How musicians use visual stimuli to amplify and engage an audience beyond sound:

In reference to Social Media and Transmedia Storytelling

Berenice Lunn20129018

Critical Practice (VIS6037)

Dissertation Tutor: Ruth Yeates

Word Count: 5977

Abstract

This dissertation will analyse why visual stimuli is significant in the representation of musicians and in the accompaniment of sound. Additionally, this study explores how musicians seek to amplify and engage audiences beyond sound, utilising developing media and the construction of complex, narrative worlds to portray music more elaborately. Finally, this study discovers how transmedia communications and social media assist in the distribution of richer and more immersive forms of entertainment surrounding sound that are delivered to audiences widespread today.

Abstract

Contents page

Introduction

Chapter One:

Is visual stimuli important within the music industry?

Chapter Two:

How are musicians amplifying the way their sound is experienced today?

Chapter Three:

How are musicians using transmedia storytelling and Social media to curate more immersive entertainment surrounding music?

Conclusion

Music as a form of entertainment is expanding beyond its traditional means in line with developing media, and new opportunities our digital world provides. Within chapter one, this study seeks to identify if visual stimuli is considered important within the music realm by analysing its primal functions and exploring whether its presence is truly relevant to the consumption of music or not. Additionally, this research will look at the responsibility of visual stimuli in the discovery of music, particularly focusing on whether this has grown more or less important with today's audience and how music is most commonly consumed at present. Furthermore, chapter two analyses how musicians today strive to engage and retain audience’s attention in ways beyond sound to satisfy the modern audience and their expectations; with a central focus exploring how artists are translating their sound through visual narratives to amplify the way their music is experienced on an additional plane. This chapter will also identify the influences that are responsible in driving this progressive shift towards more conceptual, and elaborate representations of sound. Finally, chapter three investigates the meaning of transmedia storytelling and how it is utilised by musicians to project multi-dimensional and fully realised embodiments of sound. Delving into why social media is the port of call for musicians to deliver their sonic roll out, how it assists in reaching wider audiences and identify whether it contributes towards curating more immersive entertainment experiences surrounding music. Ultimately, the concluding insight addresses the ability for musicians to extend their sound into additional outlets to engage audiences further. This study is important as it is essential to recognise change to be able to acknowledge and appreciate what we are fortunate enough to experience today. In response to advancing technology, the music industry is simply responding to this evolution and moving with what audiences are asking for. This insight is a celebration of the artistry of music, hoping to bring awareness to the often-overlooked extension of sound that has the capability to transport audiences away from reality for a moment in time

Chapter One: Is visual stimuli important within the music industry?

In addition to sound, the visual representation of musicians has always been an important consideration in translating the identity, message, or narrative an artist intends to deliver to their audience. Sound is the predominant output for a musician; aesthetic and other design considerations are not the primary objective of releasing music. Despite this, understanding how and why they should be utilised and carefully considered by an artist is of paramount importance to communicate sonically with an added impact.

In an interview for Spotify with Marissa Ramirez, Director of Creative Content, and Music Video Commissioner at Interscope Records, visual image is described as an artist’s ‘physical embodiment’ (Crowley, 2019). A collective of visual representatives such as an overarching aesthetic, typography, and stylised imagery (see Figures 1 & 2) are often used to construct an artist’s identity, conveying the intended tone and genre of the sound when used in conjunction. Evidently, design provides musicians with an additional medium to sell their artistry, allowing an audience to indulge in their sound with deeper meaning and understanding of who an artist is, and what they want to communicate. Furthermore, this illustrated embodiment assists in capturing the individuality of an artist, proving to be a vital asset in creating an immediate and obvious juxtaposition from competitors.

Alongside an artist’s desire to outshine competitors, the purpose of creating visual supplements in conjunction to sound is to enhance the listening experience for consumers (Borg, 2021). The terminology used to define the ‘listening experience’ includes ‘all possible factors that may influence listeners’ rating of stimuli’ (Walton & Evans, 2018); addressing why additional stimuli, such as visual elements, are influential to achieve maximum satisfaction from an audience when indulging in sound. The satisfaction subsequent to the presence of visual stimuli is fulfilled due to the delivery of a richer experience, as audiences are engaged beyond a singular sense. When experiencing sound alone, our mind leads to

Figure 1 @theweeknd. Photograph of The Weeknd in promotion of his latest album, ‘DAWN FM’ (2021)

Figure 1 @theweeknd. Photograph of The Weeknd in promotion of his latest album, ‘DAWN FM’ (2021)

create mental projections of imagery (Pearson & Wilbiks, 2021), in doing so, it could be interpreted as our brain attempting to solve or create a solution to satisfy the instinctive human desire to consume information visually (Mazurek, 2017). This proves that the addition of visual stimuli supplied with sound, helps to provide a ‘framework of understanding and context in which the music lives’ (see Appendix 4.); instructing clarity as to what is intended to be delivered by an artist (whether in terms of genre, mood, narrative etc.) and therefore, enhances the listening experience. From an alternative point of view, however, an opposing judgement states visuals ‘decrease the appeal of a song by imposing a given interpretation that, thereby, limits a listener’s imagination and cognitive involvement' (Boltz, 2013, p.243; Zorn, 1984). As highlighted by Boltz, this remark proposes that the aid of visual cues in fact draws away from the listening experience, by stripping listeners of the freedom to interpret a song as they wish due to preconstructed narratives. Understanding there is beauty in what's not always obvious, and or directly fed to an audience is brought to light by Boltz; suggesting how the addition of visuals used to envisage sound might somewhat stunt a factor of enjoyment in the way music should be experienced.

