deseret.com $4.95 MAY 2024 VOL 04 | NO 34 REFERENCE MAY OCTOBER A DISNEY GIRL IN A DISNEY WORLD ARE RELIGIOUS PEOPLE REALLY HAPPIER? DETOUR FROM DEMOCRACY THE 2024 ELECTION � S POISON PILL SAVING THE GREAT SALT LAKE

Learn more about our work at MothersWithoutBorders.org/hope GIVE EMPOWER CREATE HOPE

40 A PLACE OF REFLECTION

THE PERSONAL SIDE OF PRESERVING THE GREAT SALT LAKE.

by

chris carlson

DETOUR FROM DEMOCRACY

THE CONSTITUTIONAL FLAW THAT COULD TRIGGER A CRISIS IN NOVEMBER. by ethan

bauer

“Will ‘the most dangerous blot in our Constitution’ prove to be as fatal as Jefferson feared?”

MAY 2024 3 CONTENTS ON THE COVER PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRIS CARLSON

52 A DISNEY GIRL DEMOCRACY GREAT

“I get defensive when people refer to parts of the West as flyover states.”

joshua dubois

MAY 2024 5 CONTENTS

SPEAKING OUT WITH GRACE Calling out the wrong when we see it. by

17 OUT OF OFFICE

a four-day workweek help or hurt us? by

18 DON’T TELL MOM The one family conversation I’m fine with being left out of. by jennifer graham 22 GRIEF SHARED How grief can bring us together, if we allow it. by samuel brown 62 THE VOICE MACHINE How we teach English to AI could backfire. by glynnis macnicol 70 IN PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS The data has spoken: The religious are happier. by stephen cranney 66 THE NEGOTIATOR Life lessons from the bargaining table. by lois m . collins 80 TERRACE by paisley rekdal 79 DISNEY GIRLS Why moms and daughters love the Magic Kingdom. by meg walter 74 WHAT A PIECE OF ENGINEERING! An ode to the typewriter. by joe marotta 76 THROUGH THE LENS One photographer’s journey to discover what makes the West special. by natalia galicza DON’T CALL IT A GHOST TOWN A journey into a forgotten American utopia in the Amazon. by eléonore hughes 36 SOBER MINDED Turns out, young Americans just aren’t into drinking these days. by anneka williams 26 BOARDING PASS High-speed trains come to the American Southwest. by ariana donalds 20 COMMENTARY POINT/COUNTERPOINT LETTERS FROM THE FIELD IDEAS IDEAS THE LAST WORD POETRY CULTURE ODE NATIONAL AFFAIRS MODERN FAMILY BREAKDOWN THE WEST 30

Would

natalia galicza

DuBois, CEO of Values Partnerships, led the White House Office of Faith-based and Neighborhood Partnerships under President Barack Obama. A frequent media commentator, he authored “The President’s Devotional: The Daily Readings that Inspired President Obama.” His commentary on speaking out with grace is on page 17.

Williams is a writer and climate scientist who has pursued stories and work in Chilean Patagonia, Copenhagen, Bhutan and the Alaskan tundra. Her work has been featured in Backcountry Magazine, Powder Magazine and The Dirtbag Diaries. Her story about why young people are drinking less is on page 26.

Hughes is a Franco-British journalist living in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where she covers politics and social and environmental issues for The Associated Press and Le Figaro. Before moving to Brazil, she lived in Paris, where she worked for Agence France-Presse. Her story about the failed utopian community of Fordlândia, Brazil, is on page 36.

MacNicol is a writer and podcaster whose work has been published in The New York Times, The Guardian, The Cut and New York magazine, among others. Her latest book, “I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself,” will be published this summer. MacNicol’s essay on how AI can dictate our worldview is on page 70.

A former Utah poet laureate, Rekdal teaches at the University of Utah, where she directs the American West Center. Her most recent book of poetry is “West: A Translation,” which was longlisted for the National Book Award and won the 2024 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award. A poem from that book is on page 79.

Cranney is a data scientist and social science researcher based in Washington, D.C., where he also teaches at the Catholic University of America. A nonresident fellow at Baylor University’s Institute for the Studies of Religion, his work has been published in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion and other peer-reviewed publications. His essay on the relationship between religion and happiness is on page 66.

6 DESERET MAGAZINE CONTRIBUTORS

JOSHUA DUBOIS

ELÉONORE HUGHES

PAISLEY REKDAL

ANNEKA WILLIAMS

GLYNNIS MACNICOL

STEPHEN CRANNEY

THIS IS THE PLACE FOR BUSINESS

Located 10 minutes from downtown Salt Lake City is a Utah State Park with the perfect venues to set your team up for success all year round! With eleven inspiring, tech enabled spaces, we have the ideal venue to fit your corporate needs. Rooms for breakout gatherings, spaces for over 500, free WiFi, trail rides for team building, a variety of catering options, and free and easily accessible parking. This Is The Place for your business!

BOOK YOUR VENUE TODAY! ThisIsthePlaceForBusiness.com or 801-924-7507

JEFFERSON’S WARNING

When the founders gathered in Philadelphia to draft the Constitution, they debated for months to decide how a president should be elected. At first, they liked the idea of Congress picking the president — as the British Parliament chooses the prime minister — but discarded that proposal over concerns it would lead to corruption between the executive and legislative branches.

Eventually, they settled on a little-known compromise called the “contingent election,” which has been mostly ignored by our history books. If no candidate emerges from the Electoral College with an electoral majority, the outcome is decided by the House of Representatives, where each state delegation gets one vote. Thomas Jefferson believed this was “the most dangerous blot in our Constitution, and one which some unlucky chance will some day hit.”

Fortunately, we haven’t come close to a contingent election since 1824, when John Quincy Adams won the presidency over populist Andrew Jackson. But as distant as it may seem, a contingent election is a real possibility this fall, at a time when confidence in American democracy is already fraying. As Ethan Bauer details on page 52, this could be a dangerous mix. “With just 16 percent saying they trusted the government in 2023, a contingent election could be the poison pill embedded in the U.S. Constitution that causes the rest of the electoral system to fail.”

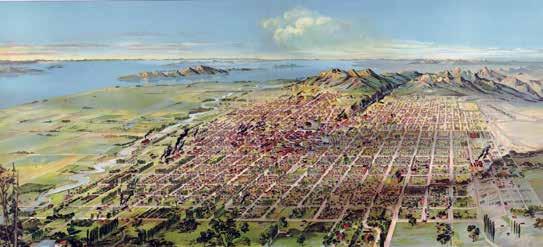

With so much at stake this election season, we’re making a special effort at the magazine to focus on what truly makes America great. In that vein, this month’s cover story highlights the Great Salt Lake in a gorgeous photo essay by Chris Carlson. When I met with him to see his photos for the first time, I was inspired by the spiritual connection he feels with this endangered natural wonder. He told me how his ancestors were among the first white settlers to build homes on Antelope Island. Now, he hopes his work, which begins on page 40, will spur others to take action while the vanishing lake can still be saved. “Walk the shores,” Carlson implores. “Listen to the stories. See the beauty. Witness the plight.”

We love this land and believe in the institutions dedicated to preserving our democracy, but every good fight starts with good people. As I’ve noted in this space before, one important way to help is by listening respectfully to those who hold opposing views. But as Joshua DuBois points out in this month’s Commentary on page 17, that doesn’t mean compromising our deeply held beliefs. In fact, sometimes it requires the courage to call out what we see as wrong. “We need an active, lived civility that is not quiet,” DuBois writes, “that doesn’t take a backseat, but leans into the healing of this country.” I like to think our forebears — from Mason to Jefferson and Carlson’s pioneer ancestors — would agree.

—JESSE HYDE

MAY 2024 9

THE VIEW FROM HERE

EXECUTIVE EDITOR HAL BOYD

EDITOR

JESSE HYDE

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

ERIC GILLETT

MANAGING EDITOR

MATTHEW BROWN

DEPUTY EDITOR

CHAD NIELSEN

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

JAMES R. GARDNER, LAUREN STEELE

POLITICS EDITOR

SUZANNE BATES

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

DOUG WILKS

STAFF WRITERS

ETHAN BAUER, NATALIA GALICZA

WRITER-AT-LARGE

MICHAEL J. MOONEY

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

SAMUEL BENSON, LOIS M. COLLINS, KELSEY DALLAS, JENNIFER GRAHAM, MARIYA MANZHOS, MEG WALTER

ART DIRECTORS

IAN SULLIVAN, BRENNA VATERLAUS

COPY EDITORS

SARAH HARRIS, VALERIE JONES, CHRIS MILLER, HANNAH MURDOCK, TYLER NELSON

DESERET MAGAZINE (ISSN 2537-3693) COPYRIGHT © 2024 BY DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. IS PUBLISHED MONTHLY EXCEPT BI-MONTHLY IN JULY/AUGUST AND JANUARY/FEBRUARY BY THE DESERET NEWS, 55 N 300 W, SUITE 400, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH. TO SUBSCRIBE VISIT PAGES.DESERET.COM/SUBSCRIBE. PERIODICALS POSTAGE IS PAID AT SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH

POSTMASTER: PLEASE SEND ADDRESS CHANGES TO PO BOX 2220, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH 84101.

DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO.

PUBLISHER BURKE OLSEN

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER ERIC TEEL

VICE PRESIDENT MARKETING

DANIEL FRANCISCO

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT SALES

TRENT EYRE

VICE PRESIDENT SALES SALLY STEED

PRODUCTION MANAGER MEGAN DONIO

OPERATIONS MANAGER

BRITTANY M C CREADY

DIRECTOR OF CIRCULATION

SYLVIA HANSEN

DESERET NEWS’ PRINCIPAL OFFICE IS

SALT LAKE

UTAH. COPYRIGHT 2024, DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA.

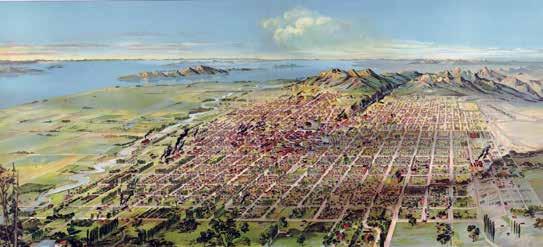

DESERET

PROPOSED AS A STATE IN 1849, DESERET SPANNED FROM THE SIERRAS IN CALIFORNIA TO THE ROCKIES IN COLORADO, AND FROM THE BORDER OF MEXICO NORTH TO OREGON, IDAHO AND WYOMING. INFORMED BY OUR HERITAGE AND VALUES, DESERET MAGAZINE COVERS THE PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF THAT TERRITORY AND ITS INTERSECTION WITH THE BROADER WORLD.

