glowyro1870I1922,arloeswrUndebau

A Glimpse of MABON A Glimpse of MABON A

Proud Welshman, Politician for the Rhondda and President of the Miners of South Wales

SantSteffan.O’rdiweddlluniodduno

ynSaesnegiddoynydyfodolagos.Ceir dadansoddiadmanwlohonogydag

ydosbarthgweithiolam37mlyneddadodyn arweinyddgrymusglowyrCymru,Prydain, Ewropa’rUnolDaleithiau.ICymryalltudyr AmerignidoeddunCymroi’wgymharuagef achafoddgroesotywysogaidyddaudroybu yndarlithioaphregethuyno.EfoeddLlywydd cyntafFfederasiwnGlowyrDeCymruyn1898 aceriddogolliychydigo’iawdurdoderbyn 1912,nicholloddeiddylanwadaruthrolyny meysyddglohydeianadlolafDisgybl

A Valuable Biography on Mabon

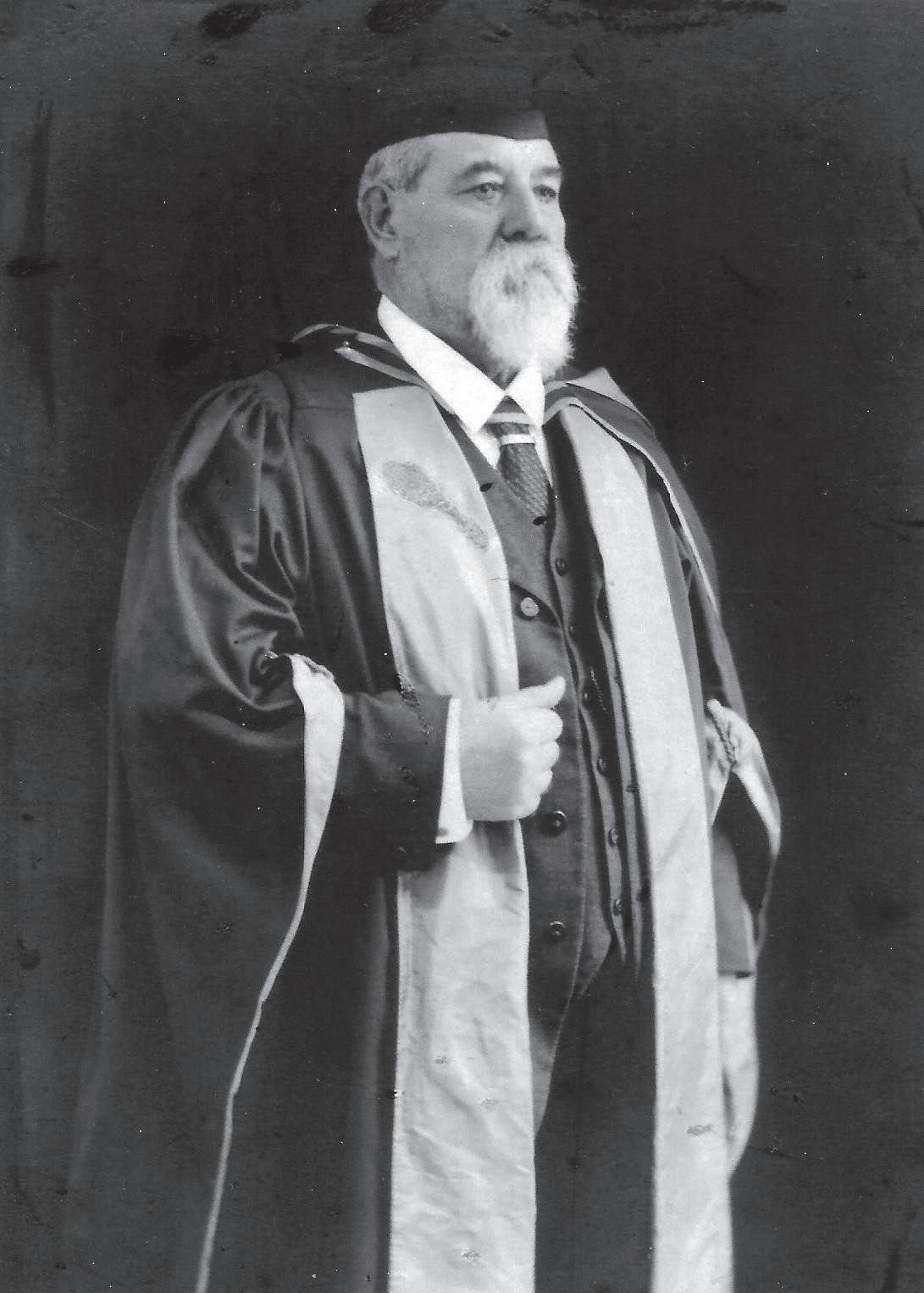

Dr. D. Ben Rees, a Liverpool-based Welsh historian, was the first biographer in the Welsh language of William Abraham (1842–1922), better known as Mabon, a famous trade unionist, parliamentarian, journalist, eisteddfodwr, and Liberal-Labour leader.

Mabon served as the MP for the Rhondda from 1885 and joined the Labour Party in 1908. The first biography of Mabon in English, written by Dr. E.W. Evans, appeared 65 years ago. After such a long period, it needed to be analysed by one of the most remarkable historians of his generation, Reverend Dr. D. Ben Rees, author of biographies in both Welsh and English on devolutionists such as Jim Griffiths, Gwilym-Prys Davies, Cledwyn Hughes, and Aneurin Bevan. Dr. Rees also wrote a study in English on Bessie Braddock, as well as a biography in Welsh 54 years ago on Mahatma Gandhi, alongside numerous works on Welsh missionaries who served in Northeast India.

W.E.GladstoneaDavidLloydGeorgeacnid KeirHardieaNoahAblettydoedd,prifddyny Lib-Labhyd1909,ganiddoyradeghonno orfodwisgolliwiau’rBlaidLafur.Ymae’rgyfrol honyngyflwyniadteg,difyroddyntlawda ddaethyngysurusogyfoethogonda gadwoddynffyddloni’wddelfrydau,iei’r iaithGymraeg,i’rcapelMethodusa’rlofayn mhobdosbartho’rDe,i’wrienia’ideulu,ei brioda’rplantagafoddygofalgorau.

His latest book, on the history of the Labour Party in Wales, will be published in October 2024 and will mark the 99th book with which he has been involved. Titled Cyd-ddyheu a’i Cododd Hi: Hanes y Blaid Lafur yng Nghymru, this new work is another valuable contribution to our understanding of Welsh politics.

GeralltPennantaDBReesynPennyLane

Glimpse of MABON

Proud Welshman, Politician for the Rhondda and President of the Miners of South Wales

Cynlluniwydyclawrgan SionWynMorris,GogleddLerpwl

Ben Rees

A Glimpse of MABON

First published in 2025 by Modern Welsh Publications

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted by any means without the prior permission of the publisher.

© D. Ben Rees 2025

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work as being asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-7393373-7-7

Typeset by www.beamreacuk.co.uk

A Glimpse of MABON

Proud Welshman, Politician for the Rhondda and President of the Miners of South Wales

D. Ben Rees

Modern Welsh Publications

PREFACE

to William Abraham (1842 – 1922)

I was absolutely thrilled to be the first historian to write a biography in the Welsh language on the remarkable Mabon who dominated most of Victorian and Edwardian Wales. A native of the village of Cwmafan, near Port Talbot, he began his life in a small cottage cared for by a pious mother. He lost his father when he was young and depended so much on the activities that took place in his chapel called Tabernacle. Denied secondary education, he left for the local coal mine where he began at an early age to organise his fellow workers. He was given an abundance of opportunities by his minister and elders as a precentor and within the Band of Hope weekly meeting with the children as well as the Sunday School.

The Eisteddfod Movement attracted him as a young miner. That is why William Abraham became known as Mabon. He was versatile, he could sing and write essays which gained him prizes. Mabon was given responsibility within the Eisteddfodic circles as an adjudicator and a compère. He had a delightful but powerful tenor voice which assisted him immensely. His rendering of hymns and the Welsh National Anthem used to quell any undue rebellion in the trade union circles. A proud Welshman, he cherished his language and had his opportunity to support the first Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg (Welsh Language Society) at the National Eisteddfod in Aberdare in 1885.

That was an important year for him for he became the Member of Parliament for the Rhondda, the name of the constituency which encompassed the two valleys (Rhondda Fach and Rhondda Fawr). Mabon came there at the heyday of the Welsh coal industry in the period between 1875 and 1920. He witnessed the colossal sociological change in the once remote and sylvan valleys which became the centre of the steam-coal trade. Mabon was himself an incomer like the majority who flocked to the collieries that dominated the landscape. By 1913, fifty-three large collieries employed 42,000 men to dig nine and a half million tons of coal, or one sixth of the maximum output of the South Wales coalfield. Mabon settled in the valleys when he came to be a miners’ agent at Pentre, a

rather forgotten village compared with the more militant township of Tonypandy in the Rhondda Fawr or Ferndale and Mardy in the Rhondda Fach.