In reference to what has been discussed prior surrounding visual stimuli as a tool to further engage an audience, it is important to note how music is typically consumed, and what its intended service is; to deliver sound. In search to understand how design in the music industry is perceived by audiences, results collected in a recent survey revealed that 52.5% of people do not consider visuals to be important when listening to music. In addition, agreeing that sound is the only important factor when consuming music (see Appendix 4.). These findings question the relevancy of design in the delivery of music by addressing the reality that over half of people who consume music, do so exclusively in its auditory form. As a form of entertainment, music is often not the central focus or holds the entirety of our attention, more commonly indulged in the background or as a supplement enjoyed alongside other things we do, as an example, whilst exercising. With acknowledgement of this, it can be understood why visual stimuli is not essential for most consumers of music.

In summary of exploring differing views, it is evident that the accompaniment of visual stimuli in music can be used to elevate the listening experience and therefore draw greater engagement from an audience. With heightened engagement, musicians can expect loyalty of reoccurring fanbases, eager to see what an artist does next, transitioning from passive engagement into active. In all, this is hugely beneficial to an artist’s success.

When utilised consistently, visual assets which form an artist's outward image all play a significant role in creating associations that aid their recognition. Visual stimuli is not only an impactful tool in curating a better experience for listeners but as stated by Amber Horsburgh, Music marketing consultant, it is also effective in ‘[facilitating] memory recall, as visual memory is stronger than audible’, (Horsburgh, 2019). This idea is accredited with research surrounding the human psychology in multimedia music distribution, whereby it is understood that a unified system of audio-visual information achieves a more memorable influence on listeners (Tan et al., 2013). In exploration of this, Figures 3,4 & 7 individually depict a different approach in curating a strong, visual identifier to encapsulate the identity of a musician, resulting in the immediate association and recognition of an artist.

Figure 3 showcases arguably the most widely recognised, and iconic visual symbol in music history, which is The Rolling Stones' tongue and lips. Despite there being no obvious or direct indication to the band within this symbol, it serves as an exemplary representation of how a graphic icon can prompt instantaneous recognition of a band. Having successfully stood the test of time as a result of its simplicity and consistent application.

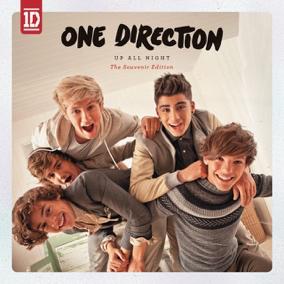

Figure 4 provides an alternative example of how an element of design, in this case typography, has been utilised persistently by the band One Direction. The specific brush typeface is recognised as a branch of the band’s identity, appearing across any touch point where possible. During the band’s career the typeface remained present on every album cover (Figure 5), concert ticket and merchandise item (Figure 6) from the day their branding was formed. The longevity and consistency of the typeface’s application meant that it could be utilised to deliver additional forms of copywriting (other than to promote the band name as shown in Figure 4.) and still be instantly associated to. Highlighting an additional way visual language is used to identify a musician/band

Figure 3 The Rolling Stones Logo (1971)

Figure 4 One Direction Logotype (2010)

Figure 3 The Rolling Stones Logo (1971)

Figure 4 One Direction Logotype (2010)

Figures 7 and 8 portray another and concluding example of how musicians use visual identifiers to instigate a recognisable point of difference from their competitors. As evident here, musicians can adopt colour and use this particular graphic device to stem their visual identity. As evidence of this, Billie Eilish constructed her identity as a musician surrounding her signature black hair with neon green roots. Eilish applied this distinctive physical aspect of her identity and translated it into her branding, making use of this colour scheme in the way she dressed, across merchandise and other additional touch points. This defined use of green and black proves how colour can act as a dominating feature in visually representing an artist. The use of colour in this case too, allowed for the debut of her platinum blonde hair to signify a turning point in her musical career. This new, reborn identity utilised colour as a primary tool to symbolise change and promote Eilish’s new era of sound (Allaire, 2021) (see Figure 8). In analysis of the examples provided, why has the addition of visual indicators proved favourable to artists? They serve to represent and cause for immediate recognition; when distributed consistently, visual cues strengthen an artist’s visibility as audiences are recurrently exposed to their image. Alongside this, as confirmed earlier, the addition of visual information in support of audio overall increases the likelihood of being remembered, as more than one sensory element has retained information. The instantaneous recognition of an artist through visual identifiers indicates if an identity has done its job successfully. In summary, proving visual assets in the construction of a unique identity is favoured by artists and is a tertiary reason why visual stimuli holds value in the accompaniment of music.

