BY YUVAL LEVIN

BY FRANK BRUNI

“Intellectual humility allows us to revisit our assumptions.”

BEYOND VICTORY

WRESTLING ICON

CAEL SANDERSON’S COUNTERINTUITIVE SECRET TO SUCCESS. by ethan bauer

BY YUVAL LEVIN

BY FRANK BRUNI

“Intellectual humility allows us to revisit our assumptions.”

WRESTLING ICON

CAEL SANDERSON’S COUNTERINTUITIVE SECRET TO SUCCESS. by ethan bauer

Located 10 minutes from downtown Salt Lake City is a Utah State Park with the perfect venues to set your team up for success all year round! With eleven inspiring, tech enabled spaces, we have the ideal venue to fit your corporate needs. Rooms for breakout gatherings, spaces for over 500, free WiFi, trail rides for team building, a variety of catering options, and free and easily accessible parking. This Is The Place for your business!

Hida is a Japanese-Thai journalist whose work has appeared in The New York Times, National Geographic, and Mastermind Magazine. She is a former staff reporter for the Times in Tokyo, where she covered everything from books to politics to gender. Her story about the kid-friendly island of Tokunoshima, Japan, is on page 30.

Bruni has been a journalist and opinion writer for more than three decades, including more than 25 years at The New York Times. Also a professor at Duke University, he is the author of four New York Times bestsellers. An excerpt from his most recent book, “The Age of Grievance,” is on page 36.

Rzeczy is a Polish artist specializing in editorial illustrations and digital collages. Rzeczy’s work is featured in The New Yorker, Time, The Economist, Vanity Fair, The Washington Post, BBC, The Wall Street Journal, Billboard, Wired and many other publications. Her collage work can be seen on page 46.

Good is director of the Aspen Institute’s Religion & Society Program, helping journalists, policymakers and clerics better understand religious pluralism in America. He has been published in The Hill, National Review, The Weekly Standard, and The American. His essay on technology and isolation is on page 68.

Levin is the director of Social, Cultural, and Constitutional Studies at the American Enterprise Institute. The author of several books on political theory and public policy, an excerpt from his most recent book, “American Covenant: How the Constitution Unified Our Nation and Could Again,” is on page 64.

Arrojo is a freelance illustrator from A Coruña, Spain. His clients in editorial and publishing fields include The New York Times, The Washington Post, El País, Volkswagen and UNICEF. His illustrations have been recognized by the World Illustration Awards, among others. Arrojo’s work can be seen on page 16.

Won’t you be my neighbor?

Early this year, at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., Utah Gov. Spencer Cox and Maryland Gov. Wes Moore encouraged an audience of Republicans and Democrats to improve the civility of their political discourse, especially with those they disagreed with. The two don’t agree on many issues but have struck up an unlikely friendship built on mutual respect. The theme of that event, sponsored by this magazine and Brigham Young University’s Wheatley Institute, was how to disagree better.

That night, speakers across the political spectrum — from ABC’s Donna Brazile, former chair of the Democratic National Committee, to The Atlantic’s Peter Wehner, a former speechwriter for three Republican presidents — spoke on improving civility in public life. This has been a focus for this magazine all year, but I was still surprised to see how a fairly innocuous plea to be polite was used against Cox. One of his political opponents called the initiative “a leftist, Marxist tactic to get people to drop their opinions,” and Cox was roundly booed at the state’s GOP convention. Throughout the campaign season the initiative was mocked, in a state known for its kindness.

I thought about this as I read Frank Bruni’s “Persecution Complex” in this month’s issue, an excerpt from his book, “Age of Grievance.” The New York Times columnist argues that these days, people on both the left and the right feel attacked, even dehumanized, by the other side, and rather than seeking to understand each other — or heaven forbid, realize they might be wrong about a particular issue — they retreat deeper and deeper into their respective echo chambers.

Over the past year, inspired by that night at the National Cathedral,

I’ve made a concerted effort to practice disagreeing better. I’ll be honest, it hasn’t been easy. There are times I’ve felt insulted. At times I’ve been offended at the suggestion I’m blind to my own biases, uneducated or not that intelligent. In my worst moments, I’ve responded in kind. I’ve often left these exchanges feeling like I let my emotions get the best of me.

But disagreeing better, I’ve learned, doesn’t mean we have to compromise our own beliefs or values. It’s OK if we feel some level of frustration with someone who holds an entirely different worldview. And it can put a strain on a relationship.

But we shouldn’t let differences of political ideology end friendships, or worse yet, make us think of our friends and family as enemies. This may sound like hyperbole, but America is a country built on the idea of disagreeing better. That’s because it’s the bedrock of pluralism, the very foundation of a diverse society that draws on the strengths of people of wildly different backgrounds, ethnicities and belief systems.

And here’s one more thing I’ve learned: during a tense political season like the one we’ve just endured, it’s easy to forget our lives are so much bigger than politics. When things have gotten heated, I’ve found I can almost always find common ground on some other topic. And that has reminded me that our political leanings don’t make us who we are.

By the time many of you read this, the voting will be over, or close to it. One side will undoubtedly feel aggrieved, or worse. But regardless of who wins, true friendship and family ties must persist and survive this election. And the next one, too.

—JESSE HYDE

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

HAL BOYD

EDITOR

JESSE HYDE

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

ERIC GILLETT

MANAGING EDITOR MATTHEW BROWN

DEPUTY EDITOR CHAD NIELSEN

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

JAMES R. GARDNER, LAUREN STEELE

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

DOUG WILKS

STAFF WRITERS

ETHAN BAUER, NATALIA GALICZA

WRITER-AT-LARGE

MICHAEL J. MOONEY

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

SAMUEL BENSON, LOIS M. COLLINS, KELSEY DALLAS, JENNIFER GRAHAM, MARIYA MANZHOS, MEG WALTER

ART DIRECTORS

IAN SULLIVAN, BRENNA VATERLAUS

COPY EDITORS

SARAH HARRIS, VALERIE JONES, CHRIS MILLER, HANNAH MURDOCK, TYLER NELSON

DESERET MAGAZINE (ISSN 2537-3693) COPYRIGHT © 2024 BY DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. IS PUBLISHED MONTHLY EXCEPT BI-MONTHLY IN JULY/AUGUST AND JANUARY/FEBRUARY BY THE DESERET NEWS, 55 N 300 W, SUITE 400, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH. TO SUBSCRIBE VISIT PAGES.DESERET.COM/SUBSCRIBE. PERIODICALS POSTAGE IS PAID AT SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH

POSTMASTER: PLEASE SEND ADDRESS CHANGES TO PO BOX 2220, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH 84101.

PUBLISHER BURKE OLSEN

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER ERIC TEEL

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT SALES TRENT EYRE

VICE PRESIDENT MARKETING EMILY HELLEWELL

VICE PRESIDENT SALES SALLY STEED

PRODUCTION MANAGER MEGAN DONIO

DIRECTOR OF CIRCULATION SYLVIA HANSEN

THE DESERET NEWS’ PRINCIPAL OFFICE IS 55 N. 300 WEST, STE 400, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH. COPYRIGHT 2024, DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA.

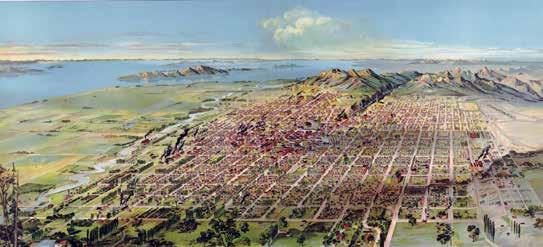

PROPOSED AS A STATE IN 1849, DESERET SPANNED FROM THE SIERRAS IN CALIFORNIA TO THE ROCKIES IN COLORADO, AND FROM THE BORDER OF MEXICO NORTH TO OREGON, IDAHO AND WYOMING. INFORMED BY OUR HERITAGE AND VALUES, DESERET MAGAZINE COVERS THE PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF THAT TERRITORY AND ITS INTERSECTION WITH THE BROADER WORLD.

