turnsteenager 100

volume 1: the kids are alright, right?

volume 1: the kids are alright, right?

C o n t e n t s

I just getting started

- staff list p. 4

- high schools amplified p. 5

- foreword p. 6

- word from our editors p. 8

- word from our sponsor p. 10

- the locked door in the basement p. 12

II navigating the language of mental health

- misunderstood p. 14

- misusing labels p. 15

- 504/bipolar disorder p. 16

- OCD p. 17

- anxiety p. 19

- synethesia p. 20

III the quantifiable & not-so-quantifiable

- crisis by the numbers p. 22

- oft-overlooked p. 25

IV making the grade

-“teenager” becomes a thing p. 26

V features

- LGBTQ+ students & our support p. 29

- the cost of masking emotions p. 31

- broken functions p. 32

- a new dread p. 34

- rejecting who you are p. 39

- competitive illnesses p. 40

- around the world p. 43

VI the science fiction of teen mental health

- introduction p. 47

- the panopticon p. 49

- crushing on our oppression p. 53

- sheltered to death p. 56

- what reality are you living in? p. 58

- feeling grotesque p. 60

VII creative writing

- find sanctuary p. 62

- welcome p. 63

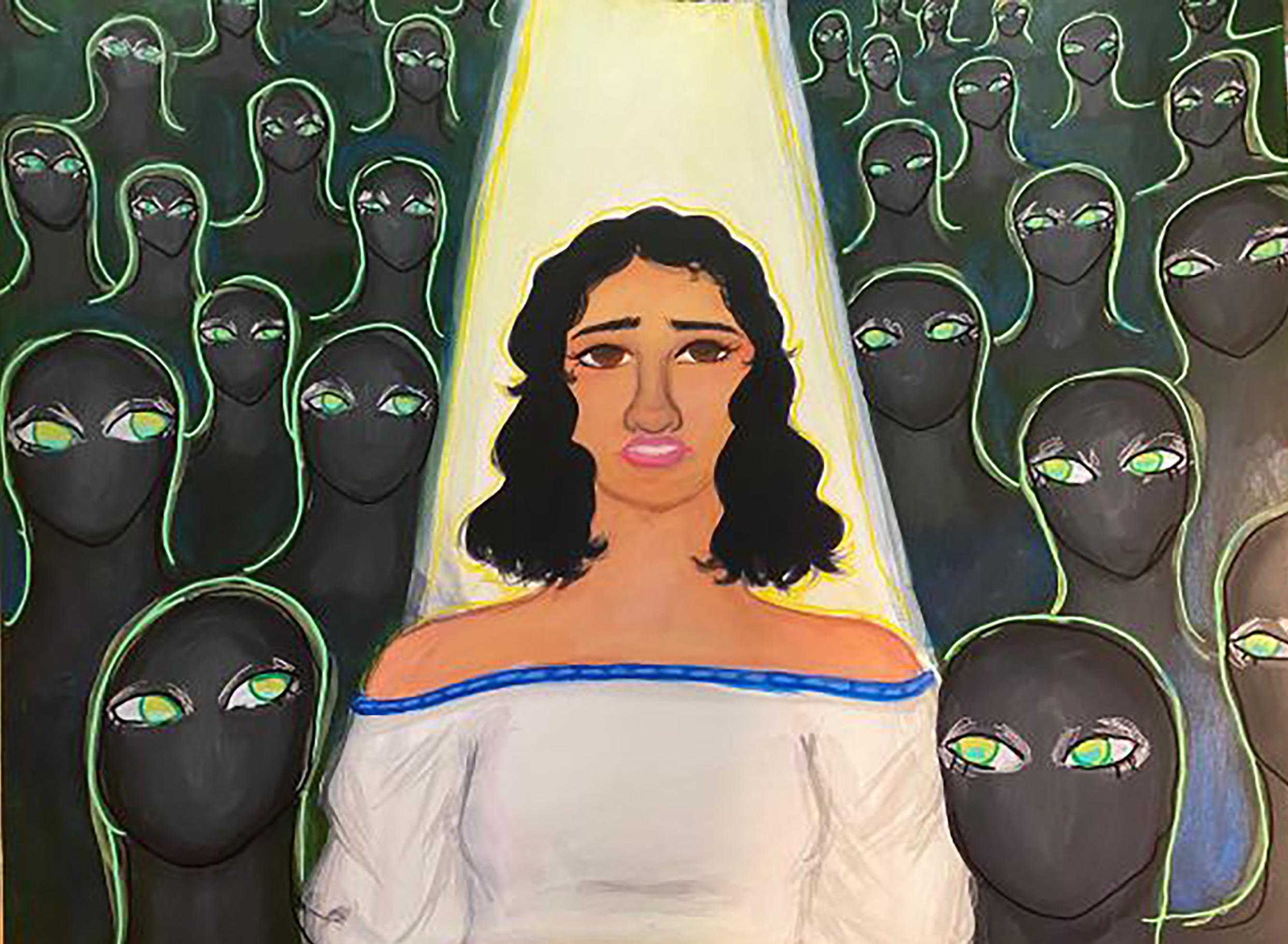

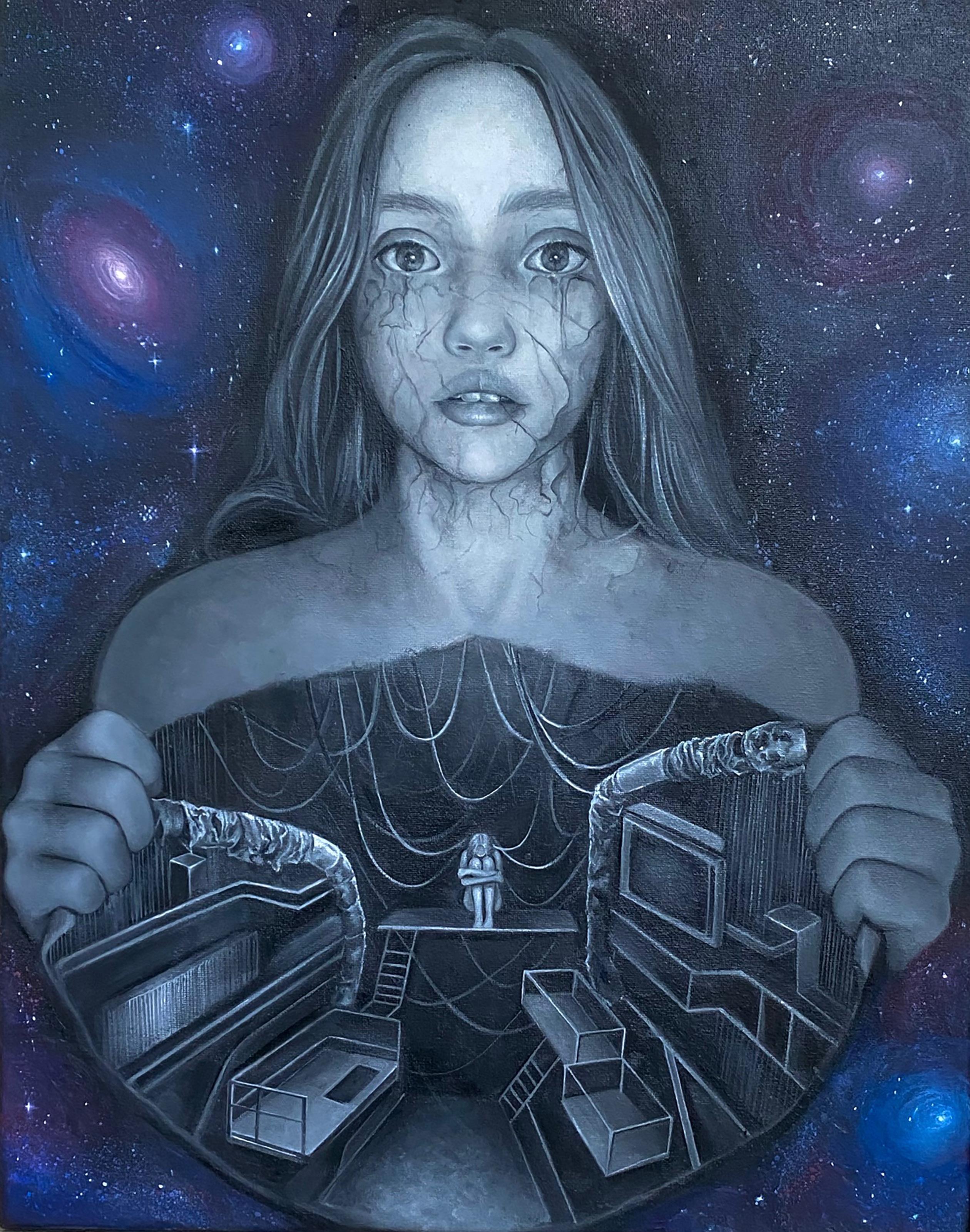

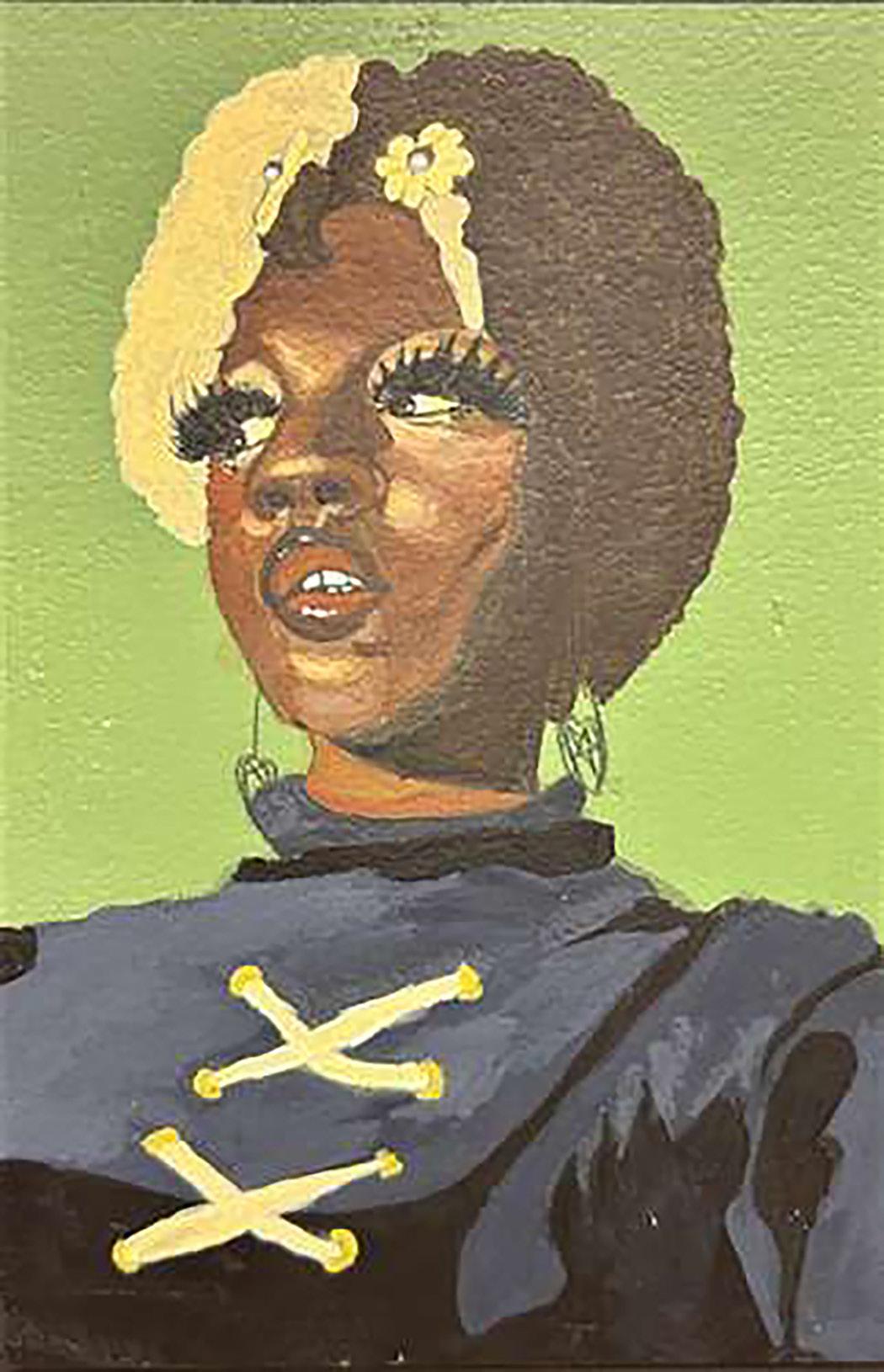

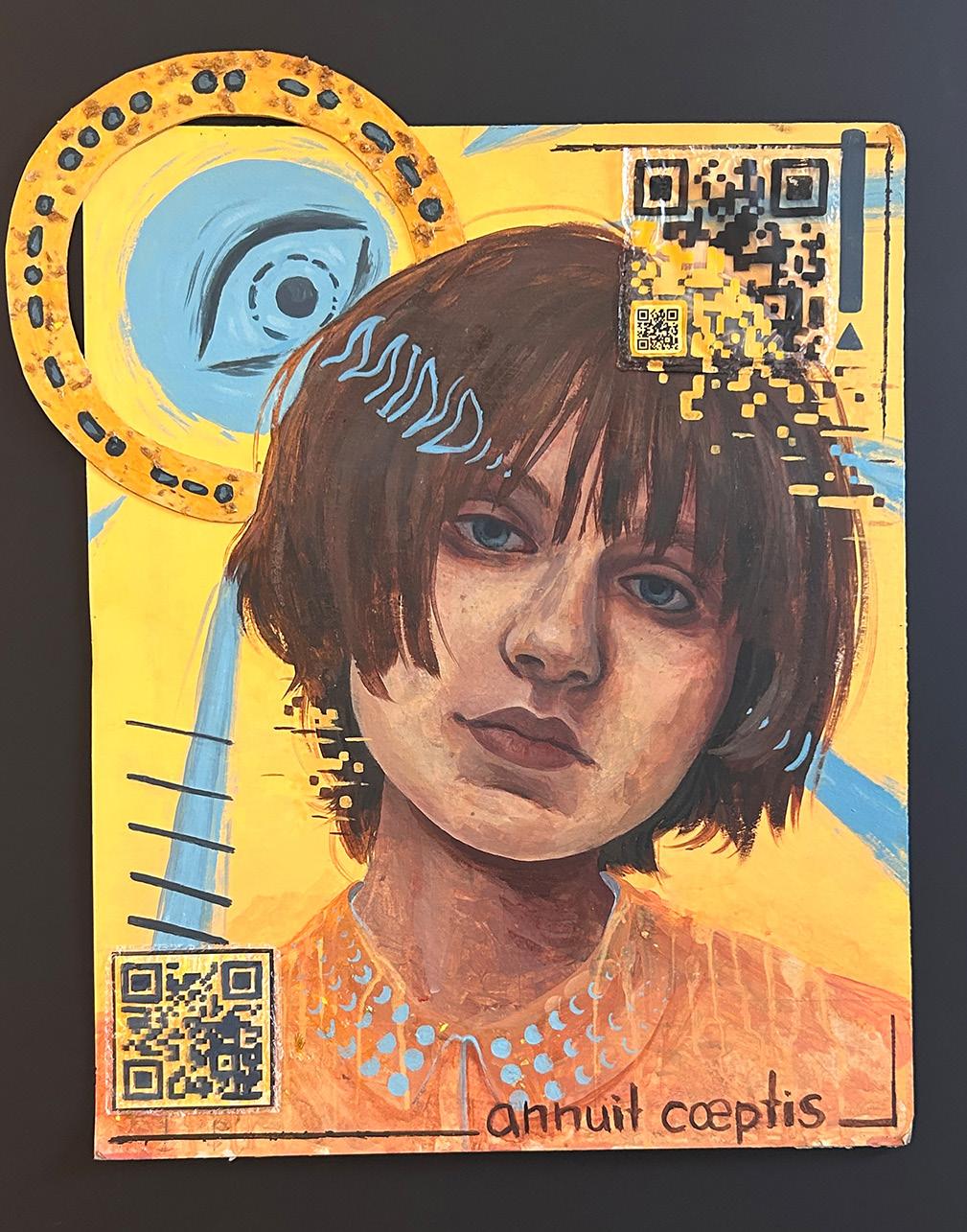

cover artists

Olivia Ensign (front cover) Amber Auth (inside front cover/left) and Daviana Marcus (back cover)

The Amplifie

Montgomer y County’s Student-led Magazine

‘22-’23 editors in chief

Bennett Galper

Gabe Gebrekristose

Isabella Kriedler

‘23-’24 editors in chief

Milan Bhayana

Michaela Boeder

Elizabeth Mehler

Auva Vaziri

art editors

Katherine Barnett

Carol Li

Riona Sheikh

art team

Helen Marie Besch

Daviana Marcus

Lizzie Varner

faculty advisor

David Lopilato

Special Thanks to

Sarah Harnish and Mygenet Harris

curatorial and editing team

Michael Demske

Indira Kar

Francesca Lisbino

Jaylen McCullogh

Colette Mrozek

Antonio Persi

Shelby Roth

Kaitlyn Schramm

Rachel Smith

(co-coordinators and instructors at The MCPS Visual Arts Center)

-

The MCPS Editorial Graphics and Publishing Services team

Representative Jamie RaskinJulia FriedmannRebecca Dillon

None of this would be possible without you.

