RX 350 AWD

RX 350 AWD

RX 350 AWD

RX 350 AWD

Western Alliance Bank is proud to bring our award-winning, expert business banking to Utah, led by seasoned commercial bankers who, like you, have built their lives and careers right here.

With more than $65 billion in assets and a real commitment to helping Utah businesses achieve their ambitions, we’re ready to work hard for you.

Seth Brinkerhoff

Senior Director, Commercial Banking seth.brinkerhoff@westernalliancebank.com (801) 386-3910

Marshall Saunders

Vice President, Commercial Banking msaunders@westernalliancebank.com (435) 513-2650

westernalliancebank.com

#1 Best Emerging Regional Bank 2022, Bank Director

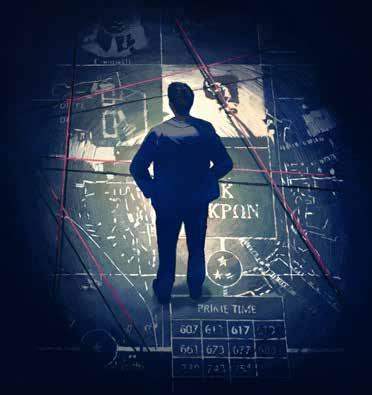

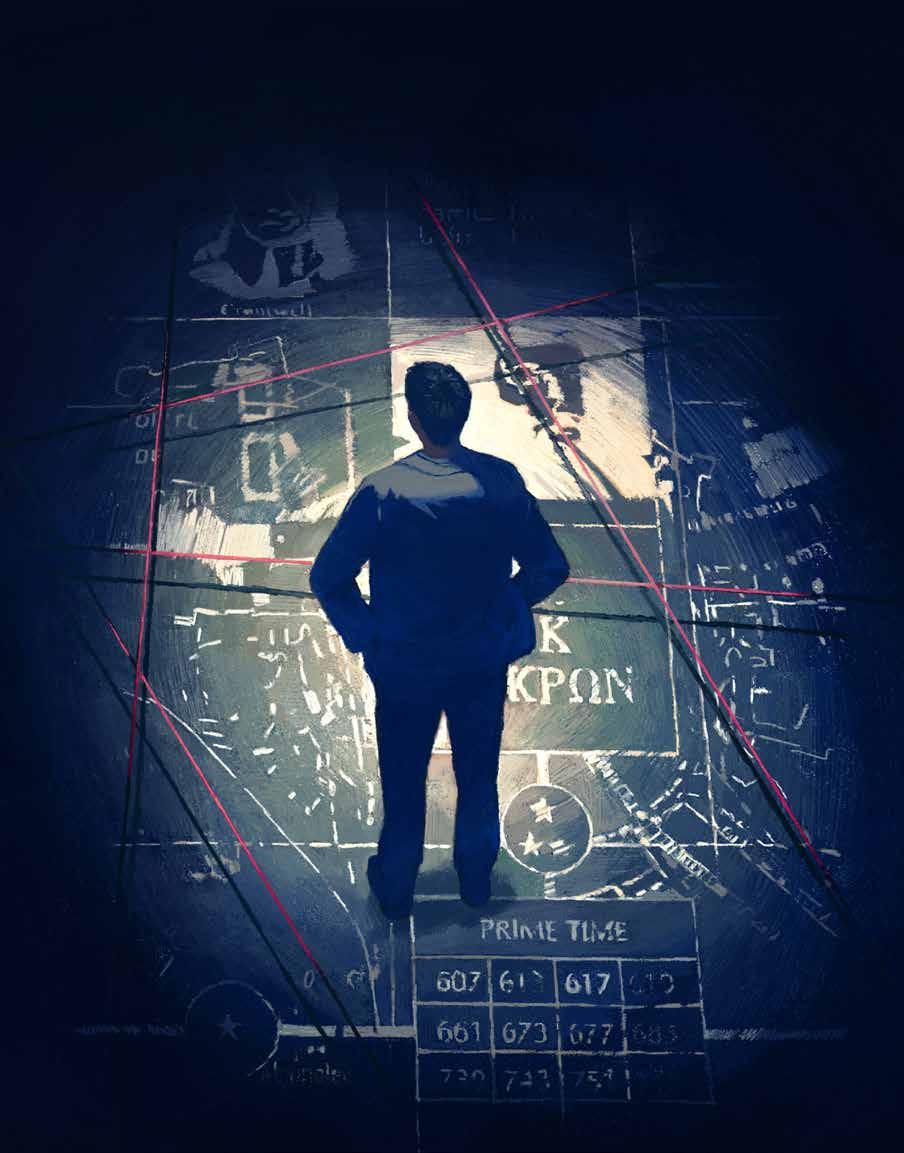

Western Alliance Bank, Member FDIC.A FORMER FOX POLITICAL EDITOR ON HOW NEWS MEDIA PROFITS FROM YOUR RAGE.

by chris stirewalt

60

MEET ONE MAN TRYING TO PRESERVE HIS NATIVE TONGUE AND CULTURE. by ethan bauer

68

WILL ARIZONA’S DECADESLONG COLLEGE MYSTERY EVER BE SOLVED?

by ciara o ’ rourke

“It is sadly fitting that the acrid, partisanshipsoaked public discourse created by our dumb news media prevents needed repairs to the media itself.”

How friendship fosters economic opportunity. by shaylyn romney garrett

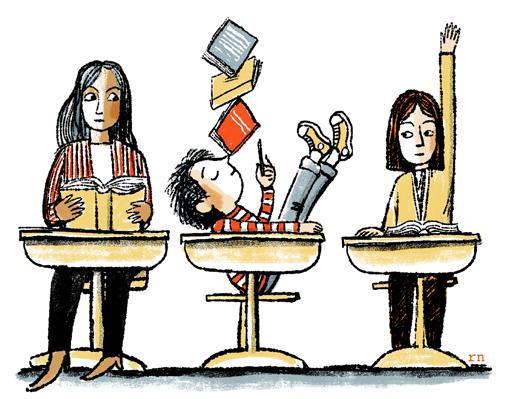

It’s not just the kids. Parents can’t focus either. by deborah farmer kris

Both political parties agree: The border is in crisis. by benjamin bombard

To the desert. And beyond. by ethan bauer

If Republicans take the House, investigations are coming. by mya jaradat

Can anyone afford to live in America anymore? by heather hansman

‘The grid,’ as we know it, is changing. by miyo m c ginn

Why young men are struggling. a conversation with richard reeves by suzanne bates

Americans are drinking less alchohol. These ‘bars’ are counting on it. by fendi wang

How to win arguments without alienating people. by lois m collins

ROBIN RITCH

HAL BOYD

JESSE HYDE

ERIC GILLETT

MATTHEW BROWN

CHAD NIELSEN

JAMES R. GARDNER LAUREN STEELE

SUZANNE BATES

MICHAEL J. MOONEY

ETHAN BAUER MYA JARADAT

LOIS M. COLLINS KELSEY DALLAS JENNIFER GRAHAM

ALEXANDRA RAIN GENEVIEVE VAHL

IAN SULLIVAN

BRENNA VATERLAUS

TODD CURTIS

CHRIS MILLER MADISON TAYLOR

SARAH HARRIS TYLER NELSON

ETHAN BAUER ISABEL BOUTIETTE LAURENZ BUSCH ANNE DENNON ALEXANDRA RAIN GENEVIEVE VAHL

PAUL ADAMS DAN BEJAR HARRY CAMPBELL MICHAEL DRIVER

MARY HAASDYK KYLE HILTON HOKYOUNG KIM JORDAN LAYTON JOE MAGEE

STUDIO MUTI ROBERT NEUBECKER CHRISTIAN ROUX MORIAH RATNER LAURA SEITZ OLIVIA WALLER

Deseret Magazine, Volume 2, Issue 19, ISSN PP324, is published 10 times a year by Deseret News Publishing Co., with double issues in January/ February and July/August.

The Deseret News’ principal office is 55 N. 300 West, Suite 500, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Subscriptions are $29 a year. To subscribe visit pages.deseret. com/subscribe. Copyright 2022, Deseret News Publishing Co. All rights reserved. Printed in the USA.

DESERET, proposed as a state in 1849, spanned from the Sierras in California to the Rockies in Colorado, and from the border of Mexico north to Oregon, Idaho and Wyoming.

Informed by our heritage and values, Deseret Magazine covers the people and culture of that territory and its intersection with the broader world.

Romney Garrett graduated from Harvard University before serving in the Peace Corps and co-founding the nonprofit Think Unlimited, mobilizing social innovation in the Middle East. She is a founding contributor to Weave: The Social Fabric Project and co-authored with Robert D. Putnam “The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again.” Her commentary on cross-class friendships is on page 16.

McGinn is a freelance writer focusing on the intersection of the climate, the environment and humanity. Her work has appeared in Grist.org, Outside Magazine, Popular Science and New York Magazine. McGinn received a bachelor’s degree in sociology at Middlebury College and is the recipient of the 2022 High Country News’ Bell Prize for young writers. Her report on why Western states lag behind in developing renewable energy is on page 48.

Stirewalt is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Prior to joining AEI, he was political editor and coordinated specialized polls and voting trend analysis at Fox News Channel. He is a former political editor for the Washington Examiner and Charleston Daily Mail in West Virginia. An excerpt from his latest book, “Broken News: Why the Media Rage Machine Divides America and How to Fight Back,” is on page 52.

