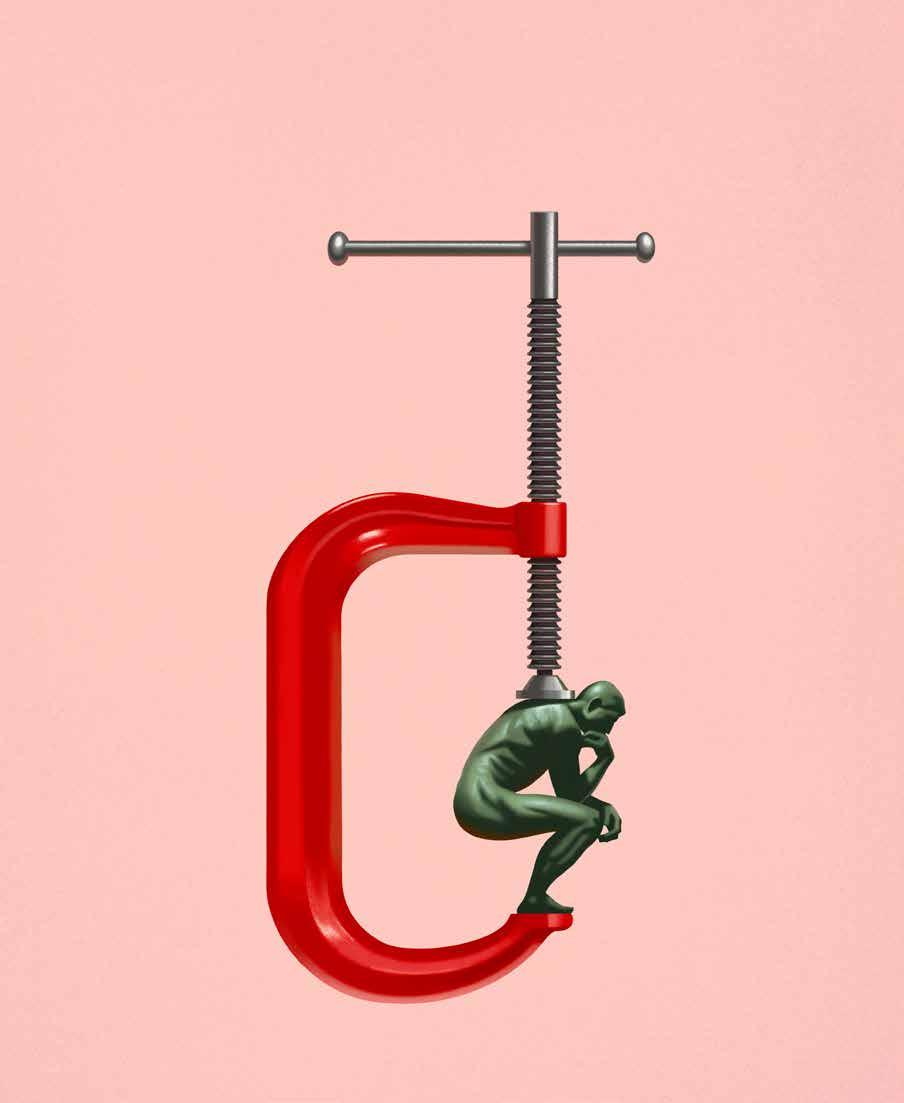

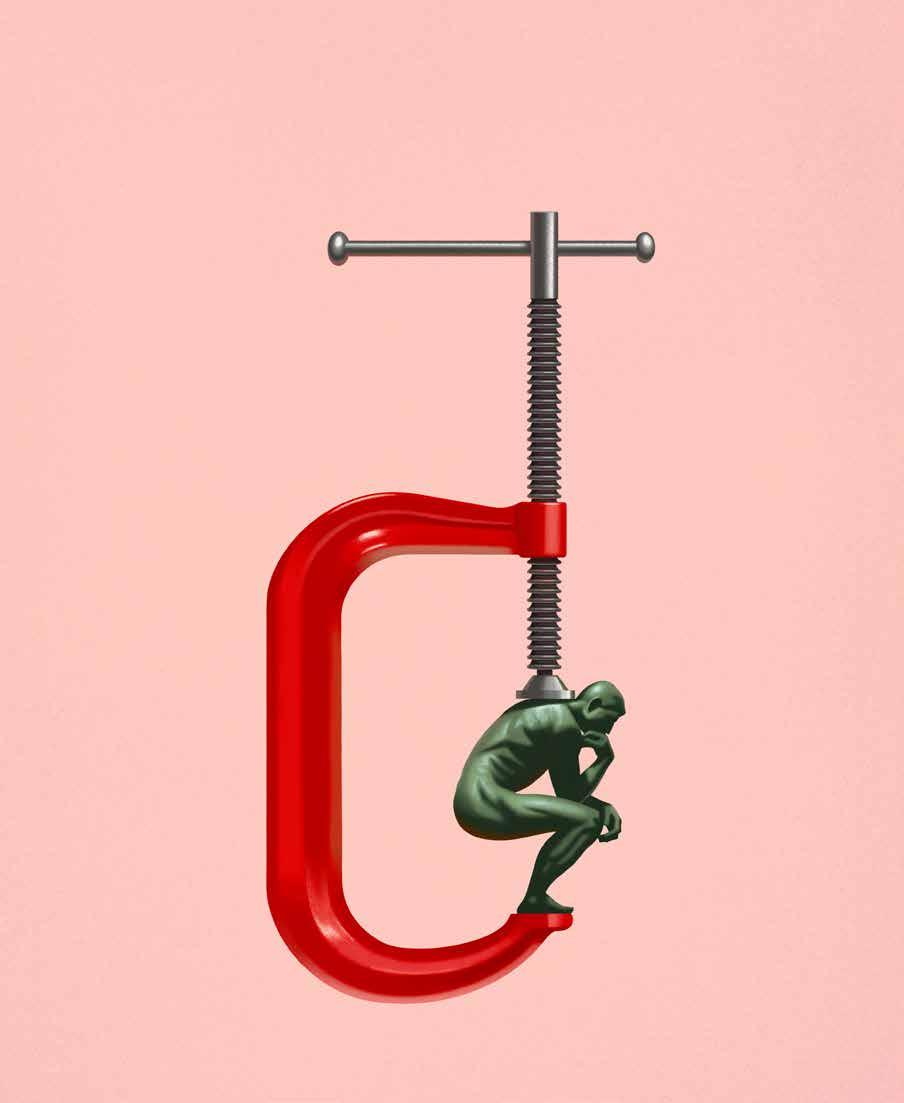

THE BIG SQUEEZE

HIGHER ED IS UNDER PRESSURE FROM ALL SIDES. CAN IT BE SAVED?

BY PATRICK J. DENEEN

HIGHER ED IS UNDER PRESSURE FROM ALL SIDES. CAN IT BE SAVED?

BY PATRICK J. DENEEN

Religion in America is constantly changing – and Pew Research Center’s Religious Landscape Study tracks those changes across nearly 20 years of data.

From the rise of the nones to shifting beliefs and practices, it’s the clearest view yet of the role of religion in our country.

See what’s changing at pewresearch.org/rls

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE PROMISE OF COLLEGE?

by clark g . gilbert , ted mitchell , derrick anderson , beth akers and david a . hoag

IS TRUMP’S PUSH TO PUNISH THE IVY LEAGUE GOING TOO FAR? by eric

schulzke

CELEBRATING THE NOSTALGIC SPIRIT OF COUNTY FAIRS. by

lauren steele

bauer

NOVEMBER 17, 2025

Utah Business Forward is where Utah’s top business achievers share strategies that help fuel the No. 1 economy in the nation.

The third-annual Utah Business Forward conference will assemble dozens of the best business minds in Utah who are eager to share their knowledge to keep our economy strong for years to come.

At this one-day conference you will have access to leaders in various industries, from product development and manufacturing to finance and entrepreneurship.

You’ll learn about the innovation, resilience, strategy, relationships it takes to take your business and career to the next level.

GET TICKETS

“AI is not going to style your hair or fix the pipes under your sink.”

Nunes is president of California Lutheran University and a senior fellow at the Center for Religion, Culture and Democracy. An ordained Lutheran minister, he is past president and CEO of Lutheran World Relief and held an endowed professorship at Valparaiso University. His commentary on how higher education can help heal what divides us is on page 11.

Elder Gilbert is a General Authority Seventy and commissioner of the Church Educational System for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He has been president of BYU-Pathway Worldwide and BYU-Idaho, president and CEO of Deseret News and is a former entrepreneurial management professor at Harvard. His essay on what faith-based schools provide young adults seeking meaning is on page 31.

Gorewitz is a writer and lifelong New Yorker whose personal essays have been published in HuffPost, Business Insider, USA Today, New York Daily News and Living Better After Fifty. Her first book, “You, Me and the Dog: An Unconditional Love Story,” will be published by Heliotrope Books in August 2026. Her story about the unknowns of aging is on page 16.

A senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, Akers is also a contributor to the Sutherland Institute’s “Defending Ideas” podcast. She has been published in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg Opinion and is the author of “Making College Pay: An Economist Explains How to Make a Smart Bet on Higher Education.” Her essay on that topic is on page 35.

Deneen is a professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame who has also taught at Georgetown and Princeton universities. He is the author of several books, including “Regime Change: Toward a Postliberal Future,” “Why Liberalism Failed,” “Democratic Faith” and a number of edited volumes. His essay on the myth of academic freedom is on page 68.

A staff photographer at the Deseret News, Crowley’s work has also been published in the Chicago Tribune and The Virginian-Pilot. She graduated from the University of Michigan in 2024 and was recognized this year as the Emerging Vision Photojournalist of the Year by the National Press Photographer’s Association. Her photo essay is on page 60.

Earlier this year, my friend expressed concern about his brother who, by all measures, would make a strong candidate for higher education. He had good grades in high school and high ambitions. I asked if I could talk with this young man, and my friend arranged for a meeting. I did my level best to outline the statistics for why a college degree continues to be — despite all the challenges currently facing higher education — a wise financial investment and a prudent life choice for long-term personal development.

When our meeting concluded, I sensed this young man wasn’t quite persuaded. It turns out he’s not alone. Fewer young men are choosing college.

Earlier this year, The New York Times ran an article with the headline, “It’s Not Just a Feeling: Data Shows Boys and Young Men Are Falling Behind.” The reporting featured a chart with federal data noting the sizable gap between male high school graduates enrolled in college (57 percent) and female high school graduates enrolled in college (66 percent). Pew Research Center further estimated that today there are about one million fewer males enrolling in college than 15 years ago.

Certainly, there’s no single cause for this phenomenon. But there is anecdotal evidence that a combination of rising costs and the cultural climate on many campuses are causing at least some to jump into the workforce sooner rather than pursue a degree. A crisis in meaning, mental health and loneliness are other contributing factors impacting all students.

This year’s special issue of higher education explores some of these factors.

Elder Clark G. Gilbert, the commissioner for the Church Educational System for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,

discusses the ways faith-based institutions of higher learning are uniquely situated to address these concerns.

Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education and the former undersecretary of Education, together with Derrick Anderson make the case that while higher education has always been under pressure, now is the time to embrace innovation and reform while emphasizing the good our campuses contribute. Beth Akers of the American Enterprise Institute tackles the challenge of rising costs. “What comes next,” Akers concludes, “must be smarter, clearer and more transparent.”

Patrick Deneen, a distinguished scholar at Notre Dame, walks through the history of academic freedom and its meaning today for religious institutions. Eric Schulzke provides in-depth reporting about the federal government’s ongoing battle against the Ivy League.

Sprinkled throughout the issue are must-read articles such as Ethan Bauer’s account of a scrappy band of footballers in England with a front office defying the odds by leaning on faith as well. An ideas essay from Zachary Davis explores why the rising generation is rediscovering faith.

In the coming years, higher education will face a so-called demographic cliff due to the declining number of college-aged students nationwide. This means higher education will need to become more relevant and essential to those potentially interested in college training. Some of this will involve making the dollars and cents more attractive, but the bigger gains will come as higher education addresses the larger looming challenges facing young men and young women, including the crises of meaning and loneliness. Faith-based institutions add something special to this conversation, which secular campuses — especially those under increased scrutiny today — would do well to study.

EXECUTIVE EDITOR HAL BOYD

EDITOR

JESSE HYDE

CREATIVE DIRECTOR ERIC GILLETT

MANAGING EDITOR MATTHEW BROWN

DEPUTY EDITOR CHAD NIELSEN

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

JAMES R. GARDNER, LAUREN STEELE

EDITOR-AT-LARGE DOUG WILKS

STAFF WRITERS

ETHAN BAUER, VALERIE BRAYLOVSKIY, NATALIA GALICZA

WRITER-AT-LARGE

MICHAEL J. MOONEY

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

LOIS M. COLLINS, JENNIFER GRAHAM, KEVIN LIND, MARIYA MANZHOS, ERIC SCHULZKE

ART DIRECTORS IAN SULLIVAN, BRENNA VATERLAUS

COPY EDITORS

SARAH HARRIS, VALERIE JONES, CHRIS MILLER, CAMILLE SMITH

DESERET MAGAZINE (ISSN 2537-3693) COPYRIGHT © 2025 BY DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. IS PUBLISHED MONTHLY EXCEPT BI-MONTHLY IN JULY/AUGUST AND JANUARY/FEBRUARY BY THE DESERET NEWS, 55 N 300 W, SUITE 400, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH. TO SUBSCRIBE VISIT PAGES.DESERET.COM/SUBSCRIBE. PERIODICALS POSTAGE IS PAID AT SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH

POSTMASTER: PLEASE SEND ADDRESS CHANGES TO PO BOX 2220, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH 84101.

PUBLISHER BURKE OLSEN

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER ERIC TEEL

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT SALES TRENT EYRE

VICE PRESIDENT MARKETING EMILY HELLEWELL

VICE PRESIDENT SALES SALLY STEED

PRODUCTION MANAGER RHECE NICHOLAS

DIRECTOR OF CIRCULATION SYLVIA HANSEN

THE DESERET NEWS’ PRINCIPAL OFFICE IS 55 N. 300 WEST, STE 400, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH. COPYRIGHT 2024, DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA.

PROPOSED AS A STATE IN 1849, DESERET SPANNED FROM THE SIERRAS IN CALIFORNIA TO THE ROCKIES IN COLORADO, AND FROM THE BORDER OF MEXICO NORTH TO OREGON, IDAHO AND WYOMING. INFORMED BY OUR HERITAGE AND VALUES, DESERET MAGAZINE COVERS THE PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF THAT TERRITORY AND ITS INTERSECTION WITH THE BROADER WORLD.

Our JUNE cover story by Cambridge University emeritus history professor Gary Gerstle (“The End of Free Market Consensus”) explained why free markets and global capitalism reigned supreme for four decades. But what will replace the old order is up for grabs. An adaptation from the author’s book “The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order,” which Gerstle drew upon in May at Cambridge for a conference titled Beyond Neoliberalism, drew both praise and criticism from readers who found it informative on the evolution of free trade but lacking in revealing neoliberalism’s faults and what led to its decline. “The author promotes the fiction of a global free market,” wrote an online reader named Vermonter. “Having lived abroad for nearly a decade, I can tell you that the global free market is a myth. And, America’s so-called allies and friends have used the myth to enrich themselves at America’s expense.” Contributing writer Eric Schulzke told the story behind the demise of diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives in academia and the workplace across the country (“The Rise and (Sudden) Fall of DEI ”). Schulzke’s exploration into the reasons for the enthusiastic embrace then collapse of DEI won plaudits from leaders and influencers in higher education. John Tomasi, president of the Heterodox Academy, a nonpartisan organization that advocates for open inquiry on university campuses, called it the best piece he has read on the issue. “It just had so much nuance and depth,” Tomasi said. “I’ve shown it to several of my friends, (and told them) ‘You gotta read this one.’” Freeman A. Hrabowski III, president emeritus of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and who was quoted in Schulzke’s story, wrote that he has had “interesting conversations on a number of points” with those with whom he shared the article. “Thank you for caring about this issue, and most important, giving us a great deal to think about as we continue to grapple with these challenges.” Writer Mark Dee reported on the work of Fowler-O’Sullivan Foundation, which picks up where government searchers have given up on hikers who never return home from an ill-fated adventure (“When Hikers Go Missing”). “I’ve heard from so many people who read the article and were moved by it. You brought depth and humanity to a topic that’s close to my heart,” wrote foundation executive director Cathy Tarr. “I’m so grateful for the visibility it’s brought to this cause.”

CORRECTION: A story in the July/August issue under the headline “Betting on Disaster” stated that Jody McDonald and his wife began renovations to their cabin four years ago and that the insurance premiums they paid were monthly. The McDonalds began renovations on their cabin six years ago and the insurance premiums were yearly.

“I’ve heard from so many people who read the article and were moved by it.”

CAN FAITH-BASED COLLEGES HEAL WHAT DIVIDES US?

BY

JOHN NUNES

The Center for the Humanities at a leading university offers this simple and compelling definition of its discipline: “The humanities are the stories, the ideas, and the words that help us understand our lives and our world. They introduce us to people we have never met, places we have never visited, and ideas that may never have crossed our minds.”

And why should we care about these people, their stories and their ideas? Because when faith and reason dance, their coming together sparks the curiosity of love.

