professor doctor jd pretorius

doctorum et litterature et philosophie historia studii

magister atrium notitia consilio

honoribus es historia

baccalaureus artium denique artes altius educationem diploma mmxxi

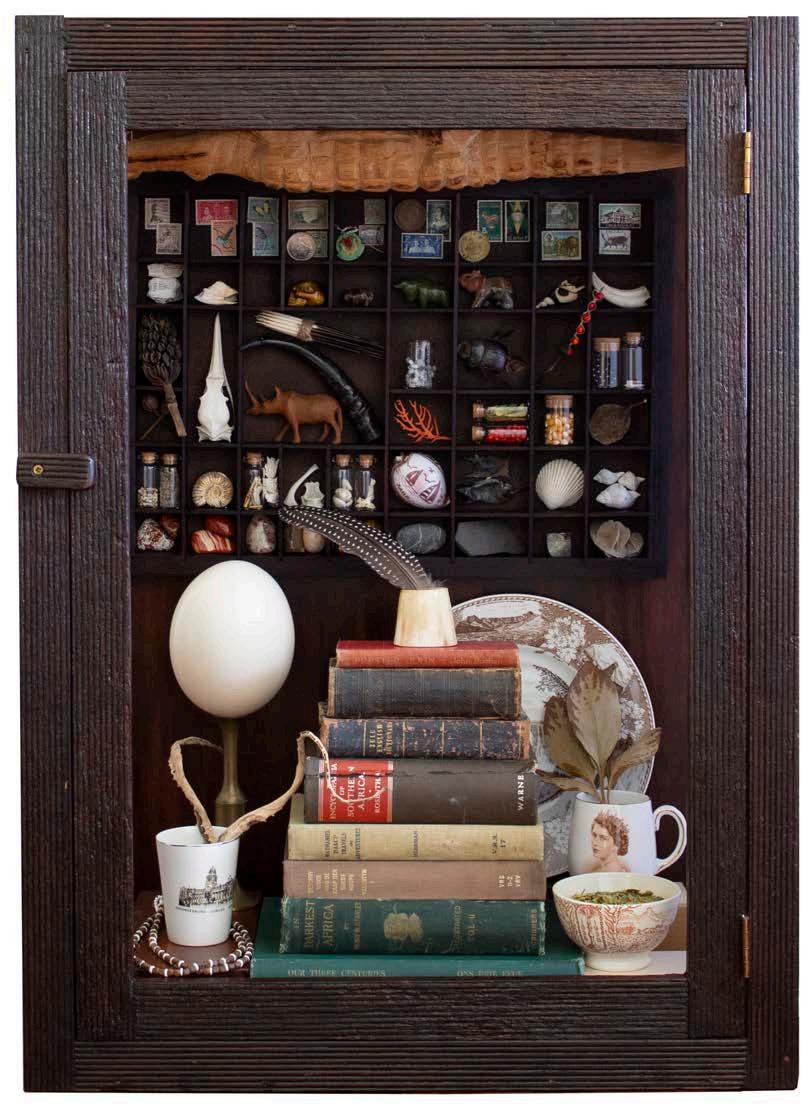

This work is the result of a self-initiated research-led practice project which was driven by my interest in the link between colonialism and cabinets of curiosities. In particular, I explored how a cabinet of curiosities can be used to tell stories informed by postcolonial theory that confront colonial narratives in the contemporary South African context.

Hazel and Dean (2009:7) use the term “research-led practice” alongside the better known and more frequently used term “practice-led research,” as it more overtly asserts that creative work can result from scholarly research. My textual research, which I frame as Design History, spans across multiple disciplines, including historical-, visual-, material- and cultural studies and I am intrigued by the question of how this research, which usually results in textual output in accredited journals, can inform and be extended into my creative practice. This work is the result of that exploration.

The work consists of three components. The first is a physical cabinet exhibited in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture (FADA) Gallery in August 2021 at the University of Johannesburg. The second is a catalogue which accompanies the cabinet and the third is a conference paper delivered at the South African Visual

Arts Historian’s (SAVAH) Annual Conference at the end of September 2021.

