Dutchess County Historical Society 2024 Yearbook – Volume 103

Executive Editors

Bill Jeffway

Melodye Moore

William P. Tatum III, Ph.D.

Rick Levitt, Editor

Aidan Chisamore, Production Editor

The Dutchess County Historical Society is a not-for-profit educational organization that collects, preserves, and interprets the history of Dutchess County, New York, from the period of the arrival of the first Indigenous Peoples until the present day. Published annually since the 1914 issue.

The Dutchess County Historical Society Yearbook does not assume responsibility for statements of fact or opinion made by the authors.

©Dutchess County Historical Society 2025

Dutchess County Historical Society

6282 Route 9, Rhinebeck, NY 12572

Email: contact@dchsny.org www.dchsny.org

All cover images are from DCHS Collections unless noted otherwise.

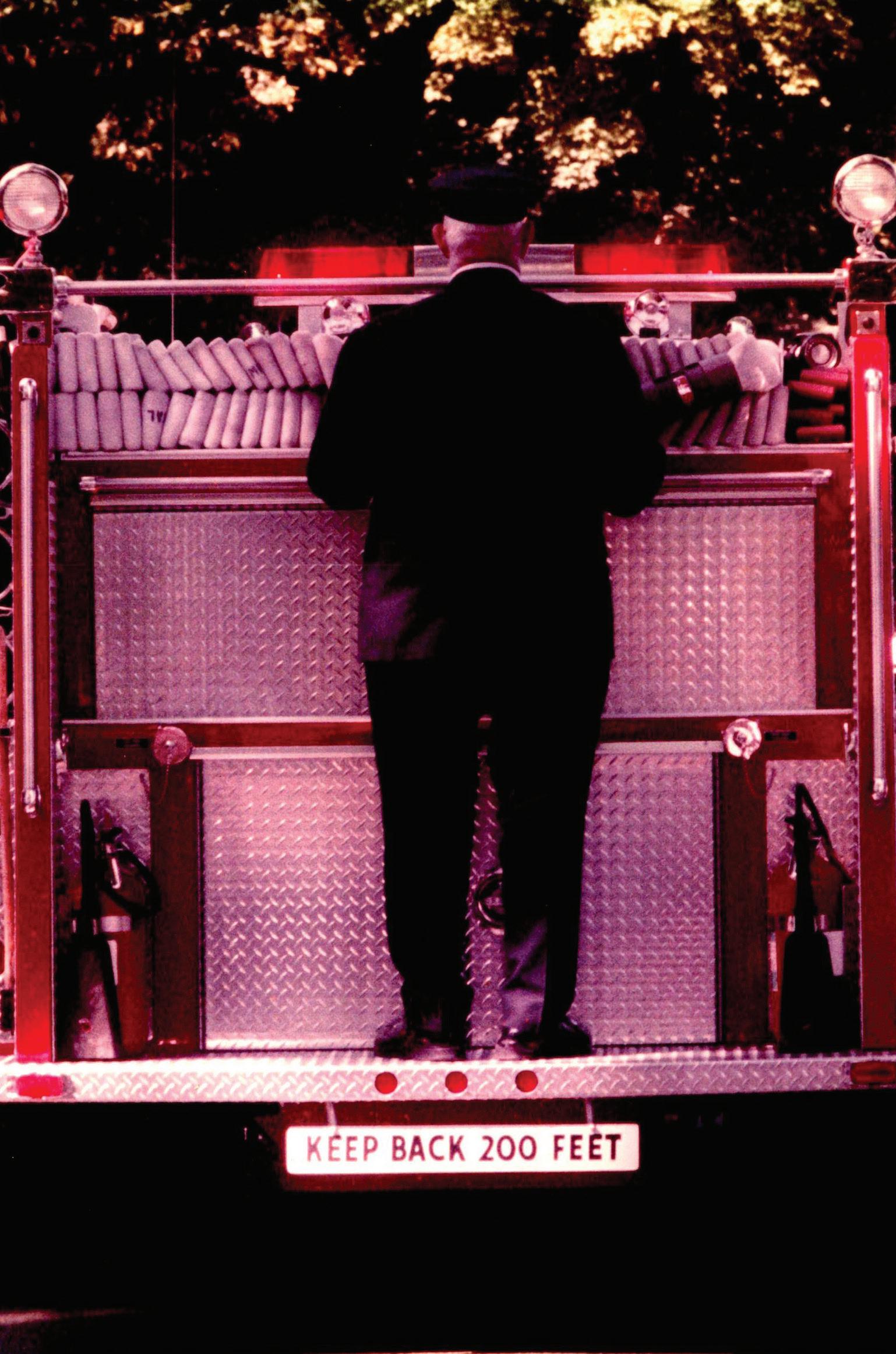

Against the backdrop of pageantry and parades lies the always present risk that firefighters expose themselves to harm 24/7. Firefighters run towards danger and are often first on the scene when an individual, a family or a community suffers loss and devastation. From the cat in the tree to transformative national catastrophes, firefighters demonstrate a selfless caring for the community that makes them true heroes. This yearbook is gratefully dedicated to the Dutchess County men and women, past, present and future, who are willing to sacrifice themselves for the greater good of their communities.

When I am called to duty, God, wherever flames may rage; Give me strength to save some life, whatever be its age. Help me embrace a little child before it is too late, or save an older person from the horror of that fate. Enable me to be alert and hear the weakest shout, and quickly and effectively to put the fire out. I want to fill my calling and to give the best in me, to guard my neighbor and protect his property. And if according to your will I have to lose my life, please, bless with your protective hand my children and my wife. Amen.

The Dutchess County Historical Society extends its sincerest thanks to DeWitt Sagendorph, Kyle Pottenburgh and Woody Dierze, members of the Board of Directors of the Firefighting Museum of Dutchess County, for their expertise in all things relating to firefighting, and their willingness to share that knowledge with us.

With gratitude and appreciation to everyone, past and present, who have, or are serving Dutchess County in the firefighting community to the benefit of all Dutchess County residents.

Rob & Sue Doyle

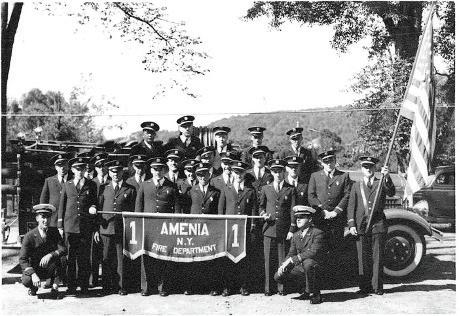

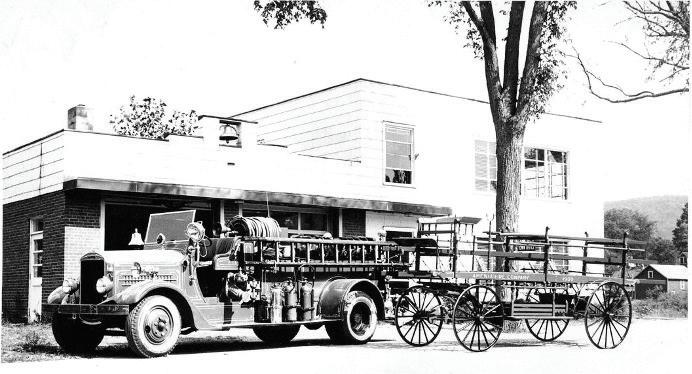

Amenia Fire Department

Arlington Fire District

Beacon Fire Department

Beekman Fire Company

Chelsea Fire Company

Chelsea Fire District

Dover Volunteer Fire Department

Dutchess Junction Fire Company

East Clinton Fire Department

East Clinton Volunteer Fire Dept.

East Fishkill Fire District

Fairview Fire Department

Fishkill Village Protection Engine Co.

Glenham Slater Chemical Engine Co.

Hillside Fire Department

Hughsonville Fire Department

Hyde Park Fire Department

LaGrange Fire District

Milan Volunteer Fire Company

Millbrook Fire Department

Millerton Fire Department

New Hackensack Fire Company

New Hamburg Engine Company

Pawling Fire Department

Pine Plains Hose Company

Pleasant Valley Fire Department

City of Poughkeepsie Fire Dept.

Red Hook Fire Department

Rhinebeck Fire Department

Rhinecliff Fire Department

Rombout Fire Department

Roosevelt Fire District

Stanford Fire Company

Tivoli Fire Department

Union Vale Fire Department

Wappingers Falls Fire Department

Wassaic Fire Company

West Clinton Fire Company

List taken from www.dutchessny.gov/emergency-services

On August 3, 1903, a fire company was organized in Dover Plains and was known as the J.H. Ketcham Hose Company. There were 60 uniformed members under the direction of John A. Hanna, the newly elected Fire Chief. In 1904 Congressman John H. Ketcham donated two hose carts. These carts were drawn by ten men and could only be used in the village, where a hydrant district was installed a few months before the fire company was organized. In 1927 the fire company would purchase their first motorized fire truck, a 1927 Seagrave Suburbanite.

Today, JHK operates two fire stations in Dover Plains and Wingdale and provides fire protection to the Town of Dover. Fire Apparatus include a 2014 E-One Pumper/Tanker, 2014 E-One Rescue/Pumper, 2019 E-One 100’ Quint Aerial, 2023 E-One Pumper/Tanker, 2017 Alexis F-550 Brush Truck, 2013 F-250 Utility Truck, 2024 Chief’s Vehicle, 2017 Deputy Chief’s Vehicle and a 2022 Argo Wildland Fire & Rescue UTV. Specialized rescue equipment includes Hydraulic and Battery Operated Holmatro Rescue Tools, Para-Tech Struts and Air Bags.

Thank you to past and present members of the J.H.K. Hose & Ladder Co., Inc. for their endless dedication, bravery and service to Dover’s community with special thanks to current President and Former Fire Chief Brian Kelly for preserving our town’s rich history.

Karen H. Lambdin & Mark K. Morrison

RIn honor of the first responders of The Rhinebeck Fire Department who, since 1834, have “answered the call.” Elijah & Christiane Bender the staff of Foster’s Coach House Tavern

Thank you to the LaGrange Fire District Volunteers for your many years of service.

We are deeply indebted to you.

Many Thanks, Family of E. Stuart Hubbard Jr. (far left)

LRecognizing members of the Milan Volunteer Fire Department, Inc. for their sacrifice and service.

Thanks for keeping the residents of Milan safe.

Bill Jeffway & Chris Lee

MAl & Vicky LoBrutto

In recognition of the dedicated service from all members, past and present, of our historic Beacon Fire Departments

Tompkins Hose, Mase Hook & Ladder, Beacon Engine Co. Congratulations on the opening of your new headquarters.

BPeter & Anne Forman

On several occasions we have personally witnessed volunteers of the West Clinton District in action and the professionalism exhibited could not be higher So far as the East Clinton District, the fact that this department was honored as DC EMS Agency of the year in 2023 says it all! So, a big shout out to each and every member, thank you all for your personal service and sacrifice of time and energy protecting the citizens of our town and surrounding communities, we are truly blessed to have you!

CJim and Lori Brands

Supporting the brave efforts of the Dutchess County Firefighters

Mid-Hudson Antislavery History Project www.mhahp.vassarspaces.net

DIn recognition of Fishkill’s Protection Engine, Rombout and Slater Chemical Fire Companies who keep Fishkill safe Thank you for your service. The Fishkill Historical Society

Thanks to all the current and past members of the Hughsonville Fire Department for their brave and unselfish service to our community.

N & S Supply LLC

HThank you to the Hyde Park Fire Department for being ready to help Hyde Park residents in their times of need.

Christine Crawford-Oppenheimer

HPNorth East/Millerton

In recognition of the members of the Millerton Fire Company and the North East Fire District. Thank you for keeping us safe.

NorthEast-Millerton Library

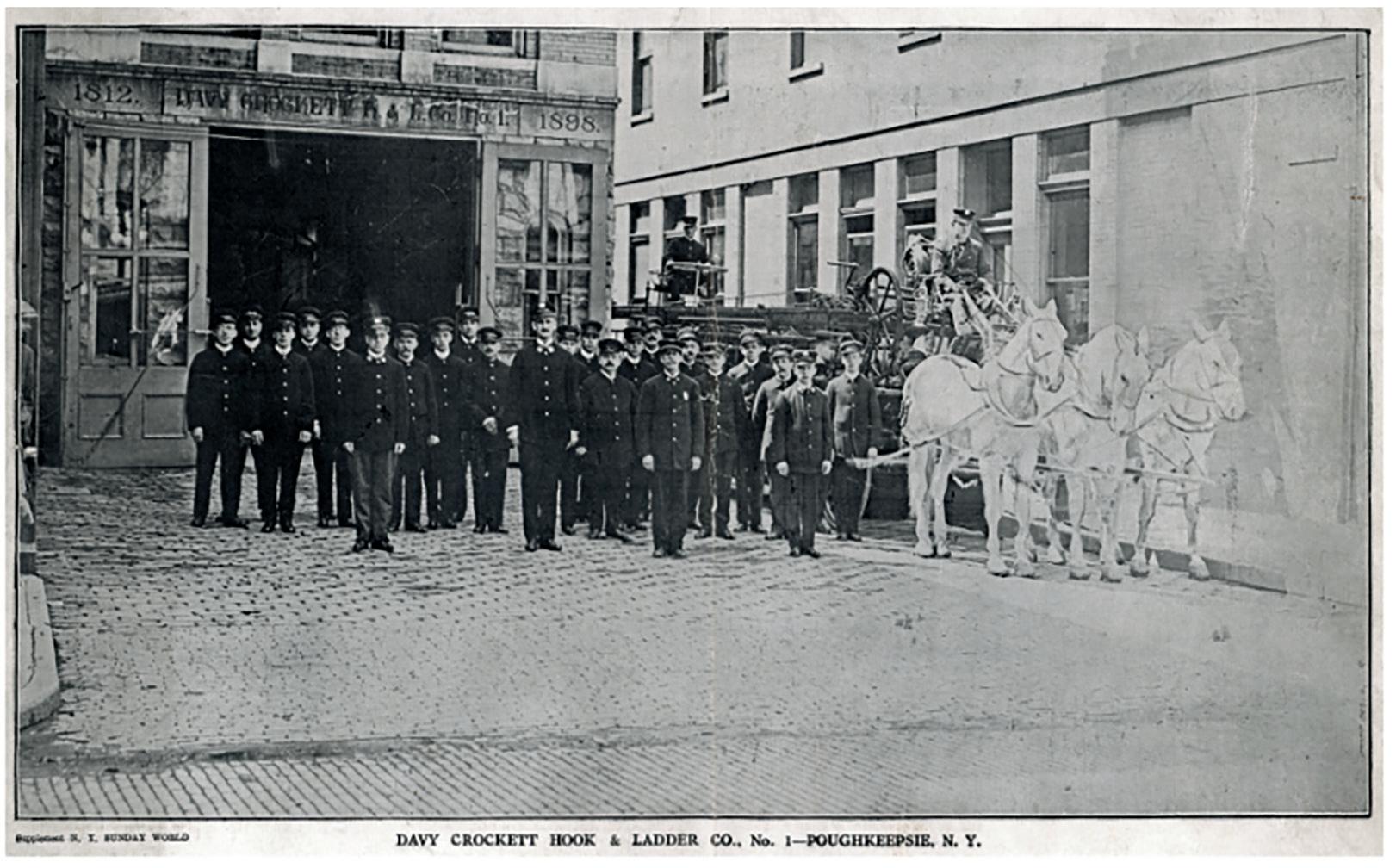

NEA tribute to the City of Poughkeepsie Fire Department

Formerly the Cataract Steamer Co., the Davy Crockett Hook & Ladder Co., the Lady Washington Hose Co., the Niagara Steamer Co., the O.H. Booth Steamer # 2 Co., the Veteran Firemen Co., and the Young America Hose Co. and its members, active career and volunteer. We extend our gratitude for your years of dedicated service to the residents of the Poughkeepsie community.

PDr. & Mrs. Benjamin S. Hayden III

In memory of Joseph Miraglia #69 City of Poughkeepsie Fire Department.

Thomas M. Cervone, Member CR Properties Group LLC

PIn honor of the Red Hook Fire Company

Thank you for being ever alert.

The Klose Family, Echo Valley Farm

RHIn honor of the members of the Rhinebeck, Hillside and Rhinecliff Fire Companies for their sacrifice and service. Thanks for keeping the residents of Rhinebeck safe.

Lenny Miller and Melodye Moore

RWith gratitude to the members of the Staatsburg Fire Company – Organized 1894 Renamed Dinsmore Hose Company – 1909 Now Roosevelt Engine Company #4.

