For our 2024/2025 Europe season, we’re excited to introduce so much that’s new from the best cruise line sailing there. We have seven award-winning ships including three of our amazing Celebrity Edge ® Series ships, featuring our newest ship, Celebrity Ascent SM .

For the first time, we’re excited to have our revolutionary Edge ® Series ship, Celebrity Apex ®, sailing from London (Southampton) for a full season. Plus, find even more exciting itineraries and must-see places for every world traveler. With seven departure ports across Europe and itineraries ranging from 4 to 14 nights, you’re sure to find the perfect sailing to satisfy your wanderlust.

Book now with our current offer!

Book a balcony or higher with Cruise & Travel Masters by 4/15/23 , and receive an additional $100 onboard credit to use on any Celebrity Cruise.

the

“The basic philosophy of westward expansion has been, ‘look, there’s an unspoiled area –let’s go spoil it.’”

A REGION RECKONS WITH DECADES OF UNCHECKED GROWTH.

by kyle dunphey

by mya jaradat

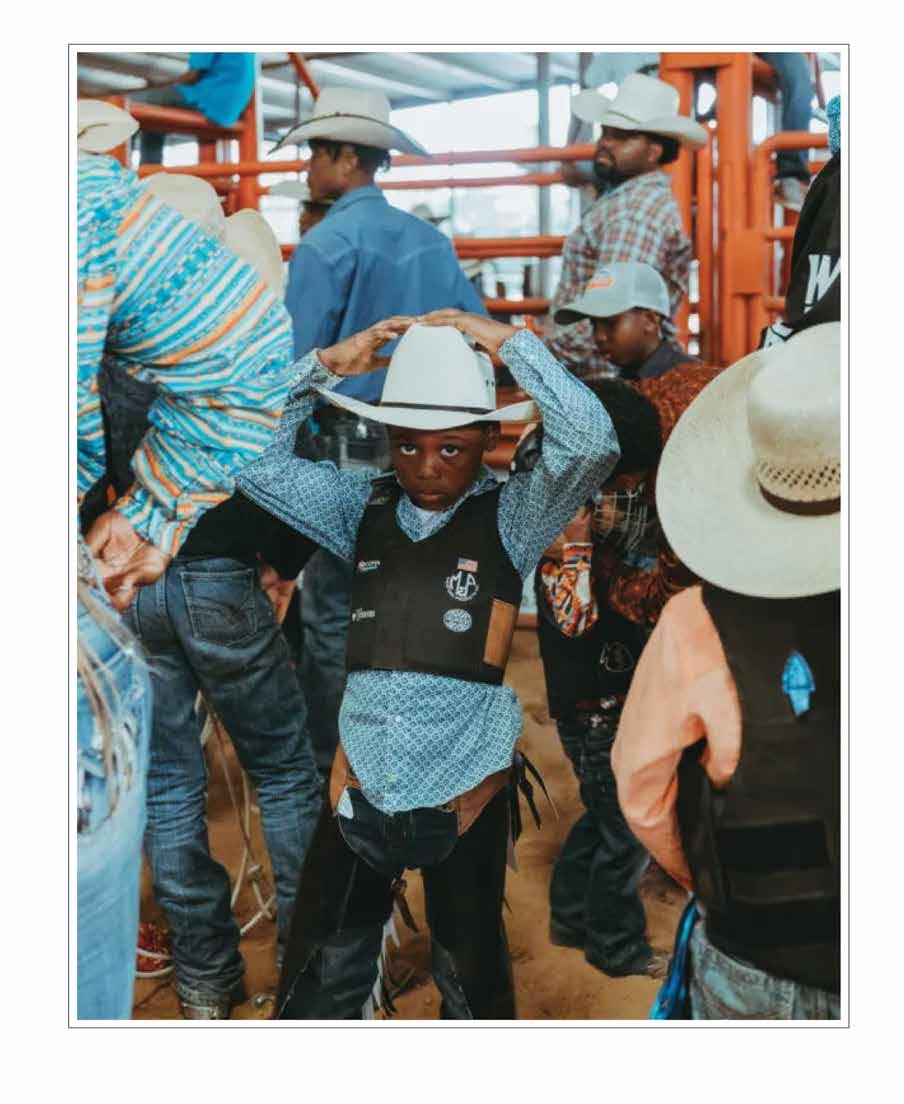

HOME RANGE

MEET

COWBOYS

ivan m c clellan

by meg walter

ethan bauer

“There’s pain and difficulty in bringing a story into creation that torments me. To think that a

to me.”

PRESIDENT & PUBLISHER

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

EDITOR

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

MANAGING EDITOR

DEPUTY EDITOR

SENIOR EDITORS

POLITICS EDITOR

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

STAFF WRITERS

WRITER-AT-LARGE

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

ART DIRECTORS

COPY CHIEF

COPY EDITORS

RESEARCH

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS

ROBIN RITCH

HAL BOYD

JESSE HYDE

ERIC GILLETT

MATTHEW BROWN

CHAD NIELSEN

JAMES R. GARDNER

LAUREN STEELE

SUZANNE BATES

DOUG WILKS

ETHAN BAUER

NATALIA GALICZA

MYA JARADAT

MICHAEL J. MOONEY

LOIS M. COLLINS

KELSEY DALLAS

JENNIFER GRAHAM

ALEXANDRA RAIN

GENEVIEVE VAHL

IAN SULLIVAN

BRENNA VATERLAUS

TODD CURTIS

CHRIS MILLER

MADISON TAYLOR

SARAH HARRIS

TYLER NELSON

ETHAN BAUER

ISABEL BOUTIETTE

MYA JARADAT

NATALIA GALICZA

LAURENZ BUSCH

ANNE DENNON

ALEXANDRA RAIN

GENEVIEVE VAHL

JEFFREY D. ALLRED

ANDREW COLIN BECK

GREG BULLA

RAVELL CALL

STEPHEN DUPONT

SPENSER HEAPS

KYLE HILTON

ASHYLN LASSON

JON KRAUSE

IVAN M C CLELLAN

MIDJOURNEY

TIM MOSSHOLDER

KRISTIN MURPHY

KUNSTA OUNKKA

MARK OWENS

CURTIS PARKER

LAURA SEITZ

ANDRE UCINI

SCOTT G. WINTERTON

DANIEL FRANCISCO

VICE PRESIDENT MARKETING

HEAD OF SALES

NATIONAL SALES MANAGER

PRODUCTION MANAGER

OPERATIONS MANAGER

SALLY STEED

CYNDI BROWN

MEGAN DONIO

BRITTANY M C CREADY

Deseret Magazine, Volume 3, Issue 22, ISSN PP324, is published 10 times a year by Deseret News Publishing Co., with double issues in January/February and July/August.

The Deseret News’ principal office is 55 N. 300 West, Ste 500, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Subscriptions are $29 a year. To subscribe visit pages.deseret.com/subscribe.

Copyright 2023, Deseret News Publishing Co. All rights reserved. Printed in the USA.

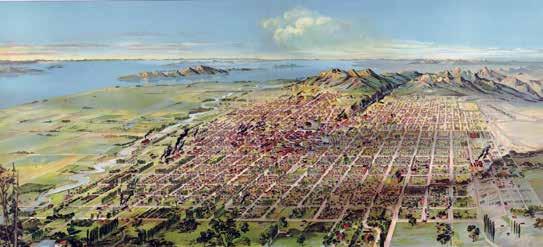

Ever since Meriwether Lewis and William Clark brought back tales from their eponymous expedition to the Pacific Ocean, the West has captivated the American mind and shaped how Americans see themselves — and perhaps even more, how the rest of the world sees Americans. Boots and cowboy hats. Pickup trucks and solitary highways. The rugged individualist making his way through wide-open spaces to build something new. Fed by books and movies and the belief in opportunity, the West is a vessel for America’s dreams about itself.

That image has shaped this land at least as much as reality, but it is largely a myth — a vision of limitless possibilities and endless resources. “The basic philosophy of westward expansion has been, ‘Look, there’s an unspoiled area – let’s go spoil it,’” Dan McCool, professor emeritus at the University of Utah, told staff writer Kyle Dunphey for this month’s cover package, “State of the West.” “It’s uncrowded — so let’s make it crowded. It’s clean — well, let’s go make it dirty. There’s no traffic — let’s increase the traffic.”

The West is America’s fastest-growing region and its economy is booming. But it’s no longer what it appeared to be when my ancestor William Hyde arrived in Salt Lake City in 1849, or even the 1940s, when William’s great-grandsons sang “Home on the Range” and “Don’t Fence Me In.” The fences were all built long ago; the outer limits of this land defined, demarcated, parceled and zoned. Now the questions are more about preservation than expansion, about water and air, a sort of reckoning with a century and a half of unchecked development.

For this issue, we set out to explore the region we call home,

how it is changing, and the future we face. An exclusive poll for Deseret Magazine conducted by Harris X revealed a seismic shift in public opinion. As Dunphey writes, “for decades, policymakers and business leaders have pushed a no-brakes growth mentality, but residents are beginning to question that philosophy.” Only one-third of respondents across the West approve of how their elected officials are managing population growth. About 60 percent think their state’s economic trends are harming residents. More results from this poll can be found on page 30 and online at Deseret.com.

