Profiles of the American Revolution Since 1914

Encore Edition 2025

Editors

AidanChisamore

Bill Jeffway

Melodye Moore

William P. Tatum III, Ph.D. Advisor

The Dutchess County Historical Society is a not-for-profit educational organization that collects, preserves, and interprets the history of Dutchess County, New York, from the period of the arrival of the first Indigenous Peoples until the present day. Published annually since the 1914 issue.

The Dutchess County Historical Society Yearbook does not assume responsibility for statements of fact or opinion made by the authors.

©Dutchess County Historical Society 2025

Dutchess County Historical Society

6282 Route 9, Rhinebeck, NY 12572

Email: contact@dchsny.org www.dchsny.org

Foreword v by Bill Jeffway

Introduction vii by Willaim P. Tatum III, Ph.D., Dutchess County Historian

Bartholomew Crannell a Twentieth Century Plea for Anglo-American Good Will 1 by Helen Wilkinson Reynolds

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period: John Jay 23 by J. Wilson Poucher

Dedication of Monument, Chambly, P.Q. (Province of Quebec) 29 by Mrs. Theodore de Laporte

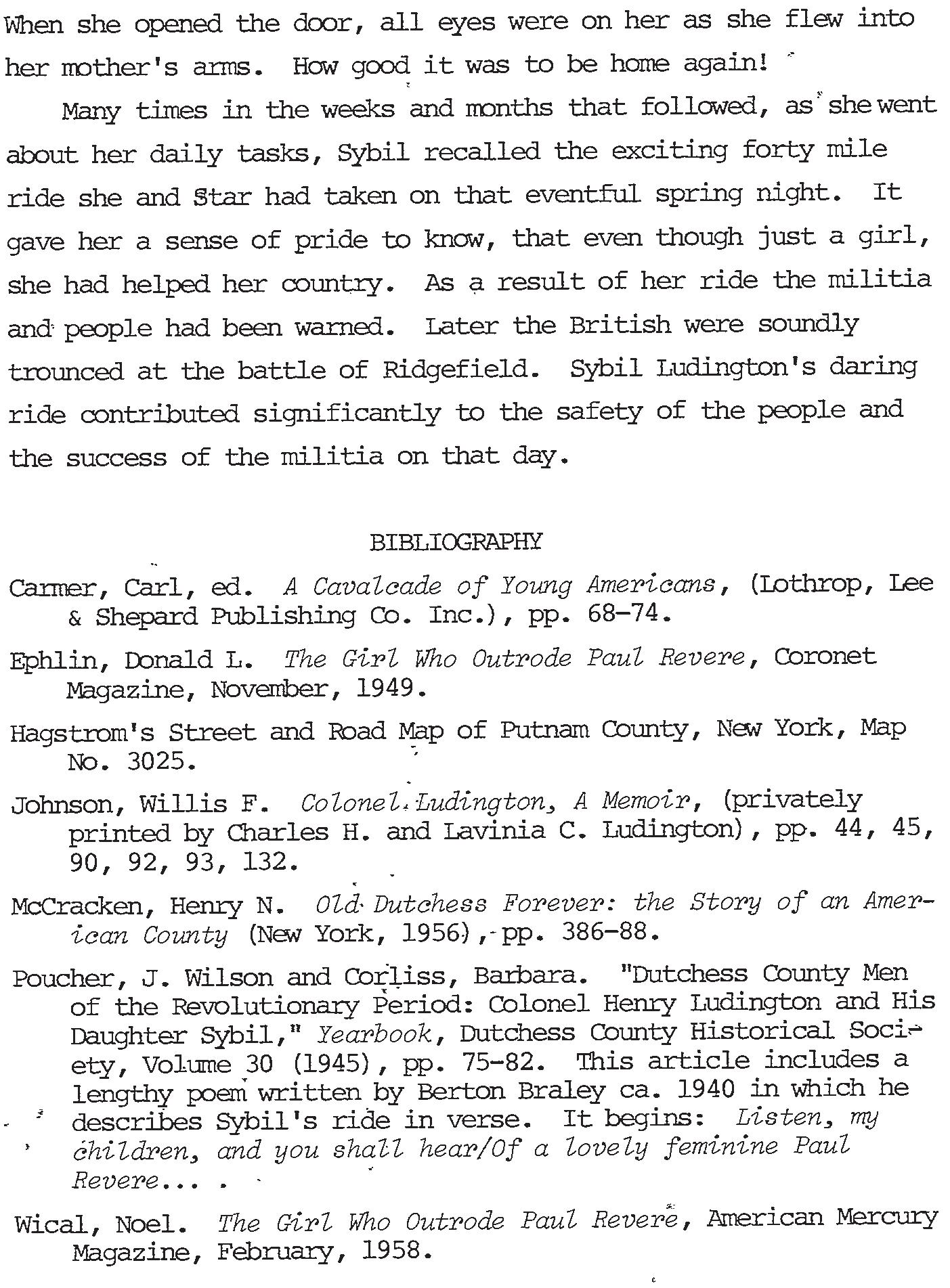

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period:

Smith 35 by J. Wilson Poucher

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period: Udny Hay 46 by Helen Wilkinson Reynolds

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period: Captain Israel Smith 58 by J. Wilson Poucher

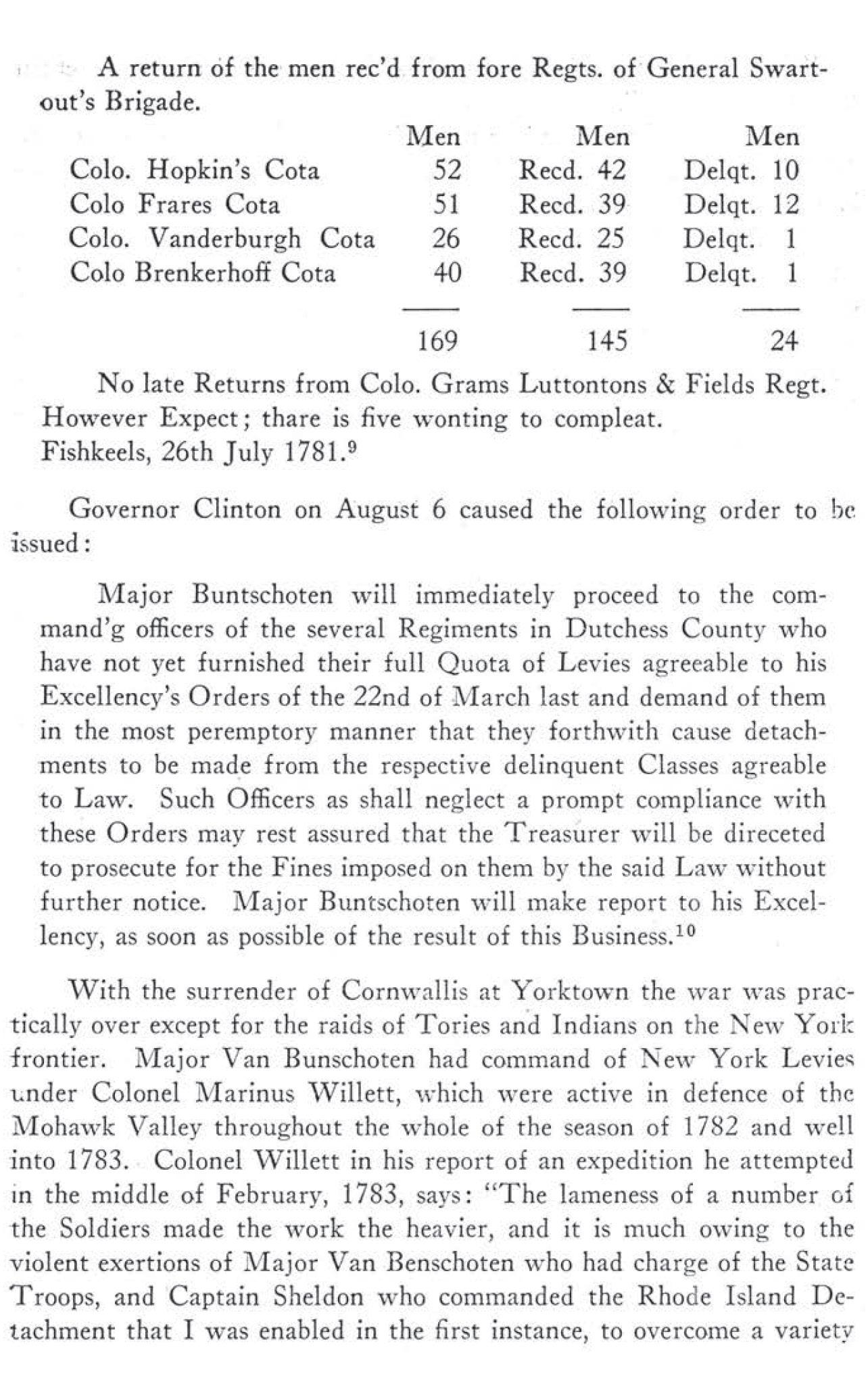

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period: General Jacobus Swartwout 64 by J. Wilson Poucher

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period: Philip Schuyler 70 by J. Wilson Poucher

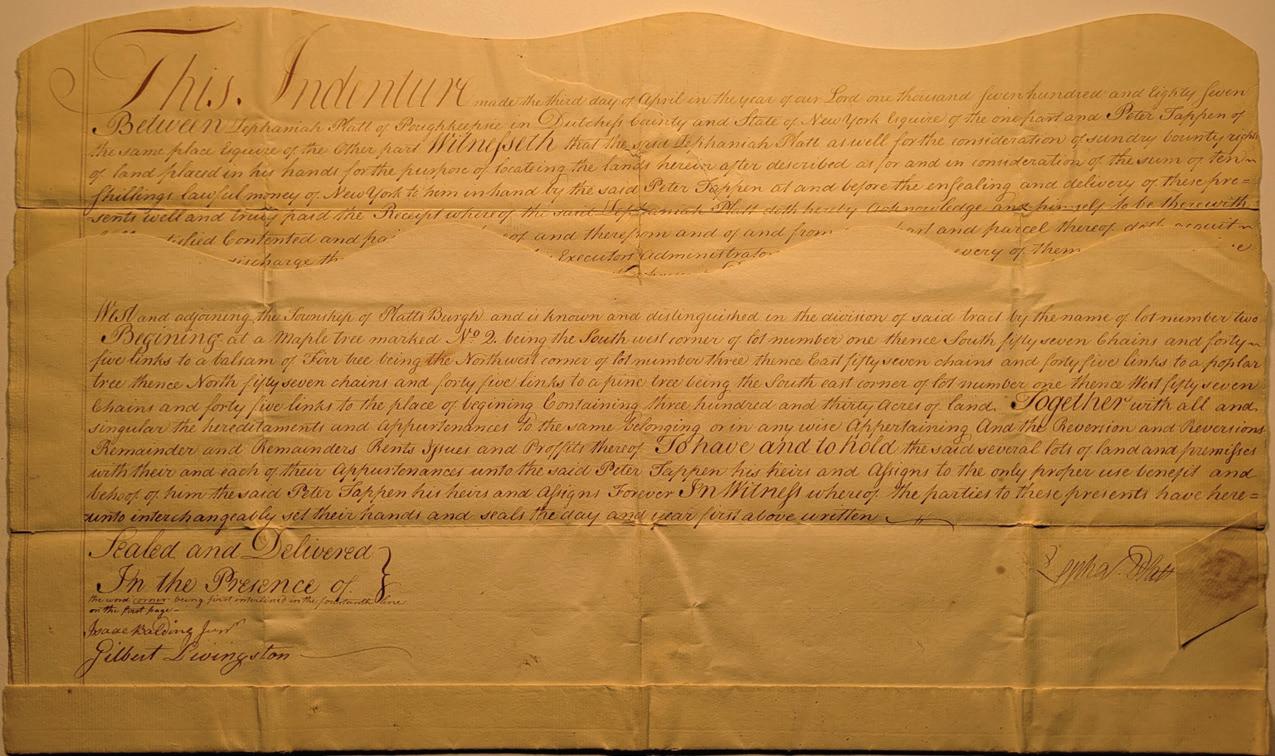

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period: Dr. Peter Tappen 79 by J. Wilson Poucher

