THIS IS THE PLACE FOR

We have 11 perfect venues for your event.

YOUR PERFECT EVENT

Utah State will leverage its expertise to drive innovation, nurture strong partnerships, and develop ethical leaders and a skilled workforce to meet the challenges of the modern digital era.

- Elizabeth R. Cantwell USU’s

17th President

Students, Faculty and Staff Proudly Welcome Elizabeth R. Cantwell to Where the Sagebrush

Grows

“I feel like I got stuck in a situation. I’m this close to going back to Kabul.”

Picture yourself winning. PER SISTENCE

Misty Copeland

“I have feared bedtime since my earliest memories. I slept with a baseball bat. I fixated on the burglar alarm.”

Peters is the María Rosa Menocal Professor of English and professor of film and media studies at Yale. A media historian and theorist, he is the author of several books, most recently, “Promiscuous Knowledge: Information, Image, and Other Truth Games in History,” coauthored with the late Kenneth Cmiel. His commentary on what artificial intelligence tells us about ourselves is on page 19.

Phetasy is a writer and standup comedian. A columnist and contributing editor for The Spectator, her work has also been published in Tablet Magazine, The Federalist, the New York Post and New York Daily News. She hosts the “Walk-Ins Welcome” podcast and YouTube program “Dumpster Fire.” Her essay about post-40 motherhood is on page 24.

Kix is a deputy editor at ESPN.com and the author of two books: “The Saboteur” and “You Have to be Prepared to Die Before You Can Begin to Live,” which was published in May. His work has also appeared in Esquire, GQ, The New Yorker and The Atlantic. His feature story on the bond between a soldier and his interpreter from Afghanistan is on page 36.

An advocate of religious diversity, Patel is the founder and president of Interfaith America, which works with governments, universities and private companies to make faith a bridge, not a barrier, of cooperation. He has written five books, including, “We Need to Build: Field Notes for Diverse Democracy.” His essay titled “The Paradox of Privilege” is on page 70.

Ortega is a graphic designer, illustrator and art director from Colombia based in New York. He previously worked as a designer for Milton Glaser, Sagmeister Inc. and Penguin Random House. He is the recipient of several prestigious honors, including multiple best illustrations of the year awards by The New York Times, and was named NBC’s Top 20 Latino Artists to Watch in 2021. His work is on page 70.

Bassos is a photographer whose portfolio spans corporate portraits, families and weddings, editorial, commercial and documentary work. Her work has appeared in ESPN, The New York Times, Travel + Leisure, Refinery29 and Chicago Magazine, among other publications. She divides her time between Denver and Chicago and her photography is on page 36.

JOHN DURHAM PETERS

PAUL KIX

STEPHANIE BASSOS

BRIDGET PHETASY

NICOLÁS ORTEGA

EBOO PATEL

ACADEMIC PROGRAMS

COLLEGE OF DENTAL MEDICINE

• Doctor of Dental Medicine (DMD)

• Advanced Education in Orthodontics & Dentofacial Orthopedics (AEODO) Residency Program

Advanced Education in General Dentistry (AEGD) Residency Program

COLLEGE OF GRADUATE STUDIES

• MS in Biomedical Sciences (MBS)

• MS in Pharmaceutical Sciences (MSPS)

COLLEGE OF MEDICINE

• Currently in Development

COLLEGE OF NURSING

Accelerated Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN)

• Master of Science in Nursing/Family Nurse Practitioner (MSN/FNP)

COLLEGE OF PHARMACY

• Accelerated Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD)

• Dual Accelerated Doctor of Pharmacy/MS in Pharmaceutical Sciences (PharmD/MSPS)

– 3+1 Program

FACING THE FUTURE

Iwas a freshman at BYU when my friend Drew asked me if I wanted to go check out this new thing called the internet.

“What’s that?” I asked.

He shrugged. “Let’s go find out.”

As I recall, we went to the Tanner Building, where BYU holds most of its business classes, and sat behind his brother for 45 minutes while he downloaded a picture of Kurt Cobain.

“The internet’s dumb,” I said as we walked back to the dorms.

Drew told me I didn’t get it.

I spent the next two years on a Latter-day Saint mission in the Amazon, where most people didn’t even have a phone (not the kind you hold in your hand and check every 2 minutes for email; the kind you plug into a wall). When I got home, I felt like Rip Van Winkle. Everyone had dial-up internet. Everyone had email. Drew was right: the internet certainly wasn’t dumb, and you could do more with it than download pictures of Kurt Cobain.

The internet changed our world in ways I could never have imagined in 1995. It rendered much of what I once loved — bookstores, magazines, mix tapes, Blockbuster Video — either obsolete or nearing extinction. Maybe that’s why I’ve always been a late adopter of new technologies and highly skeptical of the hype around them. I’m a Luddite at heart. Or I just don’t want the world to change.

I thought of my first experience with the internet this summer, when my brother was telling all of us siblings that artificial intelligence was going to take our jobs, and make us, well, obsolete. I

looked at AI-generated art and snickered. I read emails composed by ChatGPT and scoffed at the notion a machine could ever replace a writer.

“AI is dumb,” I typed to my brother. Before I hit send, I paused. I was composing the message on a smartphone, which corrected my misspellings in real time, and if I changed the settings, could predict with frightening accuracy the word I planned to type next.

There’s no denying the internet has completely reordered our world. And I suppose if past is prologue, so will AI

Whether the world is better before or after the Internet is a column for another day. What seems clear to me is that there’s no escaping it. I’ve been back to the Amazon half a dozen times since my mission on reporting trips. The last time I was there, in a place you can only get to by boat or airplane, it seemed everyone, even the kids, had a smartphone and that it occupied their attention the same way it does ours.

If there’s no escaping a world reshaped by technology, how do we live in it? That’s the driving question behind this month’s cover story, The Future is Here: How AI will remake the world. As Yale professor John Durham Peters writes on page 19, the question isn’t whether machines will replace us, or even if they present unprecedented challenges. As Peters notes, the challenge we’ve faced as humans has always been the same: to transcend who we are, to be something more.

EXECUTIVE EDITOR HAL BOYD

EDITOR JESSE HYDE

CREATIVE DIRECTOR ERIC GILLETT

MANAGING EDITOR MATTHEW BROWN

DEPUTY EDITOR CHAD NIELSEN

SENIOR EDITORS

JAMES R. GARDNER, LAUREN STEELE

POLITICS EDITOR SUZANNE BATES

EDITOR-AT-LARGE DOUG WILKS

STAFF WRITERS

ETHAN BAUER, NATALIA GALICZA

WRITER-AT-LARGE

MICHAEL J. MOONEY

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

LOIS M. COLLINS, KELSEY DALLAS, KYLE DUNPHEY, JENNIFER GRAHAM, ALEXANDRA RAIN

ART DIRECTORS

IAN SULLIVAN, BRENNA VATERLAUS

COPY EDITORS SARAH HARRIS, VALERIE JONES, LOREN JORGENSEN, CHRIS MILLER, TYLER NELSON

DESERET MAGAZINE, VOLUME 3, ISSUE 28, ISSN PP325, IS PUBLISHED 10 TIMES A YEAR BY DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO., WITH DOUBLE ISSUES IN JAN/FEB AND JULY/AUGUST. SUBSCRIPTIONS ARE $29 A YEAR. VISIT DESERET.COM/SUBSCRIBE.

PUBLISHER BURKE OLSEN

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER DAVID STEINBACH

VICE PRESIDENT MARKETING DANIEL FRANCISCO

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT SALES TRENT EYRE

VICE PRESIDENT SALES SALLY STEED

PRODUCTION MANAGER MEGAN DONIO

OPERATIONS MANAGER

BRITTANY M C CREADY

DIRECTOR OF CIRCULATION SYLVIA HANSEN

THE DESERET NEWS’ PRINCIPAL OFFICE IS 55 N. 300 WEST, STE 400, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH. COPYRIGHT 2023, DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA.

DESERET

PROPOSED AS A STATE IN 1849, DESERET SPANNED FROM THE SIERRAS IN CALIFORNIA TO THE ROCKIES IN COLORADO, AND FROM THE BORDER OF MEXICO NORTH TO OREGON, IDAHO AND WYOMING. INFORMED BY OUR HERITAGE AND VALUES, DESERET MAGAZINE COVERS THE PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF THAT TERRITORY AND ITS INTERSECTION WITH THE BROADER WORLD.

In Ecuador’s rainforests, a 2,000-year-old unwritten language is connecting cultures. By learning Quichua from the speakers who keep it alive, Brigham Young University students see the world in a new light and strengthen bonds that we have with each other.

Learning by study, by faith, and by experience, we strive to be among the exceptional universities in the world and an essential university for the world.