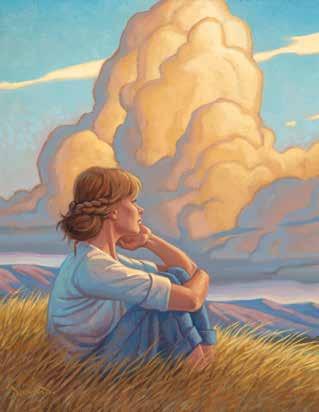

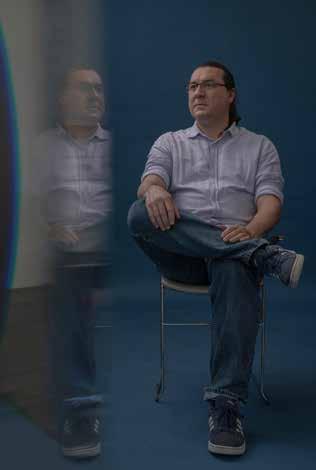

Born and raised in Seoul, South Korea, Kim studied painting at Hongik University and illustration at Ringling College of Art and Design. She resides in Queens, New York, and her clients include The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, Medium, ProPublica, the Intercept and Current Affairs. Her work appears on page 68.

A Salt Lake City native, Bombard is a writer and radio producer. His written work has appeared in numerous publications, including Western Horseman, The Salt Lake Tribune and Catalyst Magazine. His audio work has been featured on RadioWest, KUER/NPR Utah, BBC/PRI The World and Nick van der Kolk’s “Love+Radio.”

On page 32, Bombard examines how immigration has vexed both Republican and Democrat policymakers.

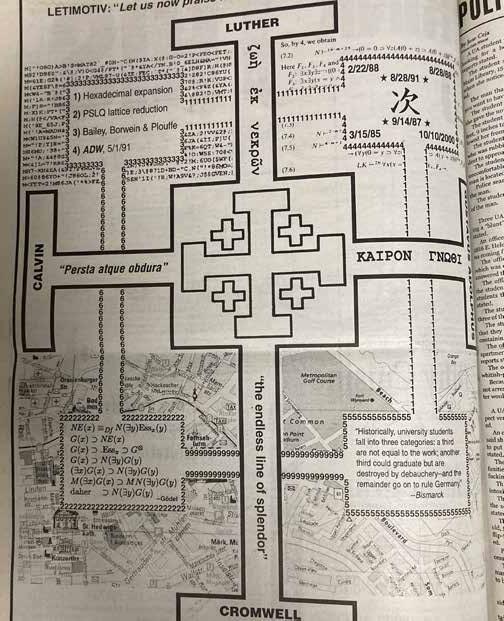

O’Rourke is a freelance writer who has contributed to publications including The Atlantic, Seattle Met and The New York Times. She’s a former reporter for the Austin American-Statesman in Texas, and studied journalism and French at Western Washington University. She was also a 2015-16 Ted Scripps Fellow in Environmental Journalism. O’Rourke’s story on page 68 is about the quest to solve “Arizona’s Da Vinci Code.”

Waller is a Brighton, England-based illustrator and printmaker, whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Guardian, the Lily (The Washington Post), Stylist Magazine, Zetland Magazine and Penguin Random House, among other publishers. Her art is dedicated to celebrating women and has been exhibited at Wickle, Lewes, Art Wave and Seaford, Crit Club. See Waller’s work on page 20.

Wang is an editor at Godfrey Dadich Partners, a design and editorial agency, and lives in San Francisco. She graduated from Northeastern University and is the founding editor of MINDSWIM, an online magazine. A regular contributor to Deseret Magazine, Wang’s story on page 80 explores the growing trend of nonalcoholic bars in cities across the United States.

In the SEPTEMBER issue, “The Fate of the Religious University,” Elder Clark G. Gilbert, commissioner of education for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, challenged the country’s faith-based colleges and universities to not shy away from their distinctive legacy and role in higher education (“Dare to be Different”). “It is important for religious schools to assert the rights of their students and their communities to learn and work in a religious setting,” he wrote. Supporting essays contributed by university presidents and scholars were shared by the likes of American Council of Education, Duke Divinity School, Utah Gov. Spencer Cox and Brookings Institution scholar Richard Reeves. Brad Wilcox , director of the National Marriage Project, quoted Gilbert’s insight into religious schools maintaining their faith-centered priorities, before tweeting, “In other words, Harvard or Michigan should not be the lodestar” to his 19.5k Twitter followers. And President Dallin H. Oaks, first counselor in the First Presidency of the church, referred to Gilbert’s essay in a devotional at the church-owned Brigham Young University: “Those who deviate from a majority are often made to feel like ignorant holdouts on subjects where everyone else is more enlightened. When higher education or the world in general call upon faculty to vary from gospel standards, do we ‘dare to be different?’” Also in the September issue, contributing writer Mary McIntyre wrote about how a local Montana butcher is trying to fix one of the country’s most broken markets — the meat industry from rancher to consumer (“Chopped”). The Price-Pottenger Nutrition Foundation praised the story on Twitter: “Anna Borgman, a butcher at Amsterdam Meat Shop in Montana, is doing her part along with other independent butchers to provide fair pricing for family-owned beef ranches struggling to survive and compete.” Staff writer Ethan Bauer took readers on a journey between past and future climates in his story about paleontologists unearthing ancient dinosaur remains in southern Utah (“Bones”). The experts explained how studying fossils could change how we see the past — and the future. The Utah Natural History Museum recom mended it on Twitter as “a great #fossilfriday read from Deseret.” College sports fans have been inundated the past year with reports about student athletes cashing in on marketing their name, image and likeness, or NIL . Contributing writer Eric Adelson attended a conference in Atlanta on NIL and came away with an enlightening report (“Inside the College Sports Gold Rush”) on how college administrators, sports agents, student-athletes and fans view this new era of economic opportunity and uncertainty. Todd Harris, a sports announcer and reporter for NBC Sports and NBCSN , shared the story with his 20.4k Twitter followers. And most readers came down on the side of student-athletes who can now use their talents to make a living while in school as other students can in the arts, sciences and other disciplines. Clark Robinson wrote, “This could be good for college sports. More athletes may be willing to stay in college and not rush to the pros for a payday. I won’t be surprised if star college QB s are making more than backup NFL QB s in a year or two.”

With Real Love® nothing else matters; without it, nothing else is enough.

Easily learn and master a practical process to parenting. ELIMINATE confusion and frustration with your children. Transform your family with Real Love Parenting. Your children will feel loved, loving, responsible and happy.

WHAT PARENTS AND THERAPISTS ARE SAYING ...

This is information that every parent needs ...

As a marriage and family therapist for 30+ years, I have seen parenting become increasingly challenging among even the most dedicated parents. With the bombardment of the Internet and social media, children AND parents are facing their insecurities about any number of issues, particularly when it comes to deepening connections. Parents want to love their children. It sounds simple, but it isn’t; at least not until now. Greg Baer, M.D. is better at teaching parents HOW to unconditionally love and teach their children more than any other professional I have come across. The Ridiculously Effective Parenting Training should be in EVERY home.

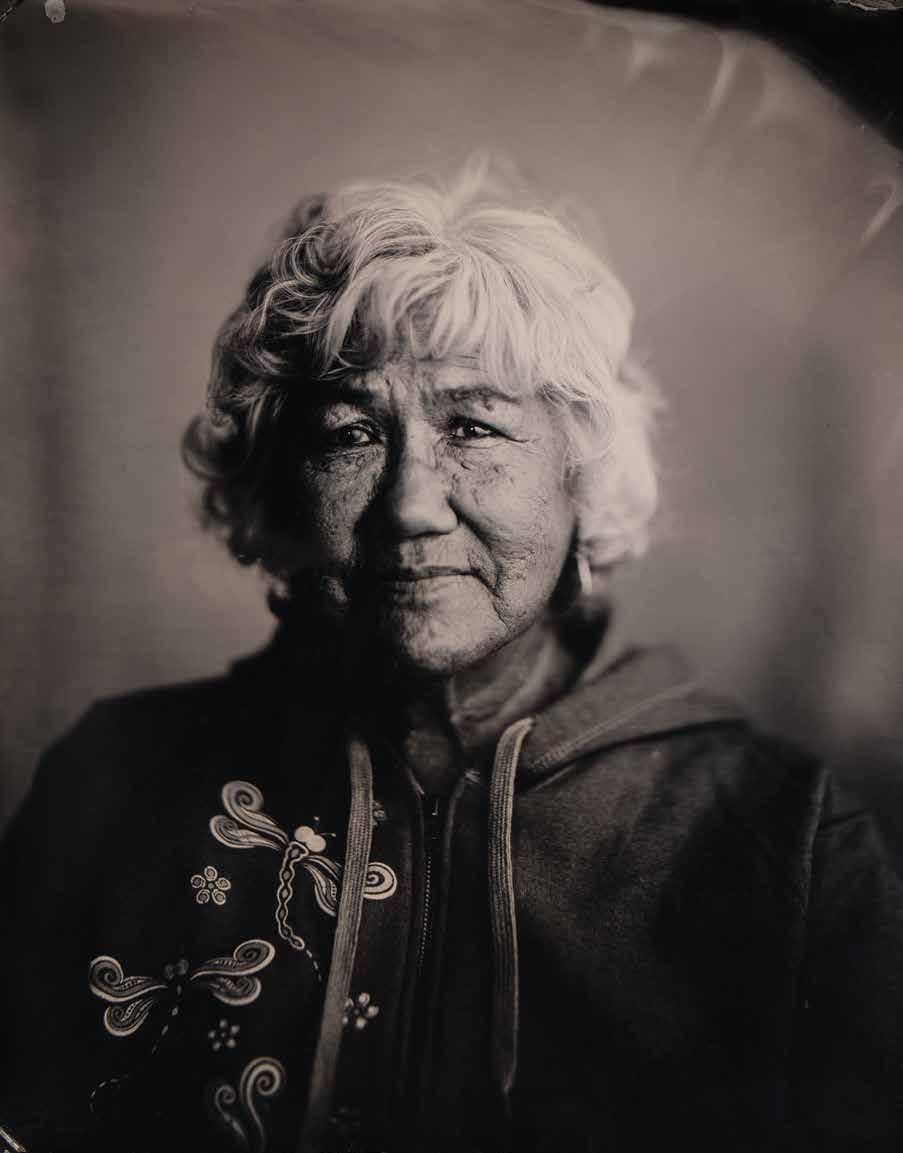

My grandma used to drive a white Cadillac.

