THIS IS THE PLACE FOR

We have 11 perfect venues for your event.

YOUR PERFECT EVENT

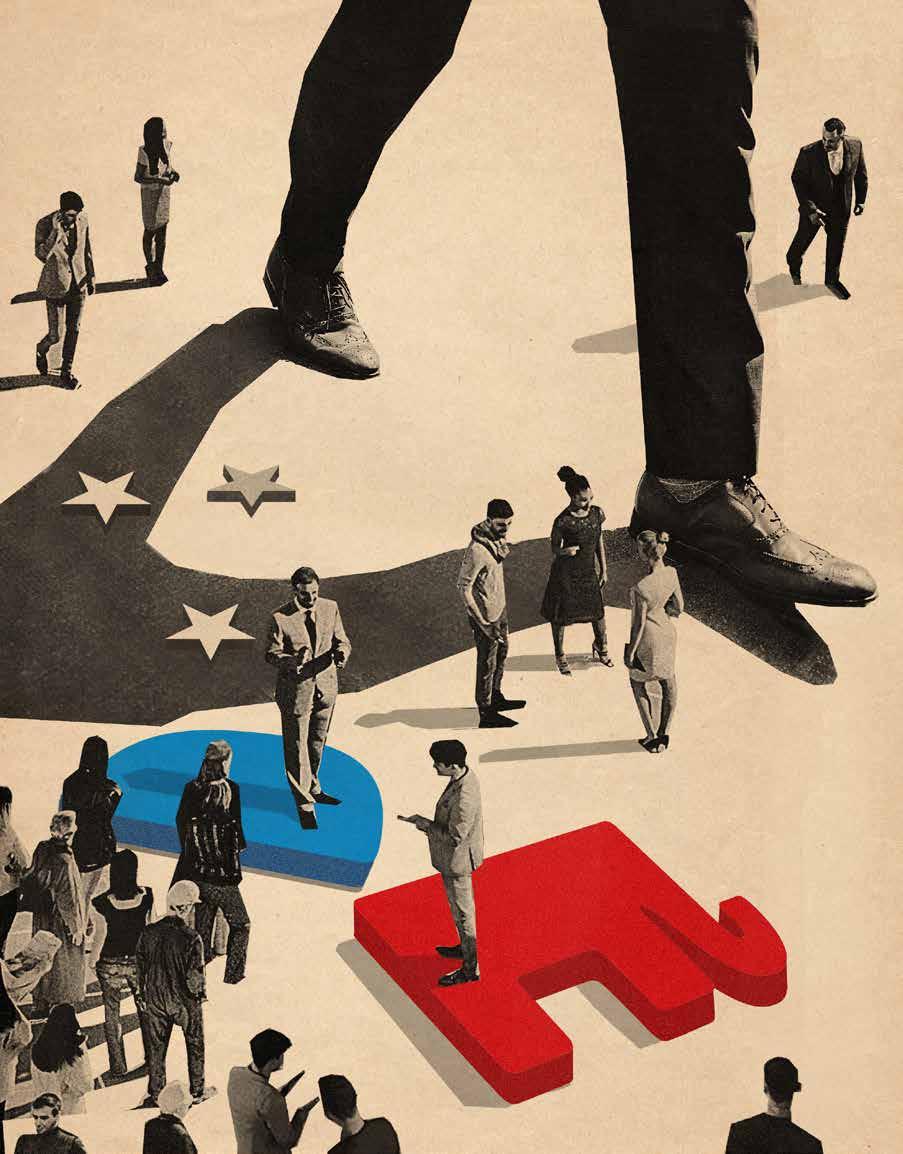

“Trump arrived at a time of dissociation — of unbundling, fracture, disaggregation and dispersal.”

by matthew continetti

by lee m c intyre

THE WAY HOME

by kyle dunphey

“10,000 already die each year due to cold homes and many fear that the rise in energy and food prices could lead to even more excess deaths.”

A QUARTER-LIFE CRISIS

Del Valle is a freelance writer in New York whose work has been published in The Nation, The Verge and The Drift. She has worked at Vice News and Vox and is cofounder of the newsletter Border/ Lines, which focuses on immigration policy. Del Valle’s report on the myth of the Latino vote is on page 26.

Junne is a professor of Africana Studies at the University of Northern Colorado, where he was awarded the Teaching Excellence Award in 2003. Junne is also the recipient of the Champion of Higher Education Award from the Colorado Black Round Table. The author of several books, he tells the story of a haven for Black westerners in Colorado on page 34.

McIntyre is a research fellow at the Center for Philosophy and History of Science at Boston University and former executive director of the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard. A teacher of philosophy, his forthcoming book is “Truth Killers: A Manifesto on How to Fight Disinformation and Protect Democracy.” His essay on Twitter and the fight for free speech is on page 46.

Continetti holds the Patrick and Charlene Neal Chair in American Prosperity at the American Enterprise Institute. A journalist, he was founding editor of the Washington Free Beacon. His work has also appeared in The Atlantic, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. An excerpt from his book, “The Right: The Hundred-Year War for American Conservatism,” is on page 64.

A former national politics and policy writer for the Deseret News, Schulzke is a senior producer at BYU radio and director of The Apollo 13 Project, a program dedicated to prisoner reentry awareness. He’s also working on a book about incarceration policy. His report on the fight against obscenity in Europe and the U.S. is on page 76.

Born and raised in Salt Lake City, Cortez now lives in New York City where she works at HarperCollins. Cortez’s debut poetry collection, “Golden Ax,” was longlisted for the 2022 National Book Award for Poetry. She is also a New York Times bestselling author of “The ABCs of Black History” and “The River Is My Sea.” Her poem “The Idea of Ancestry” is on page 82.

Strautniekas is a conceptual illustrator from Lithuania. A recipient of several awards, Strautniekas’ illustrations have been published by The Washington Post, The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal and Vice — among others. His clients include Air France, Disney, Forbes Japan, GQ France and Penguin Random House. His work is on page 31.

A professor of law and former associate dean at the University of Utah College of Law, Baughman is a nationally recognized expert on bail, prosecutors and police and author of “The Bail Book.” Her work has been featured in The New York Times, National Public Radio and The Wall Street Journal. Her commentary is on page 15.

GABY DEL VALLE

LEE MCINTYRE

RIO CORTEZ

GEORGE H. JUNNE JR.

ERIC SCHULZKE

MATTHEW CONTINETTI

KAROLIS STRAUTNIEKAS

SHIMA BARADARAN BAUGHMAN

OUR READERS RESPOND

For our NOVEMBER cover story (“Bad News”), journalist and American Enterprise Institute senior fellow Chris Stirewalt revealed how the news media is alienating Americans left, right and center. “Read, listen and watch widely,” Stirewalt wrote. “Hear other perspectives than your own. Try on other points of view regularly.” Reader Robert Michaelson added this advice: “Listen to both sides. Take a few days or even weeks to mull over the story (if it is important). Then as stories add up, a lot of things will be easier to see through.” Deborah Farmer Kris, an education journalist and founder of Parenthood365, tackled the myth of multitasking and challenges both children and parents face in paying attention to each other and what’s important (“Age of Distraction”). Commercial airline pilot Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger , who became famous for safely landing a disabled airliner in the Hudson River and was referenced in the article, shared it with his 250k followers on LinkedIn, saying: “Thank you (Kris) for shedding light on why multitasking is a myth, especially in a world of distractions. I highly recommend taking the time to read her piece.” Contributing writer Bethany Mandel pondered the modern family and the trend of gentle parenting (“Spare the Rod, Spoil the Child”), questioning if just acknowledging and challenging a child’s behavior is enough to correct it. Reader Milo Peck reflected, “I didn’t ‘spare the rod’ (not enough, anyway) and my children grew up to be good productive adults. The problem is they still hate me for being strict with them.” With Republicans winning control of the House, President Joe Biden’s second term might be defined by the same impeachment treatment then-President Donald Trump received, reported staff writer Mya Jaradat (“The United States of Impeachment”). Her story on expected oversight and possible impeachment hearings sparked a discussion among readers including Robert Michaelson, who wrote: “If there are official crimes, then so be it. I just don’t want frivolous impeachment occurring every time a new president is elected and the Senate doesn’t match the party of the president.” Political editor Suzanne Bates ’ conversation with Brookings Institute scholar Richard Reeves on the troubles plaguing males (“Of Boys and Men”) sparked a lively reader discussion on the reasons why boys are falling behind girls in education and emotional development, and the consequences for society. Reader Jed Griffin commented, “For more than 100 years feminism has been ‘putting the women forward’ as they say, coming at it from all angles and only now are some starting to wonder why men are falling behind. No great mystery here.”

