www.delamed.org | www.djph.org Oral Health Volume 9 | Issue 1 April 2023 A publication of the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association Public Health Delaware Journal of

Delaware Academy of Medicine OFFICERS

S. John Swanson, M.D. President Killingsworth

Lynn Jones, FACHE President-Elect

Professor Rita Landgraf (Co-Chair) Vice President

Jeffrey M. Cole, D.D.S., M.B.A. Treasurer

Stephen C. Eppes, M.D. Secretary

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S. (Co-Chair)

Immediate Past President

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H. Executive Director, Ex-officio DIRECTORS

David M. Bercaw, M.D.

Lee P. Dresser, M.D.

Eric T. Johnson, M.D.

Erin M. Kavanaugh, M.D.

Joseph Kelly, D.D.S.

Joseph F. Kestner, Jr., M.D.

Brian W. Little, M.D., Ph.D.

Arun V. Malhotra, M.D.

Daniel J. Meara, M.D., D.M.D.

Ann Painter, M.S.N., R.N.

John P. Piper, M.D.

Charmaine Wright, M.D., M.S.H.P. EMERITUS

Robert B. Flinn, M.D.

Barry S. Kayne, D.D.S.

Delaware Public Health Association

Advisory Council:

Omar Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Chair

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H. Executive Director

Louis E. Bartoshesky, M.D., M.P.H.

Gerard Gallucci, M.D., M.H.S.

Melissa K. Melby, Ph.D.

Mia A. Papas, Ph.D.

Karyl T. Rattay, M.D., M.S.

William J. Swiatek, M.A., A.I.C.P.

Delaware Journal of Public Health

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H. Publisher

Omar Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Editor-in-Chief

Jeffrey M. Cole, D.D.S., M.B.A., F.A.G.D.,

Daniel J. Meara, M.S., M.D., D.M.D., M.H.C.D.S., F.A.C.S.

Guest Editors

Liz Healy, M.P.H.

Managing Editor

Kate Smith, M.D., M.P.H.

Copy Editor

Suzanne Fields

Image Director

Public

A publication of the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association

3 | In This Issue

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S.

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H.

4 | Guest Editor

Jeffrey M. Cole, D.D.S., M.B.A., F.A.G.D.

Daniel J. Meara, M.S., M.D., D.M.D., M.H.C.D.S., F.A.C.S.

6 | Toward Optimal Health for All: The American Dental Association Takes on Sugar and its Impact on Oral Health

George R. Shepley, D.D.S.

8 | A Public Health Update: The Oral Health of Delaware’s Kindergarten and Third Grade Children in 2022

Nicholas R. Conte Jr., D.M.D., M.B.A.

16 | Odontogenic Infections and a Pound of Prevention

Daniel J. Meara, M.S., M.D., D.M.D., M.H.C.D.S., F.A.C.S.

18 | More Premiums Spent on Patient Care? A Great Idea That Should Apply to Dental Insurance

Mark A. Vitale, D.M.D.

20 | The National Healthy People Initiative: History, Significance, and Embracing the 2030 Oral Health Objectives

Timothy L. Ricks, D.M.D., M.P.H., F.I.C.D., F.A.C.D., F.P.F.A.

26 | Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) and the Current State of Oropharyngeal Cancer Prevention and Treatment

Jacob P. Gribb, D.M.D

John H. Wheelock, D.D.S.

Etern S. Park, M.D., D.D.S.

30 | Global Health Matters January/February 2023

Fogarty International Center

42 | Update on Medication Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws

Barry C. Boyd, D.M.D., M.D., F.A.C.S.

44 | Reconsidering Autonomy: Ethical Reflections from the Frontlines of IDD Dental Care

Andrew Swiatowicz, D.D.S., D.A.B.D.S.M., F.A.G.D.

Brandon Ambrosino, M.T.S.

50 | The Mouth is the Mirror to the Body: Oral-Systemic Health

Roopali Kulkarni, D.M.D., M.P.H.

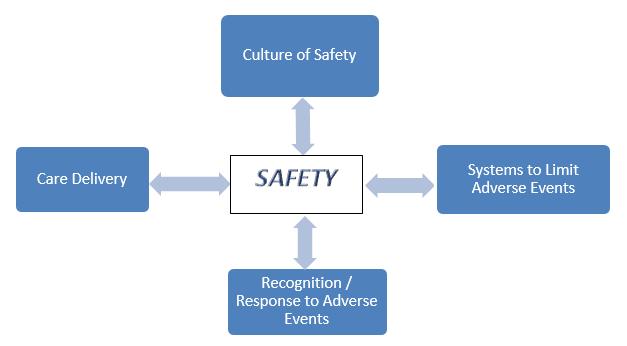

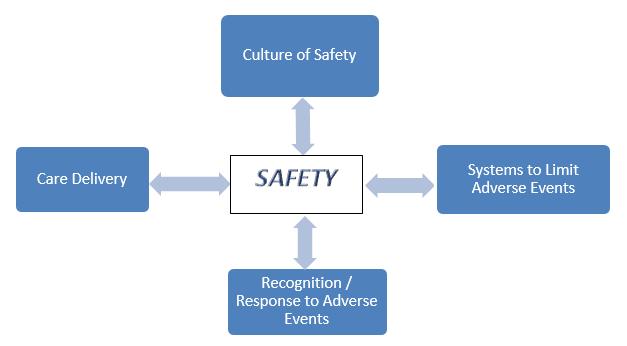

52 | Safety in the Dental Office

Louis K. Rafetto, D.M.D., M.Ed.

56 | Career and Technical Education: The Future of Delaware’s Healthcare Workforce

Jonathan S. Lee, B.A.

58 | Patient Safety at Forefront of OMS Anesthesia Delivery

Paul J. Schwartz, D.M.D.

60 | ORAL HEALTH LEXICON

62 | ORAL HEALTH RESOURCES

64 | Index of Advertisers

66 | Public Health Delaware Journal of Public Health Submission Guidelines

The Delaware Journal of Public Health (DJPH), first published in 2015, is the official journal of the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association (Academy/DPHA).

Submissions: Contributions of original unpublished research, social science analysis, scholarly essays, critical commentaries, departments, and letters to the editor are welcome. Questions? Write ehealy@delamed.org or call Liz Healy at 302-733-3989

Advertising: Please write to ehealy@delamed.org or call 302-733-3989 for other advertising opportunities. Ask about special exhibit packages and sponsorships. Acceptance of advertising by the Journal does not imply endorsement of products.

Copyright © 2023 by the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association. Opinions expressed by authors of articles summarized, quoted, or published in full in this journal represent only the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Delaware Public Health Association or the institution with which the author(s) is (are) affiliated, unless so specified.

Any report, article, or paper prepared by employees of the U.S. government as part of their official duties is, under Copyright Act, a “work of United States Government” for which copyright protection under Title 17 of the U.S. Code is not available. However, the journal format is copyrighted and pages June not be photocopied, except in limited quantities, or posted online, without permission of the Academy/DPHA. Copying done for other than personal or internal reference use-such as copying for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, for creating new collective works, or for resale- without the expressed permission of the Academy/DPHA is prohibited. Requests for special permission should be sent to ehealy@delamed.org

ISSN 2639-6378

Health Delaware Journal of

April 2023 Volume 9 | Issue 1

Oral health is a critical component of overall health and well-being, and it is also an essential aspect of public health. The condition of a person’s oral health can—at minimum—affect their ability to speak, eat, and socialize comfortably. Oral health problems can also lead to pain, infection, and other serious health issues, such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory infections, and diabetes, through a variety of mechanisms still being elucidated. April is Oral Cancer Awareness Month, highlighting the importance of early detection and prevention of this deadly disease. Oral cancer can occur in any part of the mouth, including the tongue, gums, lips, and tonsils. It is essential to maintain good oral hygiene habits and receive regular dental check-ups to detect any signs of oral cancer early. Sugar is one of the leading causes of tooth decay, which is the most common chronic disease among children and adults. When sugar is consumed, it interacts with the bacteria in the mouth to produce acid, which can erode the enamel on the teeth and cause cavities. It is crucial to limit the intake of sugary foods and drinks to maintain good oral health.

In addition to cavities, odontogenic infections can also occur due to poor oral hygiene. These infections are caused by bacteria that enter the tooth or gum tissue, causing swelling, pain, and other symptoms. In severe cases, they can lead to systemic infections, which can be life-threatening. In a national effort to improve the health and well-being of All Americans, the Healthy People 2030 initiative includes goals to improve oral health by promoting good oral hygiene habits, increasing access to dental care, and reducing the incidence of oral diseases.

One oral health issue that has gained attention in recent years is Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ). This condition can occur in individuals taking certain medications, such as bisphosphonates, which are commonly used to treat osteoporosis and other bone diseases. MRONJ can cause severe pain, swelling, and other complications, making it essential for individuals taking these medications to inform their dental care providers.

Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) also require specialized dental care. These individuals may have difficulty communicating or may have unique oral health needs due to their disabilities. It is essential to provide IDD individuals with the necessary dental care to maintain their oral health and overall well-being.

Safety in the dental office is critical for both patients and dental professionals. Dental offices must adhere to strict infection control protocols to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, and dental professionals must follow proper safety procedures when handling equipment and administering anesthesia. This is particularly relevant in the time of COVID-19 and related respiratory/droplet/airborne infections.

In this issue of the Delaware Journal of Public Health, guest editors Daniel J. Meara, MD, DMD, and Jeffrey Cole, DDS, MBA have brought together a diverse set of articles about these and other oral health, treatment, and workforce issues.

As always, we have included a resources section as well as a lexicon of terms. We welcome your feedback and thoughts!

