PLUS:

MIKE LEE ON PUBLIC LANDS & RAÚL LABRADOR ON IMMIGRATION

DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE

MARCH

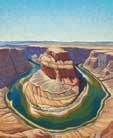

SPECIAL ISSUE STATE OF THE WEST

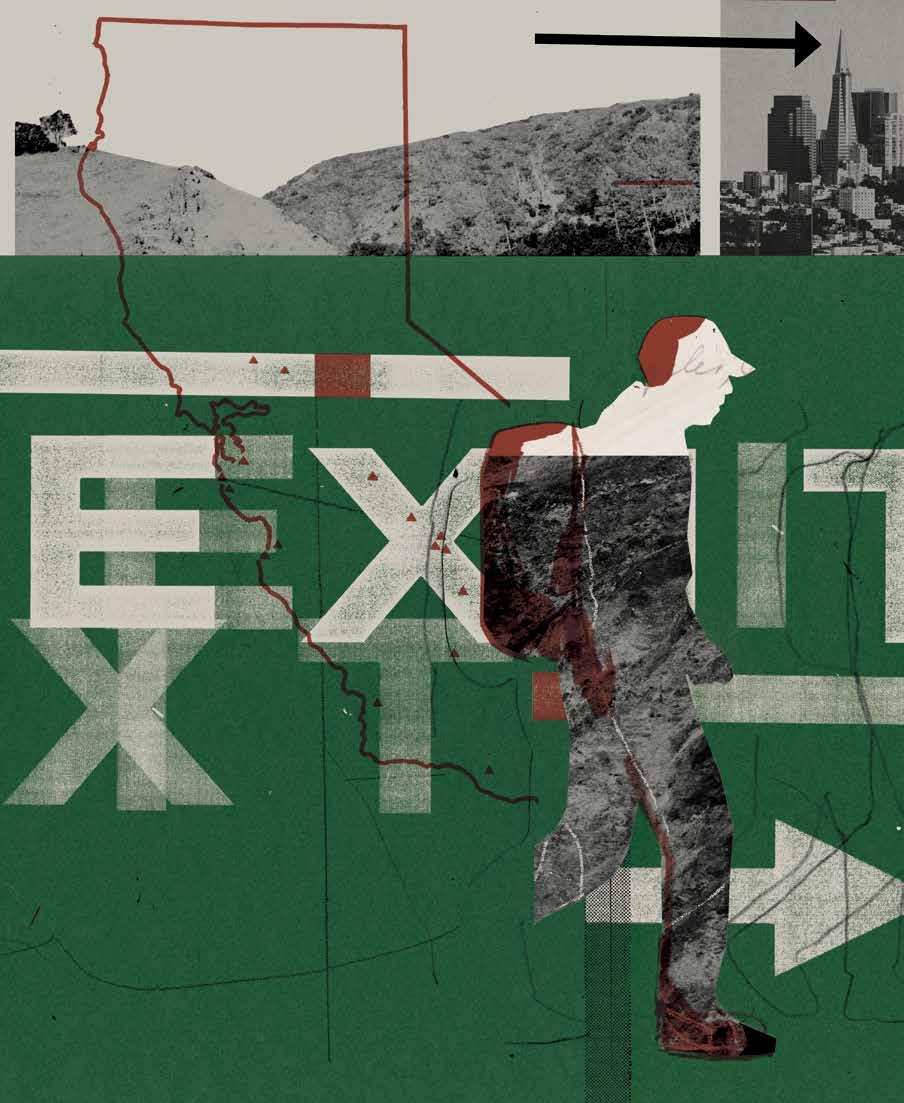

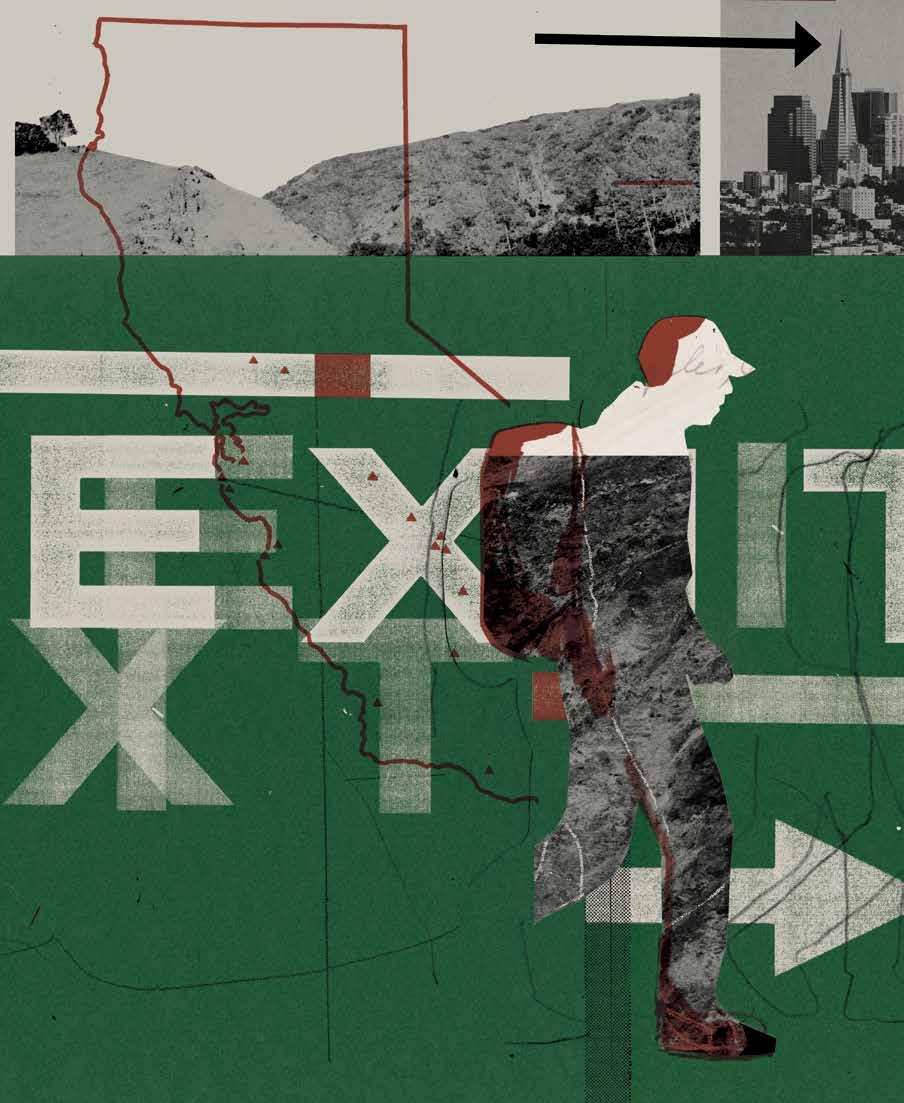

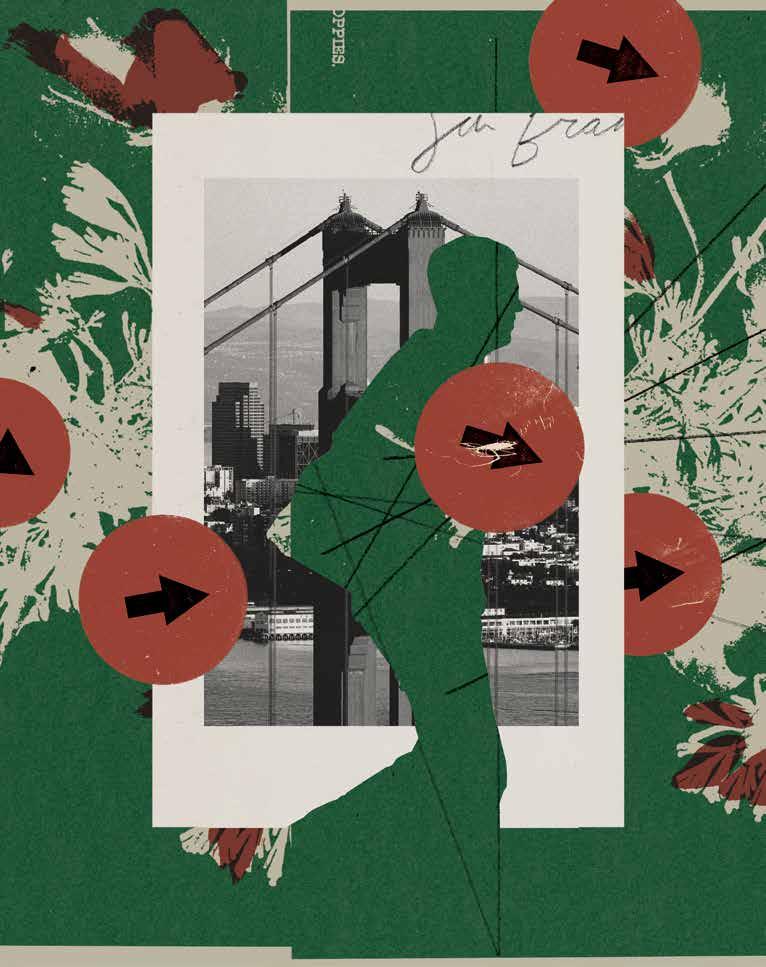

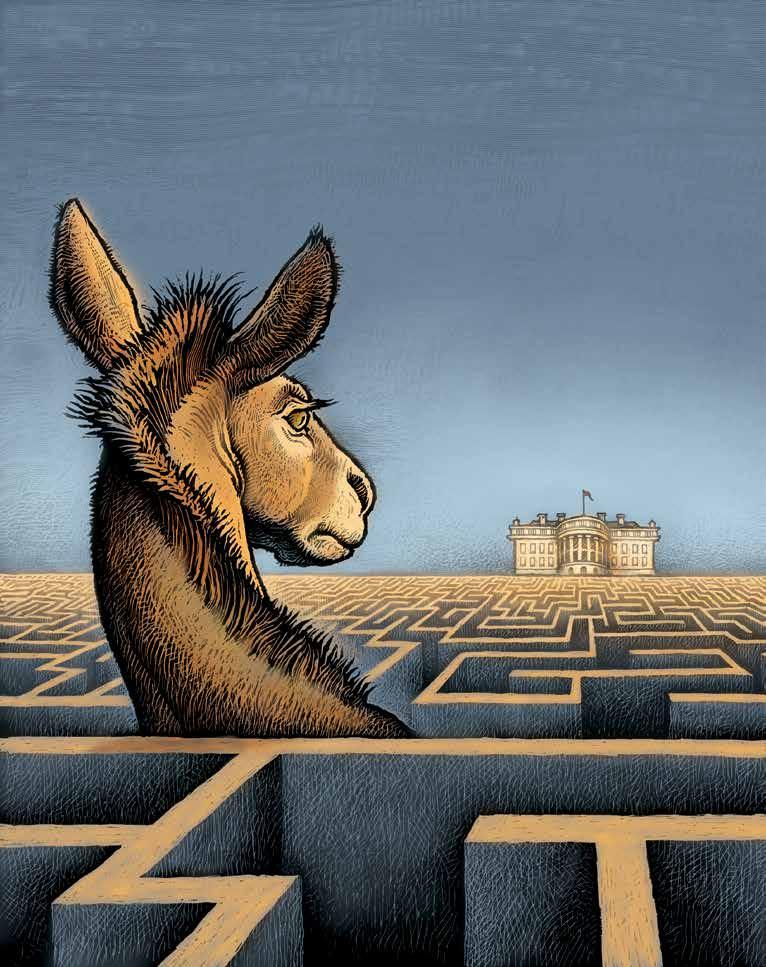

THE GREAT CALIFORNIA EXODUS

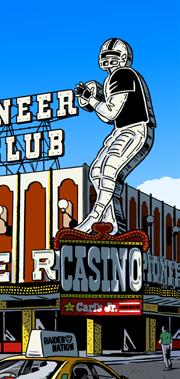

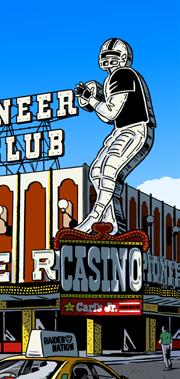

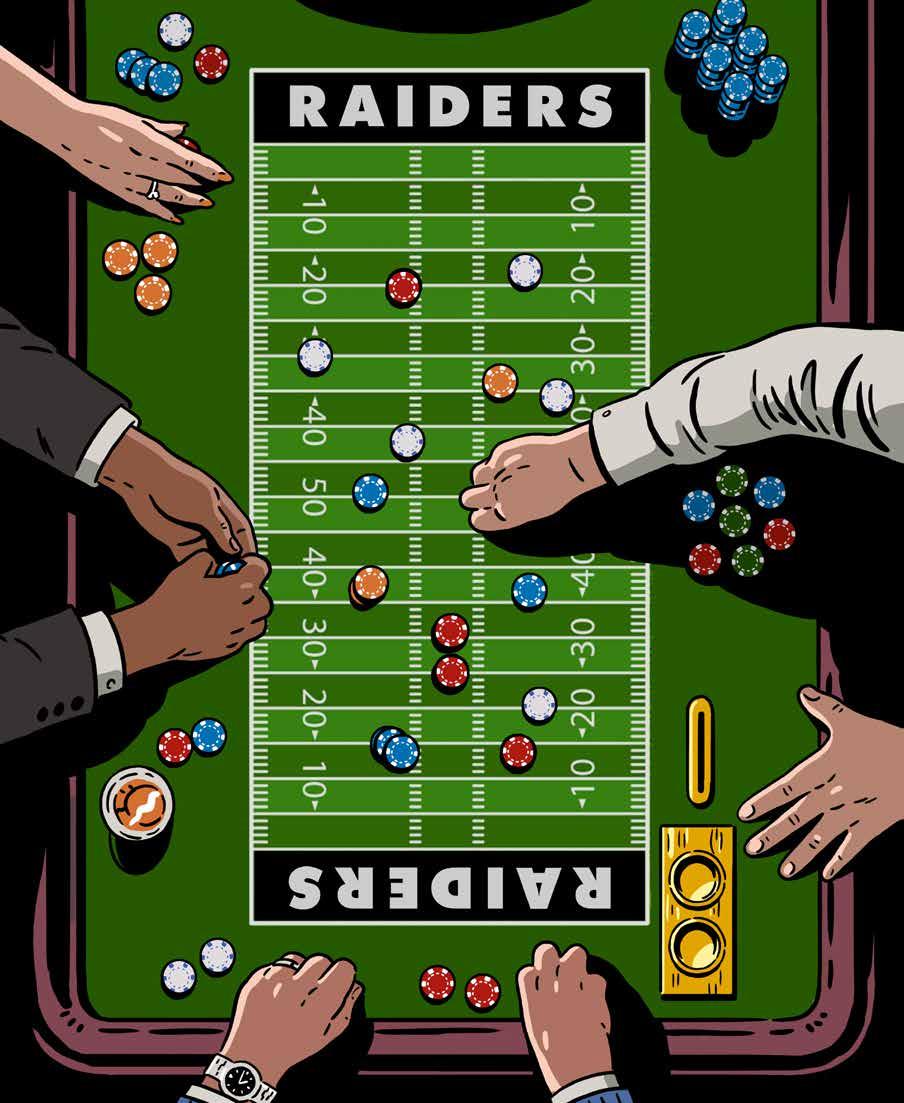

BAD BETS : HOW VEGAS IS TAKING OVER SPORTS

THE OTHER MARCH MADNESS

ALASKA’S MOST REMOTE (AND INSPIRING) BASKETBALL TOURNAMENT

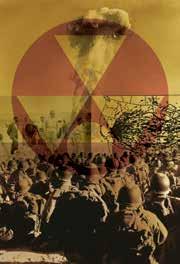

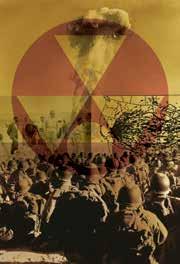