OUR READERS RESPOND

Our JULY/AUGUST annual Constitution issue featured a collection of essays about ongoing threats to the ideals in the nation’s founding document. Deseret Magazine Executive Editor Hal Boyd hosted a conversation between four leaders in the legal, religious, academic and media arenas (including Robert P. George and Coleman Hughes) about challenges to the ideal of pluralism (“E pluribus disunion”). “On one level, this article is somewhat amusing. When you peel away the layers of race, language, culture, history, religion, we’re much more alike than we are different. People get fixated on the superficial and lose out on the opportunity to really learn,” reader Mark Oberg observed. And reader Mickey Roach questioned, “Is there no longer room for the concept of a singular truth and light to which most people can gravitate to? If not, perhaps we are unalterably doomed to going off in all the various directions discussed.” Notre Dame law professor Stephanie Barclay wrote about a conflict over protecting the sacred lands of Oak Flat in Arizona from copper mining to show how understanding the beliefs of others can heal cultural rifts (“A shared commitment to freedom”). Reader Michael Cleveland reflected that both sides of the Oak Flat dispute should be respected as sacred. “The earth is for the benefit and creativity of mankind. There is no reason why the ‘Sunrise Ceremony’ can’t be preserved while using the God-given benefits of our world. It’s a matter of communication, sharing and using common sense.” John Yoo, a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, explored how calls to remodel the Constitution could spell its doom (“The Constitution in Crisis”). Reader Mark McPherson agreed: “I believe our goal should be not to trash the Constitution but to follow it.” Reader John Mill added, “America is even more of an idea than it is a geographical entity. Once people shared a common set of basic principles — and even when they disagreed about their application, they agreed on the ideals. I am not sure that exists anymore.” Two constitutional scholars, William B. Allen and his daughter Danielle Allen, a professor at Harvard, discussed the promise of the Declaration of Independence (“Can the American experiment survive?”). Reader Tyler Boulter commented, “Most things can survive if they’re willing to adapt to new environments. Those that can quickly adapt can even thrive. Trying to keep the components of the experiment static are errands of fools.” Ethan Bauer reported on CNN’s struggle to rebrand itself as a medium for impartial news, and it included the termination of the network’s CEO Chris Licht, which happened just prior to press time (“Journey to the Center of the News”). On X, the platform previously known as Twitter, Rich Shumate, a journalism professor and a former CNN editor and senior writer, praised the piece as “nice background on the #ChrisLitch era at CNN.’” Reader Kevin Labrum added, “It’s a refreshing breath of fresh air to hear that a news organization is committed to unbiased, fact driven, middle-of-the-road news reporting.”

“It’s a refreshing breath of fresh air to hear that a news organization is committed to unbiased, fact driven, middleof-the-road news reporting.”

RIDGELINE #1

SECEDA RIDGE ITALIAN DOLOMITES

PHOTOGRAPHY BY PAUL ADAMS

PRESENTED BY

Join us at Utah Business Forward, the premier conference designed exclusively for executives seeking practical insights and actionable strategies to propel their businesses forward. Experts from Utah’s business community will present in five distinct tracks covering:

• Entrepreneurship

• International Business

• Marketing

• People & Culture

• Strategy

These highly practical sessions include guides and checklists you can execute as soon as you return to the office!and many more!

FEATURING:

• Brandon Fugal, Colliers International

• Gail Miller, The Larry H. Miller Company

• Michelda George, Versatile Image

• Nate Randle, Gabb Wireless

• Shawn Nelson, Lovesac

• Sara Jones, InclusionPro

• and many more!

November 16, 2023 at the Grand America

FULL-DAY TICKETS FROM $349

AM I A MACHINE?

HOW ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE TESTS OUR HUMANITY

BY JOHN DURHAM PETERS

Modern thought begins in doubt. René Descartes decided to doubt everything, even his own existence, before he hit bedrock: If doubting is going on, there must be a doubter. So there is something real, i.e. the doubter. I think, therefore I am. Boom! He had found a sure foundation. And build upon it he did. He was a mathematical genius who anticipated most STEM fields today. Descartes is a symbolic launch-point for modern science and technology, a forerunner of the digital age.

Less well known is that Descartes also doubted people were actually human. Looking out his Amsterdam window at passersby in their hats and coats, he wondered if they might just be cleverly constructed automata. He lived at the dawn of a mechanical age. Clockwork and lenses were cutting-edge technologies. Automata could look uncannily alive. Good ones could move, talk and soon even seemingly eat or play chess. Lenses revealed impossible new sights beyond the reach of the unaided eye, the craters on the moon and the flapping tails of spermatozoa. Telescopes and microscopes breached bounds of sight and knowledge that fenced in all previous mortals.

For four centuries since, we’ve been worried. What if the machines, with their obviously superior capacities, took over? How can we defend what is uniquely human from their threat? Do our devices pass divinely given limits and threaten our humanity? Previous generations worried about Frankenstein, robots and assembly lines; today we worry about AI and the large language models that power ChatGPT. It’s a legitimate question. But maybe it’s also the wrong one.

At least, we often go about trying to answer it the wrong way. Ridley Scott’s dark 1982 sci-fi film “Blade Runner” portrays a drizzly neon-lit Los Angeles in an indefinite cyberfuture where renegade “replicants” mingle undetected with the human population. These

are artificial humanoids whose engineered identity can be revealed only by complicated tests. Some of them even think they are human. A former cop, Rick Deckard, played by Harrison Ford, is hired to hunt them down and “retire” (i.e. kill) them. Throughout, the film drops subtle hints, however, that this bounty hunter, too, might be a replicant. He’s named Deckard: Get it? (Descartes!) The question the film raises is not just whether the machines will take over but a deeper one: Am I a machine, too? What would it take for me to be human?

Artificial intelligence, no doubt, gives reasons to worry. The First Industrial Revolution, powered by steam, replaced physical labor, to some degree, by machines. Goodbye shovel and scythe, hello backhoe and combine. The Second Industrial Revolution, powered by electricity, replaced mental labor, to some degree, with automation. Goodbye telephone operator and reference librarian, hello automated switchboard and Google. Technological change has never been smooth: Workers always have strong opinions when made redundant. The recent Hollywood writers strike, for instance, is partly about guaranteeing a place for human talent when computer-generated scripts (and potentially actors, as well) are cheap and easy.

But let’s ask the deeper question: Does AI threaten what it means to be human? The annals of thought are littered with fallen defenses of what is uniquely human. Reasoning? Back-and-forth conversation? Empathy? All have wobbled. Ironically enough, we are regularly quizzed online whether we are human. We have to pick out the bicyclists, fire hydrants or crosswalks from an array of photos and then check a box attesting “I am not a robot.” Such CAPTCHA tests fend off spam and bots, while also mining valuable data for self-driving car developers. Declaring you are not a robot is an online open sesame!

But being a human is much harder than checking a box. Descartes stared out his window at the passing crowds and wondered if they were human beings. We stare at our screens and might sometimes have the same thought. We appear as avatars or “profiles,” a word once used mostly for criminals. Online we are all “replicants,” indistinguishable between android and human. In cyberspace, we are creatures of pixel and type. Maybe this is one reason the online world breeds so many bounty hunters out for the kill.

Will humans be replaced? This question assumes too much — that we are already human. A quick survey of online behavior will suggest: Perhaps not. Humanity is not what we have; it’s what we need. A frequently administered test of our humanity would show us sometimes mechanical and lacking in empathy! (How we act online and off may be precisely such a test.) Science fiction is full of humanlike androids who yearn to be human. In this they are actually very much like us: To be human is to strive to transcend what we already are. Smart machines do not unfurl unprecedented challenges; they remind us of the oldest test of all, how to be humane.

JOHN DURHAM PETERS IS THE MARÍA ROSA MENOCAL PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH AND OF FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES AT YALE UNIVERSITY.

WHAT IS WOKE?

HOW A BLACK COLLOQUIALISM BECAME A CONSERVATIVE BYWORD

Gov. Ron DeSantis calls his state the place where “woke goes to die.” Fellow 2024 Republican presidential hopeful, Vivek Ramaswamy, wrote an entire book denouncing so-called “Woke, Inc.” And according to a national poll conducted by HarrisX for the Deseret News, being labeled “woke,” will get you less support among voters. Nearly half say they’re less likely to support a “woke” candidate, while 24 percent say the opposite. In Republican circles, being labeled “woke” is almost certainly a political pox. When Time magazine dubbed Utah’s Spencer Cox “The Red-State Governor Who’s Not Afraid to Be ‘Woke’,”: he denounced the headline and said, “Being kind and trying to bring people together is very different than being ‘woke.’” But what is “woke”? And why are so many Republicans talking about it in the run up to the 2024 presidential election? Here’s the breakdown.

DEFINED

The term woke has its origins in Black vernacular — a shortened version of woken — the past tense of wake. The term suggests an awareness — an awakening — regarding issues related to race and social justice. In the 2010s, the term’s usage expanded to include an array of progressive causes and ideologies. Soon, as one British journalist put it, the term became shorthand for an “overrighteous liberalism.”