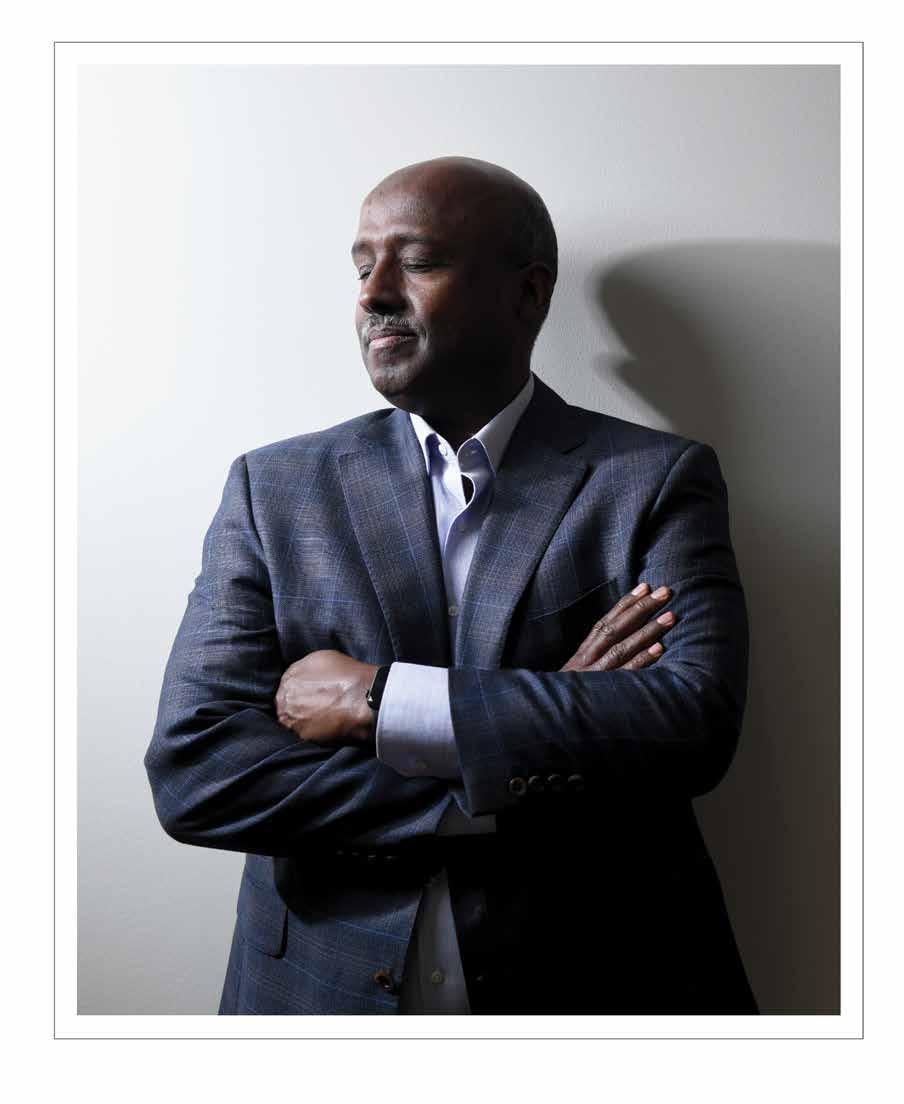

At the same time, some would argue the West has never been more dynamic and diverse. There are reasons to be excited about what comes next, including a few strong leaders you might not have read about, whose work outside the spotlight is shaping the future of this region. Meg Walter goes behind the scenes with Utah’s first lady, Abby Cox, whose compassionate brand of politics could offer conservatives a new way forward (page 44). Mya Jaradat introduces us to Aden Batar, a Somali refugee who is redefining what it means to be a citizen of the new West (page 38); and Ethan Bauer takes us to the Navajo Nation to meet Buu Nygren, the nation’s youngest-ever president (page 52).

The new West can feel daunting to folks who grew up here, and the old West may have never existed quite like we remember it. Both myths play out on a complex terrain that doesn’t give up its best secrets easily. I happen to think that’s a good thing — a little mystery never hurt anybody, and that’s half the reason the West is still where America goes to dream.

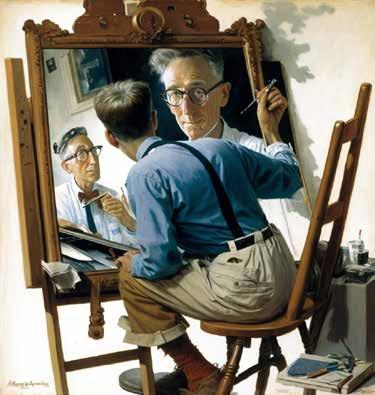

Galicza is a fellow for Deseret Magazine whose work has been published in the Miami Herald, Pulitzer Center, Flamingo Magazine and Miami New Times. A Florida native, her journalism has won state, regional and national recognition, including a Hearst Award while at the University of Florida. Her piece about artificial intelligence creating fine art is on page 76.

McClellan is a photojournalist and designer whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, i-D Magazine, Black Enterprise, Elle and The Moth — among others. With several national exhibitions, McClellan was awarded The 30: New and Emerging Photographers to Watch in 2022. His photography on Black cowboys in the West appears on page 58.

Mangual is head of research for the Policing and Public Safety Initiative at the Manhattan Institute, as well as a member of the Council on Criminal Justice. He is a contributing editor of City Journal and has authored several books. An excerpt from his latest book “Criminal (In)Justice: What the Push for Decarceration and Depolicing Gets Wrong and Who It Hurts Most,” is on page 70.

Robbins, an emeritus General Authority Seventy of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, is chairman of the church’s JustServe Steering Committee and an adviser of the Welfare and Self-Reliance Services Department. Before his full-time church service, Robbins was a co-founder and senior vice president of Franklin Quest. His commentary on the lost art of civic virtue is on page 13.

Walter is a features writer and editor for the Deseret News. Prior to joining the Deseret News, she was executive editor of the online storytelling website The Beehive and marketing director for the online tech and startup community hub Silicon Slopes. A lifelong Utahn, her profile of Utah’s first lady Abby Cox is on page 44.

Shapiro is a senior fellow and director of constitutional studies at the Manhattan Institute and a member of the Virginia Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. He is a former executive director of the Georgetown Center for the Constitution and vice president at the Cato Institute. His essay on politics polluting appointments to the Supreme Court is on page 66.

FOR DECEMBER’S “Good Works Issue,” sharon eubank, head of humanitarian initiatives for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and former first counselor in the church’s Relief Society general presidency, wrote about the powerful force of charitable giving (“Not Everything is Lost”). Eubank noted, “Study after study shows that positive giving in any measure with any currency lifts us personally and lifts our society as a whole.” Many readers agreed, including Paul Greenwood who shared the story and tweeted, “Once I gave a brand new pair of tennis shoes off my feet to a homeless guy; he smiled and put them on his bare feet. My heart softened towards my neighbor as it always does when I share.”

STAFF WRITER mya jaradat reported on the 988 mental health crisis line and who answers that call in our darkest moments (“End of the line”). With a 45 percent increase in overall volume of calls, texts and chats, the need for accessible mental health care is evident. Jaradat notes, “the weight of the work is a delicate thing to balance. But, it’s scientifically proven to be lifesaving for many who call.”

aaron sherinian, senior vice president of global reach for Desert Management Corp., and alumni of the State Department, tweeted the story to his 21k followers, “a look at #988 and the complexities of care in the times of crisis, this is a key story for our time.”

AUTHOR AND documentary producer william doyle conveyed the unlikely story of how the oddest couple of American politics saved religious liberty (“Brothers in Arms”). In the excerpt from his biography of the late Sen. Orrin Hatch, Doyle detailed the evolving relationship of Hatch and Sen. Ted Kennedy. Hatch admitted

one of the reasons he ran for the Senate was to fight Kennedy. Yet, the two were willing to compromise and work together for the betterment of the country. Reader rich barton, assistant director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, tweeted, “It’s sad that more politicians can’t set aside differences for the greater good as these two did.”

ALEXANDRA RAIN wrote about finding solace in the life she lost (“The Prodigal Mother”). A personal account on the impact of addiction, Rain discerned, “This story is about my experience, as I remember it. But it’s also just one

example among millions.” bill white, former board chair of Recovery Communities United, remarked the piece was eloquent and powerful, adding, “It poignantly captured the heartache and struggling hopes of living with an addicted parent.” The Texas District and County Attorneys Association tweeted the story, reflecting, “This emotionally raw, beautifully written snapshot of life as the child of a meth addict is a good reminder of how the negative impacts of drug abuse and addiction ripple through families and communities.”

IN OUR Last Word, staff writer lois collins talked to clinical psychologist Lisa Miller about the science behind spirituality as an antidepressant (“Finding the Light”) Miller states, “Despair and disorientation is the trailhead for spiritual awakening and we have the opportunity of a lifetime right now to help adolescents awaken their natural spirituality.” Reader brian chambers tweeted, “Insightful article on the importance of spirituality.”