It had an eight-track player and white leather seats. I liked riding in it. I liked how roomy and plush it was and how it seemed to not even bounce along the highway, but float, like a magic carpet. I liked listening to Charlie Pride and Patsy Cline and whatever else she put on as we drove to Elko to watch my grandpa race horses.

Sometimes we went out to the desert to look for rocks under the pale blue Nevada sky. We collected the ones she could shine up like gem stones. They were red and purple. She put them on the patio behind her art studio, where she painted her favorite horses. FlickerDeBar. Miss DeSpeed. Kissin’ John.

As I got older, I began to appreciate my grandma’s stories more and more. They were stories of another time, of horse-drawn sleighs and hipdeep snow, of mountain cabins without running water, of a cross-coun try move to Florida to work on the church cattle ranch, where my dad, still in a cloth diaper, wandered into a pond and nearly got eaten by an alligator.

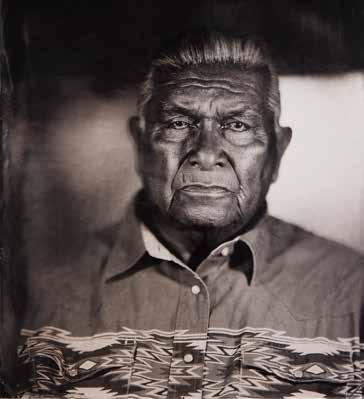

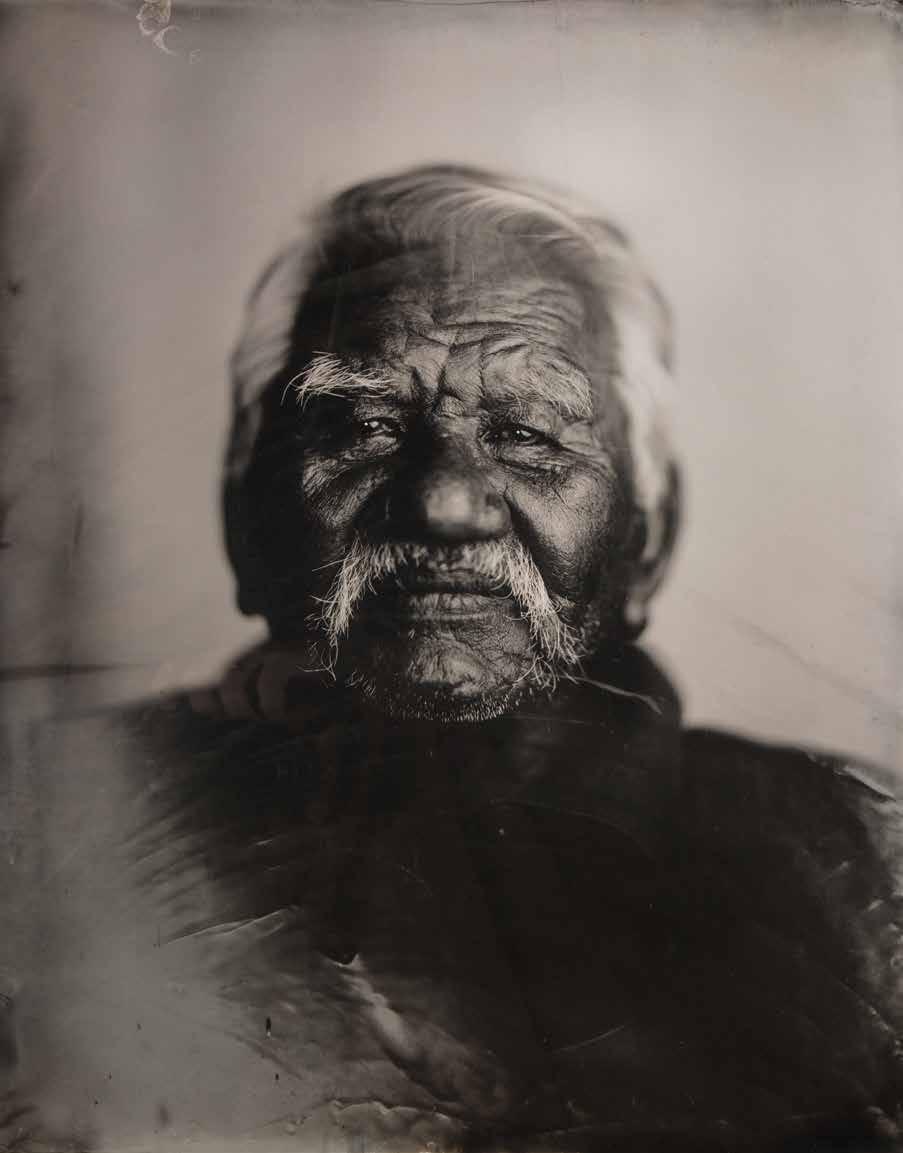

I thought of these stories as I read this month’s cover story (Fading Whispers, page 60) about a man named Ernest Siva’s effort to preserve the history of his people. Siva, who lives on the Morongo Indian Reser vation in Southern California, told staff writer Ethan Bauer of falling asleep listening to his grandfather, and how he didn’t know if what he was hearing was just a bedtime story, or something deeper, a parable. Other times, Siva’s grandfather would sing “bird songs,” which told the origin stories of his people.

Siva’s goal isn’t just to save native languages. He wants them to sur

vive, to grow and evolve. “Our languages connect us to our ancestors and to our homelands,” Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American Cabinet secretary, told the magazine.

It reminded me I’d been meaning to record my grandma’s stories for some time, so my kids could hear them. I promised myself I would make a point of doing just that on my next visit home. There is something universal in not forgetting our ancestors and where we come from.

As we were closing this issue, I got a text from my sister. My grand ma had a heart attack. She was on a medical helicopter to Reno. It didn’t look like she would make it and I feared I’d missed my chance to record her stories.

That night I pulled an autobiography she wrote from a shelf in my home office and flipped through it, pausing to study the pictures, which span from the 1930s to the present. I marveled at how much the world has changed. There was a picture of a Model T. An outhouse. A family photo taken in 1979. I’m three years old, wearing a red suit. My uncle Gary is resplendent in bell-bottoms.

Two days before we went to press, I called my grandma. She had been released from the hospital and was back home. She said she was feeling just fine. She’s 88. I told her she could make it to 98, at least. We all need you around, I told her. She laughed. “We all die,” she said gently. “I’ve lived a good life. I’m not afraid to go.”

I told her I’d see her at Thanksgiving. And this time, I promised, I’ll make sure to bring a tape recorder.

It will get brighter.

BY SHAYLYN ROMNEY GARRETT

BY SHAYLYN ROMNEY GARRETT

The American dream is on life sup port. For more than 50 years the per centage of American children who grow up to earn more than their parents has been in decline. Only half of kids today will achieve that basic goal, and a child born into poverty has a mere 7.5 percent chance of making it to the top. The notion of this nation as a land of opportunity has never been further from the truth.

Simultaneously, America’s social fabric is in tatters. For more than 60 years, social capital — informal ties to friends, neighbors and fel low citizens — as well as solidarity and social trust, have been in sharp decline. We are living increasingly isolated and segregated lives. The ideal of America as a nation of neighbors has never been more out of reach.

Social scientists have long believed that these two phenomena are related. But thanks to a new study by intrepid economist Raj Chetty, we now have the data to prove it.

Chetty was one of the first social scientists

to mine “big data” for insights into what’s really driving economic and social problems in America. He and his team first used ano nymized income tax records of 40 million chil dren and parents to create a color-coded map

study on economic mobility: Whether or not children achieve the American dream depends largely on something entirely out of their con trol — the ZIP code into which they are born.

In their latest study — published in Nature in August — Chetty and his colleagues ana lyzed privacy protected data on 72.2 million Facebook users to create a color-coded map that details exactly where our social fabric is strong, and where it’s coming apart. The big gest takeaway from this landmark study on social capital: ZIP codes that have high levels of social capital have high levels of economic mobility. Broadly speaking, the two maps are nearly identical.

that provides an unvarnished and strikingly detailed picture of where American kids are succeeding economically, and where they are not. The biggest takeaway from this landmark

MANY DIFFERENT KINDS of social connections make up a society. But one important distinc tion is between bonding (associations we make with people like ourselves) and bridging (as sociations across lines of difference). Because of the richness of the Facebook data, Chetty and his colleagues were able to drill down even

THERE’S JUST NO WAY TO SOLVE AMERICA’S ECONOMIC MOBILITY PROBLEM WITHOUT SOCIETY’S ECONOMIC WINNERS REACHING ACROSS THE CHASM OF CLASS TO LEND A HAND TO EVERYONE ELSE.

further to measure two specific aspects of in terclass bridging, one they call “exposure” and the other they call “friending bias.”

Exposure measures the economic diversity of a given setting — how likely you are to en counter someone who doesn’t share your so cioeconomic profile in the various spaces you move through in society. High “exposure” in a given setting means more economic diversity.

“Friending bias,” on the other hand, mea sures the likelihood that in a particular setting you will not just encounter someone from a different social class, but will actually form a connection across the class divide. Low “friending bias” means that low-income peo ple have lots of high-income friends, and vice versa.

