deseret.com $4.95 JUNE 2024 VOL 04 | NO 35 DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE JANUARY JUNE NOVEMBER MARCH JULY DECEMBER APRIL SEPTEMBER MAY OCTOBER

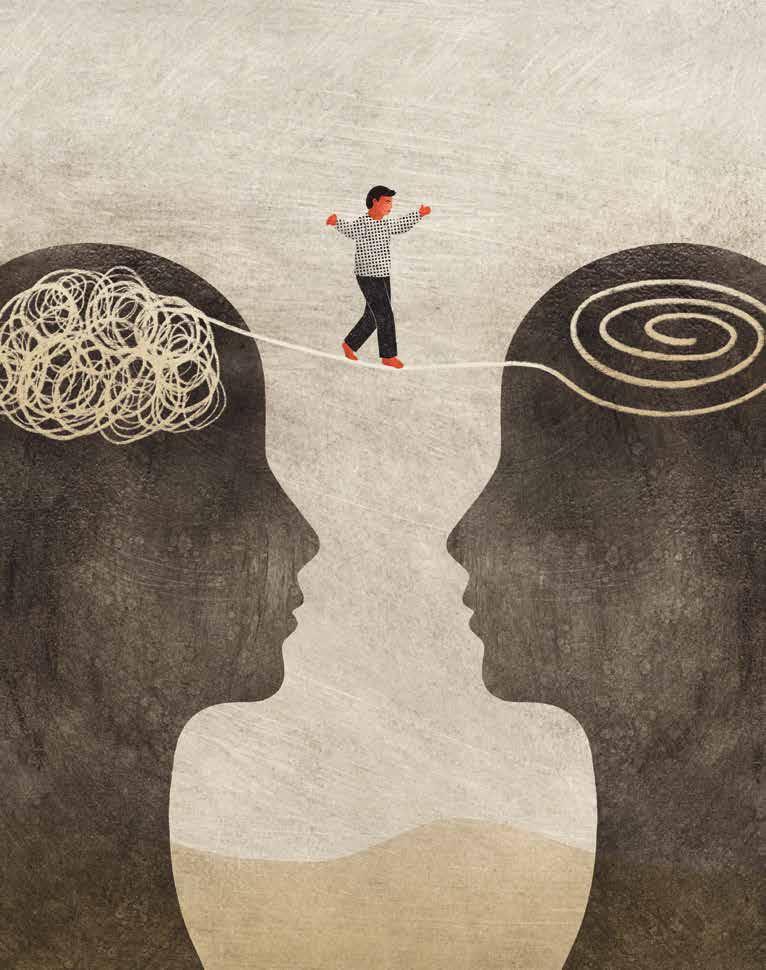

THERAPY

THE TEEN

PLUS:

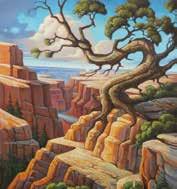

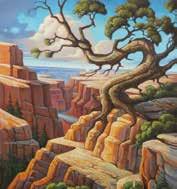

RETURN OF THE CONDOR: THE COMEBACK OF A WESTERN ICON IS

CAUSING

ANXIETY CRISIS?

ALAN J. HAWKINS CONFESSIONS OF A BORN-AGAIN TRAVELER

SOLITARY CONFINEMENT: A UNIQUELY AMERICAN PHENOMENON

You have ideas. You have dreams. You just need a little help putting them into action. Fortunately, Utah is the startup capital of the world. Here, you’ll nd resources to elevate your small business to great heights. Now, let’s get started.

natalia galicza

natalia galicza

“Incarcerated people who endure solitary confinement are 15 percent more likely to reoffend.”

RAPTOR’S RISE FROM THE BRINK OF EXTINCTION.