# STAYWOKE

The first known use of “woke” was a spoken warning from Huddie Ledbetter, the blues musician known as Lead Belly, appended to this 1938 song about nine Black youths falsely accused of rape in rural Alabama. The 1931 case would become a spark for the civil rights movement, and each defendant was later exonerated or pardoned. But Ledbetter offered pragmatic advice to Black travelers in a

region that could be hostile. “Best stay woke. Keep their eyes open.” In 2014, the hashtag #Staywoke coalesced as a watchword against police brutality as

protesters used it along with another hashtag that launched a movement: #blacklivesmatter.

BLOWBACK

On the right, and even within pockets of the left, some soured on certain progressive reforms as crime and lawlessness increased in places like San Francisco and Seattle. Others grew tired of big brands leveraging serious social

issues to market everything from sneakers to tech gadgets. Even “Saturday Night Live” mocked the commercialization with a sketch on “Levi’s Wokes” — unappealing jeans described as “Sizeless, style neutral, gender non-conforming denim for a generation that despises labels. Levi’s heard that if you’re not woke, it’s bad. So we made these.”

HUDDIE LEDBETTER

I LOVE NAPS

During the 2017 Women’s March, a nationwide demonstration that drew more than 1 million people, an Asian American toddler in North Carolina wore a hand-drawn sign: “I ♥ naps but I STAY WOKE.” A photo went viral, shared online by celebrities like Ariana Grande. Within two weeks, the boy’s father applied for a trademark to use the phrase on hats, pants, socks, sweaters and T-shirts. His application was abandoned, but the slogan took off among largely white mainstream liberals.

“The woke movement was supposed to be about people of color not getting opportunities, the at-bats that they deserved, finally making that happen. And it was about that, for about eight seconds. And then somehow white women swung their Gucci-booted feet over the fence of oppression and stuck themselves at the front of the line.” — Bill Burr, a notoriously abrasive comedian, on “Saturday Night Live” in October 2020

“THE IDEA OF PURITY AND YOU’RE NEVER COMPROMISED AND ALWAYS POLITICALLY WOKE — YOU SHOULD GET OVER THAT QUICKLY. THE WORLD IS MESSY. THERE ARE AMBIGUITIES. IF I TWEET ABOUT HOW YOU DIDN’T DO SOMETHING RIGHT, I CAN SIT BACK AND FEEL PRETTY GOOD ABOUT MYSELF, BECAUSE MAN, DO YOU SEE HOW WOKE I WAS? I CALLED YOU OUT. THAT’S NOT BRINGING ABOUT CHANGE. IF ALL YOU’RE DOING IS CASTING STONES, YOU’RE PROBABLY NOT GOING TO GET THAT FAR.”

Former President Barack Obama

WOKE CAPITAL

Coined by New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, this term describes brands that cast themselves as forces for social change on issues like racial justice or transgender rights, wrapping candy in rainbows or disassociating from troubled entities like the NRA.

Others called it “woke-washing.” But the concept has also evolved into investment frameworks that consider how a company handles environmental, social and governance issues, or ESG (see The Notorious ESG on p. 28).

WOKE-LASH

As Douthat predicted, conservatives often feel besieged — by woke beer and M&Ms, but also call-outs by “woke mobs” on X (formerly Twitter). That might explain Fox News’ obsessive pushback, compiled in a recent montage by news watchdog Media Matters. Those labeled “woke” include:

AMAZON

BANKS

BOY SCOUTS

CHICK-FIL-A

CIA

COVID-19

DATING APPS

DELTA AIRLINES

DISNEY

EMOJIS

FEDERAL RESERVE

GOODYEAR TIRES

LEGO THE MILITARY

MY LITTLE PONY

MICROSOFT

NASA

NIKE

REAL ESTATE

WEBSITES

WALMART

WOMEN’S HISTORY

MONTH

THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION

YELP

WORD POLICE?

40% INSULT

50% INFORMED

39% TOO P.C.

Today, 40 percent of Americans see “woke” as an insult. About a third take it as a compliment, more among adults under 34. More than half of that cohort define woke as “informed, educated on and aware of social injustices” while 39 percent believe it means “overly politically correct and policing others’ words.” Seniors are more likely to say they don’t know what it means.

FLORIDA GOV. RON DESANTIS EMBRACES AN ANTI-WOKE MESSAGE AS PART OF HIS CAMPAIGN FOR THE GOP PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION, SAYING HIS STATE IS WHERE “WOKE GOES TO DIE.”

MEASURED JUSTICE

THE DEBATE OVER SUPREME COURT REFORM

EXIT

THE SUPREME COURT is having a rough go. In theory, justices on the nation’s highest tribunal are shielded from the political fray, so they can interpret the law without regard to the currents of a given moment. But today they find themselves at the center of Beltway maneuvers and troubled times, from politically charged confirmation hearings to the premature leak of its decision on abortion and ethical questions about unreported gifts. The court’s approval rating has hit an all-time low of just 40 percent, according to Gallup. Some have called for reform, largely focused on term limits or expanding the court. But does the court need fixing?

CHANGING WITH THE TIMES IF IT’S NOT BROKEN, DON’T FIX IT

The Supreme Court is a global outlier, with a politicized nomination procedure, lifetime terms and uncommon power. That reach is a problem, argues Jay Willis, editor-in-chief of “Balls & Strikes,” a progressive news site focused on the courts. “It has an insane amount of power relative to the Supreme Courts of almost every other country,” he told Foreign Policy last year. “It is one of the few high courts that has the unilateral authority to look at a piece of legislation passed by two independent, politically accountable branches of government and be like, ‘Nah, not allowed.’”

Judicial review has been well established since 1803, but some argue that Congress can limit the high court’s jurisdiction. This was explored in the final report from the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court, issued in 2021, along with moves like court expansion and term limits. But without a constitutional amendment, the court itself could simply strike down any legislative reforms. “If adopted by statute,” writes Rosalind Dixon, law professor at the University of New South Wales in Australia, “it would come before the Supreme Court for review — and the court might well reject the argument.”

While there is historical precedent for court expansion — President Joe Biden opposes the idea — term limits may be the most viable path for reform. In 2021, 17 House Democrats co-sponsored a bill that would establish 18-year terms for Supreme Court justices, who would be appointed every two years. Senior justices could continue to work but would no longer decide cases. The bill would also waive the Senate’s advice and consent authority if the body does not act on a presidential appointment within 120 days.

Reform could have a surprising ally, if Chief Justice John Roberts stands by a memo he sent to the White House in 1983. “Setting a term of, say, 15 years would ensure that federal judges would not lose all touch with reality through decades of ivory tower existence. It would also provide a more regular and greater degree of turnover among the judges. Both developments would, in my view, be healthy ones. Denying reappointment would eliminate any significant threat to judicial independence.”

Perhaps the Supreme Court is doing precisely what it was meant to do. Each justice in the conservative majority was nominated by a Republican president and confirmed by the Senate when each seat became vacant. The court’s decision overruling Roe v. Wade reflected the nation’s political divisions over the issue of abortion. The third branch of government remains separate but equal. Even the basis for judicial review is found in Article 3 of the Constitution.

While Congress has the power to change the number of justices, it hasn’t done so since 1869, settling at nine following a period of upheaval. The last president who sought to expand the court was Franklin D. Roosevelt, which is largely seen as an effort to secure judicial imprimatur for aggressive economic programs in the New Deal. Congress rejected that legislation, which still resonates as a hand-slap to executive overreach. That may explain Biden’s reluctance to cooperate with the more activist wing of the Democratic party.

Term limits are also not a new idea. But the Founding Fathers chose to grant lifetime seats, in part to protect judges from being swayed by financial need. As Alexander Hamilton wrote in The Federalist Papers, No. 79, “Nothing can contribute more to the independence of the judges than a fixed provision for their support.” Article 3 provides that judges “shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour.” So they can be removed through impeachment, just like a president. That last happened in 1804. In practice, limiting turnover also helps to make the court more consistent over time.

Some fear that term limits would have the opposite of the desired effect. Writing for The Washington Post, Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III of the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals contends that term limits would only exacerbate the court’s perceived faults. “They will make the institution appear more, not less, political in the eyes of the public. Confirmation battles will become more numerous but no less feverish, because 18 years is long enough to inflame partisan confirmation passions, especially if the court is closely divided.”

MATERNAL INSTINCTS

BECOMING A MOTHER POST 40, AND THE ANXIETY OF KNOWING TOO MUCH

BY BRIDGET PHETASY

Ibecame a first-time geriatric mommy at age 42. If you laughed at the term “geriatric,” so did I, but it is commonly applied to any woman over 35 who gets pregnant. Although the medical world is moving away from using geriatric, with its connotations of blue hair and walkers — the new PC term is “Advanced Maternal Age” and isn’t much better, in my opinion. I prefer something cool, like Vintage Baby Maker.

