茶 道

THE ART OF CONTEMPORARY JAPANESE TEA CERAMICS

T H E C R A F T

O F T E A

THE ART OF CONTEMPORARY JAPANESE

TEA CERAMICS

茶 道 具

Dai Ichi Arts, Ltd is a fine art gallery exclusively dedicated to celebrating modern works of ceramic art from Japan

Since our inception in 1989, we have focused on placing important Japanese ceramics at the center of New York's contemporary art scene. The gallery has introduced pieces to the permanent collections of several major museums, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Art Institute of Chicago, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the Princeton University Art Museum, and many more

We are committed to providing authoritative expertise to collectors, liaising with artists, and showcasing inspiring exhibitions and artworks We welcome you to contact us for more information

On view: September 12 - 20, 2024

On the occasion of Asia Week New York

Exhibition catalog

In a world where we often seek sanctuary from the hustle and bustle, the ritual of drinking tea offers a serene escape Our autumn exhibition, following the warmth of summer, invites you to experience this tranquility through a curated selection of tea objects We present a variety of tea bowls, tea caddies, and water jars, each crafted by talented artists in different glazes and shapes, all designed to create an atmosphere conducive to mindfulness and personal reflection Additionally, we showcase rare scrolls and paintings by distinguished potters to help you curate your own sanctuary space

We are honored to introduce two distinguished contributors to our catalog The first is Mark Tyson, a collector, potter, and educator Mark shares his deep passion for collecting and creating tea bowls, offering insights into the profound significance these objects hold for him and those he inspires He also curates exhibitions that feature tea bowls by international artists.

Our second guest is a tea master from Japan, Yoshitsugu Nagano Nagano studied design and modern art in college, and through his practice of

tea, he discovered “ a completely new category of art ” Since then, tea has become an integral part of his life Nagano-sensei has dedicated himself to promoting tea culture globally Since moving to the U S in 2019, he has advocated for tea as a daily respite from the demands of modern life He envisions tea becoming as popular as sake and beer, embraced by people of all ages, from children to adults We wholeheartedly welcome him to the ceramics community as someone who is exceedingly thoughtful and reflective about how ceramics transform a tea space

Through this collection, we offer masterfully crafted ceramic objects that we hope will seamlessly integrate into your life, fostering a slower, more mindful, and healthier lifestyle May these artful tea utensils inspire you to embrace the art of tea and find peace in its simple yet profound rituals

Finally, I extend my heartfelt thanks to our diligent team at the gallery Kristie Lui, Haruka Miyazaki, and Yoriko Kuzumi for their mindful and creative efforts in making this catalog and exhibition possible

Beatrice

Chang, August 2024

THE ART OF COLLECTING

AN ARTIST’S PERSPECTIVE

BY MARK TYSON

(Right) Mark pictured in his home in front of a shelf of Hagi tea bowls (Left) Shelving unit in Mark’s home showing his collection of wood-fired tea bowls, all of original design

I love collecting tea bowls because, as handmade objects, no two are the same Tea bowls are functional but are also incredible pieces of sculptural ceramic art, celebrating the beauty of imperfection, fired clay, naturally accumulated wood ash, or an amazing glaze A seemingly simple object is actually quite complex and is both visual and tactile art It should be the right size and weight, have good balance, and feel good in your hands due to its shape and texture It should also have an interesting foot, room for the tea master’s fingers to slip beneath it, a rim that will not snag on the silk cloth, and an inner surface that will not harm the bamboo whisk

The process by which they are made can vary greatly, from the forming to the firing The amount of labor, commitment, and passion required to acquire and process the clay, form and sculpt the bowls, bisque-fire the bowls, glaze and wad the bowls, load the kiln, acquire and process the wood, fire the kiln, unload the kiln, and clean up the bowls and the kiln is really quite incredible. I especially enjoy using all of these different bowls because they are functional art Why drink from an ordinary mug or glass when you can drink from and enjoy a piece of art? They also happen to be the most valuable ceramic objects on earth

As an artist, those are also all the reasons why I like to make tea bowls I love never making two of the same; they are all individuals It’s never boring or repetitive It’s a meditative labor of love, and all of the ancillary work, with the clay and the wood and the kiln, is good exercise These are also all of the reasons why I like to teach others how to make and fire tea bowls and to educate their eyes and fingers with bowls from my collection I love to watch the amazement in their eyes and the smiles on their faces and listen to them tell each other why they like this one or that one the best as they view and handle a tea bowl “show and tell” that I bring to class It’s very rewarding to see them eventually make fantastic bowls themselves