Teasing out these two threads of our social fabric adds crucial nuance to discussions of how to help more kids achieve the American dream, because most reform efforts to this end have focused solely on exposure: creating systems, spaces and structures that increase economic diversity. But Chetty’s data shows that more exposure doesn’t necessarily mean more friending.

Take mixed-income neighborhoods. Build ing affordable housing in more affluent areas means that the opportunity for social interac tion between disparate classes goes up. Rich folks and poor folks will see each other out walking dogs and playing on the playground, but there’s no guarantee that the kids in the new apartment complex will be invited to the neighborhood pool party at the house down the block. As a result, personal connections that would help them access new opportuni ties may never be made.

Similarly, universities can do away with admissions policies that favor “legacy” appli cants over first-generation applicants who are equally qualified. But while leveling the admissions playing field will likely increase cross-class exposure on campus, getting legacy students to befriend underprivileged students is another matter entirely. Thus, the networks first-gen students need to make it to gradua tion, find mentors and land jobs may never form.

This likely explains why, despite significant public investment over the past several years in efforts to reverse economic segregation, economic mobility hasn’t improved much, if at all. It’s not that exposure doesn’t matter, it’s

that getting rich people and poor people to occupy the same space is just not enough.

Indeed, this big-data insight proves what might have been obvious were it not so hard to hear: Even if we fix all the broken systems that segregate people economically, we still have to do the work of interacting with one another in meaningful ways. Whether it’s across the tracks, across the street or across the lunch room, there’s just no way to solve America’s economic mobility problem without society’s winners reaching across the chasm of class to lend a hand to everyone else.

That may seem impossible to imagine in a society that has reached historic levels of cul tural self-centeredness, but in fact it may be easier to tackle friending bias than segregation. Creating more economically diverse commu nities often involves reimagining geographies, addressing codified discrimination, mobilizing scarce resources and coalition building among stakeholders who disagree on how to restruc ture society.

But this new statistical story of the rags to riches idyll has a surprisingly personal, and hopeful, dimension. It turns out that breath ing life back into the American dream can start immediately, with just one intentional interaction between two people of different social classes — a single act of friending.

SO HOW DO we get more people to not just encounter each other, but actually connect across lines of economic difference? Consider which communities or institutions in our so ciety are doing “friending” particularly well. From among the 21 billion Facebook connec tions that Chetty and his colleagues analyzed, a clear trend emerged: Americans are more likely to befriend someone of a different social class in a religious setting than in their neigh borhood, in high school, at work or even in college. The data show unequivocally that the place poor kids and rich kids are most likely to become friends is at church.

But what is it about religious settings that makes them more fertile ground for unlikely friendships? And what can secular institutions, whose success at fostering friending plays a key role in keeping the American dream alive, learn from religious groups?

The logic of how and why we connect with people varies across the institutions and com munities we’re a part of, but in most cases it’s

self-promotion by association. We think that success is not what you know but who you know, and it doesn’t pay to seek out people who are worse off.

In a religious context, however, this logic is generally turned on its head. People encoun tered in the pews aren’t status symbols, door openers or rungs on the ladder to success. They’re fellow travelers on a humbling path to encountering God. Thus, social and eco nomic hierarchies are superseded by common purpose, common values and common ideals. Rather than being yet another arena in which to compete, religious spaces instead cultivate an ethic of camaraderie.

Religious encounters also offer opportuni ties to gain real insight into the lives of others, which is rare in a culture dominated by cu rated images. At a 12-step meeting or a grief support group, vulnerability and authenticity are prized, while posturing and pretense just don’t play. Sharing about life’s struggles fos ters a sense of empathy and creates pathways to genuine relationships that are often hard to come by in other settings.

But it’s not just the nature of interperson al encounters in religious settings that foster what Chetty and his team call friending. It is also the unabashed project of moral formation in which religious institutions are engaged. Nearly every religious tradition lauds love, generosity and selflessness as the virtues that build us up; while denouncing pride, greed and self-centeredness as vices that unravel our foundations. Though rarely, if ever, enact ed perfectly, the call to lend a hand to people who are struggling is something believers are taught to do as an expression of their highest ideals. By putting forward a clear narrative about its value, religious communities endow social integration with a higher meaning and purpose, incentivizing adherents to reach out, befriend and lend a hand.

And religious organizations don’t just preach social integration and economic re distribution from the pulpit, they have also built enormous infrastructure to facilitate it — an underrecognized feature of our nation’s social safety net which, were it to disappear overnight, would leave millions of Americans without basic necessities.

OF COURSE, RELIGIOUS institutions are not the only ones capable of inducing people to associate

across socioeconomic lines. Schools, colleges, civic groups, workplaces, neighborhoods and many other settings in which Americans live out their daily lives can in fact be wellsprings of both interclass exposure and friending. But the peo ple within them must be courageous enough to intentionally foster not only structural inclusiv ity but also — and equally crucially as Chetty’s study indicates — behavioral inclusivity. Our secular institutions must also engage in the mor al formation of citizens, who are ultimately the ones who will choose to look out and not in, and to lend a hand.

But what would that secular moral for mation look like? Exactly what it looks like in religious settings: Creating a shared sense of identity that supersedes apparent differ ences. Offering opportunities for people to interact authentically. Promoting empa thy and genuine connection. Constructing meaning-making narratives that uphold vir tues like generosity, selflessness and unity. And providing pathways to act upon these ideals.

Looking to religion for clues about how to revive the American dream may seem awk ward in our rapidly secularizing society. More and more Americans seem to believe that re ligion is a source of our problems, not a well spring of their cure. And some of this cynicism rightly stems from the fact that religious in stitutions and religious adherents have often failed to live up to their own moral code.

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. famously said that the most segregated hour in Amer ica is 11:00 on a Sunday morning. Though that was more true in the mid-1960s than it is today, attending the house of worship around the corner — whether Catholic or Methodist or Muslim — usually means joining a group whose economic and racial profile is remark ably homogenous. If they would amplify their influence as drivers of economic mobility, then religious institutions must think deeply about how to increase diversity and avoid insularity.

But it’s not just about religions failing to practice what they preach. Sometimes the preaching is the problem. The prosperity gos pel, for example, which has taken hold in cer tain parts of American Christendom, teaches that God rewards the righteous with wealth. In this framework, poverty is a sign of personal moral failing, rather than a social ill we must all work together to cure. Religious teaching must be careful not to frame the less fortunate as people to be pitied or disdained.

And, of course, there’s a lot of hypocrisy at play when religious Americans engage in pol itics that protect their own interests and lock others out of opportunity. Moral formation is only complete when behavior changes not just at church suppers, but at school board meet ings, on planning commissions, in neighbor hoods and in voting booths.

Indeed, the faithful are not without their blind spots. While Chetty’s data clearly shows that religious spaces are some of the bestequipped institutions in America for making cross-class “friending” actually happen, there is still ample room for reform if religious groups want to truly maximize their ability to elevate the least among us.

One of the most famous passages in Chris tian scripture is the parable of the good Samar itan. As the story goes, a lawyer approaches Jesus and asks how he can gain eternal life. He knows he must follow the Jewish law — Love thy neighbor as thyself — but he wants some clarification about exactly what that means. “Who is my neighbor?” he asks.

Jesus responds with a parable. A man, pre sumably Jewish, is attacked, robbed and left for dead on the side of the road. A priest and a Levite, both at the top of the social hierar chy, pass him by. Only a Samaritan — a segre gated group despised by the Jews — stops to care for the injured man. He binds his wounds, provides him shelter and pays for an innkeep er to look after him. Jesus then asks the lawyer which of the three — the priest, the Levite or the Samaritan — acted as a neighbor to the wounded man. The lawyer responds, “The one who showed him mercy.”

This parable contains a many-layered les son, but one is assuredly this: The morally formative invitation to “love thy neighbor” is less about proximity and more about reaching across lines of difference. Though we may oc cupy the same spaces as unlike others — pass ing them in our neighborhoods, schools and workplaces — it is only the one who reaches out in love and empathy that truly lives out the ideal of neighborliness.

Religion has long taught that relationship, compassion and care — “friending” — can cure what ails our society. And we now have the data to prove it.

RELIGION HAS LONG TAUGHT THAT RELATIONSHIP, COMPASSION AND CARE —

“FRIENDING” — CAN CURE WHAT AILS OUR SOCIETY. AND WE NOW HAVE THE DATA TO PROVE IT.

Recently a girlfriend told me, “I always pictured having a large fami ly, but motherhood is so much more difficult than I imagined it to be!” I hear variations of this frequently from friends with one or two children; that it’s just too hard, and that adding more children to the mix would break them. The reality is that the style of parenting they’ve adopted, that of “positive,” “gentle” or “responsive” parenting is actually what’s breaking them; and I can see why they find motherhood so crushing.

Writing for The New Yorker on gentle par enting in March, Jessica Winter explains, “In its broadest outlines, gentle parenting cen ters on acknowledging a child’s feelings and the motivations behind challenging behavior, as opposed to correcting the behavior itself. The gentle parent holds firm boundaries, gives a child choices instead of orders, and eschews rewards, punishments and threats — no sticker charts, no time-outs, no ‘I will turn this car around right now.’ Instead of issuing commands (‘Put on your shoes!’), the parent strives to understand why a child is acting out in the first place (‘What’s up, honey? You don’t want to put your shoes on?’) or, perhaps, narrates the problem (‘You’re playing with your trains because putting on shoes doesn’t feel good’).”

John Rosemond, a family psychologist and

author of bestselling books on child rearing and family life, told me the philosophy is an offshoot of psychological theories popularized among those in the professional mental health world in the 1960s and ’70s. He explained, “The main theme of it then is the same as the main theme of it now: Essentially, children communicate via their emotions because they

psychological disturbance.”

This acquiescence comes in countless par enting decisions, big and small, but I would argue the three most disruptive come in the areas of food, sleep and technology.

