“Our political system is designed for vigorous disagreement. It is not designed for irreconcilable contempt.”

THE

RFK

THE

WHY

60

DEPOLARIZING

TAKE

“Our political system is designed for vigorous disagreement. It is not designed for irreconcilable contempt.”

RFK

THE

WHY

60

TAKE

We have 11 perfect venues for your event.

THISISTHEPLACE.ORG/RENTALS

Klein is an author and columnist for The New York Times, where he also hosts “The Ezra Klein Show” podcast. He was a former columnist and editor at The Washington Post before he co-founded Vox, where he was also editor-at-large. An excerpt from his book “Why We’re Polarized” is on page 60.

Biandudi Hofer heads HBH Enterprises, a media group that explores issues through a solutions oriented lens, and is a co-founder of Good Conflict. She is an award-winning journalist, documentary filmmaker and producer who has worked with CBS, NPR and PBS. Her essay on finding common ground is on page 40.

Cox is governor of Utah and chairman of the National Governors Association. He was elected as governor in 2020 after serving as lieutenant governor for seven years. He has been a state legislator, county commissioner, city councilman and mayor. His essay on disagreeing better is on page 36.

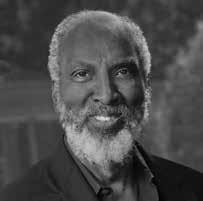

Powell is a professor of law, African American studies and ethnic studies at the University of California, Berkeley, and the director of the Othering and Belonging Institute. His most recent book is “Racing to Justice: Transforming our Concepts of Self and Other to Build an Inclusive Society.” His essay is on page 42.

A leading expert on helping democracies improve, Kleinfeld is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Before joining Carnegie, she spent a decade co-founding and directing the Truman National Security Project. The author of three books, her essay on reducing political polarization is on page 38

Wood is national ambassador for Braver Angels, a former GOP nominee for Congress and past vice-chairman of the Republican Party of Los Angeles County. An opinion columnist for USA Today, he also speaks on issues of political and racial reconciliation. His commentary on bridging differences is on page 15.

In one of American cinema’s more haunting scenes, two cars careen toward a cliff in the 1955 coming-of-age drama “Rebel Without a Cause.” The game of chicken means the first driver to bail before the cars barrel over the cliff loses. The film’s famous scene ends in tragedy.

“As played by irresponsible boys,” the British intellectual Bertrand Russell once observed, “this game (of chicken) is considered decadent and immoral, though only the lives of the players are risked.” But, he continued, when such games are played “by eminent statesmen” or politicians, too often they’re considered displays of “wisdom and courage.”

Increasingly, the nation’s political parties are caught in what seem like perpetual games of chicken as each party seeks advantage over the other with no intention to swerve first. Whether the issue is national debt, immigration, health care or national defense, the focus of each party is as much about humiliating the other party as it is about crafting bipartisan policies that work for the vast majority of Americans.

While there’s certainly wisdom in competing parties serving as a check on one another and providing a robust contest of ideas, the levels of contempt and political brinksmanship in recent years is corroding the country and putting the union itself at risk.

In this special double issue of Deseret Magazine, we’ve assembled a variety of preeminent thinkers actively seeking to address America’s polarization problem.

Hélène Biandudi Hofer, journalist and co-founder of Good Conflict, points to the power of story to change our perspective and bring us closer together (page 40). John Wood Jr., a national leader

with Braver Angels, details why Americans need to start seeing each other as family rather than foe (page 15).

Gov. Spencer Cox, Utah’s 18th governor, details his nationwide “Disagree Better” initiative, launched as Cox serves this year as president of the National Governors Association (page 36).

Ezra Klein (page 60) and Rachel Kleinfeld (page 38) outline discrete actions individuals can take to depolarize while Yascha Mounk points to how lowering the stakes of political competition might lead to more unity (page 64).

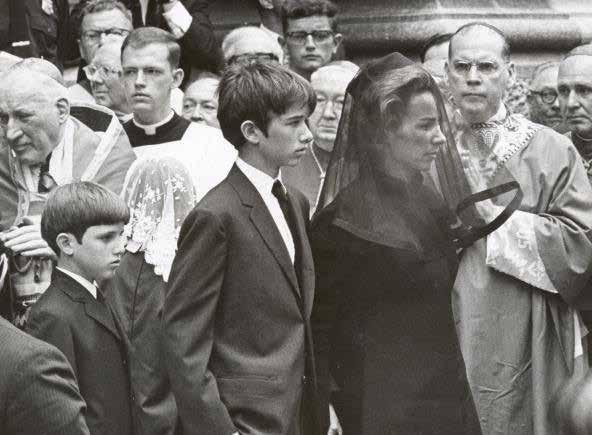

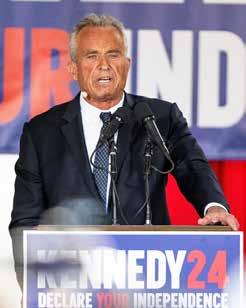

Hyrum Lewis explores the myth of the left and right (page 52), and Michael Mooney provides a window into the controversial presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr., whose run for office represents a swath of Americans whose political lines are increasingly scrambled in ways that don’t easily fit in the Republican-Democrat paradigm (page 46).

The takeaway: There is a path out of the perpetual game of chicken. It won’t be easy, but it starts with each American. It starts with more constructive dialogue, better disagreeing, more listening and understanding, and individual decisions to treat our political opponents with greater dignity and trust, or, in the words of Wood, like they’re family.

As Abraham Lincoln asserted, perhaps naively, at the nadir of the nation’s polarization on the brink of civil war: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection.”

This issue offers the hope that such bonds of affection are still within our reach.

LOIS M. COLLINS, KELSEY DALLAS, JENNIFER GRAHAM

ART DIRECTORS

IAN SULLIVAN, BRENNA VATERLAUS

COPY EDITORS

SARAH HARRIS, VALERIE JONES, LOREN JORGENSEN, CHRIS MILLER, TYLER NELSON

DESERET MAGAZINE (ISSN 2537-3693) COPYRIGHT © 2024 BY DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. IS PUBLISHED MONTHLY EXCEPT BI-MONTHLY IN JULY/AUGUST AND JANUARY/FEBRUARY BY THE DESERET NEWS, 55 N 300 W, SUITE 400, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH. TO SUBSCRIBE VISIT PAGES.DESERET.COM/SUBSCRIBE. PERIODICALS POSTAGE IS PAID AT SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH

POSTMASTER: PLEASE SEND ADDRESS CHANGES TO PO BOX 2220, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH 84101.

PUBLISHER

BURKE OLSEN

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER

DAVID STEINBACH

VICE PRESIDENT MARKETING

DANIEL FRANCISCO

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT SALES

TRENT EYRE

VICE PRESIDENT SALES

SALLY STEED

PRODUCTION MANAGER

MEGAN DONIO

OPERATIONS MANAGER

BRITTANY M C CREADY

DIRECTOR OF CIRCULATION

SYLVIA HANSEN

THE DESERET NEWS’ PRINCIPAL OFFICE IS 55 N. 300 WEST, STE 400, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH.

COPYRIGHT 2024, DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA.

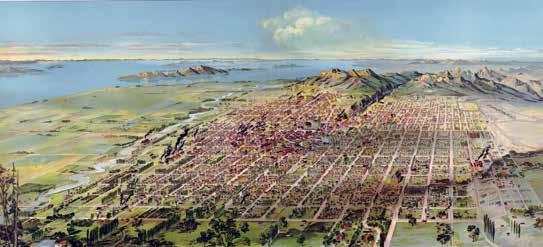

PROPOSED AS A STATE IN 1849, DESERET SPANNED FROM THE SIERRAS IN CALIFORNIA TO THE ROCKIES IN COLORADO, AND FROM THE BORDER OF MEXICO NORTH TO OREGON, IDAHO AND WYOMING. INFORMED BY OUR HERITAGE AND VALUES, DESERET MAGAZINE COVERS THE PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF THAT TERRITORY AND ITS INTERSECTION WITH THE BROADER WORLD.