A staunch Liberal all his life, like so many of the inhabitants, he straddled the two camps, the Liberals and the Labour Party and became like so many miners’ leaders in England a very well-known Lib-Lab. His huge physique, his brilliant oratory and his identification with progressive measures endeared him to his supporters. Failing twice to be selected as the official candidate, in 1885, he stood as an independent Lib-Lab to win over the Liberals and came out as the winner with a substantial majority. From 1885 to 1920 he was the local Member of Parliament hero and idolised when he went to Westminster as well as his two visits to the USA. The Liberal leaders, W. Ewart Gladstone and David Lloyd George, had a high regard for him and so did Labour leaders from Ramsay MacDonald to George Barnes after 1908 when he joined the Labour Party. Mabon became the spokesman for Welsh Nonconformity in all its aspects, in its campaign for the disestablishment of the Anglican Church and for privileges that had been denied to them particularly in the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. A stalwart of the Sliding Scale in the mining world, he kept the miners contented for most of his life from long drawn out strikes, but by the end of the Edwardian Age, Noah Ablett (1883-1935), a native of the Rhondda who was responsible for persuading the South Wales Miners’ Federation to transfer scholarships from Ruskin College, Oxford, where he himself had been educated, to a new Central Labour College located in Earls Court, London, was a rising star. Ablett ensured that the College would disperse Marxist teachings to a generation of leaders which included future Members of Parliament of the calibre of Aneurin Bevan, Ness Edwards, James Griffiths and novelists such as the Rhondda miner, Lewis Jones. Ablett with Noah Rees and W. H. Mainwaring (all Rhondda based intellectuals) were among the small group based on a café in Tonypandy who met to discuss and finally wrote the important pamphlet The Miners’ Next Step in 1912 which was responsible for popularising the philosophy of syndicalism. This was a world alien to Mabon. It was categorically opposed to the conciliatory attitude of the older miners’ leaders, in particular our leader we have scrutinised Wiliam Abraham.

Mabon did not give in; he kept his popularity and became a celebrity through his advertisements in favour of a Welsh cup of tea and a love of tomatoes. The lad brought up in a small cottage by Port Talbot was one of the richest trade union leaders in Britain by the end of the First World War. He never lost his popularity. His voice encouraged the miners, and they followed him. Even Ablett did not arrange a coup. He died as a hero of the Welsh nation, next to Lloyd George, in the galaxy of the great Welshmen of his day. This is the hero that I delved into his life activities, his ideas, his passions and his background and his undoubted charm.

I am grateful to all those who assisted in the process, especially to Dr Pat Williams, who is always willing to review my work, to Angela Lansley, both from the Liverpool Welsh community for all their efforts, to David Fletcher who has been a steady hand for the last twenty years, and the encouragement of Mererid Boswell and Rhian Davies of the Welsh Book Council. Dr Peter Brooks, a native of Rhondda

Fach, who was the doctor who looked after Gwilym PrysDavies, gave me photographs to do with one of Mabon’s closest friends, David Watts Morgan, who also became a Labour MP for the Rhondda Fach constituency. Siôn Wyn Morris prepared the cover for both books, an unique effort for which I am grateful. Dr Huw Edwards of London on 18 June 2023, after reading the Welsh edition, wrote to me to plead for an English version. I am so glad that I listened to my friend and to implement his wishes before the National Eisteddfod of Wales came to Pontypridd in August 2024 for the Rhondda-Cynon Taf area which has welcomed the Festival to the valleys immortalised by giants such as Mabon. The Welsh language version of Cofiant Mabon was well received, and as I have been told, it is very important that those who do not read the Welsh language should be able to appreciate the life and work of a pioneer of the Trade Union and Labour Movement in Wales. I hope that it will receive the same welcome as the Welsh version as the publishers Modern Welsh Publications, the only publishers of Welsh books in England, had to have two editions of Cofiant Mabon in the bookshops distributed by the Welsh Book Council from its centre in Llanbadarn Fawr, near Aberystwyth.

D. Ben Rees, Liverpool

INTRODUCTION

Mabon, born as William Abraham in 1842, is a forgotten hero today within Britain but in his golden era (from 1880 to 1910) he was the most popular Welshman in the Welsh nation. In 1914 his place was taken by David Lloyd George but the people in the coalfields continued to praise him until his death in 1922. He was regarded as the first Labour Member of Parliament. of the workers in heavy industry and, in his history, his strongest supporters were the miners of the Rhondda Fawr and Rhondda Fach. He was born on 14 June 1842 in a small cottage in Cwmafan between Pontrhydyfen and Port Talbot. His father traveled from Llanfabon to Cwmafan in search of work which he found in the copper industry. His mother – a virtuous woman - was from the parish of Margam, and the son spoke fondly of her throughout his life. His father died when he was a small boy and he had to go to work in the bowels of the earth at ten years of age as a colliery doorkeeper. Aged nineteen, he married Sarah, the daughter of Cwmafan’s blacksmith and she was the mother of six children (one died in 1899) until her own death in 1900. Mabon was brought up as a devout Calvinistic Methodist member of his local chapel and was blessed with a beautiful tenor voice. At fifteen years of age he was appointed precentor in Tabernacle CM Chapel. Working conditions were hard at the colliery and the lad began to express his opinion and defend people who were being mistreated by the managers. He was soon dismissed, and consequently surrounding collieries would not employ him for he was called a troublemaker.

He made the huge miscalculation of venturing with eleven other people to Chile in South America to seek work, leaving his wife and family behind in Cwmafan. There were problems on the sea journey from pirates and fierce storms before they reached the port of Valparaiso. The whole scheme was a huge disappointment to him and he was lucky to meet with a ship’s captain from Cornwall who allowed him a free journey for menial tasks, So he broke his heart after some months of frustration and left his mates behind in the copper works of Chile. He was glad to return home. He lost thirteen months in time and broke an agreement that had been drawn up by the capitalists. He was expected to stay for three years in his new work. He was criticized harshly for breaking the agreement by the chapel leaders in Cwmafan but manged to calm them in a special extraordinary meeting called by his fellow elders.

After his return he moved to a colliery in Waunarlwydd in the Swansea area and saw the need for aTrade Union to defend himself and his fellow-miners. He helped Tom Halliday from Lancashire to set up the Amalgamated Association of Miners in the north west of England as well as south Wales. He became the first full-time miners’ agent in the Loughor area. When he decided to move to Rhondda in 1878, a farewell concert was arranged for him. His supporters flocked from Loughor, Cwmbwrla (where he and his family had been living), Penclawdd and Waunarlwydd in his honour. By 1883 the Loughor District miners had arranged a Testimonial tribute for him in the form of a Concert. In Rhondda he had a golden opportunity to achieve his ambition as a representative of a nonconformist radicalism which after all transformed social, industrial and religious life in Wales from 1880 until 1920.

Mabon was a multi-talented and ambitious character, he had a clear distinct voice when addressing the crowds, incomparable eloquence and the desire to represent the miners at Westminster under the banner of the Lib-Lab. That was the background he cherished with the influence of Methodist preachers such as Edward Matthews of Ewenny near Bridgend and William Evans of Tonyrefail in the Rhondda weighing heavily on him in terms of their emphasis on abstinence, morality and the value of peaceful co-existence between servant and master. Physically he looked like an Old Testament Prophet with his black beard and muscular physique.

On 3 December 1885 the results of the parliamentary election for the new Rhondda seat were announced and the seat was won, not by the Liberal Party’s chosen man Frederick Davis the son of the owner of Ferndale pits, but by Mabon the Rhondda miners’ agent. Mabon twice failed to secure the Liberal nomination for the seat but adopted the idea of uniting the Liberals and those who favoured Labour and Trade Unionism in the grouping which became known as LibLab and stood under that name for decades. It was a very significant result as Mabon had overcome all the obstacles and, for the next 35 years, he kept the seat safely without having to worry at any General Election. He was the first ordinary Welsh-speaker to be chosen as an M.P. in the name of the working class and under the patronage of W. E. Gladstone and latter Tom Ellis and Lloyd George and the Liberals of the Valley’s chapels. He was the ideal candidate with his melodious voice, the man who kept the idea of Trade Unionism alive in the South Wales coalfield after the failure of Halliday and the A.A.M.