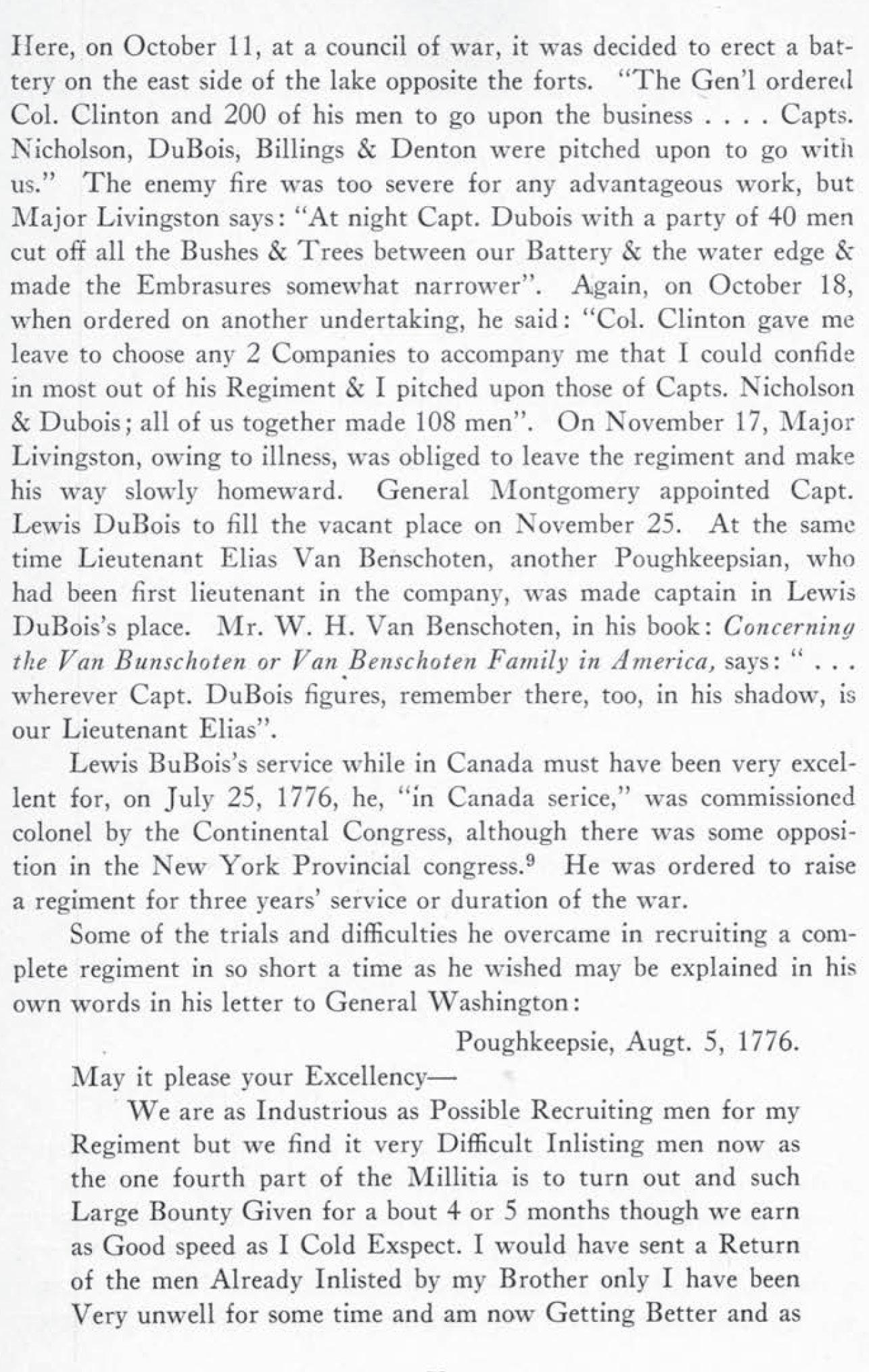

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period: Colonel Lewis DuBois; Captain Henry DuBois 87 by J. Wilson Poucher

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period:

Major Elias Van Bunschoten 103 by J. Wilson Poucher

Monument to Chief Daniel Nimham 113 by J. Wilson Poucher

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period:

