THE ENTERTAINERS

Geometry of Life [Chapter 1]. A movie shot at Palazzo Molteni, Milan. moltenigroup.com / shop.molteni.it

Page 48 (clockwise): Portrait of Nicholas Aburn in his Paris apartment by Eduardo Cerruti and Stephanie Draime.

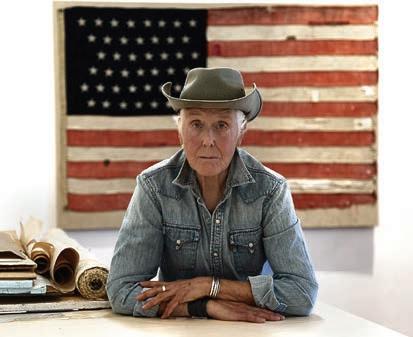

Portrait of Harmony Hammond by Grace Roselli.

Portrait of Dasha Zhukova by Anna Kozlenko.

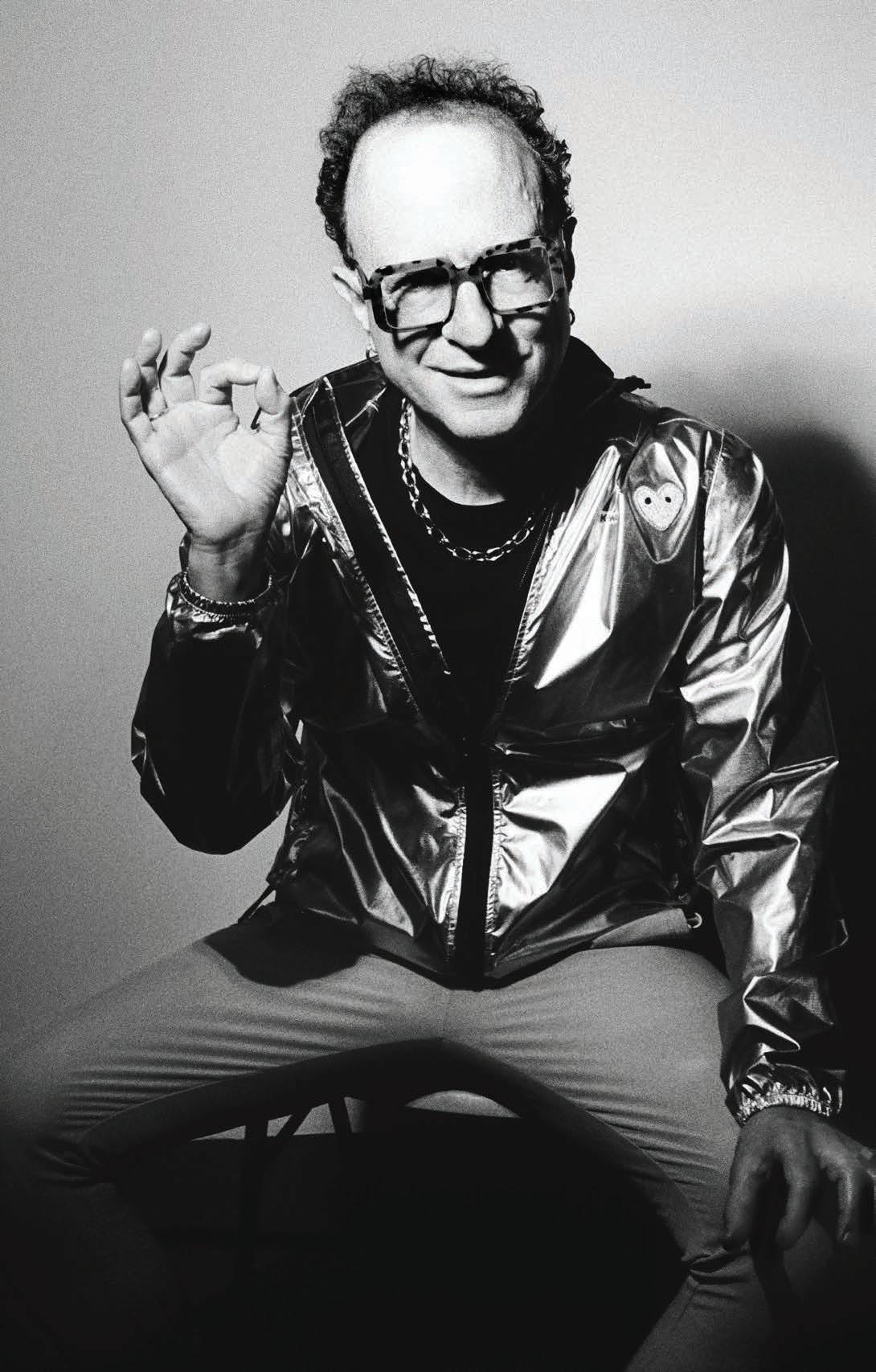

Portrait of Cayetano Ferrer by Max Cleary. Portrait of Wolfgang Tillmans by Pat Martin.

Page 52 (clockwise): Portrait of Marie Watt and Nick Cave at the Chicago studio of sculptor Richard Hunt by Alexa Viscius.

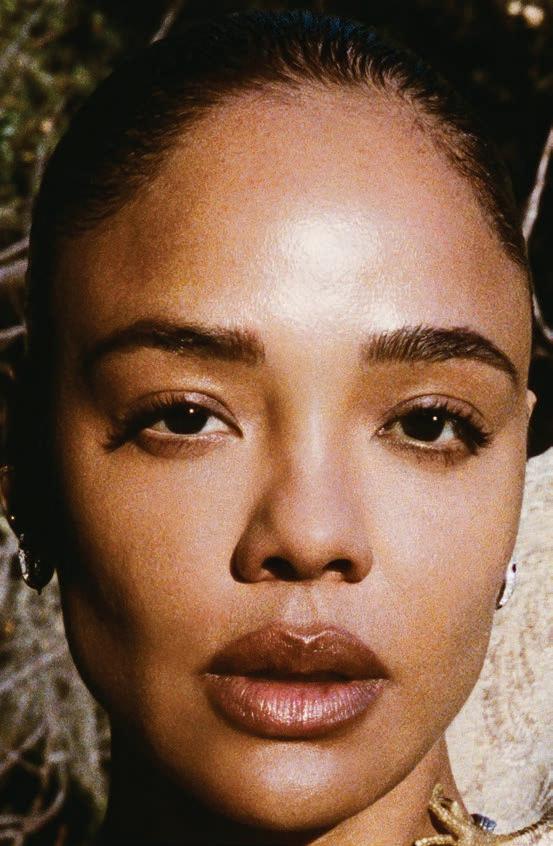

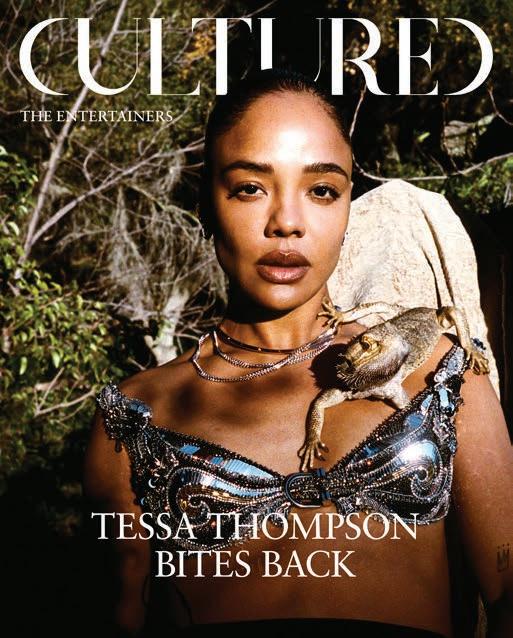

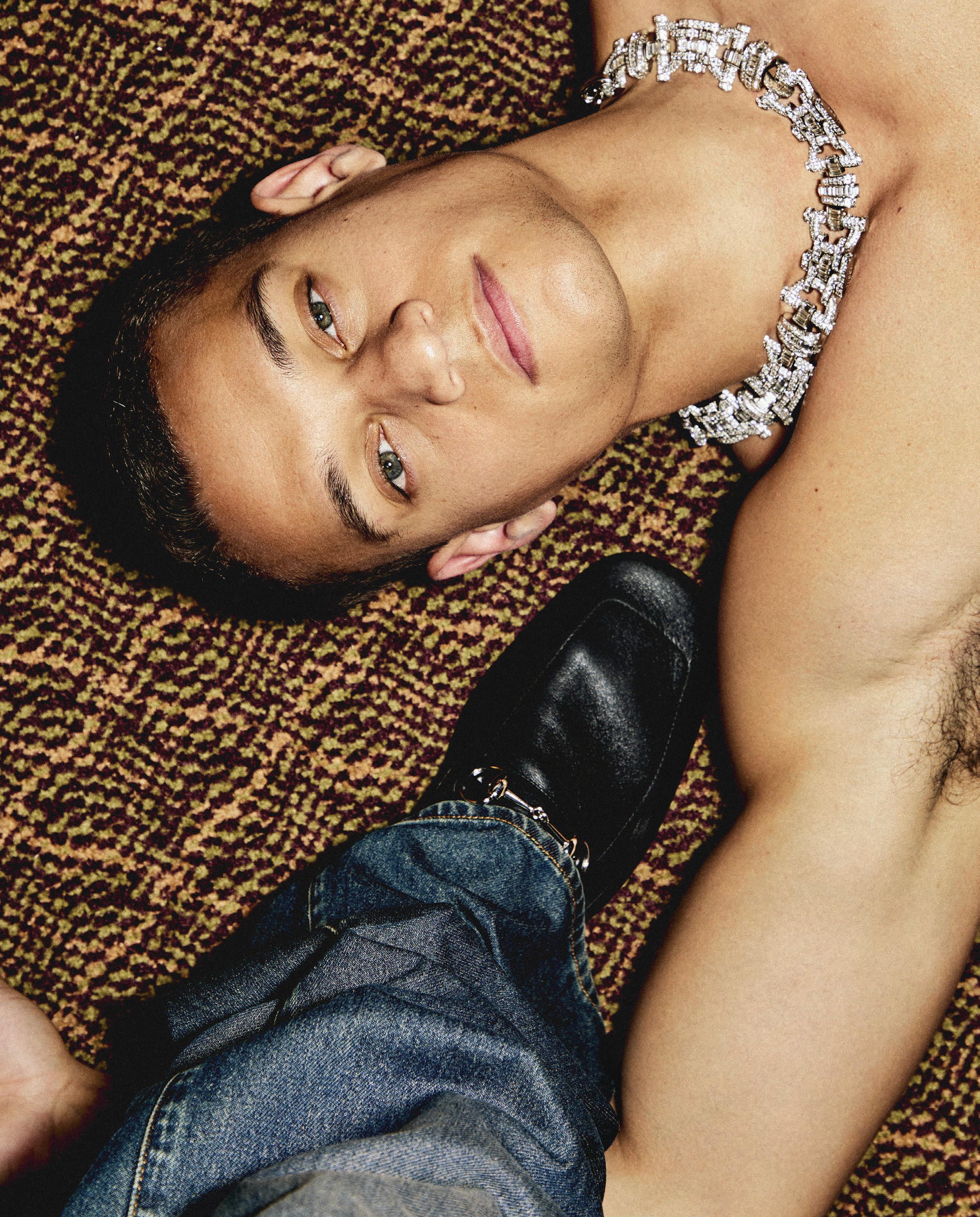

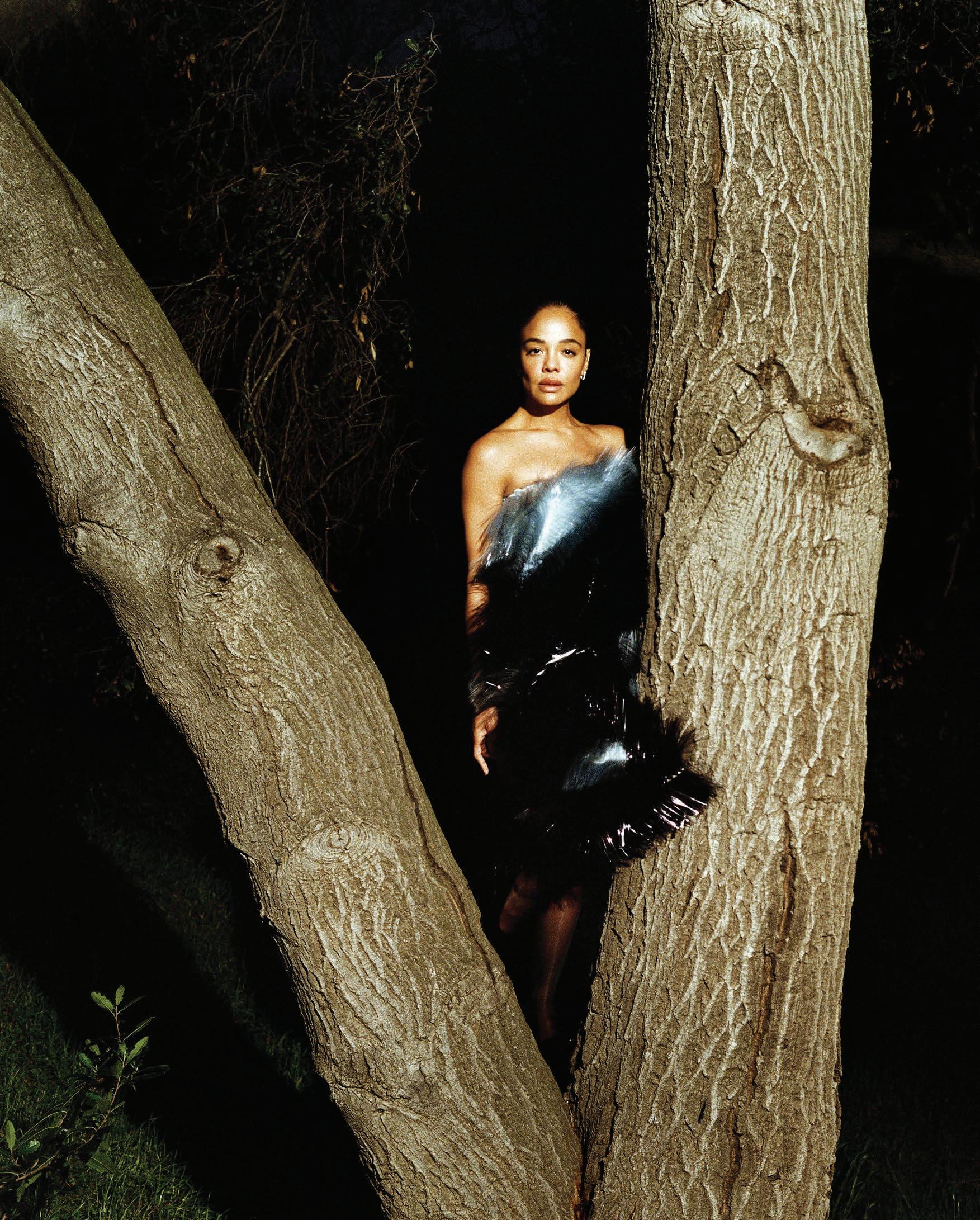

Portrait of Tessa Thompson wearing Dior and Cartier jewelry by Shaniqwa Jarvis.