12 DESERET MAGAZINE

DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE AMERICAN EDUCATION THE PATHWAY AN ODE TO THE TRAMPOLINE AWARD-WINNING JOURNALISM ABOUT THE PLACE WE CALL HOME SCAN HERE TO SUBSCRIBE DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE MILITARY SPENDING — BAILOUT OR FALLOUT? BAD BETS CALIFORNIA EXODUS THE OTHER MARCH MADNESS DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE JUNE 2023 THE FAITH OF MIKE PENCE COLORADO RIVER TIPPING POINT? DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE MITT ROMNEY ON E NATION UNDER GOD? JFK CONSPIRACYDESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE ABBY COX STATE WEST OF THE NAVAJO NATION

400,

THE

55 N. 300 WEST, STE

CITY,

OUR READERS RESPOND

Our MARCH cover story examining what’s behind the exodus of people and businesses from the Golden State (“What’s the Matter with California?”), by Natalia Galicza, ignited a passionate debate that revealed the love-hate relationship people have with the state. But many readers, like Mark Holley, came to California’s defense. “I moved to Southern California from Utah 12 years ago. I won’t ever leave. I’ve found that people who have never lived here have the most negative things to say about it, which is interesting because they actually know the least about California. There are tons of issues here that need fixing — but the same can be said for Utah or anywhere else.” Ethan Bauer’s analysis of how sports betting is changing the stakes of the game (“Big Risks and Bad Bets”) proved timely as other national media outlets like The Associated Press and The New Yorker focused on the issue the same month that a betting scandal broke in Major League Baseball. Les Bernal, national director of Stop Predatory Gambling, recommends Bauer’s piece. “I’ve read almost every story on sports gambling in the U.S. over the last five years and yours was one of the very best. Excellent insight and analysis.” And it sparked this thought from reader Ron Stamm on the influence betting could have on those directly involved in the outcome of an athletic contest. “The high stakes involved may put players, coaches and officials in jeopardy — either through threats or the temptation of under-the-table cash — to influence the outcome.” In that same month, the Academy Awards honored films that interpreted the past, prompting Bauer to explore whether having Hollywood telling us how to think about our own history is a good thing (“Rewritten”). Reader Todd Richardson is OK with it as long as filmmakers who call their work educational and inspiring don’t hide behind the excuse of mere entertainment when they misfire or mislead. “It’s both or it’s neither,” Richardson argues. “Can’t have it both ways.” A film that took home multiple awards (“Oppenheimer”) told the story of the first atomic bomb blast — the Trinity test in New Mexico. The ongoing fallout from that explosion framed Matthew Brown’s story about how the U.S. military has shaped the economies of the West, for better or for worse (“Shell-shocked”). While readers debated whether the government should compensate those living downwind from radioactive fallout of nuclear testing, Taylor Barnes, field reporter for the military watchdog website Inkstick, had this to say: “Really superb piece on the costs/benefits of nuclear weapons spending in local economies in the American West.” An excerpt of Ruy Teixeira and John Judis’ new book on how the Democratic Party lost its core bloc of working-class voters (“The Elites”) elicited this response from reader Ron Richey: “I believe that there is room for a new political movement that tracks with the traditional conservative values of religious expression and freedom, prosperity through manufacturing and innovation, and the value to our society of solid working-class prosperity.”

“I’ve found that people who have never lived here have the most negative things to say about it, which is interesting because they actually know the least about California.”

MAY 2024 13

THE BUZZ

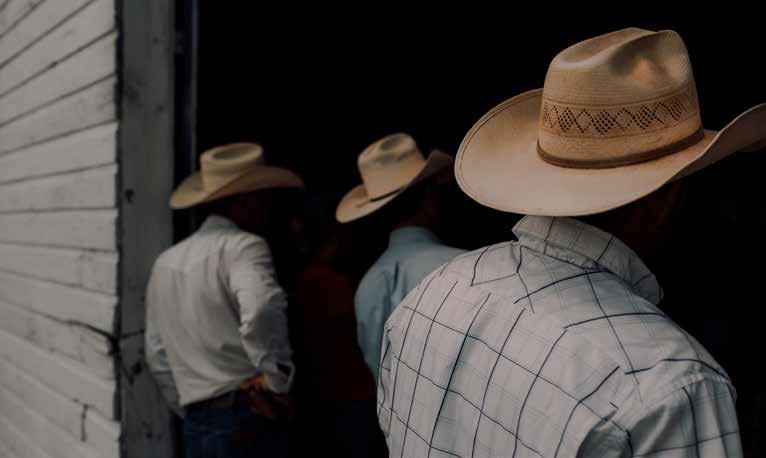

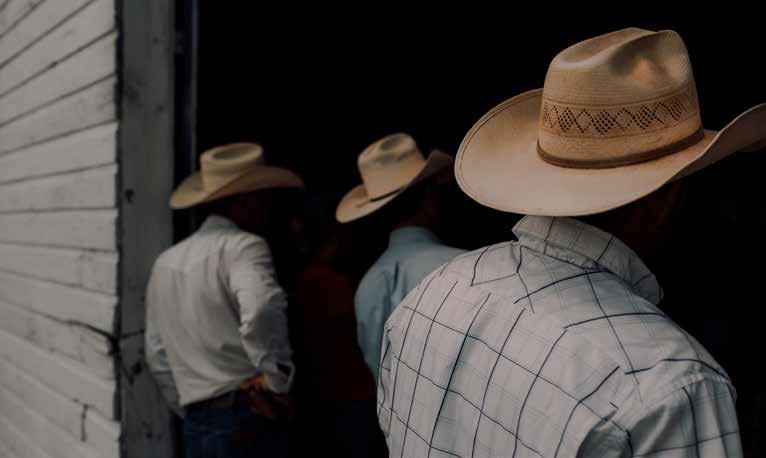

14 DESERET MAGAZINE OPENING SHOT

SADDLE MAKER

CARY SCHWARZ IN SALMON, IDAHO

PHOTOGRAPHY BY GLENN OAKLEY

MAY 2024 15

Marseli has never been more relieved, with his eyesight restored he can once again provide for his young family of six

R E S T O R I N G L I V E S

T H O U G H S I G H T

A t C h a r i t y V i s i o n w e l e a d t h e w o r l d i n h e l p i n g

p r o f e s s i o n a l s p r o v i d e h e l p t o t h e n e e d y o f t h e i r

o w n c o u n t r y . W i t h o u r m o d e l , i t o n l y t a k e s $ 2 5

t o g i v e s i g h t t o t h e b l i n d w h i l e a t t h e s a m e

t i m e i n c r e a s i n g t h e c a p a c i t y o f t h e l o c a l

m e d i c a l c o m m u n i t y . F I G H T B L I N D N E S S I N Y O U R C O M M U N I T Y T O D A Y w w w . C h a r i t y V i s i o n . o r g

SPEAKING OUT WITH GRACE

FINDING THE COURAGE TO TAKE A STAND

BY JOSHUA DUBOIS

When the president of the United States gave a speech, really as a sermon, in front of the casket of the late Rev. Clementa Pickney — who was murdered by man in a South Carolina church in 2015 — it was almost as if the most complicated and tragic parts of our common collective national story, and in some ways the most beautiful, came together in that moment. And the most radical thing I think President Barack Obama could have said in that moment is what he did say: that we all need to give and receive grace.

When I think about the state of America today, and the anger over politics, I think of people who are hurting and who are broken and who are seeking meaning in their lives. Perhaps that’s a radical thing to say about the people who descended upon the Capitol building on January 6. They were angry. And yes, they did things that require consequences. But they were also trying to fill a hole in their souls with some level of meaning. The same meaning that people on the left sought when they canceled people in the public square and maybe railed on Twitter or elsewhere. They’re all trying to scoop meaning into this hole, this abyss, and they’re doing so by demonizing someone else, by othering other people. Sometimes it becomes more acute and even becomes violent and literally kills people.

So what can faith leaders do? They can preach, share and teach the fact that the places where too many of us are building meaning are sinking sand. And they can talk about where true meaning is found. And that doesn’t have to be some bland message, some

generic message. They can call out and name the idols that people are replacing true meaning with, and then call people into something that’s more lasting and eternal.

This is going to be a deeply uncivil year, and that does not require people to be quiet. We’ve got to find that sweet spot where you can still speak lovingly, but prophetically, when you see something that you just know in your gut is wrong.

This is what the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. did. He wasn’t quiet. In fact, one of his biggest criticisms was reserved not for the most virulent racists. But, as he said in his letter from the Birmingham Jail, it was reserved for the white moderates who were so concerned with decorum and civility that they refused to speak out when they knew something was wrong.

And so I think what all of us have to do, especially this year, on both sides of the aisle, is when you know that something is just wrong, you have to say it. You’ve got to put it out there. And in my tradition you express yourself, seasoned with salt and full of the Holy Spirit, with as much love as possible, but still speaking to it. We need an active, lived civility that is not quiet, that doesn’t take a backseat, but leans into the healing of this country.

MAY 2024 17 COMMENTARY ILLUSTRATION BY KYLE HILTON

THIS ESSAY WAS ADAPTED FROM DUBOIS’ COMMENTS AT A RECENT FORUM IN THE WASHINGTON NATIONAL CATHEDRAL SPONSORED BY DESERET MAGAZINE, THE WHEATLEY INSTITUTE AT BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY AND THE WESLEY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY.

JOSHUA DUBOIS, AN ORDAINED PENTECOSTAL MINISTER, LED THE WHITE HOUSE OFFICE OF FAITH-BASED AND NEIGHBORHOOD PARTNERSHIPS UNDER PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA.

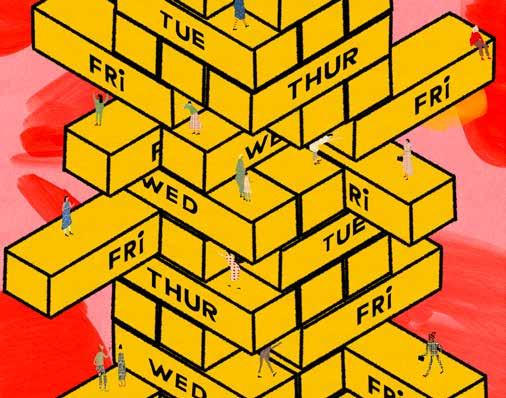

OUT OF OFFICE

WOULD A FOUR-DAY WORKWEEK HELP OR HURT US?

MOST AMERICAN EMPLOYEES still work eight-hour days, five days a week, even in the age of remote work. But many companies and governments are exploring a change, replacing that standard with the four-day workweek. The idea has gained traction from Belgium to the United Arab Emirates, from California to Missouri. Bankrate reported last year that more than 80 percent of America’s full-time workforce supports the concept. Could this be the answer to work-life balance and burnout? Or does it just create new problems?

NATALIA GALICZA

18 DESERET MAGAZINE POINT / COUNTERPOINT

BETTER BALANCE TO EACH THEIR OWN

THE FOUR-DAY WORKWEEK could be the cure for employee burnout, or mental exhaustion due to overwork. This global epidemic has made headlines since the pandemic and the rise of remote work, under terms like “quiet quitting” and “the great resignation.” According to McKinsey & Co., 1 in 4 employees around the world experience some level of burnout. Not only does this affect their mental health, it also impacts the bottom line, because they are six times more likely to quit in a matter of months, and may also have higher rates of sick days and absenteeism.