The NOVEMBER issue served as a primer for the 2024 presidential election season. An exclusive excerpt from McKay Coppins ’ biography of Sen. Mitt Romney, who stunned voters and political observers on both sides of the aisle by announcing he will not run for a second term, revealed how the 2012 GOP presidential nominee’s faith defined his political career and may have ended it (“The Making of Mitt Romney”). But reader Shane Doyle disagreed with that premise. “What brought it to an end was that people voted for a conservative, only to discover he’s a liberal in disguise. Most of the people in Utah, especially those who voted for him, will be happy to see him gone. And please, Mitt, don’t come back.” Others were conflicted over Romney’s tenure in the Senate. “Even though I am disappointed in some of Mitt Romney’s political actions or inactions in Congress, I am very impressed with this excerpt and book by McKay Coppins,” Boyd Nuttall wrote. “The political decisions and choices (Romney) made in the past are behind him. He can start a new life in a year … and I wish him and his family well going forward.” Our cover story focused on faith, exploring how it has informed the Republican, Democratic and independent men and women seeking the highest office in the land (“Faith and the Candidates”). Many readers questioned the religious sincerity of those running — some of whom have dropped out of the race since our story published — and whether faith should be a factor in deciding who to vote for. “I don’t trust politicians. They will say whatever they have to say to get elected,” wrote Dennis Hobb. “But it would sure be nice if we could find some who have the moral courage to be honest. To me that is what matters and what is so elusive in politics today.” An issue that neither Congress nor the White House seems willing or able to tackle is deficit spending that contributes to mounting government debt. Economist Michael Kofoed’s essay argued that the House and Senate must reclaim their authority over spending from the executive branch if they want to reign in deficits (“Power of the Purse”). Reader Jim Fikar sees another solution that goes beyond the beltway. “The only way to change things is to get big money out of politics. … Our Congress will do the wrong things for America and Americans if they conflict with the wishes of their big money donors. They are virtually taking bribes to sell out the best interests of our country and its citizens. That should be illegal.”

“I don’t trust politicians. They will say whatever they have to say to get elected.”

AGAINST ALL ODDS

HERON ISLAND, QUEENSLAND, AUSTRALIA

PHOTOGRAPHY BY HANNAH LE LEU

A Green Sea Turtle hatchling cautiously surfaces for air to a sky of hungry birds. This hatchling must battle through the conditions of a raging storm while evading a myriad of predators.

Not only has a tropical storm brought out thousands of circling birds, but there are also patrolling sharks and large schools of fish on the hunt for baby turtles. Only 1 in 1,000 of these hatchlings will survive.

IMAGE FROM VITAL IMPACTS

What was the moment that made you want to bridge the divide?”

The first time I remember being asked that question was in a meeting of Braver Angels leadership, several years ago. Braver Angels, for which I serve as national ambassador, is America’s largest grassroots organization dedicated to the depolarization of American politics and civil society. In searching my memories for a moment that might explain my passion, I rewound past my campaign for California’s 43rd Congressional District, past my early forays into political activism, past arguments in college and high school, past Barack Obama versus the tea party movement, George Bush and 9/11, Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky.

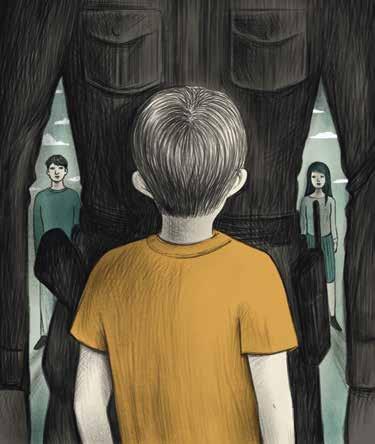

Finally, my mind fell upon a memory that it had not touched for many years. A memory of myself as a little boy listening to my mother and father screaming at each other in our living room, as they too often did. A memory of myself rushing to stand in the space between them, covering my ears with my hands and pleading with them to stop screaming at each other.

My parents’ differences did not arise out of politics per se. But being from not just different races but from different classes, different regions, different generations and different ways of seeing the world, their divisions clashed in ways that proved irreconcilable. Like many children who find themselves the victims of divorce, my brother and I found ourselves locked in a cold war between Mom

and Dad for years. But for all of their differences with each other, their love for their children was beyond question.

This led me to wonder to myself, how could two people with so much love inside of them fail to love each other? The villain, I decided, was in some deep misunderstanding. The antidote was in understanding. I carried this attitude with me throughout life right into politics. So in an age where Democrats and Republicans view each other as the enemy, I cannot help but see them as merely Mom and Dad.

I shared that perspective on the campaign trail in 2014 as California’s youngest active nominee for Congress and running against incumbent Rep. Maxine Waters. Whether I was speaking to a predominantly white tea party club in South Bay, L.A. County, or to a predominantly Black and Democratic leaning church in South Central Los Angeles, the question of my qualifications for representing such a complex community would arise. My answer to all audiences began with my life experience.

“I come from an interesting family background,” I would say. “My mother is a liberal Black Democrat from inner-city Los Angeles, and my father is a conservative white Republican from Tennessee. I grew up explaining my mother to my father and my father to my mother and that’s why I think I can represent all of you.”

I didn’t win that race, but I have spent most of my 37 years in and around politics with a singular, overarching goal: normalizing understanding and rebuilding trust between combatants across the partisan divide. I am not the only one. Though we live in an age defined by deepening distrust exacerbated by new technologies, bad incentives and genuine challenges domestically and around the globe, a modest movement of Americans representing organizations, platforms and communities from every corner of the country are trying to reset the table.

Many of us in that movement believe if we can understand the humanity underlying our differences we can remember how to love each other. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. taught that agape love (God’s love) was a spiritual power that could affect social transformation. It was this spirit that powered the mainstream of the civil rights movement.

But love is an axiomatic commitment. If America is to move to the next chapter of her story, we must think of America as a family — a family that through love and goodwill can hold together.

We are divided by politics, race, class, generations and many things that cast a dark shadow upon the future of the American experiment. Each is its own part of the riddle. But the answer to this deep societal cancer of polarization must begin with a certain remembrance — that we as Americans are like a family. We didn’t choose each other. But we can choose to love each other. For no family can stand if it does not remember to love.

JOHN WOOD JR. IS A NATIONAL LEADER FOR BRAVER ANGELS AND A FORMER VICE CHAIRMAN OF THE REPUBLICAN PARTY OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY.CREDIT CARD DEBT is an ever-present worry for millions of Americans. The average cardholder carries around $6,000 in debt, enough to pay for a few months’ rent most anywhere in the country. But those everyday worries and spending habits soar to meteoric heights during the holiday season. In 2022, the average consumer spent more than a thousand dollars on holiday related purchases — about 70 percent of which was paid through credit cards. And with credit card debt now at an all-time high of more than $1 trillion across the country, festive spending is expected to once again burrow borrowers deeper into debt as we enter the new year.

—Natalia GaliczaThe first recorded version of credit appeared on clay tablets in ancient Mesopotamia. The Archaeological Institute of America reports Mesopotamians chiseled letters, contracts, credits and

debits onto the tablets to account for trade with other civilizations. Closer to our present use of credit cards are “Metal Money” and “Charga-Plates,” which circulated in the 20th century as lines of credit for consumers. They looked like miniature license plates and dog tags that shoppers would tote from store to store. Plastic cards first appeared in 1959, and they’ve stuck while incorporating magnetic strips, chips and tap technologies to record our spending.

Any interest rate advertised by credit card companies to entice new customers is only effective for the first year the card is issued — or half that time if the rate is part of a promotion. After a year, most card issuers

can alter the interest rate at any time, so long as card users receive a 45-day notice. And since many of the top banks that offer credit cards in the United States are federally chartered, they do not have to abide by state laws meant to limit interest rate swings.

That’s how long card users have to submit a late payment before suffering any consequences to their credit score. Creditors can only report a late payment to credit bureaus if that payment is 30 days past due, though other

penalties like late fees may still apply. Complying with this grace period is especially important considering a late payment lingers on credit reports for up to seven years.

718

This is the average credit score in the United States. Credit scores quantify the trustworthiness of a borrower or the likelihood that they will repay debts on time. The higher the score, the more likely a bank or financial institution will extend credit to a borrower for a car, home, insurance or other long-term investment. A good credit score in the United States typically ranges from 670 to 739. Not all countries use credit scores, and

“THERE IS A HUGE AMOUNT OF EVIDENCE THAT SUGGESTS PEOPLE ARE PRESENT-BIASED. THEY DON’T FULLY WEIGH THE FUTURE CONSEQUENCES OF THEIR ACTIONS. BORROWING IS THE MOST NATURAL MANIFESTATION OF OUR TENDENCY AS HUMANS TO PRIORITIZE SHORT-TERM PLEASURE OVER LONG-RUN CONSEQUENCES.”

NEALE MAHONEY, PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY AND RESEARCH ASSOCIATE AT THE NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

some — like Japan, the Netherlands and Spain — measure credit through factors like income and employment history instead.

Retailers would directly issue credit to consumers until post-World War II, when dramatic economic growth prompted demand for a national credit.