marlowe starling

JUNE 2024 3 46

THE

CONSIDER

CONDOR A

THE

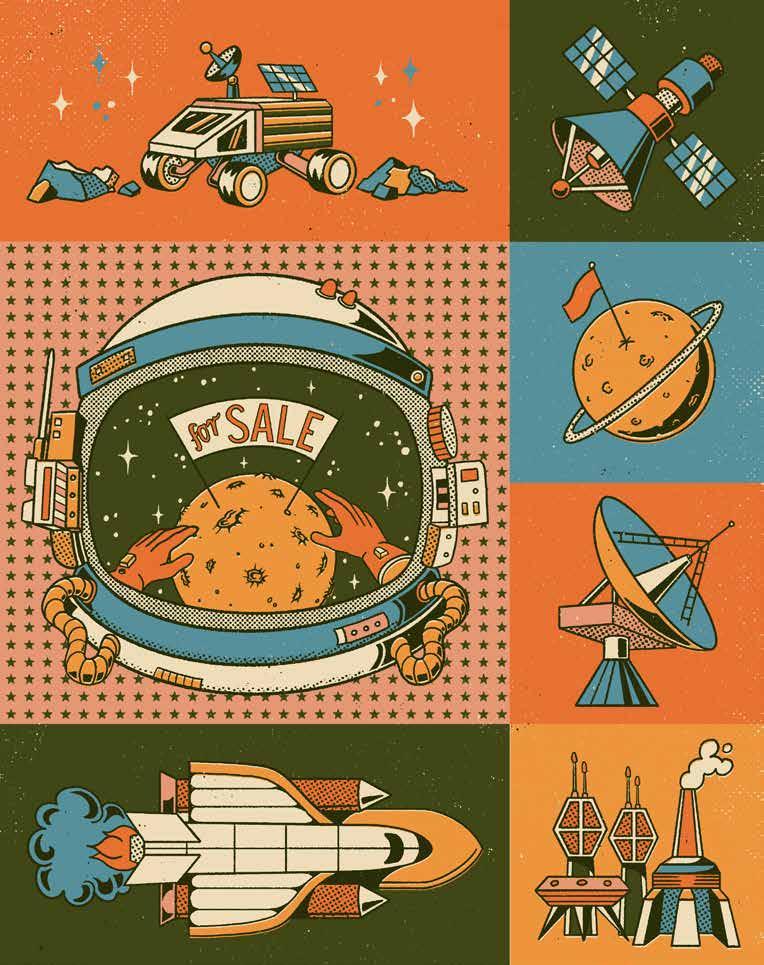

ON THE COVER ILLUSTRATION BY OWEN DAVEY CONFINEMENT: 54

CONTENTS

by

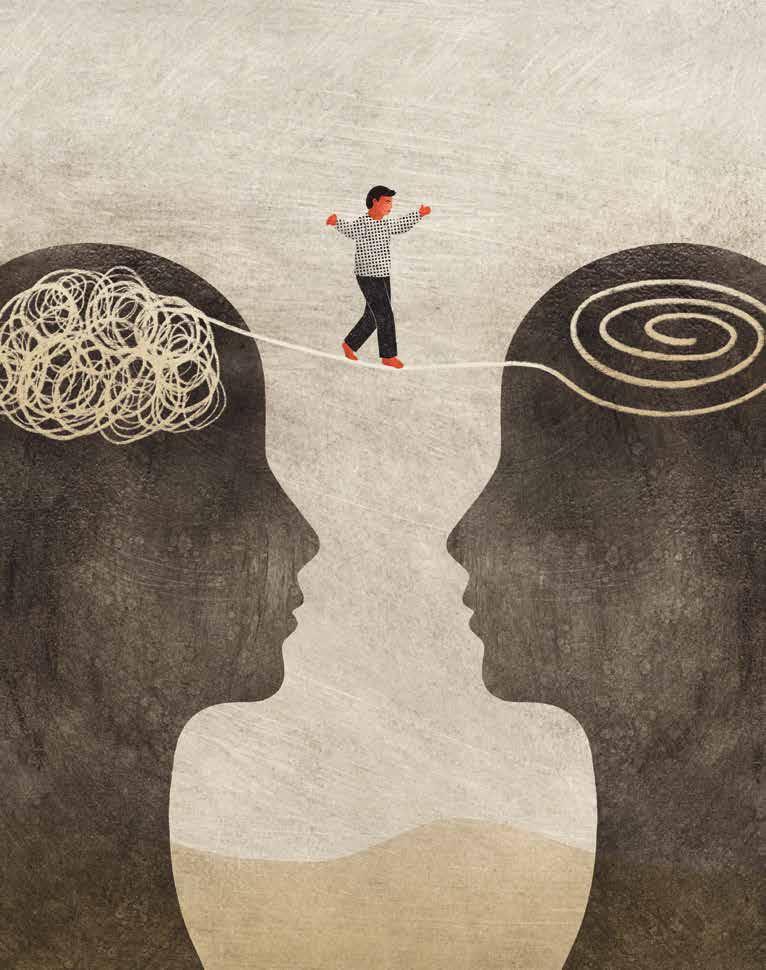

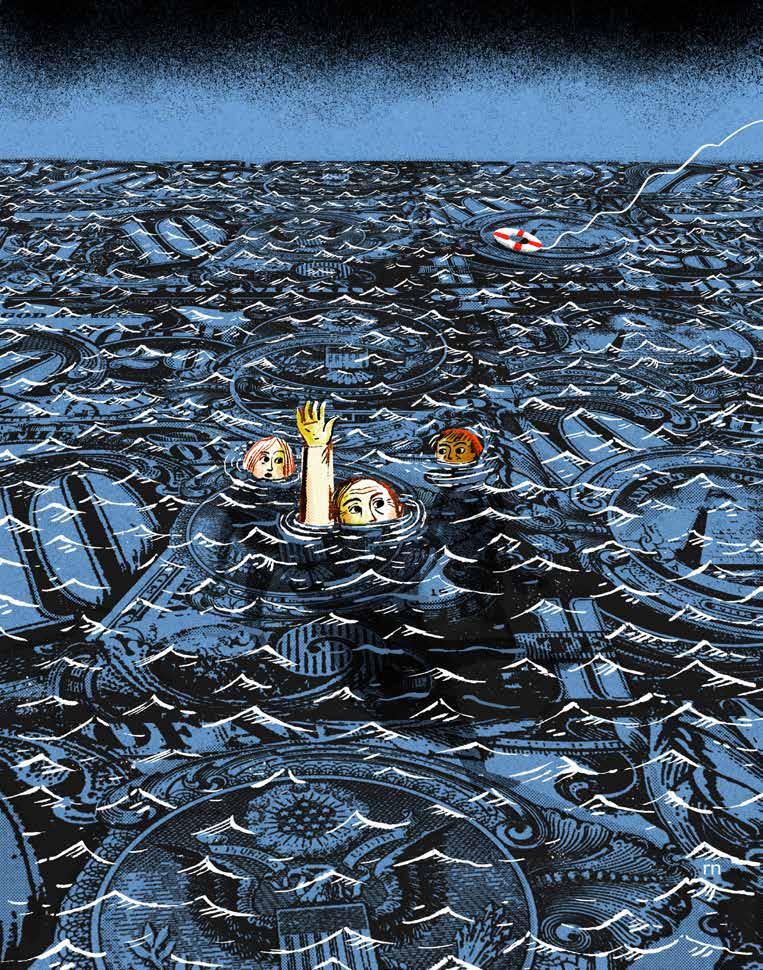

38 ARE THE KIDS ALL RIGHT?

NEW DEBATE OVER THERAPY. by jean m . twenge

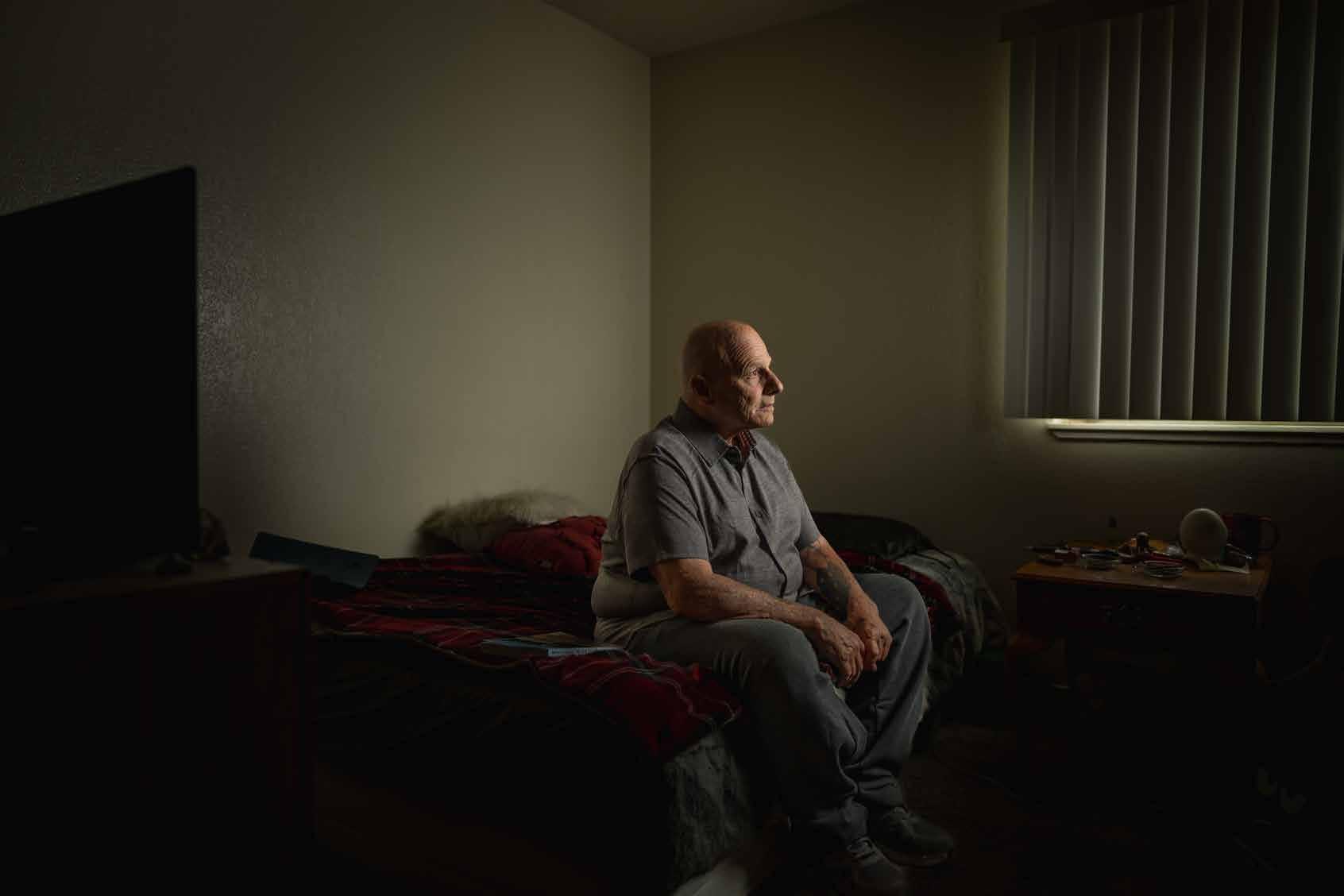

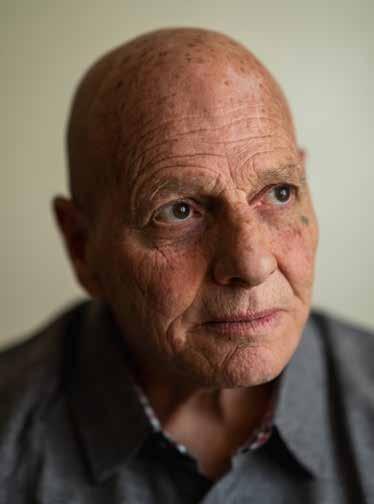

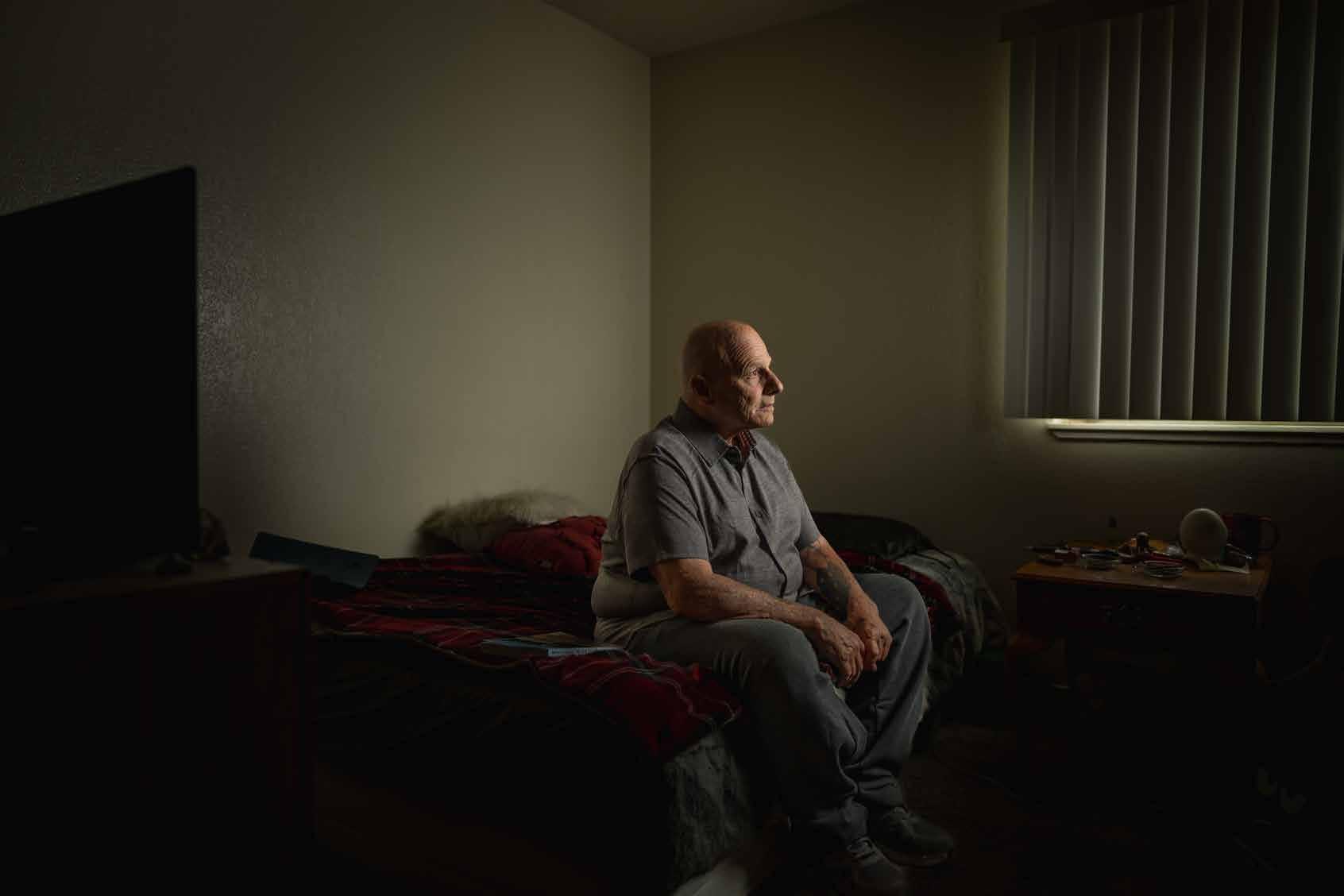

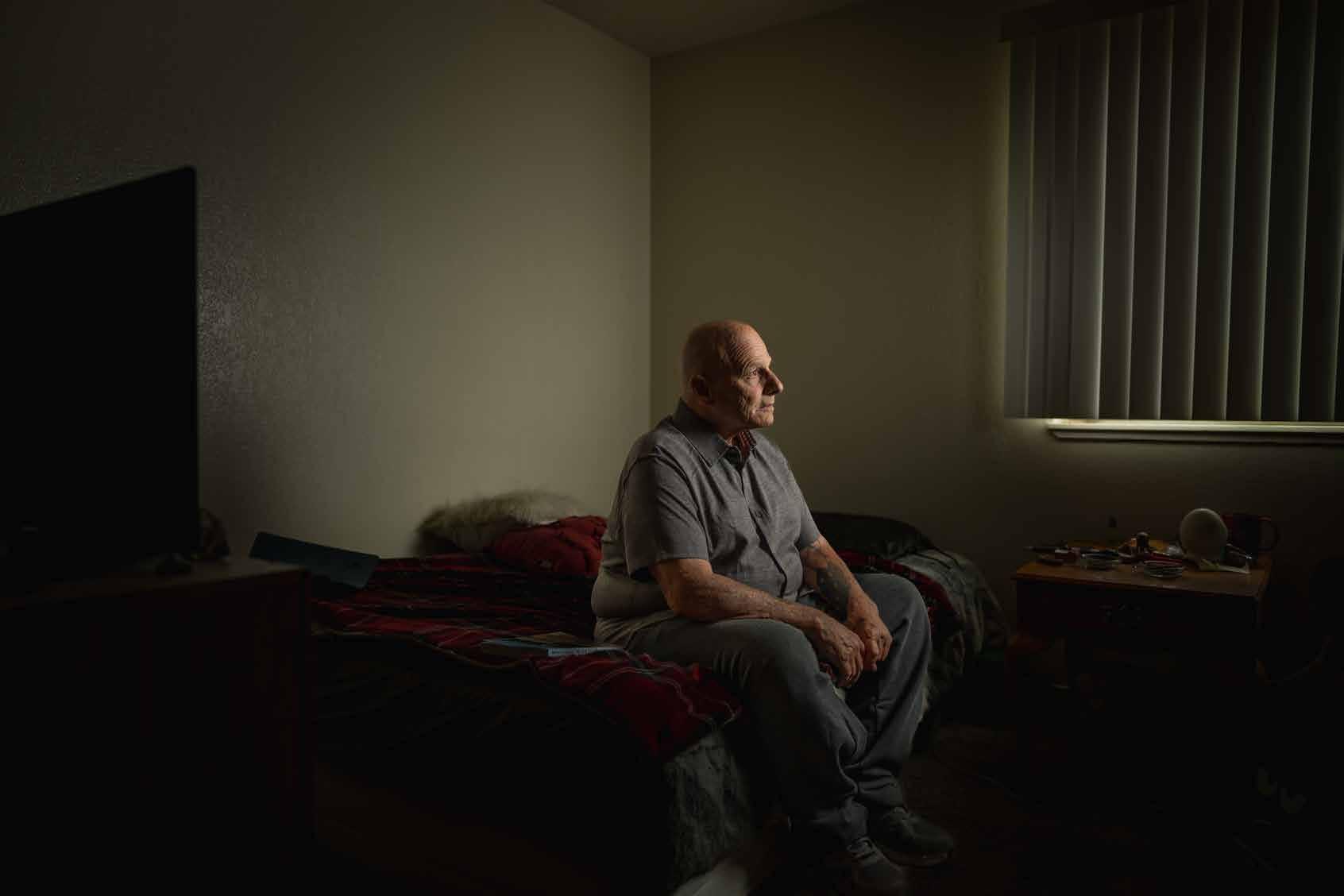

ALONE WHAT 22 YEARS IN SOLITARY CONFINEMENT DOES TO A PERSON. by

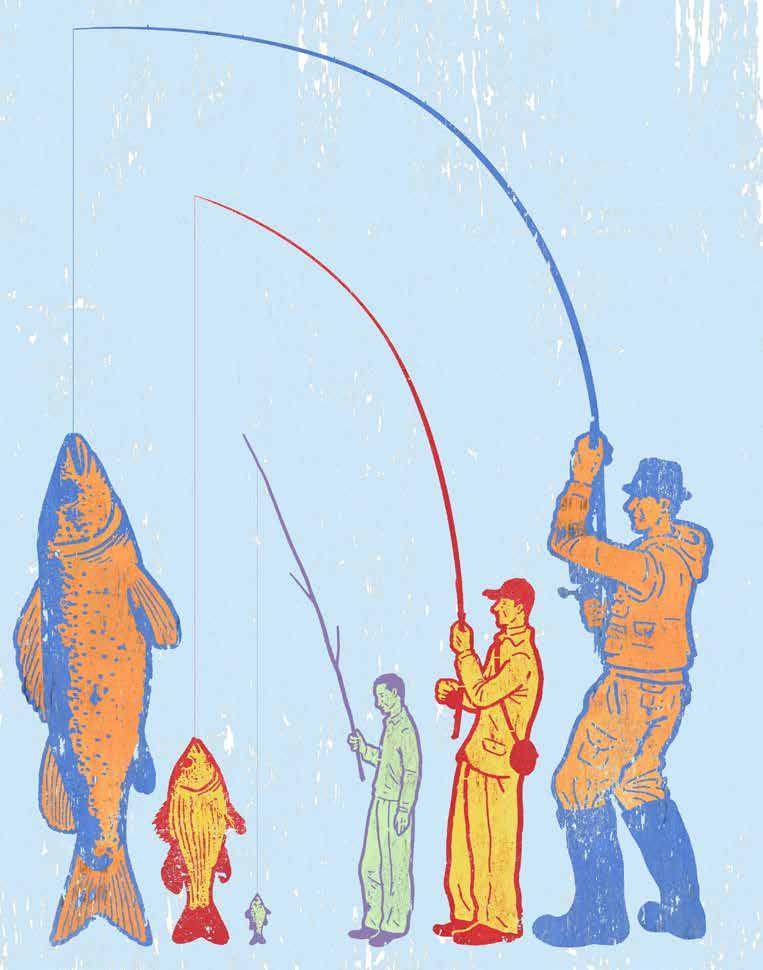

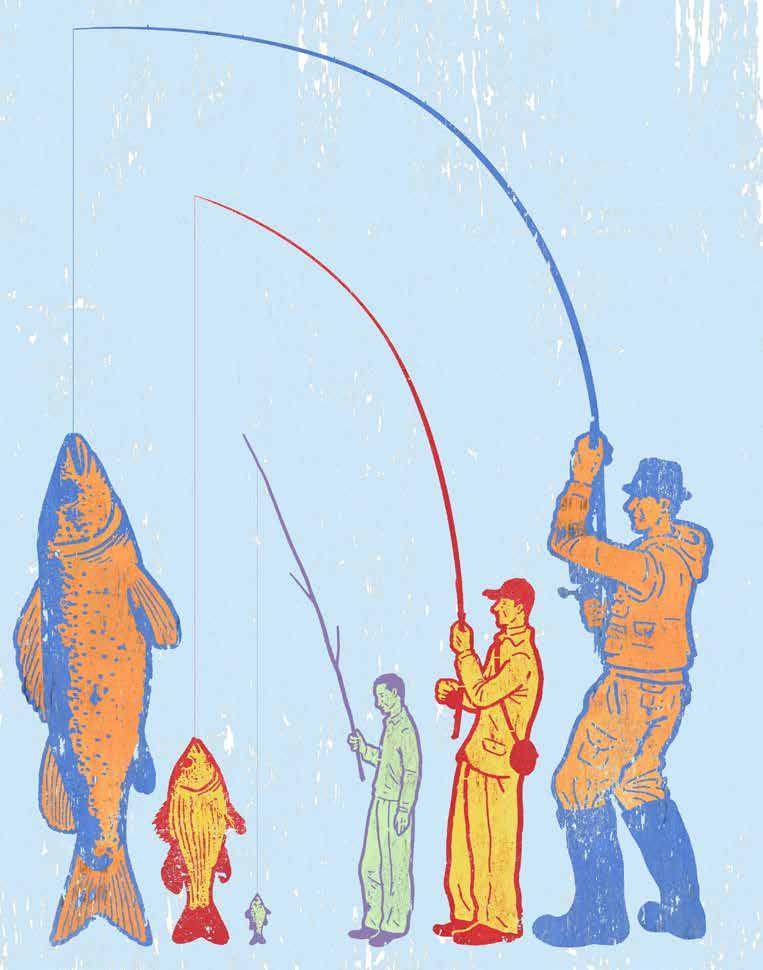

JUNE 2024 5 34 SEVEN WAYS OF SAYING by john belk AMBOS NOGALES A city where the border doesn’t divide. by natalia galicza LETTERS FROM THE FIELD IDEAS COMMENTARY POINT/COUNTERPOINT ODE THE LAST WORD CULTURE NATIONAL AFFAIRS THE WEST THE BREAKDOWN MODERN FAMILY WINDOW ON A HILL Salt Lake City’s unique photographic history. by joe marotta 72 CAST AWAY Ode to live bait. by ethan bauer 78 THE CHAPLAIN On spirituality in the military. by lois m collins 80 REIMAGINING EARLY EDUCATION An opportunity for conservatives, if they’ll take it. by frederick m hess and michael q mcshane 64 THE OPEN ROAD Confessions of a born-again traveler. by alan j hawkins 15 WATER WORKS What’s next for the dams that built the West? by clay grubbs 16 COLD COMFORT America’s shocking obsession with ice cream. by jennifer graham 18 THE DELICATE ART OF DOING NOTHING Boredom isn’t the enemy. by megan feldman bettencourt 20 SPACE FOR SALE I need a price check on the moon. by rebecca sohn 24 GLORY TO THE GRAND How the sand of the Colorado River gets under your skin. by heather hansman 28 “When borders close and policies change, families are separated.” 77 POETRY ON THE BRINK Facing the Social Security crisis. by andrew biggs 68 CONTENTS

Starling is an environmental journalist based in New York City. She writes about climate, conservation and culture. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Sierra Magazine, the Miami Herald, PBS and The Associated Press. Her story about the fate of the condor is on page 46.

Hawkins manages the Utah Marriage Commission and is an emeritus professor of family life at Brigham Young University, where he published widely on the effectiveness of relationship education and developed educational programs for families. His commentary on the value of taking a vacation is on page 15.

Twenge is a professor of psychology at San Diego State University, whose research has been featured in The New York Times, USA Today and The Washington Post. She has authored several books, including “iGen,” “Generation Me” and “Generations.” Her critique of the new book “Bad Therapy” is on page 38.

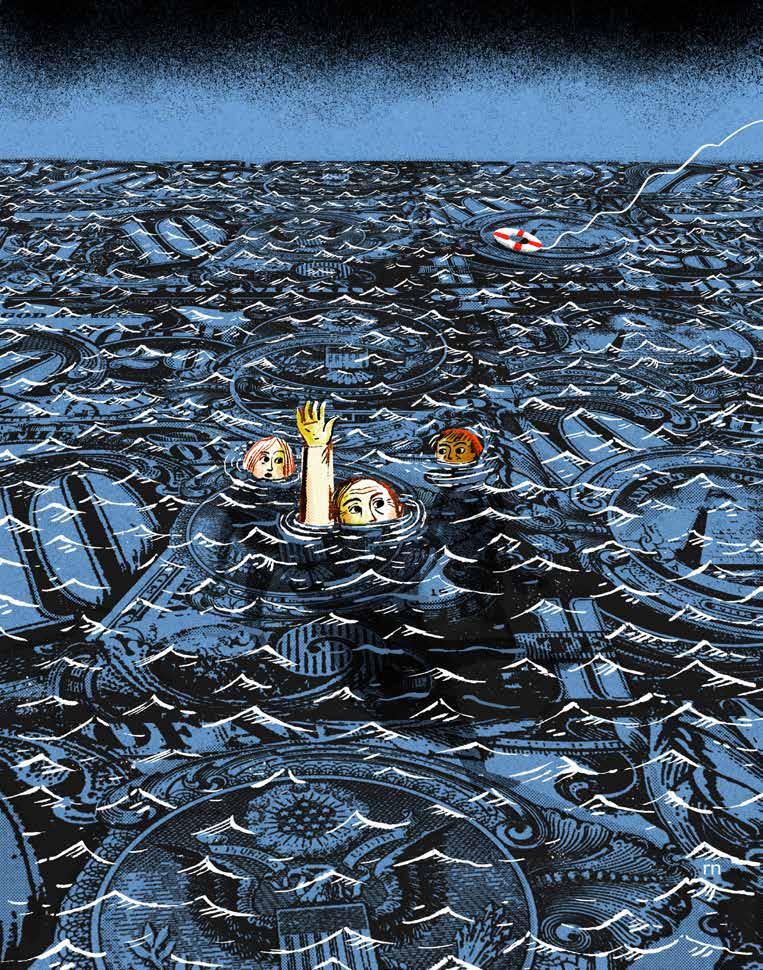

A senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, Biggs is a former principal deputy commissioner of the Social Security Administration. In addition to academic publications, his work has also appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post. His essay on Social Security reform is on page 68.

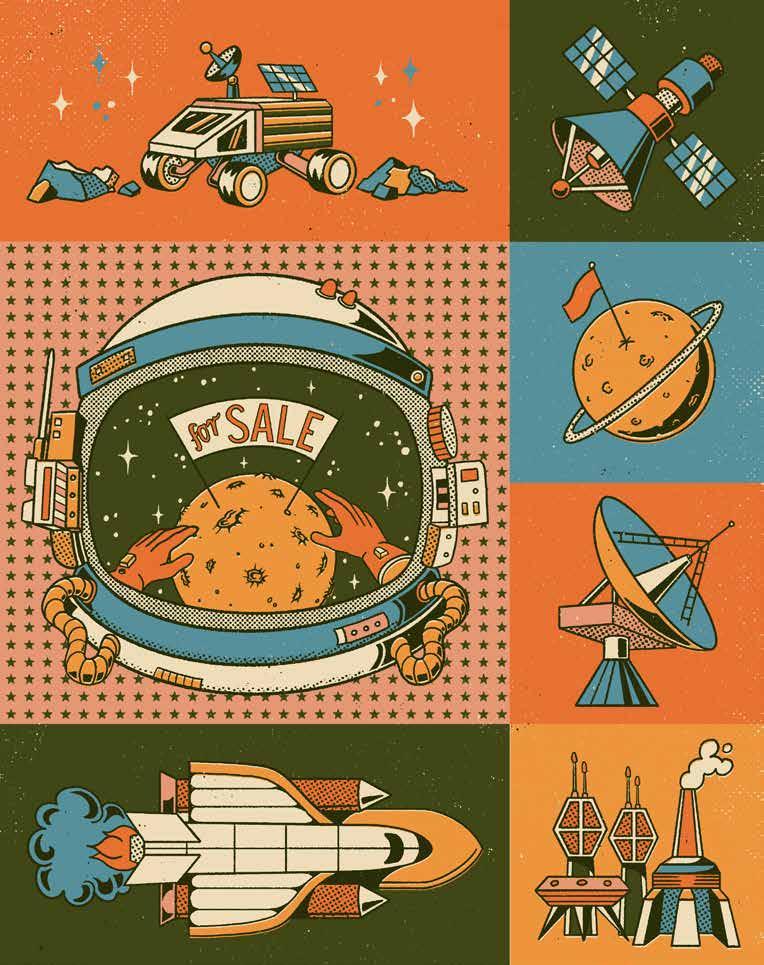

Sohn is a health and science writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Slate, Popular Science and The Verge, among others. She is a former science fellow at Mashable. Her report on the commercial development of the cosmos is on page 24.

Choi is an award-winning Korean/Canadian illustrator and printmaker based in London, specializing in visual narratives. She has won or been shortlisted for multiple international awards and exhibited at various galleries, including the Royal Academy of Art Summer Exhibition. Her illustrations appear on page 38.

6 DESERET MAGAZINE CONTRIBUTORS

SUNNU REBECCA CHOI

MARLOWE STARLING

JEAN M. TWENGE

REBECCA SOHN

ALAN J. HAWKINS

ANDREW BIGGS

Unleash your inner adventurer

Experience award-winning hospitality at America’s most pet-centric hotel.

Located in the majestic red rock splendor of Kanab (just 5 miles from Best Friends Animal Sanctuary), the Best Friends Roadhouse and Mercantile offers:

• Luxurious amenities for you and your pet

• Two dog parks with a splash zone

• Delicious vegan breakfast every morning

• Live music May through October

• Fun, unique merchandise

• Free daily Sanctuary tour shuttles

• Sleepovers with pets from the Sanctuary

Whether you want to volunteer with animals, bring home a new best friend, or enjoy a beautiful base camp within 90 minutes of three national parks, the Roadhouse is the ultimate option for animal lovers that supports the lifesaving work of Best Friends Animal Society.