Andy & Andrea Villani

SIn recognition of the dedicated service of all members past and present of Stanford Fire Company No. 1, Inc. as well as all fire service volunteers throughout Dutchess County. Always Ready

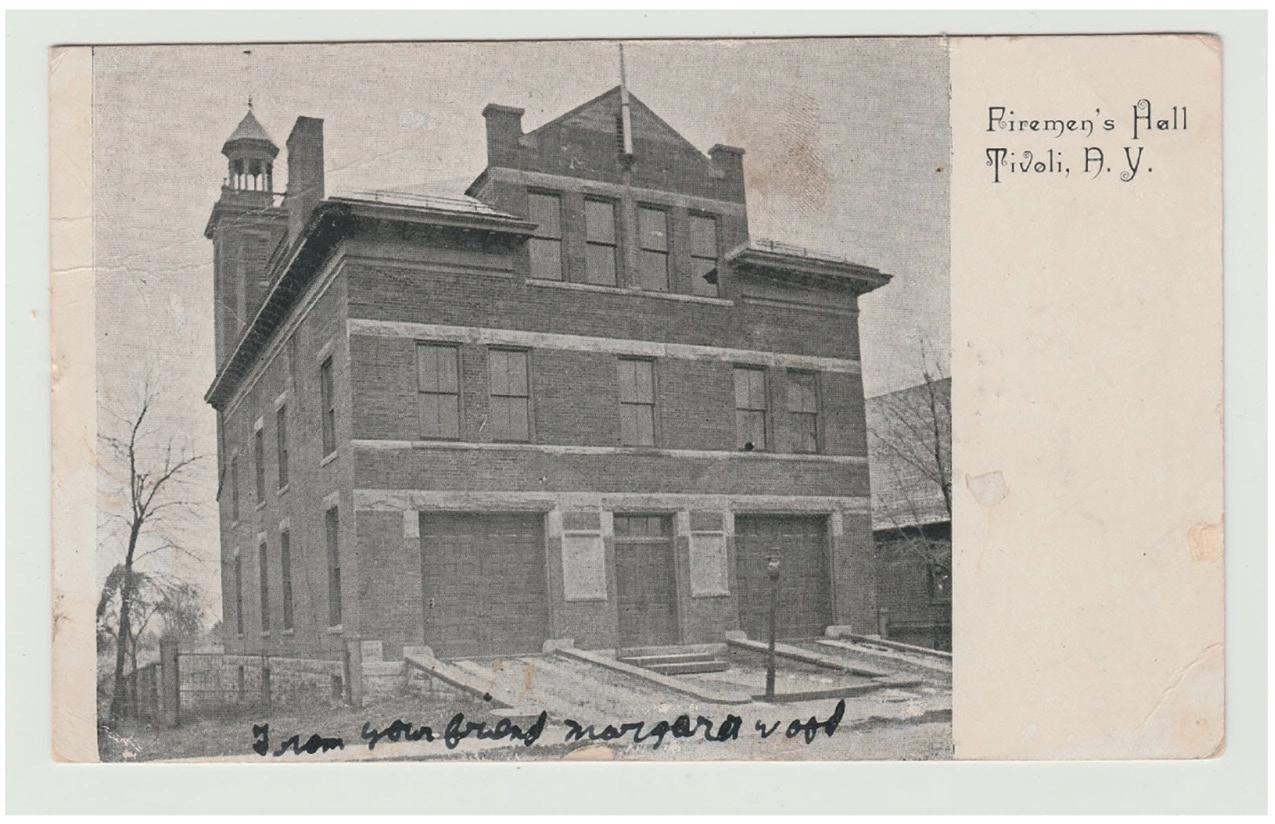

Hats off to the members of the Tivoli Fire Company past, present and future.

White Clay Kill Preservation

TIn recognition of our volunteer Union Vale Fire Company, Inc. members, past and present, for their dedicated service to the Town of Union Vale.

Town of Union Vale Historian

UVOur committed volunteers are here to assist in any type of emergency situation.

WWith gratitude to all the volunteers who give their time to the Wappinger community, including past and current members and auxiliaries of the Wappinger Fire Companies: Chelsea, Hughsonville, New Hackensack, S.W. Johnson Co., and W.T. Garner

Marcy L. Wagman

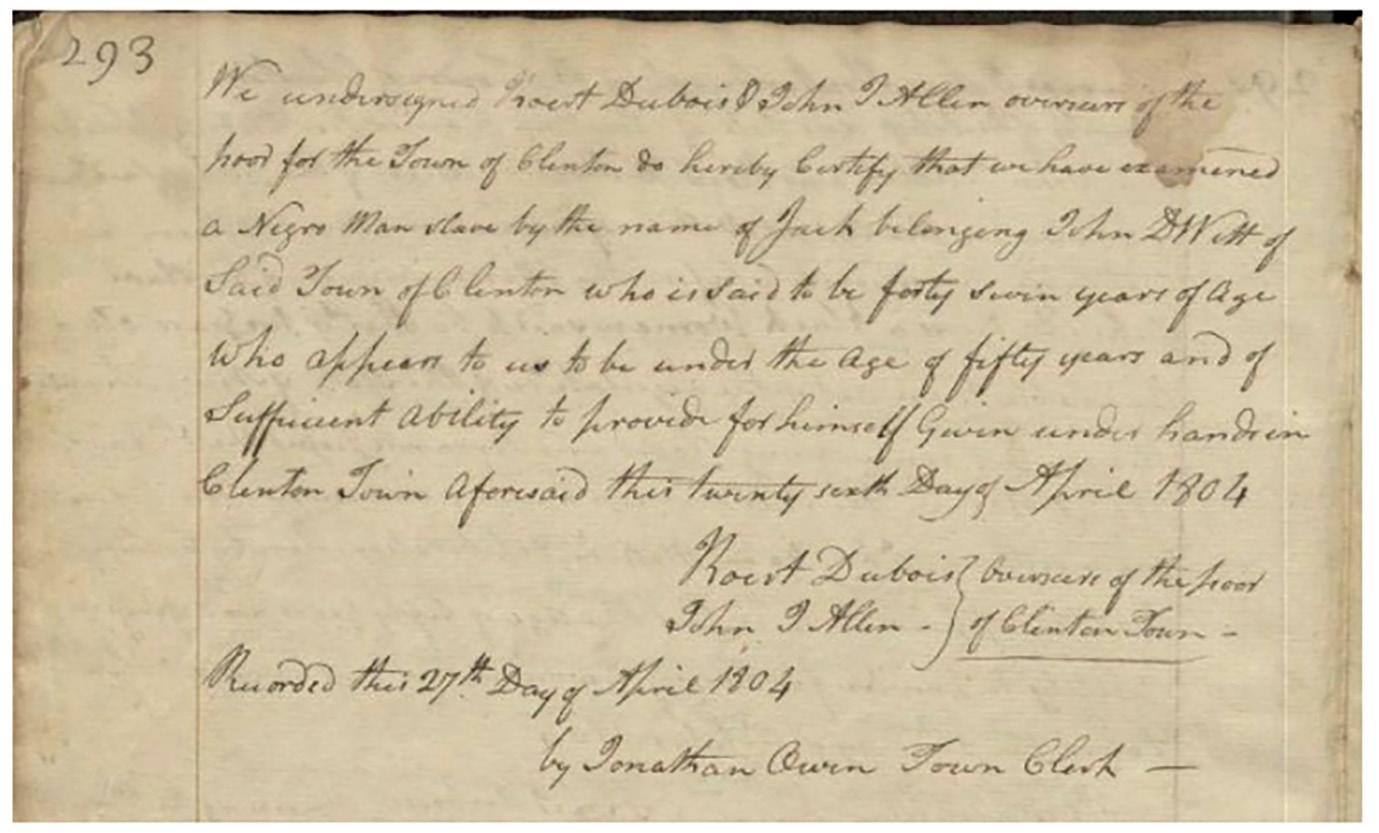

“Avoided,

Shunned, and Abhored:” Two Stories of Common People Using the Courts in Early 19th Century Dutchess County by Georgia Herring

Historian of the Dutchess County Poorhouse

Virginia A. “Ginny” Buechele, a lifelong resident of Dutchess County, passed away peacefully on December 29, 2024, after a fulfilled life that touched many within her community. Born on September 18, 1946, in Poughkeepsie, to the late Eugene R. Buechele and Alice M. (Hawkes) Buechele, Ginny was known for her vibrant spirit, her dedication to historic preservation, and her unwavering love for her family. Her 20 years of work to preserve the Dutchess County Poorhouse cemetery in the Town of Washington earned her the sobriquet “The Dutchess County Poorhouse Woman.”

Ginny attended Arlington High School, graduating with the class of 1964. Her pursuit of knowledge and passion for law led her to complete the Marist Paralegal program in 1998, which became the foundation of her professional career. Her work as an administrative assistant and paralegal was marked by dedication and excellence, paving the way for her significant contributions to her community upon retirement. She served two terms as a Fairview fire commissioner.

Ginny’s family roots were a source of pride and a wellspring of her lifetime achievements. She was among Dutchess County’s foremost

genealogists, a path that eventually led her to research the Dutchess County Poorhouse. Beginning in 2003, Ginny became the foremost advocate for the study of the forgotten county institution’s history and the preservation of the attached burial ground on Brier Hill, which contained the remains of hundreds of poorhouse residents interred between the 1860s and the 1950s. In 2004, Ginny’s contributions were honored by The Dutchess County Historical Society, with the presentation of The Helen Wilkinson Reynolds Award, and the National Society of The Daughters of the American Revolution recognized her outstanding work in historic preservation in 2006.

Ginny’s years of effort came to fruition beginning in 2020, when Dutchess County Commissioner of Public Works Bob Balkind worked to rehabilitate the burial ground site for public visitation. County investment included the removal of intrusive vegetation, creation of a new access road, and a regular plan for maintenance. Ginny contributed to the creation of interpretative signage and campaigned for a memorial marker, both of which were installed in 2022.

Ginny’s life was a tapestry of community activism, family genealogy, and treasured moments with her loved ones. The impact of her work has ensured that the Dutchess County Poorhouse site and the records of the institution will be preserved and available to the public for generations to come.

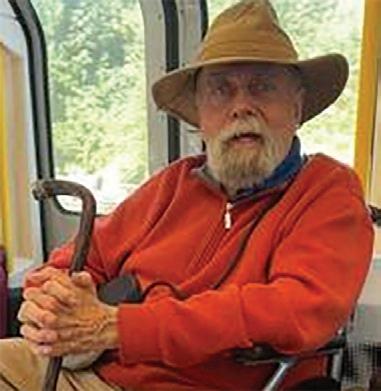

David Greenwood, a resident of Millbrook, passed away on December 23. Born in Putnam County, he had a fascinating lineage, descending from both early English immigrants and Indigenous Peoples of the MidHudson Valley. David earned a Bachelor’s Degree in Art Education at the State University of New York at Buffalo and a Master’s Degree at SUNY New Paltz, where he was later named an outstanding alumnus. He brought his love of art and history to his career with the Carmel Central School District, where he worked from 1967 to 2004. He went on to teach Art History and Aesthetics for another seven years at the Millbrook School.

David and his wife Nan moved to Millbrook in 1984 and took up residence in the Philip Hart house, one of the oldest houses in the village. Together they threw their passion for historic preservation into ensuring the highest possible stewardship for this important local treasure. This same passion for local history and historic preservation led David to serve on the boards of landmark preservation societies in both Putnam and Dutchess County, and for many years he was an overseer of Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts.

David’s talent as a historian found him wearing many hats. He was the historian for both the Village of Millbrook and the Town of Washington. He served as the historian for St. Peter’s Episcopal Church and was instrumental in the creation of the Museum In The Streets Public History Project in Millbrook. In 2022, he was awarded the Edmund J. Winslow Local Government Historian Award of Excellence in recognition of the beloved annual historic calendar project which he led for 28 years. In 2024, he was honored at a Millbrook Historical Society meeting for his decades of service. May 16, 2024, was designated David Greenwood Day in the Town of Washington.

A longstanding member and supporter of the Dutchess County Historical Society, David served on the Board of Trustees from 19861989 and again in 1994. He served as vice president of the organization in 1990 and 1993-1994. David was a proud member of the society’s Black History Committee, which focused on the discovery and study of the lesser-told stories of Dutchess County’s African American population.

David’s long and diverse commitment to local history and historic preservation was exceptional. We extend our sincerest condolences to his family.

Julius Gude, a resident of Poughkeepsie, passed away on August 9 at the age of 89. Born in Asker, Norway, he moved to the United States in 1960 and received his BS and MS in Mechanical Engineering at the University of Colorado in Boulder. Julius moved to Fishkill in 1963 to work for IBM. He retired from IBM in 1992 only to find that retirement was not fulfilling and returned to work for Micrus and then Philips until 2000.

His second retirement was a great blessing to the Dutchess County Historical Society, as it gave him the time to share his many talents as a hard working and reliable member of the Board of Trustees from ? to ?. His engineering background made him a knowledgeable chair of the Buildings and Grounds Committee. Julius loved woodworking, and he and his wife Carla lived for many years in an old Dutch farm house in the Town of Lagrange where he learned the hard way about what it takes to preserve a historic building. He brought these insights to the society’s stewardship of the Glebe House in Poughkeepsie. Julius was a passionate supporter of the society’s annual yearbook, and he and Carla were regular sponsors of its publication.

Julius will be remembered by his friends in the Dutchess County

Historical Society as the ideal board member – ever kind and gracious in demeanor, quick to offer positive ideas and suggestions, and never failing to follow through on any commitment he made.

Our sincere condolences are offered to his family.

Thomas John Usher 86, of Poughquag passed away on Thursday September 5, 2024, at Vassar Brothers Medical Center. Thom was born on November 2, 1937, in New York City to Thomas & Helen (Mulligan) Usher. He grew up with his brother Sean at Mt. Loretto orphanage, on Staten Islan. In 1955 Thom enlisted in the US Army, a specialist third class, he worked in the 82nd Construction Engineers. Thom was a proud solider and this experience helped shape his life.

In 1959 Thom met the love of his life, April Ann Sprague. They would marry at St. Thomas the Apostle Church in Woodhaven NY, on June 10,1961. The couple settled in Cypress Hills in Brooklyn to raise their family. Thom was the owner and operator of Cypress Cleaners and then The House of Usher wholesale outlet in Brooklyn. Thom moved his family to Dutchess County in August of 1979 and operated Summit Security in Beekman until his retirement. His love for history and learning led him to return to school and earn an associate’s degree, graduating in 2001 from Dutchess Community College.

In 2002 Thom was appointed Town of Beekman Historian, a post he

held for 12 years. He worked with other town historians to preserve the history of the Hudson Valley. He often worked with the Boys Scouts, Eagle Scouts, and Girl Scouts on projects to help preserve and beautify our towns and created and sewed period costumes to help bring history alive during Memorial Day parades and 4th Grade reenactments. He worked on restoring the Mill House in Poughquag in hopes that one day it could become a town museum. He researched and collected photos, documents, and stories to be placed in a published book about the town of Beekman. In April 2011 his dream of becoming a published author became a reality, completing Images of America-Beekman, a book published and distributed by Arcadia Publishing Company.

Following the conclusion of his service as town historian, Thom continued to play an active role in Beekman history. He was instrumental in commemorating the centennial of the United States entry into World War I in 2017 and in the 2018 Year of the Veteran Programming throughout Dutchess County. Thom eagerly shared his expertise on Beekman and his extensive photograph and postcard collection to support other projects. Immediately prior to his passing, Thom was supporting Dutchess County’s preparations for the 250th Anniversary of American Independence by sharing research on the Old Upper Road, which connected Eastern Dutchess to the Hudson. His work will continue to inform generations of Dutchess County residents to come.

Bill Jeffway, Executive Director

Calendar Year 2024 was our first full year in the Rhinebeck location. We are pleased to say that the larger, open space and easier access has improved our community engagement on all fronts of our varied “society” of our members, donors, business sponsors, collections donors, and a growing paid staff and volunteers. For example, the 38 items received as new collections responsibility in 2024 was triple the general average in the recent past.

In general, since our 2014 centennial, DCHS has had an annual operating budget of around $70,000 with a goal of breaking even. Over time, the break-even goal was increasingly hard to reach as ideas like our gala awards dinner were losing favor with the general public –especially after COVID.

The great news is that our 2024 operating budget had a breakeven goal just in excess of $100,000 and we ended with a small surplus. Our increased spending (and fundraising) has intentionally been focused on the perpetual care, management and interpretation of collections, our sacred trust.

DCHS has had a successful partnership with Vassar College’s Office of Community Engaged Learning. Through those contacts (and supported by member and donor generosity) we have been fortunate to appoint Aidan Chisamore (Vassar College, 2024) as Collections & Archives Manager, which became a full time position going into 2025. New approaches are bringing us new levels of support, for example:

‒ The fifth annual online auction brought record revenue.

‒ The Historic Preservation and Awards was a record in turnout and revenue.

‒ A new and successful offering has been uniquely tailored, generously funded research projects.

‒ Rob and Sue Doyle’s extraordinary $100,000 gift (based on raising the equivalent in match) was met ahead of schedule.

We are approaching the point where around $20,000 in annual income may be relied upon through the combination of our own endowment build, and the perpetual gift from the Denise M. Lawlor Fund, both of which we receive through Community Foundations of the Hudson Valley.