Curating a tea bowl exhibition, so that I can share all of this with the general public and help to educate them about this incredible art form and the tea ceremony that they are used in, is just the next logical step in this whole journey I will be very happy to present the 3rd Philadelphia International Tea Bowl Exhibition at the Community Arts Center in Wallingford, PA, in February 2025 Mark Tyson, August 2024

THE ART OF SHARING TEA

A TEA MASTER’S

PERSPECTIVE

BY YOSHITSUGU NAGANO

The Tea Ceremony, or chanoyu (茶の湯), is a Japanese tea ritual that emerged around 650 years ago, rooted in the samurai culture of Japan In their perilous daily lives, samurai drank matcha not only to sharpen their focus but also to calm their minds, aiding in their survival What began as a simple act of drinking matcha gradually transformed into a highly ritualized practice, involving the creation of dedicated tea rooms, the careful arrangement of tea utensils, and the deliberate preparation and consumption of tea The tea ceremony ritual became a means to alleviate the intense stress and pressure of constant warfare, and chanoyu evolved into a form of 'samurai meditation ' I believe that chanoyu remains a significant cultural practice that offers empathy, emotional support and valuable insight, enriching the lives of modern people, especially in today’s urban environments like New York

Chanoyu has traditionally been practiced by samurai and wealthy merchants in urban settings. The tea rooms where it takes place, known as mountain retreats within the city, are carefully designed to evoke the serenity of nature, even amidst the bustling city Warlords would dedicate a part of their residence as a tea room, using them for daily meditation A traditional tea room is intentionally

dim, with only a few small windows, which limits visual stimuli and enhances other senses like hearing, smell, taste, and touch While modern life is dominated by visual input over 80% of information is said to be processed through sight in a tea room, one can engage with the world through all the senses, much like being in nature This sensory balance allows the mind to rest and gradually calms the heart Such an experience aligns with the Zen principle of being fully present 'right here, right now,' freeing oneself from the past and the future to rediscover one's true self in the present moment

Chanoyu embodies the art of discovering beauty in imperfection The aesthetic concept known as “wabi” represents the pinnacle of beauty, a refined sensibility that emerges only after one has fully experienced and understood perfect beauty In New York, people are immersed in and accustomed to being in touch with a world of top-tier art, cuisine, and fashion. However, many of the tea utensils used in chanoyu deliberately reject perfect proportions, embracing irregularities and spontaneity instead At first glance, these objects may seem plain or lacking in beauty, but through daily use and familiarity, their subtle, inherent beauty gradually reveals itself When you become accustomed to seeing a brilliant full

moon, eventually you will also become allured to a hazy moon covered by clouds Wabi cultivates a sensitivity that helps us notice and cherish the richness and delicate beauty that often go unnoticed in our surroundings

Another essential aspect of chanoyu is the pursuit of harmony between nature, objects, and people In this practice, the tools used are treated with great reverence, embodying the belief that through these objects, people can forge a deep connection with nature Without the tea bowl, for instance, we cannot drink matcha The tea caddy that holds the tea, the water jar for storing water, and the kettle for boiling it each of these tools links us to the energy of the natural world through their use

The teachings of chanoyu offer valuable lessons that can enrich the lives of not just samurai but also those of us living in the modern world The practice is simple at its core: chanoyu literally means “tea and hot water ”

Select your favorite tea bowl, boil fresh water each morning, prepare matcha in natural light, and drink it slowly As you hone your senses and experience a sense of harmony, the aesthetic of wabi will begin to awaken within your heart.

Yoshitsugu Nagano, August 2024

C H A W A N

T E A B O W L

Sugimoto Sadamitsu 杉本 貞光 (b. 1935)

Shigaraki teabowl “kago” 信楽茶碗 籠, with signed wood box and accompanying letter by an abbot of the Daitokuji temple 大徳寺, stoneware, (h) 9.9 × (diameter) 12.4 cm

Stoneware, (h) 8.8 × (diameter) 12.1 cm

Kawamoto Goro 河本五郎 (1919-1986)

Yellow ash glazed teabowl 黄灰釉 茶椀

With signed wood box, stoneware (h) 8.8 × (diameter) 11.6 cm

Oishi Sayaka 大石早矢香 (b. 1980)