IN THIS ISSUE

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H Publisher, Delaware Journal of Public Health

Doi: 10.32481/djph.2023.04.001

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Editor-in-Chief, Delaware Journal of Public Health

3

Oral Health

Jeffrey M. Cole, D.D.S., M.B.A., F.A.G.D. Program Director, General Practice Dentistry Residency Program, ChristianaCare

Daniel J. Meara, M.S., M.D., D.M.D., M.H.C.D.S., F.A.C.S. Chair, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery & Hospital Dentistry, ChristianaCare

During the planning for this oral health edition of the Delaware Journal of Public Health, Dr. Cole recalled a story that was shared by a professor while he was a student at Georgetown University School of Dentistry. The oral surgeon spoke about his first day of deployment to a field hospital during the Vietnam War. His commanding officer, a physician and surgeon told him, “Put your thumb in your mouth and stretch out the rest of your fingers. If you can touch it, it’s yours. The rest is mine. Now get to work!” While this encounter showed a unique approach to defining scope of practice, it also illustrated the disintegration that often existed between medicine and dentistry; mutual coexistence instead of collaboration in the treatment of patients. Integration of medicine and dentistry stresses the importance of oral health as an essential part of overall health. For decades, oral health has been defined by national and international groups in dentistry and medicine as the absence of disease and associated symptoms of the oral cavity and oropharynx. The FDI World Dental Federation has developed a definition for oral health that is designed to bridge the gaps that sometimes exist between oral healthcare and overall health of the body. The FDI defines oral health in this way:

“Oral health is multifaceted and includes the ability to speak, smile, smell, taste, touch, chew, swallow, and convey an array of emotions through facial expressions with confidence and without pain, discomfort and disease of the craniofacial complex.”

They further identify attributes of oral health.

“Oral health is a fundamental component of health and physical and mental well-being. It exists along a continuum influenced by the values and attitudes of individuals and communities. Oral health reflects the physiological, social and psychological attributes that are essential to the quality of life. Oral health is influenced by an individual’s changing experiences, perceptions, expectations, and ability to adapt to circumstances.”

When strategically addressing the promotion of oral health, there is a lot of discussion around access to care, but less attention to two essential components of success in this area: utilization of services and oral health literacy. It is with this background that we hope this edition of the Delaware Journal of Public Health will inspire the multidisciplinary team of healthcare providers and advocates to continue to add to their comprehensive understanding of oral health, the challenges we face, and the opportunities we have in working together. You cannot have systemic health without oral health.

Doi: 10.32481/djph.2023.04.002

4 Delaware Journal of Public Health - April 2023

April 2023

The Nation’s Health headlines

Online-only news from The Nation’s Health newspaper

Stories of note include:

Child vaccination rates falter as misinformation, skepticism grow

Teddi Nicolaus

Local abortion supporters help patients navigate access as laws shift

Kim Krisberg

End to COVID-19 emergency policies could set back health

Mark Barna

Wastewater surveillance warrants further investment, development

Kim Krisberg

Q&A: New CDC office could help make inroads on work to combat disparities in US rural health

Maaisha Osman

Belt, buckle & boost: Keep your kids safe in the car

Teddi Nicolaus

Vaccine uptake gets a boost when people know others are on board

Maaisha Osman

https://www.thenationshealth.org/

HIGHLIGHTS FROM The NATION’S HEALTH A PUBLICATION OF THE AMERICAN PUBLIC HEALTH ASSOCIATION 5

Toward Optimal Health for All: The American Dental Association Takes on Sugar and its Impact on Oral Health

George R. Shepley, D.D.S.

President, American Dental Association; General Dentist, Private Practice

For 164 years, the American Dental Association (ADA) has been leading the national discourse on oral health. From advocating for critical legislation to improve health equity to driving the evidence-based insights that advance the profession, the ADA’s endeavors are propelled by a fundamental commitment to making people healthy.

This commitment bears that, as a community of essential healthcare providers, the ADA has an imperative to be champions for overall wellbeing and to take a stand on issues that could impede the improvement of public health. It’s an imperative we’ve lived up to.

Consider, for example, the stand the Association has taken on smoking and tobacco products, whose deleterious oral and systemic health effects are well known. Among many actions in recent years, the ADA has supported the regulation of e-cigarettes and synthetic nicotine products.

The Association also continues to guide clinicians in offering smoking cessation advice to their patients. A 2022 study in the Journal of the American Dental Association found that dentists’ chairside counsel can be influential—smoking cessation advice from a dental team member is associated with an 18 percent increase in the number of times a patient tries to quit smoking.1

The study is a nod to the great potential for dentistry (both as a professional community and as individuals) to be active partners, alongside medical colleagues, in helping patients achieve whole-body health. Oral health is integral to overall health— research reflects the relationship between oral disease such as periodontal disease and systemic conditions that include type 2 diabetes2 and cardiovascular disease.3

Dental-medical integration in primary care is gaining prominence, and increasingly more dental students are being trained to have an innate sense of their contributions to a patient’s overall wellbeing. In addition to seeing the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, emerging professionals are understanding their role in not solely treating disease, but in actively promoting health, too.

Although dentistry is our area of expertise, the concern of whole-body health remains a key area of focus for the ADA as we meet our constitutional objective to encourage public health.

In 2023, the Association has a renewed opportunity to address a public health issue whose impact dentists see directly in their work—from caries to periodontitis, to the systemic conditions that have oral manifestations, like inflammation and diabetes. A common denominator the Association wants to address is the overconsumption of sugar.

The effect of sugar on a person’s oral health is hardly a new frontier in dentistry. For many children, early lessons on caring for their teeth include brushing, flossing, and avoiding candy to avoid cavities. Yet, in patients of all ages, the overconsumption of sugar is continually associated with diseases that go well beyond the mouth. But the mouth is often where it starts, with the excessive intake of sugary beverages, sweet snacks, and processed foods.

In a 2012 article for Nature, authors Robert H. Lustig, Laura A. Schmidt, and Claire D. Brindis write, “Evolutionarily, sugar was available to our ancestors as fruit for only a few months a year (at harvest time), or as honey, which was guarded by bees. But in recent years, sugar has been added to nearly all processed foods, limiting consumer choice. Nature made sugar hard to get; man made it easy.”4

Excessive sugar intake can also be tied to foods that are specifically marketed to consumers as good for them. Some yogurts, for example, can have as many as 32 grams of sugar per serving. For perspective, there are 39 grams of added sugar in a 12-ounce can of Coke.

In turn, the American Heart Association (AHA) reports that the average American consumes 77 grams of sugar a day5—well beyond the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s recommendation that people over age three have no more than 50 grams of added sugars a day.6 The AHA’s recommendation is more conservative, suggesting that the daily intake of added sugars should be limited to 36 grams for men and 25 grams for women.

With its policies on diet and nutrition, the ADA, too, acknowledges the benefit of healthy diets that avoid added sugars as a step toward optimal oral health. We also recognize the value of professional education, public awareness, patient information, and continued research on nutrition’s role in oral and overall health.

This year, the ADA is taking its work on diet and nutrition further with the establishment of the Presidential Task Force on Sugar, Nutrition, and Diet. Current members represent the ADA Board of Trustees, Council on Advocacy for Access and Prevention, Council on Governmental Affairs, Council on Scientific Affairs, along with general ADA membership. The group also includes experts on dietetics and endocrinology.

The Task Force was formed to review existing ADA policies on sugar, nutrition, and diet, and propose changes to expand the ADA’s involvement with other healthcare stakeholders and facilitate dental-medical collaboration on the topic.

Doi: 10.32481/djph.2023.04.003

6 Delaware Journal of Public Health - April 2023

Last fall, the Biden-Harris administration hosted the White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health—the first meeting of its kind in 50 years. As outlined during the conference, key actions of the national strategy include investing in creative research approaches regarding the relationship between nutrition, disease, and comprehensive health; advancing research on the prevention and treatment of diet-related diseases; and strengthening and diversifying the nutrition workforce.

The ADA Task Force’s review of the White House strategy will help shape its recommended revisions to current ADA policy with the goal of further driving oral health, nutrition, and improved health outcomes.

Efforts like these are positioning the ADA to not only spearhead the national discourse on oral health, but to become a respected leader in shaping healthcare at large.

Just as vital as our collective efforts are the thousands of clinicians who have the individual power to help their communities—one visit and one patient at a time. This, too, is where we improve population health— by arming our patients with the knowledge that enables them to make informed choices.

We should remember the old adage: knowledge is power. Both knowledge and power can create a sense of agency and self-advocacy for patients. And a sense that—along with their dentist, physician, and other healthcare providers—they are a member of their own healthcare team. And that their decisions, whether to try to quit smoking or to be more aware of their sugar intake, can bring them one step closer to being their healthiest selves.

Together, with the large-scale work of the ADA and other organizations, each step brings all of us closer to healthier communities, a healthier nation, and a healthier world.

The very publication of the Delaware Journal of Public Health helps to make this vision possible, with the platform it provides to inform its diverse readership on public health research, policy, practice, and education per its mission.

I’d like to thank the following individuals for providing this venue to highlight oral health’s vital role in public health:

• Guest Editor Dr. Jeffrey Cole, who is a former ADA president and currently the program director of the General Practice Dentistry Residency Program at Christiana Hospital in Wilmington.

• Guest Editor Dr. Daniel Meara, current chair of the Commission for Continuing Education Provider Education and chair of Christiana Hospital’s Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Hospital Dentistry.

• Dr. Brian McAllister, current chair of the National Commission on Recognition of Dental Specialties and Certifying Boards and attending staff for the General Practice Dentistry Residency Program at Christiana Hospital.

Thank you for being among the Delaware dentists who are driving public health forward as clinicians, educators, and leaders.