PHOTOGRAPHY BY STEPHEN DUPONT

from “Are We Dead Yet?”, an ongoing series of works centered around our planet’s climate crisis focused on recent disasters and events in the photographer’s home country, Australia, including one of the worst droughts in living memory, catastrophic bush fires and the destruction of native forests.

IMAGE COURTESY OF VITAL IMPACTS

BY LYNN G. ROBBINS

George Washington was the most heroic figure in our nation’s founding and the foremost of the Founding Fathers. As great as Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and others were, it was the “Father of Our Country” who led the way — not only as the commander in chief of the Continental Army, and as president of the Philadelphia or Constitutional Convention — but as an exemplary gentleman and a champion of civility. He was a leader and hero in every sense of the word — a giant among men.

Washington lived his life by a set of principles, which he first came across at the age of 16 in the 110 “Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation,” a book which originated from a French etiquette manual written by Jesuits in 1595.

Below are a few of the 110 rules of civility that helped shape Washington’s character and public manner and earn him the love and admiration of generations.

1. Every action done in company, ought to be with some sign of respect, to those that are present.

19. Let your countenance be pleasant but in serious matters somewhat grave.

22. Show not yourself glad at the misfortune of another though he were your enemy.

58. Let your conversation be without malice or envy.

89. Speak not evil of the absent for it is unjust.

It is unsettling that Washington’s “Rules of Civility” have become a lost art in the public square, replaced by cynicism and a contagion of vicious incivility. Will our country survive the moral pandemic witnessed in modern-day politics, news outlets and social media?

Our country desperately needs leaders like Washington, whose example of civility helped overcome the political divisiveness of his day to unite the 13 colonies.

As a rule, most people are civil and kind — most of the time. The test of a truly great man or woman is how they act under pressure in a crisis

and in stressful situations. The great 20th century author C.S. Lewis shares this wise insight on “rats in the cellar”:

“When I come to my evening prayers and try to reckon up the sins of the day, nine times out of ten the most obvious one is some sin against charity; I have sulked or snapped or sneered or snubbed or stormed. And the excuse that immediately springs to my mind is that the provocation was so sudden and unexpected: I was caught off my guard, I had not time to collect myself. … On the other hand, surely what a man does when he is taken off his guard is the best evidence for what sort of a man he is? Surely what pops out before the man has time to put on a disguise is the truth? If there are rats in a cellar you are most likely to see them if you go in very suddenly. But the suddenness does not create the rats: It only prevents them from hiding. In the same way the suddenness of the provocation does not make me an ill-tempered man: It only shows me what an ill-tempered man I am. The rats are always there in the cellar, but if you go in shouting and noisily they will have taken cover before you switch on the light.”

Because none of us are perfect, we each have “rats in the cellar.” It is painful for each of us to reflect on this quote attributed to the actor and comedian Groucho Marx, “If you speak when angry, you’ll make the best speech you’ll ever regret.”

For our public servants, and for each of us, it would be wise to “consider your ways” and behavior to see how far we may have strayed from the example of the Founding Fathers.

Like Washington, Franklin desired to pattern his life based upon a set of principles he believed would make him a better man and public servant.

In 1726, at age 20, Franklin had identified his “Plan of Conduct.” Two of the principles of civility he wanted to live by were:

“To endeavour to speak truth in every instance; to give nobody expectations that are not likely to be answered, but aim at sincerity in every word and action — the most amiable excellence in a rational being.

I resolve to speak ill of no man whatever, not even in a matter of truth; but rather by some means excuse the faults I hear charged upon others, and upon proper occasions speak all the good I know of everybody.”

As we consider civility in our public discourse, consider these additional quotes by two more of the other founders:

James Madison: “To suppose that any form of government will secure liberty or happiness without any virtue in the people, is a chimerical idea.”

Samuel Adams: “Neither the wisest constitution nor the wisest laws will secure the liberty and happiness of a people whose manners are universally corrupt. He therefore is the truest friend of the liberty of his country who tries most to promote its virtue.”

These insights of the founders are not only wise advice to maintain the stability of our country, but a warning that we cannot remain strong in the absence of virtue, morality and civility. It is imperative that we return to our roots of civility. The founders would never have reached a compromise in the Constitutional Convention without them, and neither can we survive going forward without them.

LYNN G. ROBBINS IS AN EMERITUS GENERAL AUTHORITY SEVENTY FOR THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS.

BY MARC NIELSEN

The Intermountain West is booming. From Phoenix to Boise and Denver, descendants of pioneers and Indigenous peoples are seeing their homeland take on new forms. Cranes tower above skyscrapers and apartment buildings. Burgeoning subdivisions stretch the seams of smaller towns on the outskirts. It’s easy to blame California and the tech industry, but what does all this change really look like? Here’s the Breakdown.

Utah is America’s fastest-growing state, per the 2020 census, with 22.8 percent growth in adult population over 2010. Idaho, Colorado and Nevada round out the top five (along with Texas), while Arizona ranks eighth at 16.4 percent. Overall, the U.S. grew by just 10.1 percent in that same period.

Even before the latest wave of growth, as much as 90 percent of the population in Utah, Arizona and Nevada lived in urban areas, per the U.S. Census Bureau.

A 2016 Brookings report coined the term “Mountain Megas” for large metropolitan areas like Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Denver and Albuquerque, characterized by their relative isolation from each other between large stretches of rural land — unlike their often clustered counterparts on the coasts.

“Rural gentrifiers can be seen as, in effect, ‘permanent tourists.’” — J. Dwight Hines, a cultural anthropologist and professor of literary arts and social justice studies at Point Park University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Even in rural areas, growth has been uneven. A pair of BYU professors have found that “New West” counties, largely characterized by outdoor recreation, have grown both economically and demographically, with new arrivals earning 6 percent higher per-capita income than locals and 21 percent higher than outgoing migrants. But “Old West” counties, built around farming and mining, have lost both population and buying power. These contrasts underscore political conflicts — like choosing between extractive land use and preserving natural beauty.

The region is experiencing massive growth in its Hispanic population, echoing a nationwide trend toward increased diversity. According to a Brookings census analysis, this trend reaches beyond the “megas” to smaller but growing communities. From 2010 to 2020, the number of Hispanics grew by 39.6 percent in Idaho Falls, 38.7 percent in Colorado Springs, and a whopping 51.9 percent in St. George, Utah. One likely driver is booming construction, an industry where 30 percent of workers are Hispanic, per the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Asian Americans are America’s fastest-growing racial group, increasing 35.6 percent from 2010 to 2020. While they remain largely concentrated in a few large coastal cities, “megas” like Boise, Denver and Las Vegas have seen more than 40 percent growth; that number exceeding 50 percent in Phoenix and Salt Lake City. This group’s raw numbers may be smaller, but they still enrich an increasingly diverse population.

Asian American population growth from 2010-2020:

35.6% United States

40%+ Boise, Denver, Las Vegas

50%+ Phoenix, Salt Lake City

As of 2018, Utah was not among the top 10 destinations for those fleeing the Golden State, but California was already the top source of in-migrants to Utah at 16.6 percent, according to the University of Utah’s Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute. That was before the COVID-19 pandemic sparked the rise of remote work, freeing many workers to live wherever they can find Wi-Fi — the state’s natural beauty is a popular draw — and an influx of tech companies to the “Silicon Slopes.” About half the people who move to Utah come from elsewhere in the West.

The region has always been a harsh environment for people, but some worry that this latest growth is pushing the limit of its resources. According to a joint study from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (a Massachusetts think tank) and the Sonoran Institute (a conservation nonprofit based in Tucson), demand has already outstripped the supply of water in the Colorado River system. About 75 percent goes to agriculture, but it’s the increase in municipal and industrial users that has driven demand over the edge.

Growth and new voting patterns could lend the Intermountain West more political power. Not only has the region gained 14 seats in the U.S. House since 1980, but challenges to its conservative tradition could — perhaps surprisingly — make it more influential in national elections, which have become increasingly focused on swing states. That has long cast a spotlight on the Midwest, but recent cycles have seen Colorado, Nevada and Arizona join their ranks. The latter proved crucial in the last presidential election, choosing a Democrat for the first time since 1996.

“Overall, rather than allout change, the western United States has and is likely to continue experiencing a layering — a keeping of the old while adding the new.” — Donna Lybecker, political science chair at Idaho State University, in “The Environmental Politics and Policy of Western Public Lands,” published by Oregon State University.

THE

IMMIGRATION is always a hot-button political issue, with a constant flow of migrants and refugees crossing the 1,952-mile southern border. But even amid ongoing battles over policies like Title 42 — which prevents asylum-seekers from entering the United States before their cases are resolved — leaders from both political parties are weighing reforms, acknowledging the role these newcomers play in the economy. In 2021, for example, House Democrats passed the Farm Workforce Modernization Act with some GOP support — and compromise. Meanwhile, some thinkers advocate for a broader reimagining of both the system and how we view it.

THE GREAT IMMIGRATION challenge of our era is not at the borders but inside them. It’s not who gets in, but what happens once they’re here. As Congress remains gridlocked, why not let states decide how the foreign-born get to belong? Consider education, abortion, health care, gun control and marijuana. States blue and red are going their own way on all these issues, often in conflict with one another and sometimes with Washington.

