NOW IN

Descent is a student-run arts magazine at USC. We produce a semesterly online magazine featuring works by APIDA creators at USC. Our mission is to elevate and amplify APIDA voices by nurturing a space where they can showcase the their artwork, stories and other creations.

Editors-in-Chief

Emily Ching

Mendy Kong

Art Director, Photographer

Marissa Ding Writing Editor

Emily Chen

Staff Writing Directors

Z Luo Echo Tang PR Director Kyle Ching

Internal Outreach Director, Staff Writer

Sreenidhi Boopathi

External Outreach Directors

Pia Pelaez Susan Tang

Visual Designers

Jasmine Kwok Raina Paeper Audrey Ma Devon Lee Isabelle Lim Alyssa Ng Staff Writers

Ally Guo Megan Dang Tamanna Sood x Paul Liu

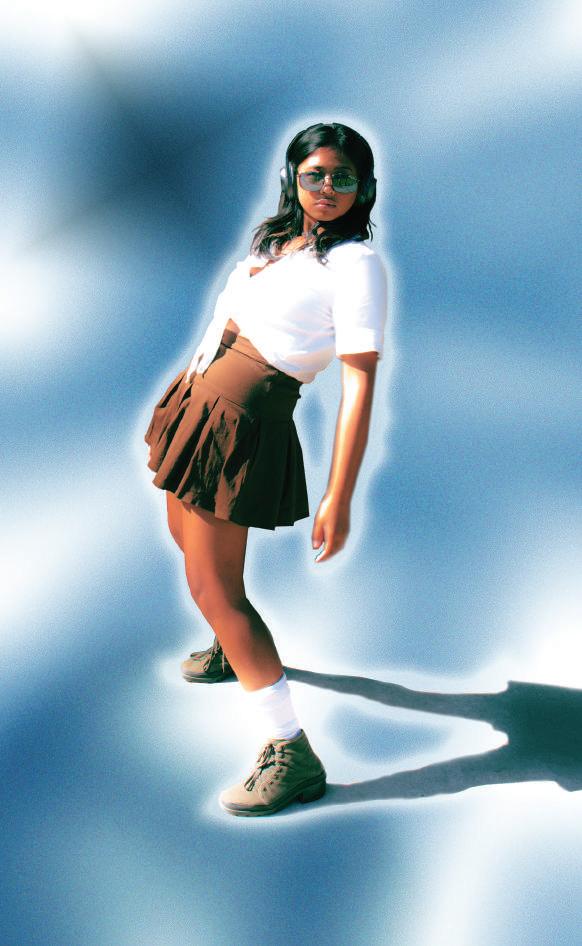

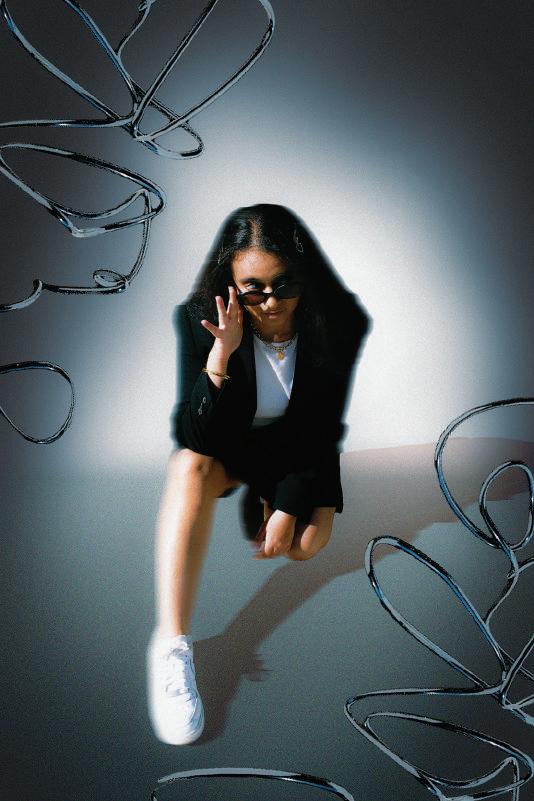

Photographer: Marissa Ding Model: Makayla Oas

Letter from the Editors 3

Call From Home Megan Dang 45

Photos by Trenyce Tong 49

Alisa Leyao Wu

Here’s You Biking Celine Wu 23

Crickets, Pistachios, and Other Sources of Protein

yestermorrow Sreenidhi Boopathi 27 Vignettes from Home Tamanna Sood 28 sweet and sour 19

Z Luo

Photos by Trenyce Tong 41 Elegy to a Beach in Half Moon Bay, Elegy to my mother’s hands

43

33 homeleaving 52 Srija Ponna The Seamstress 55 Yusuf Rahman Love is sometimes teeth 59 Fear the World in a Ladybug 65 Rui Zhang Ally Guo Paul Liu

things left behind

Small change sandwiched between the couch cushions. A ticket stub flitting towards the pavement. A relationship that no longer serves you. Former ide ologies that you’ve shed, the chrysalis of a past self. The theme of our forthcoming issue, things left behind, is at once ephemeral and intangible, reve latory and mournful. We encourage you to write and create your way back to them, and to ask: in what ways do the things we leave behind stick with us?

Hello,

Thanks for reading the fourth issue of Descent! The theme for this issue was “things left behind,” and we are so excited to bring you stories and art that capture so perfectly what we feel as we grow up and inevitably leave things behind.

This semester, we were so proud and lucky to have grown our team to have more writers and designers to support our mis sion, and we hope that shows in this edition–especially as our first print issue. None of this would’ve been possible without our amazing team, and everyone who participated in any part of the process.

We hope that Descent can continue to be a space for Asian creatives, and that this edition inspires you to create and share your work whenever and wherever.

Please enjoy our first print issue of Descent!!

Thank you, Emi Ching and Mendy Kong

THINGS LEFT BEHIND

Katelyn Do

Nikia Fenix

Darcy Hatcher

Harshini Karthikeyan

Isabelle Lim Elizabeth Nguyen

Sadi Noor

Mehima Pruthi Hera Song

Zakariya Syed

Ka Yan Tam

Feben Worku Leslie Zhang

Marissa Ding Mendy Kong

STYLISTS

Mendy Kong Marissa Ding

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Mendy Kong

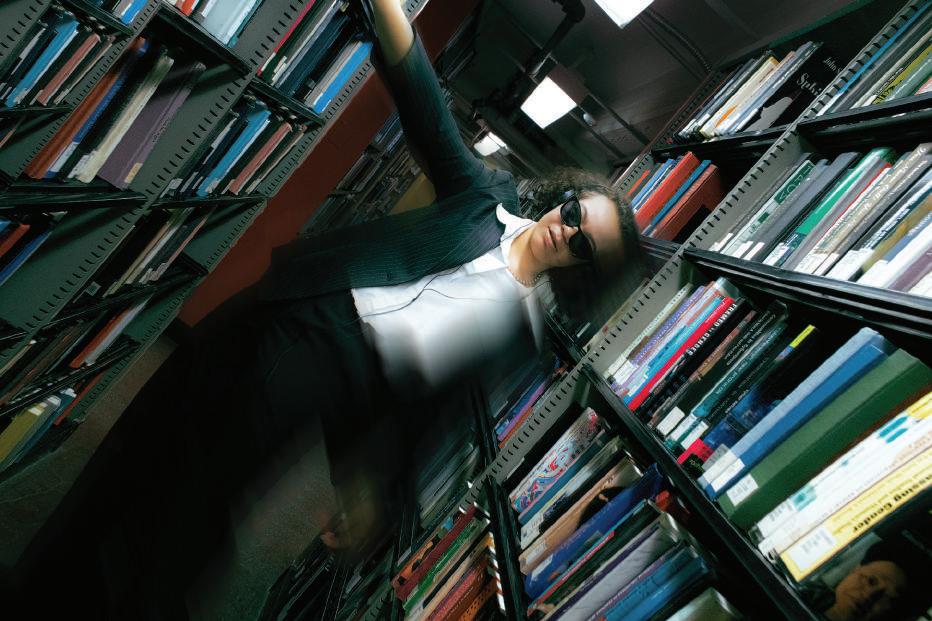

PHOTOS BY MARISSA on p. 6-8,15-18, 21-22, 25-26, 31-32

PHOTOS BY MENDY on p. 53-54, 57-58, 61-64, 75-78, 81

Her usual spot is at our dining room table. In the months transitioning from summer to the fall, when the days reach long into the evening, that room is always washed with a dreamy yellow sunlight, so bright and so warm that it captures you in a wide-eyed daze. The old oak floorboards feel balmy on my feet. Outside, pine trees wave; my grandmother stands and watches them through white wooden shutters, hands clasped behind her back.

Her coloring books conceal the tops of the dining room table and kitchen table. Some are in neat stacks, others splayed open, works in progress bookmarked for later. Here and there are tiny black fish, brown birds, and green flowers, all intricately detailed, colored with a careful, even hand.