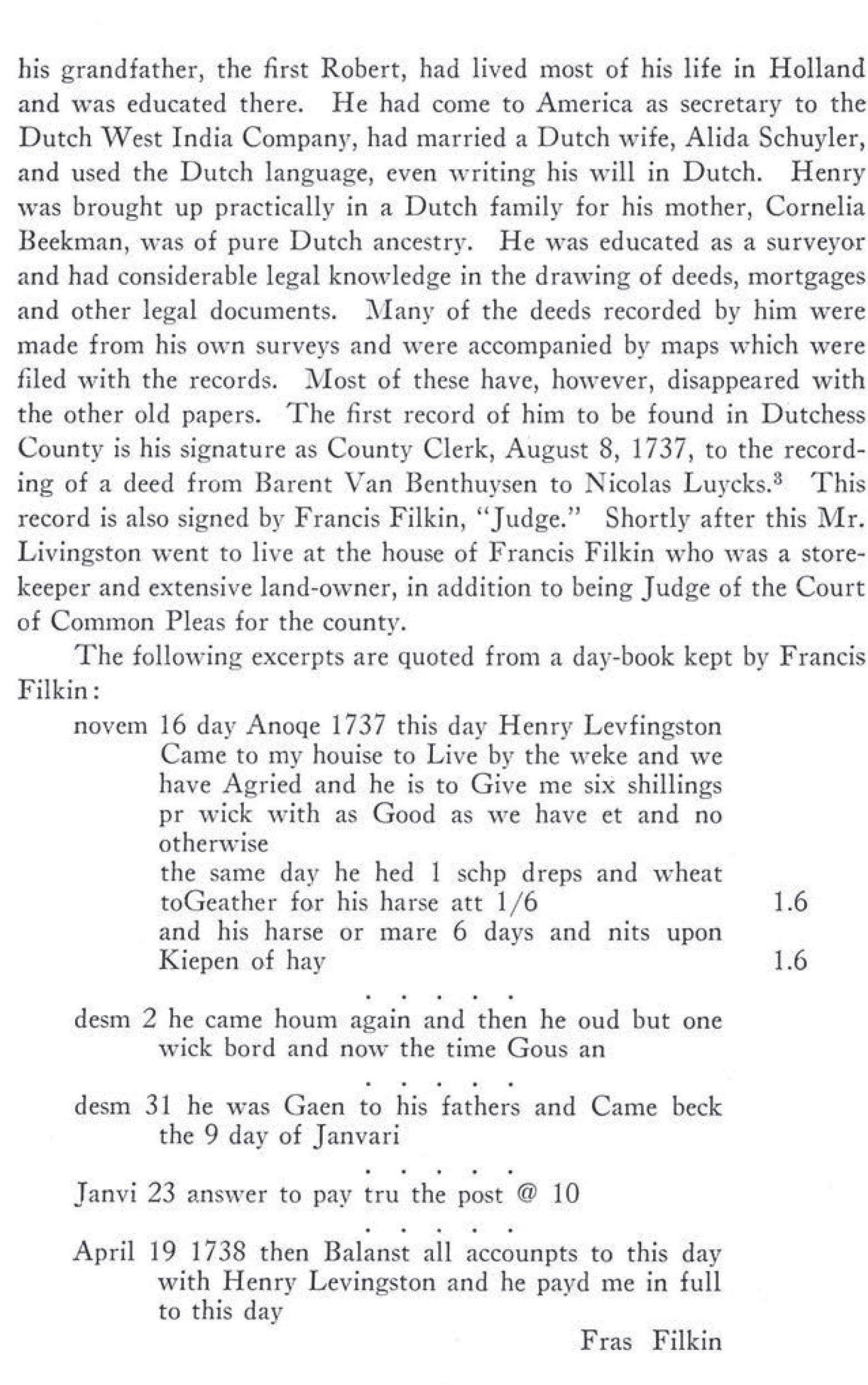

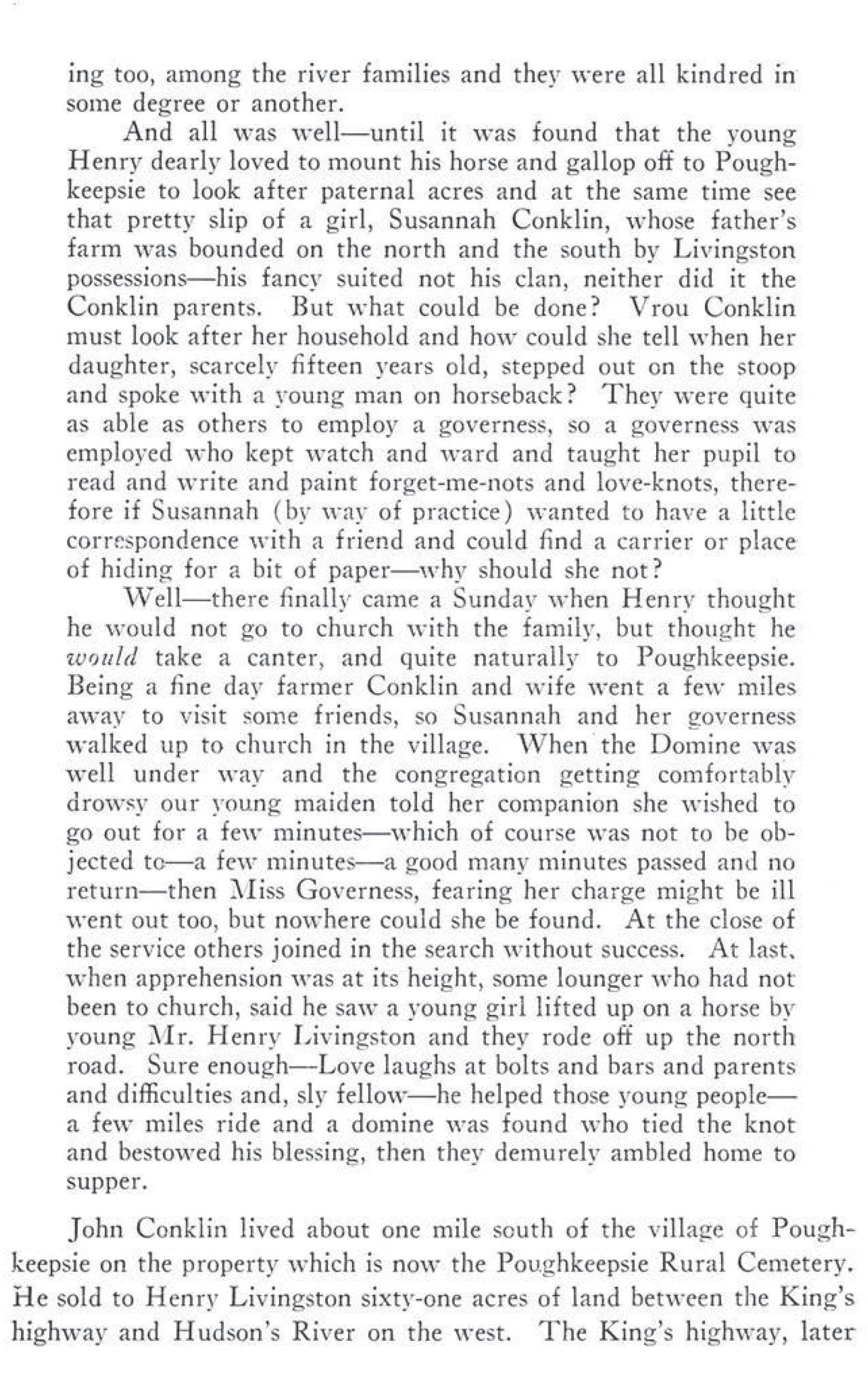

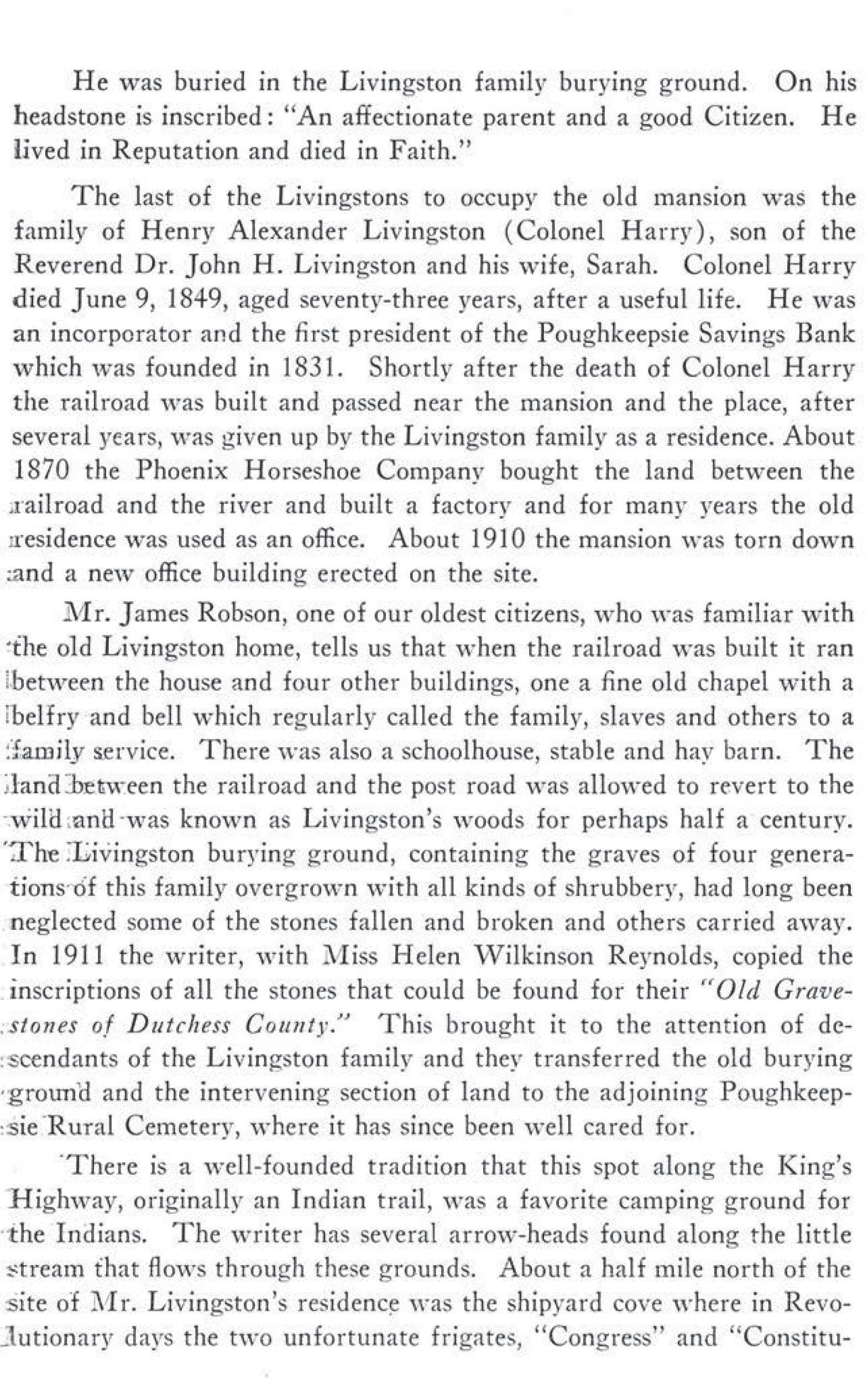

Henry Livingston 116 by J. Wilson Poucher

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period:

Major Andrew Billings 130 by J. Wilson Poucher

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period:

