Name: Kathy

Business: A Act of Love Adoptions

Legal need: General counsel

Kathy started A Act of Love Adoptions to help birth parents find loving homes for their babies. Such an important mission requires expert legal advice from a trusted partner. Kirton McConkie provides Kathy general counsel services that help ensure her business runs smoothly so she can continue bringing families together for years to come.

KEEPING

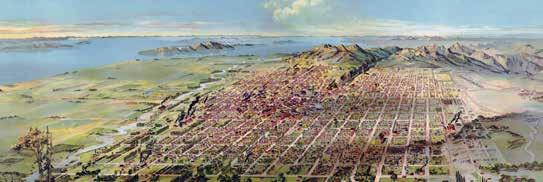

ON THE COVER: THE

BY BEAU MACDONNELLKIBBUTZ BE’ERI HELPED BIRTH MODERN ISRAEL.

THEN CAME OCTOBER 7.

“The bigger fight here is if my religion is at stake, so is everybody else’s.”

A PLACE OF REFUGE

SPIRITUAL

ARE HEALING ONE OF AMERICA’S

by lauren steele

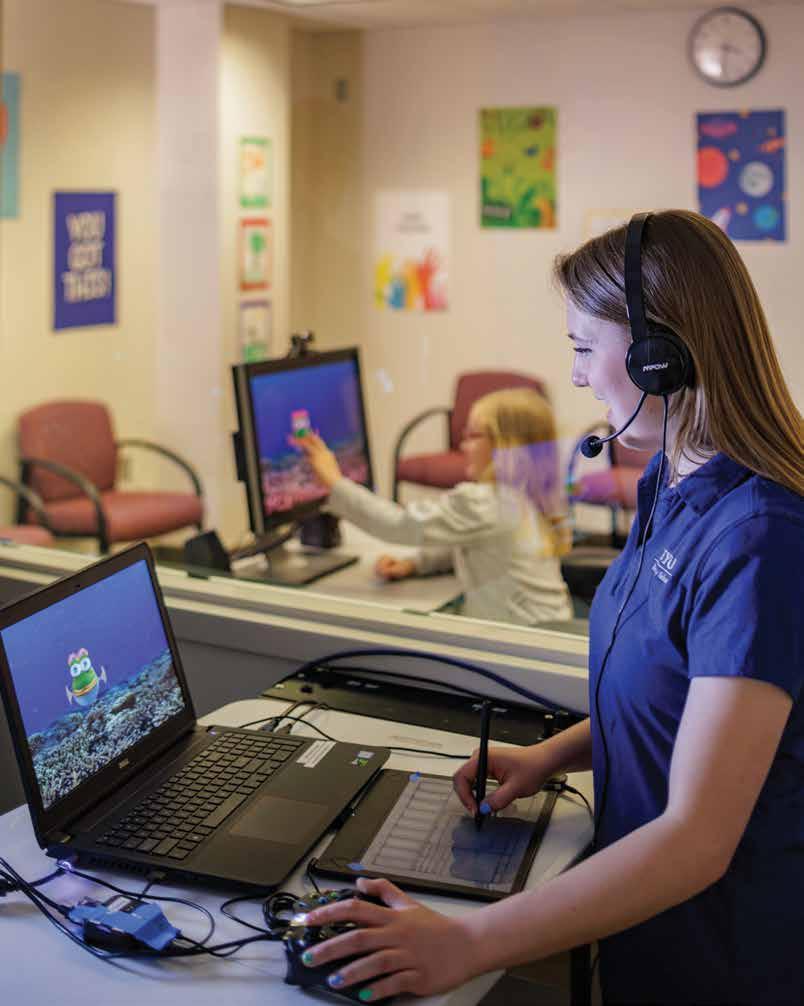

In the mind of a child with autism, conversation can be overwhelming. But at Brigham Young University, students use an animated social skills coach to help kids, like Scout, find their strengths and have meaningful interactions that build their confidence.

Learning by study, by faith, and by experience, we strive to be among the exceptional universities in the world and an essential university for the world.

BYU.EDU/FORTHEWORLD

“These aspects of human nature are evidence for the existence of a God, not against it.”

Brazile is a veteran political strategist and a former chair of the Democratic National Committee. She is chair of the William J. Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Award and an adjunct professor at Georgetown University. A New York Times bestselling author and an award-winning media contributor, her commentary on working with political opponents is on page 15.

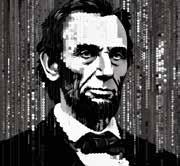

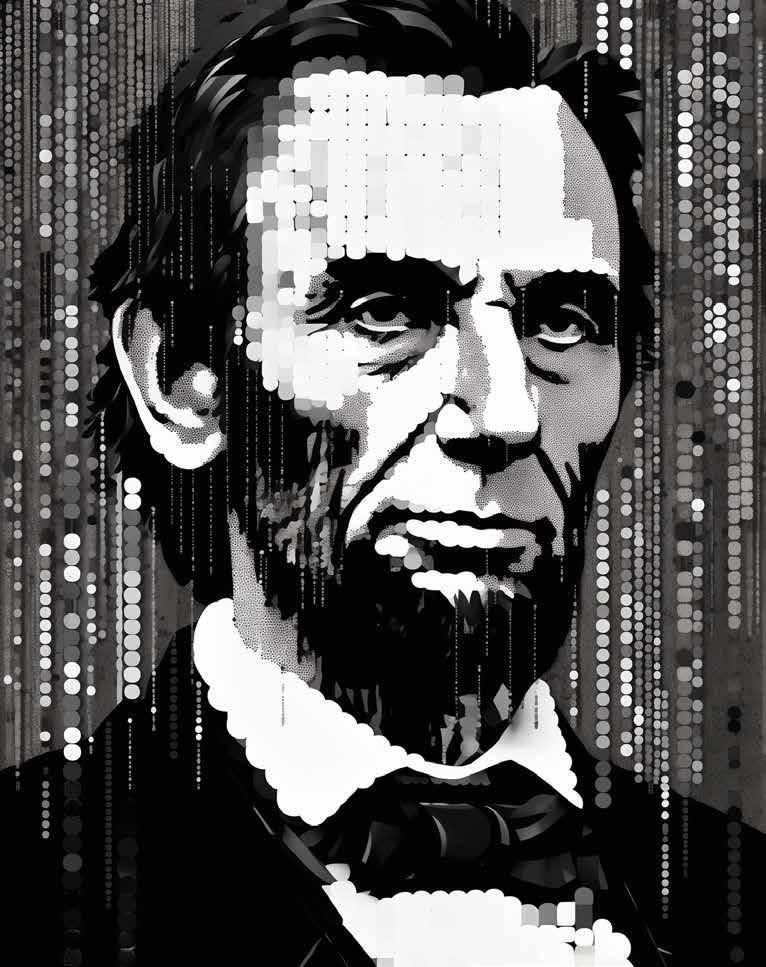

Stephens is a Pulitzer Prizewinning columnist with The New York Times and editor-in-chief of the journal Sapir. He previously worked for The Wall Street Journal and is a past editor-in-chief of The Jerusalem Post. The author of “America in Retreat,” his essay on President Abraham Lincoln’s lost lecture is on page 66.

Manzhos is a national writer for Deseret News, focusing on profiles and stories about culture and faith. A native of Kyiv, Ukraine, her work has appeared in The Atlantic, The New York Times, The Washington Post and Slate, among others. Manzhos’ profile of the influential law firm Becket Fund for Religious Liberty is on page 50.

Wilkinson is an associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University. He has been published in The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal. His essay adapted from his new book “Purpose: What Evolution and Human Nature Imply about the Meaning of Our Existence” is on page 58.

LimÓn is an illustrator based in São Paulo, Brazil. His work has appeared in Sojourners Magazine, Mckinsey & Co., Taco Mafia among other clients in publishing, branding and product packaging. His illustrations appear on page 16.

Mori is an Italian illustrator and animation director. She studied at the State Art Institute in Urbino. She was recently recognized in the prestigious publication Communication Arts for past work for Deseret Magazine. Her new work can be seen on page 21.

Iwas in Israel, wandering the Jaffa area of Tel Aviv, when my brother called. The evening before, an air raid siren had pierced the air, but tonight things were calm: couples pushing strollers, a guy with a ponytail at a sidewalk café strumming a guitar. Off in the distance, I could hear the sounds of a soccer game at Bloomfield. No fans were allowed inside as a safety precaution. After all, the country was at war, even if it didn’t feel like it. My brother wanted to know what I had learned.

I was there to report on the events of October 7, 2023, the largest single-day massacre of Jews since the Holocaust. In retaliation, the Israeli military was now methodically moving across Gaza, flattening entire neighborhoods. I struggled for a succinct answer. Back home, the conflict had seemed so distilled it was almost simple. One could see it as a battle over land or an age-old conflict between adherents of two of the world’s major religions. But on the ground, where people who had lived through rocket attacks still knew Palestinians as their neighbors, the reality was far more complex.

Hopefully, some of that nuance shows through in my dispatch from Israel (p. 40). I believe it’s important for journalists like me to face life and the issues we cover in all their complexity. Here at Deseret Magazine, we try to contribute to that by filling gaps in mainstream media coverage, whether that means elevating the region we call home or exploring the role faith plays in the world. Which is why each April we dedicate an issue to the topic of faith, and how it animates the lives of believers today.

In addition to my story, this year’s faith issue includes an in-depth profile of a small D.C. law firm that is reshaping how Americans think about religious liberty (p. 50). As contributing writer Mariya Manzhos explains, Becket has been defending religious freedom for Catholics, Evangelicals, Muslims, Sikhs, Jews

and Native Americans for 30 years — all pro bono — and has a string of significant Supreme Court wins to show for it. Religious liberty is sometimes criticized as a smokescreen for Christian conservatives to preserve discriminatory practices, but Mariya traveled to Globe, Arizona, to look into an ongoing case, in which Becket is defending the right of an Apache tribe to protect sacred land from a massive mining project.