Dr. Shepley may be contacted at shepleyg@ada.org

REFERENCES

1. Yadav, S., Lee, M., & Hong, Y.-R. (2022, January). Smokingcessation advice from dental care professionals and its association with smoking status: Analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2015-2018. J Am Dental Assoc, 153(1), 15–22.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2021.07.009

2 Wu, C. Z., Yuan, Y. H., Liu, H. H., Li, S. S., Zhang, B. W., Chen, W., . . . Li, L. J. (2020, July 11). Epidemiologic relationship between periodontitis and type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Oral Health, 20(1), 204.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-020-01180-w

3. Zardawi, F., Gul, S., Abdulkareem, A., Sha, A., & Yates, J. (2021, January 15). Association between periodontal disease and atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases: Revisited. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 7, 625579

https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2020.625579

4 Lustig, R. H., Schmidt, L. A., & Brindis, C. D. (2012, February 1). Public health: The toxic truth about sugar. Nature, 482(7383), 27–29.

https://doi.org/10.1038/482027a

5. American Heart Association. (2022, Jun). How much sugar is too much?

https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/sugar/ how-much-sugar-is-too-much

6. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2022, Feb). Added sugars on the new nutrition facts label.

https://www.fda.gov/food/new-nutrition-facts-label/added-sugars-newnutrition-facts-label

7

A Public Health Update: The Oral Health of Delaware’s Kindergarten and Third Grade Children in 2022

Nicholas R. Conte Jr., D.M.D., M.B.A.

Dental Director, Bureau of Oral Health and Dental Services, Division of Public Health, Delaware Department of Health and Social Services; Prosthodontist, Private Practice.

INTRODUCTION

Good oral health means more than healthy teeth and gums. Oral diseases, such as tooth decay and gum disease, are multifactorial in causation and affect general health status. Oral health problems usually involve significant social and cultural factors that require many resources and partners to implement prevention and treatment services.1 Social determinants of health include income, education, occupation, geographic implications, and cultural beliefs.2 Access to oral health care is affected by similar social, cultural, economic, geographic, and structural factors, but more so by the separation of the oral health from the health care system. People and communities with inadequate access to oral health care experience notable social and economic burdens.3 Tooth decay is a serious public health problem that can affect a child’s overall health and well-being. It can lead to pain and disfigurement, low self-esteem, nutritional problems, and lost school days. Children with oral health problems are three times more likely to miss school due to dental pain, and absences caused by pain are associated with poorer school performance.4

The National Oral Health Surveillance System (NOHSS) is a collaborative effort between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Oral Health and the Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors (ASTDD). NOHSS monitors the burden of oral disease, use of the oral health care delivery system, and the status of community water fluoridation on national and state levels. NOHSS captures oral health surveillance indicators based on data sources and surveillance capacity available to most states.

The Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) and the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors (NACDD) developed a framework for chronic disease surveillance indicators, including oral health indicators for adult and child populations.

Children’s oral health data from NOHSS include indicators for caries experience, untreated tooth decay, and dental sealants. More specifically, these indicators measure the percentage of third grade students with caries experience, the percentage of third grade students with untreated tooth decay, and the percentage of third grade students with dental sealants on at least one permanent molar tooth.5

Recognizing the need for community level oral health status and dental care access data, ASTDD developed the Basic Screening Survey (BSS). The primary purpose of the BSS is to provide a framework to collect oral health data efficiently and inexpensively in a consistent manner. By collecting data in a standardized manner, communities and states can compare their data with data collected by other organizations or agencies using the same methodology; and/or data from previous surveys.

The BSS model has two basic components: direct observation of a child’s oral cavity and questions asked of, or about, the child being screened.6

To assess the current oral health status of Delaware’s elementary school children, the Bureau of Oral Health and Dental Services (BOHDS) within the Delaware Department of Health and Social Services, Division of Public Health coordinated an inaugural statewide oral health survey of kindergarten and third grade children attending Delaware’s public schools. The survey was conducted during the 2021-2022 school year among kindergarten and third grade children receiving a BOHDS dental screening at 40 schools. BOHDS received 4,236 oral health surveys and performed in-person screenings on 1,601 kindergarten and 1,517 third grade children. The kindergarten screening survey had not been completed previously in Delaware and the previous third grade BSS was completed in 2012. These two cohorts were selected because third grade oral health is a national comparison point used to assess the health of school age children, as there is a good mixture of primary and permanent dentition present. The kindergarten group allows for baseline assessment of oral health upon entry into the school system.

DATA SOURCE AND METHODS

BOHDS employees and Delaware state employees conducted the survey, screening children in kindergarten and third grade from a representative sample of Delaware’s non-virtual public schools. The preliminary planning phase for the basic screening survey started more than six months prior to the in-school screenings taking place by collaborating with the Delaware Department of Education (DOE) to gain approval for the survey and to determine the procedure for distribution of the forms throughout the state, as well as obtaining individual consent to participate from the families of the students. To determine the schools included in the BSS, technical assistance was provided by an ASTDD consultant. Assuring the sampling scheme is correct is essential to submit the data for inclusion into the U.S. Oral Health Surveillance System, NOHSS.

To assure representation by geographic region and socioeconomic status, the sampling frame was ordered by county, then by the percentage of students in each school identified by DOE as being low-income and eligible for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). If a school with only third grade was selected, the appropriate kindergarten feeder school7 within the district was added to the sample. A systematic probability proportional to size sampling scheme was used to select a sample of 25 third grade schools. As four of the selected third grade schools did not have kindergarten students, the appropriate kindergarten feeder schools were added to

Doi: 10.32481/djph.2023.04.004

8 Delaware Journal of Public Health - April 2023

the sample for a total of 28 schools representing 25 sampling intervals. Fifteen additional schools volunteered to participate, and their data were included in the results.

After developing data collection forms and the survey letters, the schools were contacted and arrangements were made for an in-person screening date, allowing ample time for the forms to be distributed and returned to BOHDS.

All the screeners were trained and calibrated by a representative from ASTDD and are actively licensed as either a dentist or a dental hygienist in the State of Delaware. The following definitions were used by the screeners to consistently categorize observations:

Decay experience refers to a child having tooth decay in the primary (baby) and/or permanent (adult) teeth in his or her lifetime. Decay experience can be past (fillings, crowns, or teeth that have been extracted because of decay) or present (untreated tooth decay or cavities) and refers to having untreated decay or a dental filling, crown, or other type of restorative dental material present at the time of the screening.

If left untreated, tooth decay can have serious consequences, including needless pain and suffering, difficulty chewing (which compromises children’s nutrition and can slow their development), difficulty speaking, and lost days in school. Untreated decay is used to describe dental caries or tooth decay that have not received appropriate treatment.

Dental sealants are plastic-like coatings applied to the chewing surfaces of back teeth. The applied sealant resin bonds into the grooves of teeth to form a protective physical barrier. Most tooth decay in children occurs on these surfaces. Sealants protect the chewing surfaces from tooth decay by keeping germs and food particles out of these grooves. Screeners utilized visual inspection to identify the presence of a dental sealant.

Each child who completed an in school, in-person screening received an oral health kit that included a toothbrush and toothpaste, age-appropriate dental education, oral health literature, and a dental resource guide. A copy of the screening result was sent home for the student’s parent or guardian to review. For students where an urgent need was identified, BOHDS conducted case management and connected the family to a provider to address their oral health needs.

The information was collected using both the returned paper and electronic survey forms and the in-person screening. It included: grade, age, race/ethnicity, presence of untreated decay, presence of treated decay, presence of dental sealants on the permanent first molar teeth, and urgency of need for dental care. BOHDS used the BSS clinical indicator definitions and data collection protocols authored by ASTDD, titled Basic screening surveys: An approach to monitoring community oral health. 6 The forms included an optional parent questionnaire which collected information on dental insurance, time since last dental visit, whether the child had a toothache or other dental problems in

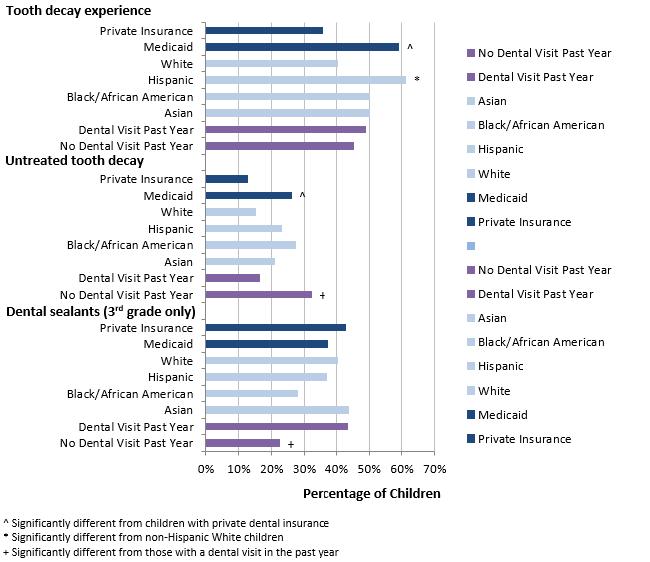

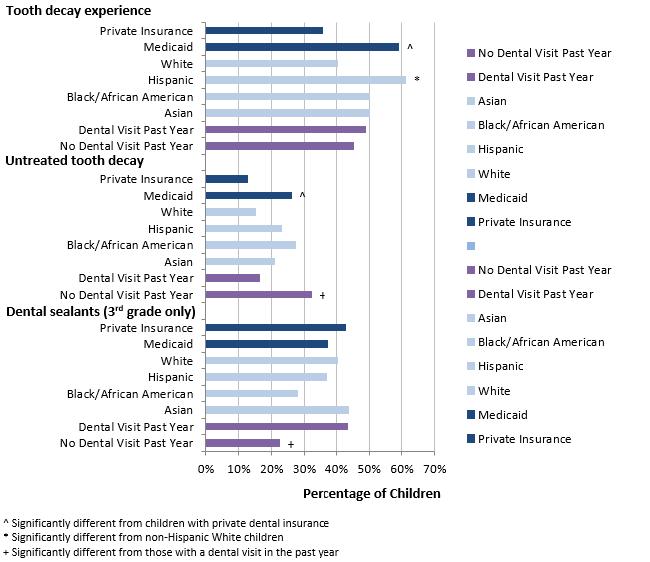

Figure 1. Prevalence of Tooth Decay Experience and Untreated Tooth Decay, and Dental Sealants Among Kindergarten and Third Grade Children by Type of Dental Insurance, Race/Ethnicity, and Dental Visit in the Past Year, Delaware, 2021-2022