New parents, old and young, are bombarded with a torrent of information and options from the minute they find out they are expecting. For me, it first came from the doctors in the form of dozens of optional, nerve-racking genetic tests and scans that may or may not be necessary (or reliable).

As I started asking friends and family for advice, everyone offered a different opinion. Once the almighty algorithm discovered I was pregnant, it chimed in, too — Instagram flooding my feed with relatable preggo content. Some of it was useful. Some of it preyed on my worst fears. All of it was conflicting.

I’m told parenting wasn’t always so fraught with anxiety and filled with often completely opposing child-rearing options.

This is the product of the mediated, consumerist world in which we now live. (Don’t get me started on the baby registry — that’s another essay entirely.)

In his book “Mediated: How the Media Shapes Your World and the Way You Live in It,” author Thomas de Zengotita talks about observing kids with their bike helmets that

IMAGINE MY SURPRISE WHEN I FOUND OUT YOU SHOULD HAVE A BIRTH PLAN AND IT ENCOMPASSES A LOT MORE THAN WHAT I HAD IN MIND.

“could deflect a bazooka shell” and finds himself feeling nostalgic for the simpler times when kids were free range. “No one ever heard of a bike helmet, and injuries of all kinds were the assumed risks of childhood,” de Zengotita writes.

However, he notes that if he were a parent of a young child today, what he would do is completely different. “Now that I know

about bike helmets, now that they are an option, it would be downright irresponsible not to strap one on little Justin’s head,” he explains. “Justin’s Helmet Principle” is what he labels the process by which “you end up opting for these options because, on balance, it’s better than not opting for them.”

Motherhood starts when the child is in utero and some of the choices I had to make felt existential: Do we find out the sex or decline? Should we get the genetic tests they recommend (especially for us “geriatrics”) or let the chips fall where they may? Traditional OB-GYN or go the midwife/doula route? Maybe some combination of all three? Home birth? Hospital birth? Pool in the woods under a full moon?

Imagine my surprise when I found out you should have a birth plan and it encompasses a lot more than what I had in mind. My bar was pretty low: Mom and baby live through the experience of childbirth. Lots of women, however, set their expectations very high. They want a magical experience with a photographer and a playlist and twinkly lights because that’s what their favorite YouTube influencer told them they deserve

NOTHING IS MORE FRAUGHT WITH EMOTION, AIRS OF SUPERIORITY, AND CERTAINTY ABOUT THE WAY YOU SHOULD BE DOING THINGS THAN HOW AND WHERE YOUR CHILD IS SLEEPING.

— baby crowning, mother pushing with a full face of makeup and perfectly done hair.

There was more. Did I want interventions? Fetal monitoring? Drugs? When the baby comes do you want skin-to-skin immediately? The hep B shot? The eye drops? Should I bank the cord blood? Stem cells seem important, right? What if she needs them in the future and I could have saved her life, but I didn’t want to pay a storage fee to keep them on ice? How guilty will I feel?

Worst of all, what if, in the near future, they have the technology to let mere mortals dodge death — if only I had banked the cord blood. I imagined my then unborn daughter, a teenager, shaming me for being cheap. “All my friends are gonna live forever, Mom.”

For those of you wondering — I had a scheduled C-section because of my vintage age; we got the eye drops; we delayed the hep B shot; I didn’t bank the cord blood (sorry, honey, eternal life on Earth seems exhausting).

It never ends, either. Once our daughter was born, we discovered even more options to navigate.

Cribs versus Montessori floor beds. No screens for the first two years, even though the grandparents are scattered all over the country and the only way your child has a relationship with them is FaceTime. The only thing my child wants is my phone. She screams when you take the black mirror away or try to hide it from her. I’d already failed before she turned one.

My husband and I learned pretty quickly that the gold standard by which all your parenting skills shall be judged is sleep. The first question veteran parents asked us when we started taking our daughter for walks around the neighborhood was, “Is she sleeping yet?”

Nothing is more fraught with emotion, airs of superiority, and certainty about the way you should be doing things than how and where your child is sleeping. Everyone’s method is the best because it worked for them — and you will hear from everyone.

Things change quickly in the science of sleep. When I was an infant, the best

practice was to put babies to sleep on their stomachs. Even in the 14 years since my sister had her last child, she marvels at how different everything is for her siblings and our kids.

“I feel like a grandmother,” she said to me recently. “They can’t have blankets! All my kids had blankets and bumpers and cozy cribs.” Now the prevailing wisdom is swaddled kid (or kid in a sleep sack) in an empty crib or bassinet.

Co-sleeping is also in. If you mention cry it out, half the people will tell you they did it, the other half will tell you you’re psychologically damaging your child. Dr. Gabor Maté has spoken out against the practice of cry it out and said, “Encoded in her cortex is an implicit sense of a noncaring universe.” Seems dramatic. I don’t want her to think the universe doesn’t care about her (even if I can’t prove that it does) and I don’t want her to believe no one is coming (even if that’s kind of true, too). I also don’t want to coddle her every whim and create a monster with anxious attachment. If I don’t let my daughter cry it out, will she be gluing herself to a work of art in 20 years?

Mistakes will be made. So much of parenting is winging it, trying to figure out what works best for the child within the entire family system in the moment. What you’d like to do and what you can realistically do are often not compatible. What you want to do and what is best for the child are also often not compatible. Being stern but fair seems like what is required to be a good parent who raises children with boundaries and manners and aren’t spoiled rotten, running the house.

The list of decisions goes on and on, it never ends, but especially as a first-time parent, the stakes feel so high. It’s enough to make you completely neurotic, if you let it.

Navigating these options is Justin’s Helmet Principle in action — but it’s not always black or white. How do you make sense of all the new information and balance it with the prevailing wisdom? How do you know if you’re making the right decision?

You don’t. But that’s parenthood.

THE NOTORIOUS ESG

WHAT IS ‘ESG’ INVESTING, AND HOW DID IT ADVANCE TO THE FRONT LINES OF THE CULTURE WARS?

BY ETHAN BAUER

The senator first heard murmurs in early 2022 from concerned citizens and industry experts alike. By fall, the murmurs had become conversations with representatives of the banking industry, members of both houses of Utah’s legislature. These stakeholders formed a working group to tackle “ESG” standards that are turning corporate America “woke.” GOP state Sen. Chris Wilson, whose district includes parts of Cache and Rich counties in northern Utah, came out of the working group determined to act on ESG when the legislative session convened in 2023.

If you find yourself confused at this point about what ESG is, you’re not alone; most Americans aren’t familiar with the term — perhaps by design. Consider a rule taught in journalism schools called the “alphabet soup” principle: Unless an acronym is universally recognized, like FBI or NAFTA, avoid using it out of respect for your readers, many of whom won’t know what it means.

Politicians have, at almost every possible opportunity, ignored that wisdom when it comes to ESG, which stands for environmental, social and governance-conscious investing, but has become a largely meaningless buzzword for Democrats who’ve used it as a crutch after failing to address many ESG-adjacent issues through policy,

as well as a bugaboo for conservatives. Even the people tasked with making laws regarding ESG often have a hard time defining what it is or what it does — a fact that does little to temper their enthusiasm either for or against it.

It’s become a particularly popular talking point on the right. Ben Lewis, a professor of strategy at Brigham Young University who has studied ESG for many years, first noticed its explosion into the mainstream political consciousness when brochures

IN SIMPLE TERMS, IT ARGUES THAT A COMPANY’S SINGULAR RESPONSIBILITY IS TO MAXIMIZE VALUE FOR ITS SHAREHOLDERS.

for a county-level candidate started showing up at his house with ramblings about how ESG was a Chinese Communist Party plot to infiltrate America. Republican presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy has also made criticism of ESG a cornerstone of his campaign (he’s currently polling at about 8.3 percent). But controversy over the concept is actually much older.

It arguably goes all the way back to a foundational economic principle introduced in the 1970s called the Friedman Doctrine. In simple terms, it argues that a company’s singular responsibility is to maximize value for its shareholders. That school of thinking inspired a school of pushback coined by World Economic Forum founder Klaus Schwab as “stakeholder capitalism,” which argues that companies have a responsibility to anyone their decisions impact; not just shareholders. The term ESG came around in 2004 in a United Nations report that recommended the integration of ESG issues in “asset management, securities brokerage services and associated research functions.”

“Part of ESG, in and of itself, is trying to make companies aware of those different stakeholders and pay attention to their issues, beyond just the financial stakeholders,” Lewis says.

The idea mostly simmered, unnoticed, until 2016. Then Donald Trump was elected president and addressing issues like climate change at a more individual, personalized level suddenly became appealing, argues former investment banker and well-documented ESG critic Tariq Fancy. “If you’re a progressive, and you want to do something about climate change, Trump gets elected and makes it fairly clear he

doesn’t plan to do anything about it,” he explains. Four years, those progressives argued, was far too long to do nothing about climate change. So many of them started asking if they could invest their 401(k)s in more climate-conscious ways, or buy more

climate-conscious products. “That’s what gave (ESG) its rise,” Fancy says.