To learn more about The Amplifier and join the movement, follow us on Instagram @mcps.theamplifier.

To order free print copies of our publications, visit

high schools amplified

Bethesda-Chevy Chase

Montgomery Blair

James Hubert Blake

Winston Churchill

Clarksburg

Damascus

Albert Einstein

Gaithersburg

Ivymount

Walter Johnson

Col. Zadok Magruder

Richard Montgomery

Northwest

Northwood

Paint Branch

Poolesville

Quince Orchard

Rockville

Seneca Valley

Wheaton

Walt Whitman

Thomas S Wootton

foreword

By U.S. Representative Jamie RaskinHow do we promote mental wellness in a world that often seems unsafe, unstable and unwell?

It’s a question of pressing importance to young people seeking peace of mind in the age of climate disaster, COVID-19, violent insurrection, random gun violence, unceasing culture war and online hate.

The precocious and intrepid young reporters, essayists and activists compiling this issue of The Amplifier have curated a brilliant array of individual and collective experiences to provide a powerful answer to this question: the way to promote mental wellness in this unforgiving world is through compassion, humor, honest self-reflection, and the daring expression of sadness and hope, trepidation and joy, loneliness and solidarity.

Young people today face, beyond all the crises unique to our times, the traditional complications of youth in America: heartache and identity crisis, the high cost of college, the vagaries of the immigration process, finding a pathway of integrity and hope in the world.

In the face of these challenges, our young people are surpassing all rightful expectations of resiliency— but they are not “all right” on any conventional metric.

The American Academy of Pediatrics declared the state of youth mental health to be a “national emergency” in 2021 because the pandemic’s hallmark isolation and

anxiety effects multiplied and exacerbated the already-high risk factors for young people.

The young people in these pages know that their personal mental health is shaped and buffeted by the sharp currents flowing in our society. Our LGBTQ+ students know when their humanity is under attack, as do Jewish students and students of color confronting the shocking resurgent waves of homophobia and transphobia, antisemitism and racism. Our students from mixed-status immigration backgrounds live every day with Congress’s refusal to pass comprehensive immigration reform. All students feel the weight of structural political dysfunction. They know when the so-called “adults in the room” are falling down on the job.

Meantime, the troubles of young people and their elders are splayed all over social media, which spreads not only hateful messages but the pressure to post perfect snapshots of perfect bodies. I introduced the CAMRA Act last year to direct the National Institutes of Health to research how social media and other technology are affecting young people’s health and development. I eagerly anticipate the results of this research. I also helped to launch the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline so that every American can call, text, or chat with a mental health professional if and when they are in crisis. This line has recently added more Spanish language services

and an option for connecting with counselors who are specifically trained to support LGBTQ+ youth and young adults. These policy successes mark real progress but do not, of course, fully address the significant and growing needs of our people.

For too long, our society has confined conversations about mental health to the shadows of private life. Until very recently, a person’s struggles with depression, anxiety or other forms of mental illness were compounded by powerful social stigma. People suffering from treatable conditions feared the consequences of sharing their experiences with others, even though social conditions are key to understanding and managing mental illness.

The young people of MCPS have curated a brilliant collection of art and narrative prose to crack open the traditional mold of social isolation, fear and silence. I hope you enjoy this impressive collection as much as I have, and learn from what the authors have bravely shared about their own experiences with mental health challenges.

As dim politicians seek to ban books and threatening ideas, the students of MCPS are creating a powerful message of hope based on free creative expression. I hope that you take the time to read these pages, to learn from these remarkable young people and to work with them for a healthier world.