I’m also proud of A Place of Refuge, a photo essay from Oakland, California, a troubled city on the western fringe of our region. Featuring the work of Nicoló Sertorio and J Michael Tucker, these images show how faith leaders across denominations are dedicating their ministry to lifting up a once mighty city now blighted by crime and poverty (p. 28).

Rounding out the issue are two essays I hope you’ll read, starting with Yale professor Samuel Wilkinson’s reconciliation of the tension between his belief in God and his work studying the theory of evolution (p. 58). Also, Stephen Courtright and Paul Lambert argue that religious groups may offer the answer to one of the most charged issues of our day: diversity and inclusion efforts (p. 62).

Months after returning from Israel, I still think of my brother’s question that night in Tel Aviv. I had seen the Western Wall and the Dome of the Rock. I had visited the Garden of Gethsemane and the Mount of Olives. But what had struck me most was something I saw in Tel Aviv: Jews eating in cafes owned by Muslims, synagogues and mosques on the same street. We all hold different beliefs, but when we relate to each other as humans, those differences don’t have to be a reason for conflict. We have so much more in common than we realize. In Tel Aviv, I found a city where people of different beliefs are neighbors, not enemies. Maybe there’s a lesson in that for us all.

—JESSE HYDEEXECUTIVE EDITOR

HAL BOYD EDITOR JESSE HYDE

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

ERIC GILLETT

MANAGING EDITOR

MATTHEW BROWN

DEPUTY EDITOR CHAD NIELSEN

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

JAMES R. GARDNER, LAUREN STEELE

POLITICS EDITOR

SUZANNE BATES

EDITOR-AT-LARGE DOUG WILKS

STAFF WRITERS

ETHAN BAUER, NATALIA GALICZA

WRITER-AT-LARGE

MICHAEL J. MOONEY

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

SAMUEL BENSON, LOIS M. COLLINS, KELSEY DALLAS, JENNIFER GRAHAM, MARIYA MANZHOS, MEG WALTER

ART DIRECTORS

IAN SULLIVAN, BRENNA VATERLAUS

COPY EDITORS

SARAH HARRIS, VALERIE JONES, CHRIS MILLER, HANNAH MURDOCK, TYLER NELSON

DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO.

PUBLISHER BURKE OLSEN

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER

ERIC TEEL

VICE PRESIDENT MARKETING

DANIEL FRANCISCO

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT SALES

TRENT EYRE

VICE PRESIDENT SALES SALLY STEED

PRODUCTION MANAGER

MEGAN DONIO

OPERATIONS MANAGER

BRITTANY M C CREADY

DIRECTOR OF CIRCULATION

SYLVIA HANSEN

SPANNED FROM THE SIERRAS IN CALIFORNIA TO THE ROCKIES IN COLORADO, AND FROM THE BORDER OF MEXICO NORTH TO OREGON, IDAHO AND WYOMING. INFORMED BY OUR HERITAGE AND VALUES, DESERET MAGAZINE COVERS THE PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF THAT TERRITORY AND ITS INTERSECTION WITH THE BROADER WORLD.

DESERET MAGAZINE , along with the Wheatley Institute and the Wesley Theological Seminary, sponsored a forum at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., built around the January/February issue and its theme, “How to Disagree Better.” The event featured several contributors to the issue, including Utah Gov. Spencer Cox ; Thomas Griffith , former judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit; and Timothy Shriver , the head of Special Olympics and co-founder of UNITE , an initiative to promote national unity. The 12 essays by leading commentators and scholars in the issue’s cover package generated responses from a broad spectrum of readers. A book excerpt by New York Times columnist and podcaster Ezra Klein on why Americans are polarized (“Depolarizing Ourselves”) resonated with self-described conservative reader Kerry Soelberg . “I especially agree that if we desire to Make America Great Again, we need to be clear-minded about what point in the past America was greater than it is now and why. With specifics. Without specifics, MAGA is a way to drag America back to days that we do not want to return to and to deny the significant blemishes we still have.” And David Hilton had this hope after reading historian Hyrum Lewis’ exploration into the origins of the “Left” and “Right” political labels, which have defined American politics for a half-century (“The Myth of Left and Right”): “Particularly insightful article. I wish all citizens had ears to hear it.” But Daniel Bolz , founder of Freedom Alliance LLC , wrote that all of the essays missed the mark in explaining how America got to its current state of disunion. He said that today’s divisiveness stems from an ongoing campaign since the 1960s “to infiltrate our constitutional republic and replace it with democratic socialism.” The solution to the nation’s discord, Bolz said, is an education system that teaches “the true historical facts about the origins of America’s founding.”

On the topic of the Israel-Hamas war, Megan Feldman Bettencourt revealed how hearing from Jewish and Palestinian mothers can change one’s perspective on the decades-old conflict (“A Mother’s Grief”). “The author is probably right when she describes what needs to happen to stop the killing, but is certainly wrong in thinking such a utopia can actually happen in our corrupt and evil world. It will take a millennium, as is believed by millions to occur in the future, for such a peaceful outcome to happen. It can’t come too soon!” wrote Charles Engar . Ethan Bauer laid out the debate over capitalism and whether there is a better economic system (“Is the End of Capitalism Upon Us?”). Robert Michaelson argued, “For capitalism to function at its best, all ideas must be free to be shared and voted upon by how and where people choose to spend their money or vote on policies. Those who censor and interfere with it cause the very problems they blame on capitalism.”

“If we desire to Make America

Great Again, we need to be clear minded about what point in the past America was greater than it is now and why.”

When I was coming up in politics, I made some mistakes. I used to think that because I was an athlete, I had to beat my opponent. And as I’ve gotten older, I decided I need to not just beat my opponent, but learn from my opponent.

I’m so glad I learned that lesson, because throughout my life I have fought great battles for civil rights and equal justice under the law. In trying to make Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday a national holiday, we needed Ronald Reagan. Working with John Lewis and others to extend the Civil Rights Act of 1964 or the Voting Rights Act of 1965, we needed George Herbert Walker Bush and George Walker Bush.

And on that note, I’ve got to tell you my greatest story of humility. It was the night that Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the Gulf Coast. And like many Louisianans and people from the Gulf, my family was dispersed. Those who could afford to leave had left. But it was the end of the month and when you’re working paycheck to paycheck, you’re waiting for that eagle to land — Social Security, VA benefits, whatever. And so a lot of people couldn’t leave.

I found myself in a position where I knew people in the Bush

administration. And rather than go on national TV and criticize the failure to rescue people or provide them with water, I went on national TV and said, “Mr. President, how can I help you?” For over three years I sat in the Bush White House more than I ever had in Bill Clinton’s White House. And I realized that God had put me at that table for such a time. For me, it was a time to tell people and remind them that I was one of those poor kids who grew up on the bayou, that I was born at Charity Hospital that was no longer there.

Sitting across the table from the president of the United States, I could ask him to give us another hospital, so that poor kids like me would have a place to come into this world. I was a kid who could go to President Bush and say, “We need to fix the levees and rebuild the schools and bring people back home.”

On the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, I flew down to Louisiana on Air Force One with President Barack Obama. When he asked me to come with him, I said, “I’m going to start the morning off with you in the Ninth Ward in downtown. And then I’m going to welcome the president and Mrs. Bush to my hometown.” And they both came with me. Nobody booed. We played music. The president did his best dance. And I look forward, if God allows me, to the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina next year to bring both my presidents back home because we’ve made a lot of progress.

As divisive as things are today, we must remember that Democrats and Republicans are minority parties. Neither one of us represents the majority. The majority of voters are unaffiliated. They don’t want anything to do with Republicans or Democrats. The problem is the system that we have in place does not allow them to actually make choices until the general election in most states. So we’ve got to find ways to get the unaffiliated voters back. We’ve got to make sure that they’re able to help us make big decisions with regard to the primaries, or to change the system. I think the other critical shortage we have is we need more candidates. We need more people willing to step up and run for office. I tell my students: “Why you? Because there’s no one better. Why now? Because tomorrow is not soon enough.”

When I was a child, my parents were always working late, a second job or the third job, and my grandmother would call us together by name and read us something from the Bible. When I think of her, and think of our current political moment, I think of the book of Galatians, Chapter 6, Verse 9: Do not grow weary in doing good, for in due season you will reap a harvest, if you don’t give up. I am never going to give up on America. I am never going to give up on community. I’m never going to give up on our ability to transform and to make progress.

So America, don’t give up. Our best days are ahead.

DONNA BRAZILE IS A POLITICAL STRATEGIST AND FORMER CHAIR OF THE

ADAPTED FROM AN EVENING FORUM AT THE WASHINGTON NATIONAL CATHEDRAL SPONSORED BY DESERET MAGAZINE, THE WHEATLEY INSTITUTE AT BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY AND THE WESLEY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY.

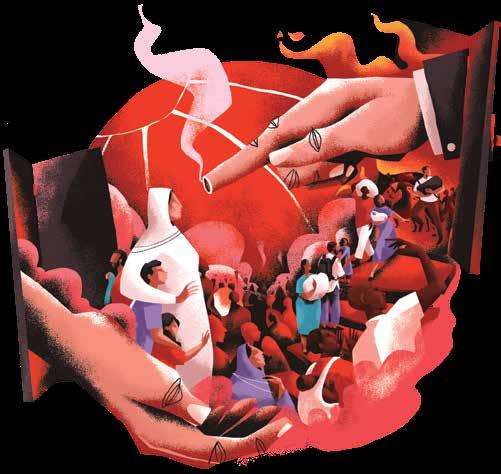

MORE PEOPLE ARE being forced from their homes today than ever before. Those who flee their countries become refugees, joining a global diaspora so vast it is difficult to comprehend their numbers. The phenomenon is as old as the idea of a country, from Babylon’s conquest of ancient Israel to Spain’s expulsion of Muslims and the ongoing implosion of Venezuela’s economy. But today’s global crisis is unprecedented in scope and impact, presenting new challenges for political leaders, humanitarian organizations and people of faith. How did we get to this point? Who is leaving which countries, and why? And who is taking them in?

