Far from La Paz:

Re-dreaming Indigenous Textiles

Far from La Paz: Re-dreaming Indigenous Textiles

A Textile Design Thesis by Dakota Tracht

Title: Far from La Paz: Re-dreaming Indigenous Textiles

A Textile Design Thesis by Dakota Tracht

May 22, 2015

A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts in Textile Design at the Department of Textiles at the Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Rhode Island

By Dakota Tracht 2015

Approved by master’s thesis committee:

Anais Missakian, Professor, Department of Textiles, Thesis Chair

Jesse Asjes, Assistant Professor, Department of Textiles, Thesis Advisor

Lorraine de Wet Howes, Professor Emerita, Department of Apparel, Thesis Advisor

Abstract

Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges’ short story “The Garden of Forking Paths” questions the idea of linear history, instead suggesting that the nature of life exists in parallel universes, multiple spaces, and discontinuous temporalities. Borges’ central character, Yu Tsun, lives on the threshold of infinite space and time and brute destiny. As the story develops, Yu Tsun begins to realize that life exists in narrative virtuality, and the sequence of events in which he is involved are not only non-linear, but they occur in multiple realms. Yu Tsun eventually ends up at the beginning of his the story, where the past becomes the future. The magical realism in Borges’ story inspires me to think of history as best told through fictions

in which multiple paths converge, co-existing in temporalities of past, present and future. This lens of history inspires my artistic practice of looking at my own story with Bolivia, and the native textiles that influence my work.

The indigenous textiles of the Aymara and Tiwanaku embody a unique spiritual language. Both of these Bolivian, pre-Columbian civilizations once inhabited the Andes mountains around the contemporary city of La Paz, Bolivia, my hometown. Symbolism and depictions of mythic beings in these textiles straddle the threshold between spiritual and material worlds.

This thesis collection embodies personal history through the medium of magical realism. It is through my narrative connection to these textiles that I re-dream the weaving of Aymara and Tiwanaku to express a deep lived experience. Cloth embedded with meaning and history, and the clothes I make with them, represent a hybrid personal identity, which pushes and pulls, back and forth between the real and the fantastic. Sculptural yet physically wearable, I knit, print, coat, dye and drape to create a textile fiction where these garments live on the threshold between ready to wear garments and couture imaginations.

Dedication

For the men and women of the Millma knitwer factory in Bolivia, who taught me my craft and gave me an appreciation for textile making and for my parents, Laurie and Arthur, for opening my eyes to the world of textiles, and for sharing their knowledge and vision throughout the years.

“Killing and torture and sorcery are real and death is real. But why people do these things, and how the answers to that question affect the question- that is not answerable outside the effects of the real carried through time by people in action. That is why my subject is not the truth of being but the social being of truth, not whether facts are real but what the politics of their interpretation and representation are.”

- Michael Taussig

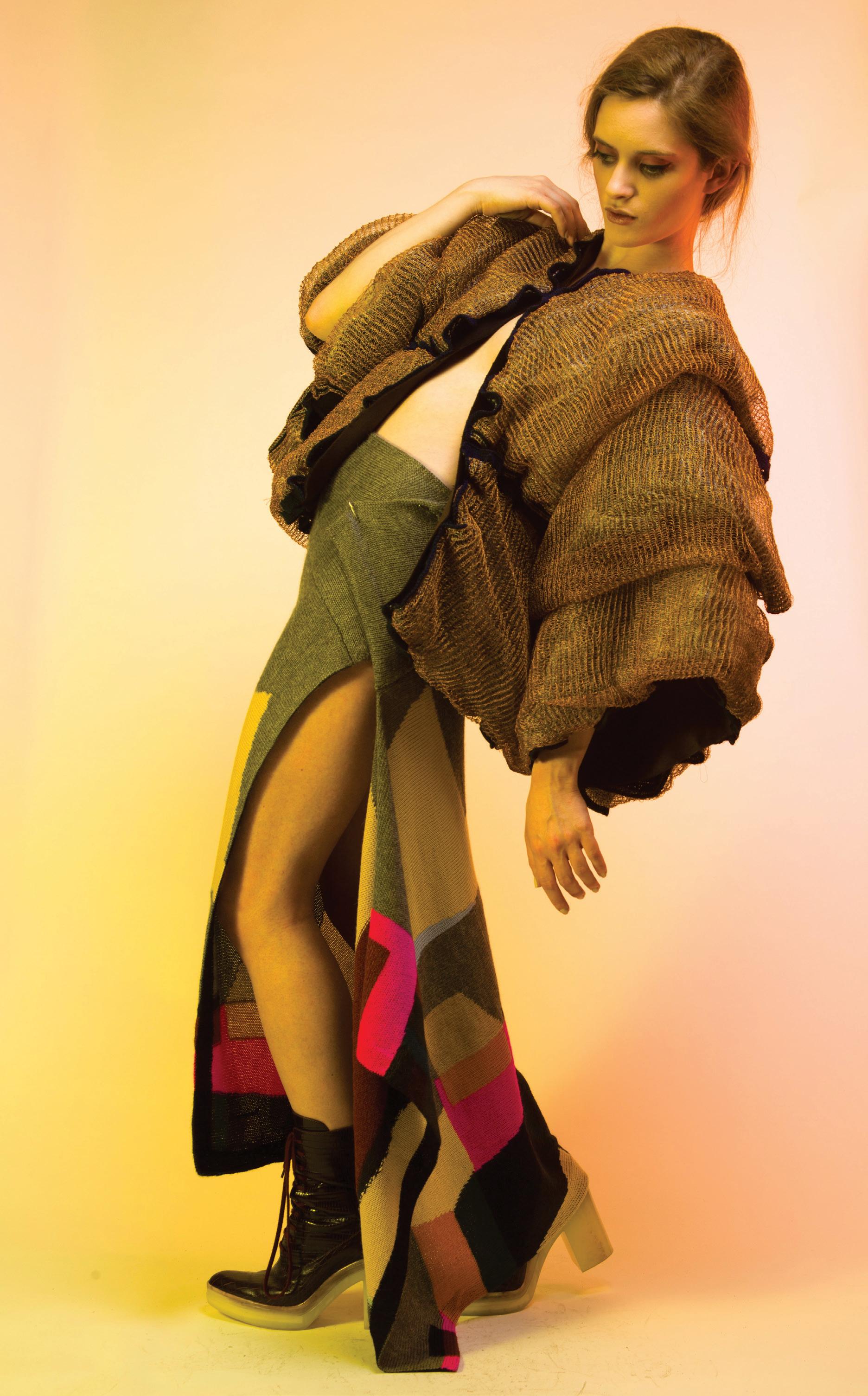

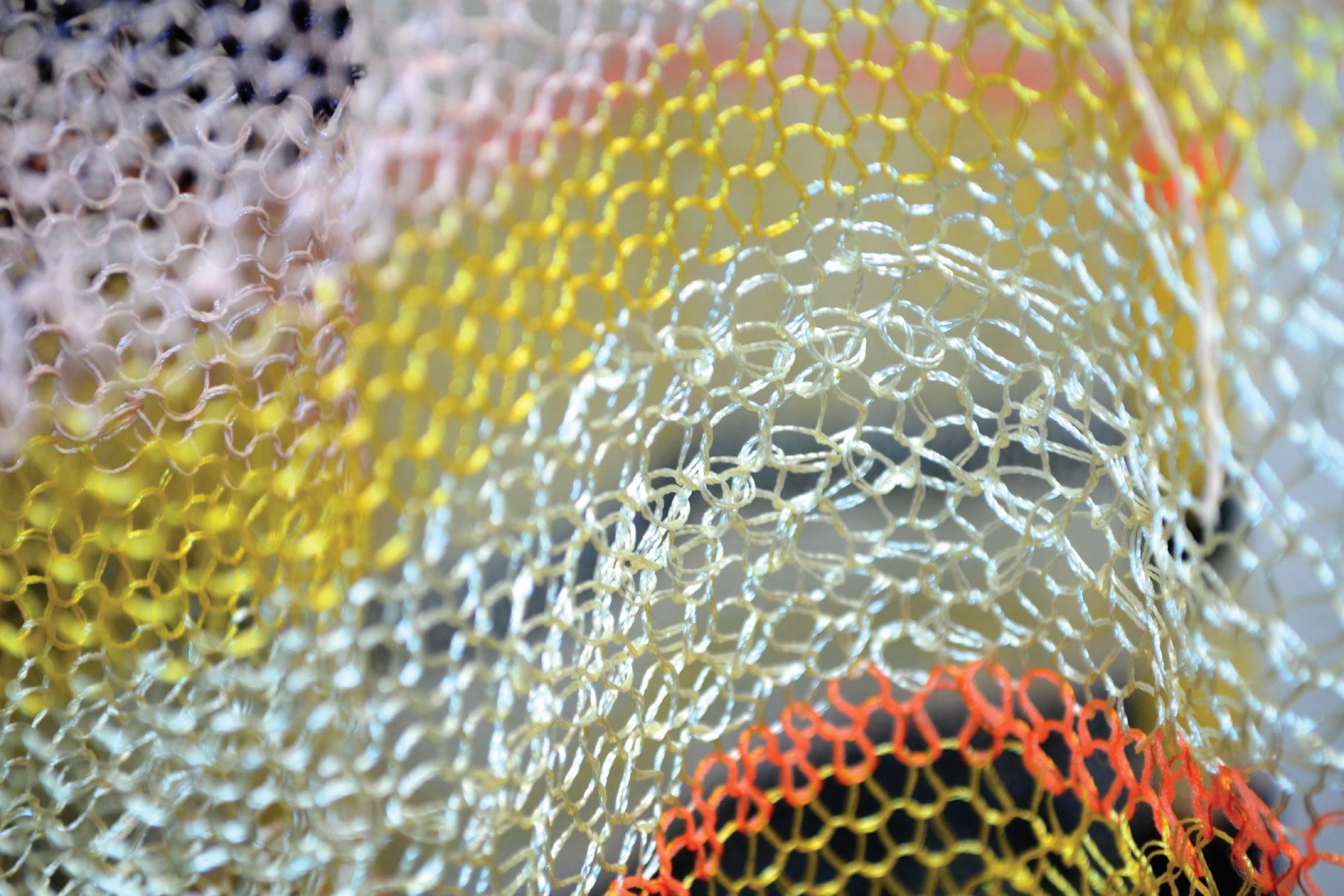

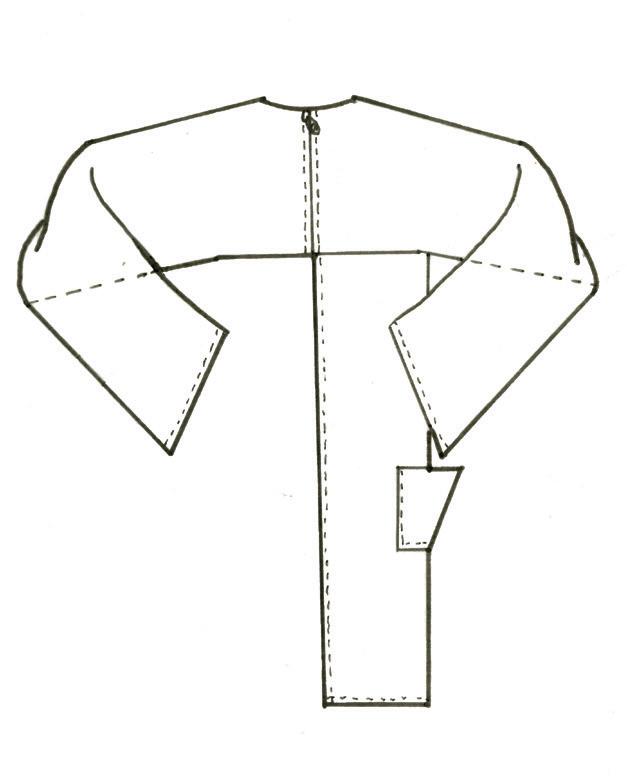

FIGURE 1

Knitted jacket with latex coating 2015

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks to:

my graduate textiles classmates Denise Maroney, Jungil Hong, Dharun Rao, Hye Seong Yun and Emily Winter for their friendship, critique and company,