It is already happening, but the question is how much power over immigration will eventually devolve to the states. They can create a fragmented landscape of places that welcome immigrants and others that close their doors. And within that patchwork, we might eventually end up with a federal policy that works.

States differ in the access to health care and safety-net programs they make available to immigrants. Dreamers — unauthorized immigrants who arrived as children — are welcomed into public higher education in some states but shunned in others. Some make it easier for professionals trained abroad to get licenses; others make it harder. As states diverge further, immigrants would choose to settle in welcoming places and avoid unfriendly places.

The United States can have only one form of citizenship, but states can compete over access to the world’s best brains, to the people who will care for aging boomers and to young adults with years ahead of them to pay taxes and bear children. Americans and their marketplaces have a way of sorting these things out.

ADAPTED FROM AN OP-ED IN THE NEW YORK TIMES BY ROBERTO A. SURO, A PROFESSOR OF JOURNALISM AND PUBLIC POLICY AT USC ANNENBERG, SPECIALIZING IN IMMIGRATION AND THE LATINO POPULATION.

THE FARM WORKFORCE Modernization Act passed in 2021 by the House — not the Senate — treats immigration as a practical matter, incorporating hard-fought compromises that address conservative values and concerns. Democratic support is a given, but there are compelling reasons why 13 Republicans co-sponsored the bill.

For one, it could help address rising food costs that contribute to inflation. A report issued in September 2022 by the Cato Institute detailed how the bill’s reforms would reduce agricultural labor costs by about $1 billion in the first year and $1.8 billion in the second, “which would lead to more workers hired, more productivity and lower prices for consumers.”

It would also make E-Verify — the web-based system that lets employers confirm that hirees are eligible to work in the U.S. — mandatory for all agricultural workers. Further, certified agricultural workers would remain ineligible for many forms of federally funded public benefits, even as the bill brings many more workers into the tax-paying world.

Finally, the bill would directly benefit rural America, increasing tax revenue in some deeply red states, stimulating rental and real estate markets in rural communities with 10 years of farmworker housing vouchers and grants, and funding new housing developments.

This act honors the idea that immigrants should “get in line and wait their turn,” but also acknowledges the crucial undocumented workforce that is already here, establishing serious residency and work requirements before immigrants can gain a safe and stable place in society.

ADAPTED FROM AN OP-ED IN THE LOS ANGELES TIMES BY DW GIBSON, A RESEARCH DIRECTOR AT IDEASPACE.COM, A NONPROFIT FOCUSED ON BIPARTISAN IMMIGRATION POLICY, AND AUTHOR OF “14 MILES: BUILDING THE BORDER WALL.”

BY MYA JARADAT

Cherri Foytlin didn’t set out to become an activist. She is a mother of six, married to a man who worked on an oil rig in south Louisiana while she worked at a small-town paper, writing features about things like who grew the biggest cauliflower that year.

But when the BP oil spill happened in 2010, killing 11 and releasing almost four million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, BP invited Foytlin, like all of the state’s press, to go out on a tour of the disaster.

“It was a little show for us,” she recalls. BP took her and the other journalists out on boats and then-Gov. Bobby Jindal came to speak to the press. “I wanted to talk to somebody who’s a fisherman or a person that has to clean up.”

So she went back later on her own. After tooling around a bit, she finally convinced a “big Cajun fisherman” to take her out on his boat, along with the man’s five-year-old son. As they idled through the blob of oil, the father cried. He’d lost his livelihood; his ability to take care of his family.

That night, when she went home, she looked in the mirror “and I remember very clearly saying, ‘Wow, what have I done to contribute to this? How can I change that? And how can I even imagine giving the children a world that’s like this?’”

Perhaps without even fully realizing it at that moment, Foytlin became a part of something much bigger: a legacy of American women — and, more specifically, mothers — who have come together for generations to move the needle on social, political and environmental issues that affect us all.

We see it in the news cycle every generation. Women in general — and moms, in particular — compose a huge part of the

“AS A MOM, DON’T I HAVE A DUTY — A MORAL DIRECTIVE — TO GET INVOLVED?”

electorate, making the “mom vote” highly sought after. Women were credited with fueling a blue wave in the 2018 midterms. Ahead of the 2022 midterms, Politico called women over 50 the “most important voting bloc” to the election, explaining that the group is not only the largest bloc of voters but the largest bloc of swing voters.

The activism of women, as much as their

votes, can impact our country. Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America now has a chapter in every state; and the group claims numerous political wins on both the local and federal level, from California’s new law that is intended to stop the spread of unlicensed guns to the Biden administration’s “Safer America Plan.”

But the first steps for these big movements that mothers create are often relatively small.

FOR 18 MONTHS, Mary Alice Hatch stood by, devastated, as her daughter experienced so much physical pain from a mystery illness that she was, at one point, suicidal. She missed school, social events and some of the most important years of her young life.

Desperate for answers, Hatch turned to the Yellow Pages. She found a pain specialist who knew immediately what the problem was: endometriosis. Soon thereafter, Hatch’s daughter had a diagnosis; eventually, she had surgery that led to a recovery. With the right information, the winding and difficult path her family journeyed felt much clearer. But if it was this challenging for a family with the resources to find a way forward, how impossible might it feel for others?

Determined to help, Hatch has worked

relentlessly to fund endometriosis research and spread awareness of the disease. “We saw an attorney in the D.C. metro area who told us that endometriosis wasn’t on the Department of Defense’s list of diseases,” Hatch recalls. “That’s a massive deal because the list allows federal funds to be allocated to research.” Hatch’s father-in-law, the late Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch, reached out to Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren. Together, they spearheaded a bipartisan effort to get research funding for endometriosis from the Department of Defense.

Now, Hatch aspires to create legislation that will make women’s health procedures

more accessible. “It’s important for me to say that I couldn’t have done any of this alone,” she says. “No matter what resources you have, you still can’t affect change without a community.”

Foytlin has also worked to create a community to affect change. After the oil spill, she hosted a fundraiser in her home, which included the photos Foytlin had taken of the disaster. The proceeds went to help those impacted by the oil spill, including the Cajun fisherman who’d taken her out on his boat. Foytlin and other locals began to coordinate with the Environmental Protection Agency to bring speakers to southern

Louisiana to talk about the issues affecting them.

The small injustices many people experienced added up to a much larger injustice, she realized, which primarily impacts communities of color. Many rural, poor and minority communities “have some sort of chemical plant or leftovers from bombs and ammunition from the military,” says Foytlin, because “they don’t have the social capital to protect themselves.” The ironically named Rolling Hills “pit,” a landfill near Pensacola’s Wedgewood community — a predominantly Black neighborhood in Escambia County, Florida — is a prime example. Locals reportedly suffer from higher cancer rates than the national average, which locals attributed to the ongoing dumping of various toxic chemicals before, during and since the 2010 BP oil spill.

Foytlin went on to partner with other Native American women to co-found the L’eau Est La Vie (Water is Life) camp in hopes of preventing the Bayou Bridge Pipeline from being built on the land. “As a mom, don’t I have a duty — a moral directive — to get involved?”

MOTHERS ARE OFTEN at the forefront of activism both in the United States and internationally, says Danielle Poe, the University of Dayton’s dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and author of the book “Maternal Activism: The Ethical Ambiguity Faced by Mothers Confronting Injustice.”

“I can’t think of any culture that doesn’t have a special respect for mothers,” she says, explaining that maternal activism works for a wide range of reasons in a variety of settings: authorities are less likely to use violence against moms and, because everyone has a mother, they’re highly relatable.

Mary Harris Jones — who later became known as “Mother Jones” — led millions of workers in the late 1800s to demand fair labor laws. Jones protested on behalf of labor rights and against child labor across the country — even spending time in Utah and

“I REMEMBER VERY CLEARLY SAYING, ‘WOW, WHAT HAVE I DONE TO CONTRIBUTE TO THIS? HOW CAN I CHANGE THAT? AND HOW CAN I EVEN IMAGINE GIVING THE CHILDREN A WORLD THAT’S LIKE THIS?’”

Colorado to do so. This movement led to riots and a federal holiday we all now know and observe on the first Monday of every September.

Mothers were also instrumental in gaining American women the right to vote. The suffrage movement was effective, in part, because it played on the idea of “women’s role as nurturers and a belief in women’s moral superiority,” according to the Library of Congress, using both as “arguments to convince the American public that women should have the right to vote.”

This emotional reasoning wove its way through the generations. In 1973, Carolista Baum stood in the path of a moving bulldozer to stop it from destroying the Jockey’s Ridge sand dunes — the tallest sand dune system on the Atlantic Coast. The landmark, which is 7,000 years old, was threatened by the development of condominiums at the time. But the impetus for Baum’s activism wasn’t to control corporate development. It was much simpler: Her three children loved climbing and exploring the dunes, and she didn’t want them, or other children, to lose that opportunity. After Baum’s 1973 protest, the dunes were declared a national natural landmark and, in 1975, it became a state park, guaranteeing its preservation for generations to come.