The four-day alternative offers employees more flexibility and free time, reducing the likelihood of stress and fatigue. The largest trial to date, which took place in the United Kingdom in 2022, showed that an extra day off can keep employees more engaged and healthy. Of the 2,900 workers who participated, 60 percent said the shorter week made it easier to balance their professional obligations with familial and social responsibilities. By the end of the six-month experiment, the likelihood of an employee quitting fell by 57 percent. The number of sick days used dropped 65 percent. But it also yielded a surprising outcome: Revenues rose across the 24 participating companies that provided this data.

“But it’s not just about productivity. It’s also about well-being,” said Andrew Barnes, co-founder of the nonprofit 4 Day Week Global, speaking at the MIT Sloan Management Review’s Work/23 symposium last May. The nonprofit helped conduct the U.K. study and oversees similar research around the world, including experiments in the United States. “And what we’re seeing is on broadly every single account — whether it’s workload satisfaction, stress, burnout, the time people can spend getting fit and exercising — it increased ability to have strong mental health, which is critical.”

Utah was the first U.S. state to experiment with this change for state employees, adopting a four-day, 40-hour schedule from 2008 to 2011. Mandated by former Gov. Jon Huntsman, this temporary change reduced energy consumption and carbon emissions while also saving the state close to $1 million per year.

SOMETIMES AN IDEALISTIC change can have unexpected outcomes and undesired consequences. There’s a reason Utah dropped the four-day workweek for government employees: It didn’t live up to the hype. An audit by the state Legislature found that it was saving far less than the $3 million annual number the governor’s office hoped for. Meanwhile, citizens grew dissatisfied when they couldn’t access government services on Fridays. Similarly, 55 percent of employees in a 2022 Qualtrics survey feared that a four-day workweek would frustrate their customers.

It’s not all roses for employees, either. Everybody works differently, as do different companies in different industries. Some are moving to four days using a compressed schedule — totaling 40 hours, with longer shifts to compensate. Others implement a shortened schedule with only 32 hours each week. Either way, employees still have the same responsibilities. Reducing the workweek just cuts down the time they have to complete their duties. “Burnout is a work-related syndrome. If people are forced to cram their work into four days when they prefer five — and if they need longer days to do so — it could cause burnout,” Jim Harter, Gallup’s chief scientist for workplace management and well-being, told CNN in November.

A shortened schedule can also act as a Band-Aid that hides the real issues behind worker dissatisfaction. For example, in 2022, Gallup found that the quality of the workplace and work experience are up to three times more impactful on employee well-being than the amount of time worked. Addressing the root causes of why employees are unhappy with their company in the first place could be a more effective and inclusive solution than changing up the workweek.

There’s just no one-size-fits-all solution. The four-day workweek leaves out entire industries, like manufacturing and customer service and emergency response, because they don’t have the same flexibility. “It becomes challenging in fields where services have to be provided in the here and now, at fixed times, for customers, or people who are being cared for,” Bernd Fitzenberger, director of the Institute for Employment Research in Germany, told DW News.

MAY 2024 19

ILLUSTRATION BY RYAN PELTIER

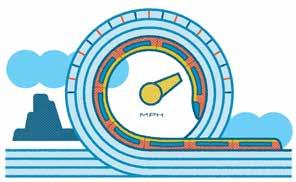

BOARDING PASS

CAN AMERICAN TRAINS MAKE A HIGH-SPEED COMEBACK?

THE UNITED STATES became a railroad superpower on May 10, 1869, when the ceremonial “golden spike” completed the first transcontinental railroad in Promontory, Utah. Funded with $64 million in federal loans and untold land grants, this new infrastructure linked California to the eastern states and opened up the landlocked interior for travel and trade. Trains became more than a symbol of prosperity and strength — until the automobile took over. Now the promise of high-speed rail could be changing that, starting in the Southwest. On the 155th anniversary of the project that started it all, we break down the state of railroads today and in the future.

ARIANA DONALDS

186 MPH

This top speed will allow Brightline West — the country’s first true high-speed railroad line, projected to connect Los Angeles and Las Vegas in time for the 2028 Summer Olympics — to cover 218 miles in just over two hours. This

all-electric alternative for 3.5 million air travelers and 11 million drivers each year is expected to create 35,000 jobs and ease traffic on adjacent I-15, currently a 4-12 hour drive depending on traffic. For comparison, China’s Shanghai Transrapid magnetic levitation train hits 267 mph.

8 MILES … OR BUST

Before racing a stagecoach in 1830, the Tom Thumb was a prototype steam locomotive built to convince investors.

Funicular railways and horse-drawn railcars had been in use since about 1795, but this

engine’s performance — hitting 15 mph before breaking down midrace — won over the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, which used the technology on the country’s first commercial line, a 13-mile commute for industrial workers at Ellicott’s Mills outside the city.

20 DESERET MAGAZINE THE BREAKDOWN

MORE THAN 1,000 DEAD

In the 1800s, the cost of building could sometimes be measured in casualties, like this estimate of losses among Chinese laborers on the 690-mile Central Pacific line east from Sacramento. They used nitroglycerin to blast their way across the Sierra Nevada through granite, snow and ice. Avalanches and brutal weather — 44 winter storms in 1866 and parched Great Basin summers — made matters worse. They persisted despite discrimination, low wages and poor living conditions, forming 90 percent of work crews.

$100 BILLION

The current cost forecast for the 171-mile Central Valley project linking Bakersfield and Merced, California is triple the original 2008 estimate. This segment, part of a statewide high-speed rail project, will serve 6 million people in a region known for agriculture. It’s expected to launch in 2031, 11 years late. For comparison, the price tag for Brightline West is estimated at $12 billion, half of that in federal funding that has already been announced. It’s backed by finance billionaire Wes Edens, owner of the NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks.

254,000 MILES

American railroads peaked at this length in 1917, before the impacts of nationalization during World War I and a shift in federal funding from trains to automobiles. From 1929 to 1965, the number of passenger trains in service fell by 85 percent. Today, the national highway system is 164,000 miles long, compared to 137,000 miles of rail. That reflects the relative portions of federal transportation and infrastructure spending in 2023 — 22 percent on rail and mass transit and 44 percent on highway transportation.

28.6 MILLION

That’s how many passengers Amtrak carries each year, including 3 million on its flagship Acela line that runs 457 miles between Boston and Washington, D.C. The country’s fastest train, it only reaches its top speed of 150 mph on a 16-mile stretch in New Jersey; another 33.9 miles of high-speed rail are sprinkled along the route. New train sets with enhanced “active tilt” systems can travel curved sections faster.

8X MORE EFFICIENT

25,000 MILES

National highway system

164,000 miles

Rail system IN 2024:

137,000 miles

High-speed rail far outpaces airplanes in terms of energy use; it’s also four times more efficient than automobiles. All high-speed trains require electrified track — currently amounting to around 1,100 miles nationwide — but Brightline West will be all-electric, and promises to run entirely on renewable energy with zero greenhouse gas emissions back to the source. It’s expected to cut 400,000 tons of carbon emissions each year.

Covering this distance, China’s high-speed rail network is the world leader, with 6,000 more miles under construction. Spain and Japan are a distant second, with 1,800 miles each. The latter is a leader in velocity, expected to debut a 374 mph magnetic levitation train on the Tokyo-Osaka line in 2037. But about a dozen high-speed trains are in planning stages across the U.S., in corridors like Dallas-to-Houston and Portland-to-Vancouver, where the Cascadia is projected to add $355 billion in economic activity over the next 20 years.

MAY 2024 21

ILLUSTRATION BY THOM SEVALRUD

DON’T TELL MOM

MY KIDS HAVE A GROUP CHAT WITHOUT ME. THAT’S A RELIEF

BY JENNIFER GRAHAM

Normally, in the course of human events, being left out of a group stings. Even the most popular woman in the world, Taylor Swift, has a story about being excluded from a group of middle school girls she thought were her friends. She asked the girls to go to the mall, and they said they were busy. Only it turned out they were busy having fun at the mall without her. Honestly, I’m not convinced she has recovered from that.

Social scientists tell us that the pain of exclusion harkens back to prehistoric times when, if our forebears were kicked out of their group, they would die of starvation or exposure. We all still have hunter-gatherer DNA stashed away in between the genetic adaptations to hold our breath underwater and digest milk in adulthood (sorry to all the lactose intolerant out there). Amid the very real evolutionary need to feel part of social groups, there is one particular group in which I am decidedly not welcome, but this time, it doesn’t bother me at all. In fact, I revel in the fact that I am not a part of my children’s private group text: the sib chat. In my family, the sib chat is an ongoing conversation between my children that takes place via text. Being an only child,

I’ve never had the option of joining one. But my four children did, and boy, did they. Most weeks, the sib chat is as lively and electric as a broken power line snapping in the middle of the street. It crackles with news and jokes and memes. I only know of this by means of hearsay, and the occasional errant text, which is quickly followed up with

keeping them up to date on what each other is viewing on TikTok. A meta-analysis of 26 studies on sibling relationships worldwide found a wealth of positive outcomes associated with strong sibling ties. From living longer to being happier, those who are close to their siblings seem to do everything better.

MOST WEEKS, THE SIB CHAT IS AS LIVELY AND ELECTRIC AS A BROKEN POWER LINE SNAPPING IN THE MIDDLE OF THE STREET. IT CRACKLES WITH NEWS AND JOKES AND MEMES.

“WRONG CHAT!” by any number of my kids, warning me that whatever just pinged on my phone wasn’t meant for me and would likely offend my differing sensibilities. Out of respect for my children — and the sib chat — I promptly delete.

I’m not sure they know it, but the sib chat does so much more for my children than

In December, there was one dissenting study published in the Journal of Family Issues that caused quite a stir with its findings that only children surveyed experienced better mental health than those with siblings. Much of this deduction centers around the idea of resource dilution:

The more kids parents have, the fewer resources and less attention they are able to give each child. But even that study’s conclusion conceded that the data doesn’t consider the countereffect of the attention given to siblings by one another and doesn’t attest to the quality of sibling connections, according to study author and professor of sociology Doug Downey. “It is likely that higher-quality sibling relationships will be more beneficial to children and may have more positive effects on mental health.” This study also noted that while its findings trend toward the negative, other research

22 DESERET MAGAZINE

MODERN FAMILY

MAY 2024 23 ILLUSTRATION BY ANE ARZELUS

WHEN CHILDREN ARE YOUNG AND WHACKING EACH OTHER ON THE HEAD WITH SQUISHMALLOWS, IT’S HARD TO ENVISION A FUTURE IN WHICH THEY INTERACT PLEASANTLY AND VOLUNTARILY WITH EACH OTHER AS ADULTS.

has shown that having more brothers and sisters correlates with developing better social skills and a lower likelihood of divorce later in life.