Adam Smith for inspiring me to be myself as an artist, Anais Missakian, Jesse Asjes and Lorraine Howes for their advice and guidance through the thesis process,

Anne West and Kathleen Biddick for their direction in writing, Rosie Emlein, Angel Dunning, Polly Spenner and Priscilla Carrion for their continued technical support, the textiles faculty at the Rhode Island School of design, in particular MaryAnne Friel and Harel Kedem for sharing their knowledge,

Anna Bay for her laughter and friendship.

Abstract

Dedication

Acknowledgements

List of Figures

Introduction

A Cultural Connection

A Brief History of the Coca Leaf

The Aymara Cloth as Language Form

Landscape as Identity Process

Collage, painting, and color

Materials Textiles

List of Figures

FIGURE 1

Knitted jacket with latex coating. p.12

FIGURE 8

Llacota (man’s mantle)

Department of Potosi

18th Century Alpaca p.32

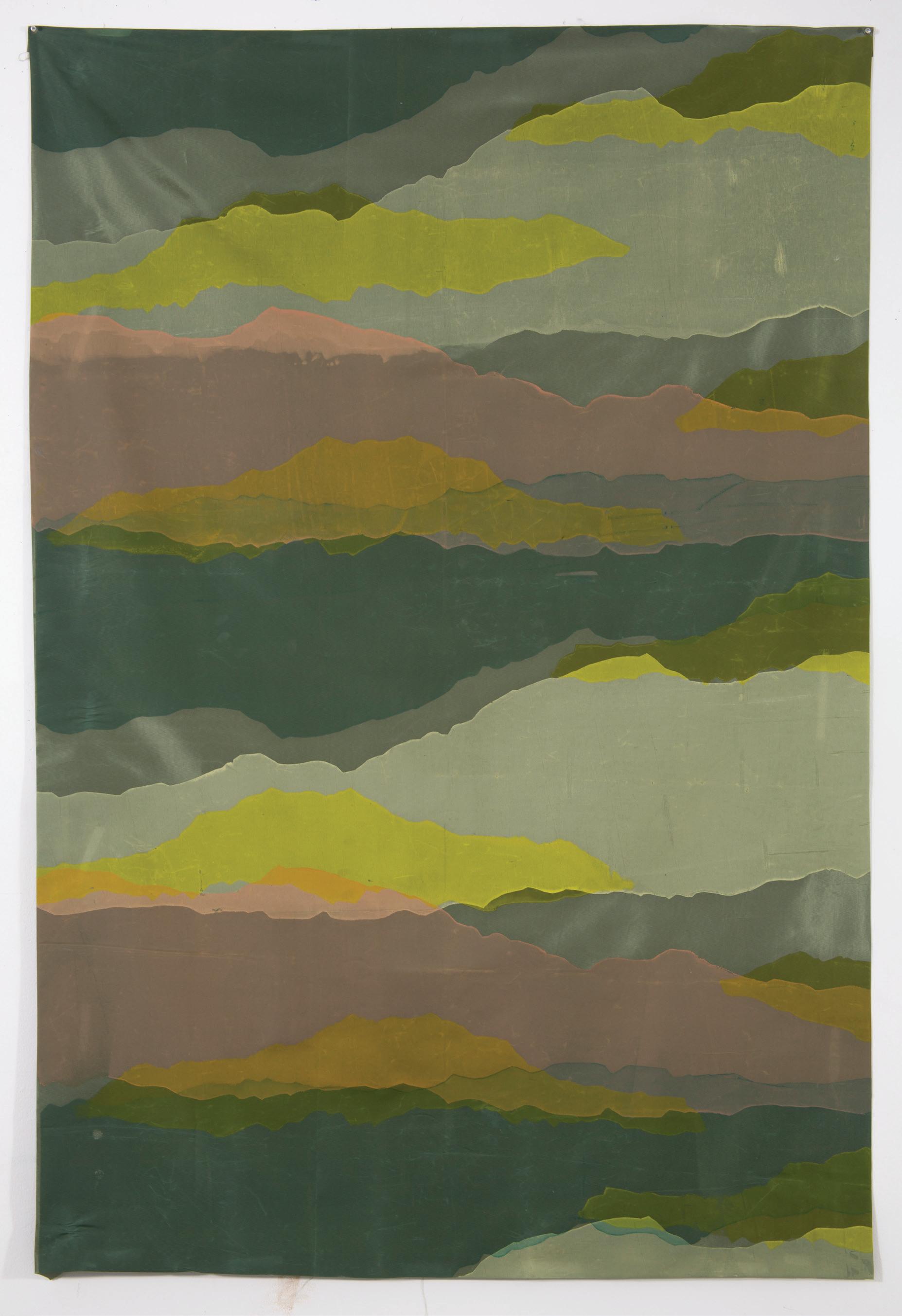

FIGURE 15 MNTNS 2014 Screenprint Pigment on cotton 3ft X 8ft p.48

FIGURE 2 A weaving from Coroma, Bolivia exposing bi-chrome weft yarns. p.21

FIGURE 9 16th-century drawing Guaman Poma de Ayala of an Aymara woman. p.34

FIGURE 16 She Is Digital Collage 2014 p.50

FIGURE 3

An early knitting lesson at Millma. p.23

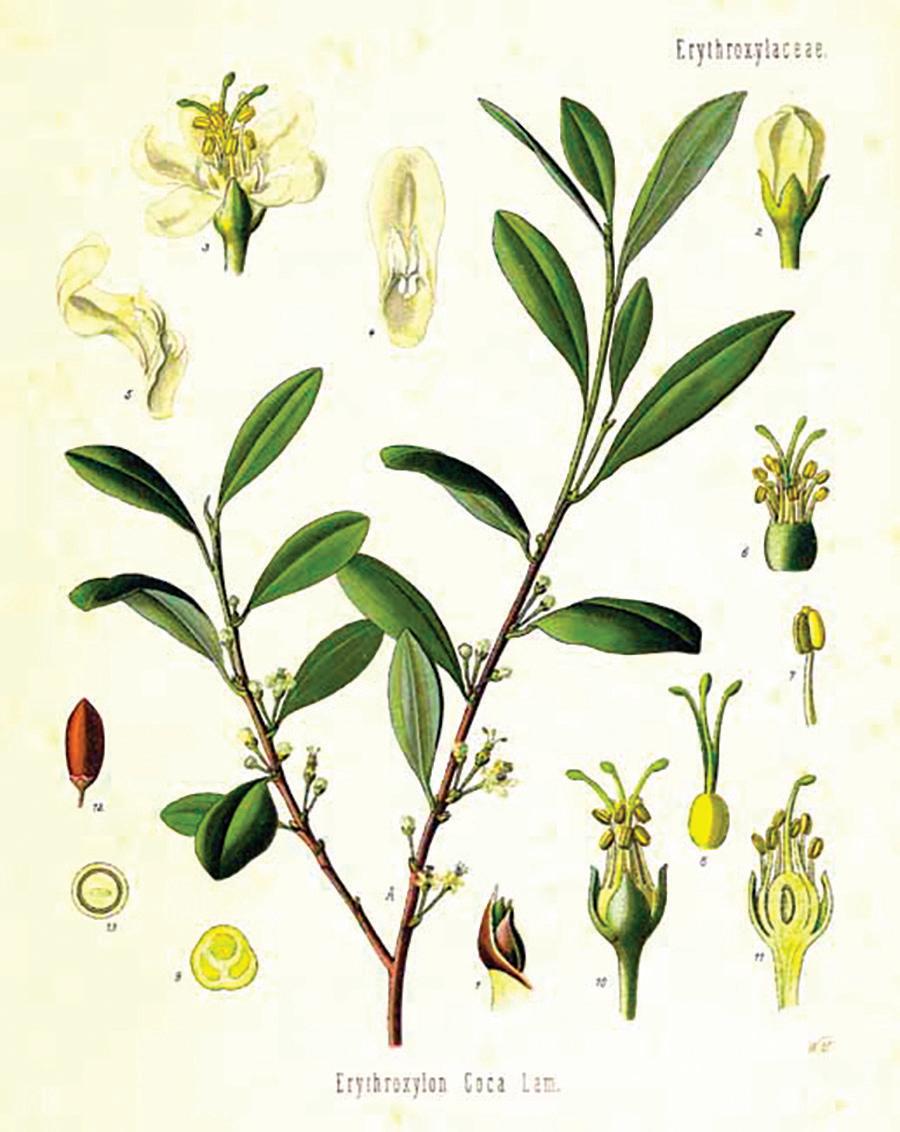

FIGURE 4

Scientific drawing of the coca plant (Erythroxylon coca). p.27

FIGURE 10

17th Century drawing G. Marcgrav p.35

FIGURE 17 Untitled Digital Collage 2015 p.56

FIGURE 11

Early 20th century photograph of a Bolivian Cholita. p.36

FIGURE 18

Untitled II Digital Collage 2015 p.57

FIGURE 5

Portrait Cup Tiwanaku style, A.D 400-1000 Stone p.27

FIGURE 12 From the Harris Tweed Collection 1987-88 From “Vivienne Westwood” p.40

FIGURE 19 Miyuni Digital Collage 2015 p.59

FIGURE 6

Tapestry Tunic Early Tiwanaku Style

AD 200-400 Woven Camelid Fiber p.30

FIGURE 13

Traditional Victorian English dress. p.41

FIGURE 20

Back and Forth Digital Collage 2014 p.60

FIGURE 7

Ccahua (tunic)

