Unravelling the History of the Panglong Treaty

Unravelling the History of the Panglong Treaty

Unravelling the History of the Panglong Treaty

Unravelling the History of the Panglong Treaty

© 2025 Sao Noan Oo (Nel Adams)

Published by Nel Adams

The rights of the author to be identified as the Author of this Work have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

The publishers cannot accept responsibility for errors or omissions, or for changes in the details given. The publishers urge the reader to use the information herein as a guide and to check details to their own satisfaction. Every effort has been made to check the information and ensure that descriptions and places are correct. However, we cannot be held responsible for any inaccuracies in the text.

ISBN: 978-1-5272-094?-?

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by Beamreach Book Printing (www.beamreachuk.co.uk)

Printed and bound by Beamreach Book Printing (www.beamreachuk.co.uk)

Sao Noan Oo

(Mrs Nel Adams)

Unravelling the Panglong Agreement is written in memory of the Shan, Kachin and Chin leaders, each representing their own state, who signed the Panglong Agreement with Bogyoke Aung San representing the Bamar State, called Burma Proper or Ministerial Burma on the Agreement, stating that they would join to form the Federal Union of Burma to ask Britain for independence.

Aung San, Sao Sam Htun, the Sao Hpa of Mong Pawn and six members of the 1947 Constitution Drafting Executive Committee were assassinated. Shan leaders were imprisoned without reason. Some died under suspicious circumstances, one disappeared after being taken to one of the military training camps, at Bahtoo Myo, while others were tortured to confess crimes they had not committed.

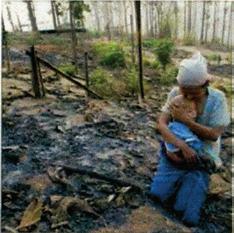

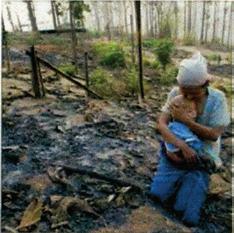

Last but not least, this book is dedicated to the memory of relatives and friends and all the men, women and innocent little children who suffered and died in the conflict and war caused by the successive Burmese Army/ political regimes who invaded and ruled over the Shan and other states illegally for the last three-quarters of a century.

It is dedicated to all Tai/Shans, especially the young men and women who one way or another fought for the survival of their ancestral homeland, for freedom and peace.

First and foremost my gratitude goes to my husband Brian for his support, and even more for the patience he has shown during the months when all my spare time was devoted to writing this book.

I would like to thank all family members and friends who have encouraged and supported me to write about the Panglong Treaty; although many knew about it, they did not know or understand fully what really happened. Most were not even born when the Panglong Agreement was signed.

I would like to thank Khun Hkuen Sai, founder of the Shan Herald Agency for News, for sparing his time to read and edit the manuscript and facts.

I thank Facebook for allowing me to use the platform to connect with relatives and friends; Microsoft for the window and many other uses; and Libra has been very helpful allowing me to use Open Office as a Word document and for pictures. Thanks are also due to Google for some informative articles written by academics and for articles on history etc., especially the Bill of Burma Independence, which I searched and found among its lists of information.

At last, my book, Unravelling the History of the Panglong Treaty will be printed. I am indebted to David Exley, of Beamreach book Printing, who kindly undertook to edit the script and print it for me in spite of the unforeseen situation I was in. Thank you, David, for your patience, understanding and help.

A few pictures were shared on Facebook; some are from my own collection and the rest, with her permission, are from Sao Sanda Simm’s book.

Sao Noan Oo (alias Mrs Nel Adams) was born in 1931, in the Shan State, a naturally beautiful area in north-east Burma. It was then a British colony but autonomously ruled by a number of local princes, called Sao Hpa or Sawbwas. Born into a Sao Hpa ruling family, her early life was interwoven into the geography, history and socio-political life of her country.

She was educated at St Agnes’ Convent in Kalaw and St Joseph’s Convent in Maymyo. At the University of Rangoon she obtained a BSc degree in Biology; a BSc (Hons.) in Zoology, with a thesis on the ‘Morphology and Taxonomy of Cestodes on Domestic Fowls’; and an MSc with a thesis on the ‘Rhopalocera of Rangoon’.

As an advanced student she studied at University College London for one year but had to give up due to the trouble in Burma. She obtained a City & Guilds Certificate in Food Science at Liverpool College of Catering and Food Science.

Occupations

University of Rangoon: Demonstrator, Lecturing Demonstrator in Zoology, 1953–1959

In the UK:

Teacher at Long Eaton Grammar School, Derby Girls High School and Mackworth Secondary School, 1963–1970

Research Assistant under Dr Morrow Brown – researching the effects of pollen counts on hay fever sufferers – for a short time before moving to another teaching job...

Assistant Lecturer in Applied Science and Nutrition at Mid Cheshire College of Further Education, 1971–1979, after which she changed her career by becoming the proprietor of a bakery in Helsby, Cheshire.

Following retirement, she now lives with her husband in Sutton Weaver, a district of Runcorn.

She is the author of several other books:

My Vanished World, A True Story of a Shan Princess, which has been translated into Thai and Japanese.

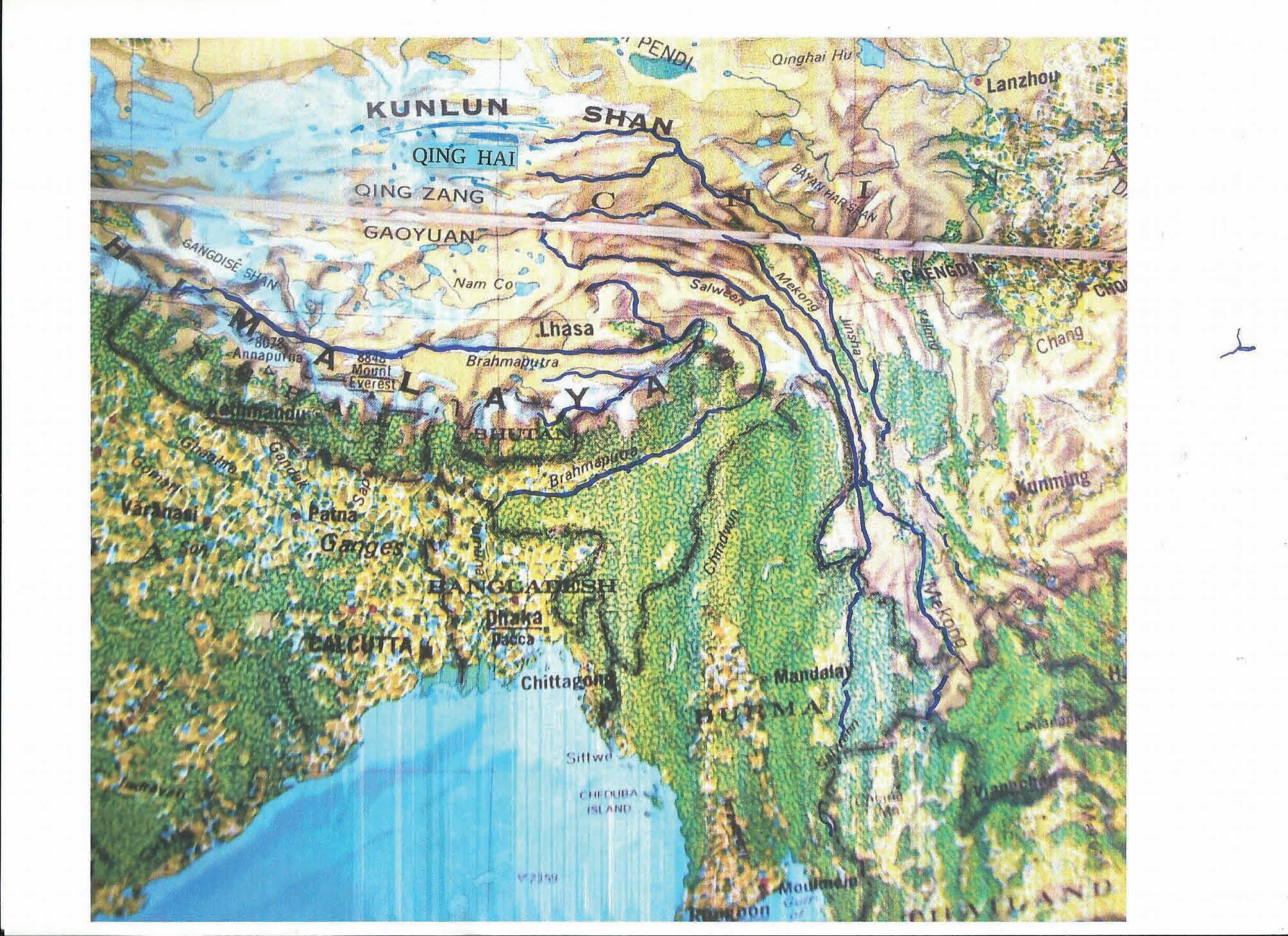

Unravelling the History of Tai Yai: A Subgroup of the Proto-Tai. The Tai people from Northern Asia, Mongolia, dispersed throughout China and settled in Yunnan. When the Mongols destroyed Yunnan, most migrated along the rivers into different parts of S.E. Asia, while the Tai Yai (Shan) subgroup settled on the Shan Plateau.