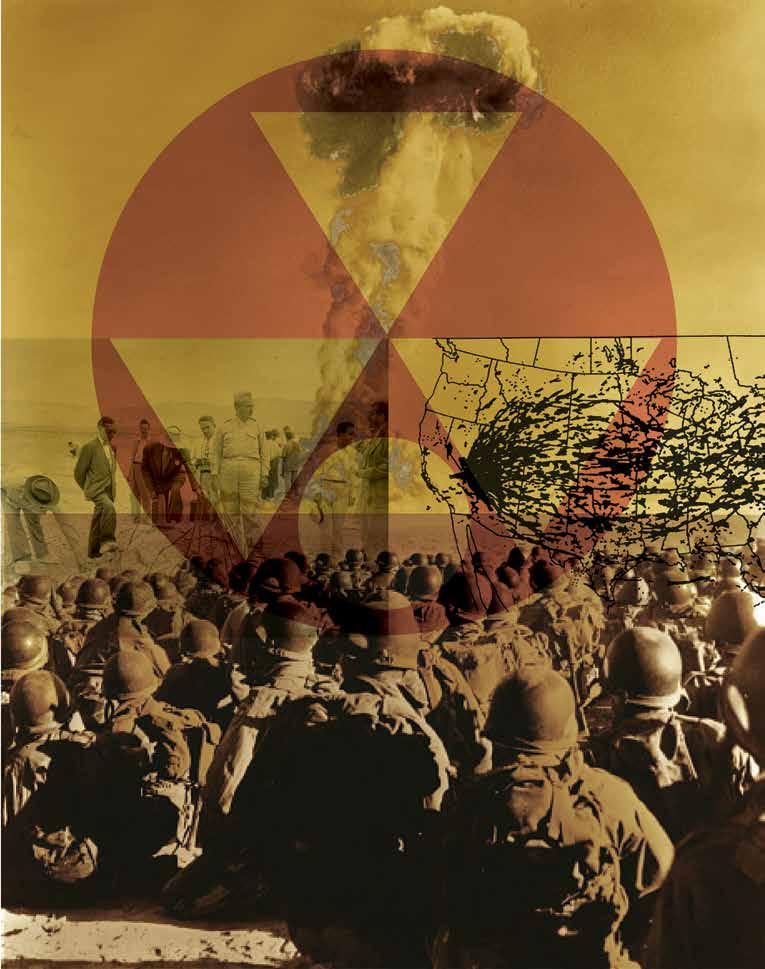

MILITARY SPENDING — BAILOUT OR FALLOUT?

2024

04 | NO 32

VOL

MARCH JULY APRIL SEPTEMBER MAY OCTOBER

“California has remained a beacon of hope to flock toward. Until now.”

THE OTHER MARCH MADNESS

INSIDE ALASKA'S MOST REMOTE (AND INSPIRING) BASKETBALL TOURNAMENT.

by kade krichko

44

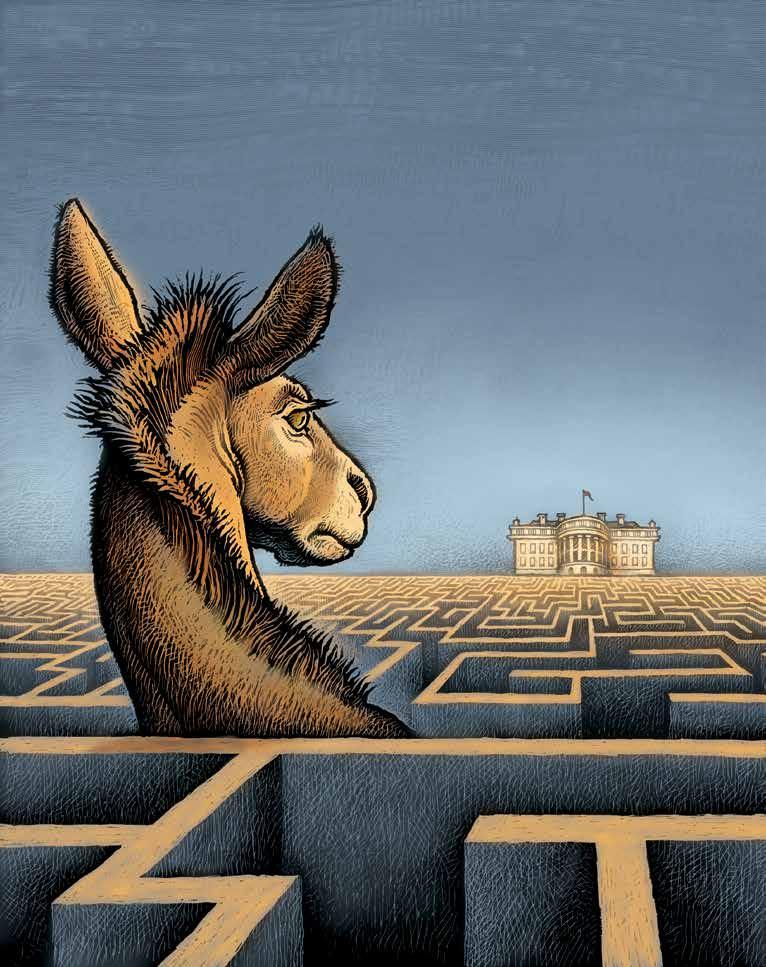

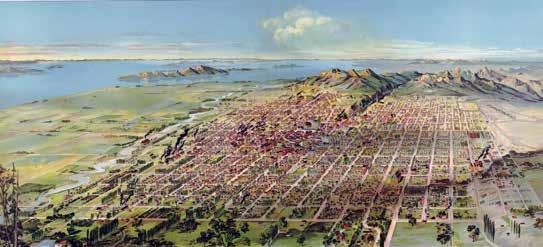

WHAT’S THE MATTER WITH CALIFORNIA?

WHY CRIME, HOUSING AND NATURAL DISASTERS MAY BE SPURRING A MASS EXODUS.

by natalia galicza

54

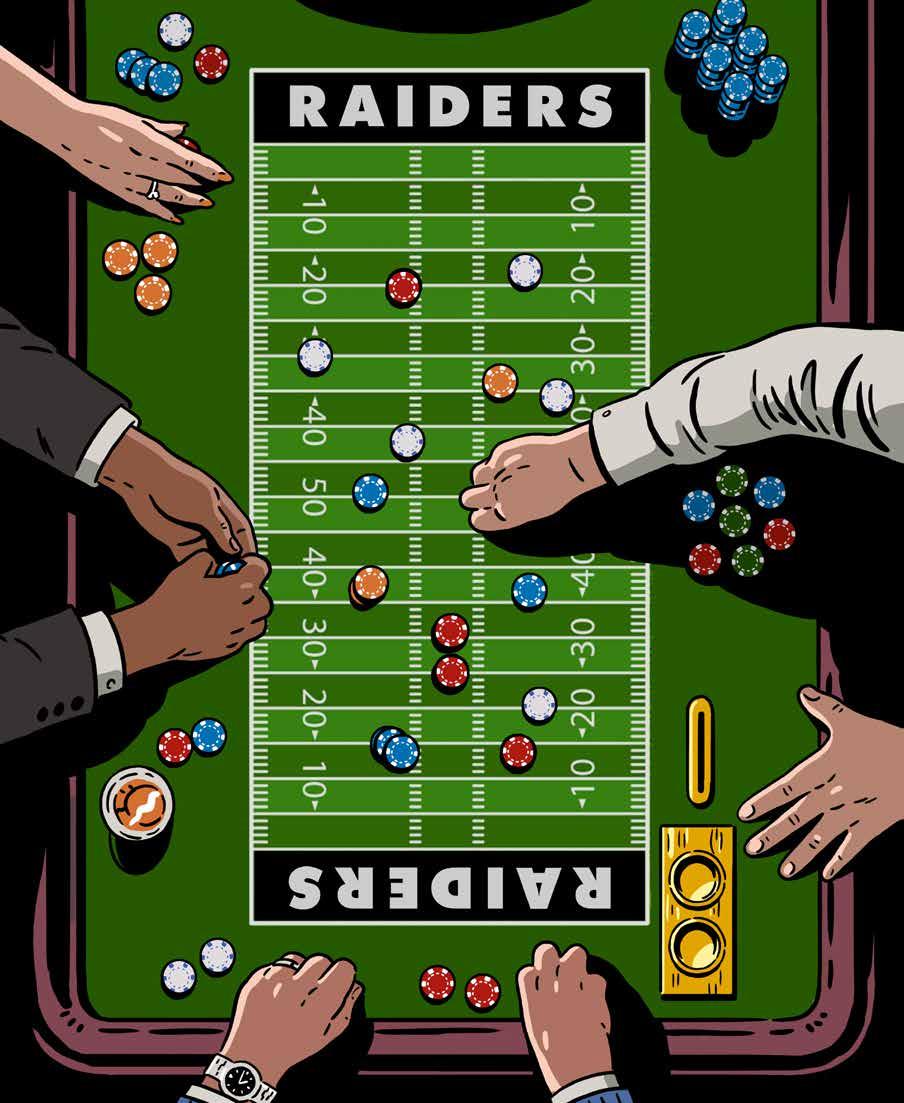

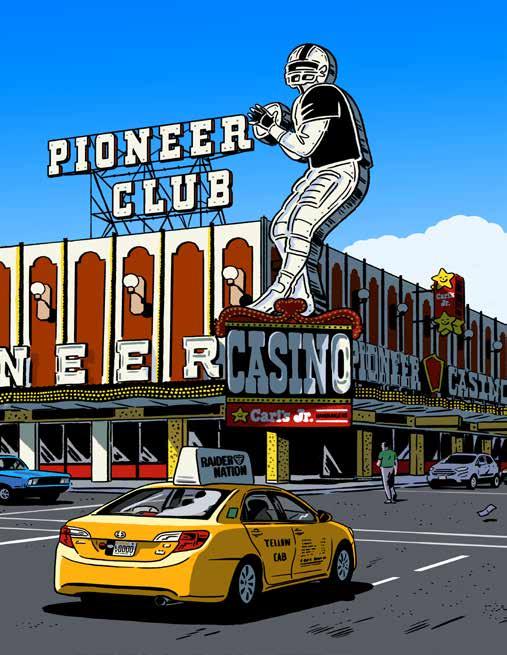

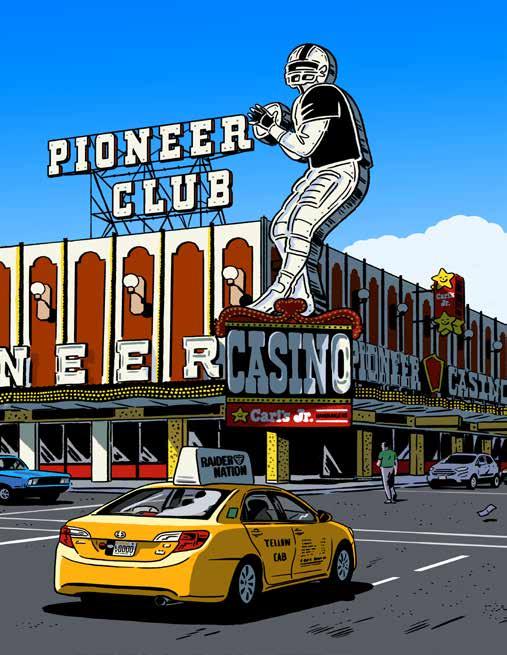

BIG RISKS AND BAD BETS

GAMBLING WAS ONCE TABOO IN SPORTS. NOW IT'S TAKING OVER THE GAME.