The physical cabinet is inspired by the cabinets of curiosities which first appeared in Europe during the Renaissance. A cabinet could refer to a piece of furniture, but also a room, or series of rooms filled with natural and humanmade objects, referred to as naturalia and artificialia respectively. The development of cabinets of curiosities was closely linked to a time of increased trade and travel (Zytaruk 2011:2, Berry 2018:20) and objects were brought back from voyages of discovery to these “new worlds” (Mauriès 2011:12). Inside my cabinet a wooden crocodile sculpture suspended belly up from the roof is a nod to the practice of suspending stuffed crocodiles from cabinet ceilings, as in the famous cabinet of Ferrante Imperato (1525-1625) which is depicted in an engraving (Zytaruk 2011:3).

Cabinets of curiosities are generally considered to be forerunners of the development of modern museums (Bann 1995:15). While cabinets of curiosities aimed at creating “access to the unknown and the magical,” museums offered “a rational and positivistic view of the world” (Brzezińska-Winkiel 2020:347). Museums developed on the basis of scientific

principles and used taxonomies, such as the one developed by Linnaeus, for categorization (Ross 2019:1087). This practice was driven by Enlightenment thinking. Collections in eighteenth century museums were “classified and compartmentalized … each specimen worked in hierarchical relationships to others” thereby moving from the wonder of cabinets of curiosities, to the hierarchy of modern museums (Barrett 2012:65-66).

The printer’s tray mounted on the back panel of my cabinet refers to the development of scientific thinking and contains a number of objects arranged in a hierarchical order from bottom to top. At the base is earth, minerals and water creatures, followed by land and sky animals, plants and then human-made objects, each boxed into its own, separate space. One logical conclusion of such thinking is depicted at the apex of the hierarchy through stamps and coins: the development of the nation state. However, as evidenced in the stamps representing names of countries that no longer exist, such divisions are human-made, they are not permanent and subject to change.

and an adventure story. This indicates some of the sources through which knowledge of Southern Africa was constructed and disseminated during the colonial period. Surrounding the books are objects arranged on the floor and mounted on the back of the cabinet relating to foundational myths of Southern Africa.

“I explored how a cabinet of curiosities can be used to tell stories informed by postcolonial theory that confront colonial narratives in the contemporary South African context”

The objects displayed in the cabinet were bought, mainly from second-hand shops and at junk sales, found, or received as gifts. Most objects, including the display cabinet and printer’s tray, were acquired specifically for the cabinet during the time period from December 2020 to July 2021. Some objects are from my personal collection obtained on trips or bought previously in Johannesburg, others were gathered on walks through my neighbourhood, the beach and on a farm. My choice of objects was informed by my research into cabinets of curiosities, the history of Southern Africa and Postcolonial theory.

Stacked up from the bottom of the cabinet is a history book, three travelogues, and an encyclopedia dealing with Southern Africa, the first Zulu-English dictionary ever printed, the Bible

The second component is a catalogue that provides an inventory of some of the objects contained in the cabinet. In the catalogue the objects are classified into five categories: Animalia, Artificialia, Mineralia, Botanica and Bibliotheca. The Animalia category contains animal remains, including bones, feathers, horns,

quills and shells. Artificialia refers to human made objects such as ornaments, coins, stamps and commemorative ware. Stones and earth constitute the Mineralia section while Botanica includes seed and plant specimens. Bibliotheca provides information on some of the authors whose books are included in the cabinet. Each object is represented in a clear photograph and accompanied by information on its date and place of origin and its size in height, width and depth is provided. Information is given on when I acquired the object, from where, and at what cost, or whether it was free or a gift. Where information is not available, often through my inability to recall the details, it is noted as such.

Accompanying most objects is a description derived from the fourth edition of Eric Rosenthal’s Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa (1967) published by Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd. located in London and New York. The encyclopedia entry is quoted verbatim and either describes the object directly, if such an entry exists, or offers a description of an aspect related to the object, its place of origin or name. Combining the encyclopedia entries with objects allows for consideration of how our understanding of the world is mediated through language.

“The cabinet allows for reflection on the past of South Africa from our current historical position”

In the foreword to the encyclopaedia Rosenthal (1967:v) is at pains to explain that: “[f] or the fourth time since 1961 the insistent public demand has made necessary the issue of a new edition of the Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa.