No 6 Tea bowl, 2024

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 11 × (w) 15 × (d) 14 cm

Shingu Sayaka 新宮さやか (b. 1979)

No 37 Calyx tea bowl 萼容 碗, 2024

With signed wood box, mixed clay with glaze slip, (h) 8 7 × (diameter) 12 cm

Wada Morihiro 和太守卑良 (1944-2008) "Kaku-gen-jho-mon-ki" Tea bowl 赫玄条文茶碗, 1990's, with signed wood box Ceramic Society of Japan Award 日本陶磁協会賞, stoneware, (h) 8 × (diameter) 13 cm

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 8 6 × (diameter) 11 9 cm

(Middle) Richard Milgrim Black teabowl, hikidashi-kuro chawan 引出黒茶碗

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 9 × (diameter) 10 9 cm

(Right) Yamada Kazu 山田 和 (b. 1954) Hikidashi-kuro teabowl 引出黒茶碗, 1990's

With signed wood box and accompanying lacquer box, stoneware, (h) 9 5 × (diameter 12 6 cm

Koie Ryoji 鯉江 良二 (1938-2020)

White tea bowl 白碗

With signed wood box, porcelain, (h) 6 8 × (diameter) 13 2 cm

With signed wood box, stoneware with platinum glaze (h) 9.5 × (w) 13.5 × (d) 12.5 cm

Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 土平 (1929-2013) Teabowl with spot glaze 茶碗斑釉 With signed wood box, stoneware (h) 8.6 × (diameter) 10.6 cm

M I Z U S A S H I

W A T E R J A R

Miwa Ryosaku 三輪 龍作 (b. 1940)

Water jar in shape of Hakureiko 白嶺湖, with signed wood box Stoneware, (h) 19 0 × (diameter) 31 7 cm

Furutani Michio 古谷道生 (1946-2000)

Shigaraki water jar 信楽水指 with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 13 4 × (diameter) 20 8 cm

Yamada Kazu 山田 和 (b. 1954) Kiseto water jar 黄瀬戸水指, 2000's, with signed wood box Stoneware, (h) 20 × (diameter) 20 2 cm

Takiguchi Kazuo 滝口 和男 (b. 1953)

Water jar: "Persimmon trees in mountain villages" やまざとのかきのきは With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 11 × (diameter) 14.6 cm

Kawase Shinobu 川瀬 忍 (b. 1950) Celadon water jar 青磁水指, with signed wood box, celadon glazed stoneware, (h) 14.7 × (diameter) 26 cm

Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 土平 (1929-2013)

Golden water jar with inlaid deers and rabbits 金露彩象嵌

指, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 19 × (diameter) 16 cm

Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 土平 (1929-2013) (Left) Teabowl with spot glaze 茶碗斑釉, with signed wood box, stoneware (h) 8 6 × (diameter) 10 6 cm

(Right) Sometsuke water jar with mountain and river image 染付八角山水文 水指, with signed wood box, porcelain, (h) 16 × (diameter) 15 2 cm

Maeda Masahiro 前田 正博 (b. 1948)

Water jar with blue and silver pigments 色絵

銀彩水指, with signed wood box, porcelain (h) 16.6 × (diameter) 22.4 cm

C H A I R E

T E A C A D D Y

T H E A R T O F S H I F U K U

The Japanese tea ceremony is rich with tradition, where every item, including the tea caddy and chawan, is treated with the utmost care These essential objects are often stored in intricately designed brocaded silk pouches with braided silk cords The patterns on these pouches can range from traditional kimono motifs to unique, original prints, each showcasing the meticulous craftsmanship and high technical skill required to create them. These pouches, known as "Shifuku," are the unsung heroes of the Japanese tea room.

"Shifuku" (仕服), literally translating to "clothing for tea wares," is a lesser-known yet essential element of the tea ceremony While Shifuku is just one layer among the many pouches, boxes, and wrappings used to safeguard treasured pieces, it plays a unique role in elevating the status of the object it protects This adds to the air of ceremony and ritual that naturally permeates the chashitsu (茶室, Japanese tea room) or tea space

Much like tailored clothing, each shifuku is custommade to fit the specific item it protects Over the course of the ceramic object’s life, perhaps having passed through several hands, a single tea caddy may accrue multiple “clothes” due to owners commissioning new Shifuku, whether for special occasions, to add a bespoke quality to the life of the ceramic, or simply for utility- to replace an older textile Needless to say, this textile is a finely crafted part of the life of a tea caddy or tea bowl, and helps to set the tone in the tea room space.