Department of Potosi

Probably early Colonial period Alpaca p.31

FIGURE 14

Chance 2014 Screenprint Pigment on Cotton 3ft X 9ft p.45

FIGURE 21 Through La Paz Collage 2014 p.62

FIGURE 22 Hybridity Goache on Paper 2015 p.65

FIGURE 29 Color Study of La Paz Goache on Paper 2014 p.74

FIGURE 36 Industrial Stoll Machine p.86

FIGURE 23 Pin with Mythical Bird (detail) Tiwanaku style A.D. 400-1000 Bolivia - Cast gold p.66

FIGURE 30 Color Study Goache on Paper 2014 p.76

FIGURE 37 My brother Manual knitting machine p.87

FIGURE 24 Being Goache on Paper 2015 p.67

FIGURE 31 Yarn Sorting Facility Mitchell in Arequipa, Peru 2014 p.78

FIGURE 38 Pointelle Sample Alpaca, Rayon, Polyester, Metallic, Rayon, Elastic p.88

FIGURE 25 Divine Intervention Goache on Paper 2015 p.69

FIGURE 32 Yarn Selection and Variation in the Mitchell Showroom 2014 p.79

FIGURE 39 Pointelle sample Wool, elastic p.90

FIGURE 26 Where? Goache on Paper 2014 p.70

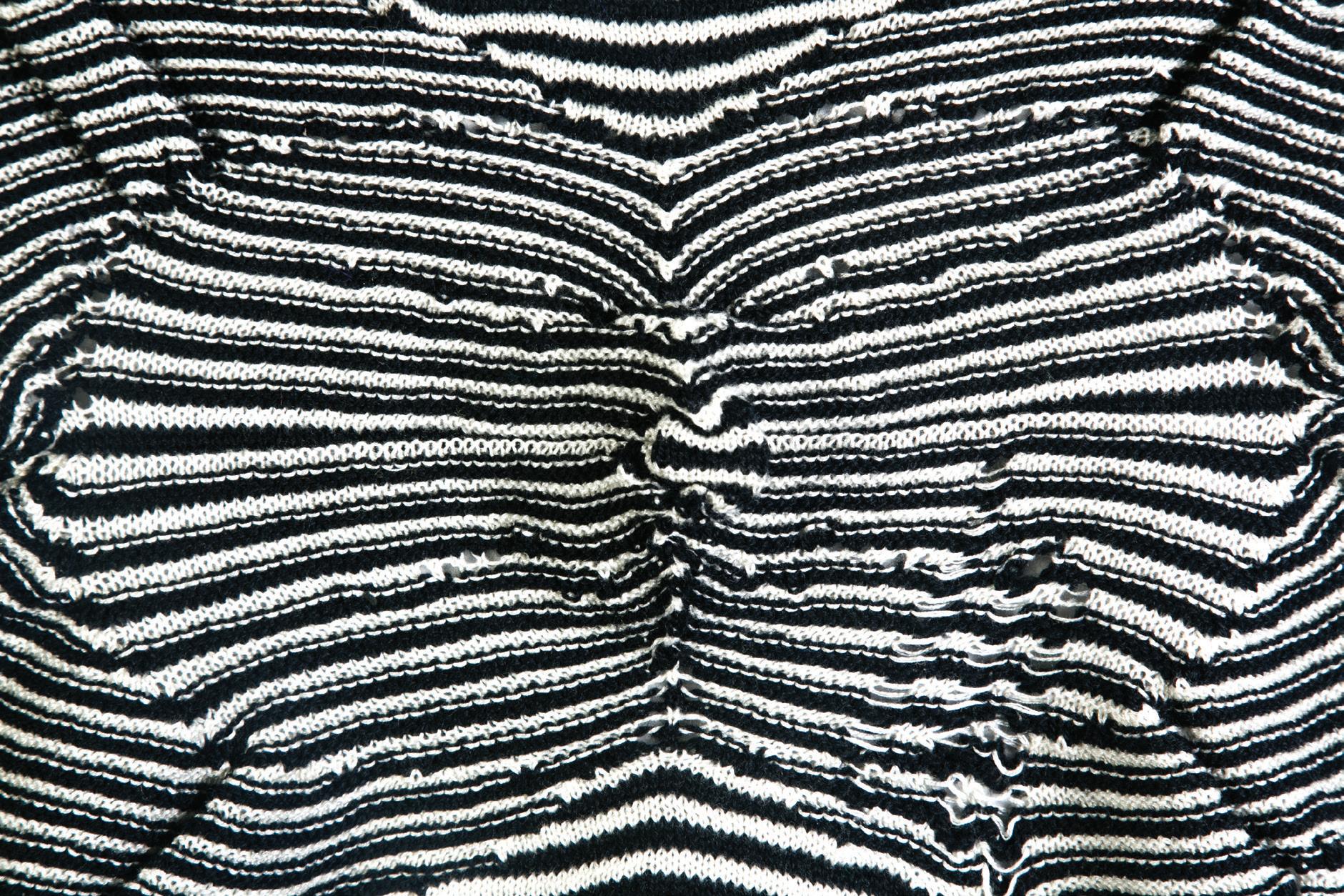

FIGURE 33 Knitted Stripes of Polyester and Cotton Yarn on the Brother 970 p.80

FIGURE 40 Pointelle Sample Cotton, wool p.91

FIGURE 43

Industrial Stoll Machine p.96 For images of the final thesis collection, please see p. 98.

FIGURE 27 Untitled III Goache on Paper 2014 p.72

FIGURE 34 Knitted Stripes of Polyester and Cotton Yarn on the Brother 970 p.81

FIGURE 41 Knitting loops “frozen” in time coated with latex p.92

FIGURE 28 La Paz at Night p.73

FIGURE 35 Jacquard knit sample (felted) Alpaca wool, polyester p.85

FIGURE 42 A knitted, striped fabric with latex coating creating a new plaid pattern p.95

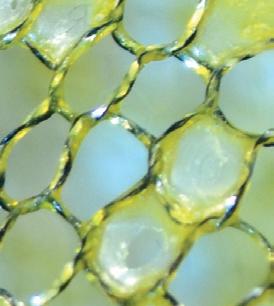

Introduction

Textiles are aesthetic works that hold meaning beyond the surface. A deeper look into the Andean weaving from Coroma, Bolivia in Figure 2 reveals a semiotic construction of cloth. The small incision in the center of the cloth exposes the weft yarns, purposefully chosen in blue and white, representative of the Aymara beleifs in the dualities present in our lives. The calculatied choice of the hidden weft yarns suggests that this cloth was worn by a shaman (Yatiri).

In the Andes it is the textiles that the Yatiris wear and the semiotic codes that the textiles contain that give power to the Yatiri. This is especially true of the left spun yarns in certain tunics.

Like the push and pull of the weft yarn in this weaving, my life exists in a threshold. It is neither black, nor white, but both at the same time.

I was born and raised in La Paz, Bolivia to

American parents. My history with Bolivia is a painful one. I sit on the verge of contemporary Bolivian history and my own making of it. I am a fringe of Bolivian culture - an individual raised by a country with a deep connection to tradition and a sharp collision of indigenous practice with a history of colonial domination. I reference historical textiles by way of my personal encounters with them. I re-dream the weavings of Aymara and Tiwanaku, two Bolivian indigenous cultures, to express a deep lived experience. Cloth embedded with meaning and history, and the clothes I make with them, embody a hybrid personal identity.

From afar, my experience in Bolivia seems all too absurd to believe, too strange to understand. Through the lens of Magical Realism, I can blend the real and the fantastic and bring my Bolivian experience to life. I pair the fantastic elements of

2

A weaving from Coroma, Bolivia exposing bi-chrome weft yarns, indicative of a spiritual belief in dualities present in our lives. Photo provided by Arthur Tracht.

my narrative with the gritty reality I have experienced because fantasy allows us to feel- and this narration is at the womb of my work. The real is not real enough, and fantastic is not fantastic enough- but together they function as a powerful tool for articulating the magical reality that drives my textiles. This collection is an autobiographical perspective of the mystifying tales of my life in La Paz, Bolivia. The textiles pay homage to a unique culture with ancient roots, and to a personal history while offering a frame on my identity.

My complicated relationship with the country that I love stems from politically charged disputes over ownership of my family’s company, born and bred from the sweat of my parents’ hard work. This body of work dreams an archive that can help me understand the entanglements of my history.

FIGURE

“Poets and beggars, musicians and prophets, warriors and scoundrels, all creatures of that unbridled reality, we have had to ask little of imagination, for our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable.”

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez

A Cultural Connection

For as long as I can remember Bolivian textiles have been a part of my life. My parents were collectors, lovers and researchers of the Aymara and Tiwanaku, both pre-Columbian Andean civilizations. Just before I was born, my parents created a small weaving and knitting factory, Millma, in La Paz, producing specialized textiles in the same painstaking way the Aymara and Tiwanaku people did hundreds of years ago. Descendants of the Aymara, the skilled artisans and craftsmen at Millma brought a

unique history with them, which undoubtedly contributed to the success of Millma over the years. It is these people who taught me how to create my own textiles, and shared with me the secrets of knitting that they had developed in the factory over the years. Millma was known for its innovation in knitwear due to the ingenious marriage of textile and design knowledge brought by my parents, and craftsmanship brought by the knitters.

FIGURE 3

An early knitting lesson at Millma.

Thecoca leaf. I’ll never understand how such a non-descript being could change my life so drastically. I always knew that these tiny little leaves had power, but their mightiness was unknown to me until the sequence of events which became my destiny unfolded.

AsI sat in the factory floor that day looking up at my father I couldn’t swallow what he was saying. The room fell silent, and all of the knitters in the factory didn’t know what to say. He didn’t look up from his speech as he said the words. I knew it pained him to say it. We were losing the company. All of the knitters would lose their jobs, my parents would have no income, and the seed that hey had planted, the plant that they had grown and the forest that they had maintained would be ripped out from under everyone’s feet. I looked up to the roof above us, above the 300 workers, above my mother and father, above 200 knitting machines and thousands of pounds of colored yarn. The skylights were open, allowing grave sighs and falling tears to escape the heavy room. The sun was shining bright, sparkling through the afternoon breeze.

Isawa small dark speck emerging from the skylight. At first it looked like a speck of dust, growing in size, gaining speed as it got caught in the cool wind. Then, I saw more, and they became clearer, more dense. They began to take shape, and then I realized what they were. The small green leaves started to fall from the roof. Round with smooth edges, they fell, first one by one, floating whimsically down around the factory floor, onto peoples heads, into their hands.