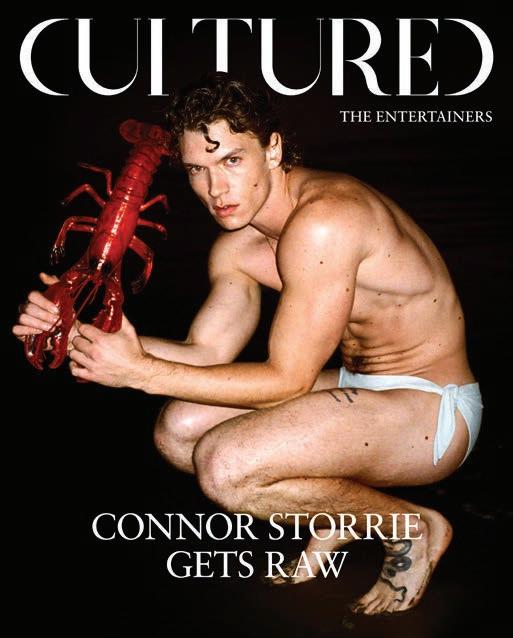

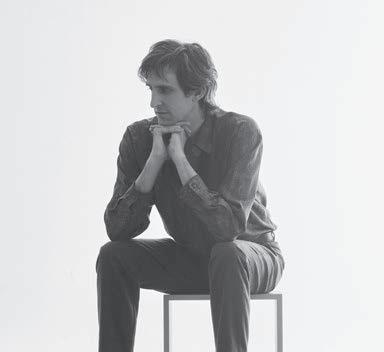

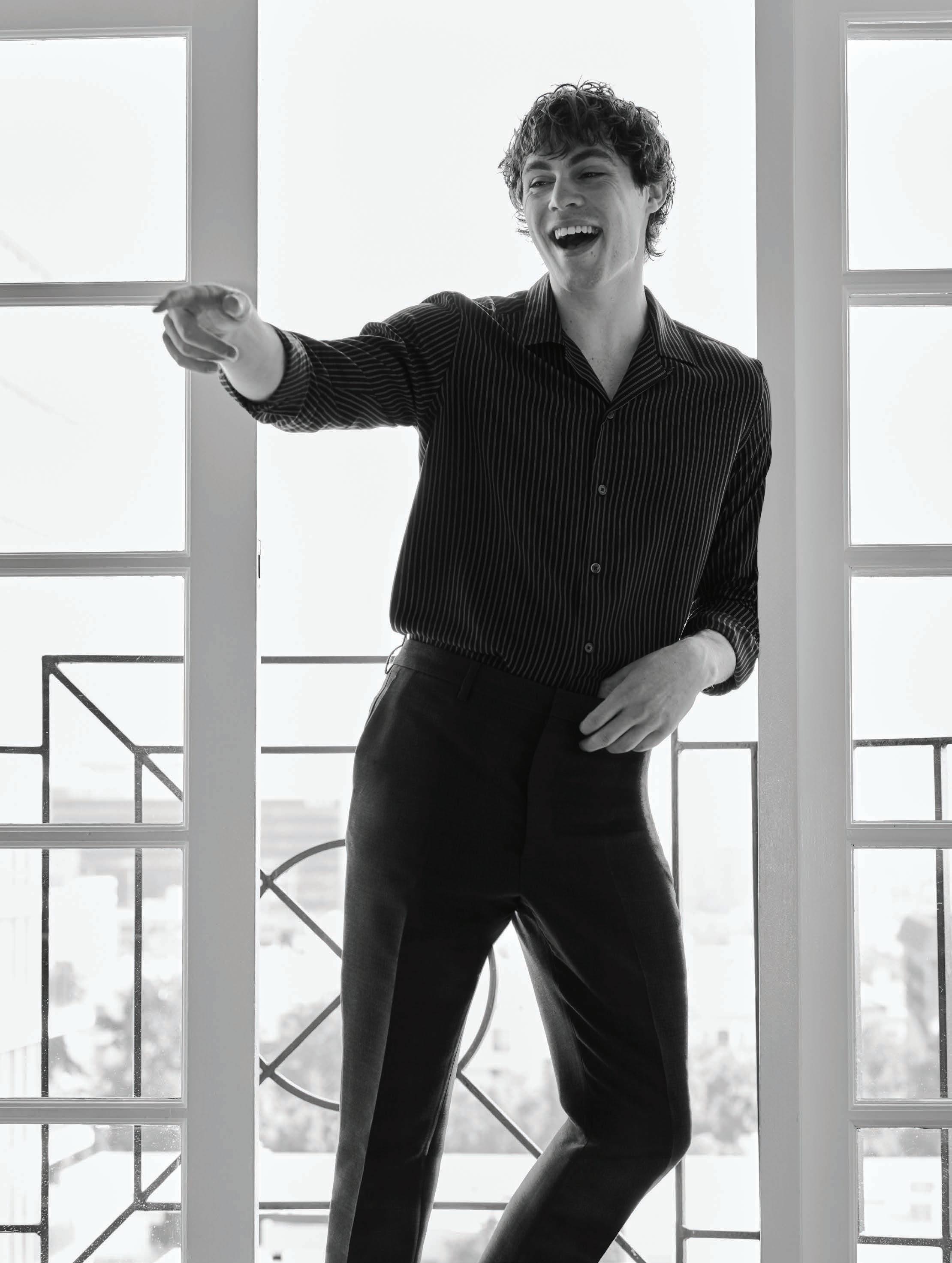

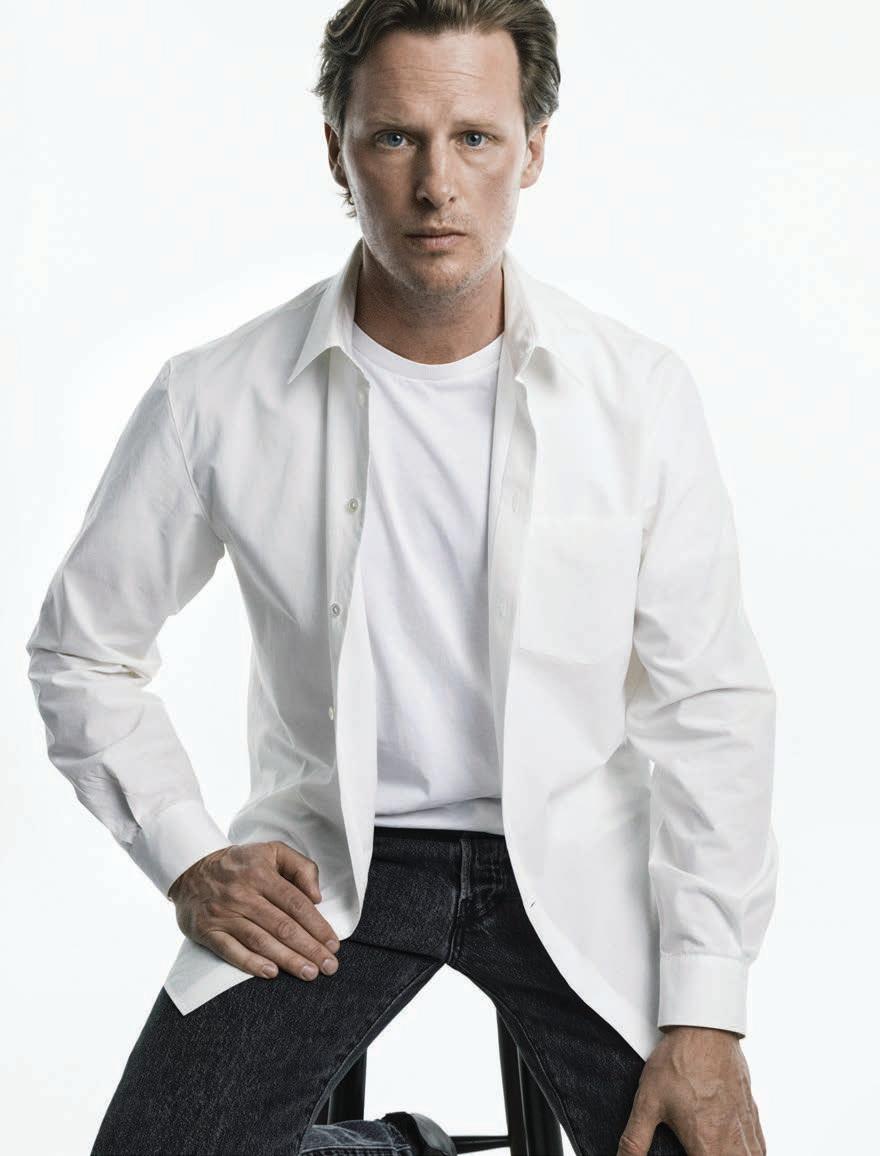

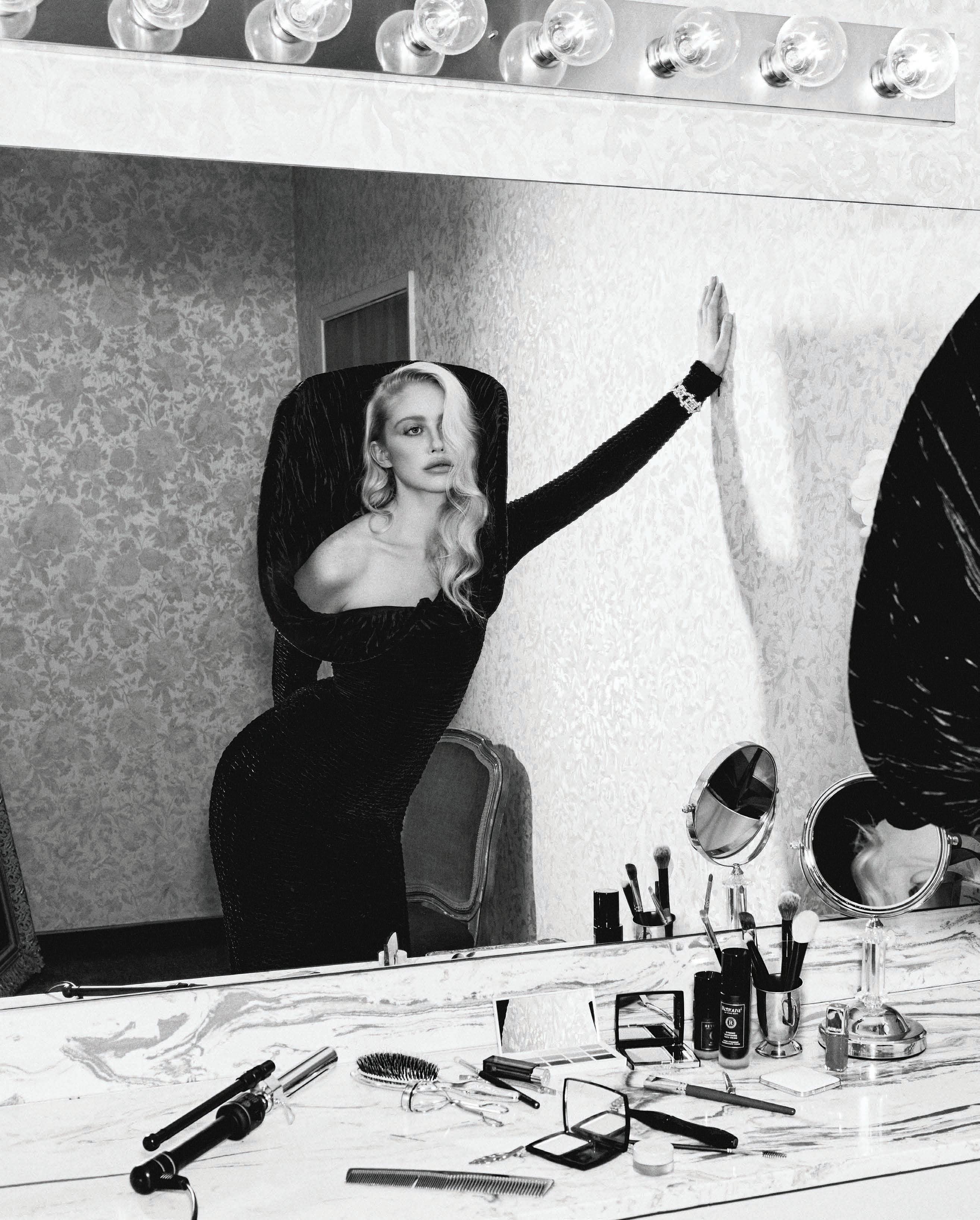

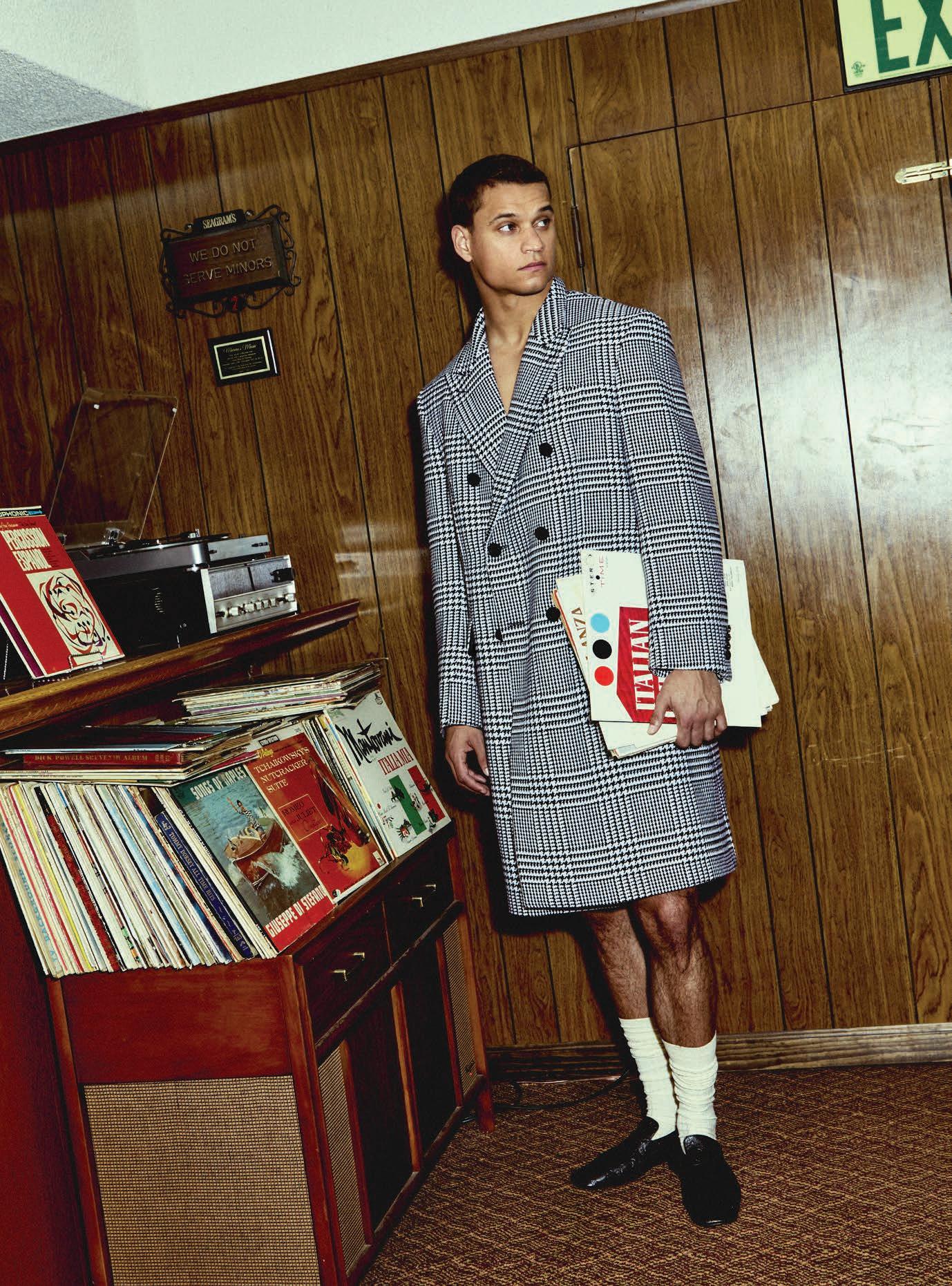

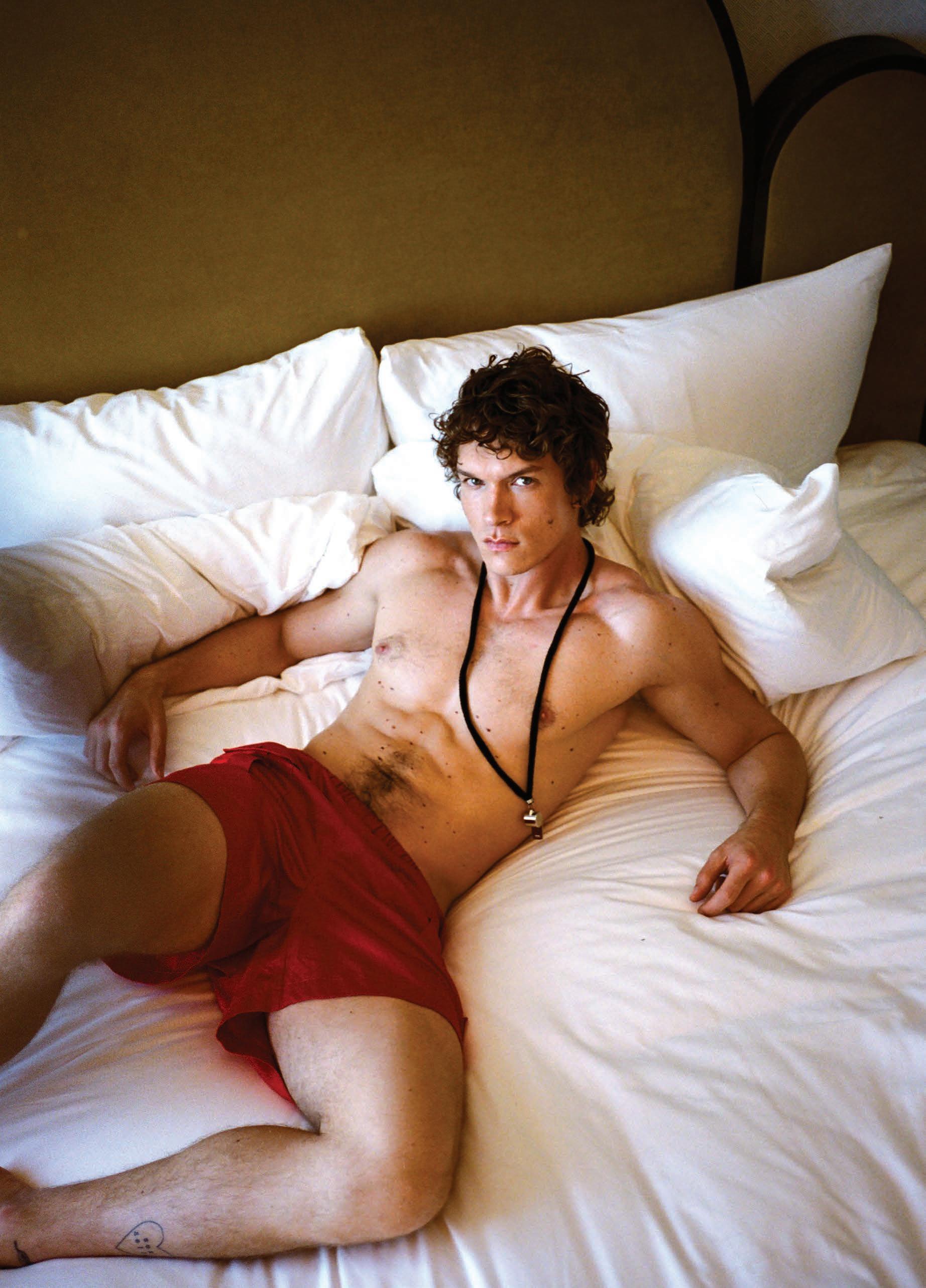

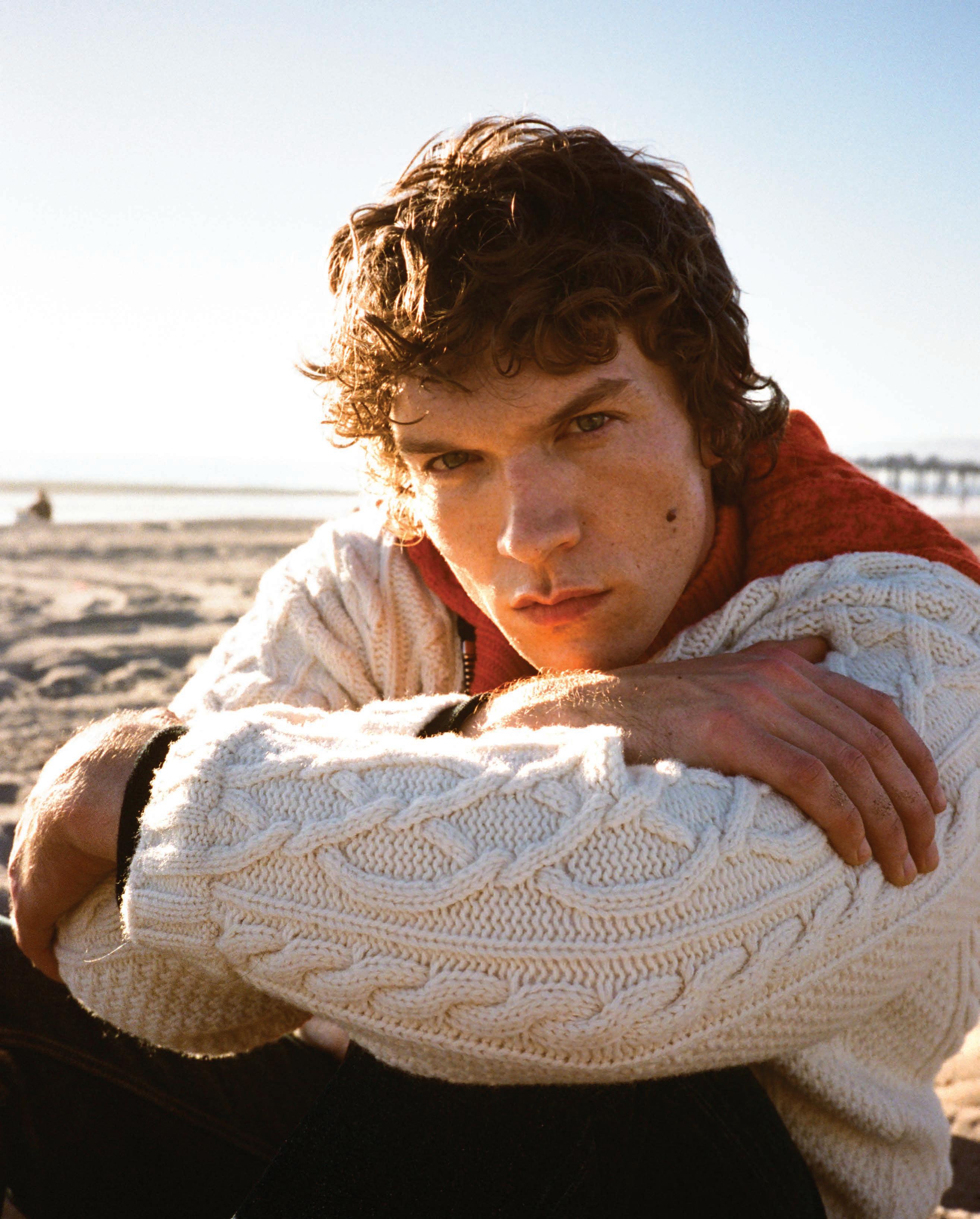

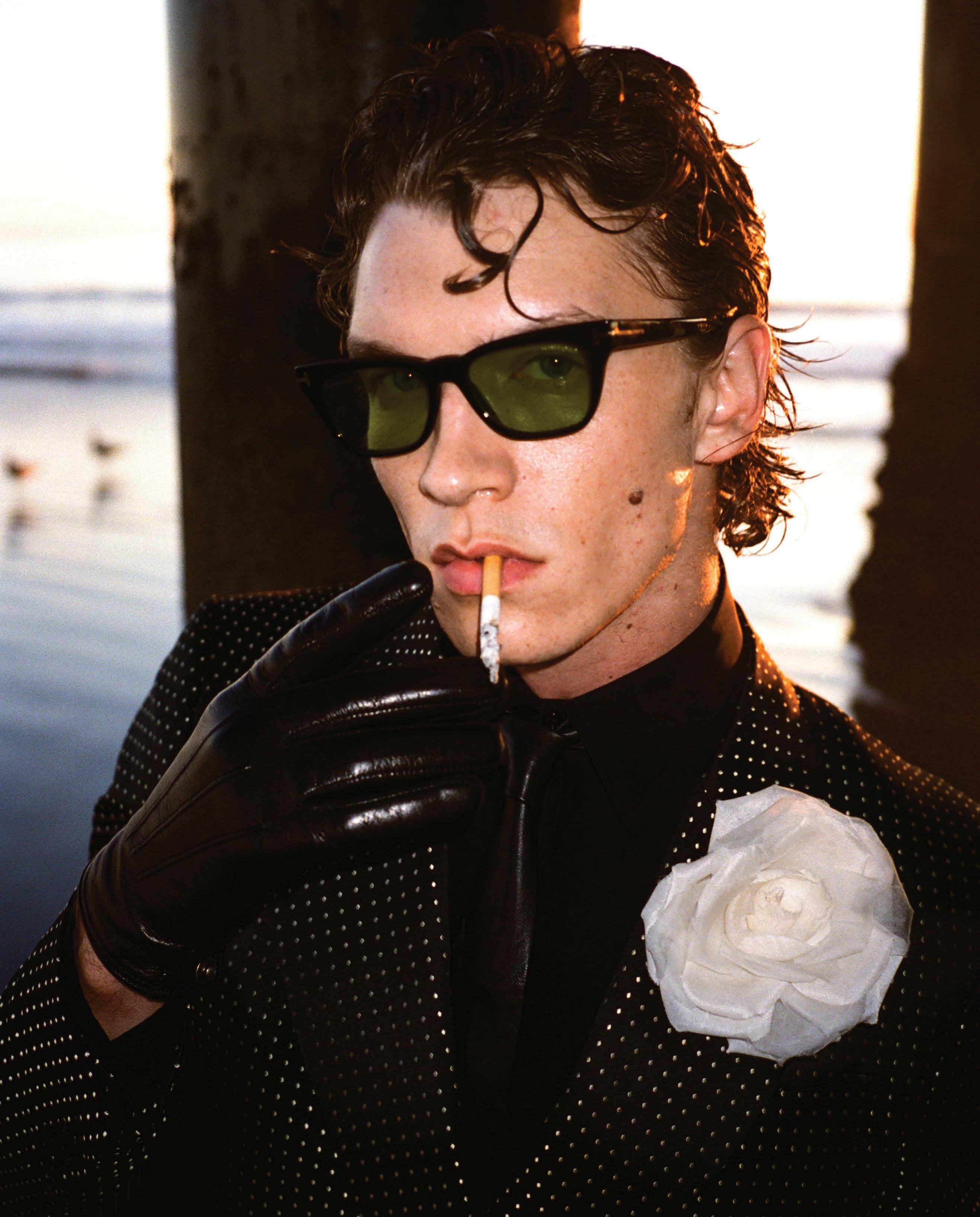

Portrait of Connor Storrie wearing Versace by Christian Coppola. Portrait of Sagar Radia wearing Wooyoungmi by Mary McCartney.

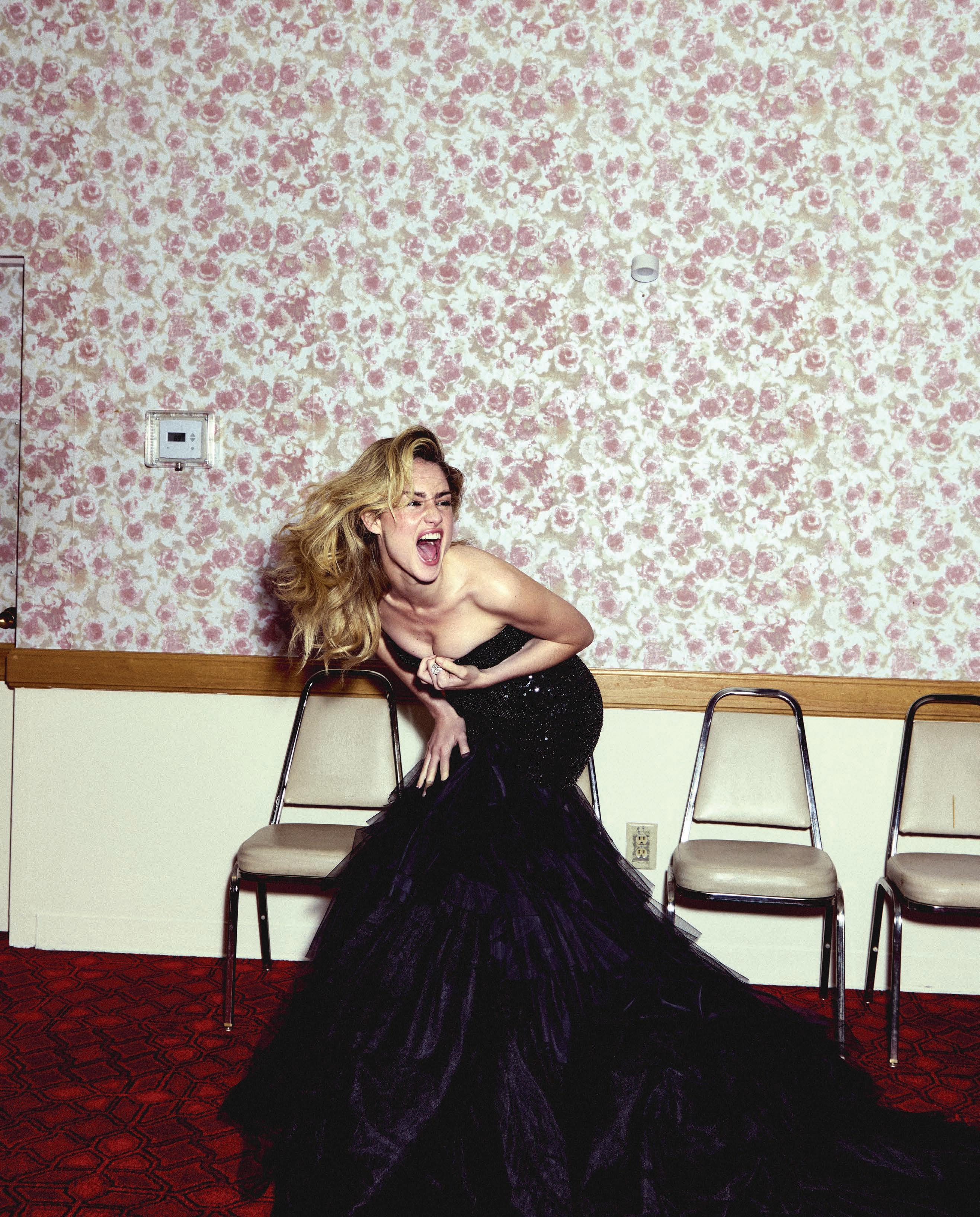

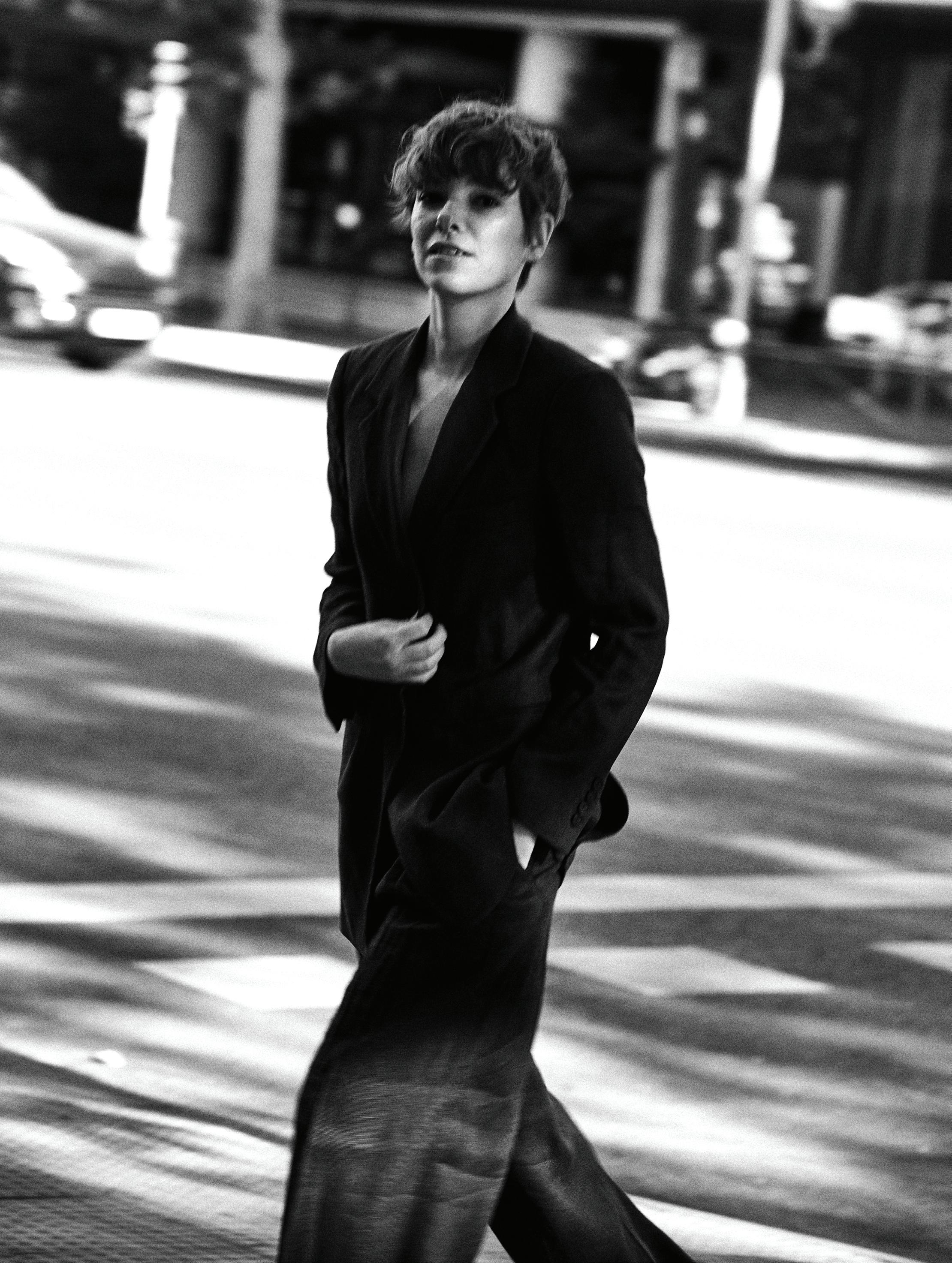

Page 54 (clockwise): Portrait of Eva Victor wearing Miu Miu by Kobe Wagstaff.

Amanda Precourt’s home with, left to right, Lauren Halsey, Untitled, 2021; Sterling Ruby, TURBINE. GABAPENTIN , 2022; and Otani Workshop, Standing rabbit , 2022. Photography by Yoshihiro Makino.