Make your reservation today! bestfriendsroadhouse.org 435-644-3400

Winner - Best of State Utah

Best Motel 2022 & 2023, Best of the Best Hospitality 2023

Discover new gospel insights with Continuing Education InspirED. This growing online media library contains classes from BYU Continuing Education events and is now the only place to access BYU Adult Religion Classes. Start your free trial today! Elevate Your Understanding Explore the library at inspired.byu.edu Join Us August 19–23, 2024

OUT OF THE DARKNESS

Her name was Alice. She belonged to our Latter-day Saint congregation, and my dad and I were assigned to visit her once a month. I dreaded these visits. I was 14 years old, and the last thing I wanted to do on a Sunday afternoon was sit in the stuffy apartment of an elderly widow who seemed defined by one characteristic above all others: She was incredibly lonely.

Sometimes, as my dad listened patiently to stories Alice had shared again and again, I would study her family photos on the wall and imagine what her life must have been like before her husband died and left her alone. But most of the time I would just count down the seconds until we could leave. I was put off by the oppressive mothball smell of her apartment. I resented the way my dad let these visits drag on for well past an hour. And I was irked at how tightly Alice hugged me every time we left, wordlessly begging us to stay. It made me feel guilty.

I couldn’t help remembering Alice as I read Natalia Galicza’s story about a man named Frank De Palma (“Alone,” page 54). Frank spent 22 years in isolation inside a maximum security state prison in Ely, Nevada. As Natalia notes, his loneliness and isolation became a darkness that enveloped him, until, as Frank puts it, darkness became his friend. He lost his sense of time, even his very sense of self. Now he is out of prison, but he still flinches at the light and considers himself peripheral to society, more shadow than person.

Reading Natalia’s story, I was surprised to learn that no country in the world uses solitary confinement as much as the United States. Natalia explores why this uniquely American phenomenon has become more widely used since the 1990s and details a recent bipartisan effort to curb the practice. I didn’t expect this story to rip my heart open, to bring tears to my eyes, or to make me think of my friend Alice. But it did.

On a lighter note, I was delighted by Marlowe Starling’s dispatch from Marble Canyon, Arizona, on the unlikely comeback of the California condor (“Consider the Condor,” page 46). I’ve learned that the condor, one of the West’s most iconic symbols, is a study in contradictions, described by early settlers as both “graceful and majestic” and a “huge monster.” It later became one of the first animals ever listed under the Endangered Species Act. Its resurgence from a near-extinct population of just 22 living birds in 1982 to an heartening 560 wild condors today is one of the great success stories of federal wildlife protection. It’s a nice reminder of our duty to be good stewards of the planet, and the varied and interconnected creatures that make the Earth hum like a finely calibrated machine. I also hope you’ll check out Jean Twenge’s exploration of a controversial new theory that the growth of therapy, widely seen as our best effort to solve today’s teen mental health crisis, could actually be its underlying cause (“Are the Kids All Right?” page 38). Twenge, one of the first academics to sound the alarm about the impacts of social media and teen mental health, examines the theory advanced by New York Times bestselling author Abigail Shrier and finds that she agrees with some conclusions and disagrees with others. What ties these stories together for me is a sense of shared responsibility to our planet, our kids and our neighbors — like my friend Alice. She died years ago, but I often recall the years my dad and I kept visiting her, long after it was no longer an assignment. As I grew up, I came to enjoy the time we spent there. Instead of feeling guilty when Alice hugged me goodbye, I felt bad that she didn’t have more people to visit her. And I remember the Bible verse my dad would often quote after those visits: “Pure religion and undefiled before God and the Father is this, to visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction, and to keep himself unspotted from the world.”