It should be remembered that his philosophy of trying to settle every conflict without a strike pleased most of the chapel going miners. They gave him confidence. He was the miners’ chief negotiator not only throughout the south Wales coalfield but, at the end of the century, throughout the British coalfields. Indeed, his reputation and influence was witnessed in the mining coalfields of Europe. He took up the idea of the Sliding Scale: that wages rose and fell according to market prices. Through the use of the Welsh language and prayer, he succeeded in settling one conflict after another from 1885 until the bitter long drawn out conflict in the Tonypandy strike in 1910-12. In that strike different attitudes were perceived amongst the miners and the owners. However, for over twenty years,

Mabon reigned as he was a warm-hearted Welshman, committed to self-rule for Wales and using more Welsh in Parliament than anyone before or after. He recited every syllable of the Lord’s Prayer when the Tories were spitting out hatred at him. His popularity was evident when in 1901 and 1905 he visited the United States. He was hero worshipped by the Welsh in Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York. Sermons he delivered on a Sunday, lively lectures in the weeknights as well as ample anecdotes and and humour in the dinners held in his honour. No Welshman was ever more warmly welcomed to the U.S.A. No-one came anywhere near him for popularity in 1901. He urged the American miners to call for capital and labour to co-operate with each other. Neither the Welsh nor the American press lost their interest in him, particularly when he was elected to the Privy Council in 1911. Queen Victoria and her son the Prince of Wales thought the world of him as did the long-standing Liverpool born W. E. Gladstone and his wife from Hawarden in Flintshire. They would hold a special dinner for him every six months in their London home inviting the English and Welsh Establishment to attend and to recognize his talent, even to applaud him. On his second journey to America in 1905 he had an interview with President Theodore Roosevelt; in the eyes of Labour leaders in America he was none other than Mr. Wales.

Praising Mabon and stressing his central place in Welsh life were essential elements in the task of putting Wales on the world map. As a consequence of the report on education in Wales, subsequently referred to as the Treachery of the Blue Books first published in 1847, the Welsh in response to it tried to support the image of ‘A pure Wales peopled by happy Welsh people.’ Mabon was the ideal leader for them and by 1911 there were more miners under his banner than those of any other trade unionist throughout Britain and Europe. Mabon performed another service: he established male voice choirs as one of the foundation stones of the working-class culture which was supported by one of the most prominent eisteddfod supporters of his age. He was the best ever leader on the eisteddfod platform. He continued as an M.P. far too long but none of the Rhondda rebels such as Noah Ablett made an effort to deselect him, though after 1911 he was absent a great deal from the chamber. He found it hard to leave the closely knit group of Lib-Lab MPs in Westminster for the benches of the Labour Party in 1908. During the First World War the well-known pacifist became a warmonger in order to please Lloyd George. He succeeded in sending forty thousand miners into the battlefield of Flanders and France. He was the best recruiter of soldiers in Wales, better even than the pulpit giant Dr John Williams of the village of Brynsiencyn in Anglesey. During the First World War he became a rich man with his investments and his role in the advertisements of tomatoes and tea. When he died on 14 May 1922 at his home in Pentre, thousands gathered in Treorchy and in September it was announced that he had left the sum of £38,000 equivalent to £454,807 in 2020. Within less than a century he had become a forgotten hero but, with the centenary of his death in 1922, and the publication of a Welsh language biography which went into two editions (see Appendix 3) we have a chance to put him on a pedestal again by the publication in 2024 of an English language biography.

After all, he was the greatest figure of his time.

CHAPTER 1

MABON’S EARLY DAYS

Trade Unionists who have a memorable pseudonym are exceptionally rare in Welsh history and William Abraham is one of them. He was born 14 June 1842 in a tiny cottage, 22 Copper Row, in the village of Cwmafan near Port Talbot, the fourth son of Thomas Abraham, a miner and copper worker and his wife Mary who, according to the Trade Union leader Lewys Afan, came from around Margam. 1

His father died when William was very young and, by 1851, they had moved to 25 Copper Row and the responsibility for his upbringing fell upon his mother. His father Thomas came originally from Llanfabon in East Glamorgan and he travelled to Cwmafan to get work in the copper industry. Mary was a very virtuous woman and particularly religious, a firm Calvinist and faithful to the Calvinistic Methodist cause.

It was his mother who taught him to read in both languages and he was completely fluent before beginning his education in the Church School.2 Mabon remembered how, as the child of Nonconformists, he was forced to go to the Parish Church on a Sunday. And if he and others of a similar background were not seen there, they would be punished with the birch on Monday morning. According to Lewys Afan, members of the Calvinistic Methodist Chapel would rejoice when he came to the notice of the public, saying: ‘He is one of us.’

However, the upbringing William Abraham received was that which was offered throughout the length and breadth of Wales by the Nonconformist chapels. The chapel was the prime influence in a village like Cwmafan during the years of William Abraham’s childhood. Who were the members of the chapel? Mainly ordinary workers like Thomas Abraham, miners, workers in the steel mills and shopkeepers of every sort and led by those called elders in the Calvinistic Methodist chapels and deacons in the Welsh Independent and Baptist chapels. Overall charge was in the hands of the minister and,

1 Lewys Afan, ‘Poblogrwydd Mabon fel AS’ Tarian y Gweithiwr (Workers’ Shield), 25 March 1886, 3.

2 E. W. Evans and John Saville, ‘William Abraham (Mabon)’ in Dictionary of Labour Biography, volume 1 (London and Basingstoke, 1972).

by the time of the childhood of this gifted boy, from 1842 to 1852, the majority of them were very able leaders. As the years went by the strength and talent of nonconformist ministers would increase. It was they who made the chapels powerful and dynamic all over Wales, England and the United States, the subject of wonder and discussion. Cultural and religious witness was admired, and people flocked to be members of an institution which provided so many activities. The political minister, as I call him, was the loudest on the Cymanfa (Festival) stage and was heard speaking eloquently in the annual Preaching Meetings held wherever there was a flourishing Welsh Chapel. Some of the important theological figures of the time feared that political ministers would turn the chapels into political clubs for the Liberal Party. Principal D. Emrys Evans gives a good example from the life of Samuel Roberts (‘SR’, 1800-1883) of Llanbryn-mair:

Perhaps the example of the compatibility of the evangelist and the social reformer was Samuel Roberts of Llanbryn-mair, the faithful minister, valiant fighter for peace and ardent reformer who thought deeply about the principles of government and devised a host of social improvements and brought them to the attention of the authorities.3

William Abraham’s debt to the chapel was enormous and he never forgot that. He benefitted greatly from the Band of Hope, a temperance based organisation, then Sunday School for all ages and singing meetings. He frequented the Seiat, the religious discussion meeting, where he was enlightened as to the faith and regularly had the Scriptures explained to him. As a small boy he looked forward to the communal hymn singing sessions.

He succeeded in reading music and ventured to compete in chapel and community based eisteddfodau (cultural festivals). This was an apprenticeship for a post he occupied throughout his life, namely Blaenor y Gân (Precentor). He would work together with the organist or the accompanist and choose suitable tunes for the hymns which were chosen according to the Sunday theme. Being a Precentor was not equivalent to being a fully fledged elder (also called blaenor) but he would stand in front of the Sêt Fawr (Elders’ Pew) in front of the pulpit to lead the congregation in harmony and to praise the Lord of Life in His sanctuary.

In the Tabernacle chapel, Cwmafan he was reared as a Calvinist. The leaders and members of the denomination followed the doctrines of one of the most important reformers of the Protestant Reformation, John Calvin of Geneva.4 John Calvin saw every step that he took from his childhood in France to his continuing work in Geneva as an adult in terms of predestination and being one of the chosen people of Almighty God.5

William Abraham saw his life as a way of praising God and his success in life is a sign of blessings of the Infinite surrounding him. The people amongst whom he was brought up

3 D. Emrys Evans, Crefydd a Chymdeithas (Religion and Society) (Cardiff, 1933), 113-14.

4 D. G. Hart, Calvinism: A History (New Haven and London, 2013), 17-20.

5 Ibid., 16, 20, 38, 65, 80, 82-3, 88-90.

in Tabernacle Chapel, Cwmafan were people who believed in self-discipline and who, as far as possible, respected the importance of the Sabbath as a day of rest as well as worship. Though they had been destined for eternal life since before the world was created, they were expected to give as much as they could to the requirements of their present life. They believed, according to the Confession of Faith drawn up in 1823, that they were not to be idle or lazy or to wander without a purpose from place to place. They should be honest in everything, forswear alcoholic drink and reject gambling. Calvinists should be generous to others, merciful to the needy and sympathetic to those who were lonely or in grief.

We hear the voice of many a Trade Unionist and Liberal M.P. in what I have described and also that of many of the great leaders of the Victorian Age. This is at the core of the learning and activities in the chapels of Wales. Professor D. Emrys Evans, himself a son of the manse, summed up a picture of William Abraham’s fellow-members.

Most of the saints were lively, orthodox Puritans and the most important things for them were the salvation of the soul, keeping the Sabbath and keeping the doctrines.6

By now, the members of the Presbyterian Chapels of Wales have lost their grip on these three essentials – evangelising, keeping the Sunday special and preserving Calvinistic theology. But in the early years of that talented young boy in Cwmafan the importance of these three tenets can be witnessed. But the chapel, as has been mentioned, was much more liberal, secular and cultural and political than mentioned by D. Emrys Evans, though it comes close to what he describes in his book on religion and society.