This legacy has led to larger mother-led organizations that have become some of the most politically effective groups in American history. Mothers Against Drunk Driving is a perfect example, Poe says. The organization was founded in 1980 by Candace Lightner after her daughter was killed by a drunken driver. It quickly grew into a large nonprofit organization that is funded in a variety of ways, including individual contributions, government grants and corporate donations. The organization successfully advocated for higher drinking ages in all 50 states. MADD was also instrumental in getting stricter drunken driving laws passed throughout the country. A recent success is the inclusion of a device in all new cars that will prevent people from

driving drunk, a provision included in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed in November 2021.

RELINQUISHING THE ACTIVIST title and centering one’s identity as a mother — intentionally or not — is often a powerful tactic that ultimately makes these women more sympathetic, Poe explains. Mothers, says Poe, are “uniquely positioned to be witnesses to loss. … When we hear their loss, it also brings to light social issues and harms that we otherwise don’t see.”

In the beginning, Foytlin didn’t think of herself as an activist, though she later came to embrace the label. And while she and other activists weren’t successful in their attempt to stop the Bayou Bridge oil pipeline from being built in Louisiana, Foytlin believes her work has made a lasting impact on the world. “When you stand up — when people witness your courage and your mission and your focus and your passion — it’s not a failure.”

Today, Foytlin is focused on training the next generation of activists, namely her own children. Two of her daughters are currently in college, one majoring in environmental science and the other in filmmaking — a powerful medium for raising awareness and bringing about change.

During her journey to create better access to health care options for people experiencing endometriosis, Hatch has also found how important it is to use the opportunities one has to create opportunity for many. “For anyone who feels passionate about an issue or feels a need for change, don’t give up,” she says. “You don’t have to feel alone. Find an organization, call them up and ask, ‘What can I do?’” From her experience, Hatch has found that a path will open up from asking that question. And often, it’s a path that can leave the world better for the next generation.

“We won’t create the perfect world for them,” Foytlin resolves. “But we can give them a chance to create their own. And that’s where my goal is: to create those steps so that they can carry the light forward.”

BY DOUG WILKS

Arthur Brooks has no shortage of stories. He dropped out of college, chased a dream to Spain (her name is Ester), and brought along the French horn he thought would be the focus of his life, landing a spot in the City Orchestra of Barcelona. But the stories are incidental to the foundation of faith and family that makes Brooks one of the nation’s most sought-after writers and speakers.

Harvard has him now, decades removed from his untraditional path to a Ph.D and one-time leadership of one of the nation’s top think tanks, the American Enterprise Institute. Today he teaches some of America’s finest students concepts like “human flourishing” and “thriving.” He’s an academic concerned about America, the family, the role of faith, education and the need for connection.

Simply put, he’s on a mission to teach happiness and he uses the power of science, faith and love to share the wisdom he’s gained from thoughtful scholarship and experience. The path he walks comes with equal parts warning and optimism. Here then is my conversation with the professor of happiness.

YOU’VE COMPARED AMERICA TO A MARRIED COUPLE GOING THROUGH A BAD STRETCH. WHAT DID YOU MEAN BY THAT?

One of the interesting things about all conflict, whether it’s people who can’t get along politically or a couple on their way to divorce court is it’s all based on the same kind of conflict. And that conflict is this mistaken idea that I love but you hate. That’s called motive

WHEN PEOPLE ARE WILLING TO SAY WHAT THEY REALLY THINK, IT’S BETTER. THEY CAN’T REALLY FIND THEIR WAY BACK TO BITTERNESS AND POLARIZATION AFTER THAT.

attribution asymmetry, which is a real fancy, complicated sounding thing for a very simple idea that there’s an error in the way that we communicate. Most conflicts are based on this error. For example, someone in a political disagreement might be thinking, “You know I love this country. I love it and you hate it. Obviously, you’re unpatriotic and your values are weakening my country.” And

the other person says, “No, I’m the one who loves this country and this people and you’re the one who hates it and is not acting in the right way.”

Couples do the same thing. Research shows when couples are on their way to divorce court, one might say, “I love our family, but he hates me. He actually hates me,” and the husband is like, “Are you kidding me? She’s the one who hates, I’m the one who loves.” If you can resolve that it’s a huge opportunity for people to actually express how they really feel. Unfortunately, most people don’t. And that’s what’s going on in America today.

I do a lot of public opinion work and I’m privileged to see a whole lot of data on people’s attitudes about this country. The vast majority of Americans don’t want to live anyplace else. They’re proud and they love living in this country.

SO HOW DO YOU IMPRESS UPON AMERICANS THAT THEY NEED TO CHANGE?

When people actually understand what the nature of the conflict is, you can do a lot better. One of the things we find is that couples can reconcile if they can be willing to say what they really think. Most people

think that you’re going to ruin a marriage if people actually say what they think. The truth is the opposite. Because most married couples love each other. But they think that the other one hates them and so they’re very defensive and their defensive reaction makes the other person think that their partner hates them.

When people are willing to say what they really think, it’s better. A lot of experiments that I’ve done on public policy are bringing people together. I’ll bring Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump supporters together to talk about their common loves, which activates parts of the brain that are dedicated to affection, love and positive emotion. And they can’t really find their way back to bitterness and polarization and hatred after that.

So for example, I’ll bring people together who are on opposite sides of the most contentious debates of the time — abortion, guns, immigration, whatever it happens to be — and I’ll say, “We’re going to talk about this stuff, don’t worry. But in the meantime, I’d like you to tell each other about your kids and grandkids.” And oh, man, I mean, it’s like they grew up together. You never hate somebody who’s telling you about their kids and their grandkids and the problems that they’re having with their teenagers.

And after that, they can talk about abortion and they want to understand each other in an entirely different way. And this is a lot more of what we need to do. We need leaders that are willing to do this as opposed to leaders in politics and media

and academia and the schools and even corporations who are dining out on setting us against each other.

Hate is very profitable. Anger is profitable. Fear is unbelievably profitable. And we have a motive in our outrage industrial complex in this country, and the political system and the media that feed it, to get us to not really express what’s written on our hearts. And the result of that is that more than 90 percent of Americans hate how divided we’ve become. We don’t like our politics. We don’t respect what’s going on in most of the media and that’s a big opportunity. That’s even a profit opportunity, quite frankly, and we just need to figure out a way for people to understand how to do it and how to run with that opportunity.

YOU TEACH AT HARVARD. CAN YOU DESCRIBE YOUR COURSE AND WHAT YOU’VE OBSERVED AMONG YOUR STUDENTS?

I teach at the Harvard Business School and I have a class called Leadership and Happiness, which sounds kind of weird, you know, how is that a business subject? But as far as I’m concerned, it’s a core competency to worldly success. We have this conception that if I’m successful, I have money, power, admiration. And if I’m successful, then I’ll get happiness and it’s actually not true. According to data, the truth is exactly the opposite. What you find is that people who pursue their happiness in the right and healthy way, they tend to be more successful in terms of the other things.

And so what I’m trying to do is change the direction of causality with my students to help them understand what they really hunger for is faith and family and friendship and service to other people. They want love and to be loved. And that’s what I talk about in a very scientific way.

This is not just self-improvement or counseling or psychotherapy or woowoo. We’re talking about cutting-edge neuroscience and social scientific evidence on how their romantic life can be healthier, how the relationship with their parents can be better, how they can be less lonely and have more enduring friendships, and how they can have a transcendental metaphysical walk in their life. Perhaps that’s the religion

of their childhood, and how all of this can be put together like bricks into a wall that can make them into a complete person who also not incidentally winds up being very successful in business.

ARE YOUR STUDENTS CYNICAL ABOUT THIS OR ARE THEY EAGER TO EMBRACE IT?

It’s not a requirement. They don’t have to take this class, but I have about 400 students on the waiting list. There’s also an illegal Zoom link they think I don’t know about. So this is a popular class.

They’re not cynical about it at all. Look, if I came in and said, “Let me give you my opinion on what your family is supposed to look like,” nobody’s going to take or get college credit for that. This is the real stuff on what research is telling us. I’m talking to them about the neurophysiological structure of the brain, on how neurotransmitters are actually the reason that they feel the way they do, or how the limbic system can be managed by the prefrontal cortex of the brain so you can manage your emotions and they don’t manage you.

How do you manage you? It really starts with knowledge, it starts with science.

YOU WERE A PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN. BUT YOU’VE SAID THERE WAS A MOMENT YOU STOPPED GETTING BETTER, AND IT WAS A TURNING POINT IN YOUR LIFE.

As a kid, I thought I was going to be a professional musician for the rest of my life. My ambition was to be the world’s greatest French horn player. And for a while it looked like there was actually a chance that I could do a lot with it. I was pretty proficient. I went professional when I was 19. I was in a very good symphony orchestra and I was starting to get a lot of work that was, by my own judgment, where I wanted to be.

The trouble is that by about my mid 20s, I wasn’t getting better anymore. It was a very alarming thing. And I couldn’t quite figure out what’s going on. Now, subsequently, I’ve studied this a little bit more and a lot of classical musicians and athletes and people pursuing interests that require a lot of skill early on in life find that they have

an early turn in their skill and they don’t get better. It’s quite mysterious, but it’s very common as it turns out. And for me, it was just the end because what else can I do as a college dropout?