According to the Federal Trade Commission, whether or not credit was extended by the local store depended largely on personal relationships between shopper and seller. That changed in the 1950s, when financial institutions got in on the action, introducing credit cards that could be used nationwide. Now more than 67 percent of adults have at least one credit card.

70 MILLION

That’s how many credit card accounts have been opened in the U.S. since pre-pandemic 2019. The widespread

use of plastic to pay for goods points to why credit card debt is the most common form of household debt for Americans, who owe about $6,000 on average. A 2023 Bankrate report found that 47 percent of credit card holders struggle to pay off their monthly balance, instead they roll credit balances over from month to month, accruing interest and fees on the unpaid balance.

The most borrowers should charge their credit cards every month, regardless of their credit limit, is one-third of their available credit. Anything more will produce a “significantly negative impact on credit scores,” warns the credit bureau Experian. The percentage of credit an individual uses every month is called a credit utilization rate, and the average rate in 2022 was 28 percent in the United States.

TOP 10 COUNTRIES WITH THE HIGHEST RATE OF CREDIT CARD OWNERSHIP (IN ORDER):

83%

79%

74%

72%

70%

69%

68%

SOUTH KOREA

67%

67% 65%

ADAM SMITH WAS NOT an economist. Capitalism’s forefather was, instead, a moral philosopher who spent much of his time pondering human nature. His most enduring insight was that a people free to work for their own self-interest would meet the needs of the larger society; that an unrestricted, competitive market — as opposed to the government-protected mercantilism of his time — would empower workers and consumers alike. His theory would eventually dominate the world’s major economies for nearly 250 years; but lately, cracks have appeared in popular support for America’s capitalist foundation. A 2021 Axios poll found that only 42 percent of adults ages 18 to 24 held a positive view of capitalism, while 54 percent saw it negatively — and that view crosses party lines. That same year, just 66 percent of Republicans, 18 to 34, saw capitalism as a positive force, down from 81 percent in 2019. Is it time to rethink the system Smith built?

—ETHAN BAUERWINSTON CHURCHILL once said that “democracy is the worst form of government except for all those other forms.” The same could be said of capitalism. Though imperfect, it’s the best method for combating poverty and allowing people the best chance to find financial stability and success. It’s also the best system for countering stagnation by incentivizing growth and innovation. Even self-proclaimed socialists are often not mad at capitalism itself as much as adjacent policies, like lacking social safety nets and rising inequality, that could be fixed without abandoning capitalism.

THE GREAT IMMIGRATION challenge of our era is not at the borders but inside them. It’s not who gets in, but what happens once they’re here. As Congress remains gridlocked, why not let states decide how the foreign-born get to belong? Consider education, abortion, health care, gun control and marijuana. States blue and red are going their own way on all these issues, often in conflict with one another and sometimes with Washington.

It is already happening, but the question is how much power over immigration will eventually devolve to the states. They can create a fragmented landscape of places that welcome immigrants and others that close their doors. And within that patchwork, we might eventually end up with a federal policy that works.

States differ in the access to health care and safety-net programs they make available to immigrants. Dreamers — unauthorized immigrants who arrived as children — are welcomed into public higher education in some states but shunned in others. Some make it easier for professionals trained abroad to get licenses; others make it harder. As states diverge further, immigrants would choose to settle in welcoming places and avoid unfriendly places.

The data validates capitalism’s effectiveness: Since it became the dominant economic philosophy around the world, extreme poverty has declined by orders of magnitude. In 1820, according to economists from the University of Paris, 84 percent of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty. That dropped to 66 percent in 1910 and by 2018 it was down to 8.6 percent. The reason capitalism “brought about the greatest reduction of poverty in human history,” writes New York Times columnist David Brooks, is simple: Compared to centrally-planned economies, capitalism is much more adaptable. “Capitalism creates a relentless learning system,” Brooks, who once identified as a socialist, wrote. “Socialism doesn’t.”

States differ in the access to health care and safety-net programs they make available to immigrants. Dreamers — unauthorized immigrants who arrived as children — are welcomed into public higher education in some states but shunned in others. Some make it easier for professionals trained abroad to get licenses; others make it harder. As states diverge further, immigrants would choose to settle in welcoming places and avoid unfriendly places.

Where socialism excels, Brooks argues, is in incentivizing corruption and cronyism among government officials. When their plans fail and goods become scarce, abuse becomes inevitable because they hold all the power. “A system that begins in high idealism,” he writes, “ends in corruption, dishonesty, oppression and distrust.” To be fair, capitalism can be ripe for abuse, too, Brooks acknowledges.

The United States can have only one form of citizenship, but states can compete over access to the world’s best brains, to the people who will care for aging boomers and to young adults with years ahead of them to pay taxes and bear children. Americans and their marketplaces have a way of sorting these things out.

ADAPTED FROM AN OP-ED IN THE NEW YORK TIMES BY ROBERTO A. SURO, A PROFESSOR OF JOURNALISM AND PUBLIC POLICY AT USC ANNENBERG,

SPECIALIZING IN IMMIGRATION AND THE LATINO POPULATION.But the answer to that abuse, he insists, is not another plan, but better capitalism. “Markets are morally neutral,” writes BYU economics professor Phillip J. Bryson. That neutrality means they can be tweaked to benefit everyone. “A big mistake those of us on the conservative side made was to think that anything that made the government bigger also made the market less dynamic,” Brooks writes, citing countries like Denmark and Finland as examples of wide-open markets that also have policies to help spread the wealth. “The only reason they can afford to have generous welfare states,” he adds, “is they also have very free markets.”

THE GREAT IMMIGRATION challenge of our era is not at the borders but inside them. It’s not who gets in, but what happens once they’re here. As Congress remains gridlocked, why not let states decide how the foreign-born get to belong? Consider education, abortion, health care, gun control and marijuana. States blue and red are going their own way on all these issues, often in conflict with one another and sometimes with Washington.

It is already happening, but the question is how much power over immigration will eventually devolve to the states. They can create a fragmented landscape of places that welcome immigrants and others that close their doors. And within that patchwork, we might eventually end up with a federal policy that works.

SINCE THE PRESIDENCY of John F. Kennedy, American wages (accounting for inflation) have been stagnant, while the wealthiest 10 percent of Americans — the top 1 percent, especially — have expanded their share of the nation’s wealth. University of California, Berkeley, economics professor Gabriel Zucman wrote that income inequality was worse in America in 2019 than it was in the period that preceded the Great Depression. Millennials are the first generation of Americans since the 1930s who are worse off than their parents in taking the first steps toward accumulating wealth. Despite being the most highly educated generation, many millennials don’t have the financial capability to save money for a home or retirement like their parents did. Amid skyrocketing housing prices, food prices, interest rates and mounting student debt, the American dream of hard work begetting opportunity has instead become a social media rallying cry of “Eat the rich!”

States differ in the access to health care and safety-net programs they make available to immigrants. Dreamers — unauthorized immigrants who arrived as children — are welcomed into public higher education in some states but shunned in others. Some make it easier for professionals trained abroad to get licenses; others make it harder. As states diverge further, immigrants would choose to settle in welcoming places and avoid unfriendly places.

Beyond economic impacts, so-called “late capitalism” — a term generally denoting modern capitalism dominated by multinational corporations and concentrated wealth — has also commercialized many aspects of existence. In “24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep,” Columbia University art professor Jonathan Crary explores how capitalistic impulses to spur growth and innovation will stop at nothing. “Because capitalism cannot limit itself,” he writes, “the notion of preservation or conservation is a systemic impossibility.”

States differ in the access to health care and safety-net programs they make available to immigrants. Dreamers — unauthorized immigrants who arrived as children — are welcomed into public higher education in some states but shunned in others. Some make it easier for professionals trained abroad to get licenses; others make it harder. As states diverge further, immigrants would choose to settle in welcoming places and avoid unfriendly places.

Billionaire hedge fund manager Ray Dalio, an outspoken critic of capitalism’s weaknesses, says the system’s proponents have two choices. “All good things taken to an extreme become self-destructive,” he wrote in 2020, “and everything must evolve or die.”

The United States can have only one form of citizenship, but states can compete over access to the world’s best brains, to the people who will care for aging boomers and to young adults with years ahead of them to pay taxes and bear children. Americans and their marketplaces have a way of sorting these things out.

ADAPTED FROM AN OP-ED IN THE NEW YORK TIMES BY ROBERTO A. SURO, A PROFESSOR OF JOURNALISM AND PUBLIC POLICY AT USC ANNENBERG, SPECIALIZING IN IMMIGRATION AND THE LATINO POPULATION.

