8 minute read

A TALE OF TWO BATTERS

from Daisy Cutter 003

Here are some batting statistics for two Test cricketers in the summer of 2022. 13 innings, 7 matches, sameconditions.

RUNS:327

Advertisement

AVERAGE:25.15

S/R:55.23

50s:2

TOPSCORE:67

DUCKS:0

CAREER AVERAGE: 23.84 (10 MATCHES) .

Now,imagineyou’vegottopicka squad for winter tours. You’re offtoPakistanandNewZealand, bothplacescapableofproducing flat tracks that are a lot easier to bat on than green English wickets. Both perfect places for batters to get some runs and confidence,wherescoringquickly maybeneededtoforcearesult. Do you pick one, both, or neither of the batters above?

RUNS:276

AVERAGE:23.00

S/R:57.26

50s:2

TOPSCORE:69*

DUCKS:0

CAREER AVERAGE: 27.26 (28MATCHES)

Cricketers #1 and #2 are respectively, if you haven’t guessed by now, Alex Lees and Zak Crawley– the incumbent England openers at the end of the 2022 summer. Looking at theirstatistics,theyhadbasically the same summer and, whilst Crawley had the better average in his career overall, he had been given a much longer rope over his international career. Into the winter,thattrendonlycontinued, with Crawley keeping his spot in England’s top order and Lees unceremoniouslydropped.

Evenafterputtingasidethefact that Rob Key, England Men’s Director of Cricket, was a mentortoCrawleyatKent,there is an obvious disparity between himandLees:theirbackgrounds.

Zak Crawley went to Tonbridge School, which boasts over £11.5k a term in fees. His dad, known as ‘Terry the Till’, made the Sunday Times Rich List as a trader in the City.

Alex Lees went to Holy Trinity Senior School (now Trinity Academy) in Halifax, his dad getting him into cricket through local clubs. In fact, Lees’ school was academised when he was 17 due to poor performance in inspections, so one can only guess that it was not offering a similar level of education to a fee-payingschool.

Crawley’s school was also Ed Smith’s – who was National Selector when Crawley debuted – alma mater. Smith was also SelectorforSamBillings’debut,a fellowKentplayerwhojumpedto Crawley’s defence on Twitter when people suggested that his background could be helping his cricketcareerprogress.

Alotofpieceshavebeenwritten about how cricket has been made the pursuit of private schools and not state schools: the selling off of land, the time and expenses required. However, what is maybe not discussed as much is that simply having your face‘fit’isequallyasbeneficialto your career as the private education that shaped it. Would Crawley have benefitted as muchifhedidn’thaveassociation through his upbringing with a formerEnglandNationalSelector and the Current Director of Cricket?

8 of the 15 England Men’s squad picked for the NZ tests went to private schools, over 50%, compared to 7% of the country. The current England men’s NationalSelectorandDirectorof Cricket both attended private schools at one point or another during their education. It’s the culture and the norm in elite cricketinEngland.

Cricket in England has a deepseated and worsening issue with class, one which requires a twofold solution. Money needs to be spentatthebottomofthegame to make it so every single child hasequalaccessandopportunity tocricket.

“That makes total sense and I havesomestrongviewsonit!!”