When children are young and whacking each other on the head with Squishmallows, it’s hard to envision a future in which they interact pleasantly and voluntarily with each other as adults. This is even more difficult to imagine when there’s a sizable age gap between the youngest and oldest (the spread between mine is 10 years). When a sib chat blossoms, it’s as unexpected and miraculous as the first daffodil that breaks through hard, cold soil in late winter. Where, we wonder, did this marvelous thing come from? And how did such a boon come to our family?

My children weren’t always close, and I blame that largely on the gap in ages. Most 16-year-olds aren’t really that into the lives of 8-year-olds. It wasn’t until all four were in their late teens and early 20s that something emerged that looked like a real connection. When the pandemic hit, three of them came home for 18 months, and, for all practical purposes, became each other’s best friends. (The oldest was living on his own by then.)

It turns out that, pandemic or not, brothers and sisters tend to grow warmer toward each other as young adults. A 2018 study that looked at relationships between siblings in “emerging adulthood” found that even with gaps in communication, “sibling relationship quality appeared to improve with participants, indicating they were happier with their sibling and felt more like equals and had a better understanding of one another.”

My youngest daughter knows that one reason she exists is because I wanted her older sister, who had only two brothers at that point, to have a sister. Not having had a sister myself, I imagined it to be a magical relationship, and indeed it has been, at least from my vantage point. They talk daily, and like to go out with each other for walks and meals. They have watched all 327 episodes of the hit TV show “Supernatural” together, some more than once. And while my own relationship with my daughters is strong, I

know that they can relate to each other in ways that are different from the way I relate to them, particularly since I don’t understand half of their jokes.

The sib chat isn’t just there for the prosaic daily messages. It’s also there for when my kids need support from one another. I believe another one of the psychological advantages of people with siblings is knowing they have people who have known them the longest in their corner, which becomes all the more important as our parents, our original defenders, grow older and frail. This sort of built-in protection in a family unit explains why researchers find positive physical and mental health outcomes associated with having siblings. One study conducted in Canada examined the effect of sibling relationships when a family was faced with stressful events. They found that strong bonds between brothers and sisters help them make it through difficult times. “Notably, the protective effect of sibling affection was evident regardless of mother-child relationship quality,” the authors wrote.

The group chat my children have is just that — an expression of sibling affection. A way that siblings can share joys and weather storms together even when they’re no longer living under the same roof, just the way God and Steve Jobs intended it. Yes, the content may be light or utilitarian — When is Grandpa’s birthday again? Who has a Hulu account? This meme! — but don’t be fooled by that. There is deep love lining the riverbed here that often goes unexpressed among siblings who grow up being gruff to each other, which is something that is pretty much required in the teen years. Later, when they moved out of the house and realized that those people they left behind (or who left home before them) comprise a large part of the small society of people who will know them for all of their lives, this bond became a remarkable gift — for them, and for me. Their sib chat is a chattering, dinging, meme-infused, daily reminder of that gift. And a reminder that when I leave this Earth, I can leave confident that they will continue as a tight family unit, together.

24 DESERET MAGAZINE MODERN FAMILY

SOBER MINDED

WHY YOUNG AMERICANS ARE ABSTAINING FROM ALCOHOL

BY ANNEKA WILLIAMS

Ilived in the French Alps for nearly six months while in graduate school, ending workdays with long hikes in rugged mountains, eating more than my fair share of freshly baked baguettes, and wandering down cafe-lined streets watching locals sip glasses of wine as meals stretched on for hours and warm wishes of camaraderie and abundance were toasted. There, I learned that in French, santé is synonymous with the English “cheers.” It also translates to “health.” I’m not sure if that’s the etymological intention, but it certainly gave me pause for reflection, mostly because it conveyed a very different relationship to alcohol than the one I see unfolding in my own culture. It also is underpinned by the irony of a toast for health being associated with alcohol — something that we’re finding has objectively unhealthful qualities.

Today, young people in the United States — and other countries around the world — are drinking less than ever before. According to Pew Research Center, adults ages 18 to 34 who reported that drink at all dropped

from 72 percent in 2001-03 to 62 percent in 2021-23. A 2023 Gallup survey found that the rate of drinking has declined by 10 percent in that same age group bracket over the last two decades. It seems that temperance is tapping into the roots of modern-day life.

Our relationship with alcohol in the United States has been fraught for about

TODAY, YOUNG AMERICANS ARE DRINKING LESS THAN EVER BEFORE.

as long as we’ve been a country. To drink or not to drink has long been the subject of social judgment, public scrutiny and moral division. While what we consume is a deeply personal decision, alcohol tends to carry more weight than most other food or drink choices. Historical angst around alcohol dates back to the late 19th century with the beginnings of an aggressive temperance

movement and, later, more than a decade of nationwide prohibition in the 1920s. The temperance movement had numerous religious affiliations and opposed alcohol’s impact on moral character. In this era, alcohol was framed as the cause of many social problems such as domestic violence, poverty and crime, so constitutional prohibition was enacted to try to remedy these social ills by banning the assumed cause. Today, opposition to alcohol seems to stem more from education and personal choice around general physical and mental well-being.

In response to emerging research about the impacts of alcohol consumption on our health, young adults are forging a new relationship with alcohol than generations before them.

I am Gen Z, while my partner is millennial. We like to keep a healthy amount of generational rivalry present in our relationship, so we have a crudely made Venn diagram taped lopsidedly to our fridge that features “millennials” on one side, and “Gen Z” on the other. Most of the diagram’s contents

26 DESERET MAGAZINE NATIONAL AFFAIRS

MAY 2024 27 ILLUSTRATION BY TIM BOUCKLEY

“YOUNG PEOPLE HAVE DEALT WITH FAMILY AND FRIENDS WITH ADDICTION ISSUES, PROBABLY MORE THAN ANY OTHER GENERATION."

are lighthearted nods to generational icons and trends. Gen Z gets “Noah Kahan” and “TikTok,” while my partner has claimed “blink-182” and “avocado toast” for the millennials. I don’t often feel like the line between millennials and Gen Z is all that apparent, even when it comes to drinking alcohol or not drinking it. Both generations drink less than those before us. But a closer look shows that abstaining from drinking is more of an identifier for Gen Z than it currently is for millennials.

Javier Lastra, one of the lead authors of a 2017 Berenberg Report on generational drinking habits, found that Gen Z (individuals born between 1997 and 2012) was drinking 20 percent less per capita than millennials who, in turn, were drinking less than Gen Xers and baby boomers did at the same age. One of the main reasons they found to drive this shift? Health, both mental and physical. “There’s generally a greater awareness by Gen Z (compared to previous generations) about health,” Lastra explains. “They seem to be a much more health-conscious generation than previous ones.”

There is also evidence of increasing health consciousness across all age groups.

A 2023 Gallup survey found that 39 percent of all adults and 52 percent of young adults (age 18-34) view consuming even one or two drinks a day as bad for health, representing a marked increase in this point of view since just 2018. Public interest in mindfulness meditation has exploded over the last several decades, the fitness industry is booming to meet rising consumer demand for workout classes and gym services, and there is an increase in the use of health-tracking technologies such as apps and smartwatches that measure sleep, calories and other physiological metrics of health. Amid all this information about how to be healthier, live longer and look better, decisions around alcohol are just one piece in the broader puzzle.

In recent decades, there has been a proliferation of research suggesting that alcohol is bad for human health. In 2023, the

World Health Organization announced that there is no safe amount of alcohol to drink; any amount of alcohol has adverse health impacts such as increased risk of heart disease, high blood pressure and mental health problems. Research from the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health shows that alcohol consumption, no matter the amount, alters how our body functions at a cellular level, “triggering a number of adverse effects.” This includes disrupting neural stem cell growth, interfering with the communication between nerve cells and causing inflammation that inhibits our mitochondria’s energy production. That can manifest in poor sleep, inflammation in the body, high blood pressure and other negative effects. Alcohol is classified as a group 1 carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, placing it among other high-risk carcinogens such as asbestos and harmful radiation. With information like this at hand, it would make sense for anyone of any age to be at least a little scared of alcohol.

History is important, too.

“Young people have seen the behavior of their parents and grandparents and have dealt with family, friends ... people that they know (deal) with addiction issues, probably more than any other generation,” says Gary Frankel, a licensed social worker in Vermont who conducts individual and group therapy sessions for young adults. According to the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, more than half of all adults have a family history of alcohol abuse or problem drinking. It’s not uncommon for families in America today to be dealing with the repercussions of generations of familial strife driven by these issues. In that context, it’s simply hard to view alcohol as “cool.” It’s hard to view anything that’s wrapped up in negative feelings as “cool.” Red Brick Road, a U.K.-based ad agency, conducted a report focused on Gen Z drinking habits in the United Kingdom and found that 51 percent of Gen Z respondents reported that their “online image”

28 DESERET MAGAZINE NATIONAL AFFAIRS

was a factor when going out “socializing and drinking.” Lastra found the same thing in a separate report: Gen Z is drinking less, in part due to fear that drunk escapades and reckless decisions will be etched into permanence on the internet. “(Respondents) were afraid of being humiliated,” Lastra explains. But more and more, instead of making choices to avoid negative consequences, Americans are incentivized by the positive effects of their health-based choices.

Just a few weeks ago, I drove by a billboard on Utah’s I-215 that read “Self-care is cool.” In a 2022 McKinsey report, around 50 percent of U.S. consumers reported wellness was a top priority in their daily lives, which represented an 8 percent increase from 2020. This newfound dedication to health seems to be pushing Americans, particularly young adults, away from alcohol. By some estimates, more than a third of people under the age of 27 in the United States abstain from alcohol for the sake of their mental health. And many more take a more moderate and flexible approach. “Gen Z is drinking less alcohol and I think that where that might stem from is social things like what mental health and physical health is and what it means to be a well person,” explains Frankel.

But prioritizing health isn’t as simple as just abstaining from alcohol. In a culture that’s drinking less, there’s a need to navigate new ways to socialize that don’t involve drinks at the bar with friends. For

“THERE’S GENERALLY A GREATER AWARENESS BY GEN Z ABOUT HEALTH. THEY SEEM TO BE A MUCH MORE HEALTHCONSCIOUS GENERATION.”

centuries, the social hubs where alcohol has traditionally been served have been proven to bring people together and facilitate social connections that benefit health. Robin Dunbar, an anthropologist at Oxford University, found that living near a pub significantly increased an individual’s happiness thanks to the in-person connections and local community fostered through frequent pub visits. So, one issue to be aware of as alcohol becomes less prevalent in the U.S. is creating solutions to mitigate ongoing social division and isolation. And as I flash back to the hum of voices and the rich sound of laughter echoing down the cobblestone streets of that French village, glasses clinking santé, I can’t help but wonder what changes await as the sober-curious movement gains traction.