After more than 40 years of teaching theology at Valparaiso University, a Lutheran institution, a retiring colleague reflected on his decades of tenure: What had changed? What had remained the same? His response: “When I started, my students had names like Kristen, John, Mark and Mary, and I used to teach them about what Martin Luther believed about Jesus; then if there was any time remaining at the end of the semester, we’d talk about Muhammad and Krishna. At the end of my career, however, my students were named Jesus (pronounced as a Spanish name), Muhammad, Krishna and Shaquita. Although they now don’t too much care about Martin Luther, they do still seem to love learning about the world-changing justice and mercy of Jesus.”

The transition he noted was from a student population with ethnic descendants once primarily northern European to those who are now global; from monocultural particularity to inter-everything: intercultural, interracial, interfaith. Two rising variables — transportation and technology — have intensified a dilemma noted by social psychologists: We are more interconnected than ever and,

paradoxically, less connected historically, ethnically, linguistically, politically or tribally.

Some see this pluralism as divisive, diversity as disintegrative, and inclusivity as corrosive to the Christian faith. This emeritus professor, on the other hand, credits his faith as a pivotal influence in shaping his mind to embrace a new demographic reality.

Our ideas about God hold both intended and unintended consequences for our pedagogies and our treatment of the students and colleagues who come to us as persons. We know them not as census data, nor boxable categories, nor stereotyped forms, but as humans, possessors of divine dignity, intrinsic value, infinite purpose. This understanding animates us anew to study the humanities as the human ties that humanize us. Theoretical concepts conceal and carry ethical implications precisely because of the eternal Word becoming fully human (John 1:14), grace taking on a human face, faith and reason embracing each other.

Faith seeks the ancient Aristotelian ideal of virtue (aretē or excellence). The Greek verb for fixing one’s focus is λογίζεσθε (logizesthe). We hear in it an actual English verb — to logicalize — meaning to prioritize this use of reason in pursuit of truth.

It’s the meaning of Northwestern University’s Latin motto: “Quaecumque Sunt Vera” from Philippians 4:8. Eugene Peterson’s creative translation of this verse puts it this way: “Summing it all up, friends, I’d say you’ll do best by filling your minds and meditating on things true, noble, reputable, authentic, compelling, gracious — the best, not the worst; the beautiful, not the ugly; things to praise, not things to curse.”

Flowing from this humanizing purpose, the humanities spark love’s curiosity. At mealtimes when I was growing up, my family ordinarily came together to eat. My late father, Neville Nunes, a man of deep faith — considered by me and by many to be an emancipatory educator — would, in turn, direct me and my siblings at the dinner table to share, “What good questions did you ask in school today?” The humanities teach us to respectfully question narratives, interrogate truths, challenge assumptions and honor alternate narratives. This is a core charism of faith-based universities.

A charism is the Spirit’s enlivening gift, landing on individuals within institutions. Leaning into our unique identities, Christian colleges and universities can become prophetically differentiated within the culture, daring to care in ways that elevate their institution’s trajectory and in ways, we pray, that ameliorate the seemingly rising incivility of humanity.

In Plato’s “Republic,” we are given insight into the root of the word “theology”: It centers on logos, the word of the poet breaking into the cultural caterwaul with shalom, salaam, interrupting violent silences with subterranean love, angling iambically into tyrannies of rigidity with rhythmic pity, promising the mercy of the deity.

For the sake of our students, may it be so.

JOHN NUNES IS THE PRESIDENT OF CALIFORNIA LUTHERAN UNIVERSITY AND A SENIOR FELLOW AT THE CENTER FOR RELIGION, CULTURE AND DEMOCRACY.

ONCE, “HYPERACTIVE” KIDS were dismissed as problem children. The advent of attention-deficit hyperactivity/disorder, or ADHD, offered an alternative explanation for behavioral issues and symptoms like difficulty focusing and sitting still, racing thoughts and overlapping internal dialogue. It also offered a solution in the form of a pill. Decades later, ADHD is a burgeoning neurological diagnosis among children and adults alike, often celebrated as a more dynamic way of interfacing with the world. But in fact, we’re less sure now about what it is, how it works, what causes it and how to diagnose it. Here’s the breakdown.

—NATALIA GALICZA

1775

In his book, “The Philosophical Doctor,” German physician Melchior Adam Weikard cited inattentiveness and distractibility as symptoms of mental disorder, blaming “fibers” weakened by the patient’s upbringing. He suggested treatments like cold mineral baths, gymnastic exercise and

being left alone in a dark room. In 1798, Scottish physician Sir Alexander Crichton described a similar condition arising from an “unnatural sensibility of the nerves,” which patients called “the fidgets.” Curiously, each later became a personal physician to a Russian czar.

6 SYMPTOMS X

6 MONTHS

Children under 16 can be diagnosed with ADHD if they exhibit six related symptoms — like squirming, interrupting, getting distracted or forgetting homework — for six months or more. Five symptoms is enough for adults, per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the American Psychiatric Association’s encyclopedic reference used by providers, insurers, pharmaceutical companies and the courts. The DSM first covered “hyperkinetic reaction of childhood” in 1968; “Attention-Deficit Disorder” in 1980; ADHD in 1987; and adult ADHD in 1994.

Prescriptions for stimulants used to treat ADHD, like Adderall and Ritalin, rose 58 percent nationwide from 2012 to 2022. Fueled by amphetamine and methylphenidate, respectively, these meds have been shown to improve classroom behavior — for a time — but don’t boost academic performance. These drugs are also highly addictive, admittedly abused by up to a quarter of middle and high school students, according to an expansive study released in 2023.

By age 17, 23 percent of boys have been diagnosed with ADHD, per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, along with 15 percent of all adolescents. Seven million children have been diagnosed – more than 1 in 10. There are also 15.5 million adult cases of ADHD; 40 percent of men were identified as adults, compared to a whopping 61 percent of women, whose symptoms are less likely to be visible.

“NORMALLY, WHEN A DIAGNOSIS BOOMS LIKE THIS IT’S BECAUSE OF SOME NOVEL SCIENTIFIC BREAKTHROUGH — A NEWLY DISCOVERED TREATMENT OR A FRESH UNDERSTANDING OF WHAT CAUSES THE UNDERLYING SYMPTOMS … (BUT) IN MANY WAYS, WE NOW UNDERSTAND ADHD LESS WELL THAN WE THOUGHT WE DID A COUPLE OF DECADES AGO.”

PAUL

TOUGH, NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE

1 in 10

KIDS HAVE BEEN DIAGNOSED WITH ADHD

That’s what Canadian researchers found in a 2022 study of posts about ADHD on TikTok. Another 27 percent were anecdotal, based on personal experience. Just one-fifth of posts offered useful information. These numbers echoed similar studies on other health care topics across social media platforms, like Reddit or YouTube.

Scientists have found no concrete measure of ADHD — no brain anomaly on an MRI, no gene sequences — though it’s often described as “genetic” and is nine times likelier to recur among siblings. Symptoms overlap with anxiety, PTSD or autism — ergo the modern grouping “neurodivergence.” But environment is a factor, and just 1 in 9 kids diagnosed with ADHD experience symptoms throughout childhood.

PRESCRIPTIONS FOR ADHD MEDS ROSE 1/5

One in 4 American adults suspect they have ADHD but have not been diagnosed.

15.5 million

ADULTS

Per The New York Times, this seems to indicate environmental causes, rather than a brain deficiency.

58%

$122.8 BILLION

Between lost productivity, unemployment, doctor’s visits and medications, the disorder is estimated to cost Americans $14,092 per adult each year, as of 2021. That’s more than the average cost of in-state tuition for a four-year university. The market for ADHD medications was assessed at $15.2 billion in 2024 and is expected to balloon to as much as $24.1 billion by 2033.

THIS IS A crucial time for the American university system. Colleges and universities, both public and private, are grappling with their place in a changing world. Costs are skyrocketing, as is student loan debt. Technology threatens to undermine the educational experience through AI cheating while devaluing many degrees in the workplace. Some campuses have become literal political battlegrounds, and many question the federal government’s role through the Department of Education. Amid the tumult, these institutions must prepare for a future that looks uncertain, with a clear idea of who they are and why they exist. Is college a financial investment meant to improve career prospects? Or do universities answer a higher calling? —ETHAN

BAUER

THE COLLEGE AND university system is an investment in human potential for both students and society at large. And like any investment, it should not only pay for itself but yield a financial return to any of these investors. Institutions of higher education are duty-bound to adapt in order to protect that investment as costs continue to spiral and the economy changes too quickly for most of us to keep up. Society needs these schools to prepare young people who can compete in the modern age, with specialized knowledge in fields that are valued in the marketplace.