The policy of a strictly factual approach and avoiding polemics has obviously been appreciated and continues to be maintained.” Rosenthal here invokes the common perception that encyclopedias are objective, scientific texts and that knowledge is neutral and value free. However, a reading of the encyclopaedia shows how the commonplace biases and prejudices of the time are reflected in some of the entries. People, and even plants, are labelled with names considered extremely derogatory today (Rosenthal 1967:30, 82, 278) and indicates how racial prejudice is coded into everyday language. Descriptions of racial groups are far from “factual” and value judgements and hierarchical descriptors such as “primitive” and “curious” (Rosenthal 1967:87) are drawn on to create a pejorative impression of the Other. The insistence on obsessively providing statistics on the number of people belonging to the different racial groups codified into law by the apartheid government is particularly striking (Rosenthal 1967:341, 447, 524). The constant references to the economic value of natural and human resources unveils the predominantly fiscal interest in Southern Africa held by the audience of the encyclopaedia. Factual errors are also present, as is evident in the entry on Mandela which states that he was sentenced to life imprisonment on Robben Island for pleading “guilty to an attempt to start a civil war and insurrection” (Rosenthal 1967:338). Of importance also, are

the omissions and silences in the encyclopaedia, and its entries provide a view into one particular perspective on the status of knowledge about Southern Africa by the 1960s.

The 1960s was a time period during which decolonization in Africa had been accelerating and many independent postcolonial nation states came into being. However, in Southern Africa colonial rulers clung onto power in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Namibia and Mozambique. During this time the apartheid government started implementing their scheme of creating “independent homelands” into which to separate black South Africans according to their “tribal” affiliation. Transkei was granted “self-government” in 1964 and “independence” would follow in 1976. Three other “homelands” would eventually be granted “independence”, Bophuthatswana (1977), Venda (1979) and Ciskei (1981), and six others “self-government”.

National symbols, including flags, coats of arms and stamps were designed to support the construction of these nation states. While these states no longer exist today, the effects of such social engineering remain alive in South African society, the most recent example being the extreme unrests following the incarceration of former president Jacob Zuma. The cabinet allows for reflection on the past of South Africa from our current historical position. While this past is in many aspects a “foreign country”—the material reminders of which might today seem so peculiar that it is best suited for storage in cabinets of curiosities— the legacy of colonialism and apartheid lives on in the present. This past cannot be denied, but must be confronted and reflected on to lead to the development of new stories which will replace the divisive narratives of the past. Deirdre Pretorius, July 2021, Jhb.

Sources Consulted

Bann, S. 1995. Shrines, Curiosities and the Rhetoric of Display, in, Visual Display: Culture Beyond Appearances, edited by L. Cooke & P. Wollen. The New Press: New York:15-29.

Berry, S. 2018. Marianne Moore’s Cabinets of Curiosity. Journal of Modern Literature. 41(3):18-38.

Brzezińska-Winkiel, A. 2020. Jan Švankmajer’s Kunstkammer: Every thing means everything. Journal of Education, Culture and Society. 11(2):343-352.

Mauriès, P. 2011. Cabinets of Curiosity. London: Thames & Hudson.

Rosenthal, E. (ed.) 1967. Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa. Fourth edition. London & New York: Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd.

Ross, AS. 2019. Recycling embryos: Old animal specimens in new museums, 1660-1840. Journal of Social History. 52(4):1087-1109.

Smith, H. & Dean, RT. 2009. Introduction: Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice – Towards the Iterative Cyclic Web 1, in Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts, edited by H. Smith & RT. Dean. Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh:1-38.

Zytaruk, M. 2011. Cabinets of Curiosities and the organization of knowledge. University of Toronto Quarterly. 80(1):1-23.

“The sedimentary rocks and other deposits of Southern Africa often contain the fossilised remains of the hard parts of animals and plants. These date from the following periods of the earth’s history: the Devonian, Permian, Triassic, Cretaceous and Pleistocene.

Devonian and Cretaceous fossils are almost exclusively of non-vertebrate marine forms (trilobites, molluscs, shells, etc.) and, as they are well known from other parts of the world, do not deserve the same attention as those of the Permo-Triassic and Pleistocene” (Rosenthal 1967:187).