My grandmother lives in Korea and only comes to America for big events. Births, deaths, weddings, graduations, anniversaries. Whenever my grandmother comes to visit us, we help her improve her health. We help her to exercise frequently and eat healthy food to lower her high blood pressure. We massage her sore knees and back. We take her on vacations. Learning about the mental health benefits, my mother had bought coloring books during one of my grandmother’s visits.

My grandmother took it on, integrating it into all of our routines. In the mornings, she used to prepare fruit in front of me, as I sat at the kitchen table, dressed in my school uniform. I would sharpen her colored pencils, dull from the previous day, and make sure that she had enough of each color. In those moments, it always seemed that we didn’t really look at each other; rather, we watched each other. I, watching her hands, deftly cutting apples, peeling oranges, washing grapes and berries. She, watching my own hands, carving those pencils into sharpened points. And then, I’d leave for the day, my mother’s hand pushing down the back of my head, folding my body into a farewell bow. When I would come back, approximately eight hours later, I’d find a new page of her coloring book completed, filled with bright colors. Her pencils would be blunt, but carefully stored in the box.

Because of my mother’s stories, I feel that I know both everything and nothing about my grandmother. She seemed to be more symbol and story than flesh and blood. Lying on top of her bed, me on one side and my sister on the other, my mother told us about our family thousands of miles away. In my mother’s stories, although we used the proper titles for some, our family members were given new names.

My older aunt:

Proper title: Kun-e-mo (older aunt)

Our name: Il-bon-e-mo (Japanese aunt)

You can never mess with Il-bon-emo, my mother says. No one can. Il-bone-mo is a strong, gentle, and patient giant who, according to family lore, almost

crushed her baby sister underneath her legendary thighs while she was sleeping. Her body, at 5 feet 7 inches, ripples with an aura of power. After a lifetime of playing professional golf in Japan, she is the wealthiest in our family, although she never shows it.

Il-bon-e-mo, who barely had a father, is sorry that she was given the unfortunate honor of being the first born out of five. Il-bon-e-mo, who never got to play, used her pencils to nubs while packing new ones into her younger siblings’ bags. She woke early with her mother, carried all four of her siblings to school, and came straight to the family store after classes ended. Dressed in a kimono for her wedding to a Japanese bodybuilder who cried and cried for months after their miniature Schnauzer died.

Once, sitting in the passenger seat of her enormous minivan packed with golfing equipment, I asked her if she always wanted to be a golfer. She stared ahead at the windshield wipers rapidly swishing away the monsoon rains and the blurry streets of Tokyo. No, she sighed. I once wanted to become a school teacher.

Younger aunt: Proper title: Ja-geun-e-mo (younger aunt)

Our name: E-ppeun-e-mo (pretty aunt)

There is a reason for E-ppeune-mo’s name. She is the quintessential wealthy Korean woman. Her speech is dabbled with cosmopolitan English vo cabulary (“Oh my god!” “Of course!”), and her spacious Gangnam apartment is

filled with the newest talking gadgets and appliances.

E-ppeun-e-mo spends most of her day in her apartment with her white Pomer anian named Echo. “E-cho-yaaaa~~~” she stretches out his name as she poured out his food for him. She wakes up late, hours after her husband, who works in finance, would have left for work.

When I came to visit her, I found her kitchen stocked with “American” foods that she had bought for me: soft cheeses, sweet breads, cartons of milk, yogurt, fruit jams, and so on.

She loves talking, maybe too much. She looks around herself and talks out loud as she moves, causing the passerby to wonder if she was talking to them and whether they should answer her or not. She gasps, “O-mo!” and widens her eyes at little things. The price of watermelons. A strang er’s jacket. She asks questions without waiting for answers.

Around her apartment are old things that aren’t used anymore. Baking equip ment and books. She had wanted to open her own bakery. Photography equipment. She had wanted to become a photographer. Clothing, tags still on. A collection of books, not read.

She drives a German car, a collec tion of bracelets jingling on her wrists as she turns the wheel.

When I visit her, I sleep in a small room adjacent to the kitchen. Once, when I woke up, I stayed in bed. I listened to my auntie’s slippers sliding around the kitchen floor, and I could see her clearly in my mind. Her, dressed in an expensive silk robe. Grinding her import ed coffee, tapping the grounds into her glass pour-over dripper. Dark black liquid dropping into her gilded china tea cup. A teaspoon of sugar – not too much – and a drop of cream. Her, drinking her coffee alone in her shadowy kitchen, surrounded by her white Pomeranian named Echo and her talking kitchen appliances, chirp ing and twittering.

Grandmother: Proper title: We-halmoni (maternal grandmother)

Our name: Dong-gul Dong-gul Halmoni (round grandmother)

Straight from SFO airport, halmoni sits on the living room floor as we gather around her. My mother massages her legs. “Look at how short your halmo ni’s legs are! Can you believe she went through all her life with these short legs?”

My mother’s stories of 1980’s Seoul are filled with construction dust and teargas. Halmoni has always been dong-gul dong-gul, even when she was younger. Her store was located by the industrial section of the city, surrounded by factories. She served mostly factory workers, who were just as tired as her, cheap meals that they would eat on the wobbly little tables until it was time to go back to work.

She mothered deep into the night. Under the stars, she stomped her bare feet into a water-filled basin containing

the laundry of seven people. In the blue moonlight, she bent over a basket of dried anchovies, gutting them by hand, one by one. Shadow-faced, she checked on each of her sleeping babies lying in a row on the heated floor of their oneroomed home. In a dim corner, she drew her knees up to her chest and cried silently into her hands for her own moth er. She dreams of the cold waters of the stream next to her childhood home, long gone.

My grandmother forgot her own name during the war. She was around my age when she married my grandfa ther, who was a crazy old man. Before that, he was an angry old man. And before then? I have no idea.

Everyone knew he was going to die soon, it was just a matter of when. Alzheimer’s had transformed my grandfa ther, whose hands once slapped his wife and whose feet kicked his children, into a senile, childlike man. He escapes the house and wanders the streets, talking to himself. He once unintentionally stole a watermelon from a market because he remembered that it was my mother’s favorite food, despite not remembering who she was and what her name was. He slipped the hair dryer between the sheets of my grandmother’s bed to “warm it up.” My grandmother just sighed and led him back to his chair in the main room. Eat your grapes.

My grandfather, who used to call my mother “E-ppeuni” (pretty one) and sneak her candy from his coat pockets. Who resorted to verbally abusing his teenage children when he was no longer able to physically beat them. Preferred extra salt in his dishes. Visiting his mounded grave on a wild hillside, my mother poured a drink into the earth and

stood cursing him, her college diploma –which, since she was a woman, he had so vehemently opposed for all his life – clutched in her hands. Look at what I have done. Despite everything you have done to me.

My grandmother’s voice comes from deep inside her chest, a steady, rumbling litany of. There is a rhythm to it; it moves slowly, like a mantra or prayer. The intonation flows up and down like swelling waves, with comfortable pauses in between. Her voice, in joy, vibrates and crackles – rich and tonal. In sadness, it reduces itself to a smoldering dirge. Her voice is propelled by other voices, sitting beside her, coaxing, Ahhhh, nae, eung, mmm. When there is no one to listen and hear, her voice becomes quiet. We took a walk in a bamboo forest. It was so dense that the path ahead faded into dark. We reached a small house built in the traditional Korean style, a rest stop for hikers. We kicked off our shoes, and I, unaccustomed to the summer humidity and drenched with sweat, sprawled across the soft wooden floor. My grandmother sat by the edge of the main area, leaning against one of the wooden columns and her feet dangling off the side of the house. She spoke: “This looks like the house I used to live in as a child.”

The cicadas screamed into our ears. I am at a loss for words, I am overwhelmed by it. I possess a morbid

curiosity. I want to ask questions that should not be asked, to imagine what is at best should be unimaginable. From my family’s clues and my personal ob servations sprouted wild speculations and hypotheticals about my grandmother – inserting impossibly detailed sights, sounds, and smells.

An enormous mandala, maybe two feet wide. There were dozens of lay ers, like an onion, each building onto the other, just a little different from the one before, radiating out from the originating core. The colors brought out each layer so dazzlingly, so brilliantly, that I took out my camera and took a picture.

Every time I saw that the pencils were blunt, I felt relief in sharpening them for her. Every time I saw that she had finished a book, I bought another with relish. When I was away from home, I allowed myself to imagine her in her spot in the dining room, chugging away at the books, coloring in satisfying rainbows.

I imagine my grandmother sitting in the clinic, E-ppeun-e-mo at her side cradling her elbow, the young psychiatrist in the white coat attempting to sort her past with terms she does not understand. I want to believe that there are these clues left by my family – breadcrumbs lined up for me to find and follow back home. I want to believe that my family’s story is more than history books. I want to believe that this is more than just an old tragedy or a pity-story rushed through by an impatient family member, or the whispered laments I overhear, or the ghostly, unexplained references older family members make, left with the ends still frayed. And most of all, I want to be lieve that things will get better.