9

Table 1. Prevalence of Tooth Decay Experience and Untreated Tooth Decay in the Primary and Permanent Teeth Among Kindergarten and Third Grade Children Combined by Selected Characteristics, Delaware, 2021-2022

Lower CL = Lower 95% confidence limit, Upper CL = Upper 95% confidence limit

* Significantly different than reference (p<0.05)

the last year, and whether the child needed dental care during the last year but was unable to obtain the needed care. All statistical analyses were performed using the complex survey procedures within SAS (Version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Sample weights were used to produce population estimates based on selection probabilities.9

RESULTS

There were 8,847 kindergarten and 3rd grade children enrolled in the participating schools for the 2020-2021 academic year. Three thousand one hundred and eighteen received a dental screening for a response rate of 35%. The following is a summary of the results of the 3,118 in-person screenings completed (figure 1, table 1). Forty-five percent of Delaware’s kindergarten children have at least one tooth with decay experience. Twenty-two percent of Delaware’s kindergarten children have untreated tooth decay. Since permanent molars generally appear in the mouth at six years of age, information on protective dental sealants in kindergarten was not included.

Regarding third graders, 53% of Delaware’s third grade children have at least one tooth with decay experience and 19% of Delaware’s third grade children have untreated tooth decay. Only 38% of Delaware’s third grade children were found to have protective dental sealants in present (table 2).

Delaware children with Medicaid have a significantly higher prevalence of decay experience and untreated tooth decay than those with private dental insurance. Over 60% of surveyed Hispanic/Latinx children had tooth decay experience compared to over 40% of surveyed non-Hispanic White children. Non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic Asian children had over 50% tooth decay experience compared to 40% for non-Hispanic White children. The prevalence of untreated tooth decay is significantly higher among children without a dental visit in the past year (over 30%) compared to those with a dental visit (over 20%). Among third grade children, those without a dental visit in the past year are significantly less likely to have protective dental sealants.9

Characteristic Decay Experience Untreated Decay Survey Total Percent Yes Lower CL Upper CL # With Data Percent Yes Lower CL Upper CL ALL CHILDREN 3,118 48.3 41.4 55.2 3,118 20.4 13.8 27.0 Race/Ethnicity Asian 175 50.2 39.8 60.7 175 20.8 8.1 33.6 Black/African American 603 50.0 38.5 61.6 603 27.3 16.8 37.8 Hispanic/Latinx 632 61.2* 56.4 65.9 632 23.1 17.6 28.7 White (reference) 1,450 40.4 34.1 46.7 1,450 15.0 10.5 19.5 County Kent 763 47.8 42.3 53.3 763 19.6 14.6 24.6 New Castle 1,392 47.8 36.0 59.5 1,392 20.6 9.1 32.0 Sussex 963 50.7 43.5 57.9 963 21.0 17.2 24.9 Dental Insurance Private Insurance (reference) 1,475 35.5 27.8 43.2 1,475 12.8 8.6 16.9 Medicaid 1,221 59.1* 52.2 65.9 1,221 26.0* 17.3 34.7 Dental Visit in Last Year No 673 45.2 40.0 50.5 673 32.2* 25.6 38.8 Yes (reference) 2,402 49.0 41.2 56.7 2,402 16.4 10.1 22.8 Toothache/Cavities in Last Year No (reference) 2,397 38.0 32.7 43.3 2,397 12.9 9.1 16.7 Yes 608 79.8* 71.4 88.1 608 40.1* 29.3 50.9 Needed Care but Couldn’t Obtain No (reference) 2,715 45.9 38.9 52.8 2,715 16.6 10.7 22.6 Yes 300 64.6* 58.3 70.9 300 43.3* 36.3 50.2

10 Delaware Journal of Public Health - April 2023

Lower CL = Lower 95% confidence limit, Upper CL = Upper 95% confidence limit

* Significantly different than reference (p<0.05)

DISCUSSION

The results of this BSS demonstrate that Delaware’s third graders have experienced less decay than the national average yet are comparable to the national average for untreated decay. Fifty-three percent of Delaware’s third grade children have at least one tooth with decay experience, which is lower than the national average of 60%. It was found that 19% of Delaware’s third grade children have untreated tooth decay, similar to the national average of 20%; and only 38% of Delaware’s third grade children have protective dental sealants, lower than the national average of 42%.

The decay experience and untreated decay rates for kindergarteners are higher than national averages. Forty-five percent of Delaware’s kindergarten children have at least one tooth with decay experience, higher than the national average of 42%. Twenty-two percent of Delaware’s kindergarten children have untreated tooth decay, higher than the national average of 15%.

More importantly, the results indicate that significant oral health inequities exist in Delaware, with tooth decay being more common in children from low-income households and among Hispanic children

LIMITATIONS

It is important to understand the intent and limitations of a screening survey. A dental screening is not a thorough clinical examination and does not involve making a clinical diagnosis resulting in a treatment plan. A screening is intended to identify definitive dental or oral lesions and is conducted by dentists, dental hygienists, or other appropriate health care workers, in accordance with applicable state law. The information gathered through a screening survey is at a level consistent with monitoring the national health objectives found in Healthy People 2030, the United States Public Health Service’s 10-year agenda for improving the nation’s health.11 Surveys are cross sectional (looking at a population at a point in time) and descriptive (intended for determining estimates of oral health status for a defined population).6

It should be noted that the Delaware survey was conducted during the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the lower prevalence of dental sealants may be partially due to limited access to preventive dental services at that time.

Characteristic Dental Sealants on Permanent Molars Survey Total Percent Yes Lower CL Upper CL ALL THIRD GRADE CHILDREN 1,508 37.5 26.2 48.8 Race/Ethnicity Asian 88 43.7 22.9 64.6 Black/African American 289 27.8 13.3 42.2 Hispanic/Latinx 307 37.1 26.1 48.2 White (reference) 702 40.5 27.5 53.4 County Kent 344 28.4 14.9 41.9 New Castle 703 47.0 28.3 65.6 Sussex 461 22.0 7.8 36.2 Dental Insurance Private Insurance (reference) 757 42.8 27.9 57.6 Medicaid 534 37.3 26.8 47.8 Dental Visit in Last Year No 300 22.5* 11.4 33.6 Yes (reference) 1,179 43.5 32.2 54.7 Toothache/Cavities in Last Year No (reference) 1,167 39.7 28.3 51.1 Yes 285 39.6 27.7 51.4 Needed Care but Couldn’t Obtain No (reference) 1,310 41.0 30.0 52.1 Yes 143 32.0 18.0 46.0

11

Table 2. Prevalence of Dental Sealants on Permanent Molar Teeth Among Third Grade Children by Selected Characteristics, Delaware, 2021-2022

DENTAL CARE IN DELAWARE

More than two hundred families responded to the questionnaire that they had no dental insurance or were unsure of having any benefit. This information is important to consider as many individuals need assistance with navigating through healthcare benefits, understanding eligibility and determining potential of out-of-pocket costs before obtaining care.

Dental case management is one method that BOHDS has utilized in this effort to address these inequities and improve the overall oral health of these and other high-risk populations. Increasing access to care by the removal of barriers to care delivery ultimately results in connecting families to providers who match their preferences, thus establishing a dental home.13

To facilitate accessibility of a dental home, it is necessary to develop trust. Understanding a family’s preferences, cultural beliefs, and ability to navigate the health care system is as critical as delivering care. For families to follow through with oral and dental health care, providers must educate them on the importance of preventive practices. Improving health literacy is needed to understand the connection between oral and systemic health. Offering appointment assistance regarding potential transportation options, provider schedules, and after care proves valuable to establishing a meaningful connection. Lastly, families can make well-informed decisions and be comfortable in their selection of an oral health provider when they receive administrative assistance to help determine benefit eligibility, comply with referrals, and pay responsibly.

To further address care needs, BOHDS developed the First Smile Delaware Dental Resource Guide in 2020. The resource guide is distributed during all community outreach events and public engagement and is available both electronically and in print.14 It is designed to assist the public with finding a dentist that is right for them individually. The guide helps patients understand which dental benefits are covered, how to apply for dental insurance, and how to access oral health services in Delaware. BOHDS continually monitors the effectiveness of the resource guide and its content through consumer and dental provider feedback and updates the document annually. BOHDS plans to conduct a phone survey in the fourth quarter of 2023 with providers that have accepted referrals to assess their overall experiences, garner feedback on what has been working well and identify opportunities for improvement.