Perisphinctoidea

Date Middle-Late Jurassic

Origin Tulear, Madgascar

Size 34mm x 40mm x 14mm

Acquired March 2021

From Rosebank Market, Jhb

Price R50

“Baboon, Cape (Papio porcarius). Also known to H********* as Chacma; Amazosa, Infene; Zulus and Swazis, Imfena; Basuto Tshweni. Found throughout South Africa to the Zambesi River, in bare, rocky, mountainous country. Feeds on wild fruit, insects, berries, young leaves and sap from certain trees. When driven by hunger, will raid orchards and vegetable gardens. Chief weapons of defence are extremely powerful jaw and well-developed canine teeth. As member of a troop is a formidable fighter. Yellow brown body, face smoky-black” (Rosenthal 1967:30).

Date Undated

Papio ursinus

Origin Nieu-Be thesda, Karoo

Size 20mm x 10mm x 6mm

Acquired April 2021

From Craft Brewery owner

Price Free

“Coral Fish. Small tropical and subtropical East Coast fish, brightly coloured, having, unlike most fish, one nostril only on each side and deep compressed bodies, like the Butterfly fish (q.v.). Found among coral reefs and along rocky shores. There are many varieties, including the Angel Fish (q.v.).”

(Rosenthal 1967:16)

Cnidaria

Date Undated

Origin Jeffreys Bay

Size 4mm x 38mm x 5mm

Acquired Be tween 2006-2016

From Jeffreys Bay Beach

Price Free

“Dung Roller. Beetle so called on account of its habit of making balls of dung in which to deposit its eggs. These are pushed to a suitable place and covered with sand. It belongs to the Scarab family. See INSECTS” (Rosenthal 1967:160).

Scarabaeidae

Date c2018-2021

Origin Bloemfontein

Size 6mm x 30mm x 12mm

Acquired April 2021

From Origin

Price Free

“Gannet or Malagas (family Sulidae). Semi-oceanic birds, much less bound to the shore than gulls, terns or cormorants. They feed by plunging headlong from a height on to fish swimming near the surface, and from a distance appear gleaming white. Are chief inhabitants of the Cape Guano Islands. See DUIKER and BIRDS” (Rosenthal 1967:199).

Gannet Skull

Sulidae

Date c. 2006-2016

Origin Jeffreys Bay

Size 20mm x 38mm x 26mm

Aquired Be tween 2001-2016

From Origin

Price Free

“Guinea fowl (family Phasianidae). Common game bird found in thick bush, from Eastern Cape Province northwards. The nearly-bare neck and plump, speckled body are well known. A wary bird, running in flocks and flying well. Scratches for its food of grubs, roots and insects, in bush country. The Crested Guinea Fowl is a tropical dweller of Natal and Kruger Park. See FRANCOLIN” (Rosenthal 1967:229).

Phasianidae

Date Undated

Origin Sneeuberg, Karoo

Size 215mm x 50mm

Acquired April 2021

From Origin

Price Free

“Ostrich (Struthio camelus). Indigenous bird connected with an important industry. Of the five local varieties, the predominant one is the Southern Ostrich. From the earliest days of white settlement, ostriches were hunted for their plumes, for the European market. By 1860 the number had been so much reduced, despite their natural fleetness of foot, that several farmers attempted their domestication. The earliest efforts were recorded about 1853. In 1865 80 birds were in captivity and the exports came to £17,522 lb., worth 65,736. From then on the industry grew rapidly, being concentrated in the vicinity of Graaff-Reinet and the Eastern Province. Profits were immense and prices rose until over £1,000 was paid for a pair of breeding birds. The first great boom began in 1880 and lasted until about 1885. An even greater one set in from 1910 to 1913, when from 746,736 birds, nearly all in the Cape, some £ 3,000,000 worth of feathers were exported. The onset of World War I caused a crash, both in prices and production, from which the industry has never recovered. Most of the birds were slaughtered to produce leather instead of feathers. In recent times there has been a gradual revival, but there are only about 50,000 birds left to produce less than 100,000 lb. of feathers yearly. Nearly all of these birds are in the Oudtshoorn district. The development of the industry has been largely responsible for the intensive farming practice in this part of the world. The ostrich is peculiar in that its flight apparatus (wings, keeled breastbone and muscles) IS SO RUDIMENTARY AS

TO HAVE DISAPEARED. The breastbone, for example, is flat, unlike that of such other birds as flightless pigeons and parrots. To compensate, the ostrich has developed a speed and strength adequate for wild South African life. Feathers are drawn only from the males. A few wild birds survive in the Kalahari and Bushveld. See BIRDS” (Rosenthal 1967:400-401).