CORRECTIONS: A story about immigration policy (“The Huddled Masses”) incorrectly stated the number of migrants repulsed by the Remain in Mexico policy. It should be 70,000 migrants, not 700,000 • A story about the West’s role in space exploration (“This is the Space”) misstated the funding and ownership of two Mars-related research programs. The Mars Desert Research Station in Utah receives some funding from NASA for its STEM education program. The story incorrectly said that the station did not receive funding from NASA. The HISEAS program in Hawaii is privately owned and not affiliated with NASA. The story incorrectly reported that HI-SEAS was a NASA program.

“If there are official crimes, then so be it. I just don’t want frivolous impeachment occurring every time a new president is elected.”

MAGAZINE

PRESIDENT & PUBLISHER

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

EDITOR

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

MANAGING EDITOR

DEPUTY EDITOR

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

POLITICS EDITOR

WRITER-AT-LARGE

STAFF WRITERS

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

ART DIRECTOR

DESIGNER

COPY CHIEF

COPY EDITORS

RESEARCH

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS

VICE PRESIDENT MARKETING

HEAD OF SALES

NATIONAL SALES MANAGER

PRODUCTION MANAGER

OPERATIONS MANAGER

ROBIN RITCH

HAL BOYD

JESSE HYDE ERIC GILLETT

MATTHEW BROWN

CHAD NIELSEN

JAMES R. GARDNER

LAUREN STEELE

SUZANNE BATES

MICHAEL J. MOONEY

ETHAN BAUER MYA JARADAT

LOIS M. COLLINS

KELSEY DALLAS JENNIFER GRAHAM ALEXANDRA RAIN GENEVIEVE VAHL

IAN SULLIVAN BRENNA VATERLAUS

CURTIS

DANIEL FRANCISCO

SALLY STEED

CYNDI BROWN

MEGAN DONIO

BRITTANY M C CREADY

Deseret Magazine, Volume 3, Issue 21, ISSN PP324, is published 10 times a year by Deseret News Publishing Co., with double issues in January/ February and July/August. The Deseret News’ principal office is 55 N. 300 West, Ste 500, Salt Lake City, Utah. Subscriptions are $29 a year. To subscribe visit pages.deseret. com/subscribe. Copyright 2023, Deseret News Publishing Co. All rights reserved. Printed in the USA.

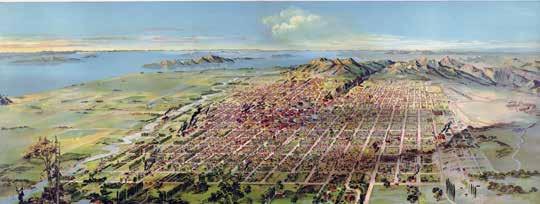

DESERET, proposed as a state in 1849, spanned from the Sierras in California to the Rockies in Colorado, and from the border of Mexico north to Oregon, Idaho and Wyoming. Informed by our heritage and values, Deseret Magazine covers the people and culture of that territory and its intersection with the broader world.

THE CROSSROADS OF THE WEST

Two years ago, in this space, I wrote the first of these columns. I hoped it would serve as an introduction to this magazine and our hopes for what we could do in these pages. We humbly set out to create something worthy of the Deseret brand, a legacy that stretches all the way back to 1849 when William W. Phelps arrived in Salt Lake City with a printing press he’d bought in Boston.

Over the two years I’ve served as editor of this magazine, I’ve thought often of how that printing press arrived here and the dusty trail it traveled. As I wrote in the inaugural issue: “We hope to help readers navigate an increasingly complex world, giving them the information and insights needed to live authentic lives rooted in heritage and values.” Hopefully, we’ve done that since our launch, and we’ll continue to do so.

Good magazines also keep evolving, and to that end we’re adding new departments to the magazine starting with this issue. With The Breakdown we take on a complex, urgent topic and make it more accessible. And with Point/Counterpoint we bring in experts on both sides of contentious issue to help readers understand differing perspectives.

With this month’s issue, we look at affirmative action, which the Supreme Court is set to rule on this year.

We’re also excited about our upcoming slate of events in 2023, beginning with the magazine’s Elevate Summit at Snowbird Resort in March. The summit will gather leaders from government, academia, business and media to discuss the toughest issues facing our society — from climate change to water in the West — and solutions to address them.

As you flip through this issue, we hope you’ll find some of what we promised to deliver when we launched: thoughtful essays on politics, culture and faith, deeply reported narratives and profiles, beautiful art and stunning photography.

But mostly we hope you’ll find a magazine that adds something missing from the national media landscape — a voice rooted in who we are, and where we come from. It’s a view unlike any other, a view from the edge of the Rocky Mountains, a view with the great interior West at our feet, looking out into the world.

TWO VIEWS FROM LINCOLN BEACH, UTAH LAKE PHOTOGRAPHY BY DONOVAN KELLY

A GLOBAL AFFAIRS MEDIA NETWORK

Connecting global publics to leaders in international affairs, diplomacy, social good, technology, business, and more.

Diplomatic Courier’s global network spans 182 countries and five continents. Readers can find us in print, online, mobile, video, and social media.

A FRESH START

DO FAITH-BASED PROGRAMS WORK TO REHABILITATE CRIMINAL OFFENDERS?

BY SHIMA BARADARAN BAUGHMAN

Amanda Allen was born addicted to heroin and alcohol, and became a victim of sex abuse, neglect and domestic violence. She grew up with a drug-addicted mother in Oklahoma who “partied 365 days of the year,” according to the Prison Project. She describes fearing the sun setting and assessing “every new person who came in the room (to) try to figure out who they would molest first — me, my mom or my sister.” Amanda eventually succumbed to addiction herself and was charged with drug conspiracy, resulting in federal prison time. When she was released from prison, she was unable to find a job. She applied for 188 jobs with no success but eventually came across Renée La Montagne Dunn, a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who runs the Prison Project. Dunn volunteered to coach Amanda. Today, Amanda credits the program, and Dunn’s belief in her, with turning her life around. Dunn was motivated by her own faith, and experiences helping a daughter struggling with addiction, to start the Prison Project, which makes faith in a higher power central to recovery. She works with people of diverse faiths, including Muslims, Hindus and Christians, and she says that through her experience in addiction recovery she has found “people are just more successful when they are accountable to their God.”

As a professor, criminal justice expert and a deeply faithful person, I have to admit that realizing the principles that undergird my faith could be a viable solution to the troubles of criminal justice took an embarrassingly long

time. I started my work with inmates in 2006 and have focused much of my scholarship on how improved data, risk assessments, and constitutional and structural reform could fix criminal justice problems. Not until 2021 did I decide that I needed to dedicate more thought and research to showing how faith and religious principles could help reduce crime and incarceration, improve addiction recovery and recidivism and so many other social ills.

The problem is this is not a field of scholarship in criminal law. Faith-based solutions to criminal justice problems is not a specialty of many criminal justice scholars and data on whether these programs work is sparse. Professor Daniel Mears, of Florida State University, and his co-authors pointed out this problem in a piece in the Journal of Criminal Justice: “Precise statistics on faith-based programs in the criminal justice system do not exist, in part because relatively little attention has been given to them by the research community.” Many of my colleagues and other experts are not considering the panoply of tools faith-based approaches offer to vexing social problems like recidivism. A notable exception is that one of the most successful alcohol and drug abuse programs, according to experts, is the 12-step approach (like Alcoholics Anonymous), which is faith-based and requires “surrender to a higher power.”

Meanwhile incarceration and recidivism are endemic in our society. Each U.S. state puts more people in prison per capita than just about any other democratic country in the

world. The latest available U.S. Department of Justice statistics show that in 2005, 83 percent of prisoners released in 30 states were arrested again within nine years, and 44 percent of former inmates let out of prison were arrested within the first year. Given that most crimes go undetected by police, the number of people who are unable to leave a life of crime is even more grim than appears in the recidivism statistics. Even though national crime rates have been at historic lows since 2005 (except for an increase in murders during 2020-21), it does not appear that our criminal justice troubles are going to get better on their own. This might just be the time for divine intervention.

A divine power is what led Joseph Grenny, a New York Times bestselling author of business performance books, to shift gears and dedicate his time and resources to improve the situation of those who have been incarcerated. He has received public acclaim for founding the Other Side Academy, a two-year residential program started in Salt Lake City for people who have hit rock bottom and want to change. The people he invests in are often convicts or have served time, substance abusers or homeless and want to lead a better life. He started this program with a “firm conviction that God wanted it done,” which helped him push past the “tremendous uncertainty” in attempting such a bold program.

Another innovative mentoring program called Inside-Out Network started by Fred Nelson, a former Lutheran pastor, aims to connect the more than 600,000 people exiting prisons each year with the approximately 300,000 religious institutions in America and provides resources in that last period in jail or prison when inmates need assistance. They also help inmates find health care, education, employment and job training. While there are substantial logistical burdens to expanding this program nationwide, he already has 5,000 inmates registered and 375 churches enrolled.