Our SEPTEMBER education issue featured the views of former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Interfaith America founder Eboo Patel and eight other prominent voices in higher ed on how to make college more accessible and effective (“A Higher Purpose”). Many readers agreed on the value of an education and debated whether today’s campuses embrace expression of opposing political viewpoints. But Thomas Nedreberg pointed out the essays barely touched on affordability, which creates a major obstacle to obtaining a college degree. “All we heard was 10 people who believe in education, which I do as well, but they didn’t say anything useful for someone to actually get an education unless they were born into a rich family.” The rising price of tuition was discussed in a wide-ranging interview Deseret News Executive Editor Doug Wilks had with former Indiana Gov. and Purdue University President Mitch Daniels (“How to Save Higher Ed”). Reader Breck England bemoaned the hyperfocus schools have on preparing students to make a living. “A liberal education is about more than just $$$. It’s about gaining the wisdom of the ages through the study of philosophy, history, literature, the arts, and, yes, critical theory. I fear that higher ed is becoming nothing but a job-training mill.” But Mark Keith, who has worked at several universities around the country, dismissed the demise of higher education as overblown. “Just do your research before picking a university. Use rankings based on the value of the education and not simply the overall ranking. There are PLENTY of very good options out there that deserve respect rather than criticism.” Deseret Magazine staff writer Ethan Bauer revisited BYU’s improbable 1984 college football national championship and asked if it could happen again (“Can Underdogs Win in College Football Today?”). The story won praise from author and national college football writer Ivan Maisel, who tweeted: “Nice piece by Ethan Bauer tying together the 40th anniversary of two seminal events, the @BYUfootball national championship and the Supreme Court ruling opening up the televising of (college football).” Readers were nearly unanimous that such a title run couldn’t occur under the current state of college athletics. Natalia Galicza revealed how African literature gets exposed to an American audience in her profile of the Utah-based online bookstore Iskanchi Press (“The Lion’s Tale”). Marybeth Timmermann, who has translated African literature from French into English for Iskanchi, noted how the story illustrated the “importance of literature and world literature, including literature by African authors, in breaking down stereotypes and broadening people’s understanding and empathy in this great big, fascinating world that we all live in together!”

“They didn’t say anything useful for someone to actually get an education unless they were born into a rich family.”

Huntsman Graduate. Rodeo Queen.

Sales and Trading Analyst. Competition Winner. Woman in Business. Risk Taker.

WHY NATIONAL PROBLEMS ARE BEST SOLVED LOCALLY

BY LIZ JOYNER

Nearly 250 years ago, America kicked its king to the curb, as this new nation began a great experiment with the most ambitious idea that has ever existed on planet Earth: that a diverse people can self-govern. But to live and breathe free, our founders knew we would need to maintain uneasy relationships across “factions.” That’s how you solve problems without a fancy-pants king telling you what to do.

Fast-forward a couple of centuries and the mutual tolerance required to self-govern is rare. From the groups we join to the things we like on Facebook, we design our lives to surround ourselves with like-minded people. With too much time spent in homogenous digital silos and not enough encountering people we disagree with in the real world, we’re losing the ability to see each other clearly or to learn something new, much less solve the complex challenges we face. This problem is big and it is dangerous.

Americans can be forgiven for looking to our national elected leaders to address this fracture in the body politic. But in America, it was never about the king; it has always been about the people. As much as we might wish otherwise, healing our civic rupture has to start in the hometowns we share and in the space between us as we lead our everyday lives. I know this because we’ve seen it in our community.

Formed in Tallahassee, Florida, after a divisive issue left leaders wanting a better way, The Village Square is on a mission to build

civic trust between people who don’t look or think alike. In this local revival of the quintessential American town hall, we’ve had hundreds of conversations with tens of thousands of people. We talk in bars, we talk in churches, we talk across a hundred continuous tables in the middle of a downtown street. Through all this talking, we’ve discovered something truly remarkable: People are hard to hate close-up.

Yet divisive politicians and media figures would have us believe that estrangement from our fellow Americans is inevitable because the differences are so vast that there is simply no reason to communicate directly. We can only hope to vanquish “them.” These conflict profiteers know that when we are locked in mortal battle with each other, their market share grows.

This crisis is driven less by the fact that we disagree (our country was built for disagreement) than by the very distance we’ve allowed to grow between us. We don’t know each other, so we don’t trust each other. And if we don’t trust each other, we’ll believe the worst about each other. Closing that distance changes everything, and no president can do that for us.

Years ago, inspired by The Village Square, my husband sparked a friendship with an acquaintance because of their political disagreements. When you decide to move closer, occasionally you realize you agree. But more often you’re struck with the obvious good intentions of people, even when the difference of opinion is vast. Most importantly, in proximity to each other, humans have a superpower — we reciprocate kindness with kindness. My husband and his friend still disagree, but politics is now about the 20th most important thing about their friendship.

Imagine if most of us felt this way about even just one political “foe”? That’s something within our control. It may sound scary at first, but we’ve been inviting people across the country to “take the dare” to reach out to their political opposite, whether that’s a friend from high school or a neighbor down the street. We’ve found real joy in these new friendships.

Existing communities can encourage these same unlikely relationships at scale — churches can gather with politically dissimilar congregations around mission work and left-leaning groups can partner with right-leaning ones. You can even start a Village Square in your hometown. In a digital age driving us apart, we can become intentional about occasionally coming together. It’s tragic if we don’t at least try.

If we citizens do our part, then the next time politicians hold a finger in the wind — as they are prone to do — they will see that the wind has shifted, and that we no longer wish to live our lives in the toxic binary created by our distance.

Together we can write the next chapter of our history, in our hometowns and with our family, friends and neighbors. In a country of, by and for the people — we shouldn’t have it any other way.

LIZ JOYNER IS THE FOUNDER AND PRESIDENT OF THE VILLAGE SQUARE.

FEWER PEOPLE TRUST the news than ever. Politicians deride it, young adults are bored of it and the rest of the market seems confused by it. Once deemed a common resource for objective reporting on current events, the “fourth estate” has splintered. While local news struggles to stay afloat, national outlets chase disparate audiences and offer competing worldviews. Skepticism may fall on the reporters and anchors who face the public, but the entire industry has evolved, responding to changes in the environment where it operates with new business models and ownership structures. So who owns the news? Here’s the Breakdown.

—NATALIA GALICZA

0% CONFIDENCE

A record-high 39 percent of Americans have no confidence in mass media. Half believe that national news outlets mislead and misinform their audiences to push agendas or chase profits. Ninety-five percent believe corporate interests influence coverage, and nearly three-quarters want news organizations to be more transparent about their funding.

39% 50% 95% 72%

OF AMERICANS HAVE NO CONFIDENCE IN MASS MEDIA

BELIEVE NATIONAL NEWS OUTLETS MISLEAD AUDIENCES

BELIEVE CORPORATE INTERESTS INFLUENCE COVERAGE

WANT TRANSPARENCY IN NEWS ORGANIZATIONS’ FUNDING

That’s the number of conglomerates estimated to control 90 percent of the media — empowered by deregulation of ownership in the Telecommunications Act of

1996 — although measures vary and properties change hands. Several of them own news outlets, including Disney (ABC, ESPN, Vice), Warner Bros.

Discovery (CNN), and Comcast (NBC, CNBC, MSNBC, Telemundo), which earned $121.57 billion in 2023. That’s more than Tesla, IBM or Bank of America.

The Fairness Doctrine required broadcasters to air contrasting opinions on matters of public interest until the bipartisan FCC ended the practice by unanimous vote in 1987. That spawned a vibrant ecosystem of partisan radio talk shows, personified by Rush Limbaugh, which has now largely moved to podcasts. It may have influenced the Sinclair Broadcast Group’s strategy to amass 185 local television stations, reaching 4 in 10 households (Nexstar Media Group, a politically neutral competitor, owns 200). The FCC’s “corollary rules” limited personal attacks and political editorials until 2000.

1 IN 3

That’s how many Americans prefer mainstream and network outlets, like CBS News (owned by Paramount Global, but an ongoing merger will give controlling ownership to tech billionaire Larry Ellison). Others are mostly split between local news, social media and digital-only news sites. On the radio, many are hearing from iHeartMedia, which runs 860 stations in 160 markets, plus a plethora of podcasts that span and sometimes ignore the political spectrum.

1.25 BILLION VISITS

“THE FIRST AMENDMENT … RESTS ON THE ASSUMPTION THAT THE WIDEST POSSIBLE DISSEMINATION OF INFORMATION FROM DIVERSE AND ANTAGONISTIC SOURCES IS ESSENTIAL TO THE WELFARE OF THE PUBLIC, THAT A FREE PRESS IS A CONDITION OF A FREE SOCIETY.”