MEGAN FELDMAN BETTENCOURT114

MILLION PEOPLEThat’s how many have been forced from their homes by violence, persecution or natural disasters — roughly 1 in every 73 humans, including 5.6 million in 2023 alone. If they formed a country, it would be 14th in population, behind Japan and the Philippines but far ahead of Turkey and Germany. More than half come from Syria, Afghanistan and Ukraine. Most remain in their home countries. Another 21.5 million have been displaced annually by natural disasters since 2008.

Japan Philippines Displaced people Turkey Germany COUNTRY POPULATIONS:

123M 117M 114M 86M 83M

The number of refugees — those who have crossed an international border — has nearly tripled since 2009, increasing by 293 percent. According to the United Nations High Commission on Refugees, they number 30.5 million, stuck between the countries that forced them out and those reluctant to give them a home. That’s enough to match the population of Texas.

This international law now binds 146 signatory nations that must protect refugees and give asylum when merited. Crafted after millions were displaced by two world wars — including Jews fleeing the Holocaust who were turned back to sea from literal safe harbors — the convention dictates that refugees cannot be returned to a country where they face serious threats against their lives. The 1967 Protocol eliminated geographic and time limits to protect all refugees.

Four out of five refugees are hosted by countries that collectively net less than a fifth of the world’s income, mostly developing nations located near the source countries. Turkey and Iran top the list with 3.6 million and 3.4 million, respectively, followed by Colombia, Germany and Pakistan. The United States hosts 389,300 refugees.

3 WARS

These recent conflicts have displaced almost 2 million people. Syria’s civil war, which started in 2011, launched an exodus of at least 6.5 million; 6.8 million more remain displaced within that country. Another 11.6 million fled Ukraine after Russia’s invasion in 2022. And 1.9 million Palestinians have been pushed out of their homes in the Gaza Strip by Israel’s military response to Hamas’ attack on Israel last October.

INDIVIDUALS DISPLACED BY RECENT WARS:

6.5M Syrians

11.6M Ukrainians

1.9M Palestinians

That’s the population of Kutupalong, the world’s largest refugee camp — about the same size as Indianapolis — a slum of bamboo huts packed onto five square miles of former woodland in Bangladesh. Most are Rohingya Muslims who fled neighboring Myanmar in 2017, escaping an ethnic cleansing campaign against their religious and ethnic minority. Like the 6.6 million who shelter in similar camps around the world, they deal with hunger, crime, language barriers, unemployment, outbreaks of illness and limited access to medical care.

That’s the average number of people displaced by natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods, droughts and famines since 2008, according to the United Nations. The devastating impact is often amplified by rapid urbanization and population growth in hazard-prone areas, now multiplied by the increasing pace and severity of weather-related events.

More than half of all refugees are minors. Child refugees are at high risk for mental health issues including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, and other emotional and behavioral issues which can cause disturbed sleep, inattention and social withdrawals, according to the Denver Journal of International Law & Policy.

ILLUSTRATION

BY THIAGO LIMÓN

“WE WANTED TO REBUILD OUR LIVES, THAT WAS ALL. … WE LOST OUR HOME, WHICH MEANS THE FAMILIARITY OF DAILY LIFE. WE LOST OUR OCCUPATION, WHICH MEANS THE CONFIDENCE THAT WE ARE OF SOME USE IN THIS WORLD. WE LOST OUR LANGUAGE, WHICH MEANS THE NATURALNESS OF REACTIONS, THE SIMPLICITY OF GESTURES, THE UNAFFECTED EXPRESSION OF FEELINGS.”

HANNAH ARENDT, HISTORIAN, PHILOSOPHER, POLITICAL THEORIST AND REFUGEE FROM HITLER’S GERMANY

EVERY YEAR, MILLIONS TRAVEL abroad seeking health care they can afford. “Medical tourism” is an estimated $92 billion industry that is growing by 15-25 percent each year, promising cheaper access to dental implants, plastic surgery, fertility assistance and even exotic cancer treatments — and doubles as something like a vacation to countries like Thailand or Mexico. The practice has become common around the world, but it’s particularly cost-effective here; the average American pays more than $12,500 on health care each year, outpacing the citizens of any other wealthy nation by $4,000. Some insurance companies have embraced the practice, too, but the savings come along with new risks and potential complications. Is medical tourism a boon for the marketplace, or a symptom of something rotten?

ETHAN BAUERACCESS TO DOCTORS and clinics abroad empowers Americans to make the best choices for their own health by introducing competition to a stagnant system, dramatically expanding a growing range of options. Consumers can save up to 80 percent of what they’d pay at home, according to Patients Beyond Borders, a North Carolina company that promotes the practice. For many, these savings constitute a lifeline.

“Our market has always been what I call the ‘working poor’ and they just keep getting poorer,” Josef Woodman, the company’s CEO, told The New York Times in 2021. “The pandemic has gutted low-income and middle-class people around the world, and for many of them the reality is that they have to travel to access affordable health care.” The differences in cost are most salient for elective procedures, like plastic surgery, fertility treatment and dental work, which are not usually covered by insurance.

Institutions and corporations can also benefit from even a quick jaunt into a neighboring country. In Utah, the public trust that insures state employees offers a “pharmacy tourism program,” flying clients to San Diego and shuttling them across the border to buy low-cost prescription drugs in Tijuana, Mexico. Or if they prefer, they can choose to travel to Vancouver, Canada. In 2021, researchers at the University of Chicago argued that even medical tourism to other markets within the United States could be the most cost-effective way to fill the gap left by vanishing rural hospitals. Less glamorous, perhaps, but utilitarian.

Some patients travel for personal reasons, like getting access to cutting-edge treatments or privacy for elective procedures like cosmetic surgery. “Many can return home from their ‘vacation’ without anyone knowing they had a procedure at all,” writes one registered nurse for the physician-reviewed health website Verywell Health. Others may travel for treatments that aren’t approved or allowed in the U.S., like stem cell therapy or other experimental procedures.

Despite the inevitable hand-wringing over quality of care, the independent nonprofit The Joint Commission has recognized over 1,000 medical facilities worldwide that meet its standards. The same organization has accredited American hospitals since 1951 and is the largest health care accreditor in the nation, so its approval carries weight.

MEDICAL TOURISM IS an indictment of our nation’s health care system, masked in pleasant terminology. “I prefer the term ‘outward medical travel,’” writes MSNBC health columnist Dr. Esther Choo, “and would argue that (this industry) should remind us of how inaccessible health care is here and the lengths to which people will go to get the care they want or need.” Patients may not realize what they’re risking, whether at their own initiative or nudged by insurance providers. “Quality and safety standards, licensure, credentialing and clinical criteria for receiving procedures are not consistent across countries and hospitals.”

These are not academic concerns, but vital issues with life-threatening consequences. One analysis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 93 Americans died between 2009 and 2022 due to complications from botched cosmetic surgeries in the Dominican Republic alone. The federal agency has also found outbreaks of antibiotic-resistant bacteria that were linked to medical tourism in Mexico and warns that the most common complications among medical tourists are infections.

Medical tourists seeking access to treatments that have not been tested and approved by regulatory agencies in the U.S. may not be aware of the risks they are taking with a practice that researchers at Canada’s Simon Fraser University call “circumvention tourism.” They warn of potentially enormous pitfalls, from shattered hopes to money-sucking quackery. “Individuals may be desperate for a cure and vulnerable to engaging in decision-making that’s predicated on hope,” they write, “without a full understanding of the likelihood of success.”

Perhaps the most common problems are the most obvious: Patients are traveling far from home to get treatment from doctors who cannot participate in long-term follow-up, often coming up against linguistic and cultural challenges. Much more prevalent than the risk of getting targeted by opportunistic criminals are these impediments to communicate their needs. “It might be a no-brainer,” observes Henry Ford Health, one of the largest health care companies in Michigan, “but if you don’t speak the local language, it might be difficult to explain any feelings of discomfort or apprehension as they come up.”

Long friendships have a way of shifting the space-time continuum. Once a close friendship has transcended years, decades — enough fashion cycles to see flannel and baggy jeans come back into style — that friendship can defy the traditional laws of physics. Sometimes it takes effort to untangle the order of past events, for example. This wedding, that funeral, some epic road trip: With a collective recollection, time can move in any direction and each recalled moment can occur differently with every new telling. A good friendship is a multiverse.

Time spent apart can also elasticize. In college, a friend’s summer abroad can feel like an eternity. But by the time you’re in your early 40s, you might not even remember the last time you saw each other.

That’s the particular quantum anomaly my friend Shaun and I were experiencing a few weeks ago on the phone. It had been too long since we’d gotten together for dinner, we agreed.

“A couple months at least,” one of us muttered.

Then we were both quiet for a second as we thought about the last time we’d actually hung out. My brain rolled back through the calendar. It wasn’t in winter or fall. Over the

BECAUSE WE THINK OF FRIENDS AS THE PEOPLE WHO PROVIDE RESPITE FROM THE OBLIGATIONS OF LIFE, BUT MAINTAINING FRIENDSHIPS CAN TAKE WORK.

summer, right? No, it was before then, too.

Shaun is my oldest friend. We met in middle school while competing in, of all things, a geography bee. As the other contestants melted away faster than the

Thwaites Glacier — just east of Mount Murphy, on the Walgreen Coast of Antarctica — we were among the four or five kids who answered correctly enough to become finalists. He eventually won. We were roommates in college. We were in each other’s weddings. We’ve been there for each other through a variety of traumas and triumphs, and we’ve stayed friends as we both built families and careers. He’s earnest to the point of quirkiness, and one of the most loyal people I know.

These days Shaun lives about 45 minutes away. We text each other a few times a week and chat on the phone every now and then. But as we thought back, we realized that it had somehow been more than a year since we’d seen each other in person.

I was stunned. Then I was disappointed in myself. How could it have been so long?

The truth is, we both travel for work. We’re both trying to be good husbands and fathers, and that takes a lot of time, too. We also each have our own separate interests and circles of colleagues and friends. A few

SOCIETY’S MESSAGE TO MEN IS GENERALLY SOMETHING ALONG THE LINES OF “SUCK IT UP.”

times we made plans for lunch or dinner, but then someone was out of town, or a kid was sick, or the weather was bad and it seemed easier to just do it a different day.