Cwmafan as a village had a large number of Nonconformist chapels during the time of William Abraham’s childhood. The oldest of the chapels was Seion Chapel which was opened in 1821, and then Tabernacle, the Chapel of the Calvinistic Methodists which was built in 1837. The Rock Chapel which belonged to the Welsh Independents came to serve the community in 1840 and Penuel Welsh Baptist Chapel in 1844. William Abraham remembered the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel opening its doors in 1849 and Bethania Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in 1851 and then in 1859, the year of the religious revival, the chapel of the Bible Christians, a denomination not much heard of in South Wales in those days.7 The young lad saw a great deal of building work carried out in his early years. From 1845 to 1847, over five hundred houses were built in the village of Cwmafan.8

William Abraham was set an example of firm leadership, which stood him in good stead for his future life, from the chapel minister, the Reverend Thomas Edwards, an interesting character who loved to participate in the Liberal Party politics of the day. Another nonconformist minister who offered him sincere friendship was the minister of Seion, the Reverend Edward Roberts. He kept a grocer’s shop where his (Abraham’s) mother bought most of their weekly goods. Roberts was naturally sympathetic towards her in

6 D. Emrys Evans, Crefydd a Chymdeithas, 114.

7 NLW Welsh Calvinistic Methodist Archives 14,842, a typescript on Mabon by the Reverend Daniel Davies of Pentre, Rhondda.

8 Ibid., 5.

Wern’), see 1860, Massachusetts and Raymond Volume 1

the loss of her husband and would be full of understanding on Saturday night which was time for the weekly payment. Many a family took advantage of his kindness, more than they should have and he was often called Father Roberts by the members of the Irish community who lived in the village.

Mary Abraham’s family never missed services on Sunday morning and evening nor the Sunday School in the afternoon. The Reverend John Parry of Chester and all other propagandists for catechism, could praise the religious atmosphere in Wales by the 1830s. Wales had incomparable preachers and three of the most able died within three years of each other in that period namely: Christmas Evans, the hero of Welsh Baptist congregations, who passed to glory in 1838, William Williams of ‘Y Wern’, the bright star of the Welsh Independents who left the Rhosllanerchrugog area bereft of him in 1840 and then the giant of Calvinistic Methodism John Elias of Anglesey, often called the Pope of Anglesey, who was laid to rest in Llanfaes near Beaumaris in 1841.9

William Abraham’s generation was deprived of the three most famous Welsh Nonconformist preachers, but by the time of his boyhood, other giants had come to fill the shoes of those who had departed. In Glamorgan, William Abraham’s peers heard three fine preachers, namely the Reverend William Evans, Tonyrefail (1795-1891), Edward Matthews, Ewenni (1831-92) and finally David Saunders, Aberdare, Liverpool, Abercarn and Swansea.10 All three of them fostered the Calvinistic Methodist cause throughout Glamorgan and Monmouthshire in a period of industrial turmoil and a huge increase in population, especially in the Cynon Valley, Ogmore Vale and the Rhondda Valley. William Evans of Tonyrefail supported politicians like Mabon from one election to the next. The greatest of the preachers who came to Cwmafan was the larger than life Reverend Edward Matthews who began his career in Hirwaun in 1830, then was the minister of Penuel Calvinistic Chapel in the heart of Pontypridd and who lived in comfort at Lower Ewenny, Cardiff and Simonstown for the rest of his long life. According to the historian, the the Reverend Dr Gomer M. Roberts, he was without any doubt ‘the king of the Sasiwn (quarterly sessions) amongst the Calvinistic Methodists for a long period.11 He was rightly described as the ‘greatest master of mockery and sarcasm that I ever encountered.’12 These men inspired William Abraham as he grew to manhood.

The time came for him to think about earning a living and he had very little choice. A coallevel was opened in Waunlas in 1750 and another, Y Wern, in 1812 and the Morfa Mine was sunk in 1849 and it was there that the ten year old boy went to help his widowed mother He had this opportunity in 1852 and remembered well how he left his mother’s cottage with his tin miner’s flask of water under his arm, his food box in his pocket and

9 For William Williams (always referred to as ‘Williams o’r Wern’), see R. Tudur Jones in Dictionary of Evangelical Biography 1730- 1860, Volume 2 (Donald M. Lewis, editor) (Peabody, Massachusetts 2004, 1201-2; for John Elias, see Edward Morgan, Letters and Essays ( Edinburgh, 1973), and on Christmas Evans, Raymond Brown in Dictionary of Evangelical Biography 1730-1860, Volume 1 (Donald M. Lewis, editor), 367-8.

10 All these pulpit giants are recorded in N.L.W. Biography on Line 11 Y Bywgraffiadur Cymreig hyd 1940, (London, 1953), 584-5.

12 D Ben Rees, The Welsh in Liverpool: A Remarkable History (Talybont, 2021), 88.

with his other hand holding on to the hook at the top of his Davy lamp. He descended to the bottom of the pit where the fireman would be waiting for him to give the last twist to the bottom of the lamp to lock it, the Davy safety lamp, which had served as a good friend to every miner in Britain since 1812. He was given the important task of the pit door-boy – that is looking after the door through which the wagons of coal would pass to their destination. The world was a hard and pitiless one for the strong boy; it was quite different from most industries, though one has to remember that the tin, iron and copper works in Cwmafan were not in existence till 1866, which meant that the only choice he had was working as a coal miner.

Outside the colliery confines, the young miner had plenty of activities to keep him happy. One of the organisations from which he benefited greatly was the Sunday School. It was a day to remember when, in his teens, as a 17 year old energetic lad, he was invited to be a teacher to a class of 5-10 year olds. One of the brightest boys in the class was John Hughes (1850-1932). His parents, Dafydd and Elizabeth Hughes, had moved from Swansea to Cwmafan and had become members of Tabernacle; these boys (four of whom went into the ministry) were educated by the young teacher. Later in his life, he delighted in the fine scholarship of John Hughes and his brothers and especially in John’s contribution as a powerful preacher, the minister of the flourishing Fitzclarence Street Welsh Calvinistic Church in Liverpool and a poet and effective writer.13 His brothers were of the same calibre – three of them served in the Anglican Church.14

It was in this period that William Abraham adopted the eisteddfodic pseudonym Mabon and that name became familiar and particularly popular for the rest of his life. He adopted the name Mabon in memory of his father who came to Cwmafan from Llanfabon. Another reason for adopting a pseudonym was that he had become used to the competitive spirit of local eisteddfodau. Each chapel would hold its eisteddfod. Bethania Chapel Eisteddfod, for instance, was held on Christmas Day, with a session in the morning from 10 a.m. and the afternoon one at 2 p.m. Great emphasis was placed on writing as well as on music and recitation. In sending work for assessment, a pseudonym was expected and now he would use the name Mabon at every opportunity in public.

He became an avid reader and read widely in both languages. The poet John Ceiriog Hughes known simply as Ceiriog became one of his favourites in Welsh and in English he thought highly of the poetry of Alfred Tennyson. He learnt a lot from the books of John Stuart Mill and Thomas Carlyle.15 He regularly wrote articles for the eisteddfod competitions and won prizes which encouraged him. By the time he was fourteen, he was one of the up and coming future leaders of the chapel. At least, he was in charge of the temperance movement for the children, called the Band of Hope. Later in his life he could say:

13 The other brothers were Reverend Lewis Hughes, Gower; William Hughes, Colton, Salisbury and James Hughes, Minetown, Hereford Diocese. See D. Ben Rees, The Welsh in Liverpool, 88 14 N.L.W. The Papers of Reverend W. Rhys Nicholas. Manuscript No 70 on Mabon.

15 William Evans (Gwilym Afan) and LL. Griffiths (Glan Afan), ‘Cymanfa Ganu Cwmafan’, Y Celt, 11 May 1902, 2.

What I am today, whatever that I may be, I owe to the Sunday School, Band of Hope and the Eisteddfod.16

His musical talent was very useful and, by the time he was sixteen, he was involved with the Tabernacle Choir and, a year later, was invited to be Conductor of the Mixed Choir of the Welsh Independents’ Rock Chapel. This choir was extremely successful in local eisteddfodau under his capable leadership. Mabon filled the role of precentor in the Tabernacle.

Two cultured men were mentioned as upholders of the musical tradition of sacred music in Cwmafan.17 One of Mabon’s successors as precentor in the Tabernacle was William John. He held the position from 1872 until 1909. He taught the Chapel Choir the main oratorios for a period of 37 years.18

Mabon was very fond of his employers in the coalfield and, before starting on his work, the mine was in the charge of an intelligent man called John Biddulph. He believed the miner should improve himself and opened a Reading Room so that they could spend an hour or two reading the daily and weekly papers and journals in Welsh as well as English. Biddulph set up an educational organisation called the Mechanics’ Institute and this resource proved a great help to the ambitious young man. Biddulph made sure to employ two clergymen to minister to the miners, especially when they experienced accidents and hardship.19 Mabon had a terrible accident in the mine and the clergyman was very kind to him and, as he recovered, he derived great benefit from the Reading Room. Amongst the journals Mabon read was Y Diwygiwr (The Reformer) under the editorship of David Rees of Llanelli, the minister of the Independent Als Chapel from 1829 until 1868. David Rees was a great radical and had a major influence on Mabon. He heard him lecture and Y Diwygiwr was one of his favourite journals in his youth. David Rees always campaigned against alcohol and Mabon himself became a total abstainer. John Biddulph made sure that there were not too many beer houses near the colliery to tempt the drinking miners.