“Calvinia. Town in North-Western Cape Province at the foot of the Hantam mountains. Founded in 1851 to commemorate John Calvin, the great reformer. Important sheep district. Wheat is grown near the Zak River. Population: 5,189, including 1,860 Whites” (Rosenthal 1967:92).

Struthio Camelus

Date Unknown

Origin Calvinia

Size 40mm x 366mm

Acquired December 2020

From hantam huis & restaurant

Price R5

“Porcupine (Hystrix africao-australis). Rodent known for its characteristic defensive quills. Upon being driven into the flesh of attackers, they are difficult to remove. Porcupines live on vegetable food and do considerable damage to crops, though they also destroy certain poisonous plants which are a danger to cattle. They are about 28 inches long, live in burrows and are common to most parts of Southern Africa. See MAMMALS” (Rosenthal 1967:423).

Hystrix Africao-Australis

Date Undated

Origin Unknown

Size 34mm x 20mm x 18mm

Acquired March 2021

From Rosebank Market, Jhb

Price R30

“Sharks. Many varieties, all differing from ordinary fish in having cartilage in place of bones; skin covered, not with scales, but with rough denticles; teeth usually numerous; 5 to 7 gill-slits on each side; cigar-shaped body and high upper lobe of tail-fin. Length ranges between 5 and 50 feet. Most species are viviparous but the Zebra Shark (Stegostoma fasceatum) lays a few large eggs, each enclosed in a horny case (sometimes found along the sea margin). The young are born or hatched looking like the adult. Sharks can be recognized from afar by the high tail-fin and by the fact that, because the mouth is greatly under-hung, they turn over to attack and expose their light underside. Although seen scavenging round Cape harbours, they are much more plentiful off the Natal coast. The majority are dangerous. Authenticated attacks on man have mostly been traced to the 5-foot Durban Grey Shark (Carcharinus melanopterus) and the larger Black Fin Shark (C. limoatus) rather than to the 30-40-foot man-eater (Cachasodon carcharias). The 15-foot Tiger Shark (Galeocerdo articus) is aggressive but in the main an offal-eater. A 289-pounder has been caught in Natal with a rod and line.

Of the harmless species, the 40-foot Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus) appears to be a Cape summer visitor, which has been seen surfacing off Simonstown

and Hout Bay. Its numerous teeth are small and it lives on tiny organisms strained by its long gill-rakers. Very similar to this and the largest known is the 50 foot Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus). The first South African specimen, washed up in Table Bay in 1829, is preserved in the Paris Museum. Cape Town Museum contains a 20-foot specimen found in Noordhoek in 1934.

The shark of economic importance to South Africa is the 6-foot Vaalhaai (Galerhinus galeus), hunted for its liver oil. In Australia the fins are dried and exported to China for shark fin soup. The skin is sold for smoothing wood, for leather and for covering ornamental boxes. See Marine resources” (Rosenthal 1967:491).

Acquired Memory Fails

From Memory Fails

Price Memory Fails

Date Undated

Origin Unknown

Size 11mm x 17mm x 2mm

Euselachii

Date Undated

Origin Unknown

Size 62mm x 21mm x 7mm 71mm x 32mm x 6mm

Acquired March 2021

From Bounty Hunters, Melville

Price Less than R10

“Inhaca (also known as Inyack). Island in Delagoa Bay, 8 miles long and 3 miles wide. Chosen for its isolation from hostile natives as the earliest Portuguese settlement in Delagoa Bay. Today it is used by fishermen and also as a site for a Biological Research Station, operated by the University of the Witwatersrand in conjunction with the Portuguese authorities” (Rosenthal 1967:260).

Cardiidae

Date Unknown

Origin Mozambique

Size 51mm x 48mm

Acquired 2014

From Inhaca Island, Mozambique

Price Free

“Eland’s Bay. Fishing Harbour on the Cape West Coast, north of St. Helena Bay” (Rosenthal 1967:169).