This unique combination of utility, bespoke craftsmanship, and thoughtful curation fosters a deeper, more personal connection between the owner and the tea caddy The Shifuku transforms the graceful ceramic object into a cherished companion

Ueda Juho 上田寿方(b. 1925)

信楽茶入

With signed wood box, stoneware (h) 5.0 × (diameter) 7.6 cm

Fujiwara Yu 藤原雄 (1932-2001)

Bizen tea caddy 備前茶入, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 8 8 × (diameter) 7 6 cm

Isezaki Jun 伊勢崎淳 (b. 1936)

Bizen tea caddy 備前肩衛茶入, with signed double wood box, stoneware, (h) 8 8 × (diameter) 6 8 cm

Y A K I S H I M E

Nishihata Tadashi 西端 正 (b. 1948)

Tanba tea caddy 丹波茶入, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 8.1 × (diameter) 7.6 cm

It is not an overstatement to say that yakishime is one of the major forces in contemporary Japanese ceramics Many artists in both historic yakishime centers like Shigaraki, Bizen, and Tanba as well as other areas of Japan choose yakishime as the focus of their artistic practice

Yakishime, which combines two Japanese verbs to fire (yaki/yaku) and to harden (shime/shimeru) refers to a non-glazed ware that is fired for long periods of time at over 1,000 degrees Celsius in a wood-fueled kiln While yakishime resembles terracotta and earthenware, the long, hightemperature firing process makes it impervious to water.

Yakishime is appreciated for its accidental marks, spots, and the glazes naturally formed when wood ash attaches to and petrifies on the clay surface during firing Depending on its location in kiln, red, reddish brown, and beige colors appear around the clay body In some areas, ash glaze creates translucent blue and green colors, and matte ochre and black colors

Clays sourced in Shigaraki and Iga also have feldspar deposits and small stones, which in intense heat become white speckles and small bursts that further accentuate the roughness of the surface

Excerpt from an essay “From Everyday to Extraordinary: Yakishime in Japan” for Dai Ichi Arts, LTD by Natsu Oyobe University of Michigan Museum of Art, February 2024

With signed

b. 1971) dy 茶入 ) 6.5 cm

Hanging scroll with tea bowl drawing, ink and paper

Image: (h) 59.9 × (w) 32.7 cm

Mount: (h) 139.7 × (w) 40.8 cm

十 ( 1 9 1 7 - 2 0 0 6 )

This scroll reads: “天下松⾵ 碗中 / てんかまつかぜひとわ んのなか / Tenka matsukaze hitotsuwan no naka”

“In a single bowl, the pine breeze from the heavens”

The couplet sets a vivid scene: the wind from the sky rustling through the branches of a verdant pine tree, a symbol of virtue and nobility This serene scene is encapsulated in the single bowl by virtue of its presence and existence in the tea room The scroll’s inscription encourages meditation on the tea bowl, and the artist has depicted one such bowl in his Kakemono (掛物, hanging scroll, pictured right)

Nishioka Koju was a celebrated karatsu potter who has long been considered the progenitor of modern karatsu ware He drew upon the Karatsu ceramic tradition to create his own surface expressions Interested in Korean import techniques in the Karatsu region, he researched the history of Karatsu ware extensively This shines through in the iron-painted motifs most recognizable in his work His brushwork showcased a profound freedom of expression He studied under the famous potter and living national treasure Koyama Fujio (1900-1975), who was a scholar of ancient Chinese and Korean ceramics

In his lifetime, Nishioka Koju opened three kilns The Kojiro kiln in 1971; Koju kiln in 1981; and finally, Kaga Karatsu Tatsunokuchi Kiln in 1991

Elegant calligraphic strokes painted with an iron underglaze adorns the surface of the tea caddy pictured on the right, representing river reeds The same motif can be found on the scroll painting on the right, which one might imagine to be painted in the synonymous fashion.