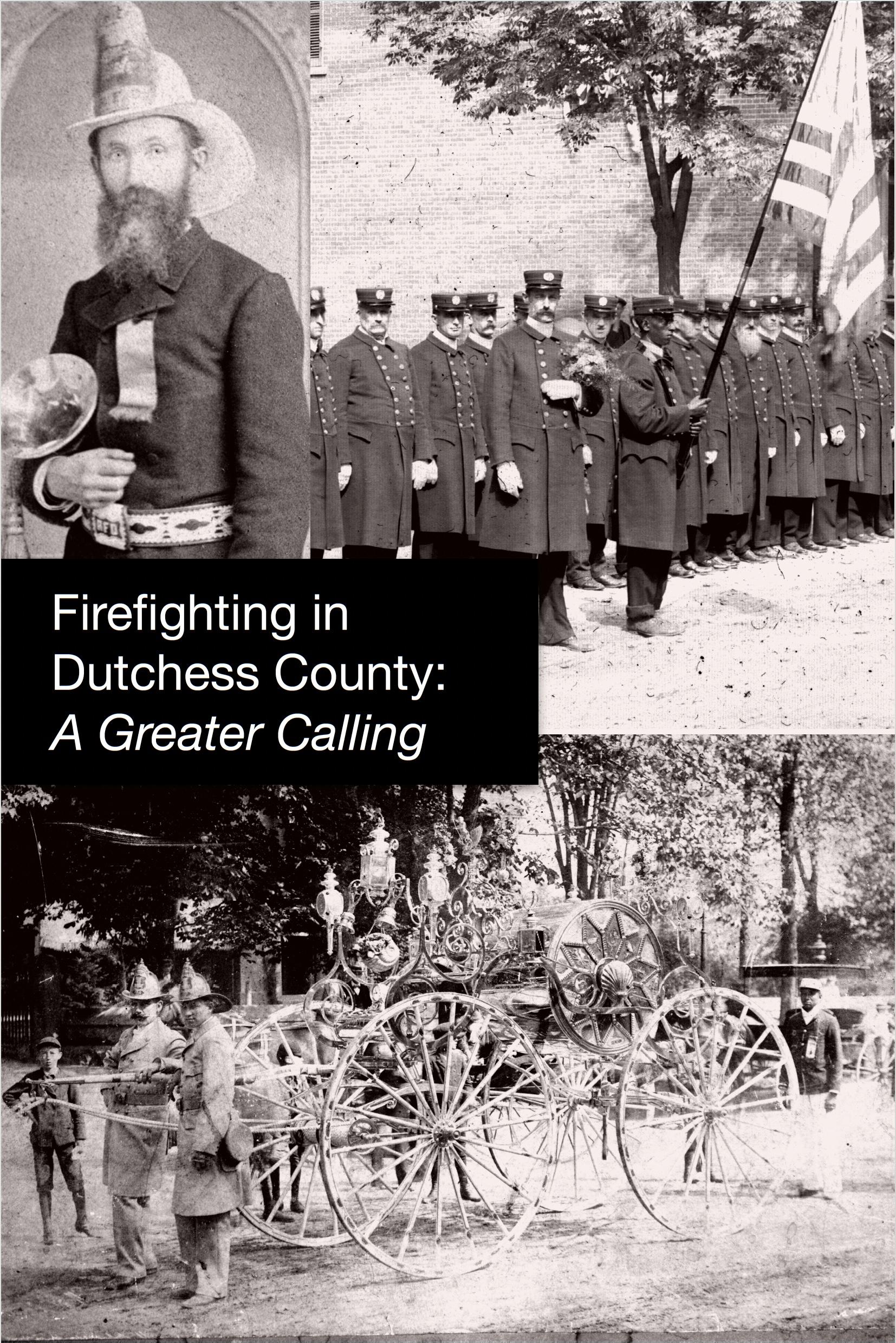

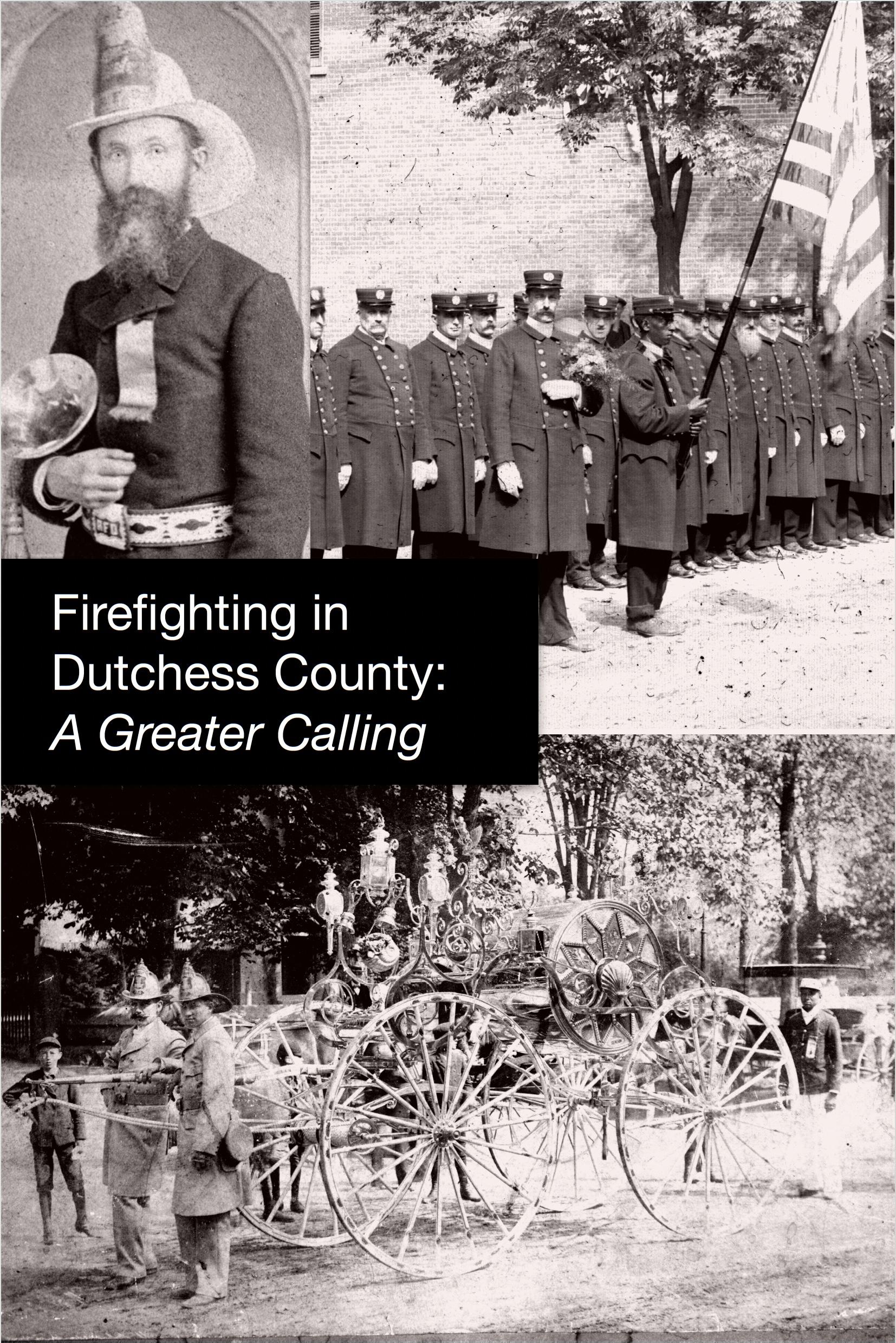

Among our most visible work in 2024 has been telling the stories of those involved in the essential service of firefighting. Prompted by a significant collections gift from the Rhinebeck Fire Department, we developed the traveling exhibition, Firefighting in Dutchess County: A Greater Calling, in partnership with the Rhinebeck Fire Department and the Firefighting Museum of Dutchess County. The exhibition was featured at the inaugural opening of the museum at the Dutchess County Fair in Rhinebeck and is available through the museum group to be featured locally. The topic is the Forum topic in the 2024 DCHS Yearbook, remaining New York State’s longest-serving historical journal.

September 2024 was the bicentennial of the local visit of Major General Lafayette. In an effort to find creative ways to bring local history to life, DCHS worked with the Bard College playwright D N Bashir to create a historical fiction performance. We started with the historical fact that a Town of Washington free Black couple, Tom & Jane Williams, named their newborn son Lafayette Williams at the time of Lafayette’s visit. The performance examines what the concept of liberty and what Lafayette may have meant to the couple at a time as New York was still some years from abolishing slavery. The performance was at the FDR Presidential Library and Museum.

Our new location has allowed us to host more people onsite, whether school students or researchers.

This is only a small summary of a few highlights. We hope you will continue to share your ideas about how DCHS can best serve you, and our community.

Rick Levitt

What keeps a community safe from fire? In alphabetical order, it’s buildings, equipment, people, water. But what is the most important? I don’t think alpha order is the right way to determine the most crucial element. To ascertain their relative importance, we investigate each of them in this issue of the Dutchess County Historical Society Yearbook. Maybe readers should take the time to read this entire book before making up their minds. Or maybe they only need to read down a few paragraphs to make a determination.

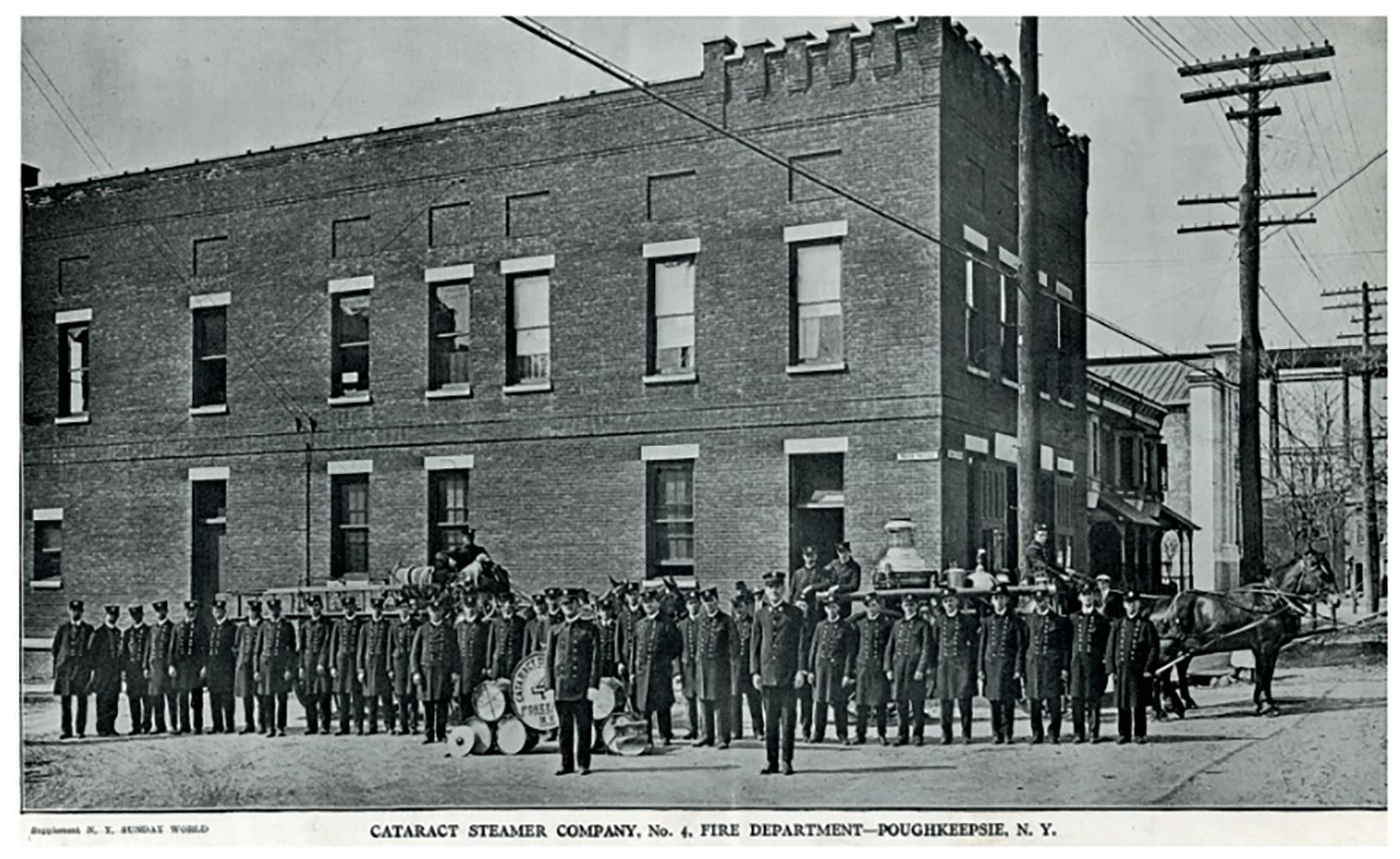

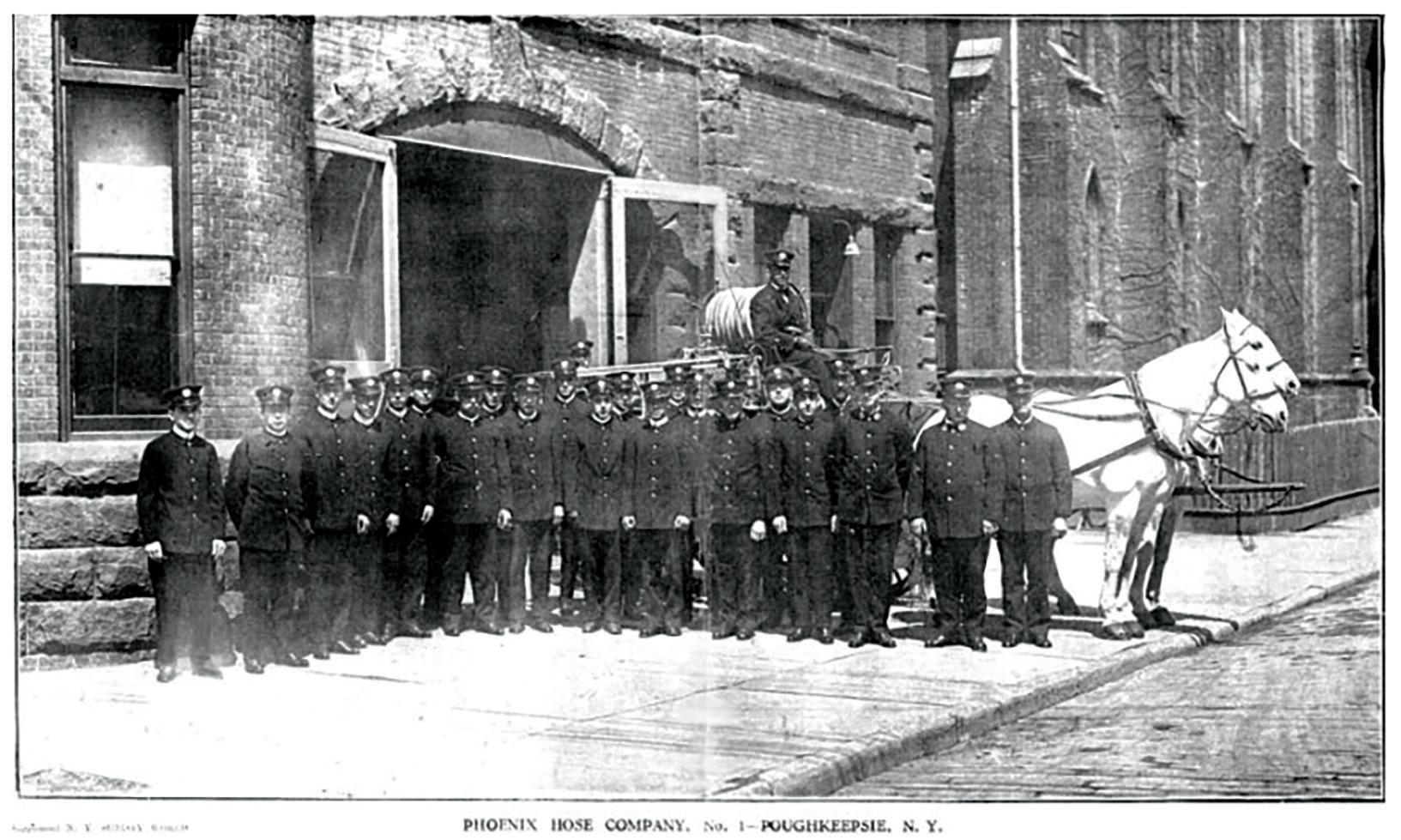

Roy Budnik, a long-time DCHS contributor, touches on all these elements in what could almost be called a street-by-street exploration of the origins of the City of Poughkeepsie Fire Department, including some vintage photos of early firehouses. Look hard enough, and some of these buildings might still seem a little familiar.

Bustling Poughkeepsie on the western edge of the county and more rural Amenia in the east present distinct needs and challenges to all elements of firefighting, so it’s interesting to see where the similarities and differences lie. Andy Murphy tells us about the intimate ties between the agricultural community’s people and its firefighters—and with a collective family history of well over 150 years of dedication to Amenia’s fire department, he ought to know.

Upcounty, Emily Majer walks us floor-by-floor and almost window-by-window through Tivoli’s first firehouse. Next door, you can see the modern, purpose-built structure we associate with the firehouses of today, but this graceful and elegant predecessor is just as important to the community’s health and wellbeing now as it was when first constructed in the late 19th century.

Grace and elegance are nice, but aesthetics aren’t the only consideration in firehouse construction. Bob Wills shows us how the evolution of firefighting equipment drives change in the way firehouses are built. Call this obvious—it’s still fascinating, and Bob, architect and fire district commissioner, is just the person to take us behind the scenes at some of the more recent firehouse developments in the county.

You’ve got equipment and you’ve got a place to store it, but if you ain’t got water, it won’t do you much good. DCHS Executive Director Bill Jeffway plumbs (you should pardon the expression) how Poughkeepsie tried and tried and tried to get right acquisition, storage, and delivery of this critical firefighting element.

But maybe at the end of the day it’s all about the people of Dutchess County—and everywhere else—who give of themselves to keep our communities safe.

Aidan Chisamore spent much of his time at Vassar College studying medieval history, but he has shown himself adept at more modern considerations as well—his exploration of the racial politics surrounding the establishment of Young America, one of Poughkeepsie’s storied volunteer fire companies, is guaranteed to surprise you. He is now Collections and Archives Manager at DCHS

Pride in ourselves and our communities is basic to all of us—and the many ways such pride is demonstrated tell us much about ourselves. I’ve said it before—Melodye Moore has forgotten more Dutchess County history than most of us will ever learn, something she proves yet again with her article on the uniquely American spectacles known as firemen’s parades and musters.

We end our Forum section with the words of one of the county’s long-serving and well-respected volunteers, the late Bill Parsons, who spent 50 years with the New Hackensack Fire Company. This reprint from the 1999 edition of the fire company’s newsletter, like Captain Andy’s detailing of life in the Amenia company, tells us more than any third-hand account about what these folks do for us. We can begin

to best honor them if we understand what their service means and requires.