Date Undated

Origin Near Elands Bay Cave

Size 29mm x 45mm x 22mm Largest

Acquired December 2020

From Origin

Price Free

“Once the most common of all Southern African antelopes, now limited mainly to a few reserves. They derive their name from their habit of characteristic display-leaping or ‘pronking’ (q.v.). At one time vast herds stampeded through the veld over the Karroo, even into villages, doing great damage. Today they can be shot only under authority. The flesh makes very good eating. Springbok are particularly graceful and both sexes carry small horns. The reddish-brown of the back is separated by a dark line from the pure white of the underparts. Height about 30 inches, to the shoulder” (Rosenthal 1967:530).

Springbok Horn

Antidorcas Marsupialis

Date Undated

Origin Unknown

Size 49mm x 24mm x 26mm

Acquired March 2021

From Rosebank Market, Jhb

Price R30

“Wart Hog (Phacochaerus aethiopicus). Wild animal found over a large part of Southern Africa north of the Orange River, including Natal, the Kruger National Park, Rhodesia, Bechuanaland and Mozambique. Unlike the Bush Pig (q.v.) it prefers comparatively thinly-grown areas, but also likes muddy ground. It is largely nocturnal in habit and lives in holes in the ground. Normally the Wart Hog grows to a height of 2 feet 6 inches. It takes its name from large growths between the tusks and below the eyes. Can be dangerous when hunted. The meat makes moderately good eating” (Rosenthal 1967:606).

Phacochoerus africanus

Date Undated

Origin Unknown

Size 55mm x 22mm x 12mm

Acquired March 2021

From Rosebank Market, Jhb

Price R30

“Zebra (Equus zebra). Once extremely common in South Africa, but now mainly preserved in National Parks. There are several species, most of them varying only in the de-tails of their marking, and all difficult to tame. Of these the Mountain Zebra, only about 4 feet high, has no fore-lock and is more reddish in colour” (Rosenthal 1967:635).

Date Undated

Origin Sneeuberg, Karoo

Size 35mm x 22mm x 30mm

Acquired April 2021

From Origin

Price Free

“Afrikander Cattle. Hardy breed of South African cattle, known to the early settlers and already mentioned in the 1850s. Noted for their large horns and resistance to climatic conditions. Successful experiments in introducing Afrikander cattle to the dry regions of the United States particularly Texas, were carried out in in 1930 and after. Now recognized as a breed peculiar to South Africa” (Rosenthal 1967:169-10).

Date Undated

Origin Unknown

Size 28mm x 55mm x 19mm

Acquired April 2021

From Indoor Market, Tyrone Ave

Price R10

No entry in Rosenthal (1967).

Crocodylus niloticus

Date Unknown

Origin Unknown

Size 60mm x 540mm x 93mm

Acquired April 2021

From Bounty Hunters, Melville

Price R50

“Elephant. Largest African land mammal. First found in the environs of Table Bay, but gradually driven north, although a few survive in the Tsitsikama Forest and in the Addo National Park (q.v.). A number have been preserved in the Kruger National Park, in Rhodesia and in Mozambique. The African elephant is larger than the Asiatic and has conspicuously large ears. The animals reach a height of nearly 11 feet, and reports have been received of specimens of over 12 feet. The tusks of African elephants attain enormous sizes, one of the largest on record being 11 feet 5 ½ inches in length, over 1 ½ feet in circumference and weighing close on 300 lb. Elephants are not aggressive but when aroused can do great damage. Elephant hunting is only allowed under control in Rhodesia, and not at all in the Republic. Elephants found at Addo and in the Tsitsikama Forest differ from the normal African type and are considered to be a special sub-variety. See MAMMALS” (Rosenthal 1967:169-170).

Elephas maximus

Date Undated

Origin Unknown

Size 6mm x 55mm x 25mm

Acquired March 2021

From Rosebank Market, Jhb

Price R25

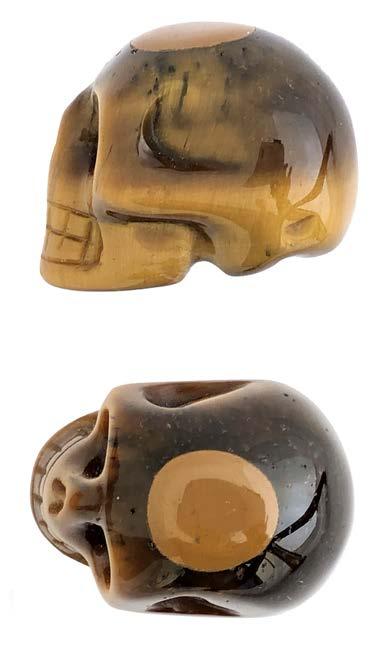

No entry in Rosenthal (1967).