SUPREME COURT JUSTICE HUGO BLACK, ASSOCIATED PRESS V. UNITED STATES, 326 U.S. 1 (1945)

That’s how often users checked the three leading news websites in July 2024: CNN (525 million), The New York Times (386 million) and Fox News (337 million). Though publicly traded, the Times has been run by the dynastic Ochs-Sulzberger family since Adolph Ochs bought the paper in 1896. Fox News is part of News Corp., along with The Wall Street Journal and the New York Post, operated under the controlling ownership of the Rupert Murdoch family.

40 GOLDEN YEARS

In the later 20th century, newspapers averaged 12 percent profits — some hitting up to 30 percent — with ads fueling 80 percent of revenue. Business hadn’t always been so good. Starting in 1792, the government had subsidized postage to keep the media afloat, up to $35 billion annually in today’s money. But classified ad sales peaked at $19.6 billion in 2000 before crashing by 77 percent in 12 years, undercut by online services like Craigslist. Some news advocates want to bring back government subsidies.

57% OF NEWSPAPERS

Most newspapers are held by seven companies including Gannett, which owns more than 200 dailies, about 175 weeklies and USA Today. Academic studies have found that when conglomerates buy local newsrooms they often condense coverage areas, reduce local content and nationalize stories, cutting resources to maximize profit. One exception is The Washington Post, which Amazon founder Jeff Bezos bought in 2013.

12%

80% $19.6b

AVERAGE PROFIT MARGINS FOR NEWSPAPERS IN THE LATER 20TH CENTURY OF NEWSPAPER REVENUE WAS FROM ADS CLASSIFIED AD SALES IN 2000, BEFORE DROPPING 77% BY 2012

EVERY FOUR YEARS, Americans practice some peculiar math. No other country still uses a system like the Electoral College to select a national executive by indirect vote. It was enshrined in the Constitution as a compromise between letting Congress choose the president and a popular vote — unheard of in 1788. Today, its practical implications hinge on the allocation of electoral votes reflecting the size of each state’s congressional delegation, inherently reducing the impact of major population centers. That’s by design, but the country has grown and evolved over the past two centuries, expanding the vote to include most adult citizens. Is the Electoral College still an essential measure to protect small states and pluralism? Or an anachronism that makes America less democratic?

—ETHAN BAUER

MANY AMERICANS ARE unhappy with the Electoral College, but that’s not new. In the 1960s, civil rights activists saw it as a tool for preserving the old political order they opposed. In 1970, it took a filibuster by Southern senators to kill an overwhelmingly bipartisan constitutional amendment that would have instituted a popular vote, after an uncomfortably close tally in the 1968 election. In 2000 and 2016, this antiquated process delivered presidents who won despite losing the popular vote. No wonder a 2023 Pew poll found that 65 percent favor direct voting.

The Electoral College responded to a question that is now thankfully obsolete: how to represent the enslaved population in Southern states. As Founding Father James Madison put it, “the substitution of electors obviated this difficulty and seemed on the whole to be liable to fewest objections.” Along with the regretful Three-Fifths Compromise, which increased that region’s congressional representation, it gave far more weight to its voters in presidential elections. Today, it has a similar effect for all rural states. In 1790, 95 percent of Americans lived in rural areas. Today, 80 percent live in cities, concentrated in coastal states. One effect is that a vote in sparsely populated Wyoming is worth about four times more than a vote in California. From another perspective, the math gets even worse. According to Stanford sociology professor Doug McAdams, margins of victory in all but six battleground states during the 2012 presidential election rendered 4 in 5 American voters irrelevant — on both sides of the aisle. Sometimes, decisive votes come from just a few counties, which can bring fringe views and extreme positions into the national discourse.

Imagine a baseball game, writes Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne Jr., where a team wins not by scoring the most runs, but by winning the most innings. The absurdity not only fuels those who question the validity of elections, but also discourages participation. What’s the point of voting, after all, if most Americans agree with you, but you still lose? “Although our founders felt we needed a brake against ‘mob rule,’” writes Dan Glickman, former U.S. secretary of agriculture under President Bill Clinton, the Electoral College “is incompatible with our current national credo that every vote counts.”

THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE is a triumph of federalism that has delivered clear mandates and peaceful transitions of power for two centuries. As a buffer between the people and the presidency, it counters demagoguery, cronyism and regional political machines while empowering coalitions and protecting our pluralistic society from the tyranny of the majority. It requires candidates to account for both the many and the few.

Under a popular vote, cities like Los Angeles, New York and Chicago would dominate elections, reshaping policies to their advantage. The apportionment of electoral votes protects smaller states and rural areas from this fate. The rise of swing states like Arizona, Nevada and Pennsylvania may be controversial, but it’s not unhealthy. “Battleground states are not perfect microcosms for America,” says Audrey Perry Martin, an expert in election law and Federalist Society contributor, “but they are much closer than massive population centers.”

No single region has enough electoral votes to secure the presidency, so candidates must build diverse geographic coalitions, which can empower minority voting blocs. Blue-collar workers were instrumental in delivering Michigan in 2016. Latter-day Saint women helped decide Arizona in 2020. This year, Georgia will likely hinge on Black voters who constitute just 30 percent of its population. “By encouraging candidates to build broad coalitions, the Electoral College helps ensure that the interests of minority groups are considered,” Martin says.

One problem this system prevents is the runoff election. When a popular vote is too close to call, or no candidate achieves a 50-percent majority, additional rounds of voting can take some democracies to a precarious place. But here, candidates can obtain clear mandates, even when third parties divide the popular vote, as occurred in 1992. Only once in U.S. history has no candidate reached the threshold of 270 electoral votes required for victory.

Finally, the Electoral College is far more balanced than it appears, even accounting for flaws in its design or dark influences on its origins. For example, while it theoretically favors smaller states, the prevalence of the winner-take-all accounting method means that huge states like Texas or Florida can produce outsized electoral benefits with small changes in the popular vote. They’re not in any danger of being forgotten when small states get their voices heard.

BY JENNIFER GRAHAM

Iam not a dog person,” I said, when my daughter, then five years old, began her campaign for a dog.

At various times in my life, I’ve been a horse person, a cat person, a donkey person and even a hermit-crab person. But amid a rotating cast of family pets, occasionally supplemented by wounded wildlife en route to the animal emergency clinic or the grave, it’s clear I lacked some essential dog-person gene — a gene I’d somehow passed on to my daughter.

In my eyes, dogs seemed the most high-maintenance of animals — requiring walks and flea treatments, training and play dates, and more grooming than I even gave myself.

Undaunted, my daughter checked out books about dog breeds at the library and pored over them. She made lists of how the family would benefit from a dog. (We’d get

more exercise! We’d spend more time outside!) She would take care of him all by herself, she said, and I believed this grand lie, just like every other parent who consents to get a dog for their kid.

JASON READILY ACCEPTED US AS HIS NEW FAMILY, EVEN THOUGH HE’D HAD NO SAY IN THE MATTER.

Although I was not a dog person, I am very much a Katherine person, and so of course, the day eventually arrived when we went, as a family, to pick up Katherine’s dog.

It was a practical — certainly not an emotional — decision, I convinced myself.

It’s been widely reported that more American households have pets than children living at home, which is alarming, but also makes sense. Pets provide order to our days and, more often than not, infuse our lives with humor and joy. Some make us safer, serving as guardians of our household and other animals. (Donkeys and peacocks are famous protectors of livestock.) Nearly all Americans who have pets consider them to be part of their family, Pew Research Center has found, and just over half say they are just as much a part of the family as the humans are.

But while human beings are able to connect with a wide range of animals — some even keep boa constrictors as pets — some animals are easier to connect with than others. Namely, dogs.

Dogs benefit people — and yes, children, to Katherine’s point — in myriad ways.

AT AGE 10, HE KNEW SOMETHING IT TAKES MANY HUMANS A HALFCENTURY TO LEARN: BEING WITH THE PEOPLE YOU LOVE IS HAPPINESS ENOUGH.

Studies have shown that living with a dog improves markers of physical and emotional health. As the authors of one study published in Frontiers in Veterinary Science wrote: “We have seen that interacting with a dog can have stress reducing impacts in the biological realm such as decreased cortisol, heart rate, and blood pressure, and increases in oxytocin. In the psychological realm, stress reduction can be a driver of immediate improvements in self-report measures of stress, mood, and anxiety, and more delayed improvements in overall mental health and quality of life.”