Vassar College emerita professor Miriam Cohen opens the general section of the yearbook with a rich recounting of Vassar Temple’s 180-year history. She points out that such history is not a laurel-resting phenomenon but an important basis of the service to the broader community that it continues to provide.

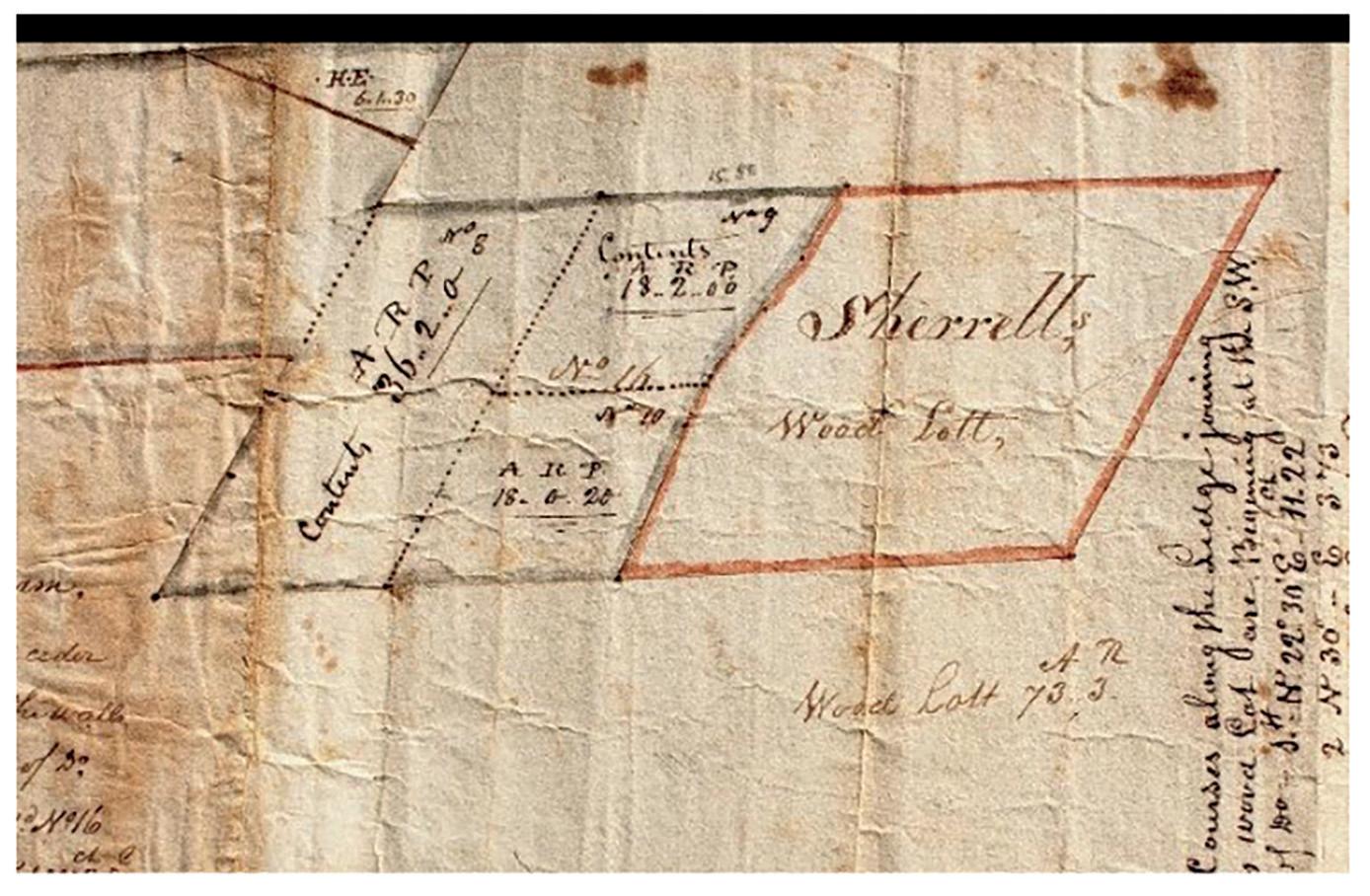

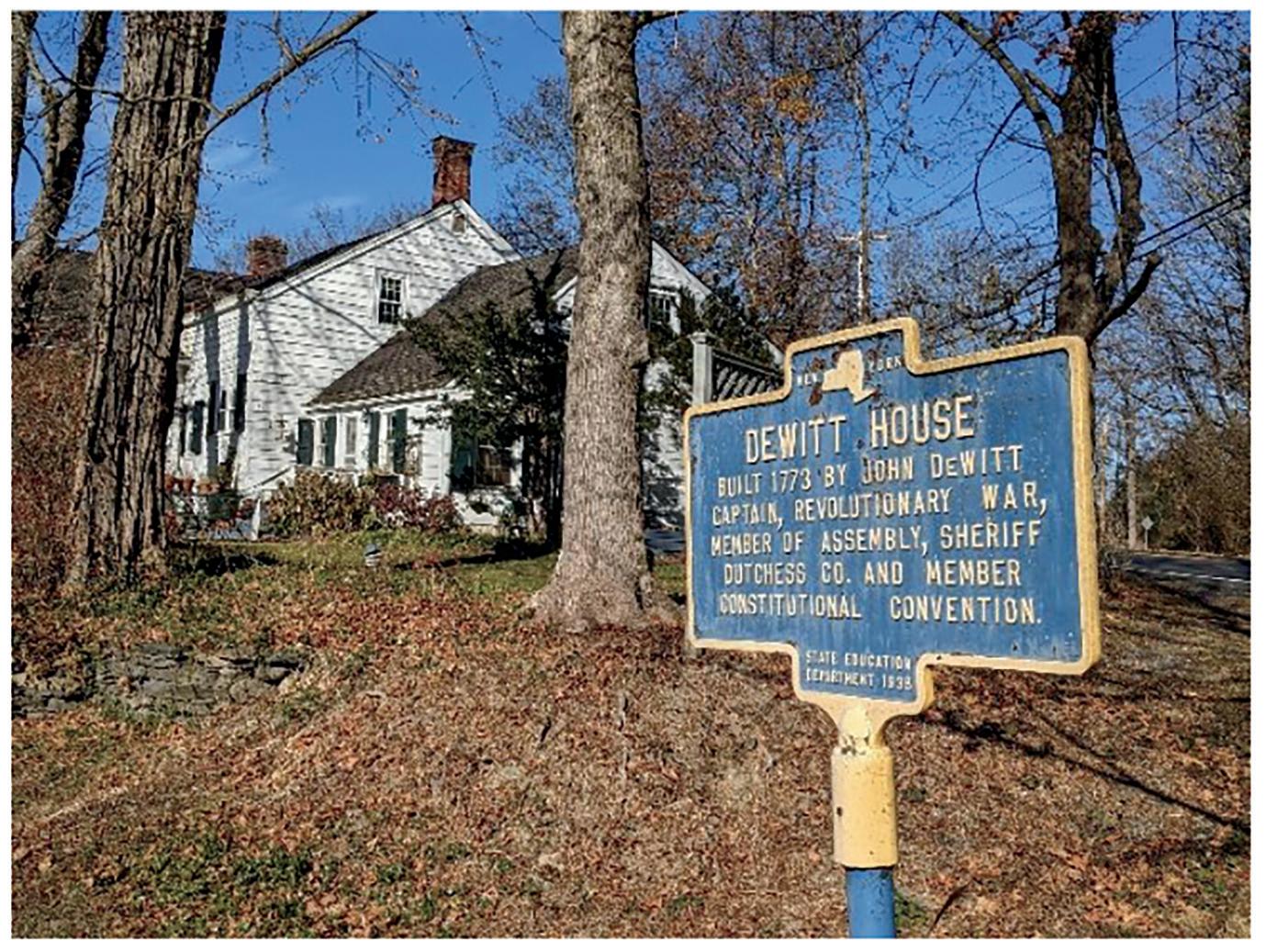

Ever been to Hawktown? You probably have and never even knew it. New York was a slave state? You probably didn’t know that either. Through his exploration of the mostly forgotten, (mostly) free Black community near Staatsburg, local history professional Zachary Veith reminds us of Dutchess County’s checkered legacy.

Checkered it might have been, but it is not difficult to see where sometimes the county was in the vanguard of positive social change. Teacher, local historian, and avid preservationist Georgia Heering shows us just how early the court system in Dutchess County showed it would afford the same justice to women and racial minorities other systems at the time more routinely reserved for White males.

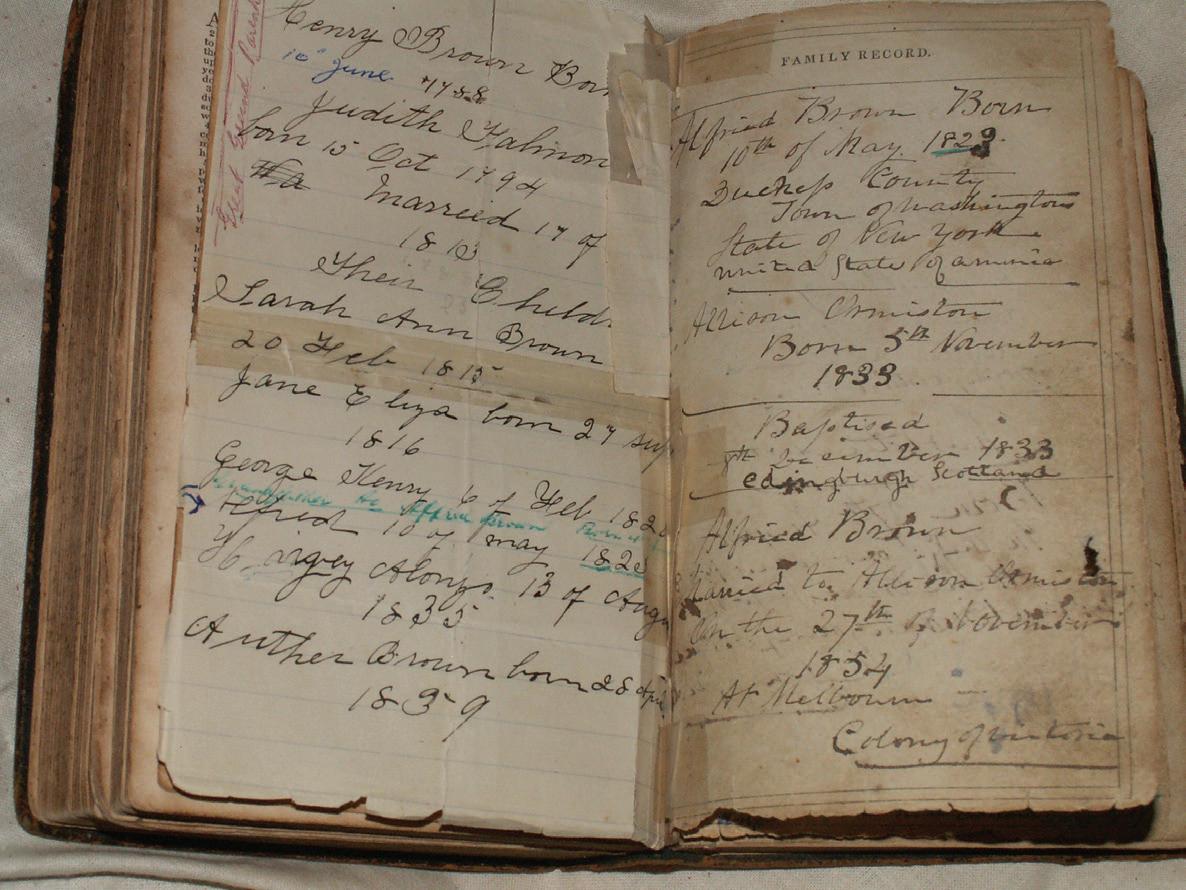

In what has to be one of the furthest-afield contributions to ever grace these pages, Chris Johnston, an Australian descendant of a free Black man who once lived in Dutchess County, shares the details of her pursuit of her family’s history. That history itself is fascinating, but her recounting of the search—including an extended visit here and interactions with local experts—reminds us that the word amateur, as in amateur historian, comes from the French word to love, as in loving what one is doing.

This collection of articles is disparate and eclectic. But the thread that runs through them all is a fascination with and pride in community— passion. All the authors give us further reason to be passionate about this community of which we are a part.

January 1608 – Colonial America’s first fire (Jamestown, Virginia) destroys most of the colonists’ provisions and lodgings

1609 – Henry Hudson sails up the river that is later named for him

1648 – Governor Peter Stuyvesant of New Amsterdam (later New York) appoints four men to act as fire wardens to inspect chimneys and identify citizens who had not kept their chimneys swept clean

January 27, 1678 – The first engine company in colonial America goes into service in Boston; Captain Thomas Atkins is the first firefighting officer in the country

1683 – Dutchess County is created and includes part of today’s Columbia County and all of Putnam County.

1711 – Bostonians form the first Mutual Aid Society and establish the model for volunteer firefighting groups

1714 – The first census for Dutchess County documents 445 residents in the first three settlement areas of Rhinebeck, Poughkeepsie and Fishkill

1717 – An act of the Colonial Assembly directs that Dutchess build a courthouse and prison, thus establishing Poughkeepsie as the county seat

1721 – Richard Newsham, an English inventor, patents an improved fire engine that could be pulled by a cart

1725 – Newsham invents the ten-man pump-action fire engine

1731 – Engine Company No. 1 is founded in New York City after receipt of two “enjines from London”

Back to table of contents

1736 – America’s first volunteer company, the Union Fire Company, is formed in Philadelphia by Benjamin Franklin and becomes the model for volunteer fire companies

1736 –“The Friendly Society For The Mutual Insuring of Houses Against Fire,” the first fire insurance company in America, is established in Charleston, South Carolina

1737 – The New York Colony General Assembly creates the 30-man Volunteer Fire Department of New York, the predecessor of the NYFD

1743 – New York City purchases the first American-designed fire engine, built by Thomas Lote of Maiden Lane and called “Old Brass Backs” (crude and horse-drawn)

1752 – Benjamin Franklin establishes the first homeowners’ insurance company that issued “fire marks” to identify insured buildings

1777 – Poughkeepsie becomes the capital of New York State when Kingston is burned by the British

1788 – The nine original towns of Dutchess County are formed: Fishkill, North East, Pawling, Rhinebeck, Poughkeepsie, Amenia, Beekman, Clinton and Washington

1788 – The state ratification convention for the U.S. Constitution is held in Poughkeepsie

1792 – Hadley, Simpkin and Lott Co. improve upon the hand-pumped fire engine by making it larger and able to be drawn by fire horses

1801 – First post-type fire hydrant is designed in Philadelphia

1802 – The Dutchess Turnpike (Route 44) is chartered and soon followed by other roads, providing greater access to inland Dutchess County

1803 – Members of the Philadelphia Hose No. 1 man the nation’s first hose-wagon fire engine and create a new form of leather hose using rivets instead of stitches

1800 – The Sack and Bucket is organized as the first recorded Poughkeepsie fire company. Eventually Poughkeepsie had seven

companies: Niagara Steamer, Davy Crockett Hook & Ladder, Cataract Engine, Phoenix Hose, Lady Washington Hose, O. H. Booth Hose, and Young America Hose

1806 – Dutchess County’s first courthouse is destroyed by fire

1807 – Town of Dover created

1812 – Town of Red Hook created

1818 – Town of Milan created

1821 – Towns of Hyde Park and Pleasant Valley created

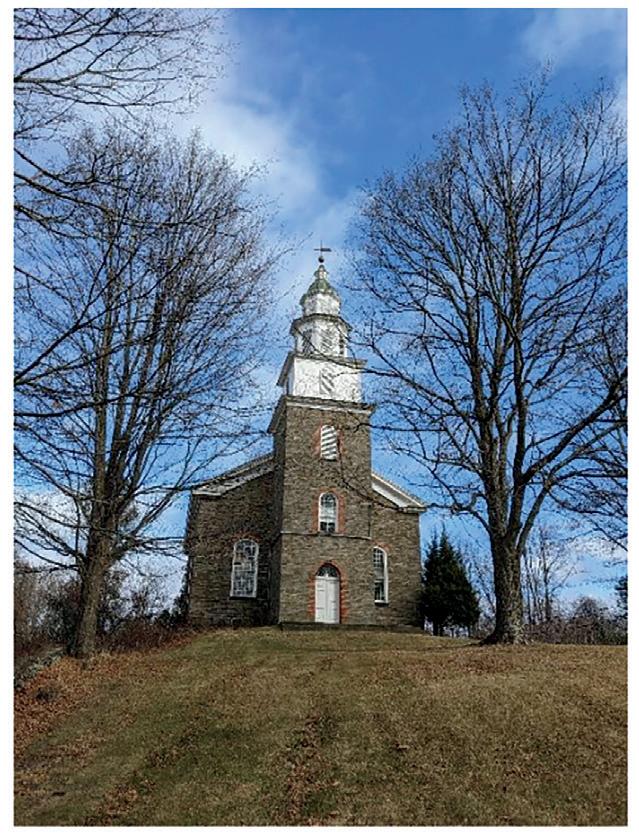

1821 – The “Rhinebeck Flatts Fire Company” is incorporated by the State of New York

1823 – Town of Pine Plains created

1827 – Town of Union Vale created

1828 – Town of Lagrange created

1829 – Fishkill Fire Company is incorporated

1829 – The first horse-drawn team-powered fire engine is built in New York

1832 – Charter is issued to Dutchess County Railroad to construct a line from Poughkeepsie to the Connecticut state line

1834 – Rhinebeck Fire Department is organized and ultimately includes the H.S. Kipp Hose and the Relief Hook and Ladder Companies

1837 – Franklindale Fire Engine Company is founded in Wappingers Falls

1841 – The first self-propelled steam fire engine is built in New York City

1849 – Town of East Fishkill is created

1850 – Wappingers Falls Fire Company is founded

1852 – Samuel F.B. Morse’s invention of the telegraph leads to the

design of a system of fire alarm boxes in Boston that transmit their location to a central office

1853 – Cincinnati, Ohio creates the first professional fire department with all full-time employees

1865 – New York’s volunteer fire department is disbanded in favor of the paid, full-time Metropolitan Fire Department; other large cities soon follow their lead

1868 – San Francisco firefighter Daniel Hayes invents and patents the first successful aerial ladder

1869 – William T. Garner Engine Company #1 is founded as the successor to the Franklindale Fire Engine Company

1872 – S.W. Johnson Engine Co. #2 organized in Wappingers Falls

1875 – Town of Wappinger is created

1885 – Patent granted for Schuyler Wheeler’s electric fire engine system

1886 – Beacon Engine Company #1 and Lewis Tompkins Hose Companies are formed; Mase Hook and Ladder is organized a year later

1888 – Poughkeepsie Railroad Bridge is completed

Late 1800s – Full-time firefighters with standardized equipment become the norm for firefighters in metropolitan areas; standardized equipment with volunteer firefighters become the norm in more rural communities

1892 – E.H. Thompson Hose Company is organized in Millerton; the bell of the old Presbyterian Church is adopted as the official fire alarm

1894 – The Staatsburg Fire District is organized as a bucket brigade

1895 – The Village of Pawling sanctions a fire department with 39 charter members

Amenia Hose Company #1 is organized Pine Plains Hose Company is organized

1897 – Liberty Hose Company #1 and Union Hook and Ladder Company #1 are formed in Pawling

1903 – John Knott Volunteer Fire Company is formed in Pleasant Valley

J.H. Ketcham Hose Company is founded in Dover Plains

1905 – The first self-propelled internal combustion fire engine is manufactured by Knox Automobile in Springfield, Mass.