She is a campaigner (mostly in the form of writing) for the rights and freedom of her birth country, the Shan States and people.

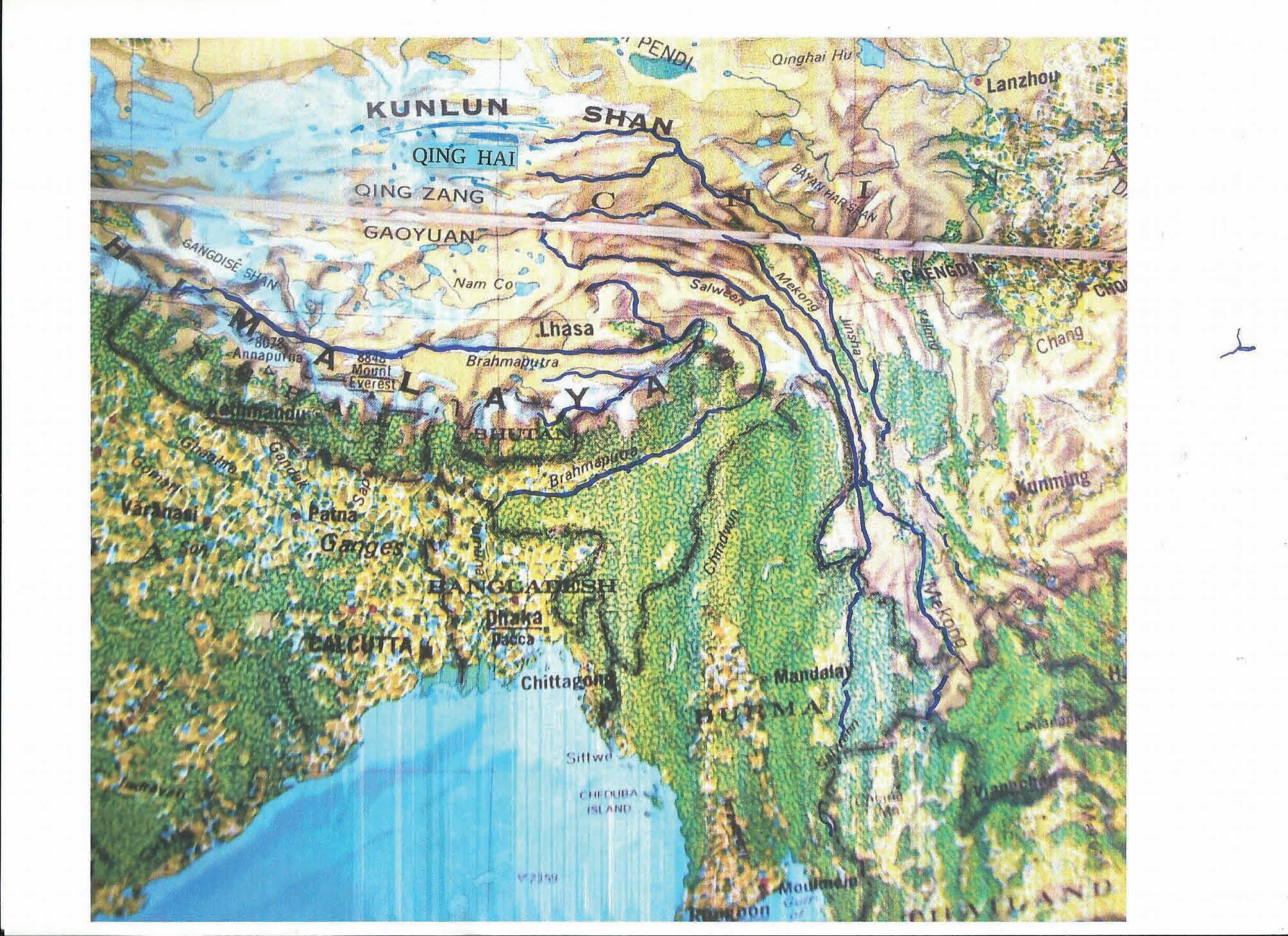

The geographical region called Burma (changed to Myanmar) consists of seven independent countries or states – Shan, Kachin, Chin, Kayah (or Karenni), Kayin, Rakhine (or Arakan) and Mon – together with the Burma heartland (Burma Proper or Ministerial Burma). The population of Burma Proper, as the British called it, were termed the majority, while those of other states were the minority.

Soon after the Japanese Occupation, we (Lawksawk Sao Hpa’s family) had just returned home after fleeing from being captured by the Japanese. We were excited to be home safe and sound, and thought that our life would now be quiet and normal again.

But this was not to be. The atmosphere and situation in the Shan States had altered. The political revolutionary turmoil going on in Burma Proper, where the majority of the ethnic Burmese lived, had penetrated into parts of the Shan States. They were campaigning for the British to leave the Shan States and the Sao Hpas to abdicate or change their hereditary feudal system of governing. A few of these Shan activists, having been to Rangoon or Mandalay Universities, came into contact with members of the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL) and under their influence and support also campaigned against the Sao Hpas. In the Shan States they called themselves the SSPFL (Shan States People’s Freedom League).

At the beginning of 1945 the Burmese nationalists in Burma Proper, after backing the Japanese against the British and realising they had bet on the wrong horse, turned against the Japanese and helped the British to drive them out of Burma. The 1944 Japanese Offensive into India through Manipur had failed, and by the end of 1945 Allied troops, led by Colonel Slim of the British Army, Regiment 14, had reopened the Burma Road and captured Myitkyina and Bhamo.

When the British arrived in Rangoon, the Burmans in Burma Proper were gripped by political tensions causing unrest. The different Burmese political organisations were fighting for supremacy. The AFPFL under the Japanese occupation had many branches all over the country; they were well organised and refused to accept the old politicians who came in with the British Administration from Simla. The British attitude was that the country should be fully rehabilitated before independence was granted. The Governor, Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, did not recognise the AFPFL as the government of Burma because the funds and arms were collected by political dacoity.

The Burmese were more advanced in politics than the Shan and other ethnic states, given better education, and by 1920 had more experience in self-governing under the British and the Japanese occupation. In contrast, the Shan, Kachin and Chin were kept insulated and they were content with their states being semi-autonomous with internal self-determination, and to live freely and simply with their own day-to-day lives. Some of their colleagues thought that Britain would protect them forever.

According to some observers, Aung San introduced himself to Colonel Slim as Commander of the Burma National Army [the BNA, previously the Burma Internal Army (BIA)], serving under a provisional government of the AFPFL. With his charismatic, bold and truthful character, Colonel Slim found he was an efficient leader with many followers and agreed to talk with him.

He told Colonel Slim that he was an Allied Commander who was ready to cooperate with the British as an equal but not as a subordinate. Colonel Slim replied that as far as he and the rest of the world were concerned there was only one government of Burma and that was 'His Majesty's Government', acting through the Supreme South-East Asia Command of Lord Mountbatten.

The Burmans claimed that Rangoon was taken by leaders of the AFPFL Government under Dr. Ba Maw, with the help of the BNA, while British

and American historians and authors claim that the British won the war with a small contribution from allied forces and that the claim made by the Burmese was a reconstruction of history by Burmese nationalists adopting inflated views of themselves, unwilling to accept the reality that they had made a mistake in their judgement when they joined the Japanese to fight against the British. The British Government in Burma would have arrested all AFPFL members but for the Attlee Government in London. It would not allow this because the AFPFL members had already filled almost all the Governor's Council and had virtually made themselves the Government in Burma Proper.

Britain had been badly bombed by the Germans during World War II, and the government had a big job ahead of it to put Britain back on its feet. Soon after the war it suited the British Government to get rid of all its colonies and grant them independence as soon as possible. To use force would only create another war and British soldiers had already been through a lot of fighting. Changes were happening very rapidly.

Prime Minster Attlee was now ready to accept anything. He stated, “We do not desire to retain within the Commonwealth and Empire any unwilling peoples. It is for the people of Burma to decide their future.” He invited Aung San and delegates to London.

Britain started decolonising and decided that Burma should be granted independence but had no policy regarding what to do with the Shan and Kayah (Karenni) States which had been accepted as semi-autonomous with their own by-laws and separate administration. The British were in a hurry to get rid of Burma and it seemed would readily throw the non-Burmese ethnic people, the Shan, Kachin and Chin and others, to the mercy of the wolves.

The Sao Hpas barely had time to settle down to a normal life or to think about State work when, through the initiative of Sao Shwe Thaike, Sao Hpa of Yawnghwe, Sao Hkun Kyi, Sao Hpa of Hsatung, and Sao Sam Htun, Sao Hpa of Mong Pawn, the three most active and prominent members, they were invited to attend a conference to be held in Panglong.