Ilookeddown into my lap, thinking about how the next years of my life were going to be. What were we going to do? Where would my parents live? What would happen to all of the workers that had taught me my knitting skills?

AsI wondered about my life, a small round coca leaf fell onto my leg. It was upside down, with small prickly edges like I had never seen before. I picked up the leaf and pressed it firmly in my hand. The power of this tiny, unremarkable leaf had set off a chain of events that led to my family losing our business to the hands of the government.

This leaf, I thought. How do you hold so much power? Deep down I had always known it. There was no denying the effects of this tiny little leaf.

A Brief History of the Coca Leaf as told by Dakota Tracht

Bolivia has a storied relationship with the coca leaf. Native Bolivian people have chewed the leaf for hundreds of years, due to its ability to calm the effects of the dizzying altitude of the Andes Mountains, to keep warm, to gain energy, and as a tradition deeply connected to shamanistic and ritual culture. It has been used as a medicinal plant as well, in teas and potions due to its healing properties and its inherent spiritual power.

A sacred plant, the Tiwanaku priests chewed the leaf during ceremonial rituals as a way to connect with nature and their spiritual deitys. Ancient Bolivian folklore says that before coca was a shrub, it was a beautiful woman. She was discovered to be an adultress, and was subsequently executed, cut in half, and buried. From her body a shrub began to grow and blossom. Only men were allowed to pick the plant, and some say that the leaves were only to be used after copulation in memory of this beautiful woman.

Like so many other indigenous traditions interrupted during the Spanish conquest, the use of coca in ceremonial rituals was banned with the arrival of the Spanish. But the presence of this plant continued to live on in the colonies, and its spiritual power was never lost through the years of religious domination of the Catholic church, which was highly against spiritual and shamanistic rituals.

In 1859, German chemist Albert Neimann isolated cocaine from the coca plant. Later in the 1880’s, this new “wonder drug” captured the attention of the medical community. Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmunt Freud used cocaine himself freely, and broadly promoted its use to his patients to cure depression, lethargy, and to enhance sexual encounters. In 1884, in his book “Uber Coca,” (About Coke) he called this drug a “magical substance.”

From then on, its popularity only grew, eventually being used in the elixir for the soft drink Coca Cola, from which it was later removed when people started noticing that, perhaps, it was much more powerful than originally believed. In 1912, the United States reported 5,000 deaths from the use of cocaine, and in the 1920’s its use was banned. Shortly thereafter, other countries followed suit, and soon enough the coca plant earned a notorious reputation as an evil being, forever linked with the drug cocaine.

The American war on drugs further tarnished the reputation of the coca leaf. In the 1980’s, the United States decided that the cocaine problem was in fact the fault of the coca leaf, and began to fumigate coca crops in the Andean nations. In exchange for allowing the United States to fumigate the crops, textiles coming from the Andean nations were allowed tax free status entering the United states.

This continued until circa 2006, when Evo Morales, the president of Bolivia, legalized the growing of the coca plant against the wishes of the United States Drug Enforcement Agency. Rightfully so, he re-established the sacred status of this plant, stating that this plant is not the cause of the drug problem, but it is a medicinal plant vital to the culture of the people of Bolivia.

And so, Bolivia lost the free trade agreement with the United States, and textile producing companies in Bolivia were now levied with a 17% tax on goods coming into the US. The Millma knitting factory struggled to stay alive- fighting to keep its doors open with the new tax imposed. Eventually, this tax weighed heavily on the company, and Milma, along with many other textile producers, was forced to close.

To save it’s name, the Bolivian government did not allow any companies to close during this time, and instead took Millma away, taking illegal ownership of the company and all assets. So now Millma is just sitting there. An empty factory, collecting dust, thousands of pounds of yarn, hundreds of machines, hundreds of workers at home, and my family fighting to get it back.

FIGURE 4

Scientific drawing of the coca plant (Erythroxylon coca) by Franz Eugen Kohler in 1887. The publication in which the image was found included plants of medicinal interest from several european nations.

FIGURE 5

Portrait Cup Tiwanaku style, A.D 400-1000 Stone

The bulge in one cheek indicates a wad of coca, a medicinal plant still widely used in the Andes.

Millma prided itself on using Brother manual knitting machines (pictured in Figure 3). The decision not to move into new industrial equipment was based on lesser aesthetic and qualitative properties of the fabrics produced on industrial knitting equipment. The manual machines at Millma, used for over 25 years, produce fabrics with beautiful drape, exquisite detail, and a handmade quality that is lost on an automatic machine. In addition, Millma wanted to retain the workers it had, rather than firing skilled laborers in the name of increased profitability and output. Quality, not quantity, was Millma’s goal.

In 2010, when I was working in the factory as a knitter and designer, the government of Bolivia began illegally taking ownership of privately held companies. Millma was taken away from my

family. The president, Evo Morales, was ‘taking back’ what he believed belonged to the Aymara people, who inhabited the country long before the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century. At the time, it seemed unjust, but not out of the ordinary. I accepted the reality that my family would be displaced, and decades of hard word would be left in the dust.

I also realized that I would be pushed into a new world of industrial fabric making, since the manual machines familiar to me from Millma are becoming obsolete, being replaced by automatic Stoll machines. Not only is this

happening in the design schools of North America, such as RISD, but also In Latin American manufacturing facilities. The implications of this have guided much of my decision-making process in this thesis.

Looking back, the story of my family’s factory seems unbelievable, as does most of Latin American history through the years. It is no wonder that Magical Realism emerged as an effective way of storytelling the commonplace absurdities present in Latin American society, politics and culture. Amongst all of the twisted realities I had experienced during my life in Bolivia, this was the most violent of them all.

The Aymara Cloth as Language

The Aymara and Tiwanaku people of Bolivia embed their textiles with twofold meaning. Textiles and art are rich with images of animals with double heads, gods with serpents emerging from their heads, condors with the bodies of other animals, and complex geometries and connections between these symbols. The tapestry weave in Figure 6 found in the pre-Colombian ruins of Tiwanaku depicts the sun god, complete with mystical animals surrounding him, representative of the natural world, symbolic of mountains and rivers and their connection with human beings. Nothing exists in isolation, we are all individual and we are all one at the same time, constantly moving back and forth between the spiritual world and material life.

FIGURE 6

Tapestry Tunic Early Tiwanaku Style AD 200-400 Woven Camelid Fiber

The arrival of the Spanish in the 15th century greatly influenced the Aymara belief system and their connection to cloth. It wasn’t until centuries later that the Aymara were able to dress and identify freely. Many unique weaving techniques were lost during this time, though some Spanish and European weaving techniques were also adopted and blended with local tradition, creating a new hybridity.

FIGURE 7

Ccahua (tunic)

Department of Potosi

Probably early Colonial period

Alpaca

p. 53 Adelson and Tracht

Aesthetically, Bolivian textiles have evolved over time. “Colonial descriptions of Aymara dress usually refer to striped garments with little mention of patterning,” although this is now not the case (Adelson and Tracht, 19).

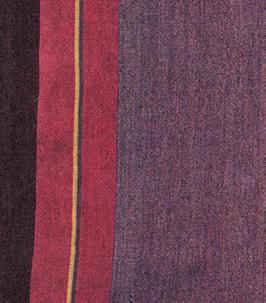

Aymara cloth is typically warp faced- and “stripes are inherent in the structure of warpfaced weaving. Unless a piece is completely patterned or completely plain, there will of necessity be stripes” (Adelson and Tracht, 46). Still, the stripes in these textiles mean so much more than color and landscape- they embody language, where “the number of stripes are symbolic representations of the Aymara’s social and physical world” (Adelson and Tracht, 47).

Celebrated for their ability to dye yarn, the Aymara peoples were experts in the creation of bright and vibrant colors using natural dyes. They pushed the boundaries of what was physically possible with what was at their disposal, and this is evident in their weavings and the color relationships they employ in the stripes.

Figure 8 of a man’s mantle (Llacota) shows this phenomenon. The “Llacota was an essential part of the Aymara man’s outfit, but it has virtually disappeared from the costume of modernday Bolivian men,” due to colonization of the Spanish (Adelson & Tracht, 83). The uneven, subtle color variation is a result of uneven dyeing, which is inevitable in the use of natural dyes on the alpaca fiber. It plays with the eye, drawing the viewer in- creating depth and suggesting light.

Department of Potosi 18th Century Alpaca

Adelson and Tracht p. 83

FIGURE 8

Llacota (man’s mantle)

Form

Dress has always been associated with identity in Bolivia. Symbols embedded in textiles in preColumbian times indicate tribe, social status, and family lineage. Weavings were taken directly from the loom, wrapped around the body and tied in knots. Colla (Aymara) women also closed their garments with metal pins. These textiles were consciously woven to size- each of these four edges contained a finished stitch on the loom.

Figure 9 shows a Colla (Aymara) woman wearing a mantle covering a tunic, which was wrapped around the body and tied in knots or held together with pins. The tunic was generally very loose fitting, and exposed parts of the body. Strict sumptuary laws during the Spanish conquest changed this. The Spanish believed that the indigenous women’s clothes were too revealing and therefore forced them to change their way of dress (Figure 10). These women forcibly adopted a new way of dress heavily influenced by the European fashions of the time (Figure 11).

FIGURE 9

16th-century drawing

Guaman Poma de Ayala of a Colla (Aymara) woman wearing a mantle, urku, and headcloth

FIGURE 10

17th Century drawing

G. Marcgrav

Early 20th century photograph of a Bolivian Cholita, complete with her Jubon, layered skirt, and top hat.

This hybrid form of dress is still seen on the streets of Bolivia to this day. Women now have the freedom to consciously identify with this colonial form of dress, known as the “cholita.” These women wear a large layered skirt rushed at the top; a blouse influenced by Spanish colonial fashion, called a Jubon, and a shawl wrapped around their shoulders. They have also adopted the use of the top hat, which is traditionally made of felted alpaca wool.

Although the Spanish controlled this and every aspect of indigenous life, not all of the tradition of wrapping weavings as a form of dress has been lost. Since then, indigenous women re-adopted their ancient forms of dress, and just as one might find a cholita walking down the street, one also regularly encounters women wearing striped Aymara textiles wrapped around their bodies.