1908 – Millbrook Fire Company #1 is formed

1909 – The Dinsmore Hose Company is organized and three years later begins construction of its Fire Station #1

1910 – Fairview Fire Company is established

1912 – Hopewell Hose Company is formed

1913 – John Knott Volunteer Fire Company (est. 1903) becomes the Pleasant Valley Fire Company

1913 – Hughsonville Fire Company is founded

1915 – Rhinecliff Volunteer Fire Company is incorporated

1917 – New Hamburg Fire Department is formed

1919 – Red Hook Fire Company formed from the consolidation of Griffing and Chanler Companies

The three Tivoli fire companies (F. S. Ornsbee Engine Company, Johnston L. DePeyster Hose Company, and J. Watts De Peyster Hook and Ladder) are united to form the Tivoli Fire Company

Early 1920s – Arlington Fire District begins in the roots of a volunteer company called Arlington Engine #1, out of the American Protection Chemical Company

1921 – Stanford Fire Company is founded Glenham Fire Company established and named the Slater Chemical Fire Company

1925 – By this time gasoline-powered fire engines have replaced almost all steam-powered engines

1929 – Fairview Fire District is created and hires Sal Lozier as its first paid firefighter

1931 – Clinton Corners Fire Protection Association formed and purchases its first one-ton Model T Ford fire truck from the Arlington Fire Department

Hillside Fire Department is formed

Wassaic Fire Company, known as the “Blue Crew,” is organized

1935 – East Fishkill Fire Department is formed

1937 – Beekman Fire Protectives is organized

1941 – First meeting of the Lagrange Fire Department; 76 men apply for membership

1945 – First meeting of the West Clinton Fire Department

1946 – Chelsea Fire Company is established

1947 – Salt Point Fire Station established in the former P&E Railroad Station

Milan Volunteer Fire Department Fire Protection District is formed

1949 – Stormville Fire Company is formed

New Hackensack Fire District and Fire Company founded

1952 – Union Vale and Hillside Lake Fire Companies formed

1954 – Wiccopee Fire Company formed; Roosevelt Fire Department formed

1962 – First fire phones were installed in firefighter homes in the Verbank area

Early 1960s – Water pumps, ladders and cherry pickers emerge as commonplace tools for firefighters

1971 – Rombout Fire District is formed

1972 – Dutchess Junction Fire District is established

1973 – Landmark report by the National Commission on Fire

Prevention and Control, America Burning, makes various recommendations to better control and prevent fires

1976 – The National Volunteer Fire Council, a nonprofit organization, is founded to give a unified voice for volunteer firefighters around the country

1981 – The Millerton Fire Department accepts its first volunteer woman firefighter

1984 – Nancy Brownell is appointed by the Rhinebeck Village Board as its first female member

2018 – Staatsburg Fire District merged with the Roosevelt Fire District to form the “New” Roosevelt Fire District, serving the majority of the Town of Hyde Park

2024 – The fire departments of today are a mix of full-time, paid-oncall and volunteer responders

Selected information taken from “The History of Firefighting: A Visual Timeline” – La Ribera Fire Department

Melodye Moore

One of the most important organizations in any community is the local fire department. Volunteer or paid, they are respected for their dedication and commitment to the health, safety and well-being of their neighbors. They serve with dignity and justifiable pride in the work they do. Filled with a spirit of camaraderie, fire companies are fraternal organizations who rely on one another in times of danger and distress. Nonetheless the competitiveness that propels them into action has always been a tangible part of firefighting culture.

Perhaps the greatest display of a firefighter’s pride and pageantry is shown in parades. Whether it is Memorial Day, the 4th of July, or any other local celebration, it can be guaranteed that one of the highlights of the parade will be the companies of firemen, marching proudly in precision formation, followed closely by all types of fire trucks. It is an iconic American image.

One of the earliest and likely most observed parades that included firemen took place in September of 1824 in New York City. The Lafayette Welcoming Parade was organized to celebrate the arrival of the last surviving Major General of the Revolutionary War as he began a sixteen-month tour of America. Histories record that forty-six engines, several hook and ladder companies and two pumpers passed in review in City Hall Park before 30,000 spectators. Similar parades took place to celebrate the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, the French

Back to table of contents

Revolution in 1830 and the visit of the Prince of Wales in 1860 where it was reported that over 6,000 volunteer firemen marched.1

A parade offered then, and still today, a festive opportunity for fire companies to remind their neighbors of the important role and place of honor they hold in their communities. To make the point, days were spent preparing uniforms and decorating special parade wagons with floral wreaths and bunting. Each fire company would compete to have the most impressive banner, decorative pumper plaques and uniforms.

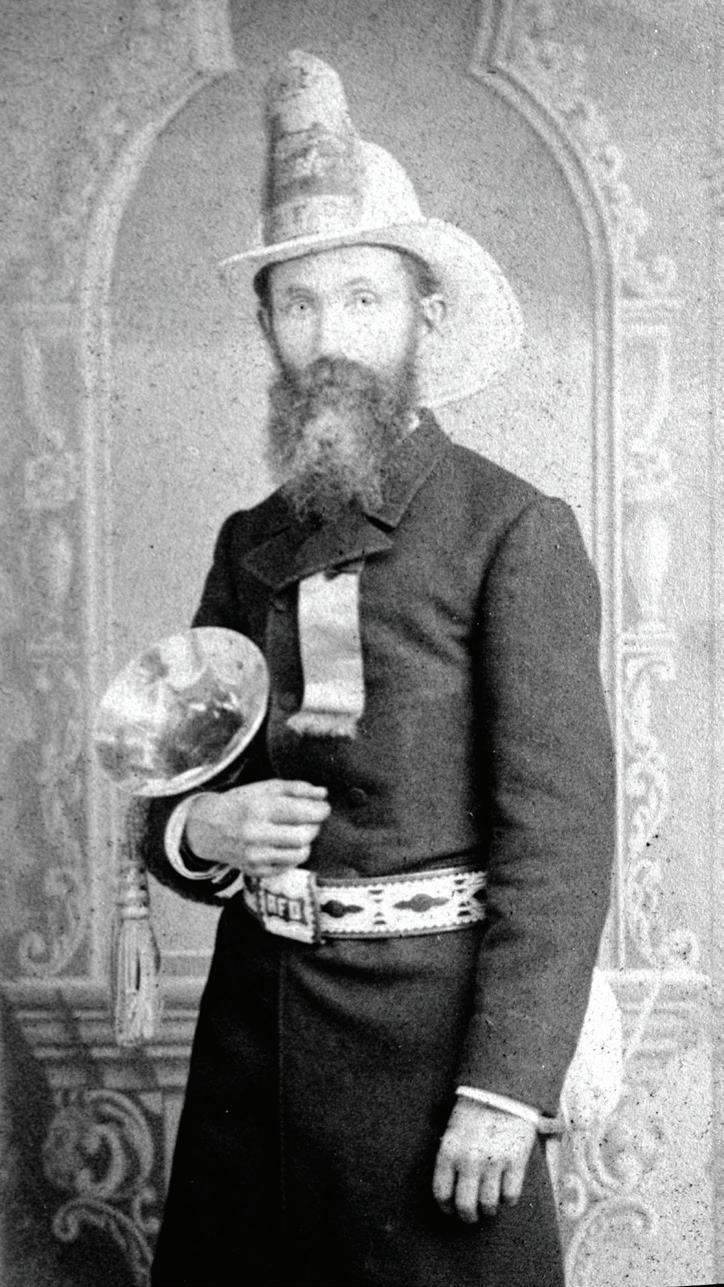

Unlike the protective turnout gear worn by firefighters responding to fires, the uniforms provided by fire departments for civic occasions, ceremonies and parades were often adorned with identifying logos that represented their individual fire companies. The typical parade uniform included bib shirts (often red), parade hats or fire helmets and decorative leather belts During the late 18th century the “stove-pipe” fire hat appeared. Made of pressed felt they were painted with the fire company’s name and often had the owner’s initials painted on the top of the hat. Originally worn at fires to help identify firefighters, they eventually were replaced by the Gratacap-style fire helmet still used today, and the stove-pipe hat was retired to become parade hat status. As the nineteenth century progressed the preferred parade hat was a visored wool cap that was the forerunner of the dress cap of today.

Ceremonial parade belts were popular from the 1850s to the early 1900s. Traditionally made of leather, they were embellished with leather cutout letters denoting the name of the fire company or the rank of the firefighter. Often they included decorative designs and zigzag leather trim. Also prominent in the parade formation was the ceremonial fire trumpet. Historically firefighters used trumpets as megaphones to amplify their voices when shouting instructions during a fire. The ability to hear clear directions was essential for the safety of firefighters and the coordination of their actions. Over time, trumpets took on symbolic meaning for fire departments and special ornately

1 Paul C. Detzel, Fire Engines, Fire Fighters (New York, New York,: Rutledge Books, 1976) p. 74

engraved silver presentation trumpets became a featured component of any parade.

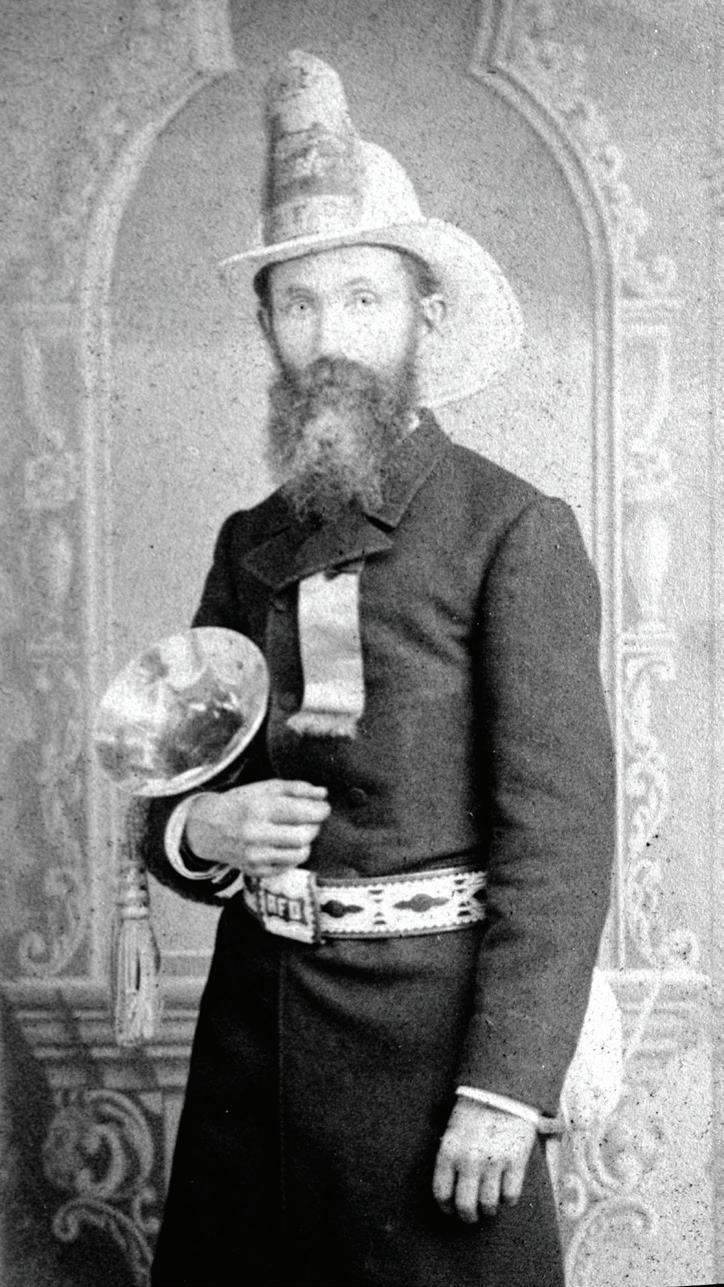

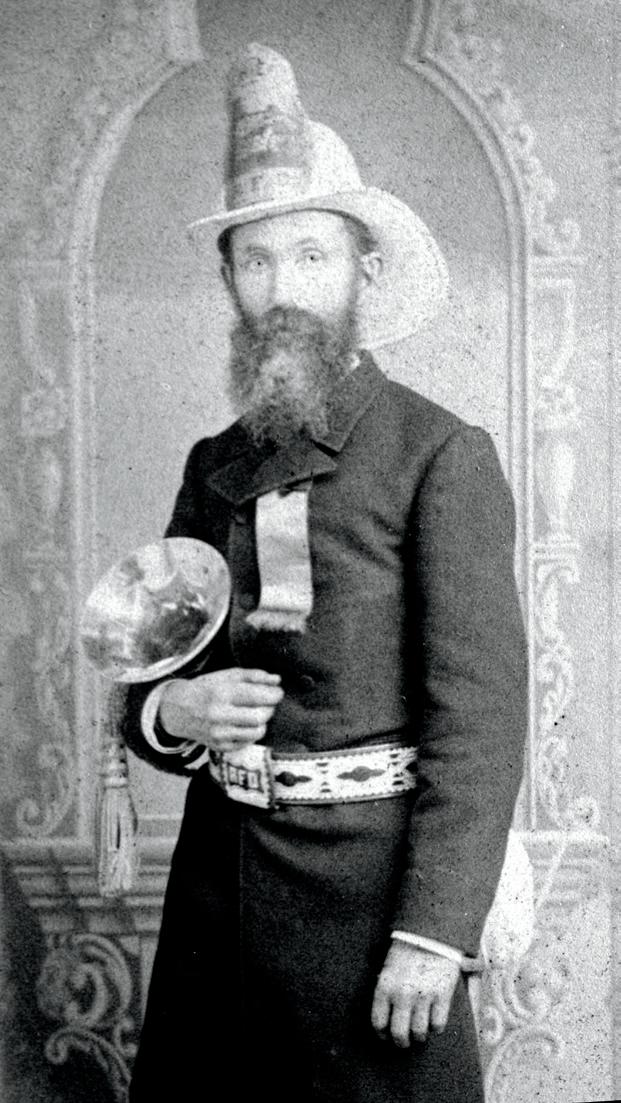

: A white hat indicates a fire chief. The trumpet evolved from a functional to more ceremonial role over time. Also shown, parade or ceremonial belts. Courtesy of the Rhinebeck Fire Department. Right: Harrison N. Secor (1836-1918) was Captain of Relief Hook & Ladder Company. Professionally he was a stone cutter and responsible for many monuments in the Rhinebeck Cemetery, including the Civil War memorial. Show in ceremonial role. DCHS Collections.

Topping off the entire extravaganza was the fire apparatus and fire companies who could afford it commissioned the manufacturing of elaborate carriages to carry their fire hoses in parades and other ceremonial events. Many Dutchess County fire companies had a parade carriage. One of the most notable in the county was that of the Henry S. Kip Hose Company No. 1 of Rhinebeck. Delivered in September, 1893 it was an exquisitely intricate example of a parade wagon and won its first victory at an event for the Hudson Valley Volunteer Fireman’s Association of Kingston in 1901. It is believed to have been

used into the late 1950s for competitions and parades when it was sold to a private individual who intended to restore it. Several transactions later it was purchased by the Koorsen Fire Museum of Indianapolis, Indiana where it resides today.