The First Panglong Conference was held in the small town of Panglong in Southern Shan States and opened on 26 March 1946, presided over by Khun Pan Sing, the Sao Hpa of Tawngpeng. As the Governor was ill and unable to attend, the Director of the Frontier Areas, Mr H.N.C. Stevenson, represented the British Government. Several guests from Chin, Kachin Burmese and Karens were invited to participate in the discussion concerning the future of the Frontier Areas. The Karens came to observe but did not wish to participate in the discussion as they were already discussing with the British in London. Among the most important Burmese delegates were U Tin Htut, U Saw and U Nu with their followers.

Mr Stevenson on behalf of the Governor opened the conference thus:

“The administration of the Frontier Areas would be under the direct control of the Governor as previously, and continue until the Frontier peoples themselves choose to join Burma Proper. The people of Burma Proper are most anxious to include the Shan States in a fully self-governing Burma and the people of the Shan States should give a serious consideration to the matter. The British Government hoped that the Shan States would one day join Burma Proper with acceptable agreements on both sides.

As regards to the internal administration, a state advisory council had been formed in every state, which we hoped would develop into

fully representative institutions in which the will of the people would be made known and brought to bear on the administration.

The Administration of the Frontier Areas had been reorganised; its top administrator was now in direct contact with the Governor, who is also in contact with the Residents. In place of the former Superintendents there would be a Resident and District Officers to train the state advisory councils to accept the responsibility of taking over different departments concerning local government, and develop into an efficient force.

In the effort of economic development, the Governor planned to carry out geological and agriculture surveys in all the Frontier Areas to find ways of increasing the national income and the capacity to pay for taxes to provide for hospitals, schools, travelling dispensaries and experiment centres for agriculture, forestry, and soil erosion and others.

On its part, the Frontier Areas Administration was considering a detailed plan for educational improvement in the Shan State, providing for technical as well as academic training. For adult education, the training of craftsmen for cottage industries needed attention and encouragement as increased production of minor village industries and improved marketing will increase income.

The state and regional councils should not be limited to political and administrative function, but should build centres for spreading and teaching cottage industries, with technical improvement as well as help to obtain patent rights. There was a need to develop and use to the full the natural self-reliance and inventive ingenuity which was the heritage of the Hill peoples. The aim should be to ask nothing from the administration that could be . To take part in the Burmese Constituent Assembly on a population basis, but no one to be affected in matters of a particular area without engagements of 2/3 of the majority votes of the Representatives of the area concerned

[… according to] one's own skill, brain and energy, so that evidence given would be tenfold valuable. Self-reliance is the real key to national resurgence and national progress.”

Mr Stevenson’s reading of the Governor’s message was followed by speeches from other delegates. The Kachin leader gave an interesting and important speech, while one of the Burmans, Thakin Nu (who later became the Prime Minister of the Federal Union of Burma), lashed out at the British, accusing them of separating the Frontier peoples from the Burmans. The Sao Hpas, Kachin and Chin leaders felt uneasy at this outburst; they thought it was bad taste and ill mannered, and they expressed their displeasure that Thakin Nu had gone too far.

In response to Thakin Nu’s accusation, Mr Stevenson replied:

“We are inclined to think that people who try to make unreal things real and to bluff the public are the ones who are responsible for misunderstanding, suspicion and discord found to be existing between the Frontier and the Burmese peoples. Now this is just one instance in a hundred. We could quote a thousand others. It is therefore an obvious fact – unless the Burmese leaders and people alike change their opinion about the Hill peoples and the treatment to be accorded them, there can be no hope of forming a real Federated Union of Burma.

On the other hand, if the Burmese will realise the situation and try to amend their past faults, we see no reason why there cannot be a real United Federated State of Burma. What we ask the Burmese to do is to be realistic and examine the facts. The British are our friends and their friends. They have done far more for Burma than the Burmese Government of old ever did and now they have promised the Burmese full self-government. We do not see there is anything to be gained by blaming the British for faults which lie in Burmese hearts.

On the whole, we are feeling much happier about the future. We realise the shape and size of the problems which face us and can see our way much more clearly. We realise too there is feeling of good fellowship in Burma only wanting to be released by wise leadership, and we hope that all the peoples of Burma, Burmese and Hill peoples alike, will find and support those wise leaders without delay.

For the Hill peoples the safe-guard of their hereditary rights, customs and religion are the most important factors. When the Burmese leaders are ready to see this is done and can prove how they genuinely regard the Hill peoples as real brothers equal in every sense to themselves, we shall be ready to consider the question of our entry into close relations with Burma as a free Dominion. In the mean time we hope the good work of brotherly co-operation will start at 'Panglong', and will continue under the auspices of United Burma Cultural Association, and we express our grateful thanks to the Shan Sao Hpas for giving the Hill peoples the historic gathering.”

U Saw, one of the Ex-Premiers, gave an elaborate detailed account of how the Frontier Areas and Ministerial Burma could work together as a united dominion. The people of the Frontier could be granted local autonomy and there would be no interference with their customs and religion. He would take the business and commerce from the British and other foreign firms and place this in the hands of the government-sponsored agencies, with profit to help farmers and cultivators. He thanked the Governor for allowing the Burmese leaders to state their case to the leaders of the Frontier Areas.

In response, Sao Khun Pan Sing complained about the misbehaviour of Dr. Ba Maw and his men towards the Shan when he was President. U Saw publicly apologised to the Shan people on behalf of the Burmans.

This 'First Panglong Conference' brought the Frontier leaders face to face with the Burmese politicians for the first time.

The Shan, Kachin and Chin discussed amongst themselves and decided to draft a manifesto declaring that in no circumstances would they at the moment federate with the Burmans, but instead they wished for selfgovernment on the dominion level in the Frontier Areas. The weak link was the Chin delegation, who felt that they were in no position to talk bluntly to the Burmans, because Chin State depended on Burma Proper for food, but they did not want a union with the Burmans if there was a way out.

The Chin, Kachin and Shan declared they would stick together as a single block, and each should not make a separate decision in the matter concerning the Burmans, prior to consulting amongst themselves. The Shans met often to discuss the future politics of the Shan States; the meeting brought together all the Sao Hpas, including administrators, community leaders, intellectuals and politicians, and leaders of the Kachin and Chin.

At the end of 1946, when the Governor, Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, was recalled to London, the Executive Council which was formed during the founding of the Federated Shan States in 1922 was abolished. In place of this the Sao Hpas formed their own executive council, consisting of 14 Sao Hpas and 14 representatives of the people, a first step towards democracy

Another important outcome of this period was the setting up of the Supreme Council of the United Hill Peoples (SCOUHP) to deal with the Burmese Power and politicians.

Sir Dorman-Smith was against the British hasty withdrawal. He wished to stick to the Simla White Paper drawn up by the British Government in exile. The Simla White Paper called for a period of rehabilitation and return to the 1935 Constitution, so that in time Burma could become an entity enjoying full equality with the dominions and with Britain

It was also stated that the Shan States and the other Frontier Areas would continue to stay under the rule of the Governor until they were ready to amalgamate with the Burmans. The popular wish of the Shan, Kachin

and Chin was that the British would favour their aspirations for selfgovernment under British protection, or even outright independence. There had been rumours that the British had encouraged the Shan Sao Hpas to oppose becoming part of the Union with Burma. There was also another story that the Shan were given a choice to either join with China, Thailand or Burma; of course this might be just wishful thinking on the part of the British Frontiers Administration and the Sao Hpas of the Shan States.

This conference was organised as a festival in the market town of Panglong, midway between Northern and Southern Shan States. Panglong was a town under the Sao Hpa, Laikha and Sao Noom, who offered to arrange and organise the conference site and the required facilities, and to provide the daily food and refreshments, as well as temporary accommodation (called 'Dawmaw' in Shan) for each of the Sao Hpa's family and guests. These houses were constructed of bamboo and straw, as they were cheap and easy to build as temporary huts. Banquet and conference halls, stages for entertainment and open market stalls for traders were also constructed with the same materials.

All the Sao Hpas arrived in Panglong on the morning of 6 February 1947 and settled in their respective Dawmaw. In the afternoon they gathered to discuss the funding of the festival, the reception, the timetable for lectures and intervals, and the food to be served in the banquet hall.

On 7 February offerings of food and robes were made to the monks, from whom the hosts and guests gathered to receive blessings, through prayers and chanting.

The 11 February 1947 was the day when the Tai/Shan selected their National Anthem and the National Day to be celebrated on 7 February of each year. The National Flag chosen was to have three horizontal bars of yellow, green and red, with a white round moon in the centre: the yellow

bar represented religion, the green the homeland, and the red courage, while the moon signified peace and harmony.

During the first few days of the Conference, the Sao Hpas and the Tai/ Shan discussed mainly domestic affairs like agriculture, forestry, mining, cottage industries, revenue, etc.

The Conference was attended by certain members of the Executive Council of the Governor of Burma, all the Sao Hpas, Representatives of the Shan People and leaders of the Chin and Kachin States. Aung San had returned from his negotiation with the Attlee Government just before the Panglong Conference was convened on 8 February. News spread all over the country that Burma was to be granted independence within a year. He brought with him the Aung San–Attlee document, which stated that:

“the Leaders and Representatives shall be asked either at the Panglong Conference to be held at the beginning of next month or at a special conference to be convened for purposes of expressing their views upon the formation of associating with the government of Burma which they think acceptable during the transitional period. After the Conference, His Majesty’s government and the government of Burma will agree upon the best method of advancing with the expressed views of the peoples of the Frontier Areas.”