Students would surely agree, since the main reason most of them endure to graduation is to improve their future incomes. According to a 2023 survey by Anthology, a private company that builds digital platforms for educational institutions, 59 percent of college students stayed in school to pursue higher earning potential; 45 percent enrolled in the first place to access better job benefits like health insurance and maternity leave. Students expect to emerge from their universities prepared to compete and thrive in an increasingly difficult labor market. Unfortunately, they are more likely to graduate with a burden of debt that will follow them throughout their adult lives. The average federal student loan balance today is close to $40,000. In aggregate, their burden is approaching $2 trillion, a massive and concerning debt bubble that could impact the entire economy. Meanwhile, recent years have seen a variety of educational fields fall from favor in the marketplace, from expected declines in arts and the humanities to shockers like engineering and computer science. Students shouldn’t be weighed down with debt for degrees that are losing value. There may be no obvious solutions. Perhaps the country should invest more in vocational programs. “Welders make more money than philosophers,” as Secretary of State Marco Rubio said in 2015. “We need more welders and less philosophers.” Or maybe universities should trim general education requirements to let students focus on developing expertise in their chosen fields. Highly specialized degrees could be more narrowly targeted and, therefore, cheaper. Either way, we must accept that higher education today exists as professional training first; anything else is a luxury that few can afford.

HIGHER EDUCATION HAS always been about our future as a society, an effort to develop not just better workers but more complete human beings. A range of sources contribute to funding the cost of each student’s education, from state and federal governments to churches and philanthropic foundations. They do so as more than a financial transaction. They’re investing in the unique ability of colleges and universities to shape informed, mature and well-rounded citizens who can contribute to the American experience.

A three-dimensional education — common at religious schools — has transcendent value. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints believes that the end goal of education is “the development of a refined, enlightened, and godly character.” Jesuit institutions embrace the principle of cura personalis, or “care for the whole person” in Latin. Students appreciate this, as one Gonzaga senior told a school publication: “This is so important during college, when so many of us are figuring out who we are and how we want to show up in the world.”

Students should become engaged citizens with critical thinking skills and the spiritual maturity to navigate a complex world. At the University of Chicago, the “Core,” a 15-course curriculum that emphasizes science, writing and the humanities, has made undergraduate degrees more valuable. “The Core teaches undergraduates how to think critically and how to approach problems from multiple perspectives,” the university writes. “The goal is to cultivate in students a range of insights, habits of mind, and scholarly experiences … (that) fosters an enduring dedication to reflection and learning.”

Institutions must find cost-effective ways to educate students without sacrificing the values that make learning worthwhile. Many offer workout spaces and recreational sports, recognizing their intrinsic value. “In an era where sedentary lifestyles are increasingly prevalent,” writes one researcher, “(physical education) offers a necessary counterbalance, promoting physical health, mental well-being, and social interaction.” Colleges and universities should expand this approach to all aspects of the person.

BY ANN GOREWITZ

It was a spectacular afternoon on Sunday, June 27, 1976. It had rained every Sunday for three weeks straight, but on this day, the sun shone.

“For better or worse. Till death do you part,” said our rabbi, as Steve and I shared the moment — excited and nervous — under a canopy on my uncle’s sprawling lawn, surrounded by our family and friends.

Almost 50 years later, Steve lay in the palliative care unit in a New York hospital while I lay in our bed, less than three miles away. On that still April night, my cellphone jarred me out of much-needed sleep. “Your husband passed away a few minutes ago,” the nurse told me. “It was peaceful. I saw the photo by his bedside. What a beautiful family.”

I had left the snapshot by Steve’s bedside months ago, to remind the staff that he was a person who was healthy once, and very much loved.

But I wasn’t at his side when he died. Staff had chased me out that evening, upholding Covid-era restrictions and curfews. The last thing I said to him as I held his hand, black and blue from the

IV needles, was, “You’re my world. I love you. You’ve made my life so happy. See you tomorrow, sweetheart.”

He crept out of a coma-like sleep and smiled.

After I hung up the phone, I dressed, washed my face and wailed, not caring if my neighbors heard me. Then I called a car service. For the first time in my life, I

THERE WAS NEVER A DAY WHEN MY HUSBAND AND I DIDN’T SAY TO EACH OTHER, “I LOVE YOU.”

felt intense despair, deep in the pit of my stomach. All hope and prayers for Steve to get better vanished.

I didn’t know who to turn to for support. He was my anchor, my go-to person whenever I had a question, an idea, or the littlest, most banal something happened. There

was never a day when my husband and I didn’t say to each other, “Good morning.”

“Have a good night’s sleep.” “I love you.” Steve and Ann, Ann and Steve. Our names, intertwined, always sounded so perfect together. How could I go forward without him?

WE GREW UP a block apart in a New York City blue-collar neighborhood, but we didn’t know each other until we were both teachers at P.S. 20 in Fort Greene in Brooklyn. Thanks to some casual pleasantries, Steve and I discovered we were raised in the same neighborhood and went to the same schools, but never knew one another. I was a grade ahead, which made all the difference as a teen.

Was it love at first sight? Far from it. It was only after, in the early hours of the morning and coming out of deep sleep, a little voice, like a dream, acknowledged Steve’s best qualities that I truly realized them. “He’s good-looking, smart, compassionate and levelheaded with the best common sense on the planet.”

It made me look at him differently. Those

blue eyes. How could I not have noticed them before?

A week later, after dinner at an outdoor cafe followed by a Fellini movie that I didn’t understand, someone held someone’s hand. And that was it. Neither of us ever wanted to let go. And we didn’t. Until.

We were married for 45 years. Not able to have children, we devoted ourselves to our careers, an apartment in Manhattan, a cottage upstate where Steve’s garden flourished, and a beloved dog, Cassie.

We grew our lives together, side by side. Steve developed a successful career as an advertising executive, and I began working in corporate human resources. Even though our salaries were good, having grown up in households where a lack of money was a constant challenge, we saved. We had no pensions. So, we saved even more.

We fantasized about retirement. Then, we thought, we could finally relax. We could be at the cottage more. We could travel more. We’d have time to explore new hobbies. Steve’s dream was to visit Buenos Aires, where his father was born. Living in Europe for a few months was mine. A retirement specialist advised us in our 50s, “Just keep doing what you’re doing. You’re in great shape.”

Then, before we got to spend the money on all the things we’d been dreaming up for years, Steve died. We’d saved and saved, and it bothers me that he didn’t live long enough to enjoy what we’d worked so hard for, and that we’d never do those things we spent so many days talking about together.

Even though Steve was ill for several years, I never allowed myself to think for one moment that he could die. It’s the part of life and adulthood that I wasn’t ready for. It’s the part I put out of my mind and our life together. “He will get well,” I told myself many times. But too often it doesn’t work out that way. If you’re a woman aged 65 or older, there’s roughly a 2 in 5 chance you’re already widowed, and those odds rise sharply with age. If you’re a man who’s 65, it’s closer to 1 in 8, but those odds increase by over 40 percent by the time you’re 85 or older.

When you get married, you only think about everything that you’ll do together. You celebrate the traditional idea of “two becoming one.” But nothing prepared me for what happens when two become one at the end, and you’re the one that’s left.

MY MOTHER LOST two husbands. My motherin-law lost one. Even though I saw each of them go through the deaths of their husbands, it didn’t give me any real sense of how hard it actually is. They never spoke about their experiences. It seems like few

people do, even though in the United States, between 900,000 and 1.5 million people lose a spouse each year. This includes both men and women. But there was no passed-down wisdom or past conversations for me to call upon when my turn came. Losing your spouse — a life experience that many who have the good fortune to get old have the misfortune to experience — was uncharted territory. And I didn’t have a map to navigate this new reality.

There are the practical things, like accounts and bills and keeping a home up

and running. Steve was in charge of our finances. He was good at it — watched financial news, followed the markets and made conservative decisions. Now I’m in charge. He showed me the files before each of his many hospitalizations. But that wasn’t enough. It’s taken me years to figure out how to manage the accounts myself. At our cottage, neighboring houses are scattered, blackouts are frequent, and I don’t have many friends. There’s no super to fix things, and Steve enjoyed tinkering with things enough to repair them. I’m learning and reaching out to people.

Then there are the intangible things — the stuff that you can’t call a handyman about or research online. When you lose your person, you lose an aspect of your identity — a loss that is also felt during the transition into retirement. You were once a corporate manager with a team, now you’re a lone retiree. You were once a wife, now you’re a widow. It’s a one-two punch. With the loss of personal identity also comes the loss of a schedule, personal connections, to-dos, conversations and goals. What do you do with your day? Who are you? Who do you ask when you can’t answer that yourself?

These practical and intangible realities swirl together like milk into coffee; there’s no parsing them out. One day, I’m learning about the electrical box, and the next, I’m looking at our burial plots, remembering what Steve asked of me. “If I die first, I want you to be with someone. I don’t want you to be alone. But promise me you’ll be buried next to me.” It took me two years to finally choose a double headstone. On the left is Steve’s inscription, and on the right is mine, minus my death date. And life goes on.

It’s taken me four years to accept my new identity — a widow, a retiree, senior, single. Right after my birthday this year, I realized that at 76, I have more years behind me than in front of me. It’s time to enjoy the time I have left. Suddenly, I sleep better and cry less as I plan my future.