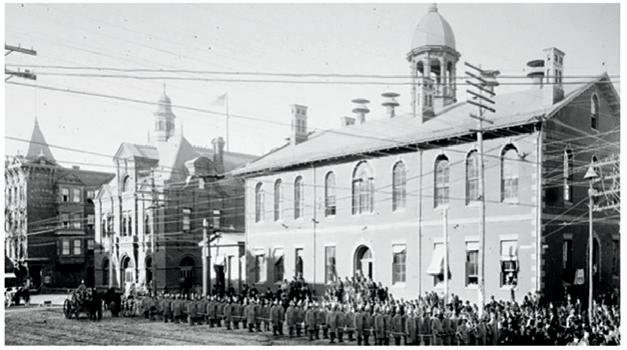

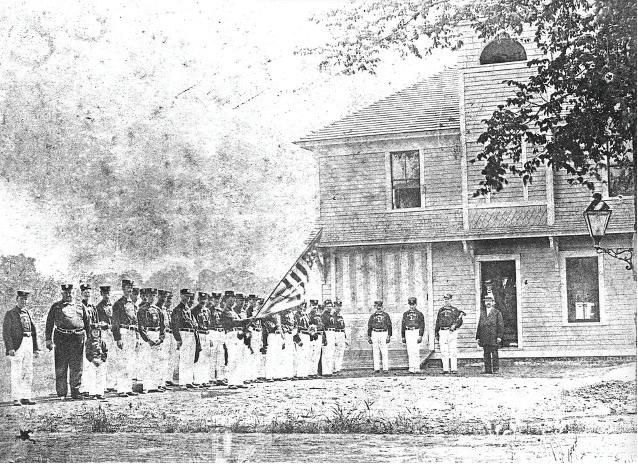

The volunteer Firemen’s Association of the City of New York. Poughkeepsie, August 17 – 20, 1909. Courtesy of the Firefighting Museum of Dutchess County.

Another notable Dutchess County parade carriage was that of the Lewis Tompkins Hose Fire Company of Fishkill-on-Hudson. Made by the Gleason and Bailey Company of Seneca Falls, New York, it was purchased in 1888 when local hat manufacturer Lewis H. Tompkins donated $1,000 to acquire a parade wagon for the firehouse named after him. Hand-drawn, the carriage was made of nickel and brass. By the 1930s the carriage was considered old-fashioned, local residents lost interest in it and it was shuffled around town. In the January 2004 newsletter of the Beacon Historical Society, local historian Robert J. Murphy recounts its travels after being purchased in the early 1940s by an antique dealer until it ended up in “The Hall of Flame,” a firematic museum in Phoenix, Arizona.

It was not inexpensive to prepare a fire company for a parade and required a lot of planning and coordination. These minutes from the Protection Engine Company No. 1 Inc. of Fishkill tell the story.

“Sept. 21, 1904 – A special meeting was held to secure unfinished business on the invitation to parade received from Beacon Engine Co., to parade in Matteawan and supper. Invitation was brought up at the May 1904 meeting. Some advance was made by the committee as to the band. A band from Cold Spring was to be hired for $55.00 A committee of one was appointed, R.E. Dean, to get the engine and apparatus in presentable shape for the parade.

October 1904 – Uniforms for the parade were purchased from Beacon Engine Company. 53 uniforms and 41 caps were purchased. The Company paid $300.00 for same, although Beacon Engine Co. wanted more. Beacon Engine Co. had purchased new uniforms.

Oct. 10, 1904 – meeting reported that the band from Cold Spring would cost $40.00. Committee to wait on the Village Board reports receiving permission to take the Engine to the parade. Committee to solicit funds for parade purposes reports that $7.50 had been subscribed. It was resolved that a team of horses be used to haul the Engine during the parade, provided the consent of the Village Board could be gotten. Members attending the parade were to wear black pants, black shoes, well polished, stand up collar with slightly rolled ends and black tie. The company will provide white gloves. A committee was appointed to present the wishes of the Company to the Village Board in regards to the repairs of the Engine.”2

The forty-six members of PECO who participated in the parade were transported to Matteawan through the generosity of Mr. Smith, President of the local trolley company who offered free transportation. Once there the firemen pulled the hose-cart by a rope and their hand pumper was drawn by horses. Post parade reports announced that the fire company was cheered all along the line of march.3

Fire companies seemed to like nothing better than finding a reason to have a parade, and as transportation by trolley, train and steamboat became easier “visitations” became popular. Sometimes it was a simple invitation from one company to another such as the September 28, 1880 visit from the Cataract Hose Company of Paterson, New Jersey to Rhinebeck. Described in the Poughkeepsie Eagle-News as “Rhinebeck’s Gala Day,” the morning procession was followed by

2 History Committee of Protection Engine Company No. 1, Inc., Fishkill Fire Department, 1829 – 1979, A 150 Year History (Beacon, N.Y.: Dutchess Publishing Co., Inc., 1979) p. 11 - 12

3 Ibid. p. 45 - 46

an inspection in the afternoon. Members of the Cataract Company, let by the sixteen-piece Paterson Band, were met at the Rhinecliff wharf at 9:30 a.m. by Steamer Co. No 1 of Rhinebeck which was led by the Rhinebeck Cornet Band. The parade kicked off at 10:45 a.m. and wound its way three miles through the Village from West Market Street to South Street, thence to East Market Street, thence to Mulberry and eventually back to the home of Ambrose Wager on West Market Street near the Fireman’s Hall where it was dismissed. Houses throughout the Village were decorated with flags and bunting. The grand line of march included the Chief Engineers of both companies, Rhinebeck Village Trustees, and the Paterson, Rhinebeck and Rondout fire companies, each accompanied by their own bands. The parade was followed by dinner at Tremper’s Hotel. Shortly after dinner what was known as an inspection took place when the Rhinebeck Steamer was hauled up to one of the cisterns and fire was started in her. In eleven minutes she had steam and threw water about 200 feet. The test ended when the hose burst twice and some of the machinery gave out. Rhinebeck’s hand engine Pocahontas was tested next but as she was not as well manned and couldn’t match the distance of the steamer. The day ended with the Rhinebeck Band playing on the piazza of the hotel and the Paterson firemen being escorted to the river.4

Just a few days earlier on September 24th the Phoenix Hose Company No. 1 of Poughkeepsie traveled to Newburgh to take part in the City’s annual Fireman’s Parade. Accompanied by the Tenth Regiment Band of Albany the thirty firemen, along with their guests, marched to the waterfront to board a steamer that was to take them to Newburgh. Upon their arrival they were escorted to the Lawson Hose Company where they housed their carriage until the start of the parade. Following dinner at the United States Hotel the companies formed and the parade began. The Poughkeepsie Eagle-News reported that the Phoenix firemen, dressed in handsome white coats, were accorded the honor of being the “finest looking organization in the procession.”5 Their return to Poughkeepsie was met at the dock by the entire Fire Department of the City and a torchlight parade led them to the No. 6 house where

4 “Rhinebeck’s Gala Day,” Poughkeepsie Eagle-News, September 30, 1880, p. 3

5 “Firemen’s Excursion,” Poughkeepsie Eagle-News, September 25, 1880, p. 3

another meal was served. One wonders how the firemen of Dutchess County found time to fight fires.

Poughkeepsie Thronged With Them

A Gala Day For The City

So read the October 6, 1880 headline that kicked off a multi-column Poughkeepsie News Press article reporting on the gathering and parade that placed special emphasis on the New York Veteran’s Firemen’s Association. The newspaper writer stated that “a parade and review of firemen is a rare occurrence in this city, and its features are unfamiliar to the people here.” Trains brought spectators to the City (Poughkeepsie) and all available sheds and stables were filled with the teams that would later pull the various fire apparatus. Extravagant decorations adorned neighborhoods. The four-division parade stepped off at 11:30 a.m. Led by a platoon of police, the 10th Regiment Band and visiting chiefs, the Phoenix Hose Co. No 1 of Poughkeepsie was the first fire company in the parade. There were about thirty men in line, all wearing a black regulation fire hat, red shirt, dark blue coat and black trousers. In addition to the Phoenix Hose Co., the Davy Crockett, Niagara, Booth, Lady Washington, Cataract and Young America fire companies were all represented and in total over two hundred Poughkeepsie firemen participated in the parade. Their dress uniforms were all similar but the Davy Crockett volunteers distinguished themselves by wearing red hats and white shirts. The line of march was distinguished by carriages carrying 230 members of the veteran fireman’s association and eleven bands, including those from West Point and Eastman College, led the marchers. It was speculated that over 30,000 spectators lined the parade route. One of the final notes in the story commented that “No accidents were reported, and very little drunkenness was seen.”6

Perhaps the best known firemen’s parade to take place in the county

6 “The Firemen,” Poughkeepsie News Press, October 6, 1886, p. 8

occurred on August 20, 1909 at the conclusion of the 37th Annual Convention of the New York State Volunteer Firemen’s Association. The idea to have a volunteer firemen’s convention was formed following an August 1872 parade in Auburn, New York. Shortly thereafter a committee was formed, a report was prepared and the first convention took place in Auburn on October 1st and 2nd of that same year. While that hastily organized first convention was not heavily attended, the organization grew and by 1909 was an important source of education, training and support for the firefighting community of New York. Local newspapers started reporting on the plans for a convention in Poughkeepsie in the spring of 1909. At a meeting of the General Committee on April 9th it was reported that Veteran’s Firemen’s Association would attend and bring 125 uniformed men and a band of 25 or 30 pieces. The Chairman of the Entertainment Committee reported that the Burger Amusement Company had visited the City to discuss the prospect of holding a street fair during the convention. He was assured that a favorable site had been identified and the proposition would likely be approved. Further discussion took place about speakers and fundraising but the main order of business was to select the design for the official delegate badge. After closely examining a dozen different designs submitted by local businessmen the committee selected the design submitted by J.E. West & Company of Poughkeepsie. The design was in the form of a Maltese Cross suspended from a red ribbon. Within the cross was a central circular die containing a representation of the Poughkeepsie bridge and a pendant hanging over the ribbon depicted the beehive, the seal of the city.7

Days in advance of the Convention the Poughkeepsie Eagle-News was reporting on the decorations that were being installed throughout the city. It was the opinion of the newspaper reporter that the display of J. Schrauth & Sons, ice cream manufacturers, stood out as the most elaborate. “Besides the familiar festoons of American and other flags there are streamers extending from the roof down to the

7 “Firemen Select Official Badge,” Poughkeepsie Eagle-News,” April 10, 1909, p. 5

first floor and electric lights with their bulbs of various colors. The bunting is entwined above the light wires and the effect derived is most pleasing.”8

The five-day convention closed with what the newspaper described as a “Monster Parade.” On the day of the parade the streets were thronged with crowds of people who had come by automobile, ferry and train, and the hotels, restaurants, boarding houses and lunch rooms were full to capacity. Nearby communities like Fishkill Landing, Matteawan and most of Newburgh closed their businesses so that their residents could travel to Poughkeepsie to be part of the festivities. In anticipation of the crowds the Poughkeepsie Police Department had made the decision that all members of the department had to be on duty and all scheduled vacations were cancelled. Fire companies began arriving in the morning with each visiting company being the guest of a Poughkeepsie company. Among the out-of- town companies were the Kip and W. M. Sayre Companies of Rhinebeck, the Lewis Tompkins Hose Co. of Fishkill Landing, the Rescue Company of Hyde Park, and the Brewster Hooks of Newburgh. The judges awarded the $75 prize for the finest appearing company to Lewis Tompkins, while the Citizen’s Hose Company of Catskill was considered a close second. According to the newspaper reporter covering the parade:

“But shining above it all in point of uniform, that is for being the brightest spot in the parade, with those conspicuous outfits of sizzling red was the department from Hyde Park, the Eagle Engine Company by name. There was some noise to them and to cap it all off they wore patent leather shoes. They made quite a fine showing.”9

The day was brought to a close when a deluge broke up the parade just before the end of the line was reached. Touted as “not only the largest but the finest (parade) ever held in the Hudson Valley,” nearly

8 “The Decorations On Main Street,” Poughkeepsie Eagle-News, August 17, 1909, p. 5

9“Firemen’s Convention Closed With A Monster Parade Friday,” Poughkeepsie Eagle-News, August 21, 1909, p. 1

seventy-five companies had marched in line and over four thousand men had participated in what must have been a spectacular display of firefighting pride and pageantry.10

Firefighting companies were one of the first public services to be organized in America. Healthy rivalries between companies emerged and competition among firefighters and fire companies was evident from the very beginning. Speed of response was critical and in the early days of firefighting cities and insurance companies provided cash bonuses to the companies that were first to arrive at the scene of a fire. First-water bonuses were also paid and volunteer firemen raced each other to make the first claim on hydrants and water sources.11

It was not surprising that this spirit of competition among firefighters and fire companies became, as we have seen, an important element of any parade. Who had the most men marching? Who had the best uniforms? Who had the best and mostly beautifully decorated engines, pumpers and parade wagons? Therefore it was not surprising that proud and competitive firemen devised another way to vie for supremacy - the muster.

The term muster is said to date to the 1400s when it was used as a military term to refer to a gathering of troops. It is also said to derive from the old French word “mostrer” meaning appear, reveal or show. Most sources state that he first recorded muster in America took place in Bath, Maine in 1849 when five hand pumpers competed to see who could pump water the farthest. A scrapbook of newspaper articles about the Rhinebeck Fire Department contains an article that claims that the first measurement of the length of water streams of pumpers occurred in Amesbury, Massachusetts on July 4, 1844 and that a purse of $1,000 in prize money was distributed to the winners.12 What fire historians do

10 Ibid. p. 1

11 Detzel, p. 62

12 Rhinebeck Fire Department Scrapbook 1974 – 1977, compiled by Rhinebeck Fire

agree on is that the Firemen’s Muster, a firematic competition between fire companies, is the oldest organized sport in America.

The goal of a muster is simple – whose pumper, also known as a hand tub, can throw the longest stream of water. While the goal may be simple, the actual competition was not and involved all sorts of rules that were administered and overseen by timekeepers and engine platform, pipe platform and paper platform muster judges. Apparently in the earliest days of musters rules tended to made up on the field and the result was confusion and discord among the competing fire companies. This was addressed on November 20, 1890 when the Boston Firemen’s Association convened a meeting for the purpose of organizing a New England States Fireman’s Association, the object of which was to “encourage and perpetuate the oldest sport in the Country, assist outside interest in the promotion of musters and serve as an arbiter in settling the questions arising among the several Associations affiliated with the League.”13 The organization flourished and since its founding has been the biggest promoter of the sport. It is still in existence today, known as the New England States Veteran Firemen’s League, and in 2024 organized seven hand engine musters throughout the northeast.

While the objective was to shoot water through a fire hose and to measure the drops of water furthest from the tub, the steps leading up to the actual release of water had to be precise and perfectly executed. The field had to be prepared and a six-foot wide rosin paper target was laid down. The hose nozzle was capped for quick release and each fire crew, in succession, had 15 minutes to: get on the platform, get up the prime, clear 150’ of hose of air, fill the hose with water, maintain pressure, gauge and if necessary wait out the wind, man the pump and await the signal from the foreman to release the cap and the water. The crews were made up of strong, muscular firemen who took their positions on both sides of the tub and raised and lowered the arms that created the pressure needed to send the stream of water to its goal. Standing atop the tub was the foreman whose responsibility it was to direct the actions of his crew. His job was considered the most

Department Ladies Auxiliary, 5

13 New England States Veteran Fireman’s League, handtubs.com/NESVFL, 2023

dangerous as he could easily be harmed if the dome of the tub were to blow off. Muster records reveal that some competitions were won by a mere half inch.