Morimoto Tokoku 森本 陶谷 (1901-1985)

Tanba tea caddy 丹波茶入, with signed wood box stoneware, (h) 10 4 × (diameter) 4 8 cm

K A K E M O N O

H A N G I N G S C R O L L S

P A I N T I N G

Ink and clay have been deeply intertwined as artistic mediums in Japan for centuries The role of ink on paper, such as for preliminary sketches and designs for various ceramic objects, have served both utilitarian and aesthetic purposes throughout Japanese art history On the other hand, ceramic objects such as flower vases are also natural companions to the display of Kakemono, or Japanese hanging scrolls, in dedicated alcoves (床の 間 tokonoma) within a traditional Japanese tea room

Unlike painted sliding and folding screens, Kakemono (掛物 literally translating to “hanging thing”) only became widely popular in Japan during the late Kamakura period (1185–1333), aside from their earlier use in memorial paintings within Buddhist temples and Shintō shrines The introduction of hanging scrolls from China in the early fourteenth century prompted a rethinking of indoor spaces to accommodate their display Such scrolls might offer a conceptual guide to the way that one might orientate themselves with, or gaze upon the ceramic object This symbiotic and evolving relationship between ink and clay has continually offered fresh perspectives on how objects interact within a shared space.

The world of Japanese ceramics is a vast realm of beauty, philosophy, design, and artistry While potters often consider ceramics the core of their craft, many master potters in Japan also engage in a disciplined practice of calligraphy and ink painting,

producing exquisite works not only in clay but also in ink and paper The art of two-dimensions challenges the potter to consider surface and composition Some may paint on paper during the ideation process for iron underglaze designs on their ceramics, while others recreate particular pots or tea bowls on paper to express their reverence for object itself Conversely, practitioners of calligraphy often delve deeply into the philosophies of the tea ceremony ritual, a subject rich with intellectual depth that fosters new meditations on craft and space

One notable figure whose work expresses the symbiosis of ink and clay is the master potter Arakawa Toyozo Arakawa Toyozo, the renowned sixth-generation potter of the Kōbe kiln, is celebrated for his remarkable revival of Shino ware, a style that had faded from existence by the 18th century His research, sparked by an inspirational encounter with a Momoyama period shard of Shino, led him to become the first potter to revitalize Momoyama period firing techniques, which contributed to the modernization of Shino and Oribe glazes For his scholarship and technical skill in Shino ware, he was designated a Living National Treasure in 1955. His intellectual and scholarly approach to recreating ancient Shino tea ceramics also involved the practice of painting and calligraphy, which he used to reflect on the philosophies of tea ware and object-hood The scrolls shown in this exhibition provide rare insight into another facet of his ceramic practice

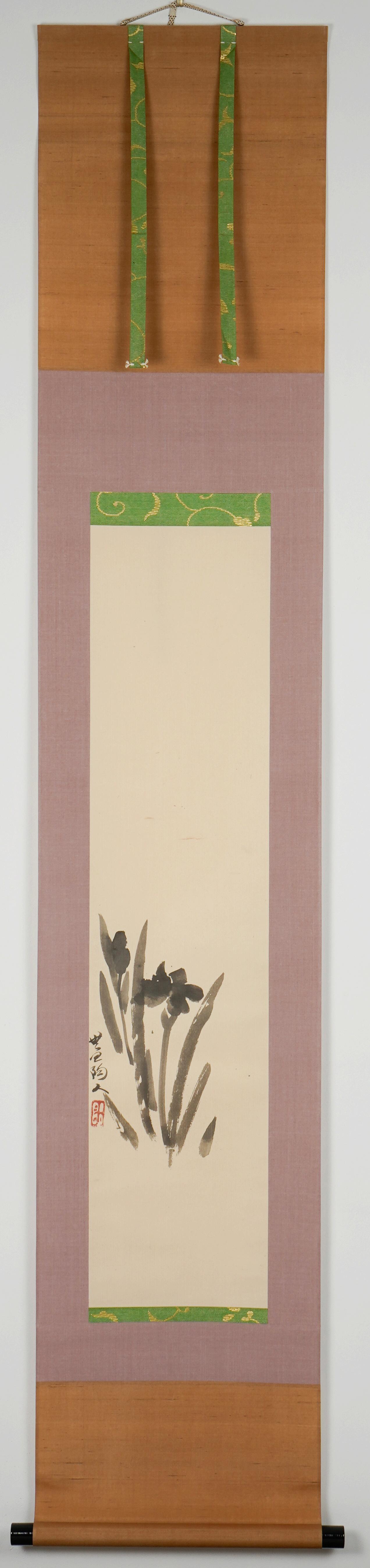

This simple hanging scroll features an elegant, decisive composition of Iris Japonica 杜若乃図 (Kakitsubata Osamu-zu) It bears the artist signature 無⽥陶⼈ Muta Tojin*