When leaving the house for a quick vis it to the park or playground, it’s common to see mothers leaving with half of the kitchen packed in their bulging diaper bags. The result is a steady stream of snacks the entire day, with mom doing the heavy lifting, packing and dis tributing them.

lack the sophistication of the language to do otherwise very effectively. And it is of utmost importance that parents properly interpret and properly respond to their children’s emo tional communication. … Parents are being scared to death by people with a Ph.D., whom they assume they know what they’re talking about. They’re scared that if they don’t ac quiesce to their children’s emotions, they would be causing their children all kinds of

Experts advising parents on how and what to feed kids don’t make the situation any better. One such expert, Jennifer Anderson (known on Instagram as @kids.eat.in.color), a registered pediatric dietician, boasts 1.8 mil lion followers and dispenses advice for “picky eaters.” Most of Anderson’s advice is helpful; like suggestions to make low-sugar yogurts tastier, or the proper protein serving sizes for a toddler (surprisingly small; comforting in formation if you find yourself wondering how your two-year-old can eat so little and remain alive). Other advice is great, like a suggested schedule of snacks and meals, telling parents “you’re in charge of when food is served.” But she also falls into the gentle parenting trap on occasion, with one such post telling parents, “Serving at least one food your child likes at all meals and snacks isn’t catering, it’s honoring

IS THE TREND OF GENTLE PARENTING A MISTAKE?

“PARENTS ARE SCARED THAT IF THEY DON’T ACQUIESCE TO THEIR CHILDREN’S EMOTIONS, THEY WOULD BE CAUSING THEIR CHILDREN ALL KINDS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTURBANCE.”

their need for time to learn to like new foods.”

This is exactly the advice that scares parents off of having more than one or two children at most; because the result is it turns parents into short order cooks. I have five children; I don’t even remember all of my kids’ (ever shifting) likes and dislikes at any given time. We have set meal and snack times, as Anderson rec ommends, for my sanity, but we also serve one snack or meal, not catered and made-to-order requests. And if they don’t like it? Then they don’t eat it. My pediatrician (himself a father of six) told me something recently at a well-visit for my one-year-old that he said comes as a surprise to most of his patients: a child can go to bed hungry. They can, it’s OK. It also estab lishes a power dynamic that children need to understand: It’s parents, not children, that are in charge, not the other way around.

Literally the most exhausting part about being a parent is the associated lack of sleep. As a mother of five, I understand that ex haustion deep, deep in my bones. Which is why I’m such a big believer in setting firm boundaries around sleep. Friends often tell me their sleep woes: Spending an hour or two on the floor of their child’s room, waiting out their children in a battle of wills, trying to get them to go to sleep. Emily Oster, a Brown University economist with expertise in parenting from a data-driven perspective and the author of three data-driven books on parenting, told me, “There is a lot of evidence suggesting that consistency is important in generating behavior change in parenting — in implementing a sleep routine, in enforc ing meal-related behaviors, etc. Inherent in consistency is some limit-setting and some parental structure. Doing whatever kids want in a given evening is more or less guaranteed not to be consistent because kids are not con sistent. This can be a challenge.”

And I want to be clear: I am by no means perfect on sleep; last night I climbed into my one-year-old’s crib at five months pregnant and spent an hour there with him during a truly epic and somewhat terrifying thunder storm. In my conversation with Rosemond, I asked him the difference between honoring children’s emotions and becoming beholden to them, and he gave excellent advice: Par ents need to separate emotional needs from impulses. My one-year-old’s middle of the night thunderstorm wakeup wasn’t because he didn’t want to sleep or because he wanted

to play; he genuinely needed me out of fear of the storm, our windows rattling with the sound of thunder.

But on an average night, there is no ne gotiation. Kids sleep with leak-proof sippy cups, and there are no last-minute requests for books, snacks or other stalling tactics. We have a set routine that everyone understands: Mom puts baby to bed while my older four children (age three to eight) dress in the pa jamas I’ve set out, brush their teeth and floss. When I’m done with the baby’s bedtime, the three-year-old is tucked in and kissed, with as surances that I’ll “come and check on her” at some point in the night. If she wanders out of bed, she is met with a stern demand to return, which she is expected to do on her own. The older three children get one chapter of a novel we’re reading, then it’s lights out for them, too.

‘cry it out’) improves infant and child sleep, and improves sleep for parents, lowers depres sion, improves marital satisfaction. There is also good randomized evidence refuting the idea that sleep training leads to long-term problems with attachment.”

While parents of younger children are fight ing the battles over sleep and food, parents of older children and teens have their own strug gle: technology. According to Common Sense Media, in 2019 (the numbers are likely dras tically different post-pandemic) the majority of 11-year-olds in America already owned a cellphone. Naomi Schaefer Riley, a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and the author of “Be the Parent, Please: Stop Banning Seesaws and Start Banning Snap chat,” literally wrote the book on why and how parents need to be keeping their kids off cell phones and devices as long as possible. Riley sounded a similar note as Rosemond on needs vs. wants, and the imperative of parents to tell the difference. Riley told me, “What you’ll hear typically is that your child will need this device in order to ‘make friends,’ ‘make plans,’ ‘find them’ or ‘for safety.’ There are definitely parents with different circumstances, but par ents need to ask themselves is this actually a need? Imagine when you were a child. What did parents do before cellphones?”

They can read on a Kindle if they want, but I am “done parenting” and they know that while I’m there for an emergency, they are expected to go to sleep.

This strictness around bed makes every one happy: Kids know what to expect and are getting an adequate amount of sleep to keep their brains developing as they should, and it ensures I stay as rested as I possibly can, ready to handle the next day with a full cup instead of running on empty.

In “gentle” parenting circles, there is no greater villain than “sleep training.” Parents are told they are ruining their children for life; teaching them that parents cannot be trusted and that letting them “cry it out” is a form of “neglect.” To this, Oster responds, “There is significant evidence suggesting that sleep training (i.e. some form of what people call

There is a clear connection between rates of cellphone use and the growing rates of anx iety, depression, bullying and access to por nography among teenagers. While unhealthy patterns of eating and sleep, established from a young age, have a deleterious effect on devel oping bodies and minds, so too does access to smartphones and internet-enabled devices in the preteen and early teenage years.

Parenting is hard, but in many ways, we’re making it harder on ourselves by trying to be “gentle” and “positive” versions of our selves. In the short-term, many of us find it easier to capitulate on sleep, food and technology; it’s easier to give in than stand our ground. And we have an entire parent ing philosophy and dominant culture en couraging us to do so. But in the long-term, it’s making parents and children alike less happy, worse versions of ourselves, turning family life into misery unnecessarily.

THERE IS SIGNIFICANT EVIDENCE SUGGESTING THAT SLEEP TRAINING IMPROVES INFANT AND CHILD SLEEP, AND IMPROVES SLEEP FOR PARENTS, LOWERS DEPRESSION, IMPROVES MARITAL SATISFACTION.

Since starting this paragraph, I have been distracted by a police si ren, an Instagram alert and a text from my spouse. I suddenly remembered that my son didn’t put on sunscreen before camp and that I needed to pick up beans for dinner. And then the doctor’s office called to schedule my annual mammogram. When I hung up, I started a new document because, in my fid gety preoccupation, I had closed the old one.

Attention is the ability to direct our lim ited mental resources when and where we need them. The key word here is “limited.”

Attention is a finite cognitive resource — a battery drained by overstimulation, multi tasking, worry, distraction, pings and dings.

I have worked in schools for over 20 years, and I have never heard so much dis may about the inability to focus as I have the last couple of years. Mostly from parents. Talking about themselves.

In a quest to resuscitate my own execu tive functioning — and support my chil dren’s attention skills — I have found cause for optimism in the work of neuroscientists and learning experts. This article doesn’t address medication (though that can be beneficial for some people in consultation with their doctors). They offer hope in the form of understanding how attention works, what drains it and how we can restore it.

Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger is best known for the “miracle on the Hudson,” suc cessfully landing a commercial airliner on the river after both engines were disabled by birds. In recounting how he approached this unthinkable task, he said he relied on more than his aviation training: He drew from his understanding of neuroscience.

two tasks at the same time if both activities re quire focus. Sure, most of us can walk and talk at the same time because walking is an auto matic process. But if we are suddenly distract ed by a siren or a scream, we will stop walking and devote our full attention to understanding the situation.

Likewise, we can’t read our texts and talk to our kids at the same time. And our kids cannot simultaneously watch TikTok videos and do math homework. We can try (and we will), but the result is a bad game of mental pingpong. This rapid task-switching drains our attention battery much faster than unitasking, or doing one task at a time.

Barbara Oakley, author of the book “Learn ing How to Learn: How to Succeed in School Without Spending All Your Time Studying,” points to another attention myth: that you only learn when you are focusing.

“I knew that multitasking is a myth. I knew that when we think we’re multitasking, what we’re really doing is switching rapidly between tasks and not doing any of them well.” Instead of trying to do everything in those pivotal minutes, he said he “chose to do only the most important things but do them very, very well.”

He’s right. Our brains cannot effectively do

Think of your brain like an athlete in train ing, Oakley told me. “You can’t keep running at top speed for hours at a time, just as you can’t run at top speed mentally for hours at a time.” Most people can only devote their “top mental concentration” for an average of four hours a day.

Luckily, learning also happens during down time. In fact, purposefully building in brain

IT’S NOT JUST THE KIDS. PARENTS CAN’T FOCUS EITHER

“MULTITASKING IS A MYTH. WHEN WE THINK WE’RE MULTITASKING, WHAT WE’RE REALLY DOING IS SWITCHING RAPIDLY BETWEEN TASKS AND NOT DOING ANY OF THEM WELL.”

breaks supports both attention and cognition. Oakley describes this as deliberately shifting between “focused mode and default mode.”