NEXT STEPS

BOHDS expects the next BSS to be conducted for kindergarteners and third graders during the 2026-2027 academic year. While the BSS kindergarten and third grade screening surveys have a periodicity schedule of every five years, BOHDS’ daily activity is similar in nature. BOHDS engages in community outreach activities and an in-school screening program throughout the year. The Delaware Smile Check Program is a school-based screening program that provides dental education and preventive services within the school, and includes dental case management for any family that identifies that they are without a dental home. If an urgent or emergent situation is identified during a screening visit that requires treatment, a BOHDS staff member will reach out to the parent or guardian and try to connect the child to a provider within 48 hours. Similar to the BSS, any child who is seen as part of the Delaware Smile Check Program receives customized dental education and oral health instruction in addition to a toothbrush, toothpaste, and a dental resource guide. A copy of the screening result is sent home with the child

for the guardian’s review and the school nurse receives a copy for the student’s school health record. BOHDS will look to evaluate the effectiveness of the case management activities at the end of 2023 to determine what percentage of families were connected to a dental provider and if this has had impact on the burden of oral disease in the state. Since its inception in 2016, the Delaware Smile Check Program has provided services to more than 15,000 children throughout the state.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

Tooth decay is preventable. Connecting children to a permanent dental home will work towards lowering the incidence of dental caries and the prevalence of untreated decay. To help lower the burden of childhood oral disease, BOHDS will continue to coordinate with Federally Qualified Health Centers and private dental providers across the state to link families in need of a provider to a dental home. When Delaware reaches the public health goal of lowering the burden of oral disease, our residents will experience an improved quality of life.

Dr. Conte may be contacted at Nicholas.conte@delaware.gov

REFERENCES

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, Feb). Disparities in oral health. https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/oral_health_disparities/index.htm

2. Fédération Dentaire Internationale World Dental Federation. (2015). The challenge of oral disease – A call for global action. The Oral Health Atlas. 2nd ed. Geneva.

3. Tiwari, T. & Franstve-Hawley, J. (2021, Sep 30). Addressing oral health of low-income populations—A call to action. Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open, 4(9), e2125263. Doi: 10.1001.jamanetworkopen.2021.25263

4. Jackson, S.L., Vann, W.F., Kotch, J.B., Pahel, B.T., & Lee, J.Y. (2011, Oct). Impact of poor oral health on children’s school attendance and performance. Am J Public Health, 101(10), 1900-1906. Doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.200915

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, May). Oral health data. Child indicators. https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealthdata/overview/childindicators/index.html

6. Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors. (2017, Jul). Basic screening surveys: An approach to monitoring community oral health head start and school children. July 2017. https://www.astdd.org/docs/bss-childrens-manual-july-2017.pdf

7. Law Insider. (2023). Feeder pattern. Law Insider Inc. https://www.lawinsider.com/dictionary/feeder-pattern

9. Delaware Bureau of Oral Health and Dental Services. (2022, Feb). Delaware oral health and dental services data brief - the oral health of Delaware’s kindergarten and third grade children 2022. https://www.dhss.delaware.gov/dhss/dph/hsm/ohphome.html

11. States Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople

13. Greenberg, B.J., Kumar, J.V., & Stevenson, H. (2008, Aug). Dental case management increasing access to oral health care for families and children with low incomes. Journal of the American Dental Association, 139(8), 1114-1121. Doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0314

14. Delaware Department of Health and Social Services. (n.d.). Dental resource guide. https://www.dhss.delaware.gov/dhss/dph/hsm/files/dentalresourceguide.pdf

12 Delaware Journal of Public Health - April 2023

Financial Aid

2023 Workforce Initiative

Application open until funds are depleted

Eligibility:

• U.S. Citizen or permanent resident (I-151 or I-551 card)

• One year of residency in the State of Delaware

• Enrolled in an approved degree-granting program or certificate in Nursing, Medical Assistant, Dental Assistant, Physician Assistant, Behavioral Health or Allied Health

Requirements:

• Completed online application

• Online self-certification form

• Copy of most recent signed Delaware tax return (personal and/or parents, if dependent)

• Proof of Delaware residency (driver’s license, vehicle registration, voter’s registration card)

• Letter of Acceptance

• Promissory Note and Loan Agreement

Funding:

• Funded by the Delaware American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) for shortages in the healthcare field due to the COVID-19 pandemic

• Loan amount averages between $2,500 to $15,000 annually

Repayment:

• Interest-free while enrolled in an approved degree program

• Repayment begins 6 months after graduation depending on the length of the degree program

• Repayment plan options will depend on the degree type

- Certification programs: 1 to 3-year plans

- Associates, Bachelors, or Masters Degree programs: 5 to 7-year plans

- Doctoral (Ph.D.) programs: 7 to 11-year plans

Note: Terms of repayment of loans are covered through the promissory note and loan agreement

To apply, visit: https://delamed.org/student-financial-aid/

Contact: Giselle Bermudez, MS, Student Financial Aid Coordinator

email: gbermudez@delamed.org

phone: 302-733-1122

This program is supported by State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds thru the Department of Treasury and State of Delaware [SLFRP0139].

13

All concussions are brain injuries

A concussion is caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head or body that causes the head and brain to move quickly back and forth. During Brain Injury Awareness Month, the Delaware Coalition for Injury Prevention’s Brain and Spinal Cord Injury Team wants Delawareans to know that all concussions are brain injuries.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), concussion symptoms are headache or “pressure” in the head; nausea or vomiting; and dizziness or balance problems. The injured individual may have blurred or double vision, light or noise sensitivity, ringing in ears, confusion, and difficulty concentrating or remembering The person may feel slowed down, tired, sad, irritable, and be more emotional or not feel right. Toddlers and infants will not stop crying, cannot be consoled, and will not nurse or eat.

Someone with a concussion may appear dazed or lose consciousness, though that does not always occur. The injured person may have slurred speech, move clumsily, appear off balance, and be slow to answer questions. They could exhibit a change in behavior, mood, or personality, including irritability or aggressiveness; and be more tired than usual. A change in sleep pattern could occur.

If you have a concussion, stop your activity immediately and get evaluated by a medical provider. Do not try to judge the severity yourself. Delaware law says all children must be evaluated prior to returning to any sporting activity.

For more information and training, visit the CDC’s Headsup website: https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/ Another resource is the State Council for Persons with Disability (https://scpd.delaware.gov/); access the Brain Injury Fund Assistance.

Brain Injury Association of Delaware announces virtual conference series

The Brain Injury Association of Delaware (BIADE) is hosting its 2023 Annual Conference in March through a virtual webinar series. The series will be held every Thursday in March from 6:00 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. and are free to survivors and caregivers.

BIADE says the sessions share information on new advancements in care, service, and program options for survivors, and teach attendees how to advocate for traumatic brain injury survivors.

The webinar schedule is:

Session I: March 2, 2023, 6:00 p.m.

Following the Data of Brain Injury in Delaware

Dr. Gurpreet Kaur, MD, MBA, Delaware Health Information Network (DHIN) and Dee Rivard, State Council for Persons with Disabilities

Session II: March 9, 2023, 6:00 p.m.

Cognitive-Communication Disorders Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Maggie Kalinec, Defy Therapy Service

Session III: March 16, 2023, 6:00 p.m.

Gaps in Service for Brain Injury Survivors Dr. Terry Harrison-Goldman, Nemours Children’s Health

Session IV: March 23, 2023, 6:00 p.m.

Brain Injury and Seizures - What We Know And What We Don’t Dr. John Cheng, Christiana Care Health System

Session V: March 30, 2023, 6:00 p.m.

Traumatic Brain Injury: Not Just One Moment in Time - Long-Term Health Effects after TBI

Dr. Dawn R. Tartaglione, DO, Bayhealth Neurosurgery.

Register at www.biade.org

Watching all five webinars can earn 5.0 CEU credits for Speech Language Pathologist, Occupational Therapy, and Physical Therapy, plus Nurse Practitioners and Nursing (pending application).

For more information, contact BIADE at 302-3462083.

14 Delaware Journal of Public Health - April 2023

of Public Health March 202

From the Delaware Division

Learn about chronic kidney disease during National Kidney Month

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), also called Chronic Renal failure, is a condition where the kidneys gradually lose function over time, eventually leading to complete kidney failure. CKD is caused by a variety of factors, including high blood pressure, diabetes, and certain inherited disorders. Symptoms of CKD may not appear until the disease has progressed significantly, and may include fatigue, swelling, and changes in urination patterns. CKD can be managed with lifestyle changes and medical treatment, but in advanced stages, a kidney transplant or dialysis may be necessary.

Prevent CKD with these tips from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):

• Prevent high blood pressure by self-monitoring and following your treatment plan.

• Schedule regular check-ups with your health care provider to monitor kidney function and detect diseases early when they are more treatable. This is important for individuals with diabetes, who are at a higher risk for developing CKD.

• Follow a healthy diet that is low in salt, sugar, and unhealthy fats.

• Get regular physical activity.

• Avoid harmful substances such as tobacco, excessive alcohol, and certain medications.

• Manage other health conditions such as heart disease and liver disease

Call a doctor immediately if you have chest pain or shortness of breath. See a provider for changes in urination patterns, including increased frequency, decreased volume, or the appearance of blood in the urine. Other symptoms of impaired kidney function are swelling in the face, legs, or feet; anemia; nausea or vomiting; and itchy skin

The Division of Public Health (DPH) offers free sixweek self-management workshops to adults who have or care for someone living with a chronic condition. For more information, visit Healthy Delaware or call 302-208-9097.

Delaware residents diagnosed with End Stage Renal Disease can apply to the Chronic Renal Disease Program for financial assistance. Reach the Division of Medicaid & Medical Assistance online, call the Delaware Help Line at 211, or call 302-424-7180.

Seven public libraries offer kiosks for telehealth appointments and more Delawareans can access telehealth, legal support, and employment assistance for free at seven public libraries. Private, soundproof kiosks are available at the Woodlawn, Route 9, Georgetown, Laurel, Lewes, Milton, and Milford public libraries through a Delaware Libraries pilot program.

Each kiosk offers high-speed Internet, an iPad, and a hand sanitizer station. With the tablets, Delawareans can Zoom, Skype, and use other videoconferencing software to hold virtual appointments with health care providers, connect with social service specialists about Medicaid, and apply for food, housing, and other essential benefits. The kiosks can also be used for interviews, job training, legal appointments, and education.