Because anonymity begins with black fog and something behind you. Orpheus is all tenderness and soft things and he craves the taste of matrimony because it holds him together, his body stable. Otherwise, he falls apart like a wedding cake. Waiting. Because he doubts all he could hear was the sound of the winds, wailing. Perhaps it is the fates singing of the tragedy he inhales, exhales, inhales again. Lachesis weaves a sweater out of his misery. When Orpheus turns, Eurydice falls upon a second death. She walks into the belly of the underworld, her ankle stinging like a bite. Because he realizes that his memory will not leave him, a certainty that something that would never die before him and that to immortalize is to be remembered. When he turns around, watches Eurydice’s body dissolve in death, he knows that he’ll never be alone. What is grief if not the grit of love?

Because he turns for nothing. But you know those poets, those romantics. They’ll think of something. Because as he wades past the stench of death he arrives at the threshold of the mortal realm, and beneath his foot he hears a slight but sickening crunch. Stamped to the bottom of his sole is the torn body of a butterfly, its wings crumpled like a dried leaf against his muddy heel, flaking off like skin. And he realizes that to be beautiful is to be temporary two-fold. Because behind him, the snap of a twig.

visions of home are red leather booths growing up, wrists shaking balancing heaping plates of food slightly warped menus ghosts of diners fingertips still linger two thousand miles away now dreams of afternoons spent watching grandpa stir glossy red batches of sweet and sour sauce the creation of ingredients he keeps tight lipped was faded orange last time i really looked at it they stopped selling the old food dye, he said

it doesn't look right to me anymore too diluted, childhood dulled twenty now, watching my siblings shoot up to match me in height a newfound resemblance in how our eyeliner is alike

mother and father tell me not to worry too much “nothing’s changed at all with us” but their exhaustion is exponential when they pick me up from john glenn international we drive past my old stomping grounds en route to the house

even suburbia, in its sleepiness, shifts the demolition of lincoln elementary, “free bricks” kindergarten field trip to a library now gone hundred year old high school barely clinging on rose-tinted glasses hide bruised reminders that home’s like a water-stained photo unknowing of its own edges bleeding

once so happy to leave, “see the world” my eyes stay shut most days now vibrant saturation, the memories twirl gently reminding me how my world exists in plastic containers red and glistening, my family’s labor

our ordinary existence extended family dinners on sundays facetiming to say hi, it’s not the same dad rebuilt the shelf to house the new TV it’s enormous, as tall as my baby brother guess he’s not a baby anymore things change too fast

melancholy, my nostalgia clings to me, tart and sticky, I feel so sweet and sour.

After Monica Sok

Here’s where you first completed a 360-degree turn in the concrete front yard After your father screwed off the training wheels After witnessing the sky dim and feeling the initial raindrop Here’s your father’s reassuring encouragement Penetrating through your victorious laughs The same deep, confident, echoing voice that softens When he sees you snuggled up in the bunk bed Whispering “good night, bye-bye, have a good dream…” Here’s the second 360 circle you completed The third, the fourth, with increasing velocity Here’s your mom waving from the 6th floor, cheering you on Here’s the fifth turn

When the raindrops pushed your wheel sideways When the angle of your bike was one degree off And you slide and tilt onto the moist concrete Leaving your knees a mixture of disturbed skin, blood, and dust Here’s you holding back tears as your joy still overpowered the burns Here’s your father picking up the bicycle while offering a steady warm hand

Here’s you out-growing the bunk bed Your parents sacrificing for your education

the distance in painful memory like how the sun’s heat warms your back on a wintry day from light years away ultra violet piercing through only for you to keep lying there like a fool loitering in luscious flush misery misery misery misery misery misery misery misery misery breeds company keeps company keeps us company; childhood blanket covering muffled cries, sweaters covering scars, sweat and tears laughs and fears, a rubescent lens and the past The finding-shapes-in-clouds of it all

Perfect proportionate purple pieces. She cuts onions like a machine. The last time I picked up a knife to help her she laughed at my pathetic attempts to mince the onions. She cuts vegetables with the knife facing her. Every swipe through the onion, the knife hits her thumb, digging deeper into the indentation that has been growing for years. She works at the speed of light with the knife cutting at a rhythm. The stench of the onion burns my eyes, but she’s unphased and disinterested. She takes twenty seconds from cutting to check on the three other dishes she has laid on the stove.

I greet her with a hug and kiss on the cheek. The distance between us on most days is 30 miles, yet I feel as though I’ve traversed a nation when I see her. Her hair is grayer than the last time I saw her and her eyes are tired. Yet her hands are as fast as they were when I was a child. Cutting, cooking, and cleaning up as she goes. The system has been the same since I was born.

I’m back home after only a couple weeks, but to the blind eye, the feast being prepared for me would suggest I was returning after a war. Aloo Phaliyan, Kadhi, Pulao, and Chicken Karahi. All my favorites.

“We don’t eat dinner anymore. After you left, this is the first time I’m cooking so much,” Nanima said. “Mumma is going through another phase. She’s intermittent fasting. She does eat from 18 hours. She’s gonna get sick,” she says in an aggravated tone.

These days the house is quiet. She spends silent days on lonely couches waiting for the door to open.

These days she breaks the hush of solitude by watching dramas and making up for the sleep that escapes her during the night. What she doesn’t say through words, my Nanima prefers to say through meals.

“ I missed you. Have you been well? Are you staying strong? You know I’m here for you,” The aroma of each dish whispers to me. “Don’t worry. I’ll eat enough for everyone to day,” I reassure her as I set my plate down. Each bite at home undoes a knot of anxiety and exhaustion. The constant deadlines in my head meltaway as I sit down at a dinner table for the first time in weeks. For days, the only other face I saw while I ate was that of a character in a passive Netflix watch.

“Eat more. This is nothing,” she grunts at me. I try not to see the hypocrisy in this comment and ignore how she mentioned how “healthy” my figure had gotten when I had walked in through the door.

I continue to scarf my meal as she fills me in about the random drama that is occurring in her friend group. I’m always surprised at how much more interesting the lives of her 80 year besties are in comparison to mine.

“You did the right thing. She’s crazy and her son is a creep,” I add oil to the fire. She nods, her eyes bright and excited, and picks up her bedazzled cell phone to show me the “gaudy” outfits her nemesis wore at the last event.

. . .

The doorknob of my house has been broken for three years now. Every so often, the door’s lock jams and doesn’t close properly. My dad figured out that if you take a fork, jam it back into the hole of the lock at the right angle, and wiggle it with enough force, the jammed lock will revert back. For this reason, I generally avoid opening the front door of the house.

Today, like every other day in the San Fernando Valley, it’s dry, hot, and windy. The door keeps slamming open and shut because the jam hasn’t been loosed today. It’s the fourth time I’ve walked back to shut the door. Dad’s not home and no one else, except my brother, seems to know what angle to stick the fork in. The door doesn’t like women I guess.

“It just needs some oil. I need to buy some,” Mumma says again for the umpteenth time in three years as she continues to shuffle through recent Bollywood movies to find something we can watch together.

I’m laying on the new couch she bought after I bought it and I left for college. It’s white. She and nanima spent two weeks sewing covers so they would feel comfort able leisuring on it. I think I’ve found a new favorite place on this couch as I realize it allows the sun to hit my face and warm my cheeks because it doesn’t block the window like the old one. My eyes are closed and I feel the lull of a post feast nap coming upon me. The sweet scent of pine sol, the musk of agarbatti, the aroma of the day’s feast

intermingle and kiss my nose whenever I’m home. They say that each house has a distinct smell that no one in the house can smell. Every time I’ve come back home, I’ve been hit with a whiff of nostalgia. And a reminder of the time spent apart.

My mother swats my arm and forces me to open my eyes. She’s showing me the new table to match the couch.

“Say goodbye to this table,” she says. I wave at it and she laughs. The table was made out of a cheap marble material that seemed to seep into it every spill and memory that occurred on it. I stare at the spills that mark the day I lost my first tooth and the spill of the day I got into my dream school and silently say goodbye.

My favorite chai pot has an orange plastic handle that is supposed to curve at the end, but it’s misshapen and melted from the time I accidentally let her face the flame. The whole house smelled like melted plastic that day and the wrath of my Nanima and mother reigned against me for a week. She’s my favorite pot for multiple reasons. She has a spout that allows even an amateur like me to pour chai without making a mess. She has a pretty voice too. She sings when the water inside her has come to a boil. She’s the most reliable friend to make a per fect chai. No other pot compares.

On average, chai is made three times a day in my house. Five times on the weekends. The pot of chai makes seven cups of chai for four people because my dad and I drink two cups worth every go. Our cupboard is filled with mismatched tea cup sets as everyone in the house has a favorite cup. Most are chipped from the top crying to be thrown out.

My dad’s and my mugs are different. We bought each other our favorite mugs. They are large - almost too big. His mug is a deep blue cauldron with its own spoon that I bought on a trip in Vegas. My favorite is a mug dec orated with the letter T which he bought from Target. Both of the same size, large, and made of porcelain. Sometimes we switch off.

I hand him his mug at his computer desk and drag a chair to sit next to him. He’s scroll ing youtube and watching movie reviews. Movies are our favorite topic of conversation and politics are our least. His headphones are broken from one side and he’s holding the right side of the device to ear to hear the review properly. Most probably this is attribut ed to the fact that he has never spent over 20 dollars on a pair.