All I cared about was the horn. Music was everything. But my wife saved me. And the reason is because she didn’t marry me because I was a French horn player. She married me because of the man that I was and the man I was going to be. And she said, “You know, you’re my husband and you’re a complete person. And you’re a hard worker, and you care about doing things that really matter. And you can do that.”

DO YOU DESCRIBE THAT AS FAITH? AND WHERE DID THAT COME FROM?

I don’t know. Where does that kind of faith come from? I don’t know. I mean, you need to have somebody who loves you and believes in you. It’s really important. I chalk this up to the fact that I had a team, me and my wife, we were a team. And you know, she really believed in me. It was the most amazing thing.

ONE MORE ABOUT MUSIC: WHAT IS THE BEST MUSIC?

My favorite composer is Johann Sebastian Bach. He’s sometimes called the fifth evangelist. And the reason is because he was somebody who used music to express his faith in a more effective and penetrating way than probably anybody ever has. He was a very devout Christian. His family Bible was dog-eared and he was writing in the margins. At the end of every single score of the 1,000 pieces he published he would write, “to the glory of God.” When asked before the end of his life why he wrote music, he said, “The aim and final end of all music should be nothing more than the glory of God and the refreshment of the soul.”

He knew something about the cosmic nature of how these harmonies affect us. So what’s the best sound? Bach, man, it’s Bach. If I’m going to listen to one thing for the rest of my life, I hope I’m listening to Bach when I pass on.

HOW DOES THE GLORIFICATION OF GOD INFORM YOUR LIFE?

The most important thing in my life is my

Christian faith. And it’s funny because a lot of people, they sort of believe that, but it takes a little bit of focus to say that right? But it’s really true. I grew up in a Christian family. I’m a very lucky man in this way that my parents passed on their faith to me. I was raised in a Christian home and I converted to Catholicism as a teenager as an act of teenage rebellion and my parents quite wisely were not that alarmed. They probably acted a little bit alarmed to give me the satisfaction, I suppose, but they were happy I was still going to church.

And I married a Catholic girl from a nonpracticing family, who subsequently pursued graduate education in theology and is teaching to immigrant women in native Spanish on Christian teaching. And to us, this is just, fundamental. It’s who we are as people. We raised our kids as Christian people, and they love God a lot. And they’re working to refresh the souls of others in different ways. I got one who is a middle school math teacher, I have one who’s in the U.S. Marine Corps. And I have one who is still in college, and they’re all glorifying God in their own ways. And it’s the most important thing in their life, too. And I’m really, really grateful for that.

THAT’S REALLY LOVELY. IT LEADS ME TO MY FINAL QUESTION. ARTHUR BROOKS, ARE YOU HAPPY?

Happiness is not a destination. It’s not a destination in the mortal coil. I believe that happiness is only a destination in the supernatural, in the eternal sense. While we’re alive on this earth, happiness is a direction. The promise that I can give to my students is not that you’re going to find happiness like some mythical Shangri La, some city of Eldorado. I believe that you will, but not in this life.

However, I can promise that you can get happier if you understand what happiness is and how to pursue it. If you commit yourself to good and healthy practices that involve faith and family, love of others and service, and if you commit yourself to sharing these ideas, you will get happier.

Am I happy? Not yet. Am I happier? Every year.

WILL A SUPREME COURT RULING ON SAME-SEX MARRIAGE RESHAPE THE FIRST AMENDMENT?

BY KELSEY DALLAS

Around seven years ago, Lorie Smith was ready to take a professional leap. She wanted to expand her web design business into the world of weddings and start offering custom website services to engaged couples.

There was just one problem: Smith had a feeling that particular leap would get her in trouble with the law.

That hunch stemmed from news reports about another Colorado business owner and Christian who, like Smith, believes marriage should be reserved for unions between a man and a woman. By 2016, Jack Phillips, a baker, had already spent four years in court defending his decision not to design a custom wedding cake for a gay couple.

If Smith began offering wedding websites but turned away members of the LGBTQ community, she seemed destined for a similar fate. She was so torn about what to do that she turned to her pastor for help and then, after praying about it, to a famous group of religious freedom attorneys.

As a result of those conversations, Smith held off on expanding her business. Instead, she filed a lawsuit, which, almost seven years later, has become one of the most

contentious battles of the U.S. Supreme Court’s current term.

With the case, Smith is fighting for protection from Colorado’s public accommodations law, which prohibits discriminating against customers because of their sexual orientation, among other protected traits. She argues that being forced to design websites for gay couples would violate her free

“THIS CASE IS ABOUT WHETHER THE GOVERNMENT CAN FORCE ARTISTS TO SAY THINGS THEY DON’T BELIEVE.”

speech, since, in her mind, such a business transaction would represent a message of support for same-sex marriage.

“Lorie serves everyone, but she cannot express every message through her custom artwork,” says Jake Warner, senior counsel for Smith’s law firm, the Alliance Defending Freedom. He noted that Smith does serve LGBTQ customers in other contexts.

Smith’s supporters, including gay rights activist Dale Carpenter, filed amicus briefs arguing to protect artistic speech. Some supporters have argued, for example, that a Black tattoo artist shouldn’t be forced to provide racist symbols for customers.

Smith’s opponents object to the case for multiple reasons, not least of which is the fact that Smith filed the lawsuit before she started selling wedding websites. Unlike Phillips’ legal battle, which involved a gay couple, Charlie Craig and David Mullins, describing what it felt like to be turned away, Smith’s features a hypothetical scenario that’s more difficult to debate.

“(The case) doesn’t offer real LGBTQ people as sympathetic characters to demonstrate the harm,” says Rachel Laser, president and CEO of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, which filed a Supreme Court brief opposing Smith’s position. In their absence, Smith and her attorneys can control the narrative, making it seem as if it’s unreasonable to ask a business that’s open to the public to actually serve all members of the public, she added.

Laser and others, including Colorado officials, claim that a Supreme Court win for Smith could threaten civil rights laws

across the country, making it harder to guard against discrimination based not just on sexual orientation, but also race or religion. Smith’s supporters, on the other hand, say a win for Smith would strengthen everyone’s free speech rights, ensuring that LGBTQ business owners, for example, could control what messages their own products send.

“This case is about whether the government can force artists to say things they don’t believe. In this way, a win for Lorie is a win for all Americans, including those who disagree with her on marriage and other issues,” Warner says.

LIKE THE COLORADO baker case before it, Smith’s case, which is formally known as 303 Creative v. Elenis, involves a

complicated mix of competing protections. In order to declare a winner, judges have had to and will have to determine how to balance a business owner’s rights with a customer’s rights, a conservative religious person’s rights with a gay person’s rights and state-level civil rights laws with the First Amendment.

Since she filed her lawsuit in September 2016, Smith has argued that Colorado currently gets the balance wrong. She claims the state’s public accommodations law, the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act, tramples the free speech and religious freedom rights of business owners, forcing them to choose between following the law and following their beliefs.

“The First Amendment protects people

JUDGES WILL HAVE TO BALANCE A BUSINESS OWNER’S RIGHTS WITH A CUSTOMER’S RIGHTS, A CONSERVATIVE RELIGIOUS PERSON’S RIGHTS WITH A GAY PERSON’S RIGHTS AND STATE CIVIL RIGHTS LAWS WITH THE FIRST AMENDMENT.

like Lorie and people who disagree with Lorie. The government shouldn’t force everyone to say something they don’t believe,” Warner says.

Colorado officials reject Smith’s characterization of the state’s legal landscape, arguing that the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act was not designed to punish or otherwise interfere with the work of business owners. Instead, the goal has been to ensure equal access to the marketplace for members of marginalized communities, including LGBTQ Americans, they say.

“The act requires only that the company sell whatever product or service it offers to all regardless of its customers’ protected characteristics. The act does not, as the company claims, compel a Hindu

“EVERY RULING THAT GRANTS AND VALIDATES A LICENSE TO DISCRIMINATE FURTHER JEOPARDIZES NOT JUST LGBTQ PEOPLE, NOT JUST RELIGIOUS MINORITIES, BUT REALLY ALL OF US.”

calligrapher to ‘write flyers proclaiming “Jesus is Lord.’ ’’ It requires only that if the calligrapher chooses to write such a flyer, they sell it to Christian and Hindu customers alike,” Colorado officials wrote in a Supreme Court brief.

In the lower courts, judges expressed sympathy for Smith’s plight but ultimately ruled against her. They accepted the state of Colorado’s argument that Smith’s free speech and religious freedom rights could be limited in the service of protecting customers from discrimination.

“(Smith’s) free speech and free exercise rights are, of course, compelling. But so too is Colorado’s interest in protecting its citizens from the harms of discrimination. And Colorado cannot defend that interest while also excepting (Smith) from (the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act),” explained the July 2021 ruling from the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Smith appealed to the Supreme Court soon after this ruling was handed down and, in February 2022, the justices agreed to hear her case. The court likely saw 303 Creative v. Elenis as a good opportunity to revisit questions left unanswered in the Colorado baker case, which the Supreme Court ruled on in June 2018. (Phillips won 7-2, but the ruling was narrow in scope and based on the behavior of Colorado officials during legal proceedings.)