When it came to picking up my daughter’s new pet and imagining all the infernal walks to come, I didn’t feel these studied truths applied to me.

KATHERINE’S DOG WAS a black-and-white border collie whose previous owner had named him Jason because his spots had reminded her of the murderer in the “Friday the 13th” horror movies, which I hadn’t seen, but knew enough of to know that this might not be a good sign. He was already a year old, though, so there was no sense in renaming him. Jason, he would remain.

I’d once bought a horse advertised as the “deal of the year,” which was most definitely not, but Jason was, in fact, a deal, because he was free. He had been the runt of his litter and his owner was happy to finally find him a home where he’d be lavished with love and attention by Katherine and her three siblings. But certainly not me.

In fact, I was so much not enthused about our new pet that a few months into this experiment I decided I’d had enough. This was the second, or maybe it was the seventh, time that Jason escaped the yard or leash and gone gallivanting through the tick-infested woods behind our house. We searched for a panicked half-hour before we caught him, matted and muddy.

The next day, I called the farm and asked if there was anyone else who might want this energetic dog — perhaps someone with sheep that needed herding. There was not. Which was a good thing, because the

moment the question was out of my mouth, I was flooded with uncertainty and guilt, most of which had to do with Katherine, not Jason. But the truth was, for all the trouble he was, the dog had started to burrow into my heart, just a little.

He was accompanying me on runs, for one thing, and I found I kind of liked that. Unlike human companions, he didn’t want to chat and didn’t care about the pace. Faster, slower, an abrupt stop to inspect something by the side of the road … it was all wonderful to Jason. Everything was wonderful to Jason. Sticks. Naps. Puddles. Chipmunks. Hole digging. Ball chasing. Leaf raking. Dinner eating, even when it was the same boring brown kibble night after night.

But most of all, he liked being with his people, and he had readily accepted us as his new family, even though he’d had no say in the matter.

During the day, after the kids went to school, he’d lay down by my desk and quietly lie there while I worked. He would wait with me for the school bus, and his joy was palpable when Katherine disembarked. I’d never seen a horse or a cat look at a person that way: his brown eyes wet and shining, his fluffy tail ticking like a metronome. I will fight anyone who says it wasn’t love I saw in those eyes.

Later, I read that a key difference between wolves and dogs is that dogs look at people’s faces, which seems to explain a lot.

It appeared like all Jason needed in the world was Katherine’s attention.

In truth, people probably need dogs more than dogs need people, a subject that has been explored in the 2021 book “A Dog’s World: Imagining the Lives of Dogs in a World Without Humans” by Jessica Pierce and Marc Bekoff. Pierce, a bioethicist, says that, contrary to how most of us see dogs, about 80 percent of the world’s dogs already live unmoored from human support — free range, as it were.

Visiting Ecuador a few years ago, I was smitten with the homeless dogs that roamed beaches and streets. While many were unkept and a few clearly in need of

veterinary care, they were surviving and some even appeared well fed. (One enjoyed half of my lunch at an open-air cafe.) It’s a fool’s errand to ascribe human emotions to animals, but more than one mutt that I saw trotting purposefully alongside a rural road, free of leashes and other human means of control, looked — dare I say it? — happy.

You can’t say the same about a dog person who, for whatever reason, finds themself without a dog.

IN JASON’S LATER years, he had his own chair, a pale yellow, faux leather recliner we’d gotten from a yard sale. It sometimes took one or two tries to hoist himself onto it, but he’d sit in the recliner and watch us watching TV, like some sort of wizened, wolfish grandfather.

He never seemed to harbor any resentment that we never had sheep, that some essential purpose of his breed, herding, went unrealized. At the age of 10, he knew something it takes many humans a half-century or more to learn: that just being with the people you love, just sitting around on a secondhand recliner that’s seen better days, is happiness enough.

There were times that I yearned for our

pre-Jason life — a time when I didn’t have to factor in a week’s stay at the kennel into the cost of a vacation, a time when I didn’t have guilt knowing how miserable Jason was without us, either in a kennel or at home. The guilt slayed me every time we went away, whether for a day or a week.

Which should have been a clue that I was becoming a dog person.

Yet, I was largely oblivious as the years passed, especially when the kids, one by one, went off to college and the dog chores were left to me during the school year.

I didn’t realize the transformation was complete until the morning we lost him.

He had been slowing down, those wide, sassy hips struggling to make it up the hill near our house on our walks. I’d attributed it to arthritis. But it was likely that the tumor that had been removed 14 months ago had come back, and stoic that he was, Jason had never complained.

On his last night, he slept on the floor outside of Katherine’s room, keeping watch one last time as I slept in her bed. I knew he was sick; he had not eaten the previous day and had not wanted to go on his evening walk. The vet didn’t open until 8:30 a.m. and I planned to take him first

thing, but he passed quietly an hour before, a final heroic courtesy.

I laid on the floor beside his still body, my face in his fur, and sobbed until I had no tears left, a dog person at last.

Do not think, for one moment, that the decision to bring a dog into your family is a casual thing, that the dog will be part of your family’s life for only eight years, or 12, or however long that dog lives.

Matthew Scully, a speechwriter for former President George W. Bush and many other political stars, was a toddler when a dog named Lucky joined his household. Now old enough for senior discounts, Scully still writes tributes and dedicates books to “the memory of my friend Lucky.”

I am here to tell you that yes, one can become a dog person, and it is a violent transition and it will break you and heal you in so many ways, and you will never understand why you care so much about a dog — a dog! — and it will cost so much money and inconvenience you in ways you can’t even imagine, and you will probably lose your security deposit if you rent.

And yes, you should get your kid that dog, anyway.

BY JULIE BROWN DAVIS

Amelia Richmond knocked on the apartment door, squeezing a clipboard under her arm. No one answered. She waited another minute before crossing the patch of dirt to the next door. This time, a woman with glasses and long brown hair opened the door and two small dogs ran outside, barking and circling Richmond’s feet.

“Hi, good evening,” Richmond said. “We’re gathering signatures to get an initiative on the November ballot.”

It was a Tuesday evening in April during one of the first warm weeks of spring, but the air still had enough of a bite that Richmond wore a blue puffy jacket to stay warm while she walked door to door. She was one of 85 volunteers canvassing South Lake Tahoe to get a new tax measure on the ballot.

At first, the woman who lived in the apartment didn’t seem all that interested in signing. “Probably not,” she said, almost shutting the door, but Richmond kept talking. She explained that, in this lakeside California community, 44 percent of the housing units are vacant more than six months out of the year. That adds up to more than 7,000 homes. The petition proposes a

tax on those properties — $3,000 the first year and $6,000 every subsequent year they remain unoccupied. Called a vacancy tax, it would raise up to $34 million a year for housing, road repair and public transit.

“No one that lives here would have to pay it,” Richmond continued. “Just the ones that are empty for more than half the year,

THESE DAYS, LOCALS CAN’T COMPETE WITH OUT-OF-TOWN BUYERS LOOKING FOR SECOND HOMES.

so we can raise more money to build more affordable housing.”

The door stayed open. South Lake Tahoe is like many resort towns in the West, where tourism is the main driver of the economy, and has been for the last century. Today, the Tahoe area sees an estimated 15 million visitors a year. A vast majority of jobs are in the service industry. Half of the city’s residents earn less than $49,000 a year.

With a $655,950 median sales price for single-family homes, locals can’t compete with out-of-town buyers looking for second homes. So, like many mountain resort communities where housing and wages are grossly mismatched, South Lake Tahoe is losing its full-time residents.

“Tourism promises much but delivers only a little,” writes Hal K. Rothman, in his book, “Devil’s Bargains: Tourism in the Twentieth-Century American West,” an authoritative read on the social and economic consequences of tourism that’s just as relevant today as when the book was first published almost 30 years ago, in 1998. In Tahoe, the repercussion has been the hollowing out of the community. “The inherent problem of communities that succeed in attracting so many people is that their very presence destroys the cultural and environmental amenities that made the place special,” he writes.