In Japan, the iris has long been cherished as a symbol of wisdom and virtue, with references to it appearing in Japanese literature and art as early as the 12th century A notable example is found in The Tale of Ise (Ise Monogatari). In this story, the protagonist, exiled from Kyoto, pauses at Yatsuhashi, where a river splits into eight channels, each crossed by a bridge. Inspired by the sight of irises, he composes a nostalgic love poem: The first syllable of each line in the poem spells out the Japanese word for irises (kakitsubata かきつばた):

Karagoromo / kitsutsu narenishi / tsuma shi areba / harubaru kinuru / tabi o shi zo omou

I wear robes with well-worn hems, Reminding me of my dear wife I fondly think of always, So as my sojourn stretches on Ever farther from home, Sadness fills my thoughts.

Translation by John T Carpenter, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Arakawa Toyozo 荒川豊蔵 (1894-1985)

Hanging scroll with water iris 杜若乃図

With signed wood box, Japanese paper with ink

Image: (h) 84 0 × (w) 43 6 cm

Mount: (h) 156 2 × (w) 34 2 cm

*Arakawa Toyozo had begun using an alternative "Literati" or artist name 無⽥陶⼈ Muta Tojin after 1972

Takeni jogeno fushiari

"The bamboo has joints from top to bottom"

The scroll carries profound Zen Buddhist connotations related to strength, weakness, and power It highlights that the strength of bamboo lies in its joints, implying that strength can vary between the upper and lower segments of a single stalk The couplet is part of a larger Chinese proverb/couplet, which states: 松無古今⾊、⽵有上下節, which translates to "The pine tree's color is timeless; the bamboo has joints from top to bottom "

One interpretation lies with the Japanese historian Haga Koshiro (芳賀幸四郎). In his book, “Shinpan Ichigo-Mono 新版 ⾏物, " he writes:

“[ ] It is a fallacy to ignore discrimination between men and women, old and young, while insisting only on the aspect of human equality, or, on the other hand, to recognize discrimination between rich and poor, above and below and not recognize equality as a human being, both of which are based on only one aspect of things It is a truthful and complete view to see equality as discrimination, discrimination as equality, and equality as equality ”

Here, Haga Koshiro describes that this couplet illustrates the concept of equality and discrimination "No change in color of the pine through the ages" represents the uniformity of equality, while "Bamboo with distinct nodes above and below" highlights the clear distinction of discrimination Together, they express the universal truth in Zen Buddhism that equality and discrimination are intertwined

This couplet is a popular phrase practiced in calligraphy, particularly in scroll paintings. With assured strokes, the calligrapher inscribes this simple yet profound declaration of humanity's path in the world It prompts introspective questions for both the viewer and the artist: "Are we perceiving the true essence with an unbiased heart, or are we being misled by our mind?" This phrase invites one to clear the mind and engage in deep reflection

The dated inscription next to the above couplet reads: 昭和壬⼦ 47年 year (47th year of Showa, 1972) It is signed with Arakawa Toyozo's alternative name: 無⽥陶⼈ Muta Tojin*

*Arakawa Toyozo had begun using an alternative "Literati" or artist name 無⽥陶⼈ Muta Tojin after 1972

Arakawa Toyozo 荒川豊蔵 (1894-1985)

Hanging scroll: 竹上下有節 Takeni jogeno fushiari "The bamboo has joints from top to bottom” c. 1972

With signed wood box, signed and dated 1972 by the artist, Japanese paper with ink Image: (h) 86.3 × (w) 33.0 cm Mount: (h) 165.1 × (w) 41.1 cm

LANDSCAPE OF A DREAM

At the base of the image of Mt Fuji, to the right, Arakawa Toyozo has written a single Kanji character “鷹” (Taka), meaning “hawk ” This painting presents a curious relationship among three traditionally auspicious and quintessentially Japanese symbols: two eggplants, one hawk, and the majestic image of Mt Fuji looming in the background The title of the piece, “1 Fuji, 2 Hawks, 3 Eggplants,” creates an unexpected landscape for the viewer What is the relationship between Fuji-san, the hawks, and the eggplants? Why does the title of the work not correspond to the number of depicted images?