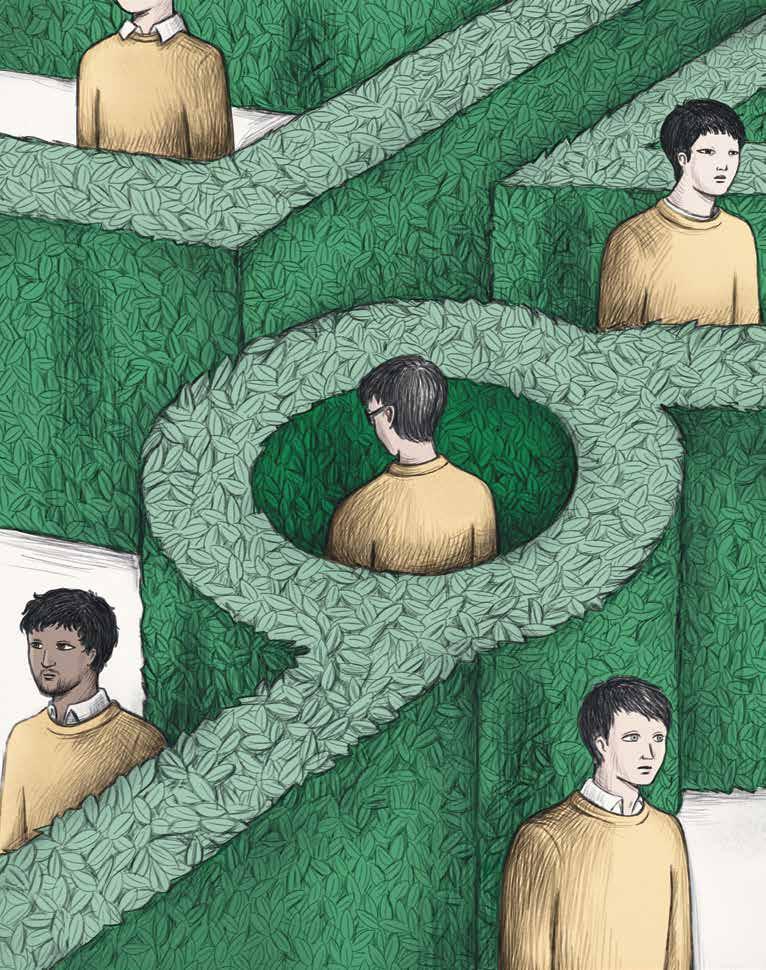

It sounds counterintuitive because we think of friends as the people who provide respite from the obligations of life, but maintaining friendships can take work. It’s something a lot of adults — especially men — struggle with.

Several studies over the last few years have shown that men are experiencing what’s become known as a “friendship recession.” It’s essentially an epidemic of loneliness. Surveys show that men in general have fewer close friends than women, and men today have fewer close friends than men 30 years ago. Since the early 1990s, the percentage of men who say they don’t have any close friends has multiplied several times over. Men are less likely than women to reach out to friends to talk about their personal feelings, too. Not coincidentally, men are also nearly four times as likely as women to die by suicide, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These trends started before Covid-19, but a global pandemic sure didn’t help.

I couldn’t help but wonder: Why is it so difficult for men to make and maintain friendships? What’s driving this loneliness?

IT MIGHT BE easy to dismiss any fret over the loneliness of men. After all, our society was built mostly by and ostensibly for men. And it’s still mostly men in control. Men are also, statistically, responsible for much more violence and much more likely to be the oppressor than the oppressed. Men, as a group, are not always the most sympathetic characters.

Still, this is a topic that should concern everyone.

At its worst, male loneliness can result in mass devastation. Think mass shooters, serial killers, barely visible tinderboxes vulnerable to the most dangerous types of terroristic influence. But even when it’s

nothing close to that bad, we’re still talking about millions of sad men — sons, brothers, fathers, husbands, neighbors — living out unfulfilling, lonesome existences. And then sometimes deciding not to live out that life after all.

To be clear, discussing the loneliness of men doesn’t invalidate the very real, stressful and often lonely experiences of women or marginalized groups. It’s certainly possible to be concerned about more than one problem at a time. Plus, the loneliness epidemic facing men is different — and not only because a wide swath of society doesn’t have much empathy for men.

Male loneliness isn’t a side effect of the way our society is structured. It’s a direct effect. Stoicism is a virtue in our culture. We often celebrate an exacting control of emotion. We might schedule our lives around watching two trained men get into a ring and try to knock each other out, but only a masochist would enjoy watching those same two men get into the same room and cry.

Look at the way literature and cinema has depicted traditionally successful men. There’s wealth and power and sometimes even the love of a family. But very few of them are surrounded by genuine friends, people they trust and depend on. The only exceptions: tales about war or team sports, or detective stories. Nearly every good detective has a colorful cadre of trusted associates that help solve the mystery. For the most part, though, our stories don’t have room for a lot of friends.

And yet, even happily married men need people outside their family to talk to, about both the banal and the painful. The need to trust and be trusted is inborn in our species. For proof, look no further than the copious number of American veterans who return from combat and report feeling a deep, abiding loneliness. They don’t necessarily miss the most terrible, traumatizing elements of war, but they do miss the camaraderie, the bonds forged through

those shared experiences. There’s a certain strength and confidence that comes from knowing others have your back, and that you have a purpose in protecting them.

The most obvious reason why most men might have such trouble with friendships is that whole discouraging vulnerability thing. Society’s message to men is generally something along the lines of “Suck it up.”

But that’s nothing new. Men have been encouraged to bury their emotions for much of modern history. If anything, our society is more open and less judgmental about the way we choose to live our lives than ever. And yet, male friendships have plummeted.

There have been a few big changes in our lives in the last 30 years, of course. The internet, and social media in particular, has completely transformed our social lives. It’s never been easier or faster to chat with someone, whether that’s via text or direct message. We’ve never been more connected to one another. But that ease of communication and the constant streams of potential distractions have led to even less of the earnest, rewarding interaction humans require. And the interconnectedness has undoubtedly made the world more polarized, more fractured. In a twisted irony, the more we’re able to connect, the lonelier we’ve become.

Add to that some of the socioeconomic developments of the last few decades. The economy is approaching Gilded Age levels. In a lot of cities, it’s harder than ever to buy a home. More men are living with their parents. More Americans say they feel a general sense of doom. None of these things are great for friendships.

But even if it’s especially pronounced here, America certainly isn’t the only country where men are lonely. One of the most extreme examples is Japan, where there is an entire class of mostly male social outcasts called hikikomori, which translates roughly as “extreme recluses.” They’re known to isolate in their homes for weeks — sometimes

months — at a time. Plenty are young, but the Japanese government estimates that there are more than 600,000 hikikomori between the ages of 40 and 64. Economists are concerned that the phenomenon is exacerbating an already dire demographic crisis.

In hopes of reintegrating some percentage of them back into society, a Japanese nonprofit has created long videos of live-action women, hoping to help hikikomori practice small human interactions like making eye contact.

IT’S NOT CLEAR from any of the current research what society writ large might need to do to stave off this friendship recession

SEVERAL STUDIES OVER THE LAST FEW YEARS HAVE SHOWN THAT MEN ARE EXPERIENCING WHAT’S BECOME KNOWN AS A “FRIENDSHIP RECESSION.” IT’S ESSENTIALLY AN EPIDEMIC OF LONELINESS.

— but being able to discuss this problem without anyone rolling their eyes certainly seems like a good start. If reasonable, rational thinkers don’t ever want to address the issue, the only people purporting to help lonely men will be the most toxic, destructive elements of society.

On a personal level, the answer is will and intentionality. Almost every study ever done on the subject indicates that people with more close friends tend to be happier and healthier. Humans are social creatures. Historically, we’ve solved our biggest problems with collaborations built on trust and reciprocity. Good friends can make the good times in life even better. In the bad

times, they can help ease the suffering. And the echoing silence of needing a friend and not having one can be devastating.

Like eating well and exercising, the best way to maintain close friendships is by making it a habit, a regular practice. Maybe that’s a monthly meal with the friends you’ve had since your haircut was deeply embarrassing. Maybe that’s a weekly pickleball game with a neighbor or one of the other dads from your kid’s school. Making friends can be intensely awkward. But so is going for a run if you haven’t done it in a while. Learning to trust and proving to others that they can trust you has to be a priority in life.

If it’s too uncomfortable, take a lesson from the fictional detectives who’ve cultivated those rosters of trusted cohorts. They always find some reason to visit their friends. They’re constantly proving that they’re there for one another. Even if you don’t have any capers to solve, deciding to see more of your friends is usually pretty great.

As for Shaun and me, the first thing we did was get together for dinner at a great barbecue joint between our respective hometowns. We also made a plan to do that more often, an intentional decision that we aren’t only going to see each other when life seems to be spiraling.

In a mesquite-scented wooden booth at the restaurant, we caught up on life. We talked about our families. We talked about work. We swapped a few new stories, and a few old stories, too. And we each mentioned some traveling we’d done — forever the same kids who met in that middle school geography bee.

We also experienced another violation of the laws of time and space. Sure, the clock has continued to tick since we’d last seen each other. It’s possible there’s a little less hair and maybe a little weight lost or gained. But it didn’t take long before we suddenly felt like absolutely no time had passed at all.