Default mode can be described as wakeful rest: daydreaming or mind-wandering. Think of the sudden insights you have while taking a shower, walking the dog or driving a familiar route with the radio off. These are moments when you aren’t actively focusing on a task and yet your brain is still at work in the back ground. Research shows that default mode supports creativity, memory consolidation and cognitive connections. Even short men tal breaks give the brain time to connect “new learning with other previous things you’ve learned,” says Oakley.

One of the most popular attention strate gies is the Pomodoro Technique, something I learned from Oakley five years ago. It’s also simple: Choose one task to work on (unitask ing!), minimize distractions, set a timer for 25 minutes and go. After 25 minutes, take a brain break — step outside and get some fresh air, move your body or just let your brain rest and clear. Then dive in for another 25 minutes.

I’m using this strategy right now. After my disastrous attempt at crafting the introduc tion, I turned on a favorite Pomodoro app — one that shuts down notifications on my phone. I’ve used this app so often in the last few years that my response is Pavlovian: My brain chatter settles down, my anxiety ebbs, my focus sharpens and I am suddenly able to engage with whatever project or article I’ve been procrastinating.

When I teach this strategy to students in study skills workshops (and when they actual ly try it at home) the response has been uni versally positive: “I finished my homework in half the time it usually takes me” or “I got a draft of my college essay written in 25 minutes after dreading it for weeks.”

Perhaps one of the reasons the Pomodoro strategy works is because it prompts us to de liberately turn off the ubiquitous buzzes and beeps that fill our lives.

Nina Kraus, director of Brainvolts laborato ry and author of “Of Sound Mind: How Our Brain Constructs a Meaningful Sonic World,” says that sound has a profound effect on who we are and how we think. Unwanted sounds — aka noises — have “clear consequences to our ability to remember and pay attention.”

That’s because sound is our body’s alarm system and has been throughout our

evolutionary history, says Kraus. Think of how alert we become when we hear an unexpected thump at night. We are suddenly flooded with stress hormones that sharpen our senses and get us ready to act. Now think of all the sound alerts on your devices — the buzzes we com pulsively check, just in case it’s important.

When “we are constantly notified and alarmed, we cannot keep our minds on a single thought,” says Kraus. All of these seemingly benign auditory notifications can keep us — and our digitally connected children — in a “mild state of stress.” Is it any wonder our at tention battery is constantly drained?

“When you leave the walk, those attention al resources are more refreshed for think ing carefully about the problem that you’re grappling with.” Even looking at pictures of nature scenes can be restorative, says Kross. “I have changed the way that I walk to work, and I’ve changed the way I decorated my of fice based on this work.”

Nature also helps calm another attention-drainer: mental chatter, or that voice in our head that catalogs our worries, woes and to-dos. “When chatter consumes our attention, it leaves little left over to do other things including managing our feel ings. And oftentimes the tools that we use to manage our inner voice are effortful and take focus to implement,” says Kross.

The task for parents is not only to reduce unwanted noise, says Kraus, but to also am plify the “positive sounds in our lives”: undis tracted conversations with loved ones, music, bird calls or the crunch of leaves.

The sights and sounds of nature are not just enjoyable, they can also serve as attention “battery chargers.” That’s the idea behind At tention Restoration Theory, says Ethan Kross, a neuroscientist and author of “Chatter: The Voice in Our Heads, Why It Matters, and How to Harness It.” Put simply, kids and adults can focus more effectively after spending time outside. Nature is a cognitive tool that is “hidden in plain sight,” says Kross. “Nature restores attention.”

So how does it work? “When you go for a walk in a green space, you’re surrounded by stimulating sights like trees and bushes and flowers. They capture your attention, but they do so in a very soft and gentle way,” says Kross. This is called “effortless atten tion”: Nature stimulates the brain without taxing it, restoring our capacity to focus.

Time in nature calms chatter by evoking awe, an emotion with strong mental health benefits. Awe helps us zoom out and broaden our perspective, says Kross. “You feel smaller when you’re contemplating something vast and indescribable — and when you feel small er, so does your chatter.” He points to the pictures NASA has released from the James Webb Space Telescope. “Every dot is a galaxy. It’s mind blowing. In comparison, how conse quential is the chatter I experienced earlier today because my daughter and I got into a lit tle argument about cleaning up in the house? Multiple galaxies or the condition of the living room? Awe broadens us.”

I know what it’s like to feel attentionally tapped-out, distracted by headlines, work demands, overflowing inboxes, health scares and the endless practical minutiae that comes with raising kids. And I also know that if my kids need one thing from me, it’s my atten tion — not constant hovering, but at least a few minutes a day of undistracted, positive attention. No multitasking. Phone down. Doing something that fills them up without interjecting: “So what’s your homework to night? Did you put your clothes away? Don’t forget to …”

Last night, this looked like a short eve ning walk. It was past bedtime, but both kids ran out to join me anyway. Suddenly, our dog found a frog in the yard, and we all spent several minutes watching the frog’s hops and our pup’s playful pounces under the stars. Then they went to bed, and I set a timer and settled in for a final, focused 25 minutes of writing.

THINK OF THE SUDDEN INSIGHTS YOU HAVE WHILE TAKING A SHOWER, WALKING THE DOG OR DRIVING WITH THE RADIO OFF. THESE ARE MOMENTS WHEN YOU AREN’T ACTIVELY FOCUSING ON A TASK AND YET YOUR BRAIN IS STILL AT WORK.

BY MYA JARADAT

BY MYA JARADAT

From the moment the specter of impeachment was raised against then-President Donald Trump, Republicans warned about precedent. If Democrats were going to use impeachment proceedings to score political points, the thinking went, Re publicans would do the same when they got the chance.

“Democrats weaponized impeachment,” Texas GOP Sen. Ted Cruz said earlier this year on his podcast, “Verdict with Ted Cruz.” “They used it for partisan purposes to go after Trump because they disagreed with him. And one of the real disadvantages of doing that … is the more you weaponize it and turn it into a partisan cudgel, you know, what’s good for the goose is good for the gander.”

With the prospect of winning back the House in this month’s midterms, Republicans are amping up plans to investigate the Biden administration. Among their concerns: the crisis at our southern border, Hunter Biden’s business dealings and the withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Already, Republican Rep. Blake Moore, of Utah, introduced the Afghanistan Account ability Act, which requires extensive reports on the intelligence provided to President Joe Biden and other policymakers prior to the “botched withdrawal,” says Moore’s spokes person via email. While language from this bill made its way into the current fiscal year’s National Defense Authorization Act, annu al legislation that sets a budget for military

spending, “Congressman Moore believes we must fully investigate the Afghanistan with drawal when Republicans take the majority,” his spokesperson says.

To a certain extent, these sorts of inves tigations are normal when one party takes control of the House, says James Thurber, a government professor at American Universi ty who led the Center of Congressional and Presidential Studies for over 30 years. “There is a tendency for the out party to have exten sive oversight hearings,” says Thurber. “If we have a divided government — with one party

part of a never-ending election cycle.

Republicans will “use oversight hearings to reinforce the position of the Republican Party on a variety of issues … (and) to help fundraise for the people who run the oversight hear ings,” says Thurber, who points out that cam paign money has flowed into the coffers of the Democrats running the January 6 committee.

While investigations will certainly take up much of the public’s bandwidth, analysts dis agree as to whether they will result in gridlock that impedes policy and legislative proposals. While Thurber believes a Republican mid term sweep will result in more gridlock, Ken Kollman, a political science professor at the University of Michigan, says, “Congress could certainly do many things at the same time; Congress can have investigations and do leg islation. It’s not so much the institution itself that can’t handle more than one thing, it’s more what’s getting the attention of the news and what’s in the headlines.”

in the White House — then the chamber has oversight hearings. If it’s a unified government then they have hearings on what the last gov ernment did.”

Still, investigations and oversight hearings are also a symptom of the “extreme partisanship and polarization” that characterizes our moment, Thurber says, adding that we should also under stand investigations and oversight hearings as

Even in the unlikely scenario that Demo crats keep the House in November, we can still count on investigations. “If the Democrats re tain the House and the Senate, I think we’ll see a lot of investigations into the former Trump administration,” Kollman says. “Investiga tions are a tool of whatever party controls the chambers. It’s both a campaign tool and a form of position taking — you’re trying to do as much damage as you can to your opponents.”

But both the probability and results of an impeachment are less certain. Though

articles of impeachment could pass in a Republican-controlled House — and Repub lican voters would broadly support the initia tive — they are likely to die in the Senate, says Jesse Rhodes, a professor of political science at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, even if the Republicans have a majority.

“I think there would be a lot of concern among Republican leaders in the Senate that this (an impeachment) would be serious overreach and would end up strengthening Biden and the Democrats going into 2024,” says Rhodes.

Noting that it’s unlikely that the Repub licans will take the Senate, Thurber says, “Biden would never be convicted in the Senate whether he is guilty of something or not.”

While data shows that impeaching Biden would appeal to the Republican voter base — with over two-thirds of Republicans sup porting the move according to a May 2022 poll conducted by the University of Massachusetts Amherst — there isn’t a consensus within the party’s leadership as to whether impeaching Biden is the right move in the current polit ical climate, largely because Republicans are mindful of the fact that impeaching Biden in 2023 could backfire in 2024.

“If articles of impeachment were brought in the House, I think Biden and the Democrats would say this is a sign that they’re not deal ing with the interests of the American people. … I think Republicans who have been around awhile, they have memories of this,” says Rhodes, pointing to the fact that the impeach ment inquiry of then-President Bill Clinton actually strengthened the Democrats’ stand ing. In the 1998 midterms, which took place just a month before the formal impeachment proceedings of Clinton began, the Demo crats made historic gains in the House. While those gains weren’t enough to take the House, the story should serve as a cautionary tale to Republicans.