Figure 6 One Direction concert ticket (2014)

Figure 7 Billie Eilish at the Spotify Best New Artist Party (2020)

Figure 6 One Direction concert ticket (2014)

Figure 7 Billie Eilish at the Spotify Best New Artist Party (2020)

In understanding why visual stimuli is important in the music industry today, it is of major importance to consider the way music is most frequently consumed and how music is discovered in this day and age. Music today is most commonly accessed online, through social media and streaming platforms (see Appendix 4.). As a result of this, there has been a noticeable incline in recent years of music promotion through social media (see Figure 9), as artists recognise their audiences are present and easily reached here. This being identified in conversation with Birmingham based indie rock band, The Chasers, who further commented to say that for independent artists in particular, social media is the primary space for music promotion (see Appendix 5.) With the dominating presence of screens ever-

design was the only thing presented make a judgement buying based on the visual appeal; this discussion focuses on visual stimuli’s responsibility online. Similarly, however, the basic principles have not drifted, as increasingly today, ‘talent is seen (via. Instagram feeds, thumbnails of streaming homepage artists etc.) before they are heard’ (Crowley, 2019). Inquiring further into this idea, 77.5% of respondents when questioned said that when searching for new music, the visual image of an artist does influence their decision as to whether they take a chance in listening to an artist (see Appendix 5.). This evidence informs that a visual pre-judgement withstands; addressing why the importance of visual representation of sound is still as important online, despite given the opportunity to make our judgement by listening if we wish, as access to do so is available unlike previously.

In light of our ability to access both auditory and visual content online, Forbes unveiled an insight which prevails the value of attention-grabbing visuals in addition to music. In a recent article, Forbes documented a study conducted by Verizon Media which identified that 69% of people watch videos online with the sound off (McCue, 2019). This evidence proves that a large proportion of people are likely to not consume, and definitively overlook the intended product in which musicians promote, sound. With this, the responsibility of visual stimulation is heightened and must function to ‘make up the difference’ (Horsburgh, 2017) in order to maintain audience engagement. Enough to intrigue and encourage viewers to take another action from the content, such as pressing the ‘Listen now’ feature to jump directly to the promoted content, as shown in Figure 9 In all, linking directly to what was mentioned previously, that musicians are often seen before heard with how music is experienced today, affirming the importance of visual stimuli in the consumption of music.

Chapter Two:

How are musicians amplifying the way their sound is experienced today?

Today, musicians have evolved the style of content they deliver to their audiences, prioritising visual deliverables equally with sound in curating more expansive, and elaborate sonic projects. A trending approach in which this is executed by musicians today is through the development of innovative, alternate universes in which the sound lives, as shown in the examples below (see Figures 10, 11 and 12) Figure 10 displays a still from artist Detroit Dyer-Millers’ visualisation of ‘Uncanney Valley’, the title of COIN’s latest album. Within this trailer, Detroit walks audiences through a utopian 3D universe, hinting visual cues which relate to individual tracks throughout, such as the black figure in the distance (Figure 11). This body of work demonstrates the extent in which artists go today in portrayal of their

Additionally, Abel Tesfaye, a musician more commonly known as The Weeknd, is also notable for his development of compelling, multi-dimensional worlds, curated to embody and define his progressive musical eras The language used within the trailer of The Weeknd’s latest release titled ‘Dawn FM’, ‘a new sonic universe from the mind of The Weeknd’ (Dawn FM Trailer, 2022) evokes an insight as to what an audience can expect from this album, this being more than solely an auditory experience. The descriptor ‘sonic universe’ holds weight in depicting a feast of the senses, preparing audiences to embark on a journey through an alternate environment; providing a plane of escapism and opportunity to disconnect from real world normalities This is evident in Abel’s collaboration with Amazon Prime in creating The

Figure 10 Still from Uncanney Valley 3D Trailer (2022)

Figure 10 Still from Uncanney Valley 3D Trailer (2022)

Weeknd X Dawn FM Experience (2022), a 34-minute film whereby he ‘performs his latest album live in a theatrically unsettled and unnerving world’ (Amazon Prime Video, 2022). This evidently demonstrates an evolved style of content, expanding beyond the average 3–5 minute music video, showcasing a unique and elaborate way for musicians to amplify their sound.

In comparison to the response from COIN, The Weeknd takes this innovative portrayal of

as a contributing factor in maintaining a listener’s interest, evident in the continuously high view counts displayed in Figure 12.

In summary, these examples demonstrate how musicians have expanded their content beyond their traditional output and expected role as musicians, that is, primarily, releasing an album and performing it live on tour. Evidently, these case studies prove to create more immersive experiences which amplify the way sound is consumed. Confirming visual storytelling (defined or undefined) to be a successful approach in the delivery of music to retain audiences’ interests and engagement with an artist.

In consideration of the examples above, what has influenced this progression towards new and more exciting ways for musicians to engage audiences beyond sound? Primarily, as addressed by Jackson, ‘[technology] has especially changed the way we interact and listen to music’ (Jackson, 2019) and therefore, the type of content we expect to see has also shifted. Prior to the prevalence of digital media in our lives, musicians were limited to more traditional forms of communication to embody their work such as CD’s, vinyl, and live performances. The opportunities our digital world provides are endless in comparison, as with technology, we have very few constraints to what can be executed in terms of visual possibilities. This is reflected in the emergence of new, more advanced ways to experience sound accessible to us today, for example ABBA Voyage. The first of its kind, ABBA Voyage is an unprecedented virtual concert featuring members of the band as holographic avatars in their prime.

This multi-sensory fusion between physical and digital reality indicates a new direction in which the future of the music industry is heading. As predicted too by Jonny Carr, Motion Designer, who anticipates this type of interaction with music to become the new normal in context to the work from home culture forced upon us in today’s climate (see Appendix 2.). Consequently, the awareness from audiences of the possibilities in which technology allows artists to portray their sound has led to the expectation for them to do more with the content

they create today. As identified within a survey 89.74% of respondents agree that music is no longer solely judged by sound, and that listener’s do expect artists to produce something different to what we have already seen and experienced because of what is possible today (see Appendix 4.).