He drinks his chai piping hot and in long gulps. As a kid and even now, I wonder about how his mouth didn’t burn when he sipped it.

His thumbs are large and can’t fit properly in any other teacup, but sit comfortably in the handle of his mug.

He’s a quiet person. Soft spoken and generally introverted. In comparison to the tsunami that exists in my mother, my dad is a leisurely tidal wave. Most of the conversations he holds are with himself. It’s a habit of his. I often find him speaking to himself.

“You would like this movie. It’s about folk stories and revolution. Let me look at tickets,” he says as he sees me peeking over his shoulder. I nod and ask him more about the film. My dad and I are alike in multiple ways. We love our chai, our books, and our movies.

His eyes and mine hold the same dark circles too. He’s been working weekends lately. He goes into the office for at least a couple hours everyday. Having his own business blurs the line between home and work for him as all his time is spent dealing with his clients. He dawdles about the house leaving a trail of dirty socks in each room. He’s faced the anger of my mother and I for years about it, but he refuses to change.

Today, he walks barefoot on the cold floor again, quietly mumbling to himself, stomping on the tile all the way to the stove. He opens the cabinet, picks out the orange handled pot, fills it with water, and sets it to boil on the stove. Another cup of chai is to be made and I am to make it..

He returns to the computer. His dirty socks lay hidden underneath the desk beside his overfilled backpack which he drags to work everyday believing that he will be able to peruse every document in it.

He won’t.

“Sometimes, cake is cake. Other times cake is not cake. It is bread.” –A Cake Spirit

“It’s time to leave.”

Startled, you turn, dropping your batter-draped chopsticks and sending lime green batter flying.

I’m baking! Give me a warning, won’t you?

“We have to go. They’re coming.”

But I’m baaaaking! How else will you get your nutrients?

Turning back to your dough, you sigh. What a waste. It’s still salvageable though you might have to reduce the eggs.

“Are you even packed?”

Yeah. My bag’s right there. Pass me the pistachios, will you? This one’s got all your favorites in it.

“Are you listening to me? We have to go. They’ll be here soon.”

Are you listening to me? I’m baking! I can’t go. Whoever they are can wait. Now, do you want lime curd or pandan curd? Oh! We can make egg tarts with the leftovers! Which crust–

“Fine. I warned you.”

That’s all the warning you get before your in gredient-strewn countertop recedes from you. Oh, there’s still some scarlet crusting over from your last foray into raspberry chili bread.

Seriously?

“At least you’re still carrying some dough. I have your bag too. Just bake when we get there.”

But my apricot-lychee buns are still rising in the oven! My buns! Let me down, get my buns! Year 666, Ungodly Era, Season of Winds

The cabinets were the ugliest thing in your new home. And the countertops are all lumpily stained ever-worsening shades of brown and grey. You’re almost certain that it single-handedly kept this place uninhabited by ghosts and other yao.

.

Built into the floor and sprawling across the kitchen, the cabinets were all splashes of white against gold-flecked lopsided rhombi, intersected with what looked like an homage to neon orange half-cooked gruel. You don’t think that even the staunchest fans of abstract art could find something palatable about it.

But, what caught your eyes was the pulls of the messiest cabinet. The cabbage-leaf hinges were unique, certainly, but the handles have been completely scoured of utilitarian ism. Someone had replaced the simple, teakwood knobs and useless cyan tassels with lithe, cavoting creatures, the wood somehow

maintaining the movement of silken sashes and ribbons.

Spindly feathers invite you to touch and, before you know it, you’ve teleported into the cabinet. Messily scrawled characters dance with humanoid carvings. Glimpses of familiar words mesh with the unfamiliar. Fascinating. Stepping closer, the story unfolds before you.

alone?

“Did you accidentally create some new god?”

Huh? You know I don’t do that stuff anymore. Anyway, try this! I think I finally got my ratios of sweet potato to pineapple right.

“Hm… it’s good.”

Are you sure? You sound very sincere right now.

“You gave me so much. I chew slowly, remem ber?”

Last…night… egg –no cake god … finally … from my … small rock– pomegranate cake … inside … appeared. Interesting. You’ve never heard of a cake god before. Is this something from the era before, the godly era?

The … elegant … air of the cake god … looked at me … with a glance … turned … and … to wards the cake’s inside … hid. Maybe you need to work on your reading skills. What kind of god hides in a cake?

Year 520, Forsaken Era, Season of Ice

“The council called me in for a meeting.”

What? Why? Didn’t they promise to leave you

True. Let me write this one into my rec ipe cabinet. Can you hand me my tiny red knife?

“Uh… the one cov ered in blue … cream?

No? I used my little pur ple knife for that one. It was going to be a blueber ry-raisin-shrub cake for you but it deflated into those brownies in the third drawer over there. It should be … somewhere near my potatoes I think. Or the yams.

“Here.”

Thanks. Ah what were they? Three eggs, 360 grams, I think, of sweet potatoes, let’s put a cake spirit here, fif–

“Did you feel that quake?”

What? The world’s always a bit turbulent, did something happen?

“Probably. Let me check something.”

Okay. Anyway, fifteen grams of pineapple, hm, does my cake spirit want a pineapple spirit’s company? The turtle-like shell of armor and some sharp, jutting spines, sunny yellow smiles and–

“Are you aware that you’re summoning spirits

!! What? Hm, oh shoot my mooncake skin is done steaming. Give me a second to rescue it. Ah!

“Here, I’ll do it. Congratulations on becoming the Council’s worst nightmare for your tenth year in a I really was on my best behavior this year though.

“I know. They’re just overreacting again. You haven’t caused any massive god eradications in years, and nothing’s gone up in that weird brew of half-illusion-half-actual flame thing you made for roasting …duck?

Hey! It was for testing notes of dreams against flavor profiles of more classically torched des serts like creme brulee. You weren’t complain ing when the pies had you floating with a tail. Or at the wings you grew from that roll cake I

made. Oh, that one was good.

“I know. But we’ll probably have to go into hiding again. At least until their tempers have cooled and they’re no longer clamoring for your head again.”

Did you at least remodel your safehouse’s kitchen yet? Or will I have to bake in your atrocity of a flame pit again? The last cake I baked in it came out with five different textures you know. Five!

Incense swirls in lazy clouds, as your call re sounds through the realms. Pick up, pick up, pick–

“Why did I hear from the high acolyte that you sang you me and a tree for your initiation rite?!”

Watch your tone there, my friend. It’s a classic. And you did yours with a butter knife so are you in any position to judge?

“I’m not saying it isn’t, but why did I have to hear this from the high acolyte? You know I can only put up with so much of the oh what a disgrace while nodding politely before my face freezes into something horrifying. Congratula tions on your initiation by the way.”

I was going to tell you but then they were trying to block my qualifications, ha qualifications, as though they can talk about those, so I had to do it fast and lo and behold, it was me and tree and [maybe actually name the very much dying god that reader decided to become an acolyte to]. Anyway, I called because I think I found a relic in my new place.

“A relic?! Really? In that frightful place?”

What better place to hide than one so horren dously re pulsive? Anyway, do you want to come over and see it?

“Of course! Can you prepare me a blindfold to protect my eyes from your hazardous kitchen though?”

… sweet potato, 15 grams … pineapple, oh, come, come a friend, pineapple god appear! You spin around, half-expecting a pineapple god to manifest. Was that the old creation technique for gods? Oh that we could have half the skies they did, draped in those billowing threads of stray magic and freehanded creations springing into playful existence.

慢慢的,我把我的小红刀切到蛋糕里。啊?神 呢?我用了这么多的力量吸引这神来怎么它就 逃了啊?3个鸡蛋,360克红薯,15克菠萝, 哎,来吧,来个朋友吧,菠萝神出现吧!你 看,我把朋友都邀请来了,蛋糕神你回来吧。 一瞬光从蛋糕里闪了一下,然后就消失了。蛋 糕神啊,蛋糕神,你知道我只会不停的打扰你 哦,就拜托了。来,再来个朋友。给你加个葡 萄神吧,葡萄好难用来做蛋糕啊,烤来烤去也 留不了多少东西。

You see, I … brought friend even… invit ed here, cake god you return … please? A flash of light… from the inside of the cake … flashed for a moment … and then … disap peared. Cake god oh cake god, you know I … only nonstop hit–bother you, so begging you. Come, again come a friend. Give you… add a … grape god, grape good hard… grapes are so hard to use… to make cakes ah, bake here bake go… no matter how you bake them … stay not many less things… there’s not much left. How many gods can be made at once? How daring, to taunt the gods. Whose fault is it that grapes are not good for baking? Are they not good for other things? ---

Slow–slowly, I put my small red knife … cut? I cut with my small red knife … into the cake. Ah? God ah? … Where is the god? I used so much strength power… energy … allure … this …god come… how come … it just … ran away? Interesting pronoun choice for a god. Can this person make gods at will? What kind of person can do that? And to frighten the gods too, what might.

Three chicken eggs, 360 grams red potato

Year 520, Forsaken Era, Season of Death

哎,another bread. “...Perhaps you were a little too overzealous in your kneading.”

