turnsteenager 100

volume 1: the kids are alright, right?

volume 1: the kids are alright, right?

C o n t e n t s

I just getting started

- staff list p. 4

- high schools amplified p. 5

- foreword p. 6

- word from our editors p. 8

- word from our sponsor p. 10

- the locked door in the basement p. 12

II navigating the language of mental health

- misunderstood p. 14

- misusing labels p. 15

- 504/bipolar disorder p. 16

- OCD p. 17

- anxiety p. 19

- synethesia p. 20

III the quantifiable & not-so-quantifiable

- crisis by the numbers p. 22

- oft-overlooked p. 25

IV making the grade

-“teenager” becomes a thing p. 26

V features

- LGBTQ+ students & our support p. 29

- the cost of masking emotions p. 31

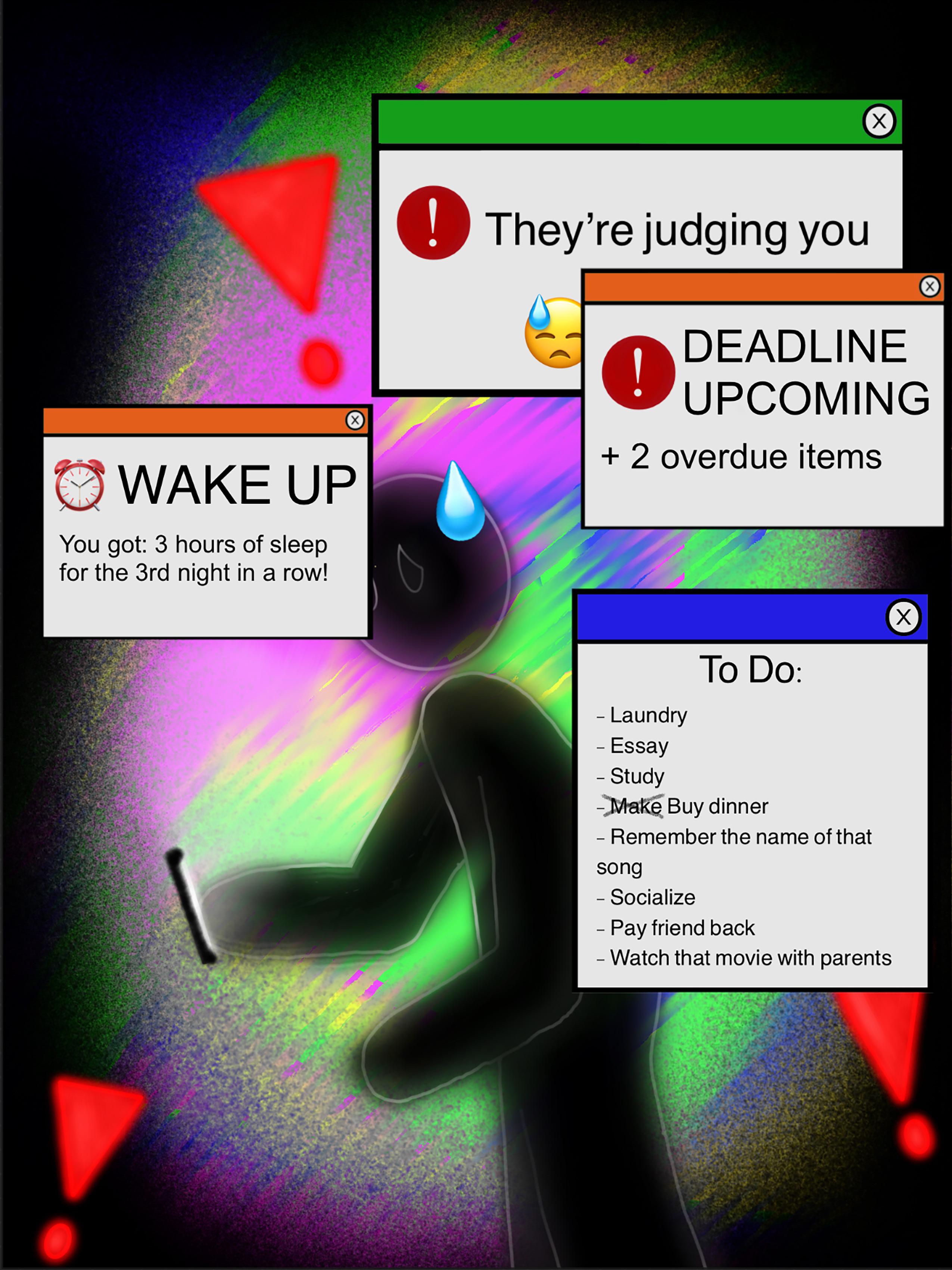

- broken functions p. 32

- a new dread p. 34

- rejecting who you are p. 39

- competitive illnesses p. 40

- around the world p. 43

VI the science fiction of teen mental health

- introduction p. 47

- the panopticon p. 49

- crushing on our oppression p. 53

- sheltered to death p. 56

- what reality are you living in? p. 58

- feeling grotesque p. 60

VII creative writing

- find sanctuary p. 62

- welcome p. 63

cover artists

Olivia Ensign (front cover) Amber Auth (inside front cover/left) and Daviana Marcus (back cover)

The Amplifie

Montgomer y County’s Student-led Magazine

‘22-’23 editors in chief

Bennett Galper

Gabe Gebrekristose

Isabella Kriedler

‘23-’24 editors in chief

Milan Bhayana

Michaela Boeder

Elizabeth Mehler

Auva Vaziri

art editors

Katherine Barnett

Carol Li

Riona Sheikh

art team

Helen Marie Besch

Daviana Marcus

Lizzie Varner

faculty advisor

David Lopilato

Special Thanks to

Sarah Harnish and Mygenet Harris

curatorial and editing team

Michael Demske

Indira Kar

Francesca Lisbino

Jaylen McCullogh

Colette Mrozek

Antonio Persi

Shelby Roth

Kaitlyn Schramm

Rachel Smith

(co-coordinators and instructors at The MCPS Visual Arts Center)

-

The MCPS Editorial Graphics and Publishing Services team

Representative Jamie RaskinJulia FriedmannRebecca Dillon

None of this would be possible without you.

To learn more about The Amplifier and join the movement, follow us on Instagram @mcps.theamplifier.

To order free print copies of our publications, visit

high schools amplified

Bethesda-Chevy Chase

Montgomery Blair

James Hubert Blake

Winston Churchill

Clarksburg

Damascus

Albert Einstein

Gaithersburg

Ivymount

Walter Johnson

Col. Zadok Magruder

Richard Montgomery

Northwest

Northwood

Paint Branch

Poolesville

Quince Orchard

Rockville

Seneca Valley

Wheaton

Walt Whitman

Thomas S Wootton

foreword

By U.S. Representative Jamie RaskinHow do we promote mental wellness in a world that often seems unsafe, unstable and unwell?

It’s a question of pressing importance to young people seeking peace of mind in the age of climate disaster, COVID-19, violent insurrection, random gun violence, unceasing culture war and online hate.

The precocious and intrepid young reporters, essayists and activists compiling this issue of The Amplifier have curated a brilliant array of individual and collective experiences to provide a powerful answer to this question: the way to promote mental wellness in this unforgiving world is through compassion, humor, honest self-reflection, and the daring expression of sadness and hope, trepidation and joy, loneliness and solidarity.

Young people today face, beyond all the crises unique to our times, the traditional complications of youth in America: heartache and identity crisis, the high cost of college, the vagaries of the immigration process, finding a pathway of integrity and hope in the world.

In the face of these challenges, our young people are surpassing all rightful expectations of resiliency— but they are not “all right” on any conventional metric.

The American Academy of Pediatrics declared the state of youth mental health to be a “national emergency” in 2021 because the pandemic’s hallmark isolation and

anxiety effects multiplied and exacerbated the already-high risk factors for young people.