Historically, churches, offices and clubs have been important hubs of social interaction that facilitate community and benefit mental health, but these institutions are declining. In 2020, a Gallup survey found that only 47 percent of Americans said they belonged to a church, a 23 percent decrease since 1999. The share of individuals who work remotely has skyrocketed over the past two decades. And, thanks to the iPhone and other technological advancements, more socializing is happening digitally. While there is merit to being connected digitally, in-person interactions have been shown to have a greater benefit to overall well-being, and American adults are now spending

30 percent less time face-to-face socializing than 20 years ago. Simply put, we are spending less time with other people and that is taking a toll on our health.

Social disconnection, an increasing phenomenon in our culture, can have devastating impacts on long-term health. Researchers from Brigham Young University suggest that poor social relationships or the lack of social community can have health impacts of a similar magnitude to smoking and alcohol consumption. Drinking alcohol is objectively harmful to health, but, when it comes to curtailing the negative impacts of social isolation, there could be something to be said for the health benefits of finding new ways to go out with friends.

The future of alcohol consumption in the United States is uncertain, but it’s clear that we are all drinking — or not — and hanging out — or not — in markedly different ways than in generations past. Where this will lead in terms of net health and happiness remains to be seen. As Americans grapple with the idea of what it means to be a healthy person, our culture is at an inflection point, and it’s hard to know whether and how alcohol fits into the equation. It is increasingly apparent that being a healthy person is more complicated than simply being sober. By approaching alcohol more mindfully, young adults are providing space for consumption to be an ongoing and deeply personal choice, rather than a categorical decision. Cheers, or santé, to that.

MAY 2024 29

THROUGH THE LENS

ELLIOT ROSS CAPTURES THE WILD WEST BEFORE IT ’ S GONE

BY NATALIA GALICZA

Do you want to see my favorite alligator?” A blond-haired man points out the reptile in question and begins to climb atop it, sitting on the base of its tail. He interlocks his fingers around its throat and leans back, pulling the gator skyward, making it look like a strange version of a rearing steed. At this moment, surrounded by more than a hundred alligators at the Colorado Gators Reptile Park — a long way from home for them — Elliot Ross crouched in the dirt to shoot a portrait of man and beast.

“Why do you like getting on top of your alligator?” he remembers asking.

“I don’t know,” the man answered. “It’s just a way of saying hello.”

“Do you think he likes it?”

“I don’t know, probably not.”

“So why do you do it?”

“I don’t know. It feels good. I feel powerful.”

The man on the alligator glares into the lens, his leather work boots planted in the dark soil, his posture straight, his denim jeans worn. The portrait is part of Ross’ photo survey “Good Grace,’’ a project and upcoming book in collaboration with the art collective M12 Studio. It aims to showcase the current state of Colorado’s San

Luis Valley, where counties rank among the state’s poorest and driest. Ross photographed the valley and its people for months. Now, looking back, this place gives that man’s response some context: In a region so rural and isolated, a sense of power and control can feel requisite.

“I SEE MY JOB AS ILLUSTRATING THE VALUE THAT EXISTS IN THIS MISUNDERSTOOD PLACE WITH ALL OF ITS LAYERED BEAUTY, ITS DIVERSE IDENTITIES, ITS SILENT HISTORIES, ITS CULTURAL WORTH.”

The intersection of the Western landscape and people’s inner worlds defines much of Ross’ work. A couple shielding themselves from the worsening Los Angeles heat under parasols; his family in northeastern Colorado praying out on the plains that an incoming supercell won’t damage their crops; a young woman in a

quinceañera gown posing in front of the wall that divides the United States and Mexico. These moments serve as a remedial view of the Western identity and experience that Ross has seen become romanticized, demonized and, above all, misunderstood. “I get defensive when people refer to parts of the West as flyover states, which denotes there’s nothing of value,” he says. “And I see my job as to illustrate the value that exists in these misunderstood places with all of its layered beauty, its diverse identities, its silent histories, its cultural worth.”

IT STARTED WITH barn cats and storms. Station wagons and tractors. Electrical outlets and Air Force drills. In his early years, Ross photographed anything he could find to make sense of his surroundings. His grandmother had given him his first point-and-shoot camera when he was four years old, the same year his family moved from Taipei, Taiwan, to rural Colorado. Quickly afterward, photography became a way to navigate the culture shock of switching from a dense urban environment in a city of skyscrapers and neon lights to a home on austere plains where the nearest neighbor or grocery store was miles away.

30 DESERET MAGAZINE THE WEST

“

MAY 2024 31

PHOTOGRAPHY

BY

ELLIOT ROSS

A YOUNG MAN ATOP AN ALLIGATOR IS PART OF ELLIOT ROSS’ RECENT WORK DEPICTING COLORADO’S SAN LUIS VALLEY.

32 DESERET MAGAZINE THE WEST

JAYMIN MARTINEZ POSING IN FRONT OF THE BORDER WALL IN A QUINCEAÑERA GOWN IN BROWNSVILLE, TEXAS.

His mother’s side of the family is Taiwanese Chinese, but his father comes from a background of American farmers and ranchers. Ross’ childhood chores included bottle-feeding his 4-H calf every morning, clearing tumbleweeds and fixing fences. He had no allowance in the traditional sense, but every month he got a new roll of film. His family made a pit stop at Walmart on the hour-and-a-half drive to church on Sundays to drop off his film when it was ready to get developed. Those photos often depicted his life on the family farm — all the chores, but also summers spent building forts, searching for arrowheads, dawdling through canyons. Over time, the photographs have come to communicate the values with which Ross was raised. “All the expected descriptors certainly come to mind: self-sufficient, resourceful, endlessly hardworking with high esteem for family

and sometimes God,” he says. “I was raised with these attributes, and they certainly have shaped who I am today. I believe in the small things that create a sense of community, like long-winded conversations with your neighbor.”

“I GET DEFENSIVE WHEN PEOPLE REFER TO PARTS OF THE WEST AS FLYOVER STATES, WHICH DENOTES THERE’S NOTHING OF VALUE.”

Those traits, in their absence, stood out more after Ross left. He valued living in New York City and working as a photographic assistant for luminaries Annie Leibovitz and Mark Seliger. But he also found himself longing for family, canyon

country, high plains, the West’s variety and nuance and contradictions. So he came home and kept his camera in his hand. He captured wrinkled hands grasping a Bible so worn its spine is held together with tape; combines gliding through golden fields; farmers taking in a sermon’s message at Cowboy Church; a child spinning around in a makeshift rain dance to fend off an incoming storm.

Ross was named a Critical Mass Top 50 artist the year he released these photographs in a collection titled “The Reckoning Days,” and held his first solo exhibition at the Center for Fine Art Photography in Fort Collins, Colorado, the following year. The response reasserted his decision to move back West, encouraging his newfound dedication to documenting the very world — once unfamiliar — that became his own. “It was, in a lot of ways, an

MAY 2024 33

ROSS’ FAMILY IN NORTHEASTERN COLORADO, PHOTOGRAPHED WHILE PRAYING OVER THEIR CROPS ON A SUMMER EVENING.

affirmation that I was on the right path,” he says. “I feel like I can make work here. Because I’m a part of this.”

EVERYWHERE ROSS GOES, he carries a poem. It’s a one-page printout of Max Ehrmann’s “Desiderata.” The paper is deeply creased from all the folding and unfolding, the reading and rereading. And of all the stanzas, the second one stands out the most to him: “Speak your truth quietly and clearly; and listen to others, even to the dull and the ignorant; they too have their story.”

He had the poem with him when he ventured to Naco, Arizona, in 2017 to meet and photograph those living along the nation’s southern border with Mexico. There, he heard a man yell from a distance while unholstering his gun. “How would you like to get yourself shot today?”

The voice belonged to John Ladd, a fourth-generation Arizona rancher who has frequently appeared on Fox News to speak

in favor of more stringent border control policies. Ross de-escalated the conversation by explaining what he was working on. He told Ladd he just wanted to listen. So for half an hour, he did.

Like the West, Ladd is not one-dimensional. The cattle rancher expressed some skepticism about the border wall at the time out of fear it would grant the federal government too much power. Yet he felt deeply protective of his ranch, which had existed in his family for more than a century, because it was an extension of himself and his history. “I think we both left from that interaction having learned a little bit more and feeling more compassion towards others,” Ross says. “Despite how angry, how out of control some situations and reactions start, I think it goes to show that there’s so much power in just listening.”

After their conversation came to a close, Ross asked to take a photograph.

A common thread among Westerners, in Ross’ view, is open-hearted skepticism — a combination of curiosity, independent thinking and compassion. His time with Ladd sticks out as particularly memorable because it demonstrated what can happen when that skepticism is put into practice. Misunderstanding can become clarity; similarities can overshadow differences.

In Niland, California, Ross met Cuervo, a self-proclaimed vagabond in his 60s who

Ladd’s portrait turned out. In it, he stands in front of his pickup truck, coated in a fine layer of red dust with a license plate that reads “BEEF.” He’s in a denim button-up and jeans, a white cowboy hat in one hand as he squints into the sun. His eyes are nearly closed and a white mustache covers his lips, but somehow it’s still clear that he’s smiling. “In my view, perceptions of politics and religion play heavily into an urbanite projection of flyover identity onto rural people,” Ross says. “The fact is, the rural West is not a homogenous place by any means.”

34 DESERET MAGAZINE THE WEST

wandered the mountains and desert spanning Southern California and northern Mexico with a mule and donkey in tow. He wore a red flannel shirt and a gray kilt, and owned few visible possessions. “He along with other vagabonds have shown me that the richest lives can be led with the fewest things, that wealth exists in interactions with others, through spontaneity and intimate knowledge of the land,” Ross says. “Through connection, we can find an understanding with others, no matter how different they are, politically or religiously or economically. It just reminds me of the hope in humanity.”

What does it mean to be a person in the West? Ross’ work is still attempting to dissect that, even to find his own answer for himself. But what he’s gathered so far is that it can mean being overlooked or shrunk down to size to fit a certain mold. It can mean contending with stereotypes and clichés that make it easy to put off putting in the effort to understand the region’s complexity and examine its gray areas.

In the Talking Heads’ 1978 track “The Big Country,” the chorus tells of an airplane passenger’s reaction to looking down on the nation’s sprawling country: “I wouldn’t live there if you paid me, I wouldn’t live like that, no siree, I wouldn’t do the things the way those people do, I wouldn’t live there if you paid me to.”

What if that passenger got to see Ross’ West? Would it change their mind? Would that matter? Ross believes so, and that debunking the myth of “flyover country” is all the more urgent in our times and all the more rewarding for those who attempt it. “I think the accumulation of experiences that I’ve had with strangers, people I’ve met along the road, they’ve taught me to arrive in humility and to walk in grace. That one can never underestimate a person, and that there isn’t a place for my own judgment or preconceived notions,” he says. “They’ve shown me the incredible power and promise listening holds. And through that, essentially, they’ve shown me hope.”

OPPOSITE: FARMERS ATTEND COWBOY CHURCH NEAR NEW RAYMER IN NORTHEAST COLORADO.