*Bite*

Ok, not just a little, but monstrously overzealous.

“It would have probably made delicious noodles?”

Should that make me feel better?

“Did it?”

I don’t know. Do you want peach-flavored noo dles? I thought you wanted a cake. I swear my hand only shook once during the addition of flour. How is that enough difference to transmute cake into bread?

“Maybe you should start writing down your successful recipes for reference. Not enough to deny the spirit of baking, of course, but just enough to make the cake spirits hap py and give you cake.”

Good idea! Hm, where should I put it?

“Maybe in your recently remodeled cabinet? So that when you grab ingredients for bak ing, you can be inspired.”

!! Great idea! Can you pass me the knife? I’ll start writing to the cake spirits now.

“At least let me wash it first.”

Hurry up! Do you think the cake spirits will ap preciate my doodles? ---

Do you really want to use a blindfold? The inte rior art is a fascinating glimpse into the minds of relic-crafters and the godly age.

“I’d like to keep my aesthetics intact, thanks. Besides, you said it was carved, right? I can just run my fingers along it and feel the tex tures. And you were going to read it out loud anyway.”

…Fine. There are varying depths to the carv ings, so you might find something interesting. And don’t judge. You’re the one who gave me this blindfold anyway.

With a quick flick, you toss the pale pink blindfold, covered in magnificent soaring cranes, into the air, summoning a quick bolt of lilac, sunset lightning to char it off to the nether realm with a quick murmuring of its gift status. The blindfold materializes feather by silky feather around your friend’s face as the gift completes its ascension.

You pull your friend through your cluttered living room and into your kitchen. Hm. Maybe your aesthetics really have been warped. Somehow, there’s something more pleasing about your cabinets. Maybe it’s the way that the neon orange gruel looks like your initiation dinner. Or the fact that you might be able to trace a motif across the flecks.

You swear that the pulls have migrated, rip ples in the sleek wood gliding subtly, and one of a particularly raucous dancer with a flutter ing fan might even wink at you.

At the nod you get, you throw open the cab inet. Or maybe it opened its great maw and swallowed you. Dark and light, light and dark, within the cabinet it is all cabinet, wooden, carved, never-ending, never-beginning.

包1?我试了好多种了,牛奶味,香蕉味,桃 子味,茄子味,等等怎么还是做不出来啊? 蛋糕神无可奈何的对我说了这一句:《有些时 候,蛋糕是蛋糕。有时,蛋糕不是蛋糕。它是 面包。》

“The jagged cuts feel harried yet sure. They’re precise, even when they seem sloppy, and the entire piece pulses with a wickedly wild sort of life… how did you chance upon it?”

I really don’t know. It must be my post-initia tion luck.

“And maybe the decor is your post-initiation curse.”

Cake god, why I … make not … out cake, why can I not make cake … just make out come bread? Oh, why can I not make cake, only bread? Sometimes you can’t force yourself to become something you aren’t.

I try–tried good many types, cow milk flavor, sweet–banana flavor, peach flavor, … eggplant flavor, wait wait– etc yet still is make no out… yet still can’t make any? Ah, such dedication to the classic flavors. You wonder which cake gods corresponded to the varied flavors. Or was this god a more mutable one, who could split and reform as they pleased?

Cake god no able patience hold… cake god unable to hold patience anymore … hm cake god with an inexhaustible amount of patience to me said this line: “There are some times where cake is cake. Other times, cake isn’t cake. It is bread.” Oh! Is it possible that the narrator mistook a bread god for a cake god? The olden gods must have had a hard time with attracting followers then.

Just because most peo ple “die” post-initiation doesn’t mean initiation is actually cursed. Think about it. The relic here proves that godly creation was once so incredibly easy that people could acciden tally summon a variety of gods. So how can sharing the burden of one cause any thing so dramatic?

“The pot that met my head post-initiation would like to meet yours.”

Introductions can wait. Anyway, what did you think of the relic? Want to introduce this cake god to yours?

“Absolutely! You have to feel the con nections of this piece too–here, where the little grapes on the grape god’s head piece weave so gorgeously between the spirit realm and anterior realm… here, where the spines of the pineapple god protruding elegantly from

Does it make you want to remove your blindfold?

“Nope. My fingers can see enough.”

the neck like a crown, feel the points, how spiky they are, sharp in each realm and tied so beautifully by the bread… the cake god must be hiding because this piece has enough energy to tether them here for a lifetime.”

Does it make you want to remove your blind fold?

“Nope. My fingers can see enough. Maybe you should stay a little longer on this side for once.”

Not today. I think I’d like to

But maybe one day, I will.

Your lumpy little tart disappears so slowly, the purple-yellow swirl at the top spin ning you in circles as careful chewing sounds.

Do … do you like it?

Middle finger, thumb, pointer, thumbmiddle, pointerpinkiemiddle–“Yes.” Really? But–

“No buts. I like it. Which flavors did you use? I taste … taro? And jackfruit?”

You can taste the jackfruit?! I thought I didn’t add enough. Yeah, there’s taro and jackfruit and there’s some mango and per simmon and …

live a little longer, chase some cakes that aren’t cakes but rather bread.

I was here years ago, my feet in the muddy sand, feeling like the first practitioner of nomenclature, driftwood, clamshell, seaweed, shoreline. The names of the elements like dancing sprites against sea spray. In those days the colors had voices that darkness could not smother, and we could hear it there, in the gulls’ noisy squealing and lapping of the ebbing tide—the spectral secrets of a world unseen.

Today I walked out to the shore and found you lying there in the cold evening wind, wrapped in so many shades of gray, and hardly moving except for the heavy breath of those Pacific waves. I wanted to touch the water, that I might enter into the fluid, infinite realm and take a handful with me. But my hands were only wet and it was cold, the wind growing stronger, the night nearing. All I could see was your decaying body, your drift wood and kelp flies eating through the sargassum, the upturned crab already cut in sections by crisp, salt waves. It reminded me of something long ago, my father standing over the casket, hiding whimpers in his hands. Standing here now, watching the ocean chase the darkening sky, I begin to understand what he meant by prayer.

I take a broken shell in the shape of courage and listen: this body is a home, remembered and throw it, watch it splash.

There is no solace here. Hands changing, exchanging until the palm opening at last, with the groan of a door, to an underbrush that she wades through.

Her birthday today, so my mother thinks about Taiwan. About so much left behind. About so much left to do. About leaving. When mother leafs through old pictures, she sees an infant that she does not recognize. This must be me, she says, unremembering. Where is this baby now? Its hands remind her of chicken feet from the Feng Jia night market and eating with her school friends under the old Buddhist archway. This baby, where? Unfound, unborn, kept as a wedding ring in the old jewelry box, but thank god she’s here.

She rises from green waters to a husband with his open hand extended like a blade— what can she do but take it, flinching? At least she is here now, they say (she repeats), her fingers cut by his. But still she believes.

She believes because it is the only time she sees eyes that can meet hers and swallow her voice, and because at least God does not tell her to Speak English, goddamnit like her three sons who are angry with their mother’s language and prayers. She thinks about her sons who have grown into men too heavy to be held and too modern for religion. She asks to be forgiven, though for what she does not know.

She dresses the cuts on her hands with cloth cut from her husband’s old shirt. Later, she will brew licorice roots from the local Chinese herb shop. Licorice root tea is good for breathing. It will be good to be able to breathe a little, she thinks.

The first thing Dad says on the phone is, “What’s gotten into you?”

It’s startling how quickly Erin slips into defense mode, like an animal: palms clamming up, stomach twisting, ice pricks all the way down her spine. Even three thousand miles away, her body knows to fear the tone of her father’s voice. This, she thinks dimly through the fog of panic, is what criminals must feel like when they’re caught at gun point. Only then does it occur to her that she hasn’t actually committed a crime—at least not that she’s aware of.

“Nice to hear from you too, Dad,” Erin says, attempting to sound light-hearted. “What did I do this time?”

Usually she can afford to crack jokes with her dad, knowing he’ll return it with a jab of his own. It’s why Erin generally gets along with him, unlike with Mom, who can never seem to tell when Erin is being sarcastic or genuine. But today Dad clearly isn’t in a joking mood. “Erin, you’ve been at college for three weeks now.”

“Yeah.”

“You haven’t called your mother once.”

Erin goes still for a moment. Then she says, “I’ve been busy.”

It’s only half true. Many days Erin finds herself drowning in schoolwork and test anxiety, but just as many days Erin finds herself roaming around on campus by herself, staring at the school buildings and wondering what she’s doing. People always told her that she would have all the free time in the world when she got to college. Erin thought it might be liberating: all the free time in the world. Instead she feels like she’s drowning in it sometimes.

Dad, who knows her too well, calls her bluff: “You text me all the time.”

“That’s because you text me first.”

“She’s not very happy with you,” Dad sighs. “It’s putting her in a terrible mood.”