The young people in these pages know that their personal mental health is shaped and buffeted by the sharp currents flowing in our society. Our LGBTQ+ students know when their humanity is under attack, as do Jewish students and students of color confronting the shocking resurgent waves of homophobia and transphobia, antisemitism and racism. Our students from mixed-status immigration backgrounds live every day with Congress’s refusal to pass comprehensive immigration reform. All students feel the weight of structural political dysfunction. They know when the so-called “adults in the room” are falling down on the job.

Meantime, the troubles of young people and their elders are splayed all over social media, which spreads not only hateful messages but the pressure to post perfect snapshots of perfect bodies. I introduced the CAMRA Act last year to direct the National Institutes of Health to research how social media and other technology are affecting young people’s health and development. I eagerly anticipate the results of this research. I also helped to launch the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline so that every American can call, text, or chat with a mental health professional if and when they are in crisis. This line has recently added more Spanish language services

and an option for connecting with counselors who are specifically trained to support LGBTQ+ youth and young adults. These policy successes mark real progress but do not, of course, fully address the significant and growing needs of our people.

For too long, our society has confined conversations about mental health to the shadows of private life. Until very recently, a person’s struggles with depression, anxiety or other forms of mental illness were compounded by powerful social stigma. People suffering from treatable conditions feared the consequences of sharing their experiences with others, even though social conditions are key to understanding and managing mental illness.

The young people of MCPS have curated a brilliant collection of art and narrative prose to crack open the traditional mold of social isolation, fear and silence. I hope you enjoy this impressive collection as much as I have, and learn from what the authors have bravely shared about their own experiences with mental health challenges.

As dim politicians seek to ban books and threatening ideas, the students of MCPS are creating a powerful message of hope based on free creative expression. I hope that you take the time to read these pages, to learn from these remarkable young people and to work with them for a healthier world.

Special note: Olivia Ensign’s “The Memory Quilt: Pieces of Myself” (featured on the front cover) won the 2023 Congressional Art Competition for Maryland’s 8th District.

art by Evdokia Brazhnikova

art by Evdokia Brazhnikova

the turnsteenager 100

a word from our editors

This volume is the first of a series, “The Teenager turns 100.”

The term teenager was coined in the early 1920s to categorize young people who were coming of age and the culture they created.

Stay tuned for our other editions on socializing, expression, sports and academics.

For Volume One, we hear from teens on teen mental health.

According to the February 2023 CDC’s Youth Risk Behaivor Survey, teenage sadness and hopelessness are on the rise across the board.

According to the study, forty two percent of students felt so sad or hopeless that they could not participate in their usual activities (from studies to sports) for two weeks or more.

The pandemic is certainly a big part of the story. There was an eleven-point jump in the percentage of girls feeling sad and hopeless in the first two years of the pandemic.

But the pandemic is not the whole story. There was a ten-percentage point increase in the ten years before the pandemic.

Social media, adults’ favorite boogeyman, is not the whole story.

Today, students have to worry about much more than their academic performance. They also must

craft the perfect resume of extracurriculars for increasingly competitive college admissions. And, tragically, too many student need to do all this in dysfunctional and unsafe educational environments.

Outside of school, there’s the ever-present anxiety about climate change, growing economic inequality, and lack of opportunity for anyone who can’t pay tens of thousands of dollars for a college education.

Today’s teens are more socially isolated than ever. Their few moments of rest from their overloaded schedules are occupied by big tech corporations who turn attention into profit through social media.

None of this is to mention the usual issues teens face in high school, including drug and alcohol use, bullying, and problems with eating disorders and self-esteem.

So why are teenagers struggling with their mental health more now than ever before in history?

As this magazine can attest to, there is no singular answer to that question. Rather, by including a variety of student perspectives, we hope to explore these different factors that contribute to mental health.

In the following pages, you’ll find firsthand accounts of what it’s like

to be in a psychiatric hospital, an investigation of why teens today are more cynical than ever. You’ll learn about how mental health affects LGBT teens, learn why men’s mental health is overlooked, and understand the beauty of synesthesia.

You will read about the necessity of increased accessibility in accommodation plans for struggling students and a firsthand perspective of how social media factors into the equation.

We hope you come away from your reading with a broader perspective of how mental health affects teenagers and a greater empathy for the young people who are dealing with these issues. If you’re a teenager yourself, we hope you feel seen in these pages. Above all, we hope you’re inspired to share your own story.

As a county-wide publication, we hope to amplify the voices of students who don’t have access to a publication and to unite high school students from diverse backgrounds under shared issues that affect us all.

- The Amplifier Editorial StaffThe writers and artists featured in this magazine address emotionally-difficult topics, including suicide. If you’re thinking about suicide, are worried about a friend or loved one, or would like emotional support, call the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline (available 24/7 across the United States).

self portraits

and now, a word from our sponsor

Iamdeeply troubled by the recent report by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) on teen mental health. After all, I am not only President of United States Teenager (UST); I am the proud father to two beautiful and gifted teenage girls.

When Great Gramps, age-grade pioneer Theodore “Teddy” Hughes, drew up identity designs (ID’s) for “the teenager” back in the early 1920’s, he could not, in his wildest dreams, have imagined the impact the American teenager would have on the world.

He also could not have imagined the impact the weight of the world would have on teenagers.

Let me be clear, the “storm and stress” of American adolescence is older than Great Gramps’ earliest sketches.

In fact, Great Gramps set out, in his original design, to give teenagers a degree of agency to deal with “their agonies.”

Even back then, he realized that identity was more than a label. It could provide a power to navigate, even possibly liberate.

The design was not perfect. Which design is?

But, let us not forget that things were not paradise when children transitioned directly into adulthood- thirteen year olds worked in factories, fought in wars, and girdered themselves for marriage.

In contrast, “the teenager” was nothing short of a triumph.

Of course, the storm and stress of adolescence persists today and will continue to persist when today’s teens are tomorrow’s senior citizens.

We at UST know there is no one cause of the decline in teen mental health and no one cure. But, we also firmly believe that we are obliged (in fact, called) to listen to teenagers just as we have done for the past

100 years.

That is why UST is proud to be a sponsor of the Amplifier’s four-part series: The Teenager@100.

While the so-called experts ruminate, let’s let the teens themselves illuminate.

Sincerely,

Theodore Hughes IV President United States TeenagerHappy Birthday American Teens --100 years young

If you need to find Hube on a Friday night, you will have more luck looking in one of Columbia’s many science labs than in one of Manhattan’s many watering holes. Our resident Charles Darwin adores everything science. He has even dabbled in the exciting young field of Eugenics. Thanks to a prestigious scholarship which we cannot pronounce or spell (and, yes, we are too lazy to figure out how), Hube is headed back to Berlin after graduation to help his native Germany back on its feet. Hopefully, no hard feelings, freund.

Fraternity: Phi Delta Theta

Insignia: Kings Crown Third Class Jester (1) Cribbage (3) Track (1) Glee Club (3)

His closest chums call him “Teddy Triangle” because he always has a few angles and “never more than one of them right.”

Teddy is a first-rate Anthropologist, Yet, he is an entrepreneur at heart. He has an eagle eye for the next big thing and with war behind us and smooth sailing as far as the eye can see, there are plenty of next big things for Teddy to spot on the horizon.

Attention Ladies, tie yourself to Teddy’s mast. He is going places.

self portraits

the locked door in the basement

by Caitlin Mayhugh art by Lily PacuitAcouple of months ago, I was enrolled in an inpatient adolescent behavioral health clinic. As the name suggests, the program took place entirely in the hospital.

Patients were not allowed to leave. Every week, we would have a session of family therapy which would then be followed up by a daily family visit.

Ironically, my first session was about communication and I remember virtually none of it. All I remember was the look on my parents’ faces as they watched me, unable to muster a response. Their eyes were red and puffy, making me feel guilty. If I had just been a “normal” kid, they wouldn’t have had to be in that room with me.

At our initial family visit, an argument broke out. Yet again, I can’t quite remember why. All I remember is a fight and storming out of the room sobbing.

Eventually, I ended up in “the quiet room,” a sterile little box of a room, just off of the common area. It was meant to be a therapeutic space but most of the time patients just used it to cry. The chairs were hard, the temperature was always a degree too cold, and the lights were blindingly bright.