The Sao Hpas and guests assembled in the Conference Hall to listen to Aung San’s speech. The Frontier leaders, who in the past had dissociated themselves and had had nothing to do with Burmese politicians or governments, were wary of Aung San and his colleagues' intentions.

But it seemed Aung San was unlike other Burmese politicians; he seemed clever and smart without any pomposity. He spoke bluntly and straight to the point. He admitted that the Frontier Areas did not have a square deal from Burma Proper, and in future the Government of Burma, with him as a leader, would give the Frontier peoples all the consideration they deserved.

1. He promised that the non-Burman Nationalities had the right to regain their freedom, independence and sovereign status because they were not the subject of any pre-colonial kingdom. He blamed the British 'divide and rule policy' for keeping the Frontier peoples from coming into contact with his Burmese brethren.

2. He said Burma Proper's independence without the Frontier peoples would be like curry without salt, and without independence the Frontier peoples would forever be in darkness. In any case, whether the Frontier Areas wanted independence or not, Burma would go ahead with it.

3. If the Frontier Areas should decide to associate with Burma's demand for independence, they would never regret it. His exact words were: “If Burma receives one kyat, you will also get one kyat”.

4. To prove his sincerity he promised to ask the Governor to appoint immediately a Shan counsellor, assisted by two deputies, and one Kachin and one Chin to sit on the Governor's Council to manage the affairs of the Frontier Areas while the terms for independence of Burma Proper and the Frontier Areas were being discussed, before they become finalised.

5. Should Burma Proper and the Frontier Areas become 'Pyidaung Su' (a Federation), the first President would be a Shan. Frontier Areas would sooner or later have to depend on themselves; therefore unity with Burma was essential, as the standard of living could be raised to a reasonable level after independence.

6. The Hill peoples would be allowed to administer their own areas in the way they pleased, and the Burmese would not interfere in their internal administration.

7. The Shan had the same right to choose their own constitution if they so wished. Burma would never interfere in their affairs.

At the Conference there were very loud noises, shouting and thumping on the table. From our Dawmaw next to the Conference Hall we could hear clearly what was being said and the angry shouting of 'Out, out British, out!' by some Burmese politicians, followed by loud applause. Outside the Conference Hall was a demonstration by Burmese who came in bus-loads from the plains to influence the Shan activists against the British and Sao Hpas.

Out of the SCOUHP a sub-Committee of six members consisting of two Shans (U Kya Bu and the Sao Hpa of Mong Pawn), two Kachins (Sinwa Naw and Zau Lawn) and two Chins (U Hlur Hmung and U Thaung Za Khup) was chosen to negotiate with the Burmese leaders, and having concluded their negotiation with the Burmans they drafted the document of the ‘Panglong Agreement’, as set out below:

“A conference having been held at Panglong, attended by Members of the Executive Council of the Governor of Burma, all Sao Hpas and representatives of the Shan States, the Kachin and the Chin Hills, decided that freedom would be more speedily achieved by their immediate cooperation with the Burmese interim Government, have accordingly agreed as follows:

i. A representative of the Hill peoples, selected by the Governor shall be appointed a Counselor to the Governor to deal with the Frontier Areas.

ii. The said Counselor shall also be appointed a member of the Governor's Executive Council and given the executive authority to discuss on the subject of Defense and other External Affairs. The Sao Hpa of Mong Pawn was elected to be the Counselor.

iii. The said Counselor shall be assisted by two Deputy Counselors.

iv. While the Counselor in his capacity of Member of the Executive Council will be the only representative of the Frontier Areas on the Council, the Deputy Counselors shall be entitled to attend

meetings of the Council when subjects concerning the Frontier Areas are discussed.

v. Although the Governor’s Executive Council will be augmented as agreed above, it will not operate in manners that would deprive the Frontier Areas of the autonomy which they now enjoy in their internal administration; they should have the right of full autonomy.

vi. The separating Kachin State within a Unified Burma is to be relegated by decision by the Constituent Assembly. It is agreed that such a State is desirable.

vii. Citizens of the Frontier Areas shall enjoy equal rights and privileges which are fundamental in democratic countries.

viii. The financial autonomy now vested in the Federated Shan States should be continued as before.

ix. The financial assistance which the Kachin Hills and the Chin Hills are entitled to receive from the revenues of Burma also is to be continued.

x. The Shan and Karenni will have the right to secede any time after independence.”

Near the end of the two-week conference, the Sao Hpas and the other Frontier leaders, led by the three most active and influential Sao Hpas, acknowledged that Aung San seemed honest and genuine enough and decided that they would cooperate with the Burmans as joint partners and together ask Britain for independence.

Thus, on 12 February 1947, on behalf of the Burmese Government and People of Burma Proper or Ministerial Burma, Aung San signed the Panglong Agreement (agreeing the above ten clauses), with an understanding that the peoples of the Frontier states and the three independent ethnic nations of the Shan, Kachin and Chin States would federally join with the people of Burma Proper State to ask Britain for independence.

The Shan Committee

Hkun Pan Sing, Sao Hpa of Tawngpeng

Sao Shwe Thaike, Yawnghwe

Sao Hom Hpa, North Hsenwi

Sao Num, Laihka

Sao Sam Htun, Mong Pawn

Sao Htun Aye, Hsamongkham

Maung Pyu, representing the Sao Hpa of Hsatung

Hkun Hpung

Tin Aye

Htun Myint

U Kya Bu

Hkun Saw

Sao Yape Hpa

Hkun Saw

Hkun Htee

The Kachin Committee

Sinwa Naw, Myitkyina

Zau Rip do

Dinra Tang do

Zau La, Bhamo

Zau Lawn do

Labang Grong do

The Chin Committee

U Hlur Hmung, ATM, I.D.S.M, B.E.M., Falam, Chin Hills

U Thawng ZA Khup, Tiddim

U Kio Mang, ATM, Haka

With the sudden removal of British power in the Shan States on 21 April, the Shans formed the Shan States Council:

1. It shall be called the Shan States Council.

2. Members should be equally represented in the council: 33 Sao Hpas and 33 popularly nominated peoples’ representatives.

3. For immediate purposes the representatives of the people shall be nominated on an intellectual basis, but election on the population shall be according to the normal rule of election.

4. The nomination of people’s representatives shall be left to the present representatives with power to call in for advice and assistance anybody genuinely interested in the welfare of the Shan States.

5. The council shall be vested with the following powers: (a) Legislative, (b) Executive, and (c) Financial.

6. An executive committee consisting of eight members, four Sao Hpas and four peoples’ representatives, shall be selected within the Council to be in charge of all the departments in the Shan States.

7. The present Executive Committee of the Council of the Shan States together with two representatives of the people shall

carry on the work until such time as the Shan States Council and its executives come into existence as contemplated.

8. The Shan States Federal fund shall be revived and placed within the sole financial control of the Executive Committee.

9. In addition to the above, the Shan States should have a separate High Court within the Shan States.

10. Subjects that cannot be dealt with by the Shan States individually are defence, foreign and external affairs, railway, post and telegraph, and coinage and currency.

Taunggyi, 15 February 1947

The Frontier Areas Committee of Enquiry (FACE) was set up as required by the UK Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, to enquire about the Frontiers peoples’ views on what they would require when they cooperated with the people of Burma Proper to form the Union of Burma.

Members of the Committee were as follows:

Chairman:

Mr D.R. Rees-Williams, Labour M.P.

Burma members:

The Hon. U Tin Tut, C.B.E., Member without portfolio of the Executive Council

Frontier Areas members:

The Hon. Sawbwa of Mong Pawn (Shan), Counsellor to H.E. the Governor for the Frontier Areas, and Officers

Members of the Executive Council:

Thakin Nu, Vice-President, AFPFL

Sima Hsinwa Nawng (Kachin), Deputy Counsellor

U Khin Maung Gale, AFPFL

U Vum Ko Hau (Chin), Deputy Counsellor

Saw Sankey, Karen National Union

Mr W.B.J. Ledwidge, Burma Office, Secretariat

U Tun Pe, B.Fr.S., Joint Secretary

Major Shan Lone, O.B.E., M.C., B.Fr.S., Assistant Secretary

Saw Myint Thein, Karen Youth Organization, joined the Committee when it moved to Maymyo, in place of the Hon. U Kyaw Nyein

The Committee started conducting their enquiry in Rangoon but later moved to Maymyo, where several Shan leaders and representatives and witnesses were present. The enquiries were long but seemed very thorough.

The first to be interviewed by the Chairman was Sao Shwe Thaike, President of SCOUHP. The Chairman read out the memorandum and presented to FACE:

1. Leaders and Representatives of the Hill peoples, selected to the Constituent Assembly to be nominated by the Provincial Councils proportionately on intellectual basis irrespective of race, creed or religion.

2. To take part in the Burmese Constituent Assembly on a population basis, but no decision to be effected in matters of a particular area without engagements of 2/3 of the majority votes of the Representatives of the area concerned.