Judging by the weighty, disappointed tone in her father’s voice, this is where she’s supposed to feel guilty. The horrible, ungrateful wayward daughter who hasn’t even bothered to call her mother once. Erin’s pretty sure her dad is expecting her to start begging for forgiveness at once. But the only emotion Erin can conjure at the moment is a prickly annoyance. When she was younger Erin would wonder, constantly, whether there was any version of herself that Mom could be pleased with. Now Erin knows there isn’t. She’s not even at home and she man aged to piss off her mother. Mom would find a way to resent Erin even if she was on her deathbed. Now, if you’d just listened to me and eaten better like I told you to…

Erin can’t keep the frustration out of her voice when she bites out, “Well, I can’t do anything about that.”

“Just call her, Erin. It’s not hard.”

“So why doesn’t she just call me herself?”

Dad goes quiet for a few moments. Then he says, “You know how your mother is. Sometimes she can have too much pride for her own good.”

Erin knows the truth. If Mom actually cared, she would call Erin herself. But Mom hasn’t bothered to call, either, because it’s not about that; she just wants something to be angry about.

A few nights before Erin left for college, she and her mother got into a big, explosive argu ment—something about Erin not being packed yet, or about the disarrayed state of Erin’s bedroom. After Erin stormed upstairs, she lingered by the

banister and listened to her parents’ hushed whispers in the kitchen. That girl can’t get out of this house fast enough, Mom had muttered.

It should’ve hurt, but Erin just found herself agreeing. She and her mother frequently butted heads, but it had been unbearable in those last few months at home, as if the im pending knowledge that Erin would be leaving made her mother even more bothered by her presence. Erin had endured all of the nagging, all of the nitpicking, all of the criticism by telling herself that things wouldn’t be like this forever. Soon, she would be on the other side of the country. Soon, she’d have her own life away from home, away from the crushing judg ment and expectations from her parents; soon she would be free of her mother. Soon, soon, soon.

Now, though, she’s here, and Mom is still trying to dig her claws into Erin. It’s all too much at once.

“Her pride isn’t my problem,” Erin snaps. “She’s mad at me? Great. She doesn’t have to hear my voice.”

She hangs up before Dad can respond. Only now does she become aware of her roommate, Jenn’s, imploring gaze from the corner of the room. Erin offers a sheepish smile and waves her hand awkwardly. “Sorry about that,” she says.

Jenn just stares. “Was that your dad?” “Yeah. Apparently my mom is freaking out over me and now they’re both pissed.” Erin shakes her head. “They’re driving me up the goddamn wall.”

“You can always just block their num bers.”

Erin laughs. It takes her a moment to realize that Jenn isn’t laughing with her. “I don’t think I could do that,” Erin says sheepishly.

Jenn shrugs. “I have plenty of friends who have awful parents,” she tells Erin. “Some times it’s easier to just go no-contact.”

“My parents aren’t…”

Erin stops herself, unsure what she was about to say. That her parents aren’t awful? She doesn’t know if that’s true, at least not of her

mother. She thinks about all the times Mom has pointed out swimsuits that don’t fit the same on her anymore, new blemishes on her face, and how her psychology major is never going to get her a job. Before she can finish her sentence, though, her phone pings, notifying her that her clothes are done drying in the laundry room. Jenn has already moved on from the conversation, scrolling idly on her phone. Erin, however, can’t stop replaying Jenn’s words in her head as she shuffles to the laundry room. Jenn has a point; it would be so easy to just press a button and let her parents drift out of her college life. Erin is an adult now, after all. Nobody can force her to be a good daughter. She can do anything she wants to. Shave her head. Get a tongue piercing. Block her parents’ phone numbers.

For some reason, though, the idea feels alien to her, unthinkable and absurd. It crosses Erin’s mind that maybe she’s not as grown up as she likes to think she is. Erin thinks back to her first weekend at college, when Jenn took her to some frat party. While Jenn and all of her friends danced and screamed and threw back seltzers, Erin felt like she was watching herself from far, far away. I’m supposed to be having fun right now, she kept thinking to herself mechanically, like if she thought it enough times she could convince herself it was real. Then Jenn grabbed Erin by the arm and dragged her over to the drinks table, shouted at Erin to do shots with her.

After the first shot Erin allowed herself to feel, for just a moment, that she was enjoying herself, that she was living the college life like everyone else here. But then Erin did a second shot, and suddenly she found herself imagining Mom standing in the corner of the room: eyes narrowed, lips pressed into a thin line as she shook her head disbelievingly. What are you doing? You look ridiculous. And that top is way too small for you. You’re spilling out of it.

When Jenn handed her a third shot, Erin just smiled and said no, thank you, she was alright. She didn’t drink any more for the rest of the night and she asked to go home early.

Jenn hasn’t invited her to another party since that night.

Erin bends down and starts moving her dry clothes into her basket by the armful. All of the clothes are still warm to the touch, and when Erin holds one of her sweaters against her face she can smell the detergent: the same fresh-linen scent that Mom uses back home. As she sorts through the clothes she stops when she finds her favorite top half-destroyed.

It is—or, was—a baby pink corset top, with the hems adorned with a delicate lace that is now crumpled and littered with holes. When Erin first stepped out of the dressing room with it on, Mom told her the color washed her out, and Erin decided she wasn’t leaving the store without it.

There’s some irony in it, Erin supposes. That even in re bellion, she circles her mother like a moon in orbit. Did she ever even really like the top, or did she just like that her mom hated it?

There’s no such thing as darkness, she recalls distantly, only the absence of light. Times like these she wonders if she is merely the ab sence of her mother.

And now, living by herself in a college dorm with nobody to cook her hot meals or make her bed with hospital corners or carefully sort through her laundry, that absence feels larger than ever. For the first time it dawns on Erin that perhaps this is the reason she hasn’t called, after all. Because she doesn’t know what she’d do with herself if Mom knew that her daughter is a vacuous, sweeping black hole instead of a person.

Erin turns her corset top over in her hands, gingerly loops her fingers through the newly-torn holes in the lace. She’s not surprised she ruined it. She hadn’t been sure if it was machine-washable or not, but she had taken the risk and tossed it into the laundry machine anyway.

Mom would have known, she thinks. Mom would have told her. If Erin had called

her. Guilt starts to creep in at the edges of her heart, dark and ugly. Tomorrow, Erin tells herself firmly, even if it’s more to comfort herself than anything. She will call tomorrow. She will suck up her pride so that Mom can preserve her own; she will lose the battle, as she has many times before, because maybe that’s all being a daughter is, really, a constant losing battle to keep the peace.

But just when she has decided this, her phone starts to vibrate against the top of the laundry machine like a digitized heartbeat. Erin picks it up. As she brings it to her ear, she realizes that, somehow, she already knows who it is.

And sure enough—“Erin,” Mom says. Her name, nothing else.

Erin’s fingers tighten around her cell. “Hi, Mom,” she responds. Mom is quiet for just a mo ment. Then she says, “How are you? How have you been?”

There’s a split-second where Erin thinks Mom said “who”, instead of “how”, and it terrifies her. Who are you? Who have you been? Ques tions Erin has been afraid to ask herself lately.

“Good,” Erin says, and hopes it’s true. “I’ve been good.”

“What have you been up to?”

“Just, you know. Homework, classes, nothing too interesting.”

“Been to any parties?”

“A frat, a few weekends ago.”

“...Did you have a good time?” There’s dread in the pause.

“Eh.” Erin leans back against the laundry machine, looks up at the ceiling. “Not really. I didn’t drink or anything. I think I bummed every one out with how boring I was.”

“Oh, no,” Mom says, but Erin can hear the thinly-veiled joy in her voice. “That’s too bad.”

“Try to sound a little less excited about it,” Erin jokes.

To her surprise, Mom actually laughs, and before Erin knows it she’s laughing too. Their laughter echoes off the empty laundry room walls, the sounds fusing into each other.

Mom’s voice sounds an awful lot like Erin’s over the phone.

After their laughter has died down, Mom says, “People are always going to think being responsible is boring, Erin. You don’t let it get to you.”

“I won’t.”

“Have you been taking care of your self?”

“Yeah.”

“Have you been making your bed?”

“Yes, Mom.”

“Have you been doing your laundry?”

“I actually just finished a load,” Erin says. She glances down at her shirt, and before she can think better of it she finds herself confessing: “I ruined my corset top. The one with the lace. I didn’t know it was hand-wash only.”

“It’s not,” Mom says. “It’s dry-clean only.”

Erin blinks. “Really? I didn’t know that.”

“I always took it to the dry cleaner by myself.”

“Oh,” Erin hears herself say. She’s qui et for a moment. Then she says lightly, “And I thought you hated this top.”

“Well, it was your favorite top, wasn’t it?”

“Yeah,” says Erin. “It was.”

Erin considers the argument she had with Mom just before leaving for college. Before, the important part seemed to be that they’d fought. Now, Erin thinks the important part is that she can’t even remember what the fight was about.

Neither of them speak for a while, searching for the right words to say to each other, realizing at the same time that the right words might never exist. Finally Mom just asks, “Are you eating well?”

“Mom,” Erin starts, and then stops. She wants to say I miss you, but that would feel wrong, hokey somehow. It would be inauthentic—an imitation of the lives in TV sitcoms, where parents and kids always say what they mean and the conflict is always resolved in the third act.