—JESSE HYDE

JUNE 2024 9

THE VIEW FROM HERE

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

HAL BOYD

EDITOR

JESSE HYDE

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

ERIC GILLETT

MANAGING EDITOR

MATTHEW BROWN

DEPUTY EDITOR

CHAD NIELSEN

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

JAMES R. GARDNER, LAUREN STEELE

POLITICS EDITOR

SUZANNE BATES

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

DOUG WILKS

STAFF WRITERS

ETHAN BAUER, NATALIA GALICZA

WRITER-AT-LARGE

MICHAEL J. MOONEY

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

SAMUEL BENSON, LOIS M. COLLINS, KELSEY DALLAS, JENNIFER GRAHAM, MARIYA MANZHOS, MEG WALTER

ART DIRECTORS

IAN SULLIVAN, BRENNA VATERLAUS

COPY EDITORS

SARAH HARRIS, VALERIE JONES, CHRIS MILLER, HANNAH MURDOCK, TYLER NELSON

DESERET MAGAZINE (ISSN 2537-3693) COPYRIGHT © 2024 BY DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. IS PUBLISHED MONTHLY EXCEPT BI-MONTHLY IN JULY/AUGUST AND JANUARY/FEBRUARY BY THE DESERET NEWS, 55 N 300 W, SUITE 400, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH. TO SUBSCRIBE VISIT PAGES.DESERET.COM/SUBSCRIBE. PERIODICALS POSTAGE IS PAID AT SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH

POSTMASTER: PLEASE SEND ADDRESS CHANGES TO PO BOX 2220, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH 84101.

DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO.

PUBLISHER BURKE OLSEN

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER ERIC TEEL

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT SALES

TRENT EYRE

VICE PRESIDENT SALES SALLY STEED

PRODUCTION MANAGER

MEGAN DONIO

OPERATIONS MANAGER

BRITTANY M C CREADY

DIRECTOR OF CIRCULATION

SYLVIA HANSEN

THE DESERET NEWS’ PRINCIPAL OFFICE IS 55 N. 300 WEST, STE 400, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH. COPYRIGHT 2024, DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA.

DESERET

PROPOSED AS A STATE IN 1849, DESERET SPANNED FROM THE SIERRAS IN CALIFORNIA TO THE ROCKIES IN COLORADO, AND FROM THE BORDER OF MEXICO NORTH TO OREGON, IDAHO AND WYOMING. INFORMED BY OUR HERITAGE AND VALUES, DESERET MAGAZINE COVERS THE PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF THAT TERRITORY AND ITS INTERSECTION WITH THE BROADER WORLD.

10 DESERET MAGAZINE

DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE AMERICAN EDUCATION THE PATHWAY AN ODE TO THE TRAMPOLINE AWARD-WINNING JOURNALISM ABOUT THE PLACE WE CALL HOME SCAN HERE TO SUBSCRIBE DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE MILITARY SPENDING — BAILOUT OR FALLOUT? BAD BETS CALIFORNIA EXODUS THE OTHER MARCH MADNESS DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE JUNE 2023 THE FAITH OF MIKE PENCE COLORADO RIVER TIPPING POINT? DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE MITT ROMNEY ON E NATION UNDER GOD? JFK CONSPIRACYDESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE ABBY COX STATE WEST OF THE NAVAJO NATION

OUR READERS RESPOND

Our “faith issue” in APRIL featured a profile of Washington, D.C.-based law firm Becket, which takes on religious liberty cases from a broad swath of faith groups that claim the government has violated their constitutional right to exercise their religious beliefs (“Keeping The Faith”). The story focused on a Native American tribe suing the government for approving a copper mining operation in Arizona that will destroy land sacred to the San Carlos Apaches. Reader Jayson Meline noted the Arizona case shows that emulating Becket’s respect for freedom of conscience could help people and institutions avoid conflicts over issues of religious belief in the workplace and other public places. “Becket in its practice of law demonstrates freedom of conscience cuts both ways,” Meline wrote. New York Times columnist Bret Stephens explained how Abraham Lincoln’s little-known views on technology and democracy can inform how we respond to today’s rapidly changing world (“Lincoln’s Lost Lecture”). Vicki Rulison praised the piece’s perspective, then observed: “I do appreciate how the internet has made information so readily accessible, but with so many voices it has rendered whatever is honest often indecipherable. I can’t imagine we have ever lived in a more confused or divided nation.”

Michael J. Mooney explored what’s driving a loneliness epidemic among men (“Lonely Men: The Sounds of Silence”). Food and the traditions around its preparation can forge friendships and bonds that last generations, wrote Natalia Galicza in an essay that explored the human impulse to preserve family recipes (“Culinary tradition: Why family memories live in the kitchen”). Lennon Flowers , who was featured in Galicza’s article, had this to say: “Beautiful piece, and an angle that’s rarely talked about in either the food or grief worlds.”

“Our direct connection to God is here, it’s where we listen to the creator. Oak Flat is crucial for our survival.”

JUNE 2024 11 THE BUZZ

MARIA FEDOSEEVA REUTERS / MIKE BLAKE

12 DESERET MAGAZINE OPENING SHOT

MONUMENT

VALLEY SUNSET

PHOTOGRAPHY BY AUSTIN PEDERSEN

JUNE 2024 13

Won’t you be my neighbor?

Mister Rogers

FRIEND SHIP

THE OPEN ROAD

CONFESSIONS OF A BORN-AGAIN TRAVELER

BY ALAN J. HAWKINS

I’m a convert to the importance of vacations, a believer in how such special temporal zones can strengthen relationships and sweeten our days.

I was not always zealous about vacation time. My wife, Lisa, and I lived on a meager income for many years after we married, so perhaps our indifference to taking time off was rooted in necessity. And those early schooling, work and parenting years fully absorbed not just our means but our time and energy. Finding some fun and refreshment in our day-to-day prosaic life was a survival strategy. Short drives with the family through the gentle hills of central Pennsylvania to pick berries or cut down a Charlie Brown-ish pine tree for Christmas was about the best we could do. (Of note, research suggests that leisure and travel — that may take money away from necessities — may not have the same benefits for poorer families.)

Rare were those special family road trips that my former BYU colleague Susan Rugh wrote about in her delightful modern history of the American family vacation, “Are We There Yet?” In the post-World War II era, increasing middle-class incomes, big cars, new interstate highways, popular national parks and nuclear family values combined to produce a surge in family travel that captured the essence of an era (despite the children’s backseat bickering). The few road trips my family experienced usually had a clear utilitarian element, such as moving to a distant city for schooling or employment with a trailer in tow. Our five-day cross-country adventure from the Bay Area to central Pennsylvania for my doctoral

studies (with a brief stop in Chicago for our son’s emergency appendectomy) conjures up laughs and odd memories today. But it was anything but relaxing and refreshing.

It’s not that I was unaware of the importance of curating novel experiences and keeping the fun in relationships. I’m a relationship and marriage researcher and educator by trade. I teach this stuff! So, I sensed the risk in my casual commitment to couple and family vacation time.

Eventually, our economic fortunes improved. But by that time, our children were in their mid-teenage years with plans of their own. Our work and life demands didn’t fade; yet it got easier to attend to that gnawing need to call a timeout to the daily grind and take some real time off. So, in midlife, Lisa and I began to plan a couple of trips.

I trace my conversion to the personal and relational value of travel vacations to our first cruise — to Alaska. The stress-free days, gentle rocking motions of the ship, mesmerizing ocean waves, oxygen-saturated sea-level air, clouds-and-snow-covered summer peaks and humpback whales — we could feel the accumulated drudgery dissolving. And the stress-free time together somehow translated into more bonding talk — about meaningful experiences in the past and especially about our dreams and plans for the future.

Of course, it’s not just the relaxing and fun itself that buoys the spirit and sweetens the companionship. The anticipation put some sparkle in the days that preceded the trip and the memories of those times together are inextricably woven into our unique couple identity now; a part of who we are together is where we have been during those vacations. (The Norwegian fjords that awed us for a few days a decade ago are a continuing rich source of connection for us, facilitated by framed photos hanging on our walls.)

And in the Vrbo age, we have initiated biennial sibling reunions, usually close to some West Coast beach. I admit that I neglected sibling relationships during those busy family- and career-building decades. I did so knowing — again — the research on how valuable it is to maintain those connections. Sibling relationships are the longest family relationships we have and can be a vital source of support and meaning in our lives. And they testify to how we grow, change, forgive and forget in family relationships. That sibling fractious tension of the first two decades of life has morphed into sweet and rich friendship in the last few decades of life.

So, I’m a born-again believer now in the family or couple getaway. Personal experiences in later life have convinced me of the empirical accuracy of what I taught my students for decades. Family relationships are deepened and strengthened and blessed by special times away from our ordinary daily lives. With the summer travel season upon us, here’s to your family vacations in their many flavors, locations and seasons of life.

JUNE 2024 15 ILLUSTRATION BY KYLE HILTON COMMENTARY

ALAN J. HAWKINS IS MANAGER OF THE UTAH MARRIAGE COMMISSION AND AN EMERITUS PROFESSOR OF FAMILY LIFE AT BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY.

WATER WORKS

DAMS BUILT THE WEST. SOME WANT THEM GONE

THE LARGEST DAM removal project to date is underway on the Klamath River, where it crosses the Oregon-California state line. There is little controversy that these four hydroelectric dams, built between 1908 and 1962 along a 35-mile stretch, have outlived their utility. But the empty reservoirs highlight a movement that is accelerating around the world. Eighty dams were decommissioned on American rivers in 2023, along with 487 in 15 countries across Europe. Here in the Western U.S., dams have shaped cities, economies and lifestyles for well over a century. Is it wise to tear them down? CLAY GRUBBS

16 DESERET MAGAZINE POINT / COUNTERPOINT

LET NATURE RUN ITS COURSE IF IT AIN’T BROKE

IT’S TIME TO rethink our relationship with rivers. Once we saw them as dangerous forces of nature to be conquered and controlled for maximum efficiency. But today, we understand the costs and impacts of those efforts, no matter how good the intention, from levees on the Mississippi to the Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado. Many dams are simply outdated, silted up or at risk for collapse. In general, wild rivers foster healthier ecosystems and support human communities more effectively than waterways controlled by humans.

Rivers anchor complex biomes built on natural cycles like drought and flooding, which keep habitats vital and healthy for all manner of organisms, from aquatic plants to birds of prey and even people. Dams disrupt those cycles, and our attempts to replicate their benefits tend to fall short. Dams also lead to warmer waters, harming native fish species and breeding toxic algae. And of course, they limit breeding areas and block upstream spawning routes. Even the workarounds, ranging from “fish ladders” to “fish cannons,” can be harmful. Hundreds of thousands of juvenile salmon recently died on the Klamath due to gas bubble disease, caused by pressure changes in the water as they passed through a tunnel in the Iron Gate Dam.

More broadly, salmon populations are in peril throughout the Northwest, which keenly affects certain Indigenous groups who have lived along the rivers for ages but were largely overlooked by society when the dams were built. Many rely on native fish as a foundation for traditional lifestyles and even spirituality. Some have been displaced by reservoirs and new flood patterns, or impacted by attendant real estate development. “They’ve taken our land, they’ve taken our rivers, they’ve taken our fish,” said Carrie Sampson, elder of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, on the lower Snake River. “I don’t know what more they want.”

Traditionalists may well venerate dams as exemplars of American ingenuity and sacrifice, but many dams just don’t offer enough benefits to justify the costs of upkeep. On the lower Klamath, the price of fish ladders required by law was enough to push former owner PacifiCorp to favor removal. “We’re not ideological about it,” said Bob Gravely, spokesman for the energy company.

HUMAN BEINGS HAVE depended on dams for millennia. From the Middle East to China and the Rocky Mountains, we’ve used them to prevent flooding, irrigate arid land and store up water for the opposite of a rainy day. But they’ve shaped the American West to an extreme degree, allowing millions of people to inhabit homes in otherwise inhospitably arid desert environments. They should not be removed casually, ignoring the wisdom of our forefathers to appease special interests like the environmentalist lobby.

Grand structures like the Hoover Dam on the Colorado River — completed in 1935 and named one of the “Seven Modern Civil Engineering Wonders” — are monuments to human innovation that merit respect and preservation as part of American history. But they are also essential tools for ensuring that millions of people, from Phoenix to Los Angeles and Salt Lake City, have access to drinking water. Along with smaller dams throughout our river systems, they protect many towns from seasonal flooding and help us to grow crops or feed cattle. Ranches and farms often depend on reservoirs and canals to irrigate land and make rivers navigable, allowing them to efficiently and cost-effectively transport goods to coastal markets.