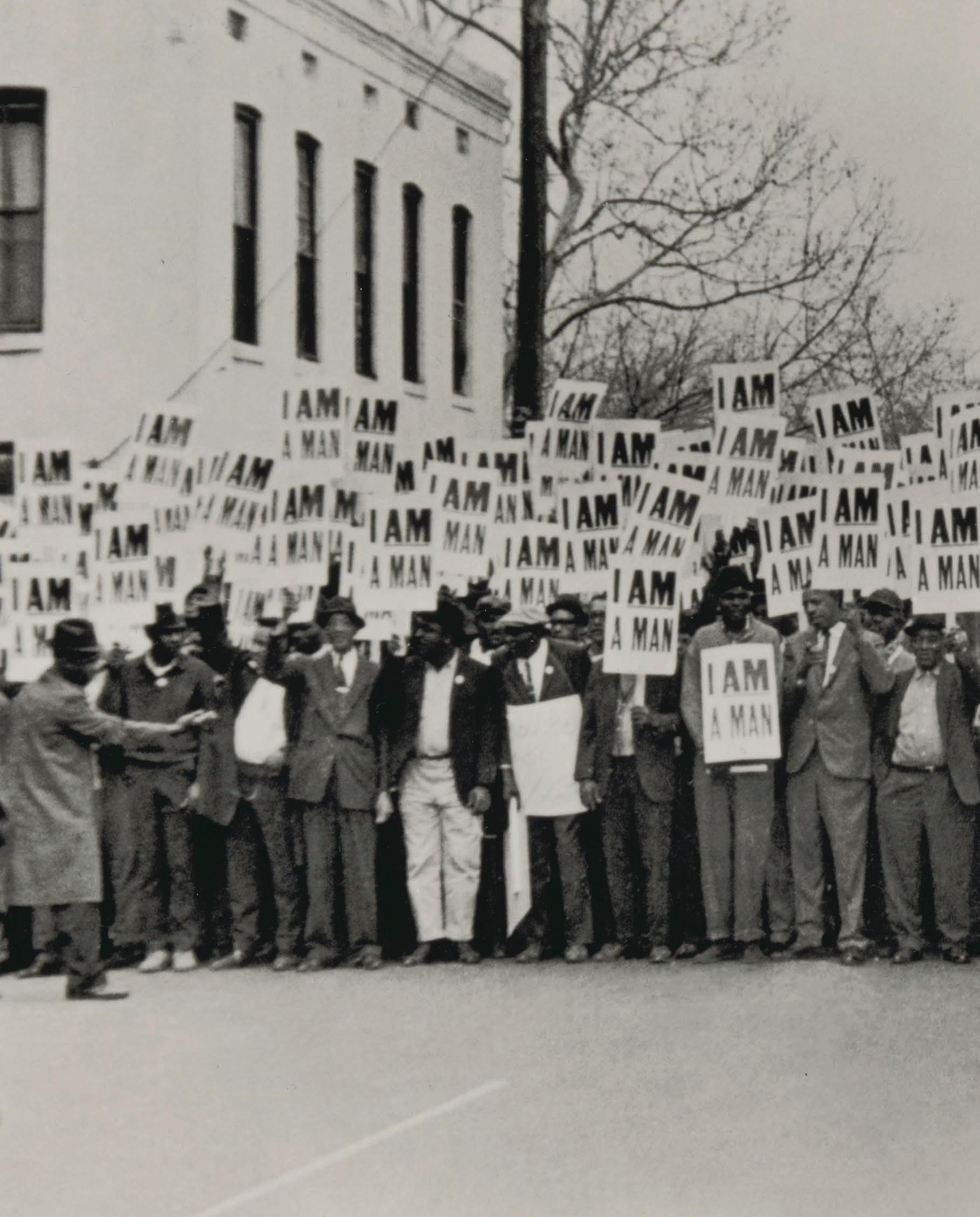

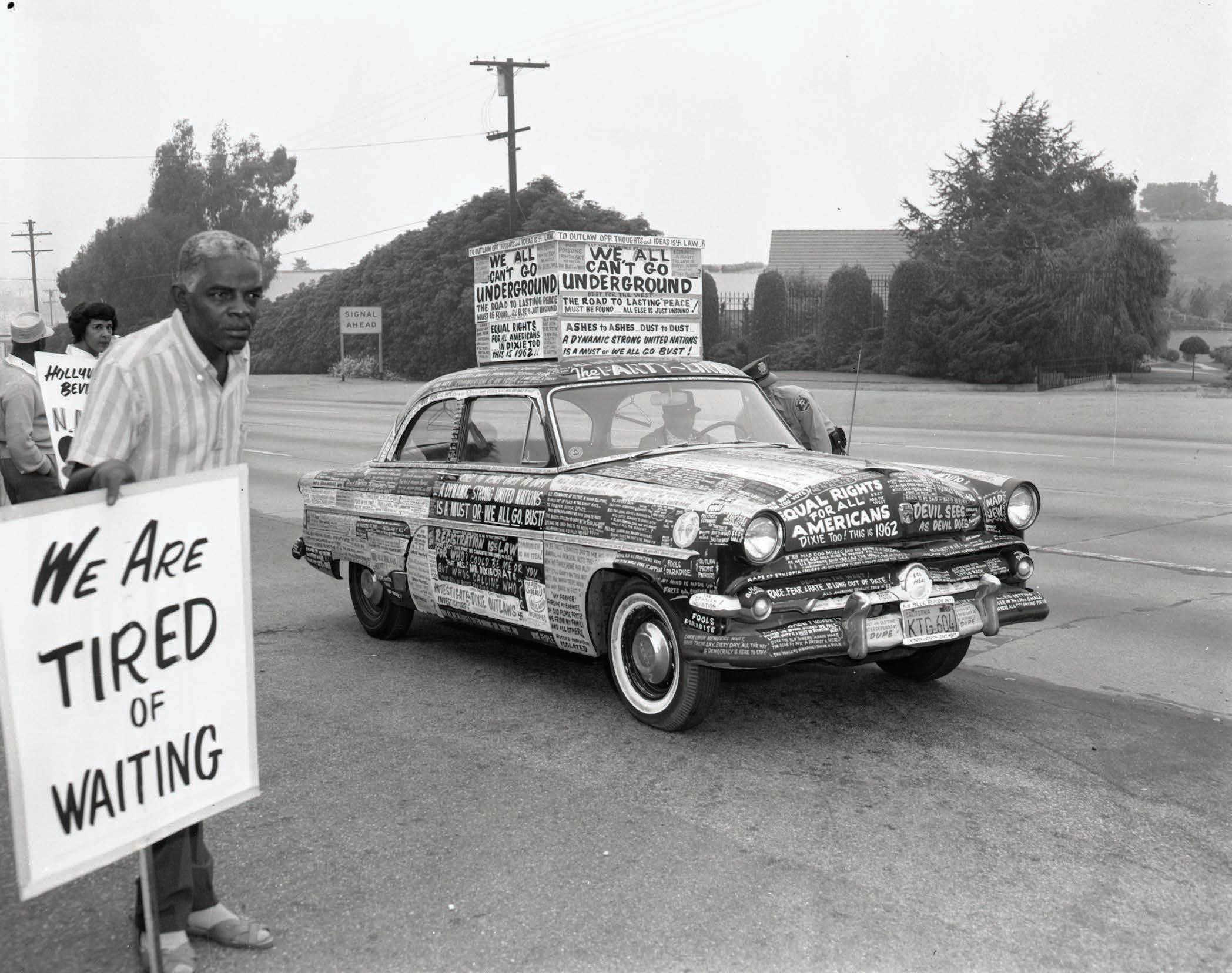

John W. Mosley, View of the Crowd as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Addresses Civil Rights Demonstrators at 40th Street and Lancaster Avenue, Philadelphia, August 3, 1965. Photography courtesy of the John W. Mosley Photograph Collection, Charles L. Blockson AfroAmerican Collection, and Temple University Libraries.

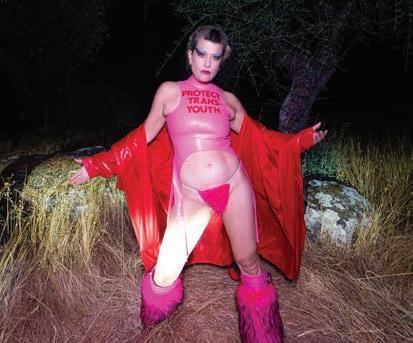

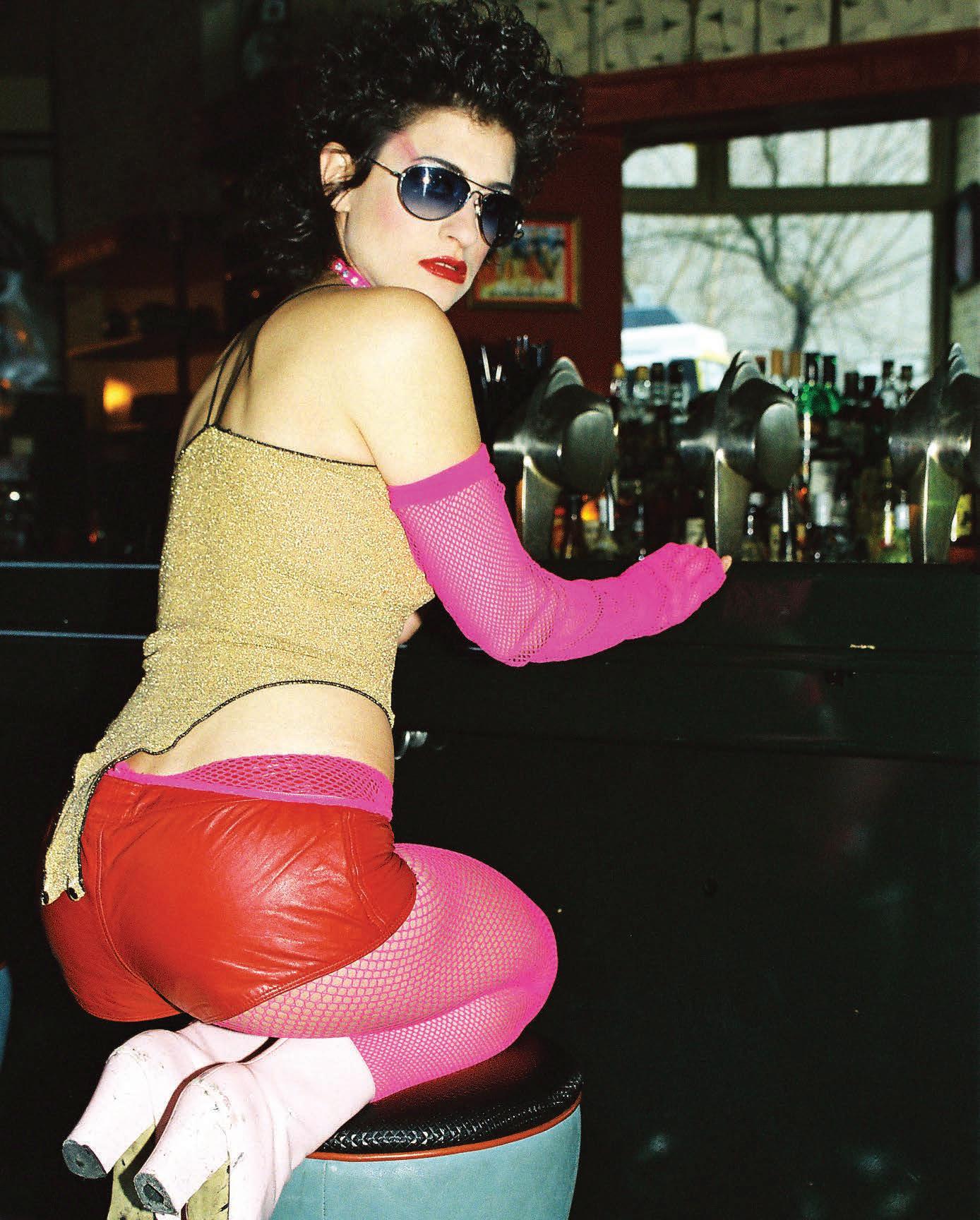

Portrait of Peaches by the Squirt Deluxe.

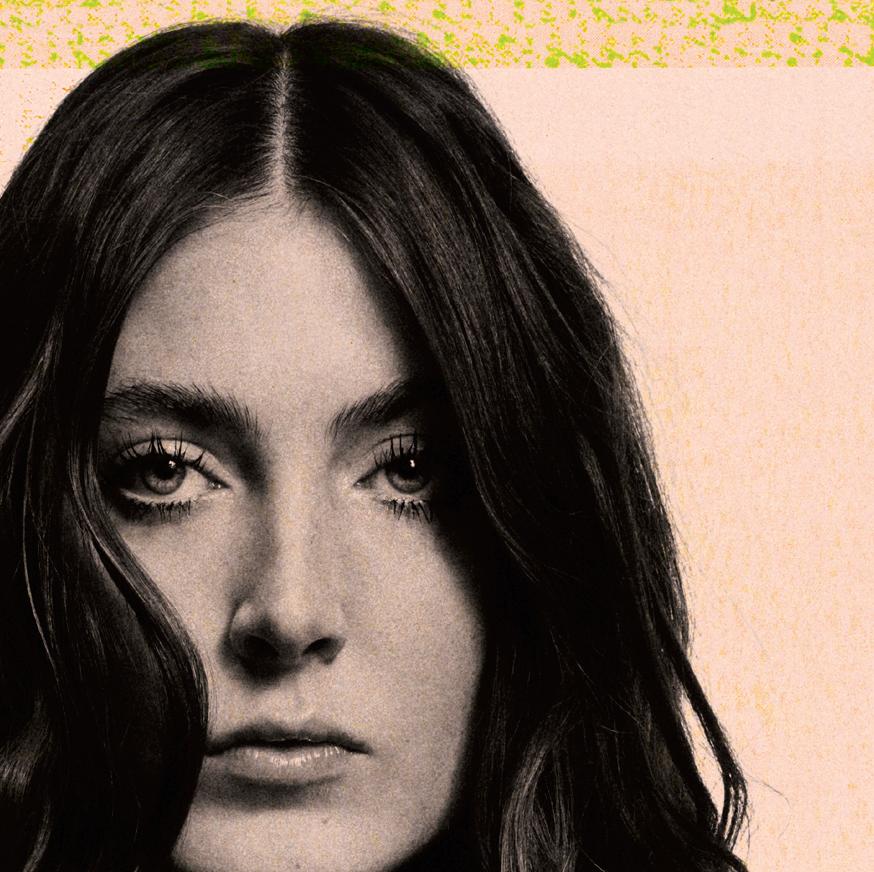

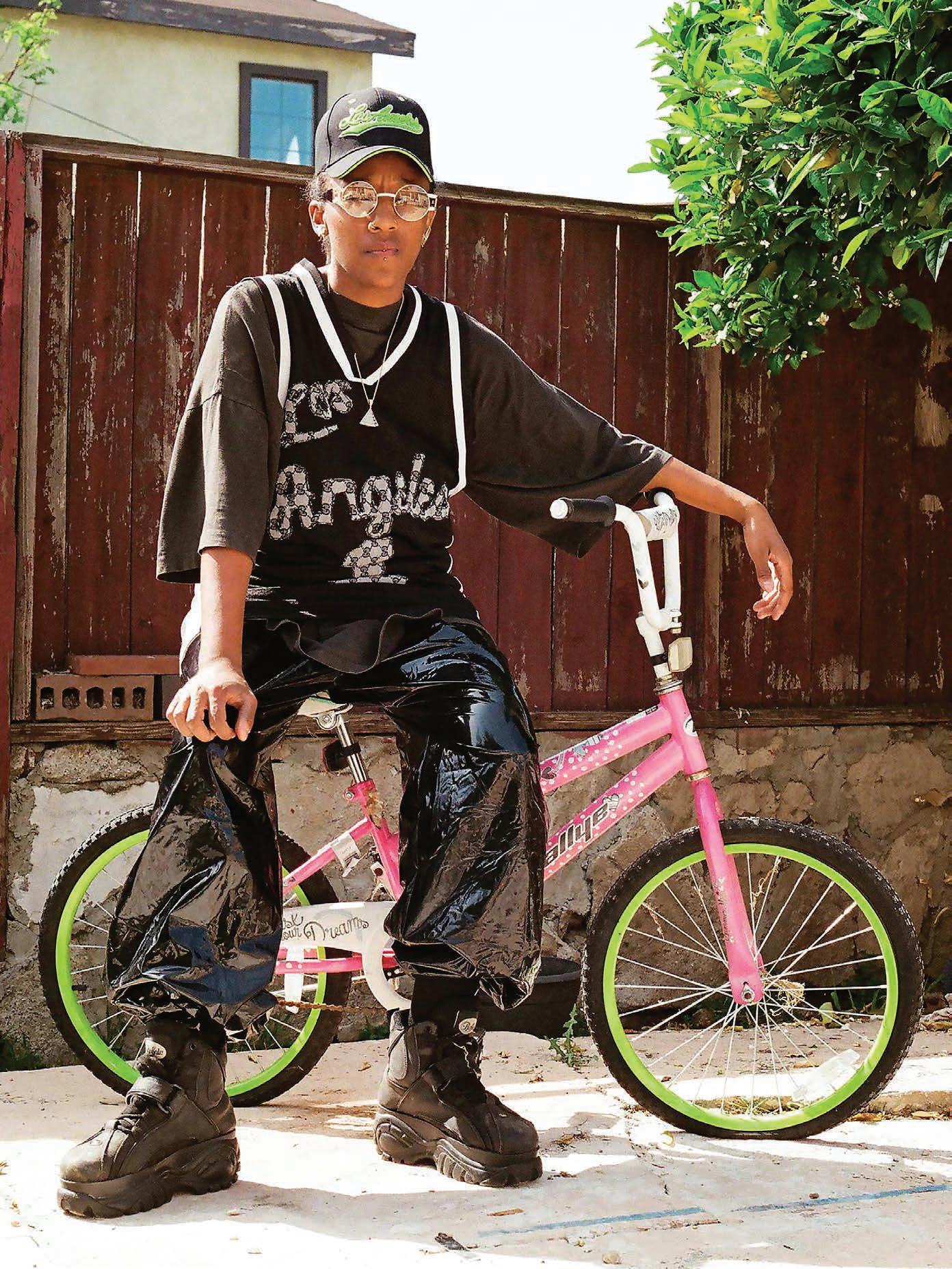

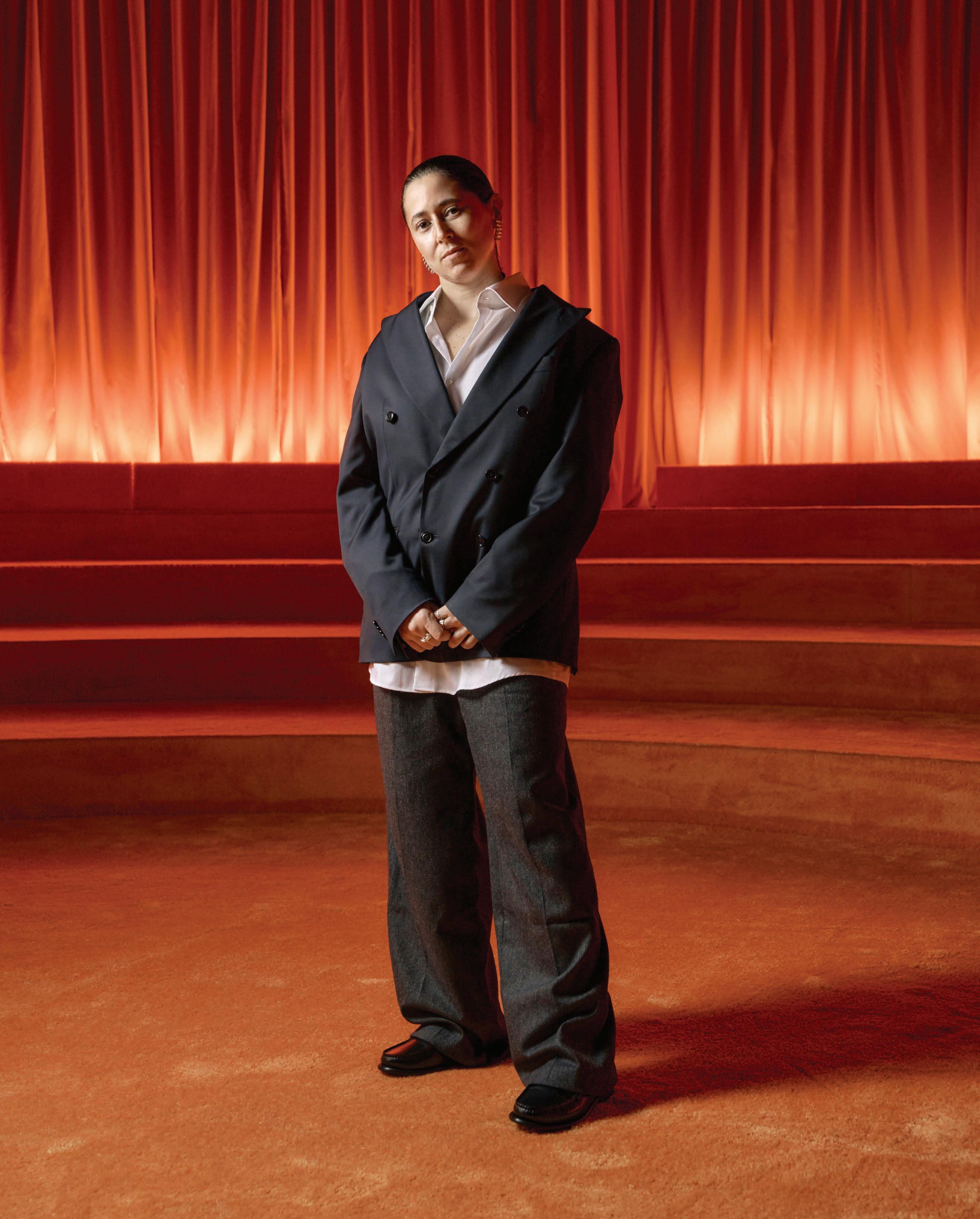

Portrait of Nia DaCosta wearing Gucci by Brad Torchia.

loropiana.com

We developed CULTURED’s 2026 Entertainers issue as a tribute to—and interrogation of—screens. Whether in theaters or in our hands, our screens continue to shape the way we live, the way we engage with art, and the way we understand (or, sometimes, misunderstand) ourselves and one another.

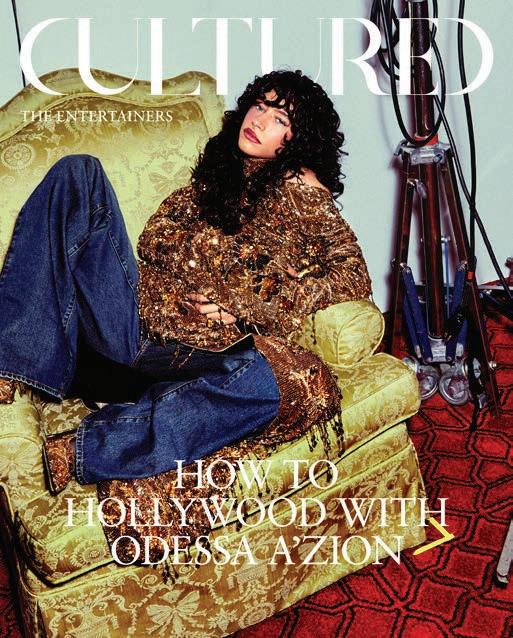

In our fourth annual Young Hollywood portfolio, seven rising stars under 30 —including cover star Odessa A’zion of Marty Supreme and I Love LA —reflect on their dreams of making it. Almost every one of them saw grappling with hyper-visibility as the biggest struggle they contend with while honing their crafts. Cover star Tessa Thompson, who we photographed on a sunny January day in Topanga Canyon, sits down with her longtime friend Janicza Bravo to catch her breath after a banner year of projects that have tested her mettle in front of the camera and beyond. Connor Storrie, another of the issue’s cover stars and one half of the jaw-dropping Heated Rivalry duo, reveals how the allpowerful algorithm catapulted him from anonymous waiter to global heartthrob in a matter of weeks.

Elsewhere in the issue, we speak with five female writers about what it’s really like to enter the IP machine by having your book adapted for film and television. We also consider the perplexing oeuvre of the digital art pioneer Paul Chan, who turned his back on the genre in an attempt to avoid screens while still making art that matters, and sit down with curator Udo Kittelmann and collector Julia Stoschek, who are staging a screen-heavy artistic parcours in Los Angeles this spring. Brooklyn Center for Theatre Research founder Matthew Gasda considers the migration of A-list celebrities from the screen to the stage, while Johanna Fateman calls up her old friend Peaches to dig into her first album in a decade—an ode to the political potential of horniness. In a perma-male industry, we also spotlight three filmmakers— Nia DaCosta, Mona Fastvold, and Eva Victor—who are upending expectations and garnering heavy awards buzz while they’re at it.

These artists all invite us to get lost in their work—and then, even more generously, o er us the opportunity to take a little bit of the humanity they model back with us into real life. And it’s no accident that you’re reading about them here—in print. In such unprecedented times, it feels more urgent than ever to bracket out some time and space to take one another in.

“Standing

with Dasha Zhukova on the empty floor of what will be the new space for the National Black Theatre was an incredible experience. I felt the power of the stage.”

THESSALY L a FORCE

“Over the

course

of a multi-day shoot, I got to know these young actors— very different from one another, I must say—and we dreamt up characters together.”

NOUA UNU STUDIO

“I

was interested in using our conversation as an entrypoint to explore Heated Rivalry ’s meteoric success—why it has hit a nerve for some viewers, raising questions around authenticity and representation.”

—ROB FRANKLIN

“As an admirer of Wolfgang Tillmans’s work and career, I hoped to make a memory he appreciated as well.”

