison, and of going helicopter backcountry skiing near Lake City when I was working for the National Park Service at Curecanti National Recreation Area in the early ’80s.

When I lived near Powderhorn, I’ll never forget the time I got a note from the mail person saying I had a package down at the Powderhorn Post Office, which was located in the local general store. I went to the post office and said that there was a package for me, and before I could even give my name, I was greeted with a friendly, neighborly, “Oh, you must be Tim,” and was handed the package. Nothing like rural living!

In mid-May, I had a chance to drive the Silver Thread Byway for the first time in many years. It brought back fond memories. I am still awestruck by the beauty and history of this part of the state. Colorado has 26 historic and scenic byways, 13 of which are national scenic byways, including the Silver Thread. I serve on the board of one of Colorado’s other national

scenic byways, the Lariat Loop National Byway west of Denver. I would encourage Colorado Life readers to explore all of our amazing byways.

Tim

Sandsmark Conifer

Having lived in Lake City a couple of years, I want to comment on other aspects of the Silver Thread Byway. When in Lake City, on a short drive around Lake Cristobal, a person can see moose and sometimes elk. The not so faint of heart can rent a Jeep or UHV and drive over Cinnamon Pass, with a short stop at American Basin, to view the wildflowers, then continue over the pass to Animas Forks, a mining ghost town. After a short tour and a potty break, you can continue back to Lake City via Engineer Pass. This is a spectacular drive, and the views are priceless.

The next stop on the byway, after North Clear Creek Falls, would be the Headwaters of the Rio Grande River, a pullout and fantastic view. Then on to Freemon’s General Store for a fantastic hamburger and bowl of ice cream. Then to Creede and South Fork. I can only say this is one of the most spectacular drives through the San Juan Mountains.

Joe Beakey Poncha Springs

Happy birthday, Colorado Life, and congratulations on a job well done. Your March/April 2022 issue brought back memories of so many wonderful issues

that I just had to go back and review all 10 years of your production.

I saw the very first May/June 2012 issue on a newsstand as I was walking out of a local convenience store. I was in a hurry, but I got halfway across the parking lot and dashed back to purchase the magazine. I have been a faithful reader from day one. I am a proud Colorado native and totally infatuated and passionate about this state. Every issue you produce fuels that fire even more. The articles are brief, informative, sensitive and cover a plethora of topics, and the photography is always stunning.

Even though I haven’t stood at the survey markers on each corner of Colorado as Matt Masich and Joshua Hardin did, I sometimes think I have seen just about all there is to see in Colorado. When my new issue arrives, I find something I have missed or relish a great memory of places I’ve been. Thanks to each and every member of your staff.

Joan Fields Brighton

The photographs by Dan Walters in the March/April 2022 issue’s “More than Mallards” were stunning. I especially liked his capture of the hooded merganser preparing its meal of crayfish. Ever since I moved to northern Colorado more than 30 years ago and saw the American white pelicans that frequent our area, I have loved seeing the amazing variety of water birds that occur in Colorado.

Mary Dubler Windsor

Despite being a longtime Colorado resident and frequent Utah visitor, I never fail to learn from both Colorado Life and Utah Life about places and attractions I hadn’t visited and, in many cases, hadn’t known of. I appreciate both magazines not only for my own information and pleasure, but also because they serve as crucial resources for the regional travel podcast I narrate weekly for visually impaired listeners to the Audio Information Network of Colorado (aincolorado.org).

Every issue has many articles fitting the podcast perfectly, and our listeners as well as I appreciate the wealth of vicarious travel we gain from them. And though narration doesn’t do them justice, photo spreads such as March/April 2022’s “More than Mallards” are always a joy to see. Congratulations on Colorado Life’s 10th anniversary, and best wishes for many more years in print for all your publications.

Don Deane Boulder

The Breckenridge article brought back some childhood memories from the late ’60s (“Boston to Breckenridge,” March/ April 2022). My uncle Jack had an A-frame cabin in the woods above Breckenridge near an old, abandoned mine. We would hike to the mine, and my mom and dad would rockhound while my brother and sister and I would explore, chase the chipmunks and skip rocks across the pond – classic mischief.

I remember the hippies living in the mine office had a six pack of beer cooling in the creek. Seems to me there were lots of hippies in Breckenridge those days. My wife and I went to Breckenridge a couple of years ago, and it seems like the condos,

cafes and boutique shops have taken over now. I am a flatlander from Amarillo and really enjoy your magazine from a landscape that is more three-dimensional than the Texas Panhandle.

Layne

Kirk Amarillo, Texas

Congratulations on 10 years! I have every issue, and they are in numerical order in manila envelopes. I can fit two years into my envelope. My daughter knows where they are and will get them when I’m no longer living.

When the March/April 2022 issue arrived, I set aside the things I’d planned to do and instead read the issue from cover to cover. I enjoyed the ducks, the bits from the back issues, the article about Glen Eyrie and the Editor’s Choice photo. Thanks for telling us about our state.

Myrna Dooley Pueblo

I always enjoy Colorado Life. The January/ February 2022 issue had an article regarding a new musical about Rattlesnake Kate. I was fascinated and had never heard of her. Because of your article, I was able to get tickets at DCPA to see the musical.

I invited my sister, who knows Colorado history forward and back. She filled me in on a lot of the details and even took me on a drive to the area where Kate lived. We both enjoyed the musical. The way the story of this strong woman was told touched us more deeply than we could have imagined. Thanks to your article we didn’t miss out on this wonderful experience. Thank you.

Marta Matsuno Brighton

SEND US YOUR LETTERS

We can’t wait to receive more correspondence from our readers! Send us your letters and emails by Aug. 1, 2022, to be published in the September/ October 2022 issue. One lucky reader selected at random will receive a free 1-year subscription renewal. This issue’s winner is Tim Sandsmark of Conifer. Email editor@coloradolifemag.com or write by mail to PO Box 430, Timnath, CO 80547. Thanks for reading and subscribing!

by LISA TRUESDALE

A 60-foot Japanese pagoda might seem out of place standing in a Longmont park. After hearing the story behind the Tower of Compassion, though, the location makes perfect sense.

Goroku Kanemoto wasn’t the first passthrough traveler to be so taken with Colorado that he decided to stay, and he surely wasn’t the last. Yet when the Japanese immigrant from Hiroshima hopped off his Canada-bound train in Denver in 1908, it was a split-second decision that would one day impact the city of Longmont.

In 1916, Goroku married Setsuno, also from Hiroshima, and they eventually settled in Longmont to raise their family, and to grow sugar beets and vegetables. The Kanemotos faced their share of adversity; Goroku was killed in an auto accident in 1935, and all three children dropped out of school to help their mother on the farm.

One hardship they didn’t have to suffer, however, was one faced by some 120,000 other Japanese Americans – being sent to internment camps during World War II. The family remained in Longmont, with Goruko and Setsuno’s two boys, Jimmie

and George, marrying the Miyasaki sisters, Chiyoko and Jane, from Lafayette. This familial partnership went on to farm 350 acres south of town, selling produce at their Fresh-Way Market on South Main for nearly 30 years.

After developing some of their farmland into the Southmoor Park neighborhood in the 1960s, the Kanemotos donated surrounding land to the city to use for an elementary school, a fire station,

a church, the Longmont Buddhist Temple and Kanemoto Park, named in honor of their father. Then, in gratitude for the city’s kindness and acceptance over the years, they also donated the tower, which stands majestically on the south side of the park. It’s quite a sight to see, up close or from a distance – although there’s no going in, since it’s built on a steel skeleton with no accessible interior.