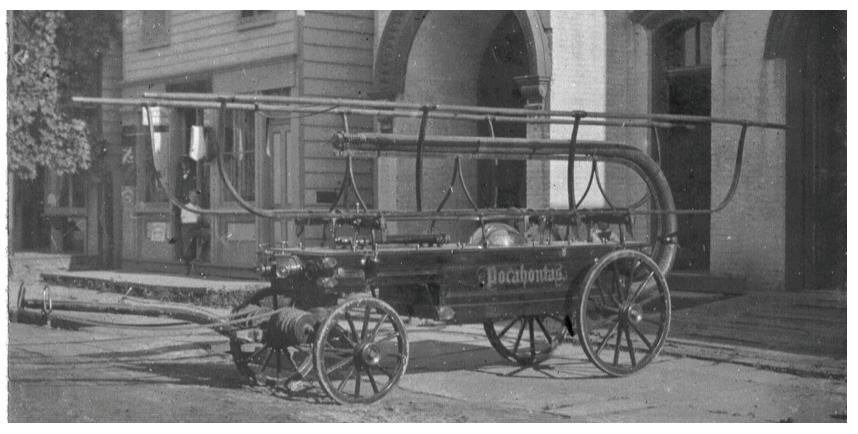

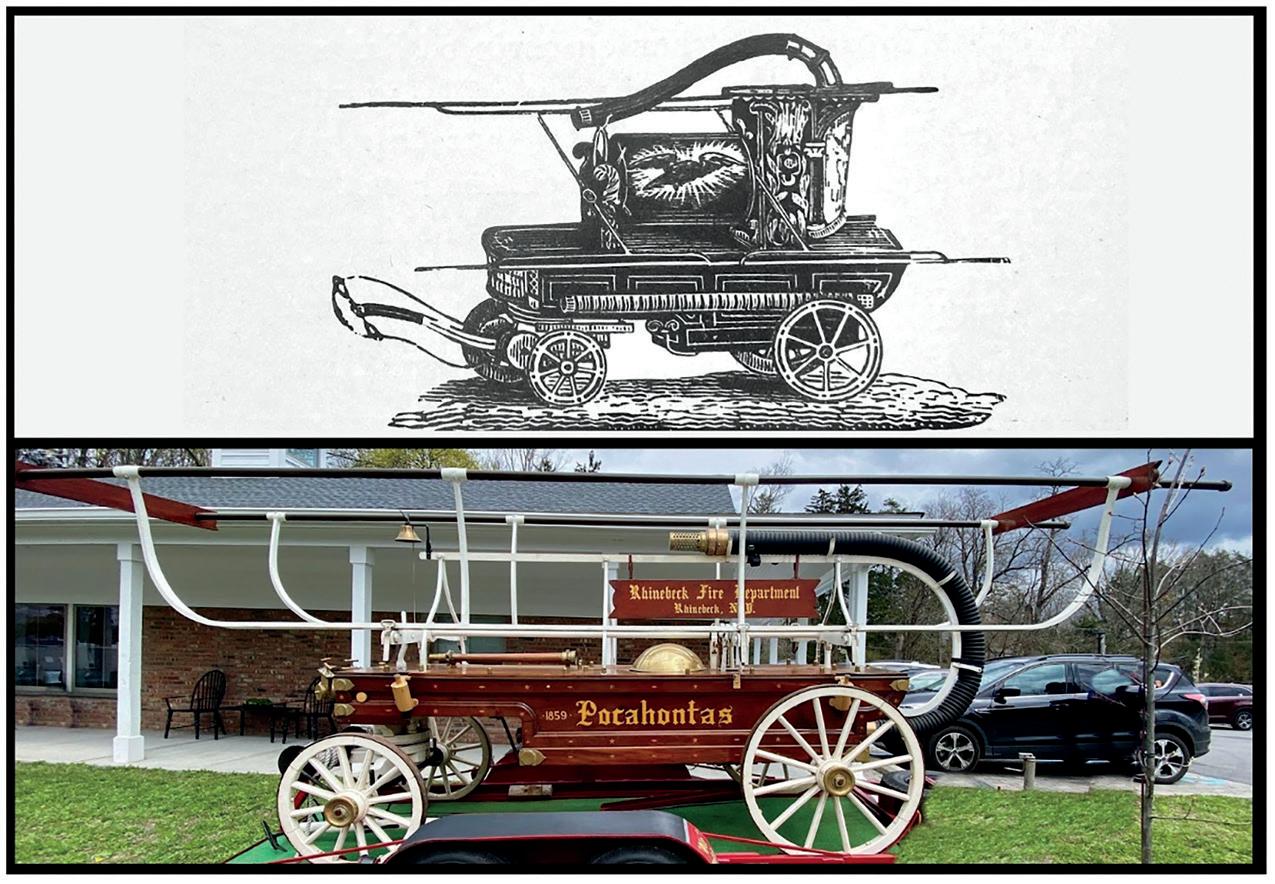

The only Dutchess County fire company to be a member of the Firemen’s League was the Rhinebeck Fire Department and its pride and joy was its handtub Pochahontas. Bought new in 1859 for Pocahontas Engine Co. #2,it was manufactured by the Button Company of Waterford, Connecticut. Constructed of cherry and mahogany, the tub is a piano box style with a single pressure dome and a piston-type pump with 10” diameter pistons. A crew of forty-eight was required to pump the arms. For years “Old Pokie” was integral to the fire response efforts of its fire company, only to be retired as more modern equipment became available and only taken out for the occasional parade. In 1953 “Old Pokie” was taken out of mothballs, restored to working condition and made ready for a pumping competition at the Eastern States Exposition in Springfield, Massachusetts in September of that year. That same year the fire department became an associate member of the Fireman’s League and subsequently was admitted to full membership. “Old Pokie” regularly participated in musters until the late 1980s when it was deemed too fragile to continue to compete. During her career she was recorded as shooting a stream as far as 217’ 8 ¾” , only to be bested by her archrival Neptune, from Newburyport, Massachusetts who shot 243’ 10 ¾”. She is still proudly displayed in local parades and celebrations.

Minutes of the Walter W. Schell Hose Co. of Rhinebeck document that “Old Pokie” had taken part in musters earlier than the 1950s. Meeting minutes from August 21, 1895 record that the fire company had received an invitation from the Pittsfield Fire Company asking them to attend a muster on September 25th. Representatives from the other Rhinebeck Fire Department, the Pochatonas Company, were present at the meeting and indicated that they had also received the invitation and would be happy to join forces and that any award money would be split after defraying any costs associated with the trip.14

14 Walter W. Schell Hose Co., Fire Co. Register 1894 – 1897, p. 166 – 168 (DCHS 2024.003.003.004)

Musters and demonstrations have always been about speed, volume and pressure resulting in highest reach. While physical demands remain profound for fire fighters, in general they are no longer using their hands and feet to pump water. Image DCHS Collections.

The Rhinebeck Fire Department (formed in 1963 with the merger of the J.S. Kip and Pocahontas Fire Departments) hosted its first muster in 1968 and was an active participant in musters throughout New England for the next several decades. The August 17, 1974 muster, which was sponsored by the Rhinebeck Fire Department and hosted by the New Hackensack Fire Department, was well covered in the local press and gives a good picture of the excitement and pride surrounding musters. The Poughkeepsie Journal reported that the day-long hand pumping competition would include fifty companies from six states, and the competition was to be preceded by a parade of antique equipment led by fife and drum bands. A representative of the Rhinebeck Fire Department was quoted as saying “In order to qualify for the competition the piece of equipment must have been built prior to 1890 and water has to go a least 200 feet in order to qualify.”15

Firefighters answer a call. They have a calling. They are local superheroes. Too often we take them for granted and fail to recognize the important role they play in our lives. Parades and demonstrations of prowess with fire apparatus give them the opportunity to remind us of their skill and sacrifices, and we have the opportunity to applaud them and share in the pride and pageantry that is inherent in firefighting.

15 Rhinebeck Fire Department Ladies Auxiliary Scrapbook

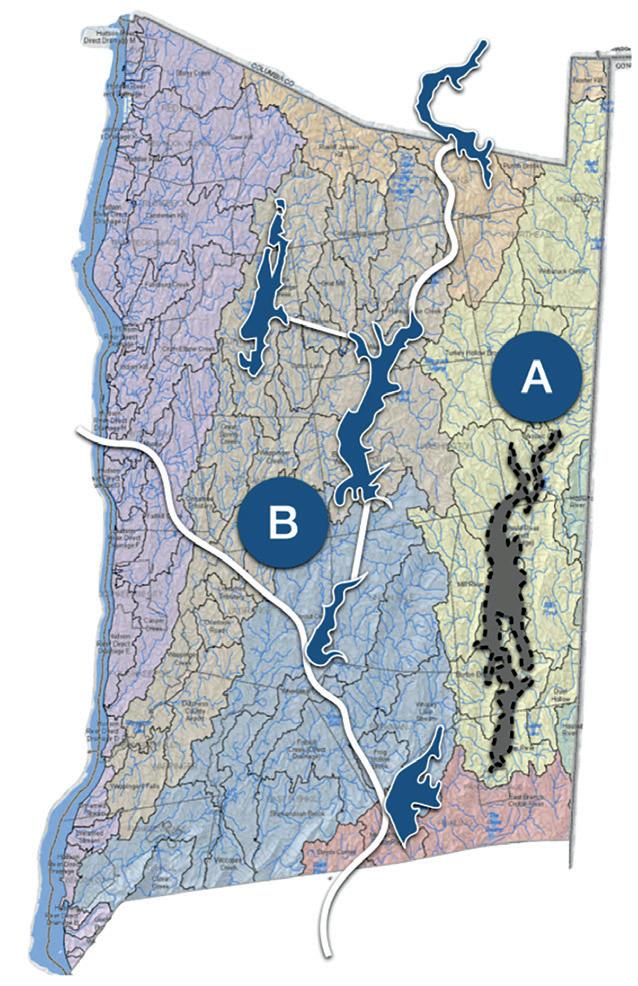

DCHS Executive Director Bill Jeffway reminds us that, no matter how tempting, you just can’t fight fire with fire. It’s one of life’s eternal verities that fire is best–and often only–quenched with water.

From buckets, to reservoirs, to water tanks and towers, our ability to have and to hold water for firefighting exists among many other essential demands. There are few things that we put as many such demands upon as water.

Local rivers and streams were, and to some degree remain, a source of food that ranged from the brook trout to the mighty Hudson River sturgeon. In the first quarter of the 19th century, the invention of the steamboat and the development of canals, like the Erie Canal, rapidly expanded the existing role of rivers and streams to be magnets for settlement and the backbone of the rapidly growing Empire State economy. This is a transactional role of helping get people and goods from point A to point B. In another transactional role, dams along rivers and streams created a backlog of water power that caused the physical turning of a water wheel and eventually the generation of steam power and electricity.

In addition, water has the dual but competing role of cleaning and removing waste from homes and industry, while at the same time offering pure, uncontaminated water for vital personal consumption and use with livestock and broader farming. History shows us that deadly cross-contamination is easily realized unless there is a specific system to manage the distinct roles. In these roles water is used on a daily, hourly, or minute-by-minute basis.

By contrast, water’s essential role in the long tradition of firefighting might be rarely tapped but must be always ready, “on-demand” and of sufficient supply and pressure, because the consequences of any shortfalls are so profound. Through summer droughts and winter ice, from the county courthouse to a rural barn filled with livestock and the autumn harvest, water plays an essential role in protecting physical property and human (and other) life. Firefighters refer to a goal of an early and sufficient “first water,” the time between alarm and first contact with water, as a measurable, competitive goal.

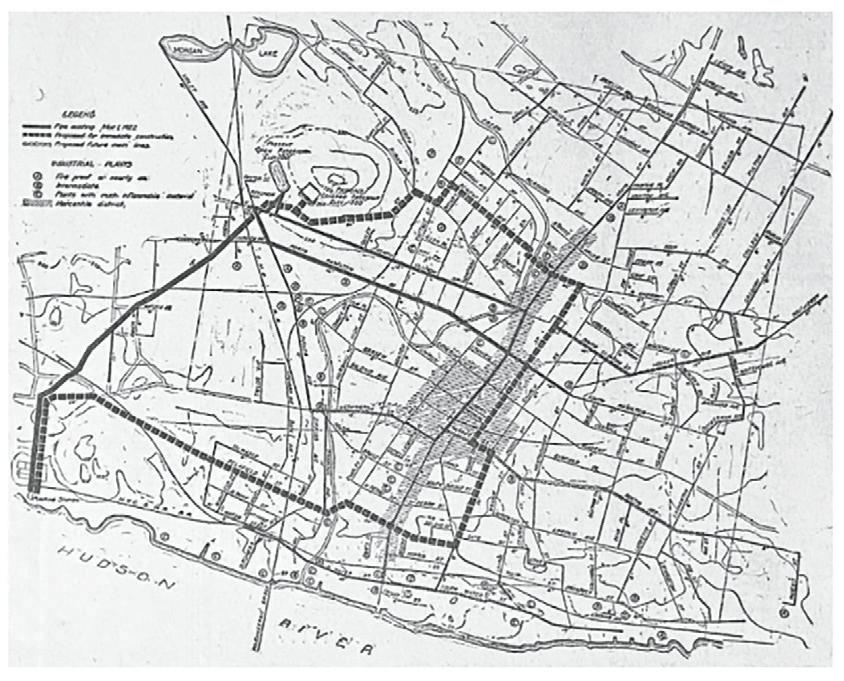

Poughkeepsie is the site of the county’s earliest and most sophisticated firefighting systems in the 19th century, the focus of this article.

Water’s role in navigating both opportunities and deadly threats can be seen in the early story of a founding business: James Vassar’s brewery.

James Vassar (an immigrant from England whose family name, Vasseur, reflected his French ancestry)1 located his brewery on the site of a fresh water spring in 1797 on what is today Vassar Street, a few blocks from the Hudson River. In 1806, advertisements for the sale of land in the area proclaimed a “never failing spring of the best water” as inducement for businesses such as a distillery to locate there.2

The combination of the spring and its adjacency to the Hudson River meant this was an ideal location for a business that planned to receive agricultural goods from inland farmers with a view to creating and distributing a product. James ran the operation with his two sons, John and Matthew. Matthew Vassar went on to be the founder of Vassar College.

Despite its proximity to a spring and the Hudson River, the original

1 Vassar College and Its Founder, by Benson J. Lossing, C.A. Alford, New York, 1867.

2 Poughkeepsie Journal, February 4, 1806, p. 3.

brewery was completely destroyed by fire in April of 1811. While inspecting the fire damage in one of the large brewery vats, John Vassar was overcome by fumes and died. 3 He left two infant boys to be raised by their mother. Those two brothers, third-generation John Jr. and Matthew Jr. (as he came to be called) went on to found the Vassar Brothers Hospital, among other lasting institutions.

Just over 20 years later, in July 1832, on the same newspaper page announcing that the elder Matthew Vassar was bringing his two fatherless nephews into the brewery business, it was noted that a ship carrying wood to the Vassar Brewery was being quarantined just offshore because of a case of deadly cholera.4 Cholera is easily transmitted from infected persons or areas contaminated with untreated waste. Villagers were assured the case was isolated and all was well. But within three weeks, over 100 cases resulted in 75 deaths in the village with a population of 7,000.5

Although cholera was very much misunderstood at the time, there was an accurate awareness that drinking water contaminated by “filthy” wastewater was a major contributing source.

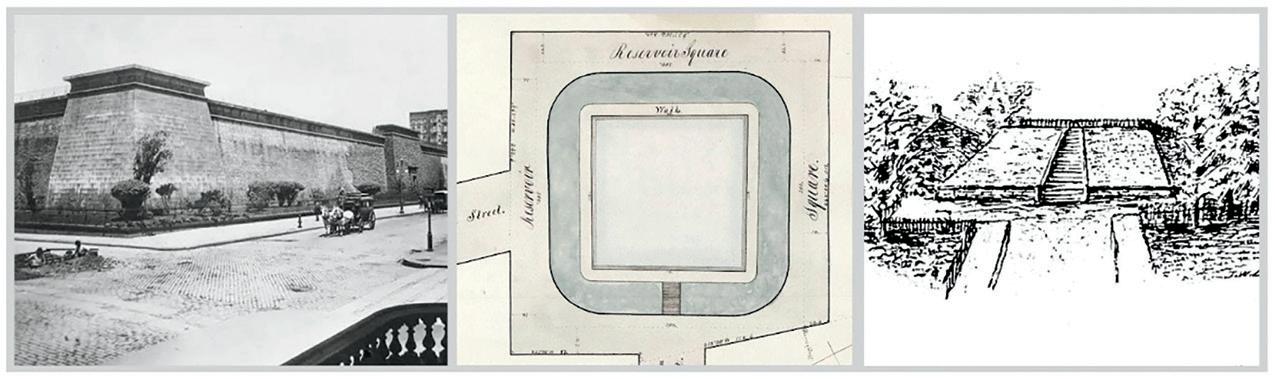

So Matthew Vassar was aware of all the dimensions of water: its potential to protect and support – or thwart – personal health, safety and economic growth. It is not surprising, then, that he was active with the Improvement Party and a special committee that created a village reservoir for firefighting in 1834 at what is today still called Reservoir Square on Cannon Street. Subsequently, he headed up the Poughkeepsie Aqueduct and Hydraulic Company in 1853, which would for the first time express a wish to provide not just fire protection but clean drinking water, a goal not realized until 1872, after his death.

With an understanding of the opportunities and risks, and the variety of demands put on water, we will now look at the evolution of local

3 Poughkeepsie Journal, May 15, 1811, p. 3.

4 Poughkeepsie Journal, July 18, 1832, p. 2.

5 Poughkeepsie Journal, August 15, 1832, p. 2.

firefighting systems, focusing on Poughkeepsie, which had the earliest and most sophisticated systems..

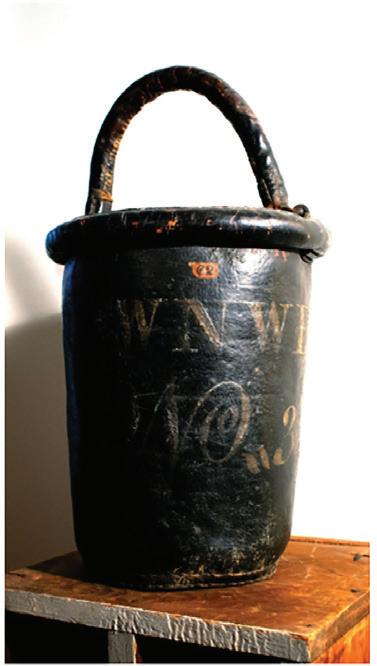

Above: Early 19th century fire bucket. DCHS Collections. Gift of the Mahwenawasigh Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution.

The earliest form of firefighting involved bucket brigades with water sourced from wells, pumps and cisterns. In addition, some firefighters were formally identified as “bag men” whose role was to start removing furniture and other items to save them from the very likely event that the whole building would be consumed beyond anyone’s control. Beds were designed with a special key that could allow their easy disassembly and removal.

Municipalities required residents to own a certain number of fire buckets, which always featured family name and number. A public call for inspections would appear in the newspaper, giving short notice. The “hands” deployed in this very manual process were the residents, generally under the direction of appointed fire wardens.

At the request of the trustees, fire wardens and firemen of this village, the inhabitants are requested to meet at the courthouse on the first Tuesday in June next, at 4:00 p.m. and to bring with them their fire buckets for the purpose of improving themselves in the management of the engine, forming ranks and other things necessary for the extinguishment of fire.6

The alarm would be sounded and the nearest wells and cisterns would be located. A well is so defined if it produces water which could be

6 Poughkeepsie Journal, May 31 1803.

pulled out through the lowering and raising of a bucket or hand pump; there was generally a town pump in the center of any village. A cistern is simply a specifically-designed storage area for water, frequently constructed so that they are filled by rainwater from roofs and gullies.