According to some researchers, the evolution has already taken root. Rather than the “neoliberal” capitalism evangelized by figures like Ronald Reagan, which favors deregulation, large corporations and low taxes on the wealthy, the so-called “New Economics” promoted in a November report by the progressive Roosevelt Institute describes a movement toward worker empowerment, higher taxes on the wealthy and more government influence. “Whether or not this new approach marks a long-lasting shift remains to be determined,” the report’s authors wrote, “and whether this shift goes far enough depends on the outcome of politics and policy fights ahead.”

Mary came into our lives like she was always meant to be there. She befriended my mom while they both worked at United Cerebral Palsy in Los Angeles before I was born. I don’t remember how, but somewhere along the line, she became my Aunt Mary, earning a blood-relation moniker. I always knew she wasn’t one of my parents’ sisters, but we didn’t care. Our Aunt Mary was younger than my folks, had more energy to focus on us when she was around, and she was cool. Like, so cool.

Aunt Mary was a disability advocate in the ’70s, graduated from Harvard Business School in the ’90s (she is still the only person I know well who went to Harvard), waited to marry until she was in her 30s, and unapologetically kept her last name. I recognize that those life choices were not super cutting-edge in America in the ’80s and ’90s, but they were in my household. My family unit was held together with a glue of rigidity. Looking back on it as an adult, I realize the glue was the type that would fail without watchful, angry attention.

Somehow, Aunt Mary thrived outside of the narrow definition of what I was taught a woman should be like. She married Pat, a former ski bum and wildland firefighter. At age eight, I thought Pat was the coolest

guy I had ever met. I was a groomsman at their wedding. They gave me the mic and let me sing “Ice, Ice, Baby” on the dance floor. My brother and I don’t remember Aunt Mary advocating for her lifestyle, she was just always there for us to speak to — a listening ear we could trust. In those early

REGARDLESS OF WHAT A CHILD’S HOME LIFE LOOKS LIKE, THERE ARE BENEFITS OF HAVING THE CARE AND PERSPECTIVE OF A SUPPORTIVE NONPARENTAL ADULT.

years, she offered a solid place to land that looked different from home.

Regardless of what a child’s home life looks like — even kids like me who come from a traditional, middle-class American family — there are benefits to having the care and perspective of a supportive nonparental adult, or SNPA , in academic

research. A study published in the American Journal of Community Psychology suggests that the existence of SNPA s in adolescents’ lives as they grow up leads to positive outcomes in academic functioning, self-esteem, and behavioral and emotional health. The research brings together a broad range of examinations that prove points that anyone with an Aunt Mary knows: like how profound it can be to talk to an adult about all of the things you are scared to talk to your parents about or how having a person who offers you compliments outside of a parental structure can boost your self-esteem.

This isn’t to suggest that there is anything simple about how impactful an adult who has no biological interest in treating you as one of the most important people in their lives can be. I don’t have a clear memory of Aunt Mary giving me a pep talk that changed the trajectory of my life or a low point she lifted me up from; I just remember someone who I looked up to always making me feel like the most important kid in the room.

Now, decades later, with a career, a marriage, a child of my own — and a serendipitous friendship my wife, Sarah, and I have with a young woman named Mary — my

I DON’T HAVE A CLEAR MEMORY OF AUNT MARY GIVING ME A PEP TALK THAT CHANGED THE TRAJECTORY OF MY LIFE OR A LOW POINT SHE LIFTED ME UP FROM; I JUST REMEMBER SOMEONE WHO I LOOKED UP TO ALWAYS MAKING ME FEEL LIKE THE MOST IMPORTANT KID IN THE ROOM.

daughter Josie also has her own chosen Aunt Mary.

Josie’s Aunt Mary was our only friend who came to the hospital when Josie was born. Josie came nearly a month early and we didn’t know the protocol for inviting visitors. We were too blissed out on oxytocin to care. Mary (Josie calls her Meemee) figured out how to get in on her own and walked in, smiling. “Oh my gosh, you have a baby!” she said. She stayed for under an hour and left. We had no idea she was going to play an outsized role in Josie’s life.

Meemee lived on a farm in southern Oregon during the height of the Covid pandemic. Sarah, Josie and I podded up with her and her partner, Dominic. When schools, day cares and camps were closed, Meemee and Dominic became our child care. Through all of the stress, chaos and unknowns, I knew Josie was safe and happy on the farm with her Aunt Meemee. I’d drop off my child in the morning and in the afternoon, I’d pick up a ruddy-cheeked, wildly dirty cherub who was uncomfortably full of cherry tomatoes. In a world filled with misinformation and fear, I knew I could drop Josie off at a simple place where she could watch things grow and also grow with the love of her Aunt Meemee.

Josie isn’t the only member of our family to benefit from Aunt Meemee’s solid love. Mary was the first friend I told when I was coming unraveled after Sarah and I experienced our second pregnancy loss when Josie was three. One Father’s Day weekend, Meemee joined us to go camping and asked how I was doing. I opened up in a way that’s not typical for me, and yet it came out organically — the surprising way these emotional dumps untether when you feel safe and at peace in someone else’s presence.

Meemee’s love and care for Josie had not only made her more like a parental figure for my daughter, but also like a sister for me. A bigger support group offers, well, more support for everyone. To paraphrase the aforementioned study, throughout our lives, we are surrounded by social networks, which, in

turn, directly affect our individual well-being, by both bringing good to us and helping create a buffer to keep the bad stuff away.

I haven’t seen my Aunt Mary in eight years, but last I checked, she’s still doing as amazing as ever. I still look up to her. She and Pat live in a house they bought in Silicon Valley years before the tech industry sent property values to the moon. The last time I stopped by, I gave her very little notice, but she casually made one of the best salmon dinners I’ve had in my life. I laughed until my stomach hurt with her, Pat and their daughter, who, at the time, was finishing up her senior year of high school. I don’t know if my family’s life will look like theirs, but I know I will be happy if Sarah and I can open our doors and host dinners like that one when my daughter is a young adult.

I want to be a good father to Josie more than anything else in my life. I also know that sometimes I don’t get things right as a dad. Despite my best efforts, a rigidity creeps back into my actions; the residual patterns of the household I was raised in. I see myself passing those same patterns on to my impressionable and very sweet daughter. In a way, it feels like watching something bad happen to a beloved character in a movie multiple times. You watch it play out from your couch, hoping the character won’t make that same mistake again — that one that will undoubtedly cause calamity later in the film.

I don’t want Josie to feel trapped in the loop of creating a life that looks like mine. I don’t want her to feel like she has to follow the rules I created — despite my best efforts — that don’t make sense. I honestly have no idea how I am going to do that, but maybe the answer is that I don’t have to. Maybe the Aunt Marys can.

I hope that Meemee has children of her own, so I can be there for them in the same way she’s been here for Josie. I feel like I already love them and plan to embrace the changes that will come when her favorite kid in the world is no longer my daughter. And I hope they call me Uncle Joe.

Jim Laybourn was up before the sun. It was springtime, around 5 a.m., and the birds were lively, but otherwise, Grand Teton National Park was all quiet and most people staying at the historic Jackson Lake Lodge were still asleep. This was 2006, when pre-dawn starts for a day’s outing in the national park weren’t the requirement they are today. Laybourn’s groggy-eyed clientele wondered why they were leaving so early. They wanted to see grizzlies, though, and back then, if you wanted to see a grizzly, you drove north to Yellowstone.

The Tetons have always been a rich habitat for wildlife — elk, bison, black bears, moose — and grizzlies once roamed these mountains, too. But by 1975, when the grizzly was added to the endangered species list, the bears had disappeared from the Tetons altogether. At the time, biologists in the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem counted only 136 of them, all in Yellowstone National Park. That’s why Laybourn, a wildlife guide, was packing his brown 1997 GMC Suburban so early that spring morning.

After everyone on the wildlife tour had buckled their seatbelts, Laybourn slid into

the bench seat behind the steering wheel and drove out of the lodge’s covered parkway. But just as he turned onto the highway junction, Laybourn saw something move. Out of the darkness, a mother grizzly and three cubs stepped onto the road. Laybourn

THERE’S A DEEP, INNATE PART OF US THAT WANTS TO BELIEVE WE ARE STILL CONNECTED TO WILD PLACES AND CREATURES, DESPITE THE WAYS MODERN DEVELOPMENT BUFFERS US FROM THAT WORLD.

was stunned. He had no idea grizzlies were living in Grand Teton National Park, let alone a mother with three cubs.

“I knew that was something special right there,” he says.

The grizzly Laybourn saw that morning is often said to be the most famous grizzly in the world. She’s easily recognized by the

millions of people who visit Grand Teton National Park. Over the years, her many fans and admirers have followed her story through its highs and lows, celebrating when she emerges from hibernation in the spring with a new litter of cubs, mourning her losses, and awaiting with suspense in moments of uncertainty. She’s a beautiful bear, with a streak of blonde fur hugging her shoulders. But the official way to identify her is by the number on the tag that biologists gave her when she was five years old. She is known as Grizzly 399.

The reason why 399 is so famous is that she has lived close to humans for most of her life, giving the public a rare glimpse of her day-to-day routines, allowing us to watch as she’s raised generations of cubs — teaching them how to forage for food and navigate across the landscape. As far as biologists know, she’s birthed 18 cubs in her 27 years. Last spring, she made headlines when she emerged from hibernation with her newest cub, making her the oldest known female grizzly to reproduce in the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem.

Conservationists call her an ambassador

GRIZZLY 399’S RELATABILITY CAN BE DECEIVING. IT’S ALL TOO EASY TO FORGET THAT SHE IS WILD, UNPREDICTABLE AND HAS LIMITS TO HER TOLERANCE.

for her species. She was among the first grizzlies to return to Grand Teton National Park, becoming the face of the Endangered Species Act’s success. To some, she’s now the face of its shortcomings during a pivotal moment for grizzly bears in America.

After 49 years, state officials in Montana, Wyoming and Idaho are now seeking to remove grizzlies from the endangered species list and lift their protections. This February marks the end of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s one-year review period for considering the delisting, and a decision will be made. The overall grizzly population remains under 2,000 today — an impressive recovery from 136, but a far cry from the estimated 50,000 that lived in North America, with habitat stretching from Alaska to Mexico in the early 1800s. In an attempt to restore some of that original habitat, federal agencies drafted and released a plan in October to reintroduce grizzlies to Washington, near North Cascades National Park.

Tangled among stories of bear attacks, increasingly small buffers between urban areas and wilderness, and hopes to return fragile ecosystems to their healthiest states, both proposals have been met with controversy on all fronts.

The paradox for 399 is that while her story has helped drive worldwide attention for grizzly conservation, every step she takes in front of a crowd is a huge risk to her life, and — as the face of a species — the reputation of all grizzlies.

LAYBOURN SAYS THAT day he saw 399 for the first time was the day his life changed. The encounter was so unusual, he knew he wanted to find her and her cubs again. He became so occupied by 399 that he quit his seasonal jobs building homes and guiding wildlife tours to become a filmmaker so he could spend more time looking for her. Eventually, he produced a short documentary about her story, about the fine line

she walks teetering between wilderness and human development. He filmed 399 threading a path through the forest with her cubs running ahead, and leading her cubs through a gauntlet of parked cars and people. One shot pans behind a wall of people standing along the road, watching her hunt down an elk.

“The celebrity was unavoidable because she’s so visible,” Laybourn says. “But I think it’s a conscious trade-off that she has made. That she can put up with hundreds of people watching her, making all sorts of noise, acting stupid. She still just goes on about her business. It’s not like she spends her time staring back at us. She’s foraging. She’s teaching her cubs different food sources. And just living her life.”

Others caught on to 399’s presence in the park around the same time as Laybourn. Tom Mangelsen, a wildlife photographer, first saw 399 and three of her cubs near Oxbow Bend, a well-known site in Grand Teton National Park to see wildlife. He still spends countless hours searching for 399 and taking photographs of her. One year, he counted the days in the field he spent looking for her: 150. Grizzly 399 is Mangelsen’s muse. “She’s beautiful in ways we think the classic grizzly bear might be described,” Mangelsen says. “Her personality is calm, generally speaking. She’s very smart, intelligent.”

It’s easy to project humanlike qualities onto 399. She’s a mother. Watching her lead her cubs, looking both ways as she crosses a road, is so easy to relate to. Humans anthropomorphize animals and assign them human qualities to relate to, and have empathy for, them. There might also be a deep, innate part of us that wants to believe we are still connected to wild places and creatures, despite the ways modern development buffers us from that world. If we can relate to animals, it makes it easier to believe that we can coexist alongside them. That’s part of 399’s allure, why so many people are so drawn to her.

“The visitors that are coming to see these bears, I mean, we’re all human. We want

to know the story,” says Justin Schwabedissen, Grand Teton National Park’s bear biologist. “We want to make those connections to these animals.” But 399’s relatability can be deceiving. It’s all too easy to forget that she is wild, unpredictable and has limits to her tolerance. “I think that a lot of times we do forget some of the biology behind these animals,” he adds.

IN JUNE 2007, a teacher, Dennis VanDenbos, was hiking at Jackson Lake Lodge when he encountered 399 and her three cubs. After rounding a corner on the trail, he surprised the family as they were consuming the carcass of an elk calf. VanDenbos was too close. Grizzly 399 reacted and bit VanDenbos in the back.

At that time, bear biologist Chris Servheen was the grizzly bear recovery coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Part of his job was deciding the fate of bears when they got into a conflict with a human. When a problematic bear is “removed,” wildlife officials can relocate the bear, place it in captivity or euthanize it. When the case of 399’s attack on VanDenbos came to Servheen, however, he decided to leave her and her cubs alone. It came down to this: He believed 399 was acting as a bear should act, hunting for food with her cubs in her natural environment. And VanDenbos, though he was injured, survived.

Servheen calls the mauling a “natural aggressive incident.” Famous or not, Servheen says he made no exception for 399, gave her no special treatment. “Natural aggression is defense of food, surprise encounter or protecting cubs,” he says. “Bears that are aggressive in one of those three types of incidents, we tend to give a lot more leeway to.”

Still, it was a close call. If 399 ever went further, the outcome would be a different one. “It’s remarkable that she’s lived as long as she has, considering the hazardous area that she lives in,” Servheen says, noting that biologists don’t want to see grizzlies spend as much time so close to humans as 399 does. She’s not the model example of

grizzly behavior — even though somehow, to many, she is just that.

TO A GRIZZLY bear, the concept of Grand Teton National Park doesn’t mean much. Schwabedissen says all grizzlies leave the park’s boundaries from time to time. Once bears cross the park’s boundary line, they enter the jurisdiction of a handful of federal, state and local agencies, as well as private and public lands, ranchers and hunters, tourists and second homeowners. Whenever 399 ventures beyond the park, law enforcement and wildlife officials are on alert. When she mauled VanDenbos in 2007, Grizzly 399 was still relatively unknown.

OF 399’S 18 CUBS, 10 HAVE DIED, ALL BUT TWO FROM HUMAN-RELATED CAUSES. THIS IS ONE REASON WHY THERE ARE EFFORTS TO DELIST GRIZZLY BEARS.

She may not have gotten special treatment then, but she does now. Last year, 33 wildlife brigade volunteers logged more than 12,000 hours in the park, working from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. seven days a week during peak season, to monitor wild animals like 399 and ensure encounters with humans are avoided.

“There’s been a lot of effort that’s gone into maintaining her and keeping her alive,” Servheen says. “I want you to know that. A lot of state management agencies, park management agencies have gone to great lengths to try to secure her life and make sure that she stays out of trouble.” That may be so that the species can stay out of trouble at a vulnerable time, too.

As grizzly populations become denser, young grizzlies, especially the two- and three-year-olds newly independent from their mothers, have to disperse farther away from the park to find the resources they need and establish a home range, Schwabedissen explains. Almost all of those younger

grizzlies are pushing south or southeast — toward town. On a dark November night in 2021, Grizzly 399 and her four cubs were caught on security cameras roaming the empty streets of downtown Jackson. Footage shows the five grizzly bears walking right past the police station, the county jail, the courthouse. “She was in neighborhoods where people don’t really think about bears,” Luther Propst, Teton County Commissioner, says. “It was hair-raising.”

Of 399’s 18 cubs, 10 have died, all but two from human-related causes. Five of her offspring were euthanized by wildlife agencies because the grizzlies were getting into human foods or other human conflicts. Two were struck by vehicles. One was shot and killed by a hunter outside the boundary of Grand Teton in self-defense. These instances, in part, are some of the reasons why there are current efforts to delist grizzly bears, as well as resistance to reintroducing them in northern Washington.

Most everyone hopes that 399 will live the rest of her life in peace and that she’ll have a natural death whenever that time comes. The reality is that the odds of that kind of peaceful ending to her story are slim. Adult grizzlies have a much higher likelihood of dying at the hands of a human. So these days, Laybourn stays away and doesn’t go looking for 399 anymore. “Her celebrity is too much,” he says. Instead, he channels his passion for grizzlies into his work at Jackson Hole Bear Solutions, which gives Jackson residents bear-proof trash cans, helping to keep bears and people safe from each other.