Today, half of South Lake Tahoe’s workforce lives outside of the Tahoe Basin, in cities across the border in Nevada, trading cheaper housing for longer commutes — especially long in Sierra Nevada blizzards. South Lake Tahoe schools have seen a 35 percent drop

SOME RESIDENTS OF SOUTH LAKE TAHOE, LIKE AMELIA RICHMOND (FRONT) AND NICK SPEAL, SEE TAXES ON SECOND HOMES AS AN OPPORTUNITY TO STRENGTHEN THE COMMUNITY.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JEFF ROSS

LEFT: IN TOWNS ACROSS THE WEST LIKE PARK CITY, UTAH, AND SOUTH LAKE TAHOE, CALIFORNIA, HOUSES THAT SIT EMPTY FOR MORE THAN SIX MONTHS OF THE YEAR ACCOUNT FOR OVER 60 PERCENT OF RESIDENCES.

BELOW: STEVE TESHARA OF SOUTH LAKE TAHOE BELIEVES THAT TAXES AND REGULATIONS ON SECOND HOMES AREN’T THE RIGHT FIX FOR AN INCREASINGLY TIGHT HOUSING MARKET.

in enrollment since the school district’s peak in the 1990s. Meanwhile, across the entire Tahoe Basin, vacation homes take up half to nearly two-thirds of the housing stock, and given Tahoe’s strict environmental regulations, building new housing is not only difficult but expensive.

South Lake Tahoe can’t build its way out of the problem fast enough, Richmond says. The rate of new construction is outpaced by the growth in second-home ownership. This predicament — where local workers can’t find places they can afford to live, yet neighborhoods are dark and empty for most of the year because they are mostly vacation homes — is a common one in the region. In Park City, Utah, 66 percent of the homes are empty six months out of the year or more, according to the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey data in 2022. Compare that to Salt Lake City, one mountain pass and a county line away, which has a vacancy rate of only 5 percent, and it becomes evident how this particular element of the housing crisis isolates itself to small mountain communities that rely on a local workforce. In Aspen, Colorado, 38 percent of homes are empty half of the year or more. It’s about the same ratio in Gunnison County, home to Crested Butte, while to the north, in Sun Valley, Idaho, almost 75 percent of residences are vacant, likely second homes used once or twice a year. That’s comparable to the north shore of Lake Tahoe, about an hour’s drive away from South Lake Tahoe, where about 68 percent of the housing stock are second homes.

“You can’t find a ski town in which this hasn’t been the case, because the incentives are there,” Richmond says. “If you have the capital to come in, buy a property, use it when you want, and ride the property value up, it’s a good deal.”

Richmond believes the vacancy tax would shift the market incentives, unlock much-needed housing for locals and raise money for affordable housing. It’s an idea that’s percolating across the West — Vancouver has one, so does Oakland, Berkeley and San Francisco — though San

Francisco’s Empty Homes Tax is being litigated in court. In Colorado, the state’s association of ski towns, representing 28 municipalities from Telluride to Steamboat, is currently contemplating a tax on empty homes.

Unlike its neighbors in the Tahoe Basin, South Lake Tahoe is incorporated with an elected city council. Here, locals can influence policy with their vote. And in this proposed measure, the tax is structured to offer property owners a clear choice. Stay and live here full time or rent to local residents so the people living in the home are a part of the community, paying sales taxes and enrolling children in local schools. Or, live here part time, use the home occasionally, and pay a vacancy tax that funds housing and transportation solutions that will help

IN SOME TOWNS IN THE WEST, UP TO 75 PERCENT OF HOUSES ARE VACANT, LIKELY SECOND HOMES USED ONCE OR TWICE A YEAR.

Tahoe solve its mounting issues. The last option is to sell.

Richmond held up the clipboard and a pen. “This just gets it on the November ballot so we can vote as a community.”

The woman signed the petition.

BY THE TIME ballot initiative deadlines approached, local volunteers collected enough signatures, and the vacancy tax was added to the November ballot as Measure N. Soon after Measure N was announced, people who own second homes in South Lake Tahoe began to receive a curious letter in the mail that was postmarked from a suburb of San Francisco. The letter outlined steps to mislead election officials and register to vote at the address of their vacation home, which is illegal. One person who received

the letter, however, was a California state assembly member and they tipped off the El Dorado County elections department, alerting them to keep an eye out for any suspicious voter fraud. But the county was already aware — they’d noticed an uptick in false voter registrations for South Lake Tahoe since February. By the first week of June, they’d counted almost 200 questionable forms.

The debate began to appear in the editorial pages of the two local news outlets, like a game of pingpong, going back and forth about the tax’s merits or drawbacks, depending on the perspective of the writer. At a June city council meeting, when staff presented a report analyzing the vacancy tax, public comment stretched for hours into the night. People were angry, emotional. One side shared stories about how impossible it is to find a home they can afford, or even rent. The other side described second homes their families have held onto for generations.

An opposition movement began to coalesce, calling itself “No on Measure N.” A group organized a town hall in August, livestreaming and uploading it to YouTube so people who did not live locally could still watch. In the video, Duane Wallace, the South Tahoe Chamber director, stands in front of a crowded room and speaks into a microphone on a podium.

“Whenever you have this large of a group of people who are in opposition to something, there will be some disagreement,” he said. The opposition was being organized by South Lake Tahoe’s two chambers of commerce, the association of realtors, the lodging association, an influential property owners association for a wealthy lakefront neighborhood, and the restaurant association. In August, the National Association of Realtors contributed $625,000 to the opposition campaign. “But really what the coalition is, is you,” Wallace said, looking out to the audience. “It’s property owners who inherited a property, who had grandparents who built a little cabin up here and whose memories are tied up into this.”

Steve Teshara, director of government relations for the Tahoe Chamber of Commerce, stepped up to the podium to outline the ongoing work to solve the housing crisis. “The hard work of solving housing takes going to meetings, day in, day out, month in, month out, year in, year out. That’s the hard work that they (the proponents) don’t want to do. And that’s the hard work that we do,” Teshara said.

Jerry Bindel of the lodging association outlined the major flaws of the tax, starting with the cost to administer, enforce and legally defend the tax, based on a likely assumption that it would be challenged in court if passed by voters. He also emphasized how a tax like this would invade people’s privacy, requiring everyone — full-time residents, renters and vacation homeowners — to show they were in their home for more than 180 days a year with records to prove it.

Already, word of the vacancy tax is affecting the real estate market, scaring away potential buyers, added Sharon Kerrigan, executive vice president of the South Tahoe Association of Realtors. “We believe that the second homeowners are absolutely integral to the fabric of our community,” Kerrigan told me when I called her after the town hall meeting. “The other side is trying to paint them as not contributing. We disagree.”

Second homeowners pay property taxes, Kerrigan says, though in California, Proposition 13 means that neighbors next door to one another could pay vastly different rates, depending on the value of their property when they bought it. Second homeowners pay utility bills. They go to restaurants, bars and rent kayaks or stand-up paddleboards from concessionaires. They pay into the home building, repair and maintenance cottage industry that’s been propped up for decades in South Tahoe, with everyone from snow removal plow drivers to house cleaners working for people who do not live here all the time.

“Not all these folks are uber-, uber-wealthy,” Kerrigan says. “Sure, we have some of those, but we’re hearing from a lot of people

who are moderate second homeowners, like teachers, firefighters, folks that have had second homes from intergenerational transfer. They might be the third generation that holds it. They might be retired on a fixed income. They might have an 800-square-foot cabin. They don’t have the 5,000-square–foot mansion. They’re all going to be taxed the same.”

Little research exists to show exactly how a vacancy tax would impact a place with so many second homes. Shane Phillips, a housing policy researcher at the Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies at UCLA, says that other vacancy taxes in Washington, D.C., Vancouver or Oakland are all in metropolitan areas with very low vacancy rates, a sharp contrast to a ski town where almost half its homes would be impacted. “All of these places have exceptionally low vacancy rates, like 2 or 3 percent,” Phillips says. “That’s basically just the amount of vacancy you have from people who rent and move pretty frequently, just leaving their unit vacant a month while the landlord seeks the new tenant.”

Even so, only the most punitive policies — like in Vancouver, where the tax is a percentage of the assessed property value, not a flat fee — tend to unlock housing, but these are usually high-cost homes, so even though they’re back on the market, they’re still not within reach for people who need housing the most. What’s more significant, Phillips says, is Vancouver’s ability to raise millions of dollars every year for affordable housing. Since the Empty Homes Tax launched in Vancouver in 2017, $142 million of net tax revenue has been allocated to affordable housing. “In the case of South Lake Tahoe and cities like it, I think the fact that such a large share of units are these kinds of second home, vacation home type places, means it’s hard for me to know or predict what the effect would be.”