I’m figuring out what I want from life. I still want to travel, even if I don’t get to

live in Europe with Steve for a few months. So I’m signing up for trips. I’ll visit my brother and make plans so I’m not alone for the holidays.

This chapter of my life is a second identity and a new stage for me. “Getting back out there” looks different when you’re older. With the aging process, you can’t do some things that you used to. I used to race marathons and triathlons, but I can’t anymore. It’s too much strain on my body. I’m finding out who I am without Steve and who I am in the body that I have now. In my own ways, I’ve learned that there are accommodations

Wild West out there, but it’s mostly good fun and makes me feel like I’m a high schooler instead of a senior woman.

But even when things are feeling “normal,” I can hear a song or see a couple holding hands and find myself in a puddle of tears. When invited to a 50th wedding anniversary, I couldn’t bear the thought that Steve and I would never celebrate another anniversary. Sometimes I want to curl up and die.

EVEN THOUGH I SAW MY MOTHER AND MOTHER-IN-LAW GO THROUGH THE DEATHS OF THEIR HUSBANDS, IT DIDN’T GIVE ME ANY REAL SENSE OF HOW HARD IT ACTUALLY IS.

“Mourning is work and it has a goal,” says Dr. Eric R. Marcus, professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. “The goal is to move an internal representation of the loved one from reality to blessed memory. Then, to use that memory to accompany the person through the rest of their life’s journey, encouraging them and supporting their further growth and development. It is difficult work because at first, the loss experience overwhelms the preservation experience. Later, it is difficult because of guilt about proceeding with life.”

But I know I have to move on, even when I feel lost. Even if there’s no replacement, only the memories. And the push and pull to be resilient.

that you make to find new ways to enjoy yourself. That includes giving back, instead of taking things, from life.

I’m making new connections — exploring volunteer opportunities, taking exercise classes and working with a therapist. I’ve even joined online dating. So far, I’ve texted with several men, flirted, graduated to FaceTime conversations, and met two of them in person. One tried to passionately kiss me when we met in a museum. The second man looked like a model and texted me after a day, saying how much he loved me, calling me his soulmate. The next morning, I saw, the site administrator had pulled his profile for inappropriate behavior with several women. It’s like the

After my mother was widowed and until she passed away at 87, she filled her life up. She learned how to read and write in Hebrew, joined a seniors group, tutored children. She stayed active. I am my mother’s daughter.

And although I know Steve will always be with me, he made sure I wouldn’t be alone.

While on life support, using his iPad, he put a deposit on a newly born puppy. He watched videos of the litter and selected the one for us. The morning he passed away, I received a call. “It’s time to meet your puppy.”

I met our puppy, Romeo, the following week on my birthday, and brought him home on Steve’s and my wedding anniversary. He can be a handful sometimes, but I can’t help but adore him. Every morning, he’s cuddled next to me and I whisper, “I love you.”

THE FIRST CREDIT UNION CREATED FOR MEMBERS OF CELEBRATING 70 YEARS OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS.

Because of you, we’ve upheld a legacy of faith-centered service and values-based financial solutions for members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints since 1955. To celebrate, we’re giving back with over $100,000 in prizes—including Disneyland® trips, gift cards, and more.

To enter or learn more about our $100,000+ in giveaways, scan the QR code above.

CAN TECH FILL AMERICA’S PHYSICIAN SHORTAGE?

BY ETHAN BAUER

Three years ago, Lost Rivers Medical Center opened a day care. It was temporary at first, a result of petitions from employees who couldn’t find any other child care options in Arco, Idaho, population 879. The original arrangement could only host six kids at a time, but 19 months later, in December 2023, the hospital opened a dedicated child care facility, serving up to 24 children. CEO Brad Huerta faced questions about his choice to fund the space. Of all the things for one of the most isolated hospitals in the country to invest in, why day care? His answer was easy: It was the best option available to combat looming provider shortages.

“They’re acute everywhere,” Huerta says of the shortages, “but especially acute in rural areas.” Areas like Arco, which is more rural than the definition of rural these days, and classified in the medical industry and by Huerta as a “frontier area.” The closest city, Idaho Falls, is about 70 miles away. When Huerta took over in 2013, he admits he was the third choice for the job. The top two candidates couldn’t fathom living so isolated. “Everyone’s about being rural until it’s time to be rural,” Huerta says. “And that’s the same with doctors.” Which means

he’s gotten creative about recruitment, from the day care to student loan forgiveness programs. He’s had to.

Medical recruitment and retention are major concerns that are becoming a problem everywhere. Specifically, a math problem: Older doctors are retiring, and medical schools aren’t producing enough new

“WE HAVE PROBLEMS IN OUR HEALTH CARE SYSTEM AND ARE HOPING THAT AI IS A PANACEA. BUT A LOT OF THE ENTHUSIASM IS BECAUSE THERE AREN’T OTHER GOOD OPTIONS.”

doctors to replace them as the American population ages. The Association of American Medical Colleges’ most recent report predicts a physician shortage of 86,000 nationwide by 2036, which could unleash longer wait times, reduced access and worse outcomes for patients. The way people receive care has already changed significantly,

with the American Medical Association reporting private practice physicians are dwindling amid a rise in web-accessed and hospital-centered care that promises to reduce administrative burdens for doctors.

But technology could help fill the gap. “Not only can it help — it will have to,” says Dr. Joseph Kvedar, a Harvard Medical School professor and former president of the American Telemedicine Association. “This shortage is already manifesting. And if we don’t harness tech to do more work for us, we’re never going to get ahead of it.” The key, he adds, will be using different technologies to supplement human-centered care and avoiding an overreliance on tech that further undermines the increasingly fragile trust between patients and providers.

“I am a big believer that technology can augment what we do to make care better,” adds Dr. Shivan Mehta, a gastroenterologist and Penn Medicine’s associate chief innovation officer. However, “just because you throw technology at something doesn’t mean it’s going to work well.”

THE JOB OF “doctor” in the modern, Western sense can be traced to 1910, when educator Abraham Flexner published “The

Flexner Report,” a book documenting the haphazard state of the nation’s medical schools. An outgrowth of Jacksonian America, populism painted universal medical standards as an unfair monopoly, unleashing a range of water healers, herbalists and other alternative practitioners to compete directly with medical doctors.

“You could practice medicine if people believed you could practice medicine,” says Mary Fissell, a medical historian at Johns Hopkins University. “The Flexner Report” wasn’t perfect — critics point out that it codified racist and sexist practices that still impact patients today — but it also set the table for many rigorous medical education and certification standards.

Out of Flexner, many medical education best practices were borne, drastically elevating standards of care. The way people became doctors, and the way patients accessed them, took a formal shape as supply grew to match demand — especially once Medicare was established in the 1960s. Where doctors once visited homes, patients started traveling to offices more frequently. The Medicare program also funneled federal dollars toward residencies and medical specializations, which led to a boom in doctors to meet the new demand from patients. Today, though, the equation isn’t working like it once did, leading to shortages. “You could say,” Fissell says, “that that is in part the very long shadow of Flexner.” The link goes back to those rigorously enforced standards, which are made possible in part by federal funds. Between 1997 and 2021, though, those funds were fixed, effectively limiting the number of new doctors with an artificial cap. The American Medical Association supported this cap, believing that a doctor surplus would devalue medical degrees, until the problem became too big to ignore. Congress approved funding for additional residency slots in 2021, and again in 2023, with proposals to add even more in the years ahead. But for now, the supply is still drastically lagging. “We do not train enough physicians,” Fissell says. “There are not enough medical schools or residency places.” With

an aging population that’s ever more likely to require ongoing access to health care, that’s a problem. And for some places more than others. “Doctors are unevenly distributed,” Fissell says. “There are fewer in rural areas, which worsens shortages.”

Sophie Hofeldt, a pregnant woman in rural South Dakota, was born at a local hospital herself. But a May report from the Kaiser Family Foundation detailed how that local hospital — like many in rural America — had recently closed its birthing unit. Hofeldt was driving almost 100 miles for prenatal care, and would have to make that drive yet again to deliver her baby. She wanted her birth to be as natural as possible, but that meant difficult compromises. “People are going to be either forced to pick an induction date when it wasn’t going to be their first choice,” another pregnant woman told KFF, “or they’re going to run the risk of having a baby on the side of the road.”

“NOT ONLY CAN TECHNOLOGY HELP — IT WILL HAVE TO.”

AS AN INDUSTRY, health care thrives on volume and efficiency. Money is made based on the number of patients who come through the doors, so providers are highly incentivized to see as many patients as possible, as quickly as possible. This tends to result in a much more impersonal kind of care. “The old model where you would have a doctor for a long time, that would get to know you,” Fissell says, “for most people, that’s just a complete fairy tale.” Especially among younger people. A 2021 survey by Accenture, a tech consulting company, found that millennials and Generation Z are nearly six times more likely to switch providers than older Americans.