Before he died in 2006 at age 89, Jimmie was often asked to speak to schools and organizations about the treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II. “The greatness of this nation lies in its diversity, in its differences and in the fact that we come from many different lands,” he said in one of his powerful speeches.

The Tower of Compassion’s five levels represent the levels of compassion: love, empathy, understanding, gratitude of all things and giving selflessly of oneself. Built in 1972, it marks its 50th anniversary this year.

by TOM HESS

High above the city of Trinidad rises Fishers Peak, the namesake and most prominent feature within one of Colorado’s newest state parks. Someday, as many as 17 miles of singletrack mountain bike trails will crisscross the park, requiring skilled labor working several years through rough, steep terrain to build them.

The man tasked with training the next generation of Trinidad trail builders is Tony Boone of Timberline Trailcraft.

Trinidad State Junior College hired Boone to spend three years instructing students in the art and science of sustainable trail planning, design, construction and maintenance. His 2021 classes of four to 12 students used the tools of the trail-building trade – wildland firefighting hand tools known as Pulaskis (a combination axe and hoe) and McLeods (a combination rake and hoe), as well as chainsaws and pickaxes – to create a safe corridor through ponderosa pine and juniper.

Boone’s lesson emphasized the need to “divide and conquer” the flow of water. Rainfall gains enough momentum on steeper slopes to severely erode a trail and render it unsafe, so Boone teaches his students to create drainage every 75 to 100 feet to lead water away from the trail.

One of Boone’s 2021 students is Casey Fritzsching of Cokedale. Fritzsching hopes that Boone’s class will help him get a trail-building job at Fishers Peak State Park.

“I want to be a part of building that mountain,” Fritzsching said. “I’ll definitely be knocking on their door and ask, ‘So where’s the pickaxe?’ ”

Boone called his students “The Dirt Brothers and Sisters,” because they spent so much time in hot, dusty conditions, working to improve trails at Trinidad Lake State Park and elsewhere. It’s rare for trail builders to spend nights at home in their own beds, Boone said, so a bond develops. In his four decades working on trails, Boone said he’s spent an aggregate of just one decade at home. “It’s a sacrifice on your family’s part,” Boone said. “It’s a sacrifice on your part. What becomes your community, what becomes your family? Here are my brothers and sisters.”

by LISA TRUESDALE

A desk. A pair of sneakers. A bicycle. Without context, they seem ordinary. Yet in the new book Becoming Colorado: The Centennial State in 100 Objects, William Wei gives them all a starring role in his chronicle of the state’s history, beginning with a stone spear point dating back about 13,000 years. Wei, a CU Boulder history professor and former Colorado state historian, was lead advisor on the History Colorado exhibit “Zoom In: The Centennial State in 100

Objects.” For the book, Wei paired the exhibit’s 100 objects with short essays, placing them into historical context.

Choosing just 100 objects from History Colorado’s vast collections was a challenge. Each artifact had to be small enough for museum display, but it also had to highlight one of three things: an important aspect of Colorado culture, a recurrent pattern in Colorado life, or a moment in Colorado history when people made choices that define us today.

The desk makes sense, then; it belonged to Ute Chief Ouray, given to him by the U.S.

government in 1876 for his help brokering treaties with his people. The sneakers were Wellington Webb’s, worn during his successful “sneaker campaign” for Denver mayor in 1991. And the bicycle? It’s a Mauro Special from 1893, a women’s model complete with a skirt guard.

“Men were opposed to women riding bicycles … the conventional wisdom was that women needed men’s supervision in all things at all times,” writes Wei. But women joined the cycling craze anyway. The newfound mobility of cycling gave women a feeling of independence and autonomy, he writes. “Suffragette leaders astutely realized that the bicycle was a vehicle for personal and political empowerment.”

Becoming Colorado: The Centennial State in 100 Objects by William Wei University Press of Colorado 268 pp, paperback, $33

Soar high above the clouds and gaze down on breathtaking views. Gateway Canyons Air Tours specializes in providing lasting memories that will delight, dazzle and inspire your imagination. Taking you beyond the expected and up to a higher place. Come see for yourself.

Motels with quaint names and historic neon signs abound on this stretch of West Colfax Avenue in Lakewood, yet there’s something about the Big Bunny Motel that stands out.

Eagle-eyed observers might note its sign seems to have been altered at some point. The inn opened in 1952 as the Bugs Bunny Motel, and it bore that name for the entire 45 years it took Warner Bros.’ legal department to catch wind of the blatant copyright infringement.

Rather than getting a completely new name and paying for a new sign, the motel simply tweaked a few letters to a moniker less likely to incur lawyerly wrath.

by MADDIE CÔTÉ

Will Reynolds makes tree nets for a living. Woven from paracord strung between trees high above the ground, his tree nets resemble human-sized spiderwebs or wildly overgrown hammocks.

Reynolds started building them as a hobby in high school, when his California cousin “Hippy Pete” introduced him to tree nets as the perfect place to lounge outdoors. Now 30, Reynolds runs his own thriving tree net business in Durango, where he is known around town as TreeNet Willy.

He looks for two key criteria when picking a spot for a tree net: It must have an epic view, and it must be hidden enough to relax deeply and uninterrupted. He has spun at least 10 “rogue” nets on the mountainous outskirts of Durango. Though they’re on public land, his nets are well concealed in the tree canopy, so word of mouth is the best chance of finding one. Anyone lucky enough to stumble upon a tree net is wel-

come and encouraged to climb in.

These kaleidoscopic webs vary greatly in color, pattern, size and height off the ground. Some feature a clever backrest perimeter, and many glow in psychedelic colors under black light. Often hanging beside the net is a mason jar containing sheets of paper – a sort of trail register listing hundreds of visitors’ names, places of origin and visiting dates.

Reynolds’ passion has become his fulltime job. He’s hired to install nets at Airbnbs, resorts, playgrounds and music festivals worldwide. While Durango remains his basecamp, far-flung assignments include Bali, Iceland, Belize – even the animal safari of Doc Antle from TV’s Tiger King, where he rigged a net for chimpanzees. A single net requires thousands of feet of paracord, which Reynolds and his small crew haul through airports in large duffel bags. Instead of using ladders to begin a design, Will’s workers are also skilled climbers and slackliners, working

suspended like monkeys themselves.

Reynolds says his mission is to provide people with “easy adventures” and new ways to appreciate and connect with nature. Sure, a rock climber enjoys incredible vistas, he says, but he prides his nets on offering inspiring views to even the least adven-

turous person. As community spaces, his tree nets are woven into the identity of Durango, where TreeNet Willy is something of a legend. Most locals have either heard of his nets or hung out in one firsthand. And as he continues to weave his wonders across Colorado, his legend only grows.

Test your knowledge of

by BEN KITCHEN

1 The Gunnison Pioneer Museum has on display a cane made by what notorious Coloradan while he was imprisoned in the 1880s? Humorously, he lends his name to a dining hall at CU Boulder.

2

Remnants of the Wild Westlike Old Barn Knoll and Frazer Meadow can be found in the state park named for what canyon that is not located anywhere near San Francisco?

3

In 1886, 26 years before the event that earned her a nickname, a certain woman living in Leadville married a man named JJ, who went on to strike it rich in the mining industry, leading to their move to Denver. Who was she?

4 As the first transcontinental railroad was interrupted by the Missouri River, the nation’s first continuous railroad connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific was finished in 1870 at what site near Strasburg? Its alliterative name includes a Native American tribe.

5

The Anschutz Collection at the American Museum of Western Art includes several works by what famous bronco-busting artist whose surname was already well-known thanks to his cousin’s namesake firearms company?