3. To take part in the Burmese Constituent Assembly on a population basis, but no decision to be effected in matters of a particular area without engagements of 2/3 of the majority votes of the Representatives of the area concerned.

(i) Equal rights for all.

(ii) Full autonomy for all Representatives of Hill areas.

(iii) Right of secession from Burma Proper after attaining Freedom.

4. It is resolved due provision shall be made in the future Burmese Constitution that no diplomatic engagement or appointment be made prior to consultation with the Hill States.

5. In the case of common subjects, external defence, telecommunications, railways, coinage, etc., no decision shall be made without the prior consent of the majority of the Hill States irrespective of Burmese votes.

6. The provision shall be made in the Federated Union of Burma’s Constitution that any change, amendment or modification affecting the Hill States directly or indirectly shall not be made without a clear majority of 2/3 votes of the representatives of the Hill States.

7. When opinion differs on the interpretation of the terms in the Constitution of the Federal Burma the matter shall be referred for decision of the High Court consisting of the Chief and two other Justices.

8. The total number of Burmese members in the Federal Cabinet shall not exceed the total number of members of the Hill States.

The next task undertaken by FACE was to interview the representatives of each of the 33 states of the Shan States. In the Shan States where the population consisted of Shan or Tai as the majority, the requirements of the people were plain and simple as they were ready to abide by the decisions made by their leaders, as long as the Panglong Agreement and the Constitution that would be drafted by Aung San and the SCOUHP leaders were safeguarded.

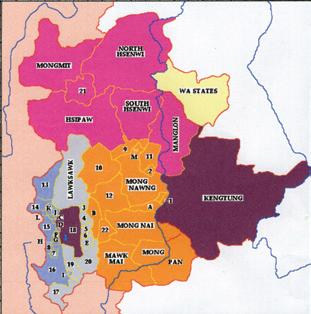

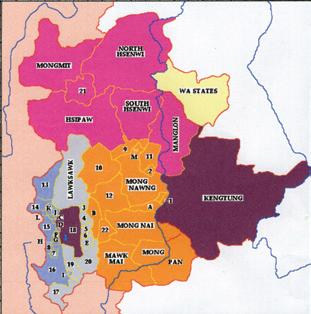

Kengtung; 2. Hsi Paw; 3. Mong Nai; 4. Yawnghwe; 5. Tawngpeng; 6. South Hsenwi (Mongyai); 7. North Hsenwi; 8. Mong Mit; 9. Mong Pai; 10. Lawksawk; 11. Lai Hka; 12. Mawk Mai; 13. Mong Pan; 14. Mong Pawn; 15. Mong Lurn; 16. Kanarawaddi; 17. Samka; 18. Mongkung Myosa; 19. Nawng Warn; 20. Mong Nawng; 21. Mong Sit; 22. Kehsi Man Sam; 23. Maw Nang; 24. Loilong (Panglawng); 25. Hsatung; 26. Wan Yein; 27. Ho Pong; 28. Nam Koke; 29. Sakoi; 30. Mong Su; 31. Keng Lun; 32. Baw Lake; 33. Hsamongkham; 34. Maw; 35. Pwela; 36. Pangtara; 37. Ywa-ngan; Pang Mi; and a few others were sub-states.

Notified areas:

All representatives for the notified areas wanted these notified areas to be returned to the state to which they originally belonged:

• Kalaw Rep (Ko Mya Tun) wanted Kalaw to be returned to its original state, Hsamongkham

• Taunggyi Rep (Ba San) wanted Taunggyi to be returned to Yawnghwe

• Loilem Rep wanted Loilem to be returned to Laikha

• Lashio Rep (Aung Nyunt) wanted Lashio to be returned to Hsipaw

Other areas:

Khamti Long and Sinkaling Khamti Awn, Kokang, Southern Wa and Northern Wa, and the Kachin Minority in the Shan States notified areas.

Khamti Long – according to the representative (U Aung Ba), the Shan formed the majority of the population, with Kachin coming second and a few Lisu. The majority of the population were Tai or Shan, but they had fled to Sinkaling Khamti and other regions when the Kachins caused trouble during their migration.

Thaungdut and Sinkaling Khamti (with U Balin as representative) was surrounded by upper the Chindwin district and mostly Burmese and Chins. Although the majority of the population was ethnic Shan, they had become Burmanised by adopting the Burmese language, but like the Shans they were ruled by Sao Hpas. These Shans were mostly from Khamti Long, who had escaped due to the trouble caused by the Kachins when they migrated along the Chindwin. The message of the people was: “We shall unite with Burma Proper Government but with equal rights and the same privileges as the Burmans. The Burma government shall continue to recognise our Sao Hpa to administer their respective states.”

Homalin also wanted to be a sub-state under the administration of Burma Proper, with the same equal rights and privileges as the Burmese.

Southern Wa (Naw Kham U, Chief Minister of Mong Lurn State; Mong Lurn was one of the 33 Federated Shan States) – the population consisted of more Wa than Shan. “We had been in the Federated Shan States and wish to remain as such and abide by the decision of the Shan States.”

Hsawng Long – the population consisted mainly of Wa and was governed by a British Resident and did not wish to federate with the Shan State.

Kokang (representative Yang Cheje) – Kokang was once a sub-state of Hsenwi. Here the population consisted of Chinese which was the majority, Palaung (Ta-ang), Shan, Chinese-Shan, Myaung, Kachin and Lisu. After the Japanese Occupation, Kokang became a separate state and would like to remain as such.

These enquiries were necessary to obtain a collective view of the people of the Frontier Areas. Since the committee conducted its inquiry after the signing of the Panglong Agreement, during March and April 1947, the evidence they heard was generally in favour of co-operation with Burma but under certain conditions, as stated by the leaders of SCOUHP in the list above.

The population in the Shan States consisted of Shan, Palaung (Ta-Ang), Taung Su (Pa-O), Kachin, Danu, Lisu and Kaw. In all the 33 Shan States the majority population was Shan or Tai. During the Sao Hpa and the British era the diverse people lived peacefully and harmoniously together side by side. They all agreed to follow the leaders of the Shan States Council.

In the FACE report, particularly the right of secession was a must for the Frontier Areas. This was opposed by some Burman nationalists, U Saw and Thakin Ba Sein, who earlier refused to sign the Aung San–Attlee Agreement. They accused Aung San of having given up Burman territories, and argued that the Frontier Areas were the creation of the British, by their

colonial ‘divide and rule’ policy. U Aung San dismissed this criticism as historically unfounded and politically unwise. He said, the “Right of Secession must be given, but it is our duty to work and show our sincerity so that they do not wish to leave”.

The above memorandum was presented by the Shan States to the Frontier Areas Commission, to be forwarded to the Attlee and other concerned Governments.

Almost all the recommendations provided by the FACE report have been expressed in the 1947 Constitution, indicating that the British and Burmese policy takes into account the desire of the minority peoples. These accepted recommendations include a federal government, a proposal for the geographical divisions of states and expectations for representation in parliament. The Committee also recommended that the secession policy be implemented in the Constitution.

Following the signing of the Panglong Agreement, the Constitution Drafting Executive Committee met to draw up the Constitution for the new Union of Burma on 9 June 1947.

It was led by Aung San, with Sao Sam Htun, the Sao Hpa of Mong Pawn, representing the SCOUHP States; Mahn Ba Khaing, a Karen politician; Thakin Mya, a Burmese Minister; U Ba Cho, Minister for Information; Abdul Razak, a Tamil Muslim, Minister for Education; U Ba Win, Aung San’s brother, Minister for Trade; Mahn Ba Khaing, a Karen politician, Minister for Industry; and Ohn Maung, Minister for Transport. (Sao Shwe Thaike should have been present with others but was absent due to illness.)

In keeping with his promise, the Constitution was based on the accepted principles of the Panglong Agreement: the Chin, Kachin and Shan States were separate equal states, each federating with Burma Proper with its own Constitution, controlling its own internal affairs. The right of secession was also drafted into the Union Constitution as “every state shall have the right to secede”.

In July there was a series of important constituent assembly gatherings of Burmese politicians. U Nu, who chaired the meetings, went to London to inform Prime Minister Attlee that at the assembly meeting members had

agreed that they desired to create an independent parliamentary government before the year’s end. The above Constituent Assembly which previously took place at Government House moved to the Secretariat Building where Aung San and his team convened to draft the Constitution for the future Independent Union of Burma.

During the recess Aung San carried out the daily business of drafting the Constitution. Five days into the meeting, he moved for a resolution that the new Constitution would describe an independent sovereign republic called the Union of Burma. To ease ethnic concerns, minority rights were assured and guidelines laid out for the establishment of autonomous states. Aung San gained from the Shan State leaders a constitutional commitment to remain 10 years within the Union, allowing enough time for the implementation of two 5-year national development projects.

On 19 July 1947, while Aung San and members of the Executive Committee were drafting the Constitution for the Federal Union of Burma, a group of terrorists entered the Secretariat in Rangoon and gunned down Aung San, Sao Sam Htun, Thakin Mya, U Ba Cho, Abdul Razak, U Ba Win, Mahn Ba Khaing and Ohn Maung.