It exploded even more late last year, after the Biden administration directed the Department of Labor to allow retirement plan fiduciaries to consider ESG factors when

making investments. That rule went into effect in January and was challenged by the Republican-controlled House of Representatives, as well as Senate Republicans and two Democrats — Jon Tester of Montana and Joe Manchin of West Virginia — who

in March sent a resolution to Joe Biden’s desk calling for a reversal of the rule. Biden vetoed it, with both sides accusing each other of the exact same financial crime, almost verbatim. “The Biden administration’s recent ESG rule would pose further risk to these retirement funds by forcing fiduciaries to use Americans’ hard-earned money to advance social causes rather than investing to get the best returns,” Sen. Mitt Romney said in February. “The legislation passed by the Congress would put at risk the retirement savings of individuals across the country,” Biden said about a month and a half later, following his veto.

A group of 25 states, including Utah, have since signed onto a lawsuit challenging the rule in court. “Permitting asset managers to direct hard-working Americans’ money to ESG investments puts trillions of dollars of retirement savings at risk in exchange for someone else’s political agenda,” Utah Attorney General Sean Reyes said in a press release announcing the lawsuit. The effort is being spearheaded by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, whose press release announcing his opposition calls ESG a “direct threat to the American economy, individual economic freedom, and our way of life.” And Wilson, during Utah’s 2023 legislative session, sponsored two bills (both became law) targeting ESG investing in the state — a common refrain in Republican-controlled legislatures across the country. In March, he took to the pages of Cache Valley’s Herald Journal to defend that legislation, arguing that “the Biden administration issued a rule that would place millions of Americans’ retirement funds at risk by allowing retirement plan fiduciaries to consider ESG factors when selecting investments and exercising shareholder rights.” But he also quoted Romney, who said the rule would be “forcing” them to do so. “I don’t have a problem if people are allowed the freedom to invest in ESG funds. But I do have a problem when … ESG has to be used in all investments,” Wilson says. “Biden’s (rule), from what I understand, was that they needed to use ESG standards.”

That understanding, it turns out, is not

entirely correct. Allowed is a better word than forced. “As much as I admire Senator Romney,” says Lewis, who has voted for Romney three times, “I believe he is mischaracterizing the intent of the ruling when he states that the (Department of Labor) ruling would ‘force’ fiduciaries to take ESG factors into account.” All the rule did was clarify that fiduciaries were allowed to consider ESG factors as part of their investing strategies, ensuring that doing so would not result in lawsuits alleging that the investors had failed to seek maximum returns. Lynn Rees, a professor of accountancy at Utah State, argues that despite having no personal affinity for ESG as an investment strategy, the DeSantis-led effort to overturn the Biden administration’s rule

“I DON’T HAVE A PROBLEM IF PEOPLE ARE ALLOWED THE FREEDOM TO INVEST IN ESG FUNDS. BUT I DO HAVE A PROBLEM WHEN … ESG HAS TO BE USED IN ALL INVESTMENTS.”

is ironic in that it claims to be pro-freedom while really accomplishing the opposite. “I do make my own investing decisions, and at no time have I really considered ESG factors,” he says. But nevertheless, he adds, “I don’t think it’s the government’s place to tell capital managers what they should and should not consider (investing in).” At the very least, he says, you could make a reasonable argument that considering ESG is good for profits (research on this has resulted in mixed findings), and fiduciaries should be allowed that option. And if investors are unhappy with those decisions, they’re welcome to invest elsewhere.

Fancy, who worked at investing giant BlackRock before quitting to become something of an anti-ESG whistleblower, has a different take on the recent political

blame-slinging. He left BlackRock because he came to believe that ESG standards were, essentially, nonsense. They accomplished absolutely nothing for climate (and other) goals, ultimately allowing companies to use faulty, nonstandardized metrics and subversive investing strategies to portray themselves as committed to social responsibility while still doing exactly what they’ve always done and will continue to do: Maximize profits. “The political right is beating (Democrats) up,” he says, “by pretending the greenwashing is real.”

Democrats, he says, are passing the buck to private companies to make a difference on climate change and other progressive causes when their policies aimed at doing so haven’t become law. They’re looking for help wherever they can get it, he contends, but investors just aren’t wired to prioritize causes in the way a government can. Maybe they can move some money around to more ESG-aligned investments, but ultimately, they will never do so unless they think such a decision will maximize profits. Insofar as investors use ESG, it’s already in the service of maximizing financial return.

Fancy also argues that Romney and Wilson aren’t 100 percent wrong about Biden’s rule “forcing” companies to consider ESG Investment firms like BlackRock can indeed exert a huge amount of pressure on companies in which they own many shares of stock by pressuring them into making certain social decisions, like increasing diversity and inclusion. The rule still does not make them do so, but it does allow investment firms to do so more freely. Which is why Wilson argues such policies are still bad for Utah. “To try and force companies to avoid or boycott a company, just because they’re in timber or mining or agriculture or firearms, to me is discrimination,” he says, “and it’s wrong.”

But at a time when most Americans still don’t even know what ESG is, and their political leaders are often further obfuscating their understanding, Fancy has a name for the politics around the current debate over ESG. “I call this the stupid debate,” he says. “There’s no other word for it.”

A PLACE TO GROW

IN LONGMONT, COLORADO, A HOUSING PROGRAM FOR LOW-INCOME AGRICULTURAL WORKERS REVEALS AN INDUSTRY IN FLUX

BY ETHAN BAUER

Inside Casa de la Esperanza’s kitchen, a metal table overflows with “fixins”: bottles of chamoy, Tajín and squeezable butter; a drum of mayonnaise and a bag of cotija cheese; and a bowl of freshly boiled, yellow corn cobs. Kids, teenagers and adults alike carry their elotes through the hallways, holding them like oversized lollipops. The savory smell of the spices and butter collides with the sweetness of strawberry syrup bubbling atop the shared stove, destined for shaved ice. Everyone gathers round and takes part — the perks of a food-sharing program in action, and just one of the benefits for families living here.

When Casa de la Esperanza opened in 1993 in Longmont, Colorado, it represented an innovative solution to a problem that had long plagued agricultural communities across the West. Immigrants from Mexico and Central America formed the backbone of America’s agriculture industry (and today, still making up 73 percent of the nation’s agricultural workforce). But given the industry’s often-low wages, workers couldn’t afford rent in many areas near work. Casa de la Esperanza, which translates to House of Hope, opened in response — and quickly filled up.

Sixteen families live here now, and rent starts at $635 per month. To be eligible, families need to have at least three members, fall below a certain income threshold

(families of four, for example, need to make less than $90,000), and the head of the household needs to be a documented agricultural worker. “It’s purposeful,” the center’s program coordinator, Vanessa Arritola, says. “You’re helping people.” And that’s a big deal at a time when decrepit housing situations endure for many low-income agricultural workers, from New York to Florida to California. And yet, today Casa de la Esperanza is only about half full.

Longmont’s agriculture industry is fading, too. It’s been chewed up — like most

“ONE OF THE BRAGGING RIGHTS OF AGRICULTURE IS THAT IT GOT MORE EFFICIENT. WE NEED A LITTLE LESS LABOR TO PRODUCE THE SAME AMOUNT WE WERE PRODUCING HISTORICALLY.”

urban-adjacent farmland across the country — by suburban sprawl. And the nation’s agricultural workforce is changing, too. It’s smaller, older and more temporary than it once was, with seasonal workers increasingly filling the void of the industry’s constant labor challenges. Now, Casa de la Esperanza’s future is in question. Its fate,

to some extent, mirrors the old ways of agriculture in the Mountain West.

ONCE ONE OF the largest farming communities in Colorado, Longmont is now enveloped by suburban sprawl. Casa de la Esperanza straddles a very literal line of this force; sitting between a self-storage facility and a field. “As has happened in a lot of fast-growing urban areas, housing can always offer a better price point for land than farming,” says Dawn Thilmany, a professor of agricultural economics at Colorado State University. “So we’re gradually seeing more and more of that farmland transition into homes.”

Today, the town’s population stands at over 100,000. More people means more neighborhoods and shopping centers and parks. Urban sprawl has gobbled up rural land across the nation for decades, and among Colorado’s 64 counties, Longmont’s home of Boulder County ranks in the top 10 statewide for open land lost to sprawl between 1982 and 2017. But sprawl is only part of the story. Alongside the changing landscape is a changing workforce. Back in 1950, the U.S. had nearly 10 million farm workers; today, it’s down to just over three million — even as yields trend upward. Boulder County produced $27.8 million worth of crops back in 1997; the most recent USDA data, from 2017, shows that

number has swelled to $38.3 million. Even accounting for inflation, Boulder County’s crops are worth about as much now as they were nearly 30 years ago. So even with less land, crops have maintained their value. However, farming doesn’t require the same number of workers it once did.