Hydroelectric power produced in dams also plays a vital role in providing energy across the West. For instance, five dams on the lower Snake River that are targeted for removal produce 12 percent of the electricity in the Federal Columbia River Power System in an average year, enough to power a city the size of Seattle. Existing plans to develop alternative sources would cost billions of dollars and likely raise annual rates by at least $100 per household.

Even if dams are not ideal, removing them risks unanticipated consequences. After the Klamath’s Copco Dam No. 1 was breached, fish and deer were found stranded and dying on the muddy riverbank, and nearby property owners worried about their wells, home foundations and flooding. On a larger scale, advocates for removal may be missing some of the implications of their desired policy. What happens when a dry year means there’s not enough water for the millions of people who live in Las Vegas? Around 21,000 men worked and sacrificed to build Hoover Dam. Maybe we should have a little more respect for what they accomplished.

JUNE 2024 17 ILLUSTRATION BY JACOB PLEITEZ

COLD COMFORT

WHEN IT COMES TO ICE CREAM, AMERICANS FIND A LOT TO LOVE

ICE CREAM IS synonymous with an American summer. When a familiar ditty plays over the tinny speakers of an ice-cream truck in any neighborhood, mouths of all ages begin to salivate. There are other foods we eat when it’s hot — like watermelon, hot dogs and tomatoes — but ice cream helps to keep us cool and sane. From modern gourmet flavors to the humblest grocery store brand, there’s no such thing as bad ice cream, especially if it’s fresh. Here’s why there’s so much to love.

JENNIFER GRAHAM

4 BILLION POUNDS

That’s how much ice cream Americans consume annually, amounting to more than 20 Nimitz aircraft carriers. That’s based on an estimate that the average American eats 12 pounds in a year — down from a whopping 16 pounds per person in 2000. Nearly three-quarters of us still report eating ice cream at least once a week.

Average yearly ice cream consumption per American:

16

SEPTEMBER 9, 1843

On that day, Philadelphia housewife Nancy Johnson obtained a patent for a device that would revolutionize the “art of producing artificial ices.” Her invention, the basis of today’s standard ice cream churns, improved on an age-old treat similar to snow ice cream. Roman emperor Nero sent slaves to the mountains to collect snow and ice to be mixed with fruit and honey. Other iced treats were created in China and other ancient civilizations.

18 DESERET MAGAZINE THE BREAKDOWN

pounds

pounds 2000 2024

12

4 INGREDIENTS

Thomas Jefferson’s recipe for ice cream — likely passed on by his French butler, found among 10 handwritten recipes in the third U.S. president’s personal papers — called for just two bottles of good cream, six egg yolks, a half-pound of sugar and a stick of vanilla. The process, however, was fairly complicated, including towel-straining and a fire. His successor’s wife, Dolley Madison, had more exotic tastes, with a predilection for oyster ice cream.

That’s when a man named Harry Burt of Youngstown, Ohio, first sold ice cream from a truck. The food’s popularity surged during Prohibition, as adults who could no longer drink alcohol legally turned instead to sweets. Burt also founded the Good Humor brand, known for his novelty “ice cream on a stick” and salesmen who tipped their hat to women and saluted men.

$100 A WEEK

By 1932, Good Humor drivers were earning that much each week, more than $1,800 when adjusted for inflation. While the tell-tale jingle may feel less common now, business is thriving. One company in Massachusetts said its drivers make $20-$30 an hour, plus tips — plus a signing bonus. And in a new twist, certain ice-cream truck drivers in New Jersey will show up at your door if you text them.

“We simply don’t have enough good-quality evidence to suggest that ice cream definitely has any health benefits. But a couple of small portions a week — paired with an otherwise healthy diet and exercise regime — is unlikely to do much harm.”

DUANE MELLOR, ASTON UNIVERSITY

Orders shipped from Jeni’s Ice Creams of Columbus, Ohio, arrive sci-fi cold, thanks to dry ice. Competitors from specialty shops to large retailers like Harry and David’s also ship anywhere in the U.S. In recent decades, weird science has also gifted us with “beaded” ice cream like Dippin’ Dots and nitrogen ice cream from a Utah-based chain called Sub Zero.

31 FLAVORS

That’s the threshold for a product to qualify as ice cream, according to the federal government, in a mixture of dairy, sweetening and flavors that must weigh 4.5 pounds to the gallon. Vegan ice cream is out. So are soft-serve cones and other fast-food frozen dairy treats. And while most brands at the supermarket qualify, many are also ultra-processed foods, linked to signs of addiction in a recent study by the University of Michigan.

The old Baskin-Robbins moniker sounds quaint in a world with ice creams that taste like mac and cheese, dill pickles, lobster and Thanksgiving dinner. Polling shows New York still prefers pistachio; South Dakota loves birthday cake; and Oregonians favor green tea. For Utahns, nothing tops rocky road — chocolate ice cream with nuts and marshmallows — which was adventurous for the 1920s, when two companies in Oakland, California, claim to have invented it. The author prefers the taste of frozen custard, though it’s not even ice cream.

4.5 pounds

Dairy, sweetening and flavor mixture must weigh to the gallon.

JUNE 2024 19

1920

-109.3°F

10% MILKFAT

ILLUSTRATION BY BRENNA VATERLAUS

THE DELICATE ART OF DOING NOTHING

PARENTS DREAD SUMMER BOREDOM. WHY THEY SHOULDN’T

BY MEGAN FELDMAN BETTENCOURT

On the morning of my daughter’s fifth birthday party, I made a cheese tray for parents and set out craft projects for kids before anxiously writing a run-of-show at my kitchen counter. My husband, having plucked the last of the dirty laundry off the floor, sidled up next to me and raised his eyebrows. “What are you doing?” he asked.

“What does it look like?” I snapped, glancing at the clock. “I’m making an agenda!” This was the first party we had hosted since before the pandemic. Every recent birthday party we were invited to was held at an overpriced (and overstimulating) location built to entertain. A giant trampoline park. A labyrinthine ropes course. Chuck E. Cheese. What on Earth would we do with 10 kids and a dozen parents in our unremarkable suburban home?

My husband was quiet for a moment. He was choosing his words carefully. “Don’t

you think we could let it evolve organically?”

“But what if they’re bored?” I was horrified at just the thought of parents milling about the house, awkwardly picking lint off their sweaters and checking their phones.

IT TURNS OUT THAT BOREDOM IS IMPORTANT FOR STIMULATING CREATIVITY AND PROBLEM-SOLVING, AS WELL AS FOR GIVING OUR BUSY BRAINS SOME MUCHNEEDED REST.

And what about the kids, who were used to inflatable slides and loud video games — would they be bored, too?

As I looked at my husband, I saw myself through his eyes: a mom so insistent on

warding off boredom that I was applying the agenda-writing skills I used at work to a kindergarten birthday party. The first guests knocked on the door.

I hoped everyone would have a good time. But above all, I feared they would be what has somehow become one of the worst things in our frenetic society, built around accomplishment, and “life hacks,” and optimizing every minute: bored.

MOST PEOPLE, KIDS and adults alike, find boredom uncomfortable and strive to avoid it. Especially now, as summer begins, parents like me are scrambling to fill our children’s calendars. This preference for being occupied and entertained has grown with the advent of technologies that enable us to do routine tasks faster and remain constantly connected. If we’re not working outside the home, doing house chores or talking on the phone while driving, we

20 DESERET MAGAZINE MODERN FAMILY

MANY OF US DESIGN OUR CHILDREN’S LIVES IN WAYS THAT MINIMIZE THEIR OPPORTUNITIES FOR BOREDOM AND THE CRUCIAL DEVELOPMENT THAT COMES WITH IT.

are scrolling Instagram, devouring digital news or coaching youth soccer. Kids are busier than ever, too, engaged in long days of school, extracurriculars, homework and social media.

The casualties of this harried state of constant activity are rest, relaxation, hobbies, unstructured time, in-person social connection and even boredom itself. The effects on our mental health are alarming. American workers are reporting record-breaking rates of burnout and stress, while skyrocketing rates of depression, anxiety and suicidality in kids have prompted children’s hospitals to declare a national state of emergency for youth mental health. It turns out that boredom is important for stimulating creativity and problem-solving, as well as for giving our busy brains some much-needed rest. When we notice the stillness or disinterest that most of us characterize as boredom, responding in constructive ways pays dividends in productivity, creativity, social connection and mental wellness.

So if boredom really is good for us, then how can we learn to incorporate it into our lives despite the constant pressure to avoid it?

In psychiatric literature, boredom is defined as a state of mind featuring disinterest or lack of stimulation or challenge. Ironic, since being bored these days is a challenge itself. Boredom often arises from repetitive tasks or a lack of novelty, and can make us feel restless. We ideally learn to tolerate and productively manage that restlessness, starting in childhood. Being bored prompts kids to make up imaginary games, initiate play with other children and take a proactive role in their own activities. This builds creativity and problem-solving skills, as well as social acumen, resilience, independence, initiative and self-esteem.

Yet many of us design our children’s lives in ways that minimize their opportunities for boredom and the crucial development that comes with it. We make sure their calendars look like that of a full-time working adult. Cringing at the whiny refrain, “I’m

bored!” we orchestrate a game or allow hours of screen time so we can get things done or enjoy a break, all the while robbing them of the chance to develop positive coping skills.

Unfortunately, over the past 60 years, American children have spent less and less time engaged in self-directed play with each other and more and more time in adult-led activities that leave little time for being bored or conducting their freestyle type of play (child development experts define play as an activity a child chooses to do, rather than is obliged to do, and which involves imagination, scant or no adult interference and a focus on means more than ends). Psychologists connect this decline to rising anxiety and depression in children and teenagers. The link makes sense, as anxiety, in particular, is directly linked to feeling a lack of control over one’s life.

Technology is also a societal shift that has robbed children of the chance to be bored. Psychologists point out that the rise of pediatric anxiety, depression and suicide that began in 2005 and skyrocketed starting in 2012 mirrors the rise of smartphones and social media. Constant social media scrolling comes with overwhelming information bombardment and a lack of rest, stillness, unstructured time and boredom.

A consequence of depriving kids of the freedom to be bored is that when the restless feeling does arise, they lack coping skills and are more likely to respond with risky behavior such as dangerous thrill-seeking or substance abuse. There’s a reason that evidence-based therapy for a range of pediatric mental health conditions, from anxiety and depression to aggression, focuses on one key skill: the ability to notice, embrace, process and navigate difficult emotions. Take, for instance, boredom. The better kids and adults alike become at doing so, the more resilient we are.

As we become adults, our need for boredom becomes a need for unstructured, independent and self-chosen activities that allow us to engage with the present moment instead of a future goal. This could

22 DESERET MAGAZINE MODERN FAMILY

be taking a stroll or engaging in a beloved hobby or spending time practicing your faith or meditating or literally “doing nothing.” In “Niksen: Embracing the Dutch Art of Doing Nothing,” author Olga Mecking defines “niksen” as doing nothing without a purpose. Italians, meanwhile, prize “il dolce far niente,” the sweetness of doing nothing. If all this sounds similar to Buddhist principles of being present in the moment and practicing mindfulness meditation (sitting and breathing while noticing your thoughts and bodily sensations), that’s because it is. The common focus is on being (in the moment) as opposed to doing (to reach a future goal).

Counterintuitive as it may seem, making time to do less recharges our brain, restores our mood and brings heightened powers of critical thinking and strokes of insight. Albert Einstein reportedly spent a lot of time away from friends, family and work to do nothing but think, and some of his best ideas came while walking, sailing or playing his violin alone. Most of us have had the “epiphany in the shower” experience, when a mundane activity like bathing brings creative solutions, seemingly out of nowhere. For me, this happens during my daily walks, when I often have so many ideas that I need to dictate them into my phone.

BEING FOCUSED ON the present moment without a care for “getting things done” is not a natural setting for most Americans. The Puritan belief that “an idle mind is the devil’s workshop” still influences many of us, while our culture’s celebration of celebrity has conflated happiness with the materialistic push for more, bigger and better.

Then there’s the issue of free time. For decades, the average American’s buying power has evaporated while wealth has concentrated in the top tier of the economy. Prices for basic necessities have surged. In my grandparents’ day, a police officer or teacher could buy a home and support a family with one salary. Now, households with two toiling earners are barely covering basic expenses, much less saving for retirement. Overwhelmed

working parents are less likely these days to have parenting support and need help with child care.

In this context, the suggestion to make time for boredom may seem unrealistic and even insensitive. Yet what if our lives depend on it? Stress can negatively affect our heart health, mood health and immune function, and Americans are more stressed than ever. According to a 2023 American Psychological Association survey, 77 percent of U.S. workers reported stress at work last year, with 57 percent reporting negative health effects as a result. Workplace burnout — linked to stress, anxiety and depression — has also reached record highs. At least 55 percent say they

COUNTERINTUITIVE AS IT MAY SEEM, MAKING TIME TO DO LESS RECHARGES OUR BRAIN, RESTORES OUR MOOD AND BRINGS HEIGHTENED POWERS OF CRITICAL THINKING AND STROKES OF INSIGHT.

can’t establish a work-life balance, and employees with the least financial security are most likely to be burned out, according to a Workforce.com report.