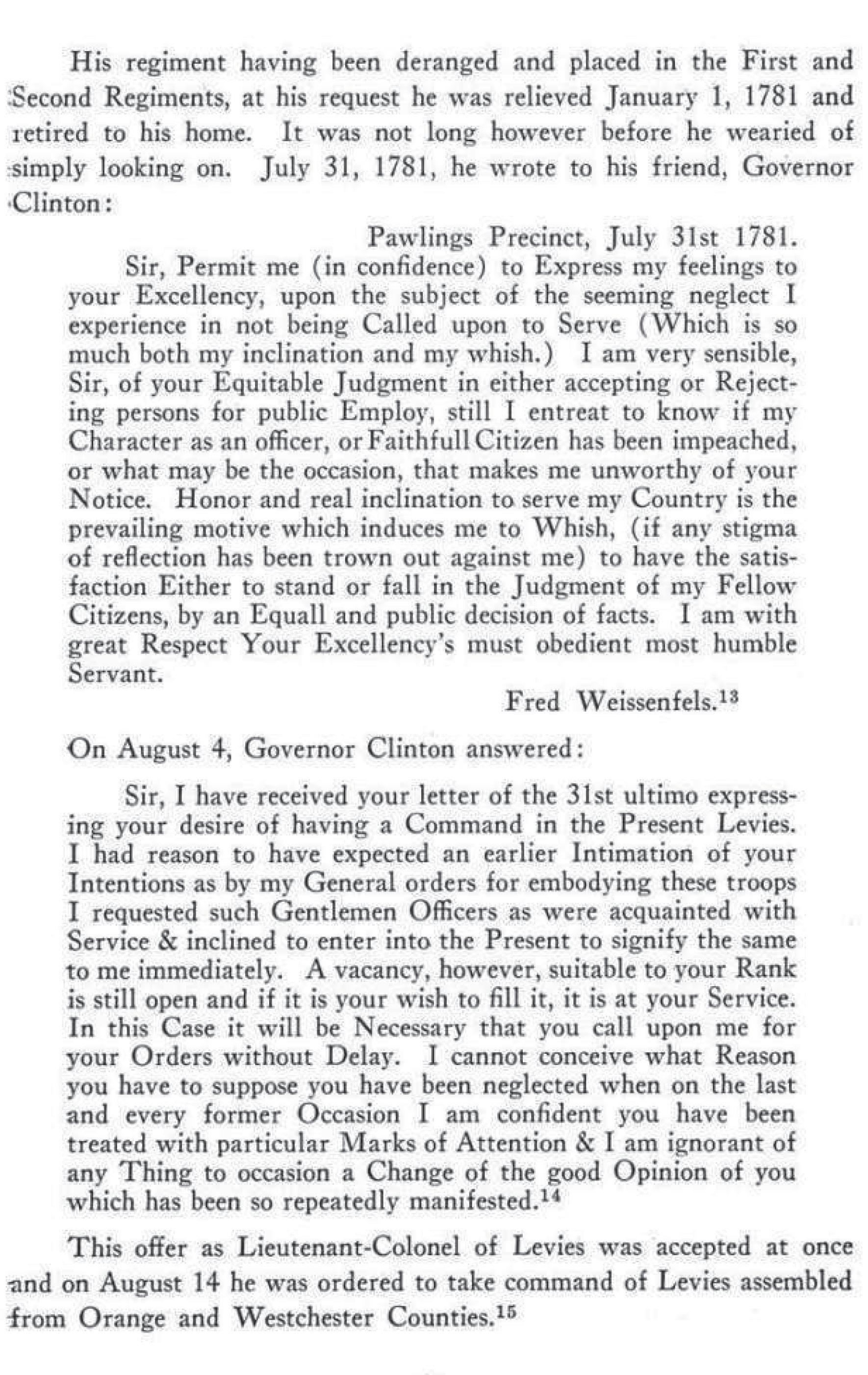

Colonel Frederick Weissenfels 137 by J. Wilson Poucher

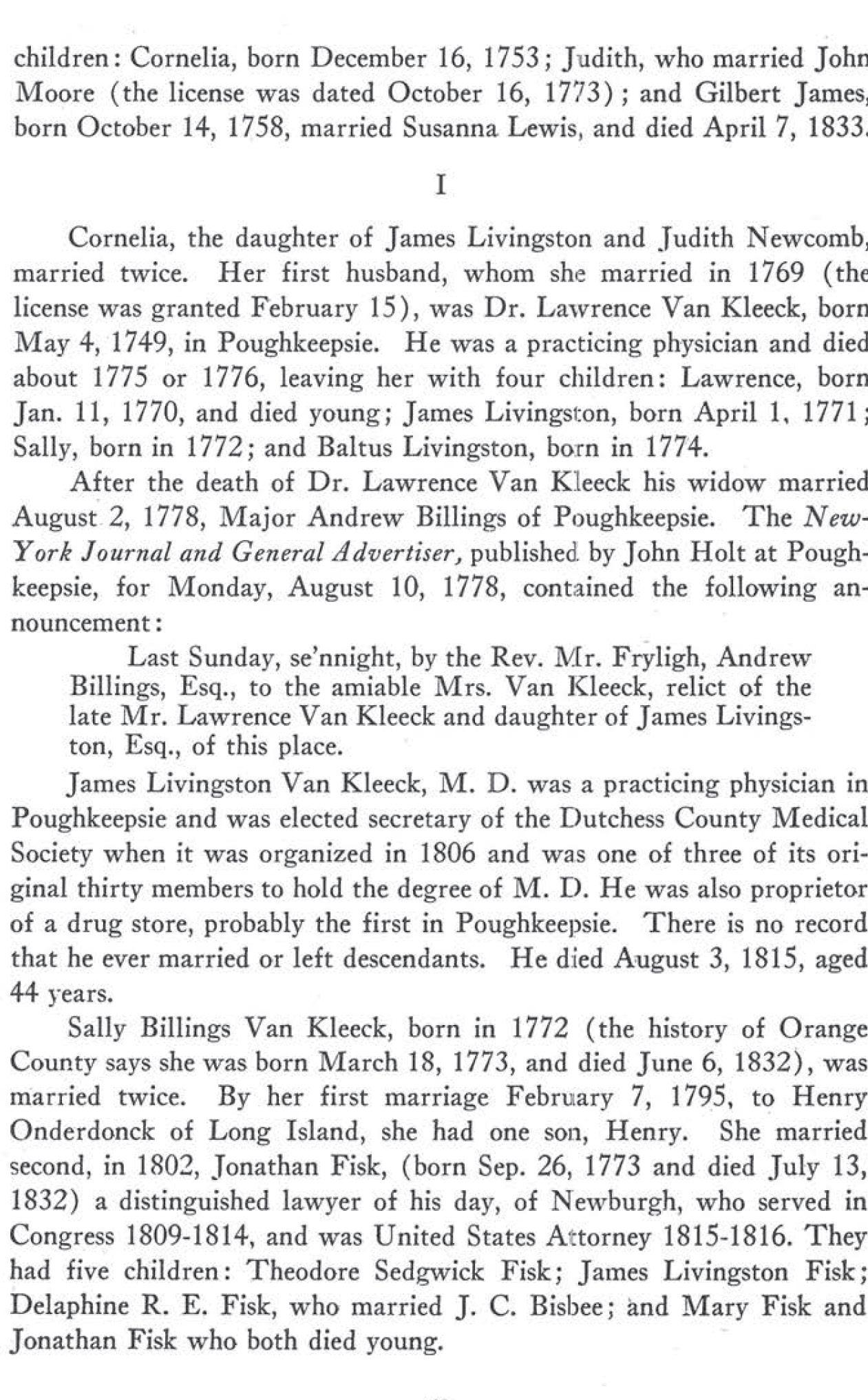

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period:

James Livingston and Some of His Descendants 149 by J. Wilson Poucher

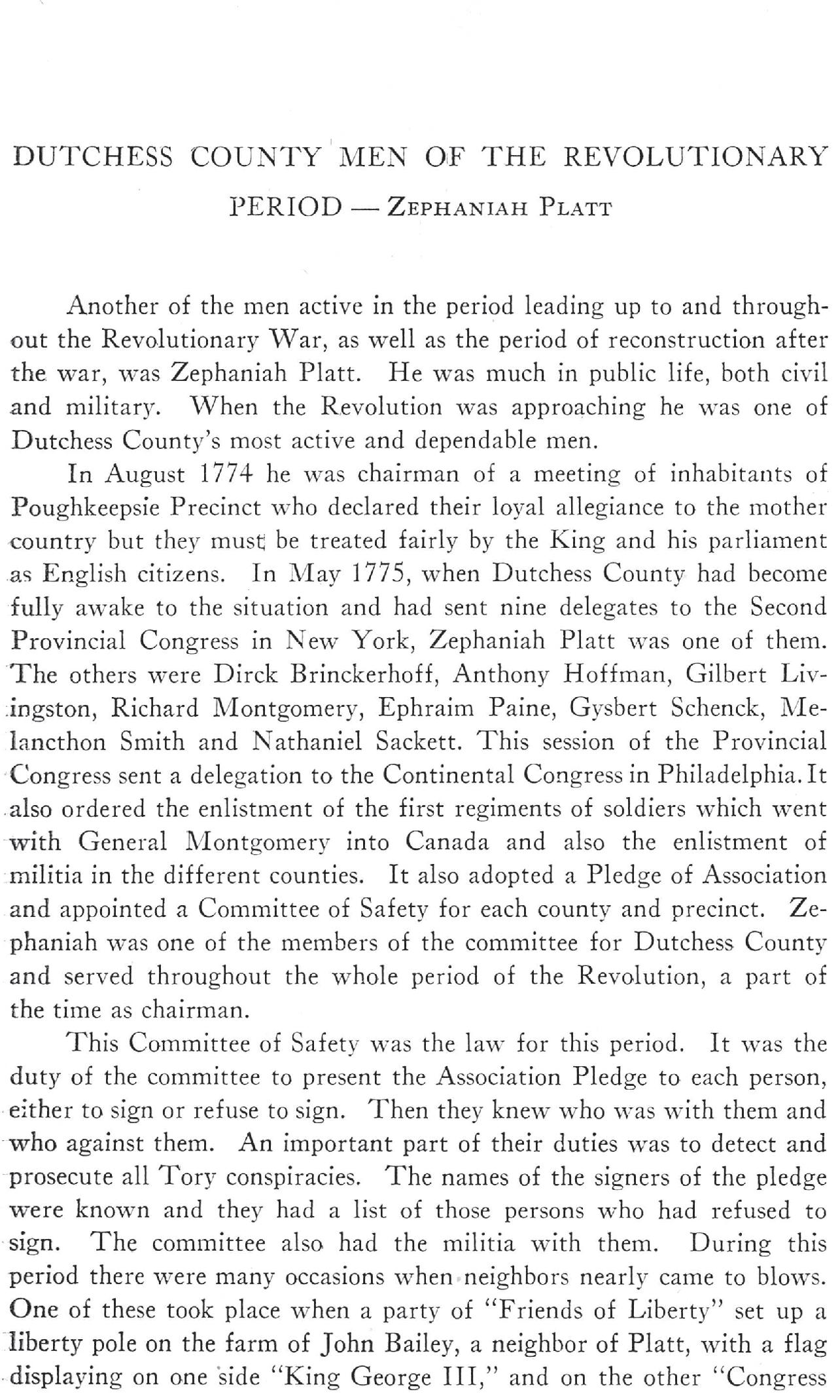

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period:

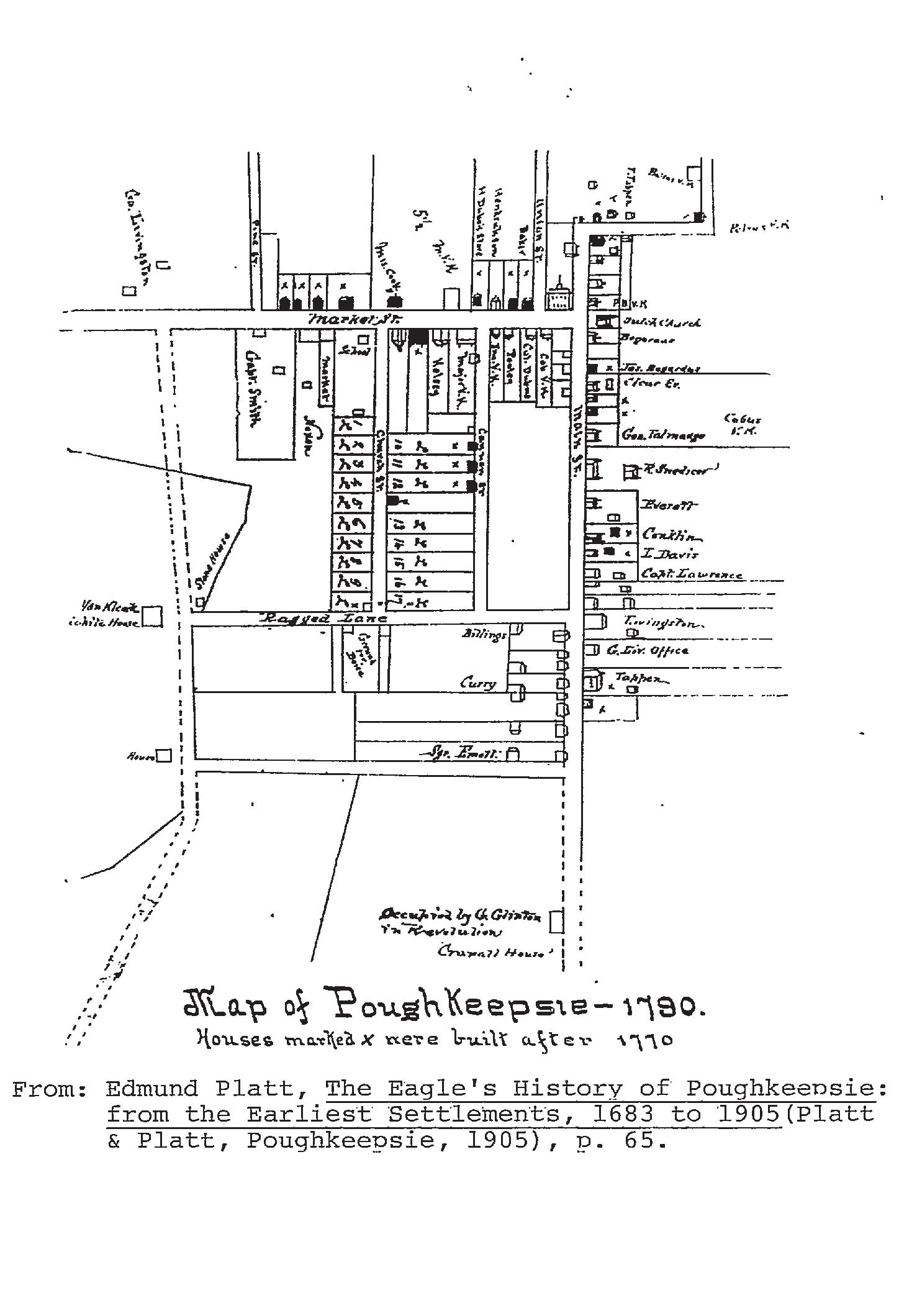

Zephaniah Platt 160 by J. Wilson Poucher

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period:

Judge Robert R. Livingston, His Sons and Sons-in-Law 166 by J. Wilson Poucher

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period:

Colonel Henry Ludington and His Daughter Sybil 188 by Barbara Corliss and J. Wilson Poucher

Dutchess County Men of the Revolutionary Period:

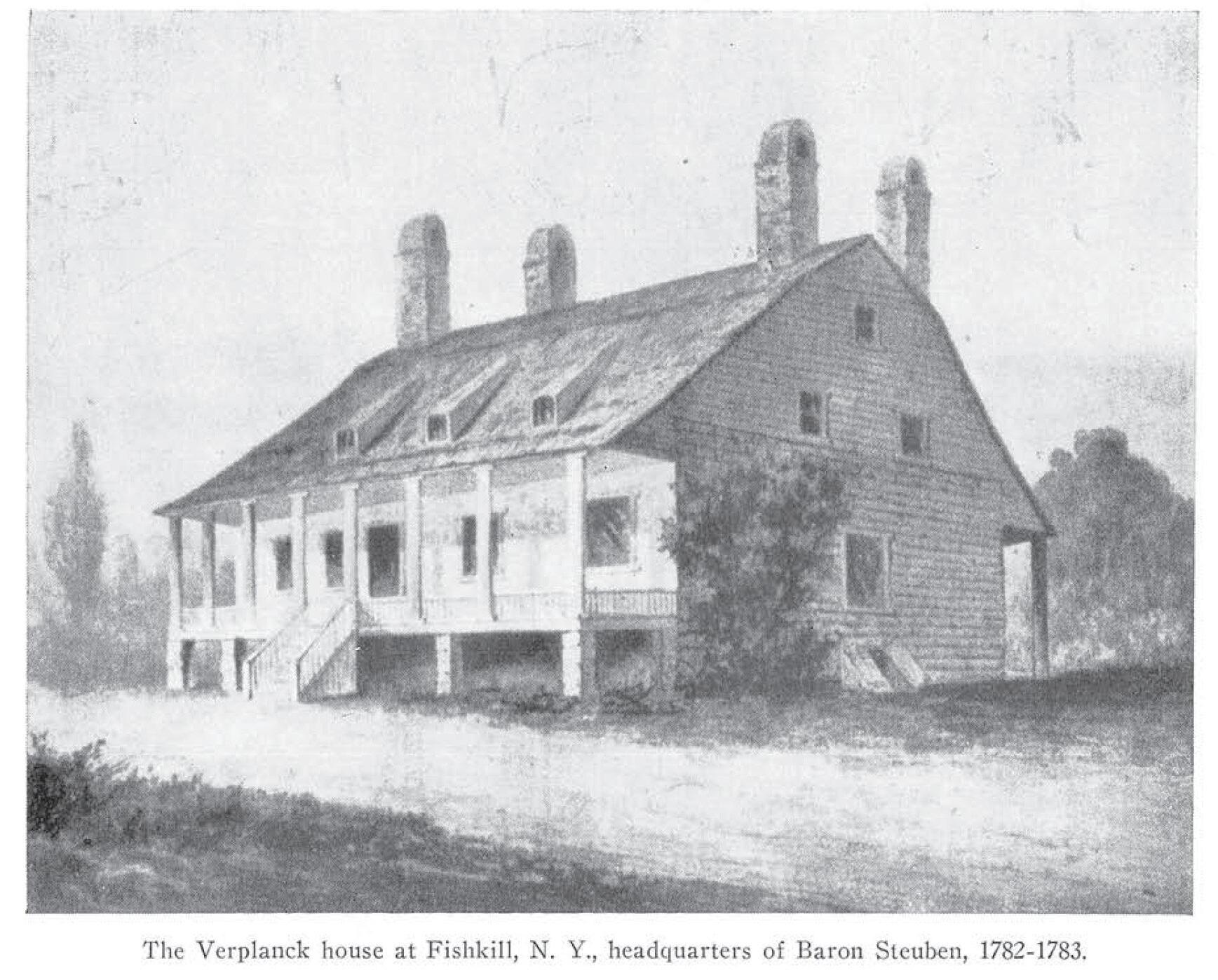

Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben 197 by J. Wilson Poucher

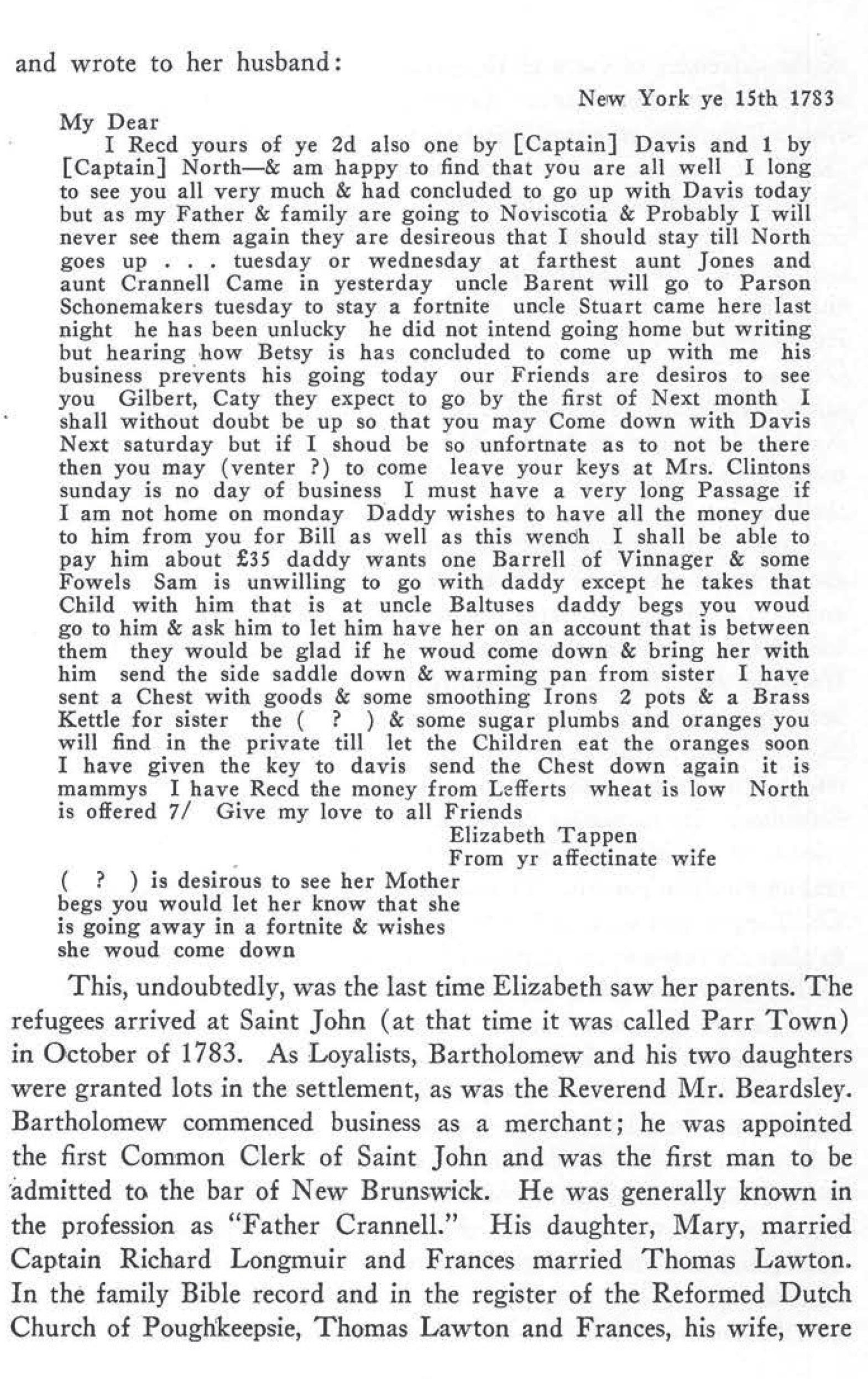

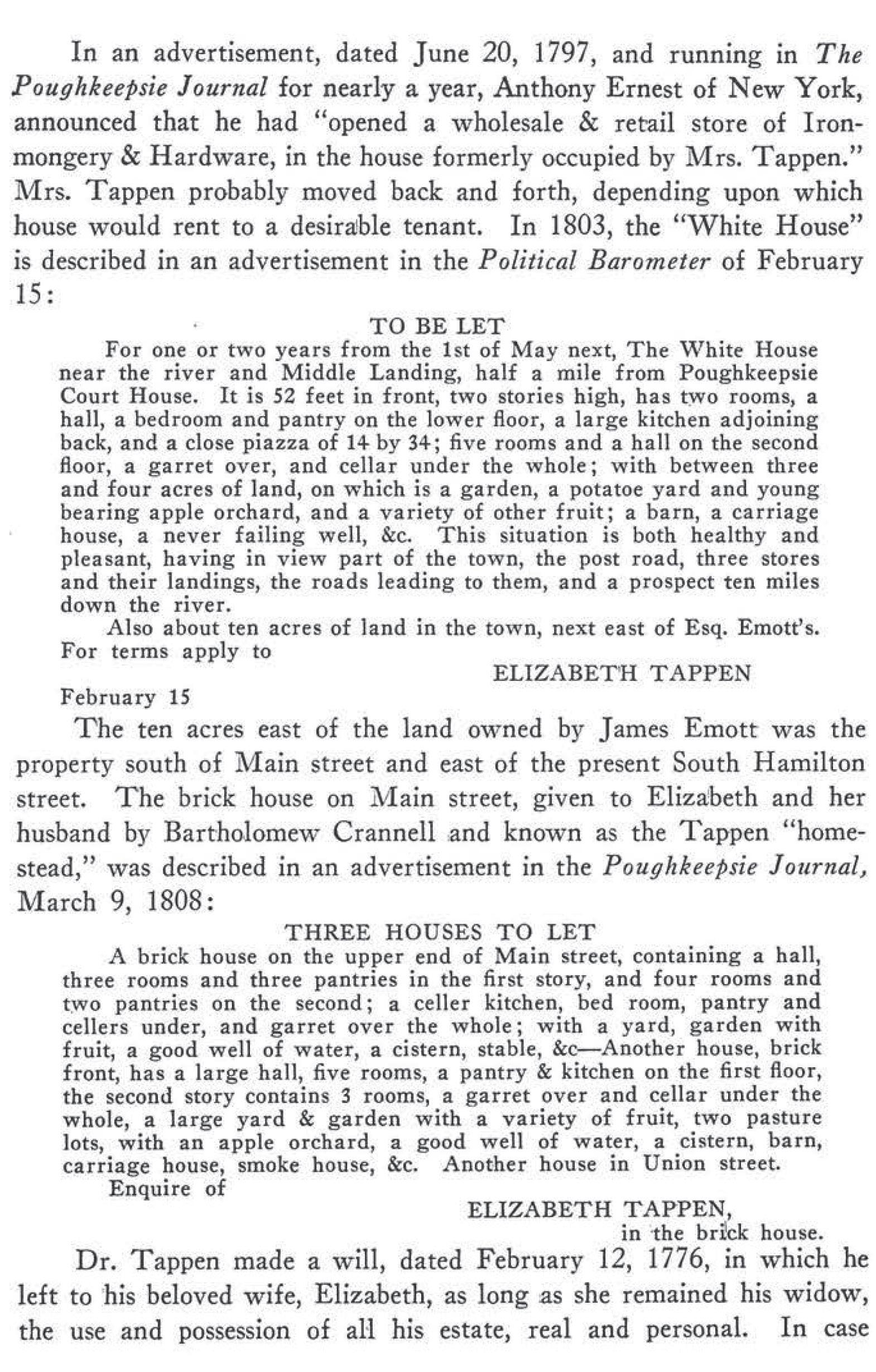

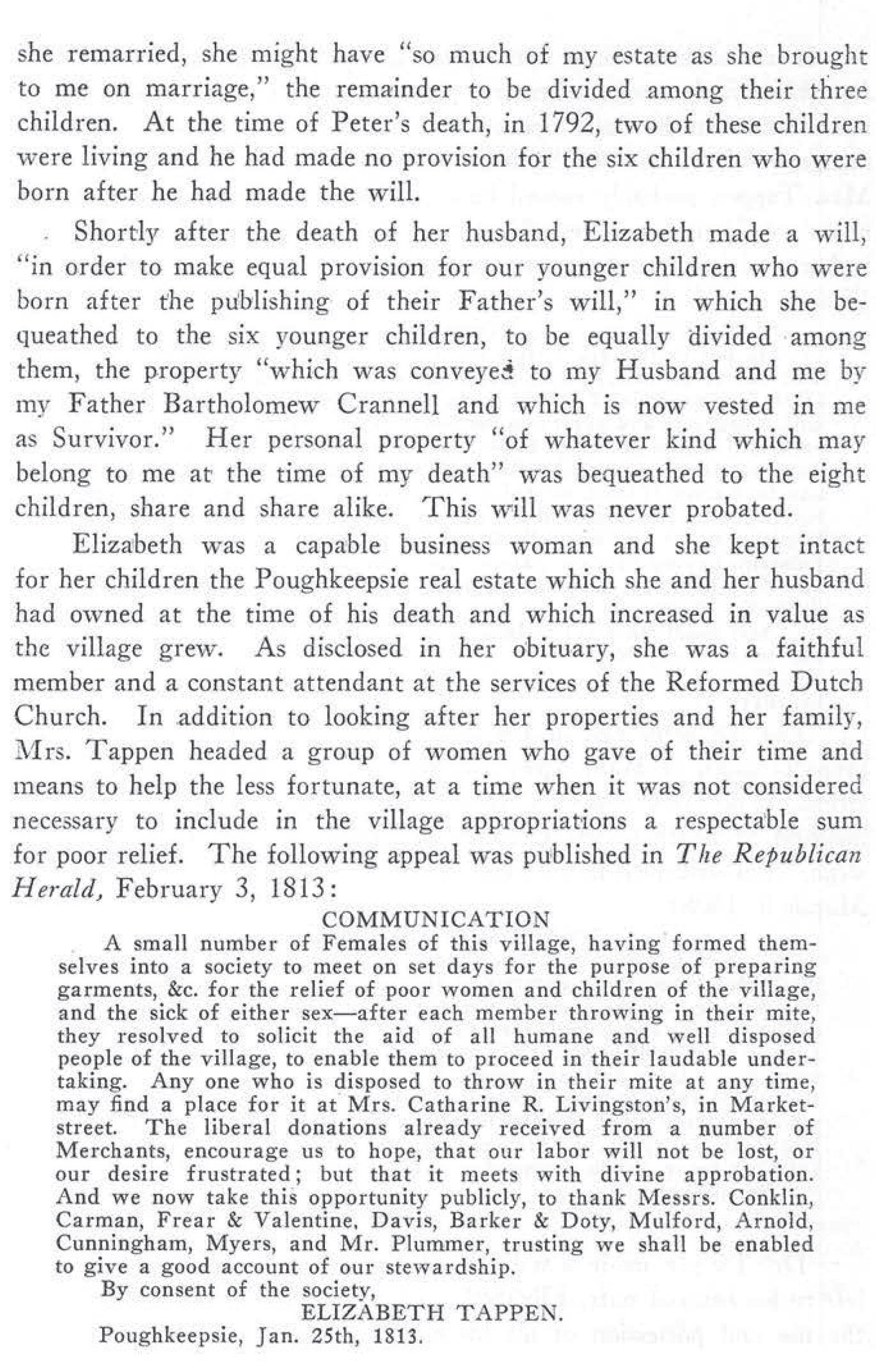

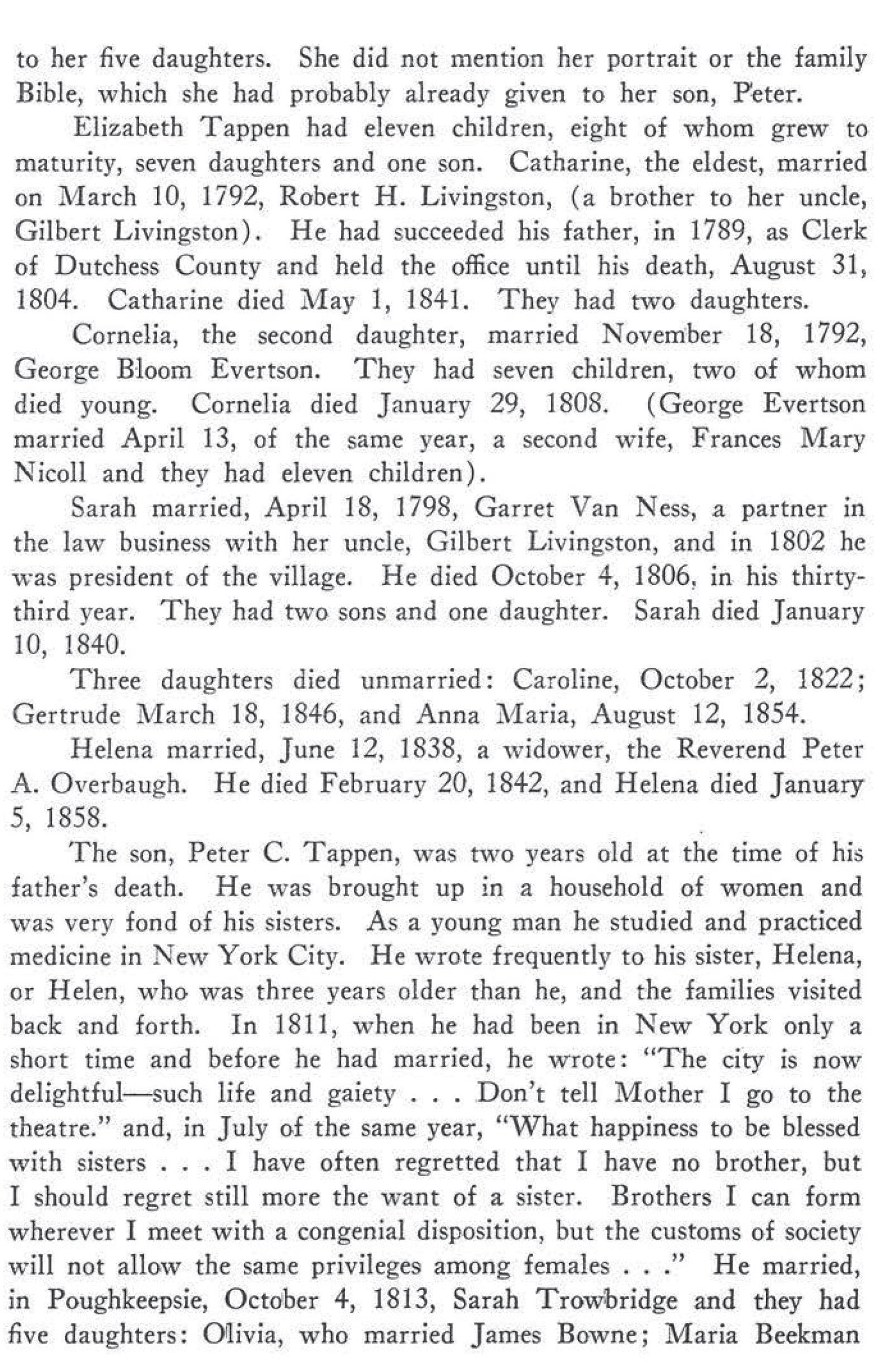

Elizabeth Crannell, Wife of Dr. Peter Tappen 202 by Amy Ver Noy

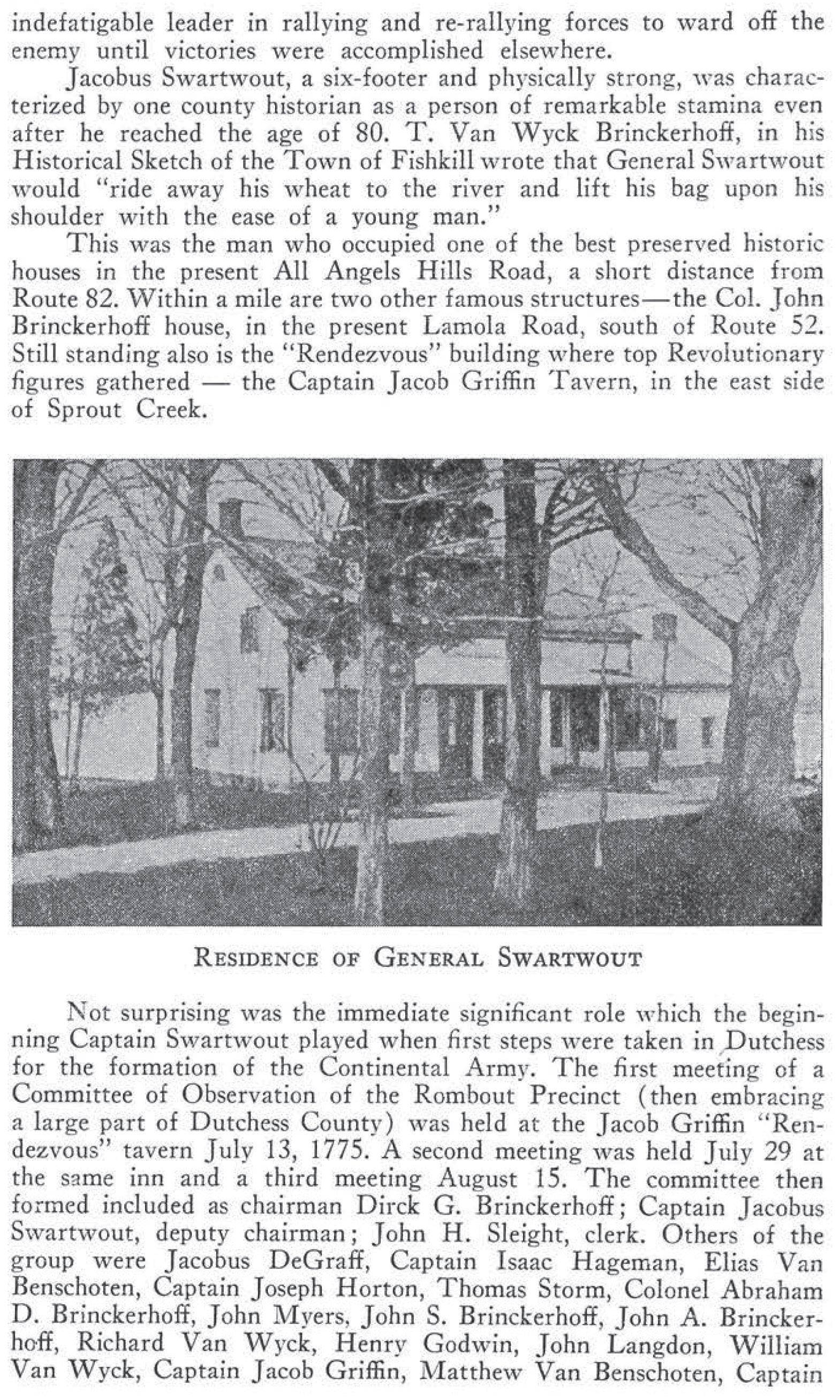

Jacobus Swartwout: Resident of Rombout Precinct 227 by Joseph W. Emsley

Sybil Ludington: Heroine of the Revolution 233 by Louanna J. Elya

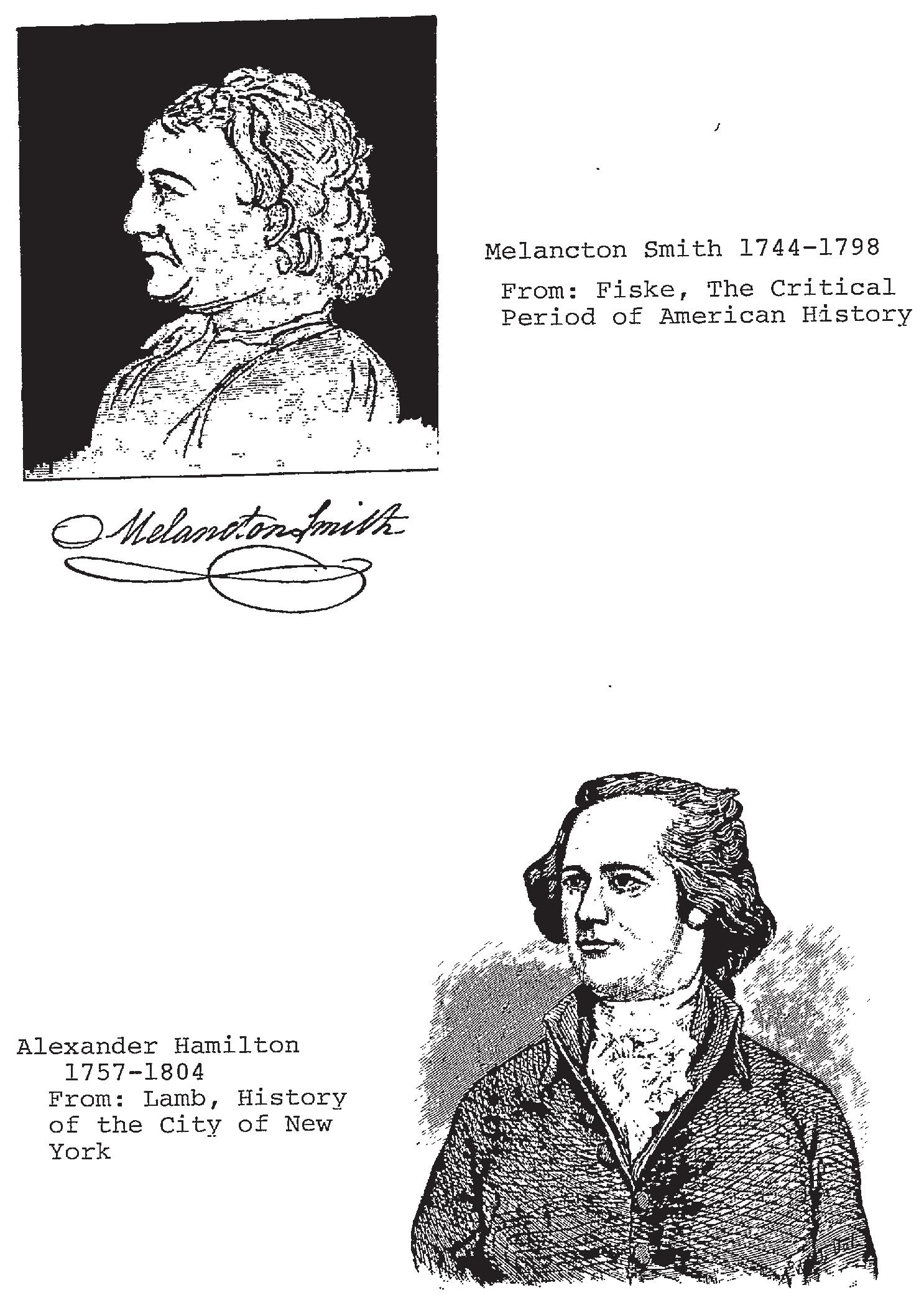

Alexander Hamilton, Melancton Smith, and the Ratification of the Constitution in Poughkeepsie, New York 241 by Robin Brooks

Profiles of the American Revolution Since 1914.

We are pleased to announce the third Encore Edition of the Dutchess County Historical Society Yearbook. Published since DCHS’s founding in 1914, the Yearbook is New York State’s longest-serving historical journal. Known for its thorough research and interesting narratives, the DCHS Yearbook is meant to be more broadly accessible than an academic journal, although contemporary issues are footnoted for accuracy and to help prompt further inquiry.

In addition to the annual publications, DCHS has started publishing Yearbook Encore Editions, which republish articles bundled around a single topic. They are republished with no changes to simply and directly reflect the priorities, perspectives, and language of a certain time.

Profiles of the American Revolution Since 1914 helps us better understand how the people of Dutchess County both shaped and were shaped by the American Revolution as we approach the 250th anniversary of the official signing of the Declaration of Independence.

After reviewing the 14,000 pages of DCHS’s Yearbook, DCHS’s Collections Manager, Aidan Chisamore, has curated a volume that focuses on biographies.

As you would expect, the DCHS 2025 annual Yearbook on the same topic as well as all the “Rev250” programs and articles we are now involved in, offer a broader, more inclusive, or whole history. We hear voices beyond just a single voice that inspired the phrase, “the victor writes the history.” We can learn from the voices of the defeated. We

can learn from those whose victory in achieving the radical, aspirational promise of the 1776 United States was achieved later than others. Slavery was abolished nationally with a guarantee of equality in 1870. Women earned the right to vote nationally in 1920.

This is the third in the series of Encore Editions; the first two relating to Black History and The Hudson River & Year-round Sport. We plan on publishing a fourth Encore Edition: Part 2 of the Revolutionary War, for 2027.

This publication is funded, in part, from a generous grant from Dutchess County government.

Bill

Jeffway & Melodye Moore

William P. Tatum III, Ph.D. Dutchess County Historian

“The romantic and colorful story of the exiles in New Brunswick, of their work in the forest as pioneers and of their founding of the permanent community of the city of St. John, is almost unknown today in the United States, an ignorance which is traceable to the fires of passion and of prejudice that burned long and fiercely after the Revolution, to the vulgar ‘twisting of the lion’s tail’ in the nineteenth century, and to a lack of accurate knowledge of the fundamental position of the Loyalists. Cheap oratory will, perhaps, always be plentiful on July Fourth and similar occasions but there are many intelligent citizens of the United States who must, by now, have outgrown traditionalism and who must be ready to study facts and by facts to form opinions.”

Helen Wilkinson Reynolds, 1922

From over a century ago, the words of Dutchess County’s foremost historian still ring true and vibrant today. We now find ourselves within the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution, on the cusp of the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence that founded the United States of America. It is necessary once again to heed the words of Helen Wilkinson Reynolds to look back to facts to form new opinions about the birth of our nation and the impact of the Revolution upon the subsequent 250 years of our lived experience. The article from which the above quote is drawn, “Bartholomew Crannell: A Twentieth Century Plea for Anglo-American Good Will,” still incapsulates the state of our knowledge regarding one of Dutchess County’s foremost Loyalists. The absence of scholarly progress on that topic and many others indicates both the strength of our predecessors’ work

and the great amount of research and writing that still needs to be done to uncover the stories of the Revolution in Dutchess County, along with the many ways in which it has shaped subsequent events and continues to impact us today.

A key component of the practice of history is historiography: the record of how previous historians have investigated peoples, places, and events of interest in the past. Historiography is a nod to the old caution against reinventing the wheel. Considering how much time and effort usually goes into producing well-researched pieces, it is generally far more effective to begin with reading what has already been written on a topic rather than seeking out primary sources from the period in question first. Reviewing previously published scholarship provides insights into the questions that have been asked, the dead ends that have been encountered, and the ways in which shifting priorities in the present have impacted various generations’ views of the same past that faces us today. For while the events of 1775 are immutable, our understanding of what happened and why it is important to the present is not. Through research and publication, each new era of historians seeks answers or reflections of the burning questions of their present within the surviving fragmentary records of our shared past.