Homo sapiens

Date Undated

Origin Unknown

Size 25mm x 35mm x 26mm

Acquired March 2021

From Ms. C. Swanepoel

Price Gift

“Rhinoceros. Largest land mammal in Southern Africa after the elephant. There are two species. The Black Rhinoceros (R. bicornis), once found all over Southern Africa, is now confined to the Bushveld, the Eastern Transvaal and Rhodesia, while the White Rhinoceros (R. simus), never seen South of the Orange River, is now only found in the Hluhluwe (q.v.) and other National Parks, in Zululand and in certain corners of Rhodesia. At one time believed to be extinct, it was rediscovered towards the end of the 19th century. The Black Rhinoceros stands about 5 feet at the shoulder, the body measuring about 10 feet round. The occasional White Rhinoceros has been found nearly 7 feet at the shoulder, and close on 14 feet round. Both types suffer from poor eyesight and are low in intelligence, but have a keen sense of smell and hearing. The White Rhinoceros has a straight, not a prehensile upper lip. Both have two horns, and cases have been reported of the larger front one reaching nearly 5 feet. The last Black Rhinoceros in the Cape was shot not far from Port Elizabeth in 1853” (Rosenthal 1967:450-451).

Rhinocerotidae

Date Undated

Origin Unknown

Size 70mm x 95mm x 26mm

Acquired March 2021

From Rosebank Market, Jhb

Price R30

Country: S outh Africa

King: George VI (1936-1952)

Type: Standard circulation coin

Years: 1937-1947

Value: 1 Penny = 1/12 Shilling = 1/240 Pound (1/240)

Currency: Pound (1825-1961)

Composition: Copper

Weight: 9.48 g

Diameter: 31.0 mm

Thickness: 2.04 mm

Shape: Round

Orientation: Medal alignment

Demonetized: 03-31-1961 Obverse:

Portrait of George VI, King of United Kingdom, Great Britain, Northern Ireland and other dominions of the Commonwealth from 1936 to 1952, facing left

Lettering: Georgivs vi Rex Imperator

Translation: George vi King Emperor

Engraver: Thomas Humphrey Paget

Reverse: A ship, ‘Dromedaris’, sailing to right, a legend in English and Afrikaans either side, with date above and denomination below

Lettering: S outh Africa 1937 South Africa

Engraver: George Kruger Gray

Edge: Smooth

Comments: The Dromedaris is one of the three vessels which brought Jan van Riebeeck and his small group of settlers to South Africa from Holland in 1652 in order to establish a refreshment station on behalf of the Dutch East India Company.

https://en.numista.com/catalogue/pieces3202.html

Date 1937

Origin South Africa

Size See Information on Left

Acquired Memory Fails

From Memory Fails

Price Memory Fails

Country: South Africa

Period: Republic of South Africa (1961-date)

Type: Standard circulation coin

Years: 1961-1964

Value: 1 Cent (0.01 ZAR)

Currency: Rand (1961-date)

Composition: Brass

Weight: 9.42 g

Diameter: 31.0 mm

Thickness: 2.0 mm

Shape: Round

Demonetized: Yes

Obverse: Portrait of Jan van Riebeeck (1619-1677), Dutch colonial administrator and founder of Cape Town.

The motto in Afrikaans and in English : “Power through Unity”

Lettering: Eendrag Maak Mag * Unity Is Strength

Designer: Willie Myburg

Reverse: Covered wagon

Lettering: South Africa·1963·AuidAfrika

Designer: Hilda Mason

Edge: Plain

Mint: Pretoria, South Africa

Comments: There is a rare 1961 variety (Hern#R5) with full ground cover under the wagon on the reverse. Hern estimates the original mintage to be in the region of 80 but states that only 12 are known.

https://en.numista.com/catalogue/pieces2879.html