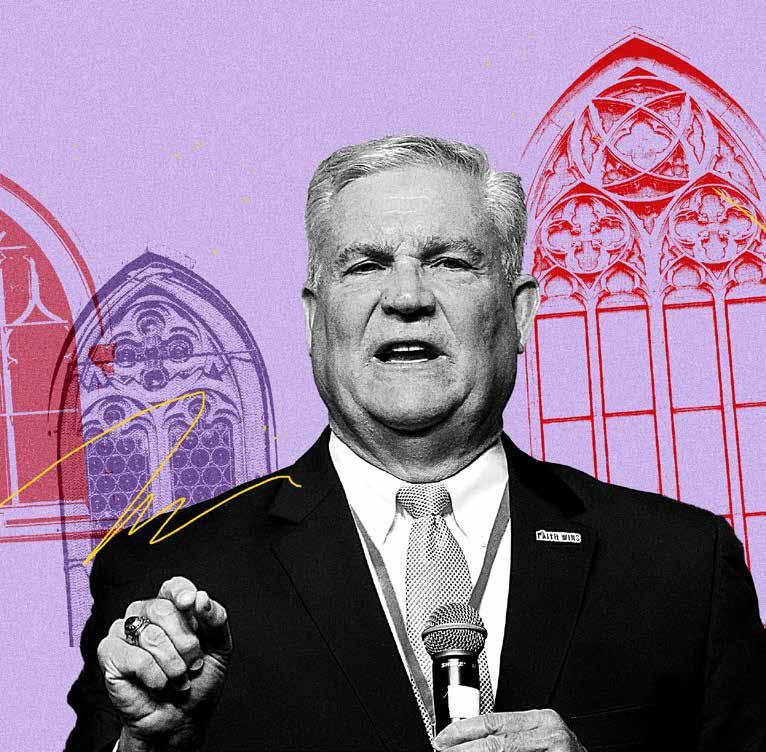

On a Sunday morning in 2006, Chad Connelly’s life began to unravel. As he tells it, he came home from a church service with his two sons in tow, ages nine and five. Upon entering the house, he found his wife of 18 years on the kitchen floor, lifeless. He sent his boys to their room and held her body. “I literally challenged God,” he recalls. “If all things work together for good to them that love God,” he prayed, “you’ve got to prove it.”

The following weeks were a blur. He fainted in the casket room. He hadn’t arranged for a headstone — “Nobody ever told me you had to go pick out a tombstone,” he recalls. He ached for his sons, who lost one parent to suicide and seemed to be losing another to distress. He agonized over his career as an engineer and a businessman. But he felt a nudge. “Sometimes in the lowest places, God says, ‘I’m not done with you,’” he says. “I believe he’s tapped us on the shoulder and said, ‘Now it’s your turn, go fix what’s going on in this nation.’”

Here in his story, Connelly says that he decided to follow the voice. Now, nearly two decades later, he works as one of the

most influential evangelical powerbrokers in American politics.

If Connelly had his way, every Christian in the country would vote. The country, as he sees it, is barreling toward a precipice: away from the Bible, away from conservative values, away from God. He believes that if he can train enough pastors to vote the “right way,” they can train their congre-

“I BELIEVE HE’S TAPPED US ON THE SHOULDER AND SAID, ‘NOW IT’S YOUR TURN, GO FIX WHAT’S GOING ON IN THIS NATION.’”

gants. “Political people walk into my meetings, and they see 42 pastors,” Connelly says. “I see 6,000 people, 8,000 people. They don’t know the multiplier effect.”

CONNELLY ISN’T A pastor. He’s not a big-money donor. Aside from a stint as the Republican Party chair in South Carolina, he’s never held

elected office. But within his nonprofit organization Faith Wins, Connelly has amassed a following of some 16,000 evangelical pastors, who look to him as a mentor as they navigate political issues. He speaks with an assuredness — a charm. And with conviction. To them, Connelly is the nonpartisan guide equipped to help them combine their faith with their politics. All he asks in return is they register their congregants to vote and teach them to vote “Biblical values.”

Faith Wins has pastors involved in all 50 states, though the highest concentrations are in early-voting states like Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina. Before the Iowa caucuses, Connelly blitzed the state with a group of pastors, hosting “caucus training” meetings in churches, where he guided congregants on where to vote, how to register and which values should drive their candidate choice. In New Hampshire, he held pastor briefings on issues like Israel and abortion. In South Carolina, he held closed-door meetings with Republican candidates themselves.

To Connelly, his work is an essential bridge between church and politics. But not

everyone sees it that way. Many Americans are uncomfortable with religious leaders operating in the political sphere. Trust in clergy hit a new low in a recent Gallup survey. In his new book, “The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism,” journalist Tim Alberta writes of the melding of the political right and the evangelical church. A new form of Christian nationalism, Alberta writes, allows evangelicals to embrace a

“Christian America that puts them at odds with Christianity.” They are able to replace their worship of God with the worship of a state: “They have allowed their national identity to shape their faith identity instead of the other way around,” he writes.

Connelly doesn’t escape Alberta’s pen. Connelly is “warm and self-deprecating,” he writes, but by bringing politics into the sanctuary, he’s doing inextricable damage to the church. “Did Connelly worry, in the

context of campaigning inside houses of worship, about a blurry line between engagement and idolatry?” Alberta writes.

IT IS BELIEVED the term “kingmaker” traces back to 15th-century Britain. The first was Richard Neville, the 16th Earl of Warwick, who — through a fortuitous combination of military prowess and familial prestige — helped remove both Henry VI and Edward IV from the throne by assassination.

In American politics, kingmakers operate with money and influence, not swords. There are the media magnates, like Rupert Murdoch. There are the billionaires — George Soros, the late Sheldon Adelson. There are webs of big-name advisers and big-money donors — the Koch brothers, Tom Steyer, Paul Singer. But it wasn’t until the 1960s that clergy became kingmakers in American politics the way we recognize them today.

Some pastors had always preached politics, to a degree — in colonial times, it was the custom in several New England states to “open each year’s session of the legislature with an annual election sermon,” according to archives from the American Antiquarian Society. But they were rarely entwined in the world of partisan politics. First, it was Billy Graham, working behind the scenes trying to sink John F. Kennedy for being Catholic. Then it was Jerry Falwell, diving headfirst into Republican politics with his “Moral Majority” movement.

Falwell’s overtly partisan maneuverings were concerning, even to Graham. “Evangelists cannot be closely identified with any particular party or person,” he said. “We have to stand in the middle to preach to all people, right and left.” That was a common position, at the time. At the height of Watergate, when prominent evangelicals were in Nixon’s corner, Barry Goldwater — the boisterous Republican senator — warned of religious influence in his party. “Mark my word, if and when these preachers get control of the (Republican) party, and they’re sure trying to do so, it’s going to be a terrible damn problem,” he told a journalist. “... Politics and governing demand compromise. But these Christians believe they are acting in the name of God, so they can’t and won’t compromise.”

But Falwell’s Moral Majority proved both influential and lucrative: The massive conservative lobbying group pushed Reagan into the White House in 1980, riding the support of over two million donors. By the early 1990s, the Moral Majority splintered. Cal Thomas, a conservative columnist, warned against the corrupting influence

that power had on the organization’s original intentions. “In the 1980s, people were led to believe that changing government leadership would keep their teenage daughter from getting pregnant, would clean up television, would reduce drug use, and restore ‘morality’ to America,” he wrote. “They believed it because we in the Moral Majority knew they wanted to believe it, so we convinced them it could happen. Many books were sold with quotations from the past, suggesting that the time of the Founders was more moral than the time of Carter and Clinton. (Somehow Republican presidents got a free pass even when they failed to do what we wanted.) But those of us who criticized liberal attempts to use government to impose what we regarded as an unrighteous standard were trying just as hard to use government to impose a righteous standard.”

“THEY HAVE ALLOWED THEIR NATIONAL IDENTITY TO SHAPE THEIR FAITH IDENTITY INSTEAD OF THE OTHER WAY AROUND.”

CONNELLY SEES HIS work as different from the old Moral Majority, as well as different from the Christian Coalition and other groups. Instead of spending each evening on television himself, he’d rather empower the local pastors to “do the work themselves.” But Connelly has made a career out of his influence. Even before his wife died and he pivoted his career, he’d already begun curating a public image as a motivational speaker and author. In the early 2000s, he began writing a book about “the solid values that once formed the bedrock of American society.”

In 2013, Connelly became the Republican National Committee’s first-ever director of

faith engagement. He hit the road, meeting with some 80,000 pastors (in his estimation) in the three years preceding the 2016 election, asking pastors: All things are spiritual, including so-called political issues. So why aren’t your congregants turning out to the polls? Come November 2016, evangelicals did turn out, in record fashion: 80 percent of white evangelicals backed Trump, the highest proportion for a Republican candidate ever recorded. Connelly was praised as the “unsung hero” of Trump’s election. Evangelicals made up over one-fourth of the 2016 electorate; it was Trump’s victory in a handful of evangelical-heavy swing states — Iowa, Florida, Ohio — that secured him the election.

This year, Connelly can’t formally endorse a candidate and maintain nonprofit status with Faith Wins. He’s instead resorted to encouraging his pastors to vote according to “Biblical values,” as he calls it. “I can take you to the scripture on life, marriage, Israel, religious liberty, sovereign borders,” he says. “We want to link arms on the issues that matter — that are biblical, basic, common sense, conservative issues.”

While a growing number of evangelicals are skeptical of Trump, Connelly says he would be doing the same work if there were an election this year or not. “You think this is about an election? No,” he says. He wants to see pastors and congregants involved in their communities. But, right now anyway, the pastors Connelly has trained aren’t meeting with local city councils or county mayors or even governors — they are focusing on a presidential election.

Perhaps it’s a symptom of a broader American fixation: a creep toward all politics becoming national, and a dissolution of interest in building strong communities from the inside out. When asked if he will see his work as a success if the pastors he's coached are active in their local communities, but the more liberal presidential candidate wins the election, Connelly takes a beat. “(The election) is a piece of the puzzle. And policies always have an impact. But getting these guys involved locally is a whole lot bigger deal to me.”