WHEN STEVE TANCREDY inherited his grandfather’s log cabin, located less than a mile from the state line in one of South Tahoe’s older neighborhoods, he had to remove

SOME

BELIEVE THAT A VACANCY TAX CAN SHIFT MARKET INCENTIVES, UNLOCK MUCH-NEEDED HOUSING FOR LOCALS AND RAISE MONEY FOR COMMUNITY IMPROVEMENT.

layers and layers of peeling, bubbling paint to restore the wood to its original glory. It’s a 20-by-30-foot cabin, two stories tall, 900 square feet in all. Somehow, it fits three bedrooms and two bathrooms. Tancredy lives in his childhood home in Walnut Creek, but he comes up to his family cabin in Tahoe as much as he can. When he worked the graveyard shift — he splices cables for a communications company — he’d leave from work as soon as he clocked out on Friday morning, with an ATV in the truck bed and jet skis towed behind, getting a head start on the weekend traffic. Over the years, three generations of his family have poured countless weekends and dollars into that little cabin. But it’s getting harder to hold onto it. He was recently dropped from his private homeowner’s insurance company due to wildfire risk and had to sign up for California’s FAIR plan, doubling the amount of insurance he pays every year. Adding another $6,000 tax to the bill on the cabin would crush him, he says. “Nobody’s pay has gone up that much.”

Some ski towns are paying second homeowners to rent long term to locals, as a way to unlock those unused houses. The “Lease to Locals” program started in Truckee during the pandemic and quickly spread to South Lake Tahoe, Mammoth Lakes, as well as municipalities in Colorado, Idaho, Vermont, and even the Massachusetts seaside town of Nantucket. But many second homeowners, including Tancredy, don’t want to rent their houses to strangers. He had two bad experiences with former tenants in the 1980s when his dad owned the cabin. “The neighbor next door at the time, he ended up calling the police because of all the yelling and screaming,” he says. “When we did get it back, the refrigerator door was broken. The oven door was broken. Doors were kicked in. The windows were broken.” That was the last time the Tancredys rented their cabin to long-term tenants. Lately, the thing that’s making Tancredy upset is that people think his house is vacant. “It’s fully furnished. All the utilities

are on. I could relocate up there right now. All I’d have to do is go to the store and load up the cupboards with food. It’s livable right now. To me, vacant sounds like somebody who has an empty cabin and never goes up there.”

Yet, it’s easy to sort the vacation homes from the full-time residences on any given street. When I met Richmond at her home in April, she pointed out the sliding glass door to a large house on the other side of her backyard. Their lights are off most nights, she said. It’s tough to see so many homes go unused when people who are moving to

“WE’RE HEARING FROM A LOT OF PEOPLE WHO ARE TEACHERS, FIREFIGHTERS, FOLKS THAT HAVE SECOND HOMES. THEY MIGHT

BE THE THIRD GENERATION THAT HOLDS IT. THEY MIGHT BE RETIRED ON A FIXED INCOME. THEY MIGHT HAVE AN 800-SQUAREFOOT CABIN. THEY DON’T HAVE THE 5,000-SQUARE-FOOT MANSION. THEY’RE ALL GOING TO BE TAXED THE SAME.”

South Lake Tahoe to work at the hospital, fight wildfires, fix cars and groom ski runs are having such a hard time finding just a place to live.

At a meeting the previous winter, Sierra Riker told the city council about moving to Tahoe in 2021 after joining Americorps to fight wildfires. “Housing was impossible to find on my meager stipend, even with the option of roommates,” Riker said. “I had to rent a small room from someone willing to go far below market value.”

Now, she makes $30 an hour, and still, all the house she can afford is a 450-square-foot

apartment built in the 1950s. “And I am much more fortunate than others,” Riker says. “If I can’t afford more than a tiny rundown one-bedroom apartment, then how is someone making $20 an hour able to live here? Many houses are left empty most of the year and the issue is only getting worse.”

Roderick Martin, a 23-year-old mechanic, says the same thing. “No one can afford to live here,” he told the city council. “I can confidently say that if something doesn’t change, there will be no more population of young people in South Lake Tahoe.”

Teshara, of the Tahoe Chamber, doesn’t deny Tahoe’s housing challenges. He experienced the volatile real estate market during the pandemic firsthand — selling his house and receiving cash offers, which he turned down to sell to a local family instead, and then getting outbid when he was looking for a new house. “We scraped every coin we had, we put down an offer, and it wasn’t enough. Somebody comes in and says, ‘Hey, here’s my offer,’ and we were just out of luck. That was hard. It was very frustrating.”

Charging a flat tax on second homes isn’t the answer to Tahoe’s housing crisis, Teshara adds. “What we do about it is we go to city council meetings. … We go to county meetings. We try to advocate for different types of affordable housing.”

Yet, even Teshara admits that policy work moves slowly — too slow for people frustrated with decision-makers and leaders for talking too much and not taking action to stop the bleeding. In 2018, South Lake Tahoe voters banned short-term rentals. Teshara thinks it was an extreme response that stifled local businesses. The controversial measure passed by just 58 votes. “By the time the city woke up and tried to do something, it was too late,” Teshara says. He’s motivated to not let a repeat scenario play out with Measure N. “It’s not a patient world, and solutions take time.”

Though, when rent is due at the end of the month, time is not a luxury that people have.

BY HIKARI HIDA

It was over two decades ago when Yuki Matsuoka first set foot on Tokunoshima, a subtropical island that rises gently from the cerulean waters of the East China Sea.

Located 800 miles southwest of Japan’s capital, the island’s lush landscapes and the soothing rhythms of the waves quickly captured her heart. But it wasn’t just the natural beauty that drew her to this remote corner of Japan; it was something she had learned, something she hadn’t expected.

“I was used to the idea that two children were plenty,” Matsuoka, who was living in Tokyo at the time, recalls with a laugh. “But here, three or four is normal. Six or seven? Not uncommon at all.”

Matsuoka moved to Tokunoshima two years later to give birth to her first child, a daughter.

Tokunoshima stands as a quiet anomaly in Japan, a country that has long grappled with one of the world’s lowest birth rates.

With a fertility rate of just 1.37 — compared to 1.70 in the United States — Japan faces a demographic challenge that’s common across many developed nations, where replacement-level fertility of 2.1

TOKUNOSHIMA FEELS LESS LIKE A FANTASY AND MORE LIKE A GLIMPSE INTO THE HEART OF A PLACE THAT PUTS ITS FUTURE IN THE HANDS OF THE NEXT GENERATION.

children per woman is increasingly elusive. The global trend toward smaller families is driven by economic pressures like rising living and housing costs, as well as social shifts such as expanded access to education

and career opportunities for women, which delay marriage and childbearing. Since the 1960s, fertility rates have plummeted from a high of 5.02 to 2.2 in 2021, with projections anticipating a drop to 1.59 by 2100.

While the rest of Japan — and much of the world — wrestles with the challenges of an aging population and shrinking families, this small island, just 95 square miles with a population barely exceeding 21,000, has become a cradle of life. Here, the birth rate soars to 2.25, almost double the national average. Walk around, and you’ll hear the sounds of children playing freely until nightfall.

AS THE PLANE descends toward Tokunoshima, emblazoned across the terminal building, a singular phrase comes into view: "Tokunoshima Kodakara Kuko" — the children's airport. It’s an unusual greeting, but one that speaks volumes about what the island most cherishes.

LEFT:

TOKUNOSHIMA’S ECONOMY IS BUILT UPON AGRICULTURE, AND LIVESTOCK — ESPECIALLY BULLS — ARE ECONOMICALLY AND CULTURALLY IMPORTANT TO LOCAL FAMILIES.

BELOW: “KIDS ARE BORN INTO SAFETY HERE — PARENTS WORRY LESS,” SAYS SHINOBU YOSHIDA, THE DIRECTOR OF HEALTH PROMOTION AT TOKUNOSHIMA TOWN HALL.

Located in Kagoshima Prefecture, just an hour’s flight from the mainland city of Kagoshima, Tokunoshima lies between Okinawa to the south and Amami Ōshima to the north.

The name, shortened to “Kodakara,” was coined in 2012, on the 50th anniversary of the island’s airport. The image it conjures — children laughing and running along the sandy beaches of its three small towns — feels less like a fantasy and more like a glimpse into the heart of a community

that places its future in the hands of the next generation.