One saving grace was the glazed windows which spared you the embarrassment of crying in front of the other kids. Nurses came in and out of the room, hovering over me and interrogating me. I remained completely nonverbal, shamefully holding my hands over my eyes like a dam for my tears.

The door opened again, but this time a much warmer face emerged. It was Nurse Hakim, my chess partner and fellow artist whom I had already confided in about a plethora of things. Religion, philosophy, drawing, writing, living with depression. Nothing was off the table

with him. We went back and forth for a little while, and I gradually recomposed myself to meet his calm tone. He opened up to me about his personal experiences with his mom. Finding out that we both had similar relationships with our mothers gave me a sense of comfort and mutual understanding. To comfort me, Nurse Hakim told me about his epiphany from earlier in his life:

“Death is like a locked door in your basement. Everyone has one, yet no one knows what's behind it. People are scared of the door in the basement. They’ve heard rumors about it sucking people in and never spitting them back out. But sometimes, something draws us to it, impulsive thoughts, an imposing world, or traumas that are out of our control, and we open the door. We see a darkness inside, an alluring yet forbidden comfort. It’s quiet, no one's there to bother you, not even your inner voice. But if you enter, the door will shut behind you, robbing you of your future and all those who love you.

“When we enter through this door we trade our lives for silence, for an eternal break from a tumultuous world. But in the act, we forget the opportunities each new day brings. People who survive their suicide attempts often report a feeling of overwhelming regret as soon as they realize the finality of their choice. We idealize death when we feel we have no other option, only to find its embrace deceitful and irreversible after taking the plunge.”

As these words poured into my ears, I savored each one like bites of chocolate cake. Until then, no one could explain what I saw in death, not even myself. For the first time in months, I felt sympathy for myself. I forgave my suicidality for what it was: a response to the pain of my stolen childhood. Every time

I acted on my intrusive thoughts, I blamed myself. I cut myself off from my friends because I was unworthy of love, I was self-harming because I couldn’t handle my flashbacks, and I would starve myself because I was “fat.”

But now, I understand that my mental illnesses were driving my actions. My depression told me I was not good enough, my trauma told me I was undeserving of love, and my anxiety told me it could never get better. Was it ever really my fault I wanted to die? Why should I be mad at myself for my suicidality? Wasn’t it me who confessed to my therapist when I began to plan my suicide? Wasn’t it me who asked my mom for therapy in the first place? I’ve always wanted help, it was never my fault I wanted to die.

Roughly a week later, I was allowed to go home. The doctors felt I had improved enough and I was no longer at high risk. But Hakim’s words always stuck with me, glued in my mind. I wanted to run, far, far away from that locked door. The same door whose knob I had nearly turned only weeks earlier.

I wanted to see another year, to continue making my art and celebrate the joy my friends and family bring me.

It’s not easy, of course, my intrusive thoughts will never go away, and of course, I will never be “normal.” But only now do I have the courage to stand tall amongst the torrent of challenges life has thrown my way. Nurse Hakim was a mentor to me, and although I miss talking to him, I’m glad I even had the chance. I don’t want to think about where I would be now if I hadn’t. I’m glad that the weight is gone from my shoulders, and that I have the fire to keep going. I’m glad that I can wholeheartedly say: I want to be alive.

by Angie Jurado

art by Rachel Torres Alvarado

by Angie Jurado

art by Rachel Torres Alvarado

Mental health is a reality that has always existed, but one that hasn’t always been considered important by society. In the past, discussion of mental health was often considered a taboo, and mental health struggles were kept in the shadows.

However, over the past few decades, mental health struggles have gained more support, finally being brought into the spotlight. Although there are still many ways for

us all to improve our ideas about mental health today, we are on our way to creating a safer and more accepting society for everyone around the world.

Social media has played a critical role in fueling the discussion of mental health these past few years. Many teens feel comfortable sharing and discussing their mental health struggles on social media because of the accepting online community. Knowing there are other

teens out there who are struggling or have struggled with the same things as them can serve as an enormous comfort and a reassurance to those who feel alone.

Oftentimes, teens keep their struggles to themselves to avoid having to be honest with themselves, or to admit that they need help. In other cases, teens trap their struggles within themselves because they don't feel comfortable talking to their parents about their difficulties. Some teens don’t have any adult they feel comfortable and safe enough to share their struggles with.

Many adults didn’t have the opportunity to grow up in a time where mental health wasn't a taboo. A lot of them grew up being drilled with the idea that mental health was “a punishment from God,” and that those who struggled with mental health were an embarrassment to others. For centuries, mentally ill patients were excluded from society for being a humiliation.

Mental health disorders were not recognized as treatable conditions. Growing up with this type of stigma around mental health wasn't beneficial for anyone. It discriminated against those struggling with their mental health, making them feel unwanted and out of place. Furthermore, it instilled a negative mindset and attitude toward mental health as a norm within our society.

Our parents and other adults may not have been raised to realize that mental health is such an important and serious issue, which is why they might brush things off or not take into consideration how important mental issues truly are, and how they affect us and the adults we will become. But our generation is working to fix the mistakes of the past. We are progressing to create a society that is more attentive towards making sure everyone gets the help they need.

P.S.A.

do not use mental disorders as trendy buzzwords

by Indira KarIwassitting in my English class one day when I heard a group of girls talking very loudly. Their conversation caught my attention when someone said they dyed their hair because they were feeling “bipolar.”

If I recall correctly, my crippling manic-depressive cycles don't result in new hair. They result in not sleeping for 6 days, making life-changing decisions on impulse, and ruining relationships by accident. When did we start using mental health terms so casually?

Social media movements have opened the door to conversations about mental health. The fact that people can now casually talk about feeling depressed or anxious is huge progress.

Being able to express your feelings to a friend is something that was looked down upon not 20 years ago. But, those feelings are not synonymous with having actual mental

disorders.

Have you ever heard someone who was just broken up with or had a bad day say they are “so depressed”? Or maybe you watched someone cleaning up and they claimed they are “OCD.”

I’ve heard people say they have anxiety because they are nervous about a test or have to go to SAT prep. These emotions are very real to those who are dealing with them. I’m not taking away from the validity of that, but they are not mental disorders.

People need to realize just how hard it is to live with mental illness.

Having depression isn't sometimes feeling sad, it's staying in bed all day because you physically can't bring yourself to move. It's crying to yourself some nights while spending other nights wishing you could cry.

It’s wanting to do something but

not being able to because you have no motivation. It’s not washing your hair for three weeks. Casually saying “I’m depressed” when you are feeling down takes away the value from those who are struggling with depression. The same can be said for any other disorder. No one would say that they had cancer because they were feeling physically unwell for a couple of days.

It is worth noting that it is incredibly time-consuming and expensive to get diagnosed with a mental disorder.

If reaching out to your parents is not an option or does not help, reach out to other people in your life, especially trusted adults. The counseling department is more than happy to hear you out, and there are online resources to inform you about different conditions.

art by Indira Kar504: bipolar disorder

by Indira KarThe504 plan was created to assist students with disabilities identified under the law and ensure their academic success, meaning a student with a diagnosed disability or mental illness can have accommodations. But what about the students who are struggling with their mental health without a diagnosis?

504 plans aim to help students who cannot keep up with the curriculum by providing additional support. A variety of options are available based on the individual’s needs. For instance, those with anxiety can receive a flash pass that allows them to show the teacher a slip and go straight to counseling.

However, there is a multitude of students without a diagnosed anxiety disorder who must deal with things like panic attacks by themselves.

Before I was diagnosed, I would go to the bathroom and suffer in isolation. Now, I have a space to calm down, and can even speak to a counselor if I so choose.

Anxiety disorders make school especially difficult for students. I recall stuttering my way through a Spanish presentation and afterward going to the bathroom and crying because I hated it that much.

If I had a 504 at the time, or even an understanding teacher, that could have been avoided.