David Rees was scathing about the landlords and industrial and marketing monopolies, against the system in the industrial areas of paying in kind, against black slavery in the United States and British imperialism in countries like India. He supported the cause of Rebecca in the early 1840s and her followers dressed up in women’s clothing in north Pembrokeshire against imposing heavy taxes at the toll gates as they carted lime and other necessities from Carmarthen to their smallholdings on the Preseli mountain. Rees, like many others in the county of Carmarthen could not come to terms with the violence some of these radicals exemplified in destroying the tollbooths. He was in favour of the

16 Mabon became the leader of the Band of Hope. See D. M. Evans, (Cymro), Dathliadau Jiwbili Tabernacl, Cwmafan (Cardiff, 1924), 10-11. 18 N.L.W. Papers of Reverend W. Rhys Nicholas, No 70 on Mabon

17 Ieuan Gwynedd Jones, ‘Smoke and Prayer: Industry and Religion Cwmafan in the Nineteenth Century’, The Journal of Welsh Religious History Volume 6,1998, 31-2.

18 Huw Edwards, Capeli Llanelli, (Carmarthen, 2009), 39.

19 Robert Griffiths, Streic! Streic! Streic! (Cardiff, 1986), 15.

principles of Chartism but felt that some foolish, unprincipled and irreligious leaders besmirched the protest.

Young Mabon absorbed the ethos of Nonconformism, the firm stand on Calvinism and Radicalism which cared for the ordinary people.20 He saw this in the coal mine in Cwmafan. He never spoke of his life as a young miner apart from referring to Biddulph, but there was no-one amongst his fellow workers prepared to stand up for the human rights of the worker. He himself had started work as a door-boy at age ten but by the time he was seventeen, he felt extremely uncomfortable about how conscientious men going about their hard daily work were treated with contempt. He spoke up frankly for the rights of his fellow miners, causing the company employing them to be fearful of him and very suspicious. The solution for the colliery proprietors was to dismiss him for drawing the attention of his fellow miners to human rights.

This was very worrying for the family living in 30 Lower Row, Cwmafan, his mother and family needed every week Mabon’s wages. Mercifully, he found work in the copper industry. He himself had fallen in love with a young woman called Sarah Williams who came from the Gower Peninsula. Her father was David Williams, who became a Cwmafan blacksmith. By now Mabon was nineteen and she Sarah was twenty but she had been completely deprived of formal schooling, so that she had no opportunities in terms of literacy.21 Mabon was determined to improve the lot of his fellow workers and was greatly disturbed by the hardship and oppression he saw, with nobody available to defend the miner who was mistreated and disrespected. He realised that women worked in his colliery as in other Glamorgan and Monmouthshire mines. The pay of both the men and women was quite unacceptable. During the nineties, the women would receive between six and eight shillings for a week’s work totalling 54 hours. At the end of the century, the majority were receiving only a shilling a day, a wage of seven shillings per week. Throughout the nineties women and girls were expected to work underground and were, for the most part, employed to make bricks.

Being sacked strengthened the resolve of the doughty fighter. Hard days were at hand – days when he had the house to himself to teach Sarah some literacy and days to work out how to help the miners who had no-one to support and represent them. Eventually he found work in the copper industry but his main wish was to be involved again in the of coal-mining industry.

20 Weekly Mail, 3 April 1897, 9. There were at least half a dozen women working as miners in 1897 at the coal face in the Cwm Colliery, near Ebbw Vale, in Nantwen colliery, Bedlinog and in the Dowlais collieries of Dowlais.

21 According to W. Rhys Nicholas, Mrs Sarah Abraham (neé Williams) had only a week’s education during her childhood and her teens. N.L.W Papers of W. R. Nicholas.

CHAPTER 2

WANDERING

By the 1860s, Mabon had regular face to face meetings and committees of mining experts which led him to understand the coalfield and how to guide them as a leader of South Wales miners in the seventies. He was a man moulded by Nonconformism, by chapel spirituality, endless theological discussions in the weekly Seiat (group meetings) as well as the Adult Sunday Schools where the Scriptures threw light on the difficult circumstances often found in the collieries. In Cwmafan he inherited cultural and religious values, Sunday School life, the Singing School usually after the evening service and preparation for all the local eisteddfodau (competitive meetings) which often meant attendance at ten different vestries and chapels. All this was a by-product of the cultural activities of the Chapels and their constant competition and determination to be the most flourishing religious cause in the locality. There was a sincere belief among these Calvinists that hard work, disciplined life at the home and daily chapel activities were all interlinked and to be cherished so as to produce a rounded, principled individual.

Every society in Wales produced its leaders and they would speak on issues of the day. In the chapel, the minister was usually the recognised leader, though lay people distinguished themselves in Sunday school work, literary activities and, in Mabon’s case, in the weekly Band of Hope.22 Mabon revelled in researching, as well as writing for the eisteddfodau though he did not always win in all the competitions.23 The local Welsh language press enjoyed giving prominence to young and old who were supporting chapel

22 Another leader who followed Mabon was James Griffiths. (1890-1975), MP for Llanelli and, before that, the President of the South Wales Miners Federatioin. James Griffiths says that all his early memories derive from the Sunday School and the Band of Hope, especially under the influence of John Evans, a station-master and charismatic leader of the the Independent Chapel in Gellimanwydd, Ammanford. See James Griffiths, Pages from Memory (London, 1969), 16; D. Ben Rees, Cofiant Jim Griffiths: Arwr Glew y Werin

23 Thomas Arthur Levi, ‘Tomas Levi (1825-1916)’, Y Bywgraffiadur Cymreig / The Dictionary of Welsh Biography 1940 / The Dictionary of Welsh Biography until 1940, 510. Mabon got to know the Revd. Thomas Levi when he was minister to the Calvinistic Methodist Chapel near Ynys in Ystradgynlais (1855-60) and Philadelphia, Treforest (1860-76) before moving to Aberystwyth. He did exceptional work through the children’s magazine Trysorfa y Plant (The Children’s Treasury) and Mabon bought the magazine for his family from 1862 until 1890.

orientated culture. I was able to locate the name of young Mabon after he won a gold prize for writing an essay adjudged by far to be the best by the Reverend Thomas Levi who was the most successful editor of a children’ magazine in nineteenth century Wales. It was called Trysorfa’r Plant and reached a sale of over fifty thousand copies.

Mabon’s standing by the time he was seventeen years of age attracted both local and regional attention. In Mabon’s early days, the workers in heavy industries did not have local leaders to compare with Welsh Nonconformist chapel leaders such as David Rees of Llanelli but it was only a matter of time though it took a long time for Trade Unionism to become a force in south Wales and the man who kept the flame alive during years of indifference was, to the Eisteddfod goers Gwilym Mabon, but to the miners simply Mabon.

By 1864, because he could not find employment in Wales, Mabon was ready to consider travelling to the South American continent and to Chile. Chile is a country on the western side of South America and the discovery of plenty of copper in the Atarama desert attracted adventurous people from different countries to seek El Dorado and become rich. A railway system was developed in 1851 and that helped to develop the copper industry.24 Eleven Welsh people travelled with Mabon to Chile and, having reached the country, they realised that they had been badly misled. El Dorado did not exist in any shape or form and what work there was for them was extremely scarce. These Welsh workers had foolishly signed a three year contract, a binding agreement and it is hard to believe that a man as clever and shrewd as Mabon and with a wife and two young children living in Cwmafan in Wales would have fallen into this trap. It is not surprising that he failed to refer to this unfortunate ordeal in the memoirs that I have seen in his hand. He was not at all comfortable outside a puritanical Calvinistic Welsh-speaking community, especially when some of his fellow-workers were willing to behave badly in his sight and attend a circus of all activities on a Sunday afternoon. For a staunch Calvinist who respected Sunday as the Lord’s Day, that was without any doubt the wrong thing for any Welshman to do. He longed in his hiraeth (intense longing) to return to West Glamorganshire and, after a period of thirteen months, he managed to escape from his self-imposed captivity and return, bitterly frustrated, from this fraught adventure.25

As can be imagined, it was a hard journey from Wales to Chile. The boat called Hawkeye took four long months to reach Valparaiso and the foolish Welsh adventurers were thrown about like a loose ball by the waves that frightened the life out of them in many a storm. Many sailors lost their lives on the journey past Cape of Good Horn and, after reaching dry land in South America, Mabon was idle for a month and eventually had to accept lowpaid work in Tonguoy. This experience together with hiraeth for his wife and children, his mother and the chapel folk of the Tabernacle was enough to convince him that there was no place like home. By chance or by providence, he met a kind fellow Celt, Captain

24 Fran Alexander (ed.), Encylopaedia of World History (Oxford, 1998) 136.

25 D. Davies, ‘Mabon a’r Capel’ / Mabon and the Chapel, Y Drysorfa / The Treasury Dec. 1949, 12; LL.G.C. (Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – National Library of Wales, Papers of the Revd. W. Rhys Nicholas. Ms. 70.