DURING ORAL ARGUMENTS in December last year, the justices and attorneys for both sides, as well as for the Biden administration, which joined the case to defend Colorado’s policy, debated a wide range of concerns, as well as a dizzying array of hypothetical scenarios. Some of the key questions raised included whether a wedding website truly represents speech, whether there’s a difference between refusing to sell a wedding website to a gay couple and refusing to serve gay customers at all, and whether it’s possible to rule for Smith without undermining civil rights laws nationwide.

The discussion seemed to confirm more liberal court watchers’ fear that Smith

would have no problem winning the votes of the Supreme Court’s conservative majority. At oral arguments, most of the justices appeared convinced that the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act needed to be adjusted, although they shared no clear solutions for how to update it without opening the door to many more varieties of service refusals.

“Many of the justices were asking the advocates to help them identify lines and limits. It is unlikely that any of the justices believes that public-accommodations laws never implicate First Amendment rights and also unlikely that any of them believes that they always do. What, then, is the principle, factor or consideration that judges and regulators can use to distinguish between impermissible and permissible uses of such laws?” says Richard Garnett, a professor of law at the University of Notre Dame, to the Deseret News in December.

The court’s ruling, which is expected by the end of June, will likely boost protections for business owners like Smith while trying to minimize the possibility of future conflict. But it remains unclear whether such an effort will be successful, or whether the justices are dooming themselves to dozens of future cases centered on the need for further clarification.

Laser is among those who believe the latter outcome is more probable and that a win for Smith will hurt the LGBTQ community and others. Any ruling that allows for customers to be turned away invites more bias, not less, she says.

“Every decision that grants and validates a license to discriminate further jeopardizes not just LGBTQ people, not just religious minorities, but really all of us,” Laser says.

But Warner and others who support Smith’s arguments remain confident that the country’s civil rights framework is not about to collapse. Past lower court rulings in favor of creative professionals who object to same-sex marriage have resolved conflict, not fueled it, Warner says.

“If you look at where this freedom has been upheld, what has been the result? That all artists can thrive,” he says.

At my529, Utah’s official educational savings plan, we help you invest for education so you can help your children and grandchildren achieve their dreams. Contributing even a small amount now to a 529 college savings account can help make college or vocational school more affordable later. my529 benefits include:

• A variety of investment options or you can design your own strategy

• 12 enrollment date options

• 10 static or fixed income options

• Two customizable options

• Earnings are not subject to tax if used for qualified education expenses

• 529 savings can be used at any eligible educational institution in the U.S. or abroad that participates in a federal student financial aid program

• Utah’s my529 is one of only two 529 plans in the nation to receive Morningstar’s Analyst Rating™ of Gold for 2022

Investingisanimportantdecision.Theinvestmentsinyouraccountmayvarywithmarketconditionsand couldlosevalue.CarefullyreadtheProgramDescriptioninitsentiretyformoreinformationandconsiderall investmentobjectives,risks,chargesandexpensesbeforeinvesting.ForacopyoftheProgramDescription, call800.418.2551orvisitmy529.org.Investmentsinmy529arenotinsuredorguaranteedbymy529,the UtahBoardofHigherEducation,theUtahHigherEducationAssistanceAuthorityBoardofDirectors,any otherstateorfederalagency,oranythirdparty.However,FederalDepositInsuranceCorporation(FDIC) insuranceisprovidedfortheFDIC-Insuredinvestmentoption.Inaddition,my529offersinvestmentoptions thatarepartiallyinsuredfortheportionoftherespectiveinvestmentoptionthatincludesFDIC-insured accountsasanunderlyinginvestment.Thestateinwhichyouoryourbeneficiarypaytaxesorlivemayoffer a529planthatprovidesstatetaxorotherbenefits,suchasfinancialaid,scholarshipfundsandprotection fromcreditors,nototherwiseavailabletoyoubyinvestinginmy529.Youshouldconsidersuchbenefits, ifany,beforeinvestinginmy529.my529doesnotprovidelegal,financial,investmentortaxadvice.You shouldconsultyourowntaxorlegaladvisortodeterminetheeffectoffederalandstatetaxlawsonyour particularsituation.AMorningstarAnalystRatingTM fora529collegesavingsplanisnotacreditorriskrating. Analystratingsaresubjectiveinnatureandshouldnotbeusedasthesolebasisforinvestmentdecisions. Morningstardoesnotrepresentitsanalystratingstobeguarantees.PleasevisitMorningstar.comformore informationabouttheanalystratings,aswellasotherMorningstarratingsandfundrankings.

FOR DECADES THE WEST HAS EMBRACED UNCHECKED GROWTH. IS A RECKONING COMING?

BY KYLE DUNPHEY

N APRIL 1890, JOHN WESLEY POWELL STOOD BEFORE A ROOM FULL OF U.S. SENATORS TO DELIVER A MESSAGE AS TIMELESS AS THE LANDSCAPES HE MAPPED. THE 56-YEAR-OLD DIRECTOR OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WAS A MILITARY MAN WHO HAD LIVED A LIFE OF ADVENTURE

unlikely experienced by his audience of well-heeled politicians. The son of English immigrants and a Union Army lieutenant in the Civil War, Powell was the first white man to lead an expedition down the Colorado River. A rugged explorer and the last of an iconic generation of frontiersmen, he sported an unkempt beard that covered his weathered face and was often dotted with ash from his cigars. His right arm was reduced to a stump by a Confederate bullet. He stood only five feet, six inches tall, but commanded the room, speaking slowly and thoughtfully with each word carrying more weight than the last.

Powell was nearing the end of his life, and in his final decade, starting on that spring day in Washington, D.C., he became a counterweight to the prevailing narrative at the time.

The West, he warned, could not sustain the country’s grandiose plans of development and expansion.

“It would be almost a criminal act to go on as we are doing now, and allow thousands and hundreds of thousands of people to establish homes where they cannot maintain themselves,” he told the senators. They were infuriated, and for more than a century after, the federal government ignored his warning.

Now, Powell’s prophecy is coming to pass. The West has been subjected to decades of drought, or depending on who you ask, aridification. The Colorado River, which feeds life to 40 million people and billion-dollar industries, has been reduced to a fraction of its former self. Utah’s Great Salt Lake is shrinking, with large clouds of toxic dust billowing across Salt Lake City in the summer. Wildfires, accelerated by invasive beetles that turn entire forests brown, fill the region with smoke.

All the while, the Mountain West, or the region we at the magazine think of as Deseret, is buckling under explosive growth

in places like Bozeman, Boise and Boulder.

And that is causing a generational sea change in public opinion. For decades, policymakers and business leaders have pushed a no-brakes growth mentality, but according to a new poll conducted by the national polling firm HarrisX and Deseret Magazine, residents are beginning to question that approach and what it has wrought.

“The basic philosophy of westward expansion has been, ‘Look, there’s an unspoiled area – let’s go spoil it,’” says Dan McCool, an author and professor emeritus at the University of Utah who researches public land policy and water resource development. “It’s uncrowded — so let’s make it crowded. It’s clean — well, let’s go make it dirty. There’s no traffic — let’s increase the traffic.”

According to the poll, which surveyed 1,764 adults in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming and eastern Oregon and Washington, only one-third of respondents say they approve of how their elected officials are managing population growth, while half disapprove. And about 60 percent think their state’s economic trends are harming residents — a sentiment held by 69 percent of rural respondents.

In Utah, nearly half of respondents have considered moving to a different state because of housing prices, and across the region, the majority say their state is growing too quickly.

Encouraging growth and expansion, which in turn strain resources, are an affront to what Aaron Weiss calls the “Western way of life.”

“It’s different from life on the California

coast or the East Coast, or Florida. And holding on to that Western way of life, that Western identity, is really important to people,” says Weiss, the deputy director of the Center for Western Priorities based in Denver. And growth is only one half of a double-threat. “Folks are suddenly recognizing that climate change is in fact, an existential threat to the Western way of life,” Weiss adds.

Still, politicians of all stripes see the region’s growing population and economy as a byproduct of good policy and foresight.

When Utah Republican Gov. Spencer Cox was recently asked if his state is too developer friendly, he pushed back. “We need development,” he said. “Like, there is no other way.”

But the Deseret Magazine survey identifies a disconnect between policymakers and voters. It found 68 percent of Westerners say they prefer to protect land and water from development, even if that hampers economic growth.

“It’s still basically the political third

“THE BASIC PHILOSOPHY OF WESTWARD EXPANSION HAS BEEN, ‘LOOK, THERE’S AN UNSPOILED AREA —LET’S GO SPOIL IT. IT’S UNCROWDED — SO LET’S MAKE IT CROWDED.”

rail to say growth is not good,” says McCool. Even if that growth is completely at odds with issues like water conservation, which according to the poll, is increasingly top of mind.

About 80 percent of respondents say water supply is of primary concern, a sentiment heightened in arid states like Utah and Arizona. Roughly the same percentage of people surveyed think access to water will continue to be an issue in 2030. Over 30 percent say Lake Powell — the nation’s second largest reservoir created by a dam along the Colorado River — should be drained. About 40 percent oppose the idea, and 30 percent aren’t sure.