Mental health also plays a huge role in test taking. It’s entirely common to blank out during a math test that you studied hard for when you’re dealing with test anxiety. With some 504s, students can have additional time and private work space, which allows them to have

better focus and more time to analyze and finish their tests on time, rather than rushing through.

“Before getting a 504, whenever I would go to teachers for extra time on assignments, they would just assume I was lying about struggling with my mental health,” says Blake senior Victoria Caplan. “Making these plans more accessible can help students who aren’t willing to defend themselves in these situations due to anxiety.”

Before I got diagnosed with bipolar disorder, I would just deal with the highs and lows of mania and have no idea what was going on. Many parents, minorities in particular, are less likely to believe in mental illness, let alone admit that their child might have one. My parents just thought I was crazy. Getting diagnosed with a mental illness is not only incredibly expensive but incredibly time-consuming. A psychologist first has to meet with you to discuss your symptoms, then friends and family members must confirm what you say. This is a very long back-and-forth process. Those with higher-income parents are more likely to be diagnosed and therefore have higher access to accommodations.

504 plans fall under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, later followed up by the Americans with Disabilities Act. There are county-wide rules that MCPS is required to follow, so it makes sense that these plans are selective. However, before receiving my 504, I was given “informal accommodations.” These included extended time on work and a flash pass to counseling.

Even though I didn’t officially have a 504 yet, I still had access to the help I needed.

If students could have an interview with their counselor at the beginning of the year to discuss their individual needs, then this issue could be solved. While most teachers are fairly understanding about mental health in school, there are always those who refuse to give extensions or allow a trip to counseling. Oftentimes, this may lead to teenagers going to mental health facilities and psych wards before they get diagnosed with a mental illness.

Even a Google Form rating how well you’re able to accomplish tasks in school could be beneficial. Ideally, it could list several examples of how anxiety can impact the school. For instance, a student could check off “I forgot what I learned while taking a test” or “I face high levels of anxiety when test taking.” And yes, people may abuse these forms, but teachers can confirm whether or not the student is being honest based on test scores and class work completion.

It’s ridiculous not to give struggling students some extra time on assignments just because they don’t have a diagnosis. The conversation surrounding mental health in this country has just begun, especially with our upcoming generations who have been advocating for their struggles. There are so many changes that can easily be made to help students in difficult times. Almost nothing stands in the way of making these small changes that add up to progress for us all.

People claim that obsessive-compulsive disorder, usually referred to as OCD, does nothing more than make someone organized and neat. Phrases like “I’m so OCD” or “I’m a little OCD” only reinforce the stereotypes that OCD revolves around cleanliness, and can be offensive and harmful to individuals with the disorder.

In reality, OCD can be different for everyone, but no matter what, it is severe and affects people’s lifestyle in a multitude of ways.

Individuals with OCD could have obsessions, compulsions, or both. Obsessions are intrusive thoughts that come up again and again.

People with obsessions can have “taboo” thoughts around things like sex, religion, or violence that could lead to anxiety and possibly selfharm. Compulsions are repeated behaviors that a person feels they keep having to do.

Everyone checks things once or twice, but people with compulsions check things a large number of times. The person does not gain pleasure or satisfaction by acting out their compulsions, but they cannot control their actions and bring themselves to stop.

The causes of OCD are not completely understood. Some scientists theorize that OCD could be due to genetics or abnormalities in the brain. Compulsions could be learned over time, making it even harder for a person to leave the cycle of repeating actions.

One to three percent of children and teens have OCD.

Having OCD on top of all the natural stress of teenage life can make someone’s life much more difficult.

For me, obsessive-compulsive

disorder has impacted my daily life in small but influential ways.

My compulsions include rereading things a ridiculous number of times even when I understand, tugging on my shirt, pushing on my glasses, and tapping my foot on the ground.

Seeing a psychiatrist helped me and my regular doctor better understand my case of OCD.

Most people with OCD know that their obsessions and compulsions are irrational, but they feel powerless to stop them. Others believe OCD protects them against threats they believe are very real and dangerous.

The stereotypical connection be-

tween OCD and cleanliness most likely comes from the very real compulsion of hand washing. Hand washing is normal, but some people with OCD wash their hands over and over again. Excessive hand washing can result in raw and broken skin and can be a hindrance to living a normal life.

A disorder that could result in physical harm and cycles of dissatisfaction cannot be labeled as “having a thing about cleanliness.” Teenagers can do their part to help people with OCD by combating stereotypes surrounding the disorder and spreading awareness about this serious topic.

anxiety: it’s academic

by Anne CervenyAnxiety has become more common in recent years. One in every eight children has anxiety, according to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA). But what is anxiety, and what are its effects on high school students, their well-being, and their academic performance?

Although a moderate level of anxiety is beneficial due to its ability to increase motivation to do things, too much anxiety can “[interfere] with concentration and memory, which are critical for academic success” (Understanding Academic Anxiety – Learning Strategies Center).

What is anxiety? Anxiety is essentially your “fight or flight” response. It’s your body’s way to warn you of danger (in cases of anxiety disorder, that danger might not even be there).

This can cause “an increase in adrenaline (causing your heart to beat faster) and a decrease in dopamine (a brain chemical that helps to block pain)” (Understanding Academic Anxiety – Learning Strategies Center).

While this response is critical to genuinely dangerous situations where you would need these changes to understand the danger and figure out how to avoid or fight it, individuals with anxiety disorders often get these reactions to dangers that aren’t dangers at all, such as irrational phobias, academic stress, emotional stress, social stress, and more.

So if anxiety is just a fight-orflight response, doesn’t everyone have anxiety? Yes and no. Everyone may have a moderate amount

of anxiety in stressful situations, but the difference between feeling anxious and having an anxiety disorder is colossal. Individuals who experience feeling anxious may feel tense, be in a bad mood, avoid an issue, and/or become emotional for a short period before composing themselves and dealing with the issue.

However, individuals with anxiety disorders find it much more difficult to compose themselves and deal with the issue. This can reach the point of a panic attack.

While different people may experience different extremes of panic attacks, the majority of panic attacks include hyperventilating, rapid heart beating, and lightheadedness which can change depending on different situations.

Anxiety disorders are especially difficult and inconvenient for students. Studies have shown that “students who reported that stress affected their performance had lower GPAs, and reported more stress and lower coping self-efficacy, resilience, and social support” (Frazier et al.).

These low grades and low GPAs are due to the effect that anxiety has on student’s ability to take in information, process information, and store/consolidate information in their long-term memories.

This can vary from day to day as well. For example, a student with anxiety may be performing well in a class one day but then performing very poorly the next.

It doesn’t stop there. Students with anxiety may also have a “lack of engagement in the classroom, poor relationships with peers and

teachers, and disinterest in pursuing passions and planning for the future” (IBCCES). It’s no surprise that anxiety can also create a “school phobia” in students if their anxiety gets severe enough.

As someone with anxiety, I can relate to almost everything mentioned in this article. My anxiety has become less severe over time but I could never forget how bad it used to be.

My panic attacks constantly varied and seemed to pick symptoms from a list: weak/numb limbs, shortness of breath, rapid heart beating, crying, panicked speaking, uncontrolled fleeing from the cause, and shaking.

I had no control over when these panic attacks would occur and they would always be inconvenient. Not only were they at the worst times but they were also incredibly draining.

If I had one before a test, it would be incredibly embarrassing to run out of the room, seeming like I was only crying, and to come back moments later to take the test with even less energy than I had before the attack. My anxiety hurt my grades and ruined many social events for me.

Thankfully, I was able to receive help with my anxiety (through therapy) to make it less severe, but I know many people don’t have that option.

According to an IBCCES study, approximately 80% of children with an anxiety disorder are not receiving treatment or proper accommodations. We all have to work together to bring that number down.

synesthesia

by Caroline Zuba art by Lily PacuitNeurodiversity is a vibrant and colorful lens that allows people to perceive the world in unique ways. While there are cons to such conditions, each thunderstorm is followed by a rainbow of opportunity.

Both the virtues and negatives of neurodivergence mix for a convoluted yet versatile reality that is worth exploring for the sake of developing empathy, sensitivity, and understanding of individuals who struggle with their sense of self.