At the same time, he doesn’t fault people for wanting to have their moment with her. People want to connect with American nature and experience those imitable moments of awe. For decades now, 399 has given them that. She gave Laybourn the same gift on that dark morning in 2006. “When you drive into Teton Park and all of a sudden there’s a grizzly bear with her three cubs on the side of the road, you realize you’ve reached wild.”

The dinner table conversations in Martha Minow’s home have, for decades, revolved around the big issues of the times: civil rights, the women’s movement, the war in Vietnam. From an early age, Minow was exposed to a fearlessness around addressing big ideas, and absorbed a sense of obligation to engage in public life and effect positive social change.

A former dean of Harvard Law School, a 300th Anniversary University Professor and a leading authority on human rights law, Minow thinks a lot about what it means to honor the humanity of each individual, particularly those who are often marginalized. She studied the origins of ethnic conflict in Kosovo and, in 2001, worked with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to chart possible ways forward for post-conflict societies in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda.

Minow’s scholarship spans a broad range of topics, including human rights, legal ethics, disability rights, education law, local news and the role of law in promoting social change. In her most recent book “Saving the News,” she wrestles with alternatives for sustaining local news.

In an interview with Deseret, Minow shared her thoughts on more productive ways of resolving conflict, seeing the humanity in those we disagree with, and finding resolution amid tensions between state and religion.

WHEN I WAS quite young, probably in first grade, I distinctly remember noticing that the prayers that were said in school were not the ones that I heard at home. My family is Jewish, and I grew up very mindful of the history as the basis of religious identity. It was part of my upbringing to recognize that the human experience is universal. I’ve always felt that the oppression the Jews

WE NEED TO SHARE THE BELIEF THAT THERE IS SOMETHING GOOD ABOUT LEARNING FROM PEOPLE WHO ARE DIFFERENT AND CULTIVATING ENOUGH HUMILITY SO YOU DON’T THINK YOU’RE ALWAYS RIGHT.

have experienced gives us an obligation to stand up for people who are not Jewish but face similar kinds of challenges.

The focus in my work has been on people who are excluded or marginalized in society. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court

who fought in the Civil War, wrote that it was “absolute belief” that leads people to violent conflict. So many wars have been fought because people are so confident that they’re right.

I’ve been writing for some time about how problematic it is for disagreements between the state and religion to go to court. If you go to court, they don’t say, “Let’s work it out.” The courts answer “yes” or “no” questions in a winner-takes-all approach. But the questions of church and state are not “yes” or “no” questions — they are very complicated issues.

When it comes to resolving these disagreements, I advocate for finding points of convergence and negotiation. I have the utmost respect for the Utah Compromise, a concerted effort between The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and state leaders to find common ground around the issues of LGBTQ anti-discrimination and religious freedom. I’m not a Latter-day Saint, but I do understand that a part of Latter-day Saint theology respects the Constitution and understands that pluralism is an important part of being able to live together. We need to share the belief that there is something good about having the possibility of learning from people who are different from yourself and cultivating enough humility

so that you don’t think you’re always right.

At Harvard Law School we have a program on negotiation that teaches students to distinguish between their interests and their positions. Often, the conflict seems irresolvable, because people have positions that are too far apart. But when people reflect on what they really want, once they identify the interest underlying their position, they can often come up with a third answer that both parties are quite happy with.

I acknowledge there are some irresolvable conflicts. Yet, I do believe that a mindset that can lead to more productive solutions is one that recognizes the humanity of everyone involved. It tries to find the points of convergence and overlap to achieve common goals while coming from different positions.

In the United States legal system, we’re very focused on the individual and individual rights, but rights are actually a way to think about relationships. We don’t have rights apart from other people. It is about constructing the basis for respecting other people.

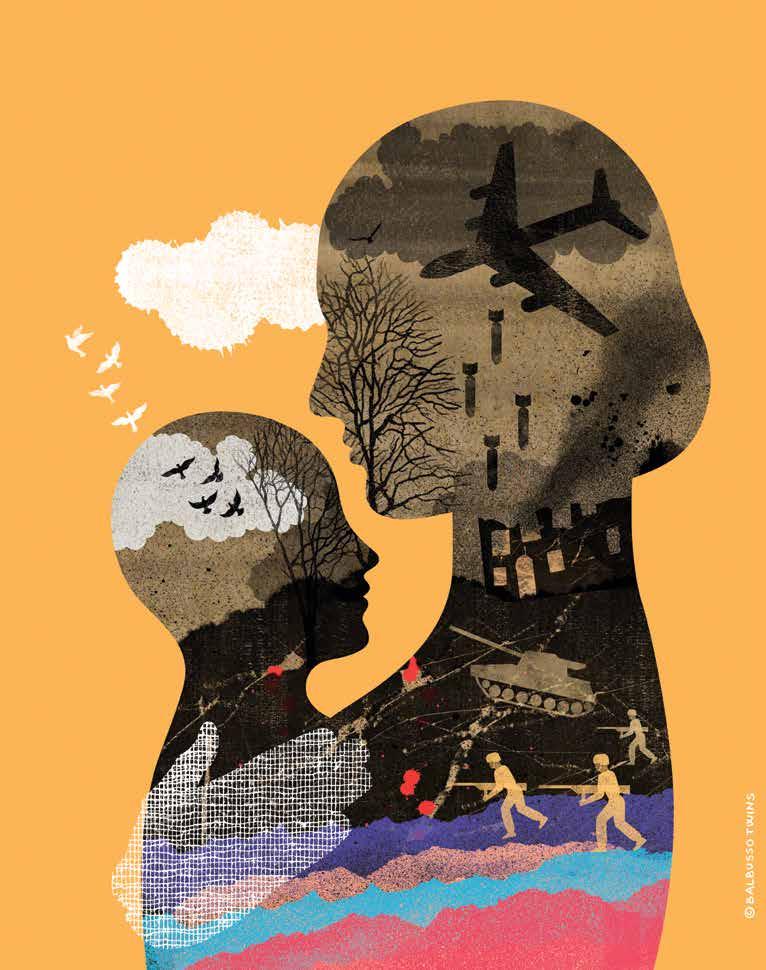

Some people have told me they don’t understand my work — why I focus on child abuse, war, genocide. And for me, it’s all very connected. The connection has to do with the dehumanizing of another that can lead to violence, discrimination, war and the refusal to find a way to coexist. Unfortunately, there can be a downward slide. I worry about our country right now, that there’s such demonizing of people.

I had a wonderful adviser in college, Gerald Linderman, who told me: “Don’t forget that the people you’re writing about are all human

beings.” That was very powerful to me.

I think that we can lower the temperature and hostility of conflicts when we separate the disagreement over issues from the dignity of the people holding views with which we disagree. Respecting people that we really disagree with means listening and being open to the possibility that we don’t understand. It also means finding areas of agreement we can build on. These points of connection can be pragmatic and practical, but they also can very much be renewed and strengthened by a recognition that the person on the other end of the disagreement is a human being who has dignity, who deserves respect, who — just like me — has struggles, and hopes, and dreams, and all the things that make human life precious.

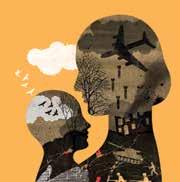

YEARS AFTER FORCED FAMILY SEPARATIONS, THE PIECES ARE PAINFULLY BEING PUT BACK TOGETHERBY GABY DEL VALLE

Anilú Chadwick thought she was delivering good news. After months of scouring government records and coordinating with various federal agencies, she had tracked down the father of one of the more than 5,600 migrant children separated from their parents in government custody while attempting to immigrate to the United States. But there was a problem. When Chadwick set up a phone call between the child — who was being held in a government shelter — and their father, the two couldn’t understand each other. They had been apart just a few months, but the child could no longer communicate with their father in their native language.

Without being able to confirm that this was the right child that they were bringing back to the family over the phone, Chadwick sent the father a picture of the child. “It felt like trying to update the kidnapped child poster to say, ‘OK, is this the child you’re looking for?’” says Chadwick, a managing attorney at the immigration advocacy nonprofit Kids In Need of Defense.

What should have been a moment of relief — a family reunited after a traumatic, protracted separation at the hands of a foreign government — was instead bittersweet. As efforts intensify to reunite families who have been separated since the Trump administration’s zero tolerance

immigration policy was enacted, instances of migrant children who have forgotten their native languages or even their parents’ faces are becoming more common.