LEFT: ELLIOT ROSS BELOW: RANCHER JOHN LADD PHOTOGRAPHED AFTER A LONG AND INSIGHTFUL DISCUSSION WITH ROSS NEAR HIS RANCH IN NACO, ARIZONA. MAX LOWE

MAY 2024 35

DON’T CALL IT A GHOST TOWN

THE UNCERTAIN FUTURE OF A FAILED UTOPIA

BY ELÉONORE HUGHES

Henry Ford had an idea.

At the time, he was one of the richest men in the world, thanks to his automobile empire. But he needed control over a rubber supply. So why not make it himself?

In the 1920s, most rubber was produced in Southeast Asia. Rumors of a rubber cartel that could dictate prices worldwide sparked the decision to create a plantation where he could produce his own supply.

Ford settled on the Amazon and eventually bought $20 million worth of rainforest — almost 4,000 square miles — off Brazilian authorities. He sent American executives to oversee the construction of the town and plantation. Trees were razed, the rubble of the forest was doused in kerosene and a huge fire was lit to clear the earth. Boats loaded with heavy machinery floated up the Amazon River. Workers from across Brazil poured in to make Ford’s vision a reality. In 1928, Fordlândia, Ford’s dreamt-of utopia, broke ground.

A school was built. A hospital went up. There was a cinema constructed, to entertain residents when off the clock.

Swimming pools, a tennis court, streets lined with Fords and a golf course rose from the charred rainforest.

By 1945, the experiment failed, and the Ford Motor Company sold the land back to the Brazilian government for only $244,200. Nearly 100 years later, Fordlândia may look abandoned, but it’s not.

Roughly 2,000 residents live in the town, complete with a church, a health post and a few guesthouses and small eateries. Youngsters play Brazil’s favorite sport, soccer, near the long-overgrown golf course once built for Americans. Outside the school, 17-year-old Kayná Bodsiad strides up to me.

“Are you here to talk about Henry Ford’s fiasco or the ghost town?” he asks. His question is a stark reminder that journalists, historians and curious visitors have flocked to Fordlândia over the years as a geographical curiosity, drawn by its strange past. Residents are used to catching sight of them wandering around, their skin glistening with sunscreen and cameras around their necks.

TODAY, THE SUN dips toward the Tapajós River as a hot and humid afternoon draws to a close. Classes have ended and kids in uniform are hanging out in front of the school, soaking up each other’s company before parting ways and heading home. Behind them rises a decaying warehouse with broken windows — a vestige of Fordlândia’s past.

“Ghost town” is a trope in the eyes of math teacher Eliana Cardoso Costa. “I would strongly ask you not to use the word ‘ghost,’” she says, frowning from behind her desk in a high school classroom. Cardoso Costa, a 61-year-old woman with square glasses, grew up in Fordlândia.

“There needs to be more respect because here there are lives.”

36 DESERET MAGAZINE LETTERS FROM THE FIELD

WITH AMERICAN URBANISM, HENRY FORD ENVISIONED A MODERN PASTORAL PARADISE.

DISILLUSIONED

ABOVE: THE FACTORY THAT USED TO GENERATE ELECTRICITY AND STEAM IN HENRY FORD’S DAY HAS BEEN CONVERTED INTO A BOAT AND CAR REPAIR GARAGE.

RIGHT: CHILDREN GO TO AND FROM SCHOOL ON THE BUS, ADULTS COMMUTE TO WORK, AND LIFE GOES ON IN FORDLÂNDIA.

LEFT: TODAY, MANY RESIDENTS IN FORDLÂNDIA, LIKE MARIA LUIZA PEREIRA SILVA, 58, LIVE IN AND MAINTAIN WHAT USED TO BE VILLAS FOR AMERICAN EXECUTIVES.

BELOW: FURNITURE FROM THE FORD ERA STILL SITS IN EACH ROOM OF DA COSTA CASTRO AND DUARTE DE BRITO’S HOME.

MAY 2024 37 PHOTOGRAPHY BY APOLLINE GUILLEROT-MALICK

The false assumption that this corner of the Amazon needs someone to bring it to life was the heart of Ford’s great experiment from its beginnings. “We are not going to South America to make money but to help develop that wonderful and fertile land,” Ford said in the Magazine of Business in 1928. Fordlândia was conceived as an oasis of civilization amid an untamed jungle. “The Amazon Awakens,” a 1944 film produced by Walt Disney Productions in partnership with the U.S. government’s Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, took the viewer on a tour of the Amazon. A narrator described Fordlândia as a “model community” located “deep in the wilderness,” preparing “the future conquerors of the Amazon.” In the town’s center stood the Dearborn, Michigan-style factories, looking lost in the jungle.

Disillusioned with American urbanism, Ford envisioned the rubber plantation as a modern pastoral paradise. Under his orders, American executives enforced a ban on gambling, prostitution and alcohol. Hygiene was strictly monitored. Inspectors would visit workers’ houses and instruct them to hang their washing on lines, rather than lay them out to dry as was customary. A factory-like conception of time reigned. Plantation bosses used a siren to

call employees to report to their stations. A strict hierarchy between white executives and local Brazilian workers was etched into the town’s design as well. Three streets of mill town bungalows were built near the sloping riverbank for local workers. At least a mile away stood the “American neighborhood.” “On one side, the Americans, on the other, the rabble,” says Luiz Magno Ribeiro, a teacher and local historian.

Food was a particular source of contention. Workers’ children were served “scientifically balanced meals,” according to the 1944 film. These included oatmeal, whole grain rice, canned peaches and sometimes fish, which was known to be rotted by the time it was served. Ford abhorred cow's milk, which was replaced by a soy equivalent. Anger and frustration came to a head in the newly inaugurated eating hall, when, in December 1930, a visiting executive proposed to have the men line up for their food. “We are not dogs that are going to be ordered by the company to eat in this way,” one worker said, according to author Greg Grandin. Tensions peaked and soon workers were smashing pots, glass, plates, tables and chairs. Rioters destroyed cars, equipment and machinery during a rampage that caused thousands of dollars of damage.

Known as the “Breaking Pans” revolt, the rampage was the culmination of Brazilians’

MOST OF THE BUILDINGS STILL IN USE IN FORDLÂNDIA ARE THOSE CONSTRUCTED BY THE FORD MOTOR COMPANY, MAINTAINED AND REPURPOSED BY RESIDENTS.

dissatisfaction with Ford’s project. The imposition of an idealized way of life dreamt up back in the U.S. and forced upon locals fostered deep-seated grievances that weren’t healed. Because of this, experts conclude that Fordlândia failed at least in part due to an inability to adapt to the local culture and environment.

THE FORD ERA still serves as the backbone of much of the town’s infrastructure. To this day, water is pumped from the river and distributed to houses across the town, much as it was in the 1930s. But problems are common. The pipework has yet to undergo needed maintenance and getting new parts to Fordlândia is a challenge. Some inhabitants of Fordlândia remember the founding of the town with nostalgia, recalling modern health services — the emblem of which was the contemporary, sleek hospital. A 2012 fire destroyed much of the hospital’s furniture. Thieves looted what remained, stealing equipment containing lead and copper to sell. Today’s residents go to a small center for minor needs but are forced to head to Santarém, the nearest big city that lies a minimum six-hour boat ride away, for more complex care.

Edilson de Araujo Branco was born in the hospital built during the Ford era. He

38 DESERET MAGAZINE

LETTERS FROM THE FIELD

lives in the former workers’ part of town, in one of the once-identical rows of clapboard, wooden houses. “We’re making the most of what they left,” he says from the porch of his home. Across town, where the American expats used to live, a similar sentiment reigns. The once-stately houses are occupied by Brazilians who are technically squatters. “It’s a blessing, living here,” says Altina da Costa Castro, a short woman whose graying hair is tied back in a ponytail. “The house is big … and I can have a vegetable plot and a henhouse,” she adds as she pulls clothes off the line.

Castro makes sure the house is kept spick-and-span. The original floorboards are regularly washed. Plastic Tupperware is piled on top of a varnished dining cabinet that once contained an American family’s silverware. Castro’s partner, 79-year-old Expedito Duarte de Brito, found paintings that he believes once belonged to Americans in the garden wrapped up in a plastic cover. Those hang proudly on the wall. Duarte de Brito considers himself a guardian of history. If he could, he would do more repairs to the house, but the modest retirement stipend he lives off does not allow for projects like rebuilding a roof.

Many of Fordlândia’s other buildings show signs of neglect — if they are still standing. The cinema from the era was recently torn down. Fordlândia started falling into ruin after the Ford Motor Company left less than two decades after it arrived. No one left was able to front the bill for upkeep, but locals refused to give up on their new town. For Magno Ribeiro, the local historian, Ford’s failure was ultimately due to a brazen disregard to understand the natural environment. “Ford had the best engineers, doctors, electricians … but he forgot the best specialist in the Amazon.”

Not hiring a botanist in those early years proved disastrous. Ford engineers planned to plant rows of hevea brasiliensis, commonly known as the rubber tree. When tapped, the tree spills a waterproof sap, which can be processed into latex. But in the rainforest, the rubber tree grows best naturally

dispersed and widely spaced apart. In tight rows, they become vulnerable to fungus and pests that spread from tree to tree. Ford’s trees wilted again and again.

“THE TALE OF Fordlândia is about limits of a certain rationalization of the world. But it is also one of total blindness to everything that surrounds us,” says Margareth da Silva Pereira, an urban architect and historian who teaches at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. Fordlândia’s past holds lessons for the struggles both the region and the world are facing. “An idea of development based on the understanding of nature as something separate from human society persists until this day,” says Ana Luiza Silva, an architect and Ph.D. candidate at the Federal University of Bahia. She co-authored

THE TALE OF FORDLÂNDIA IS ABOUT LIMITS OF A CERTAIN RATIONALIZATION OF THE WORLD. BUT IT IS ALSO ONE OF TOTAL BLINDNESS TO EVERYTHING THAT SURROUNDS US.

the article “Fordlândia — Ruin of the Future.” Silva says this type of development relies on the exploitation of nature, which is seen only as a resource.

Deforestation is playing a part in rising global temperatures, which makes extreme weather events — such as wildfires, floods and droughts — more likely. In the Amazon, backers of former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro see deforestation as necessary to make way for development, namely cattle ranching and soy plantations. Some small-scale farmers also engage in deforestation, driven by a lack of economic alternatives. Now, the new extremes are being felt in real time. A historic drought in the Amazon had dramatic consequences for millions of people last year. Some communities were left stranded without access to

drinking water, food or means of transportation. In November, smoke hung in the air in Fordlândia, rising from wildfires lit by humans for deforestation.

“The fires are a huge problem,” says Bodsiad, the teenager, who wants to study environmental biology. “We can’t even see the other side of the river because of the smoke.” Like many of his classmates, Bodsiad wants to leave Fordlândia due to a lack of opportunities. “Financial resources don’t reach us here. And few people visit the town, which would give a boost to the local economy,” he says.