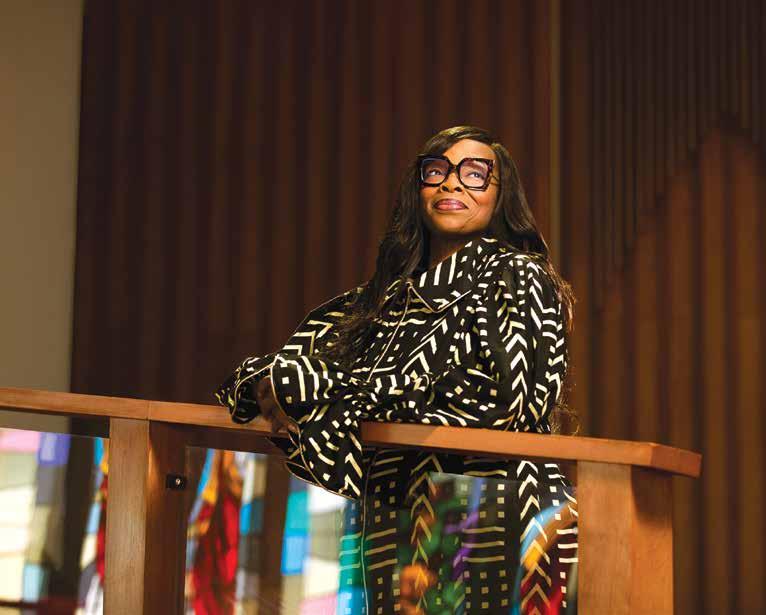

TERRENCE MILLICAN

Bishop at All Nations

Pentecostal Prayer Church

PHOTO BY NICOLÒ SERTORIO

TERRENCE MILLICAN

Bishop at All Nations

Pentecostal Prayer Church

PHOTO BY NICOLÒ SERTORIO

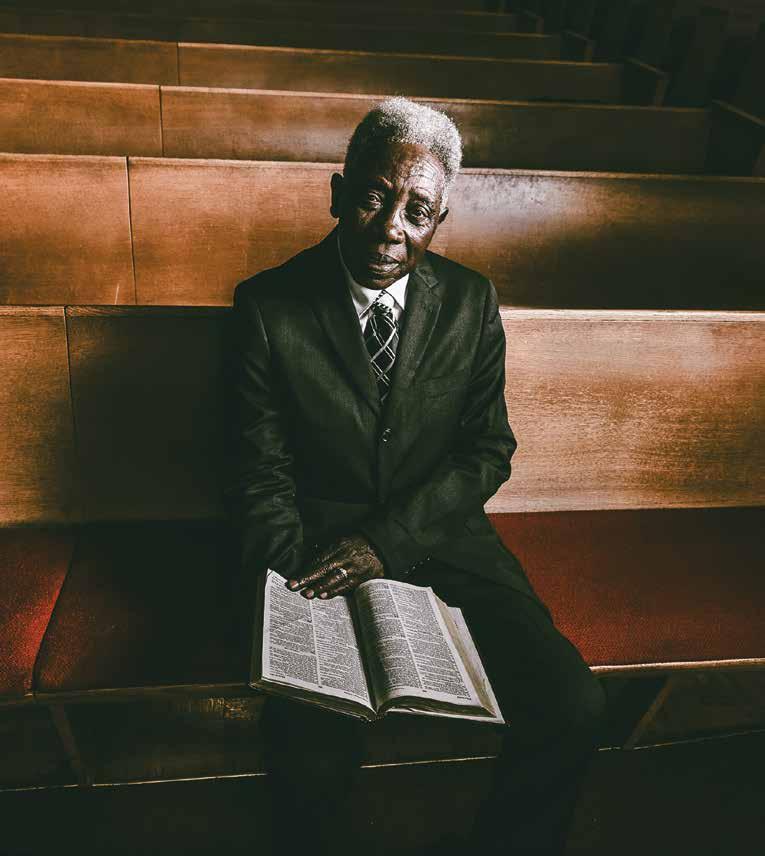

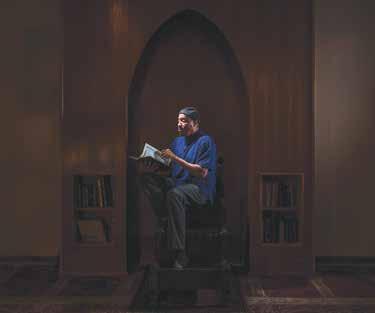

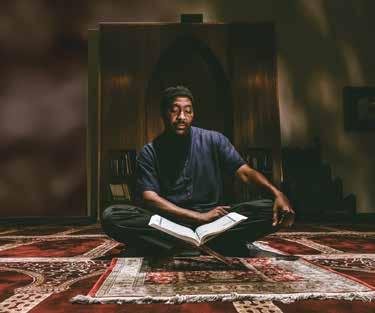

Spiritual leaders are healing one of America’s most heartbroken cities

NICOLÒ SERTORIO J MICHAEL TUCKER & PHOTOG R A PHY BY

N THE WOODEN PEWS that stretch like open arms across the chapel of the North Oakland Missionary Baptist Church, a man sat alone. The stillness of the chapel seemed to flow from him. His head bowed, he flipped through the thin pages of his Bible quietly — whatever was happening outside of these walls, it didn’t matter in that moment. When photographer J Michael Tucker, on the other side of the church, saw him, he “was overwhelmed by the beauty of this scene.” So, he captured it, and with it the legacy of the Rev. Sylvester Rutledge Jr., the late pastor of North Oakland Missionary Baptist Church, the second-oldest Black church in Oakland.

Tucker and fellow photographer Nicolò Sertorio have spent years documenting the spiritual leaders of Oakland, California, in their joint project, “Sacred Paradox,” which explores the intrinsic wisdom, transformative potential and profound connection each of these leaders have to their hometown. It comes at an inflection point for Oakland. While the rest of the nation is seeing falling violent crime rates and felonies, in Oakland they’ve risen. Burglaries have increased by nearly 25 percent. Police services and violence prevention initiatives have been curbed. Businesses have left the city due to break-ins and crime, while an ever-growing homeless population continues to lose the battle against a stilted housing economy.

Phyllis Scott, pastor at Tree of Life Empowerment Ministries, believes that now, more than ever, “the community has to go back to caring about one another.” This conviction is one that connects each spiritual leader featured in “Sacred Paradox” — regardless of denomination, religion, race or identity. In it lies the hope that the togetherness that Oakland so desperately needs can be resurrected. “We’ve turned our back on the everyday people and it’s time for us to turn around and see them and rebuild this city,” she says. And it simply starts with faith.

By Lauren Steele

Late pastor at North Oakland Missionary Baptist Church

For over three decades, the Rev. Sylvester Rutledge Jr. pastored at North Oakland Missionary Baptist Church, where he led the second-oldest historically Black Baptist congregation in Oakland. The Rev. Rutledge moved to Oakland in 1964 after leaving family roots in Alabama and serving in the Air Force. Under his leadership, a 65-unit affordable housing project was opened by the church in 2003, marking a step forward in Oakland’s housing crisis.

Pastor at Plymouth United Church of Christ Marjorie Wilkes Matthews didn’t intend to become a pastor, but the open arms in her church have proved to be her “most profound treasure.” At a time when many churches are shrinking, Plymouth United is growing. “It’s a radically welcoming church,” she says. “The sense of ‘welcome home’ is the thing so many people here feel.”

“Nobody wants to see people suffering.”SUNDIATA RASHID

Imam at Lighthouse Mosque

Sundiata Rashid was raised in East Oakland, where he found religion as a teenager. “Shariah, the word for Islamic Law, means ‘the road that leads to water’ in Arabic,” he says. “In the desert, everyone wants a road that leads to water. People have to live their own lives. What they want to do is what they have to live with. I try to not be judgmental.”

“We are still called to lift our voice on behalf of the voiceless and stand in the gap for those unprotected.”

JACQUELINE THOMPSON

Pastor at Allen Temple Baptist Church

Jacqueline Thompson was 12 when she dedicated her life to God in Allen Temple Baptist Church. In 2019, she became the first woman to serve as senior pastor in the church’s 100-year history. “This mission still ignites me as it did that girl in the balcony many years ago,” she wrote in The Oakland Post. “We are still called to serve the least, the lost, and the left out. We are still called to lift our voice on behalf of the voiceless and stand in the gap for those unprotected.”

Former stake president in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

When data showed homelessness spiking in a span of two short years in Oakland, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints partnered with government officials to build nine affordable housing units. “We are happy to be able to work with those most in need, with those in our community,” says President Darryl Rains.

Yoshi Akiba was born in Japan in 1942 and was orphaned during World War II. After moving to Maryland as a young woman, she found a love for music. With her husband, the Rev. Gengo Akiba, she moved to Oakland, opened the Oakland Zen Center in 1994, and has since co-founded the nonprofit 51Oakland to bring music and art to underserved Oakland public schools.

Rabbi at Chabad Center for Jewish Life

In the early 1900s, the Oakland area had one small synagogue. Today, there are more than 70 centers for Jewish faith, including the Chabad Center for Jewish Life, established by Rabbi Dovid Labkowski to create an “inclusive, vibrant and engaged community in Oakland.”

“The word of God says love is the greatest commandment. Can you imagine if we really loved each other, how we could turn this city around.”

PHYLLIS SCOTT

BY JESSE HYDE

BY JESSE HYDE

KIBBUTZ BE’ERI HELPED BIRTH THE ISRAELI NATION. THEN CAME OCTOBER 7

PHOTOGRAPHY BY

DANIEL ROLIDERThe pioneers came to make the desert bloom. Hafrachat hamidbar, that’s how they said it in Hebrew, and while Uri Hoter never used the phrase himself, he heard it often as a child.

By the time he was born in 1976, the kibbutz, known as Be’eri, had been around for 30 years. Its founding was legendary, not just among the pioneers, and not just in the kibbutz, but in Israel itself, because it was part of the founding story of the country.

Uri didn’t remember all the details. What he did remember was something called the White Paper, which laid out the laws of the land, back when the British were in charge. The law restricted where Jews could settle but had one strange loophole — that any settlement with a completed roof could not be torn down.

And so on October 5, 1946, a group of 1,000 pioneers pushed into the desolate Negev desert under the cover of darkness. They fanned out in 300 trucks — loaded with mattresses, bed frames, fence posts and buckets of nails — until they arrived at what would one day be known as the 11 Points. They worked all night, and by the time the sun rose over the rocky soil, they had built 11 settlements. Be’eri was one of them.