Synesthesia is a condition in which the five senses (seeing, hearing, tasting, feeling, and smelling) are intertwined with one another upon perceiving sensory stimuli. For example, if someone hears a low pitch on a piano, it might conjure up a blue image in their mind.

An important distinction is that association and synesthesia are different entities. Association is a universal representation of the world around us, learned through repetitive outcomes and familiar reactions. For instance, if I ask you what colors you associate with December, you will likely say white, red, or green. These are associations — often societal constructs that many share. Synesthesia, however, comes innately, without any practice or rehearsal. This condition is unique because it’s something that can’t be learned.

The most common type of synesthesia is known as grapheme synesthesia. When someone speaks, reads, or writes a word, people with this condition experience a color in their mind’s eye.

This color will always stay the same for that particular word, and every word has a different color. For example, someone might see the word “December” as lavender purple, not white, green, or red.

Next, there is chromesthesia, when someone hears colors from different tones, pitches, or notes. Like grapheme synesthesia, these colors are completely random, innate, and never change. For example, someone might experience the color yellow with low notes on a scale and the color orange with higher notes.

Finally, there is mirror-touch synesthesia — the rarest form. This is when someone perceives a physical sensation on another person and feels that same sensation on the opposite side of their body. For example, if a person with this condition watches a friend get slapped on their right cheek, they will feel a slapping pain in their own left cheek.

Diagnosing synesthesia is quite simple. There is an online test that gauges the accuracy of your claimed colors with matched words. If I say “December” is lavender on one of the test questions, it will come back to this question within a few minutes. If I once again answer with lavender, I show consistency in memory patterns. The test asks you up to thirty words in addition to their colors.

The speed at which you answer these questions succeeds in separating the associates from the synesthetes, as synesthetes are able to fly through this exam because they

know the colors immediately.

What are some of the benefits of synesthesia? Those with grapheme are proven to have an advanced level of memory, since colors add another pathway to processing sensory information. If you had to memorize a number combination — 33498, for example — colors for each number would make order recognition easier.

This facilitates memorizing math formulas or word definitions. Another perk is a deeper emotional connection with the outside world and more intense emotional perception. In addition to color, certain words, inanimate objects, or people can be given emotions or genders. For instance, all even numbers might be female to you.

Synesthesia can spark emotional attachments to random subjects based on colorful first impressions, but they can likewise cause adverse reactions. This large spectrum of emotional like versus dislike creates sensitive thought processes which can be both a blessing and a curse.

Synesthesia is a complicated gift worth sharing with those around us. Sharing our unique qualities makes the world a better, more diverse place. Be proud of who you are and know that every human’s perspective is worth exploring. It is through empathy and listening that we can break down stigmas that marginalize diversity. It is through empathy that we can bring love to abnormalities.

crisis numbers

by the by Auva Vaziri90% of American adults believe the United States is in a mental health crisis, according to a 2022 survey by CNN and the Kaiser Family Foundation. Today, more people are struggling with their mental health than ever before.

According to Mental Health America’s 2023 State of Mental Health In America report, 21% of American adults are currently experiencing a mental illness — over 50 million people.

There are a number of factors to explain this increase, namely social media, the COVID-19 pandemic, and societal trends. Let’s dive into each of these to see how they are affecting our mental health.

Social Media

Did you know that high usage of Facebook, Snapchat, and Instagram increases rather than decreases feelings of loneliness? While most people know an excess of social media isn’t good for you, more and more research is finding that too much social media use is strongly linked to feelings of depression, isolation, anxiety, self-harm, suicidal thoughts, and more.

While many social media platforms are marketed as tools that enable people to share their genuine lives and express themselves, very few people are authentic online.

In reality, many if not most people consistently edit their photos and only post from the best moments in their lives, creating the false personalities of people who have stellar lives and no problems. People, especially young people, are constantly comparing themselves to these flawless archetypes and becoming extremely insecure about their bodies and their lives. This can lead to extremely low self-esteem, feelings of isolation, depression, etc.

FOMO, the fear of missing out, is

another dangerous side effect of social media. Every day, social media floods us with information: the best new chocolate cake recipe, photos from a party held by your friends, text messages from your significant other, celebrity gossip — the list is endless.

When we’re off of social media and no longer have this instantaneous access to information, we can develop a fear that we are missing out on all of those social activities. This feeling can fuel an addiction to social media, driving us to constantly check our phones for updates when we should be studying, working, or sleeping.

This constant anxiety and addiction can come at a steep cost to our mental health. A 2018 study by the University of Pennsylvania found that college students who restricted their social media use for just three weeks showed significant decreases in feelings of loneliness and depression compared to college students who had unrestricted access to social media.

The COVID-19 Pandemic

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1 in 5 American adults claimed that the COVID-19 pandemic had a severe negative impact on their mental health. Before the pandemic, the rate of serious psychological distress among American adults oscillated between 3% and 4%, according to a 2022 study published in JAMA Network Open. Yet in just the first year of the pandemic, anxiety and depression increased by 25% around the world.

There are a multitude of explanations as to why the pandemic initiated such a mental health decline — the primary one being social isolation. With jobs and schools closed for months on end, people were effectively cut off from their relationships.

Human interaction is one of the most significant boosts for our mental health, and without these connections to families, coworkers, and peers, isolation severely worsened our state of mind. In addition, during this period many adults lost their jobs and/or struggled financially, and most of us lived in constant fear of ourselves or a loved one contracting a virus there was little information about or treatment for.

All in all, the pandemic isolated humanity for several years. For many, this isolation led to loneliness, which is linked to a number of both physical and mental health issues.

Societal Trends

Isolation isn’t good for mental health. And yet, recent social trends are subtly promoting more and more isolation throughout society.

Even before the pandemic, isolation in the general public was increasing due to trends such as decreased community involvement, fewer people getting married and having children, and social media use. In 2019, the American marriage rate was at the lowest level ever since the government began keeping its records in 1867.

In 1951, around 80% of American households were composed of married couples. In 2020, that number was 49%. More couples are delaying marriages, more people are expected to never get married than ever before, and millennials and Gen Zers are having fewer kids than previous generations. All of this is contributing to creating a society where more people are alone, and this isolation and loneliness is leading to a decline in mental health.

We must work diligently to prevent isolation as much as possible, and also make sure we are able to provide aid to all those who need it.

2011 2019 2021

* a marker for serious depressive symptoms

All statistics from the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (February 2023)

-

on these oft-overlooked contributors to teen anxiety don’t sleep

by Noah Bleckner, Wren Buehler, Elizabeth LeCours and Mercedes TijerinoDuring 2020, it became very popular on TikTok to fetishize mental illness, sexual assault, self-harm, suicide, and eating disorders. One of the many trends that were gaining popularity was thinspiration. “Thinspo’’ is showing off women’s skinny, anorexic bodies and displaying their meals, motivating young girls to only eat one meal (consisting of no substance) a day to stay slim.

share and share for likes

During the pandemic, many TikTok creators shared stories of their mental health struggles.

Many of these accounts were created with good intentions: to end the stigma surrounding mental health.

Ah, but like so any others, this trend came with a catch.

were genuinely trying to help those struggling feel less alone, many more were created for views and likes.

thinspo step right up, kids declare your sexuality

“[Men’s] mental health doesn’t matter.” says Travis Wilson*. “Stop being a whiny little p----.” Even as awareness of a growing mental health crisis has become more and more ubiquitous, attitudes around boys’ mental illness remain stubbornly toxic.

don’t be a... the doc is inalways

Add to routine under-diagnoses by doctors and trendy depictions of mental illness on social media a growing trend of Internet-inspired self-diagnoses.

While many of these videos

It’s not to say that those sharing on TikTok do not have legitimate struggles. Yet, when people on social media try to turn mental illness(es) into social and/or material capital, consequences can be grave for all involved.

Children who grew up during the pandemic were forced to grow up fast.

One potentially worrying trend among teens and pre-teens is a pressure to settle into identity labels at younger and younger ages.