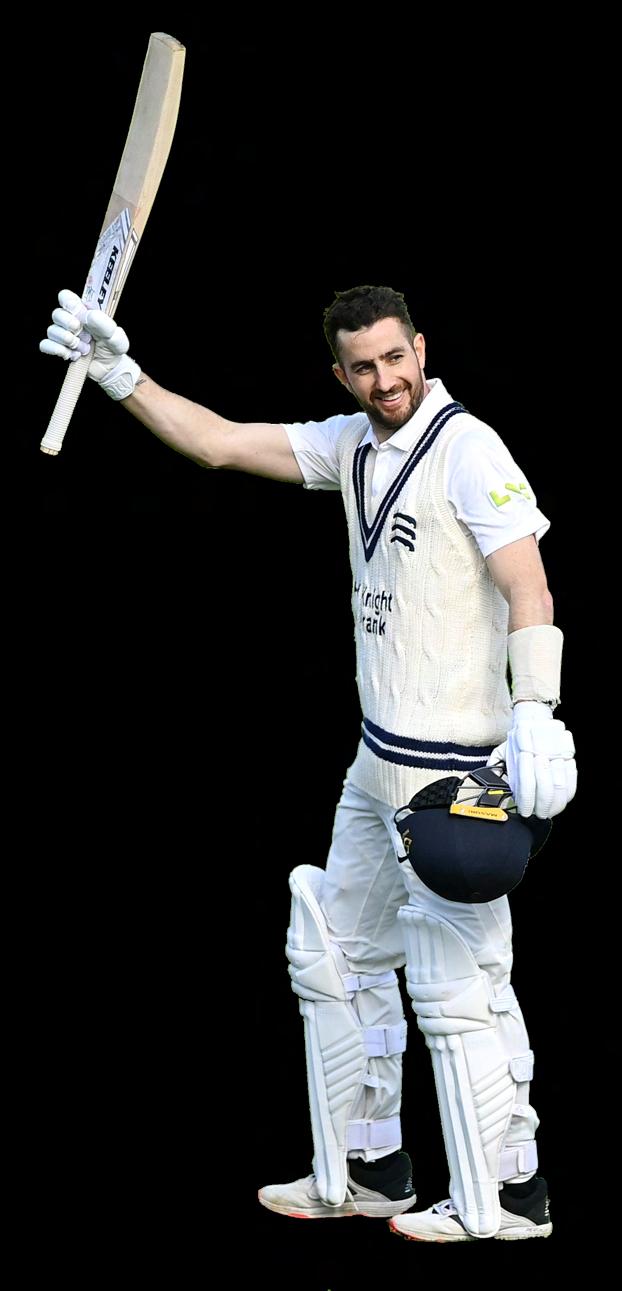

Several days after meeting up with Stevie Eskinazi at Lord’s to talkcricketforacoupleofhours,I sent him some extra questions and got the ideal response. As a fan, it’s very rare to feel like you know what a player thinks about almost anything. Given cricket’s track record on outspoken players, you might think to yourself that’s not such a bad thing-maybeit’sbestnottoknow - but fortunately for us Stevie is not just happy to share his opinions on topics that we care about, but is also, in my very professionalopinion,soundashell.

“I probably represent the bogstandardcountycricketplayer.It would be cool for people to know we’reinterestedinmorethanjust ourselves and cricket. And for people who are thinking that everyone in the inner sanctum of thegameisjusthappywithhaving their own group of people,very similar to themselves, to know that it’s particularly not the attitudeoftheplayers.Iknowthe people that I play with, and the club, and that’s actually everything that we don’t want to be.”

Middlesex and beyond. He volunteered himself for the club’s Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion committee last year, and sees players as having a pivotal role in influencingtheapproachto change:

“As professional players we are at the forefront of people’s minds,wehavea certainfollowing

It’sapparentthatSteviesincerely wantstomakeadifferenceat and I think we have a certain obligationtoshowthat,notonlyis cricket somewhere people can go and feel safe and enjoy themselves, but there’s a clear pathwayforanybodywhodesires to take their game to the next levelandpushtomakeittheirjobandthattheyfeelliketheywillbe valued for their ability. That comes from the way we treat people, but alsofrom how we act in interviews and the words and languageweusetoshowthatwe are part of the solution. We have anopportunityasyoungpeopleto get on the front foot, and I just think:“whythefucknot?””

His home ground of Lord’s is a particularly alienating venue, the kind local young people might come to for a match and think “this isn’t the place for me”. The demographicmakeupoftheteam or the crowds don’t correspond tothatoftheareathatMiddlesex is supposed to represent, wherethe team visit local schools tointroducekidstocricket.

“Ithinkclassisprobablythemost significant barrier to participation. It’s an expensive sport to take up, there are high barrierstoentrywhetherthatbe club costs, equipment costs, even making nets or making a cricket pitch.It’salsogivingupaminimum offiveorsixhours,whichalotof familiesdon’thave.It’salotof timeandmoneytopursueasport whereyoumaynotfeelyoufitinwe have a real responsibility to make it worth it. You can’t just pick up a cricket ball and go and play, and that’s something that’s reallydisappointing." treat someone who is different fromtheminsomeway,Isayhave the weird conversation up frontask people “how do you want to be treated, what are you up for, what do you not want to be part of” and then go from there. People will shy away from it because it’s awkward, and it means addressing the difference headon,butifyoudon’tdoitthen you’re just going to be weird all the time, and that’s what makes peoplefeelexcluded.

Middlesex are making efforts to improve their community outreach, but some logistical barriers are difficult: in the builtup inner city, schools can’t pop to a local cricket club to use the facilities and kit for a PE lesson, andthere’slittlespaceinwhichto play even if the interest is there.Talent, enthusiasm and the willingness to work hard all count for a lot, but for a working-class Londoner you’ve fallen behind before you’ve even looked at a cricket ball. It’s no surprise that talented kids end up choosing to pursuesportslikefootballinstead - kits are cheap, and it can be practisedalmostanywhere.

Stevie sees changing dressing room culture as a key part of improving inclusion, and his responsibility as a senior player. It’s a more nuanced task than a wholesale elimination of “banter” (say the word three times in the mirrorandJustinLangerappears with a pack of Uno cards). In a sport that’s still dominated by white, privately-educated men, manyofwhomdon’thaveaworld of experience with people different from themselves, real empathy is key - not just knowing where the line is, but understanding why that’s where itis.

“We need to understand how some people might find some things uncomfortable and be critically aware of that, rather than just saying “ah well, what happens in a dressing room stays in a dressing room”. I really hope that I can help leave behind a feelingthatanyonecanwalkinat any given time and feel comfortable, and nobody’s going to be worried about how certain people might treat them. I hope that if I were to say something that wasn’t respectful I would be pulled up on it, and the same for others.