“That shows that folks are very aware that climate change and drought are huge problems in the West,” Weiss says, “and there’s obviously an awareness of that across parties, across demographic

groups, across urban and rural areas.”

It’s hard to ignore the drought when you turn on your faucet and no water comes out, which happened to residents near Scottsdale, Arizona, in January; or when a dire forecast warns that the Great Salt Lake could vanish in five years, according to a recent report; or when 500 homes are destroyed and 30,000 people are evacuated during an unprecedented December wildfire in Colorado.

So, how should policymakers respond? In a free-market economy, government is reluctant to put the brakes on growth, as McCool points out, “but we could certainly stop subsidizing it.”

“If a company wants to come here and says ‘we need a million gallons of water,’ the response should be ‘you’re going to have to pay to conserve a million gallons of water someplace else,” he says.

3 in 5 Westerners believe agricultural uses of water should take priority during drought.

DRAINING LAKE POWELL INTO LAKE MEAD AND NEARLY 40% OPPOSE THE IDEA. NEVADANS HAVE THE STRONGEST SUPPORT AND UTAHNS THE WEAKEST SUPPORT FOR THE PROPOSAL.

That message could have come from Powell himself. Given his hard line at the time, one wonders if the legendary explorer would have been surprised that the West’s unfettered growth has continued to this point without utter destruction. Powell’s warnings drew the ire of Congress, who after his testimony in 1890 slashed funding for his work and continued to promote new settlements in the West.

Powell was disheartened, but persisted. In 1893, he spoke at a conference in Los Angeles, with a perspective that remains timeless.

“There is not enough water to irrigate all the lands,” he said. “It is not right to speak about the area of the public domain in terms of acres that extend over the land, but in terms of acres that can be supplied with water.”

OF WESTERNERS PREFER TO PROTECT LAND AND WATER FROM DEVELOPMENT, EVEN IF IT HAMPERS ECONOMIC GROWTH.

Believe affordable housing in their communities is a problem

Voters are split on whether the federal government owns too much or just enough land in the West, with very few saying it should own more

NEARLY 3 IN 5 WESTERNERS BELIEVE THEIR STATE’S POPULATION IS GROWING TOO QUICKLY

A slight plurality believes the federal government is spending too little on conserving natural resources, led by 47% of Democrats

Water rights is a top 10 state level issue among Westerners

and 4/5 Democrats believe

Nearly half of Westerners want less development in their local area, while the remainder are split between wanting more development or keeping the current rate

CLIMATE CHANGE PLAYED SOME ROLE IN THE CURRENT DROUGHT

SURVEY AREA INCLUDES : ARIZONA, COLORADO, IDAHO, MONTANA, NEVADA, NEW MEXICO, UTAH, WYOMING, AND EASTERN OREGON AND WASHINGTON.

ARIZONA AND WYOMING RANK HIGHLY FOR AFFORDABILITY; COLORADO AND MONTANA RANK HIGHLY FOR NATURAL BEAUTY.

COLORADO AND ARIZONA ARE HIGHLY REGARDED IN MANY ASPECTS OF QUALITY OF LIFE.

SURVEY METHODOLOGY:

This survey was conducted online by HarrisX between December 15-22, 2022, among 1,764 adults. The sampling margin of error is +/- 2.3 percentage points.

A FORMER REFUGEE IS REDEFINING WHAT IT MEANS TO BE A NEW CITIZEN OF THE WEST

civil war erupted in 1991, Aden Batar was in his early 20s and married. He’d just finished law school; he and his wife had recently welcomed a baby boy. Overnight, everything changed. “The government collapsed, all the infrastructure was gone, the running water, the electricity,” he says, recalling the earliest days of the conflict that led to the death of more than half a million

Somalians. “There was no place to buy food … everything was in chaos.”

In addition to a wife and baby to provide for, Batar was also caring for his widowed mother and elderly grandparents. For almost two years, survival meant staying in motion. He and his family would move to one part of the country, thinking it was safer, only for the war to spread to that area — forcing them to flee again. Though the war would eventually lead to the displacement of over two million people, there were no services for the internally displaced at that time.

At first, emigrating was unimaginable to Batar. His hometown of Baidoa was known as janaay in Somali — just a letter off from the original Arabic jannah, meaning heaven. Baidoa was lush, spotted with waterfalls, the towers of mosques pointing like fingers towards the sky.

He’d grown up there among a large extended family of aunts and uncles and nieces and nephews and cousins, passing the days playing soccer with his friends.

But then, amid all the moving, Batar’s two-year-old son was injured, burned by an accident in an overcrowded home. “There was nothing we could do to save him,” Batar says. “There was no adequate medical care at the time. None of the hospitals were functioning; they were only taking care of wounds and so forth. He only survived about a week.”

After standing over his son’s grave, he knew it was time to leave Somalia.

Concerned that he, his wife and their second son — Jamal, a baby boy just a few months old — wouldn’t survive the journey, Batar told his wife, “Let me try the road to see what it looks like. And if you don’t hear

REFUGEES FIND A SYMPATHETIC EAR IN BATAR, WHO KNOWS FIRSTHAND HOW EMIGRATION CAN BE LIKE A SORT OF DEATH, HOW IT OFTEN MEANS GIVING UP A LANGUAGE, A HARD-FOUGHT-FOR EDUCATION, A BUDDING PROFESSIONAL LIFE.

from me, you know that I didn’t make it.” But if he reached safety, he promised his wife, he would get her and their surviving child out of there.

It took him several weeks to make the journey to Kenya. There were military roadblocks and he had to pass through different tribal lands, putting his life in danger, but he knew multiple dialects and pretended to be a local.

He mostly traveled under the cover of night, in part because the weather was so hot. When he finally reached the Kenyan border, he was without any documentation — no ID, no passport, no visa, nothing. But he had hidden money on his body. And so he bribed his way into the country and then rode in on a truck transporting livestock, hiding in the back among the cows.

There, in a town near the border, he found a military radio and sent word back to his wife, who was waiting anxiously at a relative’s home outside Somalia’s capital of Mogadishu, that he was alive.

Once Batar made it to Nairobi, he arranged for a small airplane that was departing from Mogadishu to pluck his wife and their baby son out of the war-town country and bring them to Kenya. “That day was the happiest in my life,” says Batar. “To reunite with my family.”

Two years later, the family was on another plane — this one was headed to Salt Lake City.

THIRTY YEARS LATER and the world continues to struggle with many refugee crises. Somalia, which still grapples with outbreaks of violence, is plagued by drought and hunger; people stream out of the land, which is, itself, home to refugees from

Yemen, other African countries and the internally displaced. The United States’ sudden withdrawal from Afghanistan triggered a governmental and economic collapse that continues to create waves of refugees today. There’s Ukraine, where conflict with Russia has spurred millions to leave. There’s the Rohingya who have been victims of ethnic cleansing in Myanmar.

Since 1975, the United States has opened its doors to over three million refugees. Of those who made their way to the Intermountain West, most ended up in Arizona, Colorado and Utah. Today, Utah is home to approximately 60,000 refugees and the state ranks in the top half nationally for refugee resettlement. But refugee resettlement plummeted under President Donald Trump and Utah’s numbers reflected the national trend. In 2016, the state took in 1,555 refugees; in the four years that followed, just under 2,084 new refugees arrived.

In 2021, the Biden administration raised the national cap on refugees to 125,000. The amount of those who have actually managed to resettle in the United States in recent years, however, falls far below that line. In 2022, the United States took in about 25,000, meaning that 80 percent of the spaces allocated went unaccounted for. Experts say that the Trump administration’s policies decimated the country’s immigration infrastructure and continues to impact our nation’s ability to absorb newcomers. By early 2022, Utah had taken in 900 Afghan refugees. It was estimated that the state would take in about 300 refugees from Ukraine, as well.

All of Utah’s refugees pass through Salt

“HE KNEW WHAT THEY NEEDED BECAUSE HE HAD JUST GONE THROUGH IT. HE KNEW WHAT THEY NEEDED WITHOUT THEM TELLING HIM.”

Lake County, making the area a sort of way station. Many refugees end up congregating in West Valley City or western Salt Lake City where, at Catholic Community Services, they find a sympathetic ear and a helping hand in Batar, who knows firsthand how emigration can be like a sort of death — how leaving one’s country isn’t just about leaving the land and the family that sprung from it. Emigration often means giving up a language, a hard-fought-for education, a budding professional life. It means losing one’s identity. But it also means gaining a new story. Utah wasn’t entirely foreign to Batar. When he was in high school, he’d met some folks from Utah State University who had come to Baidoa to do some agricultural projects with locals. Batar had been studying English at the time and was keen to practice with native speakers; he’d spent some time with the USU crew. So he knew Utah by name. But he was unprepared for

what he saw when he got off the plane: a land so different from his own.

“Luckily, we didn’t come in wintertime,” he jokes today.

That spring, Catholic Community Services helped resettle the family. Case manager Lina Smith remembers the first time she saw him, in a conference room with his extended family, which numbered, she estimates, 17 people.

She could tell he was the backbone of the family, despite his youth (he was still in his 20s) that he was “the leader of the group.” She also noticed immediately a silent strength about him.