FIGURE 11

My interest in historical garment and textiles is similar to that of Vivienne Westwood, an English- born designer who “carefully studies the structure of historical costume in museum archives such as the Victoria and Albert Museum” (Wilcox, 9). It is a deep understanding of her past, and her fearlessness in its interpretation that make her clothing unique. Vivienne was born in England and is “quintessentially British” (Wilcox, 25). Her working class upbringing was

essential in her understanding of the world- she criticized the bourgeoisie and the royals for their negligence of poverty and struggles of the lower classes in England. Her critique comes through in her work- she is a rebel, assuming control of traditionally British tartans and tweeds, large formal ball gowns and traditional patters and reworking them to make a political statement rich with British identity. Her work encapsulates “a particular Britishness, a fearless unconformity combined with a sense of tradition” (Wilcox, 9). She toys with the threshold of tradition and her personal cultural heritage as a tool for expression and identification. Her respect for

traditional English forms of fabric production and her insistence on working with original manufacturers for her English tweeds and Scottish tartans demonstrate faithfulness to her past and an ingenuousness to learn from those who came before her, much like the creative process at Millma and in my personal work.

Figure 10 of Vivienne Westwood’s Harris Tweed collection of 1987-88 demonstrates traditional English inspiration through the use of the classic corset. She also plays with the classic crinoline, but she injects a modern twist by making it shorter, sleeveless, and out of modern materials.

p. 80

FIGURE 12

From the Harris Tweed Collection 1987-88

From “Vivienne Westwood”

FIGURE 13

Traditional Victorian English dress, showing the classic Victorian English corset and crinoline, which greatly influenced Westwood.

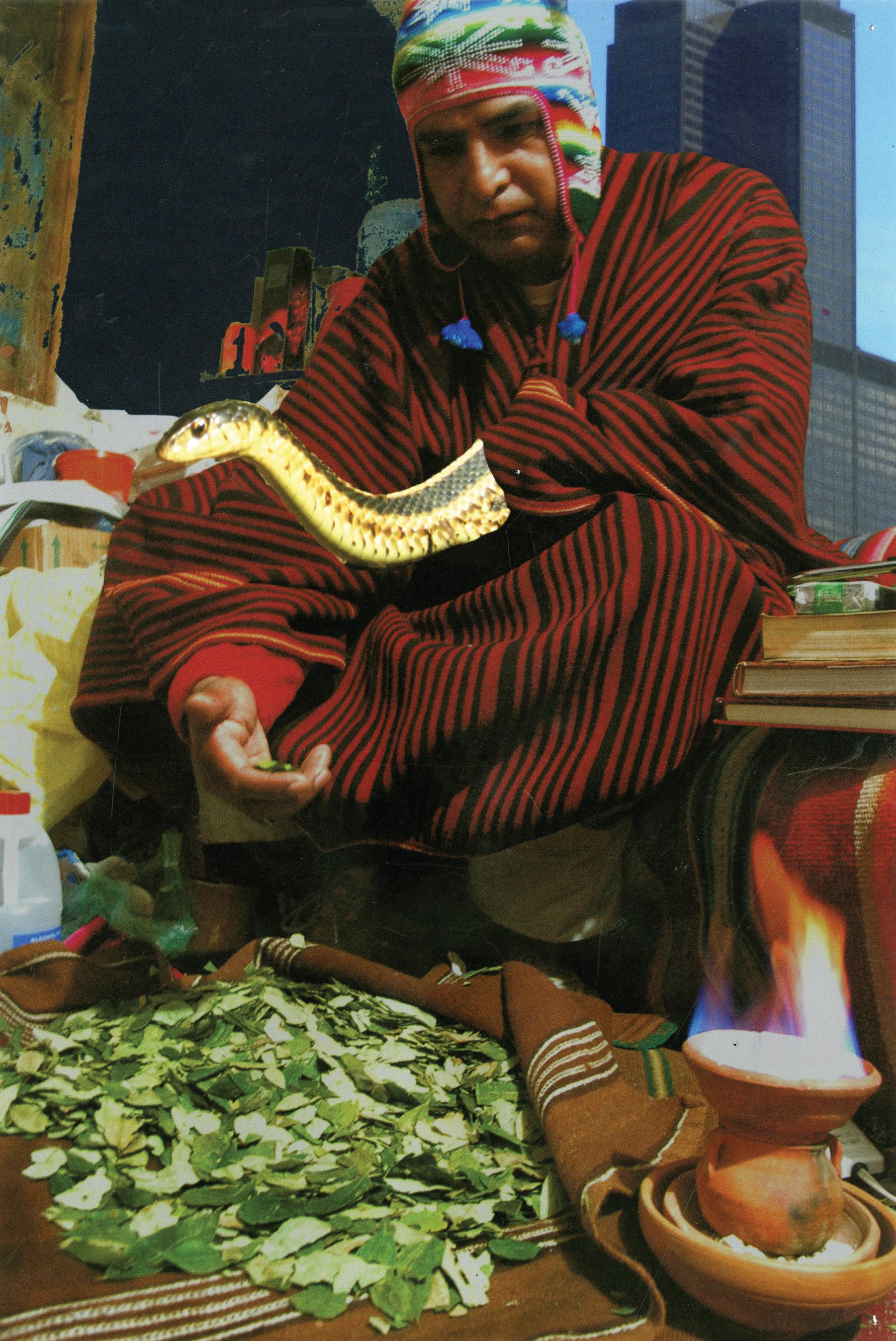

Onceupon a time, I walked up the mountains to visit my Yatiri. He sits on a striped cloth and tells me my future.

TheYatiri reaches into his sack and pulled out a large fistful of leaves. They are fresh- probably picked up that same day and sorted- some for chewing and the rest for fortune telling. I can smell their bittersweet scent wafting through the air, and I can see the ball in his cheek, filled with leaves he probably chews daily. He lifts his fist in the air, and the snakes move their heads out of the way to the side of the cloth.

Letting go slowly, the leaves drift down, sliding through the air and hitting the cloth in front of her. Some of them were turned up to face her, while others hid their faces- buried in the cloth. She looked at both heads of the snake and at that moment she knew the shaman was right. The eyes of the snake were half black and half white. He had been to the other world and back.

WillI like it? I asked him about my move to the United States. Yes. He said. But you will come back.

Why? I asked.

Because, he said, you have unfinished business.

FIGURE 14

Chance 2014

Screenprint

Pigment on Cotton 3ft X 9ft

Living in Bolivia, I encountered spiritual beings on a daily basis. Every action was met with a symbolic repercussion, and every being had his other half, part of a spiritual world.

A reading with a Yatiri was once a yearly ritual. I have always had an intimate connection with both the Bolivian and American cultures that I come from. My lived experience in Bolivia, with these woven stripes, with the craftsmen in the factory, take on a unique meaning inside me- I am not complete without them, and therefore pay homage to the Bolivian culture that raised me through the creation of cloth.

My work far from Bolivia has taken on a new meaning. I am interested in re-dreaming Aymara textiles in a hybrid setting with hybrid techniques that honor traditional cloth. An adopted daughter of the Aymara culture, I stand on a threshold between tradition and personal understanding of an established historical language. My interpretation represents neither tradition nor my lived experience, but both simultaneously. I want to see Bolivian history in my contemporary practice while expressing my own vision.

Landscape as Identity

Bolivia is a cultural hybrid- a people once with a strong identity that was interrupted by colonial politics and European culture. Still, the mystical elements of the Aymara and Tiwanaku have survived the Spanish conquest, melding with Catholic religion and forming a unique belief system where we interact with supernatural beings on a daily basis. It is through this lens of magical realism that I can begin to explain my experiences.

“The city in the bowl,” as I refer to La Paz is a magical reality. Surrounded by mountains, surviving at 30,000ft is a miracle in itself. Often visitors are unable to stay in the city for long because their lungs are unable to cope with the thin air. Descending upon the city via airplane, one can see the flat plateau (Altiplano) dip into a gigantic valley of winding roads and mountainsides, smack up against the Cordillera de los Andes (the Andes mountain range). Living amongst the mountains in bustling city made me feel protected, as if my ancestors were watching over me as well.

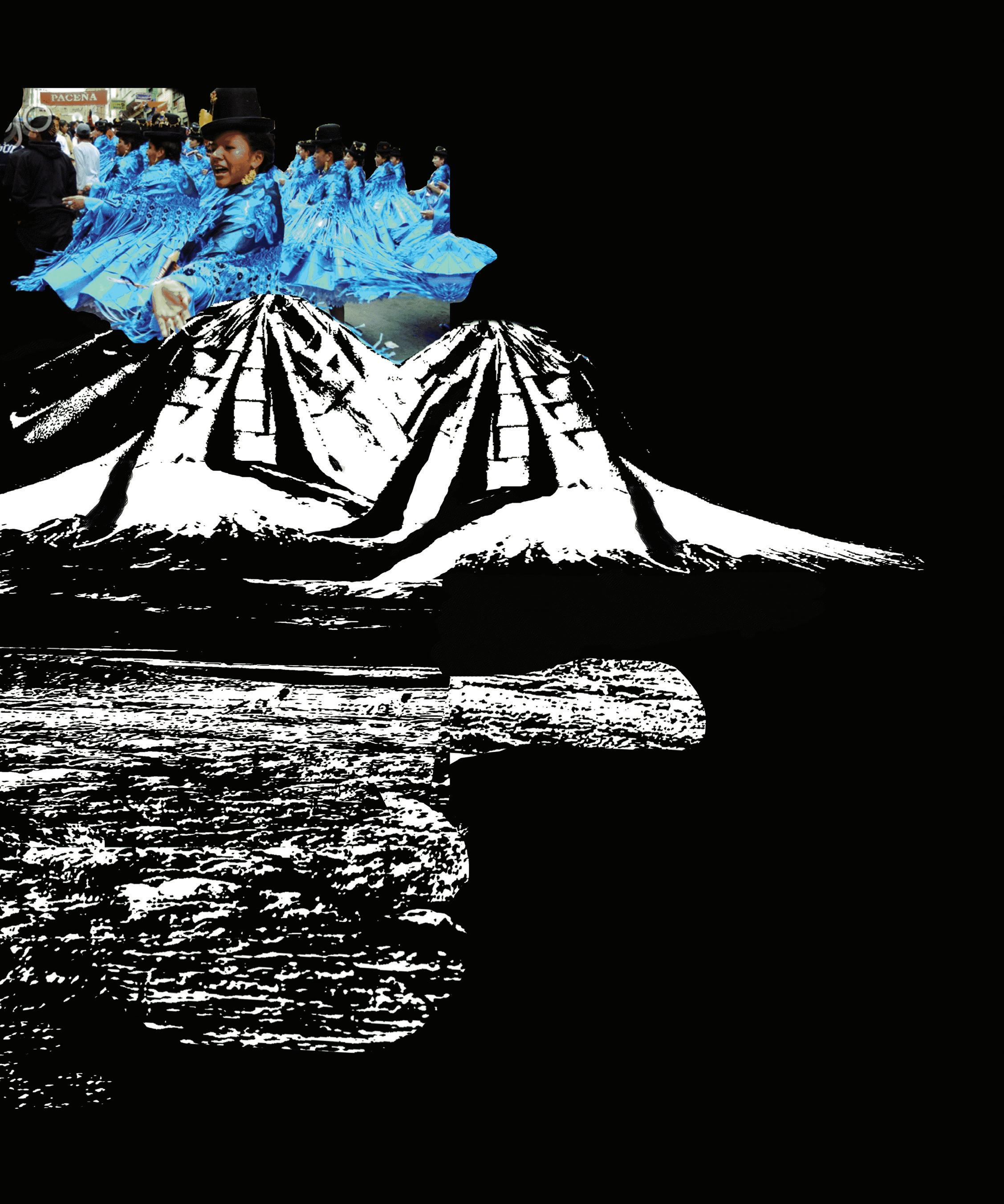

FIGURE 16

She Is Digital Collage

Shehustled down the winding streets, ducking between mountains, slithering on the old cobblestone. The laid stones had been there as long as she could remember- and had probably been laid in colonial times, hundreds of year’s prior. They were slippery with memories of horse-drawn carriages, slaves carrying cargo on their backs, the blood of animals from the butchers, llama wool and thousands of people trudging along these roads in search of cures for their ailments, love potions, llama fetuses to bury under their houses, spells to cast on their enemies, and Yatiris to help them with future endeavors.