This year’s elections could also be likened to the 1962 midterms, says Richard Neumann, a law professor at Hofstra University who has written about the weaponization of impeach ment. After the Cuban missile crisis burnished then-President John F. Kennedy’s image, the Democrats lost only two seats. “If they lose

two seats this time, they keep the House,” says Neumann.

Though Biden hasn’t been staring down the barrel of warfare on American soil, he has grappled with a pandemic, record-setting inflation, spiraling gas prices and rent spikes.

As of late, there’s also been tensions with Chi na over Taiwan, not to mention the war in Ukraine and Russia’s accusations of America’s “direct involvement” in the conflict. But the administration’s recent legislative victories have given a bump to Biden’s approval rating, which has slowly been on the rise after spend ing more than a year below 50 percent.

In his analysis of the likelihood that the Democrats will win the House, Nate Silver of polling analysis site FiveThirtyEight also notes the parallels between 1962 and 2022, re

base that would be pretty enthusiastic about these kind of hardball tactics and those who want to court more moderate voters.”

Republican leadership, including Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, is “very aware that (impeachment) would play into Democrats’ hands,” says Rhodes.

He adds that when it comes to impeach ment, we could also see some conflict between House Republicans and those in the Senate. “I think we might see some tension between rank-and-file members in the House who can say whatever they want, (because) they chair pretty conservative districts and can still win, and those in the Senate who have to win state wide races.” Already, some Republican can didates who pushed hard to the right to win primaries are facing potential losses in state wide elections, Rhodes says.

So we might see some Republicans tiptoe ing away from populist rhetoric and partisan moves that could prove unpopular, like im peaching the sitting president. And this might mean distancing themselves from Trump, who is increasingly viewed as a liability.

marking that both were characterized by “spe cial circumstances.” Silver, however, doesn’t believe that Covid-19 or a potential war with China or Russia constitutes special circum stances. Rather, “I’m keeping my eye on the potential for a special political circumstance, more like what we saw in 1998, when the pub lic responded to increasing Republican parti sanship and their efforts to impeach Clinton,” he writes.

This is all to say that, even if they do take the House in the midterms, Republicans who have these historical precedents in mind might end up treading lightly when it comes to impeach ment. Republicans “are aware that they have a solid chance of winning in 2024,” says Rhodes, “and they don’t want to mess that up. … I think we’re seeing a tension or conflict between the

With their eyes on 2024, Republican lead ers are trying to assess “what Trump’s stature in the party is going to be, whether he’s going to run, and how damaged he is. … If you look at national opinion polls he’s really damaged goods,” says Rhodes. All of this factors into how Republicans will handle investigations and impeachment.

“It’s a really challenging environment for the GOP right now, and I think a lot of the GOP leadership is trying to figure out where their footing should be.”

As for Cruz’s on-air assertions that “What’s good for the goose is good for the gander,” Cruz is saying what he needs to say to get reelected, according to Kollman, who adds “Ted Cruz will almost surely run for president again; he wants a certain reputation and wants to carve out a particular niche among the Re publican electorate.”

That doesn’t mean Cruz, or other Re publicans will make good on these threats. Because what’s good for one audience in the drama of political theater might not be good for another.

“INVESTIGATIONS ARE A TOOL OF WHATEVER PARTY CONTROLS THE CHAMBERS. IT’S BOTH A CAMPAIGN TOOL AND A FORM OF POSITION TAKING —YOU’RE TRYING TO DO AS MUCH DAMAGE AS YOU CAN TO YOUR OPPONENTS.”

There is simply no other device that provides a low-impact, full-body, time-efficient workout that is as fun and comfortable as an ElliptiGO bike. If you’re a current or former runner, fitness enthusiast or just want to enjoy exercising outside, you’re going to love your ElliptiGO. There’s nothing else like it.

Since president joe biden took of fice, conservative media outlets have sounded a steady alarm about the number of migrants arriving at the southern border. Beginning January 2021, more and more people — in fact, tens of thousands more — started showing up at entry points across the border.

In January of this year, the New York Post declared that Biden was “rolling out the wel come mat” for illegal migrants, “spending our tax money on hotel stays, debit cards and cellphones.” Brietbart cited a report from the Federation for American Immigration Reform stating that the rough equivalent of the entire population of Ireland had illegally entered the United States in Biden’s first 18 months.

While outlets like The New York Times, The Washington Post and NBC continued to cover the issue, immigration didn’t get the same top-of-the-fold attention during Biden’s term.

That all changed in September, when Re publican Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida flew dozens of migrants who recently crossed into the United States from Mexico to Florida. The following day, Greg Abbott, the governor of Texas, sent two buses full of migrants to the residence of Vice President Kamala Harris in Washington, D.C. These publicity stunts, de signed to score points against Democrats in the runup to high-stakes midterm elections, occurred as federal data was released showing that, for the first time ever, more than two mil lion migrants were detained at the border in a single fiscal year.

According to DeSantis, Abbott and a host of conservative pundits, Biden and his policies are

to blame for the surge in immigration. He has “gone full open borders,” the New York Post editorial board declared in August. The Biden administration has “broken the (immigration) system … beyond repair,” Chad Wolf, the for mer acting secretary of homeland security, told Fox News. Simon Hankinson, a senior research fellow at the Heritage Foundation, accused the president and his Secretary of Homeland Secu rity Alejandro Mayorkas of essentially having “decided not to enforce the law,” adding that the current surge in migrants is “90-percent at tributable” to the Biden administration.

happening at the border, which undoubtedly has become a crisis.

The number of immigrant encounters by border officials in the past 11 months may be extraordinary, but the ebb and flow of mi grants has been going on for decades, as has the effort to score political points on the issue. As one expert told me, the fact that immigra tion and border policy are electoral issues at all almost presupposes they’ll never truly be fixed. And yet, as Texas Sen. Ted Cruz tells it, the “problem” of immigration had largely been solved under former President Donald Trump, whose controversial border securi ty policies have been the subject of intense debate, as have Biden’s efforts to undo them. As that debate roils, experts say the evolving nature of migration at the southern border is straining the country’s immigration system to the breaking point. Fixing it may require a fundamental shift in how we think about the people coming here in search of better lives.

Biden and fellow Democrats have also tak en criticism from the left for not living up to campaign promises. That doesn’t help going into the midterms, where Republicans have an edge on the most critical issues of this election cycle, which mostly revolve around the econ omy. A recent poll from Pew Research Center found immigration to be the 10th most im portant issue for registered voters.

But if Republicans take the House as ex pected, the pressure on the Biden adminis tration will only rachet up to address what’s

ENCOUNTERS WITH MIGRANTS by the Border Patrol serve as the most concrete evidence of immigration activity at the southern border. Reports of those incidents dropped precip itously in the wake of the Great Recession, reaching lows under the Obama adminis tration not seen since the early 1970s. They bottomed out to just over 300,000 in 2017, the first year of the Trump presidency. Trump took a hardline stance on immigration during his run for the Oval Office, and it’s been sug gested that his tough rhetoric may have dis couraged illegal border crossings.

The lull didn’t last. In 2019, even as the

“WE CONTINUE TO TRY TO FIGURE OUT NEW WAYS TO DO THE SAME THING, AND IT’S NOT WORKING.”

Trump administration instituted its Migra tion Protection Protocols, known as the “Re main in Mexico” policy, migration encounters skyrocketed to more than double the previous year’s numbers. Since the mid-2010s, migrants at the southern border have increasingly sought to enter the U.S. under asylum, said Theresa Cardinal Brown, managing director of immigration and cross-border policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

Under Title 8, the section of U.S. legal code governing asylum, immigrants claiming politi cal protection from persecution in their home country, after passing an initial screening in terview, are held in custody or allowed to enter the country and stay here while their claims work through the courts. That process often takes several years or more.

Remain in Mexico tweaked Title 8 by send ing asylum-seekers back into Mexico to await their day in court. The policy repulsed nearly 700,000 migrants before Biden suspended it during his first few days in office, to the con sternation of many on the right, such as Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, who hailed the policy as “a massive success.”

After its own journey through the court

system, Remain in Mexico was struck down this summer in a 5-4 Supreme Court ruling. Migrants seeking asylum once again have the legal right to enter the country and establish themselves here while they wait for their cases to be adjudicated, a fact that irks Hankinson.

“Essentially,” he says, “(migrant asylum-seekers) get all the benefits of being U.S. citizens or legal immigrants, but without literally any of the cost, because asylum applications are free. Meanwhile, you’ve got millions of people in the pipeline overseas who have paid their fees, done their medical checks, and they’re waiting their turn to immigrate legally.”

The fact that migrants have to apply for the privilege of asylum by surrendering them selves to law enforcement agents at the border does not necessarily make their method of en try illegal. Rather, and for better or worse, they are trying to make use of a piece of the U.S. immigration system, if not as it was intended, then at least as it has been applied. Since 1980, more than three million migrants have been admitted into the country under Title 8.

WHEN THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC erupted in March 2020, Trump and his legal team found

another immigration enforcement tool in a little-known provision of American health law. Title 42 is a public health order estab lished in World War II to prohibit entry to the U.S. when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention believes there is a serious danger of a communicable disease entering the coun try. Approximately two million migrants have been expelled from the border under the pol icy. This year, roughly equal numbers of mi grants have been expelled by Title 42 as were processed under Title 8.

Biden initially extended Title 42, but has since sought to end the policy. More than 20 states sued the administration to prevent it from doing so. A federal judge in Louisiana granted that injunction in May, and Title 42 continues to be used to expel migrants by the tens of thousands every month.