—PAT MARTIN

Writer

There’s a new building going up in the New York neighborhood where Thessaly La Force spent her college years. In this issue, she speaks to the woman who built it. Ray Harlem, the latest project from developer and cultural mainstay Dasha Zhukova, contains a litany of luxury apartments and a reimagined National Black Theatre. “Standing with Dasha on the empty floor of what will eventually be the new space for the National Black Theatre was an incredible experience. I felt the power of the stage,” recalls La Force. Outside of CULTURED, the Iowa Writers’ Workshop alum has also contributed to publications including The New Yorker, The New York Times, and The Paris Review

Photographer

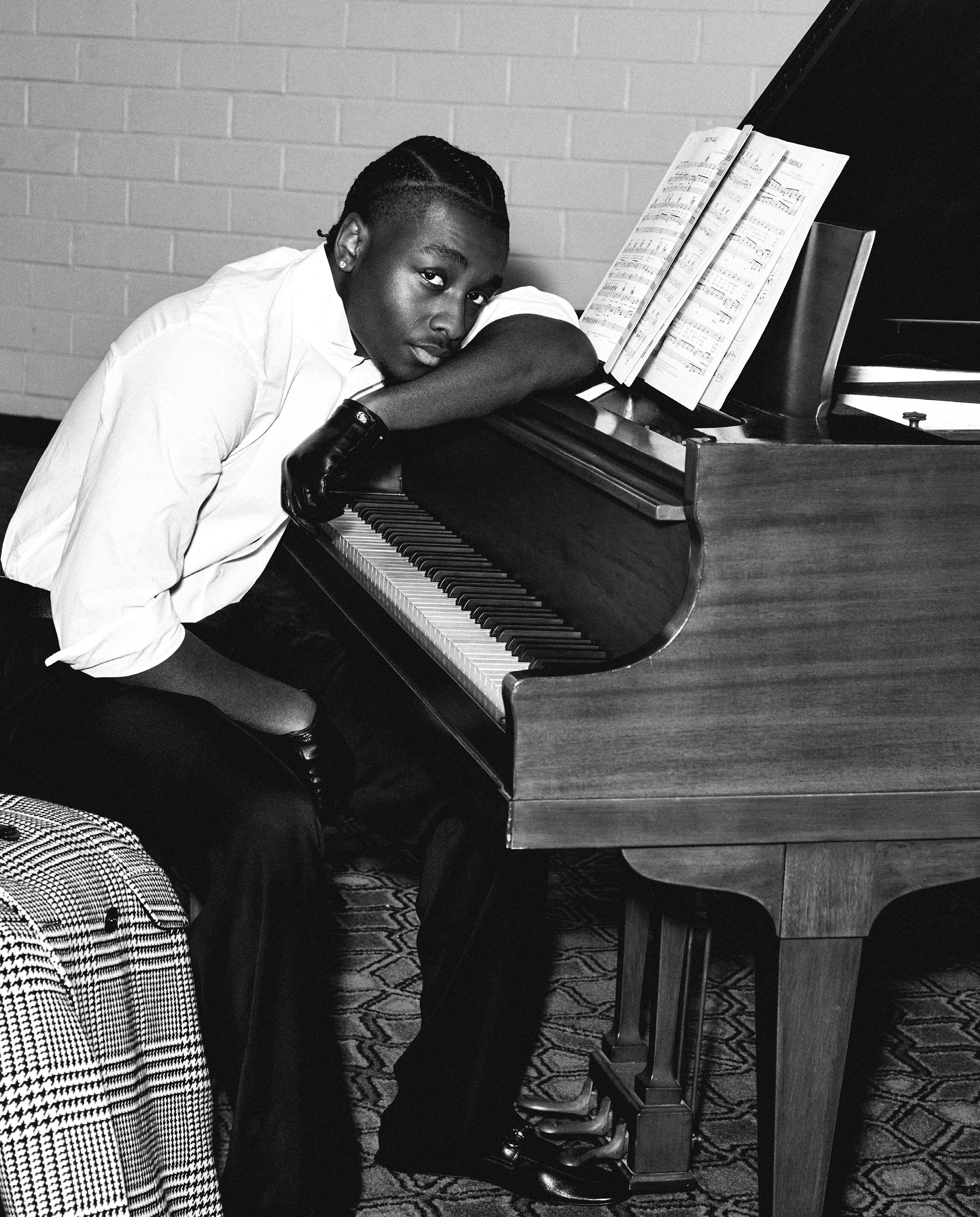

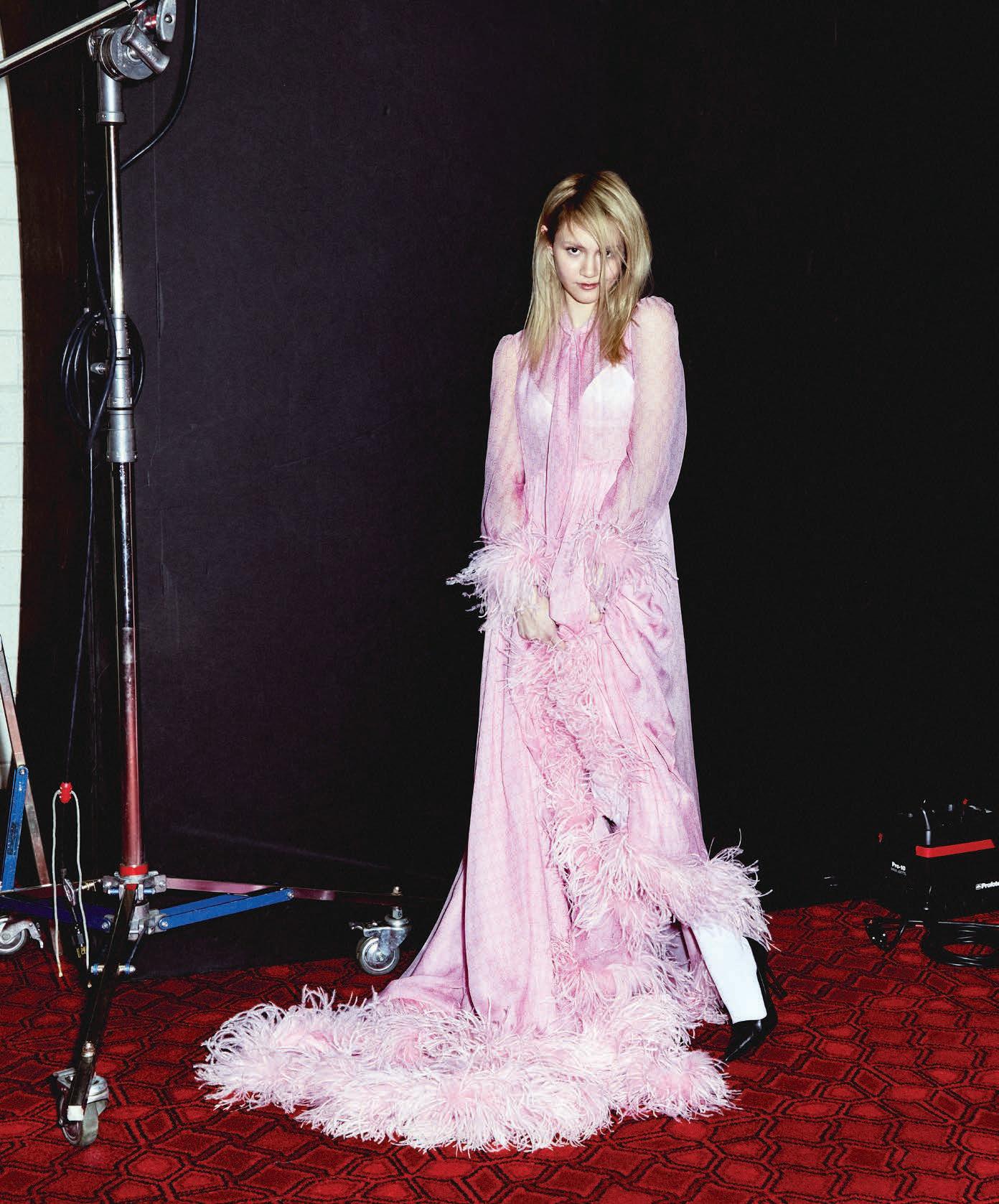

“It was LA’s answer to a Fellini-type daydream,” says Ian Markell of Noua Unu Studio, who shot a portfolio of rising actors for CULTURED’s fourth annual Young Hollywood portfolio. Following work with the likes of Calvin Klein, Rhode, and Vogue France, Markell teamed up with the magazine and Gucci to capture Odessa A’zion, Iris Apatow, Tyriq Withers, and more at an inflection point in their careers. “We created a red-carpet environment that was situated in the liminal space between a ’70s movie premiere and a night out at an Italian banquet hall in Napoli,” describes Markell. “Over the course of a multi-day shoot, I got to know these young actors—very different from one another, I must say—and we dreamt up characters together. It was a true collaboration.”

Writer

Few phenomena have permeated the cultural sphere quite as thoroughly as Heated Rivalry, the rom-dram series about two NHL players. And few writers could capture the whirlwind quite as precisely as Rob Franklin, who spoke with leading man Connor Storrie for one of this issue‘s cover stories. “I was excited to chat with Connor about his creative process and the dizzying experience of becoming famous overnight,” says Franklin, the author of last year’s bestselling novel Great Black Hope and an Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence nominee, “but I was equally interested in using our conversation as an entrypoint to explore why the show has hit a nerve for some viewers, raising questions around authenticity and representation.”

Werner Herzog, Nan Goldin, and Lenny Kravitz: Angeleno photographer Pat Martin’s documentarian lens has captured all three in a body of work that lines the walls of institutions like London’s National Portrait Gallery. For this issue, he caught Wolfgang Tillmans mid-install ahead of the German image-maker’s new exhibition at Regen Projects. “As an admirer of Tillmans’s work and career, I hoped to make a memory he appreciated as well. I brought us to the rooftop of the gallery, overlooking Hollywood on a warm afternoon. We shared stories about intimate portraits. I found he was as comfortable in front of the camera as behind, and had a refreshing sense of humor.”

David Zwirner

“We shot these photos in a small pocket of Santa Monica crawling with tourists, none of whom recognized Connor Storrie.”

CHRISTIAN COPPOLA

“When CULTURED assigned me to look at his legacy and influence on other artists, I borrowed a stack of very heavy books from the New York Public Library and got busy.”

HELEN STOILAS

“It’s the grand experiment of the modern art museum to keep up with new developments while also maintaining the canon.” —TRAVIS DIEHL

“Tessa Thompson and I have a connection that allows us to create beautiful, fearless imagery.”

SHANIQWA JARVIS

Photographer

“It’s rare to see a complete unknown shoot to stardom like this,” says Christian Coppola, “especially when nobody really sees it coming.” For this issue, the filmmaker and photographer joined Heated Rivalry star Connor Storrie at Santa Monica Pier for a sensual shoot by the water. “Before the cottage and the meteoric rise, we shot these in a small pocket of Santa Monica crawling with tourists, none of whom recognized him,” the photographer recalls. “If we did this all over today, that wouldn’t be the case. Shooting him felt like standing in a clean, bright waiting room right before someone calls your name and your life changes forever.” Coppola has shot Nicole Kidman, Javier Bardem, and Kyle MacLachlan for publications including Vogue and Interview

Writer

“‘Is that art?’ is a question I’ve asked and been asked a lot,” says Helen Stoilas, a writer for more than 20 years and former editor at The Art Newspaper. “But I’ve never had the chance to do a deep dive into the work of Marcel Duchamp, an artist who pushed people to think about just that for most of his career. So when CULTURED assigned me to look at his legacy and influence on other artists, I borrowed a stack of very heavy books from the New York Public Library and got busy. What has always surprised me is how people continue to cite an artist whose most famous works were made more than 100 years ago. Getting to interview the contemporary artists Jill Magid, Cory Arcangel, Darren Bader, and Maya Man about how their work further expands the definition of art was an art geek’s dream.”

Writer

Why are so many arts institutions showing work by dead artists? Travis Diehl examines an institutional trend toward the grave, sparked by retrospectives focused on Wifredo Lam, Roy Lichtenstein, and more, in this issue. “It’s the grand experiment of the modern art museum to keep up with new developments while also maintaining the canon,” says the writer. “That’s hard to do, on the level of math alone.” Outside of CULTURED, Diehl has covered the Joe Rogans of the art world, the industry’s onslaught of self-censorship, and the nostalgic potential of A.I. for publications including The New York Times, Frieze, and The Guardian

Shaniqwa Jarvis has shot projects across the world for clients including Jil Sander, Rolling Stone, and Louis Vuitton. For this issue, she met her friend Tessa Thompson in Topanga Canyon for a freewheeling (and quite muddy) cover shoot. “Tessa and I have a connection that allows us to create beautiful, fearless imagery,” says Jarvis. “I wanted to photograph her as she truly is: an artist, a gorgeous human with incredible personal style and deep care for all of us. There’s no one else I’d roll around in a manure-packed meadow with to get the shot.”

“In Nicholas Aburn’s 19th-century Parisian apartment, our conversations circled the intimacies of making a home with our partners.” —EDUARDO CERRUTI and STEPHANIE DRAIME

“The sun was shining for us, the Prince Albert pub in West London was our location. Sagar Radia had great energy and really performed well in front of the camera.”

—MARY

M c CARTNEY

“I hope to contribute in a modest yet meaningful way to the ongoing dialogue and vitality of their creative community.”

YOSHIHIRO

MAKINO

“We had 180 people in a room we’d set out 100 seats for.” MATTHEW GASDA

Photographers

When Balenciaga alum Nicholas Aburn was announced as Area’s new creative director last year, there was a rush to learn more about the low-profile designer. His first runway show offered a preview of what the line will look like under his tenure, and now, an intimate visit to his Paris home has given CULTURED insight into the rising designer’s inner world. The magazine enlisted photographer couple Eduardo Cerruti and Stephanie Draime, who have shot for the likes of Bode and Nike. “In Nicholas’s 19th-century Parisian apartment,” they recall, “our conversations circled the intimacies of making a home with our partners.”

Photographer

Industry has turned the adrenaline-fueled life of investment bankers into prime-time entertainment, and manning the desk in all four seasons of the hit show is Sagar Radia, photographed by Mary McCartney for this issue. It was, she notes, her “first portrait shoot of the year on Monday the 5th of January. The sun was shining for us, the Prince Albert pub in West London was our location. Sagar had great energy and really performed well in front of the camera.” A mainstay of the city’s art scene, McCartney’s work is held in collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum, National Portrait Gallery, and the Royal Academy. After spending the afternoon at the pub with Radia, McCartney admits she did what anyone would do: “I then went home and binge-watched the new season of Industry.”

Photographer

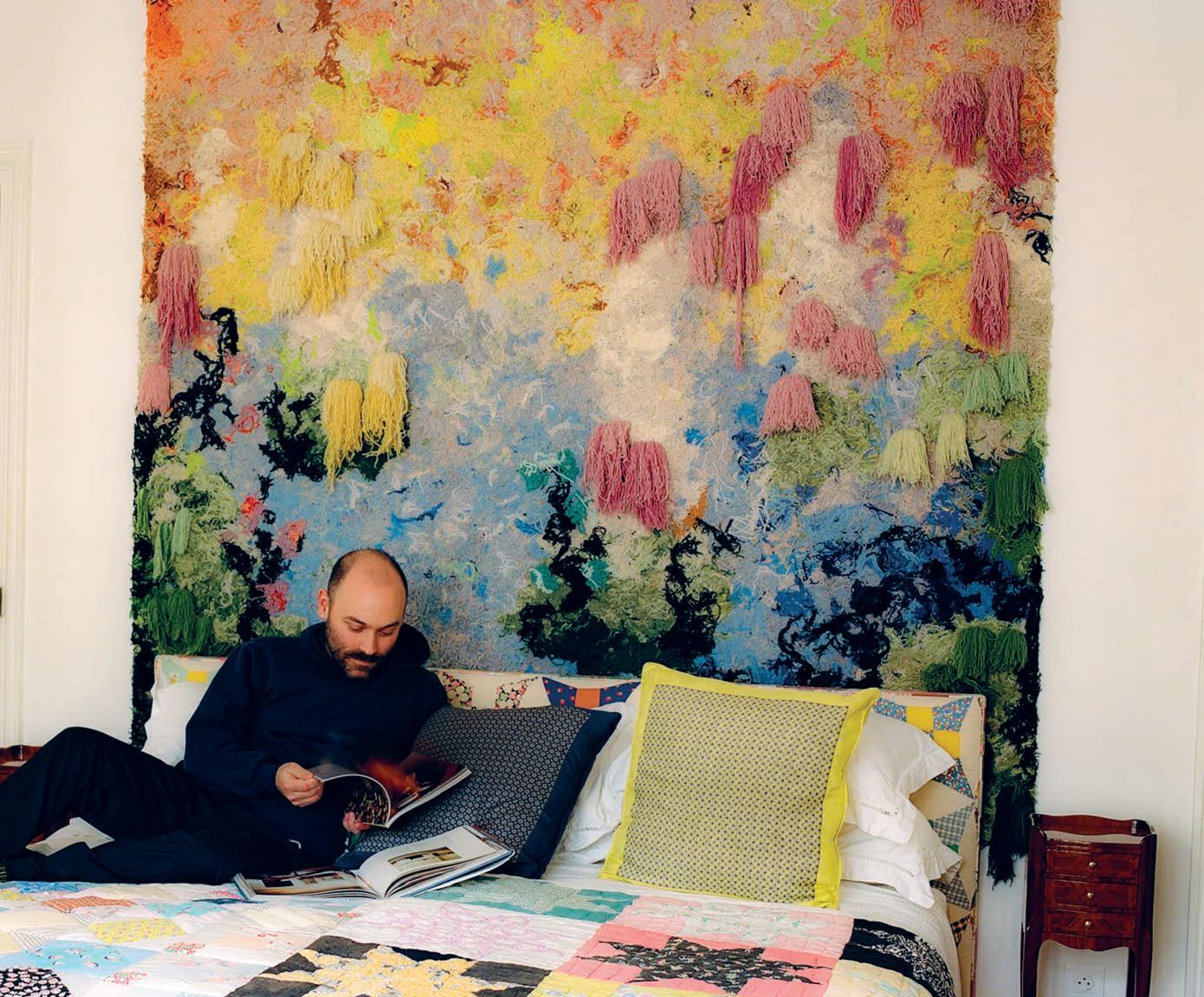

Self-taught Tokyo photographer Yoshihiro Makino got his start by documenting his city’s underground street culture in his late teens, and held his first solo exhibition at 19. A jump to Los Angeles broadened his scope to encompass the West Coast’s contemporary art, architecture, and interior design creatives. For this issue, Makino joined arts patron Amanda Precourt in Denver to discover the local scene she’s helped foster just a few states over. “In photographing her and her partner Andrew’s project, Cookie Factory, a hybrid of gallery and private residence,” says Makino, “I hope to contribute in a modest yet meaningful way to the ongoing dialogue and vitality of their creative community.”

Is the heyday of prestige television already over? Matthew Gasda makes a good case for calling time of death in this issue, turning his focus instead to the theater’s recent reinvigoration—and all the A-listers making the move to its stages. A playwright himself, Gasda is known for dialogue-sparking shows like Dimes Square and Doomers, and for founding the Brooklyn Center for Theatre Research. Between a flurry of opening nights, meetings with film studios, and interviews with the likes of Mark Ruffalo for this piece, he’s seen excitement swing from one pole to the other. “Closing night of Dimes Square (the 2024-25 reboot) at the Bench in Chinatown was one of the best nights of my life in the theater,” he recalls of the groundswell of support. “We had 180 people in a room we’d set out 100 seats for.”

MAR 8–AUG 23

Founder & Editor-in-Chief SARAH G. HARRELSON

EDITORIAL

Executive Editor, MARA VEITCH

Senior Editor, ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

Editor-at-Large, JULIA HALPERIN

Associate Digital Editor, SOPHIE LEE

Assistant Managing Editor, KARLY QUADROS

Assistant Editor, SAM FALB

Digital Coordinator and Junior Video Editor, PALOMA BAYGUAL

Copy Editors, EVELINE CHAO & MEGAN HULLANDER

Editorial Interns, EVE EISMANN, MILA DIAZ, DELANEY KIM, MOKSHAA SHIVLANI

The Critics’ Table

Co-Chief Art Critic and Commissioning Editor, JOHANNA FATEMAN

Co-Chief Art Critic and Consulting Editor, JOHN VINCLER

Critics’ Table Contributors

BLAKEY BESSIRE, PAIGE K. BRADLEY, BRIAN DROITCOUR, JARRETT EARNEST, JULIANA HALPERT, WILL HARRISON, SHIV KOTECHA, ZITO MADU, WHITNEY MALLETT, DAVID RIMANELLI, KATE ZAMBRENO

Editors-at-Large

Arts Editor-at-Large, SOPHIA COHEN

Fashion Directors-at-Large, ALEXANDRA CRONAN & KATE FOLEY

Style Editor-at-Large, JASON BOLDEN

Columnists & Contributors

Cultural Columnist, JAMIESON WEBSTER

Contributing Art Market Writer, RALPH D eLUCA

Contributing Architecture Editor, KAREN WONG

Food Editor, MINA STONE

Culinary Columnist, SAMAH DADA

Books Editor, EMMELINE CLEIN

New York Arts Editor, JACOBA URIST

Travel Columnist, ROBERT GOFF

European Contributor, GEORGINA COHEN

Contributing Fashion Editor, ALI PEW

Beauty Editor, EMILY DOUGHERTY

Vice President, Chief Revenue Officer, CARL KIESEL

Director of Brand, IAN MALONE

Vice President, Fashion, MICHAEL RIGGIO

Vice President, Sales, LORI WARRINER

Director of Brand Partnerships, DESMOND SMALLEY

Director of Marketing, SARA ZELKIND

Marketing and Sales Associate, HAILEY POWERS

Sales Consultant Home + Travel, PRIYA NAT

Prepress/Print Production, SHAPCO PRINTING INC.

Public Relations, ETHAN ELKINS, DADA GOLDBERG

Strategic Consultant, CAROL SMITH

Art Direction, EVERYTHING STUDIO

Social Media Director, KRISTIN CORPUZ

Junior Graphic Designer, AHIMSA LLAMADO

Social Media Intern, LAYLA HUSSEIN

ADVERTISING

Advertising@culturedmag.com

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Hailey@culturedmag.com

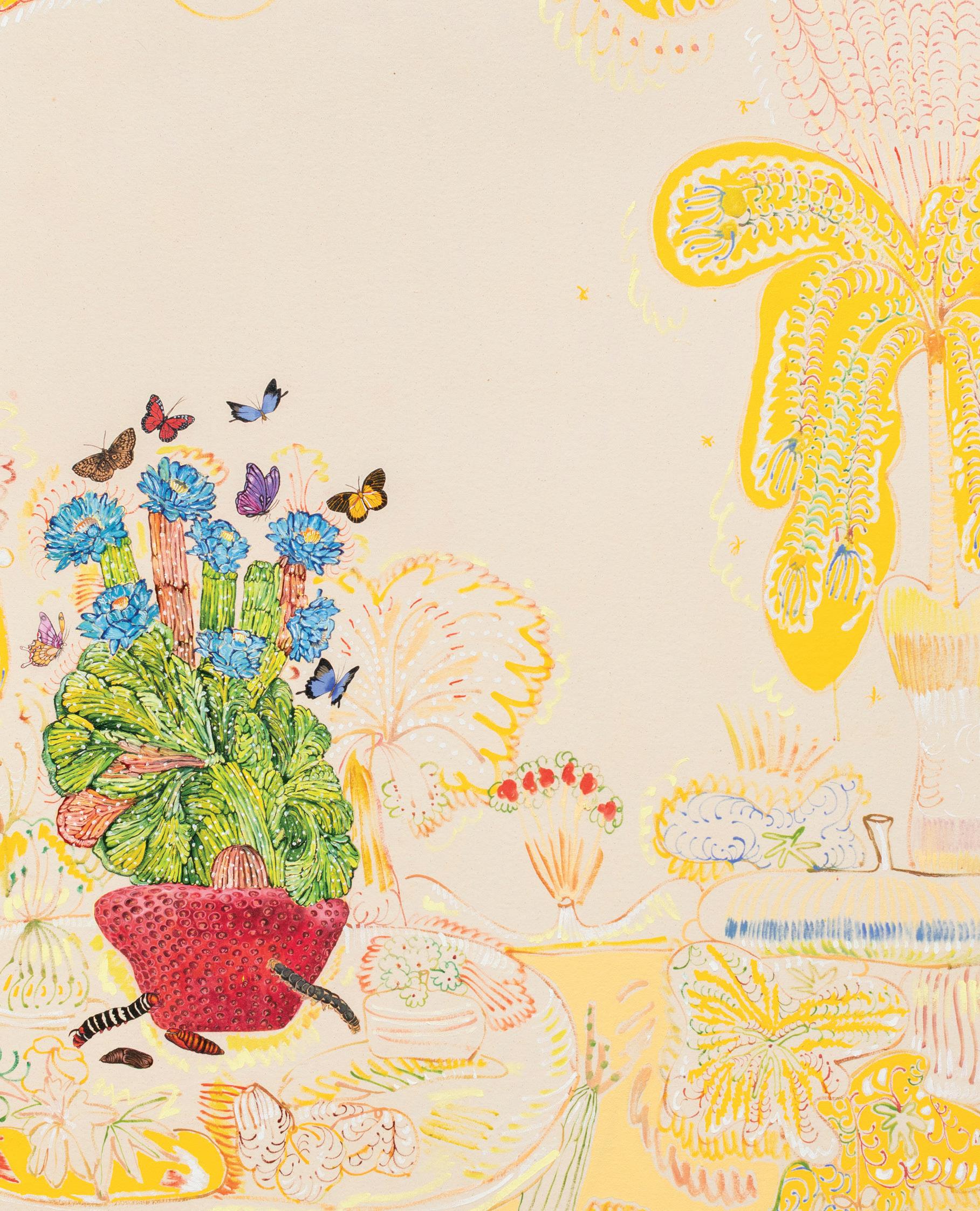

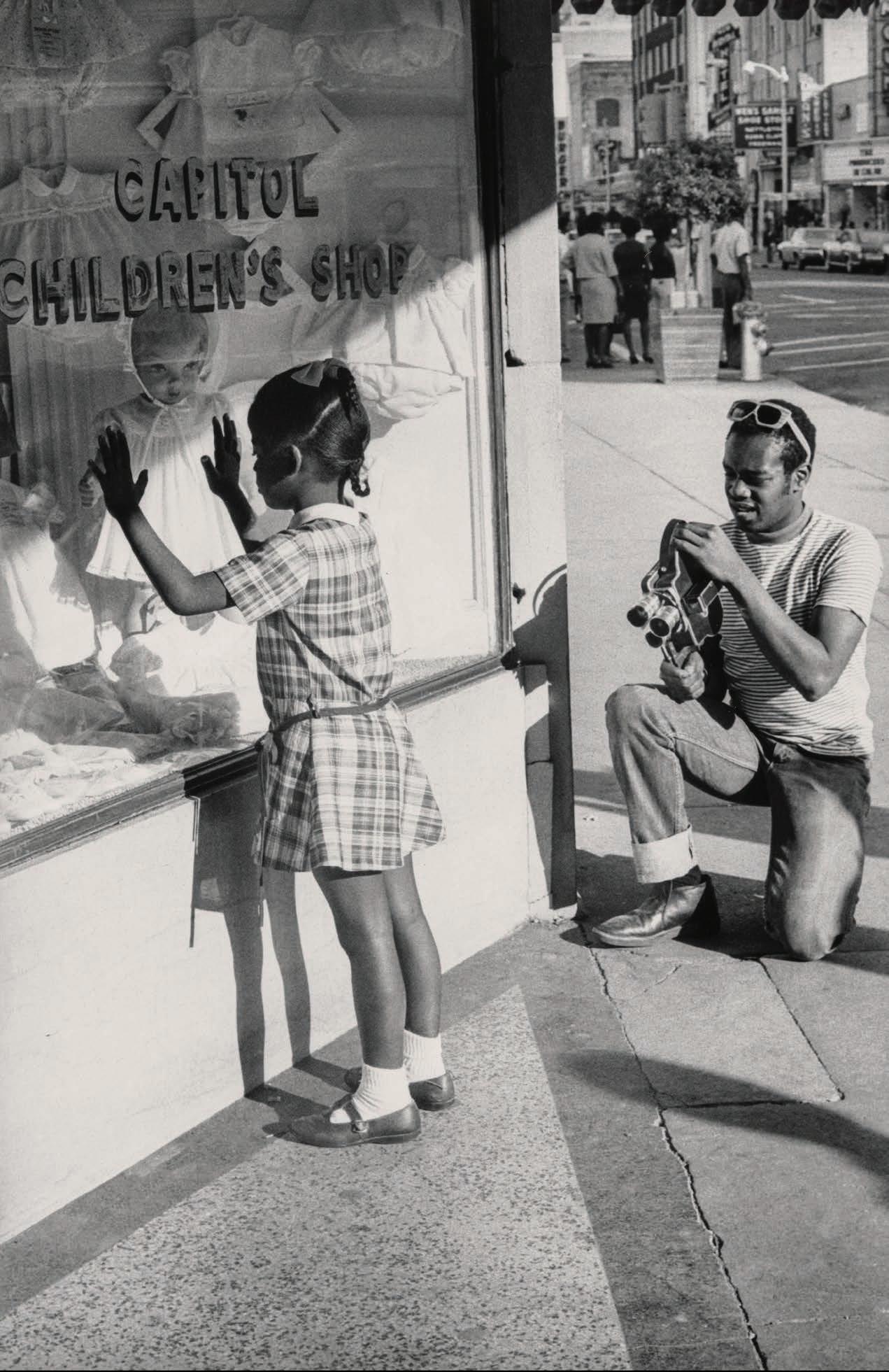

By Sophie Lee

Six filmmakers, whose latest projects dispatch from wildly different territories, share a work of art—from black-and-white photographs to explosive literary designs—that sparked a mood, moment, or motif onscreen.