Walters from Truro, who offered him work on board ship, thus saving him having to pay for the voyage back to Wales. 26 The fact that the captain came from Truro made the point that so many of the Cornish working class were ready to emigrate to the United States and Chile to work in the copper industry.

Mabon arrived back after being away for thirteen months and, via a friend, got his job back in the smelting furnace. Once he had reached the shelter of his home, the monthly meeting of the Elders of Tabernacle Chapel arranged an interview with him in order to hear from his own lips the reasons for breaking the contract for three years which they, as Calvinists, regarded as sacrosanct. This is a good example of the discipline that John Calvin had inserted in his magum opus The Institutes of Christian Religion for the inhabitants of Geneva and anywhere else. Calvinists in the rest of the world were expected follow suit. This explains clearly why Mabon himself, in his years as Miners’ Leader, expected the miners, like the owners, to respect contacts and agreements. After one of the elders had brought the issue of the Mabon affair to the attention of those who attended the Meeting in Tabernacle Vestry, a popular elder, John James then rose and addressed the accused and said with compassion in his voice, ‘Let us hear what Bill has to say.27

John James did not want any of them to be tempted to vote to exclude Mabon of all people from the Seiat and the chapel community for his alleged offence in Chile in the light of Calvinism, without hearing his side of the saga. They knew as elders that the man behind the enterprise was none other than a cultured Welshman, Thomas Francis (Afonian), from the Orchwy Valley.28 Thomas Francis was a rather selfish individual. It is true to say that he would have left Mabon in dire straits were it not for the ship’s captain from Cornwall. It was through him that he escaped to freedom in the Land of My Fathers. Thomas Francis was a great friend of Islwyn, the poet and preacher, William Thomas, from Monmouthshire and there is a verse in his book of poetry mentioning ‘Johnny and Thomas Francis’, Guayacan, Chili.29 On hearing Mabon’s side of the story presented in his own particular way, the rest of the Seiat members were won over before he had completely finished his defence.

By 1869 the smelting industry was in economic trouble and Mabon and other workers heard that they would have to work fewer hours. He heard that one of his acquaintances, Evan Daniel, and his family, intended to leave Cwmafan for Cwmbwrla, a suburb of Swansea. He was employed in the tin works. Mabon knew only too well what it was to work until sweat was pouring from his body but the new job was again exceptionally difficult. He wrote of his experience in English:

26 Ben Bowen Thomas, ‘Mabon’, Y Traethodydd (The Essayist), Oct. 1948, 26.

27 David Davies, Bywyd a Gwasanaeth y ddiweddar William Abraham (Mabon) (The Life and Service of the late William Abraham), winning essay in the Treorchy National Eisteddfod 1928. Ll. G. C. Archives of the Calvinistic Methodists 14, 842, 7.

28 Ibid.

29 The verse is in Gwaith Barddonol Islwyn (The Poetry of Islwyn), ed. O. M. Edwards (Treherbert, 1897), 146.

The work was very different from that which I had become accustomed. It was excessively hard, and needed a man of great strength to do it. We had to break up the iron ‘stamps’ which, after coming from the furnace, had been under the forge hammer. To do this, we had to use a great sledge-hammer weighing fifty pounds and, with my muscles that I attribute to the strength of my arm, which remains to the present day. 30

Despite the horrifically hard work, the well-built man possessed enough energy to enjoy the spiritual and cultural life of Y Babell (The Tent) Calvinistic Methodist Chapel in Cwmbwrla. Y Babell stood in an ideal position, quite like the synagogue Jesus frequented in his youth in Nazareth. Y Babell Chapel, as I remember well, stood at the top of a hill as one entered Swansea from West Wales. Y Babell Chapel was newly opened and, from his first week there, Mabon threw himself into the witness of temperance in the Band of Hope meetings. He was soon leader of a party of the most dedicated chapel musicians who were called Y Babell Glee Party.31 Mabon, as usual, enjoyed opportunities as a poet, leader of the children’s activities and was above all a most able musician. Everyone around him in Swansea and the outskirts greeted him with affection and respect as ‘our Mabon’. The tin industry in its organisation and management hierarchy did not give Mabon the same thrill as the coal industry did and, in 1870, he returned to the life of the colliery. He obtained work in Caercynydd Colliery in Waunarlwydd, a village situated between Gowerton and Swansea. This was an extremely important decision as he was again, as in Cwmafan, involved in a situation which offered him a great deal of social, trade union and chapel leadership.32

In 1871, he witnessed bitter strikes, a situation totally unexpected in the history of Welsh coal miners. The strikes which took place in 1871, 1873 and 1875 were not ideological battles but the only way left for the miners to convince the colliery owners to offer fairer wages and better working conditions than they had done in the past. Through studying in detail Mabon’s life we can see how hard it was to build Trade Unionism within the working class in Wales in the Victorian era.

In the English coalfields, the miners formed unions to defend themselves from exploitation by their employers. In 1863 there was established a trade union called the Miners’ National Union and miners from different parts of England came to support it.33 But the MNU refused to deal with the question of wages or to support strikes, focussing only on improving the pits in terms of safety. Many miners came to feel that the attitude of the Miners’ National Union was hopeless as they argued that bargaining for better wages was one of the fundamentals of trade unionism. This discontent was expressed loud and clearly, and a leader appeared called Thomas Halliday. This pioneer set up a trade union in

30 LL. G. C. The Papers of Mabon X.C.T. 399 A 159. Article by Mabon. But there is no name of the journalist and it is undated.

31 E. W. Evans, Mabon (William Abraham, 1842-1922): A Study in Trade Union Leadership (Cardiff, 1959), 6.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

Lancashire called the Amalgamated Association of Miners (AAM). The aim of the new trade union was to improve wages for the miner and help them to come to an understanding on the issue under consideration. Then if they were deliberately obstructed, they should opt for an all out strike so as to limit the profits of the coal owners. The AAM as it was known in the Welsh coalfield was much more militant than the Miners’ National Union. Halliday himself travelled to Wales where he soon realised he could gain more members for his emerging trade union.

It was not easy for the new trade union as the masters had got in first and had formed the South Wales Steam Collieries Association. Nevertheless, the AAM won supporters, including Mabon, in south Wales. He made an impression in Waunarlwydd, not only amongst the miners but also amongst the chapel leaders, particularly the chapels of Bethel in Gowerton and Seion in Waunarlwydd. Seion was a Welsh Baptist Chapel and its minister, the Reverend William Davies was won over by Mabon’s eloquence. He arranged a meeting with him and advised him at the Special Preaching Meetings and Cymanfanfaoedd. (The Yearly and half yearly Preaching Festivals) to consider a path to the ministry as he would have a bright future as a preacher. He promised that he would give him every assistance with preparation, praying earnestly that Mabon would accept the serious challenge. His mother agreed with the Reverend William Davies that he should consider the Welsh Nonconformist Ministry as a means of dedicated service to Almighty God and his fellow workers. A number of miners in that era embarked on the venture of becoming popular Welsh Nonconformist pulpit giants. Ben Davies of Ystalafera and W. Hezekiah Williams (Watcyn Wyn) left the pit for the pulpit and this happened regularly in the south Wales coalfield during the life and times of Mabon.

After much prayer and serious thought, Mabon expressed his desire to be a lay preacher and a leader within the chapels. This suggests that to him there was a great deal in common between being a Minister of the Gospel and a Trade Union Leader as well as a political leader. It all indicates Mabon’s religious sincerity at the outset of his career as a prospective leader of the South Wales miners.

In summer 1871 there took place a particularly important episode in Mabon’s life in Waunarlwydd on the outskirts of Swansea. Lewis Morgan, an early trade union pioneer, travelled from Treorchy in Rhondda Fawr to address a public meeting on behalf of the AAM Union in Waunarlwydd. Lewis Morgan was not an eloquent public speaker though he knew his subject well and he made the mistake of presenting his views in the English language and not in Welsh, the language of the majority of the workers at the small but militant Caercynydd colliery. Lewis Morgan spoke for twenty minutes and it looked as if the meeting, which had been well-briefed, was going to finish without any worthwhile decision being made.34

Before the large crowd of miners scattered, the Chairman turned to Mabon and said, ‘Look here, William, can’t you say a word, my boy? Mabon rose, quite nervous and remembered

34 Ibid.

that Lewis Morgan had presented the need to come to an agreement so as to resolve labour problems. The whole atmosphere of the meeting changed immediately, and Mabon was well-received. He spoke of the dangers and troubles of being too militant but on the other hand he wanted to teach the employers a lesson. The Chairman was delighted and Lewis Morgan rejoiced. He shook Mabon’s hand with gusto and said that he needed to start to organise the miners of West Glamorgan without delay. He listened to the advice of the Rhondda miner and, in his spare time, he went about addressing and organising the miners. His efforts were very successful and he became a favourite of his fellow-workers. Mabon had a strong, firm personality and was equally fluent in both languages. He played a prominent part in the 1871 strike and made a great impression on his fellow-workers. By the end of 1871 he had established a lodge of the Miners Union in Waunarlwydd and was duly elected Secretary. The academic, Dr E. W. Evans wonders at the unusual decision that took place. Mabon, who had shown more interest than most in organising a lodge before Lewis Morgan’s visit, is immediately elected Secretary. After all, he had only joined the trade union a short time before Lewis Morgan came on the scene.