Special note: Olivia Ensign’s “The Memory Quilt: Pieces of Myself” (featured on the front cover) won the 2023 Congressional Art Competition for Maryland’s 8th District.

art by Evdokia Brazhnikova

art by Evdokia Brazhnikova

the turnsteenager 100

a word from our editors

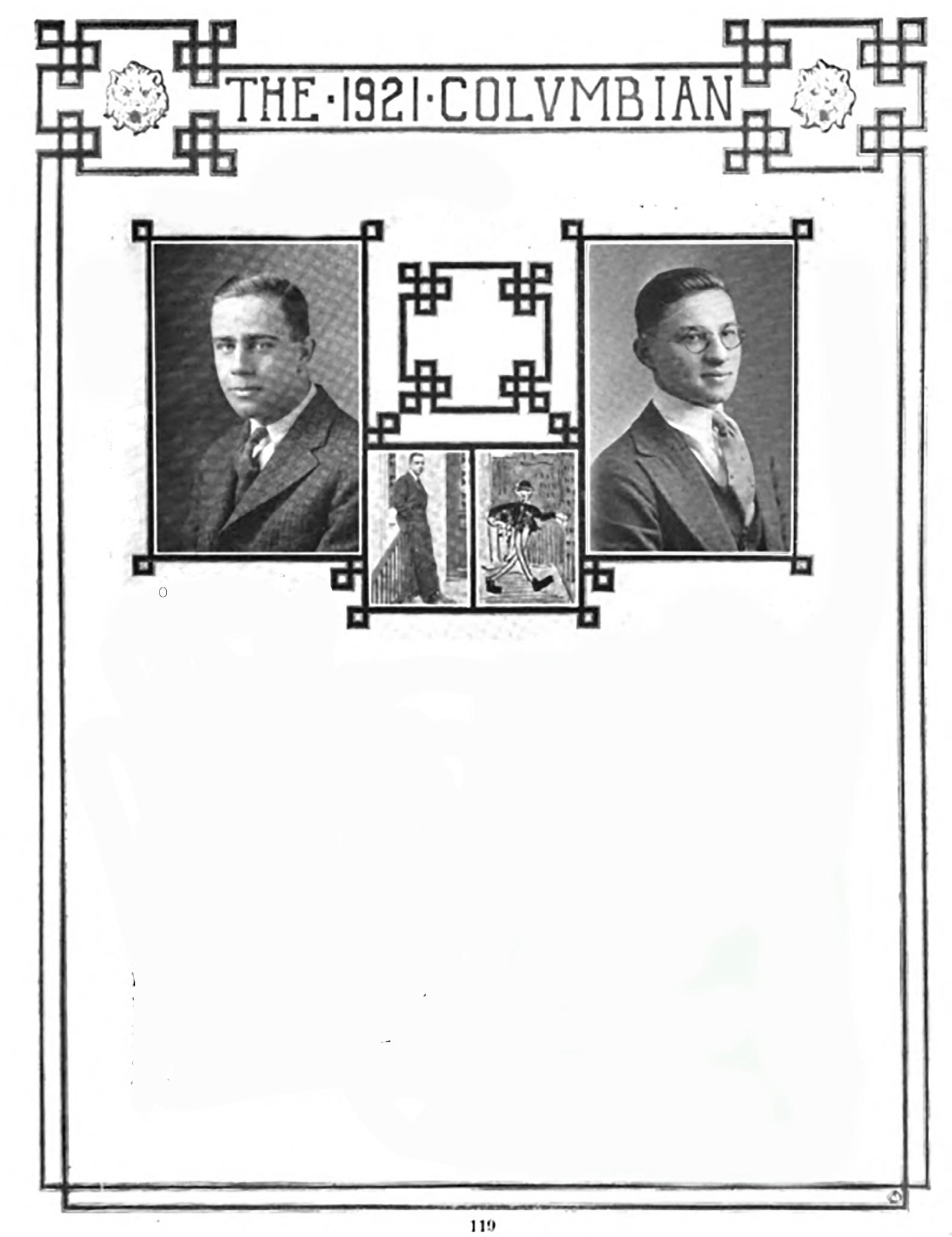

This volume is the first of a series, “The Teenager turns 100.”

The term teenager was coined in the early 1920s to categorize young people who were coming of age and the culture they created.

Stay tuned for our other editions on socializing, expression, sports and academics.

For Volume One, we hear from teens on teen mental health.

According to the February 2023 CDC’s Youth Risk Behaivor Survey, teenage sadness and hopelessness are on the rise across the board.

According to the study, forty two percent of students felt so sad or hopeless that they could not participate in their usual activities (from studies to sports) for two weeks or more.

The pandemic is certainly a big part of the story. There was an eleven-point jump in the percentage of girls feeling sad and hopeless in the first two years of the pandemic.

But the pandemic is not the whole story. There was a ten-percentage point increase in the ten years before the pandemic.