In summary, this identifies the advancements of technology to be an influential factor in why musicians are discovering new ways to amplify and engage their audiences beyond their music. There is a growing demand for more in every field of communication today and musicians in hand, are simply responding and evolving their content in line with the time and developing media.

Moreover, another influence which has sparked the necessity for artists to push more innovative and elaborate content today, is the space in which music is accessed most frequently, online (see Appendix 4.). Social media and streaming platforms are heavily saturated markets with an estimation of 95 million posts being shared on Instagram daily (Wise, 2022) and ‘roughly 100,000 tracks uploaded to [streaming services such as] SoundCloud, Spotify and Apple’ everyday (Willman, 2022). Due to the overwhelming volume of content that is distributed to consumers today, a study conducted by the Technical University of Denmark ‘suggests that the collective global attention span is narrowing’ (McClinton, 2019) as a result. Evidently, the pressure to be noticed and stand out amongst this wealth of content explains why artists such as The Weeknd are taking their craft to the next level and delivering it in a way that is bold, outlandish and irresistible. In conversation with Andrew Evan, Graphic Designer and Creative Director in the music industry, he reinstates this battle to be seen, referring to social media as the ‘attention-economy’ (see Appendix 3.), agreeing that for artists to capture this limited attention from audiences online, the content they deliver must be innovative enough to prevent people from scrolling past (Vlasak, 2021) In greater analysis of this point, the shortened attention span of audiences today addresses why musicians nowadays often make a statement in reinventing their aesthetic to mark a new era of their sound. An example of this can be seen within the discussion already in the transition from ‘After Hours’ into the ‘Dawn FM’ era created by The Weeknd. Figure 12 depicts the red, heated, and gory nature of the ‘After Hours’ storyline which as it comes to a close, hints the direction towards a new era as the temperature drops; reflected in part seven of the music video series, ‘Too Late’. Leading on, evident in Figures 1 and 2, the overarching aesthetic transitions into a dark, super-natural blue, a direct indication of dawn rearing near and the beginning of the following album ‘Dawn FM’. What this example shows is how musicians are responding to oppose this minimised attention span by refreshing how they are perceived by audiences. As said by McErlean, in commentary of immersive storytelling across new media platforms, ‘[predictability] no longer holds [our] attention’ (McErlean, 2018, p.59). Raising the point that artists are likely to be overlooked and not withhold attention if what they deliver is already familiar to us. By redefining their visual image, musicians can regain audience attention after a period of time and proves to be a successful way in maintaining relevancy by providing viewers with new, evolved content to indulge in. Reinstating how and why musicians are being more daring and innovative with their distribution of sound to establish an impactful point of difference that makes them stand out amongst today’s saturated stream of content.

Following this evidence, it can be interpreted why musicians in today’s society are redefining the traditional roll out of promotional content expected from musicians. Proving that attracting and engaging audiences with innovation beyond sound is fundamental in today’s environment. Ultimately addressing the main cause of this discussion, that visual stimuli and strong creative direction in support of sound is of overwhelming significance in the way music is perceived, experienced, and consumed today.

Chapter Three:

How are musicians using transmedia storytelling and social media to curate more immersive entertainment surrounding music?

So far in this discussion, we have identified why visual stimuli is important within the music industry and how it is utilised to construct a more immersive, and richer experience of sound. In continuation, this chapter analyses how musicians distribute their content to deliver with an impact in today’s environment, exploring both digital and physical approaches in doing so.

Aligning with the elaborate embodiment of music today, the way in which this is distributed too, has equally grown to new heights. According to Sean Cole, ‘gone are the days of just focusing on traditional promo – billboards, press runs and interviewing – we’re in a time where [artists] are turning to Instagram and Spotify to announce their latest albums’ (Cole, 2019) Here, Cole reinstates the recurring idea brought to light in this discussion, that musicians today are no longer simply ‘just’ doing what is required by their role. He addresses that artists nowadays are exceeding beyond the traditional forms of music distribution, making use of any, and all modes of communication that might help amplify the way their sound is experienced. This approach adopted by musicians can be referred to as transmedia storytelling, defined by Jenkins (2011) as, “a process where integral elements of a fiction get dispersed systematically across multiple delivery channels for the purpose of creating a unified and coordinated entertainment experience” (Click, M.A. & Scott, S., 2017, p.337) and as recognised by Cole, social media has become the predominant space for musicians in assisting this development of a superior entertainment experience. Why is this? Fundamentally, social media has matured to be arguably, one of the most ubiquitous forms of advertising today, identified by Peter Stringer claiming, “I currently see an ad after every three organic posts on my own Instagram feed” (Gesenhues, 2019) and in conjunction, the Digital 2022: Global Overview Report estimates that people spend an average of 2 hours and 27 minutes on social media daily (DataReportal, 2022). The evidence proposed identifies that social media today has shifted from singularly, a means to connect with others such as our friends and family. It is recognised as an integral mode of communication in our day-to-day lives, a platform where people are recurrently active, and because of this, it is utilised by musicians as the optimal space to reach audiences, promote, and further elaborate the way in which their sound is consumed.