Though it might seem like we need a month of doing nothing on the beach to recover, one way to incorporate stillness into our schedules is with micro-moments. As a type-A parent who works outside the home, I try to do a five-minute meditation each morning between getting my kids off to school and diving into my inbox. I sit quietly and focus on my breath until my timer goes off. On days when I manage to do this, I feel calmer and more awake. Moments of nothingness don’t have to be meditation, though. I have a colleague who schedules daily dog

walks and lunch breaks, and another who grows chrysanthemums.

Another way to be “in the moment” is to use the concept of niksen and do what we’re already doing without multitasking or striving for a goal. It could be focusing only on our food while eating, for instance, or admiring the sights and sounds of the forest while hiking instead of talking or tracking our steps. On a recent drive through the Colorado plains, I resisted the urge to return phone calls or listen to the news. Instead, I rolled down the windows and blasted Tom Petty. When I arrived at my destination, I felt refreshed.

Infusing days with less doing and more being takes intention and discipline, like any habit. It takes standing firm against the cultural current that drifts ever toward exponential busyness. My resistance to stillness is not so different from my children’s cries of, “I’m bored!” In both cases, pushing through the resistance is worth it.

One recent afternoon, my nine-year-old son spent 10 minutes demanding more Nintendo time after his allotted hour was up and the tablet automatically shut off. I denied him and continued to work on my laptop. He walked away, dejectedly muttering something about being “so bored.” An hour later, he reappeared, proudly displaying a wooden walking stick that he had whittled outside. Other bouts of boredom have yielded blanket forts, elaborate dinosaur action displays and a catapult made of a cardboard box, plastic spoon and rubber band. Often, he and his sister collaborate on these projects or play “keepy uppy,” which involves keeping a balloon in the air for as long as possible.

This summer, during weeks when my son is not at camp but his father and I are working, I plan to use blocks of unstructured time during which he gets to choose what he does outside, which project to start, which book to read. Maybe structuring unstructured time is kind of an oxymoron and not exactly doing “nothing,” but it’s as close as I can get as a working parent. In a fast-paced world, more nothing is better than no nothing at all.

JUNE 2024 23

SPACE FOR SALE

WHAT’S THE FUTURE OF THE FINAL FRONTIER?

BY REBECCA SOHN

On February 22, 2024, the Odysseus spacecraft touched down on the moon. It was the first American spacecraft to land on the lunar surface in over 50 years, and, like its predecessors, it carried gear for NASA experiments. But it wasn’t owned by NASA. Instead, it was the product of space exploration company Intuitive Machines, making it the first spacecraft manufactured by a private company to land on the moon.

Intuitive Machines, based in Houston, Texas, might seem like just another player in the seemingly crowded — and growing — private space industry. Companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin, who, like Intuitive Machines, work with NASA to bring astronauts and equipment to space, are also committed to commercial spaceflight, already giving select private citizens a ride into space. Meanwhile, companies like AstroForge are attempting to make extraterrestrial mining a reality. Increasingly, these companies are the ones who own the

spacecraft being launched into the galaxy. While each is jockeying for position in the burgeoning market that space is becoming, their earthly establishment is largely based in the American West — a place that, not too long ago, to many people across the globe, felt something like space. A place

WITH SO MANY CURRENTLY EYEING THE COSMOS, IS SPACE THE NEXT FRONTIER IN PRIVATE DEVELOPMENT?

to be explored, “discovered,” mined, tamed and claimed. A place that could make a person rich. And, ironically, a place that, in the beginning of white settlements, only well-to-do people could access. However, this time, instead of gold and land, the

pioneers of space have their sights set on technological advancement and, well, actual space. With so many currently eyeing the cosmos, is space the next frontier in private development?

The ambiguity of the answer lies largely in the murkiness of the ownership — or lack thereof — of space. Questions about ownership in outer space might have previously existed only in science fiction, but took on new importance during the space race that raged after the West’s well-known chapter of early atomic development in New Mexico and during the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, according to science and technology historian Teasel Muir-Harmony. “A lot of these early laws were driven by a fear of nuclear weapons,” says Muir-Harmony, the curator of the Apollo Collection at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. “But they also dealt with questions of ownership.”

Unlike the plains, mountain ranges, deserts and rivers that unfolded before white

24 DESERET MAGAZINE

NATIONAL AFFAIRS

JUNE 2024 25 ILLUSTRATION BY PHILIPP BECK

settlers as they pushed west, ownership isn’t something that’s able to be claimed in space as of now, due to specific laws outlined in the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies. Commonly called the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, it became the central international pact of space law. Regarding ownership, the language is clear: No one can truly own outer space.

The treaty emphasizes that “no one can claim the territory of the moon or other celestial bodies,” says Muir-Harmony, nor any other part of outer space, including Earth’s orbit. Though the treaty technically only says nations can’t claim sovereignty over space, a country wouldn’t have the authority to let a private company own part of outer space without some kind of claim of ownership themselves, which would violate the treaty. The United States, the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom were among the first countries to sign the treaty, and today, 114 countries have signed and now observe the laws it outlines.

It’s worth noting that the lack of any ownership created by the Outer Space Treaty has caused its own problems. For instance, the treaty says nothing about regulating waste in space, and without any country owning space, no one is responsible for keeping it clean, writes Chris Impey, a professor of astronomy at the University of Arizona. There are over 9,000 satellites and 23,000 pieces of debris in Earth’s orbit alone. That’s not even counting the nearly 100 bags of human waste, 200 tons of trash and the remains of over 50 crashed rockets that litter the surface of the moon.

More than a decade later, the Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, usually called the Moon Treaty, emerged in 1979. It outlines more regulations around exploring and taking resources from planetary bodies. But unlike the Outer Space Treaty, not a single nation with an active space program signed and passed corresponding laws that would enforce the treaty. “There

was concern in the U.S., especially voiced by many space advocates at the time, that agreeing to the moon agreement would discourage investment of private industry in space and inhibit future exploration,” says Muir-Harmony. Since then, how people will choose to preserve space — or not — has been up for debate.

IN DECEMBER 2023, the Biden administration proposed a new framework to Congress to regulate these businesses called the Novel Space Activities Authorization and Supervision Framework. The framework is a first step in regulating what private companies might launch into space: for instance, spacecraft for asteroid mining or space tourism. The secretaries of

NOT EVERYONE AGREES THAT WE SHOULD BE CONCERNED ABOUT EXPORTING ALL OUR EARTHLY PROBLEMS WITH OWNERSHIP INTO THE COSMOS. NOT FOR A LACK OF PRECEDENCE HERE, BUT FOR A LACK OF POSSIBILITY OUT THERE.

the departments of Commerce and Transportation would share responsibility for authorizing and supervising new uses of space, though the framework also creates an interagency group that would work with industry to discuss how future endeavors in space might be regulated. The administration also submitted draft legislation to give the departments this new regulating power in November 2023. But Congress hasn’t passed it, and many industry groups object because of what they see as too much government oversight. It’s unclear if or when it might take effect. Without this kind of future regulation, it might seem strange that countries can control what goes on in space at all — in fact, that regulation might seem similar to a

kind of ownership. Having the right to use a space, especially exclusively, is another key concept in how people imagine ownership.

“One of the general ideas about ownership is that you can exclude other people,” says Steve Mirmina, an adjunct professor of space law at Georgetown University Law School. Because no one can own space, current law wouldn’t allow, for instance, an asteroid mining company to prevent another company from mining the same area. But in the interest of safe use, it’s possible that in the long term, policies may change and allow some exclusive access to a part of space — for instance, groups doing research or mining in a certain area.

Many people have raised questions about the extraction of resources in space before — in fact, they were the subject of the Moon Treaty, says Muir-Harmony. That the United States and other countries never signed on left the subject, largely theoretical at the time, unresolved. Consequently, situations the treaty might have applied to have remained legally ambiguous. For instance, it has been unclear who legally owns the over 800 pounds of lunar samples brought back to Earth from the Apollo missions. At the time they were brought to Earth, no law governed the use of resources from space, and the Outer Space Treaty does not lay out any guidelines for who owns materials brought to Earth from outer space. Still, the United States has always acted as if it owns them.

It’s only recently we’ve begun to revisit these issues. In 2015, the U.S. passed the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, which allows U.S. companies and citizens to own resources from space. The act was immediately controversial, with some arguing that it violates the Outer Space Treaty by allowing the ownership of a part of space. There’s also the question of how to interpret the law: When might something count as territory versus resources? “I don’t actually know how that gets resolved,” says Matthew Weinzierl, a professor at Harvard Business School who has done research on the economics of the

26 DESERET MAGAZINE

NATIONAL AFFAIRS

space industry. Interpretations as simple as this are capable of showing the cracks. It’s unclear how companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin and extraterrestrial mining operations like AstroForge see their role in future space presence and treaty agreements. Deseret Magazine reached out to these companies but did not receive a response from SpaceX, while both Blue Origin and AstroForge declined to comment.

NASA’s upcoming return to the moon as part of its Artemis missions has also prompted the drafting of a set of nonbinding international agreements called the Artemis Accords. The accords reiterate the 2015 law and set up so-called “safety zones” for exclusive study or resource extraction on the moon and other celestial bodies. Like with the 2015 act, those opposed characterize the Artemis Accords as allowing private ownership of celestial bodies in all but name if companies are “saying that (they) can use this area and no one else can,” says Brendan Rosseau, a researcher at Harvard Business School who works with Weinzierl. Despite objections, 39 countries have so far signed the agreement. Still, neither Russia nor China has signed on, highlighting the continued disagreement between people and nations about how we should explore, utilize or even own outer space, says Muir-Harmony.

But really — could we actually mine space? Are companies going to run non- NASA -funded moon missions or launch space hotels? Is space a “frontier” at all? Is all of this discussion even worth it?

NOT EVERYONE AGREES that the world needs new regulations on things like mining in

REGARDING OWNERSHIP, THE LANGUAGE IS CLEAR: NO ONE CAN TRULY OWN OUTER SPACE.

space, or that we should be concerned about humans exporting all our earthly problems with ownership into the cosmos. Not for a lack of precedence here, but for a lack of possibility out there. “I think these claims about resource utilization are greatly exaggerated,” says space historian Dwayne Day. With companies focused on asteroid mining, such as Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries, having already failed or pivoted to developing other technologies, he also doesn’t see these companies as realistic ventures. From his perspective, claiming land in space would be as meaningful as claiming a remote stretch of ocean without the ability to defend it, regulate it or extract resources from it. Aside from mining rare minerals like platinum, even mining lunar ice, which some suggest could be converted into rocket fuel, would require a vast and unfeasible amount of energy.

Still, these conversations have been a long time coming and are far from resolved. In fact, many of the concerns that sparked the creation of the Moon Treaty were raised by countries that had suffered under colonial rule. “A lot of those advocates for the Moon Treaty were coming from the Global South … and had direct experience with the exploitation of mineral resources in their own home countries,” says Muir-Harmony. The treaty was originally signed by seven countries — Austria, Chile, France, Guatemala, Morocco, the Philippines and Romania. Today, only 18 countries have fully adopted it. “Conversations about the moon and how humans should explore the moon are really closely aligned to these debates about the power structures that have occurred on Earth and whether or not those should be

exported to the moon and other celestial bodies,” adds Muir-Harmony.

While the Artemis Accords don’t mention the Moon Treaty, they also don’t propose any change from the Outer Space Treaty regarding strict international regulation around commercial activity or resource extraction. In an executive order accompanying the U.S. signing of the Accords in 2020, former President Donald Trump called the Moon Treaty “a failed attempt at constraining free enterprise.”

Weinzierl believes that exporting our problems into space is a danger, from unequal access to resources to power struggles between nations. But in some ways, it would be better if there were true property rights in space. “If you don’t have some sort of private property rights, it’s really hard to incentivize the development of markets,” he says. Not regulating a market like this could spark more problems, such as unequal access to resources. These resources might include minerals, water and gases, but also access to the cosmic matter these resources are extracted from.

Still, all of that can seem a long way away. As of February, the world’s first privately owned moon lander has been officially declared inactive after it tipped over upon landing. SpaceX and Blue Origin haven’t carried passengers to the moon or Mars, and asteroid mining companies haven’t brought back any resources. For now, space still belongs to everyone and no one, and buying up what it has to offer, whether that’s a right to study it or owning resources taken from it, will remain mostly relegated to the realm of science fiction.

Unless, of course, it becomes real.