People of faith are making a difference in criminal justice. They are helping to reduce crime, incarceration and recidivism, and demonstrating how we can all make an impact. The divine tools of the faithful are not only fitting solutions for individual problems, but can also be the basis of solving endemic social problems, recidivism and addiction.

A larger institutional focus on using both secular and spiritual tools to aid with these problems could open a new field of scholarly inquiry as well as a solution to inexorable criminal justice problems.

NINTENDONITIS: AMERICA’S DIGITAL ADDICTION

WHY GAMER CULTURE IS STILL EXPLODING, AND WHAT IT MEANS FOR THE FUTURE

BY MARC NIELSEN

We all know a gamer:

The son who boots up his Xbox to play Fortnite after school, or the cousin who spends winter break in her room playing the new Overwatch. Since the 1970s, video games have become a fixture of American culture. And we’re still grappling with what that means. Video games are often designed to keep us hooked. But that doesn’t mean it’s all bad news. Here’s The Breakdown.

HOW BIG IS GAMING?

The gaming industry is booming, projected to surpass $257 billion in revenue in 2023 — up from $91 billion in 2019. That growth is driven by the rise of mobile apps, from Candy Crush to Call of Duty, which in 2021 accounted for more than half of all revenue. More than 214 million Americans play video games, but only about a quarter are children; roughly half are between 18 and 44 years old. About 1 in 10 report playing for 20 or more hours a week, with an average of 13 hours.

NINTENDO THUMB AND MORE

When gamers play for too long, many experience pain or swelling in the thumb, hand or wrist, depending on the controller they use. This is popularly known as nintendonitis, or Nintendo thumb. Excessive gaming has also been linked to attention problems, low self-esteem and poor academic performance, as well as depression — though it’s not clear which comes first.

WHAT’S AN ADDICTION?

There is currently no scientific consensus about video game addiction. But the American Psychiatric Association has classified internet gaming disorder as an unverified potential diagnosis, while the World Health Organization lists “gaming disorder” on its roster of diseases. It’s clear some gamers became obsessed, which is problematic enough. “An obsession is a behavior we become attached to for psychological reasons,” said California psychiatrist David Reiss, an expert in character and personality dynamics. “So attached, that we begin automatically seeking and taking part in the behavior without considering the consequences.”

THE LEVER

In the 1930s, a psychologist named Burrhus Frederic Skinner developed a research tool known as a Skinner Box. Lab rats were placed in a confined space with a lever that dispensed food. He found that if rats were rewarded with a fixed amount of food each time they pressed the lever, they’d soon get bored and quit. But if rewards were dispensed randomly — sometimes none, sometimes a jackpot — the rats couldn’t stop pressing the lever. Slot machines use this psychological tool to keep people playing and so do video games.

CASINOS FOR KIDS?

Loot boxes — virtual “containers” holding randomized rewards like new outfits or powers for a player’s on-screen character — have become a staple in many games. These features, which keep players coming back, can often be purchased using real money. Some contend that this makes some games a form of gambling being marketed to minors. “They are specifically designed

to exploit and manipulate the addictive nature of human psychology,” argues Hawaii state Sen. Chris Lee, a Democrat.

UNDERWATER

Immersiveness, a major selling point in the industry, references how absorbed a player can become within the game. Advertisements often boast of immersive gameplay or game worlds. This is especially true of massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) like World of Warcraft, one of the most popular titles of all time. These games provide a platform where millions of players create their own characters, build friendships with others and create an alternate life within the fantasy world — some would argue at the cost of their own.

CHANGING OUR MINDS

Playing video games can physically change the brain and how it performs. Studies indicate that gaming can increase IQ in children, boost learning capabilities and even improve teamwork in the workplace. Gaming can make those parts of the brain involved in attention function more efficiently, and can increase the size of regions related to visuospatial skills. On the downside, researchers have also found that excessive gaming can cause structural changes to the neural reward system, analogous to those seen in patients with other addictive disorders.

EXCESSIVE GAMING HAS BEEN LINKED TO ATTENTION PROBLEMS, LOW SELF-ESTEEM AND POOR ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE, AS WELL AS DEPRESSION — THOUGH IT’S NOT CLEAR WHICH COMES FIRST.

A SURPRISING ENDORSEMENT

“There are plenty of skills I’ve learned from playing video games. It’s more interactive than watching TV, because there are problems to solve as you’re using your brain.” — Shaun White, three-time Olympic gold medalist in snowboarding.

ROCK ON

“Video games are bad for you? That’s what they said about rock ’n’ roll.” — Shigeru Miyamoto, game director at Nintendo.

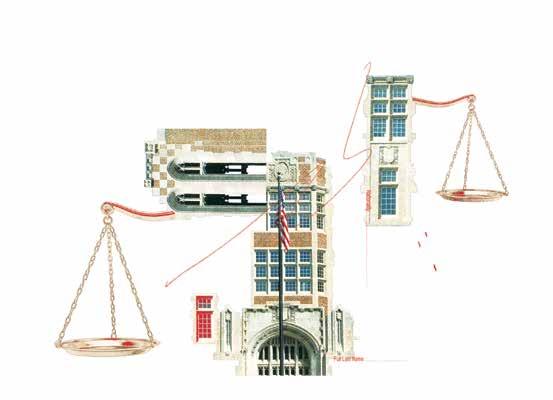

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION ON THE DOCKET

WILL SCOTUS END RACIAL PREFERENCE IN HIGHER ED?

THE SUPREME COURT may be on the verge of ending the consideration of race in college admissions after more than five decades of affirmative action. In two separate cases, plaintiffs suing Harvard and the University of North Carolina argue that favoring minority applicants — ostensibly meant to ensure fair treatment for applicants of all ethnicities — discriminates against Asian American and white students. With a 6-3 conservative majority, the court is expected to rule against both institutions by the end of June, scrapping the practice and potentially altering the face of higher education in America. Here, in order to better understand what is at stake, we consider the issue from the differing perspectives of two experts.

A CASE FOR ENDING AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

I GOT INTO Yale University and then Harvard Law School because of affirmative action. Not only has that improved my professional life, but also, I believe my presence on campus, along with a critical mass of other Black and brown students, was a benefit to the school. We provided an integral part of the education of our white colleagues.

In law school, we read a case about the right to a hearing when welfare benefits are cut off. When the professor asked why this was important, a white woman said it probably wouldn’t make a difference in the outcome, but it would be “fun” for the person who received the benefits. Black students schooled her that there’s nothing fun about pleading with bureaucrats for adequate food and housing. Now, as a professor, I can’t imagine teaching stop and frisk without Black male students to say what it’s like to experience that humiliation in the real world. The Supreme Court’s forthcoming decision will likely have immediate and catastrophic consequences. Public and private universities will resegregate. Black and brown students will no longer be present in substantial numbers at selective predominantly white institutions. Every time my students of color step into a classroom, they demonstrate their extraordinary abilities. When they are no longer present, the connotation is that they are not as capable — one of the insidious lies behind white supremacy. ADAPTED FROM A COLUMN BY PAUL BUTLER IN THE WASHINGTON POST. A FORMER FEDERAL PROSECUTOR, HE IS ALSO THE ALBERT BRICK PROFESSOR IN LAW AT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, A LEGAL ANALYST ON MSNBC, AND AUTHOR OF “LET’S GET FREE: A HIP-HOP THEORY OF JUSTICE” AND “CHOKEHOLD: POLICING BLACK MEN.” HE IS A PAST BENNETT BOSKEY VISITING PROFESSOR AT HARVARD LAW SCHOOL.

THE DIRTY SECRET is that racial preferences provide cover for an admissions system that mostly benefits the wealthy. The current framework is broadly unpopular, highly vulnerable to legal challenges under federal civil rights laws, disproportionately helps upper-middle-class students of color and pits working-class people of different races against one another. Yet major universities cling to the status quo because it is easier financially. They act as if this is the only way to promote racial diversity, but that simply isn’t true. It’s just better for them.

By zeroing in on economically disadvantaged students, affirmativeaction programs could still address the effects of slavery, segregation and redlining. The wealth gap between Black and white households, accumulated over generations, is enormous. White workers typically earn 1.6 times as much as Black workers, but their household wealth is eight times higher. Housing discrimination has put middle-class Black families in neighborhoods with higher poverty rates than low-income white families. Using data on factors like these, admissions committees can identify students who succeed academically despite difficult odds. They’re disproportionately likely to be Black or Latino, but admissions policies need not take account of their race.