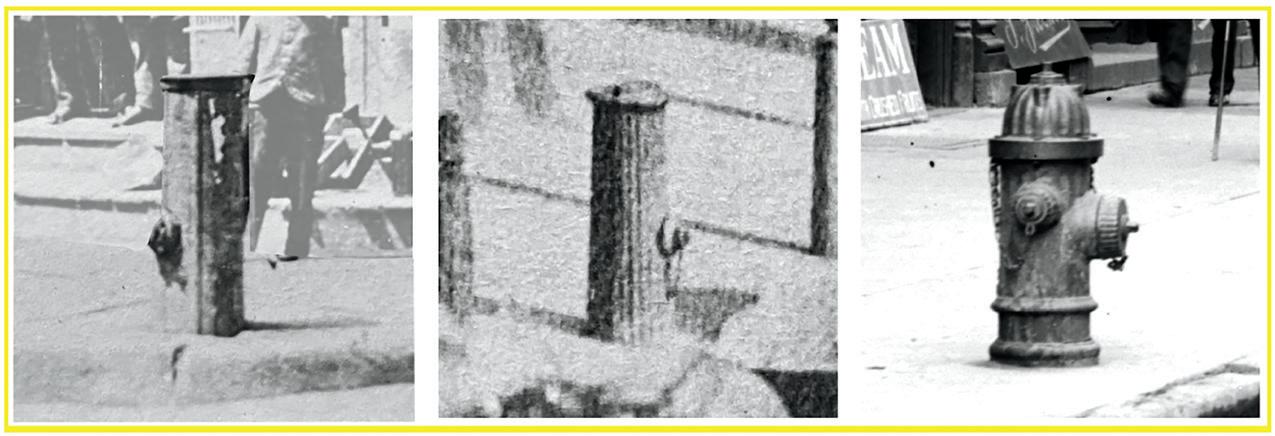

On May 3, 1803, the village trustees voted that $250 will be raised for the purpose of digging wells, “or otherwise supplying the fire engine with water, for repairing or procuring fire hooks and hoses to the engine, and for other contingent purposes for the ensuing year.”

In 1819, the Village of Poughkeepsie announced it would create underground cisterns at the following streets: Main and Hamilton, Main and Perry, Market and Church, and Market and Union. By 1830 they had not been built due opposition coming from those who objected to the taxpayer expense.7

Above top: Depiction of a “goose neck” pumper. The Rhinebeck Fire Department continues to maintain “Pocahontas” in a high state of preservation. Shown outside DCHS in Rhinebeck, August 2024. Photo by Bill Jeffway.

7 Poughkeepsie Journal, October 16, 1830, p. 2.

Whether the source was a cistern or the Hudson River, wherever and whenever gravity was working at cross purposes to the effective flow of water, “pumpers” were used that were originally powered manually. It would not be unusual to have three pumpers (see illustration of Gooseneck pumper) with one at the source, one near the fire and one in the middle so that a total of 36 men (12 each) were involved in working against gravity and getting water of sufficient volume and pressure to and on the fire.8 Wells and cisterns were often pumped dry before a line of hose from the nearest hydrant could be laid.

Some of the worst fires in this period resulted in the complete destruction of the courthouse in 1785 and the complete destruction of its replacement in 1806,9 as well as the Vassar Brewery in 1811 mentioned earlier. The most effective solution was the construction of a reservoir at an elevated site to allow sufficient water pressure that would need to be kept filled and kept from freezing, although this model had limitations in that the reservoir would only effectively cover whatever area had pipes laid and “hydrants” installed.

In 1834, the Improvement Party and a committee focusing on water involving Matthew Vassar and other local business leaders who understood the interdependency of economic and industrial growth and water.10

The group argued that the ability of the village (with an eye on becoming a city) to attract investment and experience economic growth would depend, among other things, on the ability to extinguish fires with a degree of effectiveness that fire insurance could be had at a reasonable price. The cost of fire insurance was one of the clearest

8 The Eagle’s History of Poughkeepsie From the Earliest Settlements 1683 to 1905, by Edmund Platt, Platt & Platt, 1905.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

measurable benchmarks that could be affected by formally assessed firefighting readiness.

So among the list of ambitious projects like railroad engine manufacturing, silk manufacturing and establishing College Hill as the site of a world-class educational institution was water management. The plan was to have a reservoir that would be more than functional; it had to be appealing visually. The massive reservoir built at roughly the same time on 42nd Street in Manhattan was an inspiration. Although the Poughkeepsie proposal was a fraction of the size, it similarly had a gravel promenade around the perimeter with wonderful views.11

Above left to right: The New York City Reservoir at 42nd Street at Fifth Avenue was designed in 1837 and stood for a half century after opening in 1842. New York Public Library Middle: The Van Vliet survey for construction of a Poughkeepsie reservoir in 1834 that was a fraction of the size. From DCHS Collections. Sketch of the reservoir published by the Poughkeepsie Eagle News in 1911. Both reservoirs afforded a promenade around the top for pleasure walks and beautiful views.

The reservoir was built, with the sole purpose of firefighting, and positive reports were quickly achieved. In September of 1835 the Poughkeepsie Journal reported,

Among the most important public improvements we would especially notice the reservoir, a substantial work of considerable labor and cost and highly creditable to its persevering projectors. Under the efficient superintendence of one of your townsmen, Captain Harris, the work has just been completed. The basin is 104 feet square and about nine feet deep so that when filled the water will be on a level with the highest peak

11 “Poughkeepsie Past and Present,” Poughkeepsie Eagle, Anniversary Issue, 1911.

of the Court House. The whole is surrounded by a neat gravel promenade, from which the view is beautiful and picturesque. The eye, glancing over a thriving and well-built village, is lost in a luxuriance of the surrounding scene. There is no town or city in the whole country better supplied with water for extinguishing fires or for culinary purposes.12

Although culinary or domestic purposes were mentioned, they were not the focus of the reservoir at that time.

But the news was not entirely positive. The reservoir was kept filled with water by diverting some of the nearby Fall Kill pumped by a water wheel. An early example of the competing demands put on water, this caused friction and even legal action with mill owners along the Fall Kill. 13

Imagine how deflating it was when on May 12, 1836, Poughkeepsie had one of its most destructive fires. The severe drought of the fall of 1835 had prevented it from getting any water until after the middle of December; moreover, it was out of water from undergoing repairs on the night of the fire. The message was clear there was work to be done on fire protection.

During this reservoir’s tenure (1834-1872), there were a number of “improvements” explored that were not realized.

In 1849 there was an exploratory plan to fill the Cannon Street reservoir by using a steam engine to pump the Hudson River rather than the Fall Kill. The greater volume and reliability was said at the time to allow for an expansion of fire hydrants and to allow for drinking water. The plan was ultimately abandoned.14

There was an exploratory plan looking at diverting water from what

12 Poughkeepsie Journal, September 23, 1835 page 2

13 Poughkeepsie’s Water Supply, J. Wilson Poucher, MD, Dutchess County Historical Society Yearbook, 1942. p. 65.

14 Poughkeepsie Eagle News, July 21, 1849.

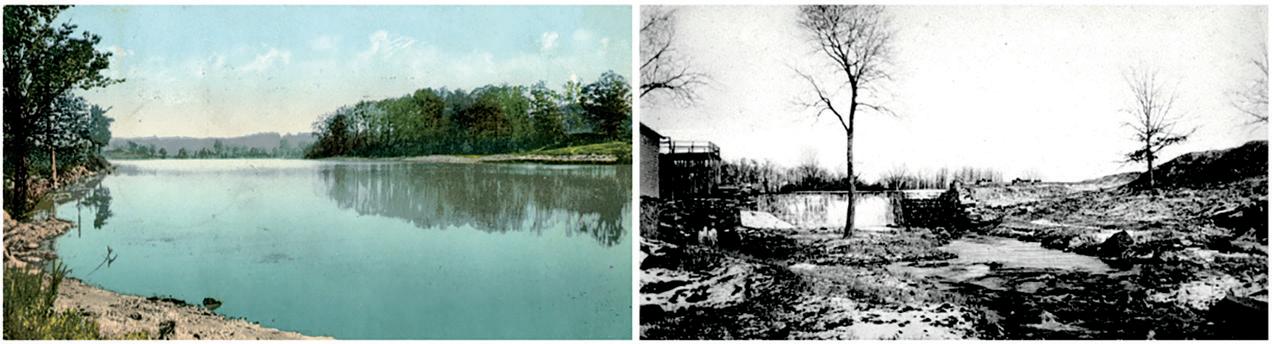

is today Vassar Lake at Vassar College onto the city system. Vassar College was built adjacent to Casper’s Kill as a water source, a stream that empties into the Hudson at today’s Stoneco, a massive mining operation six miles south of the village. But that never materialized.15

In 1870 plans emerged to divert a much greater amount of water from the Fall Kill by creating a dam further upstream, but that did not materialize.

One of Poughkeepsie’s worst fires took place on December 26, 1870, with the complete destruction of the Pardee block at Main and Garden Streets, resulting in the building of the more fire-proof cast iron building that stands today. Something had to be done.

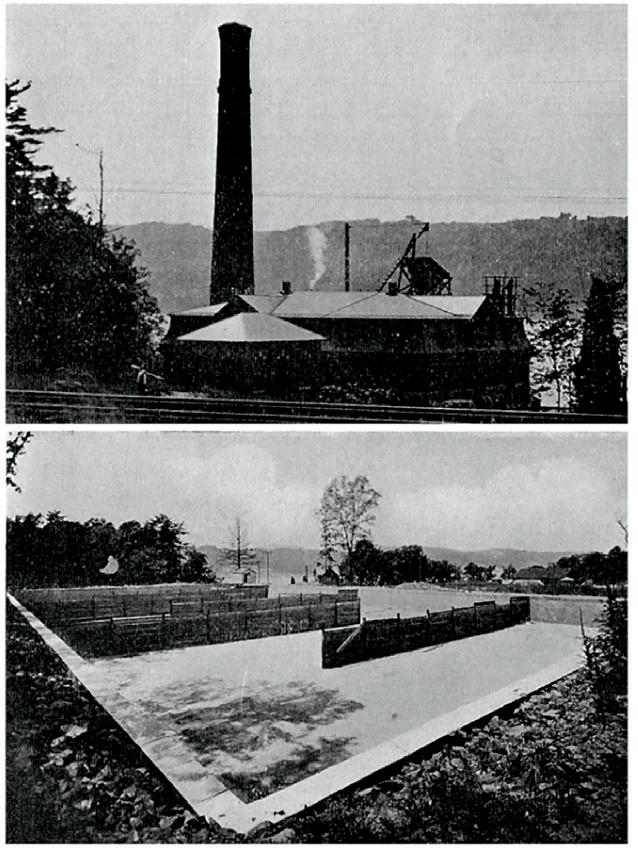

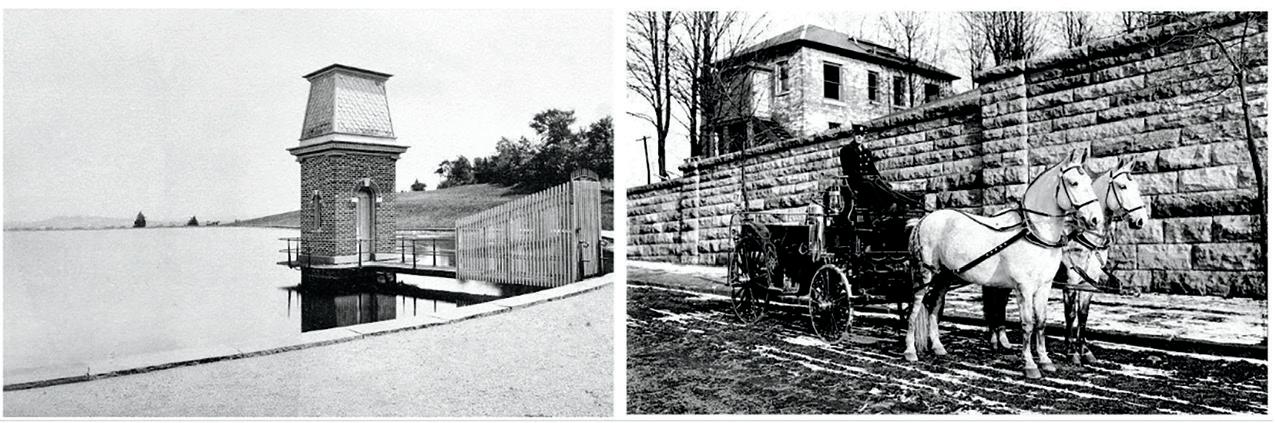

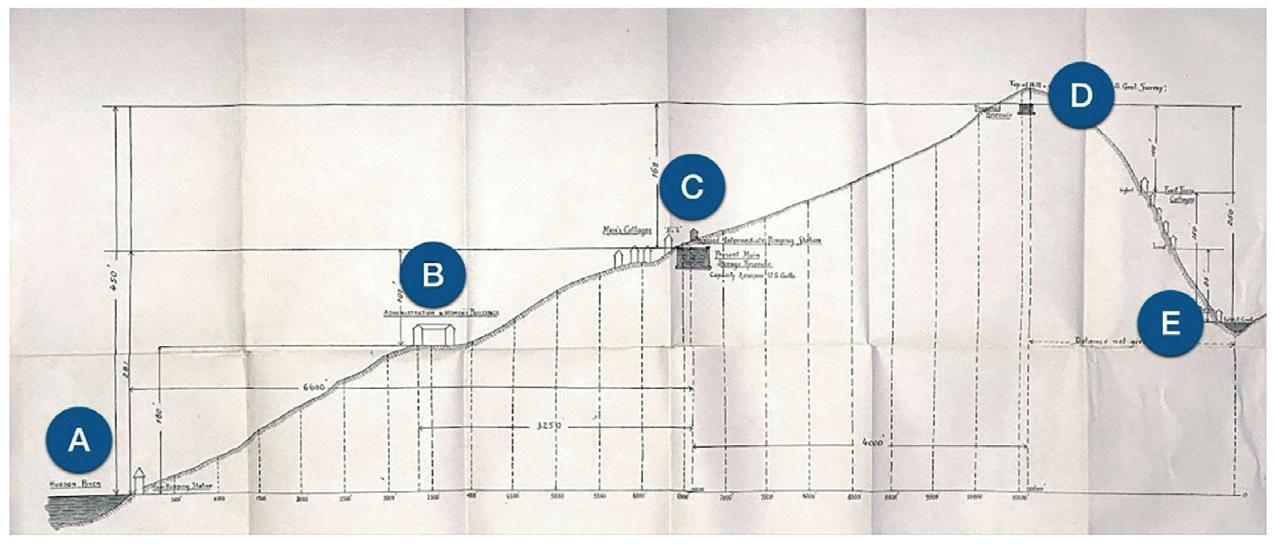

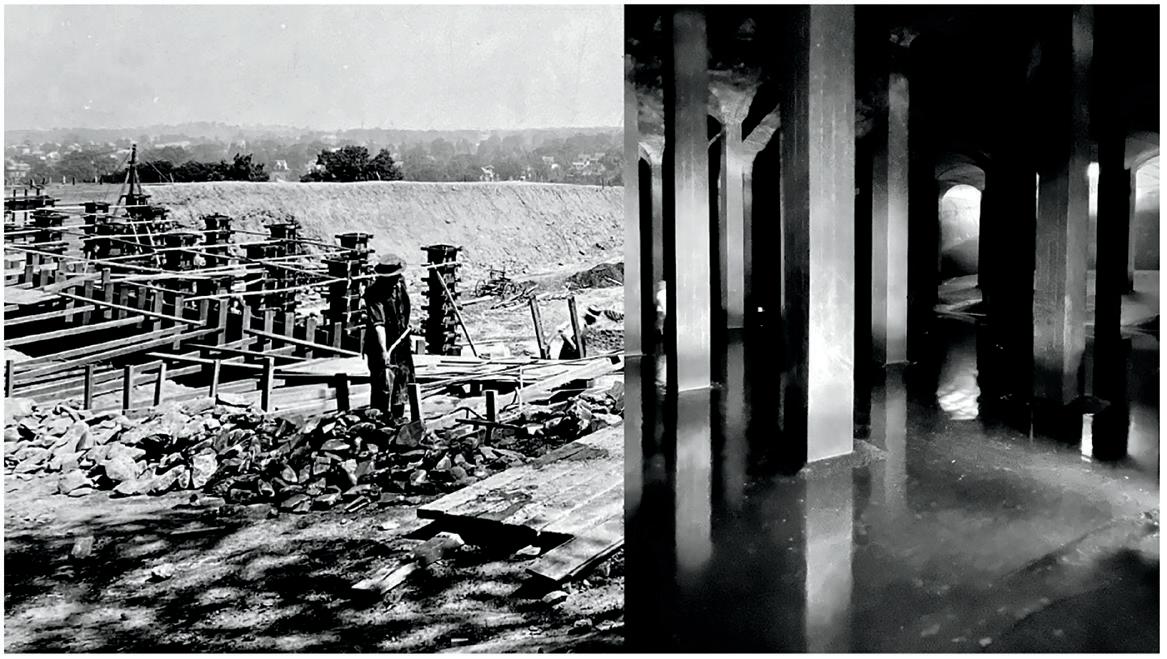

In 1872, a solution that would finally address not just firefighting but drinking and waste water was realized. Water was (and remains) sourced from the Hudson River, with a pumping, filtration and treatment station at the river’s edge, and a large reservoir of theoretically clean water on top of College Hill. This two-stage process remains today in basic form and function with greatly advanced technology

This plan was not without shortcomings. Public concern about upstream sewage contamination of the Hudson River, in particular from the Hudson Valley State Hospital less than a mile upstream, emerged as valid challenges.

By 1902, it was deemed necessary to convert the open filtration beds to covered underground ones. This change did not prove entirely effective.

There were still major devastating fires. During this period, the

15 Poughkeepsie’s Water Supply, J. Wilson Poucher, MD, Dutchess County Historical Society Yearbook, 1942. p. 66.