JUNE 2024 27

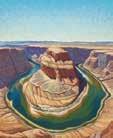

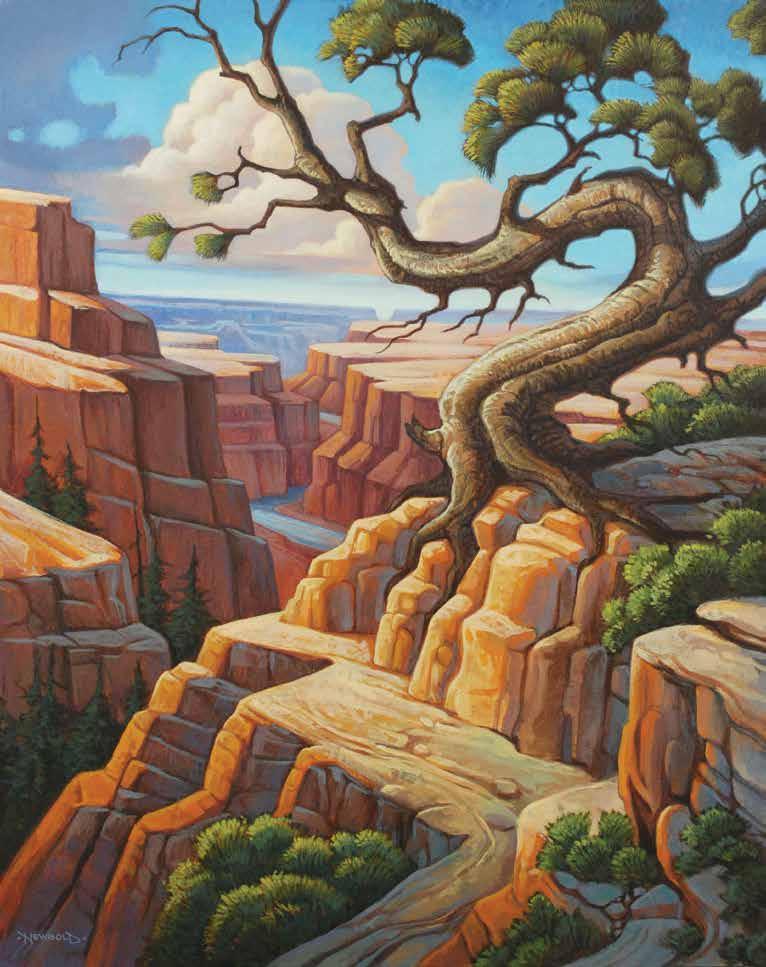

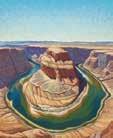

GLORY TO THE GRAND

WHY THE CALL OF THE WILD PERSISTS

BY HEATHER HANSMAN

Eight miles into the Grand Canyon, legs flung over the front tube of the raft, I was still dry, gaping at the way 40 million years of geologic history have compressed into a few thousand feet. Watching the sky shrink as the walls got higher, I was lulled into a kind of complacency by the heat and the river’s rhythm. Then came the drop into the edge of Badger Creek Rapid. A wall of water washed over the front of the boat, stopping us, soaking us and spitting us out. A river can change your mind pretty fast.

I’ve been a river runner since I was an 18-year-old rookie raft guide, stringy-armed and reedy-voiced. In a boat, I learned that rivers give you power, but only once you find the line between holding your angle and falling into the flow — an act easier said than done. Moving downstream lets you feel connected to everything around you. That’s a feeling I’ve been chasing ever since, numinous and hard to name.

I am 40 now, and sometimes I feel far from the person who went to the river that first time, ready to dive into the unknown. Now, I have a mortgage and a garden. I have achy, stitched-together joints, and I

sit in front of a computer most days. My life feels too soft, too superficial, too fast and smooth. I’d been missing that edge and missing the river.

So I signed up to be a swamper, a glorified intern on a commercial trip, working for free because I’d given myself the idea that the best place to re-immerse myself

MY LIFE FEELS TOO SOFT, TOO SUPERFICIAL, TOO FAST AND SMOOTH. I’D BEEN MISSING THAT EDGE AND MISSING THE RIVER.

was here, in the Grand Canyon, the pinnacle of American river trips. I wanted to see if I could still be the girl who would throw herself into the waves, watching the bubble line for clues. I wanted to remember why it felt so good, and I’d decided this was the place. That first splash brought me back.

If you were just to look at geographic stats, the Grand Canyon might not seem that grand. It’s not the biggest canyon in the world, nor the deepest or the longest. It’s not even the biggest canyon in its own basin; Desolation Canyon upstream is deeper. But here, the razor blade of the river cuts through a billion-year history of rock, revealing all of our existence and more.

Humans have used the Grand Canyon for 13,000 years, since the last ice age, and the river flows through the region’s cultural history. “Our ancestors had always told us not to forget that the middle of the river is the backbone of the people,” Hualapai tribal member Loretta Jackson-Kelly told the Grand Canyon Trust. “Without the backbone, we cannot survive.” Hualapai say the native fish in the river are their ancestors; everyone says that the water is life.

Hopi say that a boy named Tiyo, who was searching to understand the river, was the first person to travel down the San Juan and Colorado rivers, into the Sea of Cortez. He returned with the story of the rain dance and helped break a long drought. Colonial Western history pegs the first

28 DESERET MAGAZINE THE WEST

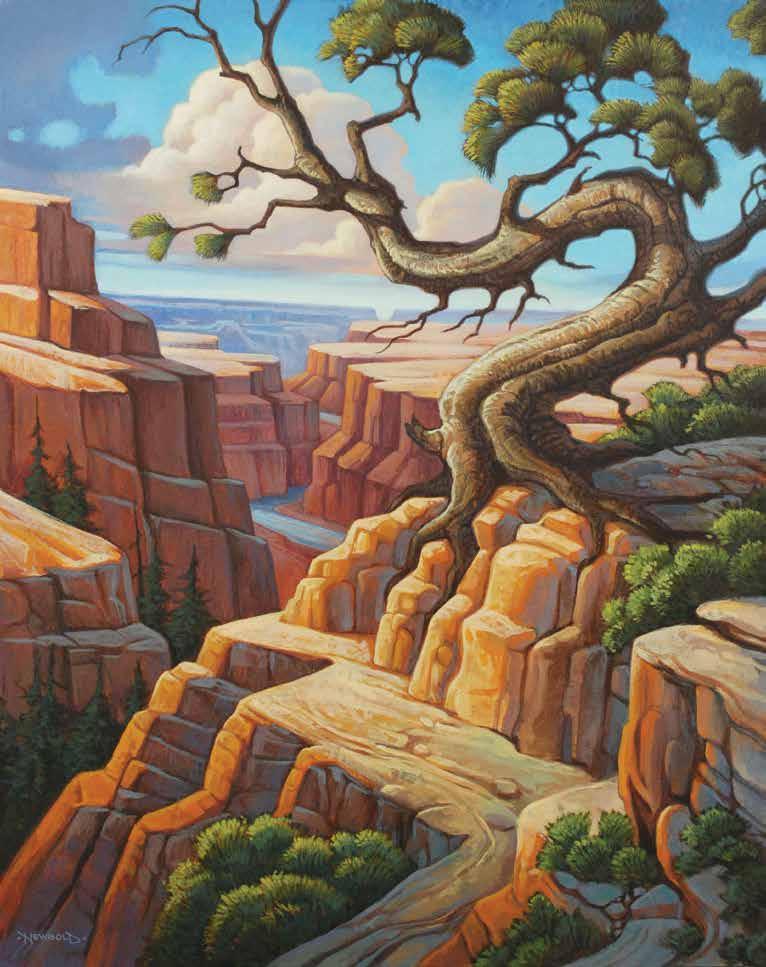

JUNE 2024 29 ILLUSTRATION BY GREG NEWBOLD

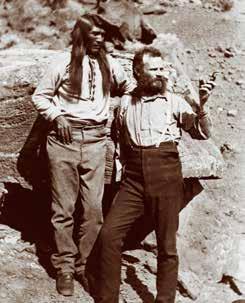

successful trip through the Grand Canyon as the Powell Geographic Expedition of 1869. Before Maj. John Wesley Powell led a group of nine men down the Green and Colorado rivers, recording the geology and geography along the way, the canyon was the last great unmapped section of the country. From their perspective, no one had ever made it through alive before. Powell lost three men along the way, but he made it back with maps.

Whichever story you hold true, the common ground is that there weren’t many people floating the river before the middle of the 1800s, and it took another 100 years for anyone to do it with any regularity. The Colorado River through the Grand Canyon was epic, dangerous, beautiful.

It became a touchstone for why we go to wild, adventurous places, and the harms we enact when we do. The curve of recreation in the country is mapped out here, from exploration to attempted extraction to a rush of adventure.

But even with that focus on action, Nikki Cooley, the first-ever Navajo river guide, says we can’t think of it like a theme park. The river, which is dammed above and below the canyon, is a fragile, frangible place: It’s in a national park, heralded as pristine wilderness. But it’s also severed by those dams, threatened by mining and drought — hoisting a patchwork of adaptive management plans and the misplaced good intentions of past lives up between it all. The river is the backbone of so much, and rafting is a way through.

ON THE WATER, days become ritualistic: the hours on the water, the thunk of oars, the Zen work of unpacking and repacking your home every day on a different slanted beach. Morning stretching, afternoon hikes up side canyons, evening drinks, the way we all grip tight when the rapids ramp up. The river moves in an S-curve south and west. Every night we are deeper in. Every day I see something I didn’t even know to look for.

The only other time I’ve been here in the gut of the gorge, I was running rim to

rim to rim, down to the river, back up, then reverse. On the trails down from the rim, you cut a quick line through all the layers, feeling yourself drop down through time, and then pulling yourself back up. Now I’m moving on the other axis, through instead of across.

In a boat, you move at the pace the river sets, the canyon unspooling in front of you, layer by layer, changing color and pitch. In the slow water days, like when we float through Furnace Flats, time compresses, and I have time to read about the people who came through before me.

The first women to successfully make it through the canyon weren’t looking for thrills or isolation; they were looking for plants. Lois Jotter and Elzada Clover, two

botanists from the University of Michigan, were trying to record unknown species. Clover had met Norm Nevills, an early river guide, on a previous research trip. Nevills, who had been running other rivers in the basin, had never seen the Grand Canyon before, but he wanted to, and he wanted attention for it, so together they hatched a plan to paddle through. Their trip became a precedent for the future: in the way they ran the river, in the biological record they captured, in the fact that women could handle the canyon — an idea that had previously been dismissed. Journalist Melissa Sevigny, who recently wrote a book about their groundbreaking trip, “Brave the Wild River,” said the two were surprised by how powerful the river was, but they were also

30 DESERET MAGAZINE THE WEST

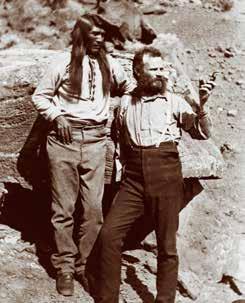

CLINE LIBRARY, NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIVERSITY

shocked by its beauty and range. They thought the river might be “barren and hellish,” but instead, they cataloged 400 species of plants. “Clover wrote about how she’d been told the canyon was this dark, gloomy place,” Sevigny told me. “I think she fully expected to experience that, but found it not to be the case — she formed a very deep connection with the canyon and the river and wrote eloquently of its beauty.”

The trip changed their perception of the place, and their perceptions of themselves. Years later, Jotter — who, among other feats, spent a night stranded alone on a high water beach — would still talk about the boost of confidence that came from facing the river, and her own capabilities in the face of it.

I am a little jealous of that trip, and of how much was unknown when they set off. In some ways, that feels far away right now, when nearly everywhere is mapped, geotagged, Google-able. But you can never really know a rugged place, or know how you’ll respond, until you’re in it, shoulders and hands hardening, a form of personal erosion. To learn what Jotter did, I think you have to feel the friction in your body. By the end of the first week, I have heat rash and Velcro fingertips. New muscle deep in my elbows aches from rowing, and layers of my skin slough off, exfoliated by the spackle of sunscreen and sand. Sometimes the wind blows so hard that we’re basically floating backward. We carry on, somewhere between uncomfortable and entranced.

When we spend a night at Big Dune Camp, the river, which had been clear and greenish from dam runoff, turns red from flash flooding. It runs thick, the color of terra cotta. It’s how the river would have been before the dam went in and held back all the sediment behind its walls.

Sand is the story of how the dam stops time, changes the ecosystem, strips it bare. Even this camp is a remnant of the unnatural balance struck between these walls.

Last spring, after a big winter of snow, the Bureau of Reclamation decided to conduct what it calls a high flow experiment.

The bureau sent a big pulse of water out of Glen Canyon Dam, intending to mimic historic high flows. That water ripped through the canyon, flushing out debris, setting off native fish spawning cycles, and rebuilding beaches, including the eponymous big dune here. It’s been destroyed and poorly rebuilt by hydraulic engineering, as has so much else in this protected canyon we hold up as the highest level of wilderness. It’s one thing to know that, intellectually. It’s another to see it happen. When you’re outside in a landscape where you can feel the erosion and see the river change, you’re forced to confront it. Contact leads to understanding and incentive to take care of the place. It makes it real. The grit makes the good parts shine.

One midmorning, we hike into a waterfall up clear blue Shinumo Creek. We dive under the spray, swimming into the cool green cave behind the falls, rinsing the grit out of our hair and our eyes. Tiny threatened native humpback chub tickle our toes. They have a stronghold here. It seems like every side canyon holds a secret or a story like that. I think you could come through a

SINCE 1996, RELEASES FROM GLEN CANYON DAM (PICTURED) INTO THE GRAND CANYON HAVE GENERALLY RANGED FROM 8,000 TO 25,000 CUBIC FEET PER SECOND, CONSTANTLY CHANGING THE FLOW AND CONDITIONS OF THE COLORADO RIVER.