In 2021, GDP per capita in Aveiro, the broader municipality of Fordlândia, was one of the lowest in the country (approximately 9,000 reais, compared to 53,000 reais in Rio de Janeiro). Now the question isn’t if Fordlândia is a ghost town, but if it can continue to exist and not become one.

For decades, residents have fought for historical recognition by Brazil’s National Historical and Artistic Heritage Institute (Iphan), a status that would protect buildings from the era. Historical recognition is important, says Magno Ribeiro, who despairs at the lack of maintenance. But many who live in historical houses also want to be granted documents attesting that the house they have resided in for years belongs to them. For the time being, their homes belong to the federal government, and inhabitants live with the threat of eviction.

Historical recognition could boost tourism and provide a much-needed extra source of income for residents. But Pereira says there is a risk of turning Fordlândia into a destination where day-trippers head to the town, hoping to glimpse remnants of Fordlândia’s past. That could clash with residents’ concrete needs — such as documents attesting their ownership — and only further the town’s reputation as a “ghost town” through tourism marketing. Magno Ribeiro reminds me that here, there are no ghosts. “Ghosts only exist in rich people’s castles,” he says. Maybe, then, this town’s only ghost is Henry Ford himself, since he never actually visited the place we still call Fordlândia.

MAY 2024 39

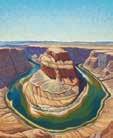

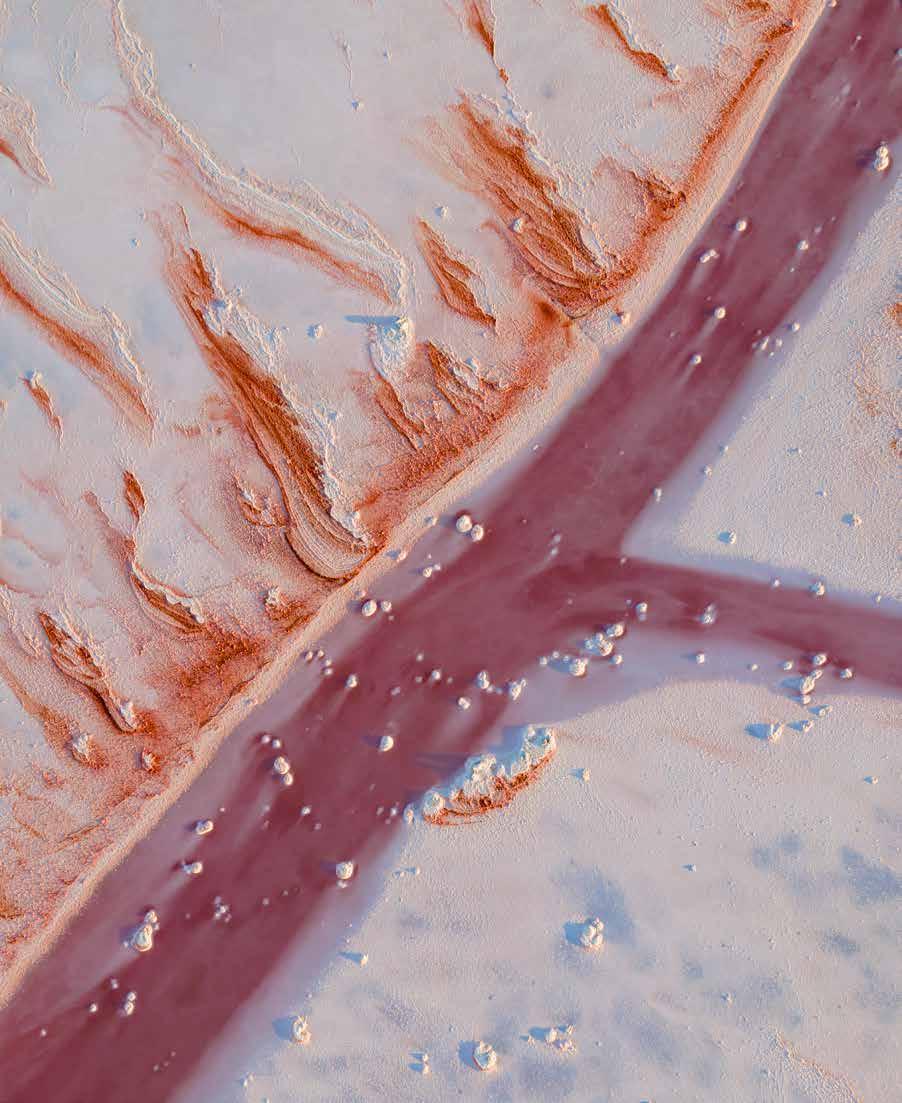

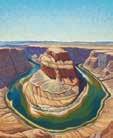

Re ection A OF Place

The Great Salt Lake is a study of how we can preserve places with more than memories

PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRIS CARLSON

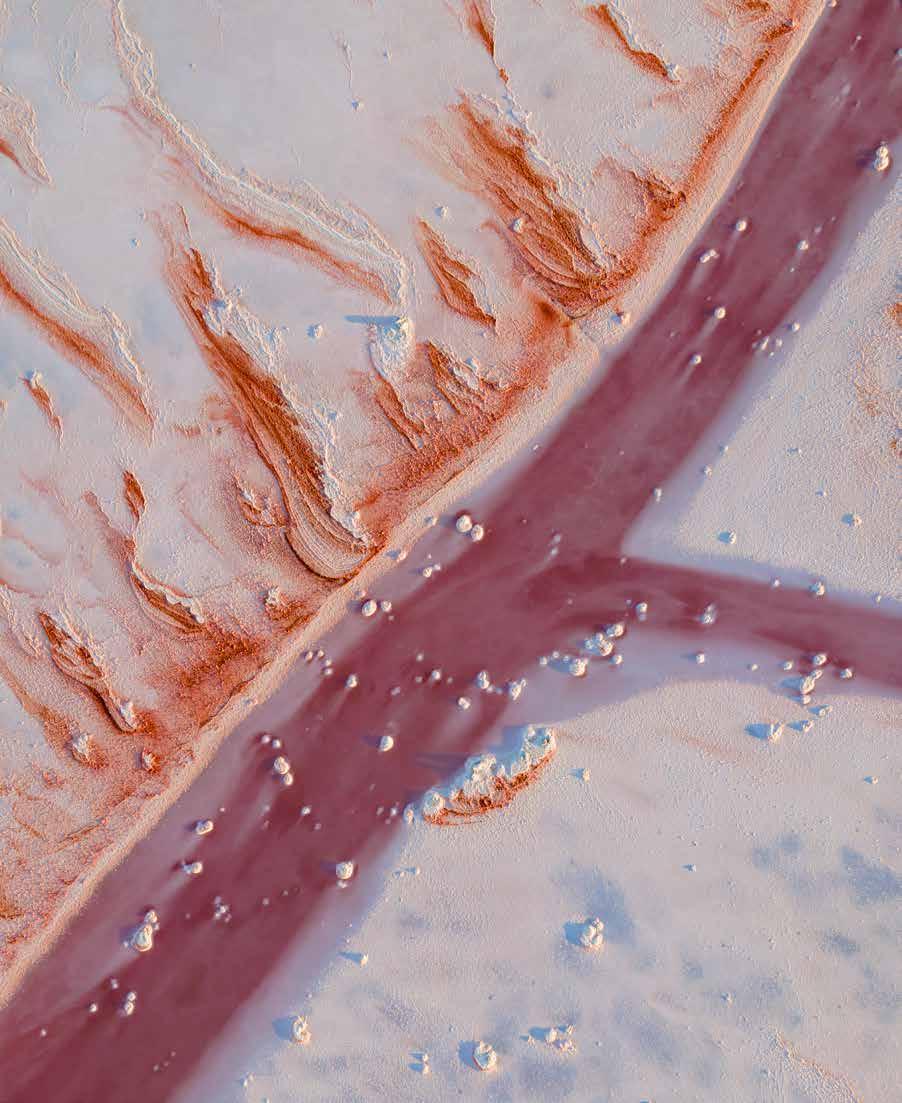

IN 2023, PHOTOGRAPHER

Chris Carlson

went to the Great Salt Lake to take photographs for the first time. Something clicked. He returned again and again, visiting the faraway, rarely seen reaches of the lake that has been described as more like a desert than the desert that surrounds it.

By year’s end, Carlson had spent time flying over the mineral evaporation ponds, tracing the line of the Lucin Cutoff, walking across now-exposed lakebed, and chasing the shoreline, tallying up visits during 48 out of 52 weeks.

As the descendant of white settlers who built homes on Antelope Island, he has felt a lifelong connection to the lake. And now he feels a calling to document it, come hell or high water, as the fate of the lake remains uncertain and legislation to protect its future arguably remains nonexistent.

“For me, photographing becomes an extension of my faith, embracing the call to ‘mourn with those that mourn,’” he says.

When looking at images of the Great Salt Lake, the supernatural beauty of Deseret Magazine’s backyard is unmistakable. Each frame is confirmation that something this captivating and kaleidoscopic exists on Earth, and that someone was there to experience it. It’s proof.

It’s also an act of preservation.

The ability to preserve something — not only in the tangible sense of pixels on screens or ink on paper, but also with the intent to create enough attention to spur action — motivates Carlson to keep returning. “It is in our presence and attentiveness that we forge a bond that compels us to protect and preserve these places.”

LAUREN STEELE

42 DESERET MAGAZINE

—1

BLUE VEIN DECEMBER 31, 2023 2 EVAPORATION PONDS OCTOBER 13, 2023 3 BISON MARCH 19, 2023

MAY 2024 43 —3 —2

1

“This is the first time I have been compelled to create such a large body of work about one specific subject. This constant ‘nudge’ has gotten me out of bed at 4 a.m. for the last year and a half. And I’m not done.”

44 DESERET MAGAZINE —2 —1

1 MIRABILITE MOUND

DECEMBER 31, 2023 2 LEE CREEK

JULY 9, 2023

3 BURROWING OWL JUNE 2, 2023

4 SPIRAL JETTY

JUNE 23, 2023

MAY 2024 45

—3 —4

“Every season spent with the Great Salt Lake teaches me the value of life’s varied seasons, each with its own unique beauty and purpose.”

46 DESERET MAGAZINE —1

AMERICAN PELICANS SEPTEMBER 4, 2023 2 US MAGNESIUM OCTOBER 13, 2023 3 LUCIN CUTOFF OCTOBER 2023

—2 1

—3

“These scenes evoke profound sorrow. And yet, there’s still a stark beauty.”

48 DESERET MAGAZINE —1 —2

1 MORTON SALT MAY 21, 2023

2 YELLOW GROWTH JULY 1, 2023

3 YELLOW-HEADED BLACKBIRD APRIL 16, 2023

4 EVAPORATION PONDS OCTOBER 13, 2023

5 ROCK FORMATION SEPTEMBER 10, 2023

MAY 2024 49

—5 —3

—4

—1

“

Come to the Great Salt Lake Walk the shores. Listen to the stories. See the beauty. Witness the plight.”