That desire to locate the best existing scholarship and make it available under one cover is what drives this special encore edition of the Dutchess County Historical Society Yearbook. Since the Society’s formation in 1914, its annual publication has presented the very best research-based investigations of Dutchess County’s past to generations of readers. The volumes of the Yearbook are collectively encyclopedic in size, making a systemic review of their contents by modern readers a lengthy undertaking. This volume simultaneously conducts that work for the reader while also providing immediate answers to one of the more burning questions regarding the Revolution in Dutchess: who were the most important residents at the time and what did they do? While the articles contained herein do not provide the be-all, end-all answer to that question, the scholarship does provide vital information on many important figures and calls upon modern historians to seek

out still others. For every Bartholomew Crannell who has received a historian’s treatment, there is a Beverly Robinson, who has not.

The Dutchess County in which Bartholomew Crannell, Zepheniah Platt, Elizabeth Crannell Tappen, and the other individuals covered in this volume lived was a markedly different place from today. Prior to the division of 1812, Dutchess included all of what is now modern Putnam County and a small slice of what is today the Town of Clermont in Columbia County, specifically the Livingston home of that same name. One of the original twelve counties of New York established on November 1, 1683, Dutchess was the least settled by the coming of the American Revolution. That situation was in large part due to the nature of colonization: the expansion of the English form of land title, legally required for permanent European settlement, began with the purchase of massive lots called land patents. The patentees, effectively land speculators based in Manhattan, went through an extensive process beginning with purchased land from indigenous representatives and concluding with the issuing of letters patent from the Crown, granting control of the land to the patentees. However, permission to subdivide these patents into sellable or rentable lots was an entirely separate process. Thus the Rombout Patent, officially granted in 1685, took until the 1720s to effectively partition. As a result, European settlement in Dutchess was a slow affair, only reaching critical mass by mid-century. As late as 1769 in a letter to relatives in Kingston, Peter DeWitt of Staatsburgh described Dutchess as a “poor county.”1

In contrast to many of the other Hudson Valley counties in 1775, Dutchess was a demographically diverse place. The relative lateness of European settlement combined with the geography of Dutchess County to create a patchwork of ethnicities and creeds across Dutchess County, particularly between the western and eastern halves. Along the Hudson River fringe, English and Dutch families dominated, with the Scottish-descended Livingstons (both of Livingston Manor and a

1 Peter De Witt to Charles De Witt, Witts Mount, February 1769, published in Marius Schoonmaker, The History of Kingston, New York, From its early settlement to the year 1820, Higginson Book Company, 1888, pg 154

cadet branch based in Poughkeepsie) dominating the political scene. These were the colonists who held actual title to the land, filled local civil offices, and led the militia in times of military need. English and Dutch names are also found within the lists of tenants, many of whom leased sufficient amounts of land to qualify for taxes, in southwestern Dutchess. In northern Dutchess, the title holders were largely Dutch and many of the homes were of Dutch style, but the mercantile and farming classes predominantly reflected German names. These Germans were either descendants of the Palatines who migrated to Livingston Manor at the beginning of the eighteenth century or cousins who joined and expanded settlements in Rhinebeck, Red Hook, Milan, Pine Plains, North East, and down the eastern Dutchess verge in the subsequent decades. Eastern Dutchess, with the Taconic Range serving as the dividing line, witnessed an influx of New England families from the second decade of the eighteenth century, along with many Quakers seeking freedom of religion beyond the prying eyes of colonial authorities. Much work remains to be done on the indigenous groups that continued to call Dutchess County home, and both the free and enslaved people of African descent who came to Dutchess. Religious faiths were nearly as diverse as the national origins of the residents, with Dutch Reformed and German Lutheran dominating alongside the state religion of the Church of England. Yet Quakers, Baptists, Presbyterians, and other protestant groups were present throughout the county. The names of the residents featured in this volume speak to that ethnic and cultural diversity.