“The game in general needs to be willing to listen to the stories of peoplewhohavefeltundervalued. Then you can ask the right questions and hopefully then be a little more targeted in the way that you try to help. As players andprofessionalteams,youdoas muchasyoupossiblycantomake sure that there’s a really broad level of understanding of every background, of every person’s situation, so that if somebody weretoenteryourdressingroom, you could be really understanding andvaluethemasanequal,whichi think is all that anyone really wantscomingin.”

This attitude carries through to the cricket pitch, and he prefers English cricket over the “oldschool, bullish and brash” Australianversionforthisreason:

“Whenpeoplearen’tsurehowto

“The players aren’t, they are amazing people, but the whole culture of Australian cricket is still stuck a little bit in the 90s. They think making people uncomfortable is the way they need to win, and boys, it just isn’t that way anymore. No-one’s scared of that attitude, it never makes the other guy play worse. InEnglanditfeelslikeit’sjustnota thing anymore - or we play so much against each other that everyone’s really friendly, on the county circuit especially. Doesn’t mean you’re not competitive, doesn’t mean you’re not trying to get them out or beat them, but you don’t have to be a dick to themanymore.”

✿✿✿✿✿

Having been overlooked in the 2021 and 2022 drafts for The Hundred, Stevie’s time has come this year, being picked up to join the freshly-revamped Welsh Hula Hoops team after watching London Spirit from the wings at Lord’sfortwoyears:

“I’m so excited because it is designed to be super accessible, to grow the women’s game, to make people want to come and watch cricket who never felt like they could before. And it looks so much fun. We [Middlesex] played 50overcricketatthetime,with maybe200fansatanoutground, whichcanberomanticifit’sanice day,butthenyoucomebackhere in the evening, watch the game and think ‘that looks really fun, andtheseguysareherewithabig crowd, in a colourful kit, with a coolDJ."

We talk about how franchise cricket has been fundamentally disruptivenotonlyonastructural level but on an ideological one, allowing players to assert themselves as workers and challenge traditional ideas about loyalty:

“While we like to think of cricket as this romantic industry where loyalty is really high and people play for pride, for their county or their country … what can sometimes get lost is that there are families who depend on us, and you’re trying to create a senseofsecurityforyouandyour family. If you speak to anyone in “normal jobs” and said you can work for 40% less time and earn three times as much money, it’s a no-brainer, but when it comes to cricket, people say “you can’t not play for Surrey or Sussex and go and play in the IPL, it’s not what you do” - and it’s like, would you likesomeonetoturndown£200K that when they’ve finished their already short career is going to helpstabilisetheirfutureand theirfamily?” opportunities surely made it easier to quit the South Africa team-somethingthatwouldhave been much harder for (particularly female) cricketers just a few years ago. They undeniably afford players at that levelagreaterfreedomofchoice in their careers, and a bargaining chipiftheyareunhappywiththeir treatment.

Recent events have highlighted a shiftinpowerdynamicsincricket with the opportunities provided by franchise teams. Dane van Niekerk was controversially dropped from the South Africa Women’s World Cup team due to failing a portion of the fitness test, despite being arguably their most valuable player. She spoke about how she was confused and alienated by the decision, that she didn’t feel valued by Cricket South Africa anymore. Weeks later, she retired from internationalcricket.

No matter how much people argue about it, the landscape of cricket is permanently changing, andcountiesandtheECBfacethe challengeofchangingalongwithit toretainplayers-anditmightnot beabattletheycanwin:

With places in Royal Challengers Bangalore and Oval Invincibles’ squads, van Niekerk can continue to make her living playing cricket, and through that hopes to find herloveforthesportagain.These

“The first thing is: it’s really the responsibility of the game and teams to create an environment that people love to play in, feel challenged and want to be there. The second thing isunfortunately,wedon’tliketosay it - money. Salaries have to stay competitive in the market becausefundamentallyit’sajob,a short-term one that people can now make really strong livings from. If it’s going to effectively cost you earnings to go and play for England for a long period of time, it’s probably going to be somethingpeopledolessandless. Franchise cricket allows you to develop your game, to go and traveltheworld,tomakelotsof money…Idon’tseeanythingabout those things that isn’t going to drag a whole heap of players to go and want to be a part of them.”

Thethemethatkeepscomingupis money. When we talk about lack of diversity in cricket, when we talkabouttheclassdivide,money is front and centre - whether that’sthecostofplaying,thecost of attending, or the competitiveness of players’ salaries. Anyone who is serious aboutimprovingdiversityinthe game needs to know that they’re trying to bring in more people for whom money is a constant concern in life, rather than a constant presence. We feel confident in saying that Stevie gets it - and we’re glad to know he’s there behind the scenes tryingtoaffectchange.

“I’ve been very lucky, so I would love for more people to feel the way I have. If the team did well that’dbeanicethingforpeopleto rememberyouby,itwouldalsobe nice to leave the game knowing that diversity at Middlesex is in a betterplacethanwhenIstarted.”

We’re looking forward to seeing whatStevieachievesbothonand off the pitch. Regardless, he’s a DaisyGirlforlife.