On May 7, 2018, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions declared that anyone caught crossing the border without authorization would be arrested for illegal entry. A statute criminalizing illegal entry had been on the books since 1924, but prosecutions were rare, until the Bush era, when they surged after 9/11. Families were largely excluded; those targeted were primarily

“IT FELT LIKE TRYING TO UPDATE THE KIDNAPPED CHILD POSTER TO SAY, ‘OK, IS THIS THE CHILD YOU’RE LOOKING FOR?’”

single adults, not parents traveling with children. For parents hoping to claim asylum with their families, the zero tolerance policy would mean being separated from the children they were trying to protect. A different picture was painted during the policy’s announcement. “If you don’t want your child to be separated,” Sessions said in a press conference, “then don’t bring them

across the border illegally.” After six weeks of sustained backlash, representing everyone from former first lady Laura Bush to the chair of the National Republican Congressional Committee, former President Donald Trump signed an executive order prohibiting immigration officers from separating families.

But, largely unknown to the public at the time, separations had begun long before Sessions’ announcement and continued after Trump rescinded the protocol. Chadwick started working at Kids in Need of Defense, or KIND, in September 2018, three months after Trump reneged on the zero tolerance directive. By that point, advocates for migrant children had been sounding the alarm about the practice for well over a year. In the spring of 2017, legal service providers started noticing an uptick in referrals to shelters operated by the Office of Refugee Resettlement — and the children they spoke to said they weren’t unaccompanied minors at all. They had come to the United States with their parents, only to be taken from them after crossing the border.

At least 998 of the estimated 5,500 children taken from their parents at the border as of last February are waiting to be reunified with their families, according to the Department of Homeland Security. And uncertainty continues to linger as this year’s presidential election approaches.

Immigration is considered by candidates and voters as one of the country’s most pressing issues. Trump has promised to revive extreme immigration crackdowns if he is reelected. This time around, however, there will be more oversight and constraints on the president’s ability to separate families at the border. A recent settlement in federal court prohibits the federal government from separating migrant families again for eight years.

THE LANGUAGE OF border enforcement makes it difficult to understand how and why the separations occurred. Crossing the border illegally is indeed a federal crime — one that prosecutors decide whether to enforce. But when Border Patrol agents catch someone crossing between ports of entry, they don’t arrest them: They “apprehend” the border crossers, detain them in Customs and Border Protection custody until they can be transferred to facilities operated by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and then begin deportation proceedings. The entire process, which was created bit by bit over the 20th century, is civil, not criminal, and it applies to children just as much as it does to adults.

The parents arrested in El Paso were apprehended by Border Patrol agents then referred to federal prosecutors to be charged with illegal entry then sent back to DHS custody and detained by ICE. Some were deported. Their children, meanwhile, ended up in Office of Refugee Resettlement shelters all over the country. And little effort as made to record which parents corresponded to which children, making reunifications incredibly difficult.

“Organizations that were working directly with kids in ORR custody were identifying many, many children who were deeply traumatized as they appeared in ORR custody and had been separated from their parents with virtually no record-keeping about the basis of the separation or where the parent could be located,” says Kelly Kribs, the Chicago co-director of the technical assistance program at the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights.

The broader public only became aware that separations were occurring in November 2017, after the Houston Chronicle reported that public defenders in El Paso were being assigned to migrants who claimed to have had their children taken from them after crossing the border. The Trump administration denied that it had a family separation policy in place. But in January, the ACLU filed a lawsuit on behalf of Ms. L., a Congolese woman who had her daughter taken from her in San Diego in November 2017 — one of the thousands of African migrants who arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border that year, amid a significant uptick in asylum claims from people outside Latin America. Unlike the families whose separations were triggered by illegal entry arrests, Ms. L. asked for asylum at a port of

“IF YOU DON’T WANT YOUR CHILD TO BE SEPARATED, THEN DON’T BRING THEM ACROSS THE BORDER ILLEGALLY.”

entry, meaning she didn’t cross the border without authorization. Her child was taken anyway, and they remained separated until the lawsuit was filed. But this was just one reunification, and the government had yet to admit that the separations were systematic and widespread.

In March of that year, the ACLU filed a motion for class certification, expanding the lawsuit to all “adult parents nationwide” in federal immigration custody whose children were being held in ORR shelters, “absent a demonstration ... that the parent is unfit or presents a danger to the child.”

By the summer of 2018, all eyes were on the border. A poll by Quinnipiac University found that 66 percent of voters opposed family separation, though 55 percent of Republican voters supported it. Some Republican lawmakers, however, broke with

their party’s leadership and criticized the policy. Republican senators including John Kennedy of Louisiana and Susan Collins of Maine spoke out against the separations. Collins called the practice “traumatizing to the children who are innocent victims” and “contrary to our values in this country.” Mitt Romney, at the time the Republican Senate candidate for Utah, urged the Trump administration to stop the “disturbing” separations, which he called a “dark chapter” in American history.

On June 26, a week after Trump ended the policy, a federal judge gave DHS a 30-day deadline to reunite the families separated under the policy, excluding parents who declined to have their children returned to them and those who were deemed to be unfit or present a danger to the child. Children ages five or younger were to be reunited in two weeks.

It quickly became evident that it would be impossible to reunite families within that time frame: At least 400 parents had already been deported and had reportedly been told that they’d only get their children back after signing repatriation documents. Gutting images emerged during these few months. Children were photographed in crowded, dirty Border Patrol holding cells; their cries were recorded by whistleblowers, as were the taunts lobbed at them by immigration officers. A video surfaced of a woman crying after being reunited with her toddlers — not tears of joy, but of confusion upon recognizing that her baby no longer recognized her.

A WEEK AFTER taking office in February 2021, President Joe Biden announced the creation of an interagency family reunification task force. Until that point, the reunification effort was almost entirely spearheaded by a coalition of immigrant advocacy organizations led by Justice in Motion, a nonprofit organization based in New York. With the government’s help, the organizations hoped the arduous process of identifying, tracking down and reuniting families would become a little less difficult.

By June of that year, the task force

reported that it had identified at least 3,900 children who were separated under the zero tolerance policy, more than 2,100 of whom had yet to be returned to their parents. “When we received the list and the government information,” Chadwick says, “it was a lot of the same information that we had received in 2018 that led to dead ends.” To find parents, KIND and its partners had to rely on nonprofits in the parents’ countries of origin. One of the biggest hurdles, Chadwick adds, was convincing parents to trust the same government that had taken their children.

“In some cases, it took up to 11 months of continuous conversations with individuals who were part of the family both in the countries of origin and in the U.S. to make sure that this was a true program, that this wasn’t another lie, that they actually may see their children once again,” Chadwick says.

To gain trust, KIND worked with people on the ground in Guatemala who spoke the same Indigenous languages as many of the families who had been separated. Chadwick recalled working with a reunification specialist who is fluent in Q’anjob’al, a Mayan language spoken by about 100,000 people. “It was the first time the father had ever been talked to about separation — explained what had happened — in a language he understands,” Chadwick says. “Having that parent’s trust and having word about the program spread through the community, in that community’s voice, led to more than 20 individuals from that community registering and qualifying to be reunited with their children.”

Throughout the reunification process, the Biden administration and the ACLU have been negotiating a settlement for the families separated under zero tolerance. In late 2021, after The Wall Street Journal reported that the administration was considering paying $450,000 to each family affected by the policy, Biden — who had previously said affected families deserved some “sort of compensation, no matter what” — dismissed the report as “garbage.” Shortly after, the administration withdrew

from financial settlement talks, noting that settlements could be a political liability. By December of that year, negotiations had stalled. The administration and the ACLU finally agreed on a settlement in October. Under the settlement agreement, the families who were split up will be allowed to return to the United States and will have their asylum cases reopened. Unlike other asylum-seekers, they won’t be subjected to a one-year application deadline. The parents will receive expedited, renewable three-year work permits, and will also get medical and mental health assistance from the federal government. The settlement also expands the size of the class action by at least 500 people, bringing the total number of affected children to more than 4,400.

“I think both we and the Biden admin-

ONE OF THE BIGGEST HURDLES WAS CONVINCING PARENTS TO TRUST THE SAME GOVERNMENT THAT HAD TAKEN THEIR CHILDREN.

istration would have liked to have gotten this done sooner,” says Lee Gelernt, the lead ACLU attorney on the case. “But now we’re not going to look backward. We think short of Congress issuing green cards to these families, this settlement is a significant step forward.” The settlement also prohibits federal immigration authorities from using illegal entry as a mechanism to separate parents from their children, though it does allow separations under limited circumstances, which Gelernt says the ACLU will track.