ADAPTED FROM “THE AFFIRMATIVE ACTION THAT COLLEGES REALLY NEED,” BY RICHARD D. KAHLENBERG, IN THE ATLANTIC. KAHLENBERG IS AN EXPERT WITNESS ON RACE-NEUTRAL ALTERNATIVES FOR STUDENTS FOR FAIR ADMISSION IN ITS LAWSUIT AGAINST HARVARD COLLEGE, AUTHOR OF “THE REMEDY: CLASS, RACE, AND AFFIRMATIVE ACTION,” AND EDITOR OF “THE FUTURE OF AFFIRMATIVE ACTION.”

AN ARGUMENT FOR RACIAL PREFERENCE

THE TRANSLATOR

IRAN AND THE POWER OF PROTEST

A CONVERSATION WITH REZA ASLAN

BY DOUG WILKS

Reza Aslan has the comfortable look of a man who knows who he is after years of personal reflection.

He is not a prophet. Yet some readers of his works hail him as a hero to true believers in God for his acceptance of faith as a universal part of life. He is not a scientist. Yet some readers offer him as a champion of the atheist, responding to the decidedly temporal parts of his bestselling book on the life of Jesus Christ, “Zealot.” Both “sides” seem to wish he would go further in supporting them. But he’s the person in the middle seeing purpose in the arguments for faith and reason.

“I suppose if I were to describe myself, I would say that I’m a public intellectual. What I want to do and what I’ve always wanted to do is to take what are sometimes complex and messy ideas, be they in politics or religion or what have you, and to try to simplify them to figure out a way to communicate these things in an accessible but also entertaining way, in order to draw as many people as possible into the conversation.”

Eight years ago he did a takedown of liberal comedian and commentator Bill Maher’s condemnation of Islamic violence and oppression, noting its use as a representation of global Islam’s 1.9 billion population is a lazy and inaccurate description. Yet he also lost a CNN show for an offensive tweet, which he apologized for, about President Donald Trump.

Call him an equal opportunity offender, a man that could make your list of the Top

5 People I Want to Invite to Dinner, but be forewarned, dinner conversation here will focus on both politics AND religion, to “take those private conversations, and invite as large an audience as possible into them.”

WE DO A VERY GOOD JOB OF TALKING ABOUT OUR VALUES AS A NATION. BUT WHEN IT COMES TO PUTTING THOSE VALUES INTO PLAY THERE IS AN ENORMOUS DISCONNECT.

Deseret Magazine sat down with Aslan, whose newest work, “An American Martyr in Persia,” details the life and death of Howard Baskerville, who went to Persia (modern-day Iran) in 1907 and ended up joining in a democratic revolution. Its echoes are felt today. We discussed Iran and the religious impulse he believes exists in all of us.

YOU’VE SAID POLITICS IS ABOUT STORYTELLING. WHAT IS THE STORY IN IRAN FOLLOWING THE DEATH OF 22-YEAR-OLD MAHSA AMINI?

It’s important to understand that this is a

100-year-old story; that the fight for freedom we are seeing in Iran right now goes back to the very dawn of the 20th century. Iran has had three major revolutions in the course of the 20th century. I am one of a number of people who truly believe that this uprising that’s taking place right now has the potential to become the fourth revolution. And while in some ways, this can be a tragedy of a story — because here we are, you know, a hundred-and-something years into this, and Iranians are still asking for the most basic, fundamental human rights, which can be quite depressing when you think about it. But it’s also, I think, an uplifting story, because what we are seeing now is a new generation of Iranians, kids, really teenagers, who don’t carry with them the same burdens and the same fears of their parents’ generations, and so cannot be bought off with a little bit of freedom, with a little bit of extra space to make themselves heard.

ARE THERE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THIS AND THE ARAB SPRING?

The big difference, I think, between Iran and a lot of the Arab countries surrounding it is that Iran has had a vibrant protest culture. For more than a century, Iran has had a representative government, even if it is under the Islamic Republic. And for the last four decades, there have been opportunities for the people to voice their opinions and their ideas through the electoral process. Are those free and fair

elections? No. But they do have a variety of choices in candidates that represent a fairly broad spectrum with different views about what the country should be like. And so over the last four decades, we have seen the Iranian people be very politically active and use the tools of government that are at their disposal, limited as they may be, in order to make their voices heard. So as you rightly point out, the difference between, say, the collapse of the government in Egypt, and the collapse of the government in Iran is that there was really no real history or experience of representative government in Egypt. Whereas the opposite is true in Iran, that it is, I would say, probably the most robust political culture in the Middle East, despite the fact that it exists in this incredibly repressive, autocratic government.

AS YOU NOTE IN “AN AMERICAN MARTYR IN PERSIA,” HOWARD BASKERVILLE SAID THAT “THE ONLY DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ME AND THESE PEOPLE IS MY BIRTHPLACE.” IS THERE A REPEAT OF THIS RIGHT NOW IN IRAN?

The constitutional revolution that Baskerville fought and died in succeeded, primarily because it got the attention of the world. It succeeded precisely because revolutionaries from Russia and Georgia and Armenia and Turkey all came and joined in this fight for another country’s freedom. It succeeded because there was a

multifaith, multiethnic coalition that fought under this single umbrella of freedom from tyranny, represented by the Shah of Iran. And of course among that coalition was this one American. And I really think there is a lesson to be learned from that success when looking at what’s happening right now in Iran. Obviously, nobody is asking for armed fighters to go and infiltrate the borders of Iran and fight alongside these revolutionaries. That’s obviously not in the cards. But I really do believe that this isn’t just rhetoric that we have a more powerful weapon than guns, that we have the ability to make sure that the atrocities that are being committed by the Iranian government against these innocent protesters are seen, that they are responded to and that the call for freedom of these young people is heard.

WHAT IS AMERICA’S RESPONSIBILITY THERE?

I think that our responsibility is twofold. On the one hand, we’ve had a very pernicious influence in Iran going back to the CIA coup in 1953. Because it was in our foreign policy and economic interests, we supported the dictatorship of the shah for decades, and so we bear a good measure of responsibility for the shah’s atrocities. Since the ’79 revolution, we have had a fairly consistent policy in the United

States of blanket sanctions of containment and isolation, as a means of trying to change the government, or at the very least force them to change their behavior, or even to promote their downfall. That, of course, has not happened. Quite the contrary, I would argue that our policy towards Iran has done nothing more than entrench that government in place even further. So then, if you are saying, in a very literal sense, what is our responsibility? Well, we’ve had a pretty big role in getting Iran to the place that it is today. And so one can say we should also be responsible in helping Iranians get out of the horrific situation in which they find themselves. But let’s talk about it in more global terms, more spiritual terms, if you will. What is the responsibility that we have, as citizens of a free country, to promote those same kinds of freedoms in places around the world where they don’t exist? Is that a responsibility not just of our government, but of our citizens? Do we have a moral responsibility? Is it really true that the suffering of any one person anywhere is the responsibility of all peoples everywhere?

DO YOU HAVE AN ANSWER?

My answer is yes. We do have an individual moral responsibility. What I would say about our culture, though in our nation, is that we talk the talk. We do a very good job of talking about our values as a nation and the things that we hold dear. But every high school student knows that when it comes to actually putting those values into play as we pursue our fuller foreign policy interests, that there is an enormous disconnect. And I think that that has oftentimes come back to bite us in exchange for some short-term policy gain, which has resulted in devastating long-term consequences.

YOU WENT FROM “ZEALOT” ABOUT THE LIFE OF JESUS CHRIST, TO “GOD, A HUMAN HISTORY.” WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED ABOUT FAITH, AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO RELIGION?

First of all, I have always been animated by stories of people who put their faith into practice, and often do so at great harm to themselves in an attempt to help other people. Whether that story happens in contemporary times, or whether it’s in ancient times, it’s a really powerful story for me, and it’s always drawn me in.

As a person of faith, I’ve spent a lot of time

IRANIAN PROTESTERS SET THEIR SCARVES ON FIRE WHILE MARCHING DOWN A STREET ON OCTOBER 1, 2022, IN TEHRAN, IRAN.

studying not just what faith is, but where it comes from and why it exists. Religion is a manmade institution, the purpose of which is to provide a kind of language, a language of symbols and metaphors, to talk about this mysterious, ineffable individual experience that we refer to as faith. It exists in all people, in all cultures, in all parts of the world, and it has existed for all of our recorded history. And, indeed, the archaeological and material evidence indicates that whatever their religious impulse is, it has existed in species that predate ours. And so the only logical conclusion is that a religious impulse is part of our evolution.

WHAT ABOUT SOMEONE WHO BELIEVES THERE IS A GOD WHO CREATED MAN? ARE YOU IN CONFLICT WITH THAT CONCEPT?

The question of is there a God or not is to me an utterly irrelevant question, because it is absolutely unanswerable. There is no answer to that question. So what can we answer? What we can answer is that whatever this impulse is, towards belief in and let’s just use the word God, even though that word is quite a variable, whatever that is, we can answer with some clarity, that it is part of our evolution, that it is embedded in our cognitive processes, and that we are born with that idea, that belief.