The kiosks fit up to three people, are wheelchair accessible, and offer hand sanitizer stations. Reserve a kiosk at https://delawarelibraries.libcal.com/appointments/. This is a grant-funded project from several local and national nonprofits and the federal government. More kiosks are planned at additional libraries. Chromebooks, Wi-Fi hotspots, and blood pressure cuffs can also be borrowed from public libraries throughout the state.

In Delaware:

• Telehealth appointments can occur through video as well as audio-only technologies.

• Patients can access telehealth services if there is an established physician-patient relationship.

• Informed consent is required and must comply with current HIPAA requirements.

• Prescriptions may be prescribed through a telehealth visit once the physician-provider relationship is established.

• Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance carriers reimburse for telehealth services if those in-person services are covered.

For more information, visit GetConnected.DelawareLibraries.org and https://www.matrc.org/ Visit the 2022 National Telehealth Conference Summary B and Telehealth.HHS.gov to learn how to use telehealth and prepare for a virtual visit.

15 The DPH Bulletin – March 2023 Page 2 of 2

A urine test and a blood test can check for kidney disease. niddk.nih.gov

Division of Libraries

Odontogenic Infections and a Pound of Prevention

Daniel J. Meara, M.S., M.D., D.M.D., M.H.C.D.S., F.A.C.S. Chair, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery & Hospital Dentistry, ChristianaCare

THE PROBLEM

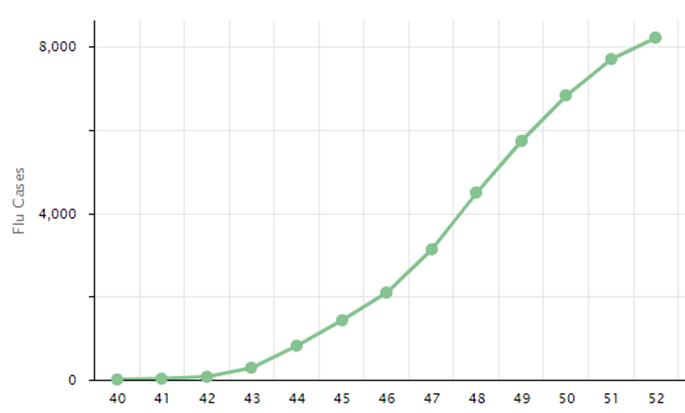

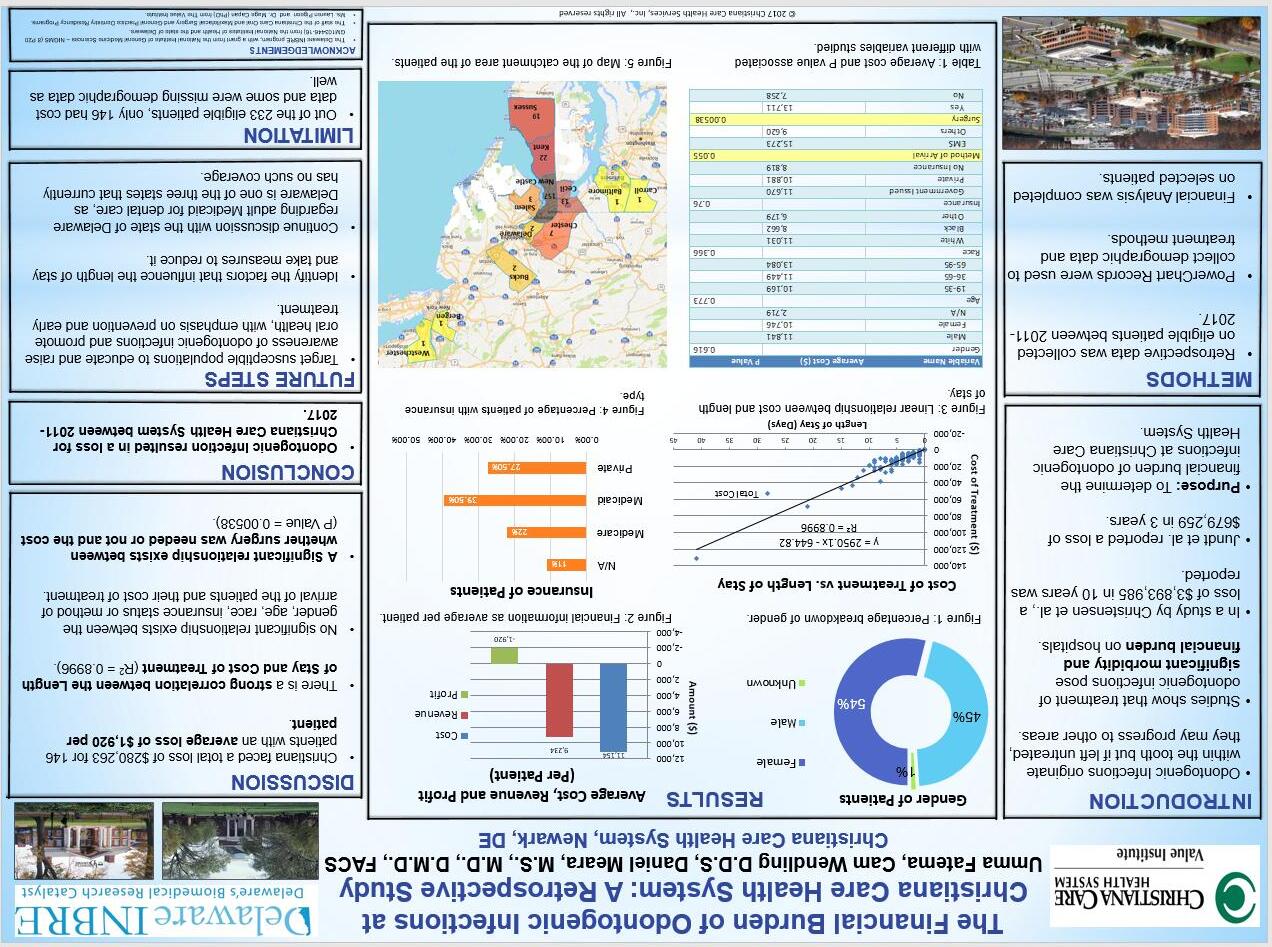

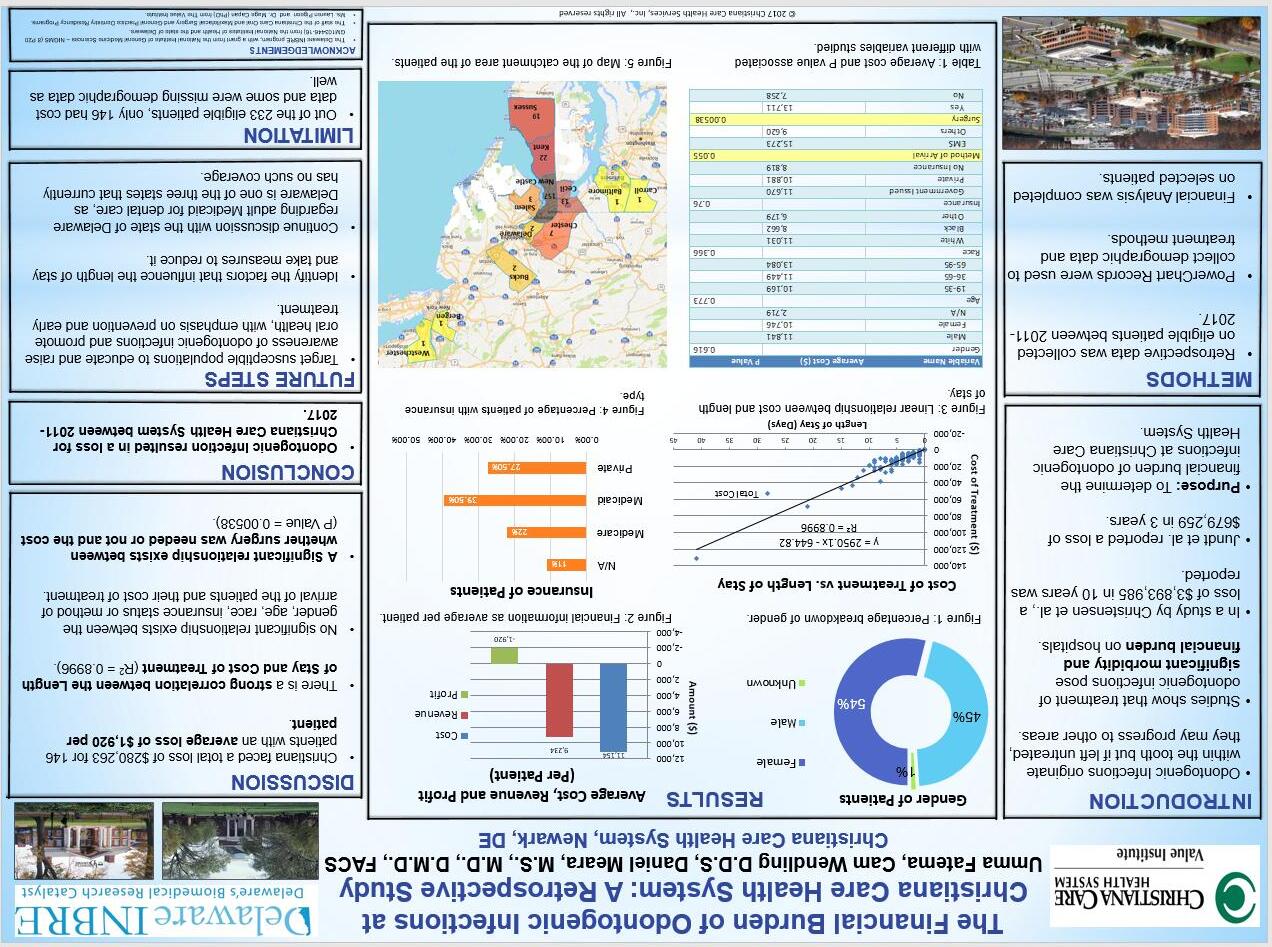

Oral health is essential for systemic health and overall well-being. However, odontogenic infections plaque the healthcare system, with estimates that the cost is over $200 million dollars annually in the United States.1 Further, almost all of these odontogenic infections are preventable when individuals have proper access and engagement in dental services. A 2018 Delaware IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence (INBRE) study out of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Hospital Dentistry, at Christiana Care Health System, noted that from 2011-2017 a total of 146 patients, with complete cost data, were treated for odontogenic infections, resulting in a total cost of care of over $1.62 million dollars (Figure 1). Christiana Care Health System, with the state’s only oral/ maxillofacial surgery unit and as a tertiary referral center, treats about 33 cases per year at an average cost of over $11,000 per patient.