by ethan bauer

MARCH 2024 3 CONTENTS

36

ON THE COVER: PHOTOGRAPHY BY COLORMOS

THE

SPECIAL ISSUE

THE STATE OF

WEST

“Faith is the strongest predictor of

MARCH 2024 5 CONTENTS IDEAS CULTURE POETRY THE LAST WORD LETTERS FROM THE FIELD COMMENTARY BREAKDOWN POINT/COUNTERPOINT BEYOND BORDERS The immigration crisis has reached a tipping point. by ra ú l labrador 68 LAND GRAB Citizens, not government, should own the West. by mike lee 15 THE ELITES How Democrats became a party for the jet set. by john b judis and ruy teixeira 62 THE LAST WAR REPORTER In the age of the internet, are foreign correspondents irrelevant? by jane ferguson 30 GOOD ENOUGH An ode to the Costco rotisserie chicken. by natalia galicza 76 REWRITTEN Modern Hollywood comes for the Old West. by ethan bauer 72 ENGLISH by nancy takacs 79 PAY IT FORWARD Teaching financial freedom in disadvantaged communities. by lois m collins 80 COUCH BOUND Why Americans want to talk it out. by ariana donalds 16 RAW DEAL Should Americans subsidize green energy? by megan feldman bettencourt 18

marital

THE WEST SHELL-SHOCKED The military built the West — for better and worse. by matthew brown 24 MODERN FAMILY MARRIAGE MASTERY Is the secret to a happy marriage found in Utah County? by brad wilcox 20

quality”

A foreign correspondent for “PBS NewsHour,” Ferguson authored the national bestseller “No Ordinary Assignment, A Memoir.” Her reporting has been recognized by two duPont Columbia silver batons, a Polk Award and an Overseas Press Club of America Peter Jennings Award, among others. Her essay about the work of a war reporter is on page 30.

Lee is the senior U.S. senator representing Utah. Also a lawyer, he clerked for future Supreme Court Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. on the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals and was general counsel to Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman Jr. A Republican, he serves on the Senate’s Energy and Natural Resources Committee and his commentary on public lands is on page 15.

A Baltimore-based illustrator, writer and designer, Nilson’s work has been published by The Washington Post, Y Magazine, Hardie Grant U and others. In 2023, she received the Award of Excellence from Communication Arts magazine and her work was featured in 3x3 Magazine. Her illustration is featured on page 76.

Teixeira is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. A political demographer and commentator, his writing has been published in The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, National Review and The New York Times. An excerpt from his latest book, co-authored with John B. Judis, “Where Have All the Democrats Gone?,” is on page 62.

Labrador is Idaho’s attorney general and represented the state as a Republican in the U.S. House of Representatives for eight years beginning in 2011. He was chairman of the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration and Border Security and sat on the House Natural Resources Committee. His essay on the immigration crisis is on page 68.

Paterson is a photographer based in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. She works with The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Bloomberg, The Guardian and other publications and commercial clients, including Nike, Apple and Lululemon. Her photography can be seen on page 36.

6 DESERET MAGAZINE CONTRIBUTORS

JANE FERGUSON

RAÚL LABRADOR

ALANA PATERSON

MIKE LEE

RUY TEIXEIRA

LEXI NILSON

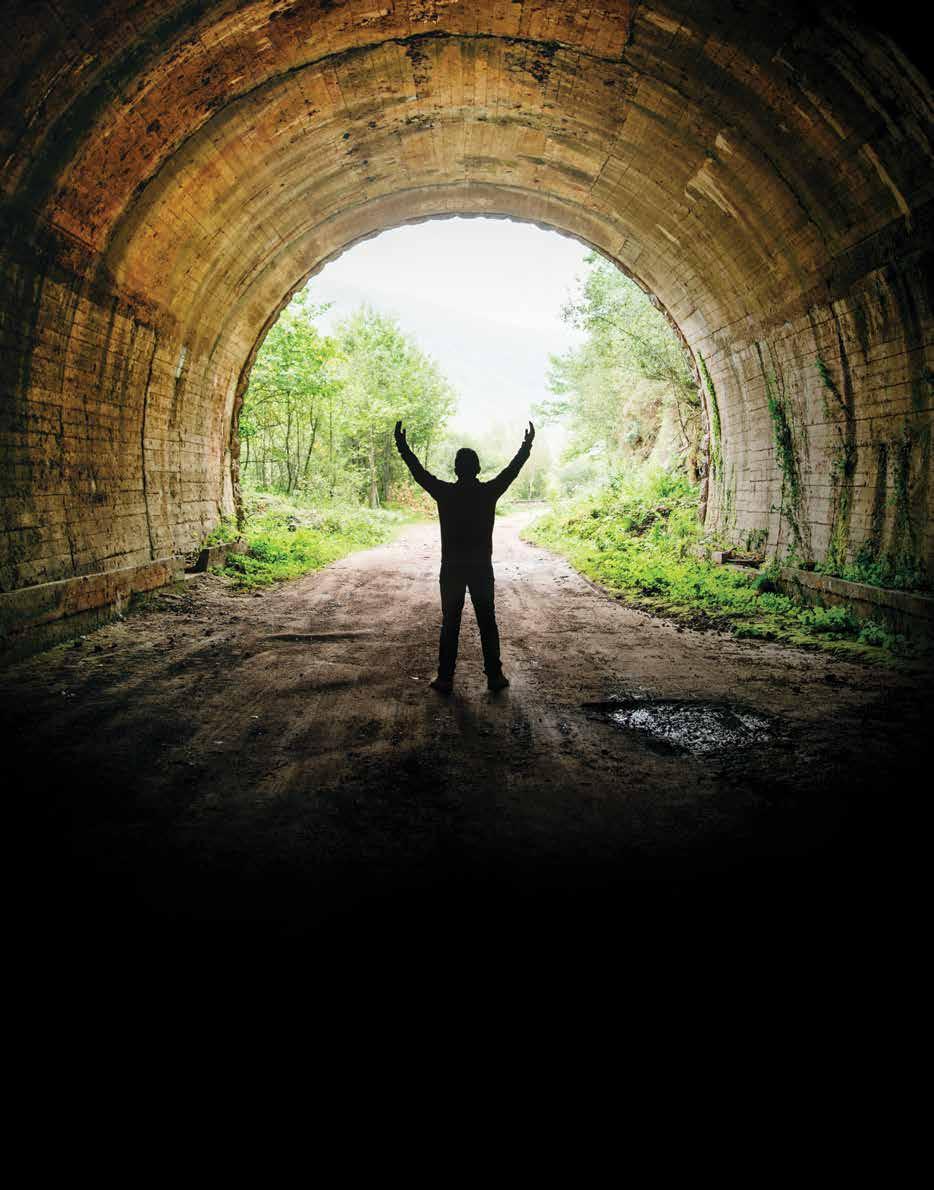

It will get brighter. OPTIMISM

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

HAL BOYD

EDITOR

JESSE HYDE

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

ERIC GILLETT

MANAGING EDITOR

MATTHEW BROWN

DEPUTY EDITOR

CHAD NIELSEN

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

JAMES R. GARDNER, LAUREN STEELE

POLITICS EDITOR

SUZANNE BATES

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

DOUG WILKS

STAFF WRITERS

ETHAN BAUER, NATALIA GALICZA

WRITER-AT-LARGE

MICHAEL J. MOONEY

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

LOIS M. COLLINS, KELSEY DALLAS, JENNIFER GRAHAM

ART DIRECTORS

IAN SULLIVAN, BRENNA VATERLAUS

COPY EDITORS

SARAH HARRIS, VALERIE JONES, CHRIS MILLER, HANNAH MURDOCK, TYLER NELSON

DESERET MAGAZINE (ISSN 2537-3693) COPYRIGHT © 2024 BY DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. IS PUBLISHED MONTHLY EXCEPT BI-MONTHLY IN JULY/AUGUST AND JANUARY/FEBRUARY BY THE DESERET NEWS, 55 N 300 W, SUITE 400, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH. TO SUBSCRIBE VISIT PAGES.DESERET.COM/SUBSCRIBE. PERIODICALS POSTAGE IS PAID AT SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH

POSTMASTER: PLEASE SEND ADDRESS CHANGES TO PO BOX 2220, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH 84101.

DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO.

PUBLISHER

BURKE OLSEN

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER

DAVID STEINBACH

VICE PRESIDENT MARKETING

DANIEL FRANCISCO

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT SALES TRENT EYRE

VICE PRESIDENT SALES SALLY STEED

PRODUCTION MANAGER

MEGAN DONIO

OPERATIONS MANAGER

BRITTANY M C CREADY

DIRECTOR OF CIRCULATION SYLVIA HANSEN

THE DESERET NEWS’ PRINCIPAL OFFICE IS 55 N. 300 WEST, STE 400, SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH. COPYRIGHT 2024, DESERET NEWS PUBLISHING CO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA.

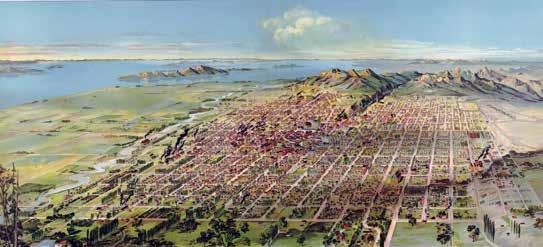

DESERET

PROPOSED AS A STATE IN 1849, DESERET SPANNED FROM THE SIERRAS IN CALIFORNIA TO THE ROCKIES IN COLORADO, AND FROM THE BORDER OF MEXICO NORTH TO OREGON, IDAHO AND WYOMING. INFORMED BY OUR HERITAGE AND VALUES, DESERET MAGAZINE COVERS THE PEOPLE AND CULTURE OF THAT TERRITORY AND ITS INTERSECTION WITH THE BROADER WORLD.

8 DESERET MAGAZINE AWARD-WINNING JOURNALISM ABOUT THE PLACE WE CALL HOME SCAN HERE TO SUBSCRIBE DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE JULY/AUGUST 2023 PLURIBUS DISUNION HOW DID WE BECOME SO DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE AMERICAN EDUCATION THE PATHWAY AN ODE TO THE TRAMPOLINE DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE JUNE 2023 THE FAITH OF MIKE PENCE COLORADO RIVER TIPPING POINT? TWITTER FREE SPEECH ESCAPE UKRAINE THE FATE DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE DESERET MAGAZINE UPC REFERENCE ABBY COX STATE WEST OF THE NAVAJO NATION

FUTURE OF THE WEST

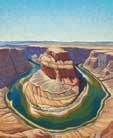

If the Pilgrims had landed in California, the East Coast would still be a wilderness.”

That line is usually attributed to Ronald Reagan, and whether he said it or not, I often quote it (especially to rib a New Yorker) because, well, the Gipper was right. Who would push across a country if you’d already found paradise? A state that can claim the Redwoods and Yosemite, but also Tahoe and Laurel Canyon, Beverly Hills and Disneyland, the Rose Bowl and Hollywood, the Golden Gate Bridge and Pebble Beach — there’s a reason Prince Harry gave up the crown for California.

For many growing up in the West, California is the center of gravity. Families in Utah County plan their summers around trips to Disneyland. If you live on the East Bench, it might be a week in Newport. We may spend the rest of the year complaining about California — its traffic, its crime, its congestion — but on a gray day in February, “California Dreamin’” by the Mamas & the Papas might as well be the soundtrack.

And yet, there’s no denying something has changed. As Natalia Galicza reports in this month’s cover story, 800,000 people left the Golden State between 2021 and 2022.

So, what’s the matter with California?

To answer that question, Natalia drove from the southern end of the state all the way up to Butte County. She visited Los Angeles, where the homeless crisis is so bad that Skid Row now covers 50 city blocks, and to San Francisco, where downtown has become so dangerous that major retailers like Nordstrom and Whole Foods are simply closing up shop.

But the problem extends beyond the major population centers. In the Central Valley — the most productive farmland in the country — concerns about drought and climate change are pushing farmers out. In places like Butte County, the wildfire plague is what’s spurring out-migration.

To be clear, most people who live in California do not want to move, and if they can afford to stay, they will. The question is how much longer the financial costs will outweigh these growing problems, and whether the exodus that began during the pandemic will continue or recede over time.