The question then is why and that’s when it becomes no longer a scientific question. At that moment, it’s a faith question. Science doesn’t have the answer. I should say, science has come up with some pretty compelling answers. Again, just as unprovable as any theological answer, the consensus view of why it is that this is a part of our human evolution is that it was an evolutionary accident, that the reason that the faith impulse is universal is that it is really just a byproduct, an echo, if you will, to have some other cognitive processes that we needed early in our evolution in order to adapt and to survive. And my answer to that is, that is as fine an answer, and as provable an answer as well, because there is a God, and God made us to be like this. What is not in dispute? And this is what I find the most fascinating. What is not a dispute, is that we are made this way. Our brains are meant to yearn for this transcendent experience. That’s how our brains work. One side says, “Yes, but it’s irrelevant, it’s just an accident.” And one side says, “It’s because we were made that way.” But both sides agree

that this is a part of who you are, that that faith is who we are as human beings.

I LOVE THE CONCEPT OF A UNIVERSAL RELIGIOUS IMPULSE. CAN YOU EXPLORE THAT?

What we know from the admittedly very recent surveys and data that has been collected, is that human beings are born with the capacity for what is sometimes referred to as substance dualism, which is the belief that the mind and the body are separate and distinct. And by the way, you can replace the word mind with soul if you want to. You can call it chi if you want to. You can call it, you know, prana. You can call it Buddha nature. Everybody has a different word for it. But fundamentally, what is meant is that whatever it is that we are is more than just the material self, that there is an eternal essence that is distinct from our bodily form.

WE HAVE A MORE POWERFUL WEAPON THAN GUNS; WE HAVE THE ABILITY TO MAKE SURE THAT THE ATROCITIES THAT ARE BEING COMMITTED BY THE IRANIAN GOVERNMENT AGAINST THESE INNOCENT PROTESTERS ARE SEEN.

impulse is so that when I look at you, I think to myself, you have the same basic shape as I do. So therefore, you must have the same internal essence as I do. So therefore, we must feel the same. Therefore, we must be the same. And that can act as an adaptive advantage, you know, in our evolution.

IS THAT THE LESSON OF HOWARD BASKERVILLE?

Absolutely. Here’s a kid who was told that you are distinct because you’re American, you’re distinct because you’re a Christian. That makes you separate from the Persians. It makes you separate from the Muslims. And yet at the end of his life, he came to this realization that there isn’t anything that separates him from these people that he is fighting. The way they express their faith, their nationality, their ethnicity, their language — these are all external and meaningless. The fundamental aspiration of being a human is the same regardless of those things and that is precisely what allowed him to abandon all those other markers of his identity and to join with people who were “not him,” and fight in their cause.

SO IF THAT’S THE LESSON OF HOWARD BASKERVILLE, WHAT’S THE LESSON OF REZA ASLAN?

What then, what does that lead to? How does that change the way that we see ourselves in relation to the world or in relation to each other? It is interesting when you think about it, if you believe that you are more than just the sum of your material self, then it’s not that hard to believe that what I feel as my internal essence is similar to your internal essence. And so maybe our bodily forms are different, maybe our place of birth is different, but internally we’re the same. And from the perspective of evolutionary biology the reason we have this

I’ve spent my life trying to learn the languages of religion of the world, so that I can become kind of a universal translator if you will. If I do define religion as just a language of symbols and metaphors, I do truly believe that if I can become fluent in all of those languages I can help people understand that fundamentally, they’re saying the same thing to each other. And I’ve built a career on that hope. It hasn’t always worked. There have been ups and downs. There’s been successes and failures. But I do believe that if we can as a human species, take the lesson of Baskerville, take the lesson of what I’m saying as the translator and to recognize the similarities that we have with each other beyond the sort of external divisions, borders and boundaries and skin color and any churches or what have you, then that’s the kind of world that I would like to live in. And it’s the kind of world that I’m trying to create for my children.

DOUG WILKS IS EXECUTIVE EDITOR OF THE DESERET NEWS.

Visit the World’s Best Backyard

Nestled among the red rock mountains of Cedar City, Southern Utah University is positioned in one of the world’s most beautiful natural settings, with plenty to do on and around campus!

Southern Utah Museum of Art

The Southern Utah Museum of Art is the sculpture housing an art museum you don’t want to miss.

Utah Shakespeare Festival

Tony Award-winning productions are a must-see at the Utah Shakespeare Festival each summer.

Athletics

Cheer for the red and white of our fighting SUU at one of 15 athletic team events.

National Parks

SUU is within a five-hour drive of more than 20 national parks and monuments, so explore the world at the University of the Parks®️.

Beautiful 125-Year-Old Campus

From events and concerts to art strolls and local festivals, there is always something to do in Cedar City.

A QUARTER-LIFE CRISIS

WHAT TO KNOW ABOUT NOT KNOWING ANYTHING

TI love my job, but there are parts about it that, in diplomatic terms, present opportunities to practice patience. I love my wife far more, but we still have arguments. I love living with her in a cool place like Utah, but I miss my family and friends back home in Florida. In short, there’s always some missing part that can never be made whole. At first, I rebelled against that reality. I told myself it was just a matter of time until we move back to Florida and I get a new job that will have all the things I like about my current one with none of the strings attached.

It’s worth noting that, for all these gripes about aging and adulthood, I’m not 50. Or 45. Or even 35. And as any actual middle-age or elderly person is surely screaming in their head, if not out loud, one among many pieces of wisdom I hadn’t learned until recently is that there will always be friction. No job is perfect. Every city or town has its charms and drawbacks. Every relationship faces difficult moments. And once I realized that, the question became whether my (relatively blind) ambitions were still worth pursuing — and whether I could really put them aside if I chose to.

BY ETHAN BAUER

“quarter-life crisis.” This phenomenon is not a psychological diagnosis or syndrome; you will not find an entry for it in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. But psychologists (and 25-year-olds) have been thinking (and half-joking) about it, to different degrees and under different names, since the mid-20th century. Even longer, actually, if you understand it not as a condition, but as a near-universal experience. “The drives and desires of people are always the same,” says Tess Brigham, a San Francisco-based therapist

“WE ALWAYS JUST WANT TO FEEL LIKE WE’RE ENOUGH.” WHETHER IN OUR RELATIONSHIPS, IN OUR CAREERS, OR JUST IN GENERAL — IN LIFE.

There’s a temptation, because of its associations with its more-familiar cousin (the midlife crisis), to define the quarter-life crisis in rigid terms; to make it about a realization that you here was a moment — I can’t pinpoint the time — when I remember feeling pretty good about my place in the world and confident about my adulthood. I thought I had everything figured out. I thought everything would be smooth sailing ahead. But it hasn’t been.

This is my personal manifestation of a

whose work with young people inspired her to write a book about launching 20-somethings into adulthood. “We always just want to feel like we’re enough.” Whether in our relationships, in our careers, or just in general — in life.

haven’t found the right partner yet and need to work on settling down, or that you’re not progressing in your career as quickly or as easily as you’d hoped. But the modern understanding of the quarter-life crisis has more breadth. It’s the moment a person truly reaches adulthood. Not in the way that you’d expect — like a biological way or a social, moved-out-of-mom’shouse sort of way. But in a “no matter what I do or where I go, or how much money I make or how many friends I have, nothing will ever be perfect, adulthood will never be as simple as I thought it would be” way. Every human one day realizes, whether consciously or not, that the life ahead of them will be very different from the life behind them; where they must figure out, Brigham says, “what life really is.”

Erik Erikson, a father of developmental psychology, first formalized something resembling the quarter-life crisis in 1950. His acclaimed book, “Childhood and Society,” hypothesized eight “stages of psychosocial development,” with each stage carrying the weight of a specific developmental “crisis.” Two of these stages — adolescence (11 to 19) and early adulthood (20 to 44) — result in questions (and crises) of “Who am I?” and “Can I love?” respectively. But the world has changed since 1950. The average American life expectancy has grown by about 10 years, leading psychologists to identify a new stage of development known as “emerging adulthood.” During this stage, “You’re not quite there yet,” explains Kent State child psychologist and researcher Angela Neal-Barnett, “but you should be

working your way to adulthood.” Gestalt psychologists, who approach people as the sum of their parts rather than as a collection of individual pieces, label the resulting friction an “existential crisis” rather than a quarter-life crisis, but for us laypeople, the differences are negligible. The animating question in both cases is the same: “Who am I,” Neal-Barnett says, “and what does it mean to be an adult?”

Amid housing crises, a recession and a culture defined by the internet, what it means to be an adult means something different than it did in 1950 — but the definition still seems elusive and personal. Achievement? Maturity? Independence? Neal-Barnett makes the point that everyone must confront the question. She uses my wife, who is studying to become a psychologist, as an example. She described my wife’s attitude as follows: “When I get my Ph.D., then I’ll start my life.” I’ve certainly noticed that sentiment, at least sometimes.