The British weren’t happy, but according to their own laws, the settlements could not be destroyed. The pioneers knew Partition was coming — that the land would be divided between the Arabs and the Jews — and they figured if they could essentially lay claim to open land in the desert, it would be given to them. They were right: The 11 settlements would eventually help form Israel’s border.

Uri heard this story so many times as a child, he lost count. Its repetition

underscored its importance. Within the insular kibbutz, he knew of no other version. He didn’t know others told the story quite differently, not of triumphant return and making the desert bloom, but of colonialism and conquest, of land theft and expulsion. Only later would he learn that the violence that would mark his life — the rocket attacks and the suicide bombings, the air raid sirens, the countless skirmishes in Gaza and the West Bank — had its roots in this story.

No, as a child, the story was not complex. It did not need to be told with caveats and apologies. It was simple and pure, like a folk story, or something from the Bible, perhaps the Book of Genesis, because it explained the beginning. The beginning of Be’eri, the beginning of Israel, the beginning of him.

NEXT YEAR IN JERUSALEM. For centuries, Jews cried out these words during Passover, dreaming of a return to Jerusalem, but it was just that — a dream. At the turn of the 19th century, Jews from all over the world, inspired by the idea of a Jewish homeland, dropped coins into the Jewish National Fund’s Blue Boxes to buy land in Palestine, making the dream of Zionism real. By 1948, the year Israel became a state, waves of Jewish immigrants over the previous decades grew to a flood. They came from Iraq and Yemen, from Germany and Poland and Lithuania. Some were Holocaust survivors — 140,000 between 1948 and 1952 — and some were refugees fleeing Arab countries (nearly 1 million during this period).

The kibbutz, though, was a symbol of the Jewish people’s rebirth. By 1950, there were 214 in Israel, small communal villages.

Because Jews had been prohibited from owning land in many of the countries from which they immigrated, to be a farmer was noble, to work the land sacred.

By the 1980s, the desert of Negev had truly bloomed: The homes in Be’eri were arranged in orderly rows, painted white with tile roofs. Life had also changed. The early settlers gathered every Yom Kippur to tell the story of the 11 settlements, how as children they chased lizards and butterflies, walked barefoot among the thorns to make their feet tough like the Bedouins. But

those were the old stories. By the 1980s, life had become much more structured, like life in America: Uri had orchestra practice and basketball games. There was high school to prepare for and after that, mandatory military service and then college.

Still, when Uri visited his uncles in Tel Aviv, he realized how unusual life in the kibbutz was, that Israel was modernizing and drifting from the socialist ideals upon which it had been founded. The kibbutz, it seemed, was 15 years behind. In the kibbutz, the TVs were still black and white. If

a relative from Haifa or Be’er-Sheva called the rotary phone, which hung in the dining hall, you’d have to go fetch whoever they were calling, which sometimes could take half an hour. In the kibbutz, there was only one kind of shampoo. In fact, Uri thought conditioner was called Rinse because that’s the only brand the committee bought. He was fascinated by America, but felt like he lived in the Soviet Union.

He had one pair of shoes for summer and one for winter, and Uri looked forward to getting a new pair. It was a ceremony of sorts, a ritual, not quite like Passover or Hanukkah, but to Uri just as special. They’d go into the communal dining hall and pick their shoes from boxes, arranged by size. “Please let me get sneakers this year,” Uri would beg his mom, but she would always insist he pick sturdy work boots that would last all year. In the summer, he wore sandals. They were called Bible sandals because they looked like the sandals David once wore.

And yet, as impervious as Be’eri seemed, the world was seeping in, forcing the kibbutz to modernize. In 1985, the secretariat committee, which made all decisions for the kibbutz, voted to eliminate the children’s house. Since Degania, the first kibbutz in Israel, the children’s house had been a central feature of all kibbutzim. It had arisen partly out of necessity; to build a community in the swamps of Galilee or the craggy hills of Golan, all abled-bodied adults needed to be free to work, including the mothers. The children, then, lived in their own house, where they were taught and tended to by a nanny, or metapelet

Uri didn’t mind living in the children’s house. He could only remember once or twice, when he was two or three, going out into the night and walking to his parents’ house, and through tears asking to sleep in their bed. His mother firmly said no and brought him back.

And yet, he grew to like the independence, and he grew to form strong bonds with the other children his age. They were like his brothers and sisters.

But other people hated it: Some moms refused to put their children there, and so, the

kibbutz eliminated the house. This meant greatly expanding the size of the homes in Be’eri, to accommodate actual families. The decision came at a time of deep financial crisis for Israel, of crippling inflation. Many of the kibbutzim in the country, which had been propped up by government loans, could not pay their debts and collapsed.

Be’eri was different. It was much more than just a collective farm by 1985. It still had miles of fields, producing lemons and grapefruit and cotton and wheat, but its economic engine was a large printing facility, which printed all the driver’s licenses in the country and many of the credit cards. Most born into the kibbutz worked within its walls — Uri’s father worked for a time in the printing plant and his mother worked at the high school — but even those who worked outside the kibbutz still put their salary back into a communal pot. Because of this, and the success of the printing facility, Be’eri was rich. It didn’t just have a swimming pool like other kibbutzim; it had a tennis court, a fleet of over 100 cars and a fund that paid for the education of all children born on the kibbutz, all the way to a Ph.D. There was also money for vacations — a month in Australia, three weeks in Nepal and Tibet — and weddings, and parties, and jeep excursions into the Negev.

While other kibbutzim were declaring bankruptcy, or succumbing to privatization and the allure of capitalism, Be’eri flourished, and held to its founding principles. The entire kibbutz still shared its meals in a communal dining hall, gathered together for holidays, and cared for each other like a large family. Few left; in fact, there was a waiting list to get in.

Wandering the kibbutz on spring mornings, while his mother listened to Leonard Cohen records and the old men sat on porches smoking and reading the newspaper, Uri felt safe, like he was living within a walled garden.

But beyond the yellow gate of the village, there was another world, just five kilometers away. And in that world, something dangerous had begun to take root.

IN HIGH SCHOOL, Uri mostly hung out with kids from Be’eri, or other kibbutzniks in the

area. Each year, volunteers from the U.K. and Holland would come to help in the garden or the fields, a sort of rite of passage for Jews outside of Israel. The volunteers lived in a row of small, cramped houses in a neglected part of the kibbutz, which was jokingly referred to as the ghetto. Uri was fascinated by them, but too shy to really become friends, too embarrassed of his English to have more than a fleeting association.

It wasn’t until he was 18, when he moved out of the kibbutz for the first time for military service, that his perspective really began to broaden. After the equivalent of basic training, he was selected for an elite intelligence unit stationed in Tel Aviv. Because everyone in Israel is required to serve in the military, most units include all social classes and backgrounds: poor kids from Jerusalem, devoutly religious men who wrap tefillin around the arm during morning prayers, the Tel Aviv upper crust. But Uri’s unit was different. It seemed to only include the well-educated of Israeli society.

Uri’s understanding of Israel, and its place in the world, expanded during this time. While he had always felt safe in Be’eri, he had known Israel had enemies. In 1980,

IN THE WAKE OF THE OCTOBER 7 ATTACK, WEEKLY PROTESTS WERE STAGED AT WHAT BECAME KNOWN AS THE HOSTAGES SQUARE, IN FRONT OF ISRAEL DEFENSE FORCES HEADQUARTERS, INCLUDING HUNDREDS OF EMPTY CHAIRS, REPRESENTING HOSTAGES TAKEN BY HAMAS.

when he was four, Palestinian terrorists had cut the fence on the border of Israel and Lebanon and snuck into a kibbutz called Misgav Am. They made their way to the children’s house, where they killed the kibbutz secretary and a two-year-old toddler and then snatched two babies from their cribs. They then headed to the second floor, where more children were sleeping. With these hostages, they barricaded themselves and a standoff with Israeli special forces ensued, climaxing the next day with the death of the terrorists and an Israeli soldier.

Everyone knew this story, but in Be’eri it felt remote. Now that he was in the military, he realized that while Israel was strong, and

Even though the kibbutz sat on the border from Gaza, he didn’t think it was a target, or even in danger. Many of the older kibbutzniks still communicated with Gazans who had once worked on the kibbutz, and still considered them friends. Be’eri included world-famous peace activists, like Vivian Silver, and they viewed the plight of the Palestinians with sympathy. Israel had become an occupying force in Gaza: With Egypt, it effectively controlled Gaza’s borders and did not allow it to operate an airport or seaport, crippling its economy. Israel cited security concerns as justification, but the blockade was devastating: Unemployment levels in Gaza were among the highest in

but this was a one-time thing, for the rest of his life. Once he came back, he could not leave again.

THE BOMBINGS, THE rockets, the mortar fire became routine. At work in Tel Aviv, Uri would continue his meetings while running to a bomb shelter. He’d be on the highway, driving to the kibbutz for the weekend, and suddenly he’d hear the air raid sirens. Everyone would pull over, get out, and lay down on the asphalt, until the sirens went off and then get back in their cars and carry on as if nothing had happened. In Tel Aviv, you had 90 seconds to get to a bomb shelter when the sirens sounded. In a kibbutz

could defend itself, it was also surrounded by countries that wished it didn’t exist.

Then came the Jaffa Road bombings. Early on the morning of February 25, 1996, a bus exploded in Jerusalem, killing 17 civilians and nine Israeli soldiers. A week later, another suicide bomber boarded another bus on the same route, killing 16 civilians and three Israeli soldiers. The day after that, at the biggest shopping mall in Tel Aviv, another suicide bomber blew himself up, killing 13 and wounding 130 more. Three suicide bombings in nine days. The mastermind of the attacks was a man named Mohammed Deif, the eventual head of the Qassam Brigades, the military wing of the Islamist organization known as Hamas.

By the early 2000s, there were so many bus bombings in Tel Aviv that Uri began scanning the faces of those on the buses and looking for anything suspicious, like a bulky coat, or a large bag. Sometimes, he just had a feeling he shouldn’t get on, and that was enough.

By this point, Uri had finished his military service and was living in Haifa to attend college, where he was studying computer engineering. On weekends and holidays he returned to the kibbutz, which felt a world removed from the bus bombings and terror in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

the world, with 1.3 million people requiring food assistance. The kibbutz began collecting money and sending it to Gazans. They arranged rides for Palestinians to hospitals in Israel.