What she really wants to say, she

supposes, is that she misses Mom so much it aches. That when she’s eating canned chicken noodle soup in the dining hall, she can only think about her mother’s miyeokguk Or that the other day, she heard somebody in a rehearsal room playing “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” on piano—or maybe it was just the alphabet—and she realized for the first time that that was why the music from Mom’s rice cooker always sounded so familiar.

If they were in a sitcom, this is what Erin would tell her mother now to make up for all of the horrible things she’s done. And her mother would have things to tell her, too: that she still makes enough food for three every night, that every day she goes into Erin’s bedroom to keep the pillows fluffed, that she wonders constantly how Erin is doing, who Erin is becoming.

And then? The two of them would forgive each other. The audience would say awww, and the lights would dim on the set, and the credits would roll.

But in the end, Erin can’t say any of this. This is not television, and they are only themselves.

What Erin does say is, “I’m eating well, Mom.”

There’s a pause, which is how she knows that her mother is rolling her eyes, and Erin has to choke back a laugh.

“You better be,” says Mom.

SRIJA PONNA

SRIJA PONNA

you come home and it’s like your bed is rooted to the same floor your posters are clinging to the same wall your cup of pens is stuck to the same desk your clothes are banished to the same shelf

but you come home and it’s also like the utensils are on the other side of the counter the bowls are in the other drawer the tv has a new remote the plant is in the other corner of the living room the parle-g biscuits are gone the bread is a brand you never saw before the tree in the garden is flowered the water comes from a pitcher not a faucet

Home one is fuzzy.

In my head it’s blue, small and humid. The silverfish shimmered in the fluorescent lights, And I crawled around the carpet when she watched weight-loss programs on TV. We were real American, weren’t we?

Home two is taller. This one had stairs and a cat I loved. The ants celebrated, trash forgotten to be taken out, And I stood on my two feet now, rushing to get her water when her mind twirled. We were the weird neighbors, weren’t we?

Home three is dim. We lived in the monsoon-stricken desert. The roaches took center stage, invisible filth clung to us, And I begged on the phone for my father to save me when I was alone. We were always miles apart.

YUSUFHome four is artificial.

We moved to the pretty foothills.

The pest control came when we had no food in the fridge, And I drove around in a car older than me, a hint of teenage freedom. We were settled in routine.

But Home five is the one that haunts me today. It’s home by necessity, home that’s legally gray. The bugs don’t bother because there’s no hot water, and I’m a little older each time I come around and see her Sitting at the table, delirium glazing her eyes, Coating her hair in a gray that mumbles her mortality.

Mom can’t be the superhero anymore. We lost. We didn’t protect our home(s). So, at night she sleeps next to the dresses And by day she sells them, Seams rips them, cuts them, discounts them, Whatever can keep her fabric woven together.

water / waterhungry / water / water / water water / water / dapplelight/ water dapplelight / water / waterhungry hungry, hungry, hungry / for? hungry / hungry / hungry silt / silt / water, and me / me, me, me, this / one /is meant For me, bite, bite, bite harder, bite harder. Come/go in. / good /

To speak about kneeling, to kneel to a god is a useless ritual. You’d be better off kneeling to fix the zipper on your girlfriend’s skirt, to tie her shoelace. She’ll look at the lopsided part of your hair and it’ll actu ally mean something to her. What else, then? You want to kiss the god’s hands? You can kiss a god’s hands, but what do gods know of tenderness? What they know is that your mouth is descending on that glittering palm to sink your teeth in. All they know is teeth. To live like a god is to be nothing but teeth, devouring outwards, devouring inwards. They’re cruel. Say then, that a god learns to love you. Sheds the tiger fur, learns to nose their way up the curve of your neck. Say they learn new kinds of reverence, say they learn to peel oranges and give you half. I still die. I run down to the After and they’re left behind with a body once learned and themselves. They can throw the body away, but then they’re still left with their hands. What is cruelty, sometimes, if not self preservation?

Then to speak about tragedy, nobody knows it better than a dandelion. Say you eat and eat and eat and drink and grow your head huge with thin white wisp, a miniscule marvelous proof of nature’s engi neering degree. You are born to waste away– you are made to be deci mated by the breeze, because decimation, for you, means propagation. There goes the next generation, borne away by unknown forces, born from your devastation. Maybe this is what you wanted, but that makes you no less naked. The sum of your life blown away, and you’re still left there among the grass. No dandelion is free from necessary tragedy–simple and benign as you are, it only takes the next wispy haired toddler with a greedy hand to rip you from the dirt and scatter you. It’s not a far fall from godship to weeds. I’m still learning the same lessons.

So step far away. Try being the house next. This is a wondrous thing. What does a house hope to accomplish? Anything it wants, it is— the meaning of its being comes built in. Does it hope to offer shelter? A house isn’t a house if it doesn’t offer shelter. When you call a house a house, you make it one. Does a house fear? Well, yes, it fears the possibility of not being a house. We all waste away eventually, but it is a pain to outlive one’s usefulness. Until then I linger— I linger and I want for nothing. That’s what I want, to want for nothing, because to be want ed is to be here, and to be here is to be lost eventually. Better to be a thing left behind than a thing lost.

That, at least, is the hypothesis. Unfortunately I’m not much of a scientist. I’ve been trying to leave you behind, dear, because the lives in which we never find each other grant us the cruel mercy of never losing each other. But I forgot that tenderness is a plague that always outsmarts us, and that we never grow immune to it. Thus my experiment yields these results to its foolish conductor– that a god learns to crouch and kiss the skin behind the ears, savors the taste of sorrow that comes prepackaged with loving things that die. That toddlers love beautiful things, that decimation is an earnest attempt to make more beautiful things. That even the house has fires that burn it back down to where it came from, a merciful act of devastation, salvation from a hundred years of slow rot. That you will always come as the god, as a toddler, as the house fire, that when I’m the orange you are the splitting of it, the euthanasia for my sick dog, the crashing and clattering of my broken plates. That even when I’m a moray eel, an ugly foul unlovable thing that’s all teeth and knows nothing but hunger, you offer me an easy tar get, you offer me flesh for my flesh. I conclude that I’m not very good at leaving you behind, dear, so I’m coming back now. Sorry about all that.

On a perfectly unassuming autumn day in Crane’s Lot, Toua flipped open a book in a cramped store sandwiched between two more flattering buildings.

His gloved fingers brushed gently over the yellowing pages, eyes darting to and fro as he skimmed the words. A new shipment had arrived the night before, and apparently, he was the best at appraising goods, the best at sifting through the fragile years imbued in old things.

He gingerly deposited the first volume off to the side and picked up a second. The white leather cover was blank, mild grime staining the edge. He thumbed through its contents, uncovering dainty illustrations on each page. Insects—beautifully rendered but nothing that particularly excited him.

Flip a page. Then another. And another. And—

The mechanical pattern of his hands stopped. His blank expression remained the same, save for the widening of his vast eyes.

There was a ladybug printed on the page, the red and black of its shell vivid even after all these years. As the breath rattled in his chest, coming out in faster and faster bursts, Toua berated himself for his carelessness. Of course there was a ladybug in a book about insects. How could he have overlooked that? His finger twitched where it clutched the corner of the book far too tightly.

It would be so easy. Just light a fire in his palm and burn through the weak paper. Almost unconsciously, his hand reached toward the top of the spine.

“Toua?” The door to the back room opened and Boonie poked his head out, long hair fluttering from the movement. “I finished checking up on storage. Do you need any help? The shipment looked pretty big.”

Toua slowly turned to meet his friend’s gaze, eyes still trembling more than he felt comfortable with. But Boonie didn’t seem to notice, smiling at him brightly with autumn-chilled cheeks.

Friend. That wasn’t the whole story any more. It was true, but it wasn’t the only truth. Toua didn’t need annoying twerps like Kia teasing him about the “gross love of his life” to admit that to himself. Still, there was something about the word friend that soothed him, that perhaps he valued over any other title.

Boonie bounded over, a child-like skip that looked the slightest bit odd with his tall frame. He leaned over Toua’s shoulder to peer at the book, immediately latching onto the fiery ladybug. “Oh, wow, that’s beautiful. It looks like it could crawl off the page at any moment.” He laughed to himself. “I almost wish it would come to life.”

Toua hummed in acknowledgment. “There are definitely books that can do that. But I’ve never liked ladybugs much myself.”

“Really? Why?”

He shrugged. “Just a feeling I’ve had for a long time.”

Toua snapped the book shut, hesitating before setting it aside. Perhaps he shouldn’t burn it after all. He’d have to pay for the damaged gloves if he did.

They walked back to their apartment together after work, night having fallen long ago. As Boonie carried their groceries inside, Toua paused by the front window, heart stuttering as he caught sight of a red origami bird—scrawled over in familiar handwriting—resting on the windowsill. He reached out slowly, turning it over in his hands. That’s right. He never ended up responding to his parents’ last letter, did he? Not for the first time, molten guilt crashed through his veins, searing him from the inside out.

The same panic he’d felt when he saw the ladybug began to bub ble. Shaking, he hurried around to the back of the apartment building, alone except for the handful of sleeping cars and the thin line of ever-watching trees. With unusually unsteady fingers, he unfolded the paper. His breath came out long and heavy as he squinted at the sheet.

