women th e wo r ld m u st hear

For the Love of Native Foods

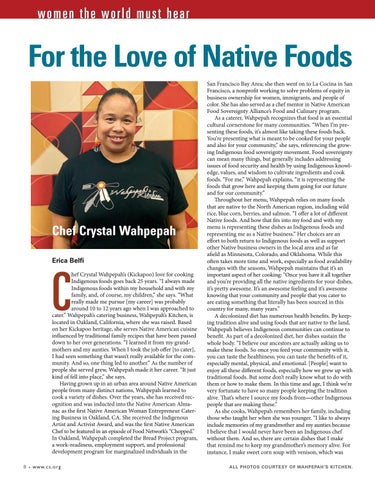

Chef Crystal Wahpepah Erica Belfi

C

hef Crystal Wahpepah’s (Kickapoo) love for cooking Indigenous foods goes back 25 years. “I always made Indigenous foods within my household and with my family, and, of course, my children,” she says. “What really made me pursue [my career] was probably around 10 to 12 years ago when I was approached to cater.” Wahpepah’s catering business, Wahpepah’s Kitchen, is located in Oakland, California, where she was raised. Based on her Kickapoo heritage, she serves Native American cuisine influenced by traditional family recipes that have been passed down to her over generations. “I learned it from my grandmothers and my aunties. When I took the job offer [to cater], I had seen something that wasn’t really available for the community. And so, one thing led to another.” As the number of people she served grew, Wahpepah made it her career. “It just kind of fell into place,” she says. Having grown up in an urban area around Native American people from many distinct nations, Wahpepah learned to cook a variety of dishes. Over the years, she has received recognition and was inducted into the Native American Almanac as the first Native American Woman Entrepreneur Catering Business in Oakland, CA. She received the Indigenous Artist and Activist Award, and was the first Native American Chef to be featured in an episode of Food Network’s “Chopped.” In Oakland, Wahpepah completed the Bread Project program, a work-readiness, employment support, and professional development program for marginalized individuals in the 8 • www. cs. org

San Francisco Bay Area; she then went on to La Cocina in San Francisco, a nonprofit working to solve problems of equity in business ownership for women, immigrants, and people of color. She has also served as a chef mentor in Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance’s Food and Culinary program. As a caterer, Wahpepah recognizes that food is an essential cultural cornerstone for many communities. “When I’m presenting these foods, it’s almost like taking these foods back. You’re presenting what is meant to be cooked for your people and also for your community,” she says, referencing the growing Indigenous food sovereignty movement. Food sovereignty can mean many things, but generally includes addressing issues of food security and health by using Indigenous knowledge, values, and wisdom to cultivate ingredients and cook foods. “For me,” Wahpepah explains, “it is representing the foods that grow here and keeping them going for our future and for our community.” Throughout her menu, Wahpepah relies on many foods that are native to the North American region, including wild rice, blue corn, berries, and salmon. “I offer a lot of different Native foods. And how that fits into my food and with my menu is representing these dishes as Indigenous foods and representing me as a Native business.” Her choices are an effort to both return to Indigenous foods as well as support other Native business owners in the local area and as far afield as Minnesota, Colorado, and Oklahoma. While this often takes more time and work, especially as food availability changes with the seasons, Wahpepah maintains that it’s an important aspect of her cooking: “Once you have it all together and you’re providing all the native ingredients for your dishes, it’s pretty awesome. It’s an awesome feeling and it’s awesome knowing that your community and people that you cater to are eating something that literally has been sourced in this country for many, many years.” A decolonized diet has numerous health benefits. By keeping tradition alive and using foods that are native to the land, Wahpepah believes Indigenous communities can continue to benefit. As part of a decolonized diet, her dishes sustain the whole body. “I believe our ancestors are actually asking us to make these foods. So once you feed your community with it, you can taste the healthiness; you can taste the benefits of it, especially mental, physical, and emotional. [People] want to enjoy all these different foods, especially how we grew up with traditional foods. But some don’t really know what to do with them or how to make them. In this time and age, I think we’re very fortunate to have so many people keeping the tradition alive. That’s where I source my foods from—other Indigenous people that are making these.” As she cooks, Wahpepah remembers her family, including those who taught her when she was younger. “I like to always include memories of my grandmother and my aunties because I believe that I would never have been an Indigenous chef without them. And so, there are certain dishes that I make that remind me to keep my grandmother’s memory alive. For instance, I make sweet corn soup with venison, which was All photos courtesy of Wahpepah’s Kitchen.