Brigham had a similar realization in her 20s. Since she was a teenager, she’d hoped to one day work in Hollywood. She got her first job in Los Angeles by 24, and by 27, she was “primed” for exactly the life she’d once hoped for — except she realized she was miserable. So she quit and moved back to her hometown to reinvent herself and chart a new path into adulthood. She didn’t identify her experience as a quarter-life crisis until later, when she opened her therapy practice about 10 years ago. Her clientele included many 25to 30-year-old millennials who were showing up in her office directionless. They felt like they’d followed the approved script — college, marriage, professional careers — but still felt relentlessly unfulfilled. They weren’t quite the same as her own experience, but she noticed an echo. Which is why she believes it’s somewhat futile to neatly define a quarter-life crisis, except to say that it’s a point where emerging

adults begin to question their long-held beliefs and core truths. “What’s unique about the quarter-life crisis is that our brains don’t fully form until we’re 25, but we pick a major (or a career) at 18,” she says. “And you don’t know yet what it is to be an adult.” You don’t know about what David Foster Wallace described as “whole, large parts of adult American life that nobody talks about in commencement speeches,” including “boredom, routine and petty frustration.”

Brigham hypothesizes that our atomized existences are to blame. “There’s no time anymore,” she explains. “We don’t daydream. We never process our thoughts.” The minefield of distraction we face from our phones, from television and from social media makes asking big questions harder, so when they surface — as they inevitably will — we aren’t wellequipped to answer. We avoid them more than ever. But those questions, she says, define what it means to be 20-something in the 21st century more than any traditional barometers of success; more than getting married and buying a house and having kids. “The point (of your 20s) is to learn about yourself,” she says. “To try things. To explore. To really learn about yourself. And if you do that, I can’t tell you for sure you’ll never have a quarter-life crisis, but you won’t hit these walls.”

My wall arrived in the form of questioning success. I’m a lucky man indeed, living in an era that despite its many problems and injustices still ranks among the greatest periods of widespread flourishing in human history. And yet I still find myself falling back on a sort of mindless ambition as my default, even if that’s not what makes me the happiest version of myself. Maybe being “normal” really is what makes me happiest. There’s a freedom in acknowledging that. But there’s also a nagging sense that freedom is hindered by complacency. So I find myself again at the central question rooting my personal quarter-life crisis: What does success mean to me, and should it perhaps mean something different? Luckily, some psychological experts have reminded me that a quarter-life crisis isn’t necessarily about answering that question and others like it; it’s about acknowledging their presence. About realizing that you may not know who you are and what you’re about just yet — you may never know! — but it’s best to discover who and what you are not. About asking yourself honestly, as you enter the adult world and confront all its paradoxes and complexities, how you want to exist.

Maybe it will be simpler in the years to come. Maybe not. All I know is that knowing isn’t as simple as my younger self thought it was.

THE MYTH OF THE LATINO VOTE

SOUTH TEXAS WAS SUPPOSED TO GO RED. WHAT WENT WRONG?

BY GABY DEL VALLE

On a muggy Saturday afternoon in late October, just weeks before the midterms, 200 or so people gathered in a church auditorium in Weslaco, Texas, to hear from three women they hoped would soon represent them in Congress. Mayra Flores was the last of the trio to speak, and it was clear from the standing ovation she got before taking the stage that she was the main attraction.

Flores greeted her audience in Spanish first, then English. “Buenos dias a todos; good afternoon, everyone,” she beamed. “It’s great to be surrounded by freedom-loving youth,” Flores told the mostly middle-aged audience attending the Texas Youth Summit at the Mid Valley Assembly of God that afternoon. “If you’ve been following the awakening that’s been taking place in the RGV (Rio Grande Valley), you know we’re witnessing something special — not just politically, but spiritually.”

Four months earlier, Flores had won a special election in Texas’s 34th District, making her the first Republican to hold the seat in more than a century, the first Mexican-born woman in Congress, and the first Latina Republican to represent Texas in Washington. Now she was fighting to hold on to the seat. Two other Latina Republicans, Cassy Garcia and Monica De La Cruz, were running in the neighboring 28th and 15th districts.

A red wave was coming, Flores predicted, but only if everyone in the room did their

part. “Take your abuelitas, your aunts, tíos, tías, cousins, you name it,” to the polls, Flores urged the audience. “Spread the chisme; spread the gossip. Tell everyone to go vote on Monday — of course, for Mayra Flores — but to vote conservative.”

At the time it seemed like the odds were in their favor; it seemed possible that the histor-

THE THREE WOMEN PROMISED THAT A RED WAVE WAS NOT ONLY ON THE HORIZON, BUT ALSO THAT LATINOS WERE AT THE FOREFRONT OF IT.

ically blue Rio Grande Valley would flip not just one seat, but three. Polls suggested that Flores, who had initially been projected to lose the seat after winning it in a June special election, was catching up to the Democratic candidate. Henry Cuellar, the longtime Democratic incumbent Garcia was hoping to unseat in the 28th District, narrowly managed to defeat a primary challenger by less than 300 votes. The state legislature had redrawn the 15th District, where De La Cruz was running

against a Bernie Sanders-endorsed progressive, to favor Republicans.

Flores, Garcia and De La Cruz called themselves the “triple threat.” The New York Times called them “far-right Latinas” who represented the new face of the Republican party. The three women’s pitch to Texas voters was, essentially, that they were just like them: conservatives who speak their language, both literally and figuratively, who support Border Patrol and the police, who go to church and oppose abortion.

“Dijeron que no íbamos a ganar. Que equivocados estaban,” Flores said at the summit, two days before early voting started in Texas. “They said we weren’t going to win. Oh yeah? We’ll see about that.” Seventeen days later, Flores found her time in Congress short-lived.

For months, the three women promised that a red wave was not only on the horizon, but also that Latinos — specifically, Latina women — were at the forefront of it. Across the country, pundits predicted a Republican sweep, not only in swing districts but also in traditionally blue states like Oregon. It didn’t happen. Flores lost by more than 8 percentage points; Garcia by 13. De La Cruz was the only one to win her race.

“The RED WAVE did not happen,” Flores tweeted four hours after the polls closed in Texas. “Republicans and Independents stayed home. DO NOT COMPLAIN ABOUT THE RESULTS IF YOU DID NOT DO YOUR PART!”

There have been rumblings of a rightward shift among Latinos for years. Roughly onethird of Latino voters nationwide cast a ballot for Republicans in the 2018 midterms, and Trump made gains among Hispanic voters in 2020 despite his controversial immigration policies. Trump’s gains were especially pronounced in the 34th District, which is 84 percent Hispanic and which President Joe Biden only won by 4 percentage points. But the theory that Latinos will abandon Democrats en masse has yet to come true. Democratic House candidates won 60 percent of the Latino vote in the midterms, according to one CNN exit poll. An estimated 39 percent of Latinos voted for Republicans in House races — an improvement

compared to 2020, when that figure was 36 percent, but a modest one at best.

If a political shift is happening and Latino voters really are embracing the Republican Party, albeit slowly, it’s not entirely the result of an organic awakening. In Florida, a former swing state with a significant Hispanic population, Republicans dominated at nearly every level in the midterms, thanks to a combination of conservative effort — in the form of millions of dollars in spending and gerrymandering — and Democratic apathy. But Cuban and Venezuelan voters in Florida have different political motivations from Mexican-American voters in south Texas, a nuance that’s often left out of predictions

involving a single, unified “Latino vote.”

Republicans didn’t win the “Latino vote” in south Texas, where the overwhelming majority of voters are Mexican American, nor did they turn the Rio Grande Valley red. They did, however, force Democrats to compete in a part of the country where they had previously taken victory as a given.

Emboldened by Trump’s gains in the region in 2020, Republicans started treating south Texas like a battleground rather than a lost cause. Flores helped run Hispanic outreach for the Hidalgo County Republican Party in the lead-up to the 2020 election. She announced her bid to represent the 34th District in February 2021. Eight months later, the Republican National Committee opened a Hispanic “community center” in the border town of McAllen — one of four outreach centers the RNC has opened in Texas since 2021. “One of the things we heard is that they felt they had been abandoned by Democrats,” RNC spokesperson Alex Kuehler told me. “We’re really trying to reach out to folks who we think are disaffected with the Democrat Party.”

Flores didn’t have to wait until the midterms. Filemon Vela, the Democrat who had represented the district for eight years, had announced in 2021 that he would be retiring at the end of his term. Because of redistricting, Vicente Gonzalez, a Democratic incumbent in the neighboring 15th District, would instead run in the 34th against Flores. Instead of waiting out his term, though, Vela abruptly retired in March, triggering a special election — one Flores was prepared for, and which the Democrats were not.