OPPOSITE: LOIS JOTTER AND ELZADA CLOVER, TWO BOTANISTS FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, WERE THE FIRST RECORDED WOMEN TO HAVE PADDLED THE COLORADO RIVER THROUGH THE GRAND CANYON.

JUNE 2024 31

GETTY IMAGES / JEFF TOPPING

million times and still keep stumbling on newness. It’s not just the rapids and the big water rush that make it magic, like I had thought it might. Instead, it comes from the details and from having the time to let them sink in.

PSYCHOLOGICAL RESEARCH HAS found that feeling small and independent in a big place is good for our brains. A 2018 study from UC Berkeley found that awe, more than any other positive sensation, gives us a full spectrum sense of well-being, which can help people recover from PTSD, anxiety and a wash of other stressors. The Berkeley researchers monitored the stress hormones of veterans and at-risk teens who spent time outside and found that stress hormones significantly lowered when they were on river trips.

The awe sneaks up on you. It’s the weight of the oar in my hand and how I learned the river by figuring out the feeling of water on a blade. It’s how I now know what bighorn sheep look like silhouetted on the ridge, the ram in full curl. And how I know what happens when you follow the track of a tiny scorpion and find it under a rock, translucent and mad. It’s that balance of working hard and letting go. Meeting the river and letting it move you.

Once you get addicted to that alchemy, you are never far from the canyon in your mind. There will be rapids running through your dreams, cutting through tapeats and travertine. Some people get it so bad that they’re always trying to get back, unable to let go, sucked into the mythology and the movement.

“OUR ANCESTORS HAD ALWAYS TOLD US NOT TO FORGET THAT THE MIDDLE OF THE RIVER IS THE BACKBONE OF THE PEOPLE. WITHOUT THE BACKBONE, WE CANNOT SURVIVE.”

People and their stories stipple the myths. Nels Niemi, who died in October, rowed it 178 times, starting in 1967. In the days before the National Park Service started regulating trip length, he spent over 100 days straight on the river, connecting the Snake, the Green and the Colorado, making a home of the canyon. He’d been down there so much he knew exactly where to find sun in December.

Seth Mason, a member of the U.S. men’s rafting team who made several attempts to set the speed record through the canyon, says the team spent obsessive years training, trying to memorize every rapid so they could run it in the dark. “For us, the pull had a lot to do with the lore and this rich history of people chasing crazy ideas down there,” he told me.

They didn’t break the record. One time, the flows weren’t high enough. On another attempt, they busted up their boat at Lava Falls, mile 179 of 277, trying to run through the gnash of whitewater in the dark. A reminder that the river is in charge.

The rapids aren’t necessarily the best part of the river, but they keep you honest. All trip, I had an underlying stomach churn about the biggest rapids: Crystal and Lava

Falls, wondering how they would go. Lava is the last big rapid and it looms over everything. There’s an adage in the Grand Canyon that you’re always above Lava, even off the river.

I’d been worrying, and then suddenly we were above it. Standing at the scout for the rapid, watching the water pile up over the thundering ledge hole at the top, funnel down toward the Big Kahuna wave and slam the Cheese Grater rock on the right. Some of the famous rapids in the Grand aren’t tricky, they’re just big, but Lava is both technically difficult and huge. It’s the epitome of the river’s power. You can feel the force from shore. And you have to make it through Lava to make it through the canyon.

We ran left at Lava, hitting the edge of the guard wave at the top and then skirting the edge of the huge central hole. Our boat captain, Kelly, pushed hard on the oars, punching through the huge sloshing waves to the end till we came out clean. I rode the bull on the nose of the boat, clenching the chicken line with both hands, screaming, laughing in the troughs of the waves. Feeling that teenage rush moving through me once more.

And then, just like that, we were above Lava again, regrouping on the beach below, already thinking about next time. Wrung through a range of emotions, lit up and feeling it all: the aliveness and ache, the alignment of all things, the focus. We were buzzing down to our toes. “The Grand Canyon is not just a joy ride. It is an entity,” Niemi once said in the Boatman’s Quarterly Review.

I understand why you’d want to be here hundreds of times over, and I think that rush and release is a worthy thing to chase. Science, like that Berkeley study, backs that up, and so do the lessons of our lives. It doesn’t necessarily have to be here, in this particular canyon, but there’s some sort of need for wild places, disconnection, sand between our teeth, to feel alive and part of the flow. It can’t last forever. In a week I’ll be home, back in the garden, the emotional antipodes of the Grand. But I’ll still have the grit on my skin.

32 DESERET MAGAZINE

THE WEST

© CORBIS/CORBIS VIA GETTY IMAGES

SOUTHERN PAIUTE CHIEF TAU-GU (LEFT) AND MAJ. JOHN WESLEY POWELL CONDUCTING WORK FOR THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY IN 1870.

Located 10 minutes from downtown Salt Lake City is a Utah State Park with the perfect venues to set your team up for success all year round! With eleven inspiring, tech enabled spaces, we have the ideal venue to fit your corporate needs. Rooms for breakout gatherings, spaces for over 500, free WiFi, trail rides for team building, a variety of catering options, and free and easily accessible parking. This Is The Place for your business!

IS

BUSINESS

THIS

THE PLACE FOR

BOOK YOUR VENUE TODAY! ThisIsthePlaceForBusiness.com or 801-924-7507

AMBOS NOGALES

WHERE THE BORDER DOESN’T DIVIDE PEOPLE — IT UNITES THEM

BY NATALIA GALICZA

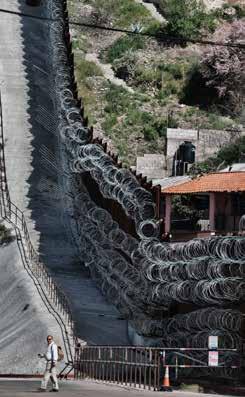

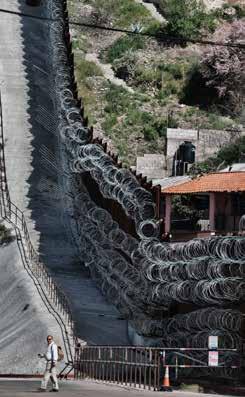

Sunlight hits the desert scrub just beyond a cleft in the steel wall that divides the two cities of Nogales — one in the United States and the other in Mexico. It’s strange seeing a single trace of light in a land that is often awash with the sun, but at just the right time in the morning, it creeps in and bursts through the border wall’s gap, funneling out the other side, appearing almost miraculous.

The things the light cannot yet touch are strewn about, like offerings in front of the wall. Coils of concertina wire. Abandoned blankets and beanies coated in the frost of the desert’s dark. An empty glass jar of baby food. Telephone cards. A small book — “Guía Práctica para el Rezo del Santo Rosario” — which translates to a “Practical Guide to Praying the Holy Rosary.” These left-behinds likely belonged to migrants who cut through the Arizona-Mexico border in search of asylum by way of this gap in the wall, known as the “Mariposa Slab.” For many state and federal politicians — including both candidates in the upcoming presidential election — it also represents the core of a national problem.

All ports of entry in Nogales fall under the Tucson Sector of the United States Customs and Border Protection, which covers about 260 miles east to west — some of the busiest territory in America for illegal crossings and drug seizures. Recently, it’s

DESPITE THE ALL-EYES-ON-IT ATTENTION BEING PAID TO THE POLITICS OF THE BORDER, LITTLE IS GIVEN TO THE LIFE LIVED — AND SHARED — IN BORDER COMMUNITIES MOST IMPACTED BY POLICY.

become even busier. There were 80,814 reported migrant apprehensions in the Tucson Sector last December, a 262 percent increase from the previous year. That historic surge prompted President Joe Biden to begin building closures along the

border, despite campaigning on a promise that he wouldn’t add “another foot” to former President Donald Trump’s wall construction. Some ports closed altogether out of overwhelm — like the Lukeville Port of Entry, about 200 miles west of Nogales, which shut down for a month in December. The number of migrant apprehensions has ebbed and flowed since. Tucson Sector totals neared 42,000 in March tamped down by increased surveillance on both the Mexican and American side of the border that came as a direct response to the December rush. But despite the recent dwindle, border crossings are expected to rise again, and they remain a focal point in the lead-up to the 2024 presidential election.

A bipartisan bill pushed by Biden in Congress this year would have permitted the government to shutter the border if more than 5,000 migrants crossed it illegally in a single day. For reference, last year brought some one-day totals of more than 10,000. The bill died in the Senate after Republican House leaders pointed out loopholes that would prevent shutdowns and give too much authority to Homeland Security

34 DESERET MAGAZINE

LETTERS FROM THE FIELD

ABOVE: THE DOWNTOWNS OF NOGALES, SONORA, AND NOGALES, ARIZONA, FACE ONE ANOTHER — A RARITY FOR BORDER TOWNS.

LEFT: BORDER CROSSINGS HAVE GOTTEN INCREASINGLY BUSIER IN THE PAST TWO YEARS, BUT BUSY IS THE NORM IN NOGALES, WHERE 15,000 PEOPLE CROSS BOTH WAYS EVERY DAY.

JUNE 2024 35 AP PHOTO / RODRIGO ABD

GETTY IMAGES / JOHN MOORE

A MAN WALKS PAST THE RAZOR-WIRECOVERED BORDER WALL THAT SEPARATES NOGALES, ARIZ.,

Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, but it lives on as a campaign point for Biden. In February, the same month Biden’s bill failed, House Republicans voted to impeach Mayorkas in an unprecedented move that was dismissed by the Senate two months later. Each of these opposing steps, made in the name of immigration reform, have ended in gridlock. Democrats are currently scrounging for an alternative plan to replace the defeated bill as all-eyes-on-it attention is on the politics of the border and the migrants who cross it. Yet little attention is paid to the life lived — and shared — in border communities most impacted by changes in policy.

It is in these small communities where the wall is not seen as a symbol of literal and political division, but a doorway that connects rather than separates. “Most of the people who are crossing the border in Nogales, they are locals who have border crossing cards or a special type of visa for binational residents, and they do it every day,” says Ieva Jusionyte, a legal and medical anthropologist who teaches international security at Brown University. “The border depends on circulation.” Nogales, the “gateway to North America,” demonstrates that neither Mexico nor the United States is a monolith — and that the intersection of the two is more of an interconnection.

IN NOGALES, SONORA, colorful homes are scattered like confetti among tawny hills. There’s a rhythm and bustle of passersby beyond the turnstile at the Dennis DeConcini Port of Entry in downtown Nogales, Sonora. This city is far larger than its Arizona counterpart, with some 265,000 people compared to 20,000.

Dental and medical offices pepper the streets. There’s “Dental Laser Nogales,” “West Dental,” “Nogales Dental Advanced” and “Arizona Dental Nogales,” each only about five minutes apart. A chorus of storefronts advertise services for Americans in search of cheaper health care — mostly in English. Many even accept American insurance. The familiarity is enough to create the illusion that one did not cross an

international border. In truth, much of the city’s downtown is catered to tourists, medical or otherwise. Cow skulls, embellished cowboy boots, sombreros, wrought-iron sculptures and tiny bobblehead turtles perch on shelves and are placed hopefully in front of shop doors.

Part of this focus on American visitors is the undeniable boon of their USD-fueled business. The Mexican city of Nogales brings in more than $450 million in international sales annually. More than 100 manufacturing plants, exporting goods from computers to car parts, contribute the majority of that revenue. The rest relies on steady foot traffic crossing the border. “The majority of clients are Americans here, about 70 to 80 percent,” says Silvestre Castro, the head waiter at La Roca, a restaurant a quick walk from the port. (He’s worked there for 30 years. Every day, he wears an ironed suit and tie to wait on American customers — which he says is his favorite part of the job.) Luz Amelia, who owns the Panadería La Espiga de Oro bakery less than one mile from La Roca, tells a similar story. “A lot of Americans come to the bakery and bring the bread back home as far as Phoenix or Las Vegas,” she says. Amelia orchestrates the orders from behind the counter, with an open binder of decals and designs for custom cakes in front of her while a line of customers clutching their pastries wait to pay with both Mexican pesos and American dollars.

For all the merchants in Sonora who count on sales to Americans, locals in the U.S. are arguably even more dependent on tourists who cross north into Nogales, Arizona. When the pandemic shut down the border, Evan Kory called it a worst-case scenario. The shoe store and bridal shop his family owns on Morley Avenue, La Cinderella and Kory’s Bridal, lost as much as 30 percent in sales. They couldn’t afford to hire employees, so family members took on shifts, keeping the stores open for a few hours at a time.

The shops fully reopened in 2021, offering the family a much-needed financial reprieve until the Lukeville border closed

36 DESERET MAGAZINE

LETTERS FROM THE FIELD AP PHOTO / RICHARD VOGEL

LEFT, AND NOGALES, SONORA, RIGHT, ON MARCH 30, 2019.