The people of Be’eri wanted a government that pushed for peace, not war, and even when Qassam rockets started landing near the kibbutz, they remained committed to peace. Sitting in bomb shelters, they reminded their children that the kids in Gaza were scared too, that it wasn’t the Palestinians who hated them; it was Hamas, a terrorist organization.

By 2006, Uri started to bristle at the demands of the kibbutz. He was 30 now, a full member, with all the privileges that entailed. Be’eri had become one of the wealthiest kibbutzim in all of Israel, and the days of having one pair of shoes and a pair of sandals were long gone. To live in Be’eri now was sort of like living in a country club, or a gated community, and a very nice one at that, with a long waiting list that essentially meant unless you were blood, or married the blood of the founders, you were not getting in.

And yet, he no longer wanted to have to run his decisions by someone else. In 2008, he asked to live in Tel Aviv for two years. The secretariat granted him permission,

like Be’eri, which sat on the border of Gaza, you had 15 seconds. The rocket fire became so persistent, a site started in 2014 called israelhasbeenrocketfreefor.com. From its launch until its last update in 2019, not a single month had passed without a rocket landing in Israel.

Uri decided not to return to Be’eri. He loved life in Tel Aviv — the art galleries, the restaurants, the nightlife. He needed culture. He’d grown up playing the drums and now he played in a band. He worked in the Tel Aviv tech sector and felt content with how his life had turned out. It was a far cry from the life of the pioneers, but in a way, he embodied the journey of Israel itself. Once a kibbutznik, he was now fully enmeshed in Israel’s future. Start-Up Nation, they called Israel. The Silicon Wadi. He still returned regularly to the kibbutz to visit his parents, who had divorced when he was a child but remained in Be’eri, just in separate houses. He kept in close contact with the kids born in his year. Most had moved to the big cities of Israel — Tel Aviv and Haifa — but a few from his birth year still lived in the kibbutz, and were raising their kids there. They weren’t chasing lizards like the pioneers had, but the quiet, pastoral life persisted. There were still orchards and gardens of flowers. Nights of

stargazing and bonfires. Hikes in the Negev and picnics on summer afternoons. Uri may have chosen a different life, but he still understood the allure of the kibbutz, why most of them had never left.

On October 6, 2023, he left his apartment in downtown Tel Aviv before dusk. It would take him about an hour to drive to Be’eri. That night the kibbutz was holding a birthday party. It had been 77 years since the pioneers loaded up their trucks, set out into the desert, and built the 11 settlements.

who was also staying at their mom’s house for the weekend, came into the kitchen. She was still in her pajamas.

“What’s going on?”

Uri shrugged. He had not heard the air raid siren. Some kind of military training exercise perhaps? Nothing to be worried about.

“I don’t know,” he said, reconsidering. “I think we are bombing Gaza, and if we are bombing Gaza, they are probably going to bomb us. Maybe let’s go down to the safe room just in case.”

Tonight, the kibbutz would gather in the auditorium where they held concerts and screened movies. The children of the pioneers, now in their 70s and 80s, would take the stage to tell their origin story. They would tell stories of the war of independence, how people like Uri’s uncle, for whom he was named, had died to defend their new nation. And then they would sing the song of the night of the 11 settlements. They would remember how things had been, and how, in spite of how much Israel had changed, Be’eri had not changed so much.

After the event, they would spill out of the auditorium and linger by the water tower, or in front of the library and the swimming pool and chat late into the night, smiling, aglow, swapping old stories and memories of happy times, making each other laugh so hard they were crying, the way you do with friends who feel like family. And then they would stumble to their beds, with that warm feeling in your belly of being among those who love you most, behind the security of their yellow gate.

They would have no idea of the horror about to unfold.

URI WAS STANDING in the kitchen of his mother’s home drinking coffee when he heard the first bombs. It was October 7, the morning after the party, just after 6:30 a.m. More bombs, more rockets. He sipped his coffee. This was unusual. His sister Noa,

Across the kibbutz, from phone to phone, WhatsApp was lighting up with messages. Two men on a motorbike wearing the green bandanas of Hamas had been spotted. They were carrying rifles. In Uri’s neighborhood, known as the Olives, pickup trucks loaded with gunmen from Gaza were arriving. What looked like Hamas commanders were giving instructions, not just to men dressed like soldiers, but to young men in polos and jeans, who carried machetes and knives.

At the yellow gate, two bearded men approached. They wore fatigues and body armor, like U.S. Special Forces. They moved cautiously, their rifles extended, the safety off, the trigger finger at the ready.

A car approached. The men slipped into the shadows. The sensor on the gate read the pass on the car’s dash, and the gate opened. The men in the fatigues reemerged and opened fire, the bullets ripping through the car and killing the two young men inside.

Unaware of what was happening outside his mother’s home, Uri had left the safe room, because the routine was to stay for a few minutes and then leave.

“I think I hear gunshots,” his mother said. Uri could hear them too. His mother’s phone buzzed. It was the kibbutz app for all residents. “Suspected infiltration,” it read.

Every home in Be’eri had a safe room of reinforced concrete and blast-proof windows. Because rocket attacks were so common, safe rooms doubled as bedrooms, typically for children. Most did not lock

from the inside as a safety precaution: A safe room was designed to protect residents from a rocket attack, and if a rocket caused, say, your roof to cave in, rescuers needed to be able to open the door. This meant the only way to keep your safe room shut, if someone wanted to get in, was to hold the handle.

But the safe room in Uri’s mother’s house was unique. It had two doors, an exterior iron door and an internal wooden door. And the iron door locked from the inside

“We need to go to the safe room,” Uri told his sister. “Get mom.”

Once inside, they pushed a dresser against the door, another layer of security. Uri still wasn’t sure what was happening, but he figured they should not sit near the door or the window, where bullets could possibly hit them. As luck would have it, they also had a piano inside the safe room. He whispered to his sister that if they heard someone enter the house, they’d push the piano in front of the door too, making it nearly impossible to enter. Uri turned off the lights and shut the protective metal plating over the safe room’s one window. They were now in darkness.

Uri’s mom’s phone lit up. Another message from the kibbutz security team. They were handling the incident, they assured the kibbutz.

What no one knew, however, is that the head of the security force, a man named Arik Kraunik, had already been ambushed,

about 100 meters from the kibbutz gate. He had the only key that opened the armory that held M16 rifles and ammunition. With no way to get inside the armory, the remaining six members of the security force had nothing more than handguns and single shot rifles. And not nearly enough ammunition. The army, meanwhile, was pinned down, and wouldn’t arrive for hours.

Across the kibbutz, gunmen were going door to door. They dragged old women from their homes and paraded them down the streets of the kibbutz and then stuffed them in the backs of trucks. Later in Gaza, social media would show Hamas soldiers returning with hostages. The body of a dead Israeli soldier was dragged from the bed of a truck and surrounded by a mob that stomped the corpse. A young woman taken hostage was pulled from the back of a dusty jeep, barefoot and cuffed. Her sweatpants were soaked in blood and blood trickled from her face and hands. “Allahu Akbar,” the crowd chanted.

In the safe room, the sound of gunfire was growing louder. The assailants were drawing closer.

Uri had decided that he would monitor incoming information and choose what to share with his mother and sister to keep them calm. His mother, who was 71, had gone into what seemed to Uri a dissociative state, but Noa was on the verge of a panic attack.

“Where’s the dog?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” Uri said. He realized they’d left their dog, a spaniel named Luna, outside the safe room.

“We need to open the door to let her in.”

“No way,” Uri whispered. “The next time I’m going to open the door is when I know there’s an Israeli soldier on the other side.”

Uri could not figure out why the military had not yet arrived. It was 10 a.m. and they’d been in the safe room for three hours. He started to worry about his mother’s asthma. He knew she’d stay calm, even if the terrorists entered the house, but worried she might cough. He wanted to ask her if she had her medication but decided against it. If she didn’t have it, she might panic and start coughing and then they’d be discovered.

From phone to phone, on the kibbutz private messaging app and WhatsApp groups for mothers and teenagers, the messages were coming in a torrent of panic and disbelief.

Why is the army not coming?

We are going to die. I never thought we would die this way.

Several wounded: come quickly! Now! Please!

Dad, Carmel is taking his last breaths.

Please, please, please, please make it stop. They’re here.

And then came the sickening realization that the safe room wasn’t that safe, after all. When the terrorists could not break open a safe room door, they would set the house on fire, forcing the most hellish of Faustian bargains: Open the door and be kidnapped or killed, or burn alive.

Someone was knocking on their door loudly, yelling something in Arabic. Uri motioned for his sister to help him push the piano in front of the safe room door. When they finished, they retreated to a corner of the room where bullets couldn’t hit. Noa started trembling uncontrollably and tears were streaming down her face. Uri pulled her close. “Listen, listen, I think they are going to shoot at the safe door, and they might explode something. We need to stay quiet. Even if we are afraid.”

The sound of gunfire echoed through the

safe room in a thunder. They were shooting at the door, as Uri had feared. Then he heard what sounded like a grenade explode. And then silence. Arguing. And then the men left and the house fell silent again.

Uri figured they had started a fire, but he wasn’t sure, so he put his hands against the safe room’s metal door to see if it was getting hot. He felt nothing. He turned on the light on his phone to see if any smoke was coming in under the door. Nothing. But moments later he saw the first wisps of smoke coming from the vents above him. Panic coursed through his body. The house was on fire.

Uri stripped off his shirt and held it against the crack between the safe room door and the floor, while Noa soaked her shirt in water and then held it against her nose. He instructed his mother to do the same and motioned for Noa to turn off the air conditioner, because it was circulating smoke into the safe room. They sat there for what felt like an hour. Miraculously, the fire went out.

As the hours passed, they heard more footsteps, but it sounded like people were simply ransacking the place. He heard voices talking in Arabic, arguing, and then the sounds of drawers opening and closing, furniture being upended, glass smashing. Laughter. For hours, people came and went.