Despite its idyllic image, Tokunoshima is not a place of material wealth. The island’s economy is built upon traditional industries such as fishing and sugar cane production — hardly the kind of economic engines that generate prosperity in the modern world. Yet, in Japan’s annual birth rate surveys, the towns of Tokunoshima consistently rank among the highest in the nation. It’s an anomaly that defies easy explanation.

Sonny Bardot, a Ph.D. graduate of International Christian University, spent six months on Tokunoshima writing his thesis on the island’s dating culture. He recalls one conversation that encapsulates the community’s unique pressures. A woman confided about the expectations placed on her by both her parents and the wider community to have more children.

“Women often told me that after three children, it’s basically the same,” Bardot explains. The community’s perspective is that once a family has several children, the older siblings naturally take on caregiving roles for the younger ones. “There’s no additional work between three to six kids.”

Understanding this positive perception of large families requires a look at the islanders’ deep connection to their home. In a recent local government survey, 95.5 percent of respondents expressed a strong sense of pride in being from Tokunoshima. According to Matsuoka, traditions play a pivotal role in this shared pride. “There are customs here that people ‘remember deeply’ from childhood, and they’re incredibly important.”

One such tradition occurs at key moments in a child’s life: one month after birth, upon entering elementary school, and again at 20 — the official age of adulthood in Japan.

Attended by nearly 100 guests, the host family prepares a feast including mochi rice cakes, and goodie bags filled with treats, in exchange for modest monetary gifts. Matsuoka, who experienced this tradition 18 years ago when her oldest daughter was celebrated shortly after she had moved to the island, remembers the exhaustion of the preparations, but also the overwhelming warmth. “The kids who experience that feel like they are truly welcomed by the community,” she reflects. “When you reach adulthood, you find yourself wanting your own children to go through the same wonderful experiences.”

FOR FAMILIES ON Tokunoshima, community support is crucial, especially given the financial burdens that they may face.

With local wages often less than half of that in Tokyo, the island’s economic realities necessitate a collective approach to raising families.

“Here, if everyone else is out working the fields, sitting at home just isn’t an option,” Matsuoka explains. Yet, “there are always

“EVERYONE HAS THE NANTOKA NARU,” OR “IT WILL WORK OUT SOMEHOW” MINDSET.

‘hands’ to help and ‘eyes’ to watch over the children,” says Shinobu Yoshida, the director of health promotion at Tokunoshima Town Hall. “Kids are born into safety here, parents worry less.”

Before thinking about money, “everyone has the nantoka naru mindset,” or the

“it will work out somehow” mindset, says Tomokazu Hiro, head of the Care and Welfare Division at Tokunoshima Town Hall, due to all the surrounding support.

In contrast to urban centers like Tokyo and Osaka, the three towns on Tokunoshima, despite their differing governmental approaches, are widely regarded as child-friendly. For instance, out of the eight elementary schools in Isen Town, four are considered small schools, with fewer than 20 students each. According to the Ministry of Education’s guidelines, these numbers should justify reducing the town’s elementary schools to just three. But the town’s mayor, Akira Okubo, who has served for six terms, made a bold declaration a decade ago: No schools would be closed on his watch. Even when one school faced closure with only 11 students, Mayor Okubo chose instead to construct public housing nearby, attracting families with children and thus revitalizing the student population.

IN A RECENT SURVEY, 95.5 PERCENT OF RESPONDENTS EXPRESSED A STRONG SENSE OF PRIDE IN BEING FROM TOKUNOSHIMA. TRADITIONS PLAY A PIVOTAL ROLE IN THIS PRIDE.

This strategy has paid off, not just in keeping schools open but in drawing back those who once left the island. Many young people leave Tokunoshima after high school to pursue further education or employment elsewhere. However, the construction of new public housing has sparked an increase in “U-turn” migration — where individuals return to their hometowns after spending time away. Some towns on the island offer scholarships of around 50,000 yen ($350) per month for students in fields like health care and caretaking, effectively making their education free if they return to work on the island for five years.

But government officials on the island are quick to downplay any notion that they are doing anything extraordinary to boost fertility rates. “We were already No. 1 in Japan before a lot of these subsidies,” Hiro says, adding, “I think we try to listen to the people and that is what makes good results.” In some towns, services such as school lunches and medical care for children up to middle school are provided free of charge. Nursery schools, which are notoriously difficult to access in metropolitan areas like Tokyo, are not only readily

available on the island but are either free or offered at a low cost.

One of the most significant supports for women on the island may be the financial assistance provided for in vitro fertilization. Last year, 12 women in Tokunoshima Town alone benefited from this subsidy, which even covers travel costs to Kagoshima City for those who prefer not to be seen in local clinics.

But when asked why they have so many children, island residents rarely cite these government initiatives. As one woman put it, no financial incentive — certainly not half a million yen — is enough to have a sixth, seventh or even a second child if you don’t genuinely want one.

UNLIKE MUCH OF Japan, where marriage and childbearing are increasingly delayed, on this island, the norm is for women to marry and start families at a young age.

In fact, 45 percent of women between the ages of 20 and 24 are married, a stark contrast to the mere 7 percent nationwide. This early marriage rate is closely tied to Japan’s broader social expectation that children are born within wedlock — only 2 percent of children in Japan are born outside of marriage.

While dekikon — marriage due to pregnancy — is often stigmatized in other parts of Japan, nearly all marriages on Tokunoshima begin this way, according to Bardot’s research. Here, dekikon is seen differently. Rather than being viewed negatively, it often represents a natural progression in relationships, deeply integrated into the local culture.

Divorce, too, is approached differently. The island has a much higher divorce rate compared to the rest of Japan, but this hasn’t led to societal ostracism. The community is notably accepting of single mothers and blended families.

Bardot shares a poignant example of this cultural flexibility, recounting the story of a 28-year-old woman who had her first child at 18, only to divorce shortly after. When she later met another man, she carefully

considered whether he would accept and care for her child from her previous relationship. After confirming his commitment, they started a family together, with the new husband becoming the child’s father in every sense. Such stories are not uncommon on the island, where the “Tsurigo system” allows children from previous marriages to seamlessly integrate into new family units.

Matsuoka, the transplant from Tokyo, emphasizes that while the island has its taboos, people here are generally logical and straightforward when it comes to marriage and divorce. Unlike in many parts of Japan, where single parents often face social stigma — she herself is a single parent — Tokunoshima’s community is more accepting, she says.

This approach to relationships reflects the island’s broader social dynamics, where community support and a focus on well-being take precedence. Japan has the oldest population in the world, with almost 30 percent of its population aged 65 and older. Tokunoshima mirrors this trend. However, unlike many parts of Japan where policies overwhelmingly focus on the aging population, this island has shifted its attention toward nurturing the next generation.

In Isen Town, a longstanding tradition involved giving celebration gifts to elderly residents aged 85 and older. The budget for this initiative stood at around seven million yen ($49,000) annually. However, several years ago, during a community meeting, a surprising request emerged from the elderly residents themselves: We don’t need the

celebration money anymore, so could you allocate that money to the younger generation instead?

This request, which faced almost no opposition, led to a significant policy shift. Starting in 2012, the funds that were freed up were redirected toward child-rearing initiatives.

Since towns on the island were declared as having the No. 1 birth rate in the country, NGO leaders, politicians and sociologists have visited in hopes of catching a note of the baby fever. However, most leave the island “disappointed,” says Matsuoka. “It’s not a casual culture that could be built somewhere else; it’s something deeply ingrained in the life here,” she says. “We don’t just possess some secret here that you can take home and emulate.”

BY Frank Bruni ILLUSTRATION BY Virginia Mori

At the start of every semester, on the first day of every course, I confess to certain passions and quirks and tell them to be ready: I’m a stickler for correct grammar, spelling and the like, so if they don’t have it in them to care about and patrol for such errors, they probably won’t end up with the grade they’re after.

I want to hear everyone’s voice — I tell them that, too — but I don’t want to hear anybody’s voice so often and so loudly that the other voices don’t have a chance. And I’m going to repeat one phrase more often than any other: “It’s complicated.” They’ll become familiar with that. They may even become bored with it. I’ll sometimes say it when we’re discussing the roots and branches of a social ill, the motivations of public (and private) actors, and a whole lot else, and that’s because I’m standing before them not as an ambassador of certainty or a font of unassailable verities but as an emissary of doubt. I want to give them intelligent questions, not final answers. I want to teach them how much they have to learn — and how much they will always have to learn.