U Saw, a prominent politician during the pre-war days and a Minister in the Ministerial Burma Government in the 1940s, was found guilty of masterminding the assassination and was hanged. He was one of the Bamar who did not agree with Aung San that the Shan and Karenni States be given the right of secession. He also did not sign the Aung San–Attlee Agreement that there should be a Frontier Areas Committee Enquiry into the Frontier peoples’ views on joining with Burma Proper.

The death of Aung San was a great shock to the Shan and other Frontier leaders; they had lost the only Burman who they could trust. After Aung San’s death, Governor Sir Hubert Rance appointed U Nu as Head of the Constituent Assembly to take over the job Aung San had left behind, including the drafting of the Constitution for the Federal Union of Burma.

Under U Nu, as a provisional Prime Minister, the Constitution was completed within 9 days, but what came out was nothing like the one Aung San had promised; it was contrary to it. According to Sao Hearn Hkam, Sao Shwe Thaike’s wife:

“there were gaping holes in the Constitution, [and] the new states lacked their own constitution, judicial and administrative structures. The large Karen territory was ill-defined, its fate and its borders entrusted to some sort of future referendum. Worse, the document contained no clear demarcation of federal and state powers. Finally, the role of Burma was confusing. The lowland plain region, which the colonialists called Burma Proper, was not listed among the states. ‘Burma’ referred to a mother government, around which revolved the states as satellites. The national government was given a veto over state laws. It was rather a curious arrangement for a federal nation. On the 24th September the Constitution was passed despite by its shortcomings. When the assembly gave its assent, the members raised their arms and cheered in victory.”

When questioned why the Constitution was contrary to the one Aung San was drafting, U Nu replied that they had to finish the Constitution within a certain time limit to take it to London to present to the UK Prime Minister, and that it was not perfect but could be amended in parliament after Independence.

There was no federal Government because all federal power was invested in the government of Burma Proper. Matters pertaining forests, minerals, oil, etc. were under Union restriction. Burma Proper was represented in the Upper House by 53, while the 5 component states were only 72 members, which meant unequal representation. The Upper House or Chamber of nationalities had no power to initiate a financial bill or reject such a bill passed by the Lower House or Chamber of Deputies.

Whatever the Constitution was, how unequal and unfair, and regardless of how they felt, the Shan and others did not raise any objections at the

framing of the Constitution because they were told this was an interim Constitution, and if changes were required they could be altered after Independence.

After Aung San’s death the Shan had to deal with a new less far-sighted group of Burmese politicians, U Nu, U Kyaw Nyein, U Ba Swe and others who were total strangers to them until 1946.

During the First Panglong Conference, soon after Independence, U Nu was confronted with unrest stirred by the communists and the People’s Volunteer Organisation (PVO), the AFPFL original army. Then came the Kuomintang (KMT; members of the Chinese nationalist movement) and civil war, which drove the whole country into chaos. Aung San understood federalism, but his successors U Nu and AFPFL members who were left to govern the new Independent Burma did not. The members of the Drafting Executive Committee who were assassinated with him and Sao Sam Htun were the country’s most experienced politicians.

Under these circumstances the replaced members’ imperfect document faced obstacles for breaching the Panglong Agreement and for altering the Constitution framed by Aung San and the Executive members.

Ref: The White Umbrella (pp. 185 and 186): a biography of Sao Hearn Hkam, the wife of Sao Shwe Thaike, the First President of Burma; also a member of Parliament at some stage, she narrated her story to the writer Patricia W. Elliott.

After the signing of the Independence Act between U Nu and Prime Minister Attlee in London, U Nu returned to Burma. He announced to the nation that Burma would be completely independent on 4 January 1948, with no detailed information of what had gone on in London between himself and the British government – with no mention of the Constitution that the British Attlee Government explicitly expected to be an important consideration in granting Burma’s independence. This was also shown in the letter Aung San brought back from the Attlee Government which stated that there had to be a FACE by a neutral person to ask the peoples of the Frontier and other ethnic areas to express their opinions on how they felt and what form of collaboration they wished to form with Burma Proper in their joint Independence. His Majesty’s Government could then decide the best way to go about it.

Before U Nu went to present the Constitution to the UK Prime Minister, when asked by some members of the Assembly members why the Constitution he had just completed was different from the one Aung San had promised, he answered that it was due to time limits to meet the deadline to present it to the UK Prime Minister and thus the Constitution was done in a hurry. This was an interim Constitution and it could be altered after Independence in January 1948. It seemed to the people of Burma, especially the ethnic minorities, that the UK Prime Minister had accepted U Nu’s Constitution, the faulty one, in favour of the Burmese

majority, with nothing to safeguard the rights of the other ethnic minorities, the Shan and other ethnic nationalities. They had the impression the UK Prime Minister had forsaken them and thrown them to the wolves.

The important players in bringing the Burmese, Shan and other ethnic states together at the Panglong Conference and asking Britain for independence were the Burman leader Bogyoke Aung San and among the Shan leaders Sao Shwe Thaike, Sao Hpa of Yawnghwe, Sao Sam Htun, Sao Hpa of Mong Pawn, and Sao Khun Kyi, Sao Hpa of Hsatung. Now unfortunately three of them were no longer alive to continue the work they had started. The only person alive was Sao Shwe Thaike, who was elected President of Burma and no longer available to be involved in the Union’s politics. Sao Khun Kyi passed away soon after the Panglong Agreement was signed.

The majority of Sao Hpas were never keen on joining with the Burmans, but after listening to the pros and cons of Aung San’s speech and the three Shan leaders who initiated the Panglong Conference’s explanation, all agreed to follow the leaders.

Since the early 1950s, Sao Hpas understood that the feudal system of government was not suitable for the modern world. They founded the Shan States Council, the first step towards democracy. The Council consisted of 33 Sao Hpas and 33 people representing the people, with an Executive Committee of four Sao Hpas and four people from the Council to be in charge of all departments in the Shan States’ interim Government. Such gradual changes were to meet the requirement of the people, taking democratic practices into consideration. As an ancient culture they were ready to take advice from intelligent Shan Elders, State Ministers, and Town and Village Headmen who were in contact with and chosen by town residents and villagers to be leaders by raising their hands.

The main aim of the Council was to lead the Shan State Government, but after Independence and U Nu’s new Constitution came into force, the Shan States Council and Government came under the legislation passed by the Union Government.

The Shan State was now headed by a Minister of the Union appointed by the President, to be called Head of State, in consultation with the Prime Minister and the Council. Many acts were passed, until the Shan State lost all the rights drafted in the 1947 Constitution: the legislative, executive and financial powers were in the hands of the Union Government, and the Shan States Government was unable to function properly. This was then followed by the Federal Movement and the military coup under Ne Win.

Soon after Independence, when U Nu became the Prime Minister of the Union of Burma, he was unprepared and inexperienced for the job that came with his status. Burma Proper, where the majority of the Burmese lived, was rife with different groups, each competing for power. The Burmese Communists broke away from the AFPFL and again divided into the Red Flag under Thakin Soe and the White Flag under Thakin Than Tun and set up armed bases along the borders of Shan States and China. At the same time, U Nu’s AFPFL own militia, the PVO, rebelled and supported the Communists. The 1st and 3rd Burma Battalions also rose against the U Nu government while the top Burmese Generals were busy weeding out non-Burmese officials: Indians and other non-Burmese ethnic nationals, the Karen, Kachin and Shan, including Anglo-Indians and Anglo-Burmese. The Burma Rifles left behind by the British were replaced by the Burmese Army, whose members were mainly people calling themselves Thakin, meaning the masters. All these people were from the Thirty Comrades rebels who formed the Burma Independence Army, trained by the Japanese to fight against the British and then joined the British to drive the Japanese out. The Burmese Army, after the first coup, changed its name to the ‘Tatmadaw’. The name and generals have changed several times but its doctrine and mind-set have not altered even today. It is the same Burmese military/political institution, an institution that has illegally ruled over

Burma for the last three-quarters of a century, causing conflict and war against the people of the other seven non-Burmese ethnic national states, using force, fear and terror and later using modern weapons to get what they wanted. The army usurped power from the States’ governments and hijacked their lands and resources. They committed various crimes against innocent citizens, including rape and murder, burning villages, ethnic cleansing and genocide.

Outside of Burma Proper, there were uprisings by the Arakans, and also armed insurrection by the Karen National Defence Organisation (KNDO) supported by the majority of Karens. In the Shan State too, a group of Kachins led by Captain Naw Hseng rebelled and Karen rebels and the Pa-O captured several towns in Northern Shan State. The Pa-O were allies of the military. Grievances of these groups were not directed against the Shan people but they wanted to show their bitter grievances against U Nu’s Central Government. While the Government under U Nu as well as the Shan State authorities were working to contain these elements, the KMT fleeing Mao’s Communist victory invaded the Shan States. The fleeing Chinese soldiers stretched along the borders which the Shan State shared with China: Laos and Chiang Rai (Thailand). During this period the Shan Sao Hpas and other SCOUHP members supported U Nu by providing both money and soldiers to the Central Government. The Shan Sao Hpas felt it was their duty to stabilise their country and to make the Union a success. By 1954 although 6 years of external threat had ended, peace did not follow. Eastern and some Northern Shan States had been placed under martial law by the then President, U Win Maung. The anti-Sao Hpa and the Pa-O secretly aided by the Burmese Army were rioting and robbing people of their possessions.