“One of the bragging rights of (agriculture) is that it got more efficient,” Thilmany says. “We need a little less labor to produce the same amount we were producing historically.” People were replaced with robotic harvesting, self-driving tractors and “automated farming,” which uses a combination of drones, computers and automatic watering and seeding devices. People got replaced — and the people who do remain are increasingly transient.

The H-2A visa program allows foreign workers to reside in the U.S. temporarily for seasonal jobs, largely in agriculture. “There’s a very prescribed amount of weeks that they’re allowed to work (in a particular place), and then they move to their next job in another state,” Thilmany says. “Those people would never want to sign leases with or live in a housing situation like (Casa de la Esperanza) because they know they’re going to be leaving.” The H-2A visa program has grown exponentially over the last decade, with fewer than 100,000 visas issued in 2013 compared to 300,000 last year.

Boulder County itself doesn’t have many registered H-2A visa holders, according to the most recent data from the American Immigration Council, but neighboring Adams and Weld counties rank second and third in the state, respectively. Many of the agriculture jobs adjacent to Longmont are going to workers who will only be there for a short time, and therefore wouldn’t have interest in a long-term lease in affordable housing programs. It’s not often that in a time of housing crisis and extreme inflation that affordable housing would be at risk simply because tenants are too hard to come by, but that’s the case for Casa de la Esperanza.

ROOMS STAND EMPTY. Fewer children run through the halls. Maybe, Arritola has

begun to think, the program needs to change with the times.

Thanks to $350,000 of recently acquired funding via the American Rescue Plan, the county plans to move away from traditional USDA loans to open Casa de la Esperanza up to all low-income applicants, not just agricultural workers. Which, Arritola admits, would be strange at first. The agricultural adjacency of the people who live here has helped bond the community and informed its culture. Nevertheless, “I want to see the units filled,” she says. “There’s such a huge housing need. And if that’s the last resort, then I’m all for it. … It’ll change a little bit of that dynamic, but we’re OK.” And maybe it doesn’t even need to change the dynamic all that much.

And Longmont has become too expensive for many of them. “The working poor are just falling right out of the safety net. There is no safety net for them,” she says. “Incomes are not matching what people need to sustain themselves and have a livable wage.”

“THE WORKING POOR ARE JUST FALLING RIGHT OUT OF THE SAFETY NET. THERE IS NO SAFETY NET.”

Per the most recent census data, about a quarter of Longmont’s population is Hispanic or Latino. As of 2020, about 11 percent of residents are also foreign-born, but that number has been dropping. Back in 2015, around 10 percent of residents were not born in the U.S., mirroring the average for communities across the United States. Longmont’s foreign population still ranks several percentage points higher than Colorado’s average, and it also beats out neighboring communities like Boulder and Greeley. That sizable population and its first-generation children may not be as keen on working in agriculture anymore, but they often still work low-income jobs, says Donna Lovato, executive director of a Longmont-based immigrant advocacy group called El Comité. Jobs in hotels and landscaping and restaurants, for example.

Lovato was already working in Longmont’s immigrant community 30 years ago, when Casa de la Esperanza was founded. But over time, she says, she’s seen the trends reflected in the statistics: the sprawl; the reduction of farming jobs; the new visa programs. And, more recently, the extreme housing cost increases that have afflicted many mountain towns across the West. “People used to come to Longmont from Boulder,” she says. “Now they’re leaving Longmont, too.” Casa de la Esperanza, she says, is well situated to address this issue. “I have heard they want to change it,” she says, “and if they focus on first-generation, low-income immigrants, I think that would be perfect.”

Before that happens, though, the program must make a final effort to bring in agricultural workers. Over the summer, local newspapers published stories about the vacancies. Boulder County also issued a press release, advertising the openings at Casa de la Esperanza. Places like Casa de la Esperanza exist because communities and their leaders have decided that certain jobs are so essential that they must be subsidized. When it was founded, it made sense to continue subsidizing the local agriculture industry. But even as far back as the 1970s, Richard Nixon’s secretary of agriculture told farmers to “get big or get out.” Headlines, politicians and studies have lamented the downfall of the small American family farm while bigger players continue to increase profit and product. Indeed, America’s agriculture industry writ large is humming right along, but if you define the industry by the way it used to be — with regional producers and local economies — you’d think that it’s now nonexistent. Instead, it’s simply moved on. Places like Longmont and Casa de la Esperanza will need to decide if it’s time to move on, too.

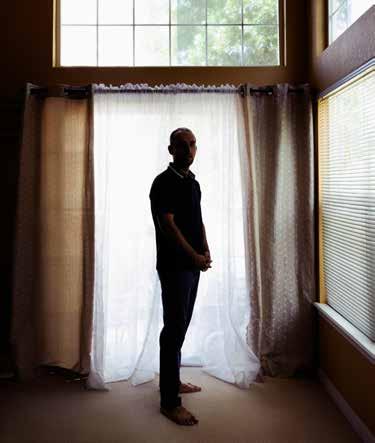

THE FINAL MISSION

DURING THE WITHDRAWAL FROM AFGHANISTAN , MOST LOCAL ALLIES WHO HAD SHOWN UNSHAKABLE LOYALTY TO U.S. TROOPS WERE LEFT TO FEND FOR THEMSELVES AMID A BLOODY TALIBAN TAKEOVER . THE BOND BETWEEN ONE SOLDIER AND HIS INTERPRETER WAS TOO STRONG FOR THAT | BY PAUL KIX | PHOTOGRAPHY BY STEPHANIE BASSOS |

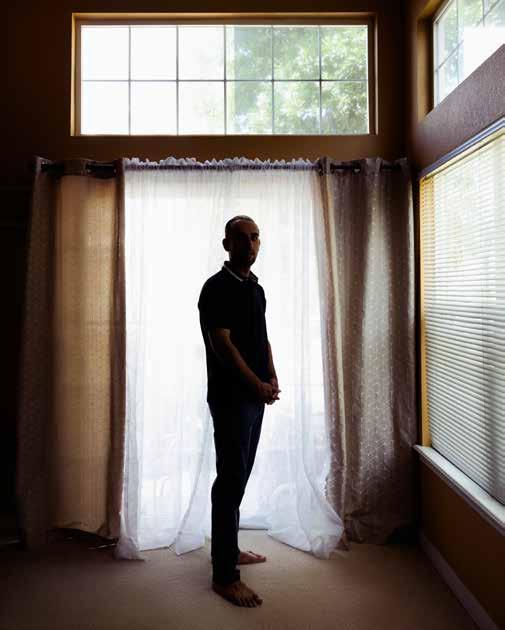

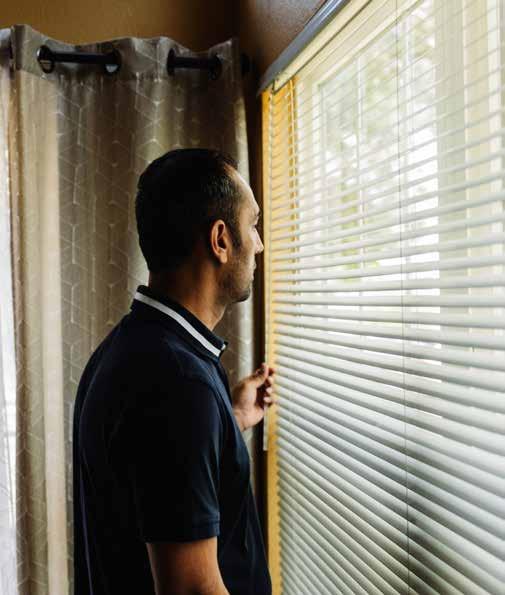

AHMAD KHALID SIDDIQI WAS AN INTERPRETER FOR U.S. TROOPS IN AFGHANISTAN AND LATER A CEO HELPING RESHAPE THE COUNTRY, UNTIL THE FALL OF KABUL IN 2021.

SCOTT HENKEL TRIES NOT TO FIXATE ON THE NEWS FROM AFGHANISTAN ,

like the story describing how the Taliban has taken Zabul, a southern province where he once built roads and schools and an almost-tactile camaraderie between the Army troops under his command and the Afghans his unit was meant to serve. The memories of 2006 and ’07 overlaid now against the reality of 2021, in the final chaotic weeks before the U.S.’s September 2021 deadline to withdraw all American military forces from Afghanistan — Henkel tells himself he’ll focus instead on his life stateside, here in suburban Denver, where he’s transitioning from one cybersecurity firm to another. He tells himself he’ll help guide his wife and two teenage kids through the complexities of the pandemic, everybody living and working on top of each other. Life itself tries to keep him occupied, and yet the Taliban pincering the rural outposts like the one where Henkel spent good portions of his young adulthood — his work gone, undone, just poof — also shows how life does not unfold in the manner we tell it to.

Because there, on the news, other provinces, poof. The Taliban overruns a prison housing Taliban militants in Kunduz. These jailed fighters, freed from their cells, join their Talib brethren on the streets and like that they rampage on.