She secured endorsements from Texas Gov. Greg Abbott and Sen. Ted Cruz and raised more than $750,000 in contributions during the special election cycle. Her opponent, Cameron County commissioner Dan Sanchez, raised just $46,000. A few weeks before the election, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and the House Majority PAC spent a combined $215,000 on ads for Sanchez, but it was too late.

Flores beat Sanchez by 7 percentage points — a victory some Democrats downplayed by noting turnout had been low and emphasizing the limited tenure of whoever won the special election. “If Republicans spend money on a seat that is out of their reach in November, great,” Monica Robinson, a spokesperson for the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, told Politico a few weeks before the special election. Local Democrats, however, warned that Flores’ victory signaled the

“THEY’RE CLAIMING THE REPUBLICAN PARTY IS THE ONLY CHRISTIAN PARTY, WHICH IT’S NOT.”

extent to which national Democrats had taken victory in south Texas as a given. “Too many factors were against us, including little to no support from the National Democratic Party and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee,” Sanchez posted on Facebook after conceding.

Part of Flores’ pitch to voters was the notion that Democrats have moved too far to the left, abandoning Latinos in the process — especially in socially conservative south Texas, where voting Democratic was more indicative of tradition than policy preferences. Vila’s resignation and the ensuing special election was an opportunity. Conservatives are building infrastructure in south Texas for the first time. Nikki Haley had a get-out-the-vote rally for Flores and De La Cruz, as did Abbott. “Governor Abbott’s always in the area — he should get an apartment down here,” Javier Villalobos, McAllen’s first Republican mayor, told me.

“They saw the potential and that’s why they’re investing,” Flores told reporters at the October summit. “With funding, we’re able to spread the message throughout the district.”

The message is largely rooted in religion. Before she was a congressional candidate, Flores was a local conservative influencer who claimed Democrats had stolen the 2020 election and posted conspiracy theories about the January 6, 2021, riots and QAnon on Twitter. As a congressional candidate, her message was more tailored to local conservative concerns, like outlawing abortion and supporting Border Patrol families.

The yard signs Flores distributes to supporters are emblazoned with “God, Family, Country” in English on one side and in Spanish on the other. Flores borrowed another slogan of hers — “Make America Godly again” — from Luis Cabrera, a pastor in Harlingen who describes himself as Flores’ “spiritual adviser.” Cabrera has introduced Flores to other pastors, who have in turn encouraged their congregations to get involved politically. Cabrera attributes the recent rightward shift in south Texas to evangelical Christians getting more involved in politics. “We truly believe that in these elections, we’re going to see a Godly wave — not a red wave — a Godly wave of revival,” he told me in October. “We’re waking up. We’re now going to get vocal, we’re now going to hit the streets, we’re going to hit the public square.”

At an Oktoberfest-themed fundraiser for the North Cameron County Democrats,

attendees chafed at the idea that the Republican Party had a monopoly on Christian identity. “They’re claiming the Republican Party is the only Christian party, which it’s not,” Wandy Cruz-Velazquez, a member of the organization, told me. “There’s many people in this room right here that are Christians, and we’re not Republicans.”

Republicans, several attendees at the Oktoberfest fundraiser told me, were targeting Latino voters in the area. One woman showed me a flyer she had received claiming, in Spanish, that “Joe Biden and his leftist allies are indoctrinating your children into thinking biological sex isn’t real.” It had been delivered to everyone with a Spanish-sounding surname, she told me, and was paid for by America First Legal, an advocacy group founded by former Trump adviser Stephen Miller.

In south Texas, Republicans zeroed in on two messages: Democrats are too far to the left and out of touch with local concerns, and they don’t support — nor can they even understand — the hardworking families that make up your community. It’s a message that resonated at the Texas Youth Summit, where the audience groaned after Kayleigh McEnany reminded them of the time first lady Jill Biden said the Latino community is “as unique as the breakfast tacos” in San Antonio (just a few hours later, Garcia referred to herself as the “second spicy taco” onstage to cheers and applause). “I’m their worst nightmare,” Flores said of the Democrats. “I’m pretty sure the Democrat Party is now thinking, ‘Let’s send Mayra back to Mexico.’”

Democrats, Flores and her fellow speakers implied, didn’t care about Latinos — they just wanted their votes. “We’re all about God, family and hard work,” Flores told reporters.

For Sara Hinojosa Parsons, Flores and her allies represented a threat to her family. “I’m a Hispanic woman with a transgender child. It’s do or die,” Hinojosa Parsons told me at the Northern Cameron County Democrats fundraiser. “What I find most offensive is that they think whoever’s not on the right, whoever’s not Republican, we have no claim to the American flag, we have no claim to God and religion, we have no claim to families.” This was the same assumption pundits made when they claimed Latinos would usher in a red wave: that Latinos are inherently conservative, that their politics are shaped by heritage or demography and not personal experience. In the end, the so-called Latino vote was split along ideological lines.

THE DARK NIGHT OF WINTER

WAR IN UKRAINE IS SPARKING AN ENERGY CRISIS ACROSS EUROPE

BY JAMES L. WALKER

On an island off the west coast of Scotland, 64-year-old Caroline Gould faces a brutal winter. Disabled, she uses a powered wheelchair to get around but now struggles to afford the electricity needed to charge it. She has to ration her heating as a consequence.

Her situation is getting increasingly precarious. “I need to keep warm because I can’t exercise to keep warm,” she told the nonprofit 38Degrees. “I can’t even lift a duvet to wrap around me.”

Caroline is one of millions in the U.K. — and across Europe — feeling the brunt of skyrocketing energy prices. This winter, many have to choose between food and heating as the war in Ukraine takes its toll.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has been manipulating oil and natural gas exports to Europe for years. But amid Western sanctions, Russia has suspended much-needed supplies of natural gas, plunging Europe into an energy crisis and threatening to undermine the continent’s climate goals.

The U.K. is no exception, with over 6.7 million people already unable to properly heat their homes during the winter months, according to fuel poverty charity National

Energy Action. And while new U.K. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has reaffirmed the country’s climate commitments, his government — and those across Europe — are scrambling to keep energy prices down and their citizens warm.

EUROPE WAS SWIFT in implementing sanctions against Russia following the invasion of Ukraine in an effort to paralyze the country’s economy. And while the European Union

This is because Europe has become increasingly dependent on Russia to meet its gas needs, made worse by the lifting of Covid-19 restrictions last year, which put huge demands on its depleted stocks. Prior to the war, the EU’s 27 member nations had relied on Russia for 40 percent of their natural gas, mostly from the massive Nord Stream 1 pipeline, which stretches 745 miles under the Baltic Sea from the Russian coast near St. Petersburg to northeastern Germany.

But that flow stopped in September 2022 as Russian state energy giant Gazprom, which operates Nord Stream 1, announced it had detected an oil leak and shut the pipeline completely, giving no timeline of when exports might resume. Russia has now cut its supplies of gas to Europe by 88 percent, with two smaller pipelines still operational. This has led to the price of natural gas in Europe hitting a record high of over 300 euros per megawatt-hour, 10 times higher than the United States at the time.

has sanctioned Russian billionaires and made commitments to phase out Russian coal and oil by the end of the year, they have fallen short of promising the same for gas.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen called the leaks “acts of sabotage” and warned of the “strongest possible response” in the event of an attack on European energy infrastructure. Since, Europe

has remained on guard. Norway, western Europe’s biggest oil and gas producer, has sent troops to guard its energy installations and Italy has stepped up naval surveillance on pipeline routes.

But it’s households in the U.K. that are being hit hardest by the energy crisis, more so than any other country in western Europe, according to the International Monetary Fund. This is despite the country only importing 4 percent of its gas needs from Russia in 2021. Nowadays, it imports none.

This is because the U.K. — like the rest of the world — is not immune to market factors. Russia restricting supplies to mainland Europe has led to acute shortages on the international gas market, with the price of gas in the U.K. increasing by 129.1 percent.

Caroline’s home is among the vast majority in the U.K. — 85 percent — which uses gas to provide heat compared with fewer than 50 percent in France and Germany. The U.K. dwarfs other countries in terms of the share of electricity generated by gas as well, which makes the country disproportionately vulnerable to price hikes as it has traditionally relied on North Sea gas fields, which are now in decline.

The U.K.’s leaky homes are also the least efficient in western Europe, according to one study. “It’s a huge problem,” says Matt Copeland, head of policy and public affairs at National Energy Action, “and the least efficient (and poorest) homes are sometimes paying twice as much.”

With Ofgem, the national energy regulator, predicting that the average annual household bill would rise from 1,000 to 3,500 British pounds in October, the U.K. government introduced costly support to households and businesses, setting a price cap of 2,500 pounds with energy suppliers being fully compensated for any shortfall. The cap will rise to 3,000 pounds a year from next April, however.