The first column of Burmese soldiers were dispatched into the countryside to disarm the population, search for hidden weapons and disrupt the alleged preparation for the Sao Hpas uprising. In the process, Headmen, important in village society, were tortured and alienated, put in prison, or taken away and disappeared without trace.

By 1953, the Sao Hpas realised that the ancient feudal system which had operated for the last thousand years was out of date and it would have to end and give way to democracy. With this in mind, they announced to the nation through the media that they would be giving up their power in the near future. They still had a lot of work to finish and felt it was their responsibility to see that things were in order before they surrender their power to the Shan State Government in Taunggyi, the capital of the Shan State.

The Burmese power establishment became more and more preoccupied and anxious about Chapter 10 of the Union’s Constitution, which provided the Shan and Karenni with the right to secede after a period of 10 years. This became a great issue for the Burmese Army, since it clashed with their ideas based on ‘one blood, one voice, one command’. To them, autonomy, federalism and equality were a lot of rubbish, tolerated only by Aung San.

With the end of 10 years approaching, the Burmese politicians and the army were convinced that the Shan would secede and others would follow. They became paranoid and convinced they must stop this happening, no matter how long and what it might take. Although according to the Constitution the Shan State had the right to secede, the Sao Hpas had at that time no intention of doing so.

To prevent secession, it became important to them to destroy the credibility, respectability, prestige and authority of the Sao Hpas – this was their rallying point against the Sao Hpas who were portrayed in the media, newspapers, magazines, journals and short stories as despotic, exploitative, disloyal and feudal, who acted and plotted with the KMT, opium warlords, Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) agents, American warmongers and British neo-colonialists to destroy the Union. Local anti-Sao Hpas politicians were given ample assistance by both the army and AFPFL leaders. This made the Sao Hpas and their families uncomfortable and to see their people joining the enemies to tarnish their reputation was hard to swallow when they, the majority of Sao Hpas, had governed with their conscience, as noted by British officers who had worked with them.

By the middle of the 1950s and early 1960s, the army under Ne Win had become powerful, with its own political party, the National Solidarity Association, with branches nationwide, run by psychological warfare, businesses, and industries departments. The Defence Service Institute was under Brigadier Aung Gyi and a parallel police apparatus by the dreaded Military Intelligence Service (MIS), controlled by Ne Win. In 1956, human rights violations by Burmese soldiers against Shan citizens in the Shan States became worse.

The anti-Sao Hpa campaigns did not turn out as the campaigners had hoped and there was a backlash. The majority of Shan citizens were conservativeminded farmers and small traders bound to ancient traditions. To them an attack on the Sao Hpas was an attack on Shan State autonomy and culture.

On 24 April 1959, the Sao Hpas surrendered their executive power to the Shan State Government. It was a momentous event for the Shan State post independence. It was the end of the Sao Hpas dynasty, although they still held their titles and remained Members of Parliament and were eligible to work in any department by going through the voting system. They were closely watched by Ne Win’s MIS. Some writers seem to think Ne Win ordered the Sao Hpas to resign and expected them to surrender their power to him, but the Sao Hpas did not. Instead, they surrendered their power voluntarily to the Shan State Government in the capital Taunggyi, where the British Government and the 33 Sao Hpas used to meet for the Durbar annual or bi-annual meetings.

There was a conference in Mongyai attended by some younger Sao Hpas. The Shan youths who felt that they had had enough of Burmese soldiers treating them worse than slaves decided they would form a resistance army, although they were all inexperienced in fighting. They chose Sao Yanda, also called Sao Noi, a native Tai from Mong Wan in Yunnan with some experience of fighting against the Japanese during World War II. On 21 May 1958, Sao Noi with 30 comrades held a solemn ceremony vowing to fight for Shan State independence and formed the first Tai Resistance Army, called Num Seuk Harn (the Young Warriors).

Although the younger generation of Sao Hpas were in favour of rebelling, the elders were not. They had signed a treaty for the Shan States to be a member state in the Federal Union of Burma and they felt committed to make the Union work. They thus tried to save the Panglong spirit just before the Ne Win era.

A conference was held in Taunggyi , where representatives of nonBurmese ethnic states attended, Shan, Kachin, Chin, Karen and Karenni and Mon. The meeting was about the Panglong Constitution which was framed at Panglong and drafted by Aung San, Sao Sam Htun and six other experienced executive members in July 1947.

1. This Constitution was said to contain several clauses to protect the other ethnic nationalities from some unethical persons.

2. After 13 years the condition in these states had not developed as it should because the present Union Constitution was contrary to what was agreed.

3. The Union was not a federal but a unitary one.

4. The States had not enjoyed equal rights because Burma Proper was not a state but was merged with the Union Government and had become one entity, with authority over other states.

5. The States were not autonomous, as all the executive, legislative and financial powers were vested in the Union Government.

The non-Bamar ethnic nationalities felt it was time to restructure the Constitution and have a discussion with U Nu.

Members of the above-mentioned together formed the ‘Inter-States Unity Organisation’ to explain to the Burmese politicians that they were asking for an amendment of the Constitution to be in line with the one Aung San and the SCOUHP representatives had framed.

After all the arguments and wrangling, troublemakers who hated the Sao Hpas so much made another attempt to destroy the Sao Hpas’ reputation, even after they had surrendered power. Unwillingly, U Nu decided to allow the Inter-States Unity Organisation to present their grievances in parliament.

After a long introduction and explaining the topic to be discussed, U Nu continued:

“Our present discussion must be a family discussion. Each of you Gentlemen and each of us who are members of our Union family must put all our views on the table. Of course there will be differences. To ensure benefit for ourselves, our children and our Union we will negotiate till we reach an agreement that will resolve these differences.

On the objectives of discussion, we wish to seek hand in hand with you Gentlemen the best way of ensuring stability, preservation of the Independence and our democracy.

In seeking the best way of preserving our Union, Independence and Democracy I would like to call both the people of Burma Proper and that the States whatever we are seeking it must be according to the principles of ‘Loka Pala’, meaning justice, independence and equality. Let us all try our utmost that our Sovereign independent Union does not revert to the extremely ugly status of a vassal state or slave state.”

Several ethnic leaders and government representatives attended. Sao Hkun Hkio, the Minister for Shan State, acted as Chairman and spoke on the Federal Principles:

Map of the Federal Union of Burma Burma (as agreed in the Panglong Agreement) but after independence there were only seven as Burma Proper was part of the Burmese Union Government which controlled power over the seven states.

Burma proper

State

State (Rakhine)

State

Federated Shan Sates (Seing Mong Tai)

Karenni State (Kaya)

Karen State

Federated Shan States

The 7th of February was chosen by the Shan Sao Hpas and the people's representatives of the Shan States in 1947 to make it the Shan National Day. It was to be a 'Remembrance Day' when the Shan State become independent from Britain as a sovereign nation in its own right. This was followed by the declaration of the Shan National Anthem and the Shan flag ..

Yellow is for religion (to most people it means Buddhism, because the buddhists are the majority in the Shan States) Green represents the green-ness of the countryside and agriculture. Red represents courage, bravery and resilience. The White Moon represents 'Peace', as the Shans are Peace-loving people.

But unfortunately, this was not to be, because our Leaders made a great mistake in trusting our next door neighbour when they signed a treaty with Ministerial Burma. Ministerial and the Shan, Kachin and Chin were to become co-founder of the Federal Union of Burma. But the latter three ethinc States were lied to, deceived and manipulated by not only the Barnar Ploiticians, but in 1962, the Barnar army invaded the Shan country, put the Leaders in prison, usurped power, and hijacked the homeland and resources. They treated citizens most inhumanely and subjected them to more than sixty years of fear and terror and heinous human rights violations including genocide.

After more than six decades of extreme suppression the Shan Peoples' sense of "national identity" and aspiration to be the master of their own country have not diminished but have grown stronger.

Lady and Sir Hubert Rance saying farwell to friends, Government House staff and Burmese staff. Taken after a farewell party in Rangoon for the couple leaving Burma for the UK. (1947: Samka Family Private Collection)

The Governor, Sir Hubert Rance and Sao Shwe Thaike, the first President of the newly formed Federal Union of Burma, on the 4th of January, 1948, at the declaration of Burma Independence.

Nine members of the Constitution Drafting Committee, U Aung San, Sao Sam Htun, Sao hpa of Mong Pawn, U Ba Cho, U Ba Win, Burmese Minister (Name unknown), Abdul Razak, Mahn Ba Kaing, Ohn , and Thakin Mya drafting the Constitution for the Federal Union of Burma to be presented to the UK Prime Minister, Clement Attlee before Burma Independence was granted. On the 19th of July, 194 7, while completing the work, a group of terrorists rushed into the room they were workingand gunned down the nine members one by one. Sao Hpa of Mong Pawn was taken to the Hospital and died there, while others died instantly.

Members of the Executive committee of the interim Shan Government. The Sao Hpas (Ruling Princess) of the Shan States.