I’d been delivering that spiel at Duke for more than two years before I realized that each component of it was about the same quality: humility. The grammar-and-spelling bit was about surrendering to an established and easily understood way of doing things that eschewed wild individualism in favor of a common mode of communication. It showed respect for tradition, which is a force that binds us, a folding of the self into a greater whole. The voices bit — well, that’s obvious. It’s a reminder that we share the stages of our communities, our countries, our worlds, with many other actors, and should thus conduct ourselves in a manner that recognizes that. And “it’s complicated” is a bulwark against arrogance, absolutism, purity, zeal. I’d also been delivering that spiel for more than two years before I realized that humility is the antidote to grievance.

The January 6 insurrectionists were delusional, frenzied, savage. Above all, they were unhumble. They decided that they held the truth, no matter all the evidence to the contrary. They couldn’t accept that their preference for one presidential candidate over another could possibly put them in the minority — or perhaps a few of them just reasoned that if it did, then everybody else was too misguided to matter.

They elevated how they viewed the world and what they wanted over tradition, institutional stability, law, order.

Party leaders who consent to end gerrymandering are being humble about what they can and can’t predict about their future dominance and humble in their exercise of power. They’re recognizing that there are issues bigger than the magnitude of their present spoils. Politicians who reexamine the necessity of college degrees are humbly compensating for our tendencies to extrapolate from our own backgrounds and success stories to what works best in the broad and diverse world beyond us. And people who attend bridge-building exercises, whether in the halls of Congress or the hills of Appalachia, are humbly making an extra effort to understand strangers with whom they don’t usually meet and humbly accepting that civic repair is worth a personal investment of time and energy.

They’re the antonyms of the insurrectionists.

humility comes up often in Jonathan Rauch’s superb 2021 book “The Constitution of Knowledge,” a contemplation of truth and exhortation for free speech in the age of grievance. Rauch, a scholar at the Brookings Institution, defines the term in his book’s title as a global network of “reality-based institutions” — universities, reputable media outlets, courts of law, scientific organizations — that are committed to finding truth through a structured process of conflict and debate. They are “liberalism’s epistemic operating system: our social rules for turning disagreement into knowledge,” Rauch wrote, noting that the defense of the reality-based world against a rising tide of purposeful disinformation and a sea of trolls is a constant struggle. It demands much of us, including, perhaps most importantly, intellectual humility, or what he calls “fallibilism” — the ethos that any one

“It’s complicated” is a bulwark against arrogance, absolutism, purity, zeal.

of us might be wrong, and we must therefore keep ourselves open to contradictory views and evidence.

“Being open to criticism requires humility and forbearance and toleration,” Rauch explained. “Scientists, journalists, lawyers, and intelligence analysts all accept fallibilism and empiricism in principle, even when they behave pigheadedly (as happens with humans).”

Scientific findings can be replicated or refuted by new experiments; laws can be challenged through freshly discovered evidence and refined arguments; journalists ideally keep digging toward a deeper and more nuanced comprehension of events. That’s the nature of the Constitution of Knowledge. It’s a shared endeavor, an evolving quasi document, its nature an acknowledgment that no one person holds all the answers or cards, its health and growth dependent on most people accepting that.

People who attend bridge-building exercises, whether in the halls of Congress or the hills of Appalachia, are humbly making an extra effort to understand strangers with whom they don’t usually meet.

Intellectual humility allows us to revisit our assumptions, and the necessity of that is proven by how often we’ve been wrong or wrongheaded. Scientific racism was a rage in progressive circles in the early 1900s; in the 1990s, the global march of democracy looked inevitable to much of the political establishment, a thinking emblemized in Francis Fukuyama’s premature elegy to history. On both fronts, we know better now, and we know better because we weren’t arrogantly stuck in our thinking.

To be grounded in truth is, paradoxically, to remain open to the idea that the understanding of truth may need to shift as we learn more and as some of those lessons lay bare our prejudice and ignorance. “You must assume your own and everyone else’s fallibility and you must hunt for your own and others’ errors, even if you are confident you are right,” Rauch wrote.

“Otherwise, you are not reality-based.” His “you” is a universal one, a caution and a summons to various stakeholders.

Charlie Baker served as governor of Massachusetts from 2015 to 2023, and was consistently ranked one of the most popular governors in the nation, despite being a Republican in a blue state. Something else about him has always piqued my curiosity and drawn my attention, and perhaps it’s entwined with that popularity: He repeatedly stresses the importance of humility in an effective leader. He’s fond of quoting Philippians 2:3; he invoked it as a lodestar for his administration. “Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit,” it says. “Rather, in humility value others above yourself.”

That’s great practical advice for anyone in government, where almost everything is teamwork, almost everything is consensus, and almost nothing of real and lasting consequence is accomplished alone. Governing, as opposed to demagoguery, is about earning others’ trust, commitment and cooperation. Exhibiting an interest and a willingness to listen to and to hear them goes a long way toward that. It’s a demonstration of humility.

“Insight and knowledge come from curiosity and humility,” Baker wrote in a 2022 book, “Results,” whose co-author was his chief of staff, Steve Kadish, a Democrat. “Snap judgments — about people or ideas — are fueled by arrogance and conceit. They create blind spots and missed opportunities. Good ideas and interesting ways to accomplish goals in public life exist all over the place if you have the will, the curiosity, and the humility to find them.”

Humility was also something that Bill Haslam, the former two-term governor of Tennessee, extolled. He’s a Republican

who ran a predominantly Republican state, so humility wasn’t an attribute that aided a necessary appeal across the partisan divide. But he deemed it essential to making the changes in Tennesseans’ lives that he’d pledged to make — to avoiding any prideful attachment to his first-blush ideas and a schedule of glitzy appearances and cable news interviews that would have detracted from problem-solving. And he indeed amassed a record of substantive accomplishment that was impressive in its heft and its occasional deviations from conservative orthodoxy. He made community college free for Tennesseans. He cut taxes on food while raising them on gasoline. He vetoed culture-war distractions such as a bill to make the Bible the official state book of Tennessee. A few years after leaving office in early 2019, he wrote a reflection on leadership, “Humble Leadership? Yes, and Humility Can Restore Trust,” for The Catalyst, a journal published by the Bush Institute. “Humble leaders who can admit fault are key to uniting a nation,” read an italicized precede to his essay. Haslam’s opening line: “It has been said that those who seek the high road of humility in politics will never run into a traffic jam.” His closing one: “And think how much better served we are by leaders who have the humility to want to get the best answer, not just their own answer.”

Humble politicians don’t insist on one-size-fits-all answers when those aren’t necessary as a matter of basic rights and fundamental justice, and in a society like ours now, when there’s scant trust between partisans and when resentment toward political opponents runs high, both parties should consider devolving power to the state and local levels when possible. Republicans have traditionally supported that in theory and then routinely contradicted themselves, in an unhumble fashion, when that suited them. They should do better at living their stated principles about local control, and Democrats shouldn’t be so quick to assume that local control equals a reckless opportunity to

wriggle free from federal safeguards. In some of the blue cities within red or purple states, local control would mean more respect and freedom for aggrieved people whose progressive ideals are squashed at the statehouse (just as it would mean more respect and freedom for the aggrieved rural denizens of blue states).

In my home state of North Carolina, where Republicans have maintained a big majority (and sometimes contrived a supermajority) in both chambers of the state Legislature through gerrymandered districts, they’ve prevented local officials in places such as Durham from enacting the sorts of gun safety and environmental measures that an overwhelming majority of the city’s hundreds of thousands of citizens want. To what end? The preemption of local laws by broad state edicts has been on the rise in recent years, and it’s a trend that intensifies grievances.

In late April 2018, then-President Donald Trump traveled to Michigan for a rally, where his remarks were a mash of favorite themes. He bragged about what a fabulous job he was doing. He bellyached about all the injustices he endured. And he bashed the news media. Oh, how he loved to bash the news media.

“Very dishonest,” he said. “They don’t have sources. The sources don’t exist.”

While he was painting this unflattering portrait of us, what image were we projecting? That night, at the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner, journalists swanned into a ballroom as thick with self-regard as any Academy Awards ceremony. They hobnobbed with the Hollywood stars whom they’d invited — and in some

Intellectual humility allows us to revisit our assumptions, and the necessity of that is proven by how often we’ve been wrong or wrongheaded.