According to the left-leaning American Im migration Council and experts on both sides of the immigration debate, Title 42 has also inflated the number of migrant encounters at the southern border by between 25 and 50 percent. People expelled under the policy of ten make subsequent attempts to cross. Unless they successfully evade Border Patrol agents,

they’re stopped again, expelled again, and once again added to Customs and Border Protec tion’s tally.

The ACLU and the aid group Doctors Without Borders claim Remain in Mexico and Title 42 have both had a devastating impact on people seeking a better life in America. Immigrants forced back from the border into Mexico often live in squalid conditions. In the first two years of the Biden administration, the nonpartisan Human Rights Group docu mented nearly 10,000 cases in which migrants turned away at the border were kidnapped, ex torted, raped, robbed, tortured and subjected to other violent attacks in Mexico at the hands of cartels, petty criminals and even Mexican law enforcement.

Dylan Corbett, the founding executive di rector of the HOPE Border Institute, says Title 42 often forces migrants to forgo the official processes of crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. Instead, they resort to “less safe” ways of immi grating, he said, adding that policies like Title 42 and Remain in Mexico feed Mexico’s car tels, who have diversified their criminal efforts to include human smuggling and trafficking.

NEARLY ALL OF THE MIGRANTS who show up at the U.S.-Mexico border in recent years have been processed by Customs and Border Pa trol either as asylum-seekers under Title 8, or they’ve been expelled under Title 42. That’s a new development in the history of immigra tion and border security, says Cardinal Brown of the Bipartisan Policy Center. Prior to 2014, and regardless of the number of encounters at the border, the data show, she said, that 90-plus percent of migrants at the southern border were adult Mexicans trying to evade detection and enter the country illegally in search of work. Increasingly though, immi grants—especially the vast numbers of them arriving from the Northern Triangle countries of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador— voluntarily turn themselves over to Border Patrol agents seeking asylum, including more than a million this year. That change in mi gration patterns has strained America's im migration system to the breaking point, says Cardinal Brown.

Since 2014, the majority of migrants at the southern border — including tens of thou sands of unaccompanied children — aren’t coming from Mexico, but from the North ern Triangle. They’re being pushed out by economic insecurity, corrupt governments, violence and rampant crime, all conditions that can be traced back directly to American

influence in the region. They’re being pulled north by the prospects of a better, safer, more prosperous quality of life. In other words, they’re looking for the American dream.

Cardinal Brown says more and more mi grants voluntarily turn themselves over to border patrol agents in order to claim asylum under Title 8. This year, more than a million people have arrived at the border seeking asylum protection. All of them need to first be interviewed to determine the validity of their claims. Many but not all of those claims are granted immigration cases, and all of those cases must be decided in court. According to Cardinal Brown, these changes in migration patterns have strained America’s immigration system to the breaking point.

“Our processes, our facilities, our infrastruc ture; everything that we designed to enforce immigration law at the U.S.-Mexico border was designed for a population that was trying to evade capture,” she says. “They were Mexicans, so we could send them back to Mexico pretty quickly. This change in who is coming, and the fact that many of them are asking for asylum or are unaccompanied children, who have to go through some kind of court process, means that all of these processes, procedures and in frastructure that we designed basically for a quick turnaround, no longer apply, and it has overwhelmed everything.”

At the end of July, the country’s immigration courts faced a backlog of more than 1.8 mil lion asylum cases. The time and effort need ed to initially process those claims has put a strain on CBP’s resources, forcing it to divert agents from their patrols to assist with asy lum screenings. Many of those agents have understandably reached the point of empathy fatigue. They’re cracking, just like the system that employs them. What that means, Cardi nal Brown says, “is that we continue to be in crisis mode. And yet, we continue to try to fig ure out new ways to do the same thing, and it’s not working.”

SHORTLY AFTER HIS INAUGURATION, Presi dent George W. Bush announced his first trip out of the country would be to Mexico. Bush had run on a platform of “compassionate conservativism” and had touted fixing Amer ica’s broken immigration system, a top prior ity as far back as 1999 when he was stumping for votes in California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas.

In February 2001, Bush made good on his campaign promise, traveling to the ranch of newly elected Mexican President Vicente Fox.

They talked up what they had in common, their deep mutual respect and their determi nation to work together to solve border issues.

Six years later, Bush’s immigration reform bill failed, largely due to opposition from members of his own party.

Fast forward to 2008. Then-candidate Barack Obama promised Univision’s Jorge Ra mos he’d send a comprehensive immigration bill to Congress within his first 100 days. That didn’t happen, and by 2016, The New Yorker was taking Obama to task for failing to keep his promises to immigrant families.

The last meaningful reform to U.S. immi gration policy was passed by Congress in 1986. Since then, calls from both sides of the politi cal aisle for reforms to meet the current chal lenges facing the system have come to nothing. Increasing partisanship in American politics likely means any hope for such reform remains dim. In Cardinal Brown’s opinion, Democrats and Republicans have “homogenized around opposite positionings” on immigration, and those stances have delivered some amount of electoral advantage. As she told me, “Once it’s become an electoral issue it’s harder to get people together to pass bills and solve it, be cause if you solve it, then you don’t have that issue to blame the other party about.”

Changes to the country’s immigration and border security policy are more likely to re semble Remain in Mexico and Title 42, tweaks to enforcement and the handling of migrants instituted by executive action rather than con gressional consensus. Hankinson of the Heri tage Foundation would like to see the creation of a new legal authority similar to Title 42 that would allow Customs and Border Patrol to im mediately expel migrants while also providing them a way to register their claims for asylum in Mexico or in their home countries.

Cardinal Brown agrees that processing asy lum-seekers outside of the U.S. would help re duce the number of migrants at the southern border. Among other provisions, she would

like to see expanded work visas to help meet the labor shortage in America, and a quicker process for handling asylum claims.

Dylan Corbett of the HOPE Border Institute says it should be acknowledged that, regardless of the policies America puts in place to pro tect its borders and limit immigration, people will continue to come. They’ll come no matter how grueling the trek, how high the walls, how

administration — who have said that to re duce immigration, we need to address its “root causes” by working to ameliorate conditions in countries people are fleeing, ensuring greater stability there and giving people less reason to leave. Narrowing the gulf between the haves and have nots of the world, however, is a big ask and a heavy lift, especially during a time of mounting global economic challenges. Shortly after he took office, Biden sent a comprehen sive immigration reform bill to Congress that included $4 billion in funding to address the root causes of immigration in Central Amer ica. A year and a half later, the bill remains stalled in a congressional subcommittee.

many agents or drones patrol the border, and no matter how harsh the penalties for trying to cross. They come because something is funda mentally wrong in their home countries. War, violence, persecution, corruption, poverty, lack of services and opportunity. Faced with those challenges, many flee north, pulled by Ameri ca’s promises of safety, stability, freedom, good pay, job prospects, the resources to meet their needs, in short, a better life.

There are many — including Biden and his

It is a near certainty that people will con tinue showing up at the southern border. So, how then are we to respond? Corbett has an idea, but it isn’t a political or legal policy — it’s a moral challenge. He suggests that when people come knocking on the country’s doors, we shouldn’t turn them away: We should wel come them. He lives and works in the border town of El Paso, Texas, and he says, “We’re better people when we welcome the other. We’re transformed by the reality of immigra tion in a positive way. We live that on a human level every day on the border. Immigration has strengthened us and ennobled us and enriched us. There’s nothing to fear.”

As of September, the new record for mi grant encounters in a single fiscal year stands at over 2.1 million, with still a month to go.

THE EVOLVING NATURE OF MIGRATION AT THE SOUTHERN BORDER IS STRAINING THE COUNTRY’S IMMIGRATION SYSTEM TO THE BREAKING POINT.

Take five minutes to experience divine love in a whole new way.

Britta Joslyn was at a breaking point. She’d decided to move out of her house in Heber City, Utah, after a split-up. But, finding a new home proved Sisyphean. She needed to find a rental close to her chil dren’s school that would accommodate her eight-year-old twins and her service dog, but everything was out of her price range. Land lords were asking her to prove she made triple the cost of the rent. She couldn’t. Joslyn is a speech pathologist, a professional that makes $83,000 a year on average. She shouldn’t be in this situation. Right?

Joslyn’s not alone in her struggle. Nearly half of Americans say housing affordability in their community is a major problem, ac cording to Pew Research. Across the country, home prices are now out of reach for median wage earners in 97 percent of counties. This is a significant increase from 2021, when 69 percent of U.S. counties were categorized as historically less affordable, according to the Home Affordability Report from ATTOM, a real estate data firm.

In almost every community you consider, the housing situation is bad. Very bad. Accord ing to Moody’s home price index, home prices nationally have increased 32 percent over the past two years. The National Association of

Realtors reports an even bigger jump of 39 percent. During Salt Lake City’s first phase of the Thriving in Place initiative, which was introduced in July by the Department of Community and Neighborhoods and aims to find solutions to housing displacement, near ly half of respondents knew someone who has already moved due to eviction or high hous

short supply of single family homes stymies homebuyers as out-of-state buyers, foreign investors and developers snatch up property. Tenants who lease can no longer afford in creasing rents, and, priced out of entering the homeowning market, are left with little to no options for housing, especially because the entire Wasatch Front has become increasing ly expensive. According to reports from the National Low Income Housing Coalition, extremely low-income renters in the U.S. face a shortage of approximately seven million homes.

ing costs. Almost 20 percent say they have had to move due to rent increases, while 13 percent are on the verge of moving due to in creased costs. Close to 40 percent of respon dents want to buy but cannot afford a home.

While rent usually increases 3 to 4 percent annually, it’s jumped a stunning 17 percent this year, and 79 percent over the past five years. Even in the face of the cooling housing market, demand is high and supply is low. A