You’re a down-on-your-luck comedian, it’s Christmas Eve, and you smack your head into a doorframe and need emergency dental surgery. This is where Jay Duplass’s latest film, The Baltimorons , begins, before descending into a hijinks-filled ride around town with the only dentist working. Between towing lots and wince-worthy holiday parties, Cliff (the injured) and Didi (the dentist) grapple with both addiction and midlife lethargy. Duplass followed the project with more comedian-focused fare—See You When I See You , which follows a comedy writer battling PTSD, premiered last month at Sundance. Seven features in, the indie veteran reveals one reference that never leads him astray: Greg Mottola’s 1996 family caper The Daytrippers

“I have so many influences, but everything kind of synthesized with The Daytrippers. It’s a family road movie. It’s tragically sad and very, very funny. It’s very homemade, charmingly so. The sweet spot for me is movies that are fun and funny, and that also break your heart. Those kinds of movies are rarely made, and The Daytrippers was just that. I laughed the whole way through; I don’t know what it is about laughing when you’re about to cry, but it makes you cry more. When I made The Puffy

Chair, my first feature film that actually was any good, people compared it to The Daytrippers. It’s a weird North Star to me, and a lot of people don’t even know it exists. I was graduating from college, not taking jobs, and starting to make movies in 1996; it was a really key moment for me. That movie was kind of my sign, like, You can do this, keep going.”

For her directorial debut, Constance Tsang went back to Queens, where she grew up. In Blue Sun Palace , three Chinese immigrants—two young women who work in a massage parlor and one of their older, hapless boyfriends—try to make it work Stateside for their own reasons. They circle each other and the city in quiet, extended scenes ushered onto the screen by Tsang’s minimalist touch. This study of collective grief pulled much of its pacing from the director’s

fascination with late filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s process, immortalized in his book Sculpting in Time

“It’s so rare these days to watch a film where the commerciality isn’t inherent in the filmmaking process. I ask myself, How can I push the form? Tarkovsky’s films are a marker of what the form can be. He has one chapter in Sculpting in Time that changed the way I looked at cinema—his perspective on time, rhythm, and editing. When you’re in film

school, you’re taught a very Western way of filmmaking. How are you putting together shots? How is the editing creating rhythm? I love when films exist in a space that feels all their own, but I didn’t quite understand what that meant for making a film. When I read this book, it just clicked. Filmmaking is really about the individual artist’s sense of time—it’s not necessarily about time as it exists on the editing floor. I took that with me to Blue Sun Palace, and hopefully to the rest of my films.”

Twin sisters covered in burn scars from a childhood accident are called to their mother’s deathbed. There, they learn it was their father who set the fire that disfigured them, and are instructed to seek revenge. This is the setup that underpins Is God Is , an award-winning 2016 play by Aleshea Harris, reimagined as her onscreen directorial debut this May.

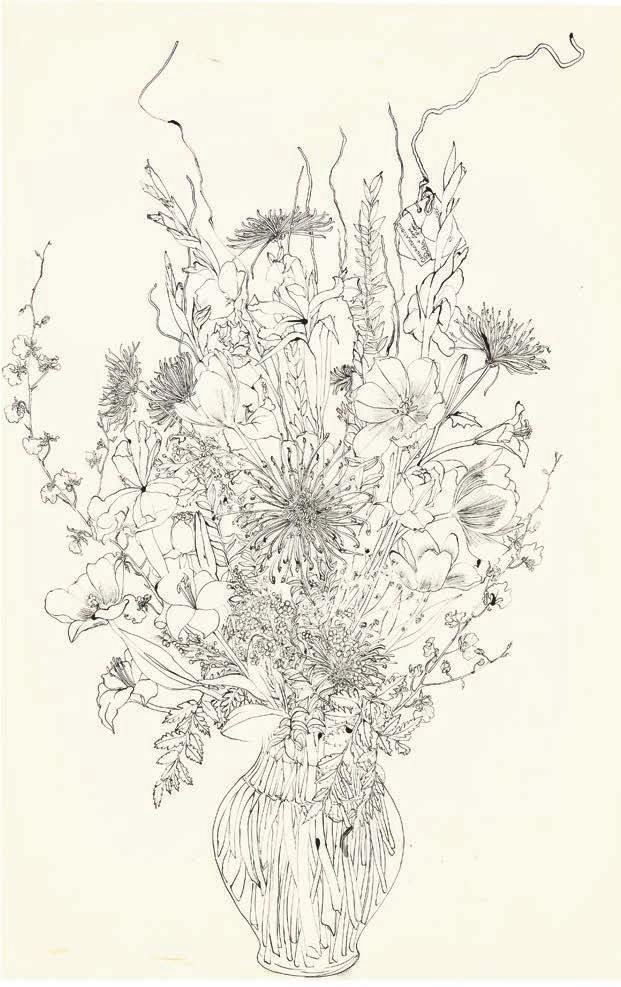

Harris’s original script is as stirring to read as its performance is to behold: When a character is shy, the type gets very small. When a character feels emotionally distant, their lines likewise move farther apart. Harris drew this penchant for avant-garde typography from a 1964 edition of Eugène Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano, featuring layouts by Robert Massin that unspool the playwright’s words in delightfully unorthodox ways.

“How can you place lines so that it’s less about communicating a word and more about communicating the goosebumps on the skin or the sense of being adrift that the character is feeling? How can you make the word feel as lonely as this character feels? I didn’t want to lose the poetry of the script, the rhythm of the language, and everything that was quirky and weird and dark about the play. Ionesco and Massin gave me permission to go bonkers crazy in support of the story I wanted to tell. In the movie, the twins communicate in a way that no one else can hear, which we experience as subtitles. That felt like an organic way to bring that performative language to the fore and let it continue to be a part of the fabric of Is God Is Absurdism is a response to trauma. A lot of the things the twins do—the way that they are—is a response to trauma, so it makes sense to me that that texture should be played out visually.”

We all handle grief in our own ways, but few do so more singularly than Helen Macdonald, a writer and naturalist who found respite after the death of their father by devoting themself to the care and training of a goshawk. Last month, English director Philippa Lowthorpe released H is for Hawk , an adaptation of Macdonald’s memoir starring Claire Foy, Brendan Gleeson, and a stable of winged performers in the role of Mabel the hawk. When she’s not soaring through the woods in some of the most elegant animal footage in cinema, Mabel is holed up at her handler’s home in a codependent relationship that seems to alternately serve and hinder both parties’ growth.

This intimate, softly lit setting pulled its inspiration from the first installment of a ’90s trilogy prized by cinephiles: Three Colors by Polish director Krzysztof Kieślowski.

“When I read Emma [Donaghue]’s first draft of the script, I found it so overwhelmingly moving. My dad had died not long before I received the phone call [asking me to pitch myself as its director]. It spoke to me in such a deep way—not just about grief but about a very good father-daughter relationship. What attracted [cinematographer] Charlotte Bruus Christensen and me to Three Colors: Blue was the intimacy of the camera with Juliette Binoche.

The compassion of the camera for the female character was really important to us. Weirdly, we both collected that reference separately in our research. Claire is such a fine actress. Everything is on her face in such subtle detail. In the beginning, when she answers the phone and learns her dad has died, she goes over to the fireplace and puts her head down, and she’s just in silhouette. You see a little tear. That’s one of my favorite shots in the whole film; it says so much about using light and shadow to chart an emotional journey.

In his sophomore feature, director and lead James Sweeney locks eyes with Dylan O’Brien across a circle of folding chairs. A moment is had. They’re part of a bereavement support group for twins who have lost their other half. Last year’s Twinless , for all its idiosyncrasies, dives into the irrepressible human desire for companionship and belonging; Sweeney and O’Brien’s characters grow by turns codependent and distant. While working on the film, the director gleaned insight into how twins move through the world from photographer Mary Ellen Mark’s book Twins , an immersion in the world’s largest annual gathering of doppelgangers.

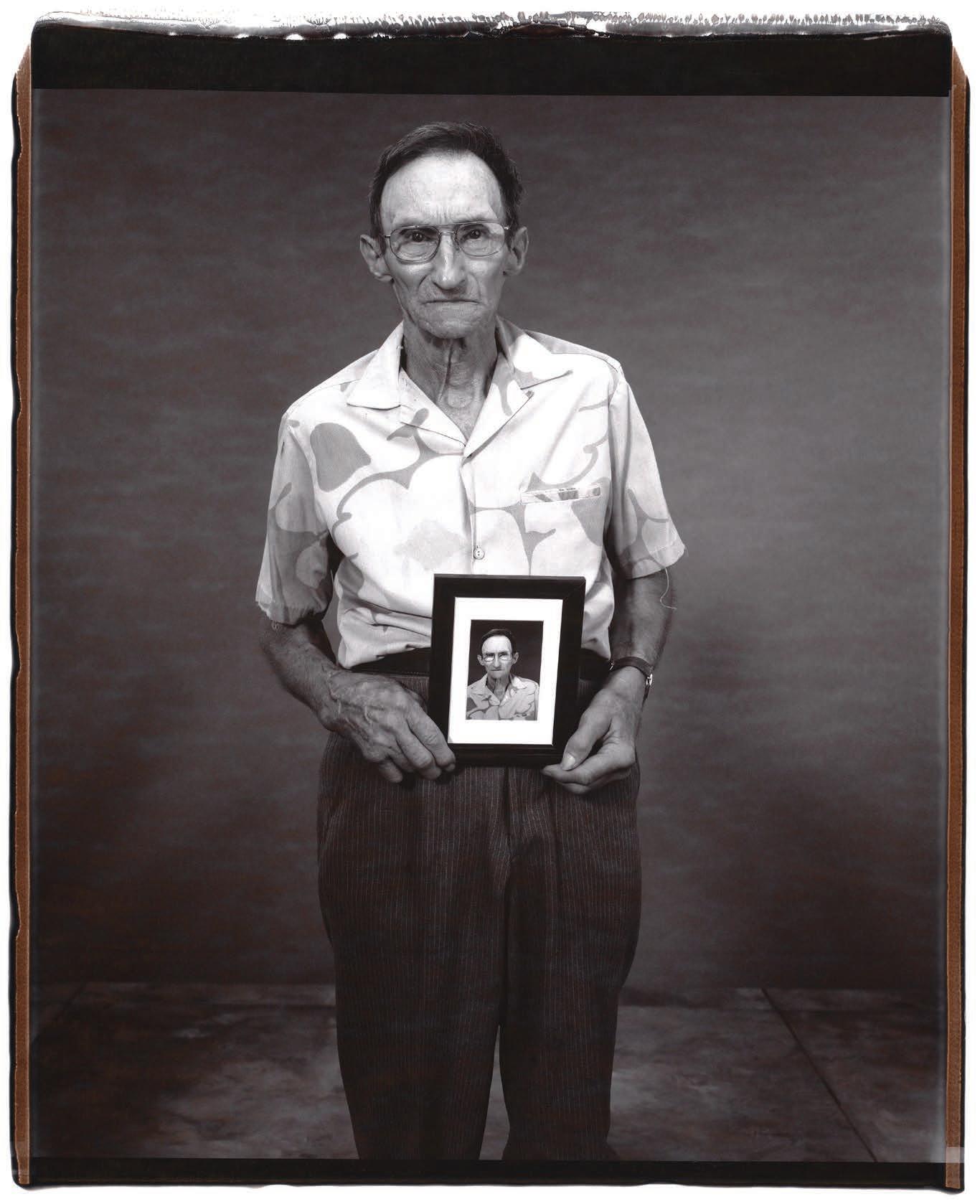

“Are you familiar with the cocktail party effect? It’s a psychological phenomenon where you’re in a really loud room, but if somebody all the way across the room says your name, you’ll be like, Oh, that’s me. My aunt Kathy and her husband have like 1,000 books in their New York apartment, and the word ‘twins’ leaped out at me from one of their spines. The book is full of photographs by Mary Ellen Mark as well as anecdotes from people attending the Twins Day Festival in Twinsburg, Ohio. This one really made me cry: John standing with a photo of his late brother. It says, ‘We slept in the same bed. It’s a good old-fashioned bed we have.’ In a test screening, we did get one reaction from someone who was incredulous that the film’s characters would sleep together. I had written that in the script already when I came across this. I was like, I’m vindicated, twins sleep together. I wrote a couple of other things down that I may or may not have stolen. [Another excerpt:] ‘We got so much attention when we were young, because if you’re a singleton, you don’t really stand out.’ I’m sure I’ve heard the word singleton in other places, but to hear them use it was so special. They’re all wearing matching outfits [in the photos]; I don’t know if that’s what everyone does at the Twins Day festival. We tried to do an event there, but they weren’t interested.”

March 5–August 2

SIX DIRECTORS, ONE INFLUENCE

A gangly man named Colin is singing in a barbershop quartet at a bar. When he steps to the counter, a smoldering biker sidles up alongside him to arrange a hardcore BDSM meetup. The pair are played to pitch perfection by Harry Melling (songbird) and Alexander Skarsgård (motorcyclist) in Pillion , a “dom-com” directed and adapted by debut filmmaker Harry Lighton from Adam Mars-Jones’s 2020 novel Box Hill , released Stateside earlier this month. Their first encounter—which sees Skarsgård arrive in full biker regalia with a Rottweiler in tow, and Melling scurry over in his dad’s leather jacket toting the family dachshund—is followed by a quick tumble into a startlingly poignant relationship rife with sex parties, boundary-testing, and assless

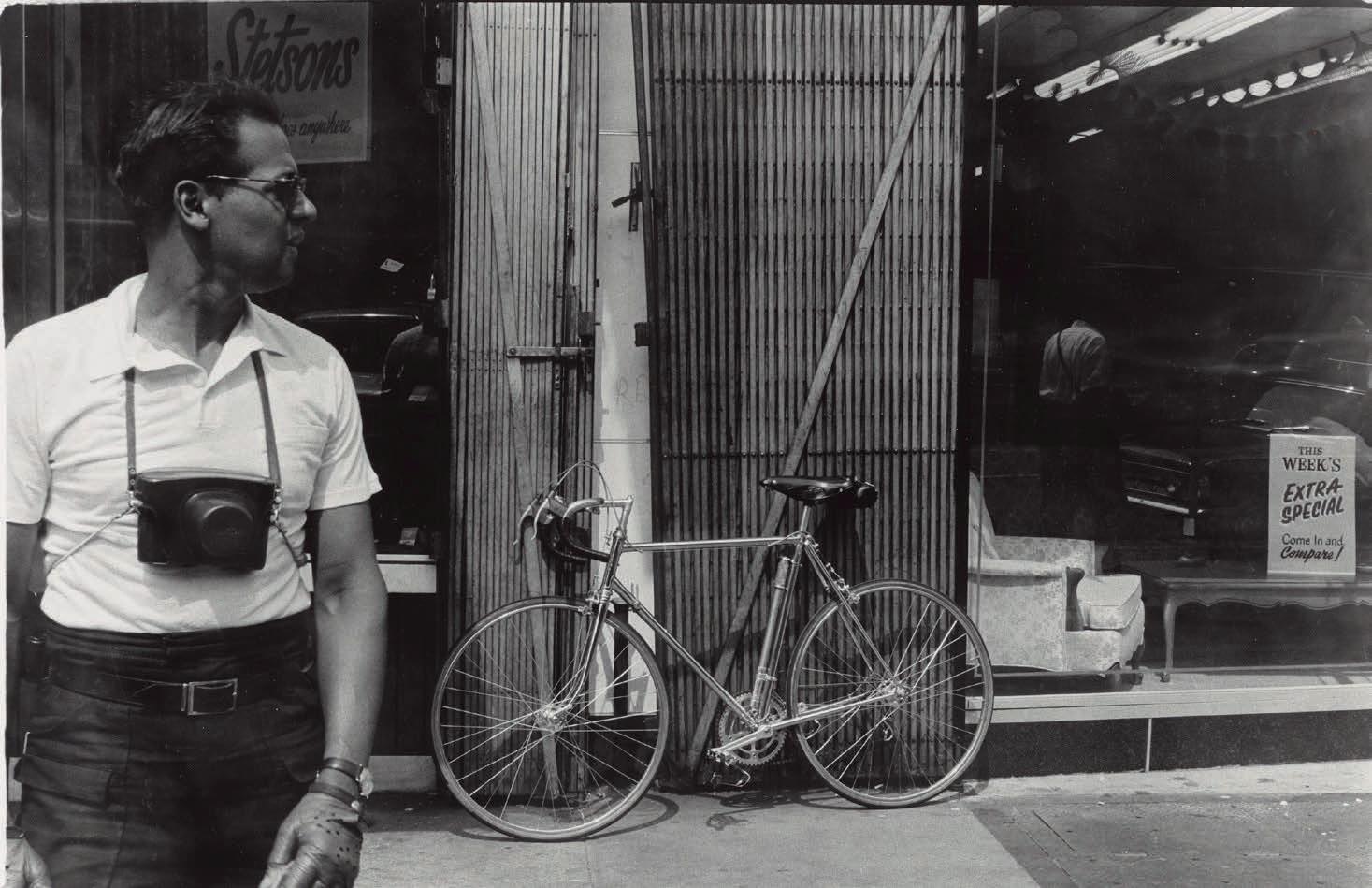

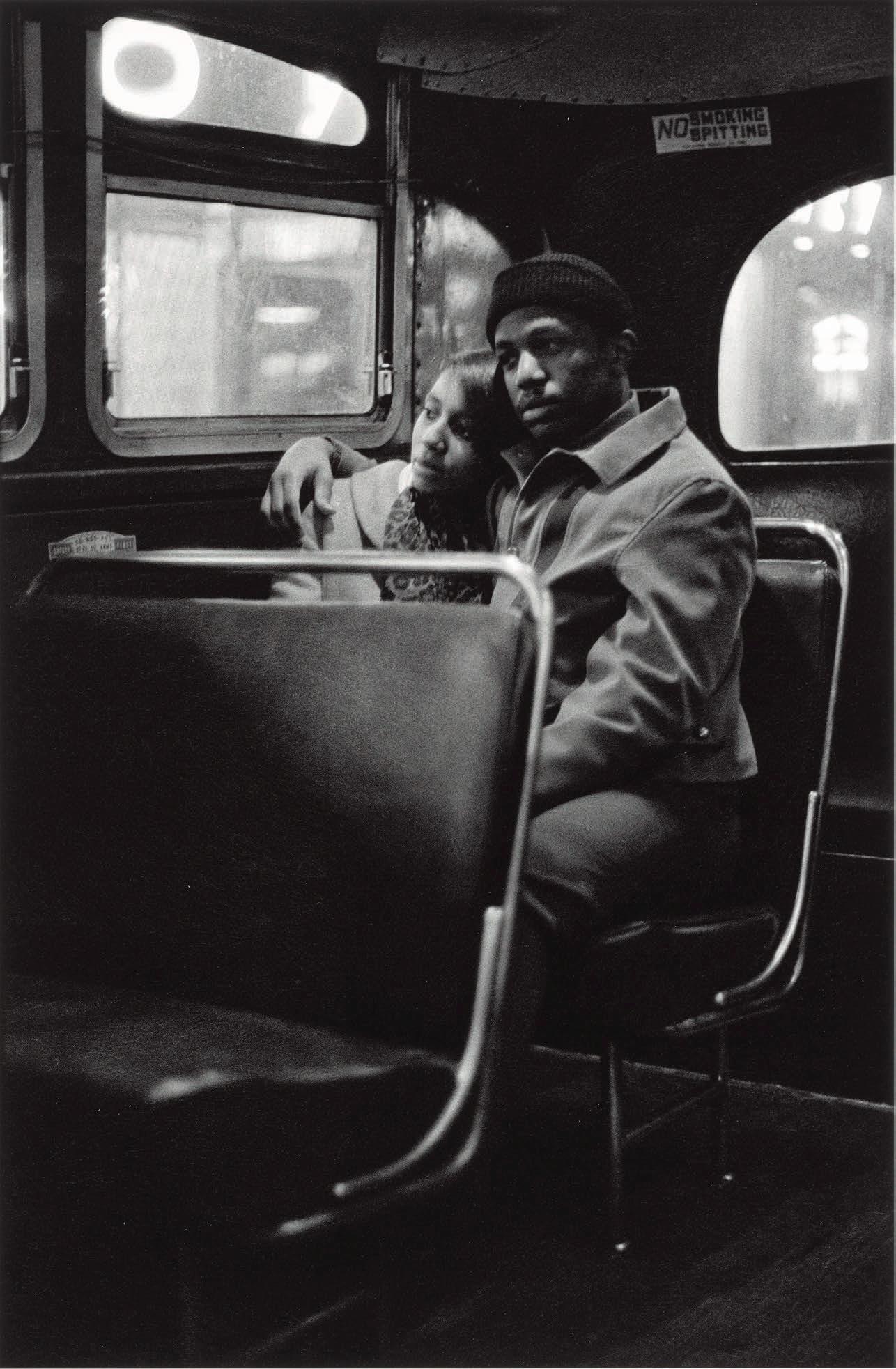

wrestling singlets. Lighton pulled its first laugh-out-loud moment, however, straight from a black-and-white still by the late Franco-American photographer Elliott Erwitt.

“I saw (dog legs) as the image in an obituary. I was well into the writing of Pillion at that stage, and it spoke to me. The motorbike is such a loud symbol that I was wary of having lots of other symbols that spoke to the stark division in power and physical stature between Ray and Colin, but then I saw that photo, and it made me smile. I wanted the audience to smile as much as they might be gasping or clutching their pearls. After seeing it, I added Rosie the Rottweiler and Hippo the dachshund into the film. The photo is of a chihuahua, but my

family had a sausage dog called Hippo, so it’s a testament to him. The Great Dane’s and the human’s eye levels are above the frame, and then the chihuahua’s is at the level of the camera; that really speaks to Colin’s perspective in the film, which is the camera’s perspective. He’s often, metaphorically, looking up at Ray. [But] the reason I admire Colin so much is that he resists the perception of himself as weak and passive. He has a fairly extreme first encounter with Ray, yet at the end of it, he’s grinning and skipping along, like, ‘When can we do this again?’ This is someone who’s not totally sure what they want, but they know it’s something more than what they have.”

Bruce Richards: Silent Sirens

52 Walker Street

February 20 - March 21, 2026

VISIT LIBRARY180 A NEW REFERENCE LIBRARY. BY APPOINTMENT. 180 MAIDEN LANE NEW YORK

Nicholas Aburn’s unorthodox policy promises an interesting tenure for the designer at the helm of Area.

By Megan Hullander

Eduardo Cerruti and Stephanie Draime

Nicholas Aburn’s optimism has teeth. It’s a New York affect: practical, direct, and somehow still romantic. In the studio, it functions like policy. “I try to say yes to every idea,” he says, and he asks the people around him to start there, too. Then comes the real vetting: cost, time, whether it fits the business’s priorities. Yes, for Aburn, keeps “the creative tap flowing.” The point is the momentum. Nightlife staple Area tapped the designer as creative director in early 2025 after the downtown brand’s cofounder, Piotrek Panszczyk, stepped away following just over a decade at the helm. Area’s visual language is legible from across a room: glamour that flirts with overload. Aburn arrived fluent in that dialect, with a resume that reads like a checklist of the 21st century’s hard-edged darlings, from Tom Ford to Alexander Wang to Balenciaga’s couture studio under Demna. He speaks to me from his Paris apartment, which is a study in controlled romance: deep red velvet, white molding, parquet floors that catch the daylight, a high-

gloss table the color of dried red wine. Aburn grew up in rural Maryland, far from fashion’s easy access points. He made his own curriculum from the glossy magazine stacks at Barnes & Noble and weekly glimpses behind the curtain on Elsa Klensch’s Style. Those early images left him craving glamour on the street. So, decades later, his pitch to Area was simple: Keep the spectacle, add the day-to-day. A clearer quotidian dimension with no apology for shine.

Aburn’s Spring/Summer 2026 debut at New York Fashion Week last September made that case, adding nods to the pulse of daily life without sanding down Area’s edges. His most persuasive looks refused to choose sides: a satin hoodie paired with a long skirt—tuxedostyle and held together by an undone cummerbund.

Aburn’s vision for his Area debut is evinced by the show notes, written in the form of a screenplay. The single sheet of text chronicled the ritual of getting dressed for a night out, ending on a line that swings

“Fashion tells a story, but it’s only the story of a single day. One day, I want to feel strong. The next, I want to feel like summer.”

between thrill and dread: “What if the confetti never stops falling?” It gave the clothes a sense of psychology. “I wanted to get people feeling and not thinking,” Aburn says. He’s less interested in the performance than the private experience before it, when a person decides who they’re playing. “Fashion tells a story, but it’s only the story of a single day. One day, I want to feel strong. The next, I want to feel like summer.”

If the collection has a hero garment, it’s the cloud confetti mini dress. Confetti’s arc is short—from joy to debris once the music cuts out. Aburn turns that vanishing point into a site of intricate labor; the dress reportedly took several weeks to construct. “I like taking really simple things and treating them with a reverence,” he says. The gesture feels almost devotional.

Aburn’s gift is the edit. He designs for people in motion, for moods that shift, for confidence that needs a little structure. He doesn’t ask you to buy into the fantasy; he builds it until it’s within reach.

After an almost 20 -year hiatus from fiction, Wayne Koestenbaum—who has chronicled his fixations on everything from humiliation to Harpo Marx—makes his return to the form by examining an anonymous protagonist’s infatuation with a rabbi.

BY ADAM ELI

“Hey, want to be in my movie?!” a man with curly hair, thick glasses, and a fluorescent coat yelled, half chasing me down West 26th Street as I exited Visual AIDS’s annual “Postcards from the Edge” show in 2023 . I’d heard many stories that began with that very question and ended poorly, so I said maybe and took his card. That’s how I learned that the man was Wayne Koestenbaum, a leading figure in New York’s queer and literary scenes since the ’80 s, synonymous with confessional prose, deliciously dissonant poetry, and genre-straddling criticism. His best-known book remains 1993’s The Queen’s Throat, which chronicles the timelessly homosexual obsession with opera.

This March, Koestenbaum re-enters the fictional fray with his first novel in almost two decades. And what a novel it is. My

Lover, the Rabbi centers on an unnamed narrator’s psychosexual affair with an aging rabbi. Its 464 pages, like their author’s visual art practice, pull no punches in their depiction of sexual obsession. I knew I had to talk to Koestenbaum before the rest of the world dives in, so I called him up to talk intellectual filth, bad gays, and writing to embarrass. (Oh, and we made the movie, by the way.)

A key element of the book is the conflation of desire and repulsion. It feels like the protagonist hates the Rabbi, yet he’s so sexually infatuated with him.

My earliest gleams of homosexual feeling were necessarily twinned with disgust. It was the 1960 s and 1970 s, and there was no language or idealization for what I was feeling. Gayness was a kind of filth location. That’s not unique to me, [but] many people don’t build an erotic home

around the filth portion of eroticism. I did—and maybe that’s because I’m such a deeply internal person. The deeper you go into your own consciousness, the filthier it gets.

Does it feel accurate to say that the narrator could be seen as a self-hating Jew in addition to experiencing internalized homophobia?

Inevitably, yes. But my hope with this book is to experience those vibes rather than take them as received wisdom. We all know about the self-hating Jew and internalized homophobia, but the actual experience of those things may be rich with desire and erotic potentiality. Built into the narrator’s love for the Rabbi is the knowledge that the Rabbi always has and always will refuse him. His overwhelming desire for the Rabbi will never be met: It’s an asymptote.

The book isn’t exactly an “easy read.” How do you think about legibility and opacity when you write?

In terms of fiction, my role models are Samuel R. Delany, Jean Genet, Hervé Guibert, Pierre Guyotat, and Dennis Cooper. I learned from them that you need to pay attention to the things that give you the creeps and that really turn you on—maybe even at the exact same moment. I’m constantly telling my students that if you don’t wake up in the middle of the night terrified and embarrassed about what you’ve written, then you’re probably not doing the right thing.

This book has so much sex—with people who aren’t 21 and don’t have washboard abs. There’s this quote I’m obsessed with about “a body allowing itself to not go to seed but relax in its own unfenced fruitfulness of contour.”

It’s about the gay male body that isn’t necessarily poorly taken care of, but isn’t at the gym every day either.

I’ve never been a good gay in terms of the way I look. I’ve never felt that I perfectly occupy a desired position, like “nerd twink.” I’ve always felt very ill at ease in places like Fire Island, at least when I went in the ’80 s. And as a writer, of course, I’m going to write about the experience of not belonging to gayness. You don’t ask that a rabbi or a poet look like an Abercrombie & Fitch model.

Do you care about how the audience receives the book?

My life as a writer has mostly been avoiding the reality that somebody might one day read my book. This novel in particular happened in the deepest privacy. When I started writing it, I was

sitting on a pink couch in my house in Germantown. It was a Friday night, and the first line of the book came to me. I am aware that it will fall somewhere, but I guess I don’t want to prognosticate lest anything I fear comes true.

Why a novel after 20 years away from the form?

I’ve always idealized the novel, without it necessarily being my first choice as a reader. A novel, at its best, is a Gesamtkunstwerk that captures the flow of time and an entire body of real experience. When I’m writing my other books, I always pretend that they’re novels; I never want my non-fiction to be pedestrian. When I write anything, I have in mind this torrid tunnel of language. When I wrote the first sentence of My Lover, the Rabbi, I thought, I want to continue this impulse until the end of time.

IT’S WHERE MUSEUMS SHOP AND COLLECTORS GET THEIR KICKS. TEFAF MAASTRICHT IS WELL WORTH THE TRIP.

BY KARLY QUADROS

Once a year, Maastricht, with its medieval basilicas rising above the banks of the Meuse, becomes a magnet for art collectors, museum curators, and antiquarians. The small Dutch city was put on the map back in 1992 as the official birthplace of the EU, so it’s no wonder that it’s also become the place where visual arts, antiques, jewelry, and design collide at The European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF).

This year’s edition, which will be held at the Maastricht Exhibition & Conference Centre from March 14 –19 , spans everything from Dutch Old Master paintings to contemporary textiles. The fair (which also boasts a New York counterpart) has become especially popular with museums and patrons looking to

expand their holdings. Last year, the Met acquired a post–French Revolution table stand by Joseph Chinard, while the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston secured a still life by Post-Impressionist Émile Bernard. The Art Institute of Chicago expanded its trove of works on paper with a self-portrait by Léon Spilliaert.

“These acquisitions are not only a testament to the breadth and expertise of our exhibiting galleries but also ensure that works of art enter public collections where they can be studied, preserved, and shared with audiences for generations to come,” notes TEFAF’s Head of Collectors and Museums, Paul van den Biesen.

TEFAF’s Focus section is playful and varied, putting the work of canonical figures in conversation with contemporary and emerging artists. Looking for

Scandinavian and De Stijl design? Galerie Van den Bruinhorst will present work by designer and architect Gerrit Rietveld. Perhaps midcentury French avant-garde is more your style? Ceysson & Bénétière will offer work by Patrick Saytour, a founding member of the Supports/Surfaces movement. If ceramics are on your shortlist, Tafeta will bring works by Ladi Kwali, a Nigerian maker who found renewed attention after last year’s Ford Foundation presentation.

With works ranging from the Renaissance to 21st-century Mexican design, TEFAF Maastricht draws an expansive crowd. Just be sure to snap up anything you’re eyeing before a museum does.

February 21 March 28, 2026

Last November, Daniel Kolitz published a viral article that charted the rise of gooning, a radical new form of masturbation. Our in-house psychoanalyst quizzes him on its aftershocks— and his takeaways.

BY JAMIESON WEBSTER

Freud called masturbation the “primal addiction” upon which all others are based, but refused to link it to pathology or illness. And yet—despite 50 years of sex-positive culture—when considering the consequences for a generation raised on infinite, frictionless pornography, we’re abruptly returned to the age-old fear that masturbation will ruin us.

Our culture wars circle hedonism and asceticism as they did at the turn of Freud’s century, with many trying to square the circle along political lines that blur as easily as the clientele lists of Jeffrey Epstein. Psychoanalysis, however, is neither hedonistic nor ascetic; it sees both as strategies to manage an intractable problem everyone fears and feels overwhelmed by. Namely, sexuality. If some patients reinforce problematic fantasies or pathological compromises through compulsive masturbation, who’s to say masturbation is the culprit rather than a symptom?

No recent article on contemporary sexuality has generated more cultural friction than Daniel Kolitz’s “The Goon Squad,” published in Harper’s last November. Suddenly, everyone knows what edging means, what a goon cave looks like, and what a pornographic music video might contain. Kolitz searches this world for a shred of redemption. He wonders if gooners are pursuing a limit through terrifying excess—dreams of self-ruination, mental annihilation, ecstatic dissolution, desires for authority and community, the wish to crawl back into the warm infinity of screens. In fact, all this sounds a lot like what every one of us

is struggling with. (Minus, perhaps, the industrial quantities of masturbation.) But Freud would say that masturbation merely discloses what’s already there, so I called up Kolitz to try to get to the bottom of what this brave new world can tell us about who we are—and where we are headed.

What is chronic porn masturbation a symptom of?

There are several factors at play. One is the sheer accessibility of it. As far as people looking at it to a self-punishing degree, in a way that interferes with their relationships, certain obvious social factors are at play. The pandemic sent people indoors. People are lonelier than they’ve ever been. People are less embedded in a community than they’ve ever been. And a lot of the people I spoke to had jobs that were punishing.

We’re all a bit messed up about what’s real these days. That’s why I liked the gooners as you depicted them—searching for reality more than escaping it, perhaps.

A lot of the porn they’re watching is actively telling them that they’re losers, that they have terrible lives. A lot of them told me they were unhappy and that this insulting entertainment was a way to eroticize and dig into the reality of the situation—to make it fun, in a way. The idea is that you can push through reality—or turn to fantasy—to engage with your life in a way that’s more appealing—or in this case, sexualized. What got me interested in the first place was the pornification of social media, everything being funneled into OnlyFans.

In psychoanalysis, some part of sexuality is always repressed. The more you try to make it a seamless part of your conscious life, the more you’re actually ignoring those repressed aspects. Pornography might even reinforce repression for some. This seems to make sense with the fact that pornography has led to a disengagement with sex IRL.

I spoke to someone who calls himself Alpha Gooner more than anyone else in the piece. He was a pornosexual; I found him to be a fascinating character. We went through the whole course of his sex life. He’d had a little bit of sex in high school and then stopped in his early 30s. He was against porn as self-degradation; he viewed it as a hygienic regimen and a form of selfcare—he would exercise, then watch porn to release his sexual desire. These were all distinct parts of his life that worked to keep him disengaged from sexuality.

We should bring back more classic fantasies, bring back the body, bring back limits to transgress.

I don’t know if we’re too far gone for that. I’m kind of a doomer—I don’t think anything about our relationship with technology is going to change anytime soon. The only hope I see is boredom: people reaching a point of disgust with the sheer amount of content they consume and deciding on their own to change, to leave their bedrooms. I think this has to come from us; it’s not going to come from corporations or the government, nor perhaps should it. At a certain point, it just has to be so numbing that some people will close their laptops, turn off their phones, and say, “I’m done with this.”

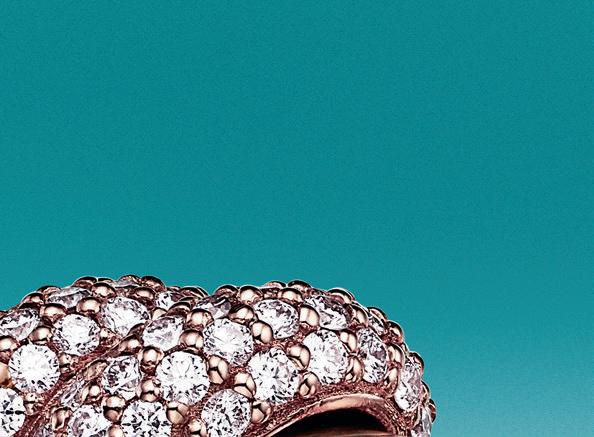

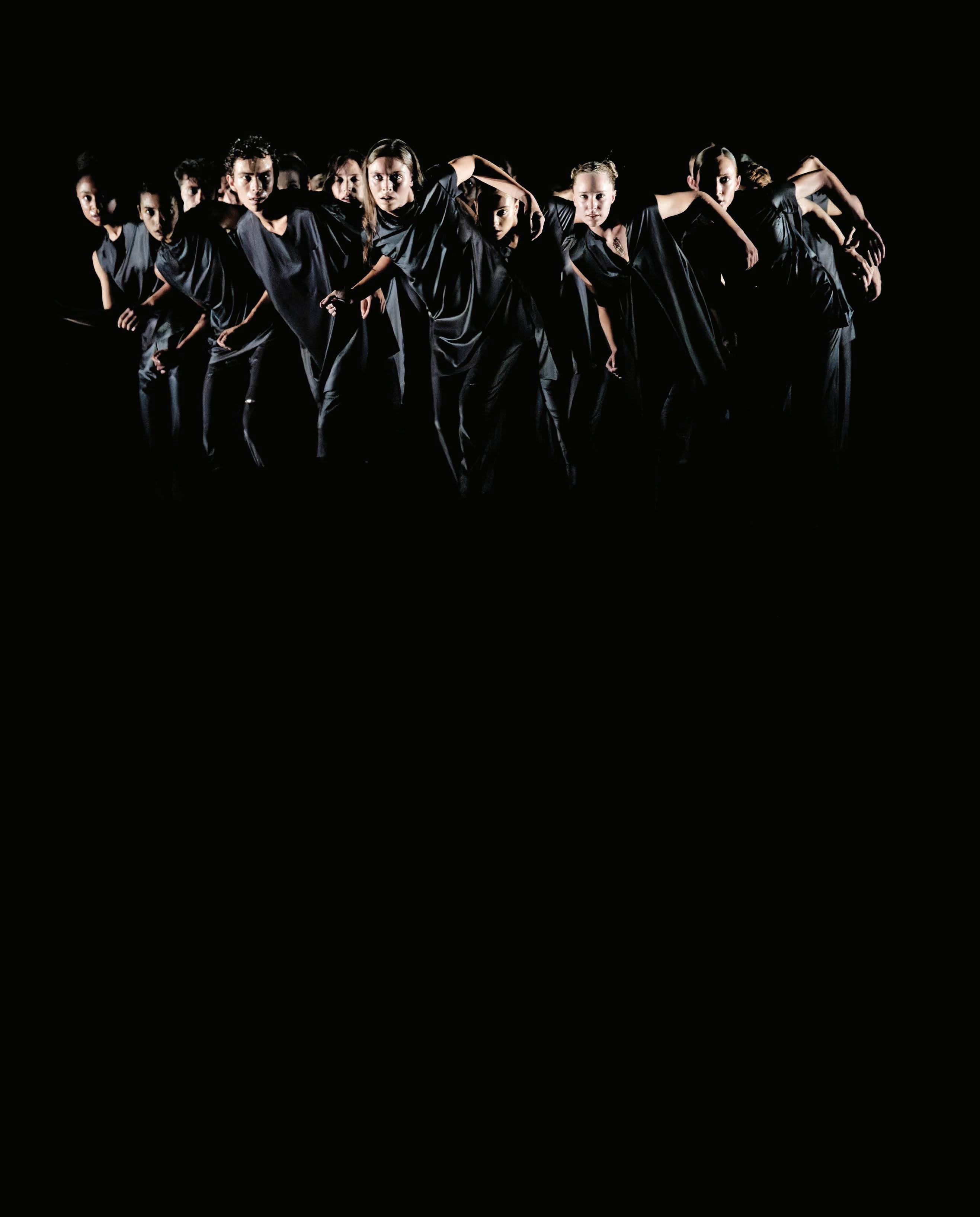

This spring, Van Cleef & Arpels transforms New York into the backdrop of a dance-world reunion for the ages. Expect canonical restagings and the finest choreography of our day.

The friendship of Claude Arpels and George Balanchine has gone down in history as one of the more fortuitous encounters between the worlds of fine jewelry and dance. The heir to the Van Cleef & Arpels empire and the choreographer met in 1961. Arpels had grown up frequenting the Paris Opera with his uncle Louis, a champion of ballet who helped make the ballerina clip a Van Cleef & Arpels signature; the Russian-born Balanchine was by then a renowned figure stateside, having established New York City Ballet in 1948 and given the postwar public a treasure trove of now-seminal works. Six years after meeting Arpels, Balanchine would cement their bond—and his reverence for his friend’s artistry—with Jewels, a plotless ballet divided into three acts: Emeralds, Rubies, and Diamonds.

Reflections: A Triptych, commissioned by the jewelry house from leading choreographer Benjamin Millepied and similarly inspired by precious stones, follows in these storied footsteps. The trio of works, set to scores by Philip Glass and David Lang and punctuated by visuals

from artists Liam Gillick and Barbara Kruger, is at the center of Van Cleef & Arpels’s second New York edition of Dance Reflections. (Reflections will be performed in its entirety in New York for the first time on the occasion.)

Running from Feb. 19 to March 21, the festival brings 15 other dances—both canonical and ultra-contemporary—to the city, as well as over 20 workshops for professionals and enthusiasts alike.

The festivities kick off with a one-two punch that bridges three decades of creation. On opening night, the Lyon Opera Ballet will perform Merce Cunningham’s 1999 Biped, which he once compared to “switching channels on the TV,” and rising Greek auteur Christos Papadopoulos’s 2023 Mycelium at New York City Center.

More Merce follows a week later, when the Trisha Brown Dance Company and Merce Cunningham Trust stage the late legend’s 1977 Travelogue alongside Brown’s 1983 Set and Reset Both dances pay homage to Robert Rauschenberg, whose centenary is being honored this year; watch out for the artist’s distinctive silkscreened

costumes in Set and Reset and his sculptural composition of wooden chairs, white platforms, and bike wheels in Travelogue. The global 21st century is also well represented at Dance Reflections.

Soa Ratsifandrihana mingles popping, the Madison, and dances from her native Madagascar at New York Live Arts, where the Franco-Algerian choreographer Nacera Belaza also stages her hypnotic La Nuée, inspired by attending a powwow outside of Minneapolis. Belgian mainstay Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker rallies 13 performers at NYU Skirball in an ode to walking, while Alessandro Sciarroni excavates the polka chinata, a 20th-century Italian courtship ritual that literally brings men to their knees. The offerings are sweeping, yet the program somehow maintains the intimate feeling of a young Arpels visiting the ballet or slinking around to the stage door to meet a rising choreographer.

By Matthew Gasda

The 2010s gave us Breaking Bad and Mad Men. The 2020s are giving slop. With television in decline, talent is migrating from the screen to the stage.

It was around 2010 that Boomer culture, dwarfed by the progressive optimism of the early Obama era, gave way to millennial culture. TV—not to mention music, food, movies, fashion, and politics—entered the era of intentionality. Americans wanted guilty pleasures in forms they didn’t have to feel bad about: Sweetgreen instead of McDonald’s, yoga instead of vegging out, Obama instead of Bush, Bon Iver instead of Creed.

Prestige TV—a 21st-century vestige of 20th-century American monoculture reflecting the millennial emphasis on ideological coherence, narrative heft, and novelistic dimension—was one of the organizing principles of the 2010s. Among the spoils of this ebullient period was a wave of great series: Game of Thrones, Girls, Boardwalk Empire, Breaking Bad, Mad Men, The Walking Dead, House of Cards, Orange Is the New Black, Downton Abbey, Homeland, True Detective. These dramas reflected a collective faith in TV as a culture-unifying apparatus and a pressure-release valve for our anxieties—about politics (House of Cards, Game of Thrones), terrorism and American dominance (Homeland ), modern romance (Girls), abject consumerism (Mad Men), the opioid epidemic (The Walking Dead, Breaking Bad ), and technological and spiritual dread (Westworld, True Detective). The richness of these worlds, and the writing and acting that ushered them to life, seemed to say, “America may be declining, but American culture is thriving.”

Now, just 15 years later, American

television has come to embody that decline more than its salvation. Some of the most-watched new series of 2024 were reboots, spinoffs, and IP extensions (Squid Game, Matlock), and the last genuinely era-defining drama, Succession, ended its run in 2023 without a clear heir apparent (the cultural impact of Severance and The White Lotus was muted by comparison). There are many reasons for the downfall of prestige TV. For one thing, a growing percentage of American viewers now watch partly on their phones (over six percent watch exclusively on their phones), and an even greater percentage are scrolling on an additional device while they do it. The visual and linguistic density of the programming we watch is shrinking to meet us where we are.

But perhaps the most damning reason—and I know this from experience, having pitched and sold shows

to studios over the last four years—is that the industry’s algorithm-choked, decision-by-committee approval structure promotes copycats and risk aversion, a pattern that’s hardened during the streaming wars. I’ve had several pitch meetings with creative executives where I’ve been told that the data doesn’t support the kind of show I’m envisioning. (In one, I was told that audiences these days were interested in lighter material; in another, I learned that they only wanted darker fare. In every meeting, I was informed that nobody wants shows set in Los Angeles or New York.) I got the sense that these executives sit down with me out of nostalgia for a time when they could just hire playwrights away from the stage because they had a gift for dialogue. Of course, the quality of the writing matters enough to get you into the room, but today, the industry is looking for writers who are ready to follow trends rather than spark them.

But all that prestige has to go somewhere. I would argue that, since the pandemic, it has migrated steadily onto the stage. Look at who wants in: Hugh Jackman started his own small theater company; A24 bought Cherry Lane; Robert Downey Jr. chose McNeal for his Broadway debut in 2024 (a play, ironically, about A.I.); Sarah Paulson and Jessica Lange earned Tony nods in thorny family dramas; Steve Carell attempted Uncle Vanya; Rachel

Writing for the theater is no longer a waystation on the path to a lucrative career in screenwriting but an end in itself—a meaningful outlet for writers, especially younger ones who recognize the inaccessibility of today’s film and TV industry.

McAdams starred in Mary Jane; Jeremy Strong took on Ibsen in An Enemy of the People; Kit Connor and Rachel Zegler appeared in a Zoomer Romeo and Juliet; and, in 2025, Keanu Reeves took a turn in Waiting for Godot. A list of heavyweights at their commercial peaks, who could land any multi-million-dollar deal under the sun, deliberately choosing eight shows a week.

Of course, the theater has always been a prestigious institution. It’s the crucible of the acting profession. But until recently, its renown had been largely emeritus—the entertainment-world equivalent of studying Latin. What is changing now is that writing for the theater is no longer a waystation on the path to a lucrative career in screenwriting but an end in itself—a meaningful outlet for writers, especially younger ones who recognize the inaccessibility of today’s film and TV industry.

“There’s a term you hear often now,” Mark Ruffalo, who attended a performance of my play Dimes Square in Greenpoint last winter, told me recently. “[TV audiences] want something ‘sticky.’ Stories that feel familiar are very easy to get stuck on. I’ve noticed [that studios are] steering away from things that are ‘issue’-based, overtly political, too

“I’ve noticed that studios are steering away from things that are ‘issue’-based, overtly political, too ‘challenging.’ Everyone is playing it safe.”

– MARK RUFFALO

‘challenging’ … Everyone is playing it safe.” The Emmy-winning and Tonynominated actor, who starred in HBO’s small-town thriller miniseries Task last fall, got his first big break in the 1996 Kenneth Lonergan play This Is Our Youth, and has kept a toe in the theater ever since. Ruffalo added that the success of unwieldy original scripts like Anora and The Brutalist is a sign that audiences—if not their studio gatekeepers—still thrill to the riskiness that prestige TV once offered.

Because of production costs and the sheer byzantine nature of the TV industry, there’s no real prospect of disruption from within. Television has no indie world, no festival circuit in which to nurture an Anora. Instead, it’s locked in a deadly battle with the most impactful cultural products of the decade: TikTok, YouTube, X, Reels, OnlyFans. There’s more talent bubbling on the Internet than in most writers’ rooms, and much of the talent that remains is shackled to preexisting intellectual property.

When I opened the Brooklyn Center for Theatre Research in Greenpoint in 2023, after years of doing theater in borrowed lofts and townhouses, I wanted to prove that a full-time DIY theater could sustain itself. And— though not without endless time and effort—it has. Theater’s rise to prominence can be traced to a few factors. For one thing, small-scale, intimate theater is cheap and repeatable and fun, assuming the material is grounded in text and not special effects, and actors are willing to perform with minimal rehearsal time. My most visible, most produced play, Doomers, had an original total overhead of around $10,000 for its New York production. I workshopped it over the course of six months, hosting weekly gatherings with the actors to listen to new drafts in front of live audiences, which subsidized the costs. Eventually, I was able to franchise the chamber theater model and bring

Doomers to San Francisco and London, where it also had sold-out runs. If I had written Doomers as a film, I would’ve been lucky to land even a few meetings; ironically, it has a far greater chance (indeed, there’s interest and investment) of becoming a film now that it’s seen multi-city success as a play.

Theater also has a cool factor. Despite their minuscule market share, the artistic allure of playwrights has remained relatively untainted compared to that of many other cultural practitioners; the term playwright still connotes auteur. And while the relatively clued-in urbanite is unlikely to know who penned Succession, many can name-drop the likes of Annie Baker, Jeremy O. Harris, or Suzan-Lori Parks.

There’s also the tech-resistant nature of the form. I have produced enough sub-100-seat plays, from San Francisco to Stockholm, to know that people are willing to pay real money for an encounter with language that’s existential, not sterilized. Because a play isn’t algorithmically constructed to trigger a dopamine response, there’s room for a broader range of reactions: unwieldy silences, odd turns of phrase, moments of reflection. You can’t open 12 tabs while watching it. “Any sort of challenging art feels somewhat religious … And a theater is a church-like setting,” says Sam Nivola. “You can’t just eat a bowl of pasta and go to bed. You’re forced to communicate, to share your reactions to the art you just saw with your peers.”

For Nivola—the 22-year-old actor who played the gangly emotional anchor of The White Lotus’s third season, who I also met after he attended a show at BCTR—and so many others his age group who grew digitally native amid a pandemic, theater is a means of discovering communal viewing, a promising antidote to the prevailing loneliness of the screen and screen culture. I remember watching

Lost with my friend Doreen every week during my senior year of college. Now, with series dropping in full and clips and memes circulating online almost immediately, there would be nothing worth waiting for.

But perhaps most importantly, the art form puts the power in the audience’s hands—sometimes brutally so. If you think people will respond to a certain text, you can prove it, or you can flop. A live audience provides an unmitigated authentication process for performers, too: I saw Kieran Culkin struggle to remember his lines at the opening night of Glengarry Glen Ross last spring. On the same night, I saw Bill Burr give a wooden, nervous performance. I found myself wishing that David Mamet and Patrick Marber had just cast veteran stage actors rather than celebrities. But at the same time, I had to respect those rich and famous guys for risking embarrassment. (I heard from a friend a few weeks later that their performances had gotten much better.)

In our era of slop, the ability to hold a room—as a playwright or performer—to command attention and warp it, feels like a form of magic. I’ve encountered many professional disappointments and have yet to see my work on screen—or a large stage. Running a small theater sucks sometimes. I’m constantly trying to raise money, and I’m lucky to have friends in PR who’ve essentially donated their time. I’ve dealt with stalkers, trolls, water main breaks, and, in our Greenpoint space, a rave venue upstairs. But there’s a reason that novelists, filmmakers, famous actors, up-and-comers, agents, and executives continue to show up, stick around, and enjoy themselves there. A show changes every night, so there’s something inherently private about the experience—unmediated and fleeting. If art isn’t about life, and doesn’t add to life as it’s lived, what does it actually do?

By Gracie Hadland

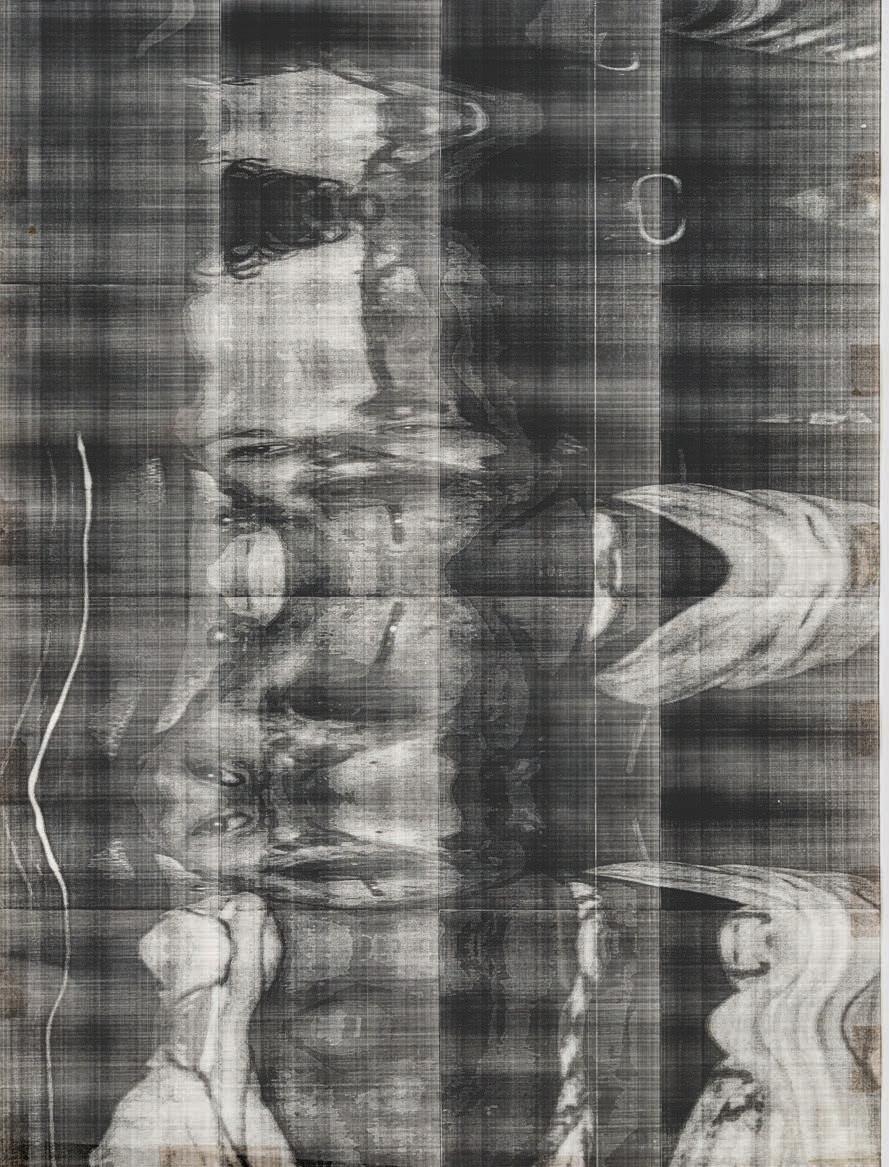

PWolfgang Tillmans has spent the better part of 40 years as the poster child for a certain aesthetic of 21st-century image: simple, austere beauty mixed with a deceptive amateurishness. Now that the digital world has thoroughly caught up, the artist is working to coin the next lexicon of contemporary photography.

It’s 2026 , and Wolfgang Tillmans enjoys the kind of status that could easily tip over into stasis. The 57-yearold German artist, whose photography career spans nearly four decades, is fresh off a major exhibition at Paris’s Centre Pompidou (which he is careful to remind me was not a retrospective) and a 2022 survey at the Museum of Modern Art. It’s fitting that his exhibition of new photographs, sculptures, and video works at Regen Projects in Los Angeles is titled “Keep Movin’.”

Tillmans has managed the rare feat of transcending the art world’s small, insider circles and their spillover into fashion and music. His name is shorthand for a certain aesthetic of the 21st-century photograph: simple, austere beauty mixed with a deceptive amateurishness. (There is always a whiff of humor around his occasionally banal subjects. Two of my favorite Tillmans photos include plastic water bottles.) Despite this esteemed position, the artist seems to be following his exhibition title’s imperative: to continue. For someone who has carved out an aesthetic that has reached maximum—if diluted—saturation online in the last 15 years, he insists on constantly reevaluating what makes a contemporary image. “What’s on the walls is a [the result of a] 40 -year practice,” he tells me, “of exploring what kinds of pictures are possible today.”

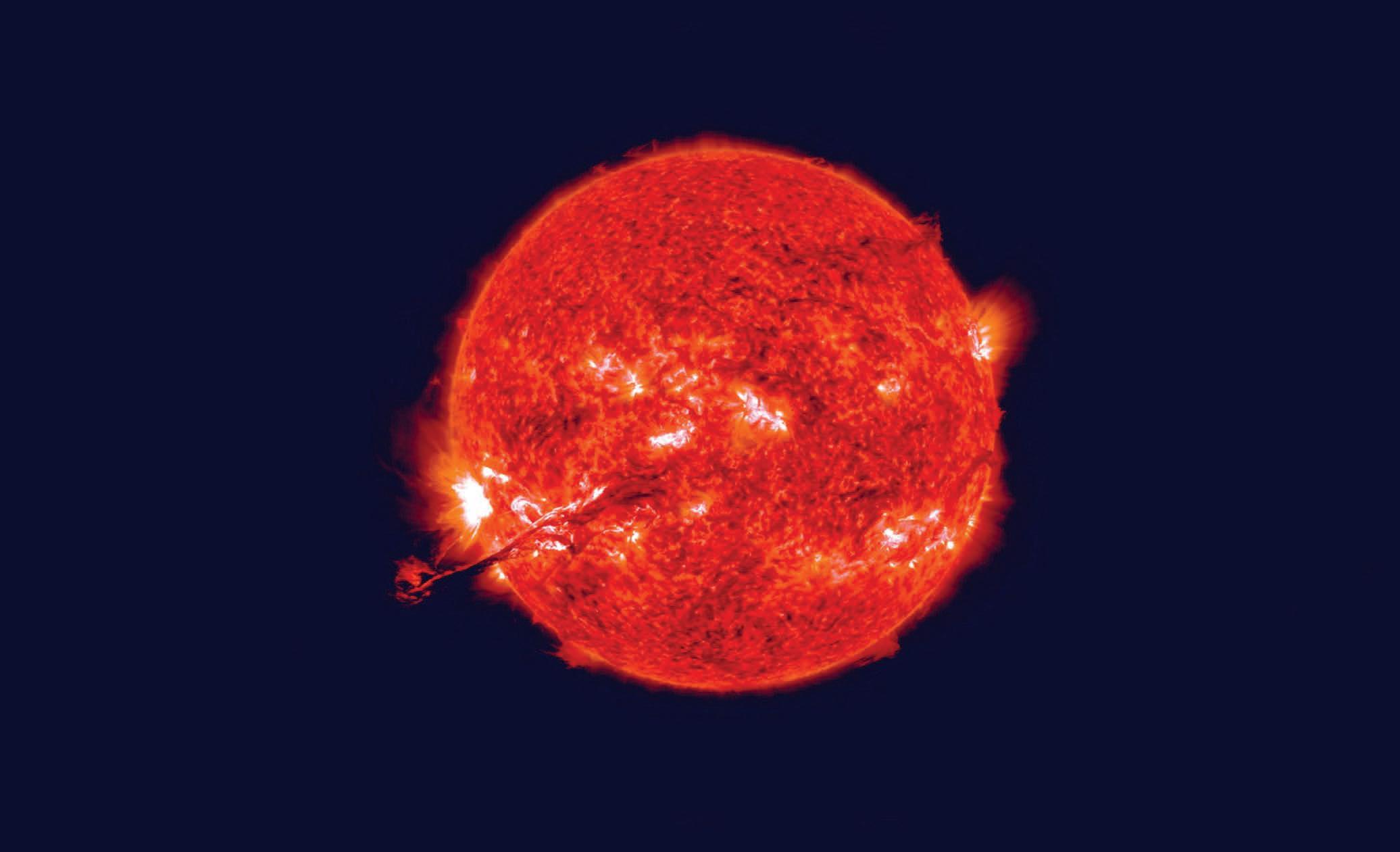

When we meet at the gallery in January, his show is mid-install—his assistant is in the midst of putting prints on the wall—but Tillmans is eagerly awaiting approval from the Mount Wilson Observatory to photograph through its telescope later that day. He’s animated, and as we begin talking, our tight 45 minutes turns into an hour.

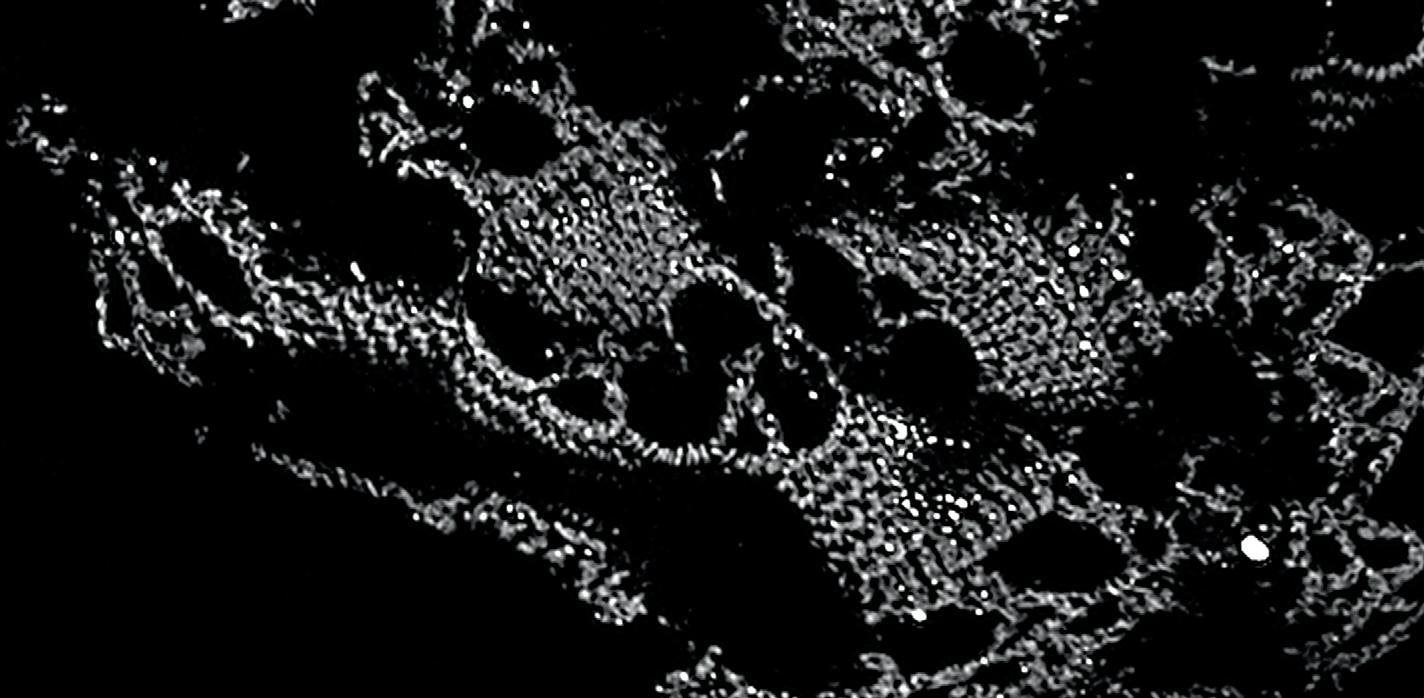

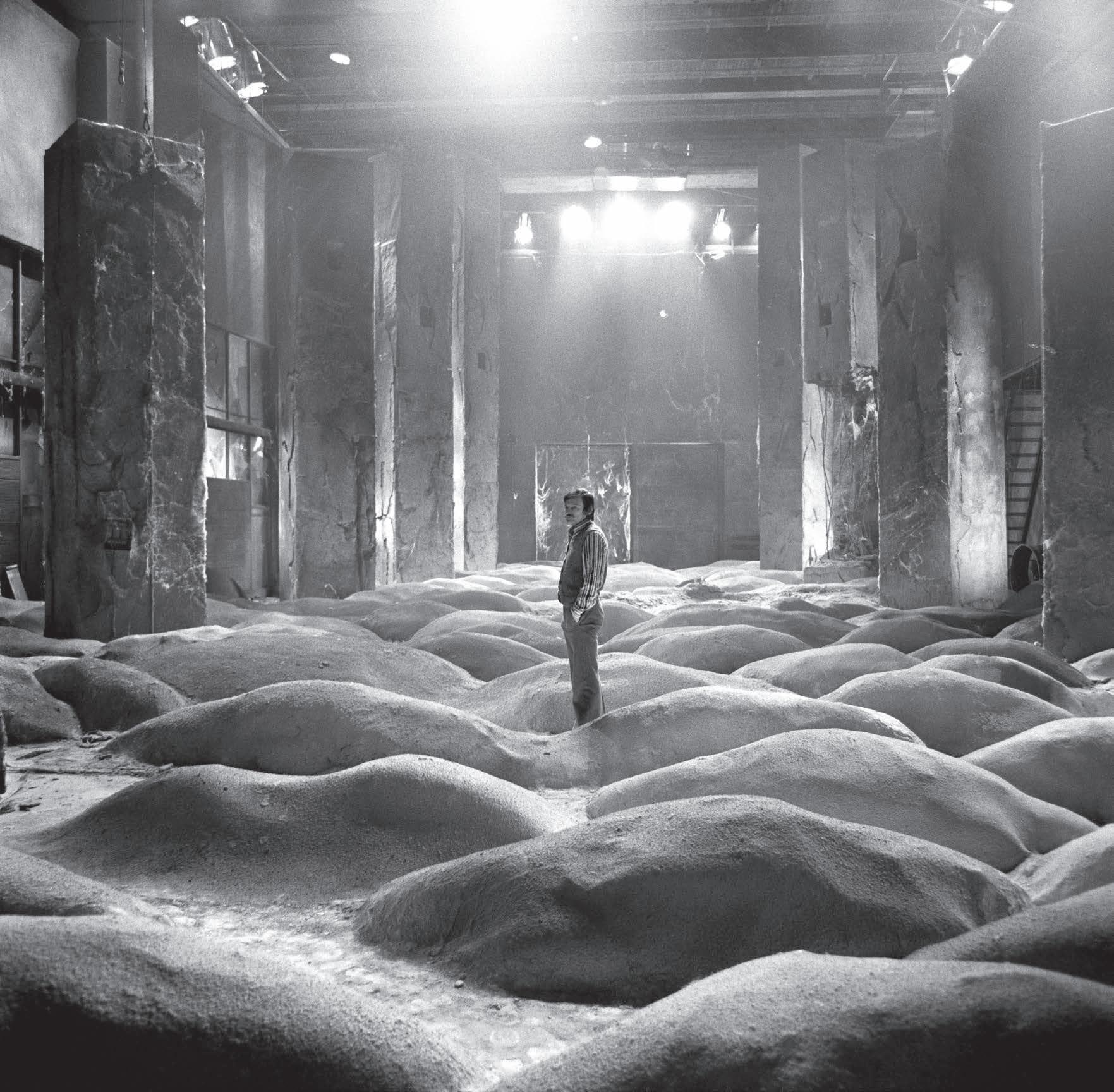

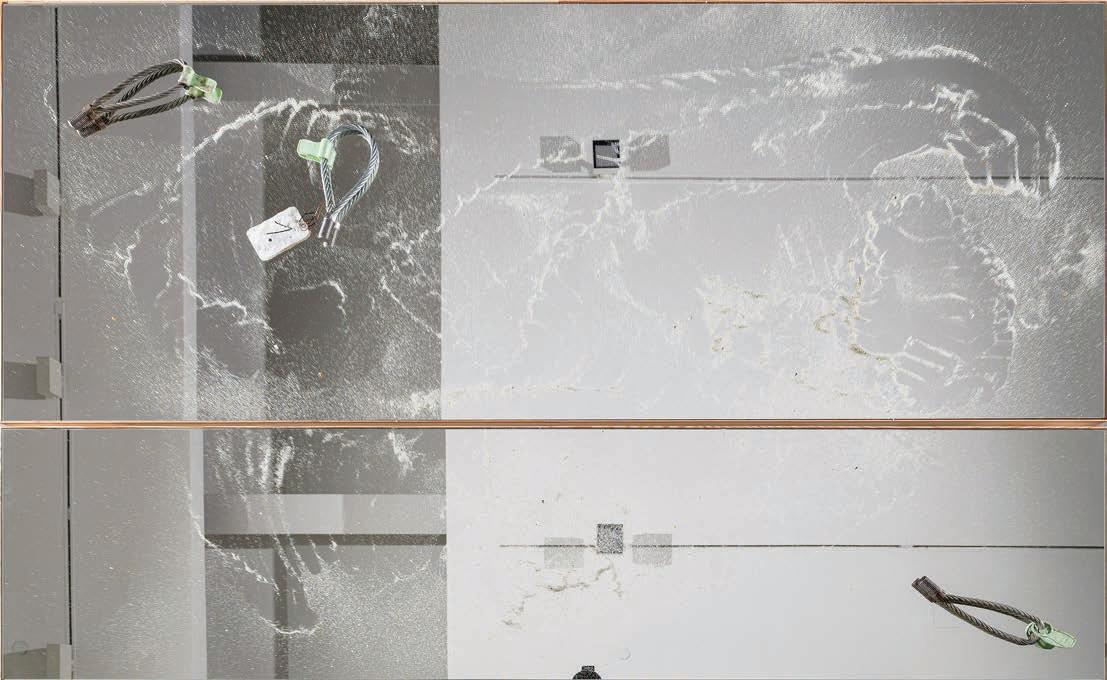

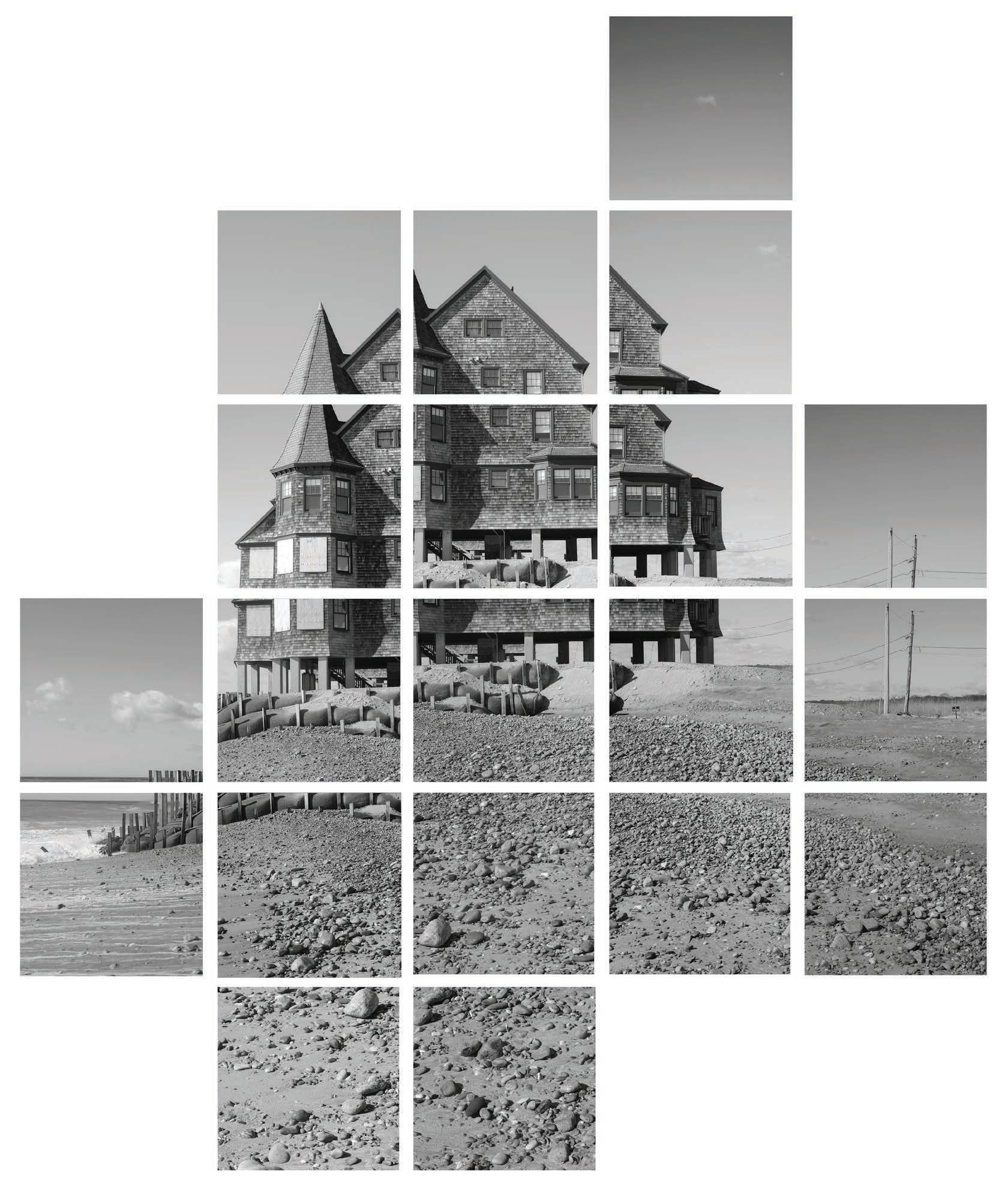

The show feels like the result of someone sifting through recent material in search of connections, but without an endgame in mind. Tillmans seems to have formed “Keep Movin’” around a handful of general ideas or gestures—the social and political cycles and systems, as well as the processes that contribute to the construction of an image—and posits found and made materials to echo them. On the main gallery’s walls are large prints from various bodies of work, as well as unframed works on paper made with a photocopier, and a handful of ready-made sculptures. “The subject matter is potentially everything,” says Tillmans, “which doesn’t exactly make it easier.” Several works depict moments of integration and connection: rivers flowing, ropes hauling ships to shore. In Nautical Ropes and Concrete Lifting Loops, 2025, industrial-grade nautical rope, a synthetic shade of bright blue, rests on the floor of the gallery like a sea creature washed ashore. Nearby is a close-up photograph of offal. The mind links the coiled rope with the squidgy animal intestine: both appear soft but are functionally strong.

Tillmans is interested in these moments of confusion— when something unappealing is decontextualized into something beautiful, and vice versa. “I often work with our own expectations of beauty,” Tillmans tells me as we stand in the middle of the gallery looking down at Truth Study Center (LA03/04 Veiled Offal), which I at first mistook for a wool blanket. “Why do we think something is beautiful or not beautiful? Once you know what that is, why is it suddenly ugly?”

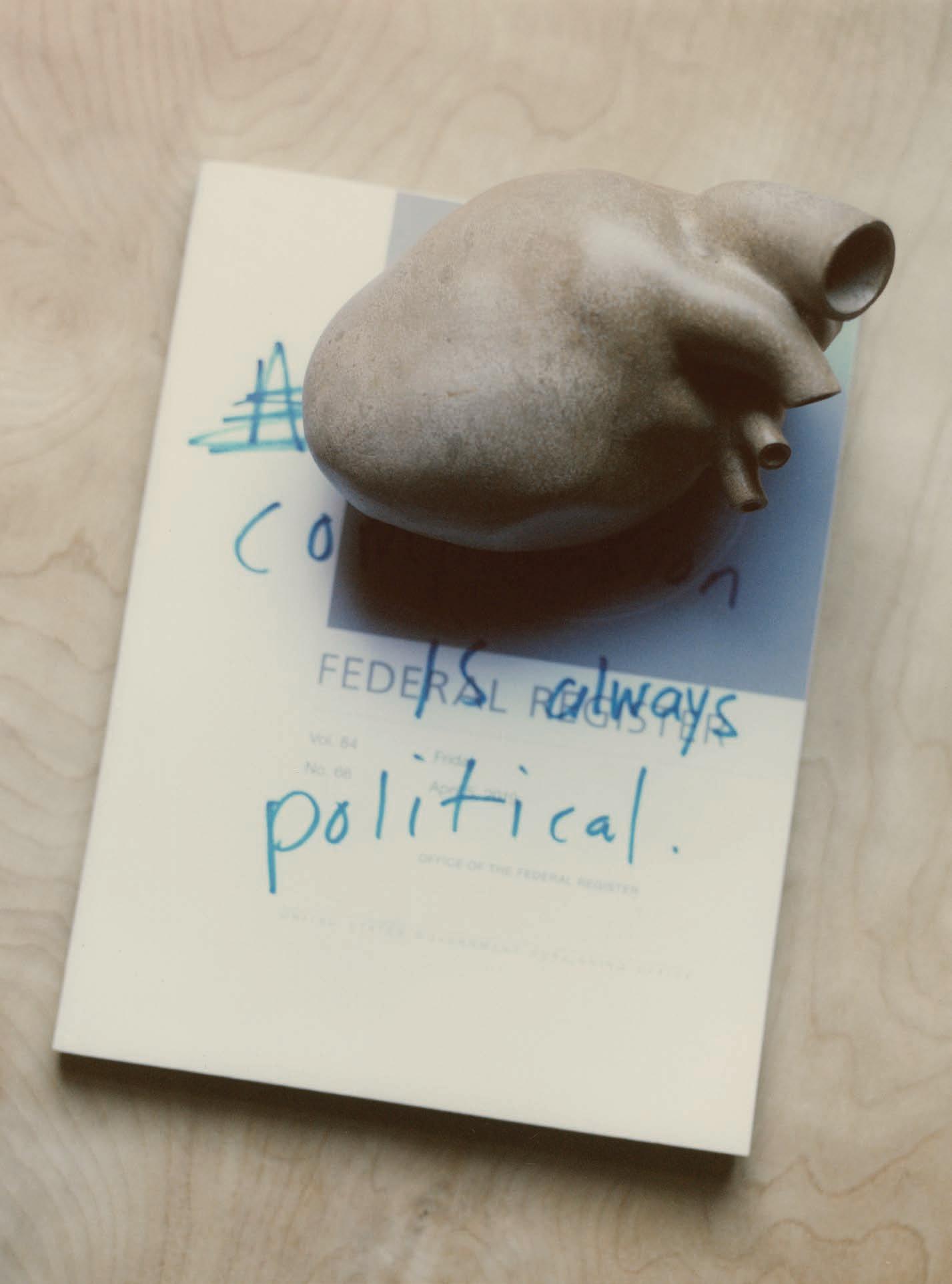

At the center of the gallery are a number of tables festooned with ephemera—from newspaper clippings of current events to stamps, drawings, and the brochure from the rope company that supplied the other sculptures. Tillmans titles these displays Truth Study Center, part of an ongoing practice he began in 2005 “I realized that most of the trouble in the world came from men claiming absolute truths.” Combining these materials reflects the artist’s effort to conjure the truth of our times, laying information and misinformation side by side, examining mechanisms of manipulation in the media. The material reveals the absurdity of the times in which we are living, but the artist’s political message does not reach beyond acknowledgment to indictment. “I am a positive person, an optimist— almost,” he says. “I enjoy my eyes. I enjoy waking up in the morning, being alive. The work that I do is about play, experimentation, and discovery. I don’t want to have that obliterated by what goes on in the world.”

One work, in particular, captures this merry observational precision. Tucked in one corner and playing on a loop is the video Wild Carrot, 2025, of a flower blowing in the wind. The blossom quivers, its concave structure containing what look like hundreds of smaller flowers tucked inside it. The film is accompanied by a tinkling soundtrack Tillmans made himself on the kalimba. “I had a moment—let’s not call it an epiphany, but a moment—and I was able to translate it, without having scripted it or without huge technical effort,” says Tillmans of the video work. “It’s just on the right side of amateur, and just technically satisfying enough that it really works. That’s what I want the photographs to do as well; they look like you could have seen them with your own eyes.” (Tillmans famously eschews any kind of digital manipulation or special effects in his work.) “I don’t want to set up a barrier that puts the audience down,” he continues. “I try to present the work with a low threshold. But behind that, of course, is an aim to master the medium to its greatest potential with the simplest of means.”

The almost naïve whimsy of the bobbing flower left me with the sense that this person knows how to look— really look.

“It’s just on the right side of amateur, and just technically satisfying enough that it really works. That’s what I want the photographs to do: They look like you could have seen them with your own eyes.”

“The subject matter is potentially everything, which doesn’t exactly make it easier.”

“I enjoy my eyes. I enjoy waking up in the morning, being alive. The work that I do is about play, experimentation, and discovery. I don’t want to have that obliterated by what goes on in the world.”

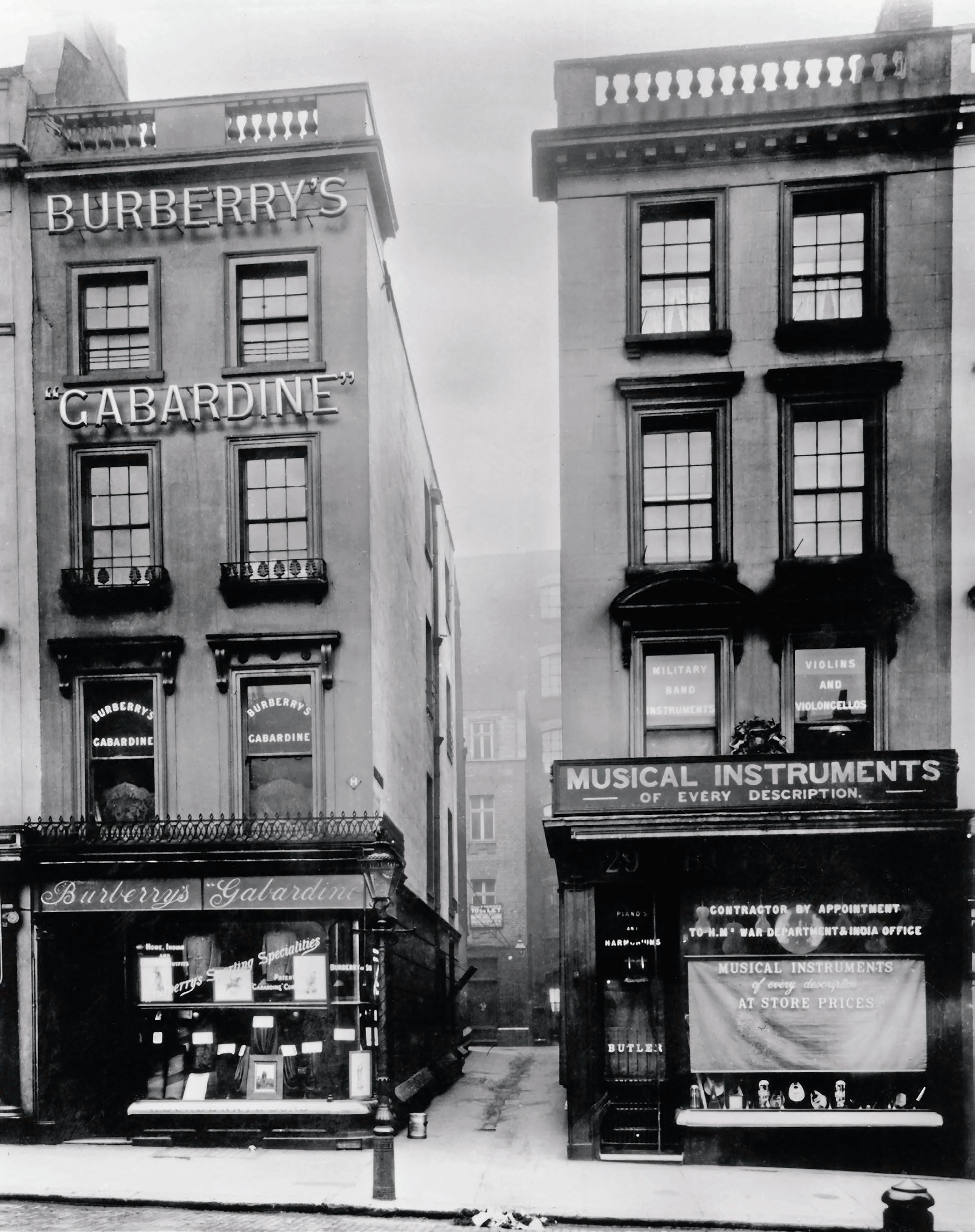

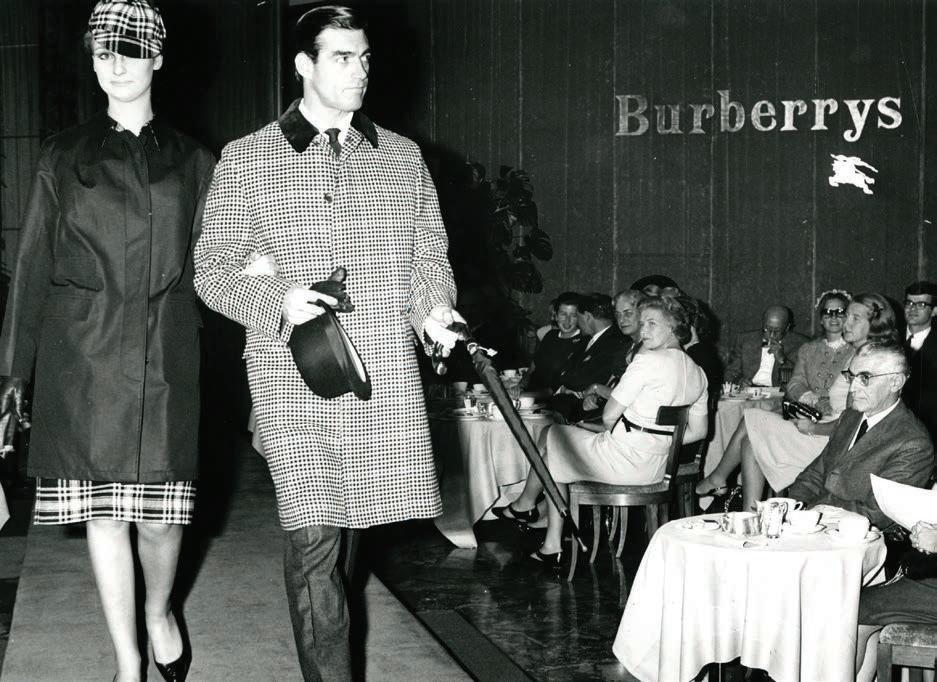

Carly Eck presides over a collection of thousands of Burberry pieces. Don’t look so jealous.

BY KARLY QUADROS

In August 1926 , Sir Alan Cobham became the first person to fly from London to Australia and back again. The 47-day, 13,000 -mile trip was long, arduous, and closely followed by the press and public. A crowd of thousands gathered at the aerodrome in Sydney to watch Cobham touch down and emerge from his plane, his smart tan trench coat flapping in the wind.

Burberry, the designer of that coat, recently released a new version, a century later. It’s reversible, wool on one side and gabardine on the other, making it ideal for the daring exploits of Cobham or those of the explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, who wore Burberry gabardine on three Antarctic expeditions in the early 20 th century. But, over time, Burberry—along with the likes of popular brands Barbour, Filson, and more recently Salomon—has seen its functional and hardy gear transform into coveted objects of style worn by everyone from Queen Elizabeth II to Britpop stars.

How did that happen? Carly Eck knows. She boasts a 14 -year tenure in Burberry’s archival department, and became VP last year. “Items such as the Burberry trench coat have been culturally adopted and reinterpreted by successive generations who celebrate them not only for their function but for their timeless style, their humble backstory,” says Eck.

If anyone would know—about every beat of the house’s 170 -year history or its most iconic customers— it’s Eck. Her job is part detective, part preservationist, part storyteller. The extensive archive includes over 25,000 garments and accessories, as well as a trove of advertisements, fabric sample books, and sales catalogs, “some of which are works of art in and of themselves.” She’s traveled as far as Singapore and Australia to hunt down rare pieces to add to the collection.

Eck knows she’s lucky to have the kind of job that would have fashion geeks green with envy. (And yes, if you’re wondering, she does sometimes get her pick of vintage styles and runway samples in unreleased colors.) But her role as the archive’s steward comes with no small amount of responsibility. As a wave of new designers take the helm at historic fashion houses in recent years, there has been plenty of heated debate about what “is” or “isn’t” a house code.

“Continuity and change are not mutually exclusive, but interdependent,” Eck notes, “and both play a unique role when it comes to style and fashion.” But, in an industry as cyclical as hers, what Eck loves most are the hidden histories that can make something as simple as a tan trench coat feel new again and again. As she says, with fashion, “there is often more than meets the eye.”

BY ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

Think of the women on the following pages as you would the great adventurers of another era. Like those (mostly male) trailblazers, Harmony Hammond, Maren Hassinger, Cynthia Hawkins, Michele Oka Doner, and Pat Oleszko have indefatigably charted new territory over the course of their careers in art. They did not settle for the status quo or trending movements their peers adopted, but looked inside and out to

uncover new realities and ways of expressing them, armed with humor, ambition, and no small dose of defiance. Some met acclaim early on; others have only recently benefited from gallery representation. All now over the age of 75, their work is being reexamined as the art world zeros in on the contributions the canon has overlooked, brushed aside, or actively excluded. This attention is well-deserved, but also beside the point: They were always going to be artists, no matter what.

Cynthia Hawkins tried paint-by-numbers as a child, but immediately knew it was not for her. It was Piet Mondrian’s tree series that gave her permission to leap toward abstraction as an undergrad at Queens College, a movement she’s been making her own ever since. At ��, Hawkins has also cemented her legacy as a scholar and curator, but it’s her compulsion for mark-making and pursuit of color that keep her coming back to the studio.

“It’s important that people understand that nothing comes easy. I didn’t give up [anything to be an artist], I fought to keep it. I had two kids, and there was a time where I struggled. I would occasionally just go mad, like, ‘I’m going to the art store. I’m buying this no matter what. I don’t care.’ I fought to keep [my practice] going, because I wouldn’t know who I was without it. The hardest thing is having a full-time job and making time. If you are not from a wealthy background, you have to have a job. But nobody said you had to paint eight hours a day; in a whole week, if you get 20 hours in there, that’s fine. When we all came up, we never thought about money. All we wanted was a group show to build our exhibition history. You have to be committed. Everybody has periods where they don’t work as much, but that doesn’t mean that you stop either. It’s interesting how much I think about my work; it pops into my head in the kitchen, when I’m falling asleep, or I wake up thinking about it. It’s as important a part of your life as your kids. You’re not the same if you stop doing it.”

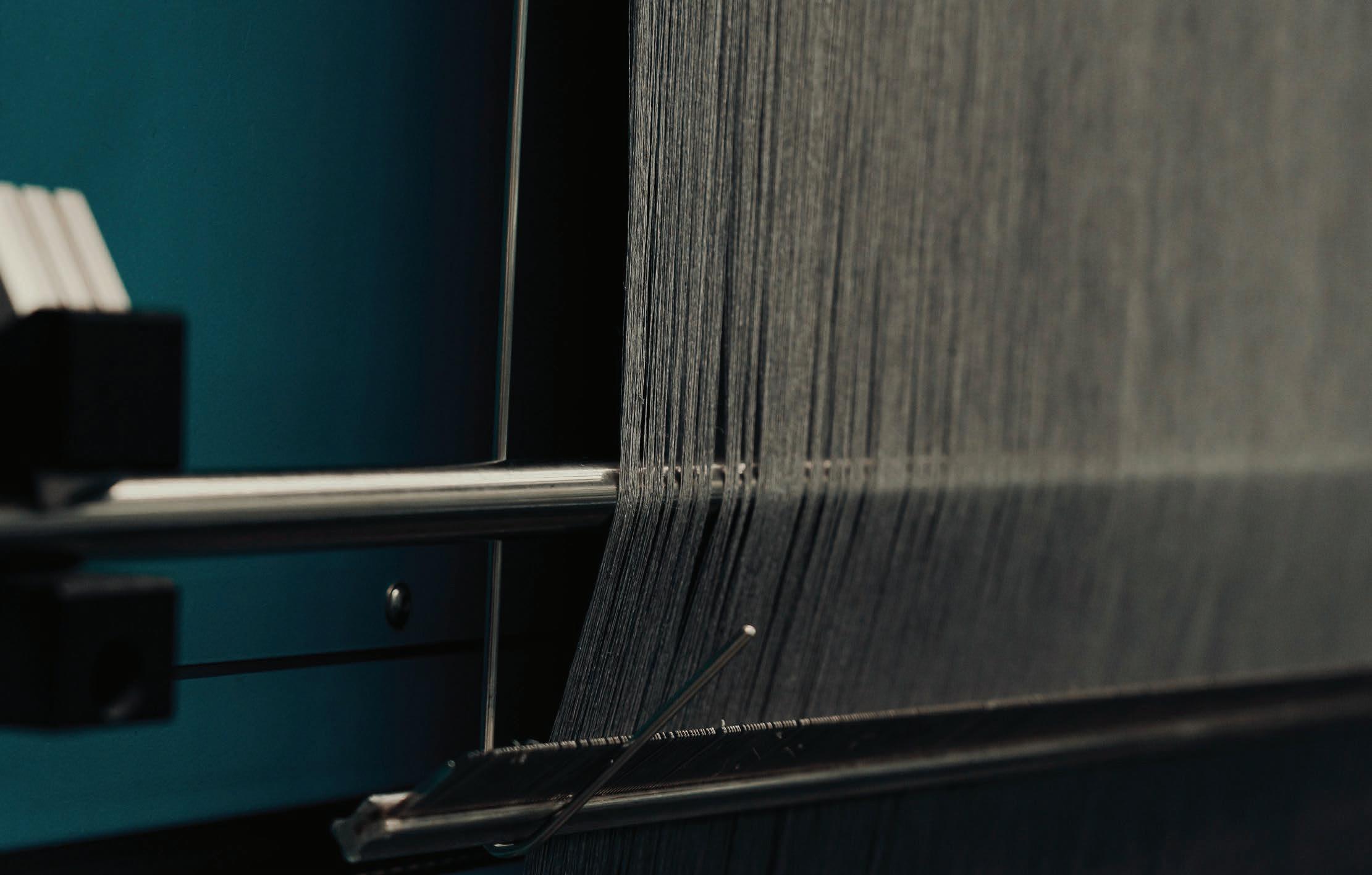

“I think art, like language, can do anything. But everybody has to understand their particular limitations. I see my limitations, and I work with them. The limitation I adhere to for the most part is working with steel because I don’t have to worry about longevity. If I’m weaving out of fabric, there’s always going to be a huge sensitivity to the atmosphere around it. You have to watch out for mold, for insects. With steel, there’s none of that. Nobody’s gonna try to eat a piece of steel. And I like the way steel wire rope can mimic nature, like it’s blowing in the wind or capturing something. I’m very moved by nature; I’m not bewitched by the computer. I’m not moved by absolute abstraction either. These things that I’m making are, in my opinion, closer to reality than anything. By moving beyond flatness, they have presence and dimensionality, and that’s where we live and how we function: We walk through rooms, we run to catch a train, and we swing on swings. Steel is a metal you can get involved with.”

Steel is strong enough to reinforce a building, yet delicate enough to form a scalpel. In Maren Hassinger’s work, the material can adopt both of those qualities, but mostly it is alive. Over the years, her sculptural interventions have been activated by the elements, time, and bodies (namely her own and that of Senga Nengudi, her co-conspirator since the ’��s). The ��-year-old artist’s largest retrospective to date opens at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive in June.

Growing up in Florida, Michele Oka Doner saw her father become a judge, then a mayor. If Miami gave her the civic gene, Detroit, where she moved in the late ’��s after studying at the University of Michigan, taught her how to put it to use. While there, Oka Doner, now ��, took her art off a pedestal (literally), giving viewers more direct contact with her sculptural relics inspired by the natural world. In the decades since, she’s brought her work even further into the public arena. Her mile-long floor installation at Miami’s airport is seen by over �� million travelers a year.

“It is a challenge to assume a singular voice as an artist, when the consensus is that there’s this trend, and you should maintain it. But it wasn’t a burden I couldn’t shoulder. I enjoyed the process of transforming thoughts and dreams into a visual so much that I just kept going. I stayed on my track. I was challenged even in graduate school; there were six men, but I knew I didn’t want to be them and I knew I didn’t want to paint stripes or targets or weld I-beams. I remember reading that there could be no Mozart today, because Mozart composed in a world that had silence, and today, there is too much static. So I have a quiet life. If you came to my studio, you would see it. I really do take time, and I don’t go on devices. I still don’t know how to turn on our TV screen. I’m not a big watcher, because by the time television came to our home, I was 6 or 7 and already outside whenever I had free time. The idea of sitting in the dark watching something… I’ve never been a spectator; I’ve been a participant.”

February 13–August 16

HIFI PURSUIT LISTENING ROOM DREAM NO. 3

On view through July 19

H�����(

H�����)

Harmony Hammond, ��, is the rare figure to both earn renown as a contemporary artist and have a hand in how the movements of her time are remembered in art history. Her sculptures and canvases have given textiles a new remit in the world of abstraction, while her texts—Lesbian Art in America and Wrappings among them— remain unparalleled in their juxtaposition of identity politics, art criticism, and feminism as a lived experience. A volume dedicated to her life in words, Still Dangerous! The Harmony Hammond Reader, will release this fall.

“I guess I work slowly compared to some other artists. I am always working, but the practice of making the work does take time, because it evolves out of the handling of the materials. I don’t really know where I’m going when I start, and that keeps me on my toes. I’m so focused on and physically engaged with what the materials can do; while I’m working, I’m not even thinking about what I’m doing means. I try to stay very present and not get outside of myself, because I don’t think that’s good for making art. I like to work maybe four or six hours at a time in the studio, and as I’m beginning to wind down, I might sit and look at what I’ve done. I’m just trying to see what’s there, what’s being suggested. Then, because I’m the artist, of course, I can choose to go in this or that direction to develop content. I can underscore, I can elaborate, I can eliminate. But it’s really looking at what the materials and I have done in collaboration, or at least in conversation. I should also say I rarely put the radio or music on. I like listening to the sound of my own thoughts going through my head as I’m working with materials, and I really like listening to the materials. I think part of that is having been a professor for so long and a single mother—there’s always somebody talking. So I like quiet.”

Every industry needs its chaos agent, and thank God the art world has Pat Oleszko. The )�-year-old artist, who has lived in a Tribeca loft stu ffed to the brim with her creations since the ’),s, reflects the issues of our time back at us with wit and gravitas through performances that pull from burlesque, commedia dell’arte, and protest movements. Her rich archive of inflatables and costumes is the subject of her first New York solo show in -. years at SculptureCenter, on view through April.

“I knew I was going to be an artist in kindergarten because we had to do a self-portrait, and mine was so clearly the best in the class. When I got to college— going to the University of Michigan at that time, I believe, was like going to the Bauhaus or Black Mountain College— there was just a pervasive brilliance with the students and the teachers. I couldn’t learn how to weld—my things kept falling down—so I was working at home and sewing. Then I realized I was six feet tall, so I could hang the work on myself. That was my eureka moment because it was engaging with ideas and putting them out, not in a hallowed white cube. My whole life I’ve been exploring this gift that I discovered. Everything I’ve ever done that has been sort of more pedestrian; I have manipulated into my work. When I was a waitress, every night was a different kind of performance. When I was stripping, it wasn’t stripping like they were… I’m never happier than when I’m working, never, ever. And the thrill of putting the piece out in public—it’s better than any drug. I don’t have any fear about putting myself out there as a fool. I know how to handle the crowd. But I’m still fearful of what might happen to me in different situations, whether it’s on the stage or in the street, leading a crowd. I know much more, but it’s still terrifying the first time you do anything. It’s always hard, and it’s always easy, because it’s what I have to do.”

The museum founder and arts patron is in the midst of a surprisingly unglamorous new chapter—as a real estate developer.

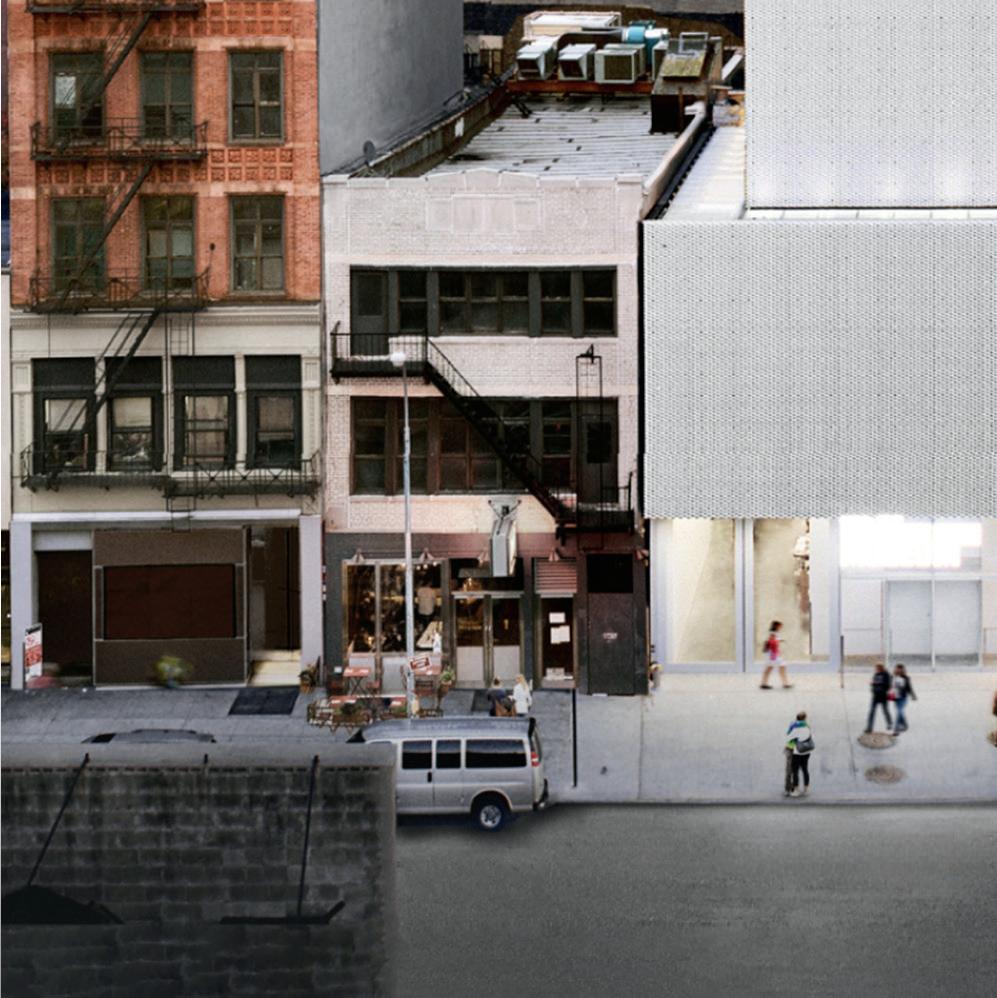

On a recent morning, Dasha Zhukova welcomes me into the lobby of Ray Harlem, a new residential property development on Fifth Avenue, just off 125th Street, where the National Black Theatre has been located for more than four decades. The lobby’s enormous windows look directly onto the street; inside, the room is layered in hues of dark green, mustard yellow, and pink. Opulence, a painting of a woman in a fur coat by the American artist Jurell Cayetano, hangs above the couch.

Zhukova—a former fashion designer, magazine publisher, and museum founder who is a Met Gala fixture and was twicenamed to Vanity Fair ’s Best Dressed List— is not your average real estate developer. But according to her, this new stage of her life makes complete sense. She first began work on her new company, Ray, in 2018. In 2021, it won a bid to replace the National Black Theatre’s original building. Her concept was innovative but simple: The 27,000 -square-foot theater would remain the corner property’s centerpiece, while 21 floors of residential space would be built above it. With site-specific commissioned artwork, theater workshops,

and event space, the building would be a place where culture, art, and community meet.

Zhukova gives me a tour of the building briskly. She is a mother of five—her youngest is 1, her oldest just turned 16 and time, she acknowledges, is often in short supply. But her demeanor is relaxed. Above the mailboxes hangs another painting, commissioned by Ray, by Dominican-born artist Freddy Carrasco. Upstairs, alongside a gym, is a library, a tea room, and artwork by emerging Black artists Nikko Washington and Ellon Gibbs. We step briefly out onto the roof terrace. All of Manhattan sprawls out before us, with the top of Central Park immediately below.

The red-brick building was designed by Frida Escobedo Studio with Handel Architects. Rents range from $3,000 for a studio to over $4 ,000 for a two-bedroom (a quarter of the 222 apartments were made available through a public affordable housing lottery last year; nearly all are now occupied). Small details like floating shelves of white oak add a soft but contemporary touch. A young man walks past us on the terrace as we settle

DASHA ZHUKOVA’S

By Thessaly La Force

Photography by Anna Kozlenko

onto a couch, his dog running ahead. All sorts of people live here, Zhukova tells me: doctors, lawyers, families, Columbia students.