The world into which these residents were born or brought consisted of markedly different landscapes and sets of life experiences from the present day, as should be evident from much of the biographical data provided in the accompanying articles. The local economy was dominated nearly to the point of exclusivity by agriculture, with wheat being the cash crop. Cultivation of sheep for wool was present, though still a mere cottage industry in scale, as was the production of manufactured goods, including agricultural implements hammered out at the Harris Scythe Works in modern Pine Plains. While cattle were present across much of the less-arable landscape, the herds were

x

raised for meat rather than the milk of later centuries. Dutchess County occupied an enviable position vis-à-vis markets in Manhattan: just far away to raise fat cattle with relative ease but close enough to drive the beef to market without losing too much weight in the process. Stores existed throughout the county, so that every quarter of Dutchess was connected with the global British imperial economy. Even in landlocked eastern verges of Charlotte Precinct, which covered the modern towns of Washington and Stanford among others, residents had access to English manufactured goods and textiles, spices from Asia, and rum and sugar from the Caribbean. Nevertheless, Dutchess was a land of relative financial extremes. As the riots over rents in the 1760s demonstrated, the tenant economy and settlement model created a problematic class division between a majority population of small farmers and a minority of large landlords, with a nascent professional class of lawyers, doctors, and skilled tradesmen in between. Insights into the experiences of the county’s population before and during the Revolution can be found in the articles on Bartholomew Crannell, Dr. Peter Tappen, and Elizabeth Crannell Tappen.

Dutchess was also divided politically and governmentally. In 1775, the county was politically divided into precincts rather than the towns of the modern day. These precincts were geographically large, often containing widely dispersed populations, the echoes of which are still felt in today’s historic hamlets. Each precinct featured its own governmental staff, led by a supervisor (as the towns still are today) and including tax assessors, tax collectors, overseers of the highways and fences, overseers of the poor (social welfare), and justices of the peace (town judges). Poughkeepsie was, as it still is today, the county seat and site of the county courthouse, five of which have stood on the same corner of Market and Main Streets since 1721. The Courts of Common Pleas (civil) and General Sessions (criminal) that met at least twice per year at the courthouse effectively governed the county, splitting up taxes to cover poor relief expenses and settling disputes between the precincts. The precinct supervisors met annually, usually in October, to review financial claims against the county, but performed few additional tasks, in contrast to today’s county legislature. By 1775, most of

the offices of local government were held by men who would pledge their loyalty to the new State of New York. However, loyalty to the British crown still ran strong in Dutchess, with potentially as much as 30% of the adult male population adhering to the royally appointed governor. The pre-war tensions between renters and landlords added to political friction, occasionally boiling over into violence as New Yorkers first ejected British soldiers and Royal Governor William Tryon in the late spring of 1775, organized an army during the summer, and invaded Canada in the Fall. The article on Henry Livingston, the longest-serving Dutchess County Clerk, investigates the long view of the experience of government and governance from the colonial into the revolutionary era.

Despite being located within one of the battleground states of the Revolution, Dutchess County saw no major pitched battles within its territory. Yet the county and its residents played an enormous role in the conduct of the Revolutionary War. Located sufficiently far away from British-occupied New York City, Dutchess served as a major supply and logistics hub. Local farmers provided large quantities of produce and materials to feed and equip the Continental Army, stores that were routed through the Fishkill Supply Depot. After the British expeditionary force under General John Vaughan burned Kingston in October 1777, Poughkeepsie became a default meeting place for the new state assembly and many war-related endeavors. The articles on Major Udny Hay, Zephaniah Platt, and Melanchthon Smith touch on these aspects of the Revolutionary experience. Dutchess County also supplied many officers and men to the Continental Army from 1775 onwards, participating heavily in the invasion of Canada in that year and the defense of New York City in 1776. Articles on Captain Israel Smith, Colonel Lewis DuBois and Captain Henry DeBois, and Major Elias Van Bunschoten, along with the dedication of the monument at Chambly in Quebec explore the Canadian Campaign. Articles on General Jacobus Swartout, Major Andrew Billings, Colon Frederick Weissenfels, and Colonel Henry Ludington cover the defense of New York City the following year and service throughout the remainder of the war. The extensive involvement of the Livingstons as army officers and political figures is explored in the multiple entries on that family

The pages to follow delve into the lives of many of the men, and a few of the women, who made major contributions to the Revolutionary cause in Dutchess County, and one who opposed it. There are insights into how an earlier generation of Dutchess County residents and historians memorialized the service and sacrifices of the Revolutionary generation in the article on monument to the unknown soldiers of the Quebec campaign and the ultimate sacrifice of Daniel Nimham and the indigenous patriots of Dutchess County. The presence of larger-than-life Revolutionary figures in Dutchess, including General Steuben, the German-born military instructor of the Continental Army, and Alexander Hamilton, along with their impact on local affairs is explored in two articles. Finally, the most controversial figure in Dutchess County’s Revolutionary Era history is explored in two articles: Sybil Ludington, the reputed female Paul Revere who warned of the British raid on Danbury, Connecticut, in 1777, the details of whose service are still a hot topic of debate among historians today. Together, these articles represent the best biographical pieces that the Dutchess County Historical Society has brought to publication over the last century, marking a vital starting point for future work.

From DCHS Collections

Signature of Bartholomew Crannell, ND From DCHS Collections

From DCHS Collections

From the New York Public Library

From the New York Public Library

From Yale University

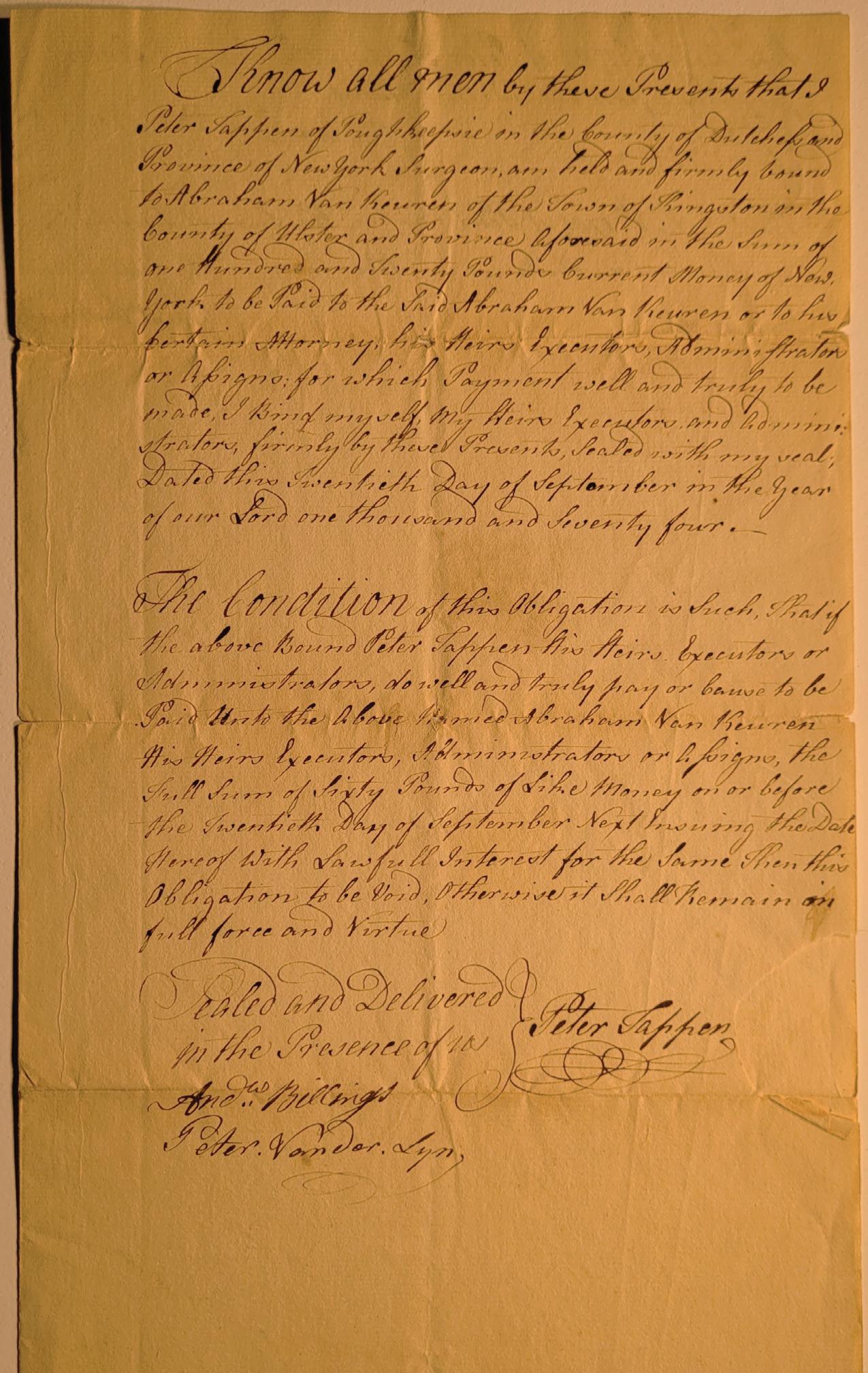

From DCHS Collections

From DCHS Collections

Military

From DCHS Collections

From

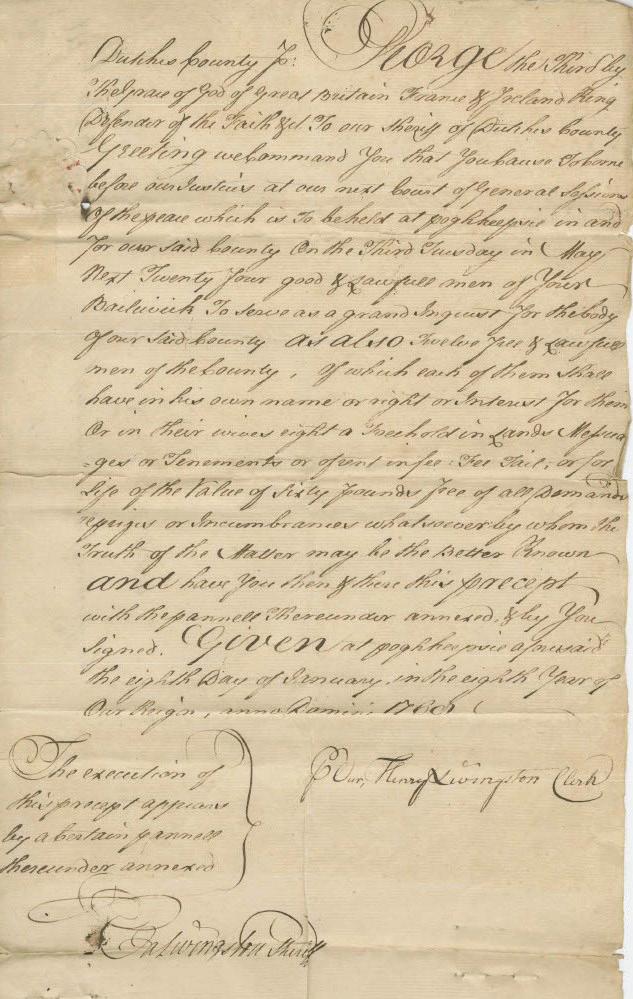

Call for Jurors, May 1768

James Livinston signature as sheriff From The County Clerk Ancient Document Search

From DCHS Collections

From Yale University Art Gallery

From DCHS Collections

Front cover image: A Chorographical Map of the Province of New-York in North America,”