Themountains were steep, so she turned into a snake to be able to traverse them with ease. She could duck in and out of corners this way, hurrying to her destination. The mini buses funneled down the windy roads deeper into the valley, jamming up the further they got. As a snake, she avoided this.

Whenshe arrived home to the yellow house, she turned back into a human. Her mother hated when she became a snake, for fear that she would be killed by non-believers. She walked upstairs and onto the balcony overlooking the city. The mountains surrounded her like a mothers arms protecting a baby. She didn’t know it at the time, but his was the last time she would stand on this balcony- fate was taking her away from this place forever.

PROCESS

COLLAGE, PAINTING, AND COLOR

I create collage to unfold a personal narrative and to experiment with an expanded field of color. Like Borges, I believe that history and reality is best told through fiction, because it allows us to dream. Through collage I blend the magical and the real in representational form. I use cultural symbolism and images embedded with personal experience to represent these lived experiences. The collage in Figure 16 represents the Aymara belief that once ancestors pass away, they live as mountains, overseeing and protecting the

people below. The cholita’s skirt blends into the mountain, which runs down the landscape to the front of the house. This house where I lived during the last years we spent in Bolivia. The balcony in the front was where I stood watching those mountains over the years.

The digital collage in Figure 17 at first appears to be an ordinary photograph; a woman walking down the street holding her child in a sleepy market. But the large condor, the skyscrapers of Chicago behind the market in Bolivia and the blue door suggest two parallel worlds that coexist in the same place. It is the presence of the magical embedded in the grittiness of the real that interests me.

Previous Page

FIGURE 17

Untitled Digital Collage 2015

Previous Page FIGURE 18

Untitled II Digital Collage 2015

FIGURE 19

Miyuni Digital Collage 2015

FIGURE 20

Back and Forth

Digital Collage

21

Through La Paz Digital Collage 2014

FIGURE

22

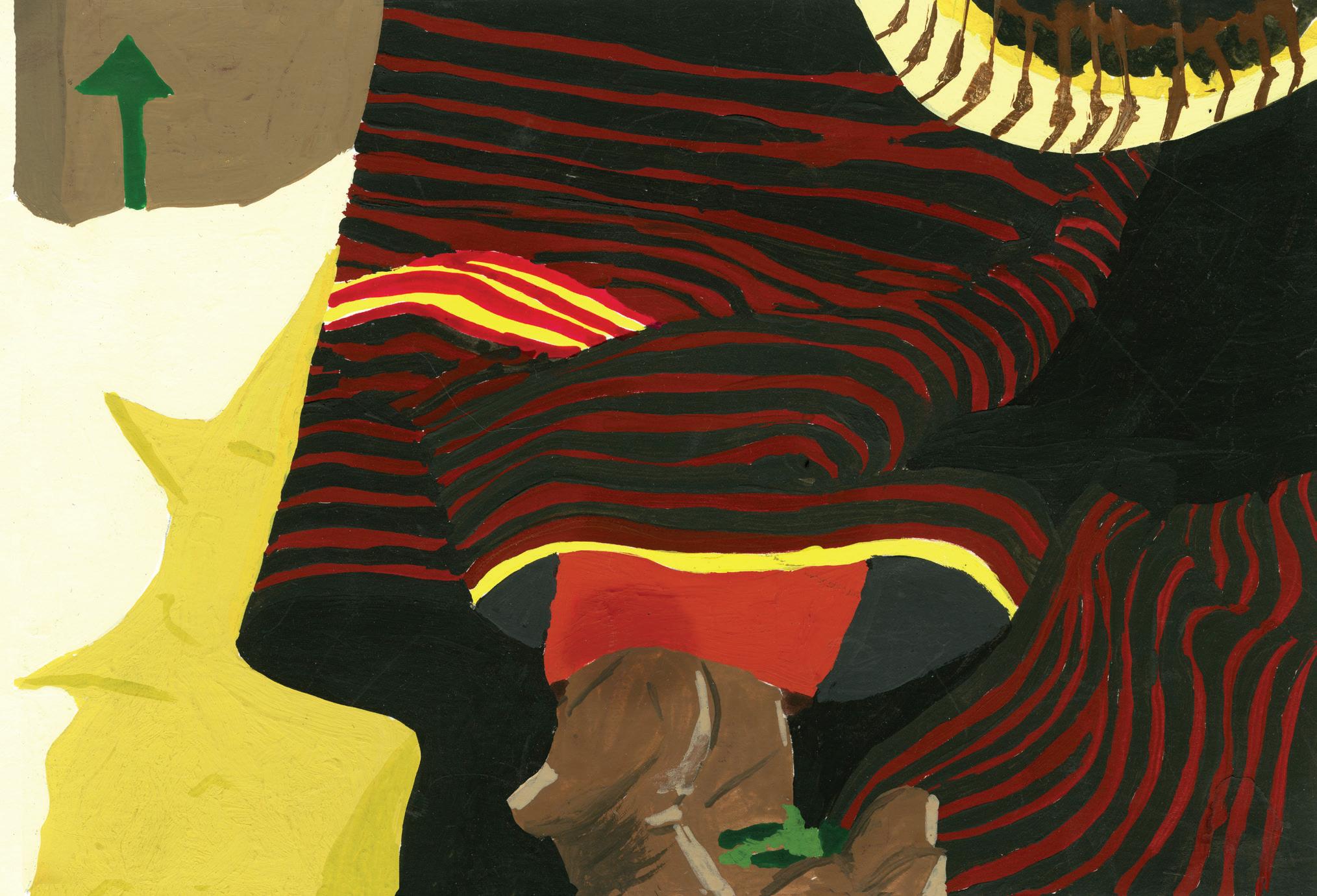

Hybridity

Gouache on Paper 2015

I took the collages further by painting specific areas of them. This allowed me to express my narrative through specificity of color and to point to areas of the collages of particular curiosity to me. Zooming in brings focus to the juxtaposition between the real and fantastical elements of my work. I focused on everyday objects within these complex collages, making them fantastical and drawing attention to them in new ways.

The detailed imagery and frame in Figure 22 draws attention to the bottle, the statue of Jesus, and the hand, and elevates their status and attention within the larger scope of the collage in Figure 20. I am also interested in the juxtaposition of symbols in this piece- there is the statue of Jesus, the traditional Aymara cloth,

the hint of mysticism with the yatiri’s hand, and the bottle of alcohol. The references to mysticism and otherworldly spirits are not traditionally accepted in the Catholic church, yet the Yatiri has the statue of Jesus with him during his processions. The irony of these symbols amuse me, though the presence of hybrid imagery and objects such as these is commonplace in Bolivia.

The use of mystical beings borrowed from the Tiwanaku iconography also appears within my collages and paintings.

The painting in Figure 24, drawn from the collage in Figure 17, brings this fantastically enormous bird to a new world- he sits in a place between the witch market in Bolivia and the urban center of Chicago. His enormous size makes him fantastical, but the architecture places the condor in a physical place.

FIGURE

FIGURE 23

Pin with Mythical Bird (detail) Tiwanaku style A.D. 400-1000

Painting from my collages allowed me to arrive at an expressive color palette. Using gouache was helpful because it was easy for me to mix colors and achieve the flat color I was looking for.

I wanted to work with colors inspired by the landscape of La Paz at night and the natural light in the city during the day. I also used color to express the fantastical aspect of my experience. Some of the colors I chose are from memory, while others were studied in depth through gouache pixelated paintings of the city and the natural landscape.

Bolivia - Cast gold p. 59 “Tiwanaku: Ancestors of the Inca”

FIGURE 24

Being Gouache on Paper 2015

Divine Intervention Goache on Paper 2015

FIGURE 25

Where?

Goache on Paper 2015

FIGURE 26

FIGURE 27

Untitled III

Goache on Paper

FIGURE 28

La Paz, Bolivia at Night

Previous Page

FIGURE 29

Color Study - La Paz

Goache on Paper 2014

FIGURE 30

Color Study

Goache on Paper 2014

Materials

My personal interpretation of Bolivian culture and its landscape is further expressed through material choice. I chose alpaca and cotton yarn, both traditionally used in Bolivian textiles, and juxtapose these with modern, synthetic materials such as polyester and rayon. On a trip to Arequipa, Peru last year I was able to visit the Mitchell Alpaca spinning factory, the same company that supplied yarn to Millma for almost 30 years. This experience gave me a newfound appreciation for Alpaca. It was important for me to use this yarn in my collection.

FIGURE 31

Yarn Sorting Facility Mitchell in Arequipa, Peru 2014

FIGURE 32

Yarn Selection and Variation in the Mitchell Showroom 2014

My goal was to enhance the material quality of the Alpaca through felting, combing and combining it with shinier materials such as polyester. The mixture of these two materials, allow the aesthetic qualities of each to shine through.

In addition to Alpaca, I used a fair amount of wool. Sheeps wool is readily available here in the United States. It also knits very nicely on the industrial knitting machine, felts easily, and has a wide variety of colors and qualities.

It is my goal to use natural materials as much as possible in my design process, but I allowed myself to use synthetics in this thesis project because the combination of newer synthetic

yarns and filaments allows for more exploration in stitch size, density and structure. I used a clear monofilament for one of my pieces on the industrial knitting machine because it retains a unique volume when knitted in a basic jersey structure, and contrasts nicely with wool and alpaca.

Still, it is important to me to make a positive contribution as a designer, and therefore will refrain from using synthetic yarns, specifically plastic monofilament, in future designs.