6 Which legendary Wild West figure is not buried in Colorado?

a. Buffalo Bill

b. Kit Carson

c. Doc Holliday

7

Colorado’s Gold Rush, which sparked mass migration to the region, started at the tail end of what decade?

a. 1840s

b. 1850s

c. 1860s

8

Not far outside of Marble is the picturesque Crystal Mill, built in 1892 to aid in the mining of what metal?

a. Silver

b. Gold

c. Lead

9

Operating since 1881, the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad takes passengers through the heart of what national forest?

a. Rio Grande

b. San Juan

c. Uncompahgre

10 Just northeast of Gunnison is Frenchy’s Cafe, one of the few remaining establishments in what bygone mining town that shares its name with a Kevin Costner film?

a. Gunrunner

b. Silverado

c. Tin Cup

11

Along its course from Missouri to Oregon, the Oregon Trail took travelers through Colorado.

12 Central City honors brothel owner turned hospital runner Madam Lou Bunch every June in a celebration that includes racing beds on Main Street.

13

Chosen in 1861, Colorado Territory’s first capital city was Colorado City, which is now a neighborhood of Colorado Springs.

14

Centering around African Americans in the Wild West, Denver’s Black American West Museum is based in the former home of Bass Reeves, Colorado’s first African American deputy U.S. marshal.

15

Opening in the 1890s, the Cripple Creek & Victor Gold Mine is still one of the five largest gold mines in the country.

No peeking, answers on page 68.

EXPERIENCE the splendor of the Rockies at Aspen Winds. The secluded setting along Fall River, among the aspen and pines, offers a relaxing atmosphere. Aspen Winds is located minutes from Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park.

story and photograph by JOSHUA HARDIN

MOUNT

over Leadville like a billowing cloud, beloved by residents of Colorado’s highest city as a constant reminder of the pride placed in local peaks.

Massive is the third-highest peak in the contiguous United States and second-highest in Colorado. The U.S. Forest Service lists Massive’s elevation as 14,421 feet, just 12 feet below the reigning crown of Colorado, Mount Elbert, 5 miles south.

Massive aficionados who believed the elegantly expansive mountain was more deserving of the state’s highest peak honor than its Sawatch Range neighbor stacked rocks into a cairn at its summit hoping it would rise 13 feet to eclipse Elbert’s elevation. Elbert enthusiasts countered by climbing Massive and tearing down the cairn. It’s unclear how many times the cycle of cairn construction and destruction continued, but the opposing teams eventually tired, and cairn building ceased.

By 2002, the U.S. Geological Survey promised a revision of elevations due to decades of improved cartographic accuracy, which again gave Massive’s supporters hope. When the results were released, the USGS raised the peak’s elevation estimate by 7 feet. However, Elbert’s height was increased by the same amount – and the USGS refused to recognize cairns in their calculations.

Massive’s elongated profile is an impressive presence above Lake County’s mining districts regardless of its silver medal status. Massive has five summits above 14,000 feet along a 3-mile-long ridge, resulting in more area above 14,000 feet than any other mountain in the contiguous states, narrowly edging out Washington’s Mount Rainier in that category.

Baca County is home to fascinating hoodoos, petroglyphs and wildlife

story and photographs by

JOSHUA HARDIN

TUCKED INTO COLORADO’S southeastern corner are unique environments first-time visitors might not expect to see on the Eastern Plains landscape. Baca County’s wild wonders include two canyons carved into the prairies of Comanche National Grassland, delighting hikers and historians alike, as well as a historic reservoir now acting as a refuge for avian species and the birders who seek them. We visited these three areas to explore the natural diversity each contains.

A two-mile hiking trail along Carrizo Creek, 27 miles west of Campo, accesses

one of the few permanent water sources of Comanche National Grassland. The east fork of Carrizo (meaning “reed” in Spanish) Creek flows through a small canyon lined by juniper and cottonwood trees. A picnic area on the canyon rim provides a sheltered trailhead perfect for planning area exploration.

American Indian petroglyphs, including many “zoomorphs” depicting animals, are found pecked into the rock along the canyon’s interior Dakota sandstone walls. Early inhabitants drew inspiration from the canyon’s plentiful inventory of wildlife, which is best seen in the early morning hours after sunrise or the few hours preceding sunset. Found here are birds

rarely spotted in other regions of Colorado, such as black-chinned hummingbirds, ladder-backed woodpeckers, Eastern phoebes, Cassin’s kingbirds and Mississippi kites.

Bullsnakes and collared and horned lizards sun themselves on the rock walls adjacent to the trail, while snapping and softshell turtles, bullfrogs and channel catfish live beneath the creek’s waters. The water levels can rise 6 feet or more during large rainstorms causing flash floods. Aquatic life disperses downstream as the channel floods and connects small ponds and normally barren areas along its course, spreading biological diversity to this otherwise hot and dry ecosystem.

Comanche National Grassland’s Picture Canyon has strange-looking hoodoo rock formations. Paleo-Indians lived here 12,000 years ago, followed more recently by Plains Indians. The rock art left by early inhabitants gives Picture Canyon its name.

A canyon about 17 miles southwest of Campo proves people thrived in an inhospitable setting for thousands of years. Paleo-Indians from 12,000 years ago through post-archaic cultures 400 years ago inhabited Picture Canyon and left an indelible mark on their homeland. Stone tools and projectile points found here indicate Paleo-Indian hunters once roamed the area, while rock art chiseled and painted by Plains Indian tribes in more recent centuries gives the canyon its name.

More than 13 miles of trails lead to the Indian art, which includes depictions of a horse with elegant flowing lines and what appears to be a soldier with X-shaped belts crossing his chest. Other attractions are rubble remnants of homesteads built by Anglo settlers, a natural arch and strange stone hoodoo formations.

Routes can be difficult to follow as trails fade into canyon underbrush and the juniper-dotted sandstone rim, while signage is sparce. Research and good maps are recommended to find each landmark. The National Forest Service also gives guided tours of a gated Crack Cave during the spring and fall equinox to visit a site where inhabitants marked the sun’s position on those dates.

Visitors should take care to preserve the canyon’s ancient cultural resources. Archaeologists use fragile relics from tipi rings to pottery sherds as clues to reconstruct the region’s ancient life. If destroyed or removed, the information artifacts might reveal is lost forever.

Picture Canyon shares Carrizo Canyon’s wildlife diversity. Birds like Bullock’s orioles, scaled quails, blue grosbeaks and several species of towhees, wrens and sparrows live here, while large mammals like pronghorn and black bear are even occasionally seen.

Picture Canyon hosts a variety of colorful flora and fauna, including a red flame skimmer dragonfly, a blue dayflower and a pink bush morning glory.

County residents completed an earthen dam about 17 miles north of Springfield on Two Buttes Creek in 1910 with horses, mules and hard labor. Designed to irrigate nearby farmlands, the project didn’t live up to expectations, as it provided water for only 3,000 acres. Colorado Parks and Wildlife bought the property in 1970 and stocked the lake with channel catfish, rainbow trout, largemouth bass, crappie and other fish.

While fishing and boating draw visitors, the area’s primary attraction is a wealth of both resident and migratory bird species. As the reservoir’s water level varies seasonally, high waters attract ducks and grebes, while shorebirds abound during low-water periods. Below the dam is a veritable wonderland of habitats, including extensive tangles of underbrush, tall cottonwoods, marshy

ponds and grassy areas. The rimrock habitat is among the best places in the state to find roadrunners.

A pond near the reservoir known as the Black Hole is a popular swimming spot, though it isn’t recommended to dive from the surrounding cliffs or swim alone or without a life jacket, as injuries and deaths have occurred here. The pool is, however, a photogenic oasis lined with tall cattails, lush cottonwoods and pink sandstone seen from its sandy shore.

While nearly all of the reservoir is located within Baca County, the namesake buttes are located just north of the line in neighboring Prowers County. Rising more than 300 feet over the plains, the buttes provide an impressive backdrop over the reservoir and are oc -

cupied by raptors such as owls, vultures and hawks.

First-time visits usually aren’t enough to explore the bountiful, off-the-beatenpath charms Colorado’s southeast corner possesses. In addition to the more con-

spicuous attractions, the prairie canyonlands conceal wonders not easily discovered, rewarding multiple visits. Because there is so much to enjoy, nature-loving travelers can’t wait for a chance to go back to Baca County.

A Salida father raised six children and grew a gemstone business on the steep slope of his Mount Antero aquamarine mine

story by TOM HESS

photographs by H. MARK WEIDMAN

THE THIN AIR at 12,500 feet is working everybody’s lungs hard, but Brian Busse is at ease, patiently dragging a garden tool through loose gravel. He’s looking for the blue glassy sparkle of aquamarine, Colorado’s official state gemstone, a coveted relative of emeralds in the beryl family of minerals.

And there it is, an aquamarine the size of a pebble. Busse picks it up, rolls the gemstone between his fingers, one eye squinting as he holds it up to the sun. He figures he can fashion it into earrings that will pay for dinner, or at a least “a side of fries at McDonalds.”

He pockets it and continues digging, the gravel he’s pushed aside tumbling down a 45-degree slope. No need for heavy machinery and dynamite up here; gravity clears away the degraded granite from his hand-dug quarry on the steep side of Mount Antero near Salida.

Busse, a self-described “gem tracker” and former star of the Weather Channel TV show Prospectors, calls his claim the Thank You Lord Aquamarine Mine, for reasons of faith and family.

“I’m thankful for the beautiful stones and a beautiful place to work with my family,” Busse said. “The Lord allowed me to do that job safely, without too many injuries.”

BUSSE AND HIS WIFE, Yolanda, raised their six children on the mountainside, camping and homeschooling there for days at a time, some years for as much as 100 days. Sales of the gems they found provided for them the six months out of the year they were off the mountain and in Salida.

No one in the mountain community seemed to take notice or express alarm that six young children lived half the year above civilization. No one up there wanted anyone else to tell them what to do, and even if they offered advice, Busse says he wouldn’t have listened anyway. He wanted to make a living in Colorado nature, enough to provide for his family for “a long, long time.”

The family took truckloads of supplies to the basecamp, sought shelter and slept in a giant teepee made of tarps, and took showers in solar heated water drawn from Baldwin Creek. Now that they’re grown, five of the six Busse children still mine and sell aquamarine and other gems.

Approaching Medicare age, Busse

struggles with the lingering pains of his injuries. He has separated his sternum and both shoulders, and once snapped his Achilles tendon – 15 injuries in all, but no broken bones. The lingering pain doesn’t slow him down. There’s too much left to do. He estimates that he’s worked only 1 acre of his 20-acre claim, and that many billions of dollars of gems remain to be unearthed and sold.

As is well known to viewers of the Prospectors TV series, which ran for four seasons in the 2010s, Busse looks and sounds like an old-time gem prospector – bearded, weathered, straight-talking. You almost expect him to do a jig, kicking his legs, a jug of moonshine on his elbow, and the mountains echoing his holler at every new discovery. That’s not his speed today. He’s the tortoise, not the hare.

The Weather Channel had heard about Busse from other gem prospectors but had not yet committed to airing the program. They wanted to film Busse at the base of Mount Antero. The morning after the filming, the channel called to say it

wanted him on the show, and that because of his on-camera performance, the show would proceed.

Busse quit after four seasons, and the show was canceled. “I was open-hearted and open-minded,” but television “affected every relationship I had with everybody I knew – the good, bad and ugly. Everyone, all my friends on the show, were in competition with me for that lead role.”

He is now trying to sell his own show to Hollywood, spending time in Malibu reaching out to entertainment industry executives and selling his Colorado jewelry.

Busse fell in love with the Colorado wilderness when he caught his first rainbow trout as a child on a visit with his uncle at Red Feather Lakes near Fort Collins. He grew up in Iowa, where an illness kept him out of school for a year. He spent that year hunting, fishing and playing in the hardwood forest. The solitude of that year

Brian Busse welcomes visitors to join him on paid excursions to his Mount Antero aquamarine claim. Busse walks guests through the prospecting process and allows people to keep smaller gemstones they may find. Those interested can reach him by texting him their name and contact information at (719) 221-6730.

prepared him for Antero. He works his claim methodically and almost daily. It supplies him a steady income, but with the thought that a bigger payday might come. “You might be able to find a stone that’s a month’s or a year’s salary, or maybe something that you could retire on,” Busse said, matter-of-factly.

Others who want a quick buck come and go, or try to steal their way to riches. Busse says thieves – friends of his children

– took two stones from Thank You Lord worth $1 million. He reported the crime to the FBI and Colorado Bureau of Investigation, but he never recovered the gems. He doesn’t dwell on it.

“Revenge is God’s, not mine,” he said. “It’s better for me to focus on finding the next stone than worrying about the stones that were stolen from me.” Even so, the more time he spends on the mountain, the less likely thieves will take their chances.

BUSSE’S AQUAMARINE MINE is on a shoulder of Mount Antero, its 14,269-foot summit accessible by four-wheel drive. Low clearance vehicles should steer clear. County Road 277 rises from near Mount Princeton Hot Springs Resort and crosses Baldwin Creek several times on the way to his base camp. The creek runs several feet high after a rain or spring runoff; 277 meets County Road 278, which stops short of the Antero summit.

He drives his guests in a black “Darth Vader” Jeep Rubicon, modified by Rocky Mountain Jeep Rentals in Salida with a 6.5-inch lift bar for greater steering control. That helps with traction on the road’s large boulders. Busse takes it slow, but even at 3 mph, the passengers rock from side to side for the next hour.

As he drives, Busse eases the rough ride by explaining the road’s origin, the gemstones market, and his claim’s standing in the world. The U.S. government built the road to access beryllium, the rare metal that is useful in space programs and nuclear weapons. The world’s leading producers of aquamarine include Brazil and Pakistan, and lately, Vietnam. Busse’s gem field is third highest in the world, just below gem fields in the Himalayas of Tibet and the Andes of South America.

Once parked at his basecamp at 11,400

feet, Busse invites guests to start the hike up to his claim. On the 45-degree slope above tree line, he installed a nylon rope that climbers can grip as they struggle to gain secure footing in the loose, rocky talus.

At Busse’s worksite, between 12,000 and 13,000 feet, is a sweeping view of the Sawatch Range above Salida and Buena Vista. The basecamp below looks like the bottom of a great amphitheater, surrounded on all sides by 13er and 14er peaks. On this summer day, the sky is clear, no clouds on the horizon.

Busse remembers days when lightning strikes and thunder would cause avalanches. On one especially loud day, the amphitheater amplified the noise of 100 lightning strikes, followed by ball lightning, “which slowly moved through the trees, and blew up, BOOM!, right in a puddle full of mosquito larvae and dried it out,” he said. “We were all deaf for a minute.”

He sometimes intervenes to help others in trouble on Antero – helping drivers who roll their Jeeps and stopping bad guys who threaten others with guns and knives. He recalls four or five weapons encounters, each of which he de-escalated.

“I got in their faces and disarmed them, sometimes with force,” Busse said. “I was going to hurt them before they hurt somebody else. Most were smart enough to understand me and back off.”

Before mining on Antero, Busse displayed his fearlessness as a lead bouncer at a bar in Fort Collins.

There are no knives, guns, rolled Jeeps or mosquitos at the worksite this day. No ball lightning either. The amphitheater is quiet. Busse is seated, his legs sprawling over his lode. Guests from Austin lie above him on their bellies, scratching for their aquamarine lottery ticket. They find something less than the thieves stumbled upon, but they’re content.

“One of the pleasures of working in God’s country is that, for some people, it becomes a place where they can step back from society, let go, start to heal,” Busse said. He knows something about wilderness, and healing.

Busse will keep going up, despite the greed of Hollywood, the aches and pain of his injuries, and the hard work that taxes his heart, mind and soul. Mining is what he calls a “poor man’s life insurance” for his family’s financial future, but what gets him up the mountain is the fun he has with the people he cares about. “That’s the most important thing,” he said.

The rugged Sawatch Range rises in the distance behind Brian Busse, who uses a variety of hand tools to work his claim on the slopes of Mount Antero.

recipes and photographs by BY

DANELLE McCOLLUM

WHILE ICE CREAM can be enjoyed year-round, it comes into its own during the long, hot days of summer. Not only is ice cream a cool, refreshing antidote to the blistering sun, it comes in as many flavors as the human imagination can conceive. And as fun as it is to eat ice cream, it can be just as fun to make at home. Here are some of our favorite ice cream recipes to use in an ice cream maker.

A favorite summer drink is transformed into a cool summer treat. This pretty pink ice cream is pure refreshment. The ice cream is a little bit sweet, a little bit tart, and perfectly creamy and delicious.

In medium bowl, whisk together all ingredients until smooth. Cover and refrigerate for at least 1 hour, or overnight. Turn on ice cream maker and add milk/cream mixture to bowl. Mix for 15-20 minutes (according to manufacturer’s instructions) or until ice cream reaches soft-serve consistency. Transfer ice cream to air-tight container and freeze at least 2 hours, or until firm.

1 cup whole milk

3/4 cup granulated sugar

2 cups heavy cream

1 tsp vanilla extract

Pinch of salt

1/3 cup pink lemonade concentrate, thawed

Zest of one lemon

Pink or red food coloring (optional)

Serves 6

Coconut milk and fresh pineapple come together with a hint of lime in this creamy, cool dessert that is perfect for summer. The flavor is similar to a piña colada, without the rum. Because this recipe doesn’t use actual dairy, it might be more accurate to call it a sorbet.

Place all ingredients in blender and process until smooth. Refrigerate mixture until very cold, at least 3 hours. Remove from refrigerator and whisk mixture to blend. Pour into ice cream maker and freeze according to manufacturer’s instructions. Store in airtight container in freezer until ready to serve.

3 cups fresh pineapple, cubed

1 13.5-oz can full-fat coconut milk

2/3 cup sugar

2 Tbsp lime juice

1/2 tsp vanilla extract

1/2 tsp coconut extract

Serves 6

Like two delicious desserts in one, this creamy vanilla cheesecake ice cream comes with a homemade blueberry swirl. The cheesecake ice cream base is versatile – depending on what one adds, it can be used to make nearly any flavor of cheesecake ice cream.

In medium saucepan, bring blueberries, 1/3 cup sugar and lemon juice to boil over medium heat. Cook 8-10 minutes, or until blueberries have burst and mixture has thickened. Chill in refrigerator until cold.

Beat cream cheese and 1 cup sugar with electric mixer until smooth. Beat in cream, milk and vanilla extract. Chill mixture for several hours, until cold. Pour ice cream mixture into ice cream maker according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Pour half of ice cream into freezer-safe container, top with half of blueberry mixture. Top with remaining cream and remaining blueberry sauce. Run knife through ice cream to swirl blueberry mixture. Cover and freeze 2-3 hours, or until firm.

Blueberry Swirl

2 cups blueberries

1/3 cup sugar

1/2 tsp lemon juice

Ice Cream

8 oz cream cheese, softened

1 cup sugar

2 cups heavy cream

1 cup milk

1 tsp vanilla extract

Serves 6

The editors are interested in featuring your favorite family recipes. Send your recipes (and memories inspired by your recipes) to editor@coloradolifemag.com or mail to Colorado Life, PO Box 146, Timnath, CO 80547.

Green-thumbed volunteers cultivate relationships at Fort Collins’ Mulberry Community Gardens

story and photographs by VALERIE MOSLEY

glows through a spray of water droplets falling on several rows of raised beds. Lorraine Dunn tries not to get soaked as she adjusts one of the tall tripod sprinklers irrigating the 1-acre backyard-turned-community garden in northwest Fort Collins. She catches a whiff of tomato vines on the breeze as she tries to rinse the sticky yellow tomato tar stains off her fingertips. This water from the Poudre River arrived here via an irrigation ditch originally built in 1861.

Irrigation season starts in late May, when there’s enough mountain snowmelt to divert. At 5:15 p.m. about twice a week in the summer, Lorraine or a volunteer takes a quarter-mile walk along the Pleasant Valley and Lake Canal, through neighbors’ gates and past the Poudre High School baseball fields, moving plywood boards to change the flow of water toward Mulberry Community Gardens.

For more than a decade, Mulberry Community Gardens has fostered friendships and built community by providing a space where all are welcome to learn how to grow food by pitching in. The nonprofit’s goal is to eliminate the barriers of expense, knowledge and land for would-be gardeners through a communal approach to growing.

Instead of renting individually managed plots, volunteers share the work of maintaining more than 50 raised beds, a flock of chickens and two goats. There’s no application or fee to join – just show up during volunteer hours. It’s a gathering place and a creative space for all kinds of projects. The unofficial motto is, “I don’t know. Let’s try it!”

At Mulberry, one can find more than 40 varieties of heirloom tomatoes, an obscure melon called “collective farm woman” and purplish-red Chinese beans that grow 3 feet long. But for most regulars, including

current board president DeeDee Wright and her husband, Lance, “it’s never been about having fresh vegetables. It’s always been about the people.”

I first found my way there in the summer of 2016, needing a release from the demands and disappointments of work. I missed my backyard in Missouri, where my husband and I had spent most of our free time with an ambitious vegetable garden, chickens and a mulberry tree. I needed to occupy my hands and quiet my mind.

My identity was still so wrapped up in my photojournalism job that I was more comfortable meeting people in that capacity, so I brought my camera and notebook, intending to create a photo story. I never got that story published, but I kept coming back to the garden with my camera.

Over the next year, my burnout at work intensified. I made the heartbreaking decision to leave what was supposed to be my dream job for self-employment.

On my last day, I took my leftover garden-themed farewell cake straight to Mulberry Community Gardens.

During most volunteer hours, I would pitch in on the weeding for a little while and then wander around the garden photographing a little bit of everything going on. Lorraine especially appreciated the photos I sent for the email newsletter.

I crouched down for a low angle on the steam rising from the compost while Javier and Lance took turns tossing forkfuls of decomposing kitchen scraps and fall leaves into the second compost bin. In the north beds, I used my widest angle on Jilli

instructing 20 volunteers from Colorado State University on preparing beds to plant peppers. I captured Julie and Alicia’s delight feeding armfuls of bindweed to the goats, and DeeDee teaching herself to braid garlic. I made chicken mugshots to help everyone learn their names. I documented the harvesting of vegetables and mulberries being shaken from the garden’s namesake tree.

As the sun set, I photographed the evening’s bounty, styled by Maria for maximum beauty, just before the colorful haul was divvyed up between the volunteers and the leftovers boxed up for the food bank.

THIS GARDEN EXISTS because of the vision and efforts of Lorraine Dunn, who wasn’t much of a gardener when the vision took hold. She’s freethinking, hardworking and fun-loving.

She thinks of people in terms of dog breeds. “Jeffy, he’s our garden Irish setter. He is absolutely enthusiastic, energetic, wants to do everything,” she said. “Jim is probably a heeler.”

Like the three little dogs Blazer, Bailey and Pesty Underfoot she took in from a carnie in California, every goat and many of the chickens over the years have been rescues.

“What can I say?” she said. “If it eats, I feed it.”

One rescue chicken, an Araucana named Sophia, was picked on so much by the existing flock that Lorraine took her home to live in the house for the winter. Sophia actually died of old age instead of by dog or racoon.

“That’s my dream for all of them,” Lorraine said.

She and her partner, Erich Stroheim, grandson of silent film actor and director Erich von Stroheim, will celebrate 20 years together this year. They met folk dancing at the Empire Grange next to the garden, where they still meet up with their folk dancing group every week.

When the house next door to the Grange went up for sale, Lorraine immediately started trying to convince Erich to buy it as a rental property. “I was like a chihuahua nipping at his heels until he succumbed,” she said.

He bought it before the neighbor who had always wanted the property even saw the sign. Erich liked the house because it reminded him of the 1950s house where he was raised. And they both liked its proximity to the Grange.

The huge yard and water rights had Erich thinking it would be a great spot for a community garden. The idea took hold for Lorraine when Erich’s neighbor looked at the backyard and said the same. They immediately sat down for two hours and made a list of all the things they would need. The top priority was people with knowhow.

“If we have a bunch of people here, and everyone has a little bit of knowledge,

we’re there,” Lorraine said. “We have 100 percent knowledge.” For Lorraine and Erich, the vision was always more about the community than the gardening.

picnic tables near the mulberry tree, where everyone is prepping their potluck contributions.

Retired sociology professor Mike Lacy pours a round of mulberry margaritas with the syrup he made from berries picked last week. He turns to Sam and Alicia, “You know, really, we’re a drinking club with a gardening problem.”

“Mike!” Julie laughs as she tosses together a freshly harvested salad. “You always say that.”

Javier checks the hot wings on the grill and adds the pizza boats DeeDee made by adding pizza toppings to hollowed-out zucchinis cut lengthwise. Lorraine unwraps a discounted wedge of brie from King Soopers.

“My hummus is a Woo-hoo, too!” Maria squeals as she sets corn chips and hummus on the picnic table, using the words on the red-and-yellow markdown stickers.

“Woooo-hoooo!” Lorraine replies, raising her hand for a high five.

Maria found the garden after moving to Fort Collins from Chicago where she has deep roots. Riding her bike down Mulberry Street feeling lonely, she noticed an outdated chalkboard sign that

said, “Garden party.”

Even though she couldn’t tell beet greens from a tomato plant, she started showing up weekly. At one of her first potlucks, she said to Javier, “This seems like a great group of people.”

He replied with what she needed to hear most: “You belong here.”

Maria was thrilled to join this “collection of social misfits,” as Mike calls it. This eclectic and intergenerational group of people likely never would have met outside the garden.

These Thursday evening potlucks were my favorite time of the week. Sharing food and garden chores, I could escape my own neurosis as a newly self-employed pho-

tographer in a saturated market. My efforts at the garden had more predictable outcomes than my efforts in business. The seeds we planted in the spring reliably spouted and eventually gave us vegetables. And that felt real and grounding when my work life felt shaky.

Everything about the garden – being in nature, sunshine, physical work, microbes in the soil, the potlucks, bonfires and music – was good for my soul. It gave me so many things I needed: a group of friends to laugh with every week, people to cook for and talk about food with, a place to host visiting family and friends, and something to photograph just for me.

Javier always encouraged my photography, and he urged me to start an Instagram account for the garden. He wanted to share our community with everyone, and he made friends everywhere he went. People were drawn to him.

When Jilli found the garden, she and Javier became fast friends. It made no difference that he was about 20 years older. They brought people together over food and music every chance they got. Three springs in a row, they drove to the cargo area at Denver International Airport to pick up 60 pounds of live crawfish and poured them into a plastic kiddie pool until the boiling pot was ready. When Jilli turned 30, Javier brought the piñata to her kid-themed birthday party. Javier sometimes brought touring musicians to the garden, covering the fee himself because he told so many people they didn’t need to pay the cover – he just wanted them there. Old friends and former garden volunteers would always come back for these occasions.

Maria Gullo gives Louie a treat with Alicia Stice, Jilli Jackson and Julie Gillis. Chickens forage in the goat pen. Lorraine Dunn gets a kiss from goat Harriet. A volunteer picks apples.

Sunday, Aug. 14, noon-2 p.m.

Sample garlicky foods and learn how to grow your own. Tour the garden and bring your own 100 percent cotton T-shirt to tie dye. Donations welcome. To attend, RSVP to (970) 4800148 or subscriptions@coloradolifemag.com.

Anyone is welcome at regular volunteer hours through August: 5-7 p.m. Tuesdays and Thursdays; 11 a.m.-1 p.m. on Sundays. For more information on how to get involved, contact Lorraine at volunteer@mulberrycommunitygardens.org.

2310

(970) 493-1009

BY DECEMBER 2021, the pandemic had changed our acre of Fort Collins along with the rest of the world. Many of my garden friends had either moved away or into other seasons of life, keeping them from regular volunteer hours. I worked weekends out of town for a while, and I hadn’t been in months.

One Sunday, DeeDee arrived for volunteer hours looking like she was about to throw up. On her drive across town, she had gotten an awful call: Javier had died suddenly and unexpectedly. He had taken his own life. He had hidden his pain. Some who knew him best were shocked, but not surprised.

Telling Lorraine and Mike felt horrible, but it was a small comfort to share the grief with friends. Lorraine started letting people know, and Jilli came over to the garden right away. When Maria called me, my chest tightened, and hot tears flowed immediately. The world – and the garden – would never be the same.

A week before Christmas, Julie flew back from Massachusetts and Sam and Alicia made the drive from Denver to celebrate Javier’s life. We gathered at the garden, and everyone brought a dish inspired by him. We laughed and cried and shared food and memories with Javier’s brother and sister. After nearly 2 years of Covid, it was the best reunion that no one wanted to have to go to.

On a windy day this spring, we came together again to plant new life in honor of Javier – a hot wings maple tree – where he used to grill, between the mulberry tree and the pergola. Javier’s siblings mixed his ashes with the soil and the compost he always turned. We wrote notes on brown paper and fed them to the tree.

I think Javier would love the idea of his tree providing shade for the new cohort of volunteers sharing their talents like tie-dying, mushroom growing and the fluffiest southern biscuits I’ve ever had at elevation.

I came to the garden thinking I would do a quick feature story. I ended up with a long-term documentary photography project and many good friends. The garden will never be like it was in those few years before Covid. This community growing together will keep evolving. And we can always come back.

The Colorado wilderness has immense power, not least of which is its power to show humans their place in time and space. It is a truth our Colorado poets know well: Whenever we begin to believe our own delusions of grandeur, it is the wilderness that demonstrates what true grandeur is.

Suzanne Lee, Littleton

In deep darkness, the sky coal blue and sharp with the icy light of stars filtered through pines, campfire burned to black embers, lantern doused an hour ago, I move tentward. The silent sweep of nighthawk wing, feathers fanned, blesses my crown, tells me life continues here when I return to cities, people, noise, offers the touch of life to life without exaction.

Gregory Beaumont, Arvada

There are messages here, loud as kingfishers. The land has languages, stories to tell.

In wilderness there is no moral, save that it must continue. For all our probings and plottings we discover no adequate interpretation of the forces we find swirling about us –a larch you must touch to know: your neck must feel the ache of too much looking up. Watch its tree-point pirouette, then, looking back at the world level, you will discover you have lost all answers; for we have learned the art of building bridges, cataloging plants, predicting what a shrew might do. Of the essential mystery, we know nothing.

For Nature assigns no roles to its creatures; there is no reason for a forest fire, which burns mightily but with no intent; Life’s only purpose is the feeding of Life, and the beauty we see therein is but its lack of guarantee – for the chipmunk and the weasel and the man who measures his life to theirs, no assurance of long days, tempered seasons, abundant seeds, ample meat.

In wilderness lives mystery yet, unsimplified, not reduced, resplendent and immense.

Sandy Morgan, Colorado Springs

Our small woman hikes hills and valleys on a Sunday morning. The same trails where Utes and their Ancestors hunted and slept under stars that overpowered darkness –not by might nor by power but by Spirit.

Where rattlesnakes seek the sun; where wildflowers of June, full of pith and turgor, paint the way to summer. Bluebells, purple orchids, yellow sprites of several stripes animate the earth beneath our woman’s feet.

She has no words to speak –but she does hum soft and low like the sound of supple moccasins treading lightly, raising a cloud not of dust or words but of Spirit.

J. Craig Hill, Grand Junction

A waterfall plunging its way to the Gunnison; A bull elk in rut on a ridge to the west; A 20 knot wind blowing down the Black Canyon; A red-eye from Salt Lake headed off to the east.

Pamela Ritzman, Loveland

“The Upper Trail” on a wind-worn sign an upward trail for a thoughtful climb leagues off from sentry peaks who stand their guard

seated and silent now I look down the mouth of a whale shrouded in mist its river of snow cascading down received by earth and swallowed up below

she the divider of a continent the waters from her summit flowing eastward to Columbus’ shores and west through natives’ sacred lands to a foamy rest in surf two paths two lands two choices

snow spits its warning descend I must sided by split boulders poised to spill over like marbles to test the weary hiker who left home without a walking stick he has made his own choice –Westward

DO YOU WRITE poems about Colorado? The next poetry theme is “Colorado Memories” for November/December 2022, deadline Sept. 1. Send your poems, including your mailing address, to poetry@coloradolifemag.com or to Colorado Life, PO Box 430, Timnath, CO 80547.

by TOM HESS

photographs by JOSHUA HARDIN

THE SHORT, SHARP roar of a dragster, a sound as high-decibel and thrilling as a jet fighter launching from an aircraft carrier, turns the heads of motorists along C-470 near Morrison.

In the shadow of Front Range bluffs west of Denver, Bandimere Speedway is hosting a national contest, the professional drag racers covering a quarter mile from a dead stop to the finish line in under 4 seconds. Their top speed is more than 300 mph. A car on C-470 poking along at 65 mph takes 11 seconds longer to cover the same distance.

The roaring of engines and proximity to the Rockies has earned Bandimere Speedway the nickname “Thunder Mountain.”

Just over the bluffs to the west, a 2-mile drive away, is a source of more melodious noise: Red Rocks Park and Amphitheatre, the world-renowned outdoor concert venue where the biggest musical acts play. Bandimere Speedway is the Red Rocks of racing, a world-renowned drag racing track that attracts the world’s best drivers.

Weather permitting, each Wednesday from May to October, Bandimere hosts Test and Tune night, opening up its professional track to drivers from every walk of life: fathers and sons, boyfriends and girlfriends, grandmothers, a group of guys from the local auto repair shop. They’re driving cars of all kinds – late model and high mileage, upgraded and commuter, unleaded and electric.

Running on the famed Bandimere track in an everyday car is a little like playing neighborhood football on legendary Lambeau Field in Green Bay, every play broadcast on the big screen, the stadium scoreboard keeping track of the score and time, NFL officials throwing penalty flags and moving the chains.

Bandimere, like Lambeau, is hallowed ground for its sport. Unlike Lambeau, Bandimere offers all its trappings – race stewards, a so-called Christmas tree of red, green and yellow starter lights, time and speed displays – to nonprofessionals.

Amateur racers burn rubber on pro drag strip at Bandimere Speedway

TEST AND TUNE drivers line up two by two. They inch their way together down the slope to the Bandimere quarter-mile track. Those who know the value of heating their tires ahead of the race spin them in place, with the brakes on, for better traction, adding smoke and more noise to the cacophony.

The green light signals the start, and the drivers crush their gas pedals. Some cars bellow like a machine monster in response, others seem to crawl. An LED display at the end of the track shows the racers’ times and speeds.

As the night wears on, a rhythm emerges: tire burn, roar of acceleration, deceleration at the finish, repeat, like breathing or a heartbeat. The thunder of the bigger engines becomes less jarring and more familiar, and one soon notices when Bandimere falls out of that rhythm from a delay due to leaked oil on the track.

About 10 cars back from the starting line on one Test and Tune twilight, Kyle Cramsey is whispering into girlfriend Chantelle Driego’s ear – the tire burns too loud to allow a normal conversation.

Chantelle is preparing to race her aggressively upgraded 1975 Chevy Vega,

and she’s a bit nervous and softspoken. Kyle is reminding her of the basics, such as waiting to shift gears until the engine reaches a high and loud rpm. The tender conversation between the couple adds a bit of romance to the hard truths of gearboxes and physics.

Next to Chantelle’s white Chevy Vega is another white ’70s Vega, this one driven by 15-year-old Max of Castle Rock, with his dad, Ed, in the passenger seat. But on this day, the two Vegas won’t race each other. Track officials direct Max and Ed to the track alone, in the right lane. Max complies, but he and his dad both give a look at a spectator that they’re more than ready for Max to compete.

Max exudes confidence. When the light flashes green, his car accelerates. However, because he is not yet old enough for a full competitive run, he only goes an eighth of a mile with no one in the other lane. Though Max didn’t get to go nearly as fast as he wanted to, he still savors his first taste of racing.

Chantelle races next, the gravitational force of rapid acceleration pinning her back to the car seat. It’s the fastest she’s ever driven, and it’s all over in just over

12.852 seconds. Everything is a blur as she concentrates on shifting gears at the right moment, just as Kyle reminded her.

Afterward, she is excited to show a spectator the official printout she received stating that she finished the quarter mile at 104 mph, just above her goal of 100 mph. That achievement uncaged the tiger in Chantelle; she wants to do whatever it takes to run faster next time.

Youngsters make up most of the racers in line, but they’re not the only ones seeking thrills. Proving that you’re never too old for an adrenaline rush, Joy Ernster, age 73, brings her modified 1974 Dodge Charger to Bandimere for Test and Tune. When the Charger blew a gasket, she jumped into the bright red 1974 Chevy Corvette hard-top convertible she brought as a backup.

It’s the Corvette she’s testing tonight, “as many times as they’ll let me.” Joy’s first run is 90 mph, a disappointment, so she lifts the hood, leans in and adjusts her carburetor for temperature and humidity, just like she would back in her home shop. She’ll also try the opposite lane to see if it makes a difference. Sometimes it does, she says.

Two cars race toward the end of the track, where a slope helps them decelerate.

THE COLORADO STATE Patrol partners with Test and Tune events as part of its Responsible Speed program. “Responsible Speed” sounds like a lecture. Colorado State Patrol Sgt. Bonnie Collins prefers thinking about Test and Tune as a fun night at the track. She sometimes races her Dodge Charger patrol car at Bandimere as a form of outreach to civilian racers. She rarely wins – loaded with special equipment, her vehicle is too heavy to match the modified civilian vehicles – but winning’s not the point.

“Spectators cheer us on, whether we win or lose,” Collins said. “Hecklers will shout insults that we’re too slow.”

Whether the racers cheer or jeer her is beside the point, she said. The important thing is that they’re engaging with her.

The late John Bandimere Sr., a street racer himself in the ’50s, built the speedway. Bandimere wanted it to be a place where the best drag racers in the nation could compete, but also a place where drivers of all ages would bring their speedsters to his track and take the pressure off law enforcement agencies in stopping illegal and dangerous street racing.

Early on, John Sr. made a living with his special skill in rebuilding and racing abandoned cars and those he bought on the cheap. Word spread of his knowhow and racing ability.

That’s when car manufacturers began to take notice. General Motors invited him to Detroit in 1957. John Jr. recalls the trip, his dad racing his custom GMC Cadillac pickup against all challengers across the Midwest, an era of street racing celebrated in the 1973 film American Graffiti. “I do not remember anyone beating us on our trip,” John Jr. said.

Bandimere met with GM executive Ed Cole, the father of the V-8 Chevy and president of Chevrolet. Cole sold Bandimere for only $1 a rare and coveted 1957 Chevy Black Widow.

Back in Colorado, Bandimere talked about a “safety proving grounds,” perhaps on his brother Horace’s farm in Arvada. Locals protested that idea, so Bandimere looked farther west.

Bandimere picked land against the Front Range foothills, opening Bandimere Speedway in 1958. Bandimere leaves race teams elated or dejected – exchang-

ing leaping high-fives over a victory that might be just a few hundredths of a second ahead of second place, heads hanging when drivers release their finish-line parachutes too late and “beach” their vehicles; a sand pit at the end of the raceway catches cars that fail to slow down before the end of the track.

Professional drag racers go breathtakingly fast. In 2021, Brittany Force set a Bandimere track record by zooming 326 mph to complete the quarter mile in 3.717 seconds.

With that kind of speed, crashes in pro races at Bandimere are not uncommon.

Pro stock car racer Matt Hartford lost control from the very start of his race at Bandimere in 2013 and did all he could to avoid hitting the competitor in the right lane. He succeeded, but his car smashed the left wall. Hartford climbed out unscathed, but the crash destroyed his vehicle and bruised his ego. “I really hate to tear up equipment,” Hartford told ESPN.

Through the decades at Bandimere, Test and Tune nights have carried on largely without mayhem, seldom making it into the sports pages but never leaving the memory of its participants.

Drivers awaiting their turn on the track check out the competition.

A driver makes a last-minute check of his tire pressure before a race.

AS HONORABLE AS Test and Tune’s mission may be, the speedway has never been without its critics. Neighbors in new developments on the other side of C-470 complained about the noise. Some homeowners filed suit in court, asking a judge to silence the speedway. The judge said no.

John Sr.’s grandson John “Sporty” Bandimere III spends a lot of his time, sometimes more than at the speedway itself, in building rapport within the community. If neighbors understand the benefit of the noise – safer city streets – maybe some will learn to live with it, or at least see that it helps with a growing problem. Illegal street racing made headlines last November, when a 21-year-old woman and her dog died when two street racers struck her ve-

hicle on Sheridan Avenue in Westminster.

“Street racing in communities around us, around the Front Range, is a large problem again,” Sporty said. “For 64 years we worked on this, providing an outlet” for speed. The only other drag strips in Colorado available to street racers are in Grand Junction, Julesburg and Pueblo.

It seems proof of the success of Test and Tune Night’s mission to see so many self-described street outlaws choose a night of racing at Bandimere over the potentially deadly alternative. And unlike American Graffiti, no one is pulling apart the back end of a patrol car as a prank. They’re racing and sometimes beating a State Patrol car head-to-head to Bandimere’s finish line. That brings a smile to everyone’s face.

AUG. 6 • CRAIG

While hot air balloon pilots can make their craft go up and down, they are at the mercy of the wind when it comes to lateral movement. This makes it critical to launch at a time and place with favorable wind conditions – and it just so happens that summer sunrises in Craig are nearly perfect.

Craig’s calm morning air typically allows pilots to keep their balloons concentrated right over town, making for a stunning sight when nearly 30 brightly colored balloons launch from Loudy-Simpson Park at the Moffat County Hot Air Balloon Festival.

After the 6:30 a.m. balloon launch, the park is filled with activities until 10:30 p.m. Colorado Cruisers brings 100 classic cars. The Cardboard Regatta has people in homemade cardboard boats trying to race across the pond without sinking – and

some actually make it. There are arts and crafts for sale, as well as 20 food vendors, each specializing in a different cuisine.

Live music starts at noon, with the Petty Nicks Experience headlining at 7:30 p.m. As the sun sets, the balloons behind the stage turn on their burners for a stunning balloon glow. “It’s a big, huge heavy flame when they do their burners,” event organizer Randy Looper said. “It’s like bursts from a flamethrower.”

Balloons also launch the day before and after the festival. People are welcome to go right up to the balloons and interact with their pilots. Though paid passenger flights aren’t available, Looper said, attendees often offer to help pilots launch and recover balloons the day of the festival in exchange for a free balloon ride the next day. (970) 629-0654.

Nearly 30 brightly colored hot air balloons fill the morning sky above Craig’s Loudy-Simpson Park.

Pizza is the biggest draw at this popular Italian eatery, but the menu is hardly limited to that. Other favorites include calzones, strombolis and a variety of pasta dishes. House specialties include Steak Carelli, which is topped with bearnaise sauce and crab meat, and Walnut Sage Money Bags, featuring Italian cheese pasta purses. 465 Yampa Ave. (970) 824-6868.

SAND WASH BASIN HERD MANAGEMENT AREA

Sand Wash Basin is home to one of the United States’ few remaining herds of free-roaming wild mustangs. There were nearly 900 horses in and around the herd management area at last count. Part of Bureau of Land Management land, the area is open and free to enter – visitors are just asked to keep a minimum 100 feet from the horses. County Road 67, Maybell (970) 673-7768.

JULY 1-SEPT. 5 • DENVER

Maybe it’s for the best that humans never coexisted with dinosaurs: Even if we managed to evade the ravenous maws of the horrifying carnivores, there’s a good chance we’d still get squished by those supersized plant easters. Even so, it’s a shame that we can never see these colossal prehistoric beasts in real life. Or can we?

Jurassic World: The Exhibition is just the thing to satisfy those hungry for an up close and personal dinosaur encounter. This immersive, 20,000-square-foot experience at the National Western Center’s HW Hutchison Family Stockyards Event Center is filled with startingly realistic animatronic dinosaurs from the Jurassic World movie franchise.

The various types of roaring, lunging robo-sauruses each inhabit their own special sections. In Land of the Giants, visitors meet gigantic sauropods like Brachiosaurus. The Hammond Creation Lab shows the sci-fi techniques used to clone dinosaurs in the movies. At T. Rex Kingdom, attendees prove their bravery by standing face to face with the mighty Tyrannosaurus. And then there is the Raptor Experience, where visitors meet the small but lethal hook-clawed predators. On the cuter side of things, people can snap selfies with some ferociously cute baby dinosaurs.

Tickets should be purchased in advance at jurassicworldexhibition.com.

Admission starts at $29.50 for those 16 and older, and $19.50 for children 3 to 15; children 2 or younger may enter for free. (720) 707-0670.

Specializing in made-to-order burgers, shakes and fries, Park Burger complements its menu with 40 beers on tap and a large selection of whiskeys that bartenders use to create custom cocktails. The expansive patio becomes an urban garden during summer. On weekends, Colorado bands provide music. 2615 Walnut St. (720) 381-0126.