Speaking, Weeping and Sewing

By Alexandra VeriniAt the beginning of her allegorical utopia, The Book of the City of Ladies, medieval French author Christine de Pizan (1364-1430) cites the Latin proverb “God made women to speak, weep, and sew.” This proverb, she says, has historically been used by men to attack women. However, just after Christine’s efforts to repudiate antifeminist stereotypes, Lady Reason, an allegorical personification who appears to the author in a dream vision, replies that the proverb is, in fact, true. She states, “it is a fine thing that God endowed women with such qualities because many have been saved thanks to their tears, words and distaffs.” Lady Reason goes on to show how these stereotypically feminine qualities have, in fact, benefited women. If women’s words are so deplorable, why, she asks, would Christ’s resurrection have been announced by a woman? If tears are a sign of sin, why would the tears of women like Mary Magdalene have

allowed them to get closer to God? As for sewing, Reason says that it is necessary for divine service and for the benefit of all humanity. Without this kind of work, “the world’s estates would be maintained in great chaos.”

The lesson of this extended exchange at the opening of one of the earliest feminist works of literature is that the activities used to relegate women to the private and non-intellectual sphere

Women Spinning, La Cité de Dieu (The City of God), Paris, c. 1475-1480, The Hague, Huis van het boek, MMW 10 A 11, f. 69v.can be mobilized by women to their own advantage. Indeed, the rest of Christine’s book consists of stories of women from history who used their perceived weakness as a source of strength. Rather than disassociating herself from traditionally feminine activities, Christine reworks these to assert her own authority and implicate herself within a transtemporal community with women.

The use of traditionally feminine activities, sewing in particular, to intervene in sectors beyond the domestic is not unique to Christine de Pizan’s fiction. In The Odyssey, Penelope’s weaving and unweaving of the shroud for her fatherin-law Laertes keeps her suitors under control since she claims she will choose a new husband only when it is completed. In a late-fifteenth-century French manuscript of Augustine’s The City of God (a work that inspired Christine’s City of Ladies), an illuminated image shows a group of women spinning. Here, each woman’s absorption in her individual task belies the assumption

of Christine’s Latin proverb that women’s handiwork is frivolous. At the same time, the circle that the women form portrays their spinning as a communal activity. The image thus conveys a sense of the empowerment and communal agency that craftwork afforded medieval women.

There is also evidence outside of fictional representations that medieval women used handicrafts as means of building community and even of asserting political agency. One example is the nun Jefimija (1349-1405), the first known Serbian woman writer. The widow of the despot Jovan Uglješa Mrnjavčević, Jefimija retired to a monastery where she composed literary works not on parchment, as most of her male peers did, but with engraving and embroidery. Her most significant piece of writing is the Encomium to Prince Lazar (c. 1400), a shroud embroidered with a eulogy in gilded thread for Lazar of Serbia after his death in the battle of Kosovo. Intended to cover Prince Lazar’s relics, this work joins personal grief with a sense of national tragedy. Here, Jefimija used

the traditionally feminine and domestic activity of sewing, coupled with stereotypical women’s grief, to create one of the earliest works of national literature. She deployed the stereotypes that were historically used to marginalize women in order to insert herself into political history. Women more than half a millennium ago were thus actively engaged in mobilized and reworking their association with domestic activities to assert their own spiritual, intellectual and even political authority.

A similar resignification of traditionally feminine domestic production is at work in the Denny Dimin Gallery’s “Fringe” exhibition. Inspired by the Pattern and Decoration movement of the 1970s, this exhibition is also in dialogue with a more historical engagement of women and other marginalized groups with craft. By incorporating materials such as fabric, yarn, beads and ceramic and using repeating design patterns, the works in this exhibition complicate the divide between craft and high art. In doing so, they

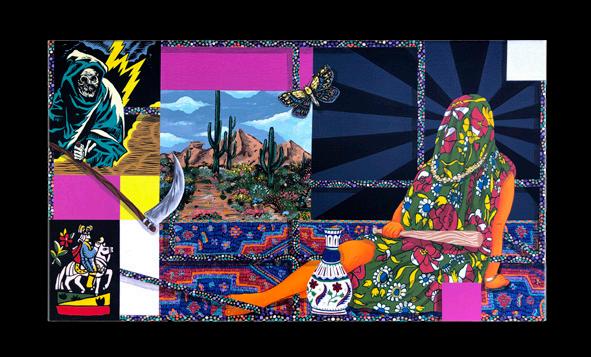

invest domestic activities, which were historically considered less intellectual than painting, with new creativity energy. Just as medieval women repurposed their marginal social role to claim authority, these contemporary artists elevate the decorative arts, which have been associated not just with women but, as Amir H. Fallah’s work shows, with non-western cultures. In doing so, like many medieval women, the artists in this exhibition bring a range of marginalized identities into public space.