This problem stems from the fact that approximately 25% of the US population (approximately 82 million Americans) have no dental insurance.2 Moreover, vulnerable populations such as Medicaid eligible patients have limited state-based dental benefits. In Delaware, adults with Medicaid dental benefits have access to $1000 per year, though another $1500 can be available for ‘emergency’ care. Once the benefit limits have been reached, any future costs are out of pocket for the patient until the next benefit reset.

THE RESULT

The result is a disconnect between oral and system health, which impacts the health of the individual as well as the health of the population. Simply, one cannot have true health without oral health being optimized.

OPPORTUNITIES

Integration of oral health metrics and outcomes assessment into risk-based contracts will be an essential lever to drive change, make oral health a priority, and provide the financial structure for sustained and longterm success. Further, coordination of care, primary care in the dental office or dental care in the primary care office, and expanded team care with dental specialists embedded on teams dedicated to diabetic and cardiac patients much like is already done for cleft and oral cancer patients is needed.

In addition, social determinants of health greatly impact health, especially oral health. Limited transportation options, healthy food deserts, smoking and vaping shops on neighborhood street corners, and lack of oral health education are significant challenges for individuals and communities.

PREVENTION

The focus must be on moving away from access to care only when an acute issue arises, such as an odontogenic infection, to a system of care that prioritizes prevention of disease, maintenance of health and care based on what is best for the patient and not just on what is feasible from a financial standpoint.

ACHIEVING CHANGE

As was detailed in my 2018 DJPH article on oral health and achieving population health, we all must think differently to realize meaningful change. Ultimately, to drive change and for access and quality of oral healthcare to improve, silos must be removed, outcomes must be measured, incentives must align, innovation must be fostered, successes must be highlighted and insurance must be affordable. Health and the future of America depends on it!

Dr. Meara may be contacted at dmeara@christianacare.org

REFERENCES

1. Meara, D. J. (2018). Oral health is essential to achieving population health: Thinking differently to achieve meaningful change. Delaware Journal of Public Health, 4(1), 50–51. 10.32481/ djph.2018.01.011

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2000). Oral health in America: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health.

Doi: 10.32481/djph.2023.04.005

16 Delaware Journal of Public Health - April 2023

17

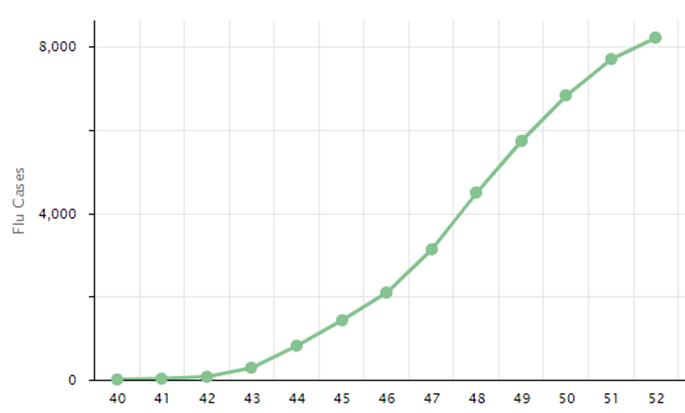

Figure 1. The Financial Burden of Odontogenic Infections at Christiana Care Health System.

More Premiums Spent on Patient Care? A Great Idea That Should Apply to Dental Insurance

Mark A. Vitale, D.M.D. Chair, New Jersey Dental Political Action Committee, New Jersey Dental Association; President, Dental Lifeline Network, New Jersey

On November 8, 2022, 72% of Massachusetts voters said ‘yes’ to a ballot measure known as Question 2, setting the stage for changing how dental insurance operates in the United States. So, what is Question 2?

Question 2 establishes a minimum Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) requirement for dental insurers and enacts a number of reporting and oversight laws in Massachusetts. MLR is the percentage of premium revenue insurers take in, compared to how much they spend on actual health care services. MLR has been an insurance measuring method for decades, but it gained real traction when the Affordable Care Act (ACA) became law. It requires health plans to calculate their MLR to ensure they spend no less than 80-85% of premium revenue on health care services, but dental insurers are not included in this law. Massachusetts’ Question 2 mirrors what the ACA accomplished by requiring dental insurance companies to spend at least 83% of premium revenue on dental services as opposed to executive salaries or other administrative costs. Like the ACA, dental insurers spending less than 83% must refund the difference to patients.

MLR puts patients at the forefront of the health care system, where they should be. For patients enrolled in dental plans, MLR ensures the investment of their premium dollars is maximized in the form of actual dental care services. It is designed not only to show insurers’ investment in actual care, it also incentivizes insurers to “be better” because they must refund the difference in premium if they don’t meet the 83% MLR. And that is why a large majority of voters in Massachusetts asked for this accountability and value.

The potential benefits of this public policy become even more important when we consider how dental insurance is designed. Unlike health insurance, dental plans are similar to gift cards with an annual maximum the plans pay on behalf of patients; once the annual benefit maximum in the plans is reached, the insurer is done paying for care. Because of this, insurers are motivated to dissuade patients from seeking dental care since unused dental benefit premiums revert back to the insurer as profit. MLR flips that incentive on its head. Under minimum MLR requirement model, insurers will seek ways to encourage patient care so that they can avoid having to issue rebates for not spending enough on actual dental care. MLR laws give patients an assurance that their investment in dental insurance has real value.

In the wake of the landslide decision in Massachusetts, at least eleven states are pursuing MLR legislation for dental plans. Legislators in many states are taking note of the bipartisan and overwhelming voter support in Massachusetts. It is clear that voters are ready to have their insurance companies held accountable. While opponents to MLR try to question the importance of MLR, their testimony so far has shown they are only interested in protecting the status quo. In particular, they want to maintain the incentive structure where premiums not paid out in care mean a better bottom line for insurers. It’s rather simple; patients having more spent on their care will improve their oral health and overall health. The MLR requirement for major medical plans enacted in 2010 has a proven track record of helping health insurance customers. It is about time dental insurance companies provide this consumer protection and be incentivized to spend a greater percentage of the premium dollars they collect on actual patient care.

Dr. Vitale may be contacted at mvitale590@aol.com

Doi: 10.32481/djph.2023.04.006

18 Delaware Journal of Public Health - April 2023

If you have chronic pain, chronic illness, or diabetes, or are a cancer survivor, there are FREE workshops that can help you live better. You’ll meet others like you, learn skills to manage your illness, and start to redefine your life and your health.

EMPOWERED.

or

to

or

more. Chronic Disease | Diabetes | Chronic Pain | Cancer Feeling better starts

feeling 19

Call 302-990-0522

visit HealthyDelaware.org/SelfManagement

register

learn

with

The National Healthy People Initiative: History, Significance, and Embracing the 2030 Oral Health Objectives

Timothy L. Ricks, D.M.D., M.P.H., F.I.C.D., F.A.C.D., F.P.F.A. Indian Health Service, Department of Health and Human Services

ABSTRACT

Since 1979, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has worked with multiple subject matter experts and the public to develop and issue a set of ambitious, measurable objectives known as “Healthy People.” These objectives are aimed at improving the health of the nation issued at the start of each decade, and feature specific targets to be achieved at the end of the decade. The fifth iteration, Healthy People 2030, consists 358 measurable public health objectives associated with evidence-based interventions. Oral health is represented by 11 specific objectives aimed at reducing dental caries in children and adolescents, reducing untreated decay and periodontal disease in adults, and promoting evidence-based prevention strategies, including community water fluoridation, dental sealants, oral cancer screenings, and, most importantly, increasing access to dental services. In fact, access to the oral health care system for children, adolescents, and adults is identified as a Healthy People 2030 Leading Health Indicator – a high-priority Healthy People 2030 objective selected to drive action toward improving health and well-being – for the second straight decade. With the continued promotion of multidirectional integration of oral health and overall health across multiple disciplines, many – including policymakers, oral health professionals, other healthcare professionals, dental and public health organizations, and community advocates – have a role in affecting the outcome of the Healthy People 2030 oral health objectives.