Short-lived patient-provider relationships come with some interesting side

effects. Wellness influencers are ascending as cheaper, accessible alternatives to traditional medicine. And trust in physicians and hospitals declined by 31 percentage points between 2020 and 2024 alone, meaning that nearly a third of Americans lost trust in doctors in a four-year span. At a time when medical literature is widely accessible, many people, empowered by services from WebMD to ChatGPT, are taking diagnoses into their own hands. To Fissell, it’s a modern echo of Jacksonian America, when medicine was more about belief than standards. Nowadays, though, the key to reversing the trend isn’t new standards; it’s better access to the rigorous, scientific care landscape we’ve built in the last 100 years.

That’s where technology makes its biggest promises, starting with telehealth specifically. It’s become a mainstay post-pandemic, offering doctors and patients a previously unimaginable level of flexibility. According to a study released by the National Center for Health Statistics in 2021, over 80 percent of physicians in office-based settings used telemedicine for patient care, up from 16 percent in 2019. Telehealth can open doors for patients to receive specialty care that used to be limited by geography, while also requiring less of a time commitment; not having to drive to and from the office, plus wait while there, can be empowering and convenient. And research has shown it offers similar quality-of-life benefits for doctors.

Telehealth can be especially helpful in isolated, rural areas, as long as those areas have reliable internet access and as long as insurance companies agree to cover it. “It changes the access equation,” says Kvedar, the telemedicine leader. But it also doesn’t make medicine much more efficient — let alone more human — because “you’re still tying two people up in time, and there’s only so much clinician time to go around.” But other technical solutions could close that gap, too. Kvedar envisions a future where remote monitoring becomes the norm, especially for rural communities. If a doctor treats 100 patients, and she can track their blood pressure and other vitals remotely, she can

focus her time on the patients who need her the most. That way, limited access can be prioritized for the most vulnerable without leaving anybody out.

But no technology embodies both the potential and pitfalls of using tech to bridge health care access gaps as much as artificial intelligence. It provides a microcosm for what can go right when tech makes health care more accessible. And what can go wrong.

AI programs like DeepScribe and Abridge perform “ambient listening” by taking chart notes during appointments, thus freeing up providers to interact more directly with patients. That’s good for patients, who can see their providers face-to-face. It’s also good for providers, who don’t have to spend time between visits charting and can instead see more patients. Adam Rodman, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School leading the school’s work on generative AI, says that’s exactly how AI — and technological solutions more broadly — can be leveraged effectively: as an extension of, rather than a replacement for, human treatment capabilities. “As opposed to what’s largely happening right now — which is smacking AI on a pretty dysfunctional system.”

The danger lurking in the widespread adoption of AI, telemedicine, texting platforms and other technological solutions is the further degradation of trust. Not just because of potential privacy concerns, like potential data breaches and profiteering by revenue-driven tech companies. But also, in a more big-picture way, by making medicine less human than it should be. Kvedar is right that technological solutions will have to be part of the solution to the physician shortage and resulting threats to access. But tech also can’t solve the industry’s issues alone. “We have problems in our health care system and are hoping that AI is a panacea,” Rodman says. “A lot of the enthusiasm is because there aren’t other good options.”

WHEN ARCO’S LONE pharmacist retired at 84, the town couldn’t find a replacement. No one

wanted to move there to take over. That led Huerta to establish a partnership with Idaho State University, whose students could staff Lost Rivers’ pharmacy under remote supervision from licensed pharmacists in Pocatello. Thanks to telemedicine, residents of Arco wouldn’t have to drive 50 miles to the next closest pharmacy for their medications.

Similar programs already exist elsewhere. Project ECHO, for example, which started in New Mexico and has expanded to all 50 states and dozens of foreign countries, connects rural primary care doctors with virtual continuing education and specialist consultations. If a rural Nevada doctor can treat heart problems locally, by consulting through Project ECHO with a cardiologist in Reno or Las Vegas, patients

THE MOST RECENT RESEARCH PREDICTS A PHYSICIAN SHORTAGE OF OVER 86,000 NATIONWIDE BY 2036, WHICH COULD UNLEASH LONGER WAIT TIMES, REDUCED ACCESS AND WORSE OUTCOMES FOR PATIENTS.

can avoid traveling to distant cities. If towns in rural Nevada, or places like Arco, didn’t have these kinds of programs, they’d almost certainly lose primary care entirely. It almost happened in Arco shortly after Huerta arrived.

The hospital had declared bankruptcy and needed a $5.5 million bond measure to stage a comeback. “In genuinely rural areas, genuinely critical access areas, a hospital is probably the only clinic you have access to,” Huerta says. It’s an issue that could become more widespread in metro areas, too, as the number of providers shrinks relative to the population seeking care.

At Lost Rivers, one long-term solution is working with staffing agencies. Every hospital, he explains, uses staffing agencies to

broker access with, essentially, “substitute doctors” — that is, doctors who can fill in quickly when needed. These doctors, called “locums,” are exceptionally expensive. But long term, staffing agencies can match hospitals in need with doctors over time, and for much less. A doctor at Lost Rivers, for example, might spend one week in Arco every month before returning home to Boise or Salt Lake City. But that doctor would come back again and again, month after month, meaning patients could build a relationship with that doctor. “I think this is the model of the future, frankly,” Huerta says. But how long will that hold as the shortage worsens? Especially when, in Arco and beyond, access is already threatened in other ways.

Shifting regulations, like Idaho’s recent Medicaid cuts, make effective administration nearly impossible. Even Huerta’s pharmacy innovation was initially rejected by a state board. And private insurers present even greater obstacles. “The big thing killing health care, frankly, is the payers,” Huerta says. “The delay and denial of claims is standard practice.” Their response to telemedicine perfectly illustrates why technology alone can’t fix the access problem. When telemedicine emerged, insurers refused to recognize it as legitimate. “Why would I adopt telemedicine,” Huerta asks, “if I’m not going to get paid for it?” Eventually, they covered it at a reduced rate but excluded certain visits, like those related to mental health treatment. “OK then,” Huerta thought, “what’s the point of having psychiatrists on staff?”

That’s why he’s turned not just to technology for fixes, like the virtual pharmacy, but to human ones, too. Like the day care. So far, that’s been enough. For the first time in his tenure, Lost Rivers is fully staffed. Its turnover rate is dropping. And for that, Huerta credits not technological innovation but something with a pulse — something he tells people when he’s trying to recruit them: “This is the job you’re going to look back on when you’re old and retired and go, ‘Man, I really did something with my life,’” he says. “‘I made an important difference.’”

BY NATALIA GALICZA

Ricardo Jimenez didn’t really know what he wanted to be. At one point, he thought he’d figure it out in college, like most young adults in America plan to do. He’d enrolled at the University of California, Merced in August 2020, but just as soon as he started to make sense of the world around him, a pandemic morphed it into something else altogether.

He chose to major in a management, business and economics program to learn the ins and outs of enterprise. Rather than fall to the mercy of a volatile job market, he wanted to own his own business. Be his own boss. But even after he started his second year, he still had no clue what kind of business he wanted to run. The only clear thing was that any student debt would only delay his plans. So he got his commercial driver’s license and took a summer job hauling ice across central California to help pay his way through school.

The job entailed driving tens of thousands of pounds of steel through the Sierra Nevadas, stopping at turnout areas before driving downhill to make sure the heat and friction didn’t kill his brakes. Pulling into

tight parking spaces at gas stations, getting cut off by reckless drivers and blocked in by careless shoppers. Carrying thousands of 20-pound bags from pallets in the truck bed into shops, struggling to catch his breath in the thin mountain air while doing so, then neatly stacking them up in freezers. It was always grueling and often thankless — except for the store owners who

love driving, listening to music and being able to look at the mountains,” he says. “Not a lot of people could say they have that view when they’re working.”

showed their gratitude for a job well done with complimentary soda and gas station snacks. But every time he hopped back into the driver’s seat, he saw miles of open road and canyons of granite that enveloped him. He looked down on alpine lakes and valleys filled with pine trees. And it felt worth it. Peaceful. Freeing, even. “I love the views. I

Jimenez didn’t expect to love trucking. That discovery unlocked a career path he hadn’t seriously considered when he was still in his teens, wondering what his life would look like. But jobs in blue-collar fields like trucking, plumbing and welding are now growing in popularity among young adults trying to find a hold in the job market. A May report by Resume Builder found that 42 percent of Gen Z adults — those born between 1997 and 2012 — are now pursuing blue-collar jobs. For Jimenez, there’s the timeless appeal of work that’s always in demand, that has fewer barriers to entry, that increases his odds of becoming a business owner. Benefits that have become especially attractive at a time when a stable living feels elusive.

Unpredictable tariffs and trade wars have led white-collar businesses to slow hiring across the country, leading to one of the worst job markets in a dozen years. That leaves job seekers in a financial

hole, especially since the average bachelor’s degree holder graduates with around $29,000 in federal student loan debt, and less than half of borrowers pay off their debt during the 10-year standard federal loan repayment plan. A new analysis of U.S. labor data found that unemployment rates for men age 22–27 with college degrees are now roughly the same as those without degrees. In tandem, more and more jobs are becoming at least partly automated through technologies like agentic and generative AI. But in a time where entering the management track at a company is suddenly precarious, blue-collar fields like trucking remain necessary — and can be lucrative. “You could make money. You could control your own destiny. Many people go into trade jobs, end up owning their own businesses, and their jobs can’t be taken away by AI,” says Stacie Haller, a nationally recognized career expert and the chief career adviser at Resume Builder. “AI is not going to style your hair or fix the pipes under your sink.”

With the certainty that demand and a specialized skill set bring, jobs across the blue-collar market are attracting young workers, like electricians, plumbers and HVAC technicians. These jobs are estimated to experience anywhere from 6 to 11 percent growth in the coming years, and the blue-collar job sector is estimated to open up hundreds of thousands of jobs.

It didn’t take much college for Jimenez to figure out what he wanted to be. His summer job hauling ice made it clear. He, like anyone thrust into an era of uncertainty, wanted to be secure.

BLUE-COLLAR WORK BUILT America from the ground up. In the West, cities developed around physical economies like the cattle trade, ranching, grain farming and mining. Manual labor proved requisite for a functioning society, so jobs in those spaces were well sought after and respected. It was only in the post-industrial 20th century, when technology and machinery displaced jobs in manufacturing, that white-collar work became an American norm.

With automation to consider, jobs that required service-based skills and human interaction were seen as more secure and professional. The thinking was: Manual labor took an unglamorous toll on the human body, and technology was taking those jobs anyway. Instead of mass producing goods, workers could be developing new technologies, conducting research and thinking deeply — things machines couldn’t yet do. That led to the harmful assumption that intelligent people who want a stable living need to pursue higher education and break into white-collar fields like finance or law or tech. “College became the golden ticket to having a good life. Not so much anymore,” Haller says. “It’s not a golden ticket if you have no money for the next 15 years, paying off your college loan.”

Ironically, it’s now technology that’s bringing those same white-collar jobs to

“AI IS NOT GOING TO STYLE YOUR HAIR OR FIX THE PIPES UNDER YOUR SINK.”

the altar of automation. A report conducted by LinkedIn in May found that 63 percent of surveyed executives at the vice president level or higher agreed that artificial intelligence would take on some workplace responsibilities currently given to entry-level employees. Another study by The Harris Poll found 45 percent of Gen Z job seekers in the United States feel that artificial intelligence has rendered their college education irrelevant in the current job market. Just over 50 percent now view their degree as a waste of money.

Office jobs like data entry, bookkeeping, administration and legal research are most vulnerable. Skilled trades like construction or trucking, though, are among the least threatened careers. “This whole culture was built around white-collar jobs — that if you’re smart, you go to college. Thank

God that’s going away because it’s not true,” Haller says. “There’s no job security anymore. Even if you’re getting paid a lot of money in a white-collar job, your company could get sold, or a tariff could kill your business. But there could be more job security if you go into some of these blue-collar jobs, because you get licensed, you’ve got a skill.”

The renewed interest in labor is compounded by the fact that baby boomers in the workforce are gearing up to retire. There’s demand, there’s supply, there’s even access. Vocational schools train students for specific blue-collar careers and are often far less time-consuming and expensive than a college education. The National Student Clearinghouse found that the percentage of students pursuing vocational training has grown about 20 percent in the last five years and has grown consecutively for the last three. Those students gain wealth quicker than their white-collar counterparts, finishing training within a couple of years and diving directly into jobs with competitive pay. The average entry-level salary for a white-collar worker, according to Glassdoor, starts at $48,000 a year. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports the average wage for nonunion blue-collar workers in fields like construction, maintenance, production and transportation is about $24 an hour, or $49,920 a year. That average jumps up to $68,931 for union workers.

There’s also the thrill of working with your hands, spending time outside, taking in beautiful views, using your body and your brain in tandem — qualities workers can’t access from behind a desk. “There’s always been the romance of the open road, especially for young people who are blue collar and haven’t traveled much,” says Steve Viscelli, an economic sociologist who studies work, labor markets, automation and public policy at the University of Pennsylvania. “There is definitely an appeal in getting in a truck and driving around the lower 48 states. That stuff is real for people who get into the industry.”

Jimenez still thinks about his first trucking job hauling ice across California in the

dead of summer. His hometown, Patterson, which sits in California’s San Joaquin Valley, is flat and familiar. Those first rolling green foothills and rocky ridges he saw on delivery drives made his world suddenly feel as though it had cracked open — like he was a part of something bigger. He chased that feeling.

In 2022, months after his ice delivery gig, he took a chance and bought his own semitruck. He used it to deliver cargo to the Port of Oakland from the Turlock, Oakdale and Modesto area for a month and a half over his winter break. When his classes resumed and he had to focus on being a full-time student again, he hired a driver. A year later, he purchased another semitruck and hired another driver. By the time he graduated at 22, he owned his own trucking company, Fast Boy Logistics. He now has a fleet of three semitrucks and two drivers, both of whom are 22 years old.

Trucking is the dominant mode of transporting cargo in all of North America, accounting for more than 60 percent of transported goods between the United States, Mexico and Canada. Last year alone, truck drivers moved $1 trillion worth of freight — almost as much money as the entire national deficit. They carry everything from office supplies to hazardous materials. The groceries Americans need to feed their families, the gasoline that gets them to work on time, the medication and pharmaceutical equipment that keep them alive. “It’s not just about driving. It’s about carrying a certain type of respect for other people while we’re on the road, keeping a good name for yourself and for truckers in general,” he says. “Everything revolves around trucking.”

MANUAL LABOR COMES with its own challenges. Physical demands mean blue-collar workers are more likely to develop injuries or health complications. Labor conditions are, in many cases, lacking or unjust. And the stigma that trade workers are uneducated or otherwise of low status still lingers. When the No Child Left Behind Act

passed in 2002, success in schools shifted to focus squarely on standardized tests. Performance on these exams dictated ratings and funding for schools, so curricula formed around setting up students for high scores and getting them into four-year universities. That came at the expense of extracurricular classes focused on giving students exposure to trades like woodworking and auto shop. The result was the gradual devaluing and lack of awareness of careers in blue-collar professions. A report by Credit Karma last year found that nearly 20 percent of surveyed Americans who attended or are currently attending a four-year college did not have any knowledge of alternative paths to education like vocational schools. That number jumps to more than 30 percent for Gen Z respondents.

“THIS WHOLE CULTURE WAS BUILT AROUND WHITECOLLAR JOBS — THAT IF YOU’RE SMART, YOU GO TO COLLEGE. THANK GOD THAT’S GOING AWAY BECAUSE IT’S NOT TRUE.”

Blue-collar grew to be a derogatory term, something used euphemistically with “low class” to offend laborers. Pew Research Center reported in March that 35 percent of blue-collar workers say Americans don’t have much — or any — respect for their work. For generations, that’s affected the workers in those roles and even discouraged young adults from entering trades. “Most truck drivers would say it’s a very low-status occupation currently,” Viscelli, the economic sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania, says.

Even Jimenez would agree that stigma still exists. But he and the other Gen Zers entering trades are looking to shake it. “There’s this conception that truckers are all pretty much dirty, and don’t treat things with respect,” he says. “It’s a real career. It’s an actual job.” School districts across the country

are now backtracking due to the growing demand for blue-collar work among younger generations, spending tens of millions of dollars to reinstate shop classes for students. The Patterson Professional Truck Driving School at the eponymous high school in central California is one example.

The program is one of the nation’s first high school trucking classes; a yearlong course with 180 hours of instruction on professional trucking to prepare students to take a commercial driver’s license exam upon graduation. Retired truck driver Dave Dein created the program and has taught it for the last eight years. According to him, four of his graduates have gone on to own trucking companies. Jimenez included.

Dein remembers being a high school student with no clue of what his future would look like. He failed classes and got into trouble, then started driving a truck in 1988 as a way of paying his way through college. That’s when he found something he felt passionate about, that came naturally to him. He wanted to make sure other young people didn’t lose that option. “We’re losing about 25 percent of our drivers over the next five to seven years, because they’re aging out and retiring, and we’ve done a horrible job as far as building this pipeline for young, well-trained talent,” he says. Dein’s curriculum has made it into classes at more than 50 high schools across the country that aim to teach students the basics of truck driving. It’s helped students like Jimenez forge their own path and pursue their dream of becoming a financially independent business owner — someone in charge of their own fate even in the face of so much change.

Jimenez is now a regular guest speaker for the Patterson Professional Truck Driving School that’s offered at the high school he graduated from. When he finds himself at the front of Dein’s classroom, looking out at students sitting in desks he sat in himself just a few years prior, it almost feels surreal. He talks to them about going from someone who was once entirely unsure of his future to someone who, however minutely, makes the world go round. And that feels good.

TODAY’S STUDENTS ARE PAYING MORE, LEARNING LESS AND GRADUATING INTO UNCERTAINTY. WHAT HAPPENED TO THE PROMISE OF COLLEGE?

BY CLARK G. GILBERT, TED MITCHELL, DERRICK ANDERSON, BETH AKERS AND DAVID A. HOAG

ILLUSTRATION BY GREG MABLY

THERE WAS A TIME — NOT SO LONG AGO — WHEN THE VALUE OF A COLLEGE DEGREE WAS SELFEVIDENT. IT WAS THE SUREST PATH TO OPPORTUNITY, THE ASSUMED NEXT STEP AFTER HIGH SCHOOL, A MARKER OF MERIT AND AMBITION.

parents planned for it . High schools funneled students toward it. And as a society, we treated college not just as a financial investment, but as a rite of passage, a symbol of upward mobility, and a cornerstone of civic life.

But that consensus is beginning to fracture. Enrollment is down. Public trust is eroding. And for millions of students and families, the basic promise of higher education — that it will lead to a better, fuller, more secure life — now feels uncertain.

This special issue of Deseret Magazine explores three intersecting crises reshaping the future of American higher education: the crisis of cost, the crisis of relevance and the crisis of meaning. For this issue, we asked thought leaders from across the education landscape to engage the most practical — and pressing — questions families now face: Is college worth the price? Will it prepare me for the world of work? And what kind of person will it help me become?

Elder Clark G. Gilbert, commissioner of the Church Educational System for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, opens the issue with a call to re-center higher education on purpose. In a time of rising religious disaffiliation and emotional dislocation, Gilbert argues that faith-based and faith-inclusive universities offer something young people desperately need: a community of belonging, a structure for spiritual exploration and a deeper sense of meaning.

Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education (ACE), and Derrick

Anderson, the former senior vice president at ACE, write about the broader challenge of relevance. As they see it, the problem isn’t that higher education has nothing to offer — it’s that the sector must evolve. Mitchell and Anderson defend the civic and democratic role of colleges and universities, but argue they must do more to align their programs with the demands of today’s workforce.

Economist Beth Akers offers surprising solutions to the affordability dilemma. She calls it the “ROI problem” — the growing gap between what students pay for college and the real-world value of the degrees they earn. But Akers also offers hope: With better data, clearer expectations and stronger financial literacy, students can still make smart, future-oriented choices.

Finally, David A. Hoag, president of the Council for Christian Colleges & Universities, revisits the crisis of meaning from a campus leadership perspective. He reflects on how colleges once saw themselves as moral communities — places where students could develop not just intellectually but spiritually and ethically. Reclaiming that identity, he argues, may be key to restoring trust and transforming lives.

Together, these essays suggest that it’s not too late to save American higher education. But it will require change, namely institutions that are affordable, relevant and grounded in purpose. And it will require a renewed national conversation about what college is for — not just in economic terms, but in moral ones too.

BY CLARK G. GILBERT

America ’ s college - age students are facing an emotional and directional crisis. A recent Harvard Graduate School of Education study showed that nearly 3 in 5 young adults feel a lack of purpose in their lives. Half of that same group describe their mental health as being negatively impacted by “not knowing what to do with my life.” The well-documented rise in anxiety and depression in Gen Z has been linked to what a former U.S. surgeon general has called an “epidemic of loneliness and isolation.”

Many social scientists, including Robert Putnam, Jonathan Haidt, Jean Twenge and others have linked this rise in anxiety, depression and loneliness to the emergence of smartphones and social media. It is a painful irony that the most digitally connected generation in history is also the most socially isolated. But there is another concurrent trend that may be equally challenging to this generation in crisis — the rise of the religiously unaffiliated.

Social scientists have repeatedly demonstrated the moderating impact religious engagement has on loneliness, lack of purpose and emotional resilience. For example, an American Enterprise Institute survey found that millennials are dramatically more likely than baby boomers to feel lonely. And yet that gap disappears when millennials attend church, live in a familiar community and marry. Why? It seems that

these practices provide secondary spaces for gathering and support that are often lacking for nonbelievers who remain single into adulthood. As for a sense of meaning and purpose, a large empirical analysis using the General Social Survey data shows that those who are confident in God’s existence report a higher sense of purpose than non-

AT A TIME WHEN MANY YOUNG ADULTS ARE TURNING AWAY FROM RELIGION, FAITH-BASED AND FAITH-INCLUSIVE UNIVERSITIES CAN PROVIDE THE BRIDGE TO REAWAKEN SPIRITUAL EXPLORATION, DEEPEN A SENSE OF PURPOSE AND PROVIDE A COMMUNITY OF BELONGING.

believers. This finding is consistent with many other studies, including the Harvard study referenced earlier. Both confirm that those who belong to any religion are more likely to report meaning or purpose than those who do not. Why? Religious participants tend to find purpose in connection to deity, relationships with others and

service, which are more often present in a faith community. Finally, meta-analysis of multiple peer-reviewed studies shows that religiosity is positively related to emotional resilience. Why? Religious engagement provides support structures, mentoring and value systems that help people face emotional challenges.

Maintaining religious belief does not mean that the isolation, distraction and emotional challenges of modern society go away. Yet the data is clear — religion provides one of the greatest moderating influences to these crises, and there are few emergent substitutes. As a New York Times columnist recently described: “Americans haven’t found a satisfying alternative to religion. Is it any wonder the country is revisiting faith?”

Enter faith-based universities whose religious engagement offers a bridge to faith for college students at the very time they may need it most. Despite the rise in religious disaffiliation, faith-based universities are growing. The National Center for Education Statistics shows that faith-based university enrollment is outpacing the national average. In the educational system in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, net enrollment since 2000 at Brigham Young University, BYU-Idaho and now especially BYU-Pathway has increased by over 100,000 students. Some of that growth has come through innovations in educational access. But from Notre Dame to Baylor, and Yeshiva to BYU, students want to learn in an environment that has clarity of purpose and develops the whole person.

Some of these students are simply searching for the character of conviction. For example, enrollment at Yeshiva University has been overwhelmed by students of diverse faith backgrounds. Why do they come to the nation’s preeminent Jewish university? According to school administrators, these students want to study in an environment where academic freedom doesn’t come at the expense of moral clarity. At other institutions, students want to learn in an environment that engages them spiritually.

RELIGION PROVIDES ONE OF THE GREATEST MODERATING INFLUENCES TO THE CRISES OF ISOLATION AND EMOTIONAL CHALLENGE, AND THERE ARE FEW EMERGENT SUBSTITUTES.

While many in the media are quick to highlight the growing disaffiliation from formal religion, they often fail to note that young adults also remain spiritually aspirational. A 2024 Springtide Research Institute study found that 79 percent of young adults consider themselves part of a religious or spiritual community and 46 percent engage in daily or weekly prayer. Schools that minimize or prohibit such expressions of faith deprive students of such anchoring. Another significant benefit that faith-based universities provide is a sense of belonging and community. Many young adults have grown up in an environment that feels hostile to their beliefs. Coming to a faith-based university provides a safe community of shared identity.

I admire Eboo Patel, president of Interfaith America, who has stated that there is “no pluralism without particularity.” Faith-based universities are one way of preserving pluralism by preserving the particularity of religious expression in American higher education. But this same pluralism can also be preserved when secular institutions make space for faith on their own campuses. Those of us who represent faith-based universities extend our praise and gratitude

to the leaders of secular institutions who provide access and visibility to campus programs such as the Jewish Hillel, Latter-day Saint Institutes of Religion, Catholic Newman Centers and InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. These campus communities provide and bolster vital belonging that students desperately need.

This fall, a documentary entitled “HIGHERed: The Power of Faith-Inspired Learning” will launch on BYUtv. This three-part series captures the social good created by the more than 850 faith-based universities who serve over 1.8 million students. We hope others will recognize how faith can moderate feelings of isolation, a lack of direction and anxiousness that plague a generation. At a time when many young adults are turning away from religion, faith-based and faith-inclusive universities can provide the bridge to reawaken spiritual exploration, deepen a sense of purpose and provide a community of belonging that has too often been missing for a generation of college students.

IS A GENERAL AUTHORITY SEVENTY AND COMMISSIONER OF THE CHURCH EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM FOR THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS.

BY TED MITCHELL AND DERRICK ANDERSON

Higher education finds itself under a harsh spotlight. Politicians accuse colleges and universities of ideological bias, irrelevance, financial irresponsibility and cultural insularity. Abrupt federal funding freezes and threats to international student enrollment are generating fear and lawsuits. Republicans appear now to be the main critics of higher education, but Democrats in years past have also raised plenty of complaints.