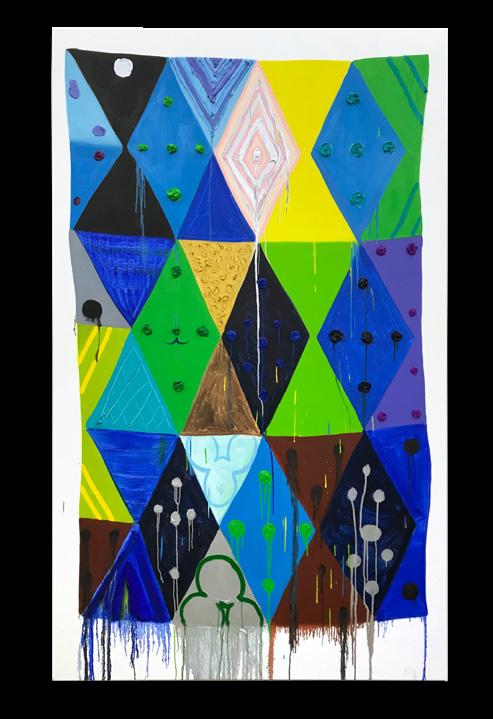

Just as Lady Reason argues that sewing has a higher purpose, these artists show the value in traditionally domestic crafts. Natalie Baxter’s Housecoat III (2021) is made of found quilts and blankets, rendering the clothing item we often associated with homemakers of the 1950s into a piece of high art. Josie Love Roebuck’s Farmboy (2020) incorporates buttons, fabric and yarn alongside oil pastel. Judy Ledgerwood more directly evokes

the medieval with the triangle pattern of Visigothic (2021), which, like much of her other work, recalls medieval heraldic imagery, as well as bejeweled pieces found at Visigothic archaeological sites. With the accompanying flower shape and pastel colors, however, Ledgerwood invests traditional chivalric imagery with a lighter and more modern tone. The variations in the decoration and drops of paint at the bottom of the canvas also convey the possibility of deviation from the pattern, a concrete visual expression of the thinking behind many of the works in the exhibition. Amanda Valdez arranges embroidery and fabric on canvas in a pattern that evokes abstract painting but from a decorative standpoint. Max Colby’s They Consume Each Other (#1) (20192021) consists of works made of fabric, beads and sequins displayed on glass stands that evoke cake stands but also statue pedestals. In this choice of medium and display, Colb blurs a line between domestic work and fine art that shadows the traditional

line between male and female. Cynthia Carlson’s Jacob’s Ladder (1976) intermingles painting techniques with the decorative arts by using acrylic on rag paper in a manner that evokes stitching. As it recalls a biblical story, the painting’s title conjures the ways in which medieval women used sewing to engage in spiritual life and visualizes the capacity of a domestic art to intervene in spiritual history.

Just as medieval women reworked traditional associations with their gender to assert their own worth, the artists in this exhibition resignify the association of crafts with the frivolous and the nonintellectual. In doing so, they also revalue the women and communities of color often linked to the decorative arts. Looking across time, we can see how artists have and continue to use the means available to intervene in artistic and political discourses. In doing so, they, like Christine de Pizan, create spaces for their own identities within discourses that had excluded them.