MAY 2024 51 —2 2 WHITE-FACED IBIS MAY 7, 2023 1 SPRING

JULY

BAY

16, 2023

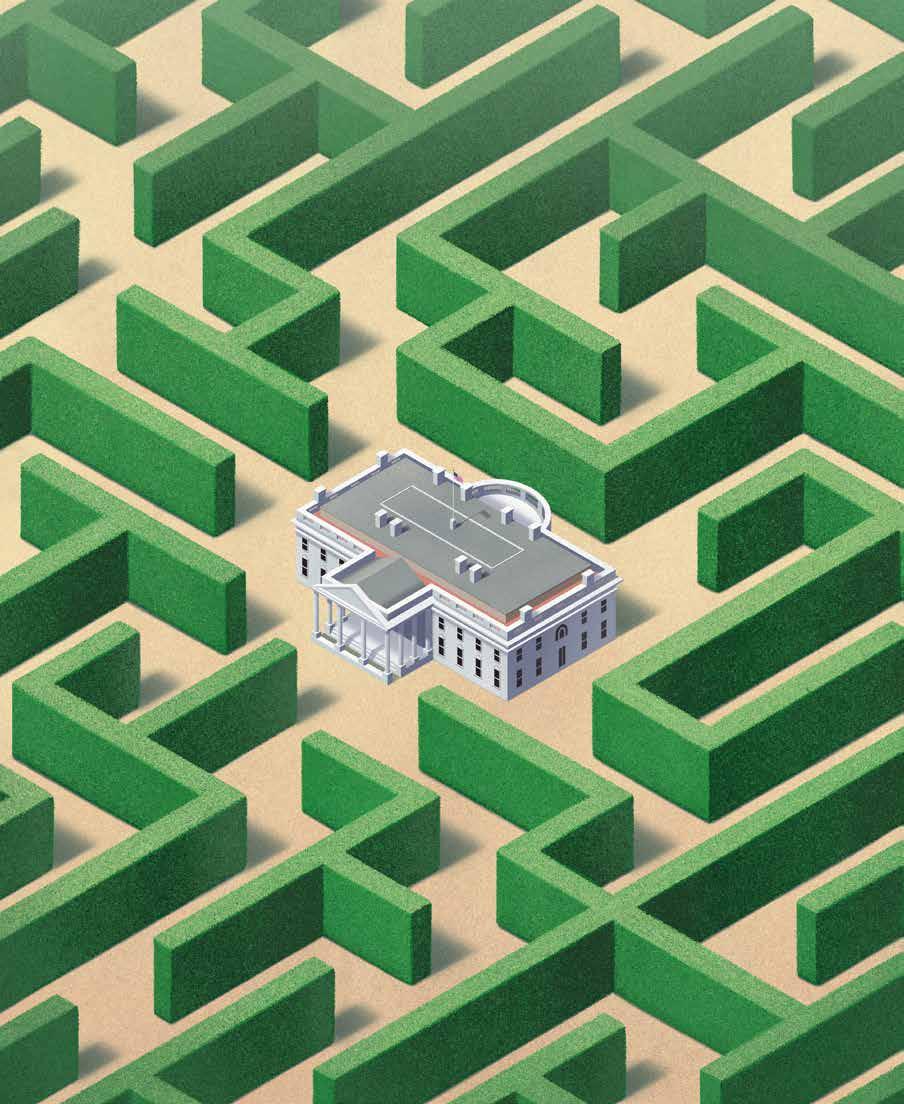

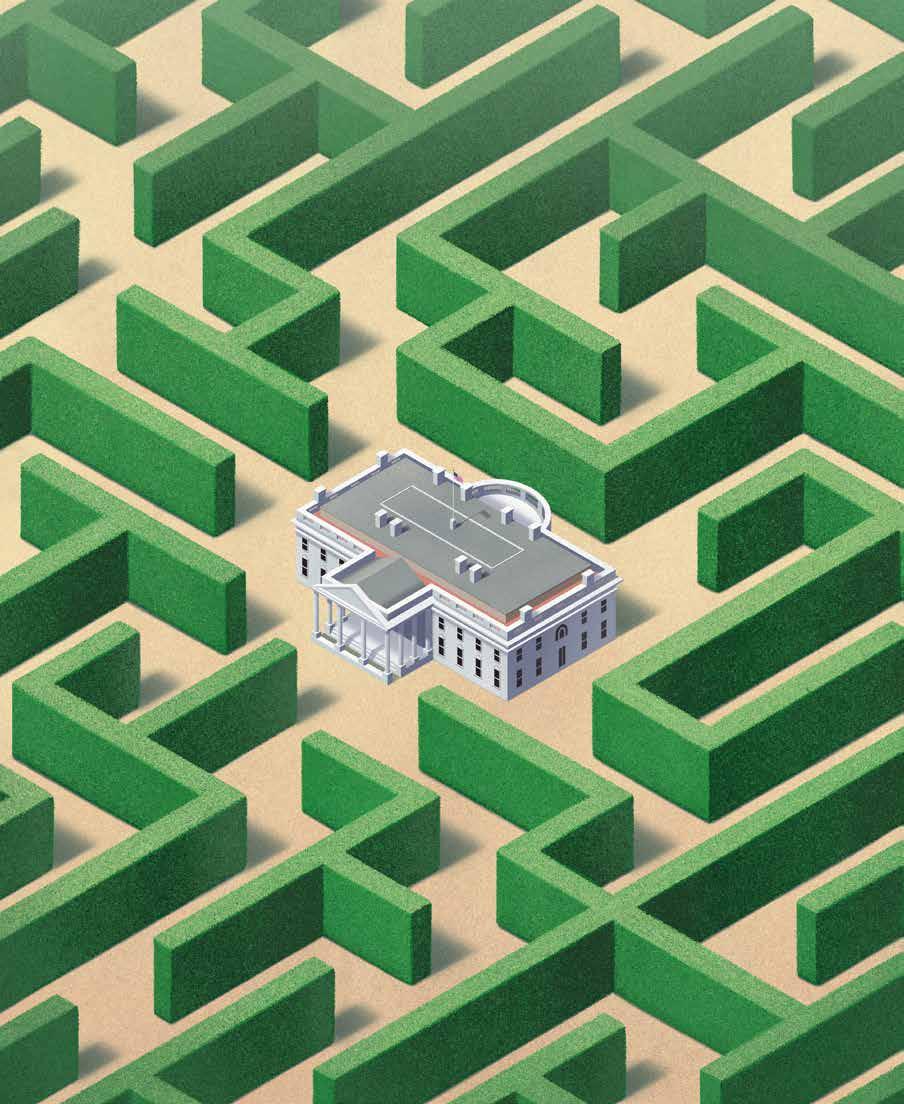

HOW A SINGLE QUIRK IN THE U.S. CONSTITUTION COULD TRIGGER AN ELECTORAL DISASTER THIS NOVEMBER GREATER THAN ANY IN MODERN HISTORY

BY ETHAN BAUER

ILLUSTRATION BY JON

KRAUSE

MAY 2024 53

magine we’ve slogged through the next six months of conventions, campaigning and TV debates. Imagine we’ve reached November 5, 2024 — Election Day. Watch as the results tumble in: Joe Biden, as he did in 2020, wins narrowly in Michigan and Pennsylvania. But Donald Trump, channeling the populism that delivered him the White House eight years earlier, wins Georgia, Arizona and Wisconsin — all of which went for Biden in 2020. The rest of the states on the red-and-blue map color in the same way they did in both previous elections. All except one.

The eyes of the nation, whether watching on CNN or Fox News, turn toward Utah, where a third-party candidate is on the verge of capturing a plurality. Biden and Trump both stand at exactly 266 electoral votes. They need 270 to win. The fate of the presidency will come down to the Beehive State’s remaining six. When the final count is in, a third-party candidate captures 41 percent of the electorate. Trump finishes just behind that candidate, at 39 percent, with Biden a distant third. The first third-party candidate to seize an electoral vote since segregationist George Wallace in 1968 would effectively prevent either major-party candidate from becoming president. What happens then?

Most Americans, for good reason, have no idea. The last time we had to ask was in

1824, when John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson vied for the presidency. The answer is something called a “contingent election” — a process where the House of Representatives chooses the president. That may sound great to Republicans, since their party currently controls the House, but it isn’t that simple. At a time when American democracy is fraying, with just 16 percent saying they trusted the government in 2023, a contingent election could be the poison pill embedded in the U.S. Constitution that causes the rest of the electoral system to fail.

Perhaps the third-party candidate is independent Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who has consistently polled in double figures nationwide, or unlikely spoilers Jill Stein or Cornel West. It could have been a contender tapped by centrist political organization No Labels, which had floated names like Joe Manchin, Nikki Haley and former Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman Jr. to oppose the deeply unpopular Trump and Biden, before it decided not to field a candidate after all. And perhaps the necessary electoral votes would come from Utah, where voters have shown an appetite for third-party candidates before; Evan McMullin and Ross Perot each garnered more than 20 percent in 2016 and 1992, respectively. But it’s not just Utah. A contingent election can be triggered by any third-party candidate earning a handful of electoral votes in any state.

54 DESERET MAGAZINE

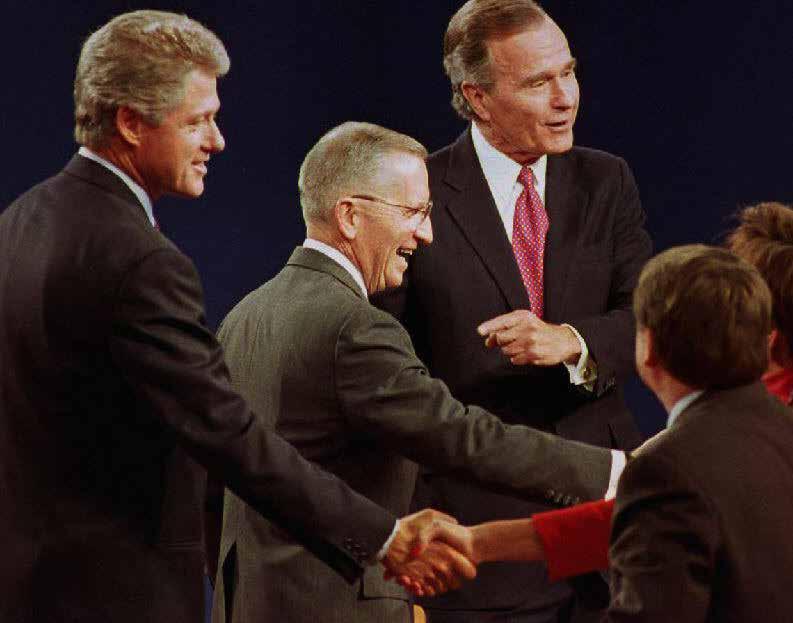

THOMAS JEFFERSON FEARED A CONSTITUTIONAL CRISIS IF NO PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE RECEIVED AN ELECTORAL MAJORITY.