Some advocates worry these measures don’t go far enough, both in terms of recourse for families and with regards to preventing future separations. “These families deserve monetary damages for the lasting and significant harm that our government inflicted upon them,” says Jane Liu, the

Chicago-based policy and litigation director at the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights. Liu adds that separations have continued under Biden, occasionally because Border Patrol agents deem that the parent is a danger to the child, but noted that officers have a lot of discretion while making that determination. “We continue to be appointed to kids that have been separated from family members — parents — under the Biden administration,” she says.

For those who have spent the past six years mitigating the fallout of the zero tolerance policy, the settlement is a crucial step forward, but it is not the end. Dr. Nicholas Cuneo, the co-founder and medical director of HEAL Refugee Health and Asylum Collaborative, says the separations will undoubtedly have long-term — potentially lifelong — effects on children’s mental and physical health. Cuneo points to the large body of medical work indicating that children who go through “adverse childhood experiences” often develop chronic medical conditions. “Having a greater number of adverse childhood experiences was shown to lead to decreased lifespan,” he says.

Cuneo has worked with children of all ages who have been traumatized by separations, and he says that the psychological toll has been significant. “For young children, at the beginning — on the reunification side — they may not know or recognize their parent, and may be very quiet and not emotive in a way that can be powerfully disturbing to the parent, who is wanting to have this emotional reunion,” he says. Older children often feel guilty and ashamed of what happened to them, Cuneo says, “and they’ll internalize that trauma — they’ll feel culpable.” Self-blame is a common symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder, and some parents, too, blame themselves for what the government did to them.

“They often will question whether they should have made the journey to begin with, even if they were fleeing something that doesn’t leave them with much choice,” he says. “Often, they’ll say, ‘This was much worse than anything I could have imagined.’”

NO DEMOCRACY IN RECENT HISTORY IS AS POLARIZED AS THE UNITED STATES IS RIGHT NOW. HOW DID WE GET HERE? AND CAN WE FIX IT?

HERE ARE A DOZEN IDEAS, ORGANIZATIONS AND PEOPLE FIGHTING POLARIZATION

ILLUSTRATION BY JON KRAUSE PORTRAITS BY KYLE HILTON BY SPENCER COX

BY SPENCER COX

n July 2023, I was honored to be elected by my fellow governors to serve as the chair of the National Governors Association and immediately launched an effort we titled “Disagree Better: Healthy Conflict for Better Policy.”

That title was quite deliberate.

Rather than suggest we need more civility or bipartisanship in our politics — both good things — I wanted to convey that what we need even more is to disagree differently and that healthy conflict is an important prerequisite for good policy. Toxic conflict is bad, but the lack of conflict is also bad.

Before I share more about our work as governors, allow me to explain why I’m deeply concerned about our country. In early 2022, a group of fellow governors and I attended a reception at the Swiss Embassy in Washington, D.C. Ambassador Jacques Pitteloud began his remarks as one would

expect, touting the important economic ties between Switzerland and the U.S. He then spoke about how his Cold War childhood shaped his admiration of the United States and described being in Berlin in 1989 when the Wall crumbled. The ambassador’s remarks then took a turn. He said he worried that America had become deeply divided and that extreme voices on both sides were now dictating the political agenda. “There is a fear that this is not the America that can be trusted to lead and transform the world as it did in my youth,” he said.

I’ve since heard this sobering sentiment from many current and former diplomats and allies: that U.S. polarization and political violence are part of Vladimir Putin’s strategy; that our endless bickering emboldens Russia and China to criticize democracy and promote autocracy to weaker nations; that our allies are concerned about our lack of predictability; and that rising levels of political violence in the U.S. make us less credible in criticizing the same abroad.

Robert Gates, former secretary of defense to both Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, recently told me he believes polarization is currently the greatest threat to the United States. That’s a startling assessment from someone who knows.

Americans now use the word “divided” more than any other trait to describe our country, and between 2018-2022, Americans’ desire to listen to the other side dropped sharply, from 60 percent to 49 percent, and their animosity toward members of the other party is increasing rapidly. More than 7 in 10 Democrats and Republicans perceive the other side as brainwashed, hateful and arrogant. Polling shows that 70 percent of Americans believe America is in crisis and at risk of failing, and 40 percent of Americans report they’ve lost faith in U.S. democracy.

Those perceptions are now translating into actual violence. Between 2016-2021, political violence toward members of

Congress increased tenfold (1,000 percent) and nearly doubled for the judiciary. The same is true for local officials, who report shocking levels of harassment and threats.

All of this creates a chilling effect, both on public service and on speech itself.

So where will it all end? Without a change, I fear it ends in more violence at home, continued policy gridlock and extraordinary vulnerability abroad.

LEST I’VE PAINTED too bleak a picture, let me offer important reasons for hope.

First, there’s a huge market for something different from our politics. It turns out there is an “exhausted majority” of Americans — about two-thirds of us — who are fed up with divisive rhetoric and feel their voices are overlooked as louder and harsher voices dominate the political discussion. Most of the exhausted majority are not moderates, but they believe it’s possible to find common ground.

There’s also an exhausted majority of politicians who are hungry for a change. The response to Disagree Better among my fellow governors and other elected officials has been not only supportive but enthusiastic. They don’t want to view their opponents as their enemies and they don’t like catering to the fringe of their party who demand extreme rhetoric and reckless behavior. Like me, they entered public service to solve problems and are frustrated that extreme polarization often makes that impossible.

It’s also helpful for us to recognize we may not be as far apart as we assume based on what cable news tells us about the other side. It turns out there is a “perception gap” — both Republicans and Democrats believe the other side is about 30 percent more extreme than they actually are.

Improving the way we talk about politics and treat people is absolutely critical, but we also need to change how we judge candidates for public office. Whether a candidate treats opponents with dignity or contempt

shouldn’t be secondary to their positions on health care, immigration or energy policy; it should be alongside or even ahead of those issues. This works best when each side monitors and tends its own candidates and behavior. As voters, we dictate the political marketplace and we should be willing to reject candidates with whom we might agree ideologically when they are gratuitously divisive.

In that same spirit of changing the marketplace, if you’re on social media, mute the divisive voices from both sides and amplify the constructive voices. And please consider turning off cable news entirely. My wife Abby and I are 11 years sober from cable news, a decision that improved our lives immeasurably.

And finally, we should work on building up the institutions within our orbit. When we belong to a church, a Rotary or Kiwanis Club, a book club or some other community organization that offers us friendships, a role to play, and a chance to serve others, we’re less likely to make politics our religion.

To be clear, we’re not asking people to leave behind their sincerely-held beliefs. I’m a conservative Republican and I’ll continue to criticize ideas I think are wrong. I’m confident Democrats will continue to oppose many of my positions. The key is keeping the conflict respectful and productive. Sometimes healthy conflict will produce a compromise, but sometimes it won’t and that’s OK. It’s still the right approach.

Evil people and malevolent regimes see America’s divisiveness as an opportunity to exploit. May we prove them wrong and show that the best feature of American democracy is a constitutional system that helps us not merely tolerate people with differing views, but to engage with them, debate them respectfully, refine our ideas, win with magnanimity, lose with grace and make our country stronger.

SPENCER COX IS THE GOVERNOR OF UTAH AND THE CHAIRMAN OF THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION.

THERE IS AN “EXHAUSTED MAJORITY” OF AMERICANS WHO ARE FED UP WITH DIVISIVE RHETORIC AND FEEL THEIR VOICES ARE OVERLOOKED AS LOUDER AND HARSHER VOICES DOMINATE THE POLITICAL DISCUSSION.

WHEN JOHN GABLE joined Netscape Navigator, a now defunct internet browser, in 1997, his view of the internet was still optimistic. Gable imagined a world where the flush of new information would eliminate stereotypes, improve decision-making and bolster connection. He’s since changed his mind about what the internet has become.

It’s true that information is more accessible than three decades ago, but this has risen in tandem with polarization and media bias. That’s why Gable co-founded AllSides in 2012, which offers tools to promote balanced news and reduce polarization.

These tools include audits for news organizations to determine their own biases and the AllSides website, which syndicates news stories and labels their political leanings. Gable hopes the internet can once again be a source of knowledge rather than of misinformation. “We’re farther along the path to recovery than we were,” he says. “We have a chance to start making things better.”

—NATALIA GALICZATO REDUCE POLITICAL POLARIZATION AND SAVE AMERICA FROM ITSELFBY RACHEL KLEINFELD