In the months that followed, he threw himself with all his strength, ability and enthusiasm into the task of building a Trade Union in east Glamorgan and east Carmarthen. Lewis Morgan called to see Mabon and, in spring 1872, a meeting was arranged in the Athenaeum in Llanelli to consider whether it was appropriate to set up a Loughor district branch of the Lancashire based Trade Union. Mabon was elected Secretary of the Loughor District and John Howells, a miner from Loughor as President. It is more than likely that this was the first district of the trade union to be established in west Wales.35 Within a matter of months, Mabon had won over a good proportion of the miners to consider the three principles discussed in the meetings held in 1871 and 1872. In his view, the first task was for the employers to allow the miners to join the Trade Union voluntarily; secondly for the employers to acknowledge the importance of the Trade Union as the sole organisation defending the miners; and thirdly to try to improve conditions at the collieries in terms of wages, safety underground and the daily as well as weekly working hours.36

In April 1872 Mabon represented Loughor District in a general assembly of the Union and took advantage of the opportunity to address it in English and made such an impression that he was elected a member of the Executive Committee before the day’s proceedings were over.37

It has to be understood that Labour Unionism was not at all acceptable to the early owners of the collieries; for them they were people creating disorder. And many knew that, in the long run, the outcome could be the loss of work and when the owners of Caercynydd colliery heard that he had been elected to the Executive Committee, he was told that his employment with them would terminate at the end of the year.

35 Ibid.

36 David Davies, Bywyd a Gwasanaeth William Abraham (The Life and Service of William Abraham), 12.

37 T. R. Jones, ‘‘The Life and History of William Abraham’, The Ocean and National Magazine, X, 1936, X7.

He worked his last shift just before Christmas 1872 and his mining days came to an end. He worked only twelve years in the bowels of the pit but had almost fifty years ahead as a miners’ leader, one of the most important voices, not only in the south Wales coalfield, but in the United Kingdom.

With a large family to support, Christmas 1872 was a painful one for the lovable unemployed miner. He remembered vividly how his wife recalled the first strike in which he was involved in at Cwmafan in 1860. 38 They both of saw many of the wives and children of miners going from door-to-door begging for a piece of bread because of the lack of financial support while on strike. There was no Trade Union to give any assistance to workers on strike in 1860. It was a little better in 1871 because of those miners who were willing to be involved in trade union witness. Mabon felt that heavenly providence looked after them when, as a family, they were saved by the offer of a job as the salaried agent of the Loughor District Miners organisation belonging to the AAM. He was the first full-time agent in the entire history of the miners in Wales.

Mabon was an important figure in the development of the post of a miners’ agent also Within forty years, the Trade Unions of the coalfields came to depend heavily on these men who organised a district which could include in Loughor 17 or in another district 30 or perhaps 50 or even70 or more collieries from their office. Dr E. W. Evans described the role the miners in south Wales at the beginning of the twentieth century thus:

They were, of course, much more than mere industrial experts. Their style of life was more that of a professional man, a white-collar worker, than it was that of the collier. The position was one of considerable responsibility and had commensurable power and influence. Mabon’s character was a shining example of the potential in a miner’s agent’s life; the message was not lost on younger men like Frank Hodges or Vernon Hartshorn, whose espousal of different methods and more radical language cannot conceal their kinship to the older men.39

The Loughor District was big enough to justify having a fulltime agent and Mabon was elected by fifteen out of the seventeen lodges. He made his mark outside Loughor District quickly, especially as a most eloquent speaker and a full-time agent who cared for the well-being of the miners.

Early in 1873 there was another strike – this time amongst the workers in the south Wales iron industry – and Mabon had a chance to use his talents on behalf of the strikers. He was widely respected for his stance. For the first time ever he travelled that year to the Rhondda Valley – a valley where he himself would soon be living. Mabon advocated compromise rather than striking to resolve industrial problems. He was called to settle problems in Cwmtwrch in the Tawe Valley in the anthracite coalfield and with his particular gift succeeded in persuading the overseer to re-employ the miners in the colliery. And

38 ‘Llythyr Hen Golier’, ‘An Old Miner’s Letter’, Gwladgarwr, 24 November 1860, 1.

39 E. W. Evans, Mabon (William Abraham, 1842-1922), 10.

although there were calls upon him from all over south Wales, he knew that it was the Loughor District miners who were financing his post and that his priorities lay there. His first task was to win over more miners to be members of the Trade Union in the Loughor District pits than travelling to other districts.

He was lauded when, at the end of 1874, it was revealed that eight thousand miners belonged to the Trade Union in Loughor District. However, in general, the Union had not grown in 1874 and this created something of a problem in terms of financial resources. On New Year’s Day 1875, another strike began. By now Mabon was recognised as a leader. Indeed, Dr. E. W. Evans argues that it was this strike that made Mabon the chief miners’ leader.

It was during this strike that Mabon first emerged as an influential leader with sharply defined principles and opinions on industrial matters. He not only took his place in the forefront of the movement, but also adopted an independent policy which on occasions clashed with that pursued by Thomas Halliday, the English president of the organisation.40

This did no harm at all to his popularity as Thomas Halliday was unable to communicate well with Welsh-speaking miners. The two strikes – one in 1871 and the second in 1875 – showed that Mabon was a respectable, responsible person, ready to disagree with rash and militant movements. This strike showed that Mabon was more popular in south Wales than Halliday, the President of the Union. Halliday was more hot-headed than him, less careful in his pronouncements and more ready to call the miners out on strike. The important thing for Mabon was caring for the miners and their families. They came first every time, not the Union, nor winning the battle. Seeing the miners’ children depending on the goodwill of charities, individuals, chapels and soup kitchens, as he saw in his native village in 1860, made him persuade the miners to consider compromise. He considered that there was a great responsibility on the owners. and in the 1875 strike, he came into contact with a Welsh speaking capitalist called David Davies of Llandinam.41 They had so much in common – both were staunch Calvinists and both promoted the world of Nonconformism and the chapels. But there was more of a gap between him and Thomas Halliday than with David Davies. David Davies understood Mabon better than Halliday.

By April 1875 the Rhondda and Aberdare Valley miners agreed that the strike should be settled by a small committee of owners and Trade Union leaders with the Chair to have the casting vote were they to fail to reach an understanding.

This policy was Mabon’s, not Halliday’s; and that was clearly understood in the meeting which was held in Merthyr Drill Hall. There was no agreement whatsoever between the Welshman and the Englishman. Another meeting was called, this time in Aberdare. Once

40 Ibid.

41 Mabon, Tarian y Gweithiwr (The Worker’s Shield), 2 April 1875, 3.

again, Halliday refused to compromise. Mabon continued to argue eloquently and, on that day, he won the debate. It was agreed that they should start the process of settling the disagreement.

Mabon believed in good will and co-operation between workers and their employers for the good of the allimportant industry. The case should be discussed in a friendly atmosphere and, if there was no way of reaching an agreement, an independent arbitrator would be called upon rather than resort to industrial warfare. The important thing was to keep the miner’s life free of strife and strikes so that every aspect of the industry would prosper. In his opinion, striking was a meaningless weapon and they, as miners, should aim for an understanding with the proprietors, leavened with reason and common sense in the long run.

He knew that justice was always on the side of the miner who was trying to defend his wages. The unfair scheme of the employers was to decrease the miner’s wage by ten per cent. By April 1875, the women and children of the miners were struggling. They managed to meet as a committee to settle it once and for all in the Royal Hotel in Cardiff. David Davies the proprietor of the Ocean Collieries in the Rhondda hypocritically and cleverly called on the miners to be mindful of their living, to be responsible people, saying that he had the right to greet them kindly, as he was a good friend to them. He constantly deceived the miners as, naturally, his aim was to represent the pit owners.

Mabon, Halliday and the miners were to be vanquished without some clever bargaining. They were forced to accept a reduction not of ten per cent but of twelve per cent. David Davies and his fellow capitalists wanted them to take up their tools and start working in the pits with a reduction of fifteen per cent. Mabon could not in all conscience accept such an insulting offer but agreed on behalf of the miners to accept a new agreement which meant that any change in the gradings of their wages from then on would be decided on a sliding scale. This is the wording: ‘On a sliding scale of wages, to be regulated by the selling price of coal.’

For William Thomas Lewis (later Lord Merthyr of Senghenydd) 42 who drew up the scheme, David Davies agreed – despite his own proposal – to chair the joint committees which would determine the sliding scale. Without Mabon, there was little hope, as the Sliding Scale was a scheme which pleased him greatly. His remittances on the plan can be seen especially in the magazine Red Dragon.