The mystery of these three auspicious symbols is revealed by “初夢” (Hatsuyume, lit the first dream), the first dream of the new year Traditionally, the contents of such a dream are believed to foretell the luck of the dreamer in the ensuing year Since the Edo period, it has been considered particularly good luck to dream about Mount Fuji, a hawk, and an eggplant

This superstition in Japan is remembered in the form “Ichi-Fuji, ni-taka, san-nasubi 富⼠、⼆ 鷹、三茄⼦; 1 Fuji, 2 Hawk, 3 Eggplant,” which is the title of this painting Arakawa has invoked good luck through this playful landscape of a dream

The scroll is signed ⽃出庵 Tosyutuan* and bears Arakawa Toyozo’s seal on the left

Arakawa Toyozo 荒川 豊蔵 (1894-1985)

Hanging scroll with image of a Mt. Fuji, two eagles and three eggplants 富士二鷹三茄子, 1981

With signed wood box Japanese paper with ink

Image: (h) 66 0 × (w) 43 1 cm

Mount: (h) 152 4 × (w) 62 2 cm

*Arakawa Toyozo had begun using an alternative "Literati" or artist name Tosyutuan ⽃出庵 after 1972

Arakawa Toyozo 荒川 豊蔵 (1894-1985)

Shino tea bowl with bamboo shoot drawing 志野筍絵茶碗 銘 随縁, 1961, stoneware with Shino glaze (h) 10 x (diameter) 11.5 cm, with signed wood box

Image: © Arakawa Toyozo Museum Collections 荒川豊蔵資料館, Gifu, Japan

The tea bowl drawn on this hanging scroll most likely describes a particular Shino tea bowl (pictured left), which was created in the same year, 1961 from the Arakawa Toyozo Museum Collection in Gifu, Japan

The inscription to the left of the tea bowl reads:

茶碗画賛志野筍絵茶碗銘随縁

Chawan gasan Shino takenoko e chawan mei zui en

This inscription reflects Arakawa's deep reverence for a tea bowl and its fragments that he discovered during a 1961 research trip to Mino During this visit, he encountered a tea bowl adorned with bamboo shoot designs from the Momoyama period, an experience that inspired him to embark on a journey to revitalize the traditional Shino glazing techniques

This journey led Arakawa’s eventual designation as Living National Treasure for his exceptional, historically focused and technically skilled work in modernizing Momoyama techniques of making Shino ware

Arakawa Toyozo 荒川 豊蔵 (1894-1985)

Hanging scroll with tea bowl drawing 画 賛茶碗, c. 1961

With signed wood box, Japanese paper with ink

Image: (h) 30.2 × (w) 43.9 cm

Mount: (h) 116.8 × (w) 47.7 cm

On the left side of this painting, the words “千年 緑” (meaning "evergreen") are revealed through a light ink wash applied with an especially dry brush These words subtly reference the pine tree, whose trunk ascends throughout the composition

Rendered in a breathy, ephemeral ink wash so delicate that they could be mistaken for falling leaves or an extension of the tree’s branches, the words enhance the ethereal quality of the scene Despite their delicate appearance, the vivacity of each brushstroke imbues the painting with energy and power

The effect of a dry brush evokes rippling movement, with the branches and leaves appearing to quiver in the wind and the trunk swaying where it narrows The ink is most dense at the base of the trunk, emphasizing its strength and stability

This is a classic and modern example of Arakawa Toyozo’s Suibokuga ⽔墨畵, or ink wash painting

On the lower right, the dated inscription reads: 昭 和(52年)丁⺒ (ひのとみ) Showa 52 (1977)

It is signed with Arakawa Toyozo's alternative name ⽃出庵 Tosyutuan*

*Arakawa Toyozo had begun using an alternative "Literati" or artist name Tosyutuan ⽃出庵 after 1972

Arakawa Toyozo 荒川豊蔵 (1894-1985)

Hanging scroll with evergreen tree 千年緑, 1977

With signed wood box, Japanese paper with ink (h) 144 × (w) 26 cm

© Dai Ichi Arts, Ltd , 2024

Authorship: Beatrice Chang, Yoshitsugu Nagano, Mark Tyson, Kristie Lui

Catalog production: Haruka Miyazaki 宮崎晴⾹, Yoriko Kuzumi 久住依⼦

Photography: Yoriko Kuzumi 久住依⼦

Editorial & catalog design: Kristie Lui