Shan chieftians pose for a photo at the 1946 Panglong in Shan State

Sao Hpas (Ruling Princess) of the Federated Shan States at the first Panglong Conference, including U Nu (Chairman of Burmese Party) and his followers came to watch.

“The Union of Burma came into being at the Conference in Panglong, Southern Shan States in 1947 through a signed Treaty between the Leader of Burma Proper, Bogyoke Aung San, representing the Bamar people and the Leaders of the Shan, Kachin and Chin, each representing their own State. The treaty was based on three major principles: equal rights and status; full internal autonomy for the Frontier States; and the right to secede at any time after independence.

After the Panglong was signed, witnesses testified before the Frontier Areas Committee of Enquiry (FACE) as required by the Attlee British Government, through a letter sent with Aung San so that the Union members would be aware of the main requirements of people of the Frontier Areas when Burma Proper became independent.

The flaw of U Nu’s Constitution was a plan to form Burma into a Unitary Union, instead of a multilateral one. The executive, legislative and financial powers were taken away from individual states and were vested in the Central Government of which Burma Proper was merged instead of the latter being one of the states.

In the Panglong Constitution, Burma adopted the principles of pluralism in which all the different diverse racial and religious groups would live together in peace and harmony, but in the present Constitution, Buddhism was made the Union's religion, disregarding the feelings of Chins, Kachins, Karens and other Christians.

We have come to realise that we have not been given the power to work to the full development of our states. The Union instead of representing all the states is representing only the Bamar state, known as Burma Proper. The Shan and Karenni States formed Constituent States but Burma Proper did not.”

On the question of why not reject the Constitution when it was first announced, Sao Hkun Hkio answered:

“the political situation at that time was very confused, the whole Nation was mourning the assassination of Aung San and other Leaders. The struggle for independence had been overshadowed by sorrow and the series of trouble, chaos and instability that followed. After Independence, the people in the states were inspired and were looking forward to jointly working within the Union towards development and progress.

But after 14 years of Independence we have come to realise that we have not been given the power to work to the utmost for the development of our states.

If the spirit of the Panglong Agreement and the directives of General Aung San concerning the equality of all constituent states had been observed in implementing the Union Constitution, the Union Government would be one that represented all states.

Instead of forming a state for Burma Proper, the authorities had decided to make the Union Government as the government of Burma Proper, making the power of the Union and that of Burma Proper as one and the same unit, Burma Proper overlording over other states. The Union being constituted as such would not promote national unity, nor a union of equality.

Comparing the preamble of the present Constitution of the Union of Burma with the Preamble of which it is supposed to be drawn from shows many inconsistencies. In section 222 of the Constitution, Burma Proper is a constituent unit like all other states, but in Section 8 it has the unique privilege to use the Union power.

Such prejudices and inequality have upset and caused great grievances to other ethnic nationalities.

The Union of Burma would be a true Federal Union by:

1. establishing Burma Proper as one of the constituent states;

2. granting of equal powers to the two chambers of Parliament;

3. sending equal numbers of representative from each state to the Chamber of Nationalities;

4. the voluntary granting of certain restricted power to the Union Government and by the states retaining powers agreed at Panglong.”

Duwa Zau Lawn from the Kachin State, Captain Mang Tung Nung from the Chin State, and U Htun Myint from the Shan State spoke in support of Sao Hkun Hkio.

Thakin Chit Maung, on behalf of the National United Front (NUF), opened his speech by saying:

“National races are dissatisfied and the Burmese are also dissatisfied in their own way and no longer can retain their grievances. If the causes of these differences should be tackled first, I believe that the call for the Constitution federal arose out of the general feeling of dissatisfaction. The basis of our dissatisfaction and distrust of one another did not arise recently. It is an evil that accumulated [over] many years, it started from the days of feudalism and colonialism. It is important for us to draw the conclusion that the problem is due to the manipulation of the feudalists and colonialists, in the old as well as the new form, whose policy is to sow seeds of dissension among our natural races, so that we will hate each other like enemies.”

He continued to blame the British:

“Mr Churchill and his henchmen have within a few months of independence [been] able to foment insurgency in all parts of Burma. Since then the nation has lost sight of the enemy and had started to look upon one another as enemy.”

He then turned the blame on U Nu:

“The AFPFL Government was responsible for the 10 years of turbulence during the 10 years insurgency. The government, unable to distinguish between real friends and real enemies, used drastic single-party authoritarian military method to suppress dissidents.

NUF’s view of the Constitution was that the Union of Burma was a Federal Union formed by constituent states, with Burma Proper as a nucleus. In fighting for Independence, the Bamar had always led.

In view of the present situation, internal as well as external, our country will be more like a confederation if we adopt the true federal principle and this will steadily lead to disintegration of the Union.

We acknowledge that during the 13 years after Independence our people in the States as well as in the Union have suffered due to imperialistic machines as well as from misguided actions of our government. We sympathise with the people and every effort must be made to amend the constitution so as to remove the flaws that have led to such suffering, but the amendment must be within the framework of the present constitution.

If we want a Federalism true in form and essence, we must wait until we can march towards a goal of creating a Socialist Republic of Burma.”

U Ba Swe, representing AFPFL views, stated:

“Historically, Chin, Kachin, Kayin, Mon, Kayah, Arakan, Shan and Bamar are a family of national races who had lived in close relationship in the same country. So the question might be asked, why was the sovereign state developed on a federal and not on a unitary [basis] after independence? The answer is clear: our family

had lived under the British colonial rule, quite literally divided. We were not only physically divided but also by policy encouraged to distrust and suspect one another. When we are together and formed a new state we are like strangers. We created a Federal State although we were inclined towards a unitary one. Many nations in the world started with a federal union and had progress but later moved towards a unitary one. I am ready to accept for Burma Proper to form a state, but I do not believe that it is logical. Therefore, I would like to urge Burma Proper not to be made into a state but remain under direct control of the Central Government. It is larger and more highly developed than other states and could assist in developing the underdeveloped states. If Burma Proper was to be one of the states, it would not be able to lead and could become selfish and make the union government ineffective. If there should be any misunderstanding it should be solved within the family and with family spirit.”

Dr. E Maung spoke on behalf of U Nu’s Union Government:

“The Union Party in view of its objective to promote democracy and stability of the Union cannot accept the proposal known as the Federal principle put forward by the Chairman of the States Unity Organisation because:

a. It differs radically from the principles embodied in the Constitution of the Union of Burma, as laid down with wisdom and foresight by General Aung San and leaders from Burma Proper and from the states.

b. It contains elements opposed to the principles of democracy the leaders of Burma Proper and of the states, in their wisdom, had wished to nurture and promote.

c. It contains elements that could lead to the breaking up of the Union, and is [against] the concept of promoting stability and durability of the Union, desired by General Aung San and leaders of Burma Proper.

d. The Union is already doing its utmost in a family spirit to assist the states wherever it was appropriate.”

All members of the political Institute were unwilling to compromise on the amendment of U Nu’s Union Constitution as requested by the Inter-States Unity Organisation led by the Sao Hpa of Mong Mit. All the Burmese political parties blamed everything that was going wrong on the British colonialists and the Tai Sao Hpas’ feudalism.

The second day of the National Conference of the Federal Principles came to an end. The army unit from Mingaladon entered Rangoon at midnight, and on 2 March 1962 they had occupied all government departments. The army arrested ministers of the Union Government, the President, the Chief Justice, Heads of Constituent States and all the Sao Hpas. Guarded by soldiers with guns, they were sent to prison for 6 years and on house arrest in Rangoon for the rest of their lives.

When the seven states of Shan, Kayin, Kachin, Chin, Mon, Karenni and Arakan called for constitutional reform, Ne Win and his army took it as a threat to national unity. Even U Nu was not spared, based on their suspicion that he was giving in to the Shan and other minorities. Ne Win seized power and staged a coup d’état and became a general whose ruthless rule bankrupted Burma’s economy during his 26-year rule.

It was the first military coup authorised by Ne Win, and this was the end of freedom and the beginning of hell for all the non-Burmese ethnic nationalities – a life of fear and terror, fear of being killed, imprisoned, tortured, raped, killed or murdered individually or in groups.

Under Ne Win, the Shan States were completely cut off from the outside world, with a large part made into a 'no go' zone for foreign journalists, while his officers and soldiers committed crimes against Shan citizens

behind closed doors. The Shan States became a dark dungeon, in which the people were imprisoned in their own homeland, movement was restricted, and people in one side of the country did not know what was going on in the other side. The Shan population lived in fear and terror every day of their lives. This went on for decades and has never stopped.

Countless people amongst the educated and elite who were able to flee secretly through the jungle from their homeland/country left everything behind. Most used Thailand as a temporary refuge, and later went to America, the UK, Canada, Australia, France and Germany, wherever they could find work.

In 1982, while guerrilla insurgencies mounted, Ne Win relinquished the Presidency of his political Burma Socialist Programme Party (the BSPP) and transferred the party to San Yu. In 1988, in the Burma heartland there was a huge uprising, led by university students, which spread to the whole of Burma, including the Shan States. Many thousands of people were killed.