INTRODUCTION

In 1979, Surgeon General Dr. Julius Richmond issued a landmark report entitled Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention 1 This report established the framework for “Healthy People,” a collection of science-based, measurable national objectives released each decade that are aimed at improving the health of the nation. Healthy People 2030 marks the fifth decade of these national health priorities, and oral health has had multiple objectives in each of these iterations. Informed by the most current science and breakthroughs, Healthy People 2030 includes measurable oral health objectives with targets, features a set of Leading Health Indicators, and highlights five key social determinants of health: economic stability; education access and quality; social and community context; health care access and quality; and the neighborhood and built environment. As the recent Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges report demonstrates, all five of these social determinants of health, when favorable, “contribute to better oral health and facilitate favorable oral health trajectories during the life course.”2

LAYING THE FOUNDATION: HEALTHY PEOPLE 1990

Healthy People 1990 focused on health across the life span with overarching goals to decrease mortality in infants and adults and to increase independence among older adults. Objectives were organized into three areas: preventive services, health protection, and health promotion. In that first iteration of Healthy People, oral health objectives were classified under the health protection area, and included 12 very ambitious objectives:3

i. By 1990, the proportion of nine-year-old children who have experienced dental caries in their permanent teeth should be decreased to 60 percent (baseline was 71 percent).

ii. By 1990, the prevalence of gingivitis in children six to 17 years old should be decreased to 18 percent (baseline was 23 percent).

iii. By 1990, in adults the prevalence of gingivitis and destructive periodontal disease should be decreased to 20 percent and 21 percent, respectively (baselines were 25 percent and 23 percent, respectively).

iv. By 1990, no public elementary or secondary school (and no medical facility), should offer highly cariogenic foods or snacks in vending machines or in school breakfast or lunch programs (no baseline data).

v. By 1990, virtually all students in secondary schools and colleges who participate in organized contact sports should routinely wear proper mouth guards (no baseline data).

vi. By 1990, at least 95 percent of school children and their parents should be able to identify the principal risk factors related to dental diseases and be aware of the importance of fluoridation and other measures in controlling these diseases (no baseline data).

vii. By 1990, at least 75 percent of adults should be aware of the necessity for both thorough personal oral hygiene and regular professional care in the prevention and control of periodontal disease (baseline was 52 percent).

Doi: 10.32481/djph.2023.04.007

20 Delaware Journal of Public Health - April 2023

viii. By 1990, at least 95 percent of the population on community water systems should be receiving the benefits of fluoridated drinking water (baseline was 60 percent).

ix. By 1990, at least 50 percent of school children living in fluoride-deficient areas that do not have community water systems should be served by an optimally fluoridated school water supply (baseline was six percent).

x. By 1990, at least 65 percent of school children should be proficient in personal oral hygiene practices and should be receiving other needed preventive dental services in addition to fluoridation (no baseline data).

xi. By 1990, a comprehensive and integrated system should be in place for periodic determination of the oral health status, dental treatment needs, and utilization of dental services of the U.S. population (no baseline data).

xii. By 1985, systems should be in place for determining coverage of all major dental public health preventive measures and activities to reduce consumption of highly cariogenic foods (no baseline data).

ORAL HEALTH AS A LEADING HEALTH INDICATOR

By the time Healthy People 2020 was published, Healthy People had significantly expanded to almost 1,300 objectives (1,111 measurable objectives), including 33 oral health objectives,4 in 42 topic areas. One of the most significant aspects of Healthy People 2020 was the development of Leading Health Indicators, a small subset of objectives selected to spotlight high-priority health issues and actions that can be taken to drive progress toward the Healthy People goals and targets and address morbidity and mortality. In recognition of its role in overall health, oral health was selected as one of the 12 topics. More specifically, Healthy People 2020 Oral Health Objective OH-7, which had a stated goal to “increase the proportion of children, adolescents, and adults who used the oral health care system in the past year” and called for a 10 percent improvement over a baseline access rate of 44.5 percent at the beginning of the decade, was selected as a Leading Health Indicator for oral health and one of 26 Leading Health Indicators overall. Unfortunately, despite the increased attention to oral health access, there was very little change, and the final access rate at the end of the decade was 43.3 percent accessing dental care in the past year, far from the goal of 49.0 percent.5

STREAMLINED APPROACH: HEALTHY PEOPLE 2030

Launched in 2020 and streamlined to promote foci on a reduced number of objectives, Healthy People 2030 includes 358 specific and measurable public health objectives with targets and that are associated with evidence-based interventions. The vision for this fifth iteration of Healthy People is “a society in which all people can achieve their full potential for health and well-being across the lifespan.”6 The overarching goals for Healthy People 2030

not only build on previous iterations, but also place additional emphasis on advancing health equity, health literacy and social determinants of health:

• Attain healthy, thriving lives and well-being free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death.

• Eliminate health disparities, achieve health equity, and attain health literacy to improve the health and well-being of all.

• Create social, physical, and economic environments that promote attaining the full potential for health and wellbeing for all.

• Promote healthy development, healthy behaviors, and wellbeing across all life stages.

• Engage leadership, key constituents, and the public across multiple sectors to take action and design policies that improve the health and well-being of all.

The Healthy People 2030 oral health goal is to “improve oral health by increasing access to oral health care, including preventive services.” As part of the overall streamlining of Healthy People objectives, oral health (OH) objectives have been reduced from 33 in Healthy People 2020 to 11 in Healthy People 2030:7

• OH-01: Reduce the proportion of children and adolescents with lifetime tooth decay (baseline is 48.4 percent and the target is 42.9 percent by 2030).

• OH-02: Reduce the proportion of children and adolescents with active and untreated tooth decay (baseline is 13.4 percent and the target is 10.2 percent).

• OH-03: Reduce the proportion of adults with active or untreated tooth decay (baseline is 22.8 percent and the target is 17.3 percent).

• OH-04: Reduce the proportion of older adults with untreated root surface decay (baseline is 29.1 percent and the target is 20.1 percent).

• OH-05: Reduce the proportion of adults aged 45 years and over who have lost all their teeth (baseline is 7.9 percent and the target is 5.4 percent).

• OH-06: Reduce the proportion of adults aged 45 years and over with moderate and severe periodontitis (baseline is 44.5 percent and the target is 39.3 percent).

• OH-07: Increase the proportion of oral and pharyngeal cancers detected at the earliest stage (baseline is 29.5 percent and the target is 34.2 percent).

• OH-08: Increase use of the oral health system (baseline is 46.2 percent and the target is 45.0 percent).

• OH-09: Increase the proportion of low-income youth who have a preventive visit (baseline is 75.8 percent and the target is 79.9 percent).

• OH-10: Increase the proportion of children and adolescents who have dental sealants on one or more molars (baseline is 37.0 percent and the target is 42.5 percent).

• OH-11: Increase the proportion of people whose water systems have the recommended amount of fluoride (baseline is 72.8 percent and the target is 77.1 percent).

21

As with Healthy People 2020, Healthy People 2030 has prioritized specific objectives as Leading Health Indicators, naming 23 specific objectives that “impact major causes of death and disease in the United States.”8 Oral Health objective (OH-8) “increase use of the oral health care system” is one of the Healthy People 2030 Leading Health Indicators.

WHAT IS YOUR ROLE IN HEALTHY PEOPLE 2030?

One of Healthy People 2030’s overarching goals is to engage leadership, key constituents, and the public across multiple sectors. This overarching goal recognizes the imperative of enlisting and engaging diverse users across sectors to achieve the Healthy People 2030 targets. With the continued multidirectional integration of oral health and overall health across multiple disciplines, many professionals affect the outcome of the Healthy People 2030 oral health objectives. Healthcare professionals and others can advocate for policies that enhance access to dental care, especially for underserved and vulnerable populations. Public health professionals can promote evidence-based prevention strategies, such as early access to dental care, improving oral health literacy of patients and the public, dental sealants, topical fluorides, and community water fluoridation. Private practitioners can do their part by becoming knowledgeable about the oral health objectives and adopting evidencebased policies and practices to promote access to care for those at high risk for dental caries or periodontal disease, including historically marginalized communities, people living in poverty, and people living in geographically isolated areas (i.e., dental health professional shortage areas). Finally, medical providers and community partners can promote oral health through education and referral to oral health professionals.

The Healthy People 2030 Federal Oral Health Workgroup – comprised of representatives from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, and the Indian Health Service – has developed several specific strategies that oral health professionals can adopt to help the nation reach its 2030 targets on the oral health objectives. These strategies include:

1. Promote and use evidence-based prevention practices;

2. Improve skills and comfort of oral health professionals to provide care to children as soon as the first tooth erupts or by age 1;

3. Embrace oral health workforce delivery models that improve access to care for underserved and vulnerable populations;

4. Use an integrated approach to improve access to care, working collaboratively with medical and community partners; and

5. Work with state and local agencies and other advocates to educate decision makers about the benefits of community water fluoridation.

Healthy People offers an array of evidence-based resources related to oral conditions listed in the oral health objectives. These can be found at https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/ browse-objectives/oral-conditions/evidence-based-resources and include:

• Treatment of periodontitis for glycemic control in people with diabetes mellitus

• Pit and fissure sealants versus fluoride varnishes for preventing dental decay in the permanent teeth of children and adolescents

• Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents

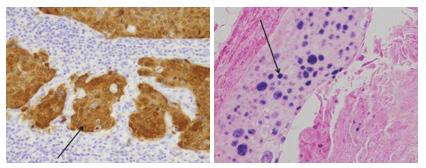

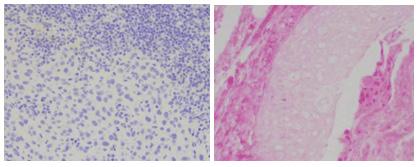

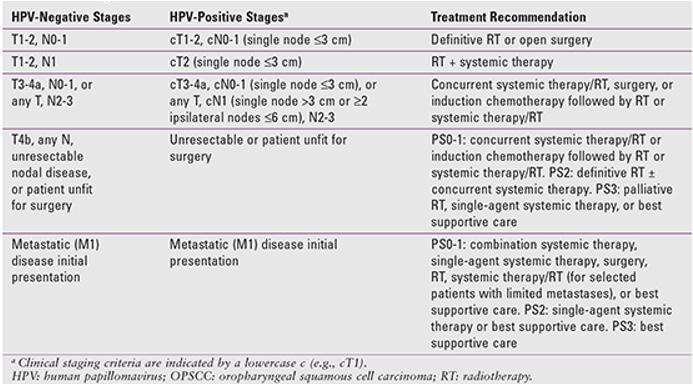

• Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges