PUBLISHER

António Cunha Vaz

D IRECTORA EXECUTIVA

Sofia Arnaud

D IRECTOR DE ARTE

Miguel Mascarenhas

CONSELHEIRO

EDITORIAL

Diogo Belford

REDACÇÃO

Ana Valado, Bruno Rosa

COLABORAM NESTA

EDIÇÃO

André Veríssimo, Blandina

Costa, Filipe Santos Costa, João Almada, Luís Eusébio, Neil Bennett, Quingila Hebo

P UBLICIDADE

Telf.: 210 120 600

I MPRESSÃO

Soartes Artes Gráficas, Lda.

Rua A. Cavaco - Carregado Park, Fracção J

Lugar da Torre, 2580-512

Carregado

PROPRIETÁRIO E EDITOR

Cunha Vaz & Associados –Consultores em Comunicação, SA

NIF 506 567 559

D ETENTORES DE 5%

OU MAIS DO CAPITAL

DA EMPRESA

António Cunha Vaz

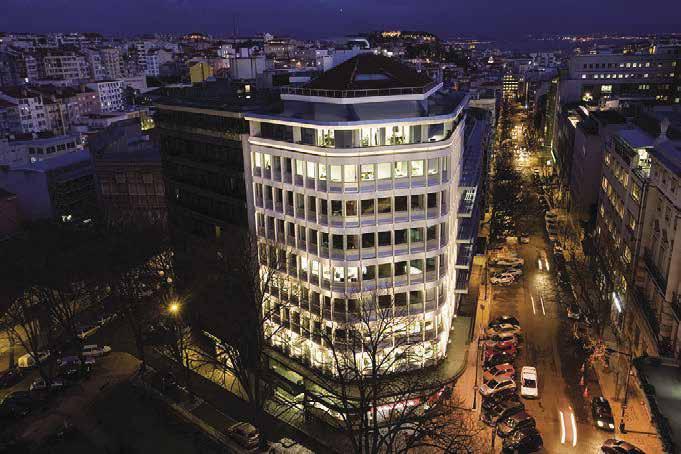

SEDE DO EDITOR

E DE REDACÇÃO

Av. da Liberdade, 144, 6º Dto 1250-146 Lisboa

C RC LISBOA

13538-01

R EGISTO ERC

124 353

D EPÓSITO LEGAL 320943/10

SUMÁRIO | CONTENTS

ESTATUTO EDITORIAL

EDITORIAL

OPINIÃO | OPINION

Neil Bennett, Co-CEO H/Advisors

AMO and H/Advisors – A short history

DESTAQUE | FEATURED

Conferências com chancela CV&A | The CV&A conferences

PORTUGAL

20 Anos depois, estamos assim tão diferentes? | 20 years later, are we really so different?

ENTREVISTA | INTERVIEW

A conversation with Henry Kissinger

THE ECONOMIST

Inflation and rising demands on governments are changing economic policy

PREVISÕES | FORECASTS

O mundo por maus caminhos | The world on the wrong path

ÁFRICA | AFRICA

ANGOLA | ANGOLA

Um país na flor da idade | A young but swiftly maturing country

MOÇAMBIQUE | MOZAMBIQUE

Uma evolução notável e potencial ainda por concretizar | Notable growth and still with potential to achieve

AMÉRICAS | AMERICAS

BRASIL | BRAZIL

Bruno Rosa, PRÉMIO

As idas e vindas da economia brasileira nos últimos 20 anos | The comings and goings of the brazilian economy over the last two decades

ÁSIA | ASIA

JAPÃO | JAPAN

Filipe Santos Costa, jornalista | journalist

www.revistapremio.pt/estatuto

Tokyo connection

P ERIODICIDADE Trimestral T IRAGEM 3500 Exemplares 5 10 12 20 34 54 56 64 74 80 86 R EV I ST A C O R P O R AT IV A D A CV & A

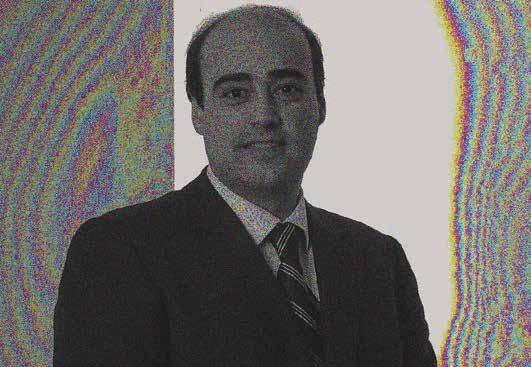

ANTÓNIO CUNHA VAZ, PRESIDENTE DA CV&A CHAIRMAN AT CV&A

Construindo o futuro

Building the future

ACunha Vaz & Associados, também conhecida como CV&A, celebra o seu 20º aniversário no dia 15 de Junho de 2023. Durante as últimas duas décadas, a CV&A estabeleceu-se como uma empresa líder em consultoria de comunicação, especialmente focada em consultoria de comunicação institucional e assuntos públicos em Portugal, com presença na África de língua portuguesa e Brasil. Desde a sua criação, a CV&A está na vanguarda da comunicação corporativa e financeira, oferecendo aos clientes consultoria estratégica e soluções inovadoras para navegar em ambientes de negócios complexos, lidando com o mais diverso género de partes interessadas. Fruto do seu compromisso com a excelência, a CV&A tem sido consistentemente reconhecida como um ‘player’ de referência no sector. Ao longo dos anos, a CV&A trabalhou com um vasto leque de clientes, incluindo as maiores empresas nacionais, empresas multinacionais, agências governamentais e ONGs. A sua experiência em gestão de reputação, comunicação de crise e engajamento de partes interessadas ajudou os clientes a atingir os seus objetivos e construir relacionamentos duradouros com os seus ‘stakeholders’. Olhando para o futuro, a CV&A mantém o compromisso de oferecer o mais alto nível de serviço aos seus clientes e expandir a sua presença nos principais mercados. Com uma talentosa equipa de profissionais e um histórico de sucesso, a CV&A está pronta para continuar a sua trajectória de crescimento e causar um impacto positivo no cenário dos negócios por muitos anos. Afinal, a CV&A celebra 20 anos e é com orgulho que lidera o mercado em facturação, lucros

Cunha Vaz & Associados, also known as CV&A, celebrates its 20th anniversary on 15 June 2023. During these two decades, CV&A established itself as a leading communications consultancy, especially focused on institutional relations and public affairs in Portugal, with a presence in Portuguese speaking Africa and Brazil. Ever since launching, CV&A has been in the vanguard of corporate and financial communications, providing its clients with strategic consultancy and innovative solutions to navigate their complex business environments, dealing with the most diverse and different stakeholders. In keeping with its commitment to excellence, CV&A has received consistent recognition as a benchmark reference in the sector.

Over these years, CV&A has worked with a vast range of clients, including the largest national corporations, multinational firms, government agencies and NGOs. Its experience in reputation management, crisis communication and engaging with interested parties helped these clients achieve their objectives and build long lasting relationships with their stakeholders. Looking to the future, CV&A maintains its commitment both to provide the highest level of service to its clients and to expand its presence in key markets. With a talented team of professionals and a track record of success, CV&A is set to continue its trajectory of growth and bring about positive impacts on the business scenario throughout many years to come. After all, CV&A celebrates its 20th anniversary with due pride at being market leader in terms of turnover, profits and EBITDA and with only 32 members of staff.

• In 2022, we recorded over ten million euros in turnover — with only 2.5% of this stemming either from central, regional and local government or from state owned

5

EDITORIAL

e EBITDA, com apenas 32 trabalhadores.

• Em 2022 apresentámos mais de dez milhões de euros de facturação — apenas 2,5% com origem no Estado central, regional, local e empresas públicas — e três milhões de euros de lucro (dos quais 10% são distribuídos aos colaboradores e 5% destinados a donativos à sociedade civil – cultura, desporto e obras sociais).

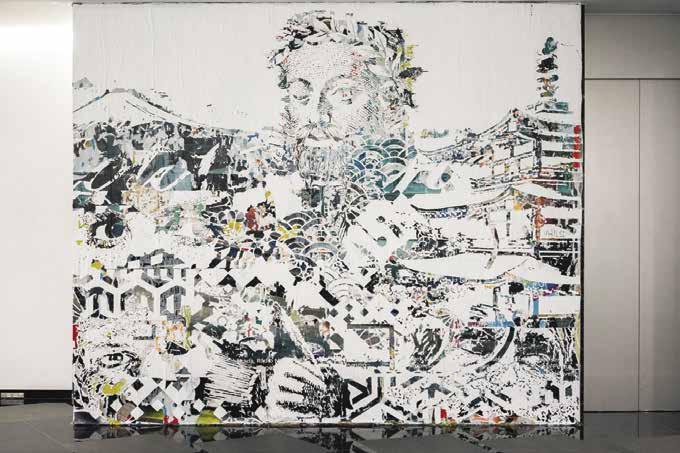

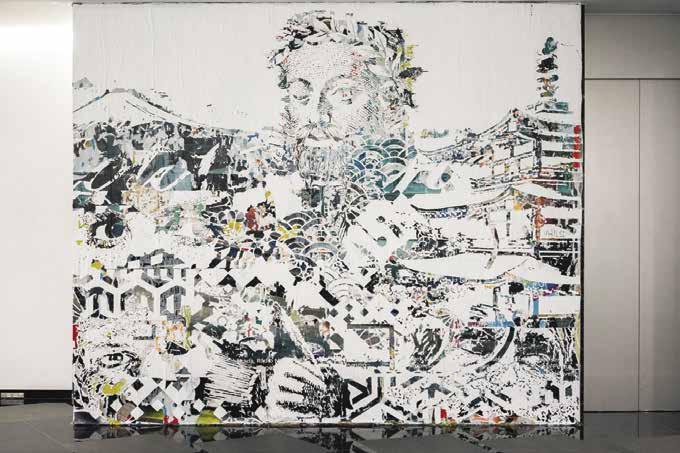

• Na cultura, no desporto e no apoio às crianças do mundo, nenhuma outra empresa do sector investe como a CV&A. Patrocinamos a selecção portuguesa de rugby — LUSITANOS —, e apoiámos em exclusivo a oferta de uma obra de Vhils, Alexandre Farto, à Embaixada de Portugal no Japão. Apoiamos o IPDAL e a Casa da América Latina. Somos membros da UN Global Compact Network e do BCSD Portugal. As crianças sempre foram alvo da nossa atenção. Quando apoiámos a Acreditar, quando equipámos com leitores de DVD a ala pediátrica de Santa Maria, quando fomos patrocinadores da Raríssimas, quando apoiámos projectos dedicados a crianças na Guiné-Bissau e em Angola ficámos sempre gratos por terem deixado que colaborássemos. Nunca o anunciámos. Mas os nossos colaboradores merecem que, nestes vinte anos, se saiba que contribuem para a sociedade em que desenvolvem actividade. No dia deste vigésimo aniversário são as crianças ucranianas refugiadas em Kyiv que merecem o nosso apoio.

• Ainda em 2022, a CV&A tornou-se na primeira consultora certificada pela DGERT para dar formação em comunicação, o que nos permite uma diferenciação da qual nos orgulhamos. Ao mesmo tempo subscrevíamos as plataformas BCSD e UNGNP assegurando medidas para que, também a CV&A, contribuísse de forma sustentável para o desenvolvimento da economia em que se insere.

companies — and three million euros in profit (of which 10% are distributed to staff and 5% donated to civil society entities – culture, sport and social works).

• In culture, in sport and in supporting children around the world, no other company in the sector invests like CV&A. We sponsor the Portuguese rugby team — LUSITANOS —, and exclusively backed the donation of a work of art by Vhils, Alexandre Farto, to the Embassy of Portugal in Japan. We support IPDAL and Casa da América Latina. We are members of both the UN Global Compact Network and BCSD Portugal. Children have always been a target of our intentions. When we supported Acreditar, when providing DVD readers to the pediatric ward at Hospital Santa Maria, when we became patrons of Raríssimas, when providing support for children in Guinea Bissau and Angola, we were always grateful for being allowed to collaborate. We have never advertised this. However, our team deserve, after these twenty years, that there is a record of how they contributed towards society through undertaking these activities. On the date of our twentieth anniversary, it is Ukrainian child refugees in Kyiv who deserve our support.

• Furthermore in 2022, CV&A became the first consultancy to be certified by DGERT to provide communications training, which endows us with the factor for differentiation in which we take due pride. We have simultaneously subscribed to the BCSD and UNGNP platforms ensuring measures that again enable CV&A to make a sustainable contribution to the economic development of its surrounding society.

• Now, under the auspices of the 20th anniversary

6

EDITORIAL

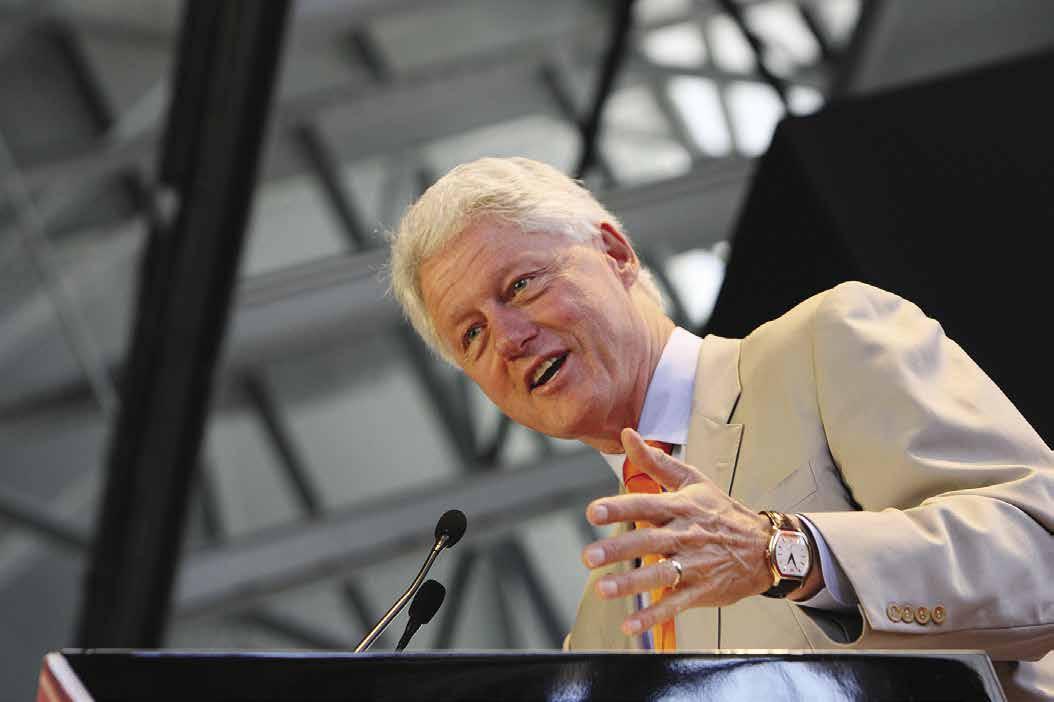

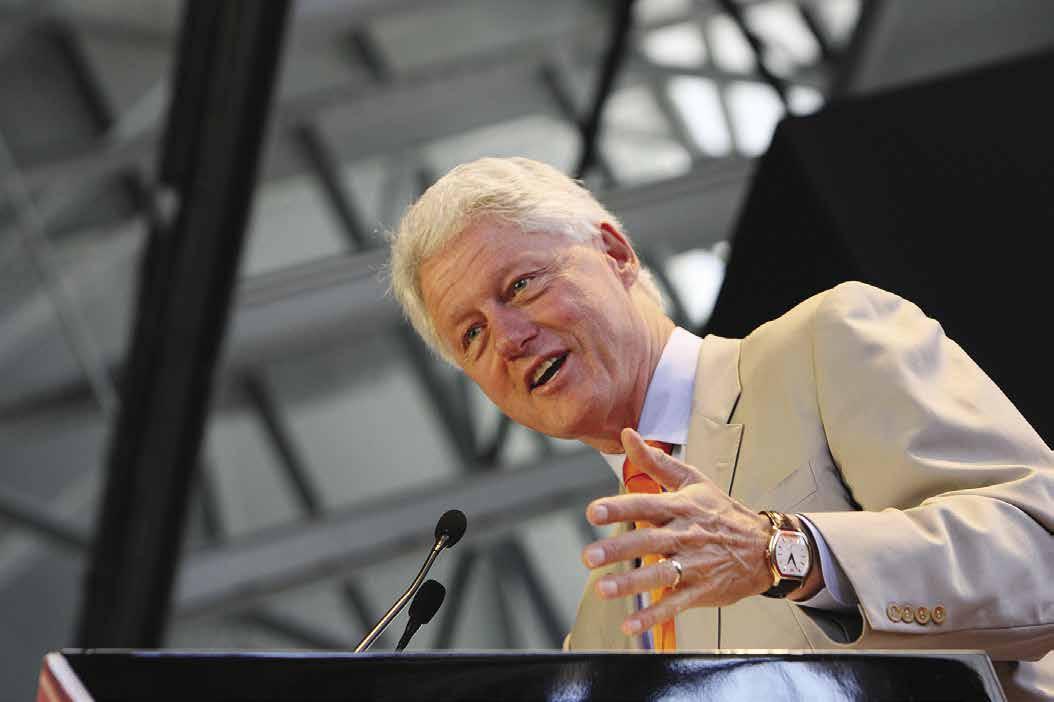

• E agora, no âmbito da comemoração dos 20 anos, a Nova School of Business and Economics e a CV&A anunciaram a criação do programa de formação de executivos “Leadership and Crisis Management”. São duas décadas a contribuir para o sucesso das pessoas, instituições e empresas que nos escolheram ter a seu lado. Este é o ADN da CV&A, escrito pelas suas pessoas, com a ajuda dos seus fornecedores e pensado para servir os seus clientes. As conferências CV&A que agora são retomadas começaram quase no início da actividade da empresa. Sempre pensámos que trazer o pensamento do Mundo ao nosso País era dar seguimento ao que os portugueses de Quinhentos fizeram quando “…por mares nunca dantes navegados…” se aventuraram mar fora e, apesar de tanto “… do seu sal serem lágrimas de Portugal.”, souberam trazer outras culturas até nós, enriquecendo-nos, ao mesmo tempo que deixavam noutras paragens as sementes de um País maior que o seu próprio território. “As Relações Ibéricas e o Contexto do Diálogo Transatlântico”, pelo ex-primeiro-ministro espanhol José Maria Aznar, a Conferência “Leadership: Taking Charge”, com o general norte-americano Colin Powell, seguindo-se “The International Economy Today: Challenges and Opportunities” por John W. Snow., antigo Secretário do Tesouro dos Estados Unidos e a tão em voga palestra “Uma Verdade Inconveniente”, pelo antigo vice-presidente dos Estado Unidos, Al Gore foram marcos de um ciclo que estava para durar. “The Economic Development and the World Peace”, pelo ex-primeiro-ministro britânico Tony Blair, “Embracing our Common Humanity”, pelo antigo presidente dos Estados Unidos, Bill Clinton e “Chanllenging Poverty: The Growth of Microcredit”, por Muhammad Yunus, banqueiro e professor de Economia indiano e pai do micro-crédito, iniciativa que lhe deu a distinção como Prémio Nobel da Paz foram as conferências seguintes. Para além destes, outros brilhantes oradores se seguiram, como Mário Monti, Gerard Schroeder, que falou sobre “A Crise Europeia e as Reformas Necessárias”, David Plouffe, estratega de marketing político norte-americano e o homem que comandou a primeira campanha para a eleição do presidente Barak Obama ou Álvaro Uribe, ex-presidente da Colômbia e visto como o homem que recolocou o País no mapa mundial com o tema “The Rise of the South American Emerging Markets”. Os jornalistas de referência tiveram o seu lugar no ciclo de conferências com “Portugal: ameaça ou Oportunidade”, que teve a participação de Raphael Minder (Herald Tribune), Wolfgang Münchau (Financial Times) e Raul Llores (Folha de São Paulo), quadros de três dos mais prestigiados jornais mundiais. O escritório do Porto, no extraordinário Palácio da Bolsa, sempre com o apoio da Associação Comercial do Porto, foi palco do Primeiro Ciclo das Conferências do Palácio, sob o lema “O Mundo visto do Porto: a política externa de alguns dos grandes protagonistas da diplomacia mundial explicada pelos próprios”. O Segundo Ciclo teria por lema “A Economia vista pelos Empresários” e ambos deram origem a livros que mostram bem a importância de trocar ideias. O III Ciclo das

commemorations, the Nova School of Business and Economics and CV&A are announcing the launch of the executive training program

“Leadership and Crisis Management”.

Two decades of contributing to the success of the people, institutions and companies that choose to have us at their side. This is the very DNA of CV&A, written by its people, with the help of its suppliers and all designed to best serve its clients.

The now-resumed CV&A conferences stretch back right to the earliest activities of the firm. We always strove to bring the thinking of the world to our country and provide continuity to what the Portuguese of the 16th century did when embarking “…for seas never before sailed…” and who adventured overseas and, despite everything, “… from their salt came the tears of Portugal”, knowing how to bring other cultures back to us, enriching ourselves while simultaneously leaving behind the seeds of a country greater than its own territory.

“Iberian Relationships and the Context of the Transatlantic Dialogue”, by the former Spanish Prime Minister José Maria Aznar, the “Leadership: Taking Charge” Conference with the U.S. General Colin Powell, followed by “The International Economy Today: Challenges and Opportunities” with John W. Snow, the former U.S. Secretary of State for the Treasury and the extremely current speech “An Inconvenient Truth” by the former U.S. Vice President, Al Gore were landmarks in a cycle that was set to last. “Economic Development and World Peace”, featured former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, “Embracing our Common Humanity”, with former U.S. President Bill Clinton and “Challenging Poverty: The Growth of Microcredit”, with Muhammad Yunus, the Indian banker, economics professor and the father of micro-credit, an initiative that gained him the Nobel Peace Prize, were the conferences that followed. Furthermore, other brilliant speakers were still to come, including Mário Monti, Gerard Schroeder, who discussed “The European Crisis and the Necessary Reforms”, David Plouffe, the American political marketing strategist and behind the first presidential election campaign of Barak Obama, and Álvaro Uribe, the former President of Colombia and acknowledged as the man who put his country back on the global agenda, speaking on the theme “The Rise of the South American Emerging Markets”. Leading journalists got their opportunity to speak at the conference cycle “Portugal: Threat or Opportunity”, with Raphael Minder (Herald Tribune), Wolfgang Münchau (Financial Times) and Raul Llores (Folha de São Paulo), representing three of the world’s most prestigious newspapers. The Oporto office, in the extraordinary Bolsa Palace, with constant support from the Oporto Commercial Association, was the stage for the First Palace Conference Cycle, on the theme of “The World seen from Oporto: the foreign policies of some of the leading players in world diplomacy explained by themselves”. The Second Cycle approached the theme “The Economy Seen by Corporate Leaders” and both resulted in books that clearly convey the importance of exchanging ideas. The Third Palace Conference Cycle: “The Portuguese Economy

7

EDITORIAL

Conferências do Palácio: “A Economia Portuguesa vista pelos Reguladores” foi, também ele, um sucesso e o IV Ciclo das Conferências do Palácio, “A Economia sob o olhar dos Grandes Economistas”, fechou este período com chave de ouro. Os vinte anos de existência agora comemorados são o espelho dos seus Clientes, Fornecedores e, claro, Colaboradores. O percurso da empresa sempre foi coerente, mas o mercado tem curvas de crescimento e retracção, Portugal e outros mercados em que a empresa opera viveram momentos cíclicos distintos – politica e economicamente – e a saúde financeira hoje existente teve momentos menos bons entre os anos 2012 e 2015. Um negócio com risco mal calculado num mercado externo e as convulsões resultantes da falência de um banco e das empresas com ele, directa ou indirectamente, relacionadas levaram a CV&A a tomar medidas drásticas para poder sobreviver. A empresa contou, então, com o apoio dos Bancos com os quais tinha relação comercial, de alguns fornecedores e, sempre, dos colaboradores. O balanço geral, destes vinte anos que agora celebramos, é de um crescimento forte e sustentado, tanto em número de clientes como no que aos valores fundamentais respeita. A variedade de serviços prestados e a preponderância dos mesmos no volume de negócios foi variando, assim como o peso dos mercados internacionais foi reflectindo a forma como a gestão soube responder, mais ou menos bem, às exigências de cada cultura. Os pesos da comunicação de produto, da comunicação institucional, com a sua vertente financeira, da comunicação política, da mudança para formas e métodos adequados ao mundo digital, foram-se adaptando aos tempos vividos com o surgimento dos assuntos públicos com maior presença nos últimos anos e com tendência a aumentar. A empresa, que iniciou a sua actividade em Lisboa, conta hoje com cerca de 32 pessoas, tem escritórios em Lisboa, no Porto, no Funchal, em Luanda, em Maputo e em São Paulo, sendo membro da rede H/Advisors (a nova marca do Grupo Havas para o sector de Public Relations) e assegurando, assim, serviços em muitos mais países de todos os continentes. Nos vários anos de vida, a empresa esteve presente nas maiores operações financeiras realizadas no país, tanto no ‘buy side’ como no ‘sell side’ – destacando-se a OPA do Grupo Sonae sobre a então PT, que só não teve sucesso por interferência política –, liderou sempre a comunicação de desporto, sendo a consultora de comunicação e marketing fora do estádio do Euro 2004, numa importante parceria com a UEFA, que viria a revelar-se um verdadeiro pilar para outros serviços entretanto prestados nesta área. O acompanhamento estratégico do Sport Lisboa e Benfica constituiu, em paralelo, um dos importantes marcos nos serviços de relações públicas e de aconselhamento estratégico da empresa. A empresa continuou a acompanhar nos anos seguintes a UEFA na organização da comunicação e marketing fora dos estádios dos Europeus de Sub21, de Futebol Feminino, de Futsal, de Futebol de Praia, Liga dos Campeões e Liga das Nações. Em conjunto com a sua parceira espanhola, Grupo Albion, assessorou a comunicação financeira e de marketing no processo de aquisição, pela Ferrovial,

as seen by its Regulators” was also a resounding success while the fourth Cycle, “The Economy from the perspective of Great Economists”, closed this period with a golden key. The twenty years of experiences now being commemorated are the mirror of its Clients, Suppliers and, of course, Staff. The path of the company was always coherent but the market has many fluctuations of growth and contraction. Portugal and other markets the firm operates in went through their own distinct cycles – political and economic – and the financial health existing today went through troubled times between 2012 and 2015. A badly calculated business risk in an international market and the convulsions resulting from a bank going under dragging down all the companies directly or indirectly related, forced CV&A into drastic measures in order to be able to survive. The firm counted on the support of the banks with which it maintained commercial relationships, some suppliers and, as always, its staff.

The general overview of the twenty years under celebration is one of strong and sustained growth both in terms of the number of clients and in fundamental values. The variety of services provided and their preponderance in terms of turnover has varied alongside the weightings of our international markets reflecting the ways in which the management was able to respond, to a greater or lesser extent, to the demands of each culture. The weightings of product communication, institutional communication, coupled with the financial facet, political communication, the changes in the ways, means and methods ongoing in the digital world means adapting to the times lived in with the emergence of public issues with higher profiles in recent years and with this trend set to deepen. The company that started out in Lisbon, today employs 32 staff and also has offices in Oporto, Funchal, Luanda, Maputo and São Paulo and, as a member of the H/Advisors (the new Havas Group brand for the Public Relations sector) network, ensuring services in many more countries on these continents. In its various years of life, the company participated in the largest financial operations taking place in Portugal both on the buy-side and on the sell-side – highlighting the Sonae Group takeover bid for the then PT telecommunications company that only failed because of political interference -, and has always led in sports communication, serving as the non-stadium communications and marketing consultancy for the Euro 2004 championship, in an important partnership with UEFA, which would turn into a foundation for the other services provided in this area. The strategic advising of Sport Lisboa e Benfica constituted, in parallel, one of the most important brands for the public relations and strategic consultancy of the company. The company continued to render support to UEFA in the following years and organising the communications and marketing campaigns outside of stadiums for the European Sub21, Female Football, Futsal, Beach Football, Champions League and League of Nations football tournaments. In conjunction with its Spanish partner, Grupo Albion, the

8

EDITORIAL

da British Airport Authority que gere os aeroportos britânico de Heathrow e Gatwick, entre outros. Internacionalmente, a Cunha Vaz & Associados foi a empresa contratada pela Conferência Episcopal de Angola e São Tomé para coordenar todas as actividades de organização, logística e de comunicação referentes à visita apostólica de Sua Santidade, o Papa Bento XVI, a Angola e um ano depois a Cunha Vaz & Associados é escolhida, pelo Estado Angolano e pelo Comité Organizador do Campeonato Africano das Nações, para a realização das cerimónias de sorteio, abertura e encerramento desse mega-evento desportivo que foi o CAN 2010. Segue-se a escolha como a empresa responsável pela organização de todo o evento de apresentação da convocatória da Selecção Nacional para o Mundial 2010 e consultora responsável pela comunicação e assessoria mediática da Viagem Apostólica de Sua Santidade o Papa Bento XVI, a Portugal, seguindo-se a proposta vencedora do concurso de promoção dos Jogos Africanos Moçambique 2011. Dá-se a primeira intervenção no mundo da política internacional, com a CV&A a prestar assessoria ao MpD (Movimento para a Democracia) de Cabo Verde, que vence as eleições autárquicas, reforçado o número de mandatos e o número de votos expressos. Seguir-se-iam duas campanhas presidenciais vitoriosas em Cabo Verde, três intervenções semelhantes na Guiné-Bissau e diversas participações em campanhas legislativas regionais e autárquicas nacionais que muito nos orgulham. Não ganhamos eleições. Isso é trabalho dos políticos. Colaboramos nas campanhas eleitorais e como nem só de vitórias se fazem as campanhas – e uma das que mais nos orgulhamos foi aquela em que estivemos com António Carmona Rodrigues em que o nosso candidato não foi eleito. A última campanha política em que a CV&A teve intervenção foi em Israel, apoiando o partido “New Hope”, moderado, que perdeu as eleições, mas que nos deu a conhecer uma realidade que desconhecíamos até à data. Terminamos com os nossos números oficiais:

Facturação: €10.028.849,43 (dez milhões, vinte e oito mil, oitocentos e quarenta e nove euros e quarenta e três cêntimos).

Número de colaboradores: 32 (trinta e dois)

Lucro antes de impostos: €3.113.062,66 (três milhões cento e treze mil e sessenta e dois euros e sessenta e seis cêntimos).

EBIT: €3.212.182,10 (três milhões, duzentos e dezoito mil, cento e oitenta e dois euros e dez cêntimos)

EBITDA: €3.136.368,85 três milhões, cento e trinta e seis mil, trezentos e sessenta e oito euros e oitenta e cinco cêntimos)

Portugal e os restantes países em que operamos têm progredido muito face a um passado recente e com menos de cinquenta anos. Mas muito há a fazer. Mãos à obra, pois! Contamos com todos para olhar o amanhã com optimismo. Num tempo de mudança global, num momento de incerteza na política internacional, que se vai reflectindo na economia em que nos movemos, todos os esforços são poucos para assegurar a construção de um futuro sustentável, com respeito pela história dos povos, sem julgamentos do passado e com a exclusiva preocupação de ajudar a construir um mundo justo para todos.

firm advised on the financial and marketing communications for the Ferrovial takeover of the British Airport Authority, which runs Heathrow and Gatwick, among other airports. Internationally, Cunha Vaz & Associados was the company contracted by the Episcopal Conference of Angola and São Tomé to coordinate all the organisational, logistics and communications activities around the visit of His Highness, Pope Benedict XVI to Angola and with Cunha Vaz & Associados, one year later, selected by the Angolan state and the Organising Committee of the African Nations Cup to stage the draw, opening and closing ceremonies at the mega-sporting event that was CAN 2010. This was followed by the company’s selection as organiser for the entire event presenting the National Squad for the World Cup 2010 and the consultancy responsible for media communications and advisor on the visit by His Highness Pope Benedict XVI to Portugal followed by winning the tender to promote the African Games in Mozambique in 2011. There was then the first intervention in the international political world with the CV&A providing advisory services to the MpD (Movement for Democracy) in Cape Verde, which won the local elections, strengthened the number of mandates and its share of the votes. This was then followed by two victorious presidential campaigns in Cape Verde, three similar campaigns in Guinea Bissau and various different contributions to national, regional and local election campaigns in Portugal of which we are deeply proud. We do not win elections. That is the work of politicians. We contribute to the electoral campaigns and these inevitably do not only produce successes – and one of the campaigns which we recollect with greatest pride was for António Carmona Rodrigues when our candidate did not win the election. The most recent political campaign in which CV&A intervened was in Israel in support of the moderate “New Hope” party that lost the elections but gave us insights into a hitherto unknown reality. We shall close with our official figures:

Turnover: €10,028,849.43 (ten million, twenty-eight thousand, eight-hundred and forty-nine euros and forty-three cents); Number of staff: 32 (thirty-two);

Pre-tax profit: €3,113,062.66 (three million, one-hundred and thirteen thousand and sixty-two euros and sixty-six cents);

EBIT: €3,212,182.10 (three million, two-hundred and twelve thousand, one-hundred and eighty-two euros and ten cents);

EBITDA: €3,136,368.85 (three million, onehundred and thirty-six thousand, three-hundred and sixty-eight euros and eight-five cents).

Portugal and the other countries in which we operate have progressed greatly given their recent pasts and less than fifty years of history. However, there is much to be done. Indeed, time to get to work! We count on everybody to look to the future with optimism. At a time of global change, with great international political uncertainties, which generate repercussions for the economies in which we act, all the efforts are scant to ensure the construction of a sustainable future, with respect for the histories of peoples, without judgements of the past and with an exclusive concern to help build a fairer world for all.

9

EDITORIAL

AMO and H/Advisors – A short history

NEIL BENNETT, CO-CEO H/ADVISORS

It all started 22 years ago on Madison Avenue. Three of the world’s most senior financial PR professionals met to discuss a ground-breaking alliance, that would change the shape of the communications industry. The agreement they forged on that unseasonably warm spring day in midtown New York laid out the principles and ambitions that still guide H/Advisors today, and created the organisation that is proud to have Cunha Vaz & Associates (CV&A) as a member. The three men were: Jim Abernathy, founder and chairman of Abernathy MacGregor, the US communications firm; Angus Maitland, Founder and Chairmen of The Maitland Consultancy in London; and Stephane Fouks, President of Euro RSCG in France (the agency that later become Havas Paris). Each of them had very different backgrounds, but one overriding common interest. Jim had been a journalist and communications professional before creating Abernathy. Angus had actually started his career as an economist before going on to run Valin Pollen and then founding his own agency. Stephane’s career began very differently, as a music producer before rising to become Chief of Staff to the French Prime Minister and then creating in turn his agency Omnium, which he later sold to Havas. Fate and high finance had brought them together. In the preceding months Havas had acquired stakes in both Abernathy and Maitland to add to its growing international empire. Now the three of them were colleagues. It was Jim who was the first to spot the opportunity in all this, to forge something greater out of the three constituent parts. So, he convened a conference for all Havas PR people in New York to discuss greater collaboration. It was quickly obvious to them that although they had in many ways been thrust together, they could use the opportunity to create something bigger than all of them – an alliance and a collaboration that would create one of the world’s first truly global communications groups. Naming it was tricky; they discussed long and hard what to call it. Stephane had the key: “it was obvious that it had to

be called after all three firms and my firm needed to be last. I said to Jim and Angus that it was either going to be called MAO or AMO. I am not surprised they chose the latter.” AMO it was, short and simple, with the added benefit that it means ‘I love’ in Latin - so perfect for a group of PR and communications firms. But more important than the name were the values behind it. AMO was not a company or a group, with one individual or one city or country dominating, but a network and an alliance. “From the start we were clear we wanted it to be based on willingness and friendship and on mutual respect rather than any corporate structure. That way we were confident it would bring the best out in everyone.” Today H/Advisors stays true to that founding principle. Each of our offices and agencies are treated as equals and we work together in a spirit of co-operation, which we strongly believe delivers the best results for our clients. Crucially we only invite members that are leaders in their own countries or cities, so our clients can be confident they are getting the very best service and advice wherever or whatever they need.

The three founding members of AMO quickly became five, as Angus’s longstanding-relationships with agencies in Spain and Germany asked to join. And the results were dramatic; since it was founded AMO and now H/Advisors has always been at or near the top of the M&A league tables, as compiled by Mergermarket. In time AMO grew and grew. In 2004 we welcomed Hirzel Neef Schmidt Counselors in Switzerland, when they reached out to Maitland to work with them on a particularly demanding brief for Sulzer. In 2010 we expanded into Asia for the first time when Havas acquired a majority stake in Porda, the leading Hong Kong agency. Hallvarsson & Halvarsson from Sweden joined, as did SPJ in the Netherlands. CV&A first joined us as an Associate member in 2020 and quickly made their mark. From the very beginning, AMO and now H/Advisors has been proud to be an ‘open architecture’ communications group. This means that while many of our offices and agencies are either

10

OPINIÃO

wholly or partly owned by Havas, we also welcome independent partners who for whatever reason, do not want to become part of Havas at that stage. So Ashton in Japan for example is a thriving member of H/Advisors, even though it has a different ownership structure. This belief marks us out from the ‘top down’, ‘one size fits all’ ethos of many of our competitors. More recently we have also expanded laterally into new disciplines, most notably public affairs. AMO was always a public affairs powerhouse in Paris, but in 2020 we transformed the practice into an international one, by acquiring Cicero in the UK and Brussels and opening a highly successful Abernathy office in Washington DC. Today we work on some of the world’s most prestigious public affairs mandates, from modest beginnings only a decade ago. After many years of growth and development, AMO was given a welcome endorsement at the highest level. Yannick Bollore, then Chairman of Havas and now Chairman of Vivendi, recognised the success of the network and announced in 2018 that Havas planned to invest €100 million in the network. That commitment accelerated our growth and development. We cemented our presence in Germany with the acquisition of DAA [Deekeling Arndt] that year, followed by the acquisition of Tinkle in Spain in 2022. Further acquisitions are in the pipeline. We also took steps to bring the whole network closer together. As part of this we introduced an exchange programme, where young ambitious consultants from each office are given the chance to spend four weeks working in another office, getting to know their international colleagues and their ways of working. Last year 14 took part, spanning the globe. Last year we took the next step in drawing our world-leading network together, with the creation of a powerful new brand and management team, to reflect a group that

now has more than 1400 colleagues in 20 countries. AMO was a name that had served us well over the years but was only ever intended as a starting point. We felt we needed a new name that reflects the scale and ambition of the group today and we chose H/Advisors – the H for Havas and Advisors because that is who we are – strategic communications advisors to the world most significant organisations. H/Advisors’ new management team reflects both a strong sense of continuity and link to our past, but also our ambition and drive. Stephane Fouks is our Executive Chairman, while Tom Johnson and I, respectively the CEOs of Abernathy and Maitland, are co-CEOs, with more than 30 years of combined experience of the business. Angus Maitland remains a special advisor to the group. Together we are working to expand H/Advisors further, while ensuring that we share its enormous pool of knowledge and talent for the benefit of all our clients. The work continues at pace. Last month [May] we opened our first office in the Middle East, in Dubai, with a reception for more than 200 people and a commitment to support clients during COP28, the environmental conference being held there in November. We also launched our latest piece of global research, on the prevalence of leaks in global M&A and the impact they have on deals. Plans are already well underway for our first global strategy summit in September that will bring hundreds of H/Advisors professionals together to discuss the future of the business.

On behalf of Stephane and Tom, and everyone at H/Advisors, we are delighted to count Antonio Cunha Vaz and all of his team as our colleagues and we are looking forward to working ever more closely with them, supporting clients when they need us most, learning from each other and taking H/Advisors on to its next chapter.

11

OPINION

Conferências com chancela

CV& A

The CV& A conferences

Ao longo de duas décadas, a CV&A tem vindo a promover conferências de relevo e interesse nacional, com a presença de diversos ex-chefes de Estado e de Governo e dirigentes políticos de influência mundial, como por exemplo Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, José Maria Aznar, Al Gore ou Colin Powell. Este ano, e para comemorar o seu 20º aniversário, a CV&A traz a Portugal o antigo Primeiro-Ministro do Reino Unido David Cameron para um debate com Carlos Moedas, presidente da Câmara Municipal de Lisboa e antigo comissário europeu, sobre o Futuro da Europa. O evento tem lugar no dia 15 de Junho, na Estufa Fria, em Lisboa.

Throughout these two decades, CV&A has been staging high profile conferences of great national interest and attracting the participation of former heads of government and political leaders with global influence, including Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, José Maria Aznar, Al Gore and Colin Powell, for example. This year, and to commemorate its 20th anniversary, CV&A is bringing David Cameron, the former British Prime Minister, to Portugal to debate the Future of Europe with Carlos Moedas, President of Lisbon Municipal Council and former European commissioner. This event is taking place on 15 June at the Estufa Fria in Lisbon.

12

DESTAQUE ADOBE STOCK

s conferências Cunha Vaz & Associados (CV&A) são hoje dia uma referência a nível nacional. Ao longo dos seus 20 anos de atividade, a CV&A trouxe a Portugal protagonistas de projecção mundial com perspectivas únicas sobre a globalidade e que marcaram, por uma ou outra razão, em vários sectores, desde a economia, a política, sociedade, ciência e tecnologia, um determinado período no tempo. A primeira destas grandes conferências ocorreu logo em 2005, um anos após a fundação da CV&A, com José Maria Aznar (antigo presidente do governo espanhol), seguindo-se Colin Powell (Ex-Secretário de Estado dos Estados Unidos), George Bush (ex-presidente dos Estados Unidos), John Snow (antigo Secretário do Tesouro dos Estados Unidos), Al Gore (vice-presidente dos Estados Unidos), Tony Blair (ex-primeiro-ministro britânico), Bill Clinton (ex-presidente dos Estados Unidos), Muhammad Yunus (economista, Nobel da Paz de 2006), David Plouffe (director da campanha de Barack Obama à Presidência dos Estados Unidos), Álvaro Uribe (ex-Presidente da Colômbia), Gerhard Schröder (antigo chanceler alemão), John Bruton (ex-primeiro-ministro irlandês), Mario Monti (ex-primeiro-ministro da Itália), entre outros. Para além destas, juntaram-se mais três conferências

ANA VALADO

ANA VALADO

The Cunha Vaz & Associados (CV&A) conferences have long since become a national reference point. Throughout these 20 years of activity, CV&A brought to Portugal global figures with unique perspectives on the world and who have, in one way or another, impacted on various sectors, ranging from the economy, politics, society, science and technology, over a determined period of time. The first of these major conferences took place in 2005, two years on from the launch of CV&A, with José Maria Aznar (former Spanish Prime Minister), followed by Colin Powell (former Secretary of State of the United States), George Bush (former President of the United States), John Snow (former Treasury Secretary of the United States), Al Gore (former Vice-President of the United States), Tony Blair (former British Prime Minister), Bill Clinton (former President of the United States), Muhammad Yunus (economist, 2006 Nobel Peace Prize winner), David Plouffe (director of the American Presidential Campaign of Barack Obama), Álvaro Uribe (former President of Colombia), Gerhard Schröder (former Chancellor of Germany), John Bruton (former Irish Prime Minister), Mario Monti (former Italian Prime Minister), among others. In addition to these keynote speakers, there were also three thematic conferences: “Portugal: Threat or Opportunity”,

13

A T

FEATURED

CONFERÊNCIAS CV&A / CV&A CONFERENCES

JOSÉ MARIA AZNAR

“As Relações Ibéricas e o Contexto do Diálogo Transatlântico”

“Iberian Relations and the Context of the Transatlantic Dialogue”

Lisboa, Abril 2005 | Lisbon, April 2005

COLIN L. POWELL

“Leadership: Taking Charge”

Lisboa, Dezembro 2005 | Lisbon, December 2005

JOHN W. SNOW

“The International Economy Today: Challenges and Opportunities”

Lisboa, Novembro 2006 | Lisbon, November 2006

AL GORE

“Uma Verdade Inconveniente”

“An Inconvenient Truth”

Lisboa, Fevereiro 2007 | Lisbon, February 2007

TONY BLAIR

“Economic Development and World Peace”

Lisboa, Dezembro 2007 | Lisbon, December 2007

WILLIAM J. CLINTON

“Embracing our Common Humanity”

Lisboa, Junho 2008 | Lisbon, June 2008

MUHAMMAD YUNUS

“Challenging Poverty: The Growth of Microcredit”

Lisboa, Outubro 2008 | Lisbon, October 2008

DAVID PLOUFFE

“Building a Grassroots Movement in the 21st Century”

Lisboa, Março 2009 | Lisbon, March 2009

ÁLVARO URIBE

“The rise of the South American emerging markets”

Lisboa, Maio 2011 | Lisbon, May 2011

RAPHAEL MINDER (Herald Tribune), WOLFGANG

MÜNCHAU (Financial Times), RAUL LLORES (Folha de São Paulo)

“Portugal: ameaça ou Oportunidade”

“Portugal: Threat or Opportunity”

Lisboa, Novembro 2011 | Lisbon, November 2011

GERHARD SCHRÖDER

“A Crise Europeia e as Reformas Necessárias”

“The European Crisis and the Reforms Necessary”

Lisboa, Dezembro 2012 | Lisbon, December 2012

A Nobel Day in Lisbon

Lisboa, Junho 2013 | Lisbon, June 2013

14

Al Gore, Museu da Electricidade

DESTAQUE

José María Aznar, Hotel Ritz

temáticas: “Portugal: ameaça ou Oportunidade”, em 2011, com Raphael Minder (Herald Tribune), Wolfgang Münchau (Financial Times), Raul Llores (Folha de São Paulo); “A Nobel Day”, em 2013, com John Gurdon, Oliver Smithies, Paul Greengard e Richard J. Roberts, Karin Schallreuter, Paul Riley e Clemens van Blitterswijk; e “Cybersecurity, em 2016, com Ofir Hason, Rui Gomes, Paulo Veríssimo e António Mexia. A CV&A promoveu, ainda, ciclos “Conferências do Palácio”, reunindo no Palácio da Bolsa, no Porto, alguns dos principais parceiros externos de Portugal, relevantes individualidades do tecido empresarial português, presidentes dos conselhos das mais importantes empresas nacionais e reputados economistas portugueses.

Este ano, no âmbito da comemoração do seu 20º aniversário, a CV&A traz a Portugal David Cameron, antigo Primeiro-Ministro britânico, para um debate com o presidente da Câmara Municipal de Lisboa Carlos Moedas. Neste fórum vai ser discutido o Futuro da Europa. As conferências com chancela CV&A fazem parte do ADN da consultora e além de já terem um público fidelizado. Cada conferência tem uma “taxa de ocupação” na ordem das 300 participantes.

in 2011, with Raphael Minder (Herald Tribune), Wolfgang Münchau (Financial Times), Raul Llores (Folha de São Paulo); “A Nobel Day”, in 2013, with John Gurdon , Oliver Smithies, Paul Greengard and Richard J. Roberts, Karin Schallreuter, Paul Riley and Clemens van Blitterswijk; and “Cybersecurity”, in 2016, with Ofir Hason, Rui Gomes, Paulo Veríssimo and António Mexia. CV&A has also staged the cycles “Conferences at the Palace”, held at the Bolsa Palace in Oporto, attracting some of Portugal’s leading external partners, prominent individuals from the Portuguese business sector, board presidents of leading national companies and renowned Portuguese economists. This year, under the auspices of commemorations of its 20th anniversary, CV&A is bringing the former British Prime Minister, David Cameron, to Portugal for a debate with the President of Lisbon Municipal Council, Carlos Moedas. This forum is set the theme of the Future of Europe. The CV&A staged conferences are part of this consultancy’s DNA and have already established a loyal public. Each conference attracts an “occupation rate” of around 300 participants.

15

Tony Blair, Culturgest

William J. Clinton, Museu da Electricidade

FEATURED

Gerhard Schröder, Lisboa

David Cameron foi Primeiro-Ministro do Reino Unido entre 2010 e 2016, liderando o primeiro Governo de coligação britânico em quase 70 anos e, nas eleições gerais de 2015, formando o primeiro Governo de maioria conservadora no Reino Unido em mais de duas décadas.

Cameron chegou ao poder em 2010, num momento de crise económica e com um desafio fiscal sem precedentes. Sob a sua liderança, a economia do Reino Unido transformou-se. O défice foi reduzido em mais de dois terços, foram criadas um milhão de empresas e um número recorde de postos de trabalho, tornando-se a Grã-Bretanha a economia avançada com o crescimento mais rápido do mundo. Este cenário criou a estabilidade que o governante necessitava para reduzir os impostos, introduzir o salário mínimo obrigatório, transformar a educação, reformar a segurança social, proteger o Serviço Nacional de Saúde e aumentar as pensões. As decisões difíceis que tomou traduziram-se, enquanto a economia crescia, numa diminuição das famílias dependentes da assistência social, num aumento do número de estudantes que frequentam a universidade e do número de pessoas a trabalhar, sendo o mais elevado comparando com qualquer outro momento da história britânica.

A nível internacional, David Cameron desenvolveu uma política externa na era pós-Iraque que abordou os novos desafios da Primavera Árabe, bem como uma Rússia mais agressiva, assegurando ao mesmo tempo que a Grã-Bretanha desempenhasse um papel na luta global contra o ISIS. Sob a sua direcção, o Reino Unido construiu uma forte parceria com a Índia e tornou-se o parceiro preferido da China no Ocidente. Durante todo o período da sua governação, defendeu a estreita relação entre o Reino Unido e os Estados Unidos. Depois de acolher com êxito os Jogos Olímpicos e Paraolímpicos de Londres 2012, David presidiu à Cimeira do G8 de 2013 em Lough Erne, na Irlanda do Norte, onde salientou a necessidade global de impostos justos, maior transparência e abertura comercial. Na sequência desta cimeira e de um debate mundial que durou dois anos, liderado por um painel de alto nível das Nações Unidas, ao qual co-presidiu, foram acordados os Objectivos de Desenvolvimento Sustentável (ODS).

Cameron defendeu as questões ambientais com o objectivo de criar o governo mais ecológico de sempre - como tal, fez crescer a economia britânica enquanto as emissões de carbono diminuíram drasticamente; criou o primeiro Banco de Investimento Verde do mundo; e assegurou que o Reino Unido desempenhasse um papel de liderança no bem-sucedido Acordo de Paris sobre as alterações climáticas.

Liderou o caminho a nível internacional ao aprovar a lei britânica sobre o casamento entre pessoas do mesmo sexo, estabeleceu as práticas de voto no Reino Unido durante uma geração, através de três referendos nacionais realizados enquanto esteve no nº 10 da Downing Street; e ofereceu mais dois votos nacionais

decisivos: o primeiro sobre o lugar da Escócia no Reino Unido; o segundo sobre o lugar do Reino Unido na União Europeia. Ao vencer o referendo escocês de 2014 garantiu que a Escócia continuasse a fazer parte do Reino Unido. No entanto, apesar de argumentar que a Grã-Bretanha era mais forte dentro da União Europeia, em Junho de 2016, o povo britânico votou a favor da saída da UE.

Na sequência desta derrota, Cameron demitiu-se do cargo de Primeiro-Ministro e líder do Partido Conservador a 13 de Julho de 2016. Em Setembro de 2016, demitiu-se do cargo de deputado ao Parlamento.

David Cameron tornou-se líder do Partido Conservador em 2005, depois de ter cumprido menos de cinco anos como deputado ao Parlamento. Foi eleito com um mandato para reformar e modernizar um partido que tinha perdido três eleições consecutivas. Foi por acreditar num conservadorismo moderno que David se candidatou a líder e também o que o levou a formar

16

PERFIL DESTAQUE

David Cameron was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom between 2010 and 2016, leading the first British coalition government in almost 70 years before, in 2015, forming the first majority Conservative government in over two decades. Cameron came to power in 2010, during a period of economic crisis and with the country in an unprecedented fiscal position. Under his leadership, the British economy was transformed. The deficit was reduced by over two-thirds, a million companies got launched and there were records in terms of job creation, turning the United Kingdom into the advanced economy registering the fastest growth rate. This scenario brought about the stability that the government needed to cut taxes and introduce the national minimum wage, transforming education, reforming the social security system, protecting

the National Health Service and raising pensions. The difficult decisions then taken reflected in, as the economy grew, a fall in the number of households dependent on social welfare, a rise in the number of students attending university and the numbers in employment reaching the highest level at any point in time in British history.

At the international level, David Cameron advanced with foreign policies in a post-Iraq era that approached the new challenges of the Arab Spring, as well as a more aggressive Russia, while ensuring the United Kingdom played a significant role in the global struggle against ISIS. Under his leadership, the United Kingdom built up a strong partnership with India and became the preferred partner of China in the West. Throughout his time in office, he defended a close relationship between the United Kingdom and the United States. After having successfully hosted the Olympic and Paralympic Games in London during 2012, David chaired the 2013 G8 Summit in Lough Erne, in Northern Ireland, where he highlighted the need for fair global taxes, greater transparency and commercial openness. In the wake of this summit and a global debate that lasted two years, led by a high level United Nations panel that he co-chaired, there was agreement over launching the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Cameron always defended environmental issues and strove to create the most ecological government ever – as such, the British economy was able to grow even while its carbon emissions fell sharply; he founded the world’s first Green Investment Bank and had the United Kingdom playing a driving leadership role in the Paris Agreement on climate change. He led the way internationally in approving the British law allowing for same sex marriages, and changed the voting practices that had prevailed in the United Kingdom for a generation by staging three national referenda while the occupant of number 10 Downing Street; and two were particularly significant: the first on the place of Scotland in the United Kingdom; the second on the place of the United Kingdom in the European Union. In winning the Scottish referendum in 2014, he guaranteed Scotland remained part of the United Kingdom. However, despite personally arguing that the United Kingdom was better off inside the European Union, in June 2016, a small majority of the British people voted in favour of leaving the EU. Following this defeat, Cameron resigned as Prime Minister and leader of the Conservative Party on 13 July 2016. In September 2016, he resigned as a member of parliament. David Cameron became leader of the Conservative Party in 2005, after having completed less than five years as an MP. He was elected on a mandate to reform and modernise a party that had lost three consecutive elections. It was out of his belief in modern conservatism that David ran for the leadership and also led him to form the first coalition government in the United Kingdom for seven

17

FEATURED

PROFILE

PERFIL PROFILE

o primeiro Governo de Coligação do Reino Unido em sete décadas, governando assim como Primeiro-Ministro.

Durante a sua liderança promoveu a justiça e a acção social; fez avançar a agenda ecológica; definiu a protecção do Serviço Nacional de Saúde como uma prioridade para o Reino Unido e orgulhou-se de ver um aumento significativo do número de mulheres e de candidatos de minorias étnicas que se candidataram pelo Partido Conservador e foram eleitos para o Parlamento.

Enquanto deputado pelo círculo eleitoral rural de Witney, em West Oxfordshire, desde 2001, David ocupou uma série de cargos na bancada da oposição antes de se tornar líder do partido. Após as eleições gerais de 2005, foi nomeado Secretário de Estado Sombra da Educação. Anteriormente, ocupou vários cargos políticos.

Antes de se tornar deputado, David trabalhou em várias empresas e na administração pública.

Após passar pelo colégio secundário de Eton, nos arredores de Londres, Cameron estudou Filosofia, Política e Economia no Brasenose College da Universidade de Oxford.

Depois de se licenciar, entrou para o Departamento de Investigação do Partido Conservador, onde trabalhou para a Primeira-Ministra Margaret Thatcher e para o seu sucessor John Major. Mais tarde, foi nomeado Conselheiro Especial do Governo, primeiro no Tesouro e depois no Ministério do Interior.

Posteriormente, passou sete anos na Carlton Communications, uma das principais empresas de comunicação social do Reino Unido, e fez parte do conselho de administração.

Desde que deixou o nº 10 de Downing Street, David continuou a centrar-se nas questões que promoveu enquanto esteve no cargo: apoiar as oportunidades de vida dos jovens e construir uma sociedade mais forte e mais justa; defender a investigação médica; e promover o desenvolvimento internacional.

David Cameron é Presidente do Patronato do National Citizen Service (NCS), o principal programa de desenvolvimento juvenil do Reino Unido. É também Presidente da Alzheimer’s Research UK, a principal instituição britânica de investigação médica com especial incidência no financiamento da investigação biomédica sobre a causa, a prevenção e a cura da demência.

No âmbito do papel que assumiu enquanto Primeiro-Ministro na defesa dos Objectivos de Desenvolvimento Sustentável das Nações Unidas, tem trabalhado com a London School of Economics e a Blavatnik School of Governo da Universidade de Oxford.

Também faz parte do Conselho Global de Relações Externas e é membro do Conselho de Administração da ONE Campaign. Para além destas funções, David Cameron aconselha e trabalha com várias empresas internacionais nos sectores da tecnologia, finanças e inovação médica.

Nascido em Londres em Outubro de 1966 e proveniente de uma família aristocrática, David Cameron é casado e tem três filhos. A família sempre foi a parte mais importante da sua vida, sustentando-o ao longo da sua carreira política e no cargo de Primeiro-Ministro.

decades and thereby taking office as Prime Minister. During his leadership, he fostered justice and social actions; he deepened the ecological agenda; defined protecting the National Health Service as a priority for the United Kingdom and took due pride in significantly raising both the number of women and ethnic minority candidates running for office on behalf of the Conservative Party and the numbers reaching Parliament.

As MP for the rural constituency of Witney, in West Oxfordshire, since 2001, David occupied a series of positions on the opposition bench prior to become party leader. Following the general election of 2005, he was nominated Shadow Secretary of State for Education. He had previously held a series of political positions. Furthermore, prior to becoming an MP, David worked for various companies and in public administrative positions. After attending Eton, on the outskirts of London, Cameron studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics at Brasenose College of the University of Oxford. After graduating, he joined the Research Department of the Conservative Party, where he worked for Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her successor John Major. He was later nominated a Special Adviser to the Government, first in the Treasury and subsequently in the Home Office. Subsequently, he spent seven years at Carlton Communications, one of the leading media and public relations companies in the United Kingdom, where he sat on the Board of Directors. Ever since leaving number 10 Downing Street, David continued to focus on the issues that were his priorities in office: supporting life opportunities for young people and building a stronger and fairer society; promoting medical research; and advocating for international development. David Cameron is Chairman of the Patrons’ Board of the National Citizen Service (NCS), the leading youth development program in the United Kingdom. He is also President of Alzheimer’s Research UK, the leading British medical research institution with a particular focus on financing biomedical research on the causes, prevention and cure of dementia. Within the scope of the role played as Prime Minister in defending the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations, he has worked with the London School of Economics and the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford. He is also part of the Global Board of External Relations and is a Board Member of the ONE Campaign.

In addition to these functions, David Cameron advises and works with various international companies in the technology, financial and medical innovation sectors. Born into an aristocratic family in London in October 1966, David Cameron is married and has three children. His family was always the most important facet of his life, sustaining him in his long political career and while holding office as Prime Minister.

18

DESTAQUE

•

•

CH-6925M-EBBK

CH-6925M-EBBK

Open Gear ReSec Blue on Black Edição Limitada (50)

Open Gear ReSec Blue on Black Edição Limitada (50)

Movimento Automático C.301 com design inovador “OPEN GEAR” e apresentação retrógrada dos segundos

Movimento Automático C.301 com design inovador “OPEN GEAR” e apresentação retrógrada dos segundos

•

•

Mostrador em guilloché feito à mão, com design so sticado em 3D composto por 42 peças Caixa em aço de 44 mm com revestimento DLC

•

Mostrador em guilloché feito à mão, com design so sticado em 3D composto por 42 peças Caixa em aço de 44 mm com revestimento DLC

•

19

20 anos depois, estamos assim tão diferentes?

20 years later, are we really so different?

tender para a consideração de que nada mudou, em 20 anos. Todavia, atentando no quadro social, na dinâmica económica, na própria configuração do Parlamento ou até nos nossos meios de comunicação — cada vez mais digitais —, percebemos que a nossa realidade se transformou radicalmente. Duas décadas depois, este é, decerto, “outro país”, não deixando de ser “o Portugal de sempre”.

The structural problems today shaping the Portuguese reality have been on the agenda for decades. In this fairly grim scenario, we might be led to consider that nothing has changed in these last 20 years. However, taking into account the social framework, the economic dynamics, the very configuration of parliament or even our – increasingly digital – means of communication, we may grasp how our realities have undergone radical transformation. Two decades later, this is certainly “another country” while never giving up on being “the Portugal of always”.

Palavras como “sustentabilidade”, “electromobilidade”, “inteligência artificial” ou siglas como “ESG” e “LGBTQIA+” mostram um mundo bem diferente daquele que existia em 2003. Na altura, já fazíamos contas em euros, mas ainda estávamos a dar os primeiros passos no universo da Internet. Hoje, vivemos nas redes sociais, ouvimos músicas em plataformas digitais, compramos ‘online’ e usamos aplicações móveis para pagar as nossas contas. Estamos apetrechados com o mundo de possibilidades dos ‘smartphones’ e ‘smartwatches’. Somos, cada vez mais, adeptos dos carros eléctricos e estendemos milhares de ciclovias pelo país. De um mundo mais fechado e conservador, passámos para um cenário em que pessoas do mesmo sexo podem casar, em que é legal interromper voluntariamente a gravidez até às 10 semanas de gestação e em que se debate a eutanásia.

Words such as as “sustainability”, “e-mobility”, “artificial intelligence” or abbreviations such as “ESG” and “LGBTQIA+” convey the differences of the contemporary world to that prevailing in 2003. At the time, we were already doing our sums in euros but still taking our first steps into the universe of the Internet. Today, we live on social networks, we listen to music on digital platforms, we purchase online and have mobile apps to pay our expenses. We are all fitted out with the world of opportunities put forward by our smartphones and smartwatches. We are ever more enthusiastic about electric cars and hundreds of cycle paths have popped up across the country. From a more closed and conservative world, we entered a scenario in which same-sex marriages happen, abortion is legal through to 10 weeks and the debate around euthanasia is

21

Os problemas estruturais que marcam, hoje, a realidade portuguesa, persistem na agenda há décadas. Neste cenário pouco esperançoso, poderíamos

BLANDINA COSTA

PORTUGAL

LUÍS EUSÉBIO

Acompanhamos as tendências que vão moldando um mundo onde a pirâmide de poder coloca, progressivamente, a China no topo, numa balança global que pende, notoriamente, para o quadrante asiático. Ficou evidente a dependência que a Europa e os Estados Unidos têm das fábricas asiáticas, nas quais se produz grande parte dos ‘chips’ e dos semicondutores, que incorporamos nos nossos carros e equipamentos.

ongoing. We accompany the trends that are shaping the world in a pyramid of power that is progressively placing China at the top, in a global balance that is notoriously tilting towards Asia. The dependence of Europe and the United States on Asian factories which produce many of the chips and semiconductors to be incorporated into our cars and equipment. The very European Union changed, reconfigured in the wake of

22

PORTUGAL Fontes: INE e PORDATA

A própria União Europeia (UE) reconfigurou-se, ainda no rescaldo da queda do Muro de Berlim. O maior alargamento da sua história aconteceu logo em 2004, com a entrada de 10 novos países, seguindo-se mais três entradas, em 2007 e 2013. No entanto, com o Brexit, a esta Europa de 28 subtraiu-se, em 2020, o Reino Unido. Estas mudanças profundas estendem-se até hoje: a morte da Rainha Isabel II,

the fall of the Berlin Wall. The greatest enlargement in its history took place in 2004 with a total of 10 new states joining, followed by another three arrivals in 2007 and 2013. However, with Brexit, this Europe of 28 became one fewer with the departure of the United Kingdom in 2020. These profound changes are still ongoing: the death of Queen Elisabeth II, an unquestionable symbol of stability throughout over 75 years, gave way to a

23

PORTUGAL

símbolo inequívoco de estabilidade, durante 75 anos, deu lugar a uma nova era. Em 2023, coroou-se o Rei Carlos III, o mesmo ano em que se celebram os 650 anos da mais antiga aliança do mundo, reafirmando as relações bilaterais entre Portugal e Reino Unido. Mudámos muito, porém, agora — como há vinte anos —, continuamos familiarizados com duas palavras: “crise” e “guerra”. De uma crise económica, resultante da bolha das “dot-com”, chegámos a crises pandémicas e energéticas, tendo passado por uma crise financeira internacional. Da guerra no Iraque, no rescaldo do ataque terrorista às Torres Gémeas em Nova Iorque, partimos para uma guerra às portas da Europa, com a invasão da Ucrânia pela Rússia. Portugal não só não é alheio a estes acontecimentos, como defronta agora múltiplos (e repetidos) obstáculos. Em 2003, o país “estava de tanga”, como descreveu o recém-chegado primeiro-ministro social-democrata, Durão Barroso, referindo-se à crise económica que se vivia. Hoje, enfrentamos uma crise inflacionista, depois de uma crise de saúde pública, sempre acompanhados de uma alarmante crise ambiental, que parece não ter fim à vista. Neste contexto, a turbulência política e social é visível. Sucedem-se greves e manifestações de professores, médicos, enfermeiros ou jovens activistas, por exemplo, num país onde os mais novos só conseguem vislumbrar um futuro digno fora das fronteiras. A preocupante emergência da direita radical e populista evidencia o descontentamento de uma população que vive endividada perante o aumento do custo de vida, marcado pela inflação e pela subida das taxas de juro. Mas, contas feitas, estamos mais ricos ou mais pobres? Vivemos melhor ou pior do que em 2003? Qual é a relação entre os ciclos económicos e políticos? (ver infografia pág. anterior)

Após tantos abalos, quão robusta está a economia portuguesa?

Um olhar atento à evolução da taxa de crescimento do Produto Interno Bruto (PIB) evidencia as dificuldades que o país atravessou, nas últimas duas décadas. Neste período, contam-se seis anos de recessão. Só alcançámos taxas de crescimento acima dos 3% — valor médio registado na última década dos anos de 1900 — em três anos.

Da crise das dívidas soberanas à crise pandémica, passando por um resgate internacional

Principiámos o século XXI com a crise económica, nascida do rebentamento da bolha das “dot-com”, após a euforia das tecnológicas com o advento da Internet. Seguiu-se uma derrocada bolsista, que abalou toda a economia global, nos anos seguintes. Portugal não escapou ao contágio. Em 2003, o país já provava o sabor amargo da recessão. Na memória dos portugueses está mais fresca a crise desencadeada pela pandemia de COVID-19. Porém, os piores anos de recessão aconteceram antes disso, na sequência da crise financeira internacional — iniciada com a célebre queda do banco americano Lehman Brothers, em 2008, conhecida como “crise do subprime”. Essa crise levou Portugal, em 2011, a seguir os

new era. In 2023, King Charles III was coronated in the same year as commemorations of the 650th anniversary of the oldest diplomatic alliance in the world and reaffirming bilateral relationships between Portugal and the United Kingdom. We have changed a lot, nevertheless, now — just like twenty years ago —, we remain familiarised with two words: “crisis” and “war”. From a crisis resulting from the dot-com bubble, we arrived at the pandemic and energy crises having passed through the international financial crisis along the way. From war in Iraq, in the aftermath of the terrorist attack on the Twin Towers in New York, we now contemplate war at the entrance to Europe following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Portugal was not only no stranger to these events but faced multiple (and repeated) obstacles. In 2003, the country “was flat broke”, as the recently appointed social democratic prime minister, Durão Barroso, said in reference to the prevailing economic recession. Today, we are dealing with an inflationary crisis trailing in the wake of a public health crisis and always accompanied by an alarming environmental crisis that would seem to be endless in scope. In this context, the political and social turbulence is visible. There are successive strikes by teachers, doctors, nurses or young activists, for example, in a country where the young people are only able to perceive dignified futures beyond the national borders. The concerning emergence of a radical and populist right-wing reflects the discontent of a population who are heavily burdened by the rise in the cost of living, driven both by inflation and the interest rate hikes. However, when all is said and done, have we become richer or poorer? Do we live better or worse than in 2003? What is the relationship between the economic and political cycles?

After so many tremors how robust is the Portuguese economy?

A close look at the trend in the GDP growth rate displays the difficulties the country has experienced over these last two decades. In this period, there were six years of recession. We only obtained growth rates of above 3% — the average value registered over the 1900s — in three years.

From the sovereign debt crisis to the pandemic crisis, with an international bailout along the way

We started out in the 21st century with an economic crisis born out of the bursting of the dot-com bubble that had grown around the technologies and the advent of the Internet. This was followed by a stock market slump that sent ripples through the global economy in the following years. Portugal did not escape contagion. In 2003, the country was already tasting the bitterness of recession. Certainly fresher in the memories of the Portuguese is the crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, the worst years of recession had happened earlier in the wake of the international financial crisis — sparked by the spectacular implosion of the American Lehman Brothers bank

24

PORTUGAL

passos da Grécia, com a solicitação de um resgate internacional à “Troika” — conjugação de FMI, Banco Central Europeu e Comissão Europeia —, no valor de 78 mil milhões de euros. Esta crise foi uma das duas mais longas da história da economia portuguesa, tendo em conta o tempo dedicado à recuperação do PIB para níveis anteriores: começou em 2009 (seguindo a crise financeira mundial) e terminou apenas em 2018 (quando o PIB ultrapassou o valor de 2008).

Como evoluíram os principais indicadores económicos do país e a posição de Portugal na Europa?

Ao fim de duas décadas (e múltiplas crises), o país ficou relativamente mais pobre, comparativamente com os seus parceiros europeus. No início do século XXI, o PIB ‘per capita’ era de 85% da média europeia. Até 2022, esse valor regrediu para 77%, segundo estimativas preliminares, igualando assim o da Roménia que, em 2000, tinha apenas um terço do PIB ‘per capita’ português. Só cinco países da UE estão, hoje, piores do que Portugal: Letónia, Croácia, Grécia, Eslováquia e Bulgária. Resumindo, em 2003, cada português produzia uma riqueza de 17.253,1 euros (PIB ‘per capita’ a preços constantes), valor bastante similar aos 18.949,5 euros registados em 2021 (últimos valores disponíveis).

O Banco de Portugal fez as contas: entre 2000 e 2020, o crescimento médio anual do PIB real ‘per capita’ foi de apenas 0,3%. Os anos da pandemia de COVID-19 contribuíram fortemente

in 2008 in what became known as the subprime crisis. In turn, this led Portugal to follow in the steps of Greece and, in 2011, to request an international bailout from the Troika — the combination of the IMF, the European Central Bank and the European Commission — for a total amount of 78 billion euros. The recession was one of the two longest in Portuguese economic history, taking into account the time required for GDP to recover to the previously existing level: beginning in 2009 (in the midst of the world financial crisis) and ending only in 2018 (when GDP again exceeded the 2008 level).

How did the main national economic indicators and the position of Portugal in Europe evolve?

At the end of two decades (and multiple crises), the country was left relatively poorer in comparison with its European peers. At the beginning of the 21st century, the GDP per capita stood at 85% of the European average. Through to 2022, this average had fallen back to 77%, according to some preliminary estimates, thus level par with Romania that, in 2000, had a per capita GDP rate only a third of the Portuguese. Only five EU member states are today poorer than Portugal: Latvia, Croatia, Greece, Slovakia and Bulgaria. In summary, in 2003, each Portuguese citizens produced wealth of 17,253.10 euros (GDP per capita at constant prices), a broadly similar figure to the 18,949.50 euros registered in 2021 (latest figures available).

25

PORTUGAL

para esta queda. No entanto, mesmo se os excluirmos, o crescimento médio foi de 0,8% — valor bem distante da taxa média anual da segunda metade do século passado (3,9%). Mesmo com um crescimento insignificante, isso não significa que esteja tudo igual. Analisando com mais detalhe os vários ramos de actividade e os seus respectivos contributos para a produção de riqueza, o ex-ministro da Economia, Pedro Siza Vieira, constata que o perfil da economia portuguesa se alterou. O peso da construção e do imobiliário diminuiu, bem como o dos serviços financeiros. Por outro lado, o turismo e as tecnologias de informação e comunicação conquistaram importância. A indústria cresceu à boleia das exportações, que atingiram um peso de 50% no PIB nacional. Como referência, verificamos que, em 2003, as vendas ao exterior valiam apenas cerca de 28%. Examinando um caso específico, a nossa dependência económica do turismo intensificou-se. O contributo desse sector para o PIB nacional cresceu de 4,5%, em 2003, para 10,9%, em 2022. Mesmo mostrando sinais promissores, para que a economia possa crescer, revela-se crucial diminuir o endividamento, quer do sector público, quer do sector privado, sobretudo numa época de subida das taxas de juro.

O caminho atribulado das contas públicas

Na sequência da crise das dívidas soberanas, que levou Portugal a pedir o resgate internacional em 2011, a dívida pública atingiu um máximo de 132,9% do PIB, em 2014. Tendo Portugal saído do resgate financeiro internacional no período definido de quatro anos, nos anos seguintes foi possível reduzir, de forma significativa, o rácio da dívida, que em 2019 era já 116,6% do PIB. Nesse ano, Portugal assinalou outro feito nas contas públicas, com as administrações públicas a registarem o primeiro excedente orçamental da democracia portuguesa: 0,1% do PIB. O ministro das Finanças da época, Mário Centeno, atribuiu este feito à dinâmica da economia e do mercado de trabalho, que permitiu incrementar a receita fiscal e as contribuições das empresas para a Segurança Social. De facto, o país conseguiu reduzir a taxa de desemprego do pico histórico de 17,1%, em 2013, para menos de metade. Em 2022, situava-se nos 6,5%. A Portugal valeu a política monetária acomodatícia (‘quantitative easing’) do Banco Central Europeu, até meados de 2022, que beneficiou as contas públicas nacionais, como afirmou, em 2016, o presidente do BCE, Mario Draghi, numa sessão com os eurodeputados: “As reduções das taxas de juro do BCE estão a beneficiar, em grande medida, países vulneráveis da zona euro, e a fragmentação dos custos de financiamento e as condições de empréstimo em diferentes países têm diminuído.”

A trajectória das contas públicas e da economia nacional parecia apontar para um futuro mais risonho, todavia, a pandemia de COVID-19 não deu tréguas. A dívida pública em percentagem do PIB voltou a disparar para o máximo histórico de 134,9%, em 2020. Já o saldo orçamental das administrações públicas registou um ‘déficit’ elevado, de 5,8% do PIB. Após este tombo, em 2023, a economia portuguesa apresenta já sinais de recuperação. O rácio da dívida pública no PIB passou para 113,9% em 2002 e, recentemente, o Fundo Monetário Internacional mais do que duplicou a projecção de

The Bank of Portugal did the maths: between 2000 and 2020, average annual growth in real GDP per capita was only 0.3%. The years of the COVID-19 pandemic contributed strongly towards this poor figure. However, even when excluding them, average growth stood at 0.8% — a figure far distant to the annual average growth rate over the second half of the last century (3.9%). Even with this fairly insignificant growth, this does not mean everything is equal. After analysing the different sectors of activity in greater detail and their respective contributions to the production of wealth, the former Economy Minister, Pedro Siza Vieira, described how the profile of the Portuguese economy has changed. The weightings of construction and property declined in conjunction with financial services. On the other hand, tourism and the information and communication technologies have gained in importance. Industry grew on the back of exports, which attained a weighting of 50% in national GDP. In contrast, we may report that in 2003, sales to the exterior accounted for only around 28%. Examining the specific case, our economic dependence on tourism has intensified. The contribution of this sector to national GDP grew from 4.5% in 2003 to 10.9% in 2022. Even demonstrating promising signals, in order to get the economy growing, it is essential to cut the level of debt, whether of the public or the private sector, especially in a period of rising interest rates.

The rocky path of the public coffers

In the wake of the sovereign debt crisis that led Portugal to request an international bailout in 2011, public debt peaked at 132.9% of GDP in 2014. With Portugal emerging from the international financial bailout within the defined period of four years, it did prove possible to make significant progress in cutting the debt ratio that in 2019 had already fallen back to 116.6% of GDP. In this year, Portugal commemorated another feat in the public accounts with the state registering its first budgetary surplus in the history of Portuguese democracy: 0.1% of GDP. The Minister of Finance at the time, Mário Centeno, attributed this to the dynamics of the economy and the labour market that drove rising fiscal revenues and company contributions to the social security system. In fact, the country was able to drive down the unemployment rate from a historical peak of 17.1% in 2013 to less than a half. In 2022, this rate came in at 6.5%. Portugal benefitted from the accommodative monetary policy (quantitative easing) in effect at the European Central Bank through to mid-2022, which benefitted the national financial position as the ECB president stated in 2016 when appearing before MEPs: “The reductions in the ECB interest rate are to a large extend benefiting the vulnerable Eurozone countries and the fragmentation of financing costs and loan conditions in the different countries has decreased.”

The trajectory in the public coffers and the national economy appeared to be set for a rosy future, however, the COVID-19 pandemic brought an end to such prospects. The debt to GDP ratio once gain shot up to a historical maximum of 134.9% of GDP in 2020. In turn, the state registered

26

PORTUGAL

crescimento de Portugal para este ano (de 1% para 2,6%). Conseguiremos aproveitar estes ventos favoráveis para estabilizar o rumo do país e contrariar a ideia (confirmada nos últimos 20 anos) de que Portugal está condenado à cauda da Europa?

Além das crises, os motivos estruturais para a nota “medíocre” do país