When Mia was in 5th grade, her friend came out as demisexual — meaning that they are only able to experience sexual attraction to someone with whom they have already formed a strong emotional bond.

Feeling pressure from her friends to figure out, at 11 years

old, her own sexual orientation, Mia turned to her siblings and mom for help.

She was worried her friends would think she was weird or too “basic” for not being gay or going by they/them pronouns.

While some queer students know their identities from a young age, for others, the pressure to immediately figure out and publicize their identity, often from well-meaning but misguided allies or online voices, can be both unrealistic and harmful to developing youth.

*Name was changed

making the grade

The first-ever advertisement for United States Teenager (circled in red) appeared in The New York Times (March 1921). “An auspicious start indeed,” Great Gramps liked to say. “Our first public notice got smothered by baked beans.”

teenager (n.) also teen ager, teen-ager; 1922, derived noun from teenage (q.v.).

- Online Etymology Dictionary

more eloquent and talented teens we still need to hear from in this publication, I’ll keep this first installment of his story brief.

these rich and young.

Gotta

hand it to Great Gramps. He was not satisfied with only leaving a mark on history. He also left his mark on the English language.

“Teenager” was the first (and still to this day, greatest single) feat of agegrade engineering.

Middle Age, octogenarian , young adult (just to name a few) have all proven extremely fruitful age grades over the years. “Tween” was a particularly nice piece of work if I may say so myself.

Age Grade: a life stage (such as childhood, adulthood) through which a group of persons passes, gaining (sometimes losing) certain rights, privileges, duties and/or a recognized status. An age grade often constitutes an identity in common and a distinction from others.

That said, “the teenager” belongs on another level altogether — a true American original that grew into a worldwide obsession.

American teens have not only influenced global fashion, music, movies, beliefs, behaviors, and cuisine; American teen culture, I have heard it argued convincingly, won us the Cold War.

How did Theodore Hughes Sr. come up with the “Teenager?” We all love a good origin story, and Great Gramp’s is certainly more interesting than most. But given how many

As a graduate student in Anthropology at Columbia University in the early 1920s, Great Gramps could not shake the observation that American upper classes had developed a whole stage of life (the teenager) that was essentially unknown to other classes of Americans.

He first noticed the divide during the Great War. His college friends were allowed to dabble and play in a then-unnamed “extended childhood” while their old chums of lesser means were forced to skip from childhood to adulthood and go fight for their country.

This class-age relationship was captured strikingly in F Scott Fitgerald’s short story “Bernice Bobs Her Hair” published in the May 1920 edition of The Saturday Evening Post.

Fitzgerald described a culture created by the young and rich which was at the same time, playful, competitive, idle and cruel. In the story, the working class were literally left watching from the outside looking in through the windows of country clubs and other playgrounds of

With a mind for entrepreneurialism rather than academic anthropology, Great Gramps asked what would it mean for America, its young people and its economy, if he could define, design and promote a more accessible version of the teenage identity complete with shared behaviors, beliefs, dreams, roles, and expectations (or lack thereof).

“The world,” he answered his own question.

By the end of the 1920s, the term “teenager” was so ubiquitous and America so infatuated with teenage culture, that no one could remember a “before” time when the term and concept did not exist.

As culture critic Salvatore Courtemanche wrote in September 1929, “While we were focused on threats from abroad, America was sacked by its own ‘teenagers.’ They have forced us by croquet-mallet-point to commit idolatry in worship of idleness.”

What a difference a century makes (or not).

Now, back to your regular programming and the voices of today’s teens.

- Theodore Hughes IV Illustration from “Bernice Bobs Her Hair” The

you can’t opt out of who you are LGBTQ+

by Jaylen McCullough photography by Antonio PersiTheLGBTQ+ community has been established for several centuries, yet it’s become far more prominent in Generation Z. According to a poll by Gallup in early 2021, 21% of Gen Z adults are LGBTQ+. In 2017, it was half that number.

The LGBTQ+ process of self-discovery can affect us in many ways, whether it’s through our friendships, romantic interests, families, or mental health. Many of Gen Z are struggling with mental health, trying to battle constant hate such as the anti-LGBTQ+ legislation being pushed by conservative lawmakers.

According to the CDC’s 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, LGBTQ+ youth are more than three times more likely to attempt suicide than their peers.

This mental distress stems from the lack of accepting parents and friends, bullying, threats of conversion therapy, lack of safe spaces, and hateful legislation.

The Trevor Project is a nonprofit whose goal is to prevent suicide in the LGBTQ+ community. According to the Trevor Project’s 2023 National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People of those teens who had attempted suicide, 15% said their home was non-LGBTQ+ affirming and 16% said their school was non-LGBTQ+ affirming; those that were affirming were reported as 10% at home and 12% at school.

If we only show more accep-

tance and understanding toward our queer youth, we can see a fall in LGBTQ+ suicide rates. And that’s only the beginning.

I ran a google form and collected data from queer students through social media about how their identities conflicted with their day-today lives and impacted their mental health.

Calvin*, a transgender queer 17 year old, on pronouns and gender: “People do not understand how greatly just respecting pronouns can help a trans person. Getting misgendered no matter how much you try to present as your gender takes a major toll on someone’s mental health. Having a support system has saved me from being in a really bad place.”

Symon*, an unlabeled transman, is unsettled by negative, wrongful portrayals of his community and lawmakers trying to erase his rights. “I hate negative portrayals of LGBTQ+ in media.

“Why can’t we be more positive now instead of reminding the queer community of harmful imagery they’ve always had to live with?” said Symon. “I absolutely can’t stand lawmakers, either, trying to erase the rights of LGBTQ+ minors and trying to take autonomy over the bodies of trans youths.”

Others described lawmakers trying to erase their rights as “unacceptable” and that the legislation made them feel “less human,

like I’m doing something wrong.” In 2022, according to the Human Rights Campaign, 13 states signed anti-LGBTQ+ bills into law, 23 states introduced anti-LGBTQ+ bills, and only 14 states and Washington D.C. had no anti-LGBTQ+ bills introduced. As of late January 2023, over 120 bills were introduced nationwide and reported by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

As of February 24th, 2023, the ACLU states that 327 anti-LGBTQ+ bills have been introduced to state legislatures. This is outrageous for a country that is supposed to be the “land of the free.” How can we live up to this name if lawmakers are trying to keep the queer population, both young and old, from living their authentic lives and being true to themselves?

Queer people should not have to live their lives in fear. No minority group should. Thankfully, Montgomery County is a fairly liberal place to live in, but like any other place in America, bigotry is still a reality. Throughout the nation, we are seeing more and more protests against anti-queer laws, and the more we fight back, the harder it will be for lawmakers to ignore us. We must keep fighting so they cannot erase who we are.

*Names in this article have been changed to protect the identities of surveyed students.

students need our support now more than ever

the cost of masking emotions

by Brooke Rosen art by Miravan KimEmotions are a natural phenomenon we all experience. We all process a variety of emotions every day.

So what causes people to downplay or suppress their feelings?

Such behavior results from many scenarios; however, most commonly, it stems from emotional invalidation. This is when someone hides their feelings because of the lack of acceptance in their environment. Psychologists refer to this as “masking,” which can be apparent in many social issues, one being toxic masculinity.

Through a series of interviews in 1996, Dr. Bird, a professor of Sociology and program officer for the National Science Foundation, showed that many men felt expressing or acting on emotions and behaviors linked with femininity, such as showing signs of intimacy, was deemed inappropriate and stigmatized when connecting with other men.

As a result, it is no surprise that in a survey of over 1,000 boys between the ages of 14 and 21, over a third expressed they were currently facing mental health issues, and nearly half of them rejected the idea of asking for help (stem4 2021).

“As you get older, no one cares about your mental health,” explained one survey respondent. “So you say you're OK when you're not because you're supposed to be a man” (stem4 2021).

When people choose to mask their emotions, they put their relationships at risk. No matter the relationship, whether with a significant other or co-worker, they all require access to emotions. Therapist Shari Foos states, “If you don't allow yourself to be vulnerable, your

partner can't be expected to understand what you need and want from them.” She says, “They will undoubtedly respond in unsatisfactory ways. And then, because you don't feel supported, you can resent them and blame them rather than owning your feelings.”

Generally, people understand how to read others' feelings, especially loved ones. Emotions appear in body language, facial expressions, vocal intonations, and behavior. Therefore, if our words go against our actions, people will notice.

Bottling up emotions also leads to unhealthy coping mechanisms. People who experience negative emotions and suffer from poor mental health are at high risk of abusing substances and further developing an addiction. Scientists have discovered that drugs affect the brain’s limbic system, which is responsible for processing one's emotions. Have you ever woken up after a night of using substances and felt guilty or embarrassed? Imagine trying to process those feelings as you also try to manage the preexisting emotions that got you to act on such behavior in the first place. This behavior is a recipe for addiction because people get so uncomfortable that they use more substances to separate themselves from their actions.

Lastly, people who choose to avoid their emotions face the possibility of many health issues, including an early cause of death. According to Edward-Elmhurst Health Organization, since the heart and mind are intimately connected, negative states of mind, such as chronic stress, may increase the risk of facing heart disease or worsening pre-

existing heart-related issues. This is because chronic stress exposes your body to unhealthy elevated levels of stress hormones, like cortisol, and may impact the way blood clots. Such changes can set the body up for a life-threatening heart attack or stroke. A study conducted in 2013 by the Harvard School of Public Health and the University of Rochester showed that people who suppress their emotions have a 30% increased risk of premature death and a 70% increased risk of being diagnosed with cancer.

For these reasons, there are many options if you or someone you know feels stuck without a place to go to. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (SAMHSA) is an administration through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. SAMHSA allows you to visit their website, type in your zip code and find services that allow access to mental health clinics.

In more urgent situations, SAMHSA also offers a free hotline open 24 hours a day (call or text 988). Another resource is Free Mental Health, a government-funded, non-profit organization in Maryland. This non-profit provides free services accessible to anyone in every city within the state.

Finally, in recent years in attempts to make therapy more accessible, there have been several mental health apps that have surfaced on the Internet. Such apps connect you to hundreds of therapists so that you can choose the right one for you. Examples include BetterHealth, Moodfit, and Talkspace.

No matter who you are or your story, there are people out there who will listen.

AsAshley* sits in her room, she focuses in on her phone, tuning everything else out. She posted on Instagram about five minutes ago, and now she waits for the likes and comments to roll in.

“I can’t only have 100 likes, I would have to delete that. That’s terrible. Maybe people aren’t liking it because I look bad? Or maybe they think it’s weird?” Could it be said that social media has driven a wave of mental health struggle s among teens?

As long as social media has existed, it has had tremendous effects on the mental health of its users. Its more negative impacts have been felt most strongly by teenage girls.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the amount of time people spent on social media increased dramatically. Teens were forced to stay inside, all by themselves, and resorted to communicating with others on the internet.

According to JAMA Pediatrics, non-school related screen time among teenagers doubled from pre-pandemic estimates of 3.8 hours per day up to 7.7 hours. Along with this, 63 percent of U.S. parents reported that their teens used more social media than they did before the pandemic, according to Statista.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), suicide attempts among adolescents has increased by 31 percent from 2019 to 2020.

Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts in 2021 were 51 percent higher among girls ages 12–17 than during the same period in 2019. This evidence makes it impossible to ignore the fact that the mental health crisis coincides with an increased use of social media.

To Ashley, a high school senior, her phone is her everything. The screen time on her phone reaches a

whopping 10 hours and 22 minutes daily.

She is active on most social media platforms, including Instagram, Snapchat, Tiktok, and Twitter. Traditionally, she communicates with her friends mostly through these apps, avoiding conversations in person and over the phone. She believes this has hugely affected her social life and confidence. Relying on these platforms to communicate with others allows her to hide behind a screen.

Considering all of this, she does think there are benefits to the rise of social media. As she has just committed to college in another state, she is able to connect with hundreds of students from all over the world who will attend the same college.

In this case, she can find a roommate, friends, and learn more about the school through students who are currently enrolled. In addition to this, she is able to keep in touch with her friends she has made over the years at sleepaway camp.

As a teen girl who relatively recently deleted social media, Courtney, age 17, has a drastically different perspective on social media use. Driven by her recognized addiction to social media in the past, Courtney made the decision that it would be better for her to delete her social media accounts.

When asked what her final turning point was, she notes the exact moment she found herself sitting at home over spring break mindlessly scrolling on Instagram, seeing all her peers on vacation.

She thought to herself that she could either keep scrolling, making herself feel sad that she was not in some tropical location or delete her social media accounts that were taking such a toll on her.

When I asked Courtney if she

felt as though she was missing out on aspects of teen culture that came from social media, she noted that although she recognizes that she’s sure that she’s missing some trends or some inside jokes, she feels the weight of missing out on those trends is insignificant compared to the improvements she experiences in self-esteem and time management.

As a mother of two high school students, Jessica is deeply concerned with the effect social media has on not only her own children, but all teenagers. She says that because teenagers spend all of their time on social media, it has become their entire social life.

“That’s how they talk to people, that’s how they make friends, that’s how they make plans. Everything is through social media,” Jessica said.

Contrasting her own experience growing up without the intricate world of social media, she notes that now teenagers do not know how to act in the real world. This is an issue that is becoming more and more apparent. Whether it is choosing to stay home and talk to friends online, or simply avoiding conversations by staring at their devices, teenagers are not being forced to face the present moment.

No matter how hard Ashley tries to avoid the negative impacts of social media, the culture around these applications has made this impossible. She, and millions of teens worldwide, are dealing with this same dilemma today.

“Something must be changed in society if every teen feels the same way,” Ashley admits with disbelief. “It has to change.”

*All names have been changed

not your daddy’s dread a more sensible, existential fear

by Charles Barker, David Bodner and Roman Fails art by Betsi Ralda-Romero“Ava, are you optimistic about the future?”

“Do you mean the future in general or my future?”

“Either.”

“Um… not at all. Because I feel like the world right now is in shambles, and I don’t know if it’s going to get better.”

Ava* is a teenager. At the age of

18, she’s already confident that the world is going to shit. To anyone who’s talked to a teenager recently, this should come as no surprise.

In recent years, it seems like teenage cynicism has been on the rise. The teenage mental health crisis is real and well-documented: 19% of high school students seriously considered suicide in 2020, according

to the CDC.

Over half of our generation believes that this is a bad time to grow up, and 36% think that “political involvement rarely has any tangible results” according to Washington Post and Harvard Kennedy School polling. This paints a bleak picture of the hopes of America’s youth.

However, if you take the time

to talk to the people behind those numbers, it quickly becomes clear that America’s teens aren’t cynical in quite the way you might expect. Their cynicism isn’t the stereotypical, single-minded “rage against the machine” that’s often associated with teenagers. It has shifted into a carefully thought out, bleakly rational evaluation of the world around them.

Marshal has seen a lot of that world. As a junior in high school, he lived in Japan, Vienna, and India before ending up in the States. This experience has given him a worldview that seems at least superficially hopeful:

“At an individual level, you have to feel optimistic about the future. You have to make yourself believe,” he says, his voice even and measured. Listening to him talk, you can hear the “but” coming.

“But at a societal level, you can’t be that optimistic.” This isn’t a oneoff gripe from a disgruntled kid. It’s a result of climate change, political polarization, and new technology we don’t understand, he explains. His vision of the future is frustratingly grim—and frustratingly hard to argue with.

He’s not the only one.

Andrew, a runner, choir singer, and a huge college football fan, thinks hard about everything he says. He chooses his words slowly and intentionally, carefully constructing theses about anything and everything — often Bama football.

But when he turns his analytical eye away from the gridiron and towards the future of our world he delivers a sobering evaluation: “I would consider myself pessimistic. Even as technology may assist human life, it will also lead to unforeseen issues and give human beings more tools with which to harm each other. This harm is something that comes from human nature — social and political changes will not eradicate human evil.”

Merriam-Webster defines cynicism as “distrust of human nature and motives.” Based on this, Andrew sounds like a textbook cynic. And yet, talking to him is a far cry from the stereotypical idea of the edgy, glibly nihilistic teenager.

He couches his claims in a discussion of how the loss of community in America has affected the teen suicide rate and how the electoral college dilutes and alienates participatory democracy. It’s a characteristically thorough dissemination of the state of our world and country, and the conclusions he draws don’t look promising.

ticipation, and change-making for teenagers. They both pointed out how hard it is to feel like your actions are meaningful when you’re stacked up against a country of millions or a world of billions.

Greta Thunberg is 20 now, but she started her activism as a teenager. She wanted to take a stand against the impending climate crisis because she felt that no one else had. She saw adults and teens alike ignoring the problem and kicking the can down the road.

Yet even as she spoke up, the same adults that refused to do anything about climate change dismissed her concerns about it as well; Michael Knowles, a conservative extremist, said her supporters were exploiting her and called her a puppet of the adults around her.

It seems like blissful childhood ignorance is a thing of the past. The Internet-driven information revolution has made today’s teens more aware of the world around them than any prior generation was at their age. This awareness largely takes the form of knowledge about suffering, global threats, international catastrophes, and injustice.

A true cynic might argue that it’s just because that’s the direction the world is headed. But it’s also undeniably true that the bad news catches our attention more than the good. It’s what gets clicks, especially on social media, where many teens get their news. Whatever the reason may be, today’s teens are hyper-attuned to the state of the world they live in, and they’re not loving what they see.

But if you don’t like the state of the world, why not try to change it?

This, of course, is easier said than done. Both Marshal and Andrew had a restrained view of the possibilities of activism, political par-

However Greta’s activism doesn’t come from some misguided teenage impulse. It’s much simpler than that: she’s recognized a problem that she cares about, and she wants to fix it. And yet, from an adult’s perspective, teens are often just inexperienced, reactive “puppets” to their environment, without real agency.

Greta might be the most prominent example, but teenagers everywhere are realizing that they’re growing up under existential threats of unprecedented scope and scale. For some teenagers, this constant press of worldwide crises and incessant change forms the backdrop for a life filled with the same challenges that have plagued us for generations.

“Being a Black woman — do you know the quote that’s like ‘You have to work twice as hard to get half as far?’” asks Ava. Remember her? She’s a future D1 lacrosse player who, as cliche as it sounds, succeeds on and off the field. Like her peers, she’s acutely aware and afraid of the threats she and her friends will face in the future. This fear isn’t abstract or melodramatic. continued on next page

“Whatever the reason may be, today’s teens are hyper-attuned to the state of the world they live in, and they’re not loving what they see.”

It’s cold and strikingly immediate; her friends aren’t sure they’ll want to bring kids into that future.

Ava finds ways to cope. She has given her “life and time and energy” to lacrosse, and as a result, it’s a sport in which she excels. Despite this, she’s still dogged by the feeling that she isn’t acknowledged for her achievements. Underappreciation almost always leads to disaffection, even in the best of us. When this is set against a backdrop of personal and societal struggle, it’s hard not to see the seeds of pessimism being sown.

Some teenage worry about the future certainly comes from largescale existential fears. But, listening to Ava self-assuredly state that she’s “not at all” optimistic about the future, it’s hard not to hear a twinge of the mundane—this is just how it is for us, she seems to be saying. Even without the barriers of structural racism, it seems hard for anyone to believe they can make a change these days.

“I’m an 18-year-old; as a kid, of course, you’ve seen things that you have issues with, that you want to change,” says Andrew, “but you know that you’re not currently in a position of power with which to change them.”

This captures perfectly the psychological struggle of the modern-day teenager. It’s not that they don’t want change; many seem to want nothing more. But at the end of the day, teenagers, even legal adults, find real power hard to come

by — after all, they’re still just kids.

In 1967 the anthropologist Victor Turner described a concept he called “liminality”: a position “betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention, and ceremony.” He probably didn’t know it when he wrote those words, but, 56 years later, this concept of liminality perfectly describes the plight of the modern-day teenager.

Teenagers are mired in a liminal phase between the innocence of childhood and the action and agency of adulthood. They’re aware of the realities of the world; they see the worsening climate, the political polarization, and the increased anxiety and depression among their peers. However, they lack the power to do anything about it.

Most teens can’t vote. Many who can, don’t. On a social level, their worries are often dismissed as a “phase” or a symptom of passing teenage angst. They aren’t listened to or taken seriously by adults, even when, like Greta Thunberg, they’ve spent almost a quarter of their life on the same cause. The prevailing logic is that teenagers are immature and naturally rebellious against authority, so none of their concerns are viewed as valid.

If you want to change, it seems like the best way to go about it would be to talk to the people making the decisions. Ava has done that. She’s had the opportunity to meet with senators and legislators, and she says it showed her in

practice that she can “speak up and take action.” But the quintessential teenage doubt still lurks: “It’s like — were they listening? Did they take what I said into consideration?”

This doubt is the fuel that keeps the fire of teenage cynicism burning. Teenagers are unavoidably inundated with information about a world that seems hell-bent on catastrophe. They’re not optimistic about the future, but they think they’re too young, too powerless to change it. Faced with what seems like an unassailable reality, many of them have decided not to try. The few who do often feel like their efforts are met with a condescending smile or a flippant wave of the hand. Teenagers are apathetic, cynical, disaffected, and scared.

The worst part? This attitude seems all too sensible. It’s not a knee-jerk reaction but a fully fleshed-out rationale, a way of seeing the world. If you think about the state of that world for too long and start to weigh the odds a little too carefully, cynicism almost starts to seem like the only logical mindset. But the danger of cynicism, no matter how rational it might seem, is that it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Have you ever wanted to make a positive change in the world and felt like you couldn’t?” we ask Marshal.

“Everyone’s had a situation where they want to do something for the world or have a positive impact on it,” he said, “but I think we always end up hitting the barrier that right now, as minors, as people with basically zero power on the world stage, you can’t do anything.”

Marshal’s explanation succinctly captures the frustrations of a generation. And when you think you can’t do anything, you might as well not even try.

“Me personally?” Marshal says, “I’ve never had that problem, because I’ve never actually tried.”

*All names have been changed.

accepting rejecting who you are

by Miles Haraldsson, Sam Meddin, and Tristin Vittaut art by Hannah FaragAs the final bell of school rings, Allen*, a high school senior, hastily leaves the building and mounts his bike to embark on the thirty-minute ride to rowing practice.

The clock strikes three and he arrives just in time to hit the water with his group for the two-hour practice ahead. As practice slips away, he begins to prepare himself for his one-hour bike ride home.

Once he gets home, his muscles ache, and his eyes are half shut, but he’s yet to even start his English essay, history presentation, math homework, and to finish his college application.

Time quickly passes by and as the clock strikes twelve, Allen realizes that his homework still isn’t done and that he needs to wake up in just six hours. For Allen, as he heads to bed, this isn’t the end; it’s just the beginning. High schoolers across the country face a cycle of a never-ending overload of work that they can’t escape. It leaves them consumed by the never-ending race to meet the deadline.

The acceptance rates for colleges have significantly decreased in the past twenty years. For example, according to bizjournals.com, Harvard’s acceptance rates have dropped from 5.2 percent for the class of 2021 to 3.2 percent for the class of 2026. This visible increase in academic filtering is forcing high school students nowadays to work harder than they did 30 or 40 years ago.

To aim for prestigious colleges, students find themselves in a circumstance where they must outperform numerous other students. Even when they put in the effort to do this, there is still some unknown in terms of if they will be accepted. While the pressure and

success needed to go to a top school have significantly risen, high school culture can disincentivize students from trying hard to do well.

Terms like “try-hard” and “nerd” have been coined to diminish students who put in a great deal of effort to nothing more than people with no social lives who spend all their time studying. This leaves many of these students excluded and viewed as outsiders by their high school community.