FIGURE 33 + 34

Knitted Stripes of Polyester and Cotton Yarn on the Brother 970

Textile Making Techniques

Knitwear is my primary vehicle for expression. I digitally printed a few of my paintings to incorporate a specificity of color, but I intentionally made the majority of my pieces knitted.

I knit polyester and alpaca into a jacquard knit similar to those I worked on while at Millma, but this time I felted the alpaca in order to achieve new results (Figure 35). Felting the alpaca wool makes the fabric a more even, matted surface, while the polyester stays shiny and does not retract in size. Felting enhances the structure of a textile, especially when wool is combined with synthetic yarns. This process provides information- information on how materials act, information on how a textile is constructed, and information on how you want to proceed in further iterations of the piece.

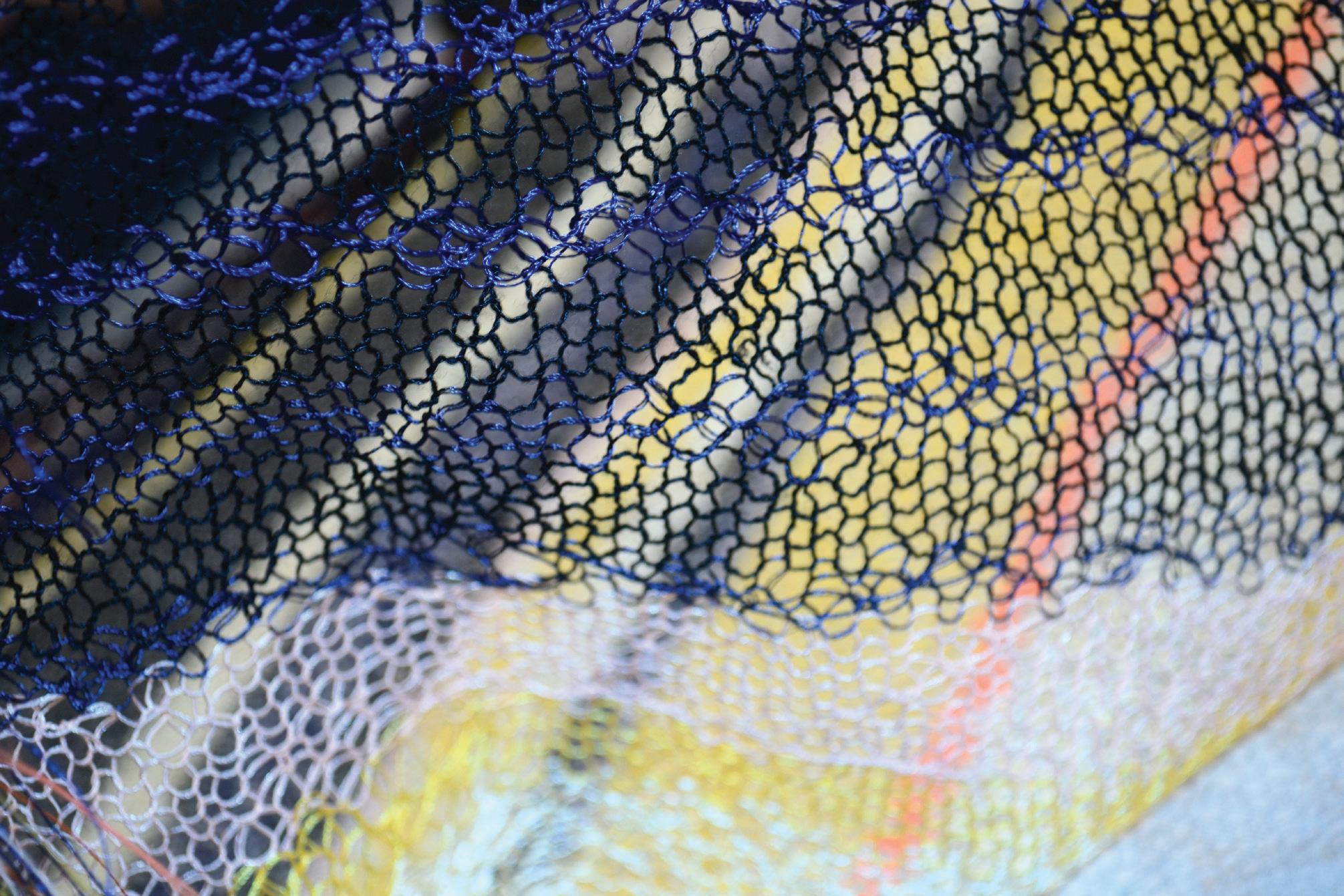

My decision to knit stripes in a similarly laborious, painstaking way that the Aymara wove striped cloths allows me to play a parallel role through a practice unique to my own exploration. I chose to knit these with a very thin yarn on a larger-gauge knitting machine, because it forms loose, open loops, and the ability to see through these loops to the other side of the fabric when it is draped creates unique space and depth.

FIGURE 35

Jacquard knit sample (felted) Alpaca wool, polyester

While many structures can be knit on a manual-knitting machine, they require a large investment of time. The industrial machine allows for quick exploration of ideas and concepts, and for a wider range of imagination to take place during programming.

At RISD I have fabricated much of my work on the industrial knitting machine known as the Stoll Machine. At the outset it was important for me to ask the following question: What can this machine do that a manual knitting machine cannot? I did come to appreciate how the Stoll can knit complex structures with multiple stitch densities in each row. It was this complex

technical capacity that I chose to explore in my MFA collection. It wasn’t enough for me that the Stoll can knit faster, because I am not interested in fast fashion. But the fact that the Stoll can knit complex structures that are near impossible to achieve on a manual machine is what makes it special.

Nevertheless, I am ambivalent about the Stoll machine as the future of knitting technology. It produces a certain quality of fabric that can never match the embedded craftsmanship of a manual knitting machine. Stoll fabrics look and feel ordinary. They are easily reproducible and are without the signature of craftsmanship typical of the work produced by manual machines.

As my time in the RISD program winds down, I struggle with the idea that the Stoll is the future of knitting. In fact, the types of machines in use at Millma are no longer even produced

FIGURE 36

Industrial Stoll Machine

and this slow, crafted knitting is disappearing from the industry.

The labor implications of industrial machines are also troubling to me. The Stoll renders redundant skilled craftspeople. The Stoll spells the end of skilled labor in the industry.

My recent trip to Peru was indicative of the direction the industry is heading. I saw rooms filled industrial knitting machines managed by one or two technicians. The few rooms remaining with manual machines were tended by tens or hundreds of skilled workers.

So the question becomes how can I maintain the use of manual knitting machines in an increasingly industrialized world? Do people notice and care about the quality of the fabrics they wear? Or does brand trump quality? So the challenge becomes: how can I achieve the same or similar level of craftsmanship and beauty on the Stoll as once achievable on a manual machine?

I therefore chose to knit only very complex fabrics on the Stoll machine to exemplify the technological differences between these two forms of knitting. I needed to make fabrics on the Stoll that are not reproducible, or very difficult to reproduce, on the manual machines to justify its use.

FIGURE 37

My manual brother Machine

FIGURE 38

Pointelle Sample Alpaca, Rayon, Polyester, Metallic Rayon, Elastic

I thought that knitting on the Stoll would further enhance the juxtaposition of materials I was looking for. How can I “build” fabrics in new ways? How can the stitches bring the cloth off of a surface, and turn into something dynamic? These were the questions I was asking myself as I approached this machine.

I am interested in knits that are dynamic in nature, that take on 3D form when knitted with complex structures. Many times the industrial machines are used for high- performance fabrics that are used for active wear such as shoes or industrial purposes. This machine can handle certain synthetic yarn that is very difficult to knit with on a manual machine or by hand.

FIGURE 39

Pointelle Sample Wool, elastic

For this project, I was interested in “growing” mountains on the industrial machine. The memory of living amongst the mountains and their connection to Bolivian identity was the driving force. Through the use of the knitted pointelle technique and racking I was able to pile stitches up on each other; thereby creating knits that resembled landscape and mountains (Figure 40).

I see this technique having a place in more active wear applications, such as technical fabrics or textiles used in industrial design applications, but it created interesting shapes and textures when draped on the body.

Color, material and knitted structure are adequate avenues for the expression of Magical Realism in textiles. However, I found that I needed to push some of the fabrics further in order to fully express my ideas.

I chose to apply latex to the traditionally knit jersey striped fabric in order to transform its material quality and the way it drapes on the body into something unexpected. The manual application of the latex to the fabric is delicateand needs to be done with care to ensure that I achieve the correct amount of latex for the desired effect. Minimal amount of latex is ideal because it just coats the surface of the fabric, adding a liquid- like effect that just faintly changes the surface of the fabric. The clear nature of the latex once it dries is enhanced by its sheenallowing light to bounce off of each knitted loop individually, like the sun dancing across a lake (Figure 41).

FIGURE 40

Pointelle Sample Cotton, wool

Knitting loops “frozen” in time coated with latex

I stretch the fabric with pins over a table with fabric covered in paper, ensuring the knitted fabric is square and that the stripes are still perpendicular to the table. This tension is a delicate balance between the flexibility of the loops in the length and width of the fabric. I then pour the latex- mixed with pigment for color. I pull the wet knit towards myself, and the fabric slowly pops off of the paper it is on. The physicality of this process is in slow motion- in sharp contrast with the intense movement of knitting on a manual machine- which requires a lot of energy while pushing the carriage back and forth over the needles.

FIGURE 41

Once the latex dries, each knitted loop is frozen in its destined place. My physical movements determine the position in which each loop will ultimately rest during knitting and the application of latex. The subversion of a draped piece of knitted fabric and the traditional stripes within brings this fabric to a new place. A knitted fabric tends to drape freely- flowing around the body and adhering to its shape- but this new creation is nothing but a nod to knitwear and Aymara textiles, existing in its own realm and straddling two complementary worlds (Figure 42).