Of course, there’s more going on in our annual State of the West issue. Sen. Mike Lee explores the debate over public lands and Idaho Attorney General Raúl Labrador offers ideas to resolve the immigration crisis at the border. Staff writer Ethan Bauer travels to Las Vegas to understand how and why gambling has taken over sports. Finally, managing editor Matthew Brown dives into the military’s role in shaping the West — for better or worse.

Ronald Reagan understood that California was more than just a place to visit, and how important the West was to the nation. He also knew that the West — outside a few coastal metropolises — doesn’t get the attention it merits in the national conversation. We believe that’s an ongoing mistake. The West’s perspectives on today’s issues are both distinct and essential. But we also know that for the world to understand who we are, it starts with understanding where we come from. I think the Gipper would agree.

JESSE HYDE

MARCH 2024 9

THE VIEW FROM HERE

“

(844) 222-1967 MINKYCOUTURE.COM

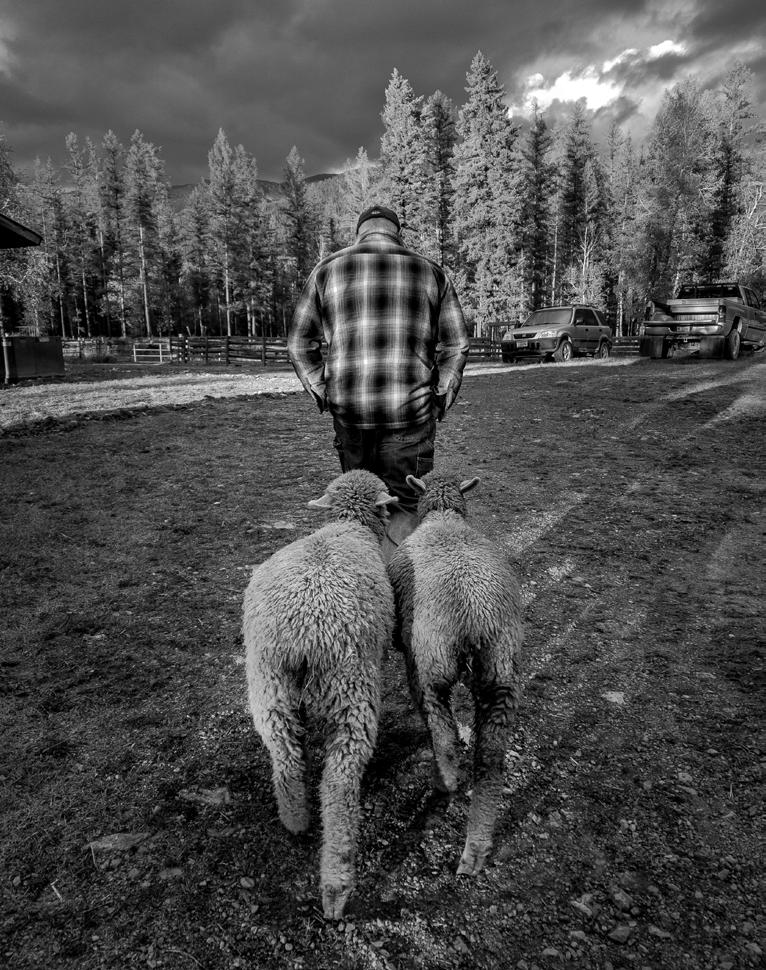

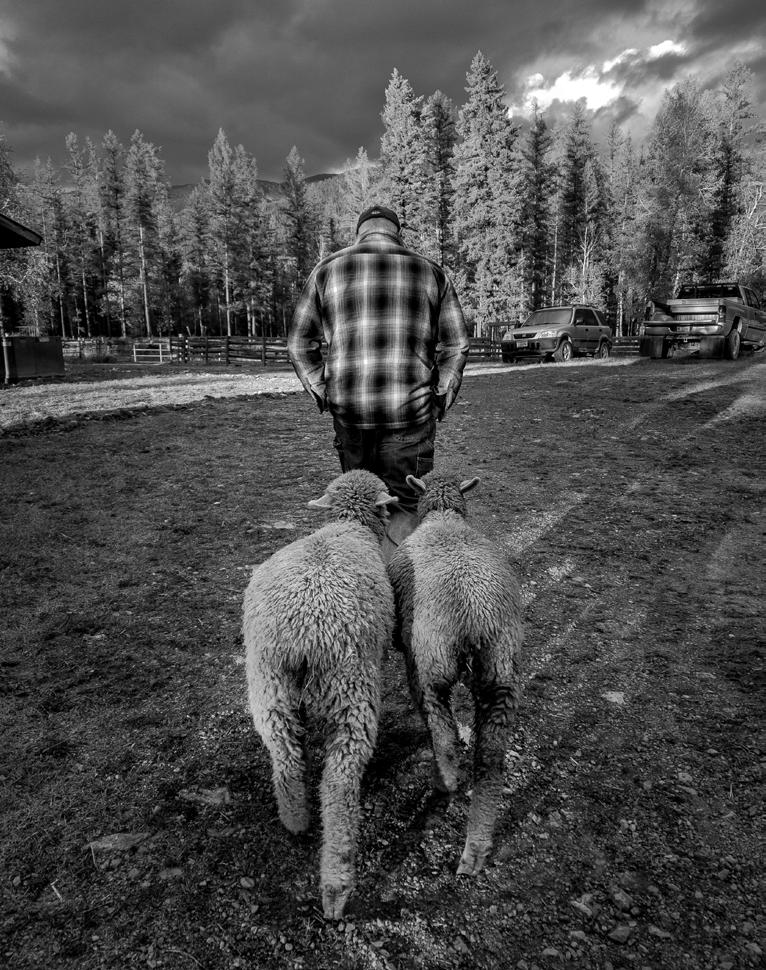

12 DESERET MAGAZINE OPENING SHOT

"PLEASURE CENTER" (ABOVE) AND "FOLLOW THE LEADER" (RIGHT) FROM THE SERIES "RANCH SIGHTINGS (WILD + DOMESTIC)." PHOTOGRAPHY BY LAUREN GRABELLE IN BIG FORK, MONTANA

MARCH 2024 13

LAND GRAB

WHY THE GOVERNMENT SHOULDN’T OWN THE WEST

BY MIKE LEE

Over 175 years ago, Brigham Young and the first company of Latter-day Saints entered the Salt Lake Valley in search of land to practice their faith without interference.

Their pursuit was not unique. Much of history has depended on ordinary people’s ability to have a part of the earth they call their own: a plot of land they can have and hold, “to dress it and keep it.”

Yet, modern-day Utahns and many citizens in neighboring states find themselves singled out and excluded from this basic tenet of the American dream.

They’re excluded by a federal government whose land hoard has grown to encompass a full third of the United States. This vast federal ownership is felt particularly by those in the West. The federal government owns just 4 percent of all land in the United States east of the Rockies. But west of the Rockies, it owns more than half of the land, including almost two-thirds of all land in Utah.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

Section 9 of Utah’s Enabling Act stated that federally owned land within the state “shall be sold by the United States subsequent to the admission of said state into the union.”

Similar language in enabling acts for Missouri, North Dakota and Illinois has been honored. At one point, the federal government controlled over 90 percent of the land in each of those states. Not today. The federal government sold back most of that land decades ago, but Congress has yet to honor its promise to dispose of the federal land in Utah or most of the West.

The Constitution set clear limits on federal land retention. The property clause only authorizes the disposal of land, and the

enclave clause limits federal land ownership only to what is needed for “the Erection of Forts, Magazines, Arsenals, dock-Yards, and other needful Buildings.” Over time, however, the stewardship of federal lands has veered from those principles into an overbearing presence that stifles the lifeblood of local communities.

This shift culminated in 1976, when Congress passed the Federal Land Policy and Management Act. This law completely upended the federal government’s public land policy. No longer would it be the official policy of the United States government to sell back the land, entrusting it to the people. Instead, its policy would be to keep the land, in perpetuity, for itself.

In many respects, this vast federal estate is reserved for the enjoyment of the very few: an elite who want to transform the American West into picturesque tourist villages and uninhabited, but nonetheless beautiful, vistas. They like to say that federal lands are an inheritance for every American to enjoy. But the benefits these elites extol seem primarily to flow their way, while the burdens tend to fall upon the people who live close to those very lands.

The distant elites get their playgrounds in places like Aspen and Moab. They get their rustic cabins, craft breweries, artisanal coffee shops and bed-and-breakfasts.

But what do the actual inhabitants of these locales get?

They get to sell the family farm after generations of ownership because they’re told that the grazing rights their family has enjoyed for generations are now illegal. They watch their children grow up, anxious that they have no future where their families have lived for generations.

The federal government’s stranglehold on the West means our communities can’t fully benefit from the lands surrounding them. The inability to access these lands or collect property taxes stifles local economies and strains public services.

Although programs like payment in lieu of taxes are meant to compensate for these losses, Congress reliably fails to fully fund those programs, leaving our communities to bear the burden of federal land ownership without fair support.

Our immediate task is to rein in the federal government and reclaim a space for ordinary Americans to live and prosper. We must restore the Founders’ vision of localism and self-government. These principles inspired the creation of our communities and fostered the development of the greatest civilization the world has ever known.

As we navigate the future of our public lands, we must remember the individuals, families and towns that are the lifeblood of the West. The conversation must shift to a balanced approach that respects our natural heritage and the needs of local communities. It’s time to reevaluate our stance on federal land management and work toward solutions that uphold the spirit of our Constitution while promoting the well-being of families and the land they call home.

MARCH 2024 15 COMMENTARY

MIKE LEE HAS BEEN A U.S. SENATOR REPRESENTING UTAH SINCE 2011.

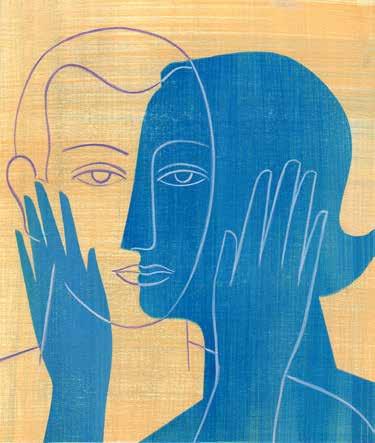

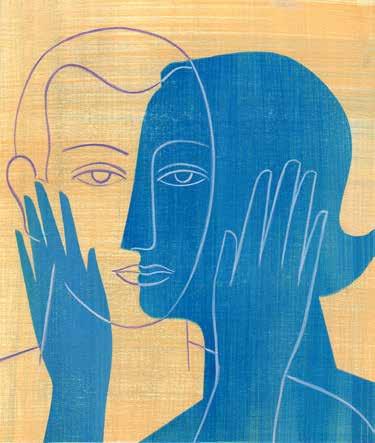

COUCH BOUND

WHY AMERICANS WANT TO TALK IT OUT

AMERICANS HAVE BEEN GOING THROUGH IT. And more than ever before, they want to talk about it. Many find comfort and hope in getting outdoors, being physically active, eating right, sleeping better, engaging in their community or talking to an ecclesiastical leader, but for those who benefit from professional help, the stigma seems to be gone. People brag about getting therapy on dating profiles and social media. They download smartphone apps that promise to help with anxiety, depression, grief or PTSD. Demand is increasing so fast that U.S. senators on both sides of the aisle want to ensure there are enough qualified providers to meet it. How can therapy change America's mental health?

ARIANA DONALDS

1 IN 5 AMERICANS

That’s how many are in therapy now, including about 10 percent more women than men, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and more young people. A recent study from the American Psychological Association found that 35 percent of millennials and 37 percent of Gen Z have received treatment from a mental health professional, compared with just 26 percent of Gen Xers and 22 percent of baby boomers.

WHAT IS IT ANYWAY?

Psychologytoday.com defines psychotherapy as “a form of treatment aimed at relieving emotional distress and mental health problems. Provided by any of a variety of trained professionals — psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers or licensed counselors — it involves examining and gaining insight into life choices and difficulties faced by individuals, couples or families.”

Talk therapy is often used alongside psychotropic medication.

A DISMAL TOP 5

Depression, anxiety, relationships, addiction and sleep issues are the

biggest factors driving people to seek therapy. But studies also link these issues to news headlines. A 2018 APA survey found that 75 percent of respondents aged 15-21 said that mass shootings are a significant source

of stress. They were also concerned about immigration policies like deportation and family separation (57 percent to 45 percent) and sexual harassment and assault (53 percent to 39 percent).

16 DESERET MAGAZINE THE BREAKDOWN

REAL TALK

Psychoanalysis is the talking cure you see in old movies, involving long years of committed therapy with a certain provider, delving into past experiences and unresolved emotions to understand “the influence of such unconscious forces as repressed impulses, internal conflicts and childhood traumas on the mental life and adjustment of the individual,” according to the APA. It has been effectively used to treat depression, anxiety and borderline personality disorder, among others.

“IT IS STILL LARGELY AN UNREGULATED FIELD. THERE’S LICENSING FOR PSYCHOLOGISTS, PSYCHIATRISTS, SOCIAL WORKERS, LICENSED COUNSELORS. BUT THE TERMS PSYCHOTHERAPIST AND COUNSELOR ARE NOT LEGALLY REGULATED IN ANY STATE.”