He let out a sigh when he finished, urgently stuffing the letter inside the pocket of his coat.

When they were children, Yuwono hated being outside, complaining incessantly whenever Zunaira dragged them out to go hiking or swimming. Still, he’d been obsessed with the night sky, in love with the way the glow of the moon and stars reflected off his face. Toua had always felt that Yuwono fell in love too easily, even if it was with something as equally loving and ubiquitous as the midnight heavens. But even after so many years, Toua couldn’t help the way his gaze drew toward the moon.

In a way, it was the last thing he shared with them. The last thing he had in common with the people he thought he’d be around forever. Whom he hoped he would always know, and who would always know him. Friends who’d promised to stay with him eternally.

Was Zunaira still drifting off to sleep outdoors, too old and too far for her parents to drag her back inside? Was Yuwono still laughing late into the night, starlight freckles highlighting his irradiant smile? Was Hli still marveling at fireflies under the sky, or was that something she’d forgotten how to do?

Toua didn’t know.

Boonie perked up from where he’d sprawled across the couch when Toua entered. “There you are! Where did you go?”

Toua smiled weakly at him. “My parents wrote me a letter. I figured I’d read it right away.”

“Your parents?” Boonie looked startled, but he quickly hid it with a smile. “What did they say?”

“The usual.” Toua grimaced; Boonie wouldn’t know what “the usual” was. “They want me to go back to visit since it’s been… a while.”

Boonie didn’t comment on that, though Toua could tell from the way he puffed out his cheeks that he wanted to. Instead, Toua could see him deliberate, picking his words carefully. “I know family can be difficult, but I never got the feeling that you didn’t get along with them. Is there a reason why you’ve never visited?”

“It’s not them”—well, not entirely them—“There’s just a lot of people in general that I’m… that I’m not ready to meet again.”

Concern furrowed along Boonie’s brows. “I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have brought it up.”

“No, it’s all right.” Toua’s gaze wandered toward the storage closet. He could almost see the outline of a cardboard box through the door, buried behind years of noise and distraction. “I shouldn’t avoid it forever.”

“Still, don’t feel like you need to talk about it if you don’t want to.” Boonie walked over and took his hand, beaming at him kindly. “I’m a little sad I won’t get to see your embarrassing baby photos, though. My mother’s already shown you all of mine. I bet you were one of those insufferable brats who was good at everything in school.”

Toua rolled his eyes but couldn’t stop the smile from crawling onto his face. “Maybe I was, but it doesn’t matter. Hli was always smarter than me, anyway.”

“Ah, Hli! I’d really like to meet her someday. Anyone who annoys you sounds awesome.” A mischievous sparkle glimmered in Boonie’s eyes. “I bet you always tried to hide how mad you were whenever she did better than you.”

Toua felt a sting of pain as he bit the inside of his mouth. “I was… always more upset with her than I should’ve been,” he finally said.

It’d happened so many times, but Toua didn’t think he’d ever get used to waking up to the sound of screaming.

Almost by instinct, he shot up and threw himself sideways, wrapping his arms around Boonie’s shaking frame. “It’s all right. It’s all right. It’s not here. It’s not your fault. It’s all right.”

Boonie returned the embrace with trembling arms, his entire body wracked with hiccuping sobs. “It must be so awful…”

“Shh… Don’t think about it. You’re safe. You’re good. I’m here with you.”

As always, Boonie didn’t seem to hear him as a strangled whisper left his lips. “It must be so awful to die before you’re ready to go.” Another sob. “So, so awful.”

Toua resisted the urge to throw the pen at the wall. His body was filled with an unusual tension as he stared at the blank page in front of him. How many times had he tried to write a response now? He usually wasn’t this useless; all his life, he’d been known as the one who could get things done more efficiently and correctly than anybody else, even when it was unpleasant. He glared at the letter his parents had sent him, taunting him from where it sat on the bookshelf, before frowning at the pile of crumpled drafts rotting in the waste bin.

Normally, Toua spent his days off running errands and finishing off miscellaneous work, letting Boonie drag him out to town every once in a while. But although he’d planned a full schedule today, he hadn’t even finished the first task.

He leaned back in his chair with a sigh, draping a cold hand over his forehead. “I’m going to suffocate.”

With effort, he dragged himself out of the office, pulling his coat over his shoulders. He’d take a short walk to clear his mind. Just an aimless walk with no destination. As unnaturally as it came to him, Toua had always liked wandering around town with no plan in mind. When there was no destination, there were no thoughts, no words, and no worries. He could just exist and let the woes of the past, present, and future leave him behind.

Almost as if his body knew he was aching for company, Toua found himself approaching the ice cream parlor on the east side of town. Peering through the large windows of the Ice Crane storefront, he saw the familiar lanky figure of Kiarash leaning over the counter and chatting with Irene. They were the only two people inside. It was common enough to see Kia at his part-time job, decked out in his dorky bluestriped uniform, but Irene was usually helping at their father’s forge this time of day. Still, it’d been a while since Toua had spoken to either of them, and before he knew it, he found himself pushing open the door.

Kia’s head whipped up, ecstatic smile never once wavering. “Hey, welcome to—Toua!”

Irene waved their hand high. “Toua.”

He tried, and failed, to match their joy with his own wave, even if he felt a pleasant warmth spreading throughout his chest. “Hello.”

“You came just in time,” Kia chirped. “I was just telling Irene

about what Leyla wanted me to do. It’s pretty dumb.”

“It is dumb,” Irene agreed.

“Really? What did she say?” Unlike her two younger siblings, Kia’s older sister didn’t strike him as someone who did “dumb” things very often. But if Irene agreed, then…

“Bahareh started dating someone for the first time, and I know the kid, so it’s fine. But Leyla—she’s mad.” Kia grinned widely. “Did the whole thing where she tried to threaten them.”

Toua resisted the urge to snort. Kia snickered at his smothered expression.

“Right? She’s so short and unintimidating. Even when she’s mad she just looks like an an gry duckling,” he crowed. “But guess what? She asked me—me!—to go scare the poor kid next. Problem is, I’m also—”

“—unintimidating.” Toua and Irene shared an exasperated smile.

“Exactly! Just because I’m tall doesn’t mean I’m scary.”

Toua hummed in agreement. “You’re literally the most ridiculous person I know.” He huffed out a laugh when Kia pouted. “Kidding, kidding.”

Kia rolled his eyes, but he didn’t seem annoyed. “Anyway, the point is, there’s no way I’m embarrassing myself like that, even for Leyla.” He turned to Toua. “But enough of my dumb sister. How’s your sister doing?”

Toua felt his body stiffen and hoped it didn’t show on his face. He’d never intended to tell anyone about his sister, but it’d slipped out one day, like a bird breaking free from the churning in his heart.

“She’s the same as always.” He dipped his head glumly. “We don’t talk as much as we should, though.”

And I’m avoiding my entire family. He’d tell them someday; he wanted to. But Kia and Irene didn’t need to know today.

Kia looked equally sad. “Ah, I’m sorry to hear that. But yeah, I get it. It’s hard to coordinate things when you live so far away.”

Toua shrugged half-heartedly. “I’ve been thinking of visiting my hometown, but I don’t know. It never feels like the right time, but the longer I wait, the wronger it feels.”

Irene eyed him worriedly. “You don’t have to go back if you don’t want to.” They paused, seemingly in deep thought. “Although, autumn is a good time to reconnect. I’m not sure why, but the past and present, life and death, feel extra intertwined this time of year. Everything seems to change faster, and everywhere I go, the tugging is stronger.”

A deep dread settled in Toua’s stomach. “Oh… Boonie’s visions have been get ting worse recently. Do you think the season could have something to do with it?”

Irene chewed their bottom lip. “Honestly, I don’t know how either of our abilities works. But death does get restless in the autumn… So maybe.”

Compared to Kia, Toua hadn’t known Irene for very

long. But he’d heard stories about Irene’s childhood, how there’d always been some invisible force calling out to them. Places where people had died. Places where people were going to die. Where death clustered; never quite materializing but never fading either. Somehow, they always found themselves wandering to those places. As they’d grown older, Irene had gotten better at resisting the subconscious pull. But still, it was always there. Always tugging.

“Oh!” They both turned to look at Kia, whose mouth had parted in surprise. He frowned down at the counter before looking up, a serious edge to his usually jovial features. Toua barely had time to realize how uncharacteristically quiet Kia had been before the younger boy spoke again.

“My dad travels a lot, right?” They nodded. “Leyla and I used to meet him outside the house whenever he returned, and he always looked so scared walking up the path. I asked him about it once, and he told me he was afraid he’d come home one day and find us all ‘dead.’”

Toua pressed his lips together. It was a horrifying thought, sure, but— “But he didn’t mean literally dead. It was more like, what if we’d changed so much that he couldn’t recognize us anymore? Like the versions of us he’d known and loved had died.” He took a deep breath. “Anyway, maybe that’s why past and present feel weird, Irene. Literal death is restless, so the metaphorical dead in your life are coming back to haunt you, too.”