A knitted, striped fabric with latex coating creating a new plaid pattern

FIGURE 42

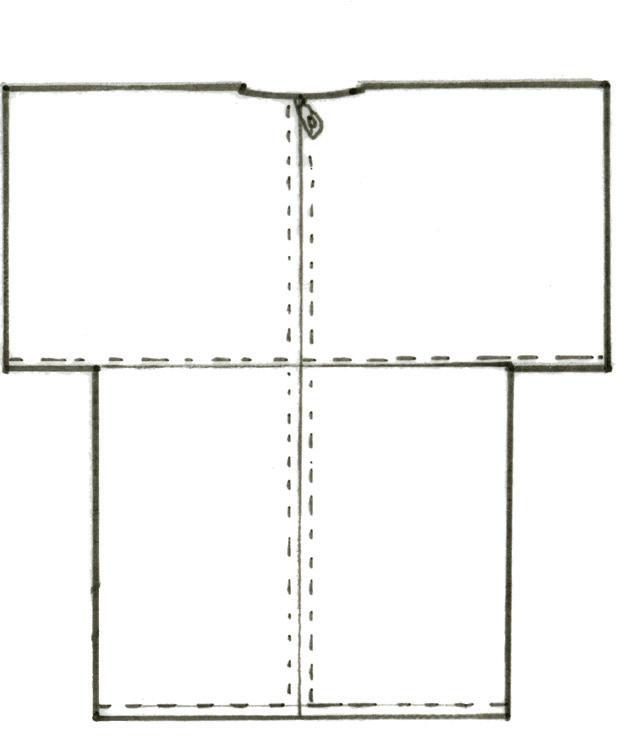

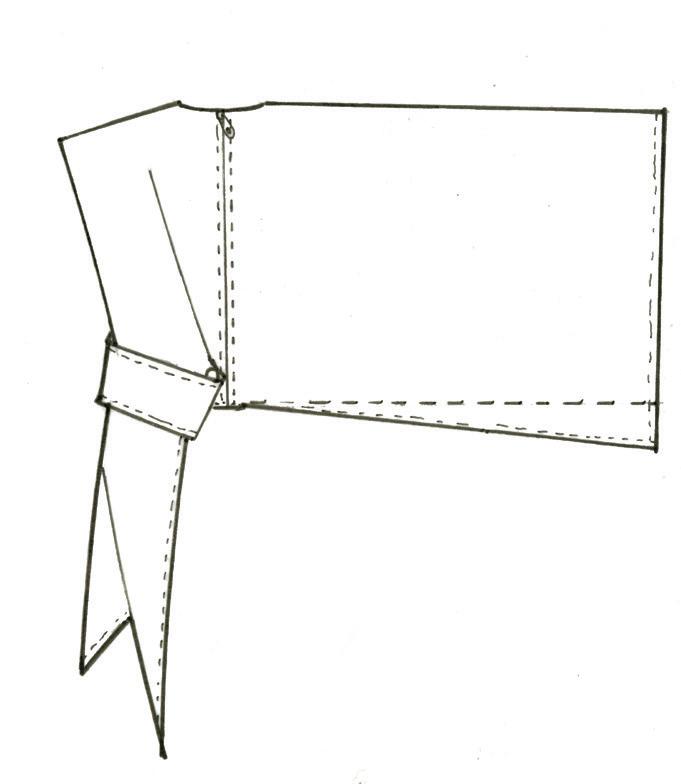

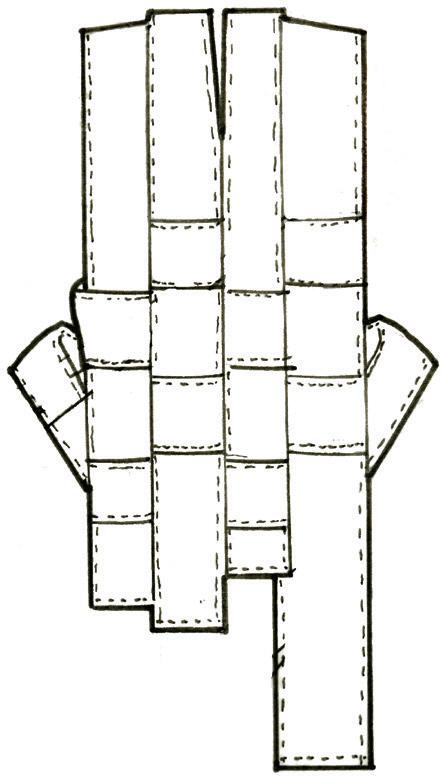

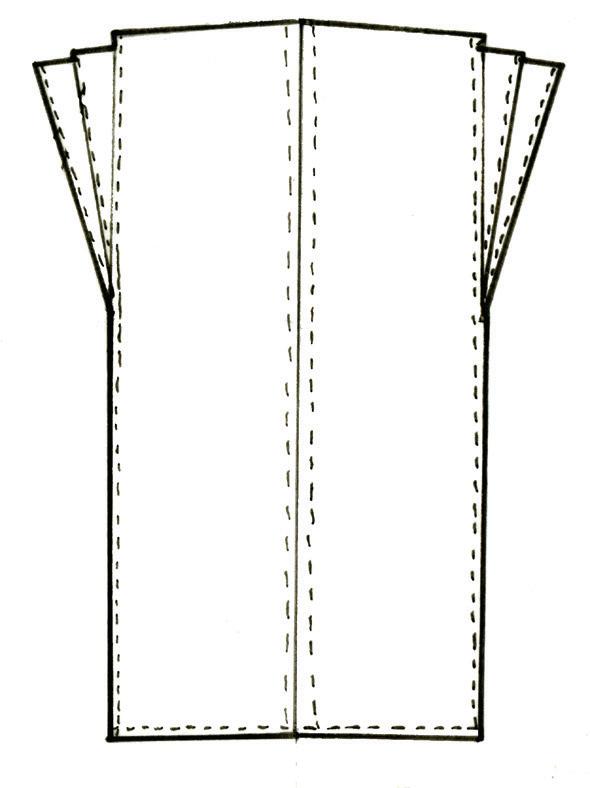

Garment ketches of draped squares of cloth.

When draped around the body, the textile in Figure 42 becomes dynamic- transcending its singularly directional stripes. The concept of wrapping a singular piece of square cloth, straight from the loom is an acknowledgement of indigenous Bolivian forms of dress, as I discussed earlier. My use of the square piece of cloth, unshaped by the machine as is customary in knitwear, and its movement around the curves of the female body open this piece to new possibilities. The excess fabric drapes and bows around itself. Its sheer, elastic, sculptural form revealing the continued stripes below- adding a new dimension. The striped pattern now becomes a plaid- a new pattern formed through the added element of the body.

Like Westwood, I look to historical garment as a nod to my cultural background. As I look back at my identity in Bolivia, I am influenced by Bolivian dress, though I choose not to adopt it. I drape square cloth around the dress form, resisting cutting into it and instead wrapping it around the body much like the Aymara. I am not concerned with concealing the body, but with using the fabric just as it was taken off of the knitting bed. Always a challenge, this form of draping creates new, interesting shapes, and redefines the edges of the body.

Raised in an American household, I was used to dressing in American clothing- often sportswear, yet I encountered indigenous Bolivian dress on a daily basis. This new merging of cultures present in my life creates an interesting hybrid when thinking about clothes and form. I am interested

FIGURE 43

in Bolivian dress as a form of identity, and when mashed with my way of dress, an American sportswear sensibility, it creates a new identity unique to myself.

The use of modern American sportswear in my work introduces new material and trim elements to my design. The introduction of zippers rather than pins as fasteners, set-in sleeves rather than straight sleeves and tank-tops are a few examples of these details. These additional sportswear elements give the traditional Bolivian garments new life- they are now more comfortable, less likely to fall off, and allow the woman wearing them to perform other activities with less cloth and more stable garments on their body. This, in turn, creates a new identity, and a new feeling on the body.

Creating a sculptural quality to the work was essential in allowing the clothing to transcend a “ready- to-wear” association. Still, I wanted it to be recognized as wearable clothing that was relatable to most people. This balance was achieved through patterning clothing in a traditional way, mixed with draping to create unique shapes. In addition, I chose to make the clothing slightly longer and wider than I traditionally would, to create the sensation of something other-worldly, something marginally strange and slightly out of place, but only slightly.

Thesis Collection

LOOK 1

Oversize dress: knit lurex, latex coating, dyed silk twill fabric

Gathered skirt: knit lurex, latex coating with yellow pigment

LOOK 5

Long coat: industrially knitted elastic, alpaca, polyester

LOOK 3

Long tunic: knit alpaca and superfine merino wool, felted

Gathered skirt: knit lurex, latex coating with yellow pigment

LOOK 4

Draped jacket: knit polyester and rayon, latex coating

Applique Skirt: knit lurex and cotton, latex coating with black pigment, glitter

LOOK 2

Short jacket: knit lurex, latex coating with blue and red pigment, cotton bias tape

Printed Tunic: digital print on silk

LOOK 6

Puffer coat: knit metallic yarn, wool, monofilament, rayon

Intarsia skirt: knit alpaca

Conclusion

The clothing I have created serves as an extension of Bolivian culture and history. As a Bolivian citizen, I continue the cultures’ deep tradition of textile design and making. Forever grateful to those teachers who have taught me how to knit my own textiles, I strive to accurately represent the people who helped raise and educate me.

As I move into the textile industry, I will continue to encounter questions concerning the industrialization of textiles, specifically knit garments. As a designer who values quality over quantity and craftsmanship, I have a responsibility to continue to move these ideas forward. I know that I will face pressures of a market increasingly hungry for disposable fashion, and this may inadvertently sway the decisions I make in the future. Still, it is my goal to continue the practice of knitting garments

with craftsmanship and superior quality in mind. Will I be able to continue making garments on manual machines for a large market? Or will this form of making eventually become obsolete due to rising labor prices and the thirst for fast fashion? Will I ever figure out a way to produce quality garments on the Stoll machine that mirror the unique look of a manual machine?

These questions play back and forth in my mind every day, and they will continue to be at the forefront of my design decisions, and how I intend my work to live on. I feel a responsibility to continue the tradition I have been taught, or else I risk it being lost to an increasingly automated form of textile making. At the end of the day, textiles are about those who make them and use them, and when we lose sight of this, textiles no longer hold the same meaning.

Bibliography

Adelson, Laurie and Tracht, Arthur; Aymara Weavings: Ceremonial Textiles of Colonial and 19th Century Bolivia; Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service; 1983

Cereceda, Veronica; Seminologia de los Textiles Andinos: Las Talegas de Isulga; Chungara, Revista de Antropologia Chilena; 2009

Freud, Von Dr. Sigmund; Uber Coca; General Hospital of Vienna. Centrallblatt für die ges. Therapie. 2, 289-314, July 1884.

Phips, Elena; Hecht, Johanna; Martin Cristina Esteras; The Colonial Andes: Tapestries and Silverwork, 1530-1830. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Yale University Press; 2004

Taussig, Michael; Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man - A study in Terror and Healing; The University of Chicago Press; 1987

Vaca Guzman, Gonzalo Iniguez; La Chola Pacena: Su Dinamica Social; Producciones Cima; La Paz, Bolivia; 2002

Wilcox, Claire; Vivienne Westwood; V&A Publications London; 2004

Young-Sanchez, Margaret; Tiwanaku, Ancestors of the Inka; Denver Art Museum, University of Nebraska Press; 2004