With this progressive shift in social media functioning as the port of call for artists to increase drive towards their music, consequently, musicians take on a greater responsibility to act as ‘content creators’ (Majewski, 2019), as social media provides an enormous canvas for artists to visualise their sound and entertain through a variety of formats following the transmedia approach. Many artists today have changed the way they deliver the roll out of a sonic project as of the internet and social media; communicating across multiple platforms and tailoring the content distributed to suit each networks specific form of media (Antoniak et al., 2020) This is evident in the content used to promote The Weeknds’ ‘After Hours’ album,

whereby the same components of the sequential narrative are visualised in different formats; as displayed in Figures 14 and 15. Figure 14 portrays a still image from the ‘Heartless’ music video, the introductory short film to the ‘After Hours’ saga. The photograph of the frog depicts an integral element of the storyline whereby The Weeknd licks its skin, causing him to spiral on a hallucinogenic journey that viewers embark on throughout the following music videos. In this video, the narrative is performed as a live-action embodiment of sound as The Weeknd himself, plays out this role. Additionally, this scene was reimagined as an animation distributed via. TikTok, in a short-form, 15 second video, to generate hype surrounding an alternate way to experience The Weeknds’ biggest hits in The Weeknd Live TikTok Experience (2020) Predominantly, these examples show how visual stimuli can be used as a significant contributor towards extending an audience’s attention by engaging beyond a singular touchpoint. These alternative visual embodiments additionally, draw the possibility of attracting wider audiences who might choose to explore the body of work for its innovative artistry, and not depending on whether the music initially appeals to them or not. In summary, this highlights the widespread landscape social media provides as not only a space for unlimited modes of distribution, but also access to different, emerging entertainment experiences surrounding sound, as follows.

The Weeknd Live TikTok Experience was ‘an interactive XR broadcast’ (TikTok Newsroom, 2020), on TikTok where the terminology ‘XR’, refers to ‘Extended or Cross Reality’ (Roizin & Wang, 2021, p.751); describing any immersive interaction that merges real world and virtual environments. This live stream encompassed a virtual, 3D world surrounding an avatar of The Weeknd performing his songs in the animated style pictured in Figure 15. This one-of-akind, interactive experience with sound, blended the fictional narrative of the ‘After Hours’ album into reality, allowing audiences to participate, and direct the visual environment in real time; for example, in correspondence to Figures 14 and 15, viewers could vote within the live chat as to whether The Weeknds’ avatar should lick the frog or not (see Figure 16). This example portrays one of the most advantageous factors of using social media and innovative design technology to tell stories today, audience involvement; as supported by Miller stating, ‘one of [digital storytelling’s] unique hallmarks is interactivity – back and forth communication between the audience and the narrative material’ (Miller, 2019, p.5). In support of this furthermore, the presence of a live chat alongside the stream allowed for viewers to interact,

Figure 14 Still from the ‘Heartless’ music video on YouTube (2020)

Figure 14 Still from the ‘Heartless’ music video on YouTube (2020)

share their thoughts, and communicate with one another through out. This element of interactivity online evidently bolsters the formation of communities or alternatively known as fandoms; supplementing a sense of belonging by bringing people together who share a common interest in a particular artist (Duffet, 2014; Hodkinson, 2014). To summarise, the social component of experiencing music online is equally a major factor which contributes towards a more immersive form of entertainment. This is because audiences can be directly involved and partake within the content distributed, whether that is simply commenting under an Instagram post or curating their own original content in response. This shines as the point of difference from more traditional, passive media and is why musicians today are turning to online and social platforms as their predominant means to distribute music today.

Despite the prominent use of social media to house content that will amplify an audiences’ experience with a sonic project, it is not to say that these same narratives or story worlds are not translated into physical environments too. Nick Vorhees writes that ‘successful musicians are always looking for new and powerful ways to attract a wider audience’ (Vorhees, 2020), and in continuation of the analysis surrounding the ‘After Hours’ universe, this is apparent in the creation of ‘The Weeknd: After Hours Nightmare’ A Halloween themed experience hosted by Universal Studios Orlando Resort, this two-night event placed visitors directly within a spatial environment depicting the fictional world in which the album exists. This example shows how artists today can curate new and exciting ways to draw audiences

towards their music in physical environments beyond a traditional concert. As said by The Weeknd himself, he feels his “music videos have served as a launching pad” (Tesfaye, 2022) to allow him to extend his craft into additional outlets that in all, contribute to the overall amplification of his music.

Additionally, this immersive extension of the album translated through a performative, physical experience could be said to ‘dissolve the boundaries that separate performers from audience and artwork from viewers’ (Karen et al., 2014, p.15); and in combination with social media, these delivery channels utilised by The Weeknd as part of a transmedia narrative, depict an example of how a story world can bleed into our own reality. This is predominantly apparent on social media as within these spaces, we share our real, personal lives and today, they are also being used to share fictional ones This idea of blurring the lines between imaginary universes and reality as addressed throughout this chapter, is too personified by The Weeknd’s public appearances during the time of the ‘After Hours’ release As part of the promotional roll out to spark conversation, Abel attended award shows, press opportunities, and even performed at the 2021 Superbowl Half Time Show as this alternate persona which lives within the sonic universe. In summary, these examples show how The Weeknd is engaging his audience beyond sound through varied multisensory engagements, exceeding his primary role of creating music. It is evident throughout this study as to the extent musicians can go in broadening their artistry, as proved by The Weeknd who resembles one of the “most forward-thinking artists” (Arrigo, 2020) of our generation and sets the tone for where the future of the music industry is heading by showing what is possible within this entertainment space.

Finally, in accumulation of all that has been discussed within this chapter, it is evident how musicians are able to amplify their music through transmedia communications. As shown, this repetition of a singular narrative translated through a wide range of deliverables constitutes to the formulation of a ‘unified and coordinated entertainment experience’ as previously defined by Jenkins (2011) and is likely to induce a more positive response from audiences according to the psychological finding referred to as the Mere Exposure effect. This understanding proposes that audiences ‘evaluate a stimulus more positively after repeated exposure’ (Van Dessel, et al., 2017) and can suggest why a wider, more varied distribution of music has a greater memorable impact. Moreover, and in final evaluation, this diverse array of visual stimuli and plethora of ways to communicate and engage audiences, evidently elevates the listening experience by curating a more immersive entertainment experience by allowing audiences to encounter a multi-dimensional perception of the sound.

Conclusion

In evaluation of this research, evidently today musicians are actively responding more innovatively to the way in which they visualise and distribute their sonic entity. This research unveiled a sound understanding as to why fundamentally, visual stimuli is equally an essential component to how music is experienced today by providing a richer entertainment experience in comparison to audio alone. This dissertation informs why musicians in an age of advancing technology and social media are defying the expectations of their traditional responsibility, exceeding to curate alternate visual dimensions which promote audience immersion and the opportunity to leave reality, led by sound. With the influences of technology today, these findings too, suggest that the future of music consumption is constantly progressive and never at halt with the ever-emerging, new possibilities our digital world supplies. This further supports why this discussion is relevant in documenting where we are now as addressed within the introductory of this dissertation; because of the rate at which multimedia entertainment is evolving, it is easy for audiences to neglect or overlook what is offered to us by musicians today as uncovered true, through primary research which informed that most audiences only seek interest in the auditory experience. This additionally aids in providing further reasoning as to the intention behind this study, in hope to direct greater attention towards the innovative deliverables musicians are putting forth today in addition to sound.

In evaluation of the research techniques used, by talking with musicians, graphic designers within the music sector and audiences themselves, this allowed for a broad range of insights from a collective of valuable perspectives which helped navigate this discussion. The conversations and analysis of the proposed results provide that this study is outstandingly subjective, and open to debate if the engagement of audiences further than the sound itself is truly necessary. Despite this, whether it is considered necessary or not is beside the point, what is necessary is the means and opportunity for artists to exhibit their artistry in an abundance of ways that is identified possible within this discussion. Music is an art of lyricism and storytelling and the translation of this visually, undeniably amplifies our engagement surrounding it. In consideration of all that was discussed, the outweighing and favourable insight uncovered through this study which proves how musicians are amplifying and engaging their audiences beyond sound, is the element of interactivity presented through communicating music via. social media. This observation surrounding community building and bringing audiences together in all, consolidates the purpose and appeal of music beyond any other stimulating factor. Feeling involved as part of something is the most immersive and engaging factor of all.

List Of Images

Figure 1. Ziff, B. (2021) @theweeknd. Photograph of The Weeknd in promotion of his latest album, ‘DAWN FM’ [Photograph] At: https://www.instagram.com/p/CSsMuOUlAGj/ [Accessed on: 21 October 2022].

Figure 2. Pinkerton, B. (2022) Titles for @theweeknd dawn FM album trailer [Image]

Available from: https://www.instagram.com/p/CYkCNtgBreG/ [Accessed on: 21 October 2022].

Figure 3. Pasche, J. (1971) The Rolling Stones Logo [Illustration]

Available from: https://www.johnpasche.com/Rolling-Stones-logo-1971.html [Accessed on: 24 October 2022].

Figure 4. (2010) One Direction Logotype [Image]

Available from: https://1000logos.net/one-direction-logo/ [Accessed on: 24 October 2022].

Figure 5. Spotify (2012–2015) The first and most recent One Direction album covers [Album Cover] Available from: https://open.spotify.com/artist/4AK6F7OLvEQ5QYCBNiQWHq [Accessed on: 24 October 2022].

Figure 6. Lunn, S (2014) One Direction Concert Ticket and One Direction Official Tour Merchandise [Photograph] In possession of: Sonia Lunn: Wolverley

Figure 7 Collin, X. (2020) Billie Eilish Photographed at the Spotify Best New Artist Party [Photograph] At: https://hollywoodlife.com/2021/01/28/billie-eilish-green-outfit-photomatching-hair-shoes-sunglasses/ [Accessed on: 24 October 2022].

Figure 8. Eilish, B. (2021) Billie Eilish Happier Than Ever album cover [Album Cover]

Available from: https://open.spotify.com/album/0JGOiO34nwfUdDrD612dOp [Accessed on: 24 October 2022].

Figure 9. The Academic., Arctic Monkeys., Mcrae, T. (2022) Music Ads on Instagram Stories [Sponsored Story] [Accessed on: 25 October 2022].

Figure 10 Dyer-Miller, D. (2022) Still from Uncanney Valley 3D Trailer [Album Trailer still]

Available from: https://www.instagram.com/p/CbtLxT4tv8L/ [Accessed on: 28 October 2022].

Figure 11. Dyer-Miller, D. (2022) COIN ‘Killing Me’ Spotify Canvas [Spotify Canvas]

Available from: https://open.spotify.com/album/0Ysl8PFnCzqyvjbAhaCMvf [Accessed on: 28 October 2022].

Figure 12 Tesfaye, A. (2020-2021) ‘After Hours’ music video sequence [Music Videos]

Available from: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC0WP5P-ufpRfjbNrmOWwLBQ [Accessed on: 28 October 2022].

Figure 13. Persson, J. (2022) ABBA Voyage concert [Photograph]

At: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/30/arts/music/abba-voyage-review.html [Accessed on: 9 November 2022].

Figure 14. Tesfaye, A. (2020) Still from the ‘Heartless’ music video [Music Video]

Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1DpH-icPpl0 [Accessed on: 9 November 2022].

Figure 15. Tesfaye, A. (2020) Still from a TikTok promoting The Weeknd Live TikTok Experience [TikTok] Available from:

https://www.tiktok.com/@theweeknd/video/6858396074441329925?is_copy_url=1&is_from_ webapp=v1 [Accessed on: 9 November 2022].

Figure 16. Tesfaye, A (2020) The Weeknd TikTok Live Experience, Live stream depicting audience interactivity and participation [Live Stream Video] Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wtIrqoQFsos [Accessed on: 11 November 2022].

Allaire, C. (2021) Billie Eilish Just Switched Up Her Signature Green & Black Hair Vogue, 18 March. Available at: https://www.vogue.co.uk/beauty/article/billie-eilish-blonde-hair [Accessed on: 3 November 2022]

Antoniak, M. et al. (2020) Music sales and artists popularity on social media ResearchGate. pp. 1-22. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347441254_Music_sales_and_artists_popularity_ on_social_media [Accessed on: 29 October 2022].

Blanchet, B. (2022) The Weeknd Kicks Off 2022 with over 700 million Spotify streams in just two weeks. Complex, 17 January. [Blog]. Available at: https://www.complex.com/music/theweeknd-spotify-streams-2022 [Accessed on: 29 August 2022].

Borg, J. (2021) What is a creative director in music? - Music Industry Jargon Busting. AmplifyYou, 1 October. Available at: https://amplifyyou.amplify.link/2021/10/whatis-a-creative-director-in-music-music-industry-jargon-busting/ [Accessed on: 25 June 2022].

Click, M A, & Scott, S. (2018) The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom [eBook]. First Edition. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group Available from: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/bcu/detail.action?pq-origsite=primo&docID=5122937 [Accessed on: 4 October 2022].

Cole, S. (2019) The impact of technology and social media on the music industry. Econsultancy, 9 September. Available at: https://econsultancy.com/the-impact-of-technology-and-socialmedia-on-the-music-industry/ [Accessed on: 19 August 2022].

Crowley, E. (2019) Why Visual Identity is Important (And How to Create Yours) STORIES

Spotify for Artists, 14 November. Available at: https://artists.spotify.com/en/blog/why-visualidentity-is-important-and-how-to-create-yours [Accessed on: 20 October 2022].

Duffett, M. (2014) Popular Music Fandom: Identities, Roles and Practices. [eBook]. London: Routledge. Available at:

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/bcu/reader.action?docID=1546777 [Accessed on: 11 November 2022].

Gesenhues, A. (2019) Has Instagram increased its ad load? Marketers report as many as 1 in every 4 posts are ads MarTech, 26 July. Available at: https://martech.org/has-instagramincreased-its-ad-load-marketers-report-as-many-as-1-in-4-posts-are-ads/ [Accessed on: 5 November 2022].

Herrera, I. (2020) After hours The Weeknd Pitchfork, 24 March. Available at: https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/the-weeknd-after-hours/ [Accessed on: November 7 2022].

Horsburgh, A. (2017) Why the Music Industry Gets Digital so wrong Medium, 24 October. Available at: https://amberhorsburgh.medium.com/why-the-music-industry-gets-digital-sowrong-dd15cfeca5c1 [Accessed on: 29 July 2022]

Horsburgh, A. (2019) Turning Artists into Icons. Medium, 12 November. Available at: https://amberhorsburgh.medium.com/what-does-a-creative-director-do-77922de04d38 [Accessed on: 8 July 2022].

Jackson, S. (2019) Music Cover Design in the Digital Age Dissertation. University of Cincinnati. Available at:

https://www.proquest.com/openview/d062d5e47707bf192eb2d8637121cd0e/1?pqorigsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y [Accessed on: 8 August 2022].

Karen, C et al. (2014) The Oxford Handbook of Interactive Audio [eBook] New York: Oxford University Press. Available from:

https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=tbsBBAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=the +Oxford+handbook+of+interactive+audio&ots=s0xsQFK7PG&sig=ooIpb7CxkU79twgPkub 1YTtRtfE&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=the%20Oxford%20handbook%20of%20interactive %20audio&f=false [Accessed on: 26 September 2022].

Kemp, S. (2022) Digital 2022: Global Overview Report DataReportal [Blog] 26 January. Available at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-global-overview-report [Accessed on: 5 November 2022]

Majewski, G. (2022) How musicians should use Social Media in 2022 DIY Musician [Blog]. 2 February. Available at: https://diymusician.cdbaby.com/music-promotion/how-musiciansshould-use-social-media-in-2022/ [Accessed on: 11 September 2022].