Social media, adults’ favorite boogeyman, is not the whole story.

Today, students have to worry about much more than their academic performance. They also must

craft the perfect resume of extracurriculars for increasingly competitive college admissions. And, tragically, too many student need to do all this in dysfunctional and unsafe educational environments.

Outside of school, there’s the ever-present anxiety about climate change, growing economic inequality, and lack of opportunity for anyone who can’t pay tens of thousands of dollars for a college education.

Today’s teens are more socially isolated than ever. Their few moments of rest from their overloaded schedules are occupied by big tech corporations who turn attention into profit through social media.

None of this is to mention the usual issues teens face in high school, including drug and alcohol use, bullying, and problems with eating disorders and self-esteem.

So why are teenagers struggling with their mental health more now than ever before in history?

As this magazine can attest to, there is no singular answer to that question. Rather, by including a variety of student perspectives, we hope to explore these different factors that contribute to mental health.

In the following pages, you’ll find firsthand accounts of what it’s like

to be in a psychiatric hospital, an investigation of why teens today are more cynical than ever. You’ll learn about how mental health affects LGBT teens, learn why men’s mental health is overlooked, and understand the beauty of synesthesia.

You will read about the necessity of increased accessibility in accommodation plans for struggling students and a firsthand perspective of how social media factors into the equation.

We hope you come away from your reading with a broader perspective of how mental health affects teenagers and a greater empathy for the young people who are dealing with these issues. If you’re a teenager yourself, we hope you feel seen in these pages. Above all, we hope you’re inspired to share your own story.

As a county-wide publication, we hope to amplify the voices of students who don’t have access to a publication and to unite high school students from diverse backgrounds under shared issues that affect us all.

- The Amplifier Editorial StaffThe writers and artists featured in this magazine address emotionally-difficult topics, including suicide. If you’re thinking about suicide, are worried about a friend or loved one, or would like emotional support, call the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline (available 24/7 across the United States).

self portraits

and now, a word from our sponsor

Iamdeeply troubled by the recent report by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) on teen mental health. After all, I am not only President of United States Teenager (UST); I am the proud father to two beautiful and gifted teenage girls.

When Great Gramps, age-grade pioneer Theodore “Teddy” Hughes, drew up identity designs (ID’s) for “the teenager” back in the early 1920’s, he could not, in his wildest dreams, have imagined the impact the American teenager would have on the world.

He also could not have imagined the impact the weight of the world would have on teenagers.

Let me be clear, the “storm and stress” of American adolescence is older than Great Gramps’ earliest sketches.

In fact, Great Gramps set out, in his original design, to give teenagers a degree of agency to deal with “their agonies.”

Even back then, he realized that identity was more than a label. It could provide a power to navigate, even possibly liberate.

The design was not perfect. Which design is?

But, let us not forget that things were not paradise when children transitioned directly into adulthood- thirteen year olds worked in factories, fought in wars, and girdered themselves for marriage.

In contrast, “the teenager” was nothing short of a triumph.

Of course, the storm and stress of adolescence persists today and will continue to persist when today’s teens are tomorrow’s senior citizens.

We at UST know there is no one cause of the decline in teen mental health and no one cure. But, we also firmly believe that we are obliged (in fact, called) to listen to teenagers just as we have done for the past

100 years.

That is why UST is proud to be a sponsor of the Amplifier’s four-part series: The Teenager@100.

While the so-called experts ruminate, let’s let the teens themselves illuminate.

Sincerely,

Theodore Hughes IV President United States TeenagerHappy Birthday American Teens --100 years young

If you need to find Hube on a Friday night, you will have more luck looking in one of Columbia’s many science labs than in one of Manhattan’s many watering holes. Our resident Charles Darwin adores everything science. He has even dabbled in the exciting young field of Eugenics. Thanks to a prestigious scholarship which we cannot pronounce or spell (and, yes, we are too lazy to figure out how), Hube is headed back to Berlin after graduation to help his native Germany back on its feet. Hopefully, no hard feelings, freund.

Fraternity: Phi Delta Theta

Insignia: Kings Crown Third Class Jester (1) Cribbage (3) Track (1) Glee Club (3)

His closest chums call him “Teddy Triangle” because he always has a few angles and “never more than one of them right.”