EXHIBITION CHECKLIST

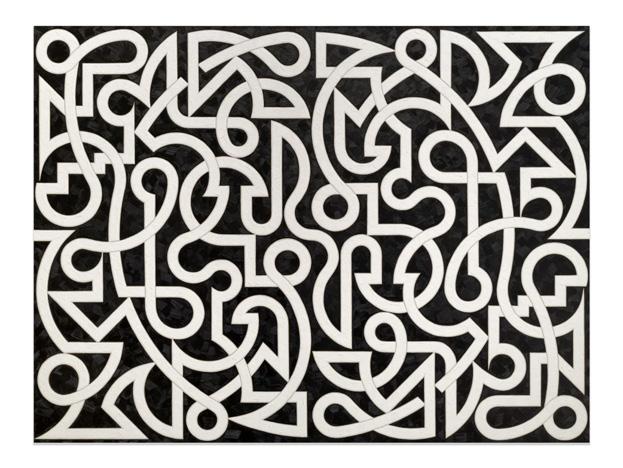

1. Valerie Jaudon

Arpeggio, 2020

Oil on canvas

63 x 84 in/160 x 213 cm

Photograph Steven Bates Courtesy DC Moore Gallery

2. Pamela Council Relief 19, 2021

Silicone tiles on wood panel with metal frame

34 x 34 x 2.5 in/ 86 x 86 x 6 cm

Courtesy Denny Dimin Gallery

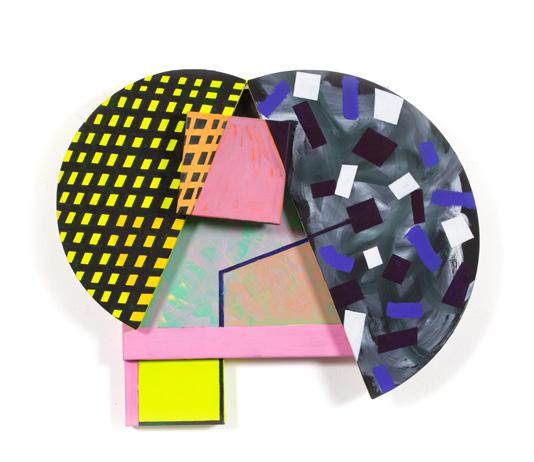

3. Cynthia Carlson

More Alarming Rumors, 2021

Oil on (5 attached) canvases

21 x 24 x 4 in/53 x 61 x 10 cm

Courtesy the Artist

4. Ree Morton Hinkle Dink, 1975-76

Celastic, wood, electric bulb and electric cord

15.25 x 17 x 3 in/39 x 43 x 8 cm

Courtesy Alexander and Bonin

5. Natalie Baxter Housecoat III, 2021

Found double wedding band quilt, found baby quilt, graphic t-shirt, hospital receiving blanket, used clothing, fabric, fringe, plastic zipper

53 x 25 x 9 in/135 x 64 x 23 cm

Courtesy the Artist

6. Amir H. Fallah

Reap What You Sow, 2021

Acrylic and canvas

18 x 32 in/46 x 81 cm

Courtesy Denny Dimin Gallery

7. Josie Love Roebuck Farm Boy, 2020

Screen-print ink, buttons, fabric, oil pastel, and yarn on un-stretched canvas

20 x 20.5 in/51 x 52 cm

Courtesy LatchKey Gallery

8. Judy Ledgerwood Visigothic, 2021

Oil and metallic oil on canvas

76 x 46 x 2.5 in/193 x 117 x 6 cm

Courtesy Rhona Hoffman Gallery

9. Amanda Valdez Sweet Trouble, 2020

Embroidery, hand-dyed fabric, and fabric on canvas

36 x 32 in/91 x 81 cm

Courtesy Denny Dimin Gallery

10. Cynthia Carlson Jacob’s Ladder, 1976 Acrylic and price tags with string on rag paper

26 x 34 in/67 x 86 cm

Courtesy the Artist

FRINGE

July 8 - August 20, 2021

11. Future Retrieval

Marbled Vignette, 2021

Wood, cut paper, ceramic

35 x 17 in/89 x 43 cm

Courtesy Denny Dimin Gallery

12. Max Colby

They Consume Each Other (#1), 2019-2021

Crystal and plastic beads and sequins, found fabric, trim, fabric flowers, ribbon, costume jewelry, polyester batting, thread, glass stands, custom pedestal. 40 x 40 x 66 in/102 x 102 x 168 cm

Courtesy the Artist

(Not Pictured)

Justine Hill

The Arch, 2021

Acrylic, and paper on canvas

116 x 102 in/295 x 259 cm

Courtesy Denny Dimin Gallery

Natalie Baxter, Cynthia Carlson, Max Colby

Pamela Council, Amir H. Fallah, Future Retrieval

Justine Hill, Valerie Jaudon, Judy Ledgerwood

Ree Morton, Josie Love Roebuck, Amanda Valdez

All artwork © the Artist. Text © Alexandra Verini.