Britain’s gas producers and electricity generators could make excess profits of up to 170 billion pounds over the next two years, according to Bloomberg, citing unpublished Treasury analysis. “Energy companies should not be making excessive profits,” says Antony Froggatt, an energy policy expert from policy institute Chatham House, “they should also be paying more tax to help governments support the higher costs of energy

to society as a whole.”

The British government is also giving every household 400 pounds off their energy bills this winter, regardless of circumstances. Critics say this is welcome but not enough, particularly for the poorest families who are also contending with skyrocketing inflation and a cost of living increase across the board.

Copeland expects to see millions of families resorting to desperate measures this winter including barbecuing and burning furniture indoors, only eating cold meals and covering windows with newspaper for extra insulation. He has also heard reports of parents not sending their kids to school because they can’t afford the electricity to wash their uniforms.

EUROPE’S GAS PRICES have fallen since a record high in August, as mild autumn weather decreased demand. Across Europe, the overall

“EUROPE IS SET TO FACE AN EVEN STERNER CHALLENGE NEXT WINTER.”

storage levels are at an average of 95 percent, according to a report from the International Energy Agency, which has fueled some optimism going into the winter.

But this is far from the end of the energy crisis. A lot depends on how much European governments are forced to deplete their gas reserves this winter due to the war in Ukraine. And with a likely decline in Russian pipeline deliveries next year and the risk of them halting completely, IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol warned that “Europe is set to face an even sterner challenge next winter.”

The energy crisis is also calling into question Europe’s climate goals. Faced with widespread blackouts and rationing, some countries have been forced to resort to coal, the most polluting fossil fuel. Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Greece and Hungary plan to extend the lifetime of coal plants

and reopen those that have been closed.

“In the short term, we will be burning more coal,” says Michael Bradshaw, professor of global energy at Warwick Business School, “(and) emissions will be higher than they might have been.” He remains optimistic, however, explaining that “in the longer term, it’s about accelerating the pace of low carbon transition.”

The war in Ukraine has forced Europe’s hand, making renewable energy more enticing from a security perspective but also economically as the price of renewables hits record lows. In May, the European Commission unveiled a new plan, REPowerEU, that aims to mobilize up to 300 billion euros to achieve total independence from Russian fossil fuels before the end of the decade. It also expands the EU’s targets for renewable energy for 2030, from 40 percent to 45 percent of all total energy produced.

But there was a heavy price tag on Europe’s climate agenda even before the events of the past year, casting doubt on how achievable these goals are. “The amounts of money put aside by governments to cushion consumers against this crisis isn’t sustainable,” says Bradshaw, “particularly if it stimulates a recession.”

In the U.K., the situation is more uncertain after Sunak became the country’s third prime minister in three months. Sunak has recommitted to U.K.’s ambition to hit net zero by 2050, but he has fallen short of reversing his predecessor’s decision to ramp up oil and gas drilling in the North Sea under mounting pressure to somehow ease the burden on British households.

But while the U.K. government — and its European equivalents — play a juggling act between easing short-term supply issues and longer-term climate commitments, their most vulnerable citizens are feeling the (lack of) heat.

Caroline is far from the only older Briton set for a cold winter because of a war thousands of miles away. Ten thousand people already die each year due to cold homes and many fear that the rise in energy and food prices could lead to even more excess deaths. The U.K.’s National Health Service has called it a “humanitarian crisis.” At least one health service board is already in talks with funeral directors to ensure cremations and burials can keep pace with demand.

WILFORD W. CLYDE

For 45 years of Building a Better Community

Congratulations! Enjoy your well-deserved retirement!

PROFESSIONAL HIGHLIGHTS

Chairman & CEO, Clyde Companies

President, Associated General Contractors of Utah

President, Vice President, and Board Member, Beavers Inc.

Chairman, Utah Manufacturers Association

Chairman, Salt Lake Chamber of Commerce

Chairman, Utah Valley Chamber of Commerce

COMMUNITY SERVICE

Springville City Mayor (2009-17)

Springville City Council (1989-92)

Utah State Board of Regents

Chairman, Board of Trustees, Utah Valley University

National President, BYU Cougar Club

Founding Member, UVU Wolverine Club

Co-Chair, Springville Museum of Art Annual Ball

Co-Chair, Utah Valley University President’s Ball

Commissioner of Multiple Youth Softball Leagues

A LITTLE TOWN CALLED DEARFIELD

HOW ONE MAN’S VISION BECAME A HAVEN FOR BLACK WESTERNERS

BY GEORGE H. JUNNE JR.

There is an abundance of information on the American West, but start digging in, and you’ll find a gap. There is little history accessible on African Americans and their lived cultural and political lives as generations moved to, settled in and shaped the West. In fact, one-quarter of the cowboys who have so profoundly defined “the West” as we think of it were indeed African American.

Across the West, a few all-Black settlements were established in the early days of westward expansion. And one of those settlements was called Dearfield, Colorado. With little-to-no farming experience, little money and no experience in homesteading, through their hard work the people became successful. The Dust Bowl and the inability to obtain irrigation water doomed Dearfield and other farming communities on the eastern high Plains to become the ghost towns that we now see scattered across the region. But even though the bricks began crumbling and the voices faded from the town, Dearfield is still a place where the true story of life in the early West lives.

OLIVER TOUSSAINT JACKSON was born April 6, 1862, in Oxford, Ohio. He was the son of Hezekiah and Caroline Jackson, two former slaves. They named him after Toussaint L’Ouverture, the runaway slave who successfully overthrew the French in Haiti in 1804.

Hezekiah had learned to read and made sure all six of his children did, too. At the age of 25, Oliver Jackson did what so many in generations that followed would do: Go West. He moved to the Denver area (which had a

DEARFIELD WAS A VIBRANT BLACK COMMUNITY. BUT TODAY, IT’S DIFFICULT TO FIND ON A MAP. ITS RISE AND ITS FALL PARALLEL OTHER FARMING COMMUNITIES IN THE WEST.

population that soared from 4,579 in 1870 to 106,713 by 1890) and got a job as a caterer. He settled into the Colorado life and in 1889, he married Sarah “Sadie” Cook, a relation to the famous composer Will Marion Cook.

In 1894, Jackson made the short move from Denver to Boulder to manage the Stillman Café and Ice Cream Parlor on Boulder’s beloved Pearl Street. He became a staff manager at the Chautauqua Dining Hall in 1898,

supervising 70 people. Customers paid $5 a week or 35 cents a meal. After working in management for some years, he opened his own restaurant on 55th and Arapahoe, where the Boulder Dinner Theatre is now located. His restaurant was famous for its seafood, particularly the oysters. Jackson made enough money that he bought a farm that he owned for 16 years. But in 1908, Republicans won the spring election, making Boulder a dry town and prompting Jackson to make the move back to Denver.

There, Jackson began a 20-year career as messenger for Colorado governors. While he was working for Gov. John F. Shafroth, Jackson was determined to make good use of his political connections and actualize his dream of starting an agricultural colony where Black Americans could own homes and control their municipal government, schools and farms. He forged ahead with his plans, using whatever support he was able to receive from Denver officials as well as the Colorado State Teachers College and the State Agricultural College (University of Northern Colorado and Colorado State University, respectively). In May 1910, he filed a homestead entry on a tract of land outside Greeley. On February 4, 1914, he purchased 40 acres of land for $400 and the community was officially born.

Dr. Joseph H.P. Westbrook, of Denver,

a physician and one of the first settlers of Dearfield, gave the colony its name. At the June 12, 1909 meeting of the founding team, he articulated the sentiments of his colleagues in these words:

“We plan to make this our home. These are to be our fields and because they are ours and because we expect and hope to develop them and make them into substantial homes, they will be very dear to us, so why not incorporate that sentiment in the name we select and call our colony Dearfield.”

The first group of settlers moved to Dearfield in 1911, the same year the Denver-toNew York long distance telephone service was completed. There were immediate problems. Apart from not lending their political support for the project, middle-class Black Coloradans generally showed little interest in relocating to Dearfield. Some of the early settlers were so poor they could not afford to ship their possessions from Denver and had to walk part of the distance. Among the members of this group, only two families could afford to erect their 12-foot by 14-foot homes with a fence. The other five families had to

live in tents or in hillside dugouts. Sometimes the men had to work on other farms to earn money while the women and children worked their land. This tenacity demonstrates how much people wanted to possess their own homes and farms.

Western Farm Life interviewed O.T. Jackson in its May 1, 1915, issue, five years before Dearfield reached its peak. According to reporter Frederick F. Jackson, the Dearfield project included 40 farms of 160 acres each, with the townsite embodying 140 acres. In his judgment, “(I)t took plenty of nerve for this small group of Negroes to go out upon the barren, sage-brush prairie and undertake, without means or capital, to force a living from the unyielding soil.”