Like that, Kandahar falls. Kandahar! The second-largest city in the nation. Just overwhelmed August 12, 2021, by the suddenly swarming Taliban.

Like that, Kabul is invaded. The capital, the last line of defense. Henkel sees it all over his Google News feed.

He puts his head in his hands. He has soldiered through life: the rail-thin high school football strong safety who surprised everyone with how hard he hit, keeping a ledger on Friday nights of the opponents he knocked out of games; the walk-on to the Colorado State track team who became a four-year letterman; the commissioned

officer who, after 9/11, endured inadequate training for the nation-building civil affairs units where Army brass expected leaders like Henkel to be both fighters and diplomats. Henkel and his men had somehow still carried out 400 missions beyond the wire. Because Scott Henkel soldiered through life.

But he can’t soldier through Kabul’s fall. He feels “complete hopelessness,” he’ll later say.

His wife Heidi sees it. Scott with his head in his hands, his shoulders drooped, his face like he’s seen a ghost, because he has: The return of the war. It haunts his cul-de-sac’d air-conditioned home, a mocking ghost. Why were you there? Why were any of you? What was the point of the last 20 years?

When Henkel talks, it’s through tears. One soldier from his tour is in Afghanistan now, less a soldier to Henkel than a brother. And as the Pentagon and State Department and Biden administration finger-point whose exit plan is to blame for the last few weeks’ disastrous collapse in Afghanistan — one hell of a way to end America’s longest war, with tens of thousands of Americans and hundreds of thousands of wartime allies looking for a way out of what can only be called a failed state — Scott Henkel thinks of this brother, and this brother alone, the one whose life has for 15 years been intertwined with his.

Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi.

The one he called Kevin.

The wing man. Henkel’s eyes and ears and often his mouth, and a soldier so fiercely loyal to a free Afghanistan he’s remained there even beyond the point it’s free. That tears at Henkel. There is no Scott Henkel without Kevin, not anymore, and any story he tells of his life means a commensurate one must be told of Kevin. He’ll say this to anyone who asks. But he can only say now, through tears, what he knows of their intertwined lives: The Taliban will track Kevin down. Henkel is sure of it. The Talibs will find Kevin, Scott tells Heidi Henkel, and they’ll force Kevin’s wife and daughters into

CAPT. SCOTT HENKEL WORKED CLOSELY WITH AHMAD KHALID SIDDIQI DURING HIS U.S. ARMY TOURS IN AFGHANISTAN.

sex slavery and probably kill Kevin’s son before his eyes and then execute Kevin, too.

“Kevin’s going to die,” Scott tells Heidi. He bawls some more.

Because what can he do from Denver to prevent it?

AHMAD KHALID SIDDIQI drives south through Kabul while cars, buses and people on foot flee in the opposite direction, north. Every face seems panicked. News has spread today, August 15, 2021, of the Taliban’s approach on the city through its southern outposts and of President Ashraf Ghani already abandoning Kabul and fleeing the country. Khalid doesn’t doubt these reports’ veracity but has business he must resolve today near the advancing Taliban.

So he fights the deluge of traffic heading the opposite direction — cars not even obeying one-way-street signs — and glances over at his 16-year-old brother, Omar, sitting nervously in the passenger seat.

It may seem reckless for his youngest brother, a minor no less, to accompany him, but to Khalid’s mind it’s shrewd. If Khalid’s captured, the Talibs will likely spare the

boy. Omar can then flee to the rest of Khalid’s family in northern Kabul and tell their parents and siblings and Khalid’s wife that Khalid has been killed.

At least that way they will know his fate.

Khalid drives his Toyota Corolla, “his low-profile car,” as he calls it, and not his Lexus. He’s also left his bodyguard back at his compound. The Lexus, the bodyguard — they would have only signaled Khalid’s high status and importance in Afghanistan.

Today they would have only put a target on his back.

He and Omar at last arrive at their point of business, the district in Kabul known as Traffic Square, its anchor the city’s department of motor vehicles. They park and get out. Terror-stricken faces, the distant boom of RPGs, smoky plumes of war on the southern horizons. It is chaos. It is also, at least for the moment, free of Talibs. Khalid motions to Omar to keep up, each of them in flowing Afghan garb to further blend into their surroundings as they approach their destination:

The travel agent’s shop.

When Kandahar fell, Khalid had given this travel agency his family’s passports in the hope that the agency could gin up visas to Uzbekistan for Khalid and his four children and wife. Khalid doesn’t know if the agency’s promise of new visas is real.

He’s here to find out.

Khalid walks into the shop. Packed, with everyone wanting the same thing: a way out of Kabul. Khalid sees his agent, an agent-liaison named Salim, and motions him over. Where are the visas? Khalid half-shouts over the din.

Salim says he doesn’t have them. If Khalid will wait just a bit longer, Salim can deliver everything Khalid wants.

Khalid doesn’t have time. Not today. So he recalibrates his plan.

“I need my passports then,” he tells Salim. He needs some form of identification if things keep getting worse.

Salim’s not sure where those are either and disappears for a moment and, ultimately, leads Khalid to the agency’s owner, and

the office in the back.

The panic in the shop, on the streets, the uncertainty of even the passports’ whereabouts — it puts Khalid on edge.

“Listen to me,” he says to the owner, a small man he doesn’t know. Khalid’s voice in its deep baritone edges into malevolence. “Don’t (expletive) with me.” He’s worried this shopkeeper has lost his passports, or sold them, or perhaps given them to some Talib as a way to curry favor.

“You better give me my passports!”

The shopkeeper, scared, opens a drawer.

The passports.

The owner hands them over and Khalid shuffles through: His three daughters’, ages nine to one; his son’s, age eight; his wife Horia’s; his own. A photo of his close-cropped hair and beard, his slight shoulders and skinny neck, next to his name:

Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi.

The man who offered 20 years of service to the Americans as a cultural adviser, interpreter and soldier. The man who tolerated some of his favorite Americans, like Capt. Scott Henkel, who could never pronounce the guttural Khalid correctly, and had settled on something easier: Kevin.

The man who has, above all, remained calm across those two decades. And so he tells himself he can remain calm today, through the collapse of his country, armed with little more than his family’s passports and his reputation.

Khalid tells himself he’s calm as he and Omar hop back in the Corolla and join the heavy sludge of traffic heading north. When the sludge becomes too thick, he exits the road and parks the Corolla at his father’s cousin Bashir’s, who agrees to take the car and hide it if only Khalid will leave. “It’s not safe for you here!” Bashir says, fully aware of Khalid’s two decades serving the Americans and United Nations and what that service means on a day like today.

Khalid tells himself he’s calm as he and Omar set out on foot, walking through a Kabul that is a bit more desperate — people looting stores — even as more people join the streets,

FROM HIS HOME IN COLORADO, HENKEL WAS WRACKED WITH HOPELESSNESS DURING THE BOTCHED TROOP WITHDRAWAL FROM AFGHANISTAN.

until foot traffic is itself a heavy sludge.

Khalid tells himself he’s calm when he drops off Omar at his parents’ apartment and his mother bawls, “What will happen to you now?”

He comforts her and his wife Horia phones, terrified of what’s happening in their well-off neighborhood. Everyone is armed and paranoid, she says. Khalid tries to quiet Horia’s concern, too. He’ll be back soon, he says.

Khalid tells himself he’s calm as he walks to his luxury apartment in his high-rise neighborhood, his nose and mouth wrapped in a scarf so that only his eyes show and no Taliban scout might identify him.

Khalid tells himself he’s calm when he enters his complex, across the street from the Ministry of Interior and, moments later, unlocks the door to his penthouse apartment, his four kids rushing into his arms, crying.

When he and Horia put the children to bed, Khalid says he’ll figure out a plan for tomorrow.

Horia can’t sleep, though, and he and Horia peer from one window and then another in their five-bedroom high-rise, looking for Talibs on their street. They hear the battle: the report of high-powered rifles, the blast of artillery.

Their street itself remains still, as calm as he likes to tell himself he is.

Khalid walks through this apartment, the reward of his key insight in life, the one he learned 17 years ago interviewing terrorists for U.S. Special Forces: To not just interpret what people were telling him but provide the context of what they meant. Americans loved this broader context, this richer story. It led to a story Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi told himself. He could better his life by relaying the full story of his country. So out on missions and even in firefights alongside Army leaders like Capt. Henkel, Khalid described the narrative of why events around them unfolded. The stories he relayed from his native Dari and Pashto into an increasingly flawless English indebted him to Henkel, and other Army leaders, and ultimately to its high brass, interpreting Afghanistan

for people like Gen. David Petraeus. As the years passed, Khalid went from telling the story of Afghanistan to shaping it. Working for various U.N.-affiliated organizations until, in 2018, Khalid became the CEO of a contracting firm with a budget as high as $260 million per project — and as many as 200 employees per project — that looked to rebuild Afghanistan as he and partners like

the U.N. saw fit.