Mabon saw himself as a mediator who passionately loved the mining communities, his Calvinistic Methodist Chapel, his God and Saviour Jesus Christ. He brought principles of

42 R. T. Jenkins, ‘Syr William Thomas Lewis (1837-1914, Lord Merthyr of Senghenydd)’ Y Bywgraffiadur Cymreig, 528. He became very powerful in the coal trade and claimed to have devised the ‘Sliding Scale’ scheme though some others ascribe it to others such as H. Hussey Vivian, Lord Swansea and Mabon. See Elizabeth Phillips, Pioneers of the Welsh Coalfield (Cardiff, 1924), 256-61, but I believe that he, Mabon and David Davies were the three who planned it.

the orthodox religion of the Calvinistic Methodists into the life of the Union. He extolled negotiation as ‘the great principle of the arbitrator’ and as ‘a blessed principle’.

On 2 April 1875 the weekly paper Tarian y Gweithiwr (The Worker’s Shield) proclaimed Mabon’s stance:

The religion of our country teaches us this great principle as it always refers to one who is a Mediator between God and men… We are totally convinced that the only benefit to capital and labour is, not the death of the workers’ Craft Unions, but wholehearted cooperation from enabling both to be able to form amicable and conciliatory boards throughout the country, such as would foster peace and promote trade without sacrificing the independence of either side.43

When the strike occurred, Mabon wrote to the 4 June 1875 issue of Tarian y Gweithiwr seeing better days on the horizon. He said:

The twelve and a half per cent was lost but the principle was won; the war was lost but peace was won and great numbers of people are ready to commend it in the hope that South Wales will shortly be able to proclaim “There will be no more warfare”, and that in the future peace will reign in the relationship between our trade and our craft:‘ peace like the river and justice like the waves of the sea’. 44

This was Mabon’s attitude to the troubles in the southern coalfield in 1875 and, indeed, during his period as the Leader of the Miners’ Union. His view was that of, not only many of his fellow chapel goers who were miners, but also that of the Welsh and English press. Views like Mabon’s were seen regularly in the editorials of Gwladgarwr (The Patriot), Tarian y Gweithiwr, Y Faner (The Banner) the South Wales Daily News and Goleuad (The Illuminator), the weekly paper of the Calvinistic Methodists, and Y Tyst (The Witness), the weekly paper of the Welsh Independents.

For Y Gwladgarwr in 1875, the age of the strike was over. In Tarian y Gweithiwr, which was very sympathetic to Mabon, there was, for a short term, a fiery columnist who called himself Llwynog o’r Graig (The Fox from the Rock). During these years, particularly from October 1876 to August 1878, Llwynog o’r Graig mercilessly attacked the villainy of the gaffers and the avarice of the coalfields. Mabon had no better supporter at the outset of his career as a Trade Union pioneer than from Llwynog o’r Graig. He was a colourful character named Thomas Davies living in Abercwmboi, near Aberdare, originally from Cefneithin in Carmarthenshire and the father of S. O. Davies who was a Labour M.P. for Merthyr and Gibbon Davies, miners’ leader in Ammanford and district.45

Mabon prepared a verse summarising his philosophy to be recited at strike meeting:

43 Tarian y Gweithiwr, 2 April 1875.

44 Tarian y Gweithiwr, 4 June 1875.

45 For Thomas Davies and S. O. Davies, see Robert Griffith, S. O. Davies – A Socialist Faith (Llandysul, 1983); for Gibbon Davies, see D. Ben Rees, Cofiant Jim Griffiths, 89-90.

Meibion Llafur mawr eich lludded, Ymsymudwch yn y blaen, Cyned gwreichion eich iawnderau

Hen deimladau oll yn dân; Digon hir yr amser basiodd I ymdrybaeddu yn y baw; Mwy na digon i’r sawl welodd Rhannu angen un rhwng naw:

Unwch, unwch gyda’ch gilydd, Unwch beunydd bob yr un, Dyma’r unig ffordd obeithiol I wneud y glöwr du yn ddyn:

Pob rhyw slim feddyliwr slafaidd

Torwch, drylliwch, teflwch draw, Dewch i’r byd gael teimlo rhinwedd Eich gweithredoedd ddydd a ddaw.

Below is a translation:

Weary sons of Labour

Move onwards

May the sparks of your rights be kindled

Old feelings all on fire

The time has long passed For wallowing in the mire;

More than enough for those who saw

What one person needed being shared amongst nine:

Unite, unite together

Unite every day, every one This is the only hopeful way Of making the black miner a man:

Every taunting, slavish thinker

Break, destroy and then cast aside

Come into the world to feel the virtue of Your deeds in the days to come. 46

Mabon was at his best amidst his supporters, emphasising that ‘In unity there is Strength’. He did his best to convince the public of the virtues that were exemplified by the miners. Mabon raised the Welsh miner onto a special pedestal, stressing in particular his love for his home, family and his fellow workers. It was therefore not surprising for the editor of Tarian y Gweithiwr to say this about the miner on 30 July 1875:

The moral, virtuous and gracious conduct of scores of thousands of Welsh workers in the latest “strike” and the “lock-out” have caused the whole world to look with surprise, to wonder and to praise.

Propaganda of this sort, other than that spoken passionately by Mabon and printed in most Welsh language papers, was never in favour with most industrial workers besides

46 Tarian y Gweithiwr, 4 June 1875.

the slaves of the lamp.47 There was a reason for this, namely the hatred of many reasonable, respectable Tory-leaning people towards the working class. After all, the idea of Trade Unionism was condemned by the South Wales Association of Calvinistic Methodists in a quarterly meeting in Tredegar as long ago as 1831. So, throughout his life and especially from 1875 to 1910, Mabon was adamant that the image of the conscientious, cultured, chapel-going miner should be on a pedestal. Emyr Humphreys, the novelist and son of a Wesleyan Methodist minister, summed him up well:

The early strikes were led by chapel men and the call for justice was based on the adaptation of Christian principles. It was still possible for the miners’ leaders and the management and even the owners to attend the same chapel.50

One 48of our most perceptive novelists spoke accurately (and every word in the quotation is totally relevant to a biography of Mabon):

We see that the 1875 strike was not a strike for money in Mabon’s opinion but for a principle, namely the basic right of the worker to have a voice on the issue of his daily work. Neither he nor Halliday was ready to leave wages to the whim of the owner and that is why the Sliding Scale became a matter of principle to him. Wages would rise and fall according to the price the employer received for the coal.49

Dr E. W. Evans says:

The sliding scale was therefore a novelty only in so far as it would remove the friction which had previously attended changes in wages and make strikes or lockouts unnecessary.50

But, as Dr Evans suggests, Mabon was unaware of its main weakness, namely that it allowed the owners to sell under the appropriate price and to over-produce in order to make a profit. In the coalfield there were countless years of hardship and, doubtless, the owners accepted the best bargain every time. What Mabon wanted was to have a relationship of agreement and co-operation and that was also the wish of the miners belonging to the Loughor District.

It is not surprising that the miners made sure that he would be the spokesman at the Sliding Scale Committee. He kept the reins in his hands for many years as he was able to discuss terms and wages capably. An anonymous miner in Tarian y Gweithiwr said that the Miners’ Union should aim to appoint Welsh-speakers as officers and indeed, do everything in the native language.51 Mabon himself wanted this. He would like to see an independent Welsh-speaking Miners’ Union in south Wales. He went on an emotional

47 Editor, Tarian y Gweithiwr , 30t July 1875.

48 Emyr Humphreys, The Taliesin Tradition: A Quest for Welsh Identity (London, 1953), 196.

49 Ibid.

50 E. W. Evans, Mabon, 14.

51 Tarian y Gweithiwr , 25 July 1875, 4

journey to address miners in meetings in Llanelli, then to Ebbw Vales, Tredegar and the Cynon Valley and through every mining village in the Rhondda Valleys 52 but with little support.53 It was only a minority of miners who were on the same wavelength as him. On the need for trade unionism many of the miners were not convinced of the need and even fewer who felt like supporting a Welsh language Trade Union.

There was no grass roots support to be had for Mabon and his Welsh language trade union and there was pressure on the Loughor District to belong to the existing Miners Union which had its stronghold in the north west of England. This was most disappointing for Mabon as he realised that the majority of miners were happy enough to work in the colliery without belonging to a Union. Not even Mabon’s oratory could convince these men. A number of them saw him as a fanatic and doubted him and his passionate message. In 1875, Mabon failed to achieve his goal.54 What the majority of miners, who were willing to support his stance, wanted was a small trade Union responsible for a small number of collieries.

Between August and October 1875, Mabon and his main supporters, succeeded in setting up 24 Unions based on 24 districts, each one ultimately belonging to the General Miners Union and jealous of their independence.55 In the first Miners’ Conference held in April 1876, Mabon was elected President. But he soon heard at that conference an a huge amount of opposition and the atmosphere for extending the work was apathetic. After all, only some four thousand miners were trade unionists; the vast majority did not want to be members of the Miners’ Union.