Teddy is a first-rate Anthropologist, Yet, he is an entrepreneur at heart. He has an eagle eye for the next big thing and with war behind us and smooth sailing as far as the eye can see, there are plenty of next big things for Teddy to spot on the horizon.

Attention Ladies, tie yourself to Teddy’s mast. He is going places.

self portraits

the locked door in the basement

by Caitlin Mayhugh art by Lily PacuitAcouple of months ago, I was enrolled in an inpatient adolescent behavioral health clinic. As the name suggests, the program took place entirely in the hospital.

Patients were not allowed to leave. Every week, we would have a session of family therapy which would then be followed up by a daily family visit.

Ironically, my first session was about communication and I remember virtually none of it. All I remember was the look on my parents’ faces as they watched me, unable to muster a response. Their eyes were red and puffy, making me feel guilty. If I had just been a “normal” kid, they wouldn’t have had to be in that room with me.

At our initial family visit, an argument broke out. Yet again, I can’t quite remember why. All I remember is a fight and storming out of the room sobbing.

Eventually, I ended up in “the quiet room,” a sterile little box of a room, just off of the common area. It was meant to be a therapeutic space but most of the time patients just used it to cry. The chairs were hard, the temperature was always a degree too cold, and the lights were blindingly bright.

One saving grace was the glazed windows which spared you the embarrassment of crying in front of the other kids. Nurses came in and out of the room, hovering over me and interrogating me. I remained completely nonverbal, shamefully holding my hands over my eyes like a dam for my tears.

The door opened again, but this time a much warmer face emerged. It was Nurse Hakim, my chess partner and fellow artist whom I had already confided in about a plethora of things. Religion, philosophy, drawing, writing, living with depression. Nothing was off the table

with him. We went back and forth for a little while, and I gradually recomposed myself to meet his calm tone. He opened up to me about his personal experiences with his mom. Finding out that we both had similar relationships with our mothers gave me a sense of comfort and mutual understanding. To comfort me, Nurse Hakim told me about his epiphany from earlier in his life:

“Death is like a locked door in your basement. Everyone has one, yet no one knows what's behind it. People are scared of the door in the basement. They’ve heard rumors about it sucking people in and never spitting them back out. But sometimes, something draws us to it, impulsive thoughts, an imposing world, or traumas that are out of our control, and we open the door. We see a darkness inside, an alluring yet forbidden comfort. It’s quiet, no one's there to bother you, not even your inner voice. But if you enter, the door will shut behind you, robbing you of your future and all those who love you.

“When we enter through this door we trade our lives for silence, for an eternal break from a tumultuous world. But in the act, we forget the opportunities each new day brings. People who survive their suicide attempts often report a feeling of overwhelming regret as soon as they realize the finality of their choice. We idealize death when we feel we have no other option, only to find its embrace deceitful and irreversible after taking the plunge.”

As these words poured into my ears, I savored each one like bites of chocolate cake. Until then, no one could explain what I saw in death, not even myself. For the first time in months, I felt sympathy for myself. I forgave my suicidality for what it was: a response to the pain of my stolen childhood. Every time

I acted on my intrusive thoughts, I blamed myself. I cut myself off from my friends because I was unworthy of love, I was self-harming because I couldn’t handle my flashbacks, and I would starve myself because I was “fat.”

But now, I understand that my mental illnesses were driving my actions. My depression told me I was not good enough, my trauma told me I was undeserving of love, and my anxiety told me it could never get better. Was it ever really my fault I wanted to die? Why should I be mad at myself for my suicidality? Wasn’t it me who confessed to my therapist when I began to plan my suicide? Wasn’t it me who asked my mom for therapy in the first place? I’ve always wanted help, it was never my fault I wanted to die.

Roughly a week later, I was allowed to go home. The doctors felt I had improved enough and I was no longer at high risk. But Hakim’s words always stuck with me, glued in my mind. I wanted to run, far, far away from that locked door. The same door whose knob I had nearly turned only weeks earlier.

I wanted to see another year, to continue making my art and celebrate the joy my friends and family bring me.

It’s not easy, of course, my intrusive thoughts will never go away, and of course, I will never be “normal.” But only now do I have the courage to stand tall amongst the torrent of challenges life has thrown my way. Nurse Hakim was a mentor to me, and although I miss talking to him, I’m glad I even had the chance. I don’t want to think about where I would be now if I hadn’t. I’m glad that the weight is gone from my shoulders, and that I have the fire to keep going. I’m glad that I can wholeheartedly say: I want to be alive.