JOHN C. NORCROSS, CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF SCRANTON WHO FOR 45 YEARS HAS RESEARCHED THERAPY’S EFFECTS ON AMERICANS

PROBLEM SOLVING

Cognitive-behavioral therapy, or CBT, is focused on practical tools for coping with emotional issues. Patients learn to recognize faulty thought patterns (e.g., this failed so it will never work) and replace them (this has worked before, it just didn’t work this time). They also learn to better understand the behaviors of others and practice mindfulness to seek calm in the storm. CBT can help with a broad range of issues, like chronic pain, ADHD, eating disorders and even schizophrenia.

10 SESSIONS

That’s about all it takes for a short-term therapy cycle these days. Fifty years ago, the same results could require up to 40 sessions. There are now reliable treatments for problems that were once difficult to handle, like trauma, panic disorder and

obsessive-compulsive disorder. Not only is this more cost-efficient, but the decreased time commitment makes it easier for patients to follow through.

10,000 SHORT

That’s the national deficit in mental health care providers forecast for 2025, according to the Department of Health and Human Services. Forty-seven percent of Americans already live in a “mental health workforce shortage area,” according to KFF, a health policy research group. Texas, California and Florida face the gravest shortfalls; Nevada and Arizona rank 12th and 13th, respectively, while Idaho ranks 34th and Utah 35th. Telemedicine may help, and some communities are even training barbers to pitch in.

I, ROBOT

I, ROBOT

Some are excited to incorporate artificial intelligence into mental health care, as a complement to trained professionals. Skeptics may cringe, but the APA believes AI can automate administrative tasks, help train new therapists and use chatbots to streamline treatment, making therapy “more accessible and less expensive.” AI may even start listening in on sessions, tracking symptoms and highlighting themes for practitioners to review.

8 YEARS A POSTGRAD

Training for therapists varies, as do their titles. A counselor or licensed clinical social worker might start with a master’s program in psychology, marriage and family therapy or counseling, followed by three to five years of practice and a successful licensing exam. Psychiatrists can prescribe medication, so they must complete four years of med school and four more in residency.

MARCH 2024 17

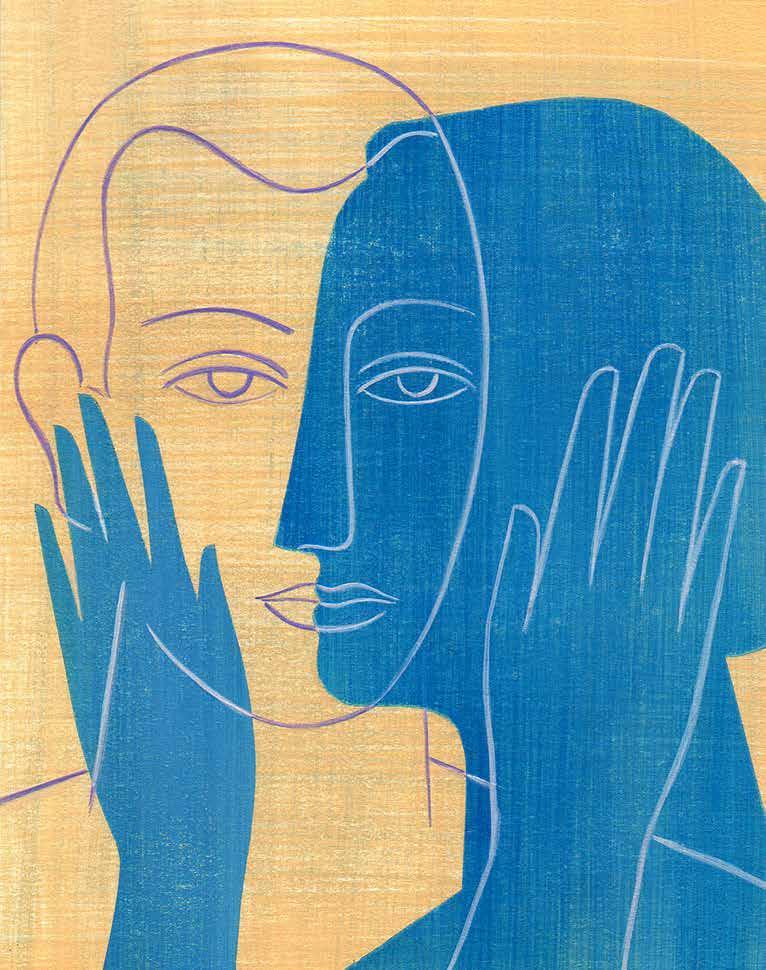

ILLUSTRATION BY ANDR É DA LOBA

RAW DEAL

SHOULD AMERICANS SUBSIDIZE GREEN ENERGY?

AS THE PACE AND SCALE of natural disasters increase and scientists continue to sound the alarm about the warming climate, Democrats are calling for grand reinventions of America’s energy industry. Through programs like the Green New Deal, they aim to increase subsidies for renewable energy sources like wind, solar and hydroelectric to avoid the most catastrophic effects of climate change. Opponents and GOP leaders deride that approach as an economic wrecking ball. While some still dismiss the scientific consensus on human-caused warming, even Republicans who prioritize this issue fear that building a new industry through a government expansion is the wrong move for America.

M

EGAN FELDMAN BETTENCOURT

18 DESERET MAGAZINE POINT / COUNTERPOINT

AN EXISTENTIAL THREAT TRUST THE MARKET

CLIMATE CHANGE is an existential threat to life as we know it. Humanity has never faced a more urgent task than the race to reduce the consumption of fossil fuels in order to stem the catastrophic rise in worldwide atmospheric temperatures, and that requires a dramatic shift in how we think about the economy. The only way to quickly replace oil and gas with renewable energy sources is through government action as sweeping and transformative as the country’s responses to other cataclysmic events, such as the Great Depression and World War II.

Subsidies are not a new idea. The federal government has invested in the development and distribution of new energy sources since the start of the republic. A Yale study found that the oil and gas industry received more government funding in inflation-adjusted taxpayer dollars at its early stages of development than green energy does today. The U.S. still spends billions of dollars each year on fossil fuel subsidies, money that should now be redirected to renewable energy sources.

“We need to phase out fossil fuels completely,” says Martha Molfetas, a senior fellow at the think tank New America. “Renewable subsidies will increase our energy security, reduce air pollution and avoid the negative water and soil impacts that fossil fuels have caused over the past 100 years.”

Tax incentives like those included in the Inflation Reduction Act are a form of support that can also help renewable energy developers to get up and running faster and at a lower cost. This in turn can help consumers to make costly initial investments in retrofitting their homes, such as installing solar panels and heat pumps. Like any government investment in new industries, this will result in more people entering the renewables market, increasing the use of these technologies, creating jobs and growing the economy.

TAX CREDITS and other subsidies mean large expenditures of money. And that money must come from raising taxes, increasing the federal debt, or both. “Green energy subsidies will be financed with still more government debt,” says Jonathan Lesser, an adjunct fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank. “In another five years, the interest on debt could be the largest item in the government budget.”

Not only will subsidies hinder private investment in new energy sources, they won’t even make renewable energies more affordable. According to The Wall Street Journal editorial board, “the government-forced green energy transition” has driven up prices for wind and solar manufacturing parts by artificially increasing demand — and those costs will be passed on to consumers.

Instead, the U.S. should unleash the power of the free market to reward innovation. Eliminating dependence on government would incentivize clean energy technology leaders to compete for private capital and market share by coming up with better solutions at lower costs. “Two wrongs don’t make a right,” Lesser says, acknowledging the government’s historical support of oil and gas. “The idea that you can subsidize your way to economic growth is a fantasy.”

Another fantasy is the idea that we can reach net zero by replacing fossil fuels with wind and solar alone. Nuclear should be part of the mix, as it is in countries like France and Finland. Small modular nuclear plants could be a meaningful part of a diverse energy mix that helps us decarbonize the economy — especially if industry leaders are incentivized by the market to keep creating cleaner, safer forms of nuclear power.

MARCH 2024 19 ILLUSTRATION BY JEAN-FRANCOIS PODEVIN

MARRIAGE MASTERY

FAITH, UTAH COUNTY AND THE SECRET TO A HAPPY MARRIAGE

BY BRAD WILCOX

Everyone wants to know the surefire secret to success at love and marriage. That’s why the local Barnes & Noble aisle on relationships is packed with books full of tips on how to win at love. One of the better offerings in this department is psychologist John Gottman’s bestselling book, “The Relationship Cure: A 5-Step Guide to Strengthening Your Marriage, Family, and Friendships.”

The book is based in part on wisdom Gottman gleaned from observing hundreds of couples at his “Love Lab” at the University of Washington in Seattle to determine what goes into strong and stable relationships. Based on his research, he advises couples to do things like steering clear of what he calls the “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse”: stonewalling, defensiveness, criticism and contempt. There’s a lot to learn from his research.

However, Gottman is focusing on what might be called the “microclimate” of an individual marriage — the discrete interactions that make for a good or bad

relationship. As a sociologist, I am interested in studying the wider contexts, the “macroclimates,” in which strong and stable marriages thrive. Why is it that the picture-perfect Laurelhurst community near his Love Lab has lots of stable fami-

THE QUALITY AND STABILITY OF MARRIAGES ACROSS THE LAND ALSO MATTER FOR THAT UNIVERSAL QUEST: THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS.

lies and a Seattle neighborhood just several miles south of his lab is dominated by single parents? And what explains why marriage is strong in some communities and weak in others across the nation?

Part of the sociological answer to these questions is about money. Marriage tends

to be stronger in neighborhoods where the cash flow is better, neighborhoods like Laurelhurst where there is less poverty and more affluence. Higher-income neighborhoods are dominated by two-parent families — about 80 percent of the families with children. Lower-income neighborhoods, by contrast, are places where almost 50 percent of the families are headed by single parents. That’s in part because financial stress and unemployment — especially on the part of men — are major drivers of relationship discord and divorce.

BUT MONEY ISN’T the whole story. Culture also matters. When we look at counties across the United States, one cultural factor shaping family life zooms into focus: faith.

Consider, for instance, Utah County, Utah, which has the highest proportion of married families of any midsize-to-large county (more than 50,000 people) in America. In recent years, the county has prospered in part because it has attracted

20 DESERET MAGAZINE MODERN FAMILY

MARCH 2024 21 ILLUSTRATION BY

SANDRA DIONISI

FAITH IS THE STRONGEST PREDICTOR OF MARITAL QUALITY WHEN COMPARED TO OTHER FACTORS LIKE IDEOLOGY, EDUCATION, RACE AND INCOME.

a number of California companies — from Adobe to Intel — and midwifed a number of startups seeking out its highly motivated workforce and favorable tax burden. Still, those living there are not in the upper echelons of America when it comes to income: The median household income was around $77,000 in 2021, which positions it solidly in a middle-class bracket. What really makes this county stand out is the faith factor. The population is predominantly members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

But Utah County is not an outlier. When we look at the midsize-to-large counties with the most children living in a married family, the most religious counties in the country are disproportionately likely to make the list. Utah County is No. 1 on this family indicator, and the second most religious county in America — measured by the share of adults who report a religious affiliation. But outside of Utah, places like Williamson County in Tennessee, which has lots of churchgoing evangelical Protestants, and Geauga County in Ohio, which is 20 percent Amish, also land on this list. Of these top 10 counties, half are among the most religious places in the nation (in the top 25 percent for religious affiliation in the nation). Clearly, then, religion is one factor at the county level when it comes to family stability.

IF WE LOOK above and beyond neighborhoods and counties, nationally representative surveys identify four groups that stand out for being masters of marriage — those who are most likely to get married, steer clear of divorce court and forge reasonably happy unions.

The first group is the Faithful. I use the term loosely to refer to those Americans who attend worship services several times a month or more. Their ties to their local religious communities endow their marriages and family lives with deep spiritual significance.

Fellow adherents can provide practical, social, emotional and even financial support when called upon. They are most likely

to believe, on principle, that the institution of marriage is good for the well-being of kids, communities and the country.

The second group is the Conservatives. This group embraces classic American middle-class, or what scholars call “bourgeois,” values — like education, hard work, financial success and personal responsibility — as well as “traditional” values like the importance of religion, marriage, sexual fidelity in marriage and the idea that men and women are inherently different. Today, for Conservatives who are and are not religious, their commitments to more traditional beliefs about family, sex and gender are also shaped by conservative media, public intellectuals and friends.

The third group is Strivers. This group also embraces “bourgeois” values and tend to more likely take the long-term view and embrace delayed gratification. Strivers largely dominate the professions, the business world, the universities and the media. Even though many hold fashionably liberal views about family matters — including politically correct attitudes about family diversity and single motherhood — they do not put these views into practice in their own private lives.

The fourth group is Asian Americans, who also tend to embrace Striver-style values and “are the highest-income, best-educated, and fastest-growing racial group in the United States,” as Bruce Drake from Pew Research Center pointed out.

Asian Americans’ devotion to Eastern-style traditional family values is also a big part of their American success story. Their orientation to marriage is rooted in a combination of principle and prudence: Their traditions — be they Confucian, Hindu or Muslim — push them in a family-first direction. And they recognize that stable families give their kids a big head start in their pursuit of the American dream.

STATISTICS IN THE General Social Survey show that these groups are more inclined to marry and stay married. That kind of stability is important, but the quality of married

22 DESERET MAGAZINE

life also matters. After all, a stable marriage is not as valuable for the children or for the adults if the parents are miserable. So, how do these four groups fare when it comes not just to the stability of their marriages but also to the quality of their unions?

Strivers are happier husbands and wives. College-educated husbands and wives are about 5 percentage points more likely to report that they are “very happy” in their marriages, compared to married adults without a college degree. In fact, higher education is the second most powerful predictor of marital quality when we account for key sociodemographic factors in our analyses.

For the Faithful, meanwhile, the data is especially clear. Husbands and wives who attend religious services frequently are about 6 percentage points more likely to report they are “very happy” in their marriages, compared to those who attend sporadically or not at all. In fact, the GSS found that faith is the strongest predictor of marital quality when compared to other factors like ideology, education, race and income.

Conservatives are also happier in their marriages. They enjoy a 6-percentage-point advantage over moderates and a 5-percentage-point advantage over liberals. More fine-grained analyses indicate that the happiest husbands and wives hail from the “very conservative” camp.

The Asian advantage is more modest when it comes to marital quality, at least as Americans. They are only a few percentage points more likely to be in the happiest

FAMILY STRUCTURE WAS THE BIGGEST FACTOR IN PREDICTING POOR KIDS’ ODDS OF REALIZING THE AMERICAN DREAM IN COMMUNITIES ACROSS THE COUNTRY.

wives and husbands club, compared to married African Americans and Hispanics, and they are not happier than married white people. In fact, it is precisely because Asian Americans are more likely to pursue family stability that they are more willing than other Americans to put up with a difficult marriage.

STABILITY AND HAPPINESS in a marriage are not just important for individual couples — they also have implications for the country at large. That’s in part because they can also profoundly impact the lives of the children that come into a couple’s life, and those children represent the future health and prosperity of the country.

When Harvard economist Raj Chetty and his colleagues looked at the factors driving economic mobility for poor children — i.e., their capacity to go from rags in childhood to riches in adulthood — they compared results from one local community to another, in locations across the United States. They found that “the strongest and most robust predictor (of children’s economic mobility) is the fraction of children (in the community) with single parents.” Not income inequality. Not race. Not school quality. Family structure was the biggest factor in predicting poor kids’ odds of realizing the American dream in communities across the country.

The quality and stability of marriages across the land also matter for that universal quest: the pursuit of happiness. Consider

the growing happiness divide in American life. Educated and affluent people have seen their happiness levels dip a bit in recent years, but the “happiness of lower-SES (socioeconomic status) people” has decreased dramatically, according to psychologist Jean Twenge. This means there’s a growing happiness gap between more privileged and less privileged Americans. Guess what is one of the biggest factors explaining our country’s class divide in happiness?

Marriage.

It turns out that the marriage rate is in free fall among our country’s poor and working class. This translates into “less happiness among those with lower SES,” Twenge observed. By contrast, marriage is in much better shape among affluent Americans, which helps explain why they are doing much better in the happiness department.

Research like this tells us that what happens in our hearts and homes doesn’t just matter for our own well-being, it matters for the welfare of our children and country. So, if you’re married, for your own sake — and, indeed, the sake of our civilization — I urge you to find new ways to honor your commitment to love and cherish your spouse and any children you may have all the days of your life.

ADAPTED FROM THE BOOK “GET MARRIED: WHY AMERICANS MUST DEFY THE ELITES, FORGE STRONG FAMILIES, AND SAVE CIVILIZATION” BY BRAD WILCOX.

COPYRIGHT © 2024 BY W. BRADFORD WILCOX. RE -

PRINTED BY PERMISSION OF BROADSIDE BOOKS, AN IMPRINT OF HARPERCOLLINS PUBLISHERS.

MARCH 2024 23

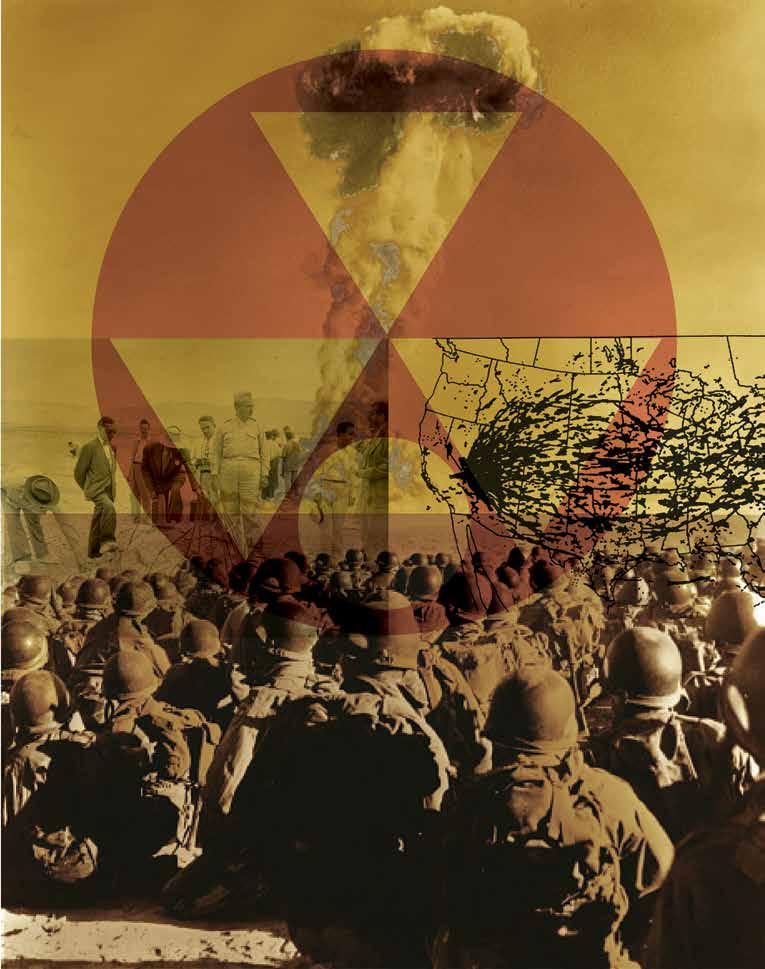

SHELL-SHOCKED

MILITARY INVESTMENT SHAPED THE WEST — THEN CAME THE FALLOUT

BY MATTHEW BROWN

As Tina Cordova perused pages of her hometown paper, Alamogordo Daily News, she came across a letter to the editor sent in from Fred Tyler, a fellow Tularosa Basin native who had returned to New Mexico after 30 years away. “I’m back now and everybody’s sick and dying, and my mom just died,” Cordova recalls reading. “I wonder when we’re going to hold our government accountable for the damage they did to us?”

That question had been festering for years inside Cordova, who is the fourth generation of her family to get cancer since the Trinity test in 1945 — the world’s first nuclear bomb — contaminated the air, soil and groundwater of her remote rural community just 65 miles from the detonation site. She kept a file of newspaper clippings on downwinders from other states who claimed their cancer came from nuclear weapons testing in southern Nevada. After reading Tyler’s letter that day in 2005, she called him and shared the deaths and health problems her family suffered since Trinity.

“We are hard-working, tax-paying patriots,” she says. “My grandfather was killed in Germany (during World War II) and is

buried in Belgium. My family has given a hell of a lot to this. I don’t know what more they want from us. But it’s easy for them to look away from us.” Together, Cordova and Tyler founded the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium that same year, spending the past 18 years fighting for

THE STRUGGLE TO ADDRESS THE HARM FROM NUCLEAR WEAPONS TESTING IS PROBABLY THE HIGHEST-STAKES EXAMPLE OF THE COMPLICATED RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE MILITARY AND THE WEST.

generational downwinders and uranium miners to not just get individual payments of up to $100,000, an amount mandated by Congress in 1990 for victims, but also health care for the illnesses they continue to endure.

For nearly two decades, the consortium

has gathered oral histories of families of survivors. They have evidence that military and government officials dismissed concerns expressed by a few scientists with the Manhattan Project of radioactive fallout poisoning people and the environment. They have proof that no warnings were given to residents living near the test site. Not that it would have mattered much, though, since the fallout reached far and wide. New research released last year by Princeton University’s Program on Science and Global Security shows the contamination from the Trinity blast spread beyond New Mexico to 45 other states, further strengthening the consortium’s appeal to extend a 34-year-old federal program to compensate downwinders in Idaho, Montana, Colorado, Nevada, Arizona, Utah and Guam for harm caused by the radioactive fallout.

The ongoing, difficult struggle to address the harm from nuclear weapons testing is probably the highest-stakes example of the complicated relationship that has evolved over the past two centuries between the military and the West. While the federal government is constitutionally bound to defend the country, the people and the land

24 DESERET MAGAZINE THE WEST

MARCH 2024 25 ILLUSTRATION BY JACOB PLEITEZ

THE WEST

they live on have been hurt in achieving that mission. The conflict is particularly profound in states where the positive impact of a military installation on a local community — infrastructure, jobs, growth, tax revenue, social structures — can obscure the risks of hitching a local economy to a government-operated military installation. That’s the rub throughout most of the West, which was historically explored, occupied, shaped, paved and built by government largesse and the military. But the communities that rely on the economic stability and infrastructure that the military has provided are often the same communities later wracked with consequences that strip the land, water, air and people of their health. It’s a tension that has plagued past generations, and one that will become more fraught as those living in the West continue to weigh the accumulating costs against the economic benefits of contributing to their nation’s defense.

The Senate and House negotiated a defense spending bill that could extend the compensation program Cordova and the consortium are fighting for before it expires in June. But the downwinders, who are the most acute victims, represent a fraction of the thousands of Americans living within the reach of at least 38 military bases in the West that are also EPA Superfund sites — an indication that just containing the contamination, let alone cleaning it up, is billions of dollars and many years away.

Mitigating the damage done through decades of military use of Western lands — and dealing with the dilemma of curbing future damage — has been agonizingly slow for people like Cordova. That will likely not change in the near future. “At the end of the day, I go back to this famous dictum of Immanuel Kant: ‘Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made,’” says Stanford University history professor David Kennedy, who co-edited the book “World War II and the West it Wrought.” “This is the world we live in. There are dilemmas that don’t yield easy solutions. And this is one of them.”

THE U.S. MILITARY has had a presence in the American West for over two centuries, since Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery began its famous expedition into the Northwest in 1804. But that presence expanded dramatically as the nation readied itself for World War II

Beginning in October 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt began withdrawing huge tracts of public lands in the Great Basin, Mojave, Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts by executive orders for defense purposes. Among those withdrawals were 1.2 million acres of the Alamogordo range, where the Trinity Test would take place. Through these executive orders, land condemnation and purchases, the military occupied New Mexico’s isolated Pajarito Plateau, where scientists developed the atom bomb at what is now called Los Alamos National Laboratory. All but seven of the more than two dozen military bases and depots still operating in the Intermountain West were either established or significantly expanded during World War II. By the stroke of a pen, the Department of Defense became a major landlord in the West — controlling more than 17.5 million acres in 10 Western states — and making New Mexico, California, Nevada, Arizona, Alaska and Utah the top six military states in the country today in terms of acreage. “In Utah, the (Department of Defense’s) total acreage exceeds the combined acreage of the ‘Mighty 5’ national parks (Arches, Bryce, Canyonlands, Capitol Reef and Zion) for which the Beehive State is renowned around the world,” University of Pennsylvania historian Jared Farmer writes in an article published in “World War II and the West it Wrought.”

A federal takeover of Western terrain would appear to go against the region’s ethos of resisting government encroachment of the land. But political leaders recognized the economic benefits of the military moving in and privately welcomed the armed forces despite constituent ranchers and farmers complaining about government intrusion. “Out of one side of his mouth he defended the customary rights

of freedom-loving ranchers against the tyranny of big government; out of the other he sweet-talked the military to make sure Nevada got as many bases and government jobs as possible,” Farmer writes of U.S. Sen. Pat McCarran of Nevada, a Democrat who represented Nevada from 1933 to 1954. “In similar fashion, Utah’s elected leaders welcomed the War Department even as they castigated the Interior Department” over other land management disputes.

It wasn’t just political lobbying that prompted the armed forces to look West. The late economic historian Gerald Nash concludes that military leaders were attracted to the sparsely populated, undeveloped expanse of the West because it provided “an inviting milieu for technological innovation and experimentation” with weapons, aircraft and other defense systems. Open spaces were soon spoken for and molded not by private developers, but by the federal government.

In the Cold War era, the government continued to spend, funneling more than $100 billion into Western military installations between 1945 and 1973, according to Nash. The ongoing investment resulted in a new infrastructure of roads, utilities, hospitals and schools to support the growing armed forces presence. For civilians, the lure of the West shifted from wide-open spaces to high-paying jobs with military contractors in electronics, aerospace, communications, engineering and computing. “Military spending rather than market conditions determined the locations of high-tech industries,” Nash says. But changing geopolitics and concerns over deficit spending would eventually curb the downrush of federal funds and force local officials to rethink their economic strategy.

IN THE EARLY 1990s, Mike Leavitt was in his first term as Utah’s governor when local government, business and retired military leaders invited him for dinner at one of their homes in Layton and a meeting on the fate of Hill Air Force Base and other Defense Department assets in the state. Congress had authorized a Base

26 DESERET MAGAZINE

Realignment and Closure Commission to streamline defense spending in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse. BRAC outlined three rounds of cutbacks nationwide totaling $14 billion. Utah escaped the 1991 round. But for the next rounds in 1993 and 1995, the state was on notice that Hill Air Force Base, Defense Depot Ogden, Tooele Army Depot and Dugway Proving Ground were on the chopping block. “It was kind of all hands on deck to come up with a way to respond,” Leavitt, a former governor and Bush administration cabinet member, recalls of the meeting.

Utah wasn’t alone. BRAC jolted neighboring states to make their case to the commission that their beloved military bases were not only essential to the nation’s defense, but also to the survival of their local economies. New Mexico successfully made its case for Cannon Air Force Base, which, along with nearby Melrose Air Force Range, provides 6,413 jobs and more than $400 million in wages and salaries in the small town of Clovis, near the Texas border.

After those three rounds, Utah lost the Ogden depot and part of the Tooele installation, which eliminated a $240 million payroll going to 6,368 employees from those local economies. The Ogden installation was eventually turned into an industrial park and the military truck maintenance plant in Tooele was sold to a Detroit diesel engine manufacturer. But economists say the BRAC process should have been a wake-up call to all state and local leaders about the risk of relying too heavily on defense spending. “If the money keeps flowing, everything can kind of work. But if the money goes away, it’s not like the past history of that money has changed the fortunes of these places,” says Taylor Jawarski, an associate professor of economics at the University of Colorado Boulder.

State officials work year-round to not just increase the defense dollars coming in, but to attract industry adjacent to the mission of the armed forces in hopes of offsetting any economic disruption caused by a military installation scaling back or closing. In New

Mexico, where defense jobs total 18,000 — the state’s 17th largest employer — and defense-related jobs total 52,000, economic developers have leveraged that impact to address education, housing, health care, child care and income tax exemptions to make their communities more attractive to active-duty enlistees and veterans, who can land lucrative jobs at the defense-related research labs or other local businesses after they retire. “A veteran’s income is approximately 164 percent of a nonveteran. So, one of the benefits to creating a pro-military environment is that veterans stay,” spending their incomes locally, says Rich Glover, director of the state’s Office of Military Planning.

BY THE STROKE OF A PEN, THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE BECAME A MAJOR LANDLORD IN THE WEST — CONTROLLING MORE THAN 17.5 MILLION ACRES IN 10 WESTERN STATES.

by playing up its Intercontinental Ballistic Missile maintenance mission and sprawling test and training range neighboring Dugway Proving Ground in the west desert, preserving over 22,000 jobs. Since that time, the state’s congressional delegation has shored up Hill’s future by expanding that base’s test and training range to 2.3 million acres and making the base headquarters for the Air Force’s Sentinel program, a $100 billion initiative to upgrade the nation’s ground-based nuclear missile system.

The program is projected to generate 2,500 jobs to the northern Utah communities surrounding the base. But those taking those jobs will be working and living in an area that has been an EPA Superfund site since 1987 and will remain under that status for at least 50 more years as the Air Force regularly samples the air in residents’ homes for gasses emitted from polluted groundwater, poisoned by decades of chemicals and waste from aircraft maintenance.

Arizona, home to seven Army, Marine and Air Force installations, has set its sights overseas for opportunities that complement its long-standing military presence. The state’s Defense and Industry Coalition recently inked a deal with Ukraine offering defense-related industrial and research resources to rebuild that nation while it’s still in conflict with Russia. And, in Colorado Springs, where the military accounts for 44 percent of the community’s economic activity, officials last year secured the headquarters for U.S. Space Command, which is responsible for providing satellite-based services to the U.S. military and protecting those assets from foreign threats.

While Utah lost some assets through BRAC, state and local boosters saved Hill

THE WEST, WHERE half of the nation’s 20 nuclear weapons facilities are located, hasn’t always been so welcoming to that distinction. In the early 1980s, a coalition of religious leaders, peace advocates and ranchers halted the MX missile program, which would have based 550 nuclear missiles in the Great Basin straddling Utah and Nevada. Public opposition to the idea of putting a bullseye on western Utah in a nuclear conflict grew loud, and the death knell for MX sounded when The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints issued a press release on May 5, 1981, from its Salt Lake City headquarters, directly opposing nuclear war and the environmental damage that construction of the missile system would cause to the area and its people.

“Our fathers came to the western area to establish a base from which to carry the gospel of peace to the people of the earth,” the statement from the church’s governing First Presidency concluded. “It is ironic, and a denial of the very essence of that gospel, that in this same general area there should be constructed a mammoth

MARCH 2024 27

weapons system potentially capable of destroying much of civilization.”

Five months later, the Reagan administration scrapped the MX Missile program completely, realizing that without backing from the church’s leadership, gaining public support for the missile basing system would be unattainable, writes former West Point historian and retired Lt. Col. Sherman L. Fleek in the book “The Mormon Military Experience.”

Fittingly, the MX rejection coincided with mounting concern and evidence of adverse health effects from radioactive fallout through the government’s nuclear weapons testing in southern Nevada during the 1950s. Residents had been proud to play a part in staying a step ahead of the Soviets in a global arms race. And there were huge economic benefits to hundreds of thousands of people coming to Las Vegas, where they would live while working at the test site 65 miles to the north. “There was a tradition of people in the West embracing and benefiting greatly from huge federal projects,” says Andy Kirk, a University of Nevada at Las Vegas history professor. “This was just another huge federal project that was going to bring jobs and money.”

Kirk, a principal investigator for the Nevada Test Site Oral History Project, explains that pride and excitement turned to worry in the late 1950s and early 1960s, as those living downwind of the testing in areas of Nevada, Arizona and Utah, along with uranium miners digging up the radioactive uranium for the bombs, reported unusually high rates of illness and death suffered by people and livestock. By the late 1970s, victims mobilized to bring their case to Congress and the courts.

“We liked to play under the trees and shake this (radioactive) fallout onto our heads and our bodies, thinking that we were playing in the snow. Then I would go home and eat,” Gloria Gregerson shared at a southern Utah town meeting convened by Utah Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch in 1979. As a teen, Gregerson developed ovarian, stomach and skin cancer, as well

as leukemia. When she died in 1983 at age 42, she was among 1,100 plaintiffs who had sued the government for negligence in not disclosing the risks of the radioactive fallout from the testing.

The downwinders eventually lost their case against the government, as did a group of sheep ranchers, who blamed nuclear testing for the death and deformities of livestock in southern Utah. But Congress couldn’t ignore the press coverage of the trials, congressional hearings and government reports like “The Forgotten Guinea Pigs,” backing up allegations that the officials had misled residents. Elected leaders responded with the 1990 Radiation Exposure Compensation Act to compensate those harmed.

“I UNDERSTAND GOVERNMENT IS BIG INDUSTRY IN NEW MEXICO. BUT WE END UP BEING HOSTAGE TO THESE BIG MILITARY CONTRACTORS.”

Thirty-four years later, victims are still relying on the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, which has doled out $2.6 billion in reparations to downwinders to date. For Cordova and those within the consortium, it’s a touchstone of hope that expansion for reparations is possible. In December, Congress finally voted on a defense spending bill that included the fate of RECA. But Cordova’s 20-year pursuit was dashed. Republican House leaders demanded the program’s expansion be eliminated in order to pass the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act. Instead of the consortium winning payments up to $100,000 and health care coverage for victims, it came away with nothing.

Press releases coming from New Mexico’s congressional delegation were a mix of disappointment for their state’s downwinders

not qualifying for RECA payments and pride for the billions allocated that will fund military installations and private contractors to generate an estimated $14 billion in economic activity in the state — an apt parallel to the generations-long dilemma of what the real cost-benefit ratio of the military’s presence in the West is. New Mexico Congresswoman Teresa Leger Fernandez, a Democrat, decried GOP House leadership’s decision to drop the compensation expansion as “morally bankrupt.” She then explained her own vote: “I supported the final version of the bipartisan bill in spite of this disgraceful omission because it secures investments in our national defense and service members — including those serving throughout New Mexico.”

Cordova doesn’t fault the state’s congressional leaders for supporting the defense package, despite it leaving the downwinders empty-handed. She understands how important the military-industrial complex is to the state’s economy. As the owner of a roofing company, she has refused to do business with local military bases or government contractors since 2005. It’s cost her. But she doesn’t expect others who support her cause to make the same sacrifice. “We have found other places to invest, but for many, many people their only option for making a living is to work for the government. I understand government is big industry in New Mexico,” Cordova acknowledges. “But we end up being hostage to these big military contractors.” It’s difficult to see how much money is being pumped into and out of the economy to maintain a military-industrial complex, without any of that money coming back to keep the land and people who make it all possible healthy. Cordova continues to work with Congress to extend the expiration date of the compensation program. She hopes that one day there will be an understanding, from the top down, that investing in the defense industry and appropriations to clean up and correct the problems that spending can create are not mutually exclusive. “We’ve got to get people to understand that these are closely linked.”

28 DESERET MAGAZINE THE WEST

THE LAST WAR REPORTER

WE USED TO TRUST

REPORTERS IN THE FIELD.

WHAT HAPPENED?

BY JANE FERGUSON

“

Don’t call yourself a war reporter.”

In a crisp blue suit and enormous corner office, an executive at a news network I once worked for scolded me as he leaned back in his chair and explained: The term doesn’t really exist as a job title. “It’s foreign correspondent.”

It was 2012 and I had just returned from an assignment in Syria as revolution tumbled into all-out war. I was still teetering back into office life after being smuggled into a rebel-held area of Syria, alone, where I filmed and documented the Bashar al-Assad regime’s crackdown on his people. It had been only 48 hours since I trudged across the border to Lebanon on foot, evading armed men to escape in the middle of the night, certain I was about to be shot in the back. Now I was facing a man in a suit. This was something of a debrief with management.

He was technically correct about what I called myself. Referring to oneself as a war reporter was not really the done thing. It was something looked upon as cringy, self-aggrandizing and only articulated by the naïve: those of us still filled with romantic notions of Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway holed up together in a battered

hotel in 1930s Madrid covering the Spanish Civil War.

In that office, still in my 20s, I sat in quiet acquiescence. “Foreign correspondent” is the umbrella term for anyone reporting overseas from the publication or outlet’s home country. The reason the term “war correspondent” is unsatisfactory to many as a “beat” is that it is never an initial posting. Reporters are sent to dicey regions to cover whatever may happen.

IF YOU HAVE AN AX TO GRIND YOU MAY AS WELL BE A PARTY TO THE CONFLICT. WE ALL HAVE OUR BIASES, BUT WE TRY TO LEAVE THEM AT HOME.

“I was a foreign correspondent usually responsible for covering a region, who had to cover conflicts,” says Princeton journalism professor and former Washington Post correspondent and editor Keith Richburg, who spent decades reporting from places like Somalia, Liberia and Afghanistan. If

uprisings, revolutions, riots and skirmishes slide into all-out war, those who stick around and function well find themselves called upon by editors the next time a story arises that needs the strange skills of working well amid chaos and danger. We become known in newsrooms and organizations as the person or people who can cover war.

Journalists have been running through besieged streets and peering out of foxholes for well over 150 years. Each time, their work has been “unprecedented.” Each war is different and the coverage of it new, as both the nature of conflict and funds of the media have evolved over the years. No such evolution, however, has been as rapid and transformative as in the last few years. Technology, access and cultural shifts all have changed the very nature of what a war reporter is. And, what it is not.

Vladimir Putin’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine brought war reporting back into the spotlight after years of international coverage languishing behind American politics and the Covid-19 pandemic. I had never known so many Americans to be

30 DESERET MAGAZINE LETTERS FROM THE FIELD

MARCH 2024 31 PHOTOS PROVIDED BY

JANE FERGUSON

THE AUTHOR IN ADEN, SOUTH YEMEN, IN APRIL 2021.

THE FOG OF WAR HAS BECOME MORE OF A HURRICANE OF MISINFORMATION.

gripped by overseas news, watching each night as they did in the first months of the war in Ukraine. That coverage was suddenly shattered by the war in Gaza, which has since thrust war reporting to center stage in a way not seen since the post-9/11 invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq.

Yet, as the country watches and reads more on war in real time than it has in decades, the profession has changed dramatically, in some ways excelling, and, in others, struggling to survive at all. “The foreign correspondent is increasingly no longer foreign,” says Richburg. “They are a local.”

WHEN THE OCTOBER 7th terrorist attacks happened and subsequent war broke out in Gaza, I was on the leafy campus of Princeton University. Teaching a class on war reporting, I had selected the greats of reporting’s past — from Orwell, Hemingway and Gellhorn in 1930s Spain to Edward R. Murrow in London’s blitz, Marguerite Higgins in Korea and Sydney Schanberg’s “Killing Fields” in Cambodia up to most recent reporting in the post-9/11 wars. I had for weeks been Zooming in class with field reporters in places like Ukraine. Suddenly, videos and images poured out of Israel and Gaza, much of it not from professional journalists in the early days. Never before has the replacement of foreign correspondents by local reporters been more stark … and more necessary.

Students came to class having read the news, but also having seen unsourced videos that had gone viral on Twitter and Instagram, asking if these were real. “Did you see this video?” had replaced, “Did you see that report?” My lectures on sourcing, narrative arc, access and humanity, finding great characters, and how to do strong interviews, seemed at once hopelessly archaic and quaint, and also all the more urgent.

As journalists attempted to keep up with the onslaught of social media commentary and content, mistakes were abundant, from CNN’s on-air claim of confirmation that babies had been beheaded, followed by a retraction, to The New York Times running with

later debunked reports that an Israeli strike had killed hundreds at al-Ahli hospital.

The fog of war had become more of a hurricane of misinformation. It became hard to avoid questions from students on how additive the foreign correspondent is. “That old model of sending out someone from the head office and they would send dispatches back is dying,” Richburg says. “Why would we need it when there are so many Palestinians who can do it?”

Palestinian journalists have done all the reporting from Gaza as foreign reporters are shut out and banned from entering the Gaza Strip. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, over 70 Palestinian journalists have been killed by Israeli fire in the first few months of the war alone. Many have lost family members, been displaced many times, and are working and living amid a massive humanitarian crisis. As local journalists film the war and its impact, the foreign correspondent — who in the past would work alongside them, acting as the face of much of the TV reporting — has in part fallen away, relegated to the other side of the perimeter fence, adding to the growing conversation about our relevance and role in modern war coverage.

Over the years, reporters from Afghanistan, Syria and beyond have grown in numbers and skills, as have indigenous news outlets, but issues of objectivity only increase when those on the ground from specific conflict areas, often activists rather than traditional journalists, are those doing on-the-ground reporting. “Journalism is a trade, it’s a series of things you learn how to do by doing them,” says Paul Wood, a former senior correspondent at the BBC. “But above all, it’s the objectivism. If you have an ax to grind you may as well be a party to the conflict. We all have our biases, but we try to leave them at home. You still have a moral compass, rape is rape and murder is murder. But you cannot take one side.”

The skills Wood refers to involve storytelling that can captivate readers and viewers back home. To build a narrative arc around characters and events that fairly

32 DESERET MAGAZINE LETTERS FROM THE FIELD

encapsulate what’s at the heart of a conflict often takes many years of experience, and building such narratives in a way that doesn’t take a moral stance is a skill best honed from years of reporting from a variety of conflicts. To have covered not just one war, but numerous wars, is the greatest training to understand the gray areas and complexities lost in biased reporting. It’s also about a sense of objectivity. Traditional, more old-fashioned foreign correspondents approached stories not to change events but to help the reader or viewer better understand what was happening.

In modern-day journalism, activism and opinion has seeped deeper into the words and stories told. Both foreign correspondents and locals are increasingly leaning into identities and personal politics. The old argument that foreign correspondents, as professionals without skin in the game, would be more objective, was always only a half-truth, argues Richburg.

“That was always a conceit — that the guy sent out from headquarters was always going to be more subjective,” he says. “We already bring our own share of biases that we don’t like to acknowledge.” Both the growth in local journalism and the current cultural squeamishness at Western, often white, reporters flying to war zones has drawn

criticism of the traditional image of the war correspondent. Given that many countries experiencing conflict do indeed have journalists there, vocal criticism of “parachute journalism” has grown in recent years. Yet, the ranks of the war reporter among American outlets are increasingly diverse, and many fly in from their homes located in the region. Reporters who have familial ties to the region can bring with them language skills and a cultural understanding that helps them gain better access, as well as add a nuanced humanity to their work. After showing my students the breathless live news reporting of the “shock and awe” bombardment of Baghdad in March 2003, and embedded reporting of journalists with the U.S. Army as it invaded Iraq, they read Anthony Shadid’s remarkable reports from inside the homes of Iraqis. The two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning Lebanese American correspondent reported with unmatched tenderness and detail on the experiences and evolving opinions of Iraqis from all over the country. His warm personality, fluent Arabic and Islamic affairs expertise helped him gain people’s trust and spend time inside their communities.

Living in the region is important. When foreign correspondents have moved to Beirut or Cairo, Sanaa or Damascus, or

elsewhere in other regions of the world, they are forced to spend huge amounts of time within communities, many times learning the language. Their interactions are not limited to academics, politicians and military commanders. Quaint as it sounds, daily interactions with service workers, neighbors, local officials and business owners shape understanding of the variety of complex perspectives on the ground. It’s also a literal reminder that life exists — and society functions — beyond the confines of war. Those of us living in the field used to joke about how journalists flying in from Western countries would interview their taxi driver from the airport. If you pay attention, you might notice a lot of cabbies quoted in Western newspaper reports.

I LIVED IN the Middle East for 14 years as a war reporter — my parachute was usually a very short Middle East Airlines flight followed by a bumpy drive. If there is a case to be made for the traditional war reporter, it’s cultural, or rather an ability to humanize stories in a universal way that connects back home. When I reported on the Taliban’s crackdown on Afghan women’s rights for “PBS NewsHour,” I wanted my audience to connect with and understand what the

THE AUTHOR TALKING TO YEMENI CHILDREN IN A CAMP JUST OUTSIDE MARIB, YEMEN, IN MARCH 2021, AFTER THEIR DISPLACEMENT. ACCORDING TO HER REPORTING, MOST SHE SPOKE WITH DIDN'T REMEMBER A TIME BEFORE WAR.

MARCH 2024 33

loss of their rights meant to women as individuals. I profiled a female gynecologist who worked her entire life to build a practice, rising to become one of the nation’s leading doctors. With the Taliban now in charge, she was faced with having to leave the country — and with it her right to practice medicine and her daughters’ access to education. She told her story with intensity and emotional honesty when I sat to interview her. This piece was not simply about the denial of women’s and girls’ rights, but the sacrifices mothers make for their children — something I knew many in the Western audience would relate to. Knowing the readership can be just as important as knowing the cultures from which you are reporting; a hard-won lesson learned by many foreign correspondents.

But those are the rules of news specials and features. When it comes to breaking news, it’s simply not possible or necessary for foreign correspondents to be on the spot when news happens. Today almost the entire world is carrying a camera in their

pocket. With social media, anyone is capable of sending information out like a news agency. The result? Reporting is technically open to anyone in the right place at the right time, and not limited to those working for news outlets. When Beirut was devastated by a massive explosion at the city’s port in August 2020, I had by pure luck just moved to New York City a few weeks before. As I unpacked boxes in my new apartment, I began seeing images and videos of the destruction of my former home. It took over an hour of scrolling through raw images on Twitter for news reports to even begin to clarify what had happened. It was a vivid example, and in this case a personal one, of the new norm of content appearing before verified news.

Beirut’s port explosion was an example of how powerful this ability to be connected to people in real time is. The world can be aware almost instantly of what is happening, which has proved to be a vital lifeline for those living under insufferable repression from regimes that effectively ban both international and domestic reporters.

In Myanmar following the military coup of 2021, the crackdown on pro-democracy activists was swift, brutal and conducted in the shadows. Fighting between ethnic armed groups and the junta has displaced over 2 million, according to the United Nations. Whatever trickle of images and information making it out is coming from local “citizen journalists.” This phenomenon began in earnest a decade before.

THE SYRIAN CIVIL War changed war reporting. It was a war where the rebels, hopelessly outgunned, welcomed and helped journalists visit the areas they held. Reporters like Paul Wood and myself were whisked from Beirut’s bustling streets and smuggled across the border to Lebanon to show the extent of the Bashar al-Assad regime’s crackdown on protests and the growing armed uprising. It was incredibly dangerous work, as exemplified in the killing of American journalist Marie Colvin on Feb. 22, 2012, but provided extraordinary access.

34 DESERET MAGAZINE

LETTERS FROM THE FIELD

THE AUTHOR MEETS WITH A MILITIA OF ANTI-TALIBAN FIGHTERS IN THE PANJSHIR REGION OF AFGHANISTAN IN 2021.

BLOCKING JOURNALISTS FROM WAR ZONES, DENYING VISAS AND DISCOURAGING THE VERY PRESENCE OF JOURNALISTS BY KILLING THEM USED TO BE SOMETHING MORE AKIN TO DICTATORSHIPS. IT HAS BECOME MUCH MORE COMMON THESE DAYS.

Driving through the night from Beirut to avoid detection from Hezbollah-allied soldiers, I was ferried through the backroads of Lebanon and foggy fields to the border. For several days I was passed from one safe house to another, hosted by a network of sympathetic civilians, until I was in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Homs city, the origin of the uprising. The activists, young men who had been involved in opposition protests for months, took massive risks to get me and my colleagues into Syria because they wanted the rest of the world to know what was happening. Over the noise of tank shells and the crack of sniper rounds, one of them laughed, “Welcome to Syria!” I shuddered.

In the control center of their rebellion, they sat around on the floor, frantically smoking, uploading videos and content they had shot to YouTube and Facebook. While the trickle of journalists making it into Baba Amr could only bring out a certain amount of footage and reporting, the activists took the lead in filling in the blanks. They were doing the job of news organizations for themselves, and many American and European outlets aired their footage from field hospitals and basements filled with sheltering civilians.

This footage was vital to helping the world understand what was happening after Bashar al-Assad claimed he was killing “terrorists.” But the footage was more activism than reporting, in large part because it was done with an outcome in mind. These young men wanted the West’s help. They had seen what intervention in Libya just months before had done to cripple the Qaddafi regime, and hoped for similar aid.

Sitting on the floor of the apartment they had based themselves in, they smoked and watched TV coverage of the emergency U.N. Security Council meetings, their laptops open, waiting for footage to upload slowly on a weak internet connection. “Do you think Obama will do a No Fly Zone?” one of them asked me. Most of the young men in that room would later disappear into Syria’s jails or battlegrounds and never be seen again.

Their work gave the world access to a war that a dictatorship did not wish to be seen. It also highlighted the limitations of such reporting. At times, the activists, both untrained in professional reporting and motivated by their desire to overthrow the Syrian government, partly staged scenes in some of their videos. At one point, they were caught setting fire to tires to provide a cloud of smoke behind them while addressing the camera.

Gaza is now the clearest example of a people filming their war for themselves and sending it out for the world to see. Technological advances, coupled with social media accounts, are providing an enormous platform for growing citizen journalism, as well as activism, as access has become one of the greatest challenges to the traditional war reporter. Blocking journalists from war zones, denying visas, preventing any embeds with militaries and discouraging the very presence of journalists by killing them used to be something more akin to dictatorships. It has become much more common these days, losing its taboo among democratic states. As the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan dragged into its final years, military commanders took advantage of the

growing apathy in the U.S. toward the war to effectively ban reporters.

If journalists aren’t able to gain access and report in conflict zones, we have no opportunity to utilize the strengths of foreign correspondence. Instead, our information will be limited, coming only from local activists and reporters. The more restrictions that are in place for those trying to bring information home, the more the fog of war will continue to crystallize into an impenetrable wall.

In 2019, after recording an interview with a senior Afghan defense official, I took the opportunity as we sipped tea to press him for access to Afghan troops on the battlefield. Afghan government soldiers and police were being killed in record numbers and I knew the Kabul government wanted the U.S. to acknowledge the sacrifices being made. I explained that commanders were denying our requests. “We would love to do embeds with American reporters,” said the official, before pausing and lowering his voice. “But we cannot.”

“The Americans have told you not to?” I asked.

“Yes, they have been very clear — no journalists,” he said, looking down at his hands.

Two years later, I and foreign correspondents from some of the biggest American media outlets all signed a letter of petition to the Pentagon, urging more transparency and access to the war in Afghanistan. There was no response. By the end of the war, the running joke was that it was easier to access embeds with the Taliban than it was with U.S. or Afghan government troops. It was — I spent more time with Taliban units than any other.

MARCH 2024 35

TO T HE S HIP

THE JOURNEY TO ALASKA’S MOST REMOTE BASKETBALL REUNION

By KADE KRICHKO // Photography by ALANA PATERSON

By KADE KRICHKO // Photography by ALANA PATERSON

IT’S A CLEAR NIGHT

for a sail — a rarity for the Alaskan winter — as the ferry cleaves its way between inky mountain silhouettes. Samara Kasayulie-Kookesh sits silently in a white pool chair, braiding her sister Cheyenne’s black hair. Her fingers move deftly despite the cold; she’s accustomed to the frigid darkness. This is a journey she’s been making since before she could walk.

Ferries like this one, the MV LeConte, connect Southeast Alaska’s stretch of remote islands — home to the Tlingit and Haida — to jobs, groceries and conveniences taken for granted on the mainland. But tonight, the ferry is headed to Juneau for something special, for a tradition over a half-century in the making. Tonight, this boat is carrying Samara and her sister to a basketball tournament.

Tipping off shortly after the end of World War II, the Lions Club Gold Medal Basketball Tournament is one of the longest-running amateur sports tournaments in the country. Every March for over 75 years, thousands of Southeast Alaskans pack the gym at Juneau-Douglas High School for a week of games spread across four divisions. It’s a rowdy celebration of sport and culture, bringing together a geographically splintered community for annual bragging rights. While most of the country has its

eyes on the NCAA’s March Madness farther south, for a primarily Indigenous community isolated for most of the year, the Gold Medal has become a rallying point much bigger than the game itself.