Mazurek, B. (2017) From Kanye to Kings of Leon, Why Artists Need Creative Directors In The Age of Instagram Billboard, 19 April. Available at: https://www.billboard.com/music/musicnews/from-kanye-to-kings-of-leon-why-artists-need-creative-directors-in-7767647/ [Accessed on: 21 October 2022]

McClinton, D. (2019) Global attention span is narrowing and trends don't last as long, study reveals. The Guardian. [Online]. 17 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/apr/16/got-a-minute-global-attention-span-isnarrowing-study-reveals [Accessed on: 19 August 2022].

McErlean, K. (2018) Interactive Narratives and Transmedia Storytelling: Creating Immersive Stories Across New Media Platforms [e-Book] New York: Focal Press. Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/bcu/detail.action?docID=5323303 [Accessed on: 11 September 2022].

McCue, T.J. (2019) Verizon Media Says 69 Percent Of Consumers Watching Video With Sound Off. Forbes, 31 July. Available at:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/tjmccue/2019/07/31/verizon-media-says-69-percent-ofconsumers-watching-video-with-sound-off/?sh=68a2632735d8 [Accessed on: 22 October 2022].

Miller, C H (2019) Digital Storytelling: A Creator's Guide to Interactive Entertainment Fourth Edition [e-Book] Milton:Taylor & Francis Group. Available from: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/bcu/detail.action?docID=5981894# [Accessed on: 24 September 2022].

Nolfi, J. (2022) The Weeknd: After Hours Nightmare haunted house heading to Universal’s Halloween Horror nights. Entertainment Weekly. [Blog]. 26 July. Available at:

https://ew.com/music/the-weeknd-after-hours-nightmare-universal-halloween-horror-nights/ [Accessed on: 11 November 2022].

Pearson, H. & Wilbiks, J. (2021) Effects of Audiovisual Memory Cues on Working Memory Recall, Vision, vol. 5(1): 14. pp. 1-10. Available at https://doi.org/10.3390/vision5010014 [Accessed on: 26 September 2022].

Roizin, E. & Wang, M. (2021) X-Reality (XR) and Immersive Learning: Theories, Use Cases, and Future Development. In: IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology & Education (TALE) [Online]. 2021. Piscataway: IEEE. pp. 751-754. Available at:

https://ieeexplore-ieee-org.bcu.idm.oclc.org/document/9678595 [Accessed on: 11 November 2022].

Stocchetti, M. & Gomez-Diago, G. (2016) Storytelling and Education in the Digital Age, Experiences and Criticisms.From Storytelling to Storymaking to Create Academic Contents. Creative Industries Through the Perspective of Students [eBook]. Frankfurt am Main: PL Academic Research. Available at:

https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/25819/1004270.pdf?sequence=1# page=149 [Accessed on: 29 July 2022]

Tan, S.-L. et al. (2013) Psychology of Music in Multimedia. [e-Book]. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at:

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/bcu/reader.action?docID=1336479&ppg=34 [Accessed on: 26 September 2022]

Tesfaye, A. (2022) Dawn FM Trailer. [Video] Youtube. Available at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u5IrGXTpSkc [Accessed on: 17 September 2022].

The Weeknd x The Dawn FM Experience [Feature Film] Directed by Micah Bickham. Amazon Prime Video (2022) 34 mins.

TikTok Newsroom (2020) The Weeknd Experience, an innovative TikTok LIVE stream, draws over 2 million unique viewers. 12 August. Available at: https://newsroom.tiktok.com/enus/the-weeknd-experience-an-innovative-tiktok-live-stream-draws-over-2-million-uniqueviewers [Accessed on: 11 November 2022].

Walton, T. & Evans, M. (2018) The role of human influence factors on overall listening experience. Quality and User Experience, vol. 3(1). pp. 1-16. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41233-017-0015-4 [Accessed on: 26 September 2022]

Willman, C. (2022) Music Streaming Hits Major Milestone as 100,000 songs are uploaded Daily to Spotify and other DSPs Variety, 6 October. Available at: https://variety.com/2022/music/news/new-songs-100000-being-released-every-day-dsps1235395788/ [Accessed on: 8 November 2022].

Wise, J. (2022) How many pictures are on Instagram in 2022? Earthweb, 28 July. Available at: https://earthweb.com/how-many-pictures-are-on-instagram/ [Accessed on: 8 November 2022].

Van Dessel, P. et al. (2017) The Mere Exposure Instruction Effect: Mere Exposure Instructions Influence Liking. Experimental psychology, vol. 64 (5) pp. 300-314. Available at: https://web.p.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=996259dd-8743-4e32b0ff-eee29f61e44b%40redis [Accessed on: 20 October 2022]

Vlasak, C. (2021) Graphic Design In The Music Industry: An Interview With Jack McArdle Of AAA & Skinterest. FUXWITHIT. [Blog]. 13 July. Available at: https://fuxwithit.com/2021/07/13/graphic-design-in-music-industry-aaa-skinterest-interview/ [Accessed on: 20 August 2022]

Vorhees, N. (2020) The importance of Graphic Designers in the music industry Inkbot Design [Blog]. 5 November. Available at: https://inkbotdesign.com/graphic-designers-musicindustry/ [Accessed on: 11 September 2022]

Bill Green

Bill Green