In this luxury apartment, Khalid has told the story of a free Afghanistan and his work crafting it to members of Parliament and the minister of justice and foreign journalists.

In this luxury apartment, though, by the following morning, the story of Khalid’s life after 20 years of shaping it begins to unspool

IN THE CHAOS OF THE U.S. TROOP WITHDRAWAL, AHMAD KHALID

SIDDIQI SPENT DAYS TRYING TO GET HIMSELF AND HIS FAMILY OUT OF THE COUNTRY, ALL WHILE THE TALIBAN HUNTED FOR HIM.

AS THE PENTAGON, STATE DEPARTMENT AND BIDEN ADMINISTRATION FINGER-POINT WHOSE EXIT PLAN IS TO BLAME FOR THE DISASTROUS COLLAPSE IN AFGHANISTAN, SCOTT HENKEL THINKS OF THIS BROTHER, THE ONE WHOSE LIFE HAS FOR 15 YEARS BEEN INTERTWINED WITH HIS.

beyond his control, beyond his authorship.

The Taliban are on his street with a list of names on a sheet of paper, looking for the car or apartment that belongs to Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi. Where is he, the Talibs ask? Because they’ve been following his story, too. Khalid’s son takes a video on Khalid’s phone of the Talibs searching the street, trying to find which apartment is the Siddiqis.

Khalid sends the video over WhatsApp to one of his closest contacts, Capt. Henkel. In the message beneath the video, Siddiqi will later remember typing to Henkel, “I might not live any longer.” And then, ceding that he is no longer the author of his story: “Do whatever you can do to help get me out.”

HOW TO RESPOND to that? For a while, Henkel doesn’t. He and Kevin have shared those 400 missions and then the birth of kids — messaging, phoning long after Henkel’s tour — and then the raising of families and now a mutual aging into midlife. Henkel remembers them talking often of their dream, of the Siddiqis moving to Colorado and the families living next to one another, as true friends might.

As a friend and father, then, Henkel tries to imagine the pain Kevin feels now.

“I know it’s scary,” Henkel will later recalls typing. “Try to stay strong for your family.”

What an inadequate response. That video proves Henkel’s worst fear: Kevin’s forthcoming death.

The fear slows Henkel. He sludges through his house in suburban Denver. “Completely depressed,” he’ll later say. This depression is worse than what happened after the worst day: When a convoy that dropped him off at the airport for his

mid-deployment leave in October of ’06 got blown up by an IED as it returned to its base. That explosion leveled a whole city block in Kandahar and sent three of Henkel’s soldiers to the hospital with life-threatening burns. I should have been in that Humvee, Henkel had thought at the time. I should have kept my guys safe.

The guilt he felt for the bombing in Kandahar endured for years, well after his tour. It took Heidi Henkel telling Scott, over and over, that it wasn’t his fault.

The humvees his unit drove didn’t have the necessary armor at the beginning of Henkel’s deployment. Henkel hadn’t abided that. So he’d gone above his own boss to high Army brass and demanded his team be outfitted with equipment in keeping with its ambition, its 400-plus missions beyond the wire.

Henkel got his humvees their additional, and flame-suppressant, protection before Henkel’s mid-deployment leave. And that protection saved the lives of the four people in the Humvee the IED blew up in Kandahar. “You protected them that whole time,” Heidi had said.

One of Henkel’s noncommissioned officers, Robert Benton, says Henkel had an almost “fatherly” sense of protection on tour, unique among captains.

But now that familial duty is the cause of Henkel’s depression. Because now he can’t get Kevin out. Now he can’t keep Kevin safe. As with his mid-deployment leave, now he’s not there when Kevin needs him most. The despair grows worse, and not even Heidi Henkel can reach him.

Jeff Long tries. Long was one of Henkel’s soldiers; in fact, one of the men in the humvee the day the IED blew up. Long suffered

80 percent burns on his body but all these years later he’s fully recovered and working as a cop.

He phones Henkel not long after Kevin’s first despairing messages from Kabul. They both know Kevin had applied over a decade ago for something called a Special Immigration Visa. This would give him, due to his service to the U.S. military, a new life in America. But the Trump administration’s Muslim ban and then the xenophobic fear of people with brown skin and names like Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi entering the U.S. meant Kevin’s SIV application was refused. And not once, or twice, but a third time just weeks ago.

If the U.S. government won’t formally allow Kevin to enter, Henkel says, what can veterans like Long and Henkel do?

“Let’s try,” Long says. “Let’s just try to get him out.”

Something in the way Long says it — imploring him to be the motivated team leader one last time — awakens Henkel. The war is over, the war is lost, but if they can get Kevin out, all will not be.

“I’ll do whatever I can,” Henkel says to Long.

THERE ARE ALMOST too many people to kill. Under the Taliban’s new reign, the Talibs have to keep moving to find all the infidels. The Talibs with the sheet of paper asking about Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi leave to go on the hunt for other traitors, in other neighborhoods, with the promise to return later.

Peeking outside their windows, Khalid tells Horia that because the Talibs are after him, he’ll hide separately from her and the kids. He tells her to leave with the four children to her father’s home in Kabul.

ONE LANDLADY BACKED OUT OF LEASING A HOME TO KHALID AND HIS FAMILY BECAUSE SHE WORRIED THAT THE TALIBAN MIGHT BLOW UP THE RESIDENCE — IN SUBURBAN DENVER.

He’ll be in touch.

When Khalid emerges from the apartment building, his head once more wrapped in his scarf so only the eyes show, he goes first for his uncle’s house. Khalid stays a few hours before moving onto his father’s. A routine develops. A new safe house every three to five hours.

He must keep moving. He must keep his wits about him. A colleague at the United Nations will later say more remarkable than Khalid interpreting and shaping the story of Afghanistan is the way he reveals his intelligence. “He has deep, deep, deep insights” into the human condition, the colleague says. Khalid’s life has been occupation or war. By the time of Kabul’s collapse, then, he carries an acumen about humanity most people never develop. He moves to a different safe house whenever his spidey sense — informed by chatter he hears on the street or some urge he feels within — tells him to.

This wiliness complements a separate intelligence, too. Because Khalid’s childhood was the Soviet invasion and Afghanistan’s civil wars, his grandfather helped to raise him when his parents couldn’t. Khalid’s grandfather had been a federal judge before the Soviet takeover in 1979. He had a keen mind. When the formal education system collapsed as the country did, Khalid’s grandfather impressed upon a young Khalid the imperative to read. It will free your mind and liberate your future, he told Khalid. Khalid moved through book after book, in Dari, in Pashto and eventually in English. Khalid came to love what his grandfather did: the poetry of Rumi, the 13th-century Persian poet and Islamic scholar. Lines like “You were born with wings/Why prefer to crawl through life?” were not only beautiful

but profound to him.

The aspiration within them led Khalid to translate for the Americans after 9/11 and, just as important, drew more Westerners to him. Be they Army captains like Scott Henkel or United Nation careerists, these people saw in Ahmad Khalid Siddiqi an ambition for life greater than his surroundings and an intelligence to rise above them.

That’s why they were as loyal to him as he was to them. That’s why, now, with Kabul descending into a nightmare, he can call his contacts from around the world. Career U.S. diplomat Jim DeHart, charged with helping to get Americans out of Afghanistan. Veterans like Scott Henkel. Europeans who know British special forces in Kabul.

The 16th of August becomes the 17th and then the 18th and every message to Khalid becomes the same.

If you and your family can get to the airport, we can help you get onto a flight.

But the airport is in the same neighborhood as Khalid’s apartment, where Talibs continue to look for him. The airport is also a series of Taliban checkpoints leading up to its gates. Stories surface of pregnant Afghan women beaten with chains or Afghan men burned alive just outside the U.S.-established perimeter of the airport, where Marines and Special Forces attempt to evacuate all Americans before the August 30th deadline.

Day after sweltering day, Khalid sneaks from his hideouts and sees checkpoints and more chaos close to the airport. Thousands, tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands of people begging for seats on the dozens of remaining flights out. They walk around and sometimes over the bodies of certain “traitors,” shot dead and bloating in the August sun.

In his 20 years of service, Khalid has never witnessed anything like it. He tries to remain calm for Horia, who grows ever more concerned when she calls and worries they won’t find a way out.

He tells her they will.

He carries a pistol with him though. The truth is, it’s getting worse every day. The truth is, he won’t be able to hide forever. He has to consider all options.

He settles on a contingency, one as ruthless as it is brilliant. It’s a plan he shares with no one.

If he is found, he will take his gun and unload. If there are more Talibs than there are bullets in his chamber, he will ensure his family is never discovered.

He will save the last bullet for himself.

WITH SO LITTLE time before the Americans in the country leave Afghanistan with any wartime allies they can evacuate, every moment becomes a